Introduction

As universities around the world are incorporating the additional role of commercialising knowledge in their local and regional economies (Wong et al., 2007), higher education institutions in European countries are facing the paradox of global competition and regional development (Goddard, 2017). Some scholars have argued that research excellence inevitably equates to the ability of a regional economy to generate innovation (Goddard, 2017). Kaltenecker and Majarro (2019) proposed importing international environments into the curriculum setting (i.e. attracting students, faculty, and staff from around the world), sending students abroad to off-site campuses, and creating multiple-site institutions with campuses located around the world. Hence, international exchange cooperation in higher education has become an alternative means for regional universities, whose expertise is still in development, to pool their own expertise and perspectives as a contribution to international exchange innovation (Bertelsen, 2018).

The Erasmus+ programme’s Erasmus Mundus Joint Master Degree (EMJMD) is an interesting example of international innovation. Erasmus is a programme established in 1987 by the European Union (EU) to promote cooperation among organisations and institutions (i.e. higher education institutions) and contribute to the extension of the worldwide labour market (Mizikaci & Arslan, 2019). The EMJMD is one part of the Erasmus programme, which is jointly delivered by different universities in Europe. Since 2009, the EMJMD has aimed at fostering the academic excellence and worldwide cooperation of the participating higher institutions to cultivate innovative skills, knowledge, and competent graduates (European Commission, n.d.). Scholars have discussed the effectiveness of Erasmus+ in promoting international student exchange to facilitate innovation education in international contexts (Breznik & Skrbinjek, 2020). However, little has been done to evaluate differences between European Union (EU) and non-European Union (non-EU) students’ perceptions of the international exchange programme’s design. In response to scholars’ suggestions regarding the need to investigate international and local students’ engagement (Lee et al., 2019), this paper uses the triple helix model to investigate the Food Innovation and Product Design Programme (FIPDes), an EMJMD coordinated by AgroParisTech in France, with the participation of Technological University Dublin (DTU) in Ireland, Lund University (LU) in Sweden, and University of Naples Federico II (UNINA) in Italy. Overall, the study shows how differently or similarly non-EU students and EU students perceive international exchange learning opportunities in food innovation.

Background: FIPDes

Established in 2011, FIPDes has created a multiple-site institution with campuses located in a number of European countries, and staff contribute their expertise to offer relevant courses. AgroParisTech and DIT focus on courses that facilitate the generation of new knowledge in agriculture, biochemistry and technical design. Lund University in Sweden focuses on courses in logistics and packaging technology. The students examined in this study first gained a holistic understanding of food science and technology at AgroParisTech in their first year of study. They then spent another semester at DIT to enrich their knowledge of culinary innovation, business creation, and marketing. In the second year of study, students chose to study different specialist areas in the participating universities. (i.e. Healthy Food Design at UNINA, Food Design and Engineering at AgroParisTech, and Food Packaging Design & Logistics at LU), and they completed R&D innovation coursework based on the tasks given by the industry partners in the host countries.

The FIPDes programme of the four universities can be placed in the triple helix model, as it involves initiating innovative and cooperative connections with universities and companies from EU and non-EU countries. The industry–host institution collaboration was the most significant of all the types of collaboration (76.5%), followed by higher education institution–host institution partnerships (22.5%). The host universities utilised their connections with local firms the most (40.2%), exposing students to the food innovation industry. They also partnered with companies from non-EU countries (i.e. South Korea and China) to enhance students’ global awareness regarding the food innovation industry around the world. There are two reasons for choosing FIPDes as the analytical basis. First, similar to other international exchange programmes, FIPDes has attempted to create a curriculum of innovation by engaging students with markets by producing R&D innovation research of global quality (Kedia and Englis, 2011). Therefore, how this European regional programme fostered academic excellence, worldwide cooperation and R&D innovation was worthy of study. Second, during the 10 years since its establishment, FIPDes has enrolled both EU and non-EU students from more than 50 countries, as well as fostering 102 collaborative partnerships. How EU and non-EU students perceived their process of cultivating innovative skills, knowledge and competences in food innovation in this European programme was thus also worthy of study. Conceptual Framework

To investigate how FIPDes provides international exchange programmes in the subject of food innovation, an analytical framework was constructed by integrating both Mathiesen & Lager's (2007) insights of evaluating students' perceptions on an international exchange programme and the triple helix model (Cai, 2017; Viaggi et al., 2021).

International Student Exchange

International student exchange can be interchangeably named student exchange, student travel exchange, etc. (Chew & Croy, 2011; Mathiesen & Lager, 2007). International student exchange involves immersion programmes in higher education, enabling students to study abroad for a short period so that they can become more capable of living in a globalising world (DeLong et. al., 2011). Notably, there has been a rising trend of studying the effectiveness of international student exchanges by evaluating students’ intercultural sensitivity (Litvin, 2003; Ruddock & Turner, 2007). Attempting to discuss the criteria for assessing the successfulness of international student exchange, Mathiesen and Lager (2007) established the feedback cycle of international student exchange, including the what students gain from the international exchange experience (i.e. understanding cultural differences and being more capable of working in their home country and abroad), which can be an evaluating criterion of international exchange programmes. The structure of this study followed Mathiesen and Lager (2007) by providing the general background of FIPDes earlier in this paper. Students’ expectations and perceptions of the FIPDes international exchange programme in food innovation and product design were then identified and analysed.

Triple Helix Model

Previous scholars have used the triple helix model to explain the dynamics of R&D in university–industry–government cooperation (Agrawal, 2001; Ma and Cai, 2021). In the global context, government, industry and higher education institutions within the innovation process are interacting with other actors locally and internationally. Positioning globalisation in the middle of the triple helix framework, Cai et al. (2019) further elaborated the triple helix model through three international exchange cooperation spheres (i.e. international government cooperation, international industry cooperation and international university cooperation). Each sphere is supported with space to maintain an international cooperative atmosphere (Cai & Etzkowitz, 2020). Viaggi et al. (2021) suggested that when the curriculum is based on an international exchange offered by participating universities, other learning opportunities (i.e. co-creation events) can also reflect the university–industry cooperation (Viaggi et al., 2021). Agrawal (2001) further highlighted that non-linear knowledge transfer between universities, industry and government can be presented through international exchange activities. This study employed Cai et al.’s (2019) triple helix model to analyse how EU and non-EU students perceived their international exchange experiences of food innovation education.

Methodology

Critical discourse analysis (CDA) is an analytical approach that focuses on the agency and power relations among social actors revealed in texts (Elsharkawy, 2017). Previous scholars have used CDA to analyse testimonials to explore the underlying assumptions and thoughts regarding the services provided (Karim et al., 2019). The testimonials may be selectively shown by the host universities as follow up on personal experiences, but they are also accounts of personal experiences from a first person perspective. In particular, the tools of CDA allowed us to probe how EU and non-EU students’ perceived their learning of food innovation in the international exchange context. 18 graduate's testimonials uploaded to the official website of FIPDes from 2015-2021 were downloaded. Of the 18 testimonials analysed, 12 were from students from non-EU countries, while the remaining six were from students from EU countries (

Table 1). The testimonials from EU and non-EU students were separately placed in two Word files and uploaded to the Text Network Analysis Software. Following Fairclough’s (2003) three-dimensional interpretation framework of CDA, the data analysis involved three tiers. First, I described the textual features of the testimonials, with a focus on how EU and non-EU students accounted for their experiences in FIPDes. Topical clusters with the highest percentage of nodes and entries were identified to show the core themes mentioned by the graduates. Second, I focused on an interpretation of EU and non-EU students’ descriptions of their learning experiences (i.e. purpose and content of the programme and elements of learning and teaching). Words with the highest frequency, degree and betweenness centrality were identified. Degree refers to the number of connections that one word has within the text network. Betweenness centrality refers to the significance of the word in controlling the flow of information in the text network (Leydesdorff, 2007). Third, students’ perceptions of the highlighting practices of FIPDes were reflected on based on the textual analysis.

Results

Key Topics among the Students

Frequent words of the testimonials were set as nodes in the network. Based on the percentage of nodes, four main topical groups emerged:

food innovation (18%),

learning experience (17%),

business (11%) and

practical skills (11%) (

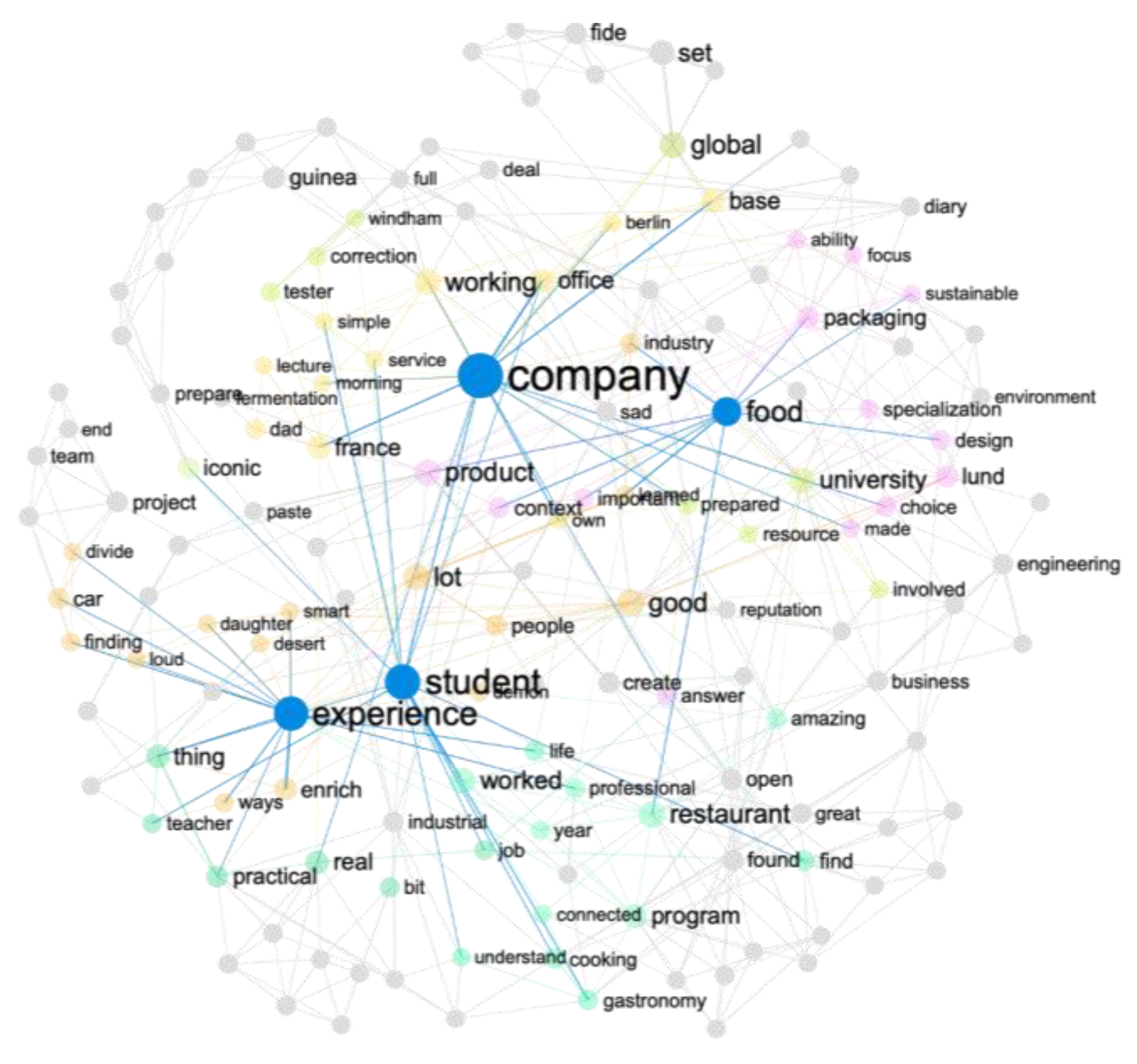

Table 2). This showed that EU students were more concerned with the learning application of food innovation, engineering processes and business management in the exchange experiences. This claim was also proven by the most influential words. Using the Jenks elbow cutoff algorithm as the measurement, the most influential words included ‘company’, ‘students’, ‘experience’ and ‘food’, which had the highest betweenness centrality (0.329, 0.193, 0.189 and 0.120, respectively) and connected the highest number of words in the network, including ‘practical’, ‘cooking’, ‘packaging’, ‘working’ and ‘product’ (

Figure 1). This also showed that EU students were concerned with the preparation of practical knowledge and skills for food innovation in the international exchange programme. ‘International’ was not mentioned at all by EU students, suggesting that the international context was not strongly acknowledged by these students, even though they were involved in the international exchange programme.

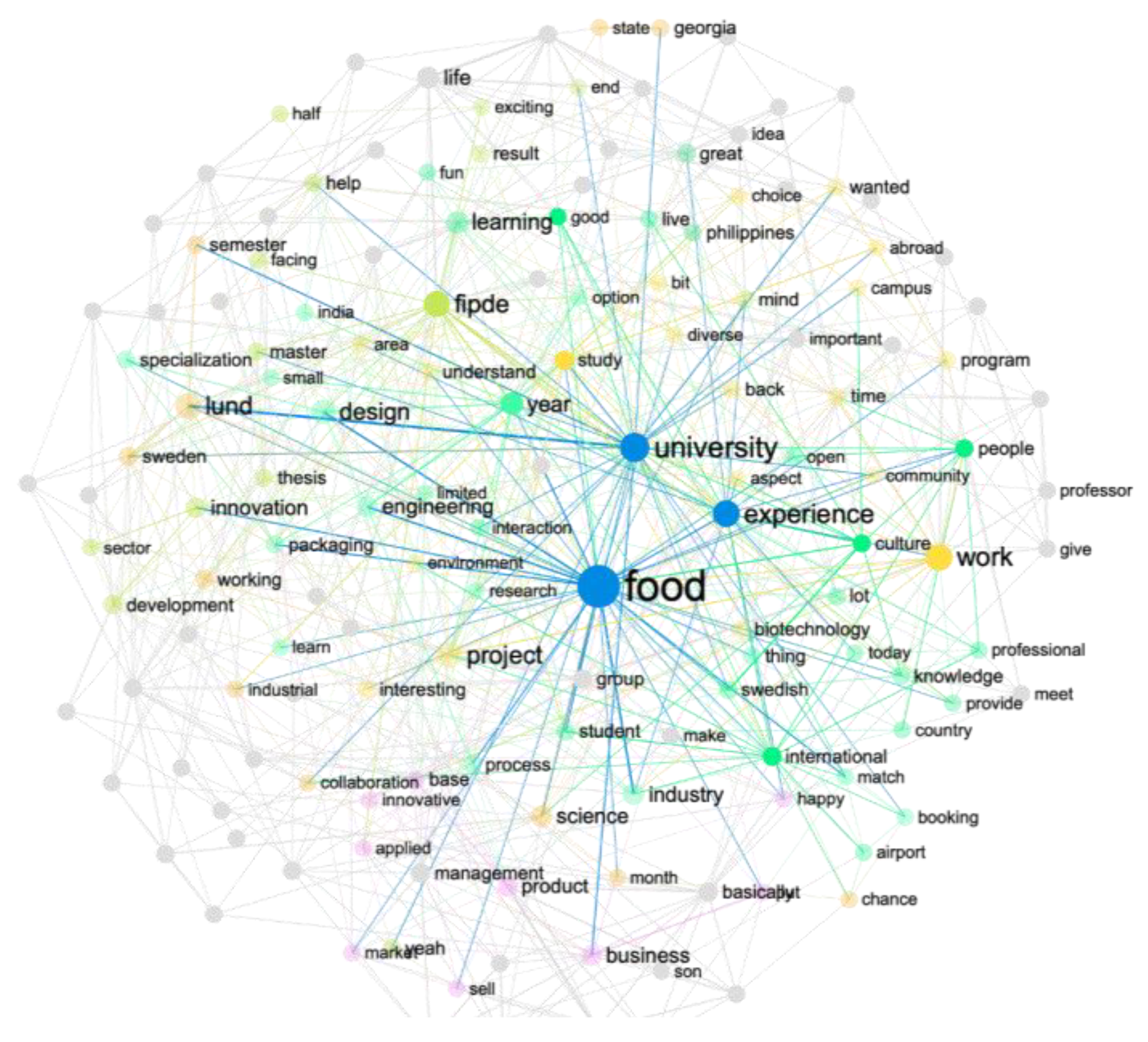

The testimonials of non-EU students also generated four main topical groups including ‘learning experience’, ‘business’ and ‘food innovation’ (

Table 2), while the most influential elements included ‘food’ and ‘experience’ (

Figure 2). Therefore, non-EU students shared some similarities with EU students in perceiving the international exchange experience as a springboard for participating in the food innovation industry. However, non-EU students emphasised more their exposure to the international learning experience. This was evident from the main topical group ‘international experience’, which contributed 11% of the nodes within the network. Relevant words included ‘culture’, ‘meet’ and ‘interaction’. This showed that the multicultural interaction in the international exchange programme was significant in shaping non-EU students’ learning process. When comparing the text network of EU and non-EU students, 34 of the total nodes (23%) only appeared in non-EU testimonials, including the themes of ‘innovation’ and ‘change’. ‘Innovation’ was mainly connected to words such as ‘learn’, ‘working’ and ‘food’. Although non-EU students were concerned with the knowledge learnt about the food innovation industry, they perceived this knowledge as a kind of capital for innovation in the industry. Moreover, non-EU students acknowledged a perceptual change during the international exchange programme, where ‘change’ mainly referred to words such as ‘perspective’ and ‘idea’.

Word Frequency

Calculating the word frequency found in the testimonials,

Table 3 reveals the ranking of the most frequent words mentioned by EU and non-EU students. The groups of EU and non-EU students used different terms to describe their learning context. EU students used the word ‘global’ (frequency rate: 1.389%). They mainly perceived their learning context as ‘global’, as words such as ‘company’, ‘office’ and ‘industry’ co-occurred with ‘global’. This showed that EU students identified the global interaction within the food innovation industry. However, they did not link such a global context with their learning, as there was no correlation between the words ‘global’ and ‘learning’ at all.

By contrast, non-EU students used ‘international’ (ranked 5th; frequency rate: 1.07%) in their testimonials. ‘International’ had a direct correlation to ‘experience’, connecting to nine nodes of 150 (6%), with a total betweenness centrality of 0.140. Words such as ‘industry’, ‘collaboration’ and ‘partner’ were mentioned in relation to ‘international’. In addition, words such as ‘student’, ‘interaction’, ‘study’ and ‘university’ were mentioned, showing that non-EU students were also aware of the international university cooperation in their international exchange programme. As defined by various scholars, global and international have fundamental differences in meanings. Global only describes the political, societal and economic trends that connect different parts of the world together (Collins et al., 2016; Neubauer et al., 2019). Meanwhile, ‘international’ involves an ‘integration of the intercultural and global dimensions into the purpose, functions or delivery of . . . activity’ (Neubauer et al., 2019). EU and non-EU students, hence, had different understandings of the cooperation between governments, industry and universities in the international learning context.

Discussion and Conclusion

Analysed using the triple helix model, both EU and non-EU students tended to correlate their learning process to the industry sphere. However, non-EU students were more aware of the international learning environment in the programme. This may be explained by the fact that non-EU students were taking part in international mobility, so they emphasised a higher sense of valuing cultural differences towards different countries (Zimmermann, Greischel & Jonkmann, 2020; Collins et al., 2017). Therefore, student exposure to the international learning context does not necessarily lead to student awareness of the global cooperation within the triple helix model, nor does it help students connect the international context to their personal learning. This result could provide insights for other regional universities organising international exchange programmes.

Moreover, the differences in students’ perceptions of the meanings of ‘global’ and ‘international’ after being exposed to the international experience (i.e. international exchange programme) are worthy of further study. For EU students, they were engaging in the Erasmus programme for exposure to the food innovation industry in Europe, but their awareness of global interaction between industry and universities may not have been enhanced. This result may provide another insight for other Erasmus programmes seeking to evaluate the cultivation of global competences among EU students in international exchange programmes. How EU students develop their sense of awareness of internationalisation in their learning contexts is another valuable question requiring further exploration.

References

- Agrawal, A. (2001). University-to-industry knowledge transfer: Literature review and unanswered questions. International Journal of Management Reviews, 3(4), 285–302. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, Z., Su, L., & Ahmed, K. (2017). Pakistani youth manipulated through night-packages advertising discourse. Human Systems Management, 36 (2). 151–162. [CrossRef]

- Bertelsen, R. G. (2018). Transnational GCC triple-helix relations for building smart cities under globalization. In Samad, W., Azar, E. (eds) Smart cities in the Gulf (pp. 247–271). Springer Singapore.

- Blondel, V. D., Guillaume, J.-L., Lambiotte, R., & Lefebvre, E. (2008). Fast unfolding of communities in large networks. Journal of Statistical Mechanics, 2008(10), 10008–10012. [CrossRef]

- Breznik, K., & Skrbinjek, V. (2020). Erasmus student mobility flows. European Journal of Education, 55(1), 105–117. [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y. (2017). From an analytical framework for understanding the innovation process in higher education to an emerging research field of innovations in higher education. Review of Higher Education, 40(4), 585–616. [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y., Ferrer, R. B., & Lastra, L. M. J. (2019). Building university–industry co-innovation networks in transnational innovation ecosystems: Towards a transdisciplinary approach of integrating social sciences and artificial intelligence. Sustainability, 11(17), 4633. [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y., & Etzkowitz, H. (2020). Theorizing the triple helix model: Past, present, and future. Triple Helix, 6 (1), 1–38. [CrossRef]

- Chew, A., & Croy, W. (2011). International education exchanges: Exploratory case study of Australian-based tertiary students’ incentives and barriers. Journal of Teaching in Travel & Tourism, 11(3), 253–270. [CrossRef]

- Collins, C., Castro, A., & Ryan, T. (2016). The driving forces of higher education: Westernization, Confucianism, economization, and globalization. In Collins, C., Castro, A., Ryan, T. (eds) The Palgrave Handbook of Asia Pacific Higher Education (pp. 279–291). Palgrave Macmillan US.

- Collins, F. L., Ho, K. C., Ishikawa, M., & Ma, A.-H. S. (2017). International Student Mobility and After-Study Lives: the Portability and Prospects of Overseas Education in Asia: International Student Mobility and After-Study Lives. Population Space and Place, 23(4), e2029. [CrossRef]

- DeLong, M., Geum, K., Gage, K., McKinney, E., Medvedev, K., & Park, J. (2011). Cultural exchange: Evaluating an alternative model in higher education. Journal of Studies in International Education, 15(1), 41–56. [CrossRef]

- Elsharkawy, A. (2017, October 4–6). What is critical discourse analysis (CDA)? Second Literary Linguistics Conference, Johannes Gutenberg-Universität Mainz, Germany.

- Eurpean Commission (n.d.). Erasmus Mundus action. Erasmus+ official website. https://ec.europa.eu/programmes/erasmus-plus/programme-guide/part-b/key-action-2/partnerships-cooperation/erasmus-mundus-action_en.

- Fairclough, N. (2003). Analysing discourse: Textual analysis for social research. Routledge.

- FIPDes. (2021). FIPDES universities. FIPDes official website. http://www.fipdes.eu/?FIPDes-Universities-30.

- Goddard, J. (2017). Universities, innovation and urban and regional development: Challenges, tensions and opportunities in Europe.Higher Education Authority Official Website. https://hea.ie/assets/uploads/2017/04/john_goddard_26.11.14.pdf.

- Kaltenecker, E., & Mojarro, B. (2019). Innovation and globalization of executive education programs. Evodio Kaltenecker Official Website. https://evodiokaltenecker.com/innovation-and-globalization-of-executive-education-programs/.

- Karim, A., Shahed, F., Mohamed, A., Rahman, M., & Ismail, S. (2019). Evaluation of the teacher education programs in EFL context: A testimony of student teachers’ perspective. International Journal of Instruction, 12(1), 127–146. [CrossRef]

- Kedia, B. L., & Englis, P. D. (2011). Internationalizing business education for globally competent managers. Journal of Teaching in International Business, 22(1), 13–28. [CrossRef]

- Leydesdorff, L. (2007). ‘Betweenness centrality’ as an indicator of the ‘interdisciplinarity’ of scientific journals. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 58(9), 1303-1319. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J., Kim, N., & Wu, Y. (2019). College readiness and engagement gaps between domestic and international students. Higher Education, 77(3), 505–523. [CrossRef]

- Litvin, S. (2003). Tourism and understanding: The MBA study mission. Annals of Tourism Research, 30(3), 77–93. [CrossRef]

- Ma, J., & Cai, Y. (2021). Innovations in an institutionalised higher education system: The role of embedded agency. Higher Education, 1–19. [CrossRef]

- Mathiesen, S., & Lager, P. (2007). A model for developing international student exchanges. Social Work Education, 26(3), 280–291. [CrossRef]

- Mizikaci, F., & Arslan, Z. (2019). A European perspective in academic mobility: A case of Erasmus program. Journal of International Students, 9(2), 705–725. [CrossRef]

- Neubauer, D., Mok, K., & Edwards, S. (2019). Contesting globalization and internationalization of higher education. Springer International Publishing AG.

- Ruddock, H., & Turner, D. (2007). Developing cultural sensitivity: Nursing students’ experiences of a study abroad programme. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 59(4), 361–369. [CrossRef]

- Viaggi, D., Barrera, C., Castelló, M. L., Rosa, M.D., Heredia, A., Hobley, T. J, Knöbl, C.F., Materia, V. C., Xu, S. M., Romanova, G., Russo, S., Segui, L. & Viereck, N. (2021). Education for innovation and entrepreneurship in the food system: The Erasmus BoostEdu approach and results. Current Opinion in Food Science, 42, 157–166. [CrossRef]

- Wong, P. K., Ho, Y. P., & Singh, A. (2007). Towards an ‘entrepreneurial university’ model to support knowledge-based economic development: The case of the National University of Singapore. World Development, 35(6), 941–958. [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, J., Greischel, H., & Jonkmann, K. (2020). The development of multicultural effectiveness in international student mobility. Higher Education, 82(6), 1071–1092. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).