Submitted:

27 April 2024

Posted:

29 April 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Background of the Study

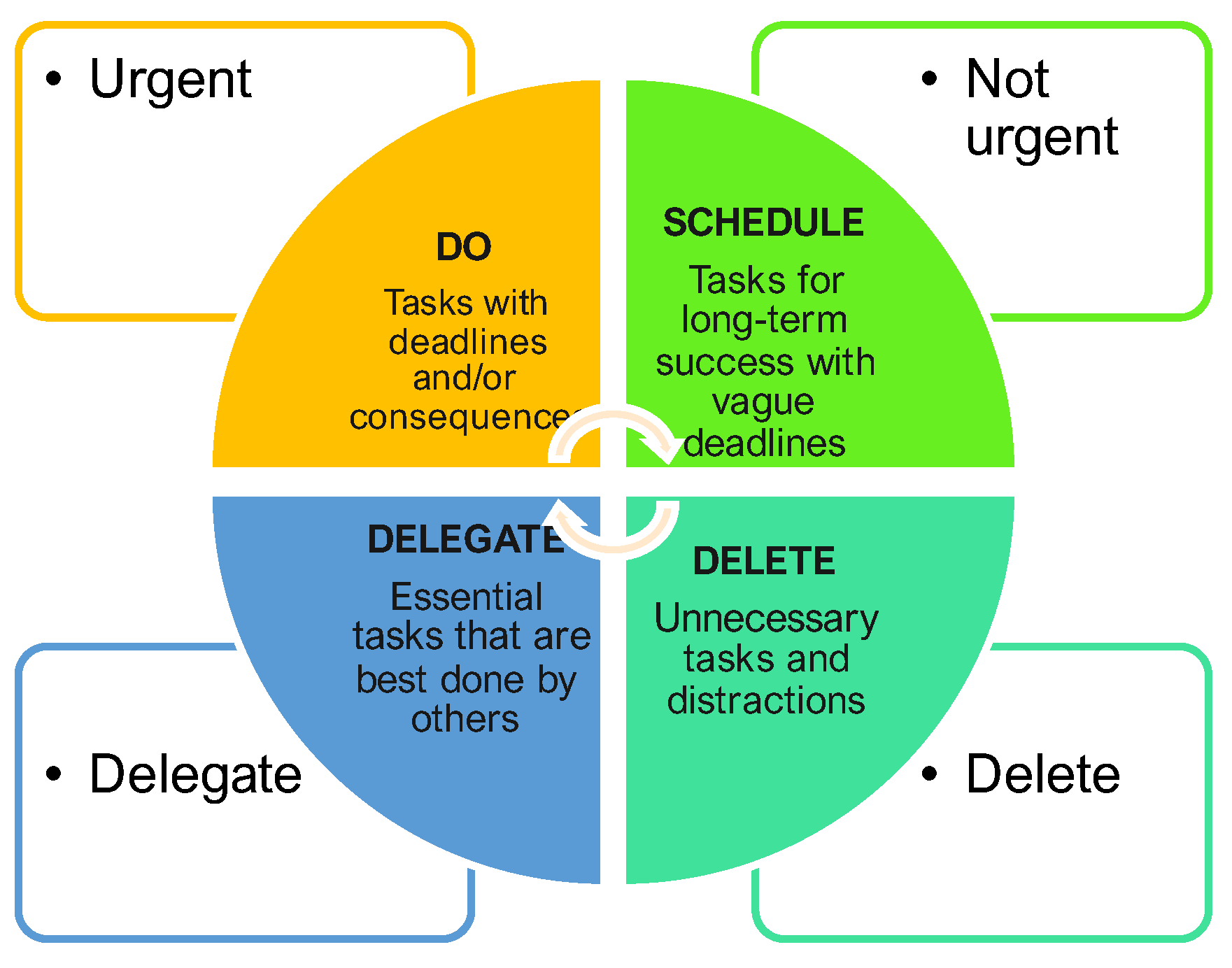

2.1. Time Management Techniques in Academia

2.2. The Timebooster Approach in Academic Time Management

2. Materials and Methods

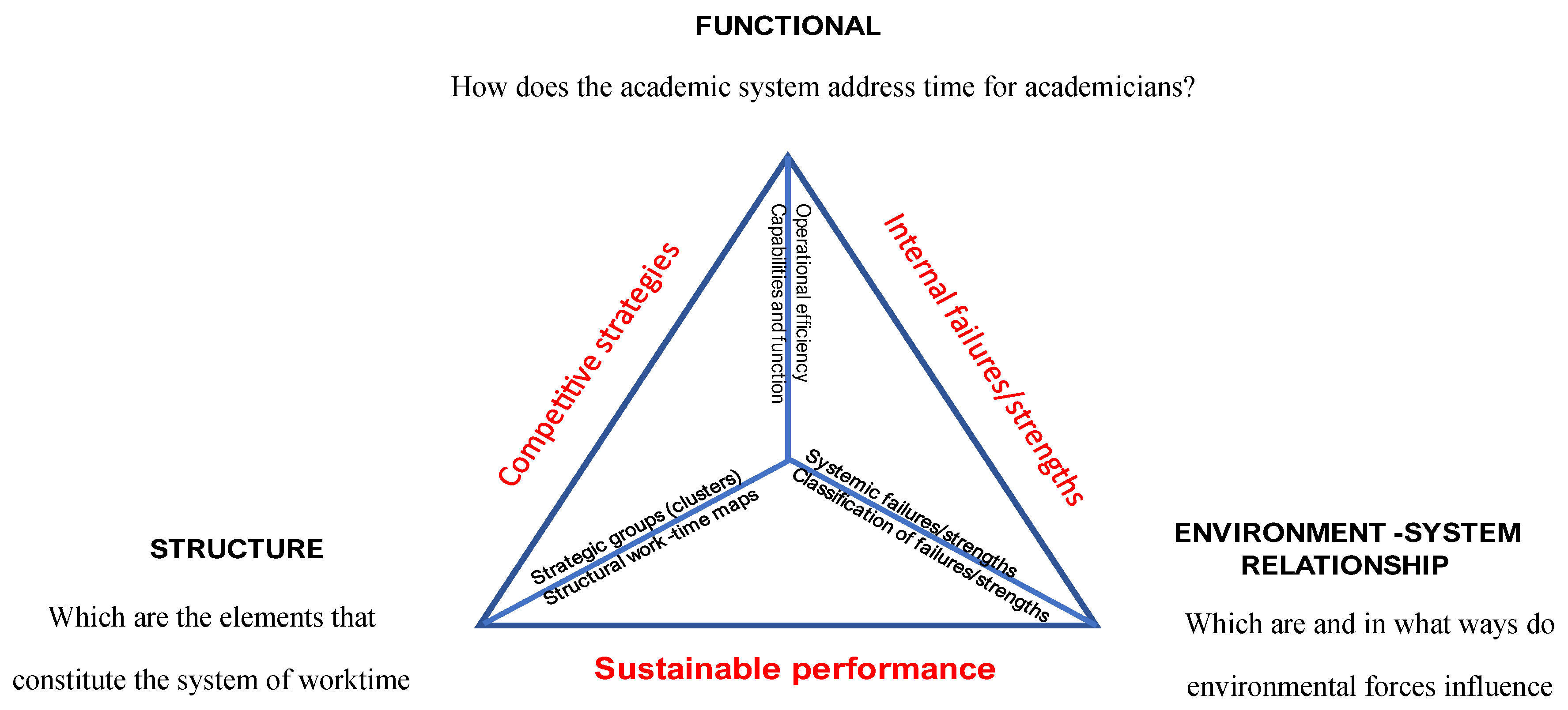

3. Methodology of the Systemic Designing of the Model

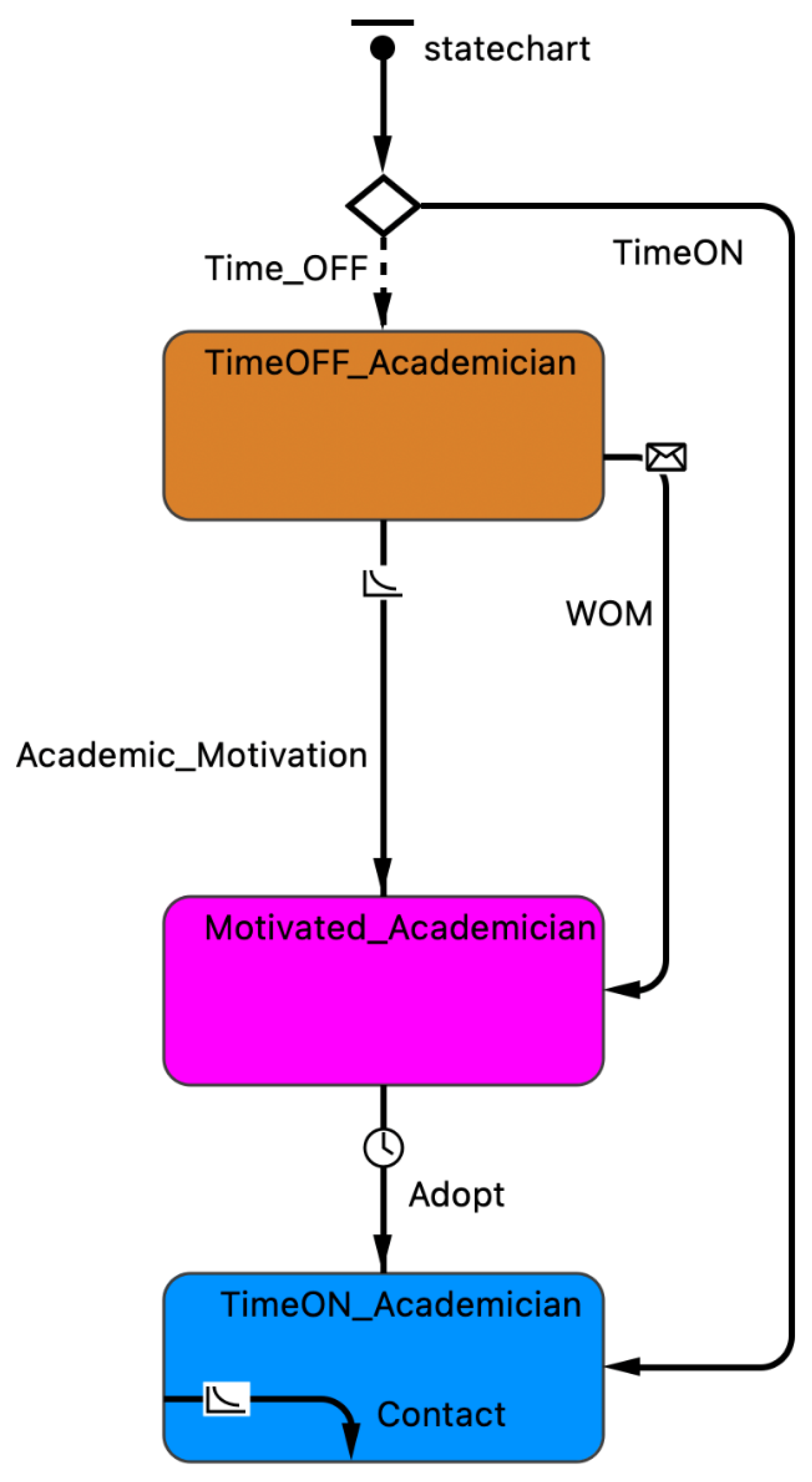

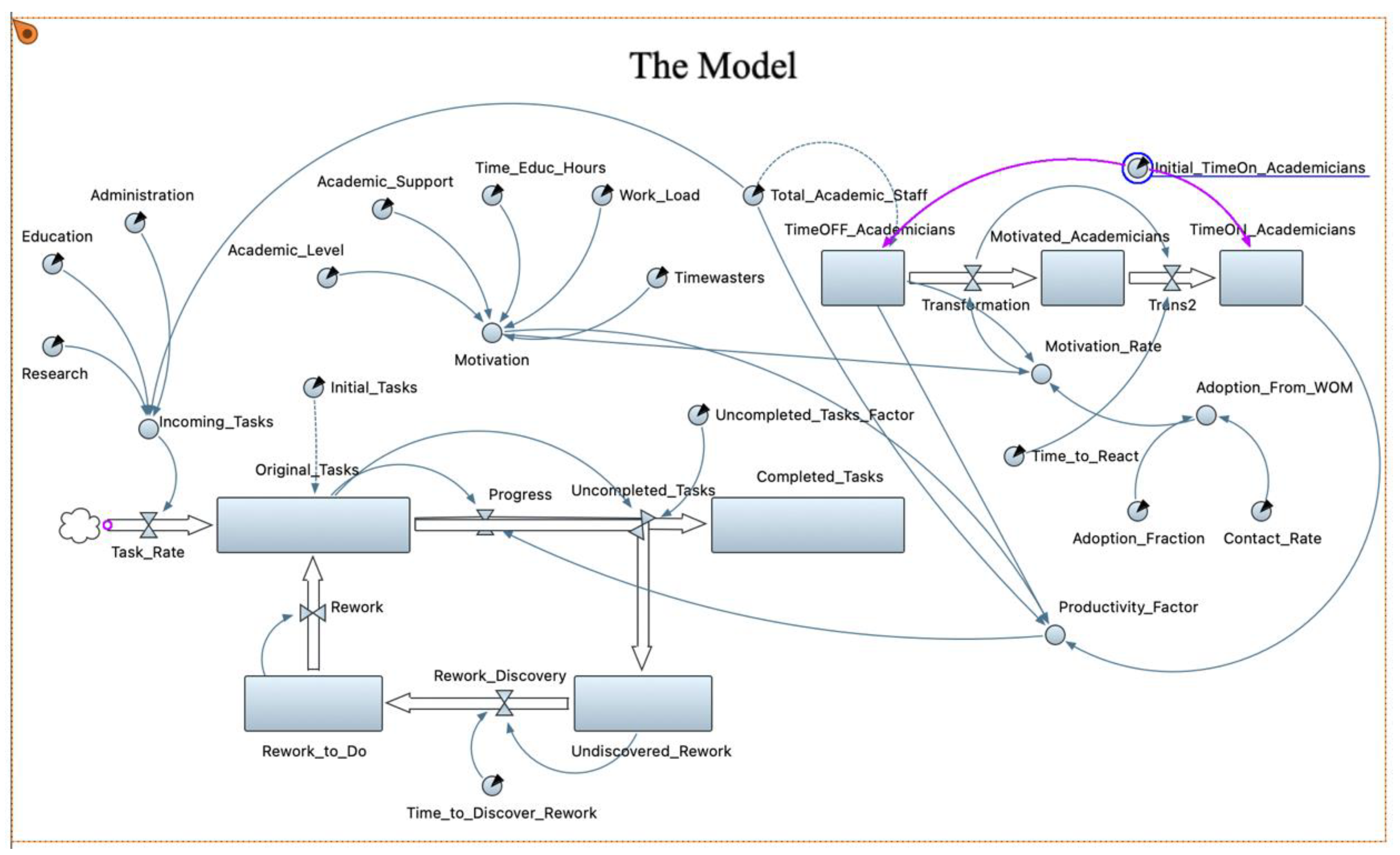

3.1. Modeling and Simulation

- The number of academic dentists embracing time management practices.

- The initial count of dentists integrating time management practices.

- The anticipated progression of dental personnel maturation, representing an increasing percentage of the total potential users of the time management philosophy.

- The average time needed for an academic professional to mature and adopt new time management practices.

- -

- Determining the timeframe for the complete dissemination of time management practices in academia.

- -

- Assessing the number of dentists within each subcategory, aiding in the planning of tailored educational support activities.

- -

- Identifying weaknesses in the dissemination of knowledge about time management.

- -

- Identifying and exploring factors influencing the spread of the Timebooster approach to time management.

3.2. Model Simulation

3.3. Model Execution

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Patents

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Goldsby, E., Goldsby, M., Neck, C.B., Neck, C.P. Under Pressure: Time Management, Self-Leadership, and the Nurse Manager. Administrative Science 2020, 10, 38. [CrossRef]

- Gluck, WF., Kaufman, P.S., Walleck, S. Strategic Management for Competitive Advantage. Harvard Business Review. July 1980. https://hbr.org/1980/07/strategic-management-for-competitive-advantage.

- Peschl M., Matlon M. 2021. What is the Meaning of VUCA World? https://www.thelivingcore.com/en/what-is-themeaning-of-vuca-world/.Posted: 1 February 2021.

- Baldwin, S. Living in a VUCA World. Mar 29 2022. https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/living-vuca-world-scottbaldwin?trk=articles_directory.

- Hambrick DC., Finkelstein S., Mooney A. Executive Job Demands: New Insights for Explaining Strategic Decisions and Leader Behaviors. Academy of Management Review 2005, 30(3):472-491. [CrossRef]

- Gardner JW. The Nature of Leadership. Introductory Considerations. 1986, Leadership Studies Program, Independent Sector Eds.

- Judge TA, Thoresen CJ, Bon JE, Patton GK. The job satisfaction , job performance relationship a qualitative and quantitative review. Psychological Bulletin 2001, 127, 3, 376-407.

- Wall TD, Jackson PR, Mullarkey S, Parker S. The Demand-Control Model Of Job Strain: A More Specific Test. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology 1996, 69(2):153-166. [CrossRef]

- Theorell, T. Karasek, R. A. Current Issues Relating to Psychosocial Job Strain and Cardiovascular Disease. Research. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 1996, 1: 9–26.

- Antoniadou, M. Leadership and Managerial Skills in Dentistry: Characteristics and Challenges Based on a Preliminary Case Study. Dental Journal 2022a, 10, 146. [CrossRef]

- Antoniadou M. Quality of Life and Satisfaction from Career and Work–Life Integration of Greek Dentists before and during the COVID-19 Pandemic. International Journal of Environmental research and Public Health 2022b, 19, 9865. [CrossRef]

- Daraio, C., Bonaccorsi, A., Simar, L. Rankings and University Performance: A Conditional Multidimensional Approach. European Journal of Operational Research, 2015, 244: 918–30.

- Allam, Z. & Ahmad, S. An Empirical Study of Quality in Higher Education in Relation to Stakeholders’ Perspectives. Journal of American Science, 2013, 9(12), 387-401.

- Condon, W., Iverson, E.R., Manduca, C.A., Rutz, C., Willett, G. Faculty development and student learning: Assessing the connections. Indiana University Press. 2016.

- Brown, J., Kurzweil, M. Instructional quality, student outcomes, and institutional finances. American Council on Education. 2018. Accessed online 20 April 2024 from https://www.acenet.edu/Documents/Instructional-Quality-Student-Outcomes-and-Institu-tionalFinances.pdf.

- Gewin, V. (2022). Has the ‘great resignation’ hit academia? 31 May https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-022-01512-6.

- Bass R., Eynon B., Gambino L.M. The new learning compact: A framework for professional learning and educational change. Every Learner Everywhere.2019. Accessed online 20 April 2024 from https://www.everylearnersolve.com/asset/YAhR8dclZb0mzn4v2zXh.

- Woolston, C. Nature 606, 211-213 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Gralka, S. (2018) Stochastic Frontier Analysis in Higher Education: A Systematic Review. CEPIE Working Papers 05/18, Technische Universität Dresden, Center of Public and International Economics (CEPIE).

- Aeon B, Faber A, Panaccio A. Does time management work? A meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2021, 16(1): e0245066. [CrossRef]

- Ailamaki A., Gehrke, J. Time Management for New Faculty. Sigmod Record 2003, 32(2).

- Hillestad, S.G., Berkowitz E.N. Health care market strategy: from planning to action. 2004, Jones and Bartlett Learning.

- Dodd P, Sundheim D. “The 25 Best Time Management Tools and Techniques: How to Get More Done Without Driving Yourself Crazy” John Wiley & Sons, 2011.

- Antoniadou, M.; Mangoulia, P.; Myrianthefs, P. Quality of Life and Wellbeing Parameters of Academic Dental and Nursing Personnel vs. Quality of Services. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2792. [CrossRef]

- Donnadieu G. L’Approche Systémique: De Quoi S’agit-il?. Synthèse Des Trav. Du Groupe AFSCET. “Diffus. La Pensée Systémique’’, 2003, 1–11.

- Ackoff, R.L., Emery, F.E. On Purposeful Systems. London: Tavistock Publications. 1972.

- Arnold E. Evaluating Research and Innovation Policy: A Systems World Needs Systems Evaluations’, Research Evaluation, 2004, 13: 3–17.

- De La Torre E.M., Casani, F., Sagarra, M. Defining Typologies of Universities through a DEA-MDS Analysis: An Institutional Characterization for Formative Evaluation Purposes. Research Evaluation, 2018, 27: 388–403.

- Waldrop MM. Complexity: The Emerging Science at the Edge of Order and Chaos. 1992, New York: Simon and Schuster Paperbacks.

- Jackson, M.C. Fifty Years of Systems Thinking for Management. Journal of the Operational Research Society, 2009, 60: S24–S32.

- Wieczorek, A.J., Hekkert, M.P. Systemic Instruments for Systemic Innovation Problems: A Framework for Policy Makers and Innovation Scholars. Science and Public Policy, 2012, 39: 74–87.

- Fagefors C, Lantz B, Rosén P. Creating Short-Term Volume Flexibility in Healthcare Capacity Management. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020 Nov 17;17(22):8514. [CrossRef]

- Covey, S. “The Seven Habits of Highly Effective People” Fireside, 1990.

- Harris, J. Time Management 100 Success Secrets: The 100 Most Asked Questions on Skills, Tips, Training, Tools and Techniques for Effective Time Management. Lulu Publications. 2008.

- Laredo, P. Revisiting the Third Mission of Universities: Toward a Renewed Categorization of University Activities? Higher Education Policy, 2007, 20: 441–56.

- Osterman, R. (2005). Attitudes count “soft skills” top list of what area employer’s desire. Sacramento Bee, May 23.

- Hashemiparast M, Negarandeh R, Theofanidis D. Exploring the barriers of utilizing theoretical knowledge in clinical settings: A qualitative study. Int J Nurs Sci. 2019 Sep 12;6(4):399-405. [CrossRef]

- Vizeshfar F, Rakhshan M, Shirazi F, Dokoohaki R. The effect of time management education on critical care nurses' prioritization: a randomized clinical trial. Acute Crit Care. 2022 May;37(2):202-208. [CrossRef]

- Metty P, Maglaras L, Amine Ferrag M, Almomani I. Digitization of healthcare sector: A study on privacy and security concerns. ICT Express, 2023, 9, (4), 571-588. [CrossRef]

- Mhlongo S., Mbatha K., Ramatsetse B., Dlamini R. Challenges, opportunities, and prospects of adopting and using smart digital technologies in learning environments: An iterative review. Heliyon, 2023, 9 (6), e16348. [CrossRef]

- Begley T. Effective time management. The New Jersey Lawyer, Inc. April 18, 2005, 14, 16, A6.

- Cummings, R., Holmes, L. Business Faculty time management: lessons learned from the trenches. American Journal of business Education 2009 2(1):35-30.

- Tobis, M., Tobis, I. Managing multiple projects. McGraw-Hill Professional. 2002.

- Shaw, D. Who has time for success? Manage Online, 2005, 3, 2.

- Borrás, S., Edquist C. Holistic Innovation Policy: Theoretical Foundations, Policy Problems, and Instrument Choices. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 2019.

- Rigby D, Sutherland S, Takeuchi H. Embracing Agile. Harvard Business Review May 2016. https://hbr.org/2016/05/embracing-agile.

- Buljac-Samardzic M, Doekhie KD, van Wijngaarden JDH. Interventions to improve team effectiveness within health care: a systematic review of the past decade. Hum Resour Health. 2020 Jan 8;18(1):2. [CrossRef]

- Collie R., Holliman A., Martin A. Adaptability, engagement and academic achievement at university. Educational Psycholog 2016. [CrossRef]

- Fleming, I. The Time Management Pocketbook. 6th edition, Management Pocketbooks.2011.

- Acuity training. 2022 (accessed online on 20 April 2024 from https://www.acuitytraining.co.uk/news-tips/time-management-statistics-2022-research/.

- Porta CR, Anderson MR, Steele SR. Effective time management: surgery, research, service, travel, fitness, and family. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2013 Dec;26(4):239-43. [CrossRef]

- Asana Team. The Eisenhower Matrix: How to prioritize your to-do list. January 29th, 2024. https://asana.com/resources/eisenhower-matrix.

- Kennedy DR, Porter AL. The Illusion of Urgency. Am J Pharm Educ. 2022, 86(7):8914. [CrossRef]

- Miyake, A., & Kane, M. J. Toward a Holistic Approach to Reducing Academic Procrastination With Classroom Interventions. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 2022, 31(4), 291-304. [CrossRef]

- Thomson T. Management by objectives. The Pfeiffer Library Volume 20, 2nd Edition. 1998, Jossey-Bass/Pfeiffer (accessed 20 April 2024 from chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://home.snu.edu/~jsmith/library/body/v20.pdf).

- Coito, T.; Firme, B.; Martins, M.S.E.; Vieira, S.M.; Figueiredo, J.; Sousa, J.M.C. Intelligent Sensors for Real-Time Decision-Making. Automation 2021, 2, 62-82. [CrossRef]

- Kamoun, S. (2022). Time management for academics- forget about the Eisenhower method. Zenodo( accessed online 20 April 2024 from https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6616905. https://kamounlab.medium.com/time-management-for-academics-forgetabout-the-eisenhower-method-15b380ade0a8.

- Kuh, G.D., O’Donnell K.O., Schneider, C.G. HIPs at ten. Change: The Magazine of Higher Learning, 2017, 49(5), 8–16. Association of American Colleges and Universities.

- Van Vught, F. Mission Diversity and Reputation in Higher Education. Higher Education Policy, 2008, 21: 151–74.

- Paige RD. The relationship between self-directed informal learning and the career development process of technology users. Walden University ScholarWorks (Accessed 20 April from chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://scholarworks.waldenu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1013&context=hodgkinson.

- Kamushadze T, Martskvishvili K, Mestvirishvili M, Odilavadze M. Does Perfectionism Lead to Well-Being? The Role of Flow and Personality Traits. Eur J Psychol. 2021 May 31;17(2):43-57. [CrossRef]

- Antony, M.M. Swinson, R.P. 2009: When Perfect isn’t good enough. New Harbinger, 2nd ed.

- Frost, R. O., Marten, P., Lahart, C., & Rosenblate, R. 1990: The dimensions of perfectionism. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 14, 449-468.

- Patterson, H. Firebaugh, C., Zolnikov, T. , Wardlow, R. , Morgan, S. and Gordon, B. A Systematic Review on the Psychological Effects of Perfectionism and Accompanying Treatment. Psychology, 2021, 12, 1-24. [CrossRef]

- Levine, I.S. Mind Matters: Too Perfect? Science Magazine: Careers. 28 March, 2008. [CrossRef]

- Hewitt, P. L., & Flett, G. L. Perfectionism in the self and social contexts: Conceptualization, assessment, and association with psychopathology. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 1991, 60, 456-470.

- Babaei S, Dehghani M, Lavasani FF, Ashouri A, Mohamadi L. The effectiveness of short-term dynamic/interpersonal group therapy on perfectionism; assessment of anxiety, depression and interpersonal problems. Res Psychother. 2022 Dec 29;25(3):656. [CrossRef]

- Stoeber, J. and Damian, L.E. 2016: Perfectionism in employees: Work engagement, workaholism, and burnout. In: Sirois, Fuschia M. and Molnar, Danielle S., eds. Perfectionism, health, and well-being. Springer, New York, 2016, 265-283. https://kar.kent.ac.uk/43727/.

- Rhaiem M. Measurement and Determinants of Academic Research Efficiency: A Systematic Review of the Evidence. Scientometrics, 2017, 110: 581–615.

- Xue L. Challenges and Resilience-Building: A Narrative Inquiry Study on a Mid-Career Chinese EFL Teacher. Front. Psychol., Sec. Positive Psychology 2021, 12. [CrossRef]

- Chase JA, Topp R, Smith CE, Cohen MZ, Fahrenwald N, Zerwic JJ, Benefield LE, Anderson CM, Conn VS. Time management strategies for research productivity. West J Nurs Res. 2013 Feb;35(2):155-76. [CrossRef]

- Antoniadou, M. Application of the humanities and basic principles of coaching in the Health Sciences; Tsotras: Athens, Greece, 2021.

- Cissna K. Self-actualized leadership: exploring the intersection of inclusive Self-actualized leadership: exploring the intersection of inclusive leadership and workplace spirituality at a faith-based institution of higher education. https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/ 2020 (accessed 20 April from chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2129&context=etd).

- Getman-Eraso, J., Culkin, K. High-impact catalyst for success: ePortfolio integration in the first-year seminar. In B. Eynon & L. M. Gambino (Eds.), Catalyst in action: Case studies of high-impact ePortfolio practice 2018, 32–49. Stylus.

- Doyle A. Important Time Management Skills For Workplace Success. December 16 2021, Accessed online 20 aApril 2024 from https://www.thebalancemoney.com/time-management-skills-2063776.

- Dweck C. What Having a “Growth Mindset” Actually Means. Harvard Business Review. January 13, 2016 (accessed 20 April from https://hbr.org/2016/01/what-having-a-growth-mindset-actually-means).

- Schuman-Olivier Z, Trombka M, Lovas DA, Brewer JA, Vago DR, Gawande R, Dunne JP, Lazar SW, Loucks EB, Fulwiler C. Mindfulness and Behavior Change. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2020 Nov/Dec;28(6):371-394. [CrossRef]

- Pervaiz S, Li G, He Q. The mechanism of goal-setting participation's impact on employees' proactive behavior, moderated mediation role of power distance. PLoS One. 2021 Dec 15;16(12):e0260625. [CrossRef]

- Radu C. Fostering a Positive Workplace Culture: Impacts on Performance and Agility [Internet]. Human Resource Management - An Update. IntechOpen; 2023. Available from:. [CrossRef]

- Thorgren S, Wincent J, Sirén C. The Influence of Passion and Work–Life Thoughts on Work Satisfaction. Human Resource Development Quarterly 2013, 24(4). [CrossRef]

- Simmons, S. 9 Ways to Handle Interruptions Like a Pro. 2011. Accessed on line 20 April 2024 from http://www.lifehack.org/articles/lifehack/9-ways-to-handle-interruptions-like-a-pro.html.

- Manz, C. C., & Manz, K. P. Taking time to consider time, work life, and spirituality: a case in point. Journal of Management, Spirituality & Religion, 2017, 14(4), 279–280. [CrossRef]

- Folabit NE, Reddy S, Jita LJ. Understanding Delegated Administrative Tasks: Beyond Academics' Professional Identities. African Journal of Inter/Multidisciplinary Studies 2023, 5(1):1-11. [CrossRef]

- James Jacob, W., Xiong, W., Ye, H. Professional development programmes at world-class universities. Palgrave Commun 2015, 1, 15002. [CrossRef]

- Sunder V., Mahalingam S. An empirical investigation of implementing Lean Six Sigma in Higher Education Institutions. International Journal of Quality & Reliability Management 2018, 35(10):2157-2180. [CrossRef]

- Davidson, C., Eversley, S. Practicing the equitable, transformative pedagogy we preach. Inside Higher Ed.2021. Accessed online 20 April 2024 from https://www.insidehighered.com/views/2021/08/16/academe-needs-structural-change-toward-more-equitablepedagogy-opinion.

- Kovačič Lukman R., Glavič P.What are the key elements of a sustainable university? Clean Technologies and Environmental Policy 2007, 9(2):103-114. [CrossRef]

- Kincaid L., Figueroa ME., Storey D., Underwood C.A Socio-Ecological Model of Communication for Social and Behavioral Change. A Brief Summary. Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health 2009, (accessed 20 April 2024 from chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://breakthroughactionandresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/socio-ecological-model-of-communication-for-sbc.pdf.

- Kincaid, DL., Figueroa, ME. Communication for participatory development: Dialogue, action, and change. In L.R. Frey and K.N. Cissna (Eds.) 2009, Routledge Handbook of Applied Communication Research. New York: Routledge (pp. 506–531). [CrossRef]

- White, K., Habib, R., & Hardisty, D. J. How to SHIFT Consumer Behaviors to be More Sustainable: A Literature Review and Guiding Framework. Journal of Marketing, 2019, 83(3), 22-49. [CrossRef]

- Addis BA, Gelaw YM, Eyowas FA, Bogale TW, Aynalem ZB, Guadie HA. "Time wasted by health professionals is time not invested in patients": time management practice and associated factors among health professionals at public hospitals in Bahir Dar, Ethiopia: a multicenter mixed method study. Front Public Health. 2023, 21, 11:1159275. [CrossRef]

- Restivo V, Minutolo G, Battaglini A, Carli A, Capraro M, Gaeta M, Odone A, Trucchi C, Favaretti C, Vitale F, Casuccio A. Leadership Effectiveness in Healthcare Settings: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Cross-Sectional and Before-After Studies. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022 Sep 2;19(17):10995. [CrossRef]

- Meirinhos, G.; Cardoso, A.; Neves, M.; Silva, R.; Rêgo, R. Leadership Styles, Motivation, Communication and Reward Systems in Business Performance. J. Risk Financial Manag. 2023, 16, 70. [CrossRef]

- Benneworth, P., Pinheiro R., Sánchez-Barrioluengo, M. One Size Does Not Fit All! New Perspectives on the University in the Social Knowledge Economy. Science and Public Policy, 2016, 43: 731–5.

- Becker, H, Mustric F. “Can I Have 5 Minutes of Your Time?” 2008, Morgan James Publishing.

- Macan, T.H. Time management training: Effects on time behaviours, attitudes, and job performance. Journal of Psychology, 1996, 130, 229-236.

- Woolthuis, R.K., Lankhuizen, M., Gilsing, V. A System Failure Framework for Innovation Policy Design. Technovation, 2005, 25: 609–19.

- Moudatsou M, Stavropoulou A, Philalithis A, Koukouli S. The Role of Empathy in Health and Social Care Professionals. Healthcare (Basel). 2020 Jan 30;8(1):26. [CrossRef]

- Yeo KT. Systems thinking and project management — time to reunite. International Journal of Project Management 1993, 11, (2), 111-117. [CrossRef]

- Tamminga SJ, Emal LM, Boschman JS, Levasseur A, Thota A, Ruotsalainen JH, Schelvis RM, Nieuwenhuijsen K, van der Molen HF. Individual-level interventions for reducing occupational stress in healthcare workers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2023 May 12;5(5):CD002892. [CrossRef]

- Bozeman B., Youtie J.,Jung J. Robotic Bureaucracy and Administrative Burden: What Are the Effects of Universities’ Computer Automated Research Grants Management Systems? Research Policy 2020, 49, (6), 103980. [CrossRef]

- Rensfeldt, A.B., Rahm, L. Automating Teacher Work? A History of the Politics of Automation and Artificial Intelligence in Education. Postdigit Sci Educ 2023, 5, 25–43. [CrossRef]

- Egbuchulem KI, Ogundipe HD, Uwajeh K. The future is yesterday: automating the thought process, an impending assault on academic writing. Ann Ib Postgrad Med. 2023 Aug;21(2):5-7. Epub 2023 Nov 1.

- Bornman J, Louw B. Leadership Development Strategies in Interprofessional Healthcare Collaboration: A Rapid Review. J Healthc Leadersh. 2023 Aug 23;15:175-192. [CrossRef]

- Bass R., Eynon B., Gambino L.M. (2019). The new learning compact: A framework for professional learning and educational change. Every Learner Everywhere. https://www.everylearnersolve.com/asset/YAhR8dclZb0mzn4v2zXh.

- Aparicio, J., Yaneth Rodríguez, D., Zabala-Iturriagagoitia, J.M. The systemic approach as an instrument to evaluate higher education systems: Opportunities and challenges. Research Evaluation, 2021, 30: 3, 336–348. [CrossRef]

- Pfeffer, T., Stichweh, R System theoretical perspectives on higher education policy and governance. In Huisman J, de Boer H, Dill D, Souto-Otero M. (eds) The Palgrave International Handbook of Higher Education Policy and Governance, 2015, 152–175. Houndmills, Basingtoke, Hampshire: Palgrave MacMillan.

- Kamalov, F.; Santandreu Calonge, D.; Gurrib, I. New Era of Artificial Intelligence in Education: Towards a Sustainable Multifaceted Revolution. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12451. [CrossRef]

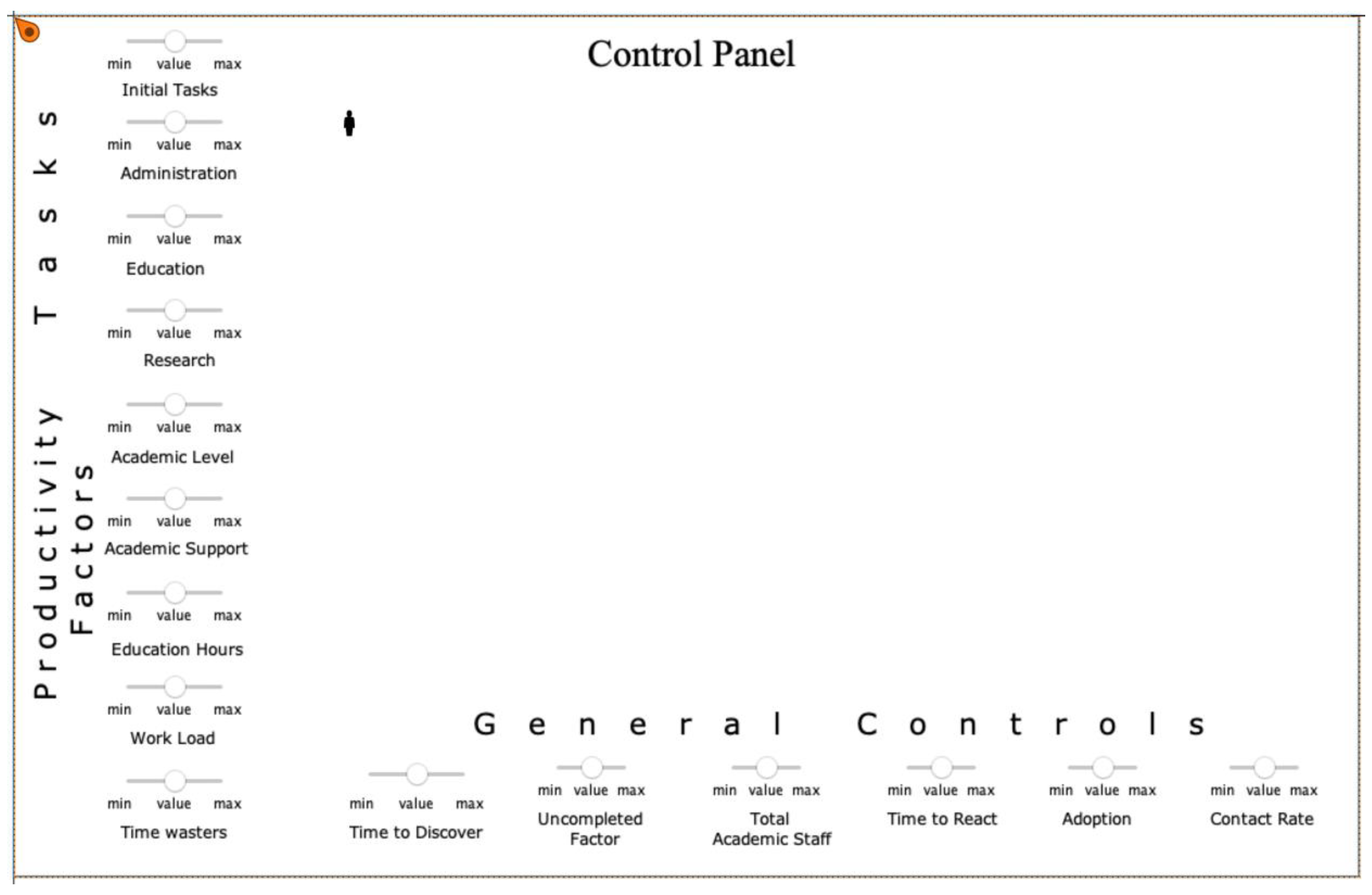

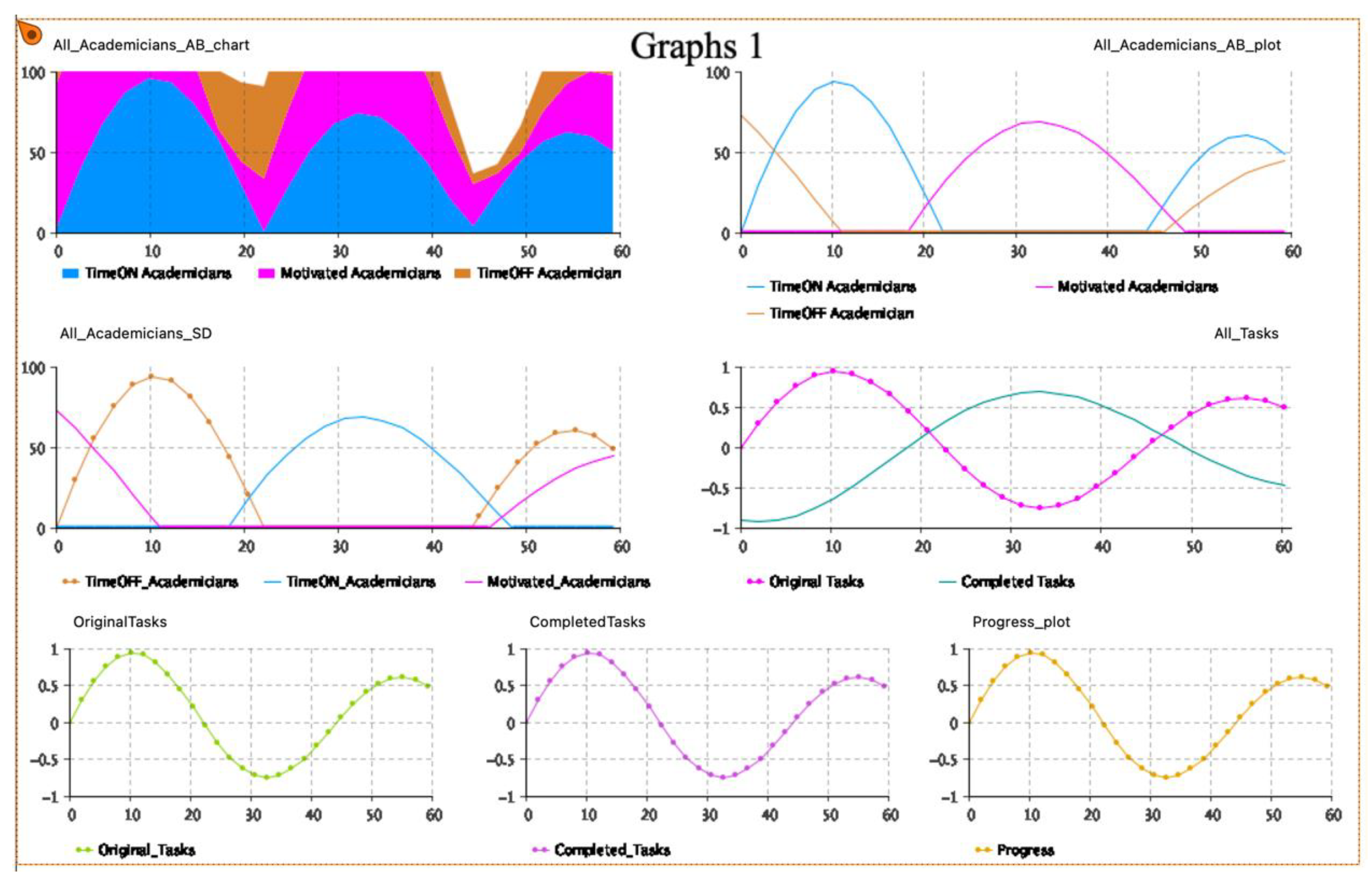

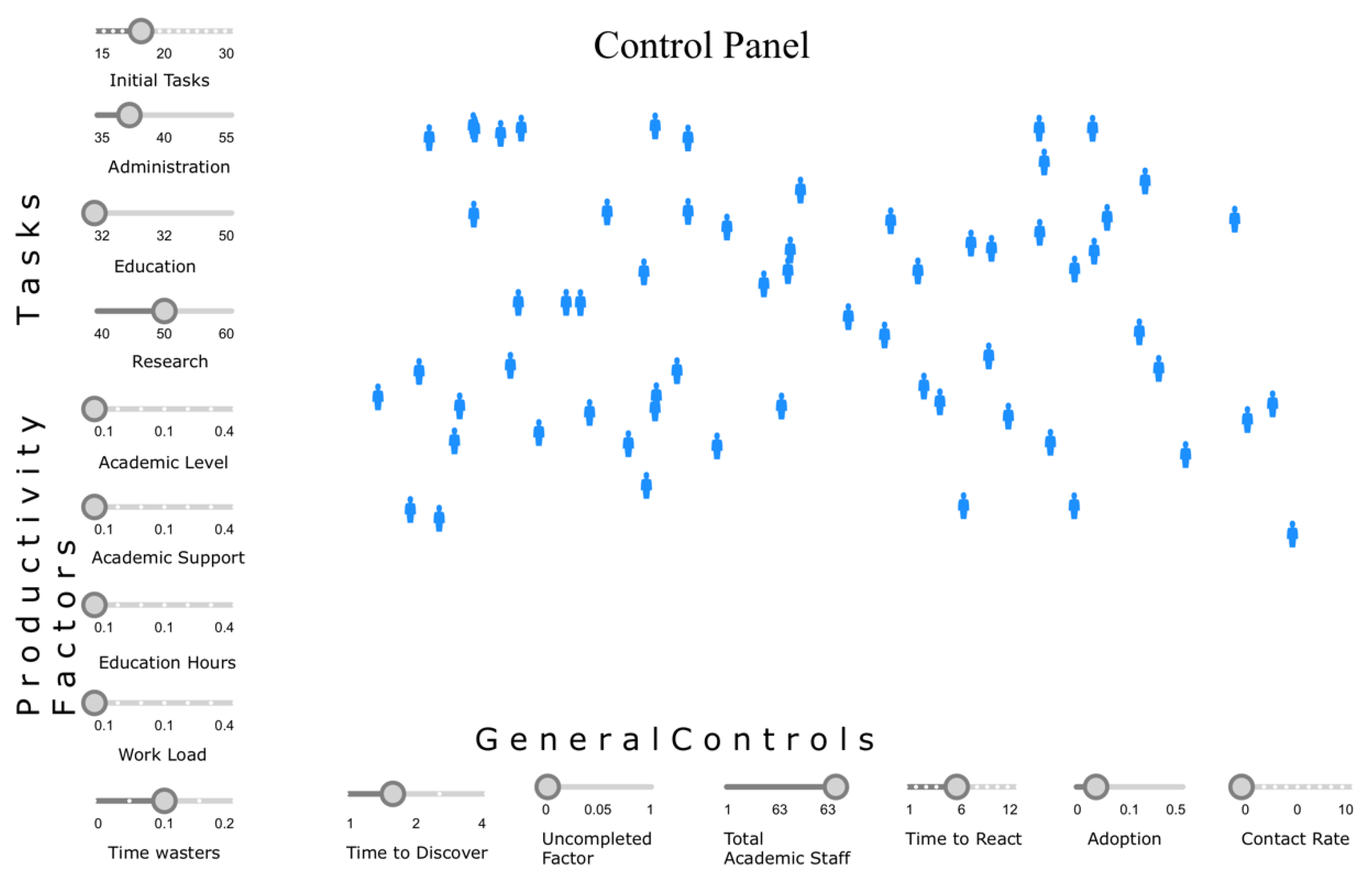

| Setting | Value |

| INITIAL TIME | 0 months |

| FINAL TIME | 60 months (simulation time = 5 years) |

| Time Unit | 1 month |

| Stocks | Explanation |

| Original_Tasks | The overall tasks created |

| Rework_to_Do | The tasks that have to be redone |

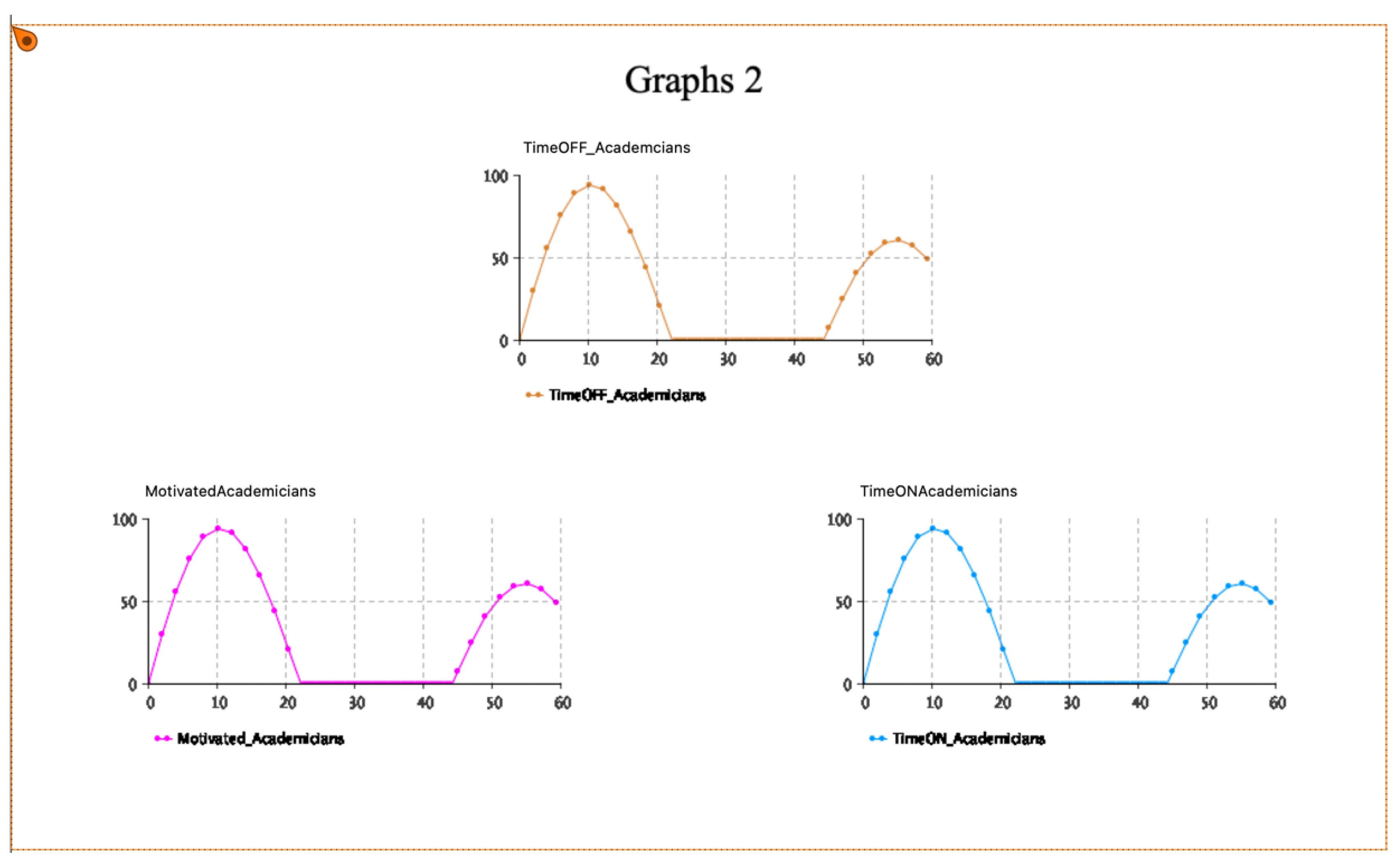

| TimeOFF_Academicians | The number of dentists who do not apply time management |

| TimeON_Academicians | The TIME ON Academic Dentists |

| Completed_Tasks | The Overall Completed Tasks |

| Undiscovered_Rework | The undiscovered tasks to be performed |

| Motivated_Academicians | The Motivated Academic Dentists |

| Dynamic Variables | Explanation |

| Productivity_Factor | The productivity factor |

| Incoming_Tasks | The tasks to be fulfilled for the total Academic staff per time unit |

| Motivation_Rate | Both Academic and WOM motivation |

| Adoption_From_WOM | The WOM adoption |

| Motivation | The Academic motivation |

| Parameters | Explanation |

| Administration | The Administration tasks per time unit |

| Education | The Education tasks per time unit |

| Research | The Research tasks per time unit |

| Time_to_Discover_Rework | The delay time to discover rework to be done |

| Academic_Support | The level of Academic support per time unit |

| Time_Educ_Hours | The level of education hours |

| Academic_Level | The Academic level |

| Work_Load | The workload level |

| Timewasters | The time wasters’ level |

| Adoption_Fraction | The percentage of WOM adoption |

| Contact_Rate | The number of contacts per time unit |

| Initial_TimeOn_Academicians | The number of initial TIME ON Academic Dentists |

| Total_Academic_Staff | The total Academic Dentists staff |

| Time_to_React | The time it takes to the Motivated Academic Dentists to become TIME ON Academic Dentists |

| Initial_Tasks | The number of initial tasks |

| Uncompleted_Tasks_Factor | The percentage of uncompleted tasks per time unit |

| Flows | Explanation |

| Progress | The completed tasks per time unit |

| Task_Rate | The tasks to be fulfilled of the total Academic Dentists staff per time unit |

| Rework | The discovered uncompleted tasks to be fulfilled per time unit |

| Uncompleted_Tasks | The uncompleted tasks per time unit |

| Transformation | The TIME OFF Academic Dentists who become Motivated Academic Dentists per time unit |

| Trans2 | The acceptance of time management philosophy and the transformation of Motivated Dentists into TIME ON Dentists |

| Rework_Discovery | The discovered uncompleted tasks per time unit |

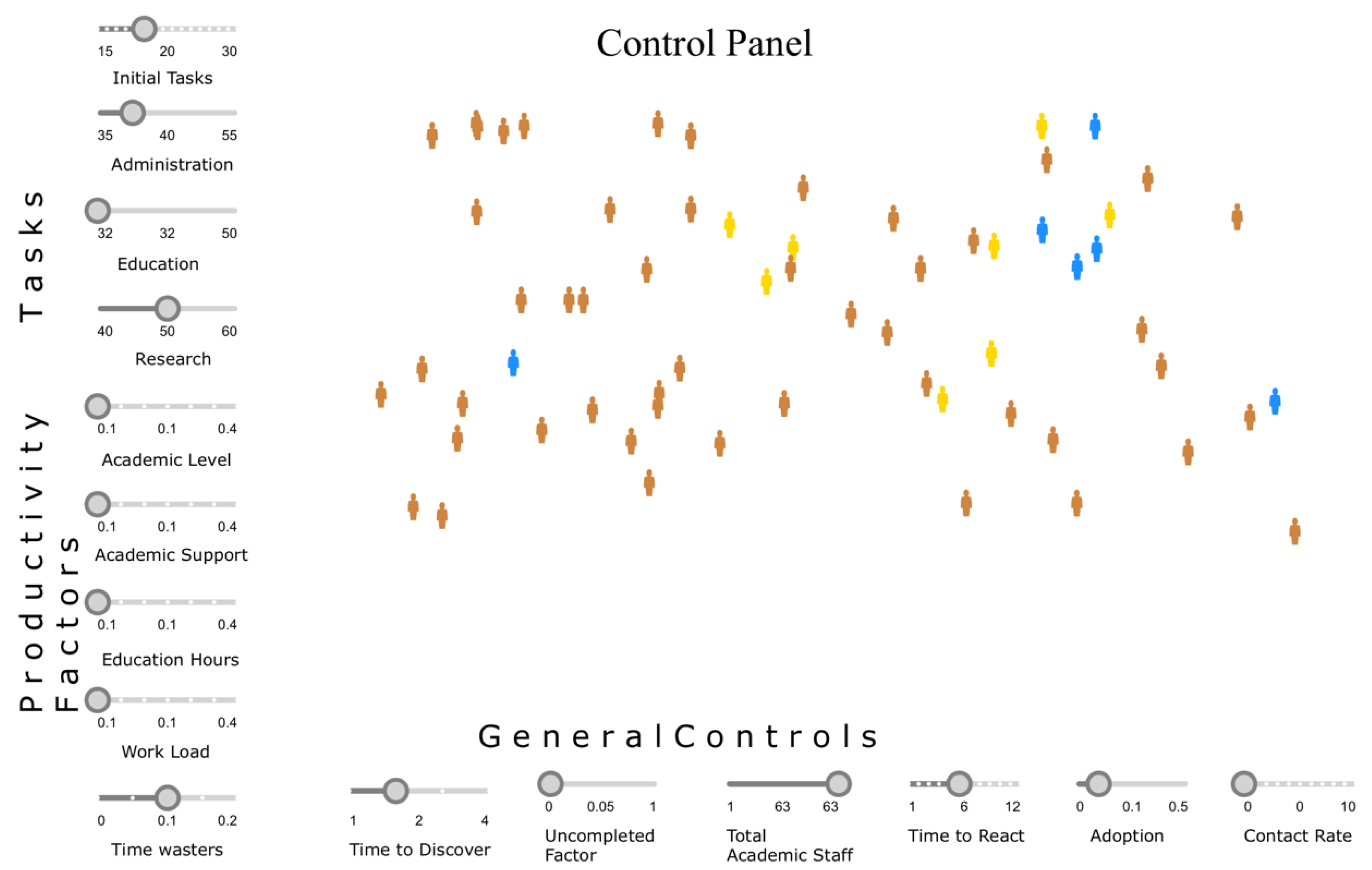

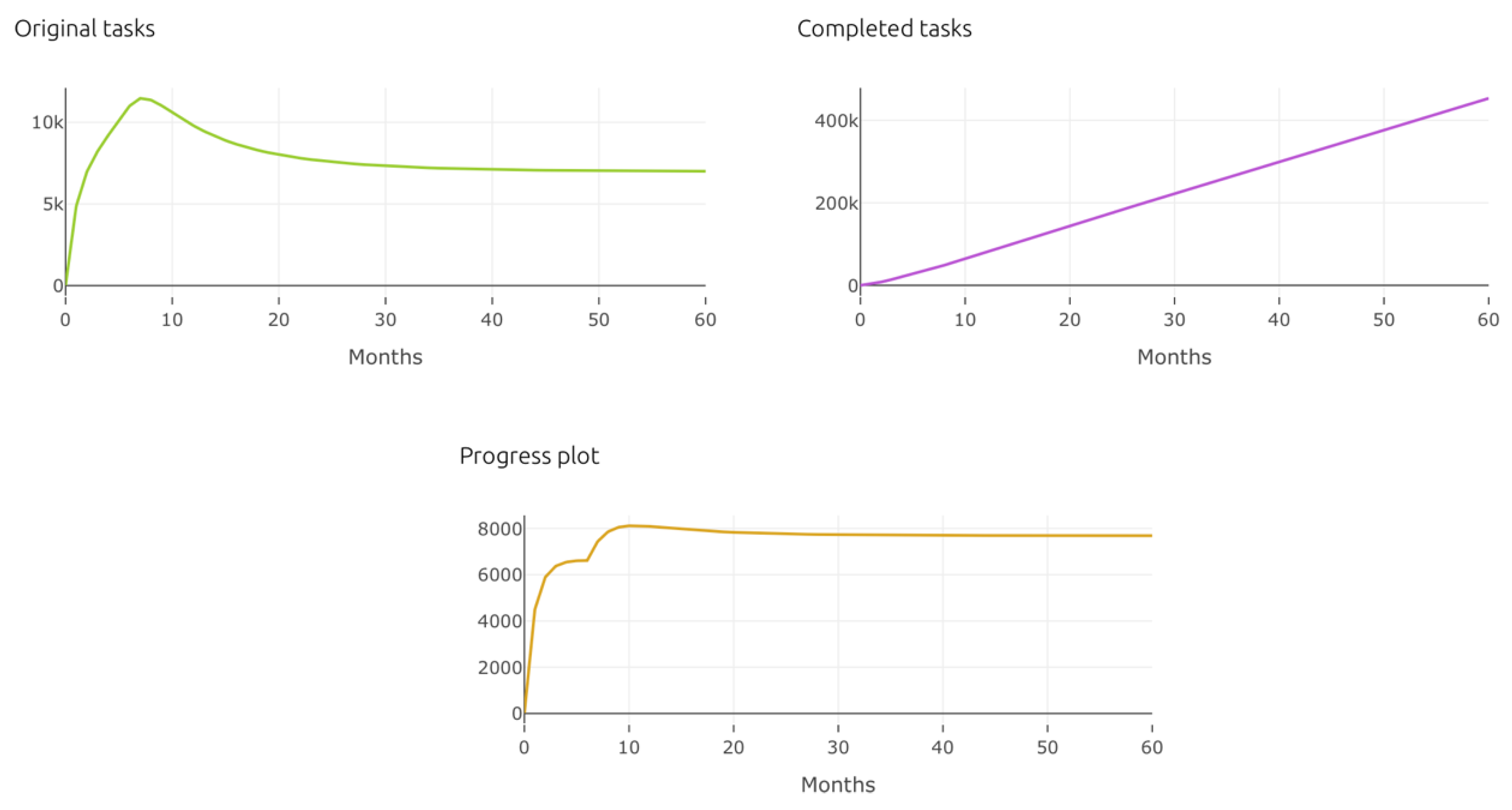

| Name | Value | Units |

| Administration | 40 | |

| Education | 32 | |

| Research | 50 | |

| Time to discover rework | 2 | Months |

| Academic support | 0,1 | |

| Time educ hours | 0,1 | |

| Academic_Level | 0,1 | |

| Work load | 0,1 | |

| Timewasters | 0,1 | |

| Adoption fraction | 0,1 | |

| Contact rate | 0 | |

| Initial time on academicians | 6 | |

| Total academic staff | 63 | |

| Time_to_React | 6 | Months |

| Initial tasks | 20 | |

| Uncompleted tasks factor | 0,05 |

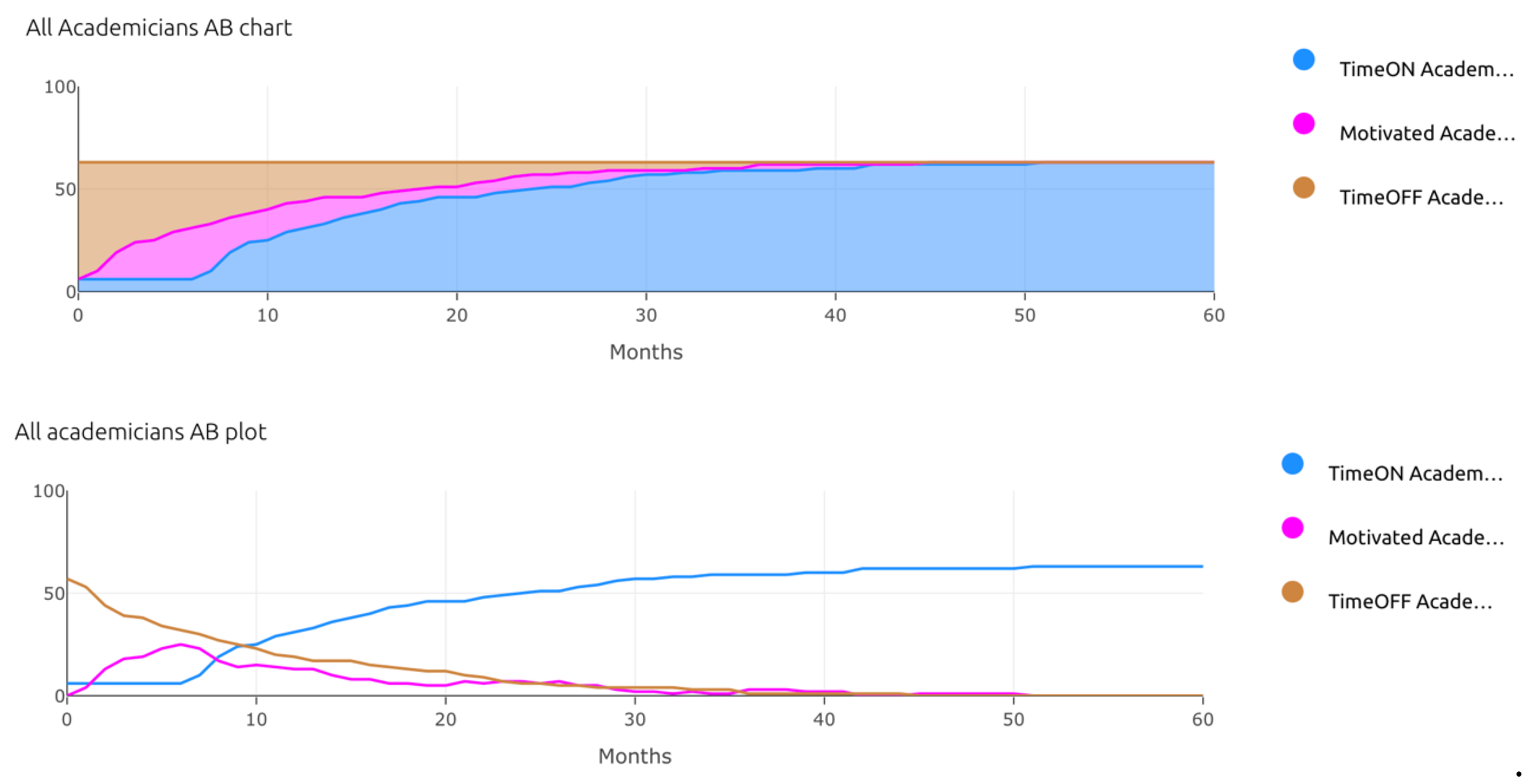

| Name | Value | Units |

| Administration | 40 | |

| Education | 32 | |

| Research | 50 | |

| Time to discover rework | 2 | Months |

| Academic support | 0,1 | |

| Time educ hours | 0,1 | |

| Academic_Level | 0,1 | |

| Work load | 0,1 | |

| Timewasters | 0,1 | |

| Adoption fraction | 0,1 | |

| Contact rate | 2 | |

| Initial time on academicians | 6 | |

| Total academic staff | 63 | |

| Time_to_React | 6 | Months |

| Initial tasks | 20 | |

| Uncompleted tasks factor | 0,05 |

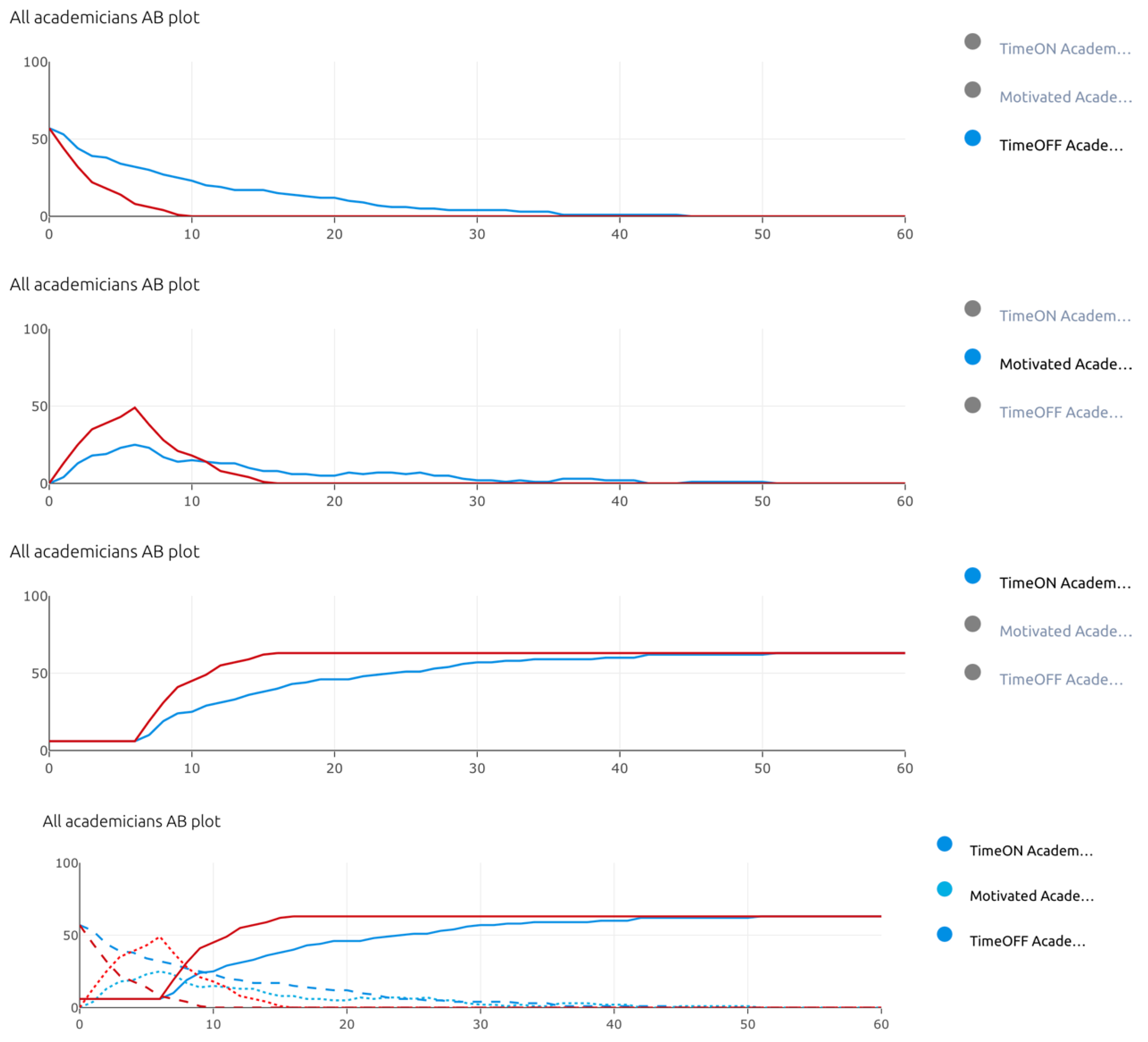

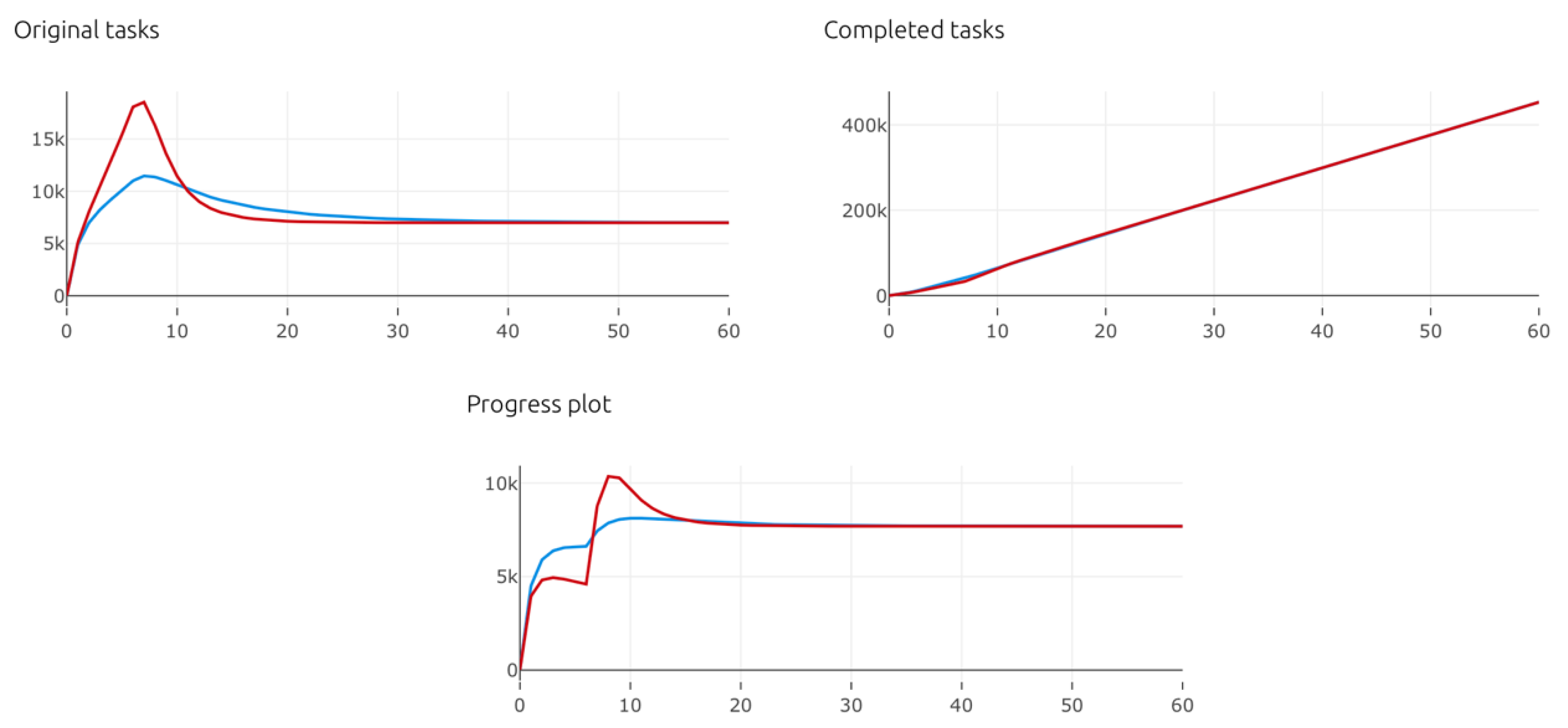

| Name | Value A | Value B |

| Administration | 40 | 40 |

| Education | 32 | 32 |

| Research | 50 | 50 |

| Time to discover rework | 2 | 2 |

| Academic support | 0,1 | 0,1 |

| Time educ hours | 0,1 | 0,1 |

| Academic_Level | 0,1 | 0,1 |

| Work load | 0,1 | 0,1 |

| Timewasters | 0,1 | 0,1 |

| Adoption fraction | 0,1 | 0,1 |

| Contact rate | 0 | 2 |

| Initial time on academicians | 6 | 6 |

| Total academic staff | 63 | 63 |

| Time_to_React | 6 | 6 |

| Initial tasks | 20 | 20 |

| Uncompleted tasks factor | 0,05 | 0,05 |

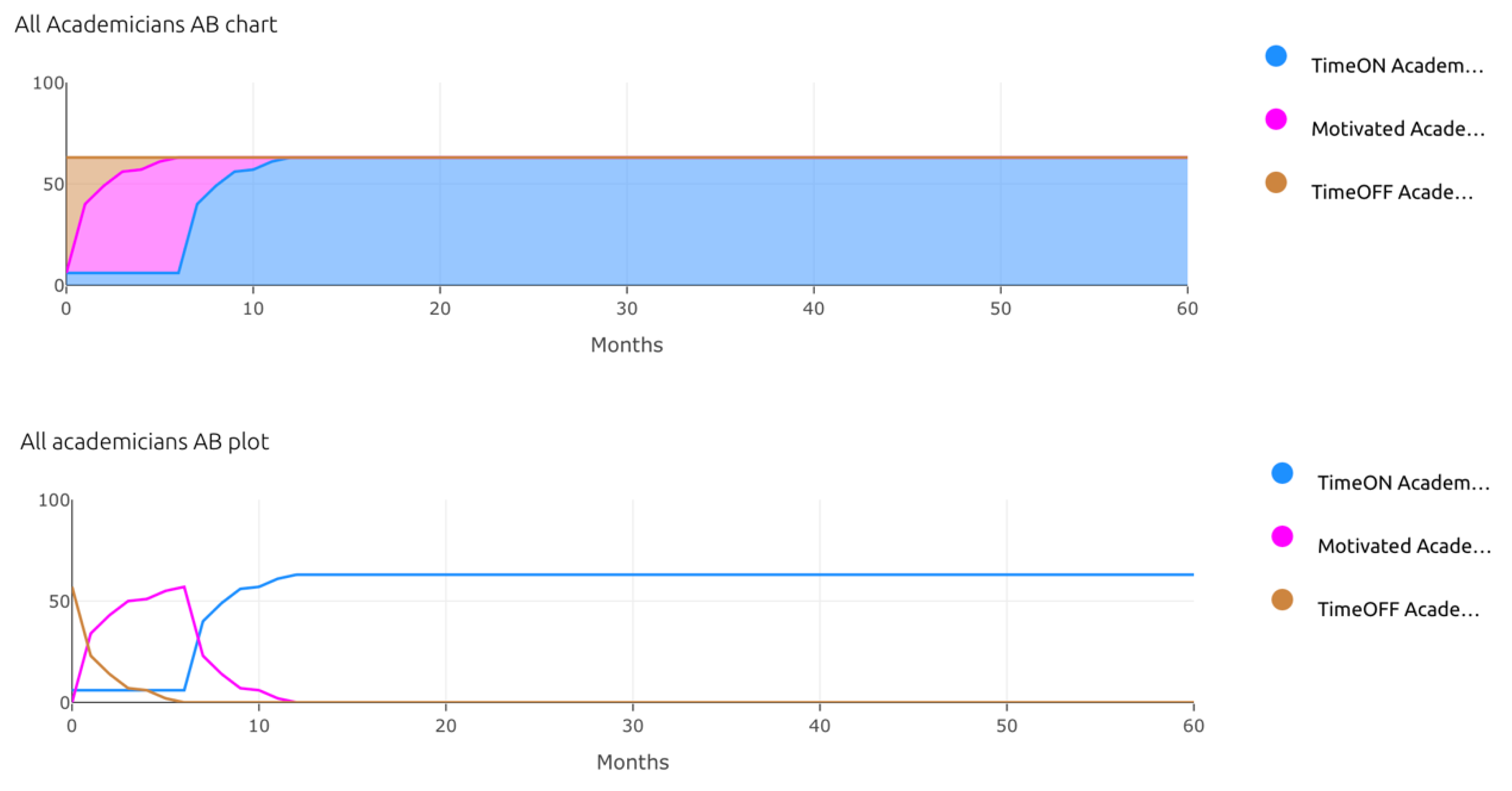

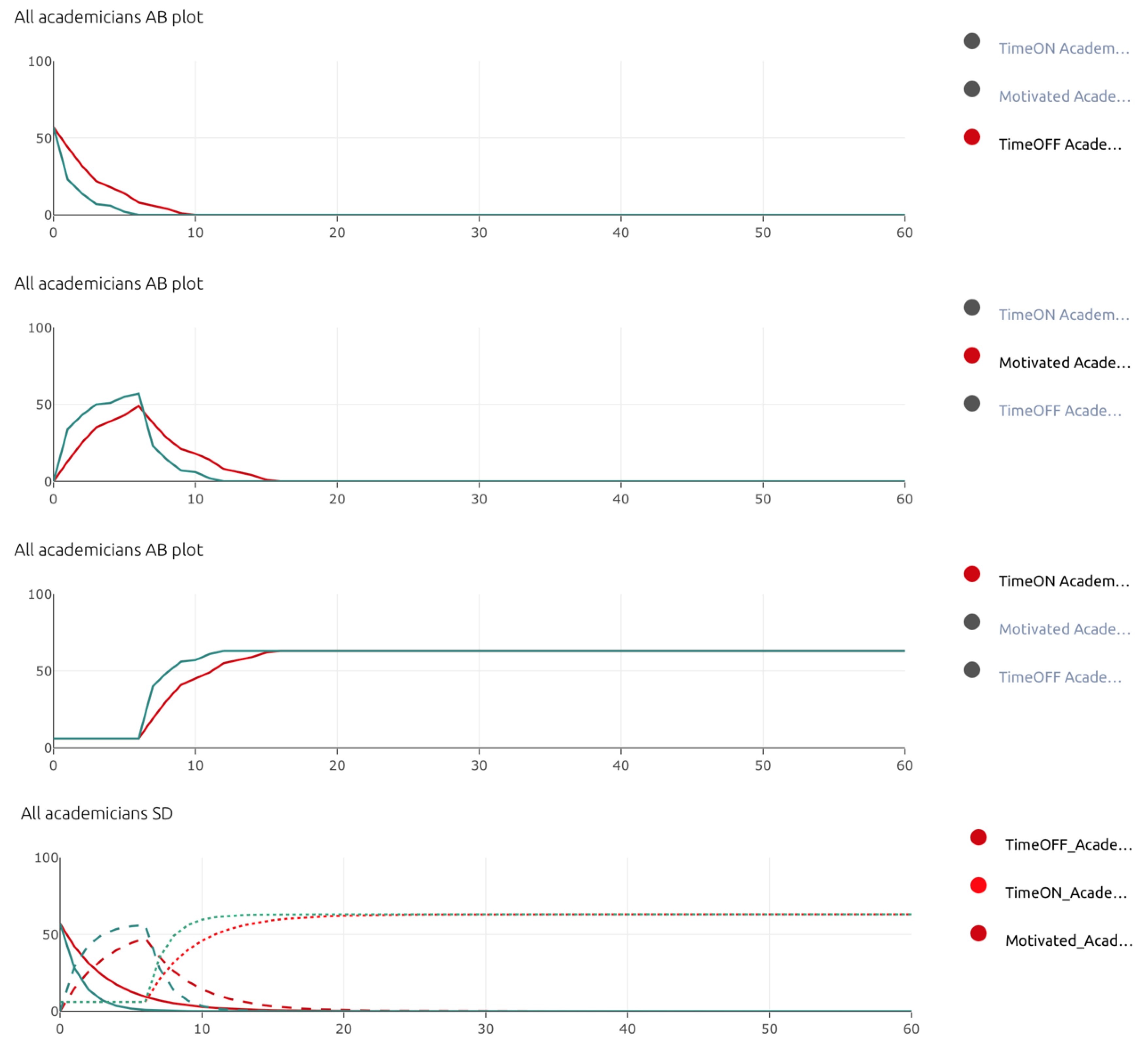

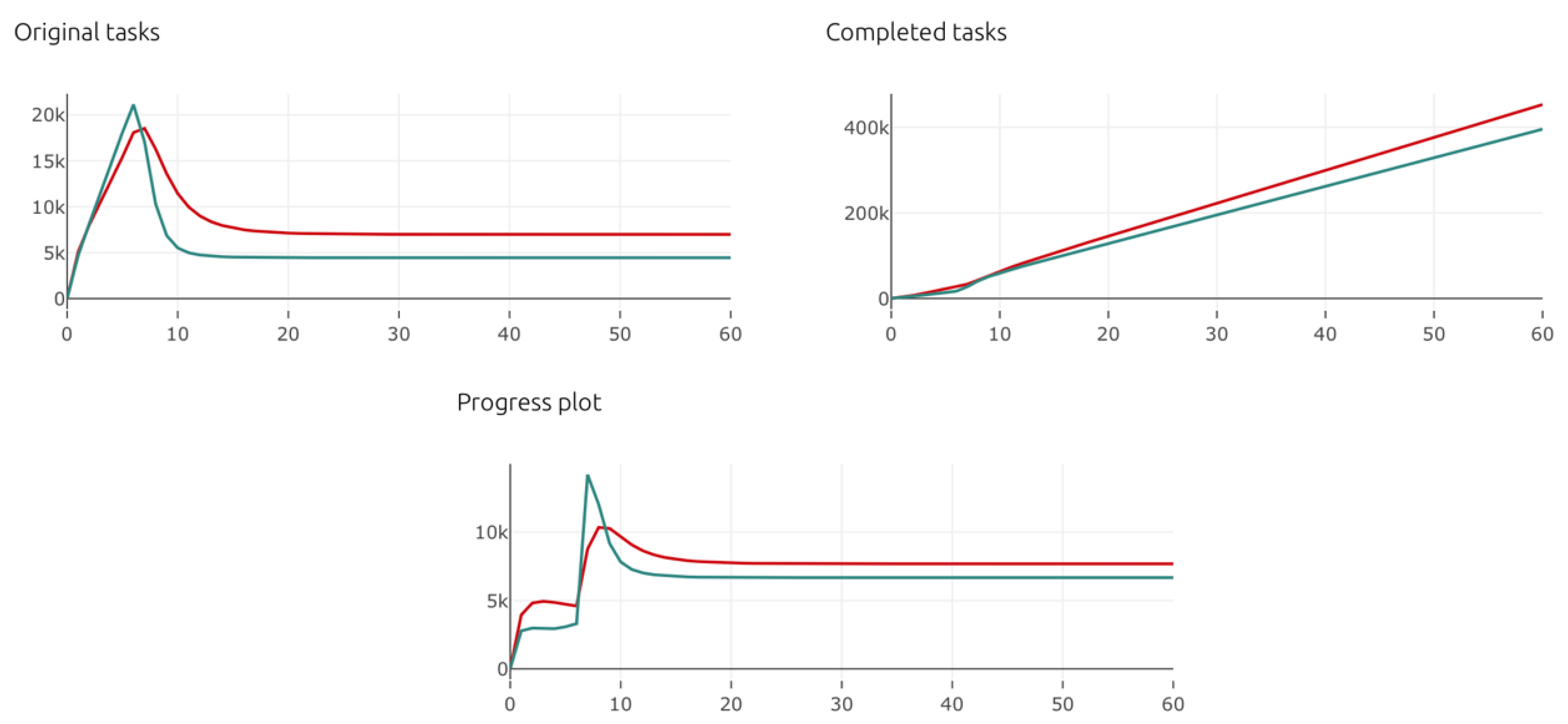

| Name | Value B | Value C |

| Administration | 40 | 24 |

| Education | 32 | 32 |

| Research | 50 | 50 |

| Time to discover rework | 2 | 2 |

| Academic support | 0,1 | 0,2 |

| Time educ hours | 0,1 | 0,2 |

| Academic_Level | 0,1 | 0,2 |

| Work load | 0,1 | 0,05 |

| Timewasters | 0,1 | 0,05 |

| Adoption fraction | 0,1 | 0,1 |

| Contact rate | 2 | 2 |

| Initial time on academicians | 6 | 6 |

| Total academic staff | 63 | 63 |

| Time_to_React | 6 | 6 |

| Initial tasks | 20 | 20 |

| Uncompleted tasks factor | 0,05 | 0,05 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).