Submitted:

26 April 2024

Posted:

29 April 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

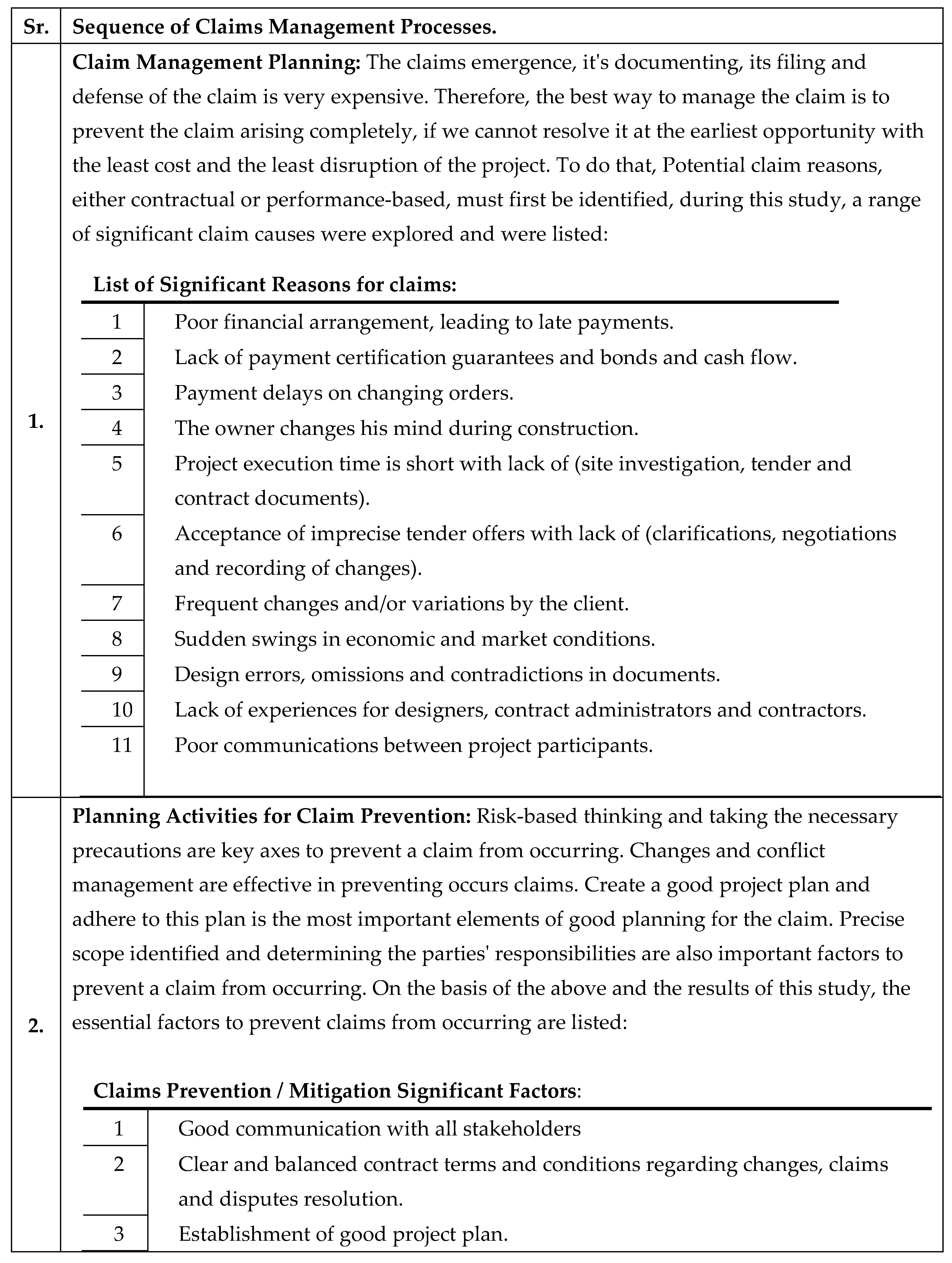

1.1. Claim Management Planning

1.2. Claim Reasons

1.3. Claims Prevention / Mitigation

- Create a good project plan.

- Fairly drafted provisions of the contract that allowed for potential modifications.

- Create a good Risk Management Plan.

- Integrated Change Control.

- Clarity of Language: The language used in writing the contract's specifications and

- Scope should be precise and unambiguous.

- Constructability Review.

- Request for Information (RFI) Procedure.

- Project Partnering.

- Prequalification Process.

- Claim Prevention Techniques: (Dispute review board (DRB), Independent neutral,

- Intervention, partnering, Mediation.

- Good documentation.

- Joint Recognition of Change.

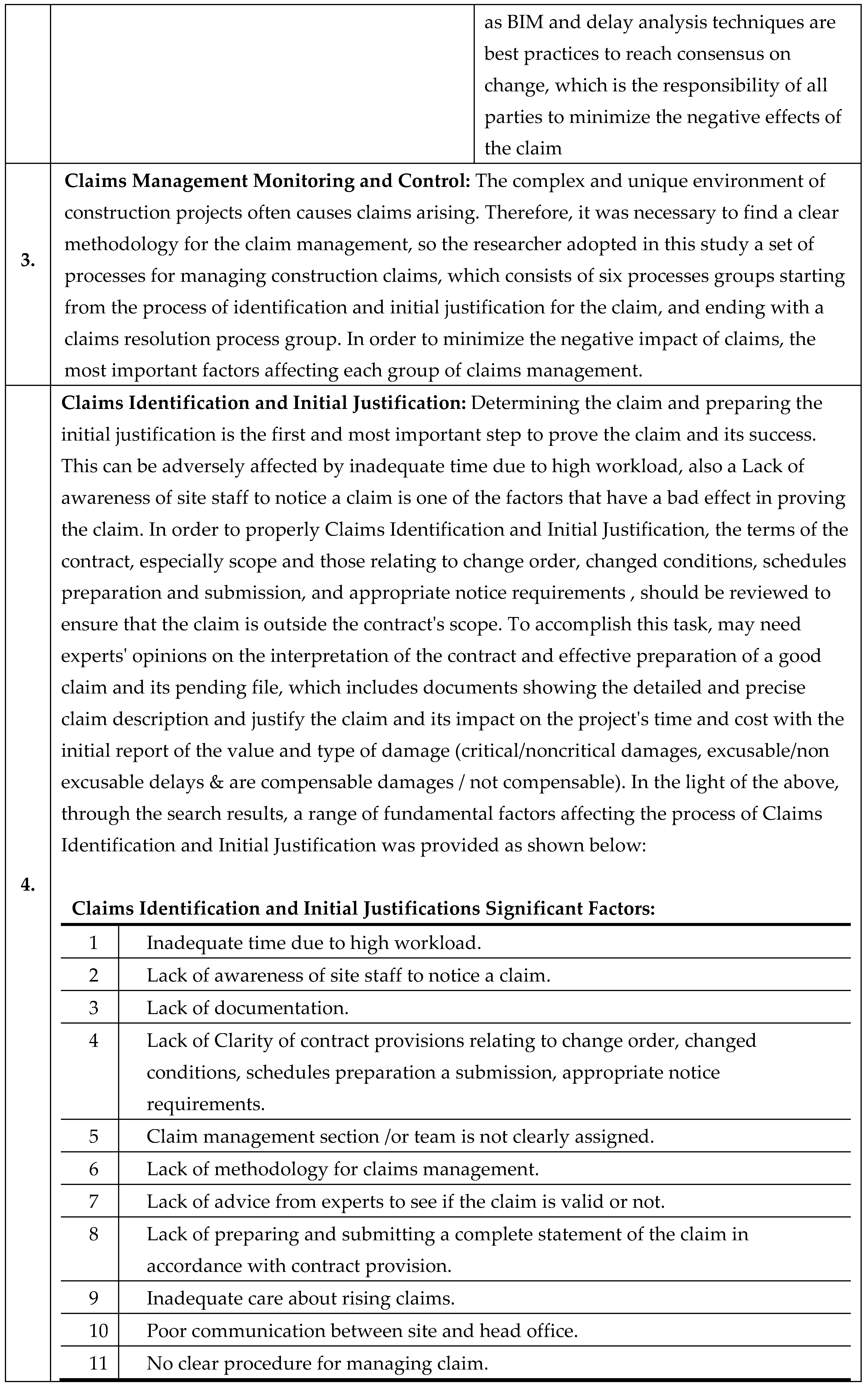

1.4. Claims Management Monitoring and Controlling

1.5. Claims Identification and Initial Justification

- Project scope and contract.

- Description of claim.

- Time and cost impacts.

- Prompt payments.

- Capability gap analysis.

- Expert judgment.

- Documentation.

- Pending Claim file and statement of claim.

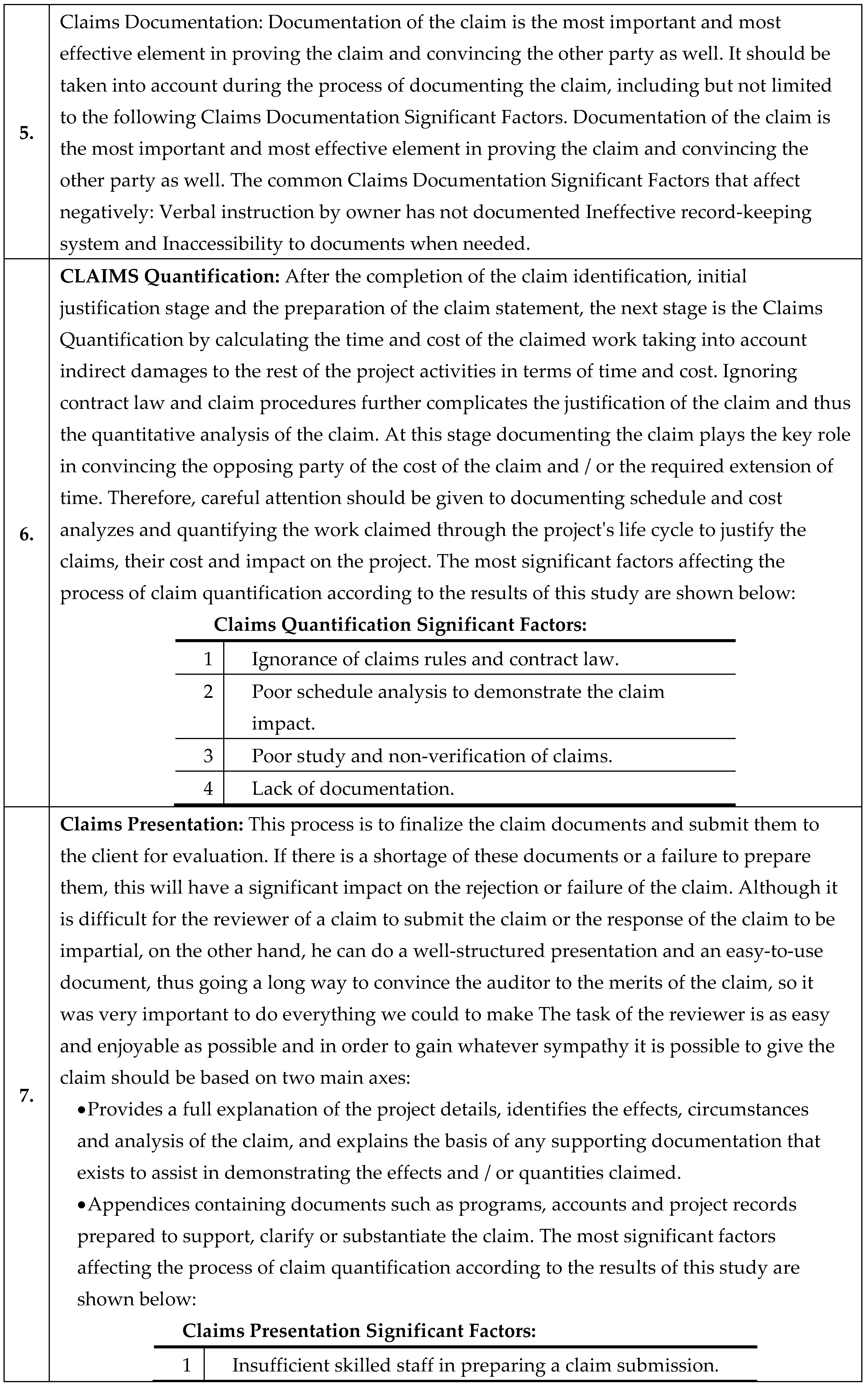

1.6. Claim Documentation

- Tender and contract documentation.

- Issued for Construction set, and all subsequent revisions.

- Instructions to contractor.

- Contemplated Change Notices issued by the owner, Change Estimates, and Change Orders received.

- Sub-contractor quotes, contracts, purchase orders and correspondence.

- Shop drawings, originals, all revisions and re-submissions.

- Shop drawing transmittals, and transmittals log.

- Daily time records.

- Daily equipment use.

- Daily record of labor and plant staff, etc.

- Material Delivery and Use Records, including expediting.

- Accounting records: pay-roll, accounts payable and receivable, etc.

- Progress Payment Billings under the contract.

- Daily Force Account Records, pricing and billings.

- Contract Milestone Schedule or Master Schedule.

- Short Term Schedules and up-dates.

- Task schedules and analyses.

- Original tender estimate.

- Construction control budget.

- Actual Cost Reports, weekly or monthly, includes Exception Reports.

- Forecast-to-Complete Estimate up-dates.

- Productivity Reports/Analyses.

- Inter-office correspondence, including memos and faxes (all filed by topic).

- Contract correspondence.

- Minutes of Contractual Meetings.

- Minutes of Site Coordination Meetings.

- Requests for information.

- Notice of claims for delays and/or extra cost by contractor.

- Government Inspection Reports.

- Consultant Inspection Reports.

- Accident Reports.

- Daily diary or journal entries.

- Notes of telephone conversations.

- Progress Reports, weekly, monthly or quarterly, Progress Photographs.

1.7. Claim Quantification

1.8. Claim Presentation

- A full explanation of the project details identifies the effects, circumstances, and analysis of the claim, and explains the basis of any supporting documentation that exists to assist in demonstrating the effects and / or quantities claimed.

- Appendices containing documents such as programs, accounts and project records are prepared to support, clarify, or substantiate the claim.

1.9. Claim Negotiation

2. Claim Resolution

- Negotiation.

- Conciliation.

- Mediation.

- Mini-Trial.

- Dispute Adjudication Board.

- Procedure Pre-arbitral.

3. Materials and Methods

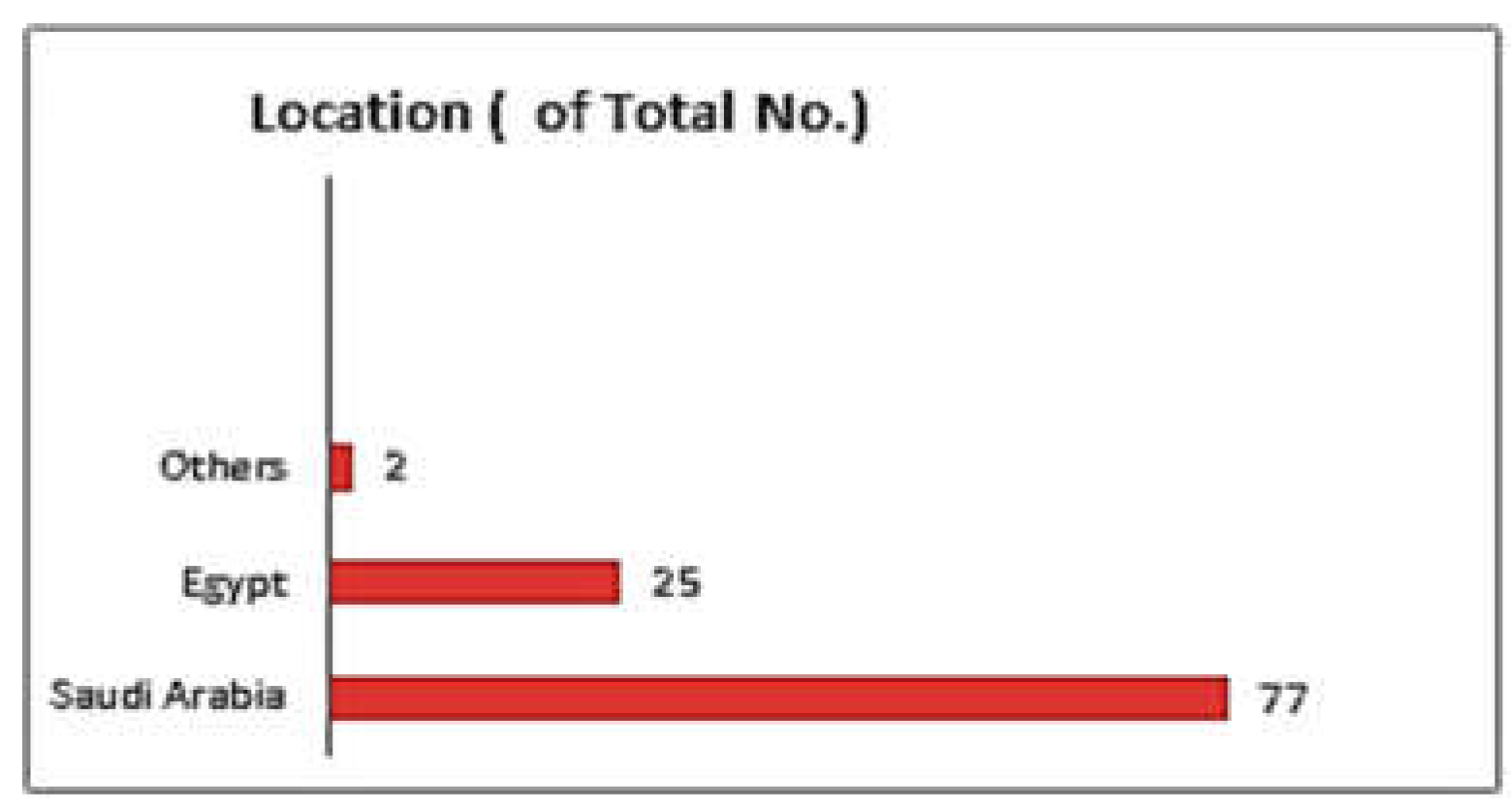

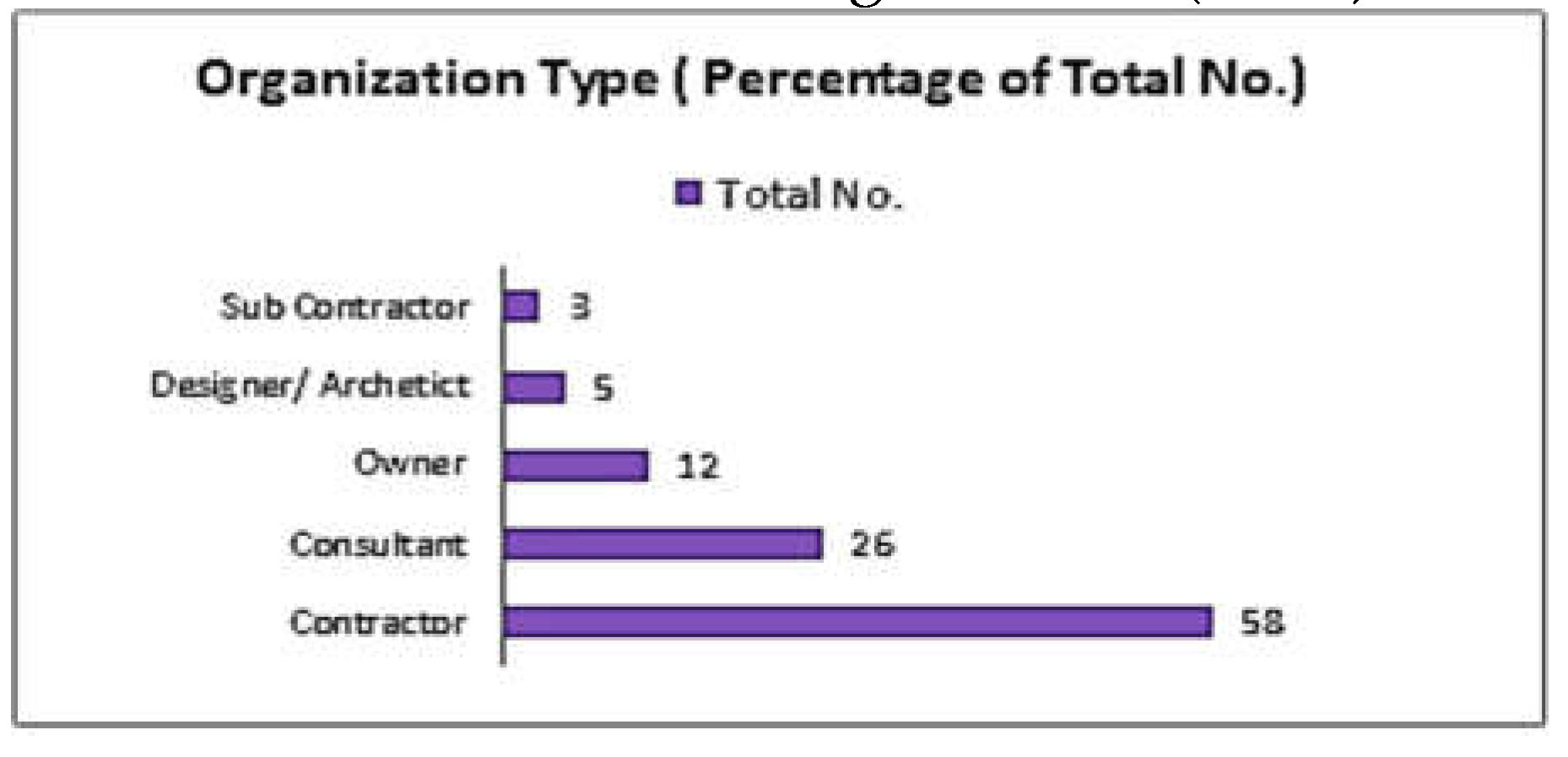

3.1. Research Methodology

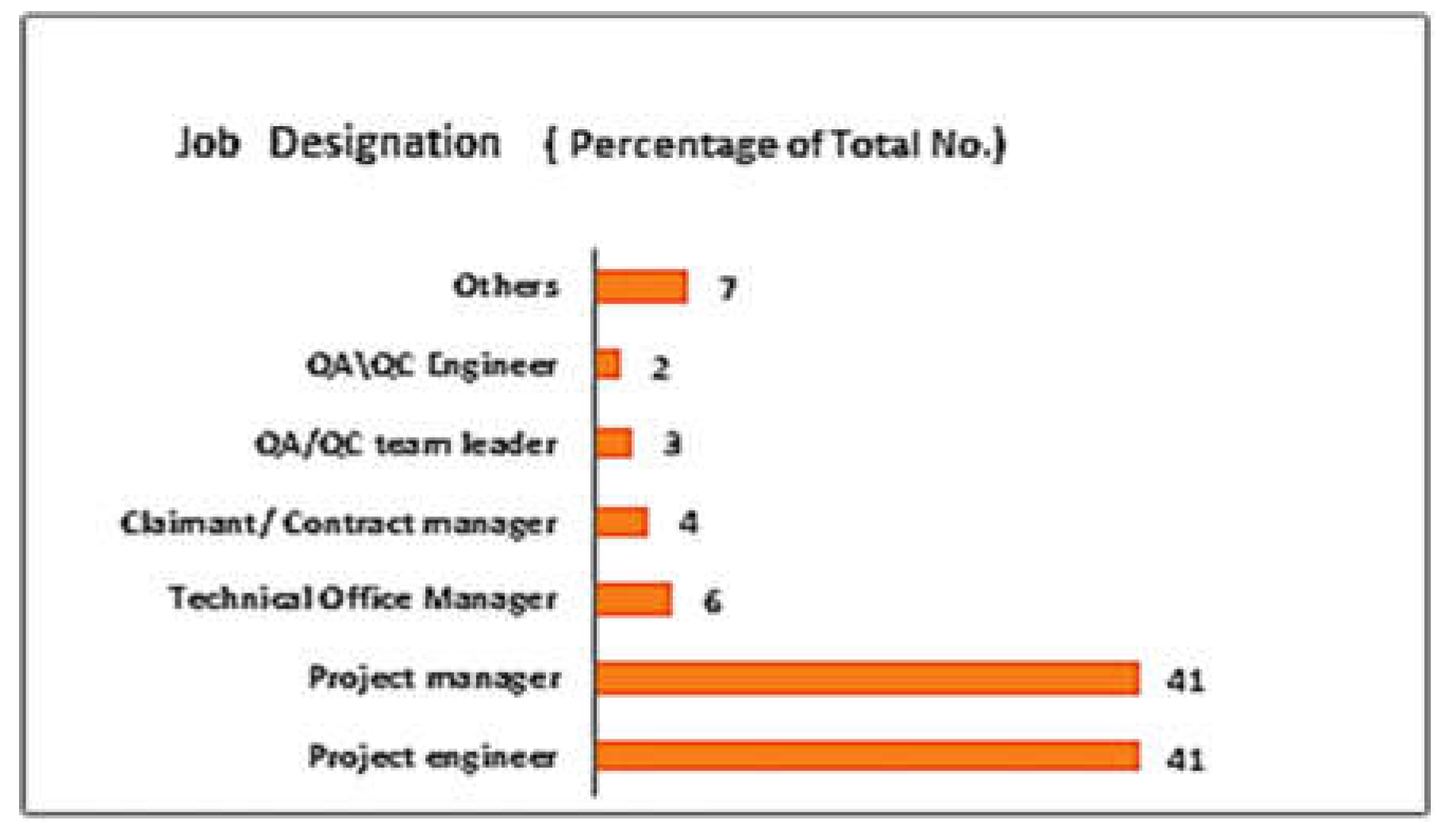

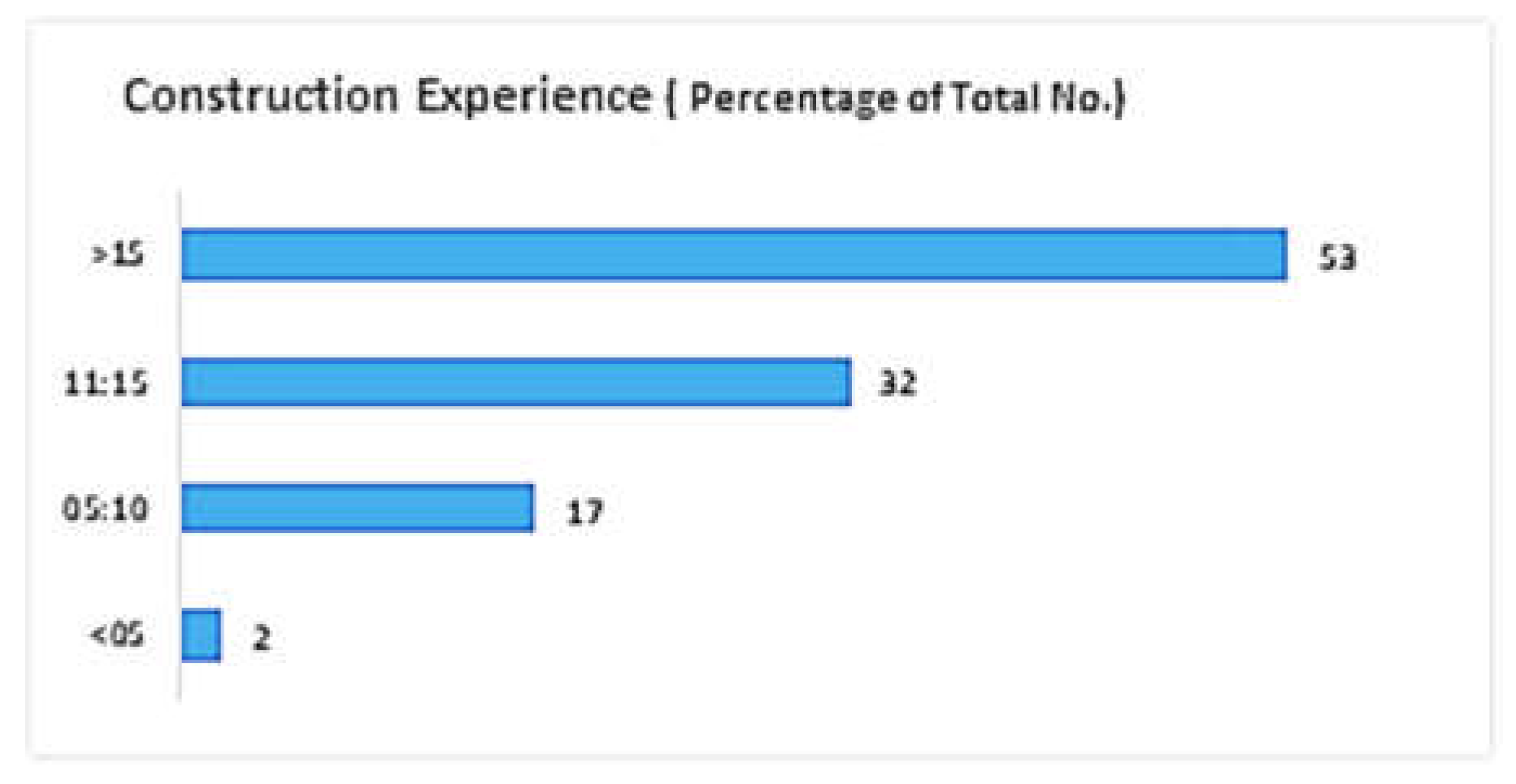

- The first section of this questionnaire explores information about respondent's profile such as their position, work experiences, types of projects that they are involved in and the types of contracts that they have used.

- The second section is planning for claims include questions related to the issues in construction claim planning such as the common types of claim in construction projects and claims prevention / mitigation.

- The third section aims to determine the problems that arise in every stage of the claim process from the first stage of identification of claim to the final stage of resolution.

- The fourth section includes questions asking the respondents to share their ideas, comments, and suggestions on how to improvise the claim management process. The aim of this section is together the expert opinions on the process of improving claim management.

- To analyze the data collected regarding the reasons of the claims from the questionnaire, we utilized the Modified Fuzzy Group Decision-Making Approach (FGDMA). This method was particularly chosen for its ability to effectively handle the uncertainties and subjective nature of the responses. By applying FGDMA, we were able to systematically prioritize the various factors and challenges identified, thus providing a solid foundation for developing more effective claim management strategies tailored to the nuanced needs of the construction industry.The distribution of the questionnaire was designed to be run through website. The respondents were requested to evaluate the attributes based on a 5-point Likert Scale (1=Very Low, 2=Low, 3=Moderate, 4= High, 5=Very High).

3.2. Sample Size Determination

- SS= sample size

- Z= confidence level (the number of standard deviations a given proportion is away from the mean), Z value (e.g., 1.64 for 0.9495 ≈95% confidence level)

- P= Percentage picking a choice, expressed as a decimal (0.50 used for sample -size needed).

4. Data Collection and Results Analysis

4.2. Evaluation of Claim Management Attributes using Statistical Analysis (Ranking Approach)

- Descriptive analysis for Respondents’ Profile.

- Cronbach's alpha for reliability statistics.

- Significant Factors’ Heat Map (Pearson Correlation Coefficient of Significant Factors).

4.2.1. Relative Importance Index (RII)

4.2.2. Frequency Index (FI)

4.2.3. Frequency Adjusted Importance Index (FAII)

4.2.4. Significant Factors Heat Map

4.3. Evaluation of Construction Claim Management Attributes.

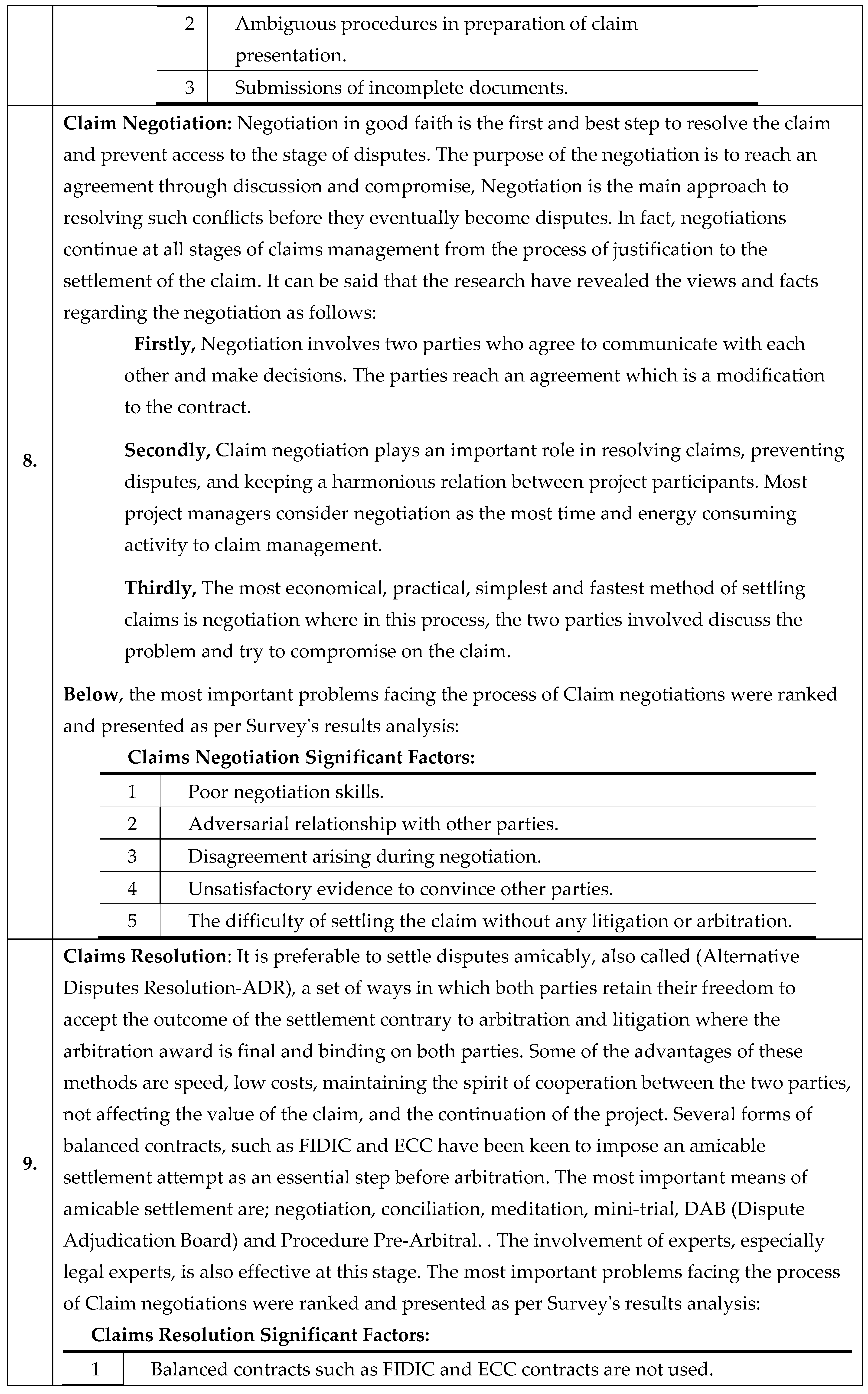

4.3.1. Significant Factors

5. Pearson Correlation Coefficient of Significant Factors

- All relationships between factors are positive; this reflects the Proportionality between these factors.

- All P-values are less than 0.05, which means that all relationships are statistically significant. Except for three value/ cells had been filled in Brown between factor XM3 and both factor (YN4 & YR1) as well as between factor XM7 and factor YR1, which indicated that the presence of one of these factors was not related to the existence of each other. There were 55 relationships (40.44 % of all relationships) with very strong relationship (Pearson correlation coefficient r > 0.5). There were 67 relationships (49.26% of all relationships) with a strong correlation (Pearson correlation coefficient 0.5> r> 0.3). From the previous values, it can be said that 90% of correlation coefficient values range from very strong to strong and this reflects the correlation between these factors and each other. This means that if one factor affects claim management process, other factors may have a significant impact on these processes of claim management. It is important to take into account these relationships, which must be followed through the claim management process groups. Pearson correlation coefficient values revealed that the strongest correlation between XM3 (Good communication with all stakeholders) and XM7 (Clear and balanced contract terms and conditions regarding changes, claims and disputes resolution) with r =0.762, and YN1 (Disagreement arising during negotiation.), YN2 (Unsatisfactory evidence to convince other parties) with r = 0.718, also between YR7 (balanced contracts such as FIDIC and ECC contracts are not used.), YR8 (The terms of contract don't focus on good management and effective risk distribution) with r =0.723. The results above show that the most factors associated with the 17 significant factors are YN1, YN2, YR3, where each factor was correlated with all other factors with very strong or strong relationship. This reflects the importance of negotiating skills and reaching agreement during the negotiation process to resolve the claim, as well as having adequate evidence to prove the claim; all were the most significant factors in the process of managing claims. It is clear that strong relationships between the highest factors are logical and justified, as well as the reliability of the information obtained from the questionnaire and the seriousness of the respondents in answering the questionnaire.

5.1. Pearson Correlation Coefficient for Significant Factors with Their Groups

5.1.1. Significant Factors by Groups

| Code | RII | RII Rank | RII Rank by Group | FI | FI Rank | FI Rank by Group | FAII | FAII Rank | FAII Rank by Group | Significant level |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| XR | Reasons of Claims | |||||||||

| XR19 | 0.815 | 2 | 1 | 63.85 | 22 | 31.4 | 52.06 | 19 | 1 | High |

| XR31 | 0.788 | 11 | 2 | 65.77 | 35 | 41.9 | 51.86 | 23 | 2 | High |

| XR28 | 0.748 | 41 | 8 | 67.31 | 34 | 40 | 50.35 | 33 | 3 | High |

| XR18 | 0.738 | 54 | 11 | 68.08 | 30 | 41 | 50.27 | 34 | 4 | High |

| XR1 | 0.785 | 12 | 3 | 62.69 | 20 | 47.6 | 49.19 | 38 | 5 | High |

| XR2 | 0.785 | 12 | 3 | 62.69 | 28 | 44.8 | 49.19 | 38 | 5 | High |

| XR7 | 0.721 | 68 | 16 | 65.58 | 35 | 42.9 | 47.29 | 50 | 7 | High |

| XR5 | 0.767 | 23 | 5 | 60.58 | 21 | 31.4 | 46.48 | 56 | 8 | High |

| XR27 | 0.763 | 25 | 6 | 60.77 | 28 | 43.8 | 46.39 | 57 | 9 | High |

| XR4 | 0.748 | 41 | 8 | 61.92 | 29 | 41 | 46.32 | 58 | 10 | High |

| XR8 | 0.727 | 65 | 15 | 63.08 | 28 | 41 | 45.85 | 59 | 11 | High |

5.1.2. Claims Prevention / Mitigation Significant Factors

5.1.3. Claims Identification and Initial Justification of Significant Factors

5.1.4. Claims Documentation Significant Factors

5.1.5. Claims Quantification Significant Factors

5.1.6. Claims Presentation Significant Factors

5.1.7. Claims Negotiation Significant Factors

5.1.8. Claims Resolution Significant Factors

5.2. Discussion of Statistical Results

5.2.1. Claims Quantifications

- The contract remains the main baseline for resolving claims that may. Therefore, the use of balanced contracts such as FIDIC or ECC contracts largely guarantees the effective distribution of risks for the contract parties, subject to the law of the contract. Respondents also agreed on the importance of adopting a process for managing the contractual claims. As well as the inclusion of contractual clauses guarantee the use of alternative dispute resolution (ADR) methods or specific litigation prevention techniques, including the settlement of disputes such as; mediation, arbitration, mini-trials, DRBs and other global alternatives.

- The pending claim files and statement of claim are good practice to ensure that information and all relevant documents have been collected and retained in an accessible file or database, this proactive approach helps to prove the claim and perform the preliminary claim analysis, as well as preparing a statement of claim in accordance with the procedures described under the contract. Therefore, lack of the Statement of claims, contract and Claims quantifications was one of the most important factors evaluated by the respondents, which affect the claims management process.

- Communications with all parties involved in the construction process is one of the most important preventive factors that limit the occurrence of claims, the early detection of problems and communication with the concerned parties to resolve. Respondents' opinions confirmed that good communication with all stakeholders one of the key factors in the claim management process, where it ranked ninth with FAII (54.568%).

- Tracking the project schedule, analyzing and documenting project delays and determining its impact on the time and cost of the project, are key factors to estimate and prove the claim. Respondents agreed that (the impact of claims on the project table is not documented) is one of the most important factors in claims management process. Where it ranked tenth with FAII (54.384%). Since assessing the claim is not an easy matter and failure in it negatively affects the process for resolving the claim, therefore the use of experts to submit a report on the evaluation of the claim clarifying the effect of time and cost as a result of the work claimed, whether it is additional work or inconsistency in the documents is considered a positive matter to resolve the claim easily, So in this research, the experts ’opinion came in line with that fact, as the Lack of expert report or Claim assessment ranked eleventh in relation to the significant factors affecting the claims management with FAII (54.25%).

- The implication of the contract was considered unproductive in terms of its legal effect, except for identified obligations of all parties had been involved in this contract, whether a contractor, owner, consultant, or subcontractor ... etc. identifying the limits of obligations, roles and responsibilities for each party, as well as determining the type of commitment whether it is An obligation to achieve a result or an obligation to do care, because identifying such elements plays a major role in claiming compensation for default in this commitment, when it was not specified clear it became difficult to resolve this claim, it’s may loss between the claiming parties. Since this factor is a great importance, the respondents' opinion came to put this factor (The roles and responsibilities of contracting parties are not identified) in the twelfth rank within the group of seventeen significant factors covered by this research with FAII (54.25%).

- Seeking experts' advice on preparing, analyzing, supporting the claim with the required documents, evaluating them in technical and legal terms, and the feasibility of this claim.

- It has a profound impact on resolving the claim, before changing it to a dispute, this requires the fully documented certified claims for the purpose of quantifying the impact of the claim and requesting an extension of time. This document shall include all documents supporting the claim. Therefore, according to the respondents' evaluation in this research, this factor (Expert knowledge and fully documented certified claims are not taken into consideration) was considered to be very effective in the process of managing and settling claims, as it ranked thirteenth of the group of seventeen, the most significant factors with FAII (53.68%).

- The Effective distribution of risks, assigning to the party who is able to manage it, by following a win-win situation is considered one of the most important factors for the projects' success, avoiding claims, and claims' settling easily. Therefore, it is found, according to the results of this research, that (The terms of contract don't focus on good management and effective risk distribution) was ranked the sixteenth among the seventeen significant factors in the claims’ management with FAII (52.84%).

- The results shows also, that the claims prevention / mitigation group contributed by two main factors within the group of the most important seventeen factors to this research, as the attribute (Good communication with all stakeholders) ranked ninth with FAII’s percentage (54.57%), where this factor represents of great importance towards creating a collaborative work environment, effective communication among the parties, that guarantees the of problems’ solution just in time they arise , avoids changing them into a difficult solved claim , and thus turns into a dispute.

- The attribute (Clear and balanced contract terms and conditions regarding changes, claims and disputes resolution) came in the seventeenth rank with FAII’s percentage (52.34%), as clarity of the terms and conditions of the contract regarding the changes and methods of resolving claims and settling disputes ensures an agile management, allows accepted contract’s changes by all parties to avoid a dispute.

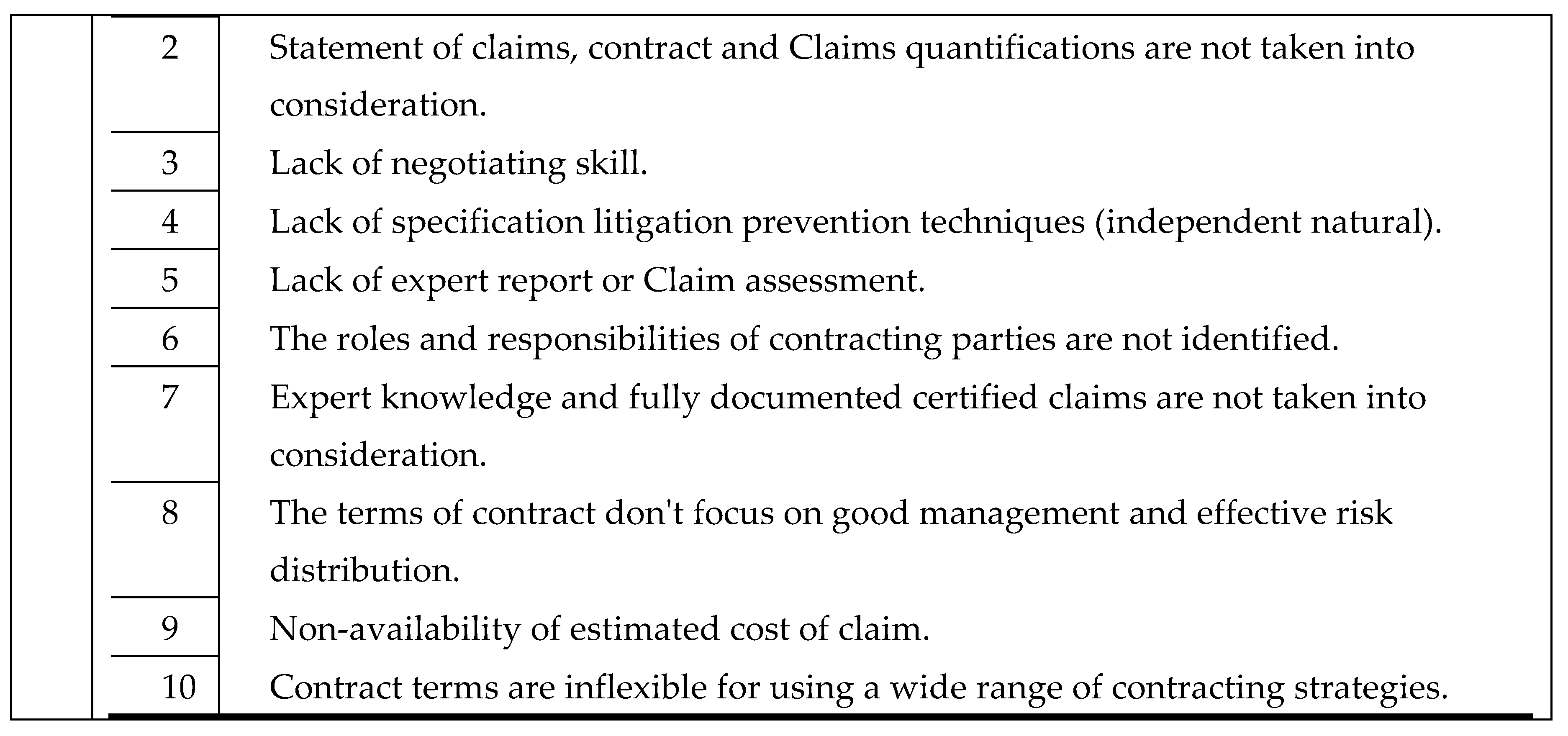

5.3. Fuzzy Group Decision Making Approach

- (a)

- Step 1 - Application of Fuzzy Triangular Numbers (FTNs): This step involves converting linguistic risk and importance assessments into quantitative fuzzy triangular numbers (FTNs), each represented as a triplet (l, m, u). These numbers capture the range of potential outcomes from pessimistic to optimistic estimates, reflecting the subjective nature of expert judgments.

- (b)

- Step 2 - Fuzzy Decision Matrix (FDM) Construction: An FDM is established for each claim reason, assessing its frequency (RF) or importance (RI) based on expert evaluations. Each element in the FDM represents an FTN associated with a claim reason:

6. Conclusions

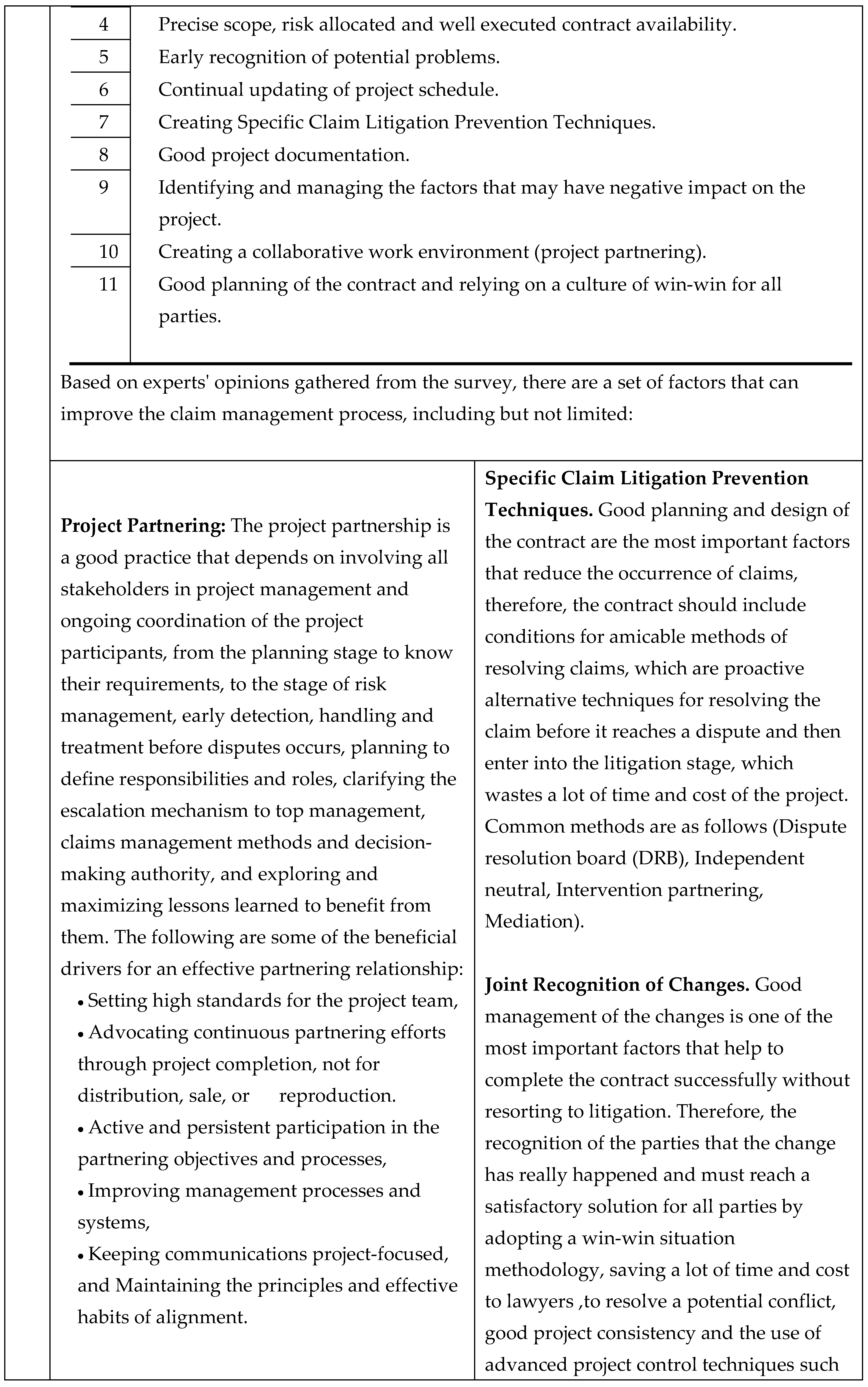

6.1. Concluding Remarks on Sequence of Processes for Managing Construction Claims

7. Recommendations

- Contractors, Clients and Consultants establish an independent department for claims management, appointing qualified experienced claimants, arbitrators, jurists and specialists, and set up a mechanism to ensure effective and continuous coordination between this department and all project department throughout the project life cycle.

- Creating a database supports the claims management process, includes the factors causing the claims as well as the important factors to avoid claims and lessons learned in the different projects throughout the project life cycle, ensuring information is shared among the employees of different project sections to increase their awareness regarding claims management.

- Organizations working in the construction better develop an information and communication technology support for claim management, developer of a Web-based Construction Claims Management System, these systems provide at least (tracking status of claims & one reminder function & central data to access information about all claims from geographically dispersed offices).

- To ensure that the objectives are executed, reviewed, monitored, and controlled in order to meet the requirements of the stakeholders, a comprehensive project management plan is advised. This plan should include a clearly defined and meticulously detailed scope of work, a reasonable schedule, an appropriate method of project execution specific to the type of project, and an acceptable degree of risk involved to contribute to the elimination of claims.

- Owners and contractors are recommended to use nontraditional adaptive balanced contracts, are (flexible, clear and simple, focus on good governance, effective and fair risk distribution to the contract parties), flexible change management, have a methodology and time frames for claims and dispute management, separates of roles and responsibilities includes at least the roles of the (owner representative, designer, execution supervisor, judicial arbitrator), Alternative dispute resolution methods).

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- T. M. H. P. ENG and W. Menesi, “Delay analysis considering dynamic resource allocation and multiple baselines,” AACE Int. Trans., p. CD141, 2008.

- C. Linnett and S. Lowsley, About time: Delay Analysis in Construction. RICS, 2006.

- A. S. Faridi and S. M. El-Sayegh, “Significant factors causing delay in the UAE construction industry,” Construction Management and Economics. vol. 24, no. 11, pp. 1167–1176, Nov. 2006. [CrossRef]

- M. S. B. A. Abd El-Karim, O. A. Mosa El Nawawy, and A. M. Abdelalim, “Identification and assessment of risk factors affecting construction projects,” HBRC J., vol. 13, no. 2, pp. 202–216, Aug. 2017. [CrossRef]

- “2022 Global Construction Disputes Report.” Accessed: Jan. 30, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.arcadis.com/en/knowledge-hub/perspectives/global/global-construction-disputes-report.

- E. Yousri, A. E. B. Sayed, M. A. M. Farag, and A. M. Abdelalim, “Risk Identification of Building Construction Projects in Egypt,” Buildings, vol. 13, no. 4, p. 1084, Apr. 2023. [CrossRef]

- P. Mitropoulos and G. Howell, “Model for Understanding, Preventing, and Resolving Project Disputes,” J. Constr. Eng. Management, vol. 127, no. 3, pp. 223–231, Jun. 2001. [CrossRef]

- Sherif and Abdelalim, A. M. , “Delay Analysis Techniques and Claim Assessment in Construction Projects,” Jan. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D. Richbell, Mediation of Construction Disputes, 1st ed. Wiley, 2008. [CrossRef]

- Project Management Institute (Ed.) , Construction extension to the PMBOK guide, 3rd. Ed. Newtown Square, Pa: Project Management Institute, 2007.

- K. O. Alloh, “Investigating of factors causes claims creation in construction projects in the Gaza Strip-Palestine,” Awantipora India Islam. University, 2014.

- Abdelalim, A. M. , “Risks Affecting the Delivery of Construction Projects in Egypt: Identifying, Assessing and Response,” in Project Management and BIM for Sustainable Modern Cities, M. Shehata and F. Rodrigues, Eds., in Sustainable Civil Infrastructures., Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2019, pp. 125–154. [CrossRef]

- R. E. A. Younis, H. Abdelkhalek, and A. M. Abdelalim, “Project Risk Management during Construction Stage According to International contract (FIDIC),” Feb. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Abdelalim, A. M., E. Elbeltagi, and A. A. Mekky, “Factors affecting productivity and improvement in building construction sites,” Int. J. Productivity and Quality Management., vol. 27, no. 4, p. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khedr, R. and Abdelalim, A.M., 2021, “Predictors for the Success and Survival of Construction Firms in Egypt”, International Journal of Management and Commerce Innovations ISSN 2348-7585 (Online), Vol. 9, Issue 2, pp.: (192-201).

- Khedr, R. and Abdelalim, A.M., 2021, “The Impact of Strategic Management on Projects Performance of Construction Firms in Egypt”, International Journal of Management and Commerce Innovations ISSN 2348-7585 (Online) Vol. 9, Issue 2, pp.: (202-211).

- P. Levin (Ed.) P. Levin, Ed., Construction contract claims, changes, and dispute resolution, Third edition. Reston, Virginia: American Society of Civil Engineers, 2016.

- N. A. Bakhary, H. Adnan, and A. Ibrahim, “A Study of Construction Claim Management Problems in Malaysia,” Procedia Econ. Finance, vol. 23, pp. 63–70, 2015. [CrossRef]

- M. A. Hassan, “CAUSES OF DELAY IN CONSTRUCTION PROJECTS,” 2016.

- Enshassi, S. Mohamed, and S. Abushaban, “FACTORS AFFECTING THE PERFORMANCE OF CONSTRUCTION PROJECTS IN THE GAZA STRIP,” J. Civ. Eng. Management, vol. 15, no. 3, pp. 269–280, Jun. 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Elghandour, “Claims Causes and Management Process in the Construction Industry in the Gaza Strip,” Islamic University of Gaza, Palestine, 2006.

- G. Nassar, Claims, Disputes and Arbitration, Cairo Regional Center for International Commercial Arbitration (CRCICA), 2001.

- International Federation of Consulting Engineers, Ed., The FIDIC contracts guide: with detailed guidance on using the first editions of FIDIC’s; conditions of contract for construction, conditions of contract for plant and design-build, conditions of contract for EPC/ turnkey projects, First edition. Geneva: FIDIC, 2000.

- F. Al Bahi, Statistical Psychology. Measuring the Human Mins. Dar Al-Fikr Al-Arabi, 1979.

- J. F. Hair Jr, M. Sarstedt, L. Hopkins, and V. G. Kuppelwieser, “Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM): An emerging tool in business research,” Eur. Bus. Rev., vol. 26, no. 2, pp. 106–121, Mar. 2014. [CrossRef]

- F. H. Mustapha and S. Naoum, “Factors influencing the effectiveness of construction site managers,” Int. J. Project Management, vol. 16, no. 1, pp. 1–8, Feb. 1998. [CrossRef]

- M. Odeh and H. T. Battaineh, “Causes of construction delay: traditional contracts,” Int. J. Project Management, vol. 20, no. 1, pp. 67–73, Jan. 2002. [CrossRef]

- S. M. El Dean and A. M. Abdelalim, “A Proposed System for Prequalification of Construction Companies & Subcontractors for Projects in Egypt,” Int. J. Management and Commerce Innovations. vol. 9, no. 2, 2021.

- M. S. Islam, M. P. Nepal, and M. Skitmore, “Modified Fuzzy Group Decision-Making Approach to Cost Overrun Risk Assessment of Power Plant Projects,” J. Constr. Eng. Manag., vol. 145, no. 2, p. 04018126, Feb. 2019. [CrossRef]

- R. Tavakkoli-Moghaddam, S. M. Mousavi, and H. Hashemi, “A fuzzy comprehensive approach for risk identification and prioritization simultaneously in EPC projects,” Risk Management Environ. Prod. Econ., vol. 12, pp. 123–46, 2011.

- Y. Li and X. Wang, “Risk assessment for public–private partnership projects: using a fuzzy analytic hierarchical process method and expert opinion in China,” J. Risk Res., vol. 21, no. 8, pp. 952–973, Aug. 2018. [CrossRef]

- M. Aboshady, M. M. G. Elbarkouky, and M. M. Marzouk, “A Fuzzy Risk Management Framework for the Egyptian Real Estate Development Projects,” pp. 344–353, Apr. 2013. [CrossRef]

- E. E. Ameyaw, A. P. C. Chan, O.-M. De-Graft, and E. Coleman, “A fuzzy model for evaluating risk impacts on variability between contract sum and final account in government-funded construction projects,” J. Facilities Management., vol. 13, no. 1, pp. 45–69, 2015.

- J. H. Jung, D. Y. Kim, and H. K. Lee, “The computer-based contingency estimation through analysis cost overrun risk of public construction project,” KSCE J. Civ. Eng. , pp. 1–12, 2015. [CrossRef]

- M. Abdelgawad and A. R. Fayek, “Risk Management in the Construction Industry Using Combined Fuzzy FMEA and Fuzzy AHP,” J. Constr. Eng. Management., vol. 136, no. 9, pp. 1028–1036, 2010. [CrossRef]

- Y. Xu, J. F. Y. Yeung, A. P. C. Chan, D. W. M. Chan, S. Q. Wang, and Y. Ke, “Developing a risk assessment model for PPP projects in China-A fuzzy synthetic evaluation approach,” Automation in Construction , vol. 19, no. 7, pp. 929–943, 2010. [CrossRef]

- Abd El-Hamid, S.M, Farag, S., Abdelalim, A.M., 2023, “Construction Contracts’ Pricing according to Contractual Provisions and Risk Allocation”, International Journal of Civil and Structural Engineering Research ISSN 2348-7607, Vol.11, Issue.1, pp.11-38. [CrossRef]

- Abdelalim, A.M. and Said, S.O.M., 2021. “Dynamic labor tracking system in construction project using BIM technology”, International Journal of Civil and Structural Engineering Research ISSN 2348-7607 (Online), Vol. 9, Issue 1, pp: (10-20), Month: April 2021 - September 2021.

- Abdelalim, A.M. and Said, S.O.M., 2021.” Theoretical Understanding of Indoor/Outdoor Tracking Systems in the Construction Industry”, International Journal of Civil and Structural Engineering Research ISSN 2348-7607 (Online) Vol. 9, Issue 1, pp: (30-36), Month: April 2021.

- Abdelalim, A.M. , 2018, “IRVQM, Integrated Approach for Risk, Value and Quality Management in Construction Projects; Methodology and Practice”, the 2nd International Conference of Sustainable Construction and Project Management, Sustainable Infrastructure and Transportation for Future cities, ICSCPM-18, 16-18 December, 2018, Aswan, Egypt.

- Abdelalim, A. M. (2019). Risks Affecting the Delivery of Construction Projects in Egypt: Identifying, Assessing and Response. In Project Management and BIM for Sustainable Modern Cities: Proceedings of the 2nd GeoMEast International Congress and Exhibition on Sustainable Civil Infrastructures, Egypt 2018–The Official International Congress of the Soil-Structure Interaction Group in Egypt (SSIGE) (pp. 125-154). Springer International publishing. [CrossRef]

- Abdelalim, A.M. , El Nawawy, O.A. and Bassiony, M.S., 2016. ’Decision Supporting System for Risk Assessment in Construction Projects: AHP-Simulation Based. IPASJ International Journal of Computer Science (IIJCS), 4(5), pp.22-36. [CrossRef]

- Abdelalim, A.M. and Abo. Elsaud, Y., 2019. Integrating BIM-based simulation technique for sustainable building design. In Project Management and BIM for Sustainable Modern Cities: Proceedings of the 2nd GeoMEast International Congress and Exhibition on Sustainable Civil Infrastructures, Egypt 2018–The Official International Congress of the Soil-Structure Interaction Group in Egypt (SSIGE) (pp. 209-238). Springer International Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Shawky, K. A., Abdelalim, A. M., & Sherif, A. G. (2024). Standardization of BIM Execution Plans (BEP’s) for Mega Construction Projects: A Comparative and Scientometric Study. [CrossRef]

- Hassanen, M. A. H., & Abdelalim, A. M. (2022). Risk Identification and Assessment of Mega Industrial Projects in Egypt. International Journal of Management and Commerce Innovation (IJMCI), 10(1), 187-199. [CrossRef]

- Hassanen, M. A. H. , & Abdelalim, A. M., A Proposed Approach for a Balanced Construction Contract for Mega Industrial Projects in Egypt, 2022, International Journal of Management and Commerce Innovations ISSN 2348-7585, Vol.10, Issue.1, pp: 217-229. [CrossRef]

- Amin Sherif, Abdelalim, A.M., 2023, “Delay Analysis Techniques and Claim Assessment in Construction Projects”, International Journal of Engineering, Management and Humanities (IJEMH), Vol.10, Issue.2, 316-325. [CrossRef]

- Medhat, W., Abdelkhalek, H., & Abdelalim, A. M. (2023). A Comparative Study of the International Construction Contract (FIDIC Red Book 1999) and the Domestic Contract in Egypt (the Administrative Law 182 for the year 2018). [CrossRef]

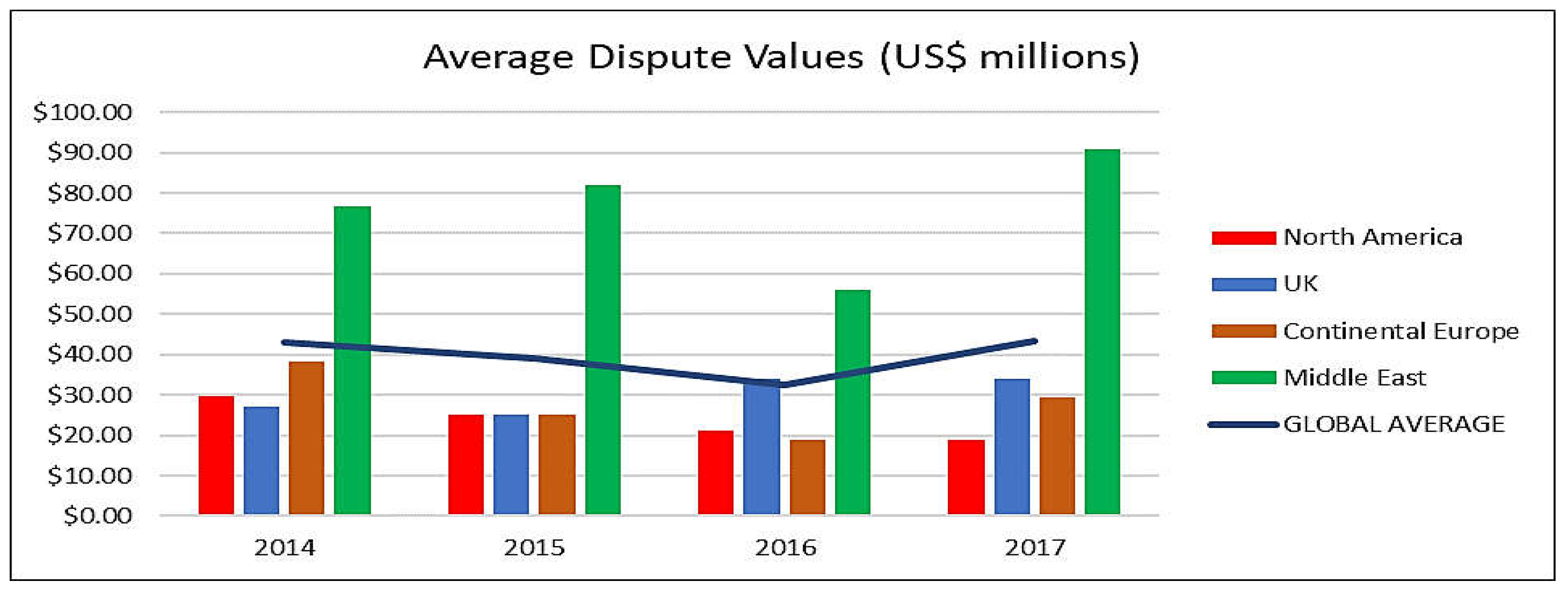

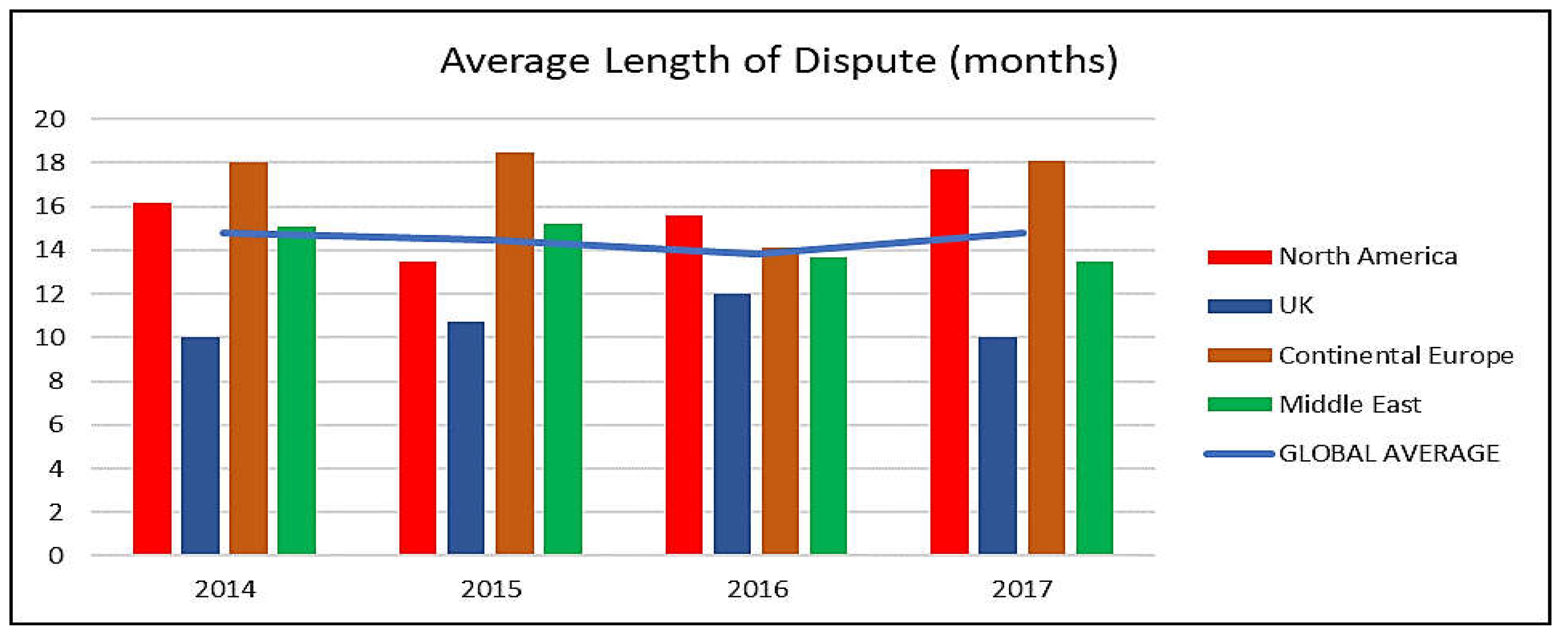

| Region | Average Dispute Value (US$ millions) | Average Length of Dispute (Months) | ||||||

| 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | |

| North America | 29.6 | 25 | 21 | 19 | 16.2 | 13.5 | 15.6 | 17.7 |

| UK | 27 | 25 | 34 | 34 | 10 | 10.7 | 12 | 10 |

| Continental Europe | 38.3 | 25 | 19 | 29.5 | 18 | 18.5 | 14.1 | 18.1 |

| Middle East | 76.7 | 82 | 56 | 91 | 15.1 | 15.2 | 13.7 | 13.5 |

| GLOBAL AVERAGE | 42.9 | 39.25 | 32.5 | 43.375 | 14.825 | 14.475 | 13.85 | 14.825 |

| Rank | Method and Advice |

|---|---|

| 1 | Studying and reviewing all contract documents; BOQ, drawing, specification, general and special conditions to make sure no inconsistent before tendering |

| 2 | Good planning and enough studying for all project needed along project cycle |

| 3 | Preparing complete drawing and its detail professionally, and no omission or ambiguity |

| 4 | Awarding the bid to qualified contractor" financially and technically" for the specified project, not the lowest price. |

| 5 | Overcome ambiguity in contract documents, balance contract, and describing items in BOQ precisely |

| 6 | Quantities in contract must be precisely and cover all project works. |

| 7 | Possession supervision team enough experience weather technically or in management of contract in construction projects. And ability for design making in a proper time. |

| 8 | Determining the specification for the used material according to codes and proper tests, and approval alternatives equal in specification in local market. |

| 9 | Submitting a concrete time schedule for the execution of the project and making updating and documenting events on schedule parallel with issuing payments. |

| 10 | Adequate coordination between all the parties involved in construction projects in and avoiding stack holder interference. |

| Problems in Identification of Claims | Contractors Ranking | Consultants Ranking |

|---|---|---|

| Lack of awareness of site staff to notice a claim. | 1 | 2 |

| Insufficient contract knowledge by site staff. | 2 | 4 |

| Insufficient time due to high workload. | 3 | 5 |

| Insufficient skilled personnel for detecting a claim. | 4 | 1 |

| Difficulties in detecting any problems during the work due to high work-load. | 5 | 6 |

| Poor communication between site and head office. | 6 | 3 |

| Inaccessibility of documents used for identifying a claim. | 7 | 8 |

| Ambiguous line of responsibility as to who should detect a claim. | 8 | 7 |

| Ambiguous procedures in claim identification. | 9 | 9 |

| Problems in Identification of Claims | Contractors Ranking | Consultants Ranking |

|---|---|---|

| Verbal instruction by owner. | 1 | 2 |

| Some information/instruction is not kept in writing. | 2 | 1 |

| Ineffective record-keeping system. | 3 | 3 |

| Inaccurate recorded information. | 4 | 4 |

| Inaccessibility of documents when needed. | 5 | 6 |

| Overdue in retrieving the needed document. | 6 | 5 |

| No standard form used to record the data during construction. | 7 | 7 |

| No computerized documentation system. | 8 | 8 |

| High cost associated with retrieving required information. | 9 | 9 |

| Problems in Quantification of Claims | Contractors Ranking | Consultants Ranking |

|---|---|---|

| Unavailability of records used to analyze and estimate the potential recovery. | 1 | 1 |

| Insufficient time to thoroughly examine claim due to high workload. | 2 | 3 |

| Poor communication to gather the required information to analyze a claim. | 3 | 2 |

| Lack of legal/contract to establish the base on which the claim stands. | 4 | 4 |

| Ambiguous procedures for claim examination. | 5 | 6 |

| No standard formula used to evaluate the impacts and calculating damages. | 6 | 8 |

| Ambiguous responsibility as who should evaluate the amount of recovery. | 7 | 5 |

| Unrealistic formula used to calculate damages. | 8 | 7 |

| Insufficient computerized machines to facilitate the calculation. | 9 | 9 |

| Problems in Presentation of Claims | Contractors Ranking | Consultants Ranking |

|---|---|---|

| Inaccessibility of relevant documents to submit along with the claim | 1 | 1 |

| Insufficient skilled staff in preparing a claim submission. | 2 | 2 |

| Poor communication in presenting a claim. | 3 | 4 |

| Insufficient time to thoroughly prepare claims due to high workload. | 4 | 3 |

| Ambiguous responsibility to the person that prepare the full report of claim presentation. | 5 | 6 |

| No standard format of a claim submission. | 6 | 7 |

| Ambiguous procedures in preparation of claim presentation. | 7 | 5 |

| Problems in Negotation of Claims | Contractors Ranking | Consultants Ranking |

|---|---|---|

| Disagreement arising during negotiation | 1 | 1 |

| Unsatisfactory evidence to convince other parties. | 2 | 2 |

| Poor negotiation skills. | 3 | 3 |

| Adversarial relationship with other parties. | 4 | 4 |

| Inadequate time due to high workload. | 5 | 5 |

| Difficult to settle without any litigation or Arbitration. | 6 | 6 |

| Code | Attributes |

|---|---|

| X | Claim Management Planning |

| XR | Reasons of Claims |

| XR1 | Project execution time is short with lack of (site investigation, tender and contract documents). |

| XR2 | Acceptance of imprecise tender offers with lack of (clarifications, negotiations and recording of changes). |

| XR3 | Changes arising from local authority sources. |

| XR4 | Lack of experiences for designers, contract administrators and contractors. |

| XR5 | Sudden swings in economic and market conditions. |

| XR6 | Unforeseen site conditions. |

| XR7 | Frequent changes and/or variations by the client. |

| XR8 | Poor communications between project participants |

| XR9 | Procurement problems |

| XR10 | Unbalanced risk allocation. |

| XR11 | Unrealistic planning and specifications |

| XR12 | Suspensions issues |

| XR13 | Unfavorable weather conditions |

| XR14 | Indecisive management. |

| XR15 | Separate contracts (coordination problems). |

| XR16 | Untimely approvals. |

| XR17 | Poor briefing. |

| XR18 | The owner changes his mind during construction |

| XR19 | Poor financial arrangement, leading to late payments |

| XR20 | Owner's reluctance to each decision that might be criticized |

| XR21 | Using an unstudied design and elements for the first time |

| XR22 | Misinterpretation of construction documents |

| XR23 | Lack of procedure to correct errors between owner, designer and contractor |

| XR24 | Conflict management |

| XR25 | Contractor inability for site supervision and management |

| XR26 | Engineer's satisfaction clauses |

| XR27 | Design errors, omissions and contradictions in documents |

| XR28 | Payment delays on changing orders |

| XR29 | Price determination on change order. |

| XR30 | Currency fluctuations |

| XR31 | Lack of payment certification guarantees and bonds and cash flow |

| XR32 | Unclear employer applications and responsibilities of all the other parties |

| XR33 | Constructive acceleration |

| XR34 | Non-compliance with professional ethics in construction |

| XM | Claims prevention / Mitigation |

| XM1 | Precise scope, risk allocated and well executed contract availability |

| XM2 | Establishment of good project plan |

| XM3 | Good communication with all stakeholders |

| XM4 | Identifying and managing the factors that may have negative impact on the project. |

| XM5 | Early recognition of potential problems |

| XM6 | Creating a collaborative work environment (project partnering). |

| XM7 | Clear and balanced contract terms and conditions regarding changes, claims and disputes resolution. |

| XM8 | Conducting an integrated change control |

| XM9 | Change management plan establishment |

| XM10 | Continual updating of project schedule |

| XM11 | Conducting studies for constructability and maintenance review. |

| XM12 | Clear procedure for (RFI) Request for Information. |

| XM13 | Commitment to periodic progress reports |

| XM14 | Prequalification process |

| XM15 | Good project documentation. |

| XM16 | Creating Specific Claim Litigation Prevention Techniques. |

| XM17 | Good planning of the contract and relying on a culture of win-win for all parties. |

| Y | Problems in claim process (Monitoring and Controlling). |

| YJ | Claims Identification. |

| YJ1 | Lack of methodology for claims management. |

| YJ2 | Poor communication between site and head office. |

| YJ3 | Lack of documentation |

| YJ4 | Lack of Clarity of contract provisions relating to change order, changed conditions, schedules preparation and submission, and appropriate notice requirements. |

| YJ5 | Lack of clarity of the scope. |

| YJ6 | No clear procedure for managing claim. |

| YJ7 | Claim management section /or team is not clearly assigned. |

| YJ8 | Lack of awareness of site staff to notice a claim. |

| YJ9 | Inadequate time due to high workload. |

| YJ10 | The impact of the claims on project schedule not documented. |

| YJ11 | Lack of advice from experts to see if the claim is valid or not. |

| YJ12 | Lack of preparing and submitting a complete statement of the claim in accordance with contract provision. |

| YJ13 | Inadequate care about rising claims. |

| YD | Claims Documentation |

| YD1 | Verbal instruction by owner has not documented. |

| YD2 | Ineffective record-keeping system. |

| YD3 | Inaccessibility to documents when needed. |

| YD4 | Overdue in retrieving the needed document |

| YD5 | No standard form used to record the data during construction |

| YD6 | High cost associated with retrieving required information. |

| YQ | Claims Quantification |

| YQ1 | Poor study and non-verification of claims |

| YQ2 | Lack of documentation |

| YQ3 | Ambiguous procedures in notice preparation |

| YQ4 | Lack of clarifications requests about contract documents discrepancy |

| YQ5 | Insufficient time to thoroughly prepare the notice due to high workload |

| YQ6 | Poor schedule analysis to demonstrate the claim impact |

| YQ7 | Prescribed time in the contract is too short |

| YQ8 | Quantification problems |

| YQ9 | Poor communication/instruction to proceed with submitting the notice. |

| YQ10 | Unclear responsibility for preparing the claim notice |

| YQ11 | Errors in quantities measurement for claimed work. |

| YQ12 | Errors in cost estimation for claimed work |

| YQ13 | Ignorance of claims rules and contract law |

| YQ14 | Presence of concurrent claims |

| YP | Claims Presentation |

| YP1 | Inaccessibility for relevant claim documents |

| YP2 | Insufficient skilled staff in preparing a claim submission |

| YP3 | Poor communication in presenting a claim |

| YP4 | Insufficient time to prepare claims |

| YP5 | No assignment for a responsible person for preparing the full report of claim presentation |

| YP6 | No standard format of a claim submission |

| YP7 | Ambiguous procedures in preparation of claim presentation |

| YP8 | Submissions of incomplete documents |

| YN | Claims Negotiation |

| YN1 | Disagreement arising during negotiation. |

| YN2 | Unsatisfactory evidence to convince other parties |

| YN3 | Poor negotiation skills |

| YN4 | Adversarial relationship with other parties |

| YN5 | Inadequate time due to high workload. |

| YN6 | The difficulty of settling the claim without any litigation or arbitration. |

| YR | Claims Resolution |

| YR1 | Statement of claims, contract and Claims quantifications are not taken into consideration |

| YR2 | Expert knowledge and fully documented certified claims are not taken into consideration |

| YR3 | Lack of negotiating skill |

| YR4 | Lack of specification litigation prevention techniques (independent natural) |

| YR5 | Non-availability of estimated cost of claim |

| YR6 | Lack of expert report or Claim assessment |

| YR7 | Balanced contracts such as FIDIC and ECC contracts are not used. |

| YR8 | The terms of contract don't focus on good management and effective risk distribution |

| YR9 | Contract terms are inflexible for using a wide range of contracting strategies. |

| YR10 | The roles and responsibilities of contracting parties are not identified |

| No. | Filed | Cronbach's Alpha Value | level |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | For the entire questionnaire in terms of (impact). | 0.986 | High internal Consistency |

| 2 | for the entire questionnaire in terms of (probability) | 0.980 | High internal Consistency |

| 3 | for the entire questionnaire in terms of both (impact and probability) | 0.984 | High internal Consistency |

| Importance | Very Low | Low | Moderate | High | Very High |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| From | Up to 20% | 20% | 40% | 60% | 80% |

| To | 40% | 60% | 80% | 100% |

| Importance | Very High | High | Moderate | Low | Very Low | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| From | Up to 20% | 60% | 40% | 20% | 80% | |

| To | 80% | 60% | 40% | 100% | ||

| FAII Value | From | 24.86 | 45.46 | 38.59 | 31.78 | 52.32 |

| To | 31.77 | 52.31 | 45.45 | 38.58 | 59.17 | |

| Code | RII | RII Rank | RII Rank/ Group | FI | FI Rank | FI Rank / Group | FAII | FAII Rank | FAII Rank / Group | Factor Levels |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| YN3 | 0.77 | 21.00 | 1 | 76.92 | 46.00 | 43.80 | 59.17 | 1 | 1 | very high |

| YN4 | 0.76 | 26.00 | 2 | 76.15 | 31.00 | 29.50 | 57.99 | 2 | 2 | very high |

| YR7 | 0.76 | 30.00 | 1 | 75.96 | 38.00 | 36.20 | 57.70 | 3 | 1 | very high |

| YN1 | 0.75 | 34.00 | 3 | 75.38 | 41.00 | 39.00 | 56.83 | 4 | 3 | very high |

| YN2 | 0.75 | 37.00 | 4 | 75.19 | 41.00 | 39.00 | 56.54 | 5 | 4 | very high |

| YR1 | 0.75 | 44.00 | 2 | 74.62 | 44.00 | 41.90 | 55.67 | 6 | 2 | very high |

| YR3 | 0.74 | 46.00 | 3 | 74.42 | 43.00 | 41.00 | 55.39 | 7 | 3 | very high |

| YR4 | 0.74 | 46.00 | 3 | 74.42 | 34.00 | 32.40 | 55.39 | 7 | 3 | very high |

| XM3 | 0.80 | 5.00 | 4 | 67.88 | 24.00 | 35.20 | 54.57 | 9 | 1 | very high |

| YJ10 | 0.78 | 16.00 | 4 | 70.00 | 36.00 | 33.30 | 54.38 | 10 | 1 | very high |

| YR6 | 0.74 | 56.00 | 5 | 73.65 | 42.00 | 40.00 | 54.25 | 11 | 5 | very high |

| YR10 | 0.74 | 57.00 | 6 | 73.46 | 44.00 | 41.90 | 53.97 | 12 | 6 | very high |

| YR2 | 0.73 | 61.00 | 7 | 73.27 | 29.00 | 27.60 | 53.68 | 13 | 7 | very high |

| YD1 | 0.79 | 12.00 | 1 | 68.08 | 37.00 | 32.40 | 53.41 | 14 | 1 | very high |

| YJ8 | 0.76 | 32.00 | 7 | 70.19 | 38.00 | 38.10 | 53.05 | 15 | 2 | very high |

| YR8 | 0.73 | 65.00 | 8 | 72.69 | 41.00 | 39.00 | 52.84 | 16 | 8 | very high |

| XM7 | 0.81 | 3.00 | 2 | 64.81 | 24.00 | 29.50 | 52.34 | 17 | 2 | very high |

| XM2 | 0.81 | 3.00 | 2 | 64.62 | 29.00 | 40.00 | 52.19 | 18 | 3 | High |

| XR19 | 0.82 | 2.00 | 1 | 63.85 | 22.00 | 31.40 | 52.06 | 19 | 1 | High |

| YQ13 | 0.78 | 18.00 | 1 | 67.12 | 33.00 | 29.50 | 52.01 | 20 | 1 | High |

| YR5 | 0.72 | 68.00 | 9 | 72.12 | 34.00 | 32.40 | 52.01 | 21 | 9 | High |

| YP2 | 0.77 | 21.00 | 1 | 67.50 | 36.00 | 42.90 | 51.92 | 22 | 1 | High |

| XR31 | 0.79 | 11.00 | 2 | 65.77 | 35.00 | 41.90 | 51.86 | 23 | 2 | High |

| YR9 | 0.72 | 71.00 | 10 | 71.92 | 42.00 | 40.00 | 51.73 | 24 | 10 | High |

| YJ3 | 0.80 | 7.00 | 1 | 64.62 | 29.00 | 37.10 | 51.57 | 25 | 3 | High |

| XM1 | 0.79 | 10.00 | 7 | 65.19 | 32.00 | 37.10 | 51.53 | 26 | 4 | High |

| XM5 | 0.82 | 1.00 | 1 | 62.88 | 29.00 | 41.90 | 51.40 | 27 | 5 | High |

| XM10 | 0.77 | 20.00 | 9 | 66.15 | 41.00 | 32.40 | 51.01 | 28 | 6 | High |

| XM16 | 0.80 | 6.00 | 5 | 63.65 | 29.00 | 29.50 | 50.92 | 29 | 7 | High |

| XM15 | 0.78 | 16.00 | 8 | 65.38 | 26.00 | 38.10 | 50.80 | 30 | 8 | High |

| YP7 | 0.71 | 76.00 | 6 | 71.15 | 36.00 | 34.30 | 50.63 | 31 | 2 | High |

| YJ4 | 0.79 | 9.00 | 2 | 63.85 | 24.00 | 41.00 | 50.59 | 32 | 4 | High |

| XR28 | 0.75 | 41.00 | 8 | 67.31 | 34.00 | 40.00 | 50.35 | 33 | 3 | High |

| XR18 | 0.74 | 54.00 | 11 | 68.08 | 30.00 | 41.00 | 50.27 | 34 | 4 | High |

| YJ7 | 0.75 | 41.00 | 9 | 66.73 | 32.00 | 36.20 | 49.92 | 35 | 5 | High |

| YJ1 | 0.78 | 18.00 | 5 | 64.23 | 38.00 | 41.90 | 49.78 | 36 | 6 | High |

| YD2 | 0.76 | 26.00 | 2 | 64.81 | 26.00 | 31.40 | 49.35 | 37 | 2 | High |

| XR1 | 0.79 | 12.00 | 3 | 62.69 | 20.00 | 47.60 | 49.19 | 38 | 5 | High |

| XR2 | 0.79 | 12.00 | 3 | 62.69 | 28.00 | 44.80 | 49.19 | 38 | 5 | High |

| YJ11 | 0.74 | 57.00 | 13 | 66.92 | 34.00 | 39.00 | 49.16 | 41 | 7 | High |

| YP8 | 0.75 | 37.00 | 3 | 65.38 | 31.00 | 44.80 | 49.16 | 40 | 3 | High |

| YJ9 | 0.74 | 46.00 | 10 | 65.96 | 33.00 | 40.00 | 49.09 | 42 | 8 | High |

| YJ12 | 0.74 | 52.00 | 12 | 65.96 | 30.00 | 41.00 | 48.84 | 43 | 9 | High |

| YQ6 | 0.74 | 52.00 | 5 | 65.96 | 32.00 | 40.00 | 48.84 | 43 | 2 | High |

| YN6 | 0.69 | 92.00 | 5 | 69.42 | 29.00 | 27.60 | 48.20 | 45 | 5 | High |

| XM4 | 0.75 | 37.00 | 12 | 63.65 | 27.00 | 39.00 | 47.86 | 46 | 9 | High |

| XM6 | 0.77 | 24.00 | 10 | 62.31 | 26.00 | 48.60 | 47.69 | 47 | 10 | High |

| YJ13 | 0.76 | 32.00 | 7 | 62.69 | 24.00 | 32.40 | 47.38 | 48 | 10 | High |

| YJ2 | 0.76 | 30.00 | 6 | 62.31 | 28.00 | 35.20 | 47.33 | 49 | 11 | High |

| XR7 | 0.72 | 68.00 | 16 | 65.58 | 35.00 | 42.90 | 47.29 | 50 | 7 | High |

| YQ1 | 0.74 | 50.00 | 4 | 63.65 | 34.00 | 43.80 | 47.25 | 51 | 3 | High |

| YQ2 | 0.75 | 40.00 | 2 | 62.88 | 23.00 | 44.80 | 47.16 | 52 | 4 | High |

| XM17 | 0.79 | 8.00 | 6 | 59.23 | 29.00 | 35.20 | 47.04 | 53 | 11 | High |

| YJ6 | 0.74 | 46.00 | 10 | 63.08 | 24.00 | 35.20 | 46.94 | 54 | 12 | High |

| YD3 | 0.76 | 26.00 | 2 | 61.54 | 26.00 | 43.80 | 46.86 | 55 | 3 | High |

| XR5 | 0.77 | 23.00 | 5 | 60.58 | 21.00 | 31.40 | 46.48 | 56 | 8 | High |

| XR27 | 0.76 | 25.00 | 6 | 60.77 | 28.00 | 43.80 | 46.39 | 57 | 9 | High |

| XR4 | 0.75 | 41.00 | 8 | 61.92 | 29.00 | 41.00 | 46.32 | 58 | 10 | High |

| XR8 | 0.73 | 65.00 | 15 | 63.08 | 28.00 | 41.00 | 45.85 | 59 | 11 | High |

| XR23 | 0.73 | 62.00 | 13 | 61.92 | 23.00 | 36.20 | 45.25 | 60 | 12 | Moderate |

| XM13 | 0.72 | 73.00 | 14 | 63.08 | 33.00 | 37.10 | 45.25 | 61 | 12 | Moderate |

| YP1 | 0.75 | 34.00 | 2 | 60.00 | 24.00 | 37.10 | 45.23 | 62 | 4 | Moderate |

| YQ12 | 0.75 | 44.00 | 3 | 60.58 | 25.00 | 42.90 | 45.20 | 63 | 5 | Moderate |

| YD4 | 0.73 | 67.00 | 4 | 62.12 | 25.00 | 39.00 | 45.03 | 64 | 4 | Moderate |

| YP3 | 0.73 | 64.00 | 5 | 61.73 | 18.00 | 40.00 | 44.99 | 65 | 5 | Moderate |

| YN5 | 0.67 | 103.00 | 6 | 66.92 | 36.00 | 34.30 | 44.79 | 66 | 6 | Moderate |

| YJ5 | 0.78 | 15.00 | 3 | 57.50 | 17.00 | 38.10 | 44.78 | 67 | 13 | Moderate |

| XR20 | 0.74 | 50.00 | 10 | 60.19 | 25.00 | 50.50 | 44.68 | 68 | 13 | Moderate |

| XM9 | 0.75 | 34.00 | 11 | 59.04 | 19.00 | 29.50 | 44.51 | 69 | 13 | Moderate |

| YP5 | 0.74 | 57.00 | 4 | 60.19 | 30.00 | 34.30 | 44.22 | 70 | 6 | Moderate |

| YQ10 | 0.71 | 76.00 | 6 | 61.92 | 30.00 | 41.90 | 44.06 | 71 | 6 | Moderate |

| YD5 | 0.70 | 84.00 | 5 | 62.50 | 28.00 | 32.40 | 43.99 | 72 | 5 | Moderate |

| XR9 | 0.70 | 87.00 | 26 | 62.50 | 34.00 | 40.00 | 43.51 | 73 | 14 | Moderate |

| XR33 | 0.71 | 82.00 | 23 | 61.35 | 30.00 | 32.40 | 43.30 | 74 | 15 | Moderate |

| XR15 | 0.70 | 87.00 | 26 | 61.73 | 26.00 | 35.20 | 42.97 | 75 | 16 | Moderate |

| XR29 | 0.70 | 85.00 | 24 | 61.35 | 22.00 | 35.20 | 42.94 | 76 | 17 | Moderate |

| XR25 | 0.76 | 26.00 | 7 | 55.96 | 20.00 | 34.30 | 42.62 | 78 | 18 | Moderate |

| YQ4 | 0.71 | 82.00 | 9 | 60.38 | 26.00 | 42.90 | 42.62 | 77 | 7 | Moderate |

| XR12 | 0.74 | 54.00 | 11 | 57.69 | 24.00 | 30.50 | 42.60 | 79 | 19 | Moderate |

| XM8 | 0.74 | 57.00 | 13 | 57.88 | 21.00 | 36.20 | 42.52 | 80 | 14 | Moderate |

| YP6 | 0.68 | 98.00 | 8 | 62.50 | 29.00 | 31.40 | 42.43 | 81 | 7 | Moderate |

| XR22 | 0.72 | 73.00 | 19 | 58.27 | 24.00 | 31.40 | 41.80 | 82 | 20 | Moderate |

| YQ11 | 0.71 | 76.00 | 6 | 57.88 | 24.00 | 38.10 | 41.19 | 83 | 8 | Moderate |

| XR16 | 0.68 | 97.00 | 30 | 60.38 | 28.00 | 40.00 | 41.11 | 84 | 21 | Moderate |

| XR10 | 0.69 | 96.00 | 29 | 59.23 | 19.00 | 35.20 | 40.89 | 85 | 22 | Moderate |

| YQ5 | 0.68 | 98.00 | 11 | 60.19 | 29.00 | 38.10 | 40.86 | 86 | 9 | Moderate |

| XR24 | 0.70 | 86.00 | 25 | 58.46 | 18.00 | 38.10 | 40.81 | 87 | 23 | Moderate |

| YQ3 | 0.70 | 87.00 | 10 | 58.46 | 20.00 | 39.00 | 40.70 | 88 | 10 | Moderate |

| XR32 | 0.69 | 94.00 | 28 | 58.46 | 18.00 | 30.50 | 40.47 | 89 | 24 | Moderate |

| XM12 | 0.70 | 87.00 | 15 | 58.08 | 28.00 | 30.50 | 40.43 | 90 | 15 | Moderate |

| XR26 | 0.72 | 68.00 | 16 | 55.96 | 17.00 | 31.40 | 40.36 | 91 | 25 | Moderate |

| YQ7 | 0.71 | 80.00 | 8 | 56.92 | 21.00 | 36.20 | 40.28 | 92 | 11 | Moderate |

| YQ14 | 0.67 | 101.00 | 12 | 59.62 | 27.00 | 35.20 | 40.01 | 93 | 12 | Moderate |

| XR3 | 0.68 | 100.00 | 31 | 58.08 | 23.00 | 28.60 | 39.31 | 94 | 26 | Moderate |

| YQ9 | 0.67 | 101.00 | 12 | 58.46 | 24.00 | 34.30 | 39.24 | 95 | 13 | Moderate |

| YP4 | 0.70 | 87.00 | 7 | 56.35 | 14.00 | 39.00 | 39.23 | 96 | 8 | Moderate |

| XR14 | 0.72 | 73.00 | 19 | 54.23 | 21.00 | 32.40 | 38.90 | 97 | 27 | Moderate |

| XR21 | 0.73 | 62.00 | 13 | 52.88 | 23.00 | 35.20 | 38.65 | 98 | 28 | Moderate |

| XM14 | 0.69 | 94.00 | 17 | 55.58 | 18.00 | 36.20 | 38.48 | 99 | 16 | Low |

| XR11 | 0.71 | 80.00 | 22 | 54.04 | 17.00 | 31.40 | 38.24 | 100 | 29 | Low |

| XR34 | 0.72 | 71.00 | 18 | 53.08 | 19.00 | 39.00 | 38.17 | 101 | 30 | Low |

| XM11 | 0.69 | 92.00 | 16 | 54.62 | 19.00 | 30.50 | 37.92 | 102 | 17 | Low |

| YQ8 | 0.66 | 104.00 | 14 | 54.23 | 18.00 | 41.00 | 35.98 | 103 | 14 | Low |

| YD6 | 0.64 | 106.00 | 6 | 55.00 | 20.00 | 30.50 | 35.43 | 104 | 6 | Low |

| XR30 | 0.71 | 76.00 | 21 | 49.62 | 16.00 | 28.60 | 35.30 | 105 | 31 | Low |

| XR6 | 0.64 | 107.00 | 33 | 53.46 | 11.00 | 24.80 | 34.03 | 106 | 32 | Low |

| XR17 | 0.66 | 105.00 | 32 | 50.58 | 14.00 | 37.10 | 33.36 | 107 | 33 | Low |

| XR13 | 0.56 | 108.00 | 34 | 44.42 | 4.00 | 19.00 | 24.86 | 108 | 34 | Very Low |

| Pearson correlation value of factors and their groups. | R | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| XM3 | Good communication with all stakeholders | Impact | 0.837** | 0.000 |

| Probability | 0.748** | 0.000 | ||

| XM7 | Clear and balanced contract terms and conditions regarding changes, claims and disputes resolution | Impact | 0.827** | 0.000 |

| Probability | 0.797** | 0.000 | ||

| YJ8 | Lack of awareness of site staff to notice a claim | Impact | 0.828** | 0.000 |

| Probability | 0.792** | 0.000 | ||

| YJ10 | The impact of the claims on project schedule not documented. | Impact | 0.840** | 0.000 |

| Probability | 0.750** | 0.000 | ||

| YD1 | Verbal instruction by owner has not documented. | Impact | 0.829** | 0.000 |

| Probability | 0.788** | 0.000 | ||

| YN1 | Disagreement arising during negotiation. | Impact | 0.829** | 0.000 |

| Probability | 0.703** | 0.000 | ||

| YN2 | Unsatisfactory evidence to convince other parties. | Impact | 0.805** | 0.000 |

| Probability | 0.757** | 0.000 | ||

| YN3 | Poor negotiation skills | Impact | 0.738** | 0.000 |

| Probability | 0.816** | 0.000 | ||

| YN4 | Adversarial relationship with other parties | Impact | 0.792** | 0.000 |

| Probability | 0.780** | 0.000 | ||

| YR1 | Statement of claims, contract and Claims quantifications are not taken into consideration | Impact | 0.685** | 0.000 |

| Probability | 0.702** | 0.000 | ||

| YR2 | Expert knowledge and fully documented certified claims are not taken into consideration | Impact | 0.748** | 0.000 |

| Probability | 0.709** | 0.000 | ||

| YR3 | Lack of negotiating skill | Impact | 0.797** | 0.000 |

| Probability | 0.742** | 0.000 | ||

| YR4 | Lack of specification litigation prevention techniques (independent natural). | Impact | 0.819** | 0.000 |

| Probability | 0.725** | 0.000 | ||

| YR6 | Lack of expert report or Claim assessment | Impact | 0.863** | 0.000 |

| Probability | 0.843** | 0.000 | ||

| YR7 | Balanced contracts such as FIDIC and ECC contracts are not used. | Impact | 0.800** | 0.000 |

| Probability | 0.749** | 0.000 | ||

| YR8 | The terms of contract don't focus on good management and effective risk distribution | Impact | 0.805** | 0.000 |

| Probability | 0.761** | 0.000 | ||

| YR10 | The roles and responsibilities of contracting parties are not identified. | Impact | 0.710** | 0.000 |

| Probability | 0.704** | 0.000 | ||

| Code | RII | RII Rank | RII Rank by Group | FI | FI Rank | FI Rank by Group | FAII | FAII Rank | FAII Rank by Group | Significant level |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| XM | Claims prevention / Mitigation | |||||||||

| XM3 | 0.804 | 5 | 4 | 67.88 | 24 | 35.2 | 54.57 | 9 | 1 | very high |

| XM7 | 0.808 | 3 | 2 | 64.81 | 24 | 29.5 | 52.34 | 17 | 2 | very high |

| XM2 | 0.808 | 3 | 2 | 64.62 | 29 | 40 | 52.19 | 18 | 3 | High |

| XM1 | 0.79 | 10 | 7 | 65.19 | 32 | 37.1 | 51.53 | 26 | 4 | High |

| XM5 | 0.817 | 1 | 1 | 62.88 | 29 | 41.9 | 51.4 | 27 | 5 | High |

| XM10 | 0.771 | 20 | 9 | 66.15 | 41 | 32.4 | 51.01 | 28 | 6 | High |

| XM16 | 0.8 | 6 | 5 | 63.65 | 29 | 29.5 | 50.92 | 29 | 7 | High |

| XM15 | 0.777 | 16 | 8 | 65.38 | 26 | 38.1 | 50.8 | 30 | 8 | High |

| XM4 | 0.752 | 37 | 12 | 63.65 | 27 | 39 | 47.86 | 46 | 9 | High |

| XM6 | 0.765 | 24 | 10 | 62.31 | 26 | 48.6 | 47.69 | 47 | 10 | High |

| XM17 | 0.794 | 8 | 6 | 59.23 | 29 | 35.2 | 47.04 | 53 | 11 | High |

| Code | RII | RII Rank | RII Rank by Group | FI | FI Rank | FI Rank by Group | FAII | FAII Rank | FAII Rank by Group | Significant level |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| YJ | Claims Identification and Initial Justifications | |||||||||

| YJ10 | 0.777 | 16 | 4 | 70 | 36 | 33.3 | 54.38 | 10 | 1 | very high |

| YJ8 | 0.756 | 32 | 7 | 70.19 | 38 | 38.1 | 53.05 | 15 | 2 | very high |

| YJ3 | 0.798 | 7 | 1 | 64.62 | 29 | 37.1 | 51.57 | 25 | 3 | High |

| YJ4 | 0.792 | 9 | 2 | 63.85 | 24 | 41 | 50.59 | 32 | 4 | High |

| YJ7 | 0.748 | 41 | 9 | 66.73 | 32 | 36.2 | 49.92 | 35 | 5 | High |

| YJ1 | 0.775 | 18 | 5 | 64.23 | 38 | 41.9 | 49.78 | 36 | 6 | High |

| YJ11 | 0.735 | 57 | 13 | 66.92 | 34 | 39 | 49.16 | 41 | 7 | High |

| YJ9 | 0.744 | 46 | 10 | 65.96 | 33 | 40 | 49.09 | 42 | 8 | High |

| YJ12 | 0.74 | 52 | 12 | 65.96 | 30 | 41 | 48.84 | 43 | 9 | High |

| YJ13 | 0.756 | 32 | 7 | 62.69 | 24 | 32.4 | 47.38 | 48 | 10 | High |

| YJ2 | 0.76 | 30 | 6 | 62.31 | 28 | 35.2 | 47.33 | 49 | 11 | High |

| YJ6 | 0.744 | 46 | 10 | 63.08 | 24 | 35.2 | 46.94 | 54 | 12 | High |

| Code | RII | RII Rank | RII Rank by Group | FI | FI Rank | FI Rank by Group | FAII | FAII Rank | FAII Rank by Group | Significant level |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| YD | Claims Documentation | |||||||||

| YD1 | 0.785 | 12 | 1 | 68.08 | 37 | 32.4 | 53.41 | 14 | 1 | very high |

| YD2 | 0.762 | 26 | 2 | 64.81 | 26 | 31.4 | 49.35 | 37 | 2 | High |

| YD3 | 0.762 | 26 | 2 | 61.54 | 26 | 43.8 | 46.86 | 55 | 3 | High |

| Code | RII | RII Rank | RII Rank by Group | FI | FI Rank | FI Rank by Group | FAII | FAII Rank | FAII Rank by Group | Significant level |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| YQ | Claims Quantification | |||||||||

| YQ13 | 0.775 | 18 | 1 | 67.12 | 33 | 29.5 | 52.01 | 20 | 1 | High |

| YQ6 | 0.74 | 52 | 5 | 65.96 | 32 | 40 | 48.84 | 43 | 2 | High |

| YQ1 | 0.742 | 50 | 4 | 63.65 | 34 | 43.8 | 47.25 | 51 | 3 | High |

| YQ2 | 0.75 | 40 | 2 | 62.88 | 23 | 44.8 | 47.16 | 52 | 4 | High |

| Code | RII | RII Rank | RII Rank by Group | FI | FI Rank | FI Rank by Group | FAII | FAII Rank | FAII Rank by Group | Significant Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| YP | Claims Presentation | |||||||||

| YP2 | 0.769 | 21 | 1 | 67.50 | 36 | 42.9 | 51.92 | 22 | 1 | High |

| YP7 | 0.712 | 76 | 6 | 71.15 | 36 | 34.3 | 50.63 | 31 | 2 | High |

| YP8 | 0.752 | 37 | 3 | 65.38 | 31 | 44.8 | 49.16 | 40 | 3 | High |

| Code | RII | RII Rank | RII Rank by Group | FI | FI Rank | FI Rank by Group | FAII | FAII Rank | FAII Rank by Group | Significant Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| YN | Claims Negotiation | |||||||||

| YN3 | 0.769 | 21 | 1 | 76.92 | 46 | 43.8 | 59.17 | 1 | 1 | very high |

| YN4 | 0.762 | 26 | 2 | 76.15 | 31 | 29.5 | 57.99 | 2 | 2 | very high |

| YN1 | 0.754 | 34 | 3 | 75.38 | 41 | 39 | 56.83 | 4 | 3 | very high |

| YN2 | 0.752 | 37 | 4 | 75.19 | 41 | 39 | 56.54 | 5 | 4 | very high |

| YN6 | 0.694 | 92 | 5 | 69.42 | 29 | 27.6 | 48.2 | 45 | 5 | High |

| Code | RII | RII Rank | RII Rank by Group | FI | FI Rank | FI Rank by Group | FAII | FAII Rank | FAII Rank by Group | Significant level |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| YR | Claims Resolution | |||||||||

| YR7 | 0.76 | 30 | 1 | 75.96 | 38 | 36.2 | 57.7 | 3 | 1 | very high |

| YR1 | 0.746 | 44 | 2 | 74.62 | 44 | 41.9 | 55.67 | 6 | 2 | very high |

| YR3 | 0.744 | 46 | 3 | 74.42 | 43 | 41 | 55.39 | 7 | 3 | very high |

| YR4 | 0.744 | 46 | 3 | 74.42 | 34 | 32.4 | 55.39 | 7 | 3 | very high |

| YR6 | 0.737 | 56 | 5 | 73.65 | 42 | 40 | 54.25 | 11 | 5 | very high |

| YR10 | 0.735 | 57 | 6 | 73.46 | 44 | 41.9 | 53.97 | 12 | 6 | very high |

| YR2 | 0.733 | 61 | 7 | 73.27 | 29 | 27.6 | 53.68 | 13 | 7 | very high |

| YR8 | 0.727 | 65 | 8 | 72.69 | 41 | 39 | 52.84 | 16 | 8 | very high |

| YR5 | 0.721 | 68 | 9 | 72.12 | 34 | 32.4 | 52.01 | 21 | 9 | High |

| YR9 | 0.719 | 71 | 10 | 71.92 | 42 | 40 | 51.73 | 24 | 10 | High |

| Code | RII | RII Rank | RII Rank | FI | FI Rank | FI Rank | FAII | FAII Rank | No. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| YN3 | Poor negotiation skills | 0.77 | 21.00 | 1 | 76.92 | 46.00 | 43.80 | 59.17 | 1 |

| YN4 | Adversarial relationship with other parties | 0.76 | 26.00 | 2 | 76.15 | 31.00 | 29.50 | 57.99 | 2 |

| YR7 | Balanced contracts such as FIDIC / ECC contracts are not used. | 0.76 | 30.00 | 1 | 75.96 | 38.00 | 36.20 | 57.70 | 3 |

| YN1 | Disagreement arising during negotiation. | 0.75 | 34.00 | 3 | 75.38 | 41.00 | 39.00 | 56.83 | 4 |

| YN2 | Unsatisfactory evidence to convince other parties | 0.75 | 37.00 | 4 | 75.19 | 41.00 | 39.00 | 56.54 | 5 |

| YR1 | Statement of claims, claims quantifications are not considered | 0.75 | 44.00 | 2 | 74.62 | 44.00 | 41.90 | 55.67 | 6 |

| YR3 | Lack of negotiating skill | 0.74 | 46.00 | 3 | 74.42 | 43.00 | 41.00 | 55.39 | 7 |

| YR4 | Lack of specified litigation prevention techniques (independent) | 0.74 | 46.00 | 3 | 74.42 | 34.00 | 32.40 | 55.39 | 7 |

| XM3 | Good communication with all stakeholders | 0.80 | 5.00 | 4 | 67.88 | 24.00 | 35.20 | 54.57 | 9 |

| YJ10 | The impact of the claims on project schedule not documented. | 0.78 | 16.00 | 4 | 70.00 | 36.00 | 33.30 | 54.38 | 10 |

| YR6 | Lack of expert report or Claim assessment | 0.74 | 56.00 | 5 | 73.65 | 42.00 | 40.00 | 54.25 | 11 |

| YR10 | Roles / responsibilities of contracting parties are not identified | 0.74 | 57.00 | 6 | 73.46 | 44.00 | 41.90 | 53.97 | 12 |

| YR2 | Expert knowledge and fully documented claims not considered | 0.73 | 61.00 | 7 | 73.27 | 29.00 | 27.60 | 53.68 | 13 |

| YD1 | Verbal instruction by owner has not documented. | 0.79 | 12.00 | 1 | 68.08 | 37.00 | 32.40 | 53.41 | 14 |

| YJ8 | Lack of awareness of site staff to notice a claim. | 0.76 | 32.00 | 7 | 70.19 | 38.00 | 38.10 | 53.05 | 15 |

| YR8 | The contract has no good management / effective risk sharing | 0.73 | 65.00 | 8 | 72.69 | 41.00 | 39.00 | 52.84 | 16 |

| XM7 | Clear and balanced contract terms and conditions regarding changes, claims and disputes resolution. | 0.81 | 3.00 | 2 | 64.81 | 24.00 | 29.50 | 52.34 | 17 |

| Level of risk likelihood/ consequence | Fuzzy triangular number (FTN) | Defuzzied number range | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| None | 0, 0, 0.1 | 0 | Risk event never happen, and no impact on the project. |

| Very Low | 0, 0.1, 0.3 | 0 to < 0.20 | Minimal probability to happen, and negligible impact. |

| Low | 0.1, 0.3, 0.5 | 0.20 to <0.40 | Low probability to happen, and minor impact. |

| Medium | 0.3, 0.5, 0.7 | 0.40 to <0.60 | Medium probability to happen and medium impact. |

| High | 0.5, 0.7, 0.9 | 0.60 to <0.80 | High probability to happen and notable impact. |

| Very High | 0.7, 0.9, 1.0 | 0.80 to <1.0 | Very high probability to happen, and critical impact. |

| Rank | Factor Code | Factor Name | Score |

| 1 | XR31 | Lack of payment certification guarantees and bonds and cash flow | 0.64249 |

| 2 | XR19 | Poor financial arrangement, leading to late payments | 0.63107 |

| 3 | XR18 | The owner changes his mind during construction | 0.62232 |

| 4 | XR2 | Acceptance of imprecise tender offers with lack of (clarifications, negotiations and recording of changes). | 0.61828 |

| 5 | XR28 | Payment delays on changing orders | 0.62436 |

| 6 | XR1 | Project execution time is short with lack of (site investigation, tender and contract documents). | 0.61699 |

| 7 | XR7 | Frequent changes and/or variations by the client. | 0.60808 |

| 8 | XR4 | Lack of experiences for designers, contract administrators and contractors. | 0.59453 |

| 9 | XR5 | Sudden swings in economic and market conditions. | 0.59501 |

| 10 | XR8 | Poor communications between project participants | 0.59344 |

| 11 | XR20 | Owner's reluctance to each decision that might be criticized | 0.57468 |

| 12 | XR27 | Design errors, omissions and contradictions in documents | 0.57878 |

| 13 | XR23 | Lack of procedure to correct errors between owner, designer and contractor | 0.56856 |

| 14 | XR33 | Constructive acceleration | 0.57357 |

| 15 | XR9 | Procurement problems | 0.57504 |

| 16 | XR29 | Price determination on change order. | 0.56525 |

| 17 | XR15 | Separate contracts (coordination problems). | 0.56477 |

| 18 | XR12 | Suspensions issues | 0.55816 |

| 19 | XR10 | Unbalanced risk allocation. | 0.54852 |

| 20 | XR25 | Contractor inability for site supervision and management | 0.54657 |

| 21 | XR24 | Conflict management | 0.53972 |

| 22 | XR16 | Untimely approvals. | 0.53936 |

| 23 | XR26 | Engineer's satisfaction clauses | 0.52872 |

| 24 | XR32 | Unclear employer applications and responsibilities of all the other parties | 0.53568 |

| 25 | XR22 | Misinterpretation of construction documents | 0.54167 |

| 26 | XR3 | Changes arising from local authority sources. | 0.53339 |

| 27 | XR14 | Indecisive management. | 0.52294 |

| 28 | XR11 | Unrealistic planning and specifications | 0.51864 |

| 29 | XR34 | Non-compliance with professional ethics in construction | 0.51695 |

| 30 | XR21 | Using unstudied design and elements for the first time | 0.51286 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).