Introduction

A hypertensive crisis is characterized by a state

of acutely elevated blood pressure (>180 systolic / 110 diastolic),

necessitating prompt medical intervention to prevent serious consequences and

potential death [1]. It can arise as a

consequence of uncontrolled chronic hypertension or manifest suddenly in

previously healthy individuals [2].

Hypertensive crises are classified into two types: hypertensive urgency (HU),

characterized by the absence of hypertensive mediated organ damage (HMOD), and

hypertensive emergency (HE), characterized by its presence. Treatment

recommendations differ as HU is considered milder and less dangerous, often

requiring ambulance-administered blood pressure reduction, whereas HE typically

necessitates hospitalization [3]. This patient

categorization is a one-time assessment conducted during admission to the

medical ambulance, aiming to aid physicians in decision-making. The reasons why

acute hypertension leads to organ damage in some individuals and not in others

remain unclear. Are there factors influencing the outcome of an acute

hypertensive crisis? Moreover, it's uncertain whether the type of hypertensive

crisis affects the likelihood of future cardiovascular events. Should patients

with HE be more concerned than those with HU? If so, is it due to the potential

risk factors they are exposed to? There is a scarcity of studies examining the

impact of cardiovascular risk factors on the outcome of hypertensive crises,

either immediately or after a certain follow-up period.

Methods

This retrospective study included patients aged 18

years or older with systolic blood pressure (SBP) ≥180 mmHg and/or diastolic

blood pressure (DBP) ≥110 mmHg, who were admitted to the Clinic of Emergency

Medicine, Clinical Center of the University of Sarajevo over a six-month

period. Data were collected from hospital electronic patient records, with

pregnant women being excluded from the study. Patients

who died before completing the diagnostic examination or determining the

presence/absence of hypertensive mediated organ damage (HMOD), which

distinguishes hypertensive emergency (HE) from hypertensive urgency (HU), as

well as patients with incomplete data regarding risk factors or other relevant

information, were also excluded.

Data collection encompassed

not only blood pressure levels, diagnostic results, and outcomes but also

cardiovascular risk factors such as age, sex, history of chronic hypertension,

dyslipidemia, smoking status, and presence of diabetes mellitus. The

outcomes after admission were categorized into discharge after ambulance

treatment, discharge after hospitalization, and death (either during ambulance

transport or hospitalization).

A six-month follow-up involved collecting all

medical records from the electronic medical registry during this period. We

documented occurrences of new hypertensive crises, cardiovascular events, and

cardiovascular-caused deaths, while excluding patients who died from other

causes. The final six-month outcomes were classified into the following

categories: absence of new events and recurrent emergency department (ED) or

hospital admissions, recurrent hypertensive crises and/or other cardiovascular

events, and death. As this was a retrospective non-interventional observational

study, patients who died soon after the initial recorded admission (considered

the primary outcome) were included in the six-month outcome analysis to present

the overall outcome from the time of admission to the ED ambulance until six

months afterward (considered the final outcome).

Statistical Analysis

All data were analyzed and graphically presented

using the IBM SPSS 20 software. The Shapiro-Wilk test was utilized to assess

the normality of distribution for continuous variables. Descriptive statistics,

including counts, percentages, medians, and interquartile ranges, were

employed. Categorical data were compared using the chi-square test, while

non-normally distributed data were analyzed using non-parametric methods such

as the Kruskal-Wallis test for multiple independent data and the Mann-Whitney test

for two independent data groups. A significance level of p > 0.05 was

considered statistically significant.

Results

The study included 243 patients: 66 (27.2%) with

hypertensive emergencies and 177 (72.8%) with hypertensive urgencies.

Hypertensive mediated organ damage (HMOD) in hypertensive emergencies presented

as ischemic/haemorrhagic stroke in 25 cases (37.8%), acute coronary syndrome in

18 cases (27.3%), heart failure/pulmonary edema in 15 cases (22.7%), acute

aortic syndrome in 4 cases (6.1%), and other conditions in 4 cases (6.1%). The

median values of systolic/diastolic pressure in the observed patients were 190 (IQR

30) / 100 (IQR 10). Both groups had similar values except for the diastolic

pressure in hypertensive emergencies, which was significantly higher with a

median value of 110 (IQR 20) (p<0.05).

Analysis of risk factors showed a similar number of

men (49.4%) and women (50.6%) in the overall sample, but there was a

statistically significant predominance of men (68.2%) in hypertensive

emergencies and women (57.6%) in hypertensive urgencies (p<0.05). The median

age of the overall sample was 66 (IQR 15), and there was no statistically

significant difference in age between patients with hypertensive urgencies and

emergencies (p>0.05). Among all observed patients, 29.6% were smokers, 18.5%

had diabetes mellitus, and 81.1% had a history of previous chronic

hypertension. There was no statistically significant difference between

patients with hypertensive urgencies and emergencies regarding the frequency of

each of these three risk factors (p>0.05). The median blood pressure levels

of the overall sample were 190 (IQR 30) / 100 (IQR 10). Patients with

hypertensive urgencies and emergencies did not statistically differ according

to systolic blood pressure levels, but those with hypertensive emergencies had

significantly higher diastolic blood pressure levels. Dyslipidemia was present

in 39.5% of all patients without significant differences between the groups.

The results are summarized in

Table 1.

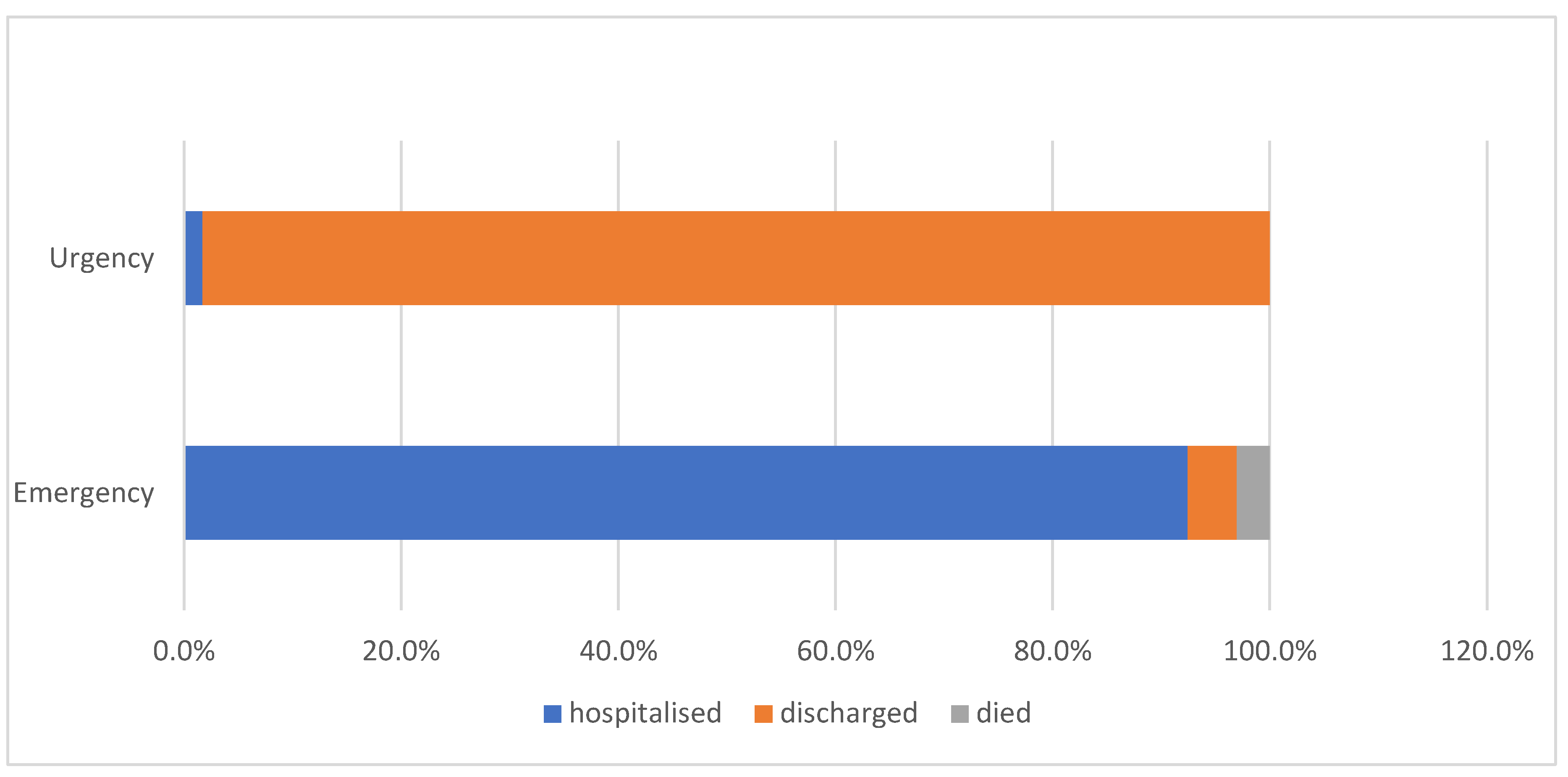

The vast majority of HU patients (98.3%) were discharged after ambulance treatment, with only 1.7% requiring hospitalization due to resistant elevated blood pressure levels without HMOD. In contrast, and understandably so, the majority of HE patients (92.4%) were hospitalized and discharged after successful treatment, while 3% succumbed to their condition in the hospital. Although HMOD is significant for these patients, there were still 4.5% of discharged patients due to a milder form of the disease or refusal of hospitalization.

After a six-month follow-up, we discovered that 65% of patients experienced no complications. Both HU and HE patients [had a similar percentage of individuals without readmission to medical services (63.3% and 69.7% respectively). In total, there were 93 recorded readmissions, with 9 patients experiencing two readmissions and 3 patients having three readmissions. Among these readmissions 30 were hypertensive crises with or without organ damage, accounting for 32.3% of all readmissions. The clinical presentation of readmissions is detailed in

Table 2.

Figure 1.

Outcome of the initial admission.

Figure 1.

Outcome of the initial admission.

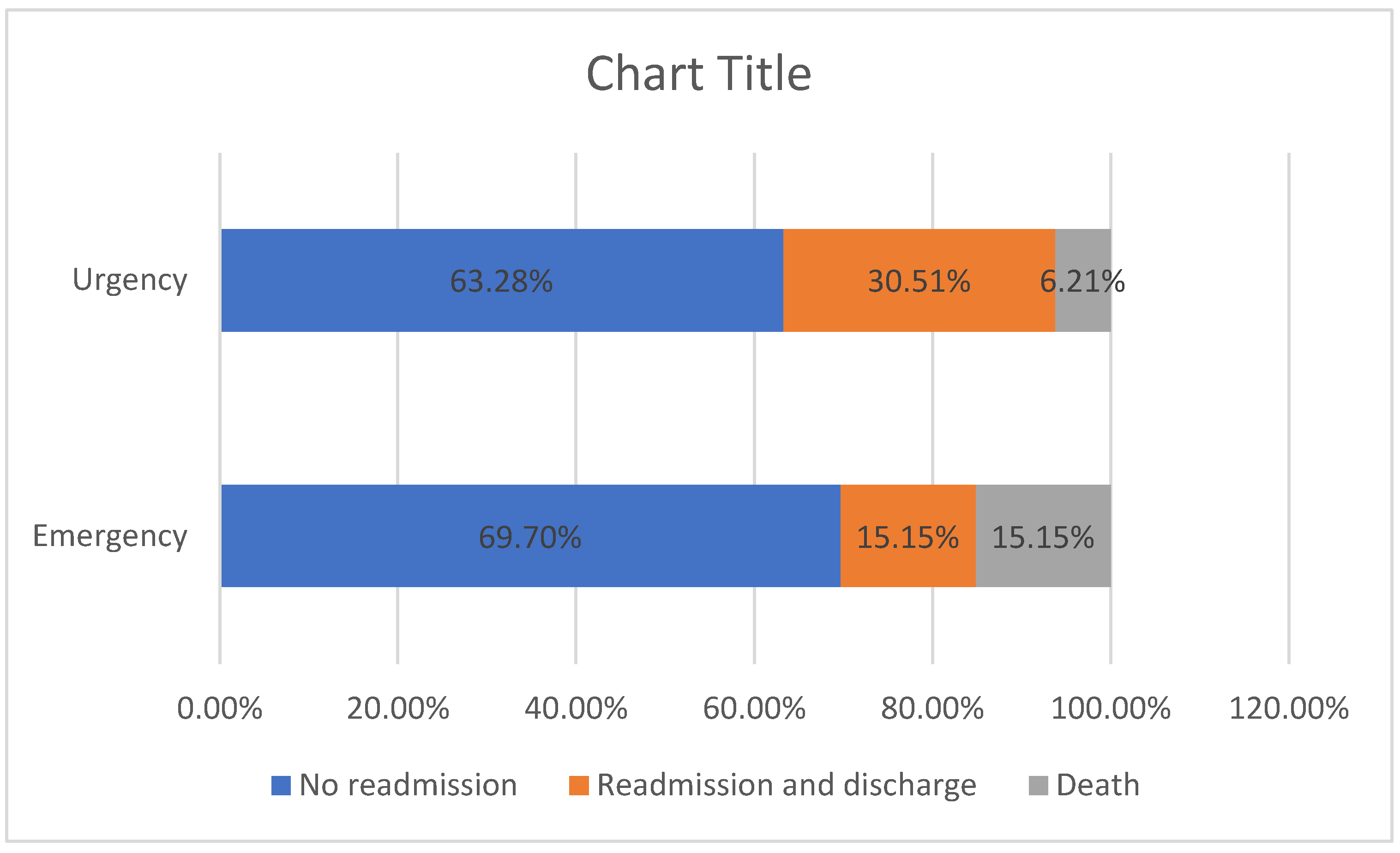

The HU group exhibited a 30.51% rate of non-fatal complications and a 6.21% rate of fatal complications, while the HE group had identical percentages of 15.15% each (p=0.011). These results are depicted in

Figure 2, which illustrates the outcomes of patients from the initial admission to the six-month follow-up period.

The mortality rate of HE patients was 15.15%, with 3% of patients succumbing during the initial admission, resulting in a 12.15% mortality rate for subsequent readmissions. Conversely, all HU patients survived after the initial admission, yielding a mortality rate of 6.21% for readmissions.

Figure 2 displays the outcomes of patients from the initial admission to the six-month follow-up period.

An analysis of the impact of risk factors on the six-month outcome revealed no statistically significant difference in the number of male/female patients, those with a history of chronic hypertension, smokers, and patients with diabetes mellitus between the groups of hypertensive crisis patients without complications, with non-fatal complications, and with fatal complications (p>0.05). However, age was significantly higher in patients with complications during the six-month period (p=0.000). The results are presented in

Table 2.

Discussion

The observed sample of patients showed a predominance of HU over HE cases (72.8% vs. 27.2%) consistent with clinical experience and other findings [

4]. The most common presentations of HMOD in HE patients were stroke (hemorrhagic or ischemic), followed by acute coronary syndrome and heart failure/pulmonary edema, while other presentations were rare. Discrepancies in findings across studies may be attributed to differences in lifestyle, health habits, and ethnicity in the studied populations [

4,

5].

The frequency of observed risk factors was compared with results from other studies. The percentage of patients with existing hypertension in our research was relatively high (81%), similar to samples from other studies. There was also a predominance of patients older than 65 years in our study and others [

6,

7]. While we found a slight predominance of women (50.6%), some studies reported significantly higher percentages of men [

7]. Additionally, the number of patients with a history of diabetes varied across different studies (6,7,8), possibly due to differences in therapy, lifestyle habits, ethnicity, and sample selection. The prevalence of smokers in our sample (29.6%) fell between the percentages reported in other studies, which could reflect differences in anti-smoking campaigns and patient reporting accuracy. Our sample also had a significant proportion of patients with dyslipidemia (39.5%), which aligns with expectations given local dietary habits though it contrasts with findings from other studies conducted in Italy [

5]. Blood pressure values at admission were similar in our study compared to other reports [

5,

8].

Patients with HU and HE did not statistically differ in terms of smoking status, diabetes mellitus, or median age. However, there was a significant predominance of men and patients with previously verified hypertension in the HE group. This group also had significantly higher diastolic blood pressure levels. These results suggest that male sex, a history of hypertension, and higher diastolic blood pressure could be factors increasing the likelihood of hypertensive crisis leading to organ damage. However, Vallelonga et al. did not find any significant differences in risk factors between HU and HE groups, including those significant in our results [

5].

The outcomes after admission were as expected. Most HU patients were discharged after ambulance treatment, although a small percentage (1.7%) required hospitalization due to difficulties in lowering blood pressure levels. The majority of HE patients with organ damage were hospitalized, with only a small number (4.5%) discharged. These discharged patients either refused hospitalization or had mild cerebrovascular incidents that did not require hospital treatment. Three percent of HE patients died either in the ambulance or during hospitalization. A recent meta-analysis by Shiddiqi et al. reported a higher in-hospital mortality rate for HE of 9% [

9]. Guiga et al. also found a similar mortality rate [

10]. A study investigating the outcome of hypertensive crisis patients admitted to the coronary care unit also found a higher hospital mortality rate in HE patients [

11].

Our mortality rate would likely have been higher if we had not excluded patients who died before completing data collection or diagnostic procedures. Additionally, the number of patients who died during transport to the ambulance was unknown.

The association between risk factors and outcomes after admission was not observed because most discharged patients were HU and hospitalized patients were HE, and all deceased patients had HE. This suggests that all risk factors significantly higher in the HE group (male sex, history of hypertension, higher diastolic blood pressure) could be considered enhancers of the risk for hospitalization and mortality at admission. Furthermore, patients without previously verified chronic hypertension were more likely to have their first hypertensive crisis resolve as HU without organ damage or hospital treatment.

Although the majority of patients had no complications during the six-month period after their hypertensive crisis, the results were still concerning. More than a third of patients (35%) had readmissions to medical services due to new episodes of elevated blood pressure or other cardiovascular events, ending either in discharge or death. The main cause of readmissions was new hypertensive crises, accounting for 32.3% of all readmissions. This rate is concerning compared to the 15.3% reported in a study with a much longer follow-up period [

7]. Additionally, a mortality rate of 8.64% cannot be overlooked. We attempted to investigate the reasons for these results and identify possible influencing factors. Although HU and HE patients had a similar proportion of patients without readmissions to medical services, the severity of new episodes differed, as evidenced by the significantly higher mortality rate in HE compared to HU patients (12.15% vs. 6.21%, respectively). Considering that the overall mortality rate of HE patients, including those who died during the first admission, was 15.15%, we conclude that patients with HE were almost twice as likely to experience a lethal outcome. The fact that there were a similar number of HU and HE patients among the deceased, despite the HE group being much larger, further confirms this. Other studies also found higher mortality rates in HE patients [

10,

12,

13].

Exploring the impact of risk factors on the six-month outcome, we found that only age was significantly higher in patients who had readmissions. The median age of patients without readmissions was 64, while in the other groups, it was 73 years. A trial conducted in HU patients found that age above 63 years was a risk factor for cardiovascular events [

14]. In another trial, age over 65 years was a risk factor for 30-day readmission in HE patients [

15]. Both groups of patients, those who died and those who survived after readmission, had a similar age profile. None of the other investigated factors (sex, dyslipidemia, history of diabetes, and chronic hypertension) could be considered risk factors for readmission. This also applied to the severity and outcome of events. Studies focused on sex-related outcomes of hypertensive crisis had contradictory results. Conclusions varied, with some studies suggesting that men [

16] or women [

14,

15] had more cardiovascular events. However, these trials focused on only one type of hypertensive crisis (HE or HU, respectively) and had different follow-up periods.

Conclusion

Male sex and higher diastolic blood pressure (DBP) are identified as risk factors for hypertensive emergency (HE), suggesting a higher likelihood of hospital treatment and increased intrahospital mortality. Patients with HE also exhibit a higher risk of a lethal outcome within six months. Advanced age is associated with an increased risk of six-month readmission and a lethal outcome.

Conflict of interest

None

Ethical approvement

Not required

References

- van den Born BH, Lip GYH, Brguljan-Hitij J, Cremer A, Segura J, Morales E, Mahfoud F, Amraoui F, Persu A, Kahan T, Agabiti Rosei E, de Simone G, Gosse P, Williams B. ESC Council on hypertension position document on the management of hypertensive emergencies. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Pharmacother. 2019 Jan 1;5(1):37-46. Erratum in: Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Pharmacother. 2019 Jan 1;5(1):46. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ipek E, Oktay AA, Krim SR. Hypertensive crisis: an update on clinical approach and management. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2017 Jul;32(4):397-406. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, Casey DE Jr, Collins KJ, Dennison Himmelfarb Cet al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA Guideline for the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Hypertension. 2018 Jun;71(6):e13-e115. . Epub 2017 Nov 13. Erratum in: Hypertension. 2018 Jun;71(6):e140-e144. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Astarita A, Covella M, Vallelonga F, Cesareo M, Totaro S, Ventre L, Aprà F, Veglio F, Milan A. Hypertensive emergencies and urgencies in emergency departments: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Hypertens. 2020 Jul;38(7):1203-1210. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vallelonga F, Cesareo M, Menon L, Leone D, Lupia E, Morello F, Totaro S, Aggiusti C, Salvetti M, Ioverno A, Maloberti A, Fucile I, Cipollini F, Nesti N, Mancusi C, Pende A, Giannattasio C, Muiesan ML, Milan A. Hypertensive emergencies and urgencies: a preliminary report of the ongoing Italian multicentric study ERIDANO. Hypertens Res. 2023 Jun;46(6):1570-1581. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan SH, Slusser JP, Hodge DO, Chen HH. The Vascular-Renal Connection in Patients Hospitalized With Hypertensive Crisis: A Population-Based Study. Mayo Clin Proc Innov Qual Outcomes. 2018 Mar 15;2(2):148-154. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saguner AM, Dür S, Perrig M, Schiemann U, Stuck AE, Bürgi U, Erne P, Schoenenberger AW. Risk factors promoting hypertensive crises: evidence from a longitudinal study. Am J Hypertens. 2010 Jul;23(7):775-80. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin YT, Liu YH, Hsiao YL, Chiang HY, Chen PS, Chang SN, Tsai HC, Chen CH, Kuo CC. Pharmacological blood pressure control and outcomes in patients with hypertensive crisis discharged from the emergency department. PLoS One. 2021 Aug 17;16(8):e0251311. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siddiqi TJ, Usman MS, Rashid AM, Javaid SS, Ahmed A, Clark D 3rd, Flack JM, Shimbo D, Choi E, Jones DW, Hall ME. Clinical Outcomes in Hypertensive Emergency: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Am Heart Assoc. 2023 Jul 18;12(14):e029355. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guiga H, Decroux C, Michelet P, Loundou A, Cornand D, Silhol F, Vaisse B, Sarlon-Bartoli G. Hospital and out-of-hospital mortality in 670 hypertensive emergencies and urgencies. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2017 Nov;19(11):1137-1142. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González Pacheco H, Morales Victorino N, Núñez Urquiza JP, Altamirano Castillo A, Juárez Herrera U, Arias Mendoza A, Azar Manzur F, Briseño de la Cruz JL, Martínez Sánchez C. Patients with hypertensive crises who are admitted to a coronary care unit: clinical characteristics and outcomes. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2013 Mar;15(3):210-4. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashraf M, Zlochiver V, Bolton A, Allaqaband SQ, Bajwa T, Jan MF. Thirty-Day Readmission Rate Among Patients With Hypertensive Crisis: A Nationwide Analysis. Am J Hypertens. 2022 Oct 3;35(10):852-857. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paini A, Tarozzi L, Bertacchini F, Aggiusti C, Rosei CA, De Ciuceis C, Malerba P, Broggi A, Perani C, Salvetti M, Muiesan ML. Cardiovascular prognosis in patients admitted to an emergency department with hypertensive emergencies and urgencies. J Hypertens. 2021 Dec 1;39(12):2514-2520. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel KK, Young L, Howell EH, Hu B, Rutecki G, Thomas G, Rothberg MB. Characteristics and Outcomes of Patients Presenting With Hypertensive Urgency in the Office Setting. JAMA Intern Med. 2016 Jul 1;176(7):981-8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar N, Simek S, Garg N, Vaduganathan M, Kaiksow F, Stein JH, Fonarow GC, Pandey A, Bhatt DL. Thirty-Day Readmissions After Hospitalization for Hypertensive Emergency. Hypertension. 2019 Jan;73(1):60-67. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fragoulis C, Polyzos D, Dimitriadis K, Konstantinidis D, Mavroudis A, Tsioufis PA, Leontsinis I, Kariori M, Drogkaris S, Tatakis F, Manta E, Siafi E, Papakonstantinou PE, Zamanis I, Mantzouranis E, Thomopoulos C, Tsioufis KP. Sex-related cardiovascular prognosis in patients with hypertensive emergencies: a 12-month study. Hypertens Res. 2023 Mar;46(3):756-761. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).