1. Introduction

In spite of numerous efforts to address hunger, there has been no significant decrease in the global prevalence of hunger in recent years. Many nations and geographical areas have been grappling with severe hunger in recent time, with situation expected to worsen in early 2024 [

1]. Though, the Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) and its partners reporting a plateau in the prevalence of undernourishment (PoU) in 2021-2022, Western Asia, the Caribbean and all sub-regions of Africa persisted in experiencing an increase in hunger [

2,

3,

4]. The onset of COVID-19 pandemic, Russia-Ukraine conflict, climate crises, poverty, increasing inequalities, and skyrocketing food prices have all intensified the prevailing hunger and elevated levels of food insecurity (FI) on a global scale [

2,

5]. It is worth noting that the weight of these burden is being borne by significant demographic segments, including women and young people. However, both South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) regions recorded the highest hunger levels in 2023, having Global Hunger Index (GHI) scores of 27.0 each, signifying a significant prevalence of hunger in these areas. Approximately 691 to 783 million individuals globally encountered hunger in 2022. Taking the midrange (735 million), there was an increase of 122 million people facing hunger in 2022 compared to 2019, prior to COVID-19. However, recent estimates suggest that nearly 600 million individuals will face chronic undernourishment by 2030, underscoring the substantial challenge of meeting the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) target to eliminate hunger, especially in Africa [

3,

6].

Roughly 29.6 percent (2.4 billion) of the world’s population experienced moderate to severe food insecurity in 2022, with approximately 11.3 percent (900 million) facing severe food insecurity. In 2022, 33.3 percent of adults (especially women) in rural regions experienced moderate or severe food insecurity, contrasting with 28.8 percent in peri-urban areas 26.0 percent in urban areas [

3,

6]. Additionally, stunting in under-five children reached 22.3 percent while child wasting and overweight (obesity) reached 6.8 and 5.6 percent in 2022 respectively. The term “hunger”, according to United Nations (UN) is referred to as “the periods when people experience severe food insecurity – meaning that they go for the entire day without eating due to lack of money, access to food, or other resources” [

7]. Additionally, FAO also defined hunger as “an uncomfortable or painful physical sensation caused by insufficient consumption of dietary energy. It becomes chronic when the person does not consume a sufficient amount of calorie (dietary energy) on a regular basis to lead a normal, active and healthy life” [

3].

However, Sustainable Development Goal 2 (SDG 2) aims to establish a hunger-free world by 2030 [

3,

8,

9,

10,

11]. Sustainable Development Goal 2 as one of the 17 SDGs is designed to motivate member countries to eliminate hunger, attain food security and enhanced nutrition, and foster sustainable agriculture by 2030 [

8]. Food security is entrenched in SDG 2 and according to the UN definition, it is when “people having at all times, physical, social and economic access to sufficient, safe and nutritious food which meets their dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life” [

12]. Food insecurity (FI) is the absence of food security, where the conditions for food security are not fulfilled, and it can be understood as a continuum ranging from mild to severe [

6,

13]. While hunger is basically a condition of food deprivation or a lack of resources to acquire it, FI can manifest at various levels of severity, ranging from mild to moderate or severe. This paper seeks to explore the recent hunger and food insecurity situation globally. Previous studies have x-rayed the fight against hunger in Africa [

9,

10], zero hunger in the face of COVID-19 in Africa, [

14], achieving Zero Hunger in Africa [

15], monitoring food system transformation [

11], and healthy, sustainable diets, development pathways to zero hunger [

16,

17]. However, this study conducted a comprehensive examination of the prevalence and severity of hunger and FI across various countries and regions.

This is a narrative review that utilised the most recent data from reputable organisations, including year 2008, 2012, 2018, 2020, 2022, and 2023. These organisations include Welt hunger hilfe (WHH) and Concern worldwide (Global Hunger index 2023); Economist Impact (Global Food Security Index 2022); and Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) and partners (The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the world 2023). The resources include some metrics such as (i) Global Hunger Index (GHI) scores, (ii) Global Food Security Index (GFSI) scores, (iii) 2023 data from FAO and other partners, and (iv) other relevant resources. The study also incorporated data related to two SDG 2 targets: 2.1 indicators, namely the PoU and the prevalence of moderate/severe FI based on the Food Security Experience Scale (FIES), and other resources to assess the current status of the countries included in this study.

2. Hunger is Everywhere

Global hunger, as evidenced by the prevalence of undernourishment (SDG indicator 2.1.1), remained significantly higher in 2022 than the pre-pandemic levels. Approximately 9.2% of the global population experienced chronic hunger in 2022, up from 7.9% in 2019. Although, according to FAO et al. [

3] estimates, the level of hunger continued to decrease since 2005 from 12.1% (793.4 million) to 8.6% (597.8 million) in 2010. There was a sharp increase in global hunger in 2019, rising from 7.9% (612.8 million) in 2019 to 8.9% (701.4 million) in 2020 while hunger level witness a slight reduction between 2021 and 2022, moving from 9.3% (738.9 million) to 9.2% (735.1 million). However, the percentage of the population grappling with hunger is notably higher in Africa in comparison to other global regions, with about 20% affected, in contrast to 8.5% in Asia, 6.5% in Latin America and the Caribbean, and 7.0% in Oceania.

In order to track the progress of countries and regions towards ending hunger, the Global Hunger Index (GHI) which was first published in 2005 was explored. The underlying data of 2023 edition of GHI was used, exploring GHI scores of 2008 and 2023 [

1]. The GHI serves as a tool for comprehensively assessing and monitoring hunger across global, regional, and national scales [

1]. GHI scores are derived from numerical values of four component indicators namely (i) undernourishment (ii) child stunting (iii) child wasting (iv) child mortality [

1]. This study presents a snapshots of the hunger prevalence and severity across various countries and regions, as reflected in the 2023 GHI. To gauge score improvement or deterioration over the specified period, the 2023 GHI scores were compared with those from 2008 for each country. The study encompasses 125 countries from five regions, including Asia and Pacific, Europe, Latin America, sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), and Middle East and North Africa (MENA).

3. Prevalence and Severity of Hunger and Food Insecurity Worldwide

This section explores the prevalence and severity of hunger and food insecurity in the world using the most recent hunger and food security data from trustworthy and reliable organizations such as Welthungerhilfe and Concern worldwide (2023 GHI), Economist Impact (GFSI, 2022), and FAO and partners [

3]. The 2023 Global Hunger Index (GHI) captured 136 countries but there were sufficient data to compute 2023 GHI scores for and rank only 125 countries. Additionally, the underlying data from 2022 Global Food Security Index (GFSI) captured 113 countries [

18]. In order to critically explore the hunger and food insecurity dynamics among countries included in these data sources, we compared each country’s previous scores and ranks in both GHI and GFSI to determine each country’s hunger and food security improvement or deterioration. Further, just like in the case of GHI, the same five regions (as mentioned above) were also considered in the 2022 GFSI for the sake of uniformity [

18].

3.1. Hunger and Food Security in Asia and Pacific

According to 2023 GHI data, China was one of the top twenty countries with scores below 5 and held a shared first position out of 125 ranked countries included in the 2023 GHI [

1]. Subsequently, China secured the top ranking in the Asia and Pacific region, despite having a GHI score of 7.1 in 2008, placing it among the countries with low hunger levels (GHI scores ≤ 9.9). From

Table 1a, Pakistan and India had the highest GHI scores of 26.6 and 28.7 respectively in 2023, signifying the least improved GHI scores (-4.5 & -6.8 respectively) in Asia and Pacific region. When we compare the 2023 GHI scores with scores in 2008, Tajikistan (ranked 62/125) was recognised as the most improved country in terms of hunger reduction (-16.2). The region did not record any countries that were further plunged into higher hunger level in 2023 (a situation where the 2023 GHI scores > 2008 GHI scores) [

1]. Although, many countries in this region are in the moderate hunger level in 2023 GHI, however, country like Pakistan witnessed heavy flooding and the arrival of El Nino in 2023 could potentially reduce grain production, resulting in higher prices and reduced availability and accessibility of essential staples in the coming future [

19].

It is worth noting that the lower the GHI scores, the better while higher GHI scores indicate deteriorating hunger level is such countries. The GHI scores are categorised as (i) low (if GHI score ≤ 9.9), (ii) moderate (if GHI score 10.0-19.9), (iii) serious (if GHI score 20.0-34.9), (iv) alarming (if the GHI score 35.0-49.9) and (v) extremely alarming (if GHI score ≥ 50.0) [

1].

However, in terms of food security environment, the underlying data of most recent 2022 GFSI was employed to explore the current state of food security of each country and region. It is worth noting that the higher the GFSI scores, the better the food security status, while the lower the GFSI scores, the worse the food security status of the 113 countries captured in the 2022 GFSI.

Table 1b revealed the food security environment of Asia and Pacific region where the GFSI scores are categorised as (i) very good (if scores 80+), (ii) Good (if scores 70.0-79.9), (iii) moderate (if score 55.0-69.9), (iv) weak (if scores 40.0-54.9) and (v) very weak (if score 0-39.9) [

18]. The score category of GHI and GFSI are in opposite direction. Higher GHI means great concerns for hunger prevalence and severity while higher GFSI scores symbolises better food security environment [

1,

18].

Japan (ranked 6/113) had the best food security environment in the 2022 GFSI (79.5) among countries in the region. This was followed by New Zealand and Australia with GFSI scores 77.8 and 75.4 respectively. Vietnam recorded the most improved score, moving from 54.5 in 2008 to 67.9 in 2022 (+13.4), and also recorded 17 places improvement in rank. In terms of change of score (2022 compared with 2012), no countries in this region recorded a reduction in the GFSI scores. Bangladesh, Lao and Pakistan recorded the three lowest scores in the region (scores 54.0, 53.1, and 52.2 respectively) [

18]. Based on the current GHI and GFSI scores in the Asia and Pacific region, it indicated that the region had performed fairly well in their efforts to reducing the prevalence of hunger and improve food security in the specified periods [

1,

18].

Table 1.

a. GHI scores of Asia and Pacific.

Table 1.

a. GHI scores of Asia and Pacific.

| Global Hunger Index (Asia and Pacific) |

|---|

| Rank/125 |

Country |

Score (2008) |

Score (2023) |

∆ |

| =1 |

China |

7.1 |

<5 |

- |

| 21 |

Uzbekistan |

14.9 |

5.0 |

-9.9 |

| 24 |

Kazakhstan |

11.0 |

5.5 |

-5.5 |

| 34 |

Azerbaijan |

15.0 |

6.9 |

-8.1 |

| 54 |

Vietnam |

20.1 |

11.4 |

-8.7 |

| =55 |

Thailand |

12.2 |

10.4 |

-1.8 |

| 56 |

Malaysia |

13.7 |

12.5 |

-1.2 |

| 60 |

Sri Lanka |

17.6 |

13.3 |

-4.3 |

| 62 |

Tajikistan |

29.9 |

13.7 |

-16.2 |

| 66 |

Philippines |

19.1 |

14.8 |

-4.3 |

| =67 |

Cambodia |

25.6 |

14.9 |

-10.7 |

| 69 |

Nepal |

29.0 |

15.0 |

-14 |

| 72 |

Myanmar |

29.7 |

16.1 |

-13.6 |

| 74 |

Laos |

30.4 |

16.3 |

-14.1 |

| 77 |

Indonesia |

28.5 |

17.6 |

-10.9 |

| 81 |

Bangladesh |

30.6 |

19.0 |

-11.6 |

| 102 |

Pakistan |

31.1 |

26.6 |

-4.5 |

| 111 |

India |

35.5 |

28.7 |

-6.8 |

| |

|

|

|

|

| Low: GHI ≤ 9.9 |

Moderate: GHI 10.0-19.9 |

Serious: GHI 20.0-34.9 |

Alarming: GHI 35.0-49.9 |

Extremely alarming: GHI ≥ 50 |

Scores are normalized 0-100. “=” denotes tie in rank. ∆ = change in score, 2023 compared with 2008.

Table 1.

b. GFSI scores of Asia and Pacific.

Table 1.

b. GFSI scores of Asia and Pacific.

| Food Security Environment (Asia and Pacific) |

|---|

| Rank/113 |

Country |

Score (2012) |

Score (2022) |

∆ |

| 6 ▲1

|

Japan |

75.4 |

79.5 |

+4.1 |

| = 14 ▲2

|

New Zealand |

72.6 |

77.8 |

+5.2 |

| 22 ↔ |

Australia |

70.8 |

75.4 |

+4.6 |

| =25 ▲24

|

China |

60.5 |

74.2 |

+3.7 |

| 28 ▼3

|

Singapore |

68.4 |

73.1 |

+4.7 |

| 32 ▲11

|

Kazakhstan |

62.7 |

72.1 |

+9.4 |

| 39 ↔ |

South Korea |

63.1 |

70.2 |

+7.1 |

| =41 ▼9

|

Malaysia |

64.2 |

69.9 |

+5.7 |

| 46 ▲17

|

Vietnam |

54.5 |

67.9 |

+13.4 |

| 63 ▼1

|

Indonesia |

55.4 |

60.2 |

+4.8 |

| =64 ▼3

|

Thailand |

55.5 |

60.1 |

+4.6 |

| 66 ▼9

|

Azerbaijan |

56.9 |

59.8 |

+2.9 |

| 67 ▲5

|

Philippines |

52.1 |

59.3 |

+7.2 |

| =68 ▼1

|

India |

53.8 |

58.9 |

+5.1 |

| 72 ▲6

|

Myanmar |

49.4 |

57.6 |

+8.2 |

| 73 ▲2

|

Uzbekistan |

50.4 |

57.5 |

+7.1 |

| 74 ▲10

|

Nepal |

45.8 |

56.9 |

+11.1 |

| 75 ▲5

|

Tajikistan |

47.1 |

56.7 |

+9.6 |

| 78 ▲11

|

Cambodia |

44.3 |

55.7 |

+11.4 |

| 79 ▼9

|

Sri Lanka |

52.9 |

55.2 |

+2.3 |

| 80 ↔ |

Bangladesh |

47.1 |

54.0 |

+6.9 |

| 81 ▲9

|

Laos |

44.1 |

53.1 |

+9.0 |

| 84 ▲10

|

Pakistan |

43.5 |

52.2 |

+8.7 |

GFSI Colour key:

| Very Good |

Good |

Moderate |

Weak |

Very weak |

| Score 80+ |

Score 70-79.9 |

Score 55-69.9 |

Score 40-54.9 |

Score 0-39.9 |

Scores are normalized 0-100, where 100 = best conditions. “=” denotes tie in rank. ∆ = change in score, 2022 compared with 2012.

▲ = Rank improved

▼= Rank deteriorated ↔ = No change in rank. Sorted by food security environment in 2022, best to worst.

3.2. Hunger and Food Security in Europe

According to the 2023 GHI, many of the countries in the European region were among the group of countries (1-20) co-ranked 1st while having their GHI scores below 5.

Table 2a presented the GHI scores of European region, indicating that five countries in this region namely, Hungary, Slovakia, Romania, Belarus, and Serbia were jointly ranked 1st. This showed a very low hunger level in the region. However, it is important to observe that most of these countries (jointly ranked first) did not attain the ranking in 2008 (except Belarus) as shown in

Table 2a but all of them were in the category of low hunger level (GHI score ≤ 9.9) [

1]. Many countries in this region (especially Northern, Southern, and Western Europe) are not captured in the 2023 GHI due to “very low” benchmark for either one or both of the PoU and child mortality data from year 2000, which are pivotal in the inclusion of countries in the index. Europe recorded the region with the lowest 2023 GHI score but it is also reported that in recent years, rising domestic food prices have diminished the affordability of food across Europe [

20].

Table 2.

a. GHI scores of Europe.

Table 2.

a. GHI scores of Europe.

| Global Hunger Index (Europe) |

|---|

| Rank/125 |

Country |

Score (2008) |

Score (2023) |

∆ |

| =1 |

Hungary |

5.6 |

<5 |

- |

| =1 |

Slovakia |

5.7 |

<5 |

- |

| =1 |

Romania |

5.8 |

<5 |

- |

| =1 |

Belarus |

<5 |

<5 |

- |

| =1 |

Serbia |

5.8 |

<5 |

- |

| 23 |

Bulgaria |

7.7 |

7.3 |

-0.4 |

| 26 |

Russia |

5.8 |

5.8 |

- |

| 44 |

Ukraine |

7.1 |

8.2 |

+1.1 |

Out of the 113 countries captured in the 2022 GFSI, twenty-six European countries were included in the index (

Table 2b). While the first five countries (Finland (83.7), Ireland (81.7), Norway (80.5), France (80.5), and Netherlands (80.1)) attained the status of “

very good” with score 80+), indicating a robust and improved food security environment (Economist Impact, 2022). Finland had the best GFSI score (83.7) in the European region and among all the 113 countries captured in 2022 GFSI [

18].

About 62 percent of countries in this region recorded “

good” GFSI score (70.0-79.9) while Bulgaria was the country with most improved score (+9.5). When comparing scores in 2022 and 2012, only Norway had its score slightly reduced (-0.4), while other countries recorded a significant improvement in their food security environment (+0.8 to +9.5). United Kingdom recorded the most improved rank (11 places up) while Spain recorded the most deteriorated rank (12 places down) in the European region in the 2022 GFSI [

18]. Even with the region’s “very good” and “good” scores, FAO et al. (2023) reported that 10.5% population in Eastern Europe encountered moderate to severe FI in 2020-2022. Ukraine recorded the lowest score (57.9) in the region in 2022, while the reason for this may not be far-fetched. However, the on-going Russia-Ukraine conflict has visibly impacted food security within Ukraine, posing challenges to the livelihoods of food producers due to lowered production levels and heightened costs associated with inputs, storage, and logistics [

3,

20].

Table 2.

b. GFSI scores of Europe.

Table 2.

b. GFSI scores of Europe.

| Food Security Environment (Europe) |

|---|

| Rank/113 |

Country |

Score (2012) |

Score (2022) |

∆ |

| 1 ▲1

|

Finland |

78.4 |

83.7 |

+5.3 |

| 2 ▲1

|

Ireland |

76.9 |

81.7 |

+4.8 |

| 3 ▼2

|

Norway |

80.9 |

80.5 |

-0.4 |

| 4 ↔ |

France |

76.8 |

80.5 |

+3.4 |

| 5 ▲7

|

Netherlands |

73.4 |

80.1 |

+6.7 |

| =7 ▼1

|

Sweden |

75.7 |

79.1 |

+3.4 |

| 9 ▲11

|

United Kingdom |

71.6 |

78.8 |

+7.2 |

| 10 ▼1

|

Portugal |

74.8 |

78.7 |

+3.9 |

| 11 ▲4

|

Switzerland |

73.2 |

78.2 |

+5.0 |

| 12 ▼2

|

Austria |

74.4 |

78.1 |

+3.7 |

| =14 ▼2

|

Denmark |

73.4 |

77.8 |

+4.4 |

| 16 ▲1

|

Czech Republic |

72.3 |

77.7 |

+5.4 |

| 17 ▼6

|

Belgium |

73.6 |

77.5 |

+3.9 |

| 19 ▼7

|

Germany |

73.4 |

77.0 |

+3.6 |

| 20 ▼12

|

Spain |

74.9 |

75.7 |

+0.8 |

| 21 ▲3

|

Poland |

68.5 |

75.5 |

+7.0 |

| 27 ▼6

|

Italy |

71.5 |

74.0 |

+2.5 |

| 29 ▲6

|

Bulgaria |

63.5 |

73.0 |

+9.5 |

| 31 ▼4

|

Greece |

67.5 |

72.2 |

+4.7 |

| 34 ▼5

|

Hungary |

66.1 |

71.4 |

+5.3 |

| 36 ▼4

|

Slovakia |

64.2 |

71.1 |

+6.9 |

| =43 ▼2

|

Russia |

63.0 |

69.1 |

+6.1 |

| 45 ▼4

|

Romania |

63.0 |

68.8 |

+5.8 |

| 55 ▼5

|

Belarus |

60.2 |

64.5 |

+4.3 |

| 61 ▲6

|

Serbia |

53.4 |

61.4 |

+8.0 |

| 71 ▼11

|

Ukraine |

55.8 |

57.9 |

+2.1 |

3.3. Hunger and Food Security in Latin America

Out of 19 Latin American countries captured in this study in the 2023 GHI, 12 (led by Chile and Uruguay) fell in the category “low hunger level (GHI score ≤ 9.9), and six of these countries (Chile, Uruguay, Costa Rica, Mexico, Argentina, and Brazil) maintained this hun-ger status since 2008 (see

Table 3a). A mere 32% of the countries in within this region rec-orded a moderate level of hunger, indicating a predominantly low to moderate level of hunger in Latin America in the 2023 GHI [

1]. However, Haiti was the only country in this region in the alarming hunger level (40.2) in 2008 score and fell to serious hunger level (31.1) in the 2023 GHI scores. Argentina (+0.9) and Venezuela (+8.5) recorded an increase in their 2023 GHI scores when compared with the 2008 scores. According to 2008 and 2023 GHI scores, Venezuela had the highest level of hunger severity (+8.5), while Haiti was the most improved country in reducing level of hunger (-9.1) in the region [

1]. Since 2015, 9 Latin American countries (Trinidad and Tobago, Bolivia, Brazil, Argentina, Costa Rica, Ecuador, Paraguay, Haiti and Venezuela) have experienced a rise in hunger [

3]. It was rereported in recent estimates that the expense of maintaining a healthy diet in Latin America and the Caribbean surpasses that of any other global regions. The devastating effects of COVID-19 and income inequality further aggravated hunger level in this region [

3].

From the underlying data of 2022 GFSI, 19 Latin American countries were captured where Costa Rica recorded the best GFSI score of 77.4. Out of 19 countries, five (Costa Rica (77.4), Chile (74.2), Uruguay (71.8), Peru (70.8), and Panama (70.0)) were in the category of “good score (70.0-79.9) [

18]. Comparing 2022 GFSI score with 2012 in this region, Bolivia recorded the most significant improvement (+12.2) while three countries (Colombia (-2.2), Venezuela (-4.9), and Haiti (-5.4)) experienced a decline in their respective GFSI scores, indicating a decline in the countries’ food security environment [

18]. Out of the 113 countries captured, Haiti was ranked 112

th (also the lowest rank in the region) and was the only country with lowest GFSI score (38.5) and falling to the category of “very weak” (0-39.9) score [

18]. Additionally, Bolivia had the most improved ranking (2012-2022), moving 19 upward while Colombia, Haiti, and Venezuela recorded the most deteriorated ranks, moving 19, 21 and 27 places downward respectively (see

Table 3b). According to FAO and partners’ recent estimates, the number of severely food insecure people in Latin America rose from 32 million in 2015 to 70.8 million in 2022. While those experiencing moderate to severe FI jumped from 144 million in 2015 to 220.8 million in 2022 [

3]. In Haiti, criminal violence and challenging economic circumstances persist in disrupting income-generating endeavours and contributing to elevated food prices [

21,

22]. The critical food deprivation experiences in Colombia and Venezuela require concerted efforts in curtailing rising inflation rates and reducing gross domestic product (GDP) growth. The persisting effects of El Nino, with reduced rainfall forecast are likely to have severe impact on food production in Venezuela [

23,

24,

25].

Table 3.

b. GFSI scores of Latin America.

Table 3.

b. GFSI scores of Latin America.

| Food Security Environment (Latin America) |

|---|

| Rank/113 |

Country |

Score (2012) |

Score (2022) |

∆ |

| 18 ▲1

|

Costa Rica |

71.7 |

77.4 |

+5.7 |

| =25 ▲1

|

Chile |

68.3 |

74.2 |

+5.9 |

| 33 ▲15

|

Uruguay |

60.9 |

71.8 |

+10.9 |

| 37 ▲2

|

Peru |

63.1 |

70.8 |

+7.7 |

| 40 ▲7

|

Panama |

61.2 |

70.0 |

+8.8 |

| =43 ▲3

|

Mexico |

61.8 |

69.1 |

+7.3 |

| 48 ▲4

|

Ecuador |

59.4 |

65.6 |

+6.2 |

| 51 ▼17

|

Brazil |

63.8 |

65.1 |

+1.3 |

| =52 ▲19

|

Bolivia |

52.8 |

65.0 |

+12.2 |

| =52 ▼1

|

Dominican Rep. |

59.5 |

65.0 |

+5.5 |

| 54 ▼19

|

Argentina |

63.5 |

64.8 |

+1.3 |

| 56 ▼3

|

El Salvador |

58.8 |

64.2 |

+5.4 |

| 58 ↔ |

Guatemala |

56.2 |

62.8 |

+6.6 |

| 60 ▲4

|

Honduras |

54.1 |

61.5 |

+7.4 |

| =64 ▼19

|

Colombia |

62.3 |

60.1 |

-2.2 |

| 70 ▼5

|

Paraguay |

54.0 |

58.6 |

+4.6 |

| 76 ↔ |

Nicaragua |

50.3 |

56.6 |

+6.3 |

| 106 ▼27

|

Venezuela |

47.5 |

42.6 |

-4.9 |

| 112 ▼21

|

Haiti |

43.9 |

38.5 |

-5.4 |

3.4. Hunger and Food Security in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA)

The only region expected to witness a significant rise in hunger (as indicated by the num-ber of undernourished individuals) is Africa, where approximately 300 million people may face hunger in 2030.

Table 4a presented the GHI scores of SSA. According to the 2023 GHI data GHI, South Africa had the best score of 13.0, while four other countries (Ghana, 13.7; Senegal, 15.0; Cameroon, 18.6, and Botswana, 19.9) recorded less than 20.0 scores, indicat-ing

moderate hunger levels [

1]. None of the countries in the SSA region were classified in the

low hunger level (GHI ≤ 9.9). Madagascar’s hunger status deepened based on the GHI scores from 2008 to 2023, with an increase of +4.4, and it remained the only country with the highest GHI score of 41.0, placing it in the

alarming hunger level [

1]. This categorisation was also shared with two other countries (Niger, 35.1; Congo Dem. Rep, 35.7). Nonethe-less, Angola achieved the most improved score (-17.0) between the 2008 and 2023 GHI scores, signalling a substantial advancement in the country’s efforts to reduce extreme hunger [

1]. Most of the countries in this region recorded a significant reduction (from Guinea, -2.2 to Angola, -17.0) in their scores but it is important to note that many of them are still grappling in the

serious to

alarming hunger (GHI score 20.0-49.9) levels. The SSA recorded the highest level (21.7%) of undernourished individuals globally [

26].

Additionally, SSA also recorded the highest child mortality rate of 7.4% globally. While the region’s child stunting rate of 31.5% was closer to that of South Asia of 31.4% [

27,

28].

Out of 113 countries captured in the 2022 GFSI edition, 28 SSA countries were included. From the 2023 GHI data, the SSA countries had 50% of the 10 most deteriorated GFSI score from 2012 to 2022 [

18].

Table 4b revealed the GFSI score of SSA in 2012 and 2022, revealing the prevalence and severity of FI levels of the region. However, 8 countries (Burkina Faso and Tanzania (38.9), Benin (39.2), Ethiopia (38.7), Chad and Sudan (35.5), Congo Dem. Rep. (33.7), and Madagascar (39.4)) were found in the most deteriorated GFSI score (0-39.9) in 2012. It is important to observe that only South Africa recorded the best (highest) GFSI scores of 57.1 and 61.7 in 2012 and 2022 respectively. It is surprising to note that no country in SSA record GFSI score categorised as

very good (score 80+) or

good (score 70-79.9) between 2012 and 2022 [

18]. Ninety-six percent (27/28) of the countries in this region fell in the cat-egory of

weak GFSI score (40-54.9) in 2022. In addition, Burkina Faso recorded the most improved rank (18 places upward) and score (+10.7) in the region between 2012 and 2022. While four countries (Zambia (-1.8), Nigeria (-0.9), Burundi (-1.4), and Sierra Leone (-1.0)) had their GFSI score further deteriorated within the two periods. Zambia recorded the most deteriorated rank (16 places downward) while Sierra Leone recorded the lowest rank (112/113) in the region in 2022 GFSI (see

Table 4b) [

18]. The sub-Saharan Africa was the only region that performed below the global average of 62.2 in 2022 GFSI with 47.0 [

5,

18].

Recent estimates revealed that about one in every four individuals in Africa encountered FI in 2022. Moderate FI increased from 45.4% in 2015 to 60.9% in 2022, while severe FI rose from 17.2% in 2015 to 24% in 2022 [

3]. Countries in SSA region like Congo Dem. Rep., Ethiopia, and Somalia are among hunger hotspots countries (others are Afghanistan, Haiti, Yemen, Pakistan, and Syria Arab Republic) of very high concern in 2023-2024 due to wors-ening critical circumstances [

22].

Table 4.

b. GFSI scores of sub-Saharan Africa.

Table 4.

b. GFSI scores of sub-Saharan Africa.

| Food Security Environment (sub-Saharan Africa) |

|---|

| Rank/113 |

Country |

Score (2012) |

Score (2022) |

∆ |

| 59 ▼3

|

South Africa |

57.1 |

61.7 |

+4.6 |

| 82 ▲13

|

Kenya |

43.0 |

53.0 |

+10.0 |

| 83 ▼10

|

Ghana |

50.5 |

52.6 |

+2.1 |

| 85 ▲3

|

Mali |

44.5 |

51.9 |

+7.4 |

| 86 ▲13

|

Senegal |

42.5 |

51.2 |

+8.7 |

| 87 ▼10

|

Botswana |

50.2 |

51.1 |

+0.9 |

| 88 ▼5

|

Rwanda |

45.9 |

50.6 |

+4.7 |

| 89 ▲18

|

Burkina Faso |

38.9 |

49.6 |

+10.7 |

| 90 ▲17

|

Tanzania |

38.9 |

49.1 |

+10.2 |

| =91 ▲15

|

Benin |

39.2 |

48.1 |

+8.9 |

| =91 ▼6

|

Malawi |

45.5 |

48.1 |

+2.6 |

| 93 ▲10

|

Uganda |

41.0 |

47.7 |

+6.7 |

| 94 ▼2

|

Mozambique |

43.8 |

47.3 |

+3.5 |

| 95 ▼8

|

Cote d’Ivoire |

45.0 |

46.5 |

+1.5 |

| 96 ▼3

|

Cameroon |

43.6 |

46.4 |

+2.8 |

| 97 ▲3

|

Niger |

42.1 |

46.3 |

+4.2 |

| 98 ↔ |

Togo |

42.7 |

46.2 |

+3.5 |

| 99 ▲11

|

Guinea |

50.5 |

45.1 |

+9.3 |

| 100 ▲9

|

Ethiopia |

38.7 |

44.5 |

+5.8 |

| 101 ▼5

|

Angola |

42.9 |

43.7 |

+0.8 |

| 102 ▼16

|

Zambia |

45.3 |

43.5 |

-1.8 |

| 103 ▲8

|

Chad |

35.5 |

43.2 |

+7.7 |

| 104 ▲9

|

Congo (Dem. Rep) |

33.7 |

43.0 |

+9.3 |

| 105 ▲6

|

Sudan |

35.5 |

42.8 |

+7.3 |

| 107 ▼11

|

Nigeria |

42.9 |

42.0 |

-0.9 |

| =108▼7

|

Burundi |

42.0 |

40.6 |

-1.4 |

| =108▼3 |

Madagascar |

39.4 |

40.6 |

+1.2 |

| 110 ▼8

|

Sierra Lone |

41.5 |

40.5 |

-1.0 |

3.5. Hunger and Food Security in Middle East and North Africa (MENA)

Out of 125 countries included in the 2023 GHI scores, 10 belonging to the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region are included in this study (see

Table 5a). Seventy percent (7/10) of the countries were categorised in the

low hunger level (GHI score ≤ 9.9), with three countries (United Arab Emirates, Turkey, and Kuwait) ranked among the 20 countries jointly ranked 1

st (1/125) with below 5 GHI scores [

1]. However, Syria and Yemen were the two countries that witnessed a deterioration in their GHI score (Syria, +9.9; Yemen, +2.2) between 2008 and 2023. Yemen is the only country found in the

alarming hunger level (GHI score 35.0-9.9) in this region in 2008 and 2023 (

Table 5a). It is important to observe that Yemen and Syria are among the 8 countries considered as “hunger hotspots of significant concern” [

22]. All of these hotspots feature a substantial population grappling with or pro-jected to encounter severe levels of FI, along with exacerbating factors that are anticipated to heighten life-threatening circumstances in the early months of 2024 [

22]. Yemen ranked as the third-highest in the 2023 GHI score (39.9), recording high level of child undernutri-tion (stunting, 48.7%; wasting 14.4%) in 2023. The enduring conflict in Yemen, now in its ninth year, has been severely damaging to the economy, and the nation’s children have endured substantial suffering [

29].

Algeria recorded the most significant reduction in hunger level (-4.3) in the region, moving from GHI score of 11.1 in 2008 to 6.8 (low) hunger level in 2023 [

1]. All the North African countries (Tunisia, Algeria, and Morocco) except Egypt are in the

low hunger level. Although, North African countries are relatively enjoy low to

moderate hunger level when compared with SSA where most of the countries belonged to

serious and a

larming hunger levels [

1].

The 2022 GFSI data showed that 87% of the countries in this region recorded a moderate GFSI score (55-69.9) in 2022 [

18]. United Arab Emirates (UAE) had the best GHI score (75.2) while Oman emerged as the country with most improved rank (20 places upward) and score (+13.8) in 2022. Syria recorded the worst GFSI score (36.3) and the most deteriorated rank (31 places downward) from 2012 to 2022 from the 15 countries reported in this region. In addition, Kuwait and Syria remained the only two countries that had their GFSI scores declined from 65.7 to 65.2 (-0.5), and from 46.8 to 36.3 (-10.5) in 2012-2022 respectively (see

Table 5b) [

18]. Syria recorded the worst GFSI score in the 2022 ranking with 113

th position (113/113). According to 2023 Global Report on Food Crises (GRFC), the ongoing conflict in Yemen and Syria, along with escalating economic crises throughout the region, resulted in heightened levels of severe FI in 2022 [

2]. The reported also projected that about 18% of the analysed population (38 countries/territories) will face high levels of severe FI in 2023 [

2]. In 2022, approximately 34.1 million individuals encountered elevated levels of severe FI in eight countries within the MENA region, marking an increase from 31.9 million in 2021 [

2].

Table 5.

b. GFSI scores of Middle East and North Africa.

Table 5.

b. GFSI scores of Middle East and North Africa.

| Food Security Environment (Middle East and North Africa) |

|---|

| Rank/113 |

Country |

Score (2012) |

Score (2022) |

∆ |

| 23 ▲15

|

United Arab Emirates |

63.2 |

75.2 |

+12.0 |

| 24 ▲4

|

Israel |

67.0 |

74.8 |

+7.8 |

| 30 ▼7

|

Qatar |

69.9 |

72.4 |

+2.5 |

| 35 ▲20

|

Oman |

57.4 |

71.2 |

+13.8 |

| 38 ▼7

|

Bahrain |

64.7 |

70.3 |

+5.6 |

| =41 ▲13

|

Saudi Arabia |

58.1 |

69.9 |

+11.8 |

| 47 ▼10

|

Jordan |

63.3 |

66.2 |

+2.9 |

| 49 ▼5

|

Turkey |

62.4 |

65.3 |

+2.9 |

| 50 ▼20

|

Kuwait |

65.7 |

65.2 |

-0.5 |

| 57 ▲9

|

Morocco |

53.9 |

63.0 |

+9.1 |

| 62 ▼3

|

Tunisia |

56.0 |

60.3 |

+4.3 |

| =68 ▲5

|

Algeria |

50.5 |

58.9 |

+8.4 |

| 77 ▼10

|

Egypt |

53.8 |

56.0 |

+2.2 |

| 111 ▼7

|

Yemen |

40.0 |

40.1 |

+0.1 |

| 113 ▼31

|

Syria |

46.8 |

36.3 |

-10.5 |

From the underlying data of the 2022 GFSI revealed the identification of 10 countries with most improved scores, alongside the identification of another 10 countries with the most deteriorated scores in the 2022 edition [

18].

Table 6a revealed the top 10 countries with most improved GFSI score while

Table 6b indicated countries with most deteriorated GFSI scores from 2012 to 2022 [

18]. Oman recorded the most improved GFSI score (+13.8) while Burkina Faso (the only SSA in this category) recorded the least improved score (+10.7). In addition, 50% of the countries (

Table 6a) fall in the category of

moderate score (55-69.9), 40% belonged to the

good score while only Burkina Faso belonged to the

weak score. From coun-tries with most deteriorated food security environment score, Syria recorded the highest score (-10.5) and belonged to the

very weak GFSI score (36.3) along with Haiti (38.5) [

18]. Further, four countries in SSA (Zambia, -1.8; Burundi, -1.4; Sierra Leone, -1.0; and Nigeria, -0.9) region were part of this category (most deteriorated GFSI) while Norway was the only European country with the least score (-0.4), though the country still belonged to the

very good GFSI score (80.9-80.5) from 2012 to 2022. It worth noting that most of the countries in this category (7/10) had

weak GFSI score [

18].

Table 6.

a. Most improved GFSI score 2022 vs 2012.

Table 6.

a. Most improved GFSI score 2022 vs 2012.

2022

Rank |

Country |

2012 Score |

2022 Score |

∆ |

| 35 |

Oman |

57.4 |

71.2 |

+13.8 |

| =25 |

China |

60.5 |

74.2 |

+13.7 |

| 46 |

Vietnam |

54.5 |

67.9 |

+13.4 |

| =52 |

Bolivia |

52.8 |

65.0 |

+12.2 |

| 23 |

United Arab Emirates |

63.2 |

75.2 |

+12.0 |

| =41 |

Saudi Arabia |

58.1 |

69.9 |

+11.8 |

| 78 |

Cambodia |

44.3 |

55.7 |

+11.4 |

| 74 |

Nepal |

45.8 |

56.9 |

+11.1 |

| 33 |

Uruguay |

60.9 |

71.8 |

+10.9 |

| 89 |

Burkina Faso |

38.9 |

49.6 |

+10.7 |

Table 6.

b. Most deteriorated GFSI score 2022 vs 2012.

Table 6.

b. Most deteriorated GFSI score 2022 vs 2012.

2022

Rank |

Country |

2012 Score |

2022 Score |

∆ |

| 113 |

Syria |

46.8 |

36.3 |

-10.5 |

| 112 |

Haiti |

43.9 |

38.5 |

-5.4 |

| 106 |

Venezuela |

47.5 |

42.6 |

-4.9 |

| =64 |

Colombia |

62.3 |

60.1 |

-2.2 |

| 102 |

Zambia |

45.3 |

43.5 |

-1.8 |

| 108 |

Burundi |

42.0 |

40.6 |

-1.4 |

| 110 |

Sierra Leone |

41.5 |

40.5 |

-1.0 |

| 107 |

Nigeria |

42.9 |

42.0 |

-0.9 |

| 50 |

Kuwait |

65.7 |

65.2 |

-0.5 |

| 3 |

Norway |

80.9 |

80.5 |

-0.4 |

4. Exploring Hunger Severity where Hunger Indicators Reached their Peak

As mentioned above, the GHI scores are computed based on the values of 4 component indicators such as prevalence of undernourishment (PoU), child stunting, child wasting, and child mortality [

1]. The 2023 GHI scores indicated that from 2015 onwards, the global advancement in addressing hunger had shown minimal change, with a reduction of less than one percentage point, decreasing from 19.1% to 18.3%. Even though, the 2030 global goals aim for zero hunger by 2030, the 2023 GHI scores and current realities indicate that 58 countries are unlikely to achieve low hunger levels, casting doubt on the feasibility of achieving of zero hunger by 2030 [

1]. It is important to highlight that several countries, including Bangladesh, Chad, Djibouti, Lao PDR, Mozambique, Nepal, and Timor-Leste, have achieved remarkable progress in reducing hunger since 2015. However, six countries - Niger, Central African Republic (CAR), Madagascar, Congo Dem. Rep., Lesotho, and Yemen – were found to have GHI scores in the alarming threshold. Additionally, three other countries - Burundi, Somalia, and South Sudan – are provisionally designated as

alarming [

1].

Utilizing the hunger indicators for the 2023 GHI scores, it was found that CAR had the highest score of 42.3 and PoU of 48.7% during 2020-2022, signalling that approximately half of the country’s population is experiencing undernourishment. Additionally, 40% of children in the Central African Republic (CAR) experience stunted growth, and 5.3% suffer from wasting [

1]. The Central African Republic faces severe levels of hunger, exacerbated by conflicts, abject poverty, forced migration, and an underutilized workforce [

1,

30,

31].

Further, Madagascar reported the highest PoU at 51%, with 38.9% of children experiencing stunted growth and 7.2% suffering from wasting. The country also endured the devastat-ing impact of climate change, pushing it perilously close to widespread famine in recent times. Fundamental structural deficiencies further deepens Madagascar’s fragility [

32,

33,

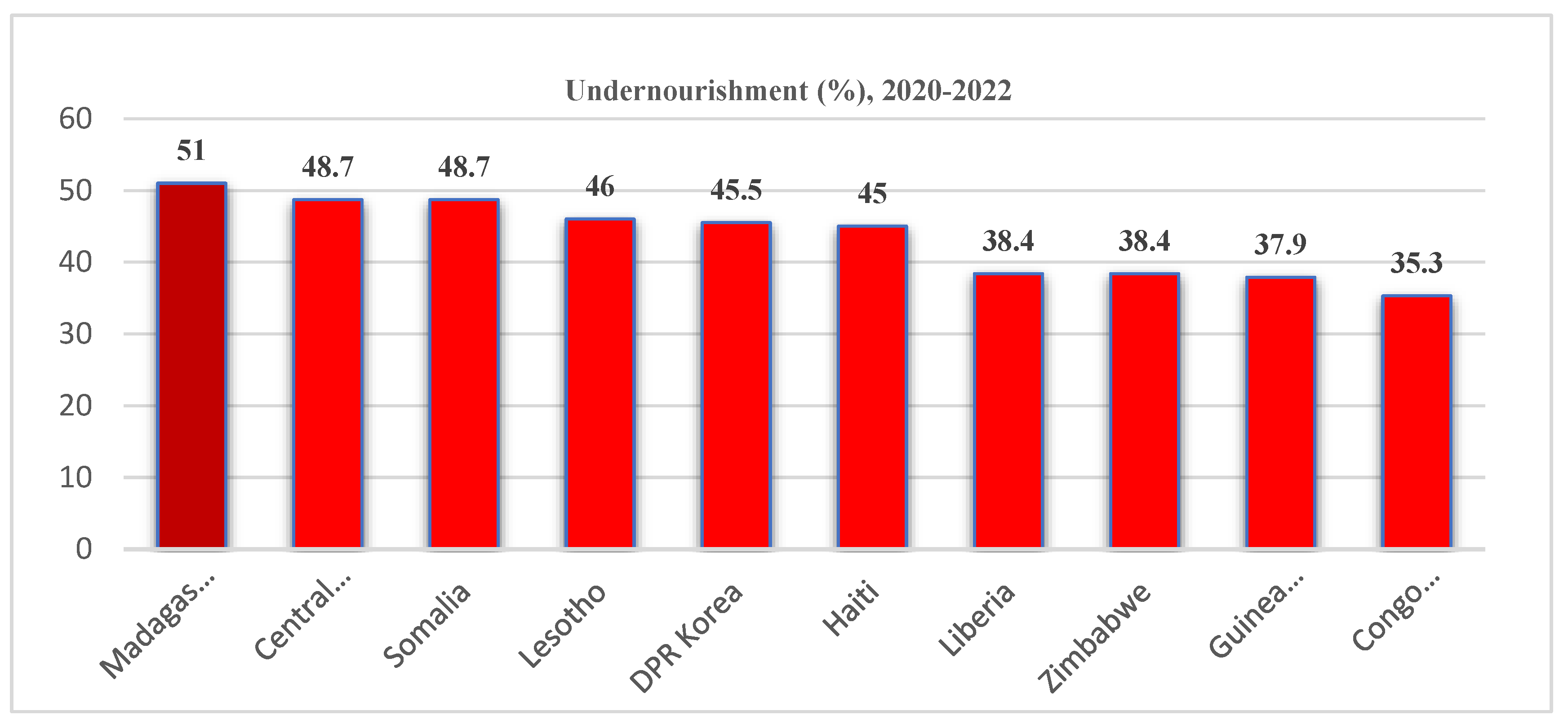

34]. In the period 2020-2022, eighty percent of the top 10 countries with the highest percentages of undernourishment (ranging from 51.0% to 35.3%) are located in sub-Saharan Africa (see

Figure 1a), highlighting the region’s considerable responsibility for addressing hunger on a global scale [

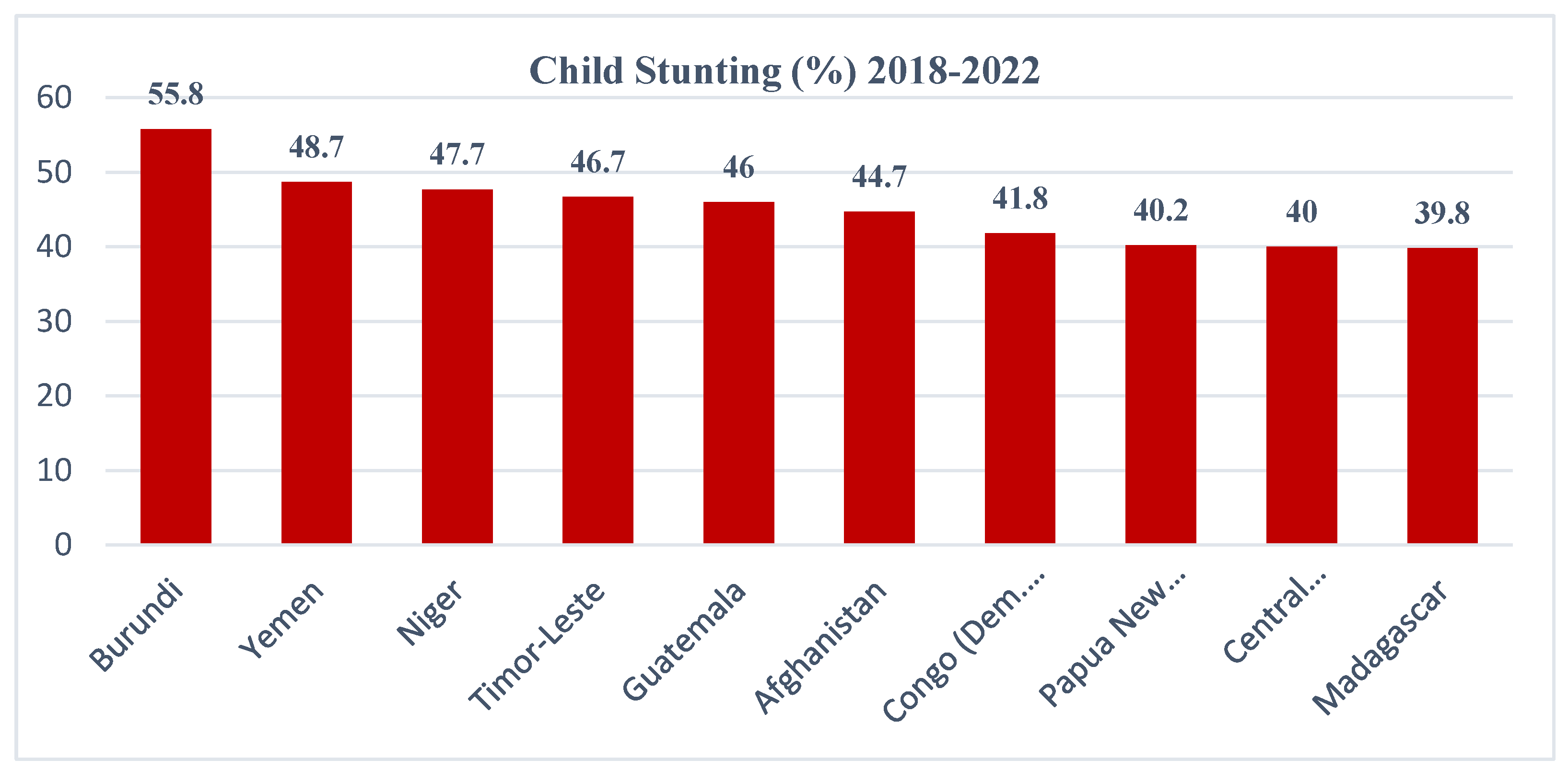

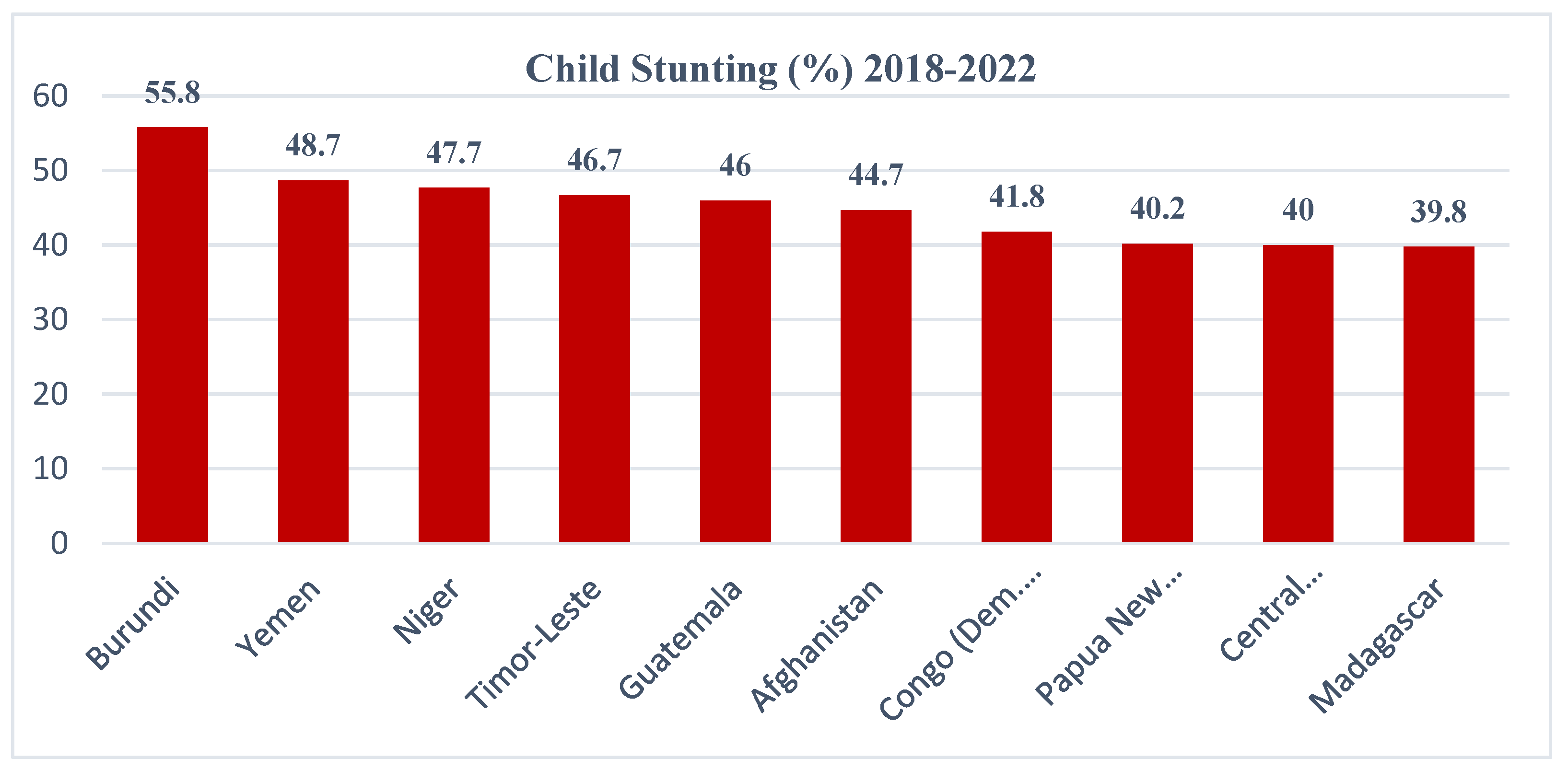

1]. In the period of 2018-2022, half of the top 10 countries with the most significant prevalence of child stunting were located in sub-Saharan Africa (see

Figure 1b).

Figure 1.

a. Top 10 countries with highest burden of undernourishment during 2020 to 2022. Source: Authors’ compilation using underlying data from 2023 GHI scores [

1].

Figure 1.

a. Top 10 countries with highest burden of undernourishment during 2020 to 2022. Source: Authors’ compilation using underlying data from 2023 GHI scores [

1].

Figure 1.

b. Top 10 countries with highest burden of child stunting during 2018-2022. Source: Authors’ compilation using underlying data from 2023 GHI scores [

1].

Figure 1.

b. Top 10 countries with highest burden of child stunting during 2018-2022. Source: Authors’ compilation using underlying data from 2023 GHI scores [

1].

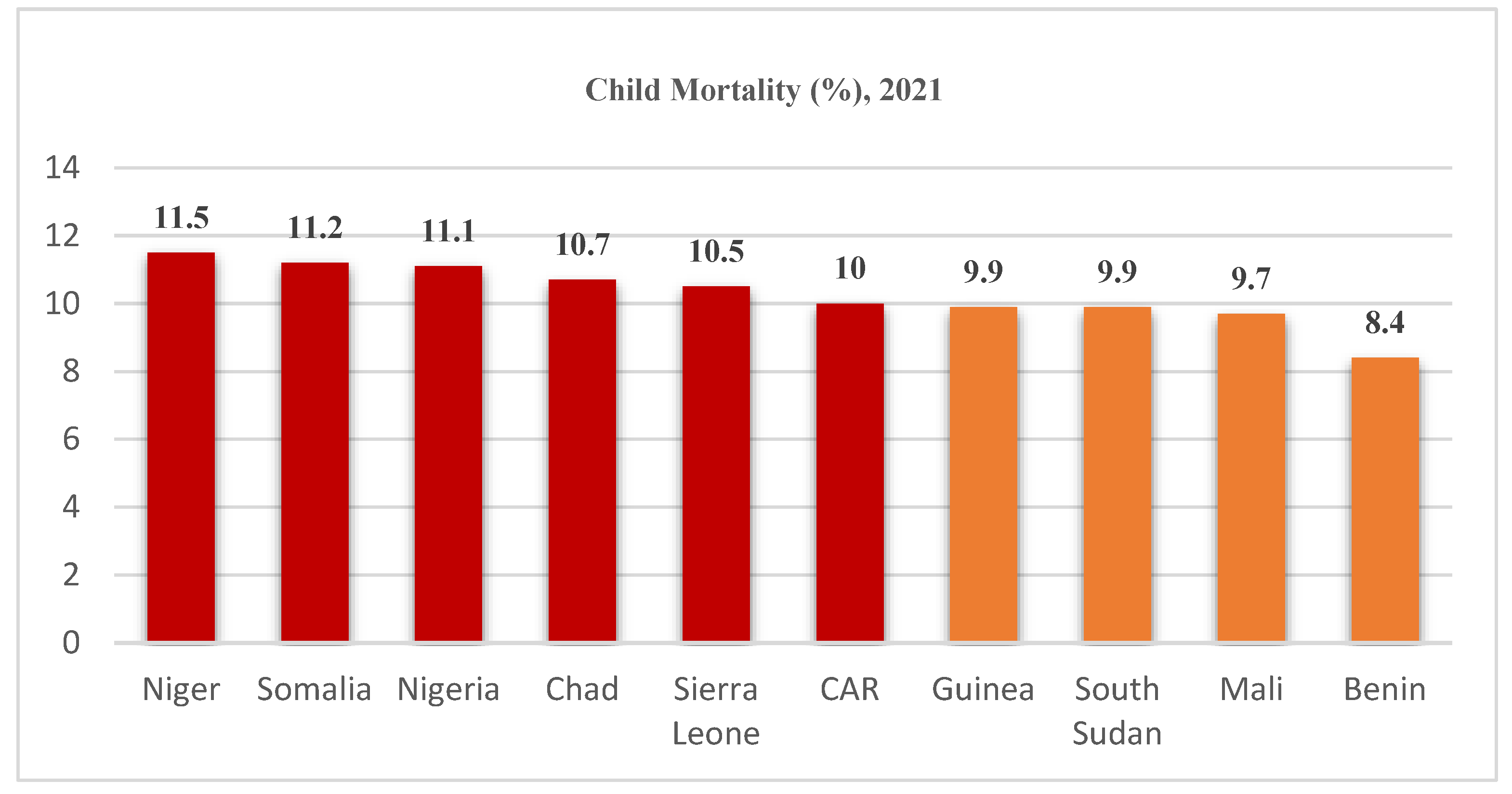

The third indicator utilised to calculate the 2023 GHI scores, which focuses on child wast-ing, revealed that 5 out of the 10 countries (Niger, Mali, Mauritius, Sudan, and Mauritania) with the greatest prevalence of child wasting were located in SSA [

1]. Though India had the highest child wasting of 18.7% globally, Sudan had the highest prevalence of child wasting (13.7%) in SSA from 2018 to 2022 [

18]. None of the countries in Europe were among those with the highest prevalence of wasting from 2018 to 2022 (see

Figure 1c). Additionally, the prevalence of child mortality is the fourth indicator employed in calcu-lating the 2023 GHI scores. It was surprising to observe that all of the top 10 countries with the highest burden of child mortality in 2021 were located in sub-Saharan Africa. Niger exhibited the highest child mortality rate at 11.5% whereas Benin demonstrated the lowest prevalence of child mortality, standing at 8.4% within this category (see

Figure 1d) [

1]. It is important to highlight that South Sudan has fallen in the

alarming hunger level, reporting a child mortality of approximately 10% in the region. Nearly one-fifth South Sudan’s population experienced undernourishment from 2020 to 2022 [

2]. Further, Somalia exhibited the second-highest rate of child mortality at 11.2% in 2021, along with a PoU of 48.7% from 2020 to 2022. These challenges were exacerbated by rising global prices, persistent insecu-rity, and the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic [

2].

Figure 1.

c. Top 10 countries with highest burden of child wasting during 2018-2022. Source: Authors’ compilation using underlying data from 2023 GHI scores [

1].

Figure 1.

c. Top 10 countries with highest burden of child wasting during 2018-2022. Source: Authors’ compilation using underlying data from 2023 GHI scores [

1].

Figure 1.

d. Top 10 countries with highest burden of child mortality during 2018-2022. Source: Authors’ compilation using underlying data from 2023 GHI scores [

1]

Figure 1.

d. Top 10 countries with highest burden of child mortality during 2018-2022. Source: Authors’ compilation using underlying data from 2023 GHI scores [

1]

5. Sub-Saharan Africa Suffers the Highest Burden of Food Insecurity Globally

Based on the foundational data from 2022 GFSI, seven out of top 10 countries with the highest GFSI scores were from the European region, while two originated from North America (Canada and United States), and one (Japan) emerged from the Asia and Pacific region. It is unexpected to observe the absence of African countries in this category (see

Table 7a) [

18]. Particularly in Africa, especially the SSA, the proportion of the population facing FI and unable to access high-quality diets ranks among the highest globally. As noted above, the percentage of the African population facing severe FI increased from 17.2% in 2015 to 24.0 %, surpassing the global severe FI rate of 11.8% and that of any other region worldwide (

Figure 2) [

18]. In addition, moderate FI in Africa rose from 45.4% in 2015 to 60.9% in 2022, surpassing the global moderate FI rate of 29.6% in 2022 and that of any other region worldwide in the same period [

3]. Although, Asia is the largest region, it is important to emphasize that the worldwide prevalence of severe FI in 2022 was reduced (9.7%), in contrast to Africa, where severe FI reached 24% in the same year [

3].

Additionally, among the bottom 10 countries with the least favourable GFSI scores in 2022 (as indicated in

Table 7b), 60% were from SSA, 20% from MENA region (Yemen and Syria), and 20% were from Latin America (Haiti and Venezuela). In the category of the SSA’s 2022 GFSI scores, the range spanned from 40.5 (Sierra Leone) to 43.0 (Congo Dem. Rep), indi-cating a

weak score. Meanwhile, Syria (36.3) and Haiti (38.5) fell within the group of

very weak 2022 GFSI scores [

18]. In

Table 7a, United States recorded the highest GFSI score im-provement (+7.2) while Norway had a slightly deteriorated score from 2012 to 2022. In

Table 7b, Congo Dem. Rep. recorded the largest GFSI score improvement of +9.3, whereas Syria recorded the lowest GFSI score and rank (36.3 and 113/113) in 2022, and also the most significant decline in score (-10.5) within this category [

18].

Table 7.

a. Top 10 most favourable GFSI scores in 2022.

Table 7.

a. Top 10 most favourable GFSI scores in 2022.

2022

Rank |

∆ |

Country |

2022 Score |

∆ |

| 1 |

▲1

|

Finland |

83.7 |

+5.3 |

| 2 |

▲1

|

Ireland |

81.7 |

+4.8 |

| 3 |

▼2

|

Norway |

80.5 |

-0.4 |

| 4 |

↔ |

France |

80.2 |

+3.4 |

| 5 |

▲7

|

Netherlands |

80.1 |

+6.7 |

| 6 |

▲1

|

Japan |

79.5 |

+.4.1 |

| =7 |

▲11

|

Canada |

79.1 |

+7.0 |

| =7 |

▼1

|

Sweden |

79.1 |

+3.4 |

| 9 |

▲11

|

United States |

78.8 |

+7.2 |

| 10 |

▼1

|

Portugal |

78.7 |

+3.9 |

Table 7.

b. Bottom 10 least favourable GFSI in 2022.

Table 7.

b. Bottom 10 least favourable GFSI in 2022.

2022

Rank |

∆ |

Country |

2022 Score |

∆ |

| 113 |

▼31

|

Syria |

36.3 |

-10.5 |

| 112 |

▼21

|

Haiti |

38.5 |

-5.4 |

| 111 |

▼7

|

Yemen |

40.1 |

+0.1 |

| 110 |

▼8

|

Sierra Leone |

40.5 |

-1.0 |

| =108 |

▼7

|

Burundi |

40.6 |

-1.4 |

| =108 |

▼3

|

Madagascar |

40.6 |

+1.2 |

| 107 |

▼11

|

Nigeria |

42.0 |

-0.9 |

| 106 |

▼27

|

Venezuela |

42.6 |

-4.9 |

| 105 |

▲6

|

Sudan |

42.8 |

+7.3 |

| 104 |

▲9

|

Congo (Dem. Rep) |

43.0 |

+9.3 |

Additionally,

Figure 2 showed moderate and severe FI levels in the world and other regions from 2015 to 2022. Moderate FI in Africa increased from 28.2% in 2015 to 36.9% in 2022, while severe FI rose from 17.2% in 2015 to 24% in 2022 [

3]. The unprecedented rise in FI in Africa was reported as the highest globally. Also, the prevalence of severe FI in the Latin America and the Caribbean is the second-highest globally, increasing from 7.3% in 2015 to 12.6% in 2022 (FAO et al. 2023). However, North America and Europe recorded moderate or severe FI levels of less than 10% from 2015 to 2022 but it is worth noting that moderate FI increased slightly in the region, from 6.2% in 2021 to 6.6% in 2022 [

3]. While global moderate or severe FI remained the same (29.6%) between 2021 and 2022, Africa witnessed a worsening FI levels during 2015 to 2022 [

3].

6. Limitations of the Study

In this investigation, the latest global hunger and food security dynamics was examined, drawing on data from trustworthy and reliable organisations. However, one limitation of this study is the incomplete representation of all countries across the indices and classi-fications utilised. Additionally, the current 2023 GHI and 2022 GFSI reports cannot be di-rectly compared with previous editions of the GHI and GFSI.

7. Conclusions

The world is currently facing intersecting crises that are intensifying social and economic disparities and undoing advancements made against hunger. Global hunger showed little change from 2021 to 2022, yet it continues to significantly surpass levels witnessed before the COVID-19 pandemic. In nearly all of the 113 countries in the 2022 GFSI, instances of food insecurity were documented. While there were modest improvement in GHI and GFSI scores, particularly in developed countries, a majority of countries in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) demonstrated a deterioration in their GFSI scores, accompanied by significant increases in their GHI scores. The current study provides evidence at both country and regional levels regarding recent changes in hunger and food security dynamics, along with offering the subsequent policy recommendations: (i) centre the universal right to food at the core of the transformation of food systems (ii) allocate resources to develop abilities of young individuals in the transformation of food systems (iii) allocate resources towards creating sustainable, fair, and adaptable food systems that provide meaningful and ap-pealing livelihood opportunities for young individuals.

Author Contributions

O.A.O: The conceptualization. O.A.O: Curation. O.A.O: Formal analysis. O.A.O: Investigation. O.A.O: Methodology. O.A.O: Formal analysis. O.A.O: writing - original draft preparation. O.A.O: writing-review, editing, and visualization. Author has read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- von Grebmer, K.; Bernstein, J.; Geza, W.; Ndlovu, M.; Wiemers, M.; Reiner, L.; Bachmeier, M.; Hanano, A.; Ni Cheilleachair, R.; Sheehan, T.; Foley, C.; Gitter, S.; Larocque, G.; Fritschel, H. 2023 Global Hunger Index: The Power of Youth in Shaping Food Systems. Bonn: Welthungerhilfe (WHH); Dublin: Concern Worldwide.

- FSIN, Global Network against Food Crises. 2023 Global Report on Food Crises: Joint Analysis for Better Decision; Global Network against Food Crises: Rome, Italy, 2023.

- FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP, WHO. 2023. The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2023. Urbanization, agrifood systems transformation and healthy diets across the rural–urban continuum. Rome.

- Otekunrin, O.A.; Mukaila, R.; Otekunrin, O.A. Investigating and Quantifying Food Insecurity in Nigeria: A Systematic Review. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1873. [Google Scholar]

- Otekunrin, O.A.; Ayinde, I.A.; Sanusi, R.A.; Onabanjo, O.O. Dietary diversity, nutritional status, and agricultural commercialization: Evidence from rural farm households. Dialog. Health 2, 100121.

- Otekunrin, O.A. Countdown to the global goals: A Bibliometric Analysis of Research Trends on SDG 2 – Zero Hunger. Curr Res Nutr Food Sci Jour, 2023, 1338-1362.

- Action Against Hunger. What is Hunger? 2023. https://www.actionagainsthunger.org/the-hunger-crisis/world-hunger-facts/what-is-hunger/ (accessed on 17 August 2023). United Nations. Sustainable Development Goal 2, 2017. https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/sdg2.

- United Nations. Sustainable Development Goal 2, 2017. https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/sdg2.

- Otekunrin, O.A.; Otekunrin, O.A.; Momoh, S.; Ayinde, I.A. How far has Africa gone in achieving the Zero Hunger Target? Evidence from Nigeria. Glob Food Secur, 2019, 22: 1-12.

- Otekunrin, O.A.; Otekunrin, O.A.; Sawicka, B., Ayinde, I. A. Three decades of fighting against hunger in Africa: Progress, challenges and opportunities. World Nutrition, 2020a, 11(3): 86-111.

- Fanzo, J.; Haddad, L.; Schneider, K.R.; Bene, C. Viewpoint: Rigorous monitoring is necessary to guide food system transformation in the countdown to the 2030 global goals. Food Policy, 2021, 102, 102163. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. Rome declaration on the world food security and world food summit plan of action. In Proceedings of the World Food Summit 1996, Rome, Italy, 13–17 November 1996.

- Piperata, B.A.; Scaggs, S.A.; Dufour, D.L.; Adams, I.K. Measuring food insecurity: An introduction to tools for human biologists and ecologists. Am. J. Hum. Biol. 2023, 35, e23821. [Google Scholar]

- Otekunrin, O. A.; Otekunrin, O. A.; Fasina, F. O.; Omotayo, A. O., Akram, A. Assessing the Zero Hunger Target Readiness in Africa in the Face of COVID-19 Pandemic. Caraka Tani: J Sustain Agric, 2020b, 35, 213-227.

- Atukunda, P.; Eide, W.B.; Kardel, K.R.; Iversen, P.O. et al. Unlocking the potential for achievement of the UN Sustainable Development Goal 2 – ‘Zero Hunger’ – in Africa: Targets, strategies, synergies and challenges. Food Nutr Res, 2021, 65: 7686.

- Otekunrin, O.A.; Otekunrin, O.A. Healthy and Sustainable Diets: Implications for Achieving SDG2. W. Leal ilho et al. (eds), Zero Hunger, 2021, Encyclopedia of the UN Sustainable Development Goals, 1-21.

- Blesh, J.; Hoey, L.; Jones, A.D.; Friedmann, H. Development pathways toward “zero hunger”. World Dev, 2019, 118, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Economist Impact. Global Food Security Index 2022. 2022. Available online: https://impact.economist.com/sustainability/project/food-security-index/ (accessed on 11 December 2023).

- Mamun, A.; Glauber. J. 2023. “Rice Markets in South and Southeast Asia Face Stresses from El Niño, Export Restrictions.” IFPRI Blog (International Food Policy Research Institute), 2023. https://www.ifpri.org/blog/rice-markets-south-and-southeast-asia-face-stresses-elni%C3%B1o-export-restrictions.

- Jungbluth, F.; Zorya, S. “Ensuring Food Security in Europe and Central Asia, Now and in the Future.” World Bank Blogs, 2023. February 3. https://blogs.worldbank.org/europeandcentralasia/ensuring-food-security-europe-and-central-asia-now-and-future.

- Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET). Latin America and the Caribbean – Food Security Outlook, 2023 (October 2023 – May 2024).

- WFP, FAO. Hunger Hotspots. FAO–WFP early warnings on acute food insecurity: November 2023 to April 2024 Outlook. Rome.

- OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development). OECD Economic Outlook, Volume 2023 Issue 1. June 2023. OECD Publishing, Paris.

- Instituto de Hidrología, Meteorología y Estudios Ambientales (IDEAM). 2023. Colombia. In: IDEAM. [Cited 19 September 2023].

- CPC (Climate Prediction Center). South America. In: NMME Probabilistic Forecasts for International Regions, 2023.

- FAO. “Data: Suite of Food Security Indicators.” 2023. Accessed July 12, 2023. www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/FS.

- UN IGME (United Nations Inter-agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation). Levels and Trends in Child Mortality: Report 2022. New York: UNICEF.

- UNICEF (United Nations Children’s Fund). Undernourished and Overlooked: A Global Nutrition Crisis in Adolescent Girls and Women. 2023a. New York.

- UNICEF. 2023b. “Yemen Crisis.” Updated May 22. https://www.unicef.org/emergencies/yemen-crisis.

- United Nations. “UN Needs $68.4 Million to Help Central African Republic Where 2.2 Million Are Acutely Food Insecure, 2022” Press release, July 5. https://news.un.org/en/story/2022/07/1121952.

- WFP, ICASEES (Institut Centrafricain des Statistiques, des Etudes Economiques et Sociales), and République Centrafricaine, Cluster Sécurité Alimentaire. 2022. Résultats Préliminaires: ENSA 2021 (Enquête Nationale sur la Sécurité Alimentaire). https://reliefweb.int/report/central-african-republic/r-sultats-pr-liminaires-ensa-2021-enqu-te-nationale-de-s-curit.

- Baker, A. “Climate, Not Conflict. Madagascar’s Famine Is the First in Modern History to Be Solely Caused by Global Warming.” Time, 2021, July 20. https://time.com/6081919/famine-climate-change-madagascar/.

- UN News. “In Madagascar, Pockets of Famine As Risks Grow for Children, Warns WFP, 2021. November 2. https://news.un.org/en/story/2021/11/1104652.

- Rice, S. “Madagascar’s Famine Is More Than Climate Change.” Georgetown Journal of International Affairs, 2022. January 24. https://gjia.georgetown.edu/2022/01/24/madagascars-famineis-more-than-climate-change/.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).