Submitted:

02 May 2024

Posted:

06 May 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

Innovation in the Public Sector

Work Teams

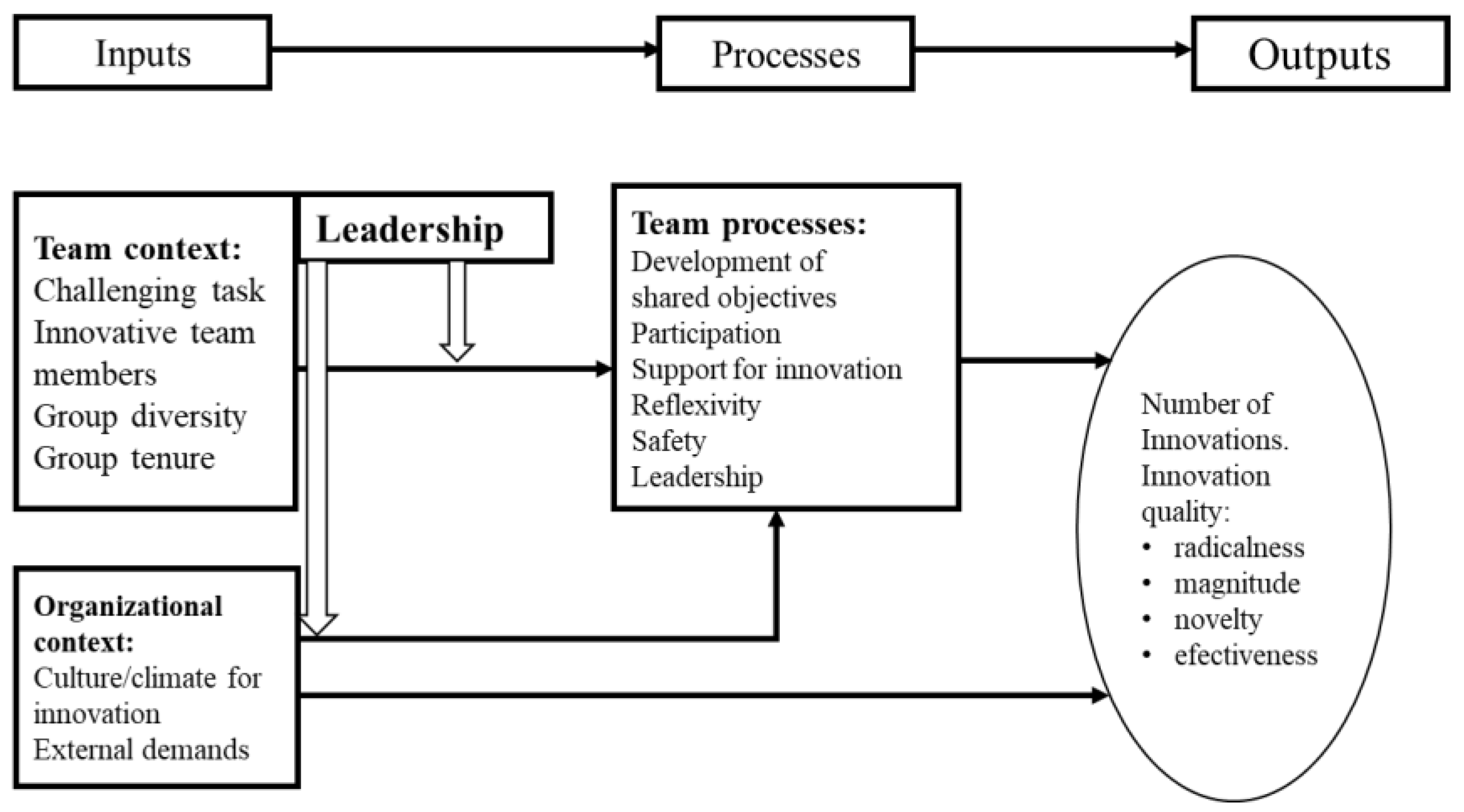

Innovation in Work Teams

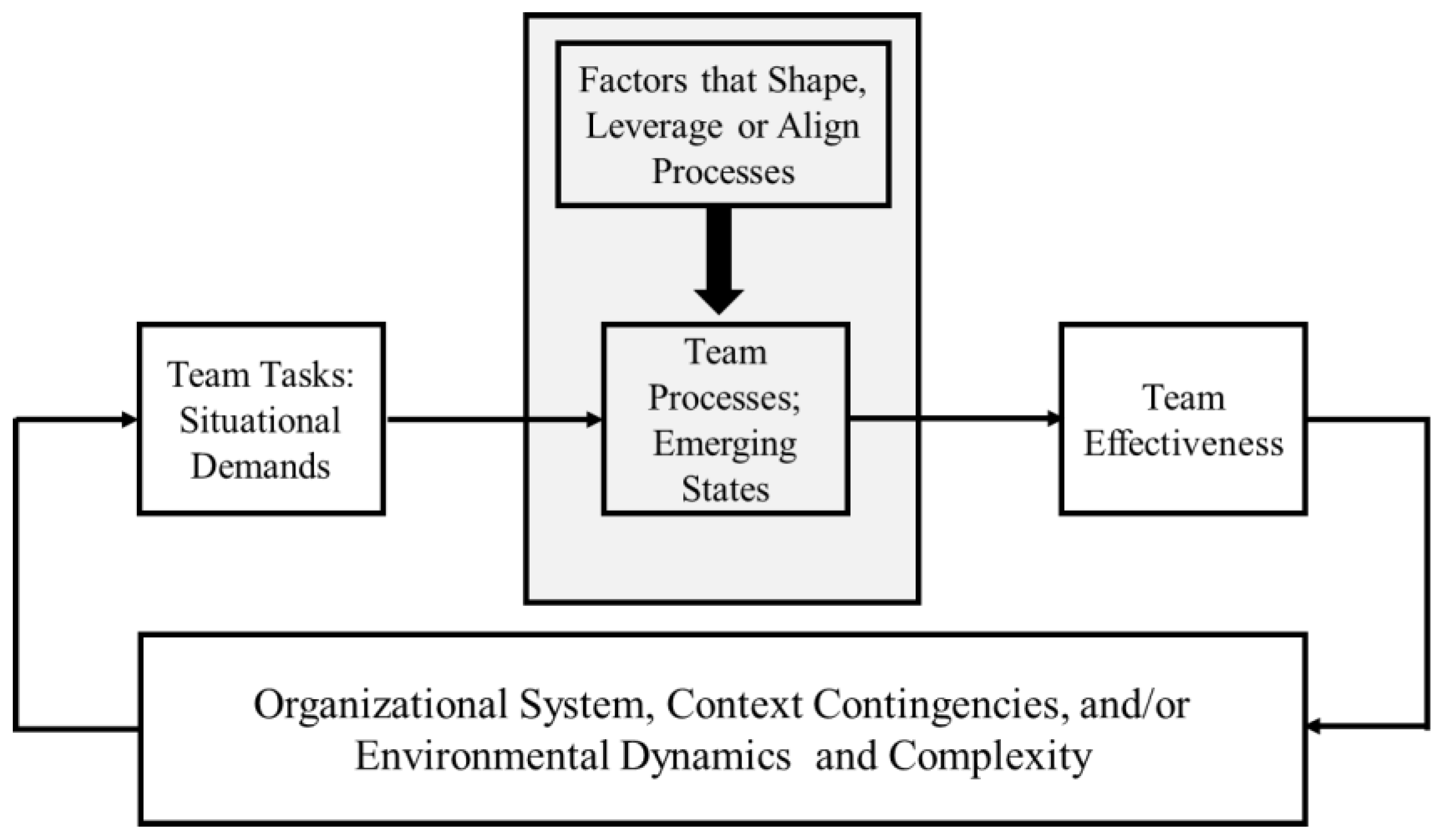

Determinants of Innovation in Work Teams

3. Method

Sample

Procedures for Collection and Analysis of Information

4. Results

5. Discussion and Conclusion

Lines for Future Research

References

- Abdullah, N.H.; Shamsuddin, A.; Wahab, E.; Hamid, N.A.A. The Relationship between Organizational Culture and Product Innovativeness. Procedia - Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 129, 140–147. [CrossRef]

- Albury, D. Fostering innovation in public services. Public money and management, v.25, n.1, p.51-56, 2005.

- Alsos G.A., Clausen T.H., Isaksen E.J, Innovation Among Public-Sector Organizations: Push and Pull Factors. In: Leitão J., Alves H. (eds) Entrepreneurial and Innovative Practices in Public Institutions. Applying Quality of Life Research (Best Practices). Springer, 2016.

- Amabile, T., Conti, R., Coon, H., Lazenby, J., & Herron, M. Assessing the work environment for creativy. Academy of Management Journal, v.39 n.5, p.1154-1184,1996.

- Anderson, N., De Dreu, C., & Nijstad, B. The routinization of innovation research: A constructively critical review of the state-of-the-science. Journal of Organizational Behavior, v.25, n.2, p.147-173, 2004.

- Anderson, N., Potočnik, K., & Zhou, J. Innovation and creativity in organizations: A state-of-the-science review, prospective commentary, and guiding framework. Journal of Management, v.40, n.5, p.1297-1333, 2014.

- APSII. Working towards a measurement framework for public sector innovation in Australia, 2013, Retrieved from https://innovation.govspace.gov.au/sites/g/files/net1566/f/files/2011/08/APSII-Draft-Discussion-Paper.pdf.

- ARC Fund. Innovation in the Public Sector State-of-the-Art Report. Sofia: Bulgaria, 2013, Retrieved from http://www.ccic-project.eu/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/CCIC-State-of-the-art-report-SotAreport.pdf.

- Bugge M., Mortensen P., Bloch C, Measuring Public Innovation in Nordic Countries, NIFU, Norway, 2013, Retrieved from http://www.nordicinnovation.org/Publications/measuring-public-innovation-in-the-nordic-countries-mepin/.

- Borins, S. Encouraging innovation in the public sector. J. Intellect. Cap. 2001, 2, 310–319. [CrossRef]

- Caldwell, D., & O'Reilly III, C. The determinants of team-based innovation in organizations: The role of social influence. Small Group Research, v.34, n.4, p.497-517, 2003.

- Creswell, J. Research design: Qualitative, quantitative and mixed method approaches (Fourth ed.). California: Sage Publications, 2014.

- De la Maza, G.Innovaciones ciudadanas y políticas públicas locales en Chile. Reforma y Democracia, v.26, p.137-164, 2003.

- DE Vries, H.; Bekkers, V.; Tummers, L. Innovation in the public sector: a systematic review and future research agenda. Public Adm. 2015, 94, 146–166. [CrossRef]

- Damanpour, F.; Schneider, M. Characteristics of Innovation and Innovation Adoption in Public Organizations: Assessing the Role of Managers. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2008, 19, 495–522. [CrossRef]

- Dombrowski, C., Kim, J. Y., Desouza, K. C., Braganza, A., Papagari, S., Baloh, P., & Jha, S. Elements of innovative cultures. Knowledge and Process Management, v.14, n.3, p.190-202, 2007.

- European Commission. Innobarometer 2010. Flash EB Series #305, 2010, Retrieved from http://ec.europa.eu/commfrontoffice/publicopinion/flash/fl_305_en.pdf.

- Fernandez, S.; Moldogaziev, T. Using Employee Empowerment to Encourage Innovative Behavior in the Public Sector. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2012, 23, 155–187. [CrossRef]

- Fierro, E., Mercado, P. and Cernas, D.A. The effect of knowledge–centered culture and social interaction on organizational innovation: the mediating effect of Knowledge management. Esic Market Economics and Business Journal, v.44, n.2, p.67-86, 2013.

- Freeman, C. La teoría económica de la innovación industrial. Madrid: Alianza Editorial, S.A, 1975.

- Glor, E. D. Key factors influencing innovation in government. The Innovation Journal, v.6, n.2, p.1-20, 2001.

- Gow, J. Public Sector Innovation Theory Revisited. The Innovation Journal, v.19, n.2, p.1-22, 2014.

- Guest, G., MacQueen, K.M. & Namey, E. Applied thematic analysis. California: SAGE Publications, Inc, 2012.

- Gurova, A., & Kurilov, M. Employee-driven innovation in the public sector. Unpublished Masters Thesis. University of Nordland, Norway, 2015.

- Hite, J.M.; Williams, E.J.; Hilton, S.C.; Baugh, S.C. The Role of Administrator Characteristics on Perceptions of Innovativeness among Public School Administrators. Educ. Urban Soc. 2006, 38, 160–187. [CrossRef]

- Hogan, S. J., & Coote, L. V. Organizational culture, innovation, and performance: A test of Schein's model. Journal of Business Research, v.67, n.8, p.1609-1621, 2014.

- Hughes, A., Moore, K., & Kataria, N. Innovation in Public Sector Organizations: A pilot survey for measuring innovation across the public sector. London: NESTA, 2011, Retrieved from https://www.bl.uk/collection-items/innovation-in-public-sector-organisations-a-pilot-survey-for-measuring-innovation-across-the-public-sector.

- Hülsheger, U.R.; Anderson, N.; Salgado, J.F. Team-level predictors of innovation at work: A comprehensive meta-analysis spanning three decades of research.. J. Appl. Psychol. 2009, 94, 1128–1145. [CrossRef]

- Janssen, O.; van de Vliert, E.; West, M. The bright and dark sides of individual and group innovation: a Special Issue introduction. J. Organ. Behav. 2004, 25, 129–145. [CrossRef]

- Jaskyte, K. Transformational leadership, organizational culture, and innovativeness in nonprofit organizations. Nonprofit Manag. Leadersh. 2004, 15, 153–168. [CrossRef]

- Kamal, M. IT innovation adoption in the government sector: identifying the critical success factors. J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 2006, 19, 192–222. [CrossRef]

- Klein, P.G.; Mahoney, J.T.; McGahan, A.M.; Pitelis, C.N. Toward a theory of public entrepreneurship. Eur. Manag. Rev. 2010, 7, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Koch, P., Hauknes, J.On Innovation in the Public Sector. Public Report No. D20. NIFU STEP, Oslo, 2005, Retrieved from http://www.step.no/publin/.

- Kovács, O. Policies Supporting Innovation in Public Service Provision. DG Enterprise and Industry, PRO INNO Europe® INNO-Grips II, 2012.

- Kozlowski, S.W.; Ilgen, D.R. Enhancing the Effectiveness of Work Groups and Teams. Psychol. Sci. Public Interes. 2006, 7, 77–124. [CrossRef]

- Liu, S. Organizational culture and new service development performance: insights from knowledge intensive business service. Int. J. Innov. Manag. 2009, 13, 371–392. [CrossRef]

- Lonti, Z., & Verma, A.The determinants of flexibility and innovation in the government workplace: Recent evidence from Canada. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, v.13, n.3, p.283-309, 2003.

- McLaughlin, P., Bessant, J., & Smart, P. Developing an organizational culture that facilitates radical innovation in a mature small to medium sized company: emergent findings, Cranfield: Cranfield School of Management, Working Paper SWP-04, 2005.

- Matthews, M., Lewis, C., & Cook, G. Public sector innovation: a review of the literature. Australian National Audit Office, Canberra, 2009, Retrieved from https://marklmatthews.files.wordpress.com/2014/02/suppl_literature_review.pdf.

- Micheli, P.; Schoeman, M.; Baxter, D.; Goffin, K. New Business Models for Public-Sector Innovation: Successful Technological Innovation for Government. Res. Manag. 2012, 55, 51–57. [CrossRef]

- Maranto, R.; Wolf, P.J. Cops, Teachers, and the Art of the Impossible: Explaining the Lack of Diffusion of Innovations That Make Impossible Jobs Possible. Public Adm. Rev. 2012, 73, 230–240. [CrossRef]

- Milliken, F. J., & Martins, L. L. Searching for common threads: Understanding the multiple effects of diversity in organizational groups. Academy of Management Review, v.21, n.2, p.402-433, 1996.

- Ministerio de Hacienda. Clasificador institucional del sector público, 2011, Retreived http://www.hacienda.go.cr/docs/51dedd6dcf55c_CLASIFICADORINSTITUCIONALDELSECTORPUBLICO2011.pdf.

- Moon, M. J. The pursuit of managerial entrepreneurship: Does organization matter? Public Administration Review, v.59, n.1, p.31-43, 1999.

- Moore, M., & Hartley, J. Innovations in governance. Public management review, v.10, n.1, p.3-20, 2008.

- Mulgan, G. & Albury, D. Innovation in the Public Sector, v.1, n.9, p.1–40, 2003.

- Namey, E., Guest, G., Thairu, L. & Johnson, L.Data reduction techniques for large qualitative data sets. In: Greg, G. & Kathleen, M. Handbook for team-based qualitative research (p.137-161). New York: AltaMira Press, 2008.

- Newman, J. Modernizing Governance: New Labour, Policy and Society. London: Sage, 2001.

- Nijenhuis, K. Impact Factors For Innovative Work Behavior in The Public Sector: The case of the Dutch Fire Department. Unpublished Masters Thesis. School of Management & Governance, University of Twente, Netherlands, 2015.

- Osborne, S.P.; Brown, L. Innovation, public policy and public services delivery in the uk. the word that would be king?. Public Adm. 2011, 89, 1335–1350. [CrossRef]

- Pärna, O., & von Tunzelmann, N. Innovation in the public sector: Key features influencing the development and implementation of technologically innovative public sector services in the UK, Denmark, Finland and Estonia. Information Polity, v.12, n.3, p.109-125, 2007.

- Potts, J.; Kastelle, T. Public sector innovation research: What’s next?. Innovation 2010, 12, 122–137. [CrossRef]

- Riivari, E.; Lämsä, A.; Kujala, J.; Heiskanen, E. The ethical culture of organisations and organisational innovativeness. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2012, 15, 310–331. [CrossRef]

- Rogers, E.M. Diffusion of Innovation. New York: The Free Press, 1983.

- Rogers-Dillon, R. H. Federal constraints and state innovation: Lessons from Florida's family transition program. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, p.327-332, 1999.

- Rousseau, V., Aubé, C., & Savoie, A.Teamwork behaviors a review and an integration of frameworks. Small Group Research, v.37 n.5, p.540-570, 2006.

- Saldaña, J. The coding manual for qualitative researchers. (Second ed.), California: Sage Publications, Inc, 2013.

- Sears, G. J., & Baba, V. V. Toward a multistage, multilevel theory of innovation. Canadian Journal of Administrative Sciences/Revue, v.28 n.4, p.357-372, 2011.

- Shoham, A.; Vigoda-Gadot, E.; Ruvio, A.; Schwabsky, N. Testing an organizational innovativeness integrative model across cultures. J. Eng. Technol. Manag. 2012, 29, 226–240. [CrossRef]

- Shore, L. M., Chung-Herrera, B. G., Dean, M. A., Ehrhart, K. H., Jung, D. I., Randel, A. E. and Singh, G. Diversity in organizations: Where are we now and where are we going? Human Resource Management Review, v.19, n. 2, p. 117-133, 2009.

- Townsend, W. Innovation and the perception of risk in the public sector. International Journal of Organizational Innovation (Online), v.5, n.3, 21, 2013.

- Vargas-Halabi, T., Mora-Esquivel, R., & Acuña, C. Cultura organizativa e innovación: un análisis temático en empresas de Costa Rica. Tec Empresarial, v.9, n.2, p.7-18, 2015.

- Van Buuren, A., & Loorbach, D. Policy innovation in isolation? Conditions for policy renewal by transition arenas and pilot projects. Public Management Review, v.11, n.3, p.375-392, 2009.

- Van Duivenboden, H., & Thaens, M. ICT-driven innovation and the culture of public administration: a contradiction in terms?. Information polity, v.13, n.4, p.213-232, 2008.

- Vigoda-Gadot, E.; Shoham, A.; Schwabsky, N.; Ruvio, A. Public sector innovation for europe: a multinational eight-country exploration of citizens’ perspectives. Public Adm. 2008, 86, 307–329. [CrossRef]

- West, M. Effective Teamwork: Practical lessons from organizational research. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 2004.

- West, M., & Hirst, G. Cooperation and teamwork for innovation. In M. West, D. Tjosvold, & K. Smith, International handbook of teamwork and cooperative working (pp. 297–319). Chichester: John Wiley & Sons Ltd, 2003.

- Windrum, P., & Koch, P. M. Innovation in public sector services: entrepreneurship, creativity and management. Edward Elgar Publishing, 2008.

- Woodman, R. W., Sawyer, J. E., & Griffin, R. W. Toward a theory of organizational creativity. Academy of management review, v.18, n.2, p.293-321, 1993.

- Young, G.J.; Charns, M.P.; Shortell, S.M. Top manager and network effects on the adoption of innovative management practices: a study of TQM in a public hospital system. Strat. Manag. J. 2001, 22, 935–951. [CrossRef]

- Yu, C., Yu, T.F., & Yu, C.C. Knowledge sharing, organizational climate, and innovative behavior: A cross-level analysis of effects. Social Behavior and Personality, v.41, n.1, p.143–156, 2013.

| Dimension | Sub-dimension | Concept |

| Context external to the organization | External demands c | Environmental demands that can promote future innovation |

| National culture c | This refers to the culture of a country, with a weak or strong inclination to avoid uncertainty | |

| Organizational context | Type of organizationc | This refers to the types of organization proposed by Mintzberg. For example, mechanical organizations are designed to protect predictable courses of action, while organic organizations have employees who are stimulated to adapt innovatively to situations of rapid change and unusual circumstances |

| Composition and structure of work teams | Diversity relevant to the workplace a,c | Heterogeneity of team members with respect to attributes related to the job or task, such as: position, profession, educational level, knowledge, skills, time worked, knowledge a |

| Diversity of history a,c | Differences not related to the task, such as age, gender or ethnicity a | |

| Task interdependence a | The extent to which team members are dependent on each other to carry out their tasks and perform effectively | |

| Goal interdependence a | The extent to which the goals of and rewards for team members are related in such a way that a team member can only achieve his or her goal if the other members achieve their goals | |

| Team size a | Number of members that make up the team | |

| Seniority a,c | Amount of time working in the organization a | |

| Team processes | Vision a,b,c | The degree to which team members have a common understanding of objectives and show a strong commitment to achieving goals a |

| Meaning of involvement a,b,c | The degree to which team members participate in decision-making processes, share information, and listen to the ideas of others | |

| Support for innovation a | This refers to the expectation, approval, and practical support for attempts to introduce new and better ways of doing things in the workplace | |

| Orientation to tasks or climate for excellence a,b | This refers to a shared concern for excellence in task performance quality with respect to the vision or shared results a | |

| Cohesion a,c | Commitment and desire of team members to maintain group membership (Lott & Lott, 1965) a | |

| Internal and external communication a | Exchange of information and ideas, both within and outside the unit | |

| Task-related conflictsa,c | This refers to disagreements among team members regarding the content of the tasks that are performed, including differences in views, ideas and opinions a | |

| Conflicts in relationships a,c | Socio-emotional conflicts arising from interpersonal disagreements a | |

| Individual attributes | Conduct of group leaders c | This refers to the possible opposition or agreement of the leader regarding innovations proposed by member(s) of the group |

| Workload c | This refers to the uncertainty that could be caused by the introduction of innovation in the unit's usual workload | |

| Innovative employee behavior c | Willingness to promote innovative ideas for change, even challenging elements of the established framework of work goals | |

| Stimulus to change c | Impulse in the worker to adapt himself or herself to changes or to modify work elements through innovation | |

| Ability to manage conflict c | The ability of employees to deal with elements of conflict with actors resistant to change, including willingness to discuss and solve disagreements, and ways of integrating different perspectives | |

| Supervisor support style c | The style of an immediate superior with a coworker, according to the type of goals that the former adopts in his of her work unit, can influence the approach, interpretation, and response to innovative ideas expressed by his or her coworkers | |

| Source: Autors’ elaboration based on a Hülsheger, Anderson and Salgado (2009), b Caldwell and O'Reilly III (2003), and c Janssen, Van de Vliert and West 2004) | ||

| Codea | Type of institution b | Functional nature of the department c | Principal activity sector of the institution |

| Int-1 | NBDI | Internal | Science |

| Int-2d | DB | Internal | Information and documentation |

| Int-3 | NBDI | Internal | Health |

| Int-4 | NFPC | Internal | Information and documentation |

| Int-5 | NBDI | Internal | Education |

| Int-6 | NBDI | Internal | Social |

| Int-7 | NBDI | Internal | Information and documentation |

| Int-8 | DB | External | Agriculture |

| Int-9 | NFPC | Internal | Transport |

| Int-10e | CG | External | Economy |

| Int-11e | CG | External | Economy |

| Int-12 | CG | External | Transport |

| Int-13f | NFPC | External | Energy |

| Int-14f | NFPC | External | Energy |

| Int-15d | DB | External | Information and documentation |

| Int-16 | CG | External | Information and documentation |

|

aAlphanumeric code assigned to the interviewee, bClassification according to the Ministry of Finance (2011) – (NBDI) Non-Business Decentralized Institution, (DB) Decentralized Body, (NFPC) Non-Financial Public Company, (CG) Central Government; cInternal = Work teams for institutional planning, financial, accounting, ICT solutions for managing internal users; External = Work teams providing certifications to the public or companies, ICT solutions for attention to external users; issuance of public regulations, interinstitutional coordination, d,e,f interviewees from different work teams in the same public institution. Source: Prepared by the authors. | |||

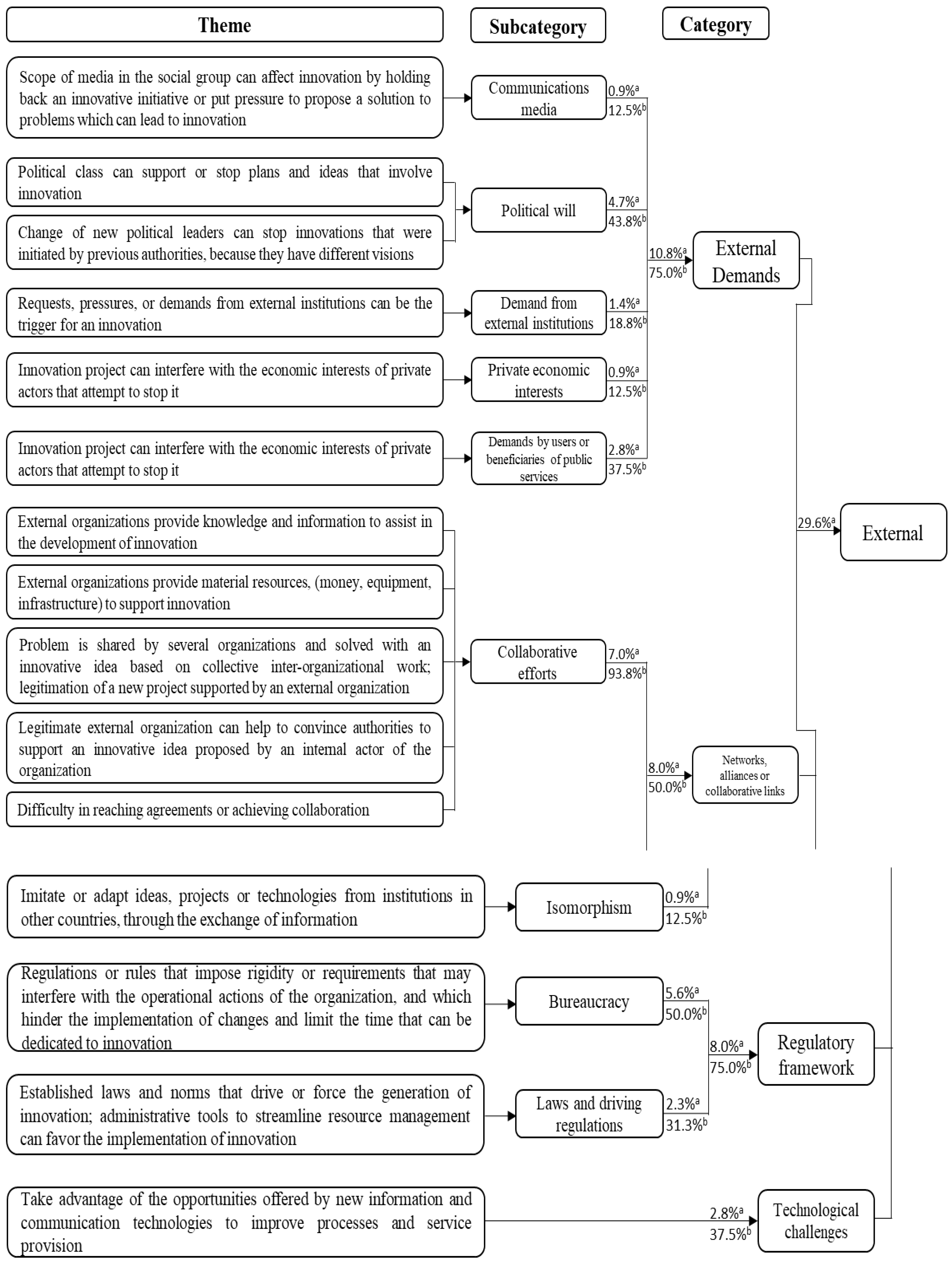

| Dimensions | Categories | Number of texts | Relative frequency |

| Environment = 63 (29.6%) |

E-External demands | 23 | 10.8% |

| E-Networks, alliances | 17 | 8.0% | |

| E-Regulatory framework | 17 | 8.0% | |

| E-Technological challenges | 6 | 2.8% | |

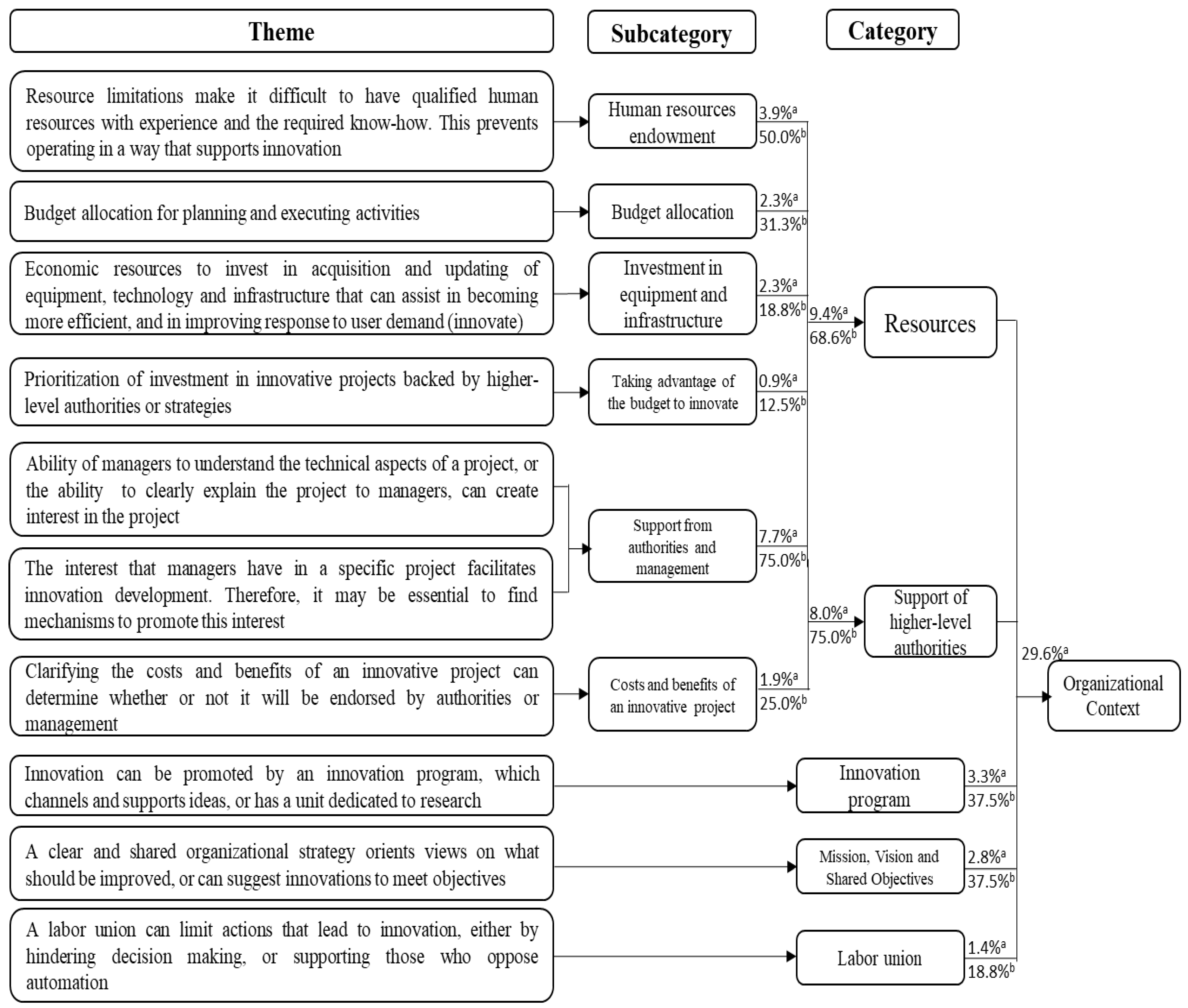

| Organizational level 55 (25.8%) |

OL-Resources for innovation | 20 | 9.4% |

| OL-Higher-level authority | 19 | 8.9% | |

| OL-Innovation program | 7 | 3.3% | |

| OL-Mission | 6 | 2.8% | |

| OL-Labor unions | 3 | 1.4% | |

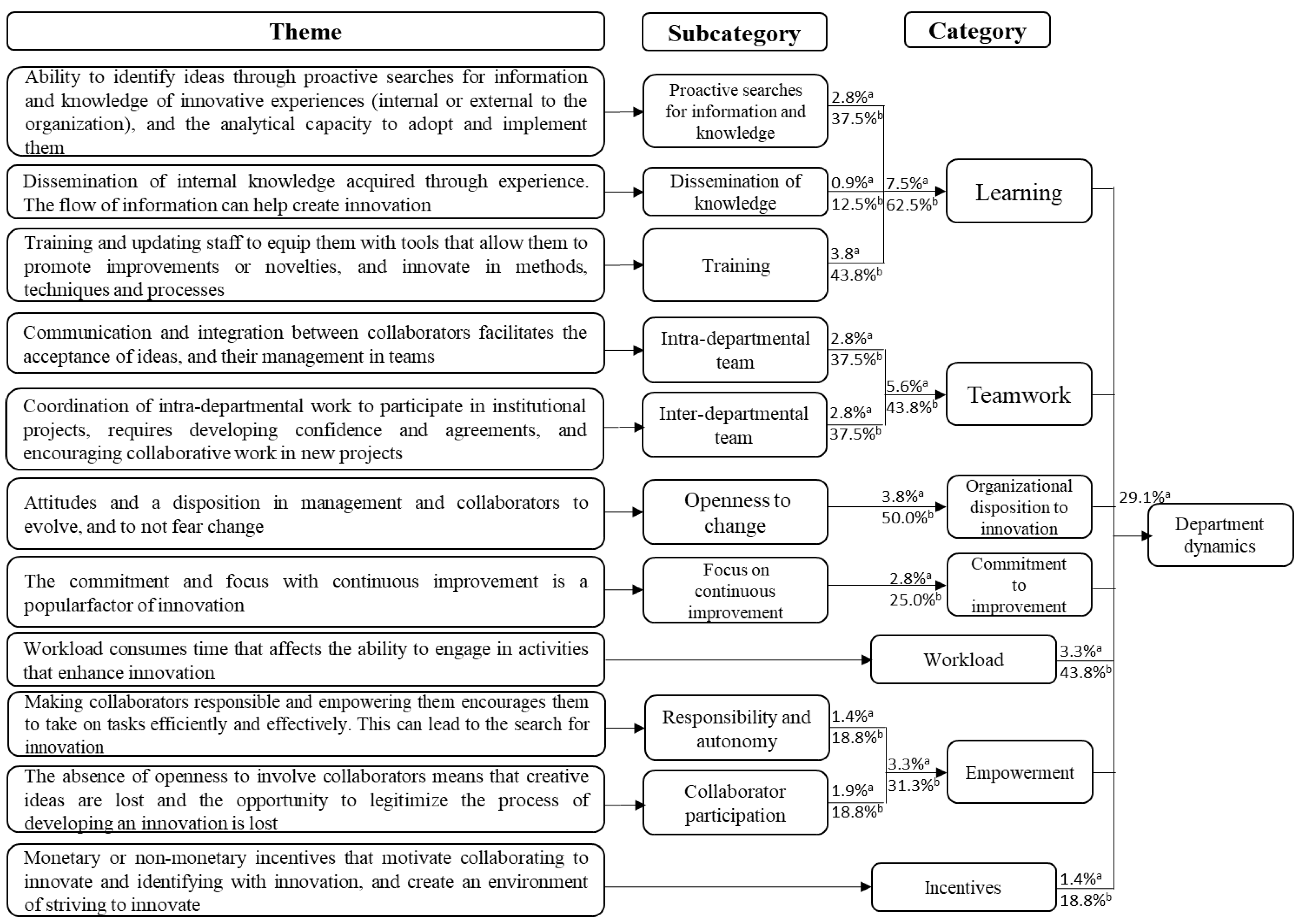

| Internal team dynamics = 62 (29.1%) |

TD-Learning | 16 | 7.5% |

| TD-Teamwork | 12 | 5.6% | |

| TD-Willingness to change | 8 | 3.8% | |

| TD-Commitment to improvement | 6 | 2.8% | |

| TD-Workload | 7 | 3.3% | |

| TD-Empowerment | 7 | 3.3% | |

| TD-Incentives | 6 | 2.8% | |

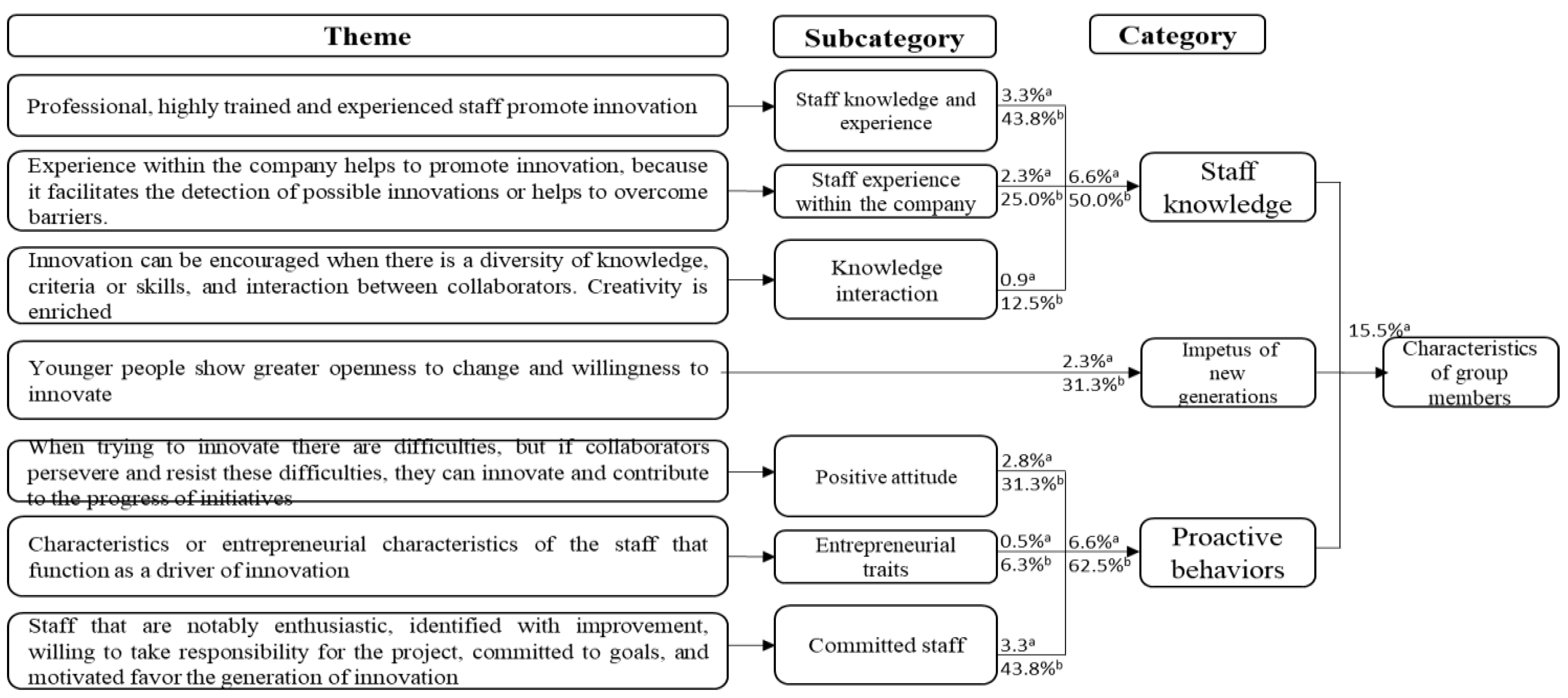

| Coworkers = 33 (15.5%) |

C-Staff knowledge | 14 | 6.6% |

| C-Proactive behaviors | 14 | 6.6% | |

| C-Impetus from new generations | 5 | 2.3% | |

| Total | 213 | 100.0% | |

| Source: Authors’ elaboration | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).