Public service media (PSM), which was built on the idea of independence from commercial and political influences, play an important role in European democratic systems. However, in recent years, they have faced at least two major challenges. First, due to the fragmentation of the media environment, they increasingly struggle with audience outflow (Picone & Donders, 2020). Second, they are under strong pressure from populist politicians, and trust in them is declining among people with populist attitudes (Schulz et al., 2019).

Both of these challenges suggest that audience behavior towards PSM is changing. Even though the trust in PSM is stable and high in general, it is declining among specific audience groups (Smejkal et al., 2022). At present, however, we know relatively little about what audiences actually expect and want from PSM and what criteria are important for their satisfaction. This is despite the fact that PSM should perceive and treat the public as an active stakeholder (Jakubowicz, 2007). However, as Horz (2014) notes, this promise has so far remained rather rhetorical.

Multiple scholars noted the lack of research on the audience expectations of news media, in general (Gil de Zuniga & Hinsley, 2013; Karlsson & Clerwall, 2019; Steppat et al., 2020), although several such studies have been published in recent years (Gil de Zuniga & Hinsley, 2013; Loosen et al., 2020; Peifer, 2018; Riedl & Eberl, 2022; Steppat et al., 2020; van der Wurff & Schoenbach, 2014; Vos et al., 2019). However, with a few exceptions (Banjac, 2022; Karlsson & Clerwall, 2019; Schwaiger et al., 2022), these studies are mostly quantitative and deal mainly with expectations linked to the fulfillment of normative journalistic roles formulated by the journalists themselves (Hanitzsch & Vos, 2017). This, among other things, leaves the audience with little space to adequately express their expectations in their own words, and instead they typically have to choose from provided answers.

In addition, the neglect of the audience perspective extends to PSM research, where normative approaches and focus on policy and regulation prevail and where studies that explore the views of the public are still scarce, as lamented by multiple authors (Campos-Rueda & Goyanes, 2022; Chivers & Allan, 2022; Just et al., 2017; Lestón-Huerta et al., 2021). As Swart et al. (2022), and Banjac (2022) put it, there is a need to take a bottom-up view that allows for the re-evaluation of the expectations from the audience perspective. It is the audience that gives PSM its legitimacy so it necessary for the media to take an active interest in their views in order to maintain a healthy relationship (Vos et al., 2019). Moreover, existing studies on the audience expectations of PSM have focused on Western European countries (Campos-Rueda 2023; Campos-Rueda & Goyanes, 2022; Heise et al., 2014; Just et al., 2017; Sehl et al., 2020), but, as Just et al. (2017) point out, the audience view may be different in Eastern Europe due to the different history and legacy of PSM.

This is where this study steps in. Through 10 focus group discussions with the general public, it explores the audience expectations for PSM. As a case study, we selected the Czech Republic, a Central and Eastern European (CEE) country that serves as an exemplar because PSM holds a strong position in the national media landscape and it is widely perceived by the public as the most trusted source of news (Štětka, 2023). At the same time, it faces pressure from both populist politicians, who proclaim that it lacks objectivity and fails to fulfill its role (Okamura, 2023), and segments of the public, who argue that PSM does not provide adequate space for all views and opinions, including those often labeled as anti-system or non-democratic. Protests against PSM, particularly Czech Television, even joined anti-government protests in 2022. Hence, the Czech Republic provides an ideal context to investigate the expectations of both satisfied and dissatisfied members of the public.

Exploring Audience Expectations

Audiences have different ideas about the functions the media should perform in society (Loosen et al., 2020). In general, expectations can be defined as "subject-held or emitted statements that express a modal reaction about characteristics of object persons" (Biddle, 1979: 132).

According to Biddle (1979), these modal reactions can take three basic forms: prescriptive, cathectic, and descriptive. Prescriptive expectations refer to statements of approval or requests for a given characteristic (e.g., “the news content of PSM should be objective”). Cathectic expectations are based on individual evaluations of the characteristics the individual likes or dislikes about a given object (Biddle, 1979). This type of expectation necessarily involves an affective response that is based on prior experience with the object's performance. In the context of PSM, cathectic expectations are related to the criteria the public uses to evaluate its performance, encompassing both criticisms and appreciations (e.g., "I don't like when PSM does not refer to relevant sources in its coverage"). Finally, at the core of descriptive expectations are objective descriptions of a given characteristic, or beliefs about the characteristics of an object according to the criterion of subjective probability (Biddle, 1979). In the context of PSM, this can be, for example, the description of the media practices of a given audience member (e.g., "I like to watch documentaries on public service television").

Traditionally, audience expectations of the media have been examined largely in terms of prescriptive expectations. Thus, studies only examine what the audience thinks the media should do and, moreover, mostly in the context of the journalistic role conceptions defined by the journalists themselves and by media scholarship (Banjac, 2022; Fawzi & Motthes, 2020; Hanitzsch & Vos, 2017).

However, examining only prescriptive expectations from the media can be limiting. First, this approach may overlook the influence of audiences' lived experiences with media performance and the beliefs that they hold about the media. At the same time, these evaluations can help individuals to define themselves against the status quo, allowing them to express their expectations in unique ways. Thus, unlike some previous research (Campos-Rueda, 2023; Fawzi & Motthes, 2020), this study does not explicitly separate audience expectations and evaluations, but we understand evaluations as a certain manifestation of expectations, because they reveal the criteria that people use and, therefore, what is important to them when it comes to PSM. Second, audiences may also have expectations for the media that go beyond the normative role of journalism (Banjac, 2022). Moreover, in the case of PSM, these expectations are not necessarily only linked to news content, as their role is not limited to that either (Syvertsen, 2003).

Audience Expectations of Public Service Media and of News Media

The mission of PSM is to provide universal, diverse, and independent media services to the citizens of a given state (Price & Raboy, 2003). To be able to fulfill this mission, they must be independent from political and commercial pressures. What distinguishes PSM from commercial broadcasting is, among other things, the public funding of their activities (most often through license fees or public funds) and the fact that they are subject to stricter public control. Usually, oversight boards are responsible for this control and they are supposed to represent the interests of the public (Blázquez et al., 2022). Another difference is that they have a well-defined role that commits them to promote social cohesion, reflect the plurality of views, and support the national culture of a country (Holtz-Bacha, 2015; Just et al., 2017). They also have the obligation to produce programs that are valuable to society, both educationally and culturally (Syvertsen, 2003). That means that, in addition to producing quality journalism, they are obliged to produce quality non-news content.

Previous research shows that, in terms of PSM's non-news content, audiences mainly expect the provision of access to (national) culture, and the production of quality entertainment content for children and adults (Campos-Rueda, 2023). Studies that look at the expectations of PSM in terms of news content then conclude that audiences expect high-quality journalism, credible information, and the provision of sufficient background information (Sehl, 2020). Conversely, the public is least likely to expect that PSM will play the role of a public forum or provide analysis (Campos-Rueda, 2023). According to Campos-Rueda and Goyanes (2022), audiences positively assess the empathy with which PSM approach the coverage of topics, the support of community involvement and democratic institutions (i.e. mobilization function), and the way they provide information. They are least positive about the degree of their independence.

While previous research on the audience expectations of PSM news and non-news content is limited, considerable attention has been devoted to studying the public expectations of news content and journalism. The expectations of news content are currently quite widely mapped, but existing studies primarily focus on the news media in general and not specifically PSM. These studies agree that audiences expect the news media to adhere to the traditional normative standards of journalism, such as providing objective, accurate, and verified information (Heise et al., 2014; Loosen et al., 2020; Riedl, & Eberl, 2022; Tsfati et al., 2006; Vos et al., 2019; Willnat et al., 2019).

Given that objectivity is one of the most common audience expectations, and a concept that is both contested and notoriously difficult to define, it is worth further elaboration. According to Westerstahl (1983), objectivity builds on two dimensions: impartiality (which involves neutral presentation; i.e., the absence of an evaluation of the event by the journalist, and the provision of a balanced space for different parties or perspectives for the situation) and factuality (truth and relevance; i.e., a reflection of important social issues and currents of opinion). Similarly, Skovsgaard et al. (2013) distinguish four aspects of objectivity: no subjectivity, balance, hard facts (i.e., accuracy and factuality), and value judgements. However, in journalistic practice, objectivity, balance, and impartiality are frequently confused (Wahl-Jorgensen et al., 2017). This becomes problematic when impartiality is "tarnished by the pursuit of balance through the equal allocation of time to both (political) parties" (Wahl-Jorgensen et al., 2018: 785) and results in a "false balance", allocating equal time to opposing views, even when experts widely agree (Brüggemann & Engesser, 2017). Other important public expectations from the news media include providing analysis and interpretation, acting as a watchdog, and criticizing social problems and injustices (Gil de Zuniga & Hinsley, 2013; Heise et al., 2014; Loosen et al., 2020; Peifer, 2018; Riedl & Eberl, 2022; van der Wurff & Schoenbach, 2014; Vos et al., 2019). In addition, some studies mention the expectation that the news media will offer space for audiences to form their own opinions (van der Wurff & Schoenbach, 2014) and express these opinions (Gil de Zuniga & Hinsley, 2013; Vos et al., 2019; Willnat et al., 2019).

Method and Data

This study is based on two waves of focus group discussions with the general public in the Czech Republic (10 focus groups with 60 participants in total), which were part of a broader project that aimed to explore the expectations and evaluations of PSM in the country.

The first wave of six focus group discussions (with a total of 36 participants) was conducted between May and June 2022. The main criterion for recruiting participants was their political preference: two focus groups comprised of participants who voted for parties that could be described as populist in the preceding election; two focus groups consisted of people who voted for non-populist parties; and the remaining two groups were made up of non-voters. We employed the criterion of political preferences based on previous research (Smejkal et al., 2022), indicating differences in the reasons for trust between individuals who sympathize with populist parties and those who support other political parties. Consequently, this could mean that the expectations of the voters of populist and non-populist parties may vary. To address this, we chose a homogeneous approach (Morgan, 2019) because expectations of PSM can be a potentially polarizing topic and we aimed to provide a safe space for participants to express their views within a group of individuals assumed to share similar opinions. All six focus group discussions took place in Brno, the second largest city of the Czech Republic, in a rented conference room. They were moderated by one of the authors of the study. On average, each focus group lasted around 60 minutes.

The second wave with four focus groups (with a total of 24 participants) was conducted in November 2022. In this case, we adopted a maximum diversity sampling strategy; the participants roughly replicated the structure of the Czech population in terms of gender, age, education, region, the size of residence, and internet use (in addition, one of the questions asked in the recruitment process was about political preferences). Three focus group discussions were conducted online (via a video conferencing platform) and one in person (in the capital city of Prague due to its relatively easy accessibility from other regions); the latter was exclusively attended by those who indicated during recruitment that they use the internet less than once a month. In contrast to the previous wave of focus group discussions, this time we took a heterogeneous approach and divided the participants into groups regardless of their political preference. This allowed us to confront the findings with those of the first wave of focus groups. In practice, however, the heterogeneous approach to the formation of the focus groups did not appear to limit the participants in communicating their views; there was a friendly atmosphere in all of the discussion groups and participants did not seem to be shy about disagreeing with each other. On average, every focus group lasted around 90 minutes.

In both waves, the participants were recruited by a professional market research agency. More detailed information about the sample composition can be found in

Table S1 in the supplementary materials. The participants were informed in advance of the research topic, their informed consent was obtained prior to the discussion, and they were financially rewarded for their participation. In both waves of the focus groups, we first addressed expectations: the participants were asked to write down how they imagine the ideal PSM; this was followed by a group discussion. In the second part, we assessed the performance of Czech PSM: participants were asked to evaluate the extent to which Czech Television and Czech Radio meet their expectations.

Each focus group discussion was recorded and transcribed. The transcripts were analyzed in Atlas.ti software. An iterative process of reading and open coding was used. The authors first inductively coded the discussions independently of each other, then compared and discussed the codes. In the second step, the inductively developed codes were clustered into more general categories and then the relationships were sought between categories. This approach, using the principles of thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2022), allowed us to identify wider themes present in the data. In the analysis section, the participants' actual names were replaced with pseudonyms.

Results: What Public Wants, What Public Needs?

Ten focus group discussions unveiled a multitude of specific expectations that the public holds for PSM. We took a broad approach and analyzed the prescriptive, cathectic, and descriptive expectations (Biddle, 1979) together, because the data analysis showed that they are complementary and overlapping.

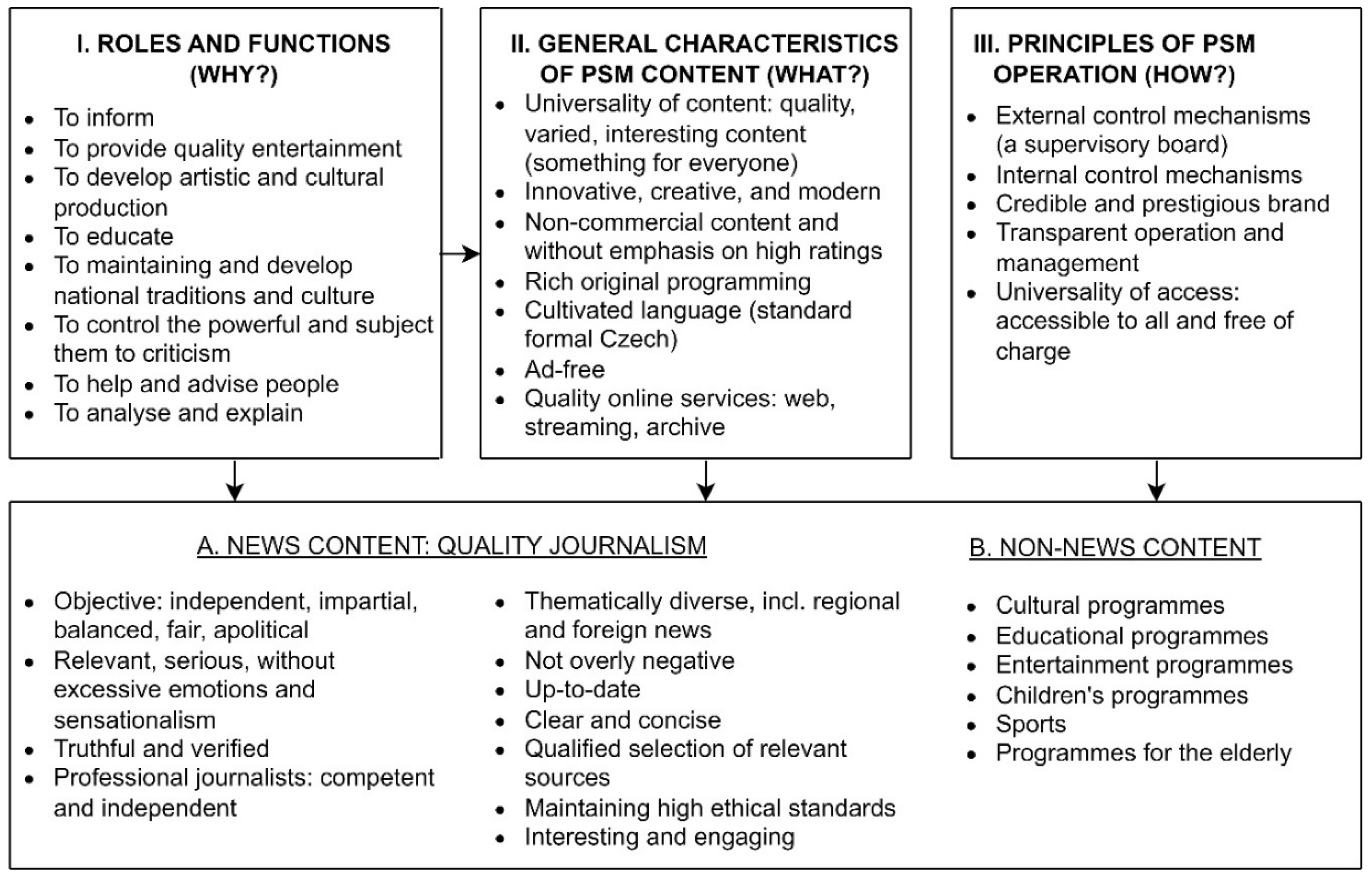

As summarized in

Figure 1, the public expectations of PSM encompass four main dimensions: (1) the expected roles and functions that PSM is intended to perform (i.e., why PSM exists); (2) the general characteristics of PSM content (i.e., what PSM content should generally be like); (3) the principles of PSM operation (i.e., how PSM should operate); and (4) the specific requirements for both news and non-news PSM content.

Expected PSM Roles and Functions

The participants generally concurred that the role of PSM is mainly to inform. In other words, to provide citizens with relevant and reliable information in an understandable manner. Simultaneously, they paid at least as much attention to the role of providing high-quality entertainment. They expect that the entertainment offered by PSM will not be crafted solely to maximize viewership but, instead, will aim to enrich the audience and serve various functions beyond mere relaxation, notably cultural and educational. As one of the participants put it: “(Czech) television should entertain. Educate and entertain. [...] (It should be) regardless of the profit (and) to provide quality entertainment.” [Eva: female, 60+ years old, secondary education].

Also, a relatively high emphasis was placed on the national perspective, both in terms of the news and non-news content. They expect PSM to “protect the values of the nation”. That means, PSM should maintain the national language, develop national culture and arts, present local and national news, interpret news from a national perspective, and provide educational programs on national history and geography. This national aspect, especially in the context of a relatively uniform international offering of commercial broadcasters, seems to be something that participants see as a unique added value of PSM:

It's Czech TV. It's for Czechs, so the content, as far as movies and fairy tales are concerned, should be in Czech. Czechs for Czechs…The others (commercial broadcasters) broadcast content from foreign countries and from all over the world. While it's nice to learn what's happening in Africa, in America, I don't get to know what's happening here. That's what interests me most of all. That's why one watches Czech Television or listens to Czech Radio, because one gets to know what's happening here.

[Filip: male, 31-40 years old, secondary education]

Other PSM roles and functions received less attention, such as the watchdog role (i.e., controlling and criticizing those in power), the role of helping and advising people, and the role of analyzing and explaining events.

Expected General Characteristics of the PSM Content

Another set of expectations pertains to the general characteristics of PSM content. Key among these expectations is the requirement for PSM to provide high-quality, diverse, and engaging content, and making it inclusive and appealing to all. The participants expect PSM to cater to everyone, offering content of interest and value to all. They appreciate that Czech PSM delivers specialized content to different audience groups and thus differs from commercial broadcasters:

I think it's important that there are those DIY shows, that there are gardening shows ... so I think it's great to have a medium that just gives everybody the opportunity to find something for themselves in a balanced way. It's unrivalled in the Czech media market.

[Julie: female, 31-40 years old, secondary education]

Such universality of content is another expected (and also perceived) distinct value of PSM, particularly when compared to commercial media. As one participant aptly summarized, “Commercial stations can pick and choose specific audiences, but that's what public service media is for, to be truly inclusive without exception” (Jan: male, 41-50 years old, secondary education). This theme emerged prominently during the focus group discussions.

Furthermore, the discussions suggest that the public expects PSM to provide content that is innovative, creative, and modern. These expectations were notably apparent in the criticisms voiced by the participants. Several described Czech PSM as “ossified”, outdated, and geared more toward older generations in both form and content. Simultaneously, they emphasized the need for modernization and greater efforts to engage younger audiences.

The participants also expect rich original programming (and, conversely, criticize the high proportion of reruns), with a focus on quality over ratings and commercial considerations. This is another important principle underlying the perceived unique value of PSM in the media ecosystem. The principle of programming regardless of ratings is expected to be evident not only in content, emphasizing quality programming for different audience groups and minority genres, but also in form. One participant described it metaphorically:

The commercial broadcast is kind of a nice big sports car. It may or may not be that way. Then the PSM broadcast, it gets to where it needs to go, but it may be like a beat-up car, in quotes, yeah, that's not that pretty.

[Filip: male, 31-40 years old, secondary education]

The question is, to what extent do the expectations of a certain moderation, solidity, and unpretentiousness conflict with the expectation of modern content and form appealing to younger audiences.

Other general content-related expectations include the use of cultivated language—standard formal Czech. While some participants praised Czech PSM for its elevated language compared to commercial media, others (a smaller portion) criticized the PSM presenters and reporters for using grammatically incorrect expressions. Regardless of the actual assessment, it is evident that this aspect is significant for part of the public. In addition, the participants expect limited or no advertising (some highlighted this as a significant and very welcome difference to commercial content), and high-quality and user-friendly online services, including websites, applications, streaming, and archives.

Expected Principles of PSM Operation

A third set of expectations relates to the principles of PSM operation. Some participants stressed the significance of the external and internal control mechanisms in PSM, which set it apart from commercial media and should enhance the quality assurance. They expect that the designated independent supervisory boards that oversee PSM (as opposed to commercial media) will ensure quality, including objectivity and independence, and that they will also oversee the financial management of PSM. This expectation goes hand in hand with the assumption that there is a fair and impartial selection process for board members. The participants also expect PSM to establish robust internal editorial mechanisms to ensure content quality, especially in terms of truthfulness and impartiality. Additional expected principles include upholding the credibility and prestige of PSM brands (i.e., Czech Television and Czech Radio), maintaining their transparent operations and financial management, and continuing the universality of access in the sense of providing the content to all citizens without paywalls.

Expectations Relating to News and Non-News Content

The greatest emphasis during the focus group discussions was placed on specific expectations related to both news and non-news PSM content. Here, the most frequently expressed prescriptive expectation, which also emerged as the most frequently cited point of criticism towards PSM's current performance, revolves around the theme of objectivity and independence. The importance of this expectation is evident in the following statement from one participant: “Without absolute independence, public service media is essentially pointless” [Jan: male, 41-50 years old, secondary education]. The participants used various terms to express this expectation, such as objectivity, independence, impartiality, balance, fairness, and apoliticality, often treating them as synonymous. One participant elaborated on the various dimensions of this expectation as follows:

I think it (PSM) should be fair, so that not only a certain group of people get space there [...] and that there's no favoritism towards any particular viewpoint, so that it's apolitical, and that there's some kind of committee to check it.

[Lena: female, 31-40 years old, tertiary education]

The participants also expect PSM's news and current affairs programs to be serious, without excessive emotions and sensationalism, and to provide relevant information. In this regard, they often contrasted PSM's news coverage with that of the commercial channels, emphasizing that PSM news should be (and, compared to commercial broadcasting, indeed is) unemotional or, at least, without strong emotional coloring, more serious, and free from exaggeration. It should provide information that is relevant, substantial, and in-depth. Other expectations include the truthfulness and veracity of the information; the professionalism, competence, and independence of PSM journalists; and thematic diversity, which includes coverage of both local and foreign news. The participants did not just express these expectations in a prescriptive manner but also thematized them when assessing the performance of Czech PSM. These were generally reasons for a positive evaluation and they were regarded as valued distinguishing features from commercial broadcasting.

Additionally, the participants expect PSM news to avoid excessive negativity (this demand stemmed from the perceived overload of some of them with negative news about the COVID-19 epidemic and the war in Ukraine); to be up-to-date; to be clear and concise; to draw from a qualified selection of relevant sources; to uphold high ethical standards; and to be both interesting and engaging.

When it comes to the expectations related to non-news content, the participants thematized six genres: cultural programs (e.g., they expect PSM to bring recordings of theatre plays, radio plays, classical music concerts, artistic non-commercial films, ballet and dance performances); educational programs (especially documentaries on various topics, but also travel shows, history shows, knowledge quizzes); quality entertainment programs (which overlaps with all the other genres mentioned); programs for children (mainly fairy tales and original series, but also special educational programs for children); sports (popular sports and major sporting events, but also smaller and less popular sports); and programs for the elderly (older films and older programs from the archive). These expectations emerged on all three levels.

The Trouble with Objectivity

Given that participants paid significant attention to the objectivity and independence of PSM, and that this aspect was also the most frequently mentioned point of criticism against the current performance of the Czech PSM (especially in the case of Czech Television), we took a closer look at how the participants perceive this concept, what they expect, and in what specific ways—according to some—the Czech PSM does not meet these expectations.

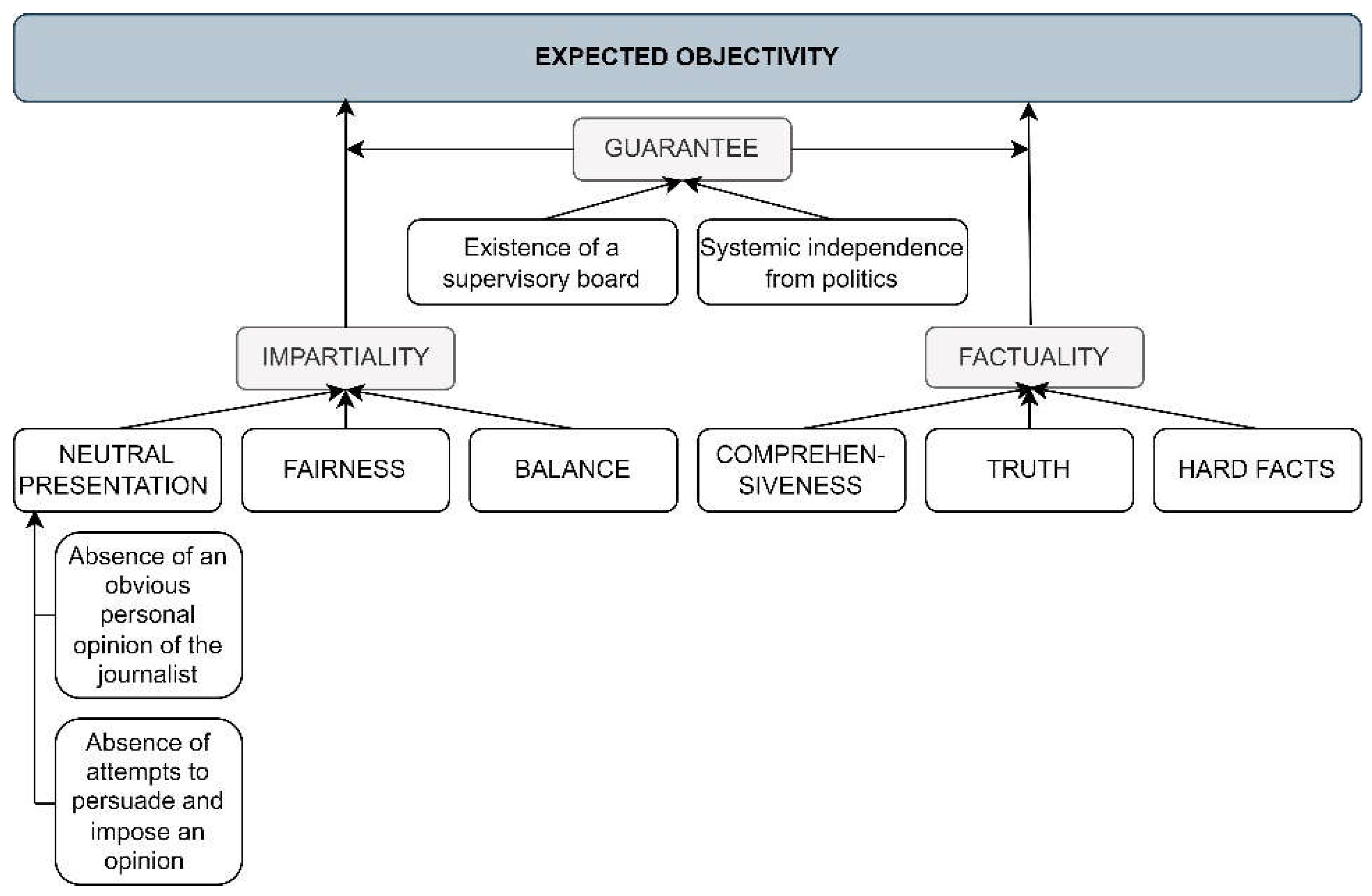

As summarized in

Figure 2, we distinguish between two key dimensions of expected objectivity: impartiality, which encompasses the aspects of neutral presentation, fairness, and balance; and factuality, which encompasses the aspects of comprehensiveness, truth, and hard facts. An additional layer involves ensuring compliance with the aforementioned principles through PSM supervisory boards and effective legal regulations that insulate PSM from political influence and ensure its independence. Again, these expectations, which are related to objectivity, encompass both prescriptive expectations (i.e., participants' explanations of how they perceive objectivity and their expectations from PSM in this regard) and cathectic expectations (i.e., the criteria participants used to assess the level of objectivity in Czech PSM; the reasons behind their high or low ratings).

Impartiality

Impartiality is a crucial part of objectivity for participants, with three distinct aspects. The first concerns the journalist-audience relationship, where the participants consider it essential that reporters and presenters deliver news in a neutral manner. This involves two levels: the absence of overt personal opinions from PSM staff and the absence of attempts to persuade or impose an opinion on the audience. In other words, the audience does not want to sense that they know what the PSM journalists think, nor do they want to feel that PSM journalists are trying to persuade them and impose their views upon them. It was the first of these two that was the most frequently criticized aspect of Czech PSM, particularly Czech Television, in the area of objectivity. Some participants expressed concerns that reporters and presenters at Czech Television "have their favorites", "have their own strong opinions", and that "some presenters exude a sense of who (...) they are rooting for and what their personal opinions are".

The second aspect of impartiality relates to fairness. This concerns the relationship between journalists and guests/sources. Public expectations include PSM journalists who treat all guests and sources equally, applying the same standard and fair approach to everyone. However, particularly in the case of Czech Television, some participants mentioned instances of perceived partisanship; favoritism toward particular politicians, parties, or views; and cases of harshness and criticism toward certain politicians or views, along with leniency shown to others.

The participants assess the level of fairness by observing cues, such as the extent of interruptions during interactions with different guests, the perceived aggressiveness of the questioning, and the (in)accuracy of the paraphrasing of what a guest had said. These cues, along with body language, also signal the personal views and attitudes of PSM journalists. Specific examples of topics where participants believe Czech PSM lacks impartiality include the COVID-19 pandemic, the war in Ukraine and Russian aggression, and domestic politics. Some participants agree that Czech Television, in particular, is siding with the current right-liberal government while being tougher on the current opposition parties, especially the ANO party of businessman and former Prime Minister Andrej Babiš.

The third aspect of impartiality is balance. This concerns the content and the representation of the guests and their opinions. The participants expect that all views and all sides of a dispute will be given space, and that this space will be balanced. Again, some participants criticized Czech Television for not meeting this expectation, describing it as homogeneous, one-sided, and lacking balance in terms of representing various views, with some views not getting the opportunity for expression. It is worth noting that some participants have a simplified perception of objectivity, equating it with a very mechanical notion of balance. One of them summarized it by saying: “For me, objectivity means presenting conflicting opinions—plus minus, minus plus—whatever. Just contradictory.” (Johana: female, 51-60 years old, tertiary education).

Factuality

Compared to impartiality, the second dimension of objectivity, factuality, received much less discussion. The participants expressed three main expectations in this regard: completeness of information (i.e., providing full and comprehensive information and not focusing solely on specific topics); truthfulness (i.e., ensuring factually correct and verified information); and an emphasis on hard facts (i.e., clearly distinguishing between facts and opinions, presenting only facts). While truthfulness is an important expectation in PSM content for participants, they often did not consider it as part of the concept of objectivity and discussed it separately.

Interestingly, some participants perceive objectivity as the presentation of mere facts, or “bare facts” as some called it, without any opinion or evaluation. This is also what they expect from PSM (without reflecting on the difference between news and interpretive genres). Two of them explained it in this way:

We all have the capacity of legal action. They [Czech PSM] just do not separate information from comments. Why should some guy or woman tell me what to think? I mean, [they should provide] just pure information, right?

[Tobias: male, 41-50 years old, tertiary education]

I expect it to be without an evaluation. And, also, not to use adjectives. That is already an evaluation and why [is that needed]? So, if it's supposed to be public service broadcasting, it's supposed to say what's going on, possibly provide multiple opinions, and let people make up their own minds ideally.

[Johana: female, 51-60 years old, tertiary education]

Discussion

Despite PSM being a relatively recent concept in the Czech Republic compared to Western countries (Czech Television and Czech Radio were established in 1992 as successors to what used to be state propaganda in the former socialist state), focus group discussions suggest that, over the past three decades, the Czech public has developed clear and detailed expectations regarding PSM and its services. Furthermore, this understanding aligns with the traditional normative conception of PSM's mission, roles, and tasks, as known from the Western countries (e.g., Cañedo et al., 2022; Council of Europe, 1994; UNESCO & World Radio and Television Council, 2001).

Another important message is that the participants mostly expressed their satisfaction with Czech PSM and strongly favored its continued operation. Thus, this study does not support the notion that, at least in the Czech case, the different history and legacy of PSM in Eastern Europe would lead to greater skepticism and less social consensus on its value, as suggested by Just et al. (2017). Also, voices advocating for limiting the mandate of PSM (e.g., to news, programs for minorities, and high culture), or even abolishing, it were rare. In general, the discussions suggest that the Czech public views the mission of PSM broadly, and their shared perception of PSM corresponds with a holistic, democracy-centric perspective, rather than the market-failure perspective (Donders, 2021).

While there was a broad consensus for the expectations of PSM, participants differed significantly in their actual assessments of the extent to which PSM meets these expectations, similar to the findings of the study on quality journalism by Karlsson and Clerwall (2019). Interestingly, unlike previous research (Campos Rueda, 2023; Smejkal et al., 2022) we observed no discernible patterns of difference in the assessment (satisfaction or criticism) of PSM performance among participants who support populist and non-populist parties, and non-voters. However, it is important to note that this may be attributed to the qualitative nature of this study, which serves as a research probe without making any claims to representativity.

Although participants have a clear understanding of what to expect from PSM, they were often not entirely familiar with how it operates. This observation coincides with the findings of an Austrian study, which discovered that young people's knowledge about legal requirements for PSM is shallow (Reiter et al., 2018). For example, a few participants mentioned that Czech PSM is tax-funded or that paying the license fee is compulsory in all circumstances (neither of which is true) or confused the content of PSM's broadcasts with those of commercial media (e.g., they accused PSM of broadcasting too much commercial programming, citing programs that are, in fact, broadcast by commercial media). Some also criticized Czech PSM for the lack of transparency and demanded the publication of reports on how it manages its allocated budget, unaware that this practice has been ongoing for a long time (annual activity reports and annual financial management reports dating back to 1997 are available on the websites of both Czech Television and Czech Radio). Consequently, it is evident that Czech PSM should communicate more intensively not only the value it brings to society but also the principles of its operation.

Another point worthy of note is the value participants placed on quality entertainment content. While scholars, policymakers, media regulators, and even PSM journalists (Urbániková, 2023), sometimes tend to think of PSM in a narrow way, focusing mainly on news and current affairs programs as the founding pillar, the discussions reveal that high-quality, diverse non-news content is vital for PSM's popularity and its strong position within the national media landscape. In short, the public expectations of PSM extend well beyond the realm of quality journalism. This also means that reducing the PSM remit to news and minority genres, in the spirit of the market-failure perspective (Donders, 2021), would very likely lead to audience dissatisfaction and perhaps even jeopardize the willingness to pay the license fee.

In the realm of PSM news content, this study affirms earlier research that indicated that the public's expectations for good journalism closely align with those held by journalists and experts (Gil de Zuniga & Hinsley, 2013; Karlsson & Clerwall, 2019; van der Wurff and Schoenbach, 2014). This study, in particular, underscores the significance of the expectation of PSM independence and the objectivity of PSM news content, the fulfilment of which significantly influences their overall assessment of PSM performance. This is not surprising, given that previous research has shown that perceived objectivity, impartiality, non-partisanship, and neutrality are key expectations from journalists and serve as a basis for their perceived trustworthiness (Karlsson & Clerwall, 2019; Ojala, 2021). In the specific case of PSM, the perceived freedom of PSM from political pressures strongly correlates with public trust in PSM (EBU, 2022). Failure to meet the expectation of objectivity was often the main reason for the criticism of PSM and negative attitudes towards it.

In line with Karlsson and Clerwall (2019), participants shared a strong expectation for objectivity, yet disagreed on its definition. Moreover, a deeper examination of what exactly people expect when they express the desire for objectivity reveals that expectations from certain parts of the public simply cannot be met. This is because their view of objectivity does not align with the usual understanding of journalistic objectivity (Skovsgaard et al., 2013; Westerstahl, 1983); it is simplistic and reductionist in three aspects that may or may not occur simultaneously.

First, some participants reduce objectivity to balance, or more precisely, to what Brüggemann and Engesser (2017) call a “false balance”. From this perspective, objectivity means covering all possible views and allocating them equal time, regardless of their relevance. If PSM fails to do so, part of the audience interprets it as one-sidedness, bias, or even censorship. Such an understanding, among other things, relegates journalists, whose profession includes verifying and evaluating the relevance of information and sources, to mere microphone holders.

The second form of reduction involves narrowing objectivity to the provision of hard facts, without opinion or evaluation, while simultaneously disregarding the distinction between news and interpretive genres. From this perspective, any analysis, interpretation, or commentary is viewed as impermissible sidetracking and improperly telling the audience what they should think. Such a conception of objectivity clashes with the fulfilment of the other roles of quality journalism and PSM as such (e.g., the provision of analysis and interpretation; Campos-Rueda & Goyanes, 2022) and the watchdog role (Trappel, 2010).

Third, in general, when participants discussed objectivity, they paid only minimal attention to the aspect of truth, which contrasts with the findings of the Swedish study by Karlsson and Clerwall (2019). This is not to say that they do not expect PSM news to be truthful; they just do not typically think of it as part of objectivity, as opposed to standard theoretical conceptions (Westerstahl, 1983). This view may (or may not) go hand in hand with the reduction of objectivity to balance: when the requirement of truthfulness is removed, or journalists are not deemed worthy or reliable to judge and verify information, their task is reduced to that of recording and reproducing opinions, regardless of their factual basis.

In summary, these reductionist views of objectivity share a distrust of journalists and an aversion to their authority. Part of the audience rejects them as filters for both relevant and irrelevant sources and information or as providers of analysis and commentary. This is, of course, not to imply that all criticisms of the lack of objectivity raised by the participants are necessarily invalid or illegitimate. However, the reductive perception of objectivity is problematic because, if PSM wants to fulfil its standard tasks and roles, the expectations of this part of the audience have to be disappointed, which then significantly influences the overall assessment of PSM performance.

Conclusion

Using data from 10 focus groups, our study addresses the research gap for the audience expectations of PSM (Campos-Rueda & Goyanes, 2022; Chivers & Allan, 2022; Just et al., 2017; Lestón-Huerta et al., 2021) and sheds light on the public's expectations from the PSM in the Czech Republic. It shows that the public expectations for PSM encompass four main dimensions: (1) the expected roles and functions that PSM is intended to perform (i.e., why PSM exists); (2) the general characteristics of PSM content (i.e., what PSM content should generally be like); (3) the principles of PSM operation (i.e., how PSM should operate); and (4) the specific requirements for both news and non-news PSM content.

Specifically, the discussions suggest that people perceive the role of PSM primarily as providing information, quality entertainment, and education, regardless of the audience figures. Thus, in line with the traditional perceptions of the role of PSM, Czech audiences expect all three elements of the Reithian triad (Reith, 1924)). Additionally, the role of PSM as an institution that should protect national values and promote national culture, both in terms of news and non-news content, has also emerged as an important expectation. This indicates that some segments of the public view PSM as a functional local counterweight to VOD platforms with globalized content, which may constitute one of the important arguments for its continued existence.

Drawing on Biddle's (1979) conceptual framework, this study takes a comprehensive approach to the exploration of the public expectations of PSM, considering not only prescriptive expectations but also cathectic and descriptive expectations. Based on the discussions, we argue that a focus on prescriptive expectations alone cannot fully capture what audiences expect from PSM. We contend that cathectic expectations, expressed through individual evaluations of PSM performance, are equally important because they reveal what individuals miss or value and which serve as their evaluation criteria. This approach unveils deeper wishes and needs, mitigating the risk of providing standard textbook answers to typical questions centered on prescriptive expectations.

While the participants were generally in agreement about the prescriptive expectations, we observed differences in two areas for the cathectic expectations. First, the people agreed that PSM should cater to everyone or, rather, that everyone should find in them content that aligns with their interests. However, a closer look at the evaluations of the current state of production reveals that not everyone finds what they expect. While some participants felt that the range of content and its format were sufficiently enjoyable and enriching, others deemed it outdated and unattractive, highlighting a large number of reruns and the neglect of topics that are important to young audiences.

Second, the participants paid significant attention to objectivity, which also emerged as the most frequent source of dissatisfaction. However, this dissatisfaction can often be explained by the various interpretations of objectivity and, at times, by a simplistic and reductionist understanding of this concept. Some reduce it to mere balance, others view objectivity as the provision of only bare facts, and many overlook the aspect of truthfulness. If PSM were to focus solely on balance, or neglecting factuality, they could inadvertently present conflicting viewpoints even in situations with a majority consensus (Gelbspan, 1998). To address these challenges and to prevent unintended bias, PSM could redefine objectivity as a rigorous method for testing information and a transparent approach to evidence (Kovach & Rosenstiel, 2001). They should also present information in the broadest context and produce news based on the weight of evidence (Brüggemann & Engesser, 2017).

This, naturally, is not to say that all complaints regarding the lack of objectivity of the Czech PSM were irrelevant. On the contrary, our findings suggest that PSM should strive for improvement, especially concerning neutral presentations (as some participants perceive discernible personal sympathies and antipathies among PSM journalists) and providing space for different views and opinions (as some participants feel that certain perspectives are excluded from PSM coverage).

Besides exploring audience expectations, future research should look deeper into the expectations and evaluations of PSM from the perspective of other stakeholders, particularly political actors (i.e., those who set the institutional framework for PSM), and PSM managers and journalists (i.e., those who interpret the concept of public service in practice). As suggested by Urbániková (2023), there may be, even among PSM managers and journalists, different understandings of the role of PSM, as well as varying interpretations of key normative standards, such as objectivity and independence. These differences can lead to serious conflicts that have the potential to weaken the legitimacy of PSM in the eyes of the public. While diverse opinions, attitudes, and expectations are natural in open societies, the stability and legitimacy of PSM largely depend on a society-wide consensus about their expected roles and functions, and, naturally, on the extent to which the media succeeds in meeting those expectations.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Funding

This work was supported by the Czech Science Foundation (Grant No. GA22–30563S).

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank all the research participants for their time, and Lucie Čejková, Lukáš Slavík, Iveta Jansová, Alžběta Cutáková, and Františka Pilařová for their help and assistance in conducting the focus group discussions.

Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Banjac, S. (2022). An Intersectional Approach to Exploring Audience Expectations of Journalism. Digital Journalism 10 (1), 128-147. [CrossRef]

- Biddle, B. (1979). Role Theory: Expectations, Identities and Behaviors. Academic Press.

- Blázquez, F. J. C., Cappello, M., Milla, J. T., Valais, S. (2022). Governance and independence of public service media. European Audiovisual Observatory: Strasbourg. https://rm.coe.int/iris-plus-2022en1-governance-and-independence-of-public-service-media/1680a59a76.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2022). Thematic analysis: A practical guide. Sage.

- Brüggemann, M., & Engesser, S. (2016). Beyond false balance: How interpretive journalism shapes media coverage of climate change. Global Environmental Change, 42, 58-67. [CrossRef]

- Campos Rueda, M. (2023). Explaining Expectations-Evaluation Discrepancies: The Role of Consumption and Populist Attitudes in Shaping Citizens’ Perceptions of PSM Performance. Journalism Practice. [CrossRef]

- Campos-Rueda, M., & Goyanes, M. (2022). Public service media for better democracies: Testing the role of perceptual and structural variables in shaping citizens’ evaluations of public television. Journalism. [CrossRef]

- Cañedo, A., Rodríguez-Castro, M., & López-Cepeda, A. M. (2022). Distilling the value of public service media: Towards a tenable conceptualisation in the European framework. European Journal of Communication, 37(6), 586-605. [CrossRef]

- Council of Europe. (1994). 4th European Ministerial Conference on Mass Media Policy, Prague, 7-8 December 1994, Resolution No. 1: The Future of Public Service Broadcasting.

- Donders, K. (2021). Public Service Media in Europe: Law, Theory and Practice. London and New York: Routledge.

- EBU. (2022). Trust in Public Service Media 2022. Geneve: European Broadcasting Union. https://www.ebu.ch/files/live/sites/ebu/files/Publications/MIS/login_only/market_insights/EBU-MIS-Trust_in_PSM_2022-Public.pdf.

- Fawzi, N., & Motthes, C. (2020). Perceptions of media performance: Expectation-evaluation discrepancies and their relationship with media-related and populist attitudes. Media & Communication, 8(3), 335-347. https://www.cogitatiopress.com/mediaandcommunication/article/view/3142.

- Gelbspan, R. (1998). The heat is on: The climate crisis, the cover-up, the prescription. Cambridge: Perseus Press.

- Gil de Zúñiga, H., & Hinsley, A. (2013). The Press Versus the Public. Journalism Studies, 14(6), 926-942. [CrossRef]

- Hanitzsch T., & Vos. T. P. (2017). Journalistic roles and the struggle over institutional identity: The discursive constitution of journalism. Communication Theory, 27(2), 115–135. [CrossRef]

- Heise, N., Loosen, W., Reimer, J. & Schmidt, J. (2014). Including the Audience. Comparing the Attitudes and Expectations of Journalists and Users Towards Participation in German TV News Journalism. Journalism Studies, 15 (4), 411–430. [CrossRef]

- Arriaza Ibarra, E. Nowak, & R. Kuhn (Eds.), Public Service Media in Europe; Holtz-Bacha, C. (2015). The role of Public Service Media in Nation-Building. In K. Arriaza Ibarra, E. Nowak, & R. Kuhn (Eds.), Public Service Media in Europe: A Comparative Approach. Routledge.

- Horz, Ch. (2014). Networking Citizens. Public Service Media and Audience Activism in Europe.In G. F. Lowe, H. Van den Bulck, K. Donders (eds.), Public Service Media in the Networked Society. Nordicom.

- Chivers, T., & Allan, S. (2022). A public value typology for public service broadcasting in the UK. Cultural Trends. [CrossRef]

- Jakubowicz, K. (2007). Public service broadcasting in the 21st century - What chance for a new beginning? In G. F. Lowe & J. Bardoel (Eds.), From public service broadcasting to public service media. Nordicom.

- Just, N., Büchi, M., & Latzer, M. (2017). A Blind Spot in Public Service Broadcasters’ Discovery of the Public: How the Public Values Public Service. International Journal of Communication, 11. 992–1011. http://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/6591.

- Karlsson, M., & Clerwall, C. (2019). Cornerstones in Journalism. Journalism Studies, 20(8), 1184-1199. [CrossRef]

- Kovach, B., & Rosenthiel, T. (2001). The Elements of Journalism: What News people Should Know and the Public Should Expect. Crown Publishers.

- Léston-Huerta, T., Goyanes, M., & Mazza, B. (2021). What Have We Learned about Public Service Broadcasting in the World? A Systematic Literature Review and Suggestions for Future Research. Revista Latina de Comunicacion Social, 65-88. [CrossRef]

- Loosen, W., Reimer, J., & Hölig, S. (2020). What Journalists Want and What They Ought to Do (In)Congruences Between Journalists’ Role Conceptions and Audiences’ Expectations. Journalism Studies, 21(12), 1744-1774. [CrossRef]

- Morgan, D. (2019). Basic and Advanced Focus Groups. Portland State University.

- Newman, N., Fletcher, R., Eddy, K., Robertson, C. T., & Nielsen, R. K. (2023). Reuters Institute Digital News Report. https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/2023-06/Digital_News_Report_2023.pdf.

- Ojala, M. (2021). Is the Age of Impartial Journalism Over? The Neutrality Principle and Audience (Dis)trust in Mainstream News. Journalism Studies, 22(15), 2042-2060. [CrossRef]

- Okamura, T. (2023). Okamura (SPD): Nevím, proč by se z peněz koncesionářů měla platit propaganda [Okamura (SPD): I don't know why the money of concessionaires should pay for propaganda]. Parlamentní listy. https://www.parlamentnilisty.cz/profily/Tomio-Okamura-13074/clanek/Nevim-proc-by-se-z-penez-koncesionaru-mela-platit-propaganda-130770.

- Peifer, J. T. (2018). Perceived News Media Importance: Developing and Validating a Measure for Personal Valuations of Normative Journalistic Functions. Communication Methods and Measures, 12(1), 55-79. [CrossRef]

- Picone, I., & Donders, K. (2020). Reach or Trust Optimisation? A Citizen Trust Analysis in the Flemish Public Broadcaster VRT. Media and Communication, 8(3), 348–358. https://www.cogitatiopress.com/mediaandcommunication/article/view/3172.

- Price, M., & Raboy, M. (2003). Public service broadcasting in transition: adocumentary reader. Kluwer Law International.

- Reiter, G., Gonser, N., Grammel, M., et al. (2018). Young Audiences and Their Valuation of Public Service Media. In G. Ferrell Lowe, H. van den Bulck, & K. Donders (Eds.), Public Service Media in the Networked Society: RIPE@2017 (pp. 211–226). Gothenburg: Nordicom.

- Reith, J. (1924). Broadcast Over Britain. London: Hodder and Stoughton.

- Riedl, A., & Eberl, M. (2020). Audience expectations of journalism: What’s politics got to do with it? Journalism, 23(8), 1682-1699. [CrossRef]

- Sehl, A. (2020). Public Service Media in a Digital Media Environment: Performance from an Audience Perspective. Media and Communication, 8(3), 359-372. [CrossRef]

- Sehl, A., Simon, F. M., & Schroeder, R. (2020). The populist campaigns against European public service media: Hot air or existential threat? International Communication Gazette, 8(3), 6-18. [CrossRef]

- Schulz, A., Levy, D., & Nielsen, R. K. (2019). Old, Educated, and Politically Diverse: The Audience of Public Service News. Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism. https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/our-research/old-educated-and-politically-diverse-audience-public-service-news.

- Schwaiger, L., Vogler, D., & Eisenegger, M. (2022). Change in News Access, Change in Expectations? How Young Social Media Users in Switzerland Evaluate the Functions and Quality of News. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 27(3), 609-628. [CrossRef]

- Skovsgaard, M., Albæk, E., & Bro, P. (2012). A reality check: How journalists’ role perceptions impact their implementation of the objectivity norm. Journalism. [CrossRef]

- Smejkal, K., Macek, J., Slavík, L., & Šerek, J. (2022). “Just a “Mouthpiece of Biased Elites?” Populist Party Sympathizers and Trust in Czech Public Service Media.” The International Journal of Press/Politics. [CrossRef]

- Steppat, D., Castro Herrero, L., & Esser, F. (2020). News Media Performance Evaluated by National Audiences: How Media Environments and User Preferences Matter. Media and Communication, 8(3), 321-334. [CrossRef]

- Swart, J., Kormelink, T. G., Costera Meijer, I., & Broersma, M. (2022). Advancing a Radical Audience Turn in Journalism. Fundamental Dilemmas for Journalism Studies. Digital Journalism, 10(1), 8-22. [CrossRef]

- Syvertsen, T. (2003). Challenges to Public Television in the Era of Convergence and Commercialization. Television & New Media, 4(2), 155-17. [CrossRef]

- Štětka, V. (2022). Digital News Report 2020: Czech Republic. In N. Newman, R. Fletcher, C. T. Robertson, K. Eddy, R. K. Nielsen (Eds.), Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2023. Oxford: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism.

- Štětka, V. (2023). “Digital News Report 2023: Czech Republic.” In Newman, N., Fletcher, R., Eddy, K., Robertson, C. T., & Nielsen, R. K. (Eds.), Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2023. Oxford: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism.

- Trappel, J. (2010). The Public's Choice: How Deregulation, Commercialisation, and Media Concentration Could Strengthen Public Service Media. In G. F. Lowe (Ed.), The Public in Public Service Media (pp. 39-51). Göteborg: Nordicom.

- Tsfati, Y., Meyers, O., & Peri, Y. (2006). What is Good Journalism? Comparing Israeli Public and Journalists’ perspectives. Journalism, 7 (2), 152–173. [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. (2001). Public Broadcasting Why? How? Paris: UNESCO. http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0012/001240/124058eo.pdf.

- Urbániková, M. (2023). Arguing About the Essence of Public Service in Public Service Media: A Case Study of a Newsroom Conflict at Slovak RTVS. Journalism Studies, 24(10), 1352-1374. [CrossRef]

- Urbániková, M., & Smejkal, K. (2023). Trust and Distrust in Public Service Media: A Case Study from the Czech Republic. Media and Communication, 11(4), 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Van Der Wurff, R., & Schoenbach, K. (2014). Civic and Citizen Demands of News Media and Journalists: What Does the Audience Expect from Good. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 91 (3), 433–451. [CrossRef]

- Vos, Tim P., Eichholz. M., & Karaliova, T. (2019). Audiences and Journalistic Capital. Journalism Studies, 20 (7), 1009-1027. [CrossRef]

- Wahl-Jorgensen, K., Berry, M., Garcia-Blanco, I., Bennett, L., & Cable, J. (2017). Rethinking balance and impartiality in journalism? How the BBC attempted and failed to change the paradigm. Journalism, 18(7), 781-800. [CrossRef]

- Westerståhl, J. (1983). OBJECTIVE NEWS REPORTING: General Premises. Communication Research. 10(3), 403 – 424. [CrossRef]

- Willnat, L., Weaver, D. H., & Wilhoit, G. C. (2019). The American Journalist in the Digital Age. Journalism Studies, 20 (3), 423–441. [CrossRef]

Short Biography of Authors

Klára Smejkal is a junior researcher and PhD candidate at the Department of Media Studies and Journalism, Masaryk University, Czech Republic. Her doctoral research focuses on the audience perception of public service media. She is mainly interested in the trust in public service media and the links between political polarization, populism, and audience expectations. ORCID:

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9391-6357.

Marína Urbániková is an assistant professor at the Department of Media Studies and Journalism, Masaryk University, Czech Republic. Her research interests include public service media and its independence, journalistic autonomy, the security and safety of journalists, and gender and journalism. She is currently the principal investigator for the project Rethinking the Role of Czech Public Service Media: Expectations, Challenges, and Opportunities (2021–2024), which is supported by the Czech Science Foundation. She also authors reports on Slovakia as part of the Media Pluralism Monitor project, which is funded by the European Commission. ORCID:

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1640-9823.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).