Introduction

Stress hyperglycemia (SH) is defined as a transitory increase in the blood glucose level that occurs in critically ill patients in intensive care units [

1,

2,

3,

4]. As a stress state, acute myocardial infarction (AMI) can lead to stress hyperglycemia [

2,

3]. It has been reported that around 20% – 50% of the patients with AMI and without diabetes mellitus (DM) exhibit acute hyperglycemia in response to physiological stress [

5,

6,

7]. Previous studies have shown that hyperglycemia is associated with a poorer short-term prognosis in patients with AMI irrespective of their diabetic status [

1,

2,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16]. There are data confirming that acute (stress) hyperglycemia in patients without DM has a worse prognostic impact after AMI (mortality and/or other adverse events), as compared to the prognostic impact of DM itself, which indicates that acute fluctuations in blood sugar levels are prognostically less favorable, as compared to chronically elevated values [

16]. SH is also a predictor of the slow-flow/no-reflow phenomenon in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) [

8,

17], as well as a risk factor for stent thrombosis in these patients [

6,

7,

11].

Many studies published so far have dealt with the prognostic impact of hyperglycemia in patients with AMI, i.e., patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) with different access to revascularization therapy [

8]. The prognostic significance of SH in both diabetic and nondiabetic patients was analyzed [

13], but the definition of SH in diabetic patients and the relationship between diabetes mellitus and SH, remain controversial.

Primary percutaneous coronary intervention (pPCI) is the recommended and most effective therapeutic option in patients with STEMI. Studies have shown that successful angiographic reperfusion, which is defined as TIMI grade 3 flow through the infarct-related artery (IRA) is associated with good short- and long-term outcomes [

18]. However, despite timely and successful reperfusion, some STEMI patients still have a high risk of adverse events because a certain amount of myocardial necrosis is inevitable. Therefore, it is necessary to define additional prognostic parameters in patients with STEMI who have undergone successful pPCI. To the best of our knowledge, the prognostic significance of SH in non-diabetic STEMI patients treated successfully with pPCI has not been analyzed so far.

The present study aims to analyze the impact of SH at admission on the incidence of all-cause mortality and major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) in short and long-term follow-up (up to eight years), in STEMI patients without DM who have been treated successfully with primary PCI.

Materials and Methods

Study Population, Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria, Data Collection, and Definitions

The present study enrolled 2,362 consecutive patients hospitalized between December 2005 and January 2012, registered in the prospective University Clinical Center of Serbia STEMI Register. The purpose of the prospective University Clinical Center of Serbia STEMI Register has been published elsewhere [

19]. The objective of the Register is to gather data on the management and short- and long-term outcomes of patients with STEMI, treated with primary PCI. All consecutive STEMI patients, aged 18 or older, who were admitted to the Coronary Care Unit after being treated with pPCI in the Catheterization Lab of the Center, were included in the Register. All the patients included received written information about their participation in the Register and the long-term follow-up, and their verbal and written consent was obtained [

19].

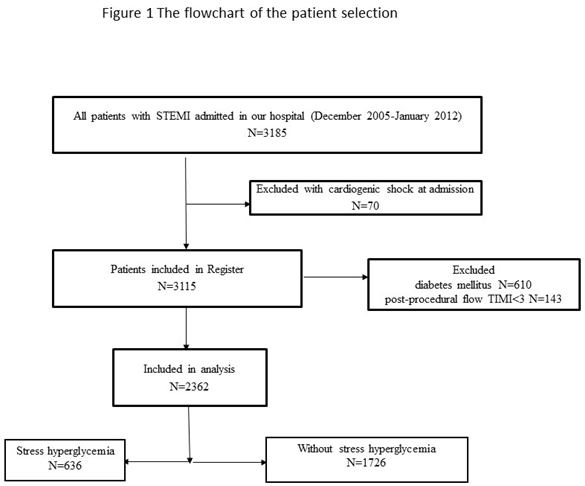

Patients with cardiogenic shock at admission were excluded from the Register. For the purpose of this study, we excluded: 1) patients with DM – patients with previous DM (according to medical history, patients on current antidiabetic therapy), as well as patients with new-onset DM diagnosed during hospitalization, and 2) patients with postprocedural TIMI 0, 1, 2 flow through the infarct-related artery (IRA). The flowchart of patient selection is presented in Figure 1.

Coronary angiography was performed via the femoral approach. Primary PCI and stenting of the IRA were performed using the standard technique. Loading doses of aspirin (300 mg) and clopidogrel (600 mg) were administered to all patients before pPCI. Selected patients were also given the GP IIb/IIIa receptor inhibitor during the procedure. After pPCI, patients were treated according to the current guidelines.

Demographic, baseline clinical, laboratory, angiographic, and procedural data were collected and analyzed. Blood samples for laboratory analyses were taken at hospital admission, before pPCI. SH at hospital admission (and before pPCI) was defined as a plasma glucose level higher than 7.8 mmol/l [

20]. An echocardiographic examination was performed in the first three days after the intervention (pPCI). The left ventricular ejection fraction (EF) was assessed according to the biplane method. We classified EF as preserved (EF ≥ 50%), moderately reduced (EF 40 – 49%), and reduced (EF < 40%). Baseline kidney function (at admission) was assessed using the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease equation, and the value of estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) below 60 ml/min/m

2 was considered as reduced kidney function.

Patients were followed up at eight years after their enrolment in the Register. Follow-up data were obtained through telephone interviews and during outpatient visits. We analyzed all-cause mortality and the composite endpoint – major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE), which included cardiovascular death, non-fatal reinfarction, non-fatal ischemic stroke, and target vessel revascularization (TVR). The cause of death in patients was obtained from death certificates or discharge forms (if the patient was hospitalized). Cardiovascular death included any death due to a proximate cardiac cause (myocardial infarction, low-output heart failure, fatal arrhythmia, sudden death), and death caused by non-coronary vascular causes, such as cerebrovascular disease [

19]. Non-fatal recurrent myocardial infarction was defined according to the Fourth Universal Definition for Myocardial Infarction [

21]. TVR was defined as ischemia-driven percutaneous revascularization of the target vessel performed for restenosis or other complications. Stroke was defined as a new onset of focal or global neurological deficit lasting more than 24 hours. Computed tomography (CT) was used to diagnose (ischemic) stroke. The Emergency Center neurologist was responsible for the diagnosis and treatment of stroke [

19].

Ethics

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Belgrade Faculty of Medicine (approval number 470/II-4, February 21, 2008). The study was conducted in keeping with the principles outlined in the Helsinki Declaration. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients for their participation in the Register.

Statistical Analysis

Categorical variables were expressed as frequency and percentages, and continuous variables were expressed as the median (med), with 25th and 75th quartiles (IQR). Analysis for normality of data was performed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Baseline differences between groups were analyzed using the Mann-Whitney test for continuous variables, and the Pearson χ² test for categorical variables. The Kaplan-Meier method was used for constructing the probability curves for eight-year mortality and the incidence of MACE, while the difference between patients with and without SH was tested with the Log-Rank test. The Cox proportional hazard model (backward method, with p < 0.10 for entrance into the model) was used to identify univariable and multivariable predictors for the occurrence of all-cause mortality and MACE. Two-tailed p values of less than < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. We used Version 19 of the SPSS statistical software for statistical analysis (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL).

Results

Of the 2,362 patients analyzed, 636 (26.9%) patients had SH at admission. The mean age of all analyzed patients was 58 (51, 67) years, with 602 (25.5%) patients being female.

As compared with patients with non-SH, patients with SH were older; they presented more often with heart failure, atrial fibrillation, and complete atrioventricular block; they were more likely to have reduced kidney function at admission (eGFR < 60 ml/min/m

2), multivessel coronary artery disease on initial angiogram, and pre-procedural TIMI grade 0 flow through the IRA. Procedural characteristics did not differ among the analyzed groups. Pre-discharge EF was significantly lower in patients with SH. Baseline characteristics, laboratory, angiographic, and procedural characteristics, in-hospital mortality, and therapy at discharge, in patients with and without premature SH, are presented in

Table 1.

At eight-year follow-up, all-cause mortality and MACE were registered in a total of 139 (5.9%) patients and 263 (11.1%) patients, respectively. Causes of mortality were predominantly cardiovascular; noncardiovascular causes of death (such as cancer, ileus, pneumonia, and dementia) were registered in a total of 15 patients (10.8% of all deaths).

Patients with SH had higher all-cause mortality and lower composite endpoint MACE. Non-fatal recurrent infarction was related to a new lesion site in 20 (54%) patients with SH at admission and in 29 (42.7%) patients with non-SH, p = 0.001.

All-cause mortality and MACE in patients with and without SH are presented in

Table 2.

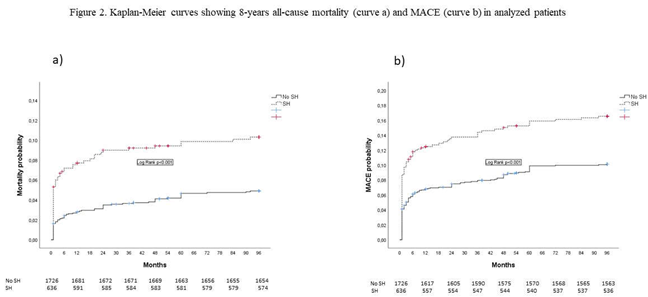

Kaplan Meier curves showing eight-year all-cause mortality (curve a) and MACE (curve b) are presented in Figure 2.

After adjustment for confounders, SH at admission was an independent predictor of all-cause mortality and MACE in short-term and long-term follow-up. Predictors for the occurrence of short and long-term mortality and MACE are presented in

Table 3 and

Table 4.

Discussion

Our results showed that more than a ¼ of STEMI patients without DM had SH at admission. During eight-year follow-up, mortality and composite endpoint MACE were significantly higher in these patients, as compared to patients without SH, but the incidence of non-fatal recurrent ischemic events was not significantly different between these two groups of patients. The cause of non-fatal recurrent myocardial infarction in patients with SH at admission was predominantly the development of new lesion sites. SH at admission was an independent predictor of short and long-term mortality and composite end-point MACE, and its negative prognostic impact was stronger in short-term follow-up.

Baseline Characteristics of the Analyzed Patients and the Incidence of SH

Baseline characteristics and the incidence of SH in our patients are in keeping with data found in literature, which states that the incidence of SH ranges from 20% - 50%, depending on the analyzed population and the glycemic value by which SH is defined [

1,

3,

6,

8,

22,

23]. In a study by Khalfallah et al., SH at any time during hospitalization (the glycemia level was defined in the same way as in our study) was registered in 16.8% of all analyzed STEMI and non-diabetic patients, while in the study by Ekmekci et al., wherein STEMI patients treated with pPCI were also included, the incidence of hyperglycemia higher than 118 mg/dl at admission was registered in more than 50% of patients [

24]. It should be noted, however, that this study also included patients with DM. In the study by Nakamura et al., hyperglycemia > 11.1 mmol/L was registered in 31% of patients with STEMI, and in 15% of non-diabetic patients [

25].

Prognostic Impact of SH

Regarding the prognostic influence of SH in patients with AMI, the question can be raised as to whether it is a true independent indicator of adverse events or just a marker of high-risk AMI [

8]. In support of the independent prognostic influence of hyperglycemia are the findings of a large number of studies whose results show that SH is an independent predictor of mortality and/or other adverse events independently of the presence of DM in patients with ACS in general, but also in patients with AMI with non-obstructive coronary artery disease (MINOCA) [

1,

2,

6,

12,

14,

24,

26,

27,

28]. Data on the negative prognostic impact of SH in STEMI patients are primarily found in studies from the thrombolytic era but are also reported in studies conducted in the era of pPCI. The results of these studies have shown that hyperglycemia (defined by different cut-off values: > 6.1 mmol/l or even > 11.1 mmol/l) is a strong independent predictor of mortality, i.e. the occurrence of MACEs after STEMI in non-diabetic patients, and the independent and negative prognostic impact of SH is the strongest in short-term follow-up [

5]. This finding is explained by the fact that in non-diabetic patients, SH is a transient disorder of glycoregulation, which gets back to normal after the acute phase of the disease (infarction) passes. Therefore, the negative impact of SH weakens in long-term follow-up. Our results are consistent with these findings but show that the impact of SH at admission persists for up to eight years of follow-up.

In a study by Eitel et al., hyperglycemia was found to be an independent predictor of MACE in patients with STEMI who were treated with pPCI. It was also found that the risk of MACE starts to increase with glycemic values above 7.8 mmol/l, in non-diabetic patients (which is in keeping with our findings), while in patients with diabetes, the risk of the occurrence of MACE starts to increase when the glycemic value is higher than 11.1 mmol/l [

7].

In the study by Khalfallah et al., which included patients with STEMI treated with pPCI, it was found that SH in non-diabetic patients was an independent predictor of three-month mortality. Also, in this study there was no difference in the incidence of non-fatal reinfarction and stroke, which is identical to our findings [

1]. Unlike our study, this study also included patients with the slow-flow/no-reflow phenomenon, but this did not affect the findings – in addition to post-procedural TIMI 0 - 2 flow, SH was also an independent predictor of mortality in three-month follow-up [

1].

In a study by Ekmekci et al., the prognostic impact of hyperglycemia at admission on in-hospital occurrence of MACE (cardiovascular mortality, reinfarction, and repeat TVR) was analyzed in patients with STEMI treated with pPCI. In this study, the highest in-hospital mortality was registered in the group of patients with a glycemia level higher than 145 mg/dl. The incidence of reinfarction and ITVR was significantly higher in the group with a glycemia level higher than 145 mg/dl, as compared to the group with a glycemia level lower than 118 mg/dl [

24]. The difference in the incidence of MACE is predominantly due to higher mortality, while there was no difference in the incidence of reinfarction and target vessel revascularization. Also, in the cited study, it was found, in multivariate logistic regression, that a glycemia level higher than 145 mg/dl was a strong independent predictor of in-hospital mortality [

24].

In a study by Wei et al., it was found that a higher fasting blood glucose level had an adverse prognostic impact on the occurrence of composite MACE during hospitalization and during one-year follow-up of patients with STEMI treated by pPCI and patients with NSTEMI who had undergone early PCI [

2]. In contrast to our study, in this study, both patients with DM and non-diabetic patients were analyzed, and fasting blood glucose levels were analyzed, while in our study the glycemia level was analyzed only at admission, before myocardial revascularization.

In the study by Stalikas et al., wherein 309 patients with STEMI were included, it was found that the glycemic value at admission was independently associated with an increased risk of the occurrence of adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events during an average follow-up period of 1.7 years [

29].

It should be noted that there is a somewhat smaller number of studies whose results show that the negative prognostic impact of SH (defined by different cut-off values) after AMI exists only in patients with DM, and not in patients without DM. In a study by Ferreira et al., it was found that in patients with STEMI, hyperglycemia > 213 mg/dl at admission had a negative prognostic impact on twelve-year mortality only in patients with diabetes, while the prognosis of patients with DM and a glycemia level of < 213 mg/dl at admission, as well as the prognosis of non-diabetic patients with a glycemia level of > 143 mg/dl at admission and of non-diabetic patients without hyperglycemia at admission did not differ [

8]. A study by Kumar et al. had a similar finding establishing that acute hyperglycemia in patients without DM is not an independent predictor of in-hospital mortality, rather that it is the case only with hyperglycemia in patients with DM [

6].

Possible Mechanisms of Adverse Impact of SH in Patients with AMI

The prognostic impact of SH in patients with STEMI is complex and may be direct or indirect. One of the possible indirect effects is that SH is an independent predictor of the slow-flow/no-reflow phenomenon through the IRA [

1,

17,

30]. This is why we decided to include only patients with postprocedural TIMI 3 flow in our analysis, which eliminated the strong negative prognostic impact of poor TIMI flow in our patients.

Other possible direct mechanisms of the prognostic impact of SH may be the consequence of the acute release of catecholamines, cytokines, cortisol, etc., thus leading to oxidative stress, endothelial dysfunction, inflammation, apoptosis, and the state of hypercoagulability, which can affect the size of the infarction despite a good TIMI flow through the IRA [

1,

2,

3,

4,

6,

7,

12,

14,

15,

17].

The pro-inflammatory state in the body in non-diabetic patients further destabilizes insulin secretion and reinforces insulin resistance, which, in turn, further increases blood glucose levels [

30]. Some authors have stated that an acute increase in the blood glucose level is more harmful than a chronically elevated glucose level [

17], i.e., that the inflammatory response of the body is much more pronounced in nondiabetic patients than in diabetic patients [

15]. The negative prognostic impact of SH is believed to be ‘masked’ in patients with DM because the presence of DM itself negatively affects the prognosis after AMI [

15,

16]. In support of these findings are the results of a large substudy of the HORIZONS-AMI trial wherein 3,405 patients with STEMI were treated with pPCI and where acute hyperglycemia was found to be strongly associated with mortality in nondiabetic patients, and this association was found to be stronger, i.e., more pronounced as compared to the association between hyperglycemia and mortality in patients with DM [

31].

Clinical Implications

The results of our study can add to existing knowledge regarding the prognostic impact of SH in non-diabetic patients with STEMI, who were treated with primary PCI. Our findings underscore the importance of determining the blood glucose level in every patient with STEMI regardless of their diabetic status. Given that glucose levels are tested routinely and that this is a cheap and readily available testing method, knowing the negative impact of SH can, together with other well-known predictors of poor prognosis after STEMI, provide additional help in risk stratification in these patients.

Study Limitations

Several limitations to our study should be mentioned. The study is unicentric and observational, but it is controlled, prospective, and has included consecutive patients, limiting possible selection bias. Patients included in the study were hospitalized between 2005 and 2012. Patients with cardiogenic shock at admission were excluded from our Register. All patients were treated with clopidogrel. There were no patients treated with more recently developed antiplatelet drugs (ticagrelor and prasugrel were not available for routine administration to patients at the time of their entry into the Register). This may have influenced the patients’ prognosis, i.e. reduced the occurrence of cardiovascular mortality or the incidence of non-fatal ischemic events. Coronary angiography and concomitant PCI were performed via the femoral approach. The radial approach was not used in routine clinical practice at the time when the patients were enrolled into the Register. We analyzed only the glycemia level at admission and we were unable to consider the content and time of the last meal before collecting the blood sample. We did not analyze the SH ratio because we did not determine HgA1c in every patient without DM. However, HgA1c is not a routine laboratory assessment for STEMI patients (especially without DM) in most clinical setups, while testing the blood glucose level is easy to perform and is a routine laboratory test carried out before pPCI in emergency departments [

6]. On the other hand, data can be found in literature stating that the area under the curve for the stress hyperglycemia ratio (SHR) is somewhat lower for predicting intrahospital death in patients with STEMI (AUC = 0.675; (95%CI 0.598-0.752)) [

30], while the area under the curve (AUC) for random glucose level is 0.789 (0.759 – 0.816) for predicting in-hospital death [

26]. The study was not designed to evaluate whether changing pharmacological treatment during follow-up would have an impact on long-term outcomes in the analyzed patients.

Conclusion

A significant number of STEMI patients without DM had SH at admission. Non-diabetic patients with SH at admission had higher eight-year all-cause mortality and composite end-point MACE. The incidence of non-fatal adverse ischemic events did not differ between patients with SH and those without SH. Despite successful revascularization, SH at admission was an independent predictor of short-term and long-term (up to eight years) all-cause mortality and MACE along with other well-known and significant predictors such as older age, Killip class > 1, EF, and reduced eGFR. This finding emphasizes the importance of close glucose level monitoring in all patients with STEMI regardless of their diabetic status, in order to better identify high-risk patients.

Disclosure statement: The authors report that there are no competing interests to declare.

Acknowledgments: The authors would like to express their gratitude to the physicians and nurses of the Coronary Unit and the Catheterization Laboratory who participated in the primary PCI program.

Author Contributions

LS and IM devised the study and participated in its design, acquisition of data, and coordination. LS performed statistical analysis. MA, SS, GK, RL, DM, and DS participated in the design of the study and helped draft the manuscript. All the authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Belgrade, Faculty of Medicine (approval number 470/II-4, February 21, 2008).

References

- Khalfallah M, Abdelmageed R, Elgendy E, Hafez YM. Incidence, predictors and outcomes of stress hyperglycemia in patients with ST elevation myocardial infarction undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Diab Vasc Dis Res 2020 Jan-Feb;17(1):1479164119883983. [CrossRef]

- Wei QC, Chen YW, Gao QY, Ren KD, Liu YB, He F, et al. Association of stress hyperglycemia with clinical outcomes in patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: a cohort study. Cardiovasc Diabetol 2023 Apr 12;22(1):85. [CrossRef]

- Cinar H, Avci A, Gulen M, Avci BS, Comertpay E, Satar S. Does stress hyperglycemia affect mortality? Acute myocardial infarction - case control study. Arch Med Sci Atheroscler Dis 2019 Aug 14;4:e201-e207. [CrossRef]

- Sun C, Zhou JH, Huang YL, Ning YL, Xu XH. The optimal blood glucose is significantly associated with lower mortality in critically ill patients with cardiogenic shock: an analysis revealed with time series blood glucose records. Eur J Med Res 2024 Feb 17;29(1):129. [CrossRef]

- Wei F, Han W. Effect of stress hyperglycemia on the clinical prognosis of patients with acute myocardial infarction undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. Minerva Pediatr (Torino) 2023;75(4):620-21. [CrossRef]

- Kumar R, Ammar A, Kumar A, Ali A, Talpur MFH, Rahooja K, et al. Acute hyperglycemia, a rabble-rouser or innocent bystander? A prospective analysis of clinical implications of acute hyperglycemia in STE-ACS patients. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 2023 Aug 18;23(1):406. [CrossRef]

- Eitel I, Hintze S, de Waha S, Fuernau G, Lurz P, Desch S, et al. Prognostic impact of hyperglycemia in nondiabetic and diabetic patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction: insights from contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2012;5(6):708-18.

- Ferreira JA, Baptista RM, Monteiro SR, Gonçalves FM, Monteiro PF, Gonçalves LM. Admission hyperglycemia and all-cause mortality in diabetic and non-diabetic patients with acute myocardial infarction: a tertiary center analysis. Intern Emerg Med 2021;16(8):2109-19.

- Angeli F, Reboldi G, Poltronieri C, Lazzari L, Sordi M, Garofoli M,et al. Hyperglycemia in acute coronary syndromes: from mechanisms to prognostic implications. Ther Adv Cardiovasc Dis 2015;9(6):412-24.

- Singh K, Hibbert B, Singh B, Carson K, Premaratne M, Le May M, et sl. Meta-analysis of admission hyperglycaemia in acute myocardial infarction patients treated with primary angioplasty: a cause or a marker of mortality?, European Heart Journal - Cardiovascular Pharmacotherapy 2015;1(4):220–8. [CrossRef]

- Zhang JW, Zhou YJ, Cao SJ, Yang Q, Yang SW, Nie B. Impact of stress hyperglycemia on in-hospital stent thrombosis and prognosis in nondiabetic patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction undergoing a primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Coron Artery Dis 2013;24(5):352-6. [CrossRef]

- Abdu FA, Galip J, Qi P, Zhang W, Mohammed AQ, Liu L, et al. Association of stress hyperglycemia ratio and poor long-term prognosis in patients with myocardial infarction with non-obstructive coronary arteries. Cardiovasc Diabetol 2023 Jan 16;22(1):11. [CrossRef]

- Zeng G, Song Y, Zhang Z, Xu J, Liu Z, Tang X, et al. Stress hyperglycemia ratio and long-term prognosis in patients with acute coronary syndrome: A multicenter, nationwide study. J Diabetes 2023;15(7):557-68.

- Yang J, Zheng Y, Li C, Gao J, Meng X, Zhang K, et al. The Impact of the Stress Hyperglycemia Ratio on Short-term and Long-term Poor Prognosis in Patients With Acute Coronary Syndrome: Insight From a Large Cohort Study in Asia. Diabetes Care 2022;45(4):947-56. [CrossRef]

- Guo W, Zhu J, Liu W. Stress hyperglycemia ratio: an independent predictor for in-hospital major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events in patients with st-segment elevation myocardial infarction. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 2023 Apr 15;23(1):195. [CrossRef]

- Kojima T, Hikoso S, Nakatani D, Suna S, Dohi T, Mizuno H, et al. Impact of Hyperglycemia on Long-Term Outcome in Patients With ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction. Am J Cardiol 2020;125(6):851-9. [CrossRef]

- Khalfallah M, Maria DA, Allaithy A. Impact of Stress Hyperglycemia on No-Reflow Phenomenon in Patients with ST Elevation Myocardial Infarction Undergoing Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. Glob Heart 2022 Mar 29;17(1):23. [CrossRef]

- Mehta RH, Harjai KJ, Cox D, Stone GW, Brodie B, Boura J, et al. Primary Angioplasty in Myocardial Infarction (PAMI) Investigators. Clinical and angiographic correlates and outcomes of suboptimal coronary flow inpatients with acute myocardial infarction undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention. J Am Coll Cardiol 2003;42(10):1739-46. [CrossRef]

- Mrdovic I. Savic L, Lasica R, Krljanac G, Asanin M, Brdar N et al. Efficacy and safety of tirofiban-supported primary percutaneous coronary intervention in patients pretreated with 600 mg clopidogrel: Results of propensity analysis using the clinical center of serbia STEMI register. Eur. Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care 2014;3:56–66. [CrossRef]

- American Diabetes Association. 2. Classification and Diagnosis of Diabetes: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes-2019. Diabetes Care 2019;42(Suppl 1):S13-S28.

- Thygesen K, Alpert J.S, Jaffe AS, Chaitman BR, Bax JJ, Morrow DA, White HD.; ESC Scientific Document Group. Fourth universal definition of myocardial infarction (2018). Eur. Heart J 2019;40;237–69.

- Capes SE, Hunt D, Malmberg K, Gerstein HC. Stress hyperglycaemia and increased risk of death after myocardial infarction in patients with and without diabetes: a systematic overview. Lancet 2000;355(9206):773-8. [CrossRef]

- Wahab NN, Cowden EA, Pearce NJ, Gardner MJ, Merry H, Cox JL; ICONS Investigators. Is blood glucose an independent predictor of mortality in acute myocardial infarction in the thrombolytic era? J Am Coll Cardiol 2002;40(10):1748-54.

- Ekmekci A, Cicek G, Uluganyan M, Gungor B, Osman F, Ozcan KS, et al. Admission hyperglycemia predicts inhospital mortality and major adverse cardiac events after primary percutaneous coronary intervention in patients without diabetes mellitus. Angiology 2014;65(2):154-9. [CrossRef]

- Nakamura T, Ako J, Kadowaki T, Funayama H, Sugawara Y, Kubo N, et al. Impact of acute hyperglycemia during primary stent implantation in patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction. J Cardiol 2009;53(2):272-7. [CrossRef]

- Qin Y, Yan G, Qiao Y, Wang D, Luo E, Hou J, et al. Predictive value of random blood glucose versus fasting blood glucose on in-hospital adverse events in patients with ST-segment elevation acute myocardial infarction. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 2020 Feb 27;20(1):95. [CrossRef]

- Hoebers LP, Damman P, Claessen BE, Vis MM, Baan J Jr, van Straalen JP, et al. Predictive value of plasma glucose level on admission for short and long term mortality in patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction treated with primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Am J Cardiol. 2012;109(1):53-9. [CrossRef]

- Yang Y, Kim TH, Yoon KH, Chung WS, Ahn Y, Jeong MH, et al. The stress hyperglycemia ratio, an index of relative hyperglycemia, as a predictor of clinical outcomes after percutaneous coronary intervention. Int J Cardiol 2017;241:57-63. [CrossRef]

- Stalikas N, Papazoglou AS, Karagiannidis E, Panteris E, Moysidis D, Daios S, et al. Association of stress induced hyperglycemia with angiographic findings and clinical outcomes in patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Cardiovasc Diabetol 2022 Jul 26;21(1):140. [CrossRef]

- Liao W, Chen Y, Gao Q, Gan R, Li M, Liu Z, et al. Impact of stress hyperglycemia ratio, derived from glycated albumin or hemoglobin A1c, on mortality among ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction patients. Cardiovasc Diabetol 2023 Dec 6;22(1):334. [CrossRef]

- Planer D, Witzenbichler B, Guagliumi G, Peruga JZ, Brodie BR, Xu K, et al. Impact of hyperglycemia in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: the HORIZONS-AMI trial. Int J Cardiol 2013;167(6):2572-9. [CrossRef]

Table 1.

Baseline clinical, laboratory, angiographic, procedural characteristics, therapy at discharge, and in-hospital mortality of the patients enrolled in the study.

Table 1.

Baseline clinical, laboratory, angiographic, procedural characteristics, therapy at discharge, and in-hospital mortality of the patients enrolled in the study.

| Characteristics |

SH

N= 636 |

No SH

N= 1726 |

P value

|

| Age, years med(IQR) |

62(53, 72), |

58(50, 66) |

<0.001 |

| Female, n(%) |

195(30.6) |

402(23.3) |

<0.001 |

| BMI, med (IQR) |

26.3(24.1, 29.2) |

26.1(24.4, 28.9) |

0.175 |

| Previous MI, n(%) |

51(8.1) |

159(9.2) |

0.366 |

| Previous angina, n(%) |

48(7.6) |

106(6.1) |

0.226 |

| Previous stroke, n(%) |

22(3.5) |

48(2.9) |

0.729 |

| Hypertension, n(%) |

422(66.4) |

1070(62) |

0.122 |

| HLP, n(%) |

368(57.9) |

1054(61.1) |

0.125 |

| Smoking, n(%) |

333(52.4) |

1051(60.9) |

<0.001 |

| Family hystory, n(%) |

209(32.9) |

620(35.9) |

0.167 |

| Pain duration, hours med(IQR) |

2.5(1.5, 4.5) |

2.5(1.5, 4) |

0.876 |

| Atrial fibrillation on initial ECG, n(%) |

60(9.5) |

81(4.7) |

<0.001 |

| Complete AV block, n(%) |

39(6.2) |

60(3.5) |

0.004 |

| Killip class >1, n(%) |

97(15.3) |

124(7.2) |

<0.001 |

| Systolic BP at admission, med(IQR) |

130(120, 150) |

135(120, 150) |

0.984 |

| Heart rate at admission med(IQR) |

80(70, 90) |

76(70, 88) |

0.047 |

| Multivessel disease, n(%) |

372(58.5) |

885(51.3) |

0.002 |

| 3-vessel disease, n(%) |

171(26.9) |

375(21.7) |

0.008 |

| LM stenosis, n(%) |

34(5.4) |

98(5.7) |

0.755 |

| Preprocedural flow TIMI 0, n(%) |

479(75.3) |

1152(66.7) |

<0.001 |

| Stent implanted, n(%) |

611(96.1) |

1653(95.8) |

0.747 |

| Acute stent thrombosis, n(%) |

11(1.8) |

11(0.7) |

0.15 |

| Glicoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor, n(%) |

247(38.8) |

634(36.7) |

0.358 |

| CK MB, med (IQR) |

2472(1321, 4608) |

1804(921, 3376) |

<0.001 |

| Troponin I, med (IQR) |

75(30, 116) |

50.3(20.1, 83.6) |

<0.001 |

| WBC count, med (IQR) |

12(10.1, 14.1) |

11.4(9.1, 14.1) |

0.645 |

| Hemoglobin at admission g/L, med (IQR) |

141(132, 151) |

143(133, 153) |

0.245 |

| eGFR<60ml/min/m2, n(%) |

116(18.3) |

201(11.6) |

<0.001 |

| EF, med(IQR) |

45(40, 52) |

50(42, 55) |

<0.001 |

| EF<40%, n(%) |

105(16.1) |

165(9.6) |

<0.001 |

| EF 40-49%, n(%) |

202(31.8) |

493(28.6) |

<0.001 |

| EF≥50%, n(%) |

306(48.1) |

1020(59.1) |

<0.001 |

| Therapy at discharge* |

|

|

|

| Beta blockers, n(%) |

523(82.2) |

1490(86.4) |

0.575 |

| ACE inhibitors, n(%) |

480(75.5) |

1390(80.5) |

0.554 |

| Statin, n(%) |

563(88.5) |

1279(74.1) |

0.176 |

| Diuretic, n(%) |

112(17.6) |

217(12.6) |

<0.001 |

| Calcium antagonist, n(%) |

23(3.6) |

57(3.3) |

0.101 |

| Amiodarone, n(%) |

55(8.7) |

12(0.7) |

<0.001 |

| In-hospital mortality, n(%) |

21(3.3) |

29(1.7) |

<0.001 |

Table 2.

Mortality and composite end-point MACE in the patients enrolled in the study.

Table 2.

Mortality and composite end-point MACE in the patients enrolled in the study.

| Event |

SH

N=636 |

NoSH

N=1726 |

P value |

| 30 days |

|

|

|

| All-cause mortality, n(%) |

3(0.4) |

4(0.2) |

<0.001 |

| MACE, n(%) |

15(2.5) |

25(1.5) |

<0.001 |

| Cardiovascular death, n(%) |

3(0.4) |

4(0.2) |

<0.001 |

| Non-fatal recurrent infarction, n(%) |

5(0.8) |

10(0.6) |

0.281 |

| TVR, n(%) |

13(2) |

28(1.6) |

0.578 |

| Non-fatal stroke, n(%) |

2(0.3) |

3(0.2) |

0.281 |

| 8-years |

|

|

|

| All-cause death, n(%) |

62(9.7) |

77(4.2) |

<0.001 |

| MACE, n(%) |

100(15.7) |

163(9.4) |

<0.001 |

| Cardiovascular death, n(%) |

58(9) |

66(3.8) |

<0.001 |

| Non-fatal recurrent infarction, n(%) |

37(5.8) |

68(4) |

0.051 |

| TVR, n(%) |

44(6.9) |

102(5.9) |

0.465 |

| Non-fatal stroke, n(%) |

7(1.1) |

21(1.2) |

0.835 |

Table 3.

Predictors for 30-days all-cause mortality and MACE (Cox regression model) in all analyzed patients.

Table 3.

Predictors for 30-days all-cause mortality and MACE (Cox regression model) in all analyzed patients.

| |

Univariable analysis |

Multivariable analysis |

| HR (95%CI) |

P value |

HR (95%CI) |

P value |

| All- cause mortality |

| Age, years |

1.01(1.00-1.02) |

<0.001 |

1.01(1.00-1.02) |

<0.001 |

| EF % |

0.98(0.96-0.99) |

<0.001 |

0.95(0.92-0.99) |

0.010 |

| SH |

3.14(1.28-7.65) |

0.012 |

2.19(1.16-4.18) |

0.016 |

| Killip class > at admission |

2.16(1.41-3.18) |

<0.001 |

2.13(1.38-3.29) |

<0.001 |

| 3-vessel disease |

1.92(1.06-3.83) |

0.042 |

|

|

| |

|

MACE |

|

|

| Age, years |

1.02(1.03-1.05) |

<0.001 |

1.01(1.0-1.03) |

0.001 |

| EF % |

0.96(0.93-0.98) |

<0.001 |

0.94(0.92-0.96) |

0.002 |

| Killip class >1 |

2.71(1.52-4.90) |

0.001 |

2.66(1.48-4.74) |

0.001 |

| SH |

2.42(1.16-6.09) |

0.030 |

1.99(1.03-3.85) |

0.048 |

| Previous MI |

1.96(1.16-6.09) |

0.040 |

|

|

Table 4.

Predictors for 8-years all-cause mortality and MACE (Cox regression model) in all analyzed patients.

Table 4.

Predictors for 8-years all-cause mortality and MACE (Cox regression model) in all analyzed patients.

| |

Univariable analysis |

Multivariable analysis |

| HR (95%CI) |

P value |

HR (95%CI) |

P value |

| All-cause mortality |

| Age, years |

1.04(1.02-1.06) |

<0.001 |

1.04(1.01-1.07) |

0.012 |

| EF % |

0.87(0.85- 0.91) |

<0.001 |

0.87(0.85-0.90) |

<0.001 |

| Killip class>1 at admission |

4.26(2.29-7.96) |

<0.001 |

3.89(2.04-7.42) |

<0.001 |

| eGFR<60ml/min/m2 |

1.98(1.02-3.86) |

0.045 |

1.89(1.16-3.67) |

0.054 |

| SH |

1.54(1.05- 2.80) |

0.045 |

1.49(1.10-2.03) |

0.048 |

| |

|

MACE |

|

|

| Age, years |

1.02(1.0- 1.03) |

<0.001 |

1.02(1.01-1.03) |

<0.001 |

| EF % |

0.94(0.93-0.96) |

<0.001 |

0.94(0.93-0.95) |

<0.001 |

| Killip class >1 at admission |

1.48(1.15-2.16) |

0.025 |

1.45(1.03-2.01) |

0.036 |

| SH |

1.39(1.08-1.91) |

0.042 |

1.35(1.01-1.89) |

0.048 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).