Submitted:

01 May 2024

Posted:

03 May 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Synthesis of the Nanoparticles

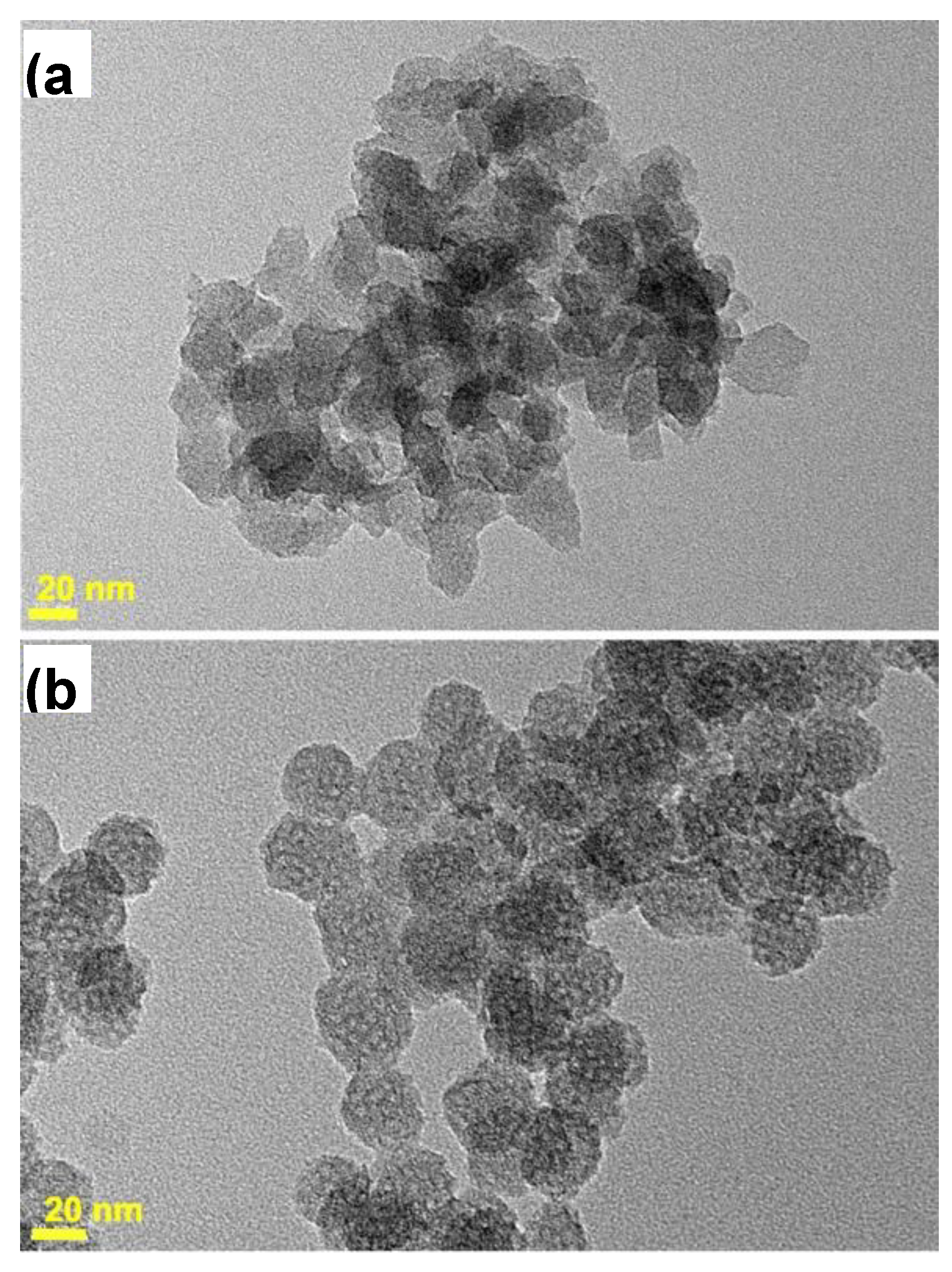

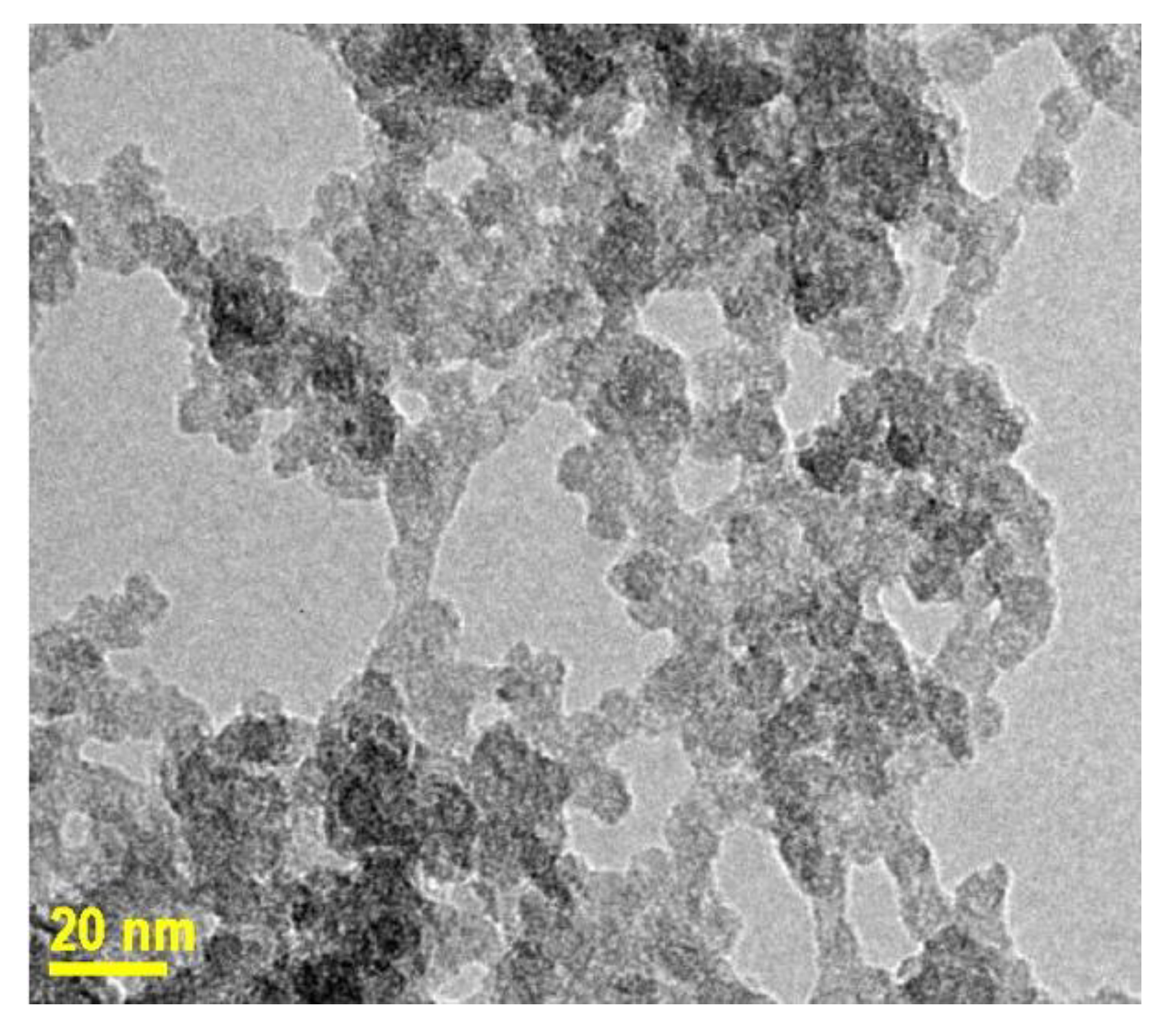

2.2. Transmission Electron Microscopy

2.3. Images Analysis

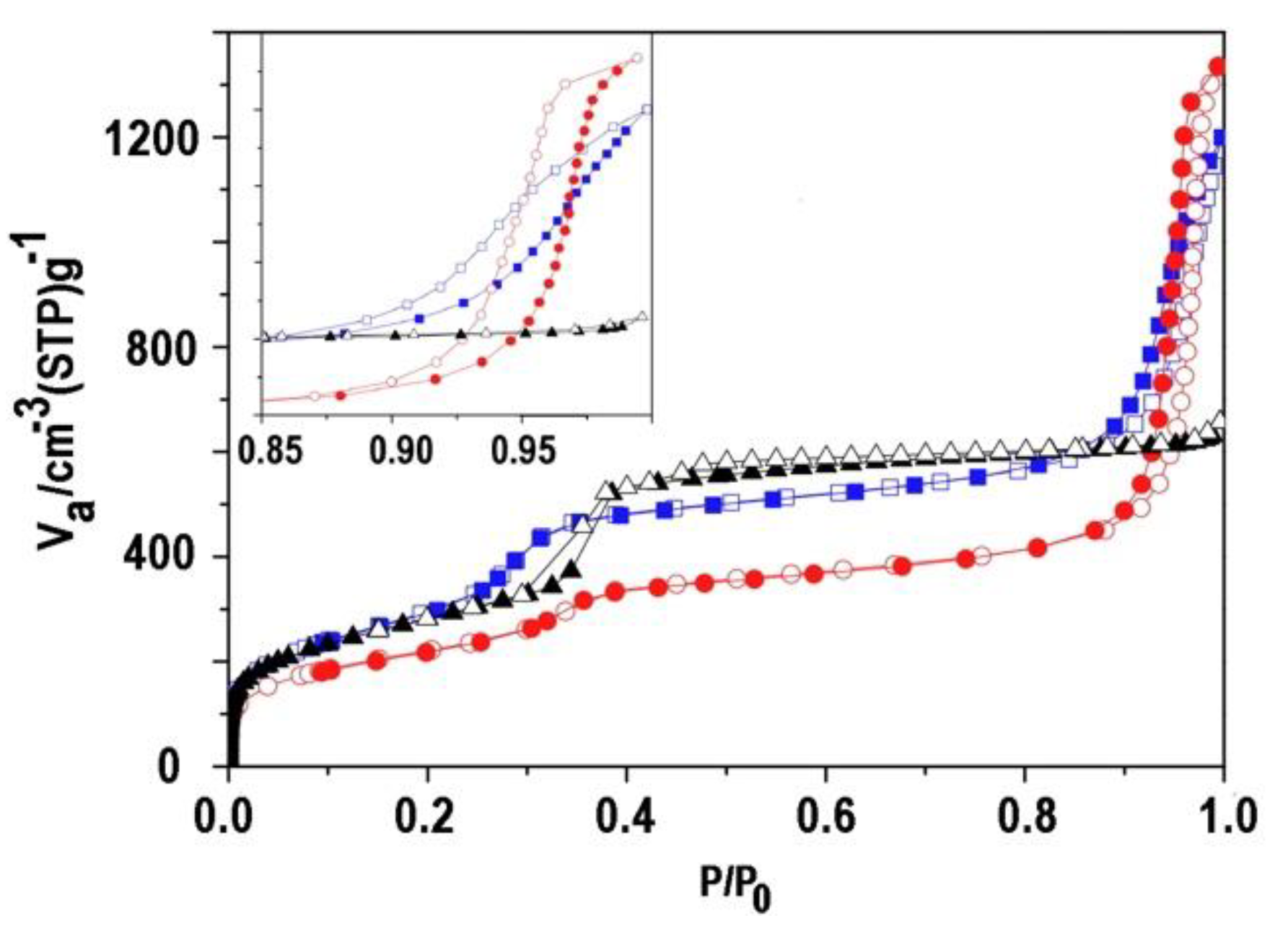

2.3. DLS, XR, TGA and Nitrogen Isotherms

3. Results and Discussion

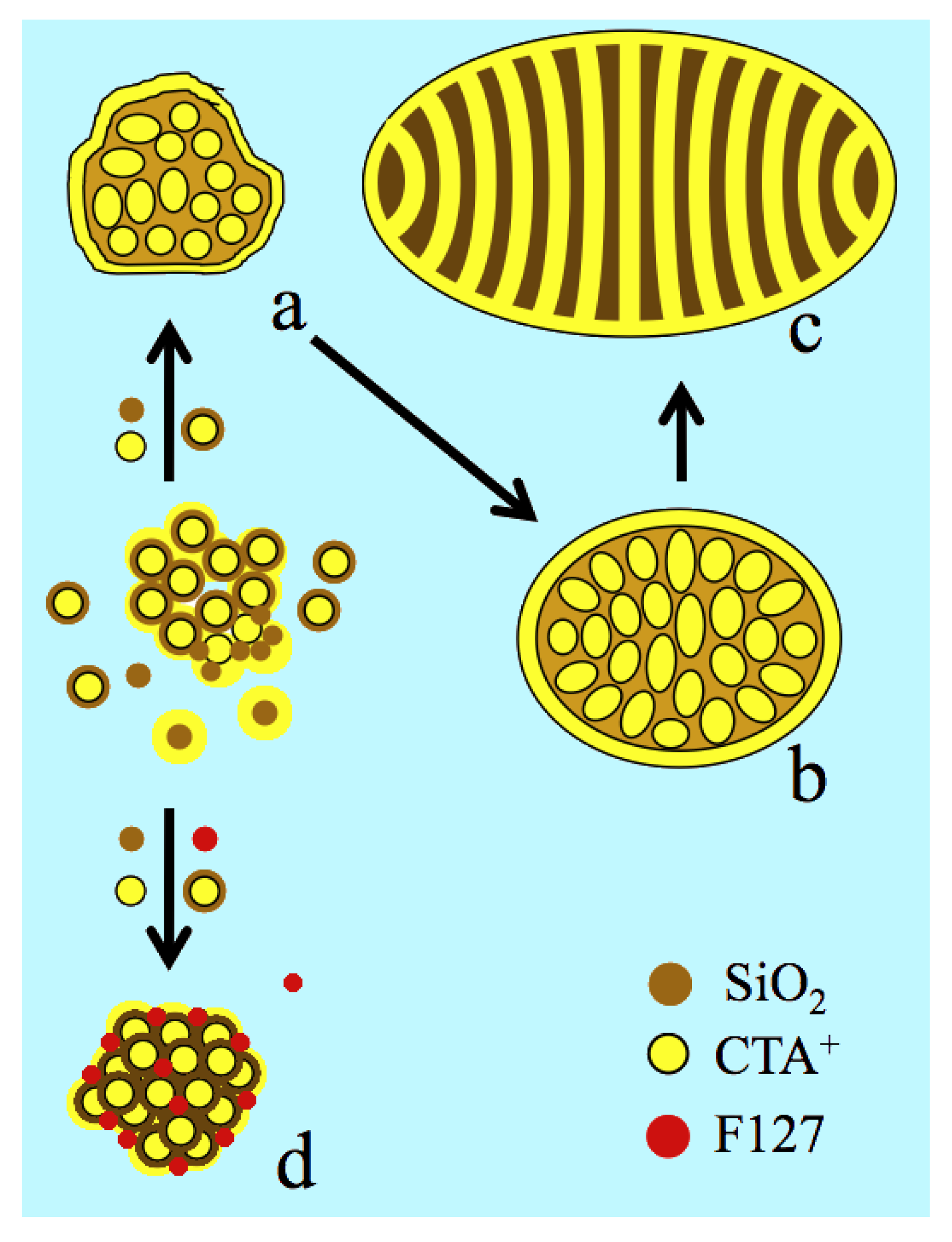

3.1. Time Controlled Synthesis Approach

3.4. Thermal and Hydrothermal Stability

3.5. Surfactant to Silica Balance in US-MSN

3.6. synthesis Parameters Versus Particle Size, Morphology and Colloidal Stability

3.7. Role of F127 Additive as Charge Density Modulator and Particle Size Stabilizer

3.7. Protocrystalline US-MSN as Precursor State of Nuclei

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vivero-Escoto, J.L.; Slowing, II; Trewyn, B.G.; Lin, V.S.Y. Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles for Intracellular Controlled Drug Delivery. Small 2010, 6, 1952–1967. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vallet-Regí, M.; Colilla, M.; González, B. Medical applications of organic-inorganic hybrid materials within the field of silica-based bioceramics. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011, 40, 596–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cotí, K.K.; Belowich, M.E.; Liong, M.; Ambrogio, M.W.; Lau, Y.A.; Khatib, H.A.; Zink, J.I.; Khashab, N.M.; Stoddart, J.F. Mechanised nanoparticles for drug delivery. Nanoscale 2009, 1, 16–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashley, C.E.; Carnes, E.C.; Phillips, G.K.; Padilla, D.; Durfee, P.N.; Brown, P.A.; Hanna, T.N.; Liu, J.W.; Phillips, B.; Carter, M.B.; et al. The targeted delivery of multicomponent cargos to cancer cells by nanoporous particle-supported lipid bilayers. Nature Materials 2011, 10, 389–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angelova, A.; Angelov, B.; Mutafchieva, R.; Lesieur, S.; Couvreur, P. Self-Assembled Multicompartment Liquid Crystalline Lipid Carriers for Protein, Peptide, and Nucleic Acid Drug Delivery. Acc. Chem. Res. 2011, 44, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frens, G. CONTROLLED NUCLEATION FOR REGULATION OF PARTICLE-SIZE IN MONODISPERSE GOLD SUSPENSIONS. Nature-Physical Science 1973, 241, 20–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sari, S.M.C.; Debouttière, P.J.; Lamartine, R.; Vocanson, F.; Dujardin, C.; Ledoux, G.; Roux, S.; Tillement, O.; Perriat, P. Grafting of colloidal stable gold nanoparticles with lissamine rhodamine B:: an original procedure for counting the number of dye molecules attached to the particles. J. Mater. Chem. 2004, 14, 402–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerouge, F.; Melnyk, O.; Durand, J.O.; Raehm, L.; Berthault, P.; Huber, G.; Desvaux, H.; Constantinesco, A.; Choquet, P.; Detour, J.; et al. Towards thrombosis-targeted zeolite nanoparticles for laser-polarized <SUP>129</SUP>Xe MRI. J. Mater. Chem. 2009, 19, 379–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, F.; Sougrat, R.; Albela, B.; Bonneviot, L. Nanoblock Aggregation-Disaggregation of Zeolite Nanoparticles: Temperature Control on Crystallinity. J. Phys. Chem. C 2011, 115, 7285–7291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowler, C.E.; Khushalani, D.; Lebeau, B.; Mann, S. Nanoscale Materials with Mesostructured Interiors. Adv. Mater. 2001, 13, 649–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadasivan, S.; Khushalani, D.; Mann, S. Synthesis and shape modification of organo-functionalised silica nanoparticles with ordered mesostructured interiors. J. Mater. Chem. 2003, 13, 1023–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadasivan, S.; Fowler, C.E.; Khushalani, D.; Mann, S. Nucleation of MCM-41 nanoparticles by internal reorganization of disordered and nematic-like silica surfactant clusters. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2002, 41, 2151–2153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.W.; Chung, P.W.; Lin, V.S.Y. Facile Synthesis of Monodisperse Spherical MCM-48 Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles with Controlled Particle Size. Chem. Mater. 2010, 22, 5093–5104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kresge, C.T.; Leonowicz, M.E.; Roth, W.J.; Vartuli, J.C.; Beck, J.S. ORDERED MESOPOROUS MOLECULAR-SIEVES SYNTHESIZED BY A LIQUID-CRYSTAL TEMPLATE MECHANISM. Nature 1992, 359, 710–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Y.; Zhao. On the Controllable Soft-Templating Approach to Mesoporous Silicates. Chem. Rev. 2007, 107, 2821–2860. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Haskouri, J.; de Zárate, D.O.; Guillem, C.; Beltrán-Porter, A.; Caldés, M.; Marcos, M.D.; Beltrán-Porter, D.; Latorre, J.; Amorós, P. Hierarchical porous nanosized organosilicas. Chem. Mater. 2002, 14, 4502–4504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büchel, G.; Grün, M.; Unger, K.K.; Matsumoto, A.; Tsutsumi, K. Tailored syntheses of nanostructured silicas:: Control of particle morphology, particle size and pore size. Supramol. Sci. 1998, 5, 253–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesa, M.; Sierra, L.; Patarin, J.; Guth, J.L. Morphology and porosity characteristics control of SBA-16 mesoporous silica. Effect of the triblock surfactant Pluronic F127 degradation during the synthesis. Solid State Sciences 2005, 7, 990–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesa, M.; Sierra, L.; Guth, J.L. Contribution to the study of the formation mechanism of mesoporous SBA-15 and SBA-16 type silica particles in aqueous acid solutions. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2008, 112, 338–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, Z.A.; Zhang, L.; Guo, M.Y.; Liu, Y.L.; Huo, Q.S. Synthesis of Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles via Controlled Hydrolysis and Condensation of Silicon Alkoxide. Chem. Mater. 2009, 21, 3823–3829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Möller, K.; Kobler, J.; Bein, T. Colloidal suspensions of mercapto-functionalized nanosized mesoporous silica. J. Mater. Chem. 2007, 17, 624–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moller, K.; Kobler, J.; Bein, T. Colloidal suspensions of nanometer-sized mesoporous silica. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2007, 17, 605–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobler, J.; Möller, K.; Bein, T. Colloidal suspensions of functionalized mesoporous silica nanoparticles. ACS Nano 2008, 2, 791–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cauda, V.; Argyo, C.; Schlossbauer, A.; Bein, T. Controlling the delivery kinetics from colloidal mesoporous silica nanoparticles with pH-sensitive gates. J. Mater. Chem. 2010, 20, 4305–4311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cauda, V.; Schlossbauer, A.; Bein, T. Bio-degradation study of colloidal mesoporous silica nanoparticles: Effect of surface functionalization with organo-silanes and poly(ethylene glycol). Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2010, 132, 60–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Xu, L.-L.; Jiang, J.-G.; Calin, N.; Lam, K.-F.; Zhang, S.-J.; Wu, H.-H.; Wu, G.-D.; Albela, B.; Bonneviot, L.; et al. Facile Large-Scale Synthesis of Monodisperse Mesoporous Silica Nanospheres with Tunable Pore Structure. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2013, 135, 2427–2430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikari, K.; Suzuki, K.; Imai, H. Grain size control of mesoporous silica and formation of bimodal pore structures. Langmuir 2004, 20, 11504–11508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, K.; Ikari, K.; Imai, H. Synthesis of silica nanoparticles having a well-ordered mesostructure using a double surfactant system. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2004, 126, 462–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urata, C.; Aoyama, Y.; Tonegawa, A.; Yamauchi, Y.; Kuroda, K. Dialysis process for the removal of surfactants to form colloidal mesoporous silica nanoparticles. Chem. Commun. 2009, 5094–5096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, H.; Gao, F.; Valtchev, V. Nanosized inorganic porous materials: fabrication, modification and application. Journal of Materials Chemistry A 2016, 4, 16756–16770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benlekbir, S.; Epicier, T.; Bausach, M.; Aouine, M.; Berhault, G. STEM HAADF electron tomography of palladium nanoparticles with complex shapes. Philos. Mag. Lett. 2009, 89, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.J.; Albela, B.; Perriat, P.; He, M.Y.; Bonneviot, L. Accessibility Control on Copper(II) Complexes in Mesostructured Porous Silica Obtained by Direct Synthesis using Bidentate Organosilane Ligands. Langmuir 2010, 26, 13493–13501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edler, K.J.; Reynolds, P.A.; White, J.W.; Cookson, D. Diffuse wall structure and narrow mesopores in highly crystalline MCM-41 materials studied by X-ray diffraction. J. Chem. Soc.-Faraday Trans. 1997, 93, 199–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edler, K.J.; Reynolds, P.A.; White, J.W. Small-angle neutron scattering studies on the mesoporous molecular sieve MCM-41. J. Phys. Chem. B 1998, 102, 3676–3683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broekhoff, J.C.P.; De Boer, J.H. Studies on pore systems in catalysts: XI. Pore distribution calculations from the adsorption branch of a nitrogen adsorption isotherm in the case of ‚Äúink-bottle‚Äù type pores. J. Catal. 1968, 10, 153–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abry, S.; Lux, F.; Albela, B.; Artigas-Miquel, A.; Nicolas, S.; Jarry, B.; Perriat, P.; Lemercier, G.; Bonneviot, L. Europium(III) Complex Probing Distribution of Functions Grafted using Molecular Stencil Patterning in 2D Hexagonal Mesostructured Porous Silica. Chem. Mater. 2009, 21, 2349–2359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spanoudaki, A.; Albela, B.; Bonneviot, L.; Peyrard, M. The dynamics of water in nanoporous silica studied by dielectric spectroscopy. European Physical Journal E 2005, 17, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muroyama, N.; Yoshimura, A.; Kubota, Y.; Miyasaka, K.; Ohsuna, T.; Ryoo, R.; Ravikovitch, P.I.; Neimark, A.V.; Takata, M.; Terasaki, O. Argon adsorption on MCM-41 mesoporous crystal studied by in situ synchrotron powder X-ray diffraction. J. Phys. Chem. C 2008, 112, 10803–10813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleitz, F.; Schmidt, W.; Schüth, F. Calcination behavior of different surfactant-templated mesostructured silica materials. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2003, 65, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikari, K.; Suzuki, K.; Imai, H. Structural control of mesoporous silica nanoparticles in a binary surfactant system. Langmuir 2006, 22, 802–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A 100 nm particle covered by a double (tail to tail) layer of cationic surfactant ~ 4 nm thick would lead to an excess of 40 mol% of surfactant corresponding to a total loss of 50 wt% that is smaller that the measured mass loss. Note also that filling completely the inter granular space would produce a material with a total mass loss of ca. 62 wt%, which is close to the measurement for MSN-100-B.

- Muto, S.; Imai, H. Relationship between mesostructures and pH conditions for the formation of silica-cationic surfactant complexes. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2006, 95, 200–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A strong adsorption of F127 producing a 1 nm thick monolayer on the surface of a 22 nm particle will develop a volume that is 30 % that of the particle. Knowing that the internal pore volume filled by the surfactant afford 58% of the US-MSN volume for a 0.12 CTA/Si molar ratio, the external monolayer will correspond to 0.02 F127/Si for a F127 : CTA+ molar ratio of ca. 1:6. In comparison, a double layer of CTA+, which is ca. 4 nm thick would develop a volume 2.5 times larger than that of a 22 nm particle. Then, the external CTA+ would account for 4.3 times more than the internal CTA+. Since, the silica yield reaches at least 60% with a surfactant to silicon stoechiometry in solution equal to that of the particle without external CTA+, the external CTA+ double layer covers at most 16% (= 0.67/4.3 where 0.67 holdf for the ratio = 0.4/0.6 of unreacted surfactant). By comparison, in the conditions adopted by Imai et al. in refs 26 and 27 with little more than two times of CTA+ for larger particles of 100 nm, there is enough CTA+ to develop more than a double layer of CTA (ca. 1.5).

- Vartuli, J.C.; Schmitt, K.D.; Kresge, C.T.; Roth, W.J.; Leonowicz, M.E.; McCullen, S.B.; Hellring, S.D.; Beck, J.S.; Schlenker, J.L.; Olson, D.H.; et al. EFFECT OF SURFACTANT SILICA MOLAR RATIOS ON THE FORMATION OF MESOPOROUS MOLECULAR-SIEVES - INORGANIC MIMICRY OF SURFACTANT LIQUID-CRYSTAL PHASES AND MECHANISTIC IMPLICATIONS. Chem. Mater. 1994, 6, 2317–2326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monnier, A.; Schuth, F.; Huo, Q.; Kumar, D.; Margolese, D.; Maxwell, R.S.; Stucky, G.D.; Krishnamurty, M.; Petroff, P.; Firouzi, A.; et al. COOPERATIVE FORMATION OF INORGANIC-ORGANIC INTERFACES IN THE SYNTHESIS OF SILICATE MESOSTRUCTURES. Science 1993, 261, 1299–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landry, C.C.; Tolbert, S.H.; Gallis, K.W.; Monnier, A.; Stucky, G.D.; Norby, F.; Hanson, J.C. Phase transformations in mesostructured silica/surfactant composites. Mechanisms for change and applications to materials synthesist. Chem. Mater. 2001, 13, 1600–1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, Q.; Margolese, D.I.; Ciesla, U.; Demuth, D.G.; Feng, P.; Gier, T.E.; Sieger, P.; Firouzi, A.; Chmelka, B.F. Organization of Organic Molecules with Inorganic Molecular Species into Nanocomposite Biphase Arrays. Chem. Mater. 1994, 6, 1176–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echchahed, B.; Morin, M.; Blais, S.; Badiei, A.R.; Berhault, G.; Bonneviot, L. Ion mediation and surface charge density in phase transition of micelle templated silica. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2001, 44, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oye, G.; Sjöblom, J.; Stöcker, M. Synthesis and characterization of siliceous and aluminum-containing mesoporous materials from different surfactant solutions. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 1999, 27, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.Z.; Shao, Y.F.; Zhang, J.L.; Anpo, M. Synthesis of MCM-48 mesoporous molecular sieve with thermal and hydrothermal stability with the aid of promoter anions. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2006, 95, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badiei, A.R.; Cantournet, S.; Morin, M.; Bonneviot, L. Anion effect on surface density of silanolate groups in As-synthesized mesoporous silicas. Langmuir 1998, 14, 7087–7090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, Q.S.; Margolese, D.I.; Stucky, G.D. Surfactant control of phases in the synthesis of mesoporous silica-based materials. Chem. Mater. 1996, 8, 1147–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogura, T.; Sakai, K.; Sakai, H.; Abe, M. Synthesis of highly ordered mesoporous silica with a lamellar structure using assembly of cationic and anionic surfactant mixtures as a template. J. Phys. Chem. C 2008, 112, 12184–12187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galarneau, A.; Cangiotti, M.; di Renzo, F.; Sartori, F.; Ottaviani, M.F. Synthesis of large-pore micelle-templated silico-aluminas at different alumina contents. J. Phys. Chem. B 2006, 110, 20202–20210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryoo, R.; Joo, S.H.; Kim, J.M. Energetically favored formation of MCM-48 from cationic-neutral surfactant mixtures. J. Phys. Chem. B 1999, 103, 7435–7440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shechtman, D.; Blech, I.; Gratias, D.; Cahn, J.W. METALLIC PHASE WITH LONG-RANGE ORIENTATIONAL ORDER AND NO TRANSLATIONAL SYMMETRY. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1984, 53, 1951–1953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voyles, P.M.; Zotov, N.; Nakhmanson, S.M.; Drabold, D.A.; Gibson, J.M.; Treacy, M.M.J.; Keblinski, P. Structure and physical properties of paracrystalline atomistic models of amorphous silicon. J. Appl. Phys. 2001, 90, 4437–4451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treacy, M.M.J.; Gibson, J.M.; Keblinski, P.J. Paracrystallites found in evaporated amorphous tetrahedral semiconductors. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 1998, 231, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scurfield, G.; Segnit, E.R. PETRIFACTION OF WOOD BY SILICA MINERALS. Sediment. Geol. 1984, 39, 149–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruner, J.W. Cristobalite in bentonite. Am. Mineral. 1940, 25, 587–590. [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee, A.; Wenzel, T. Black opal from Honduras. Eur. J. Mineral. 1999, 11, 401–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustillo, M.A.; Martínez-Frías, J. Green opals in hydrothermalized basalts (Tenerife Island, Spain):: alteration and aging of silica pseudoglass. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2003, 323, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, J.H.; Lee, Y.H.; Fujiwara, H.; Wronski, C.R.; Collins, R.W. Optimization of hydrogenated amorphous silicon p-i-n solar cells with two-step i layers guided by real-time spectroscopic ellipsometry. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1998, 73, 1526–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wronski, C.R.; Collins, R.W. Phase engineering of a-Si:H solar cells for optimized performance. Sol. Energy 2004, 77, 877–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morral, A.F.I.; Cabarrocas, P.R.I.; Clerc, C. Structure and hydrogen content of polymorphous silicon thin films studied by spectroscopic ellipsometry and nuclear measurements. Physical Review B 2004, 69, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahan, A.H.; Roy, B.; Reedy, R.C.; Readey, D.W.; Ginley, D.S. Rapid thermal annealing of hot wire chemical-vapor-deposited <i>a</i>-Si:H films:: The effect of the film hydrogen content on the crystallization kinetics, surface morphology, and grain growth -: art. no. 023597. J. Appl. Phys. 2006, 99, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, E.P.; Chateigner, D.; Bein, T.; Valtchev, V.; Mintova, S. Capturing Ultrasmall EMT Zeolite from Template-Free Systems. Science 2012, 335, 70–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holland, B.T.; Blanford, C.F.; Stein, A. Synthesis of macroporous minerals with highly ordered three-dimensional arrays of spheroidal voids. Science 1998, 281, 538–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaudreuil, S.; Bousmina, M.; Kaliaguine, S.; Bonneviot, L. Synthesis of macrostructured silica by sedimentation-aggregation. Adv. Mater. 2001, 13, 1310–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaudreuil, S.; Bousmina, M.; Kaliaguine, S.; Bonneviot, L. Preparation of macrostructured metal oxides by sedimentation-aggregation. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2001, 44, 249–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).