Submitted:

04 May 2024

Posted:

06 May 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Aims

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Instruments

2.3.1. Sociodemographic Questionnaire

2.3.2. Revised Children’s Manifest Anxiety Scale – Second Edition [26]

2.3.3. ChIA [27]

2.3.4. PedsQoL 3.0 Multidimensional Fatigue Scale [28]

2.4. Plan of Statistical Analyses

3. Results

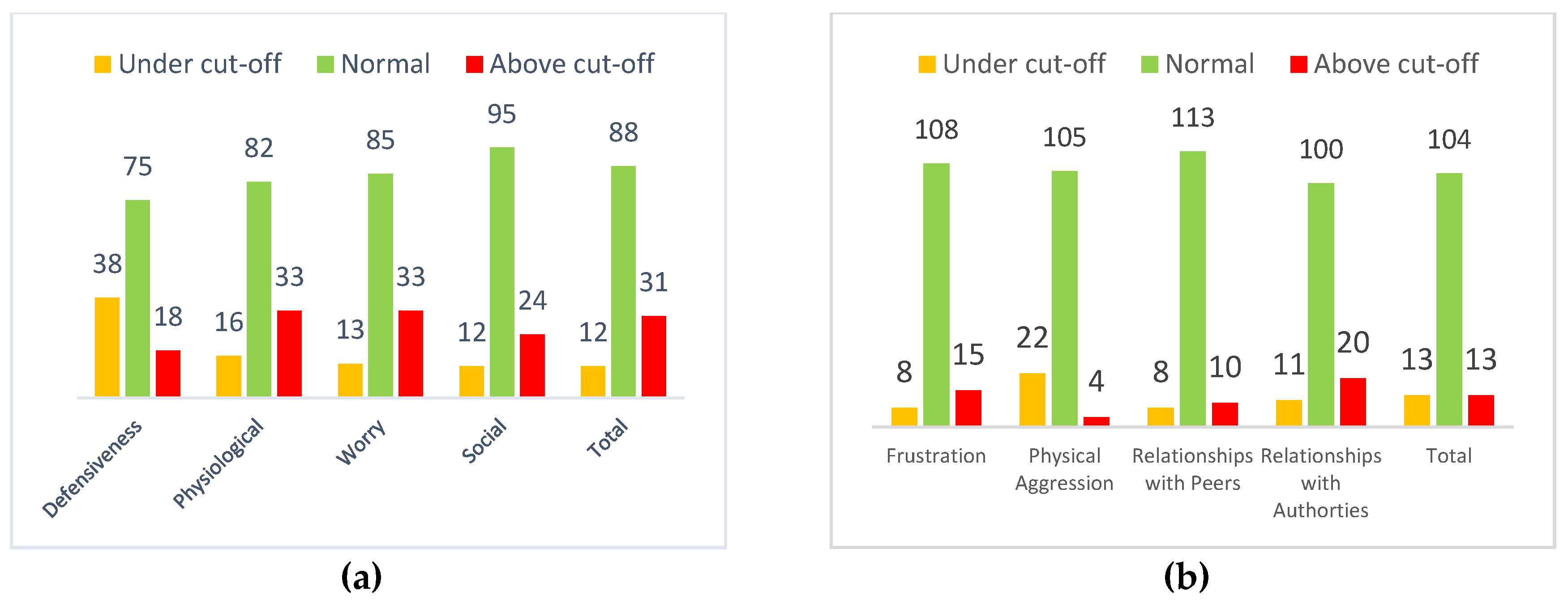

3.1. Perceptions of Anxiety, Anger, and Quality of Life of Children and Adolescents Compared to Norms

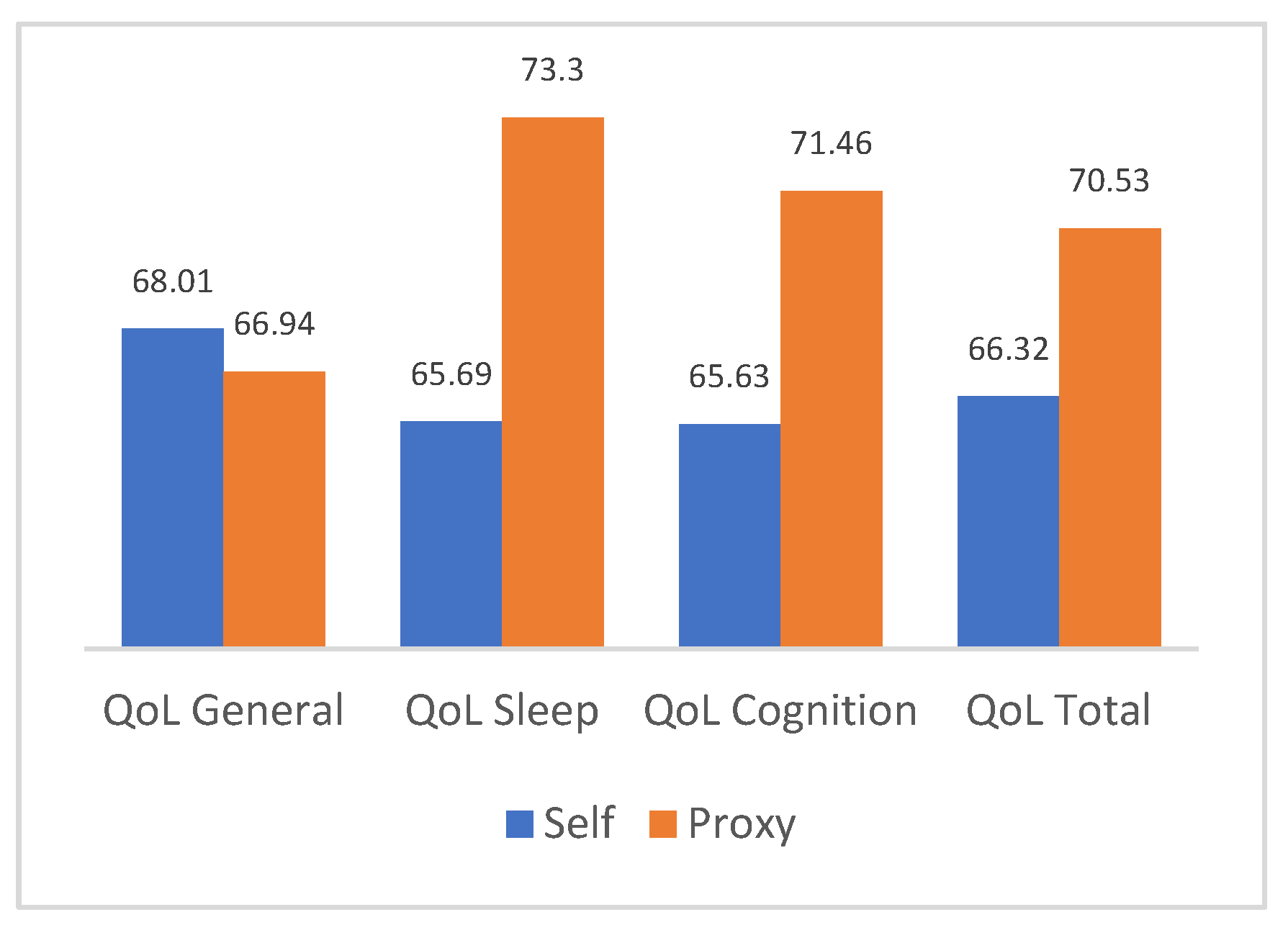

3.2. Comparison of Quality of Life Scores between Parents and Children

3.3. What Are the Factors That Influence Anxiety Symptoms in Children and Adolescents?

3.3. What Are the Factors That Influence the Perceived Quality of Life of Children and Adolescents?

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Balenzano, C.; Moro, G.; Girardi, S. Families in the pandemic between challenges and opportunities: An empirical study of parents with preschool and school-age children. Italian Sociological Review 2020, 10(3S), 777–800. [Google Scholar]

- Petts, R.J.; Carlson, D.L.; Pepin, J.R. A gendered pandemic: Childcare, homeschooling, and parents' employment during COVID-19. Gender, Work and Organization 2020, 28(S2), 515–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.S.; Skjerdingstad, N.; Ebrahimi, O.V.; Hoffart, A.; Johnson, S.U. (2022). Parenting in a pandemic: Parental stress, anxiety and depression among parents during the government-initiated physical distancing measures following the first wave of COVID-19. Stress and Health 2022, 38(4), 637–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamura, E.; Tsustsui, Y. The impact of closing schools on working from home during the COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence using panel data from Japan. Reviews of Household Economics 2021, 19, 41–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spinelli, M.; Lionetti, F.; Pastore, M.; Fasolo, M. Parents' stress and children's psychological problems in families facing the COVID-19 outbreak in Italy. Frontiers in psychology 2020, 11, 1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerniglia, L.; Cimino, S.; Ammaniti, M. L’impatto del periodo di isolamento legato al Covid-19 nello sviluppo psicologico infantile. Psicologia clinica dello sviluppo 2020, 24(2), 187–190. [Google Scholar]

- Ravens-Sieberer, U., Erhart, M., Devine, J., Gilbert, M., Reiss, F., Barkmann, C.,... & Kaman, A. Child and adolescent mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: results of the three-wave longitudinal COPSY study. Journal of Adolescent Health 2022, 71(5), 570–578.

- Arnett, J.J. The Oxford handbook of emerging adulthood, 3rd ed.; Oxford University: NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Orben, A.; Tomova, L.; Blakemore, S.J. The effects of social deprivation on adolescent development and mental health. Lancet Child Adol Health 2020, 4(8), 634–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orban, E.; Li, L.Y.; Gilbert, M.; Napp, A.K.; Kaman, A.; Topf, S.; Boecker, M.; Devine, J.; Reiß, F.; Wendel, F.; Jung-Sievers, C.; Ernst, V.S.; Franze, M.; Möhler, E.; Breitinger, E.; Bender, S.; Ravens-Sieberer, U. Mental health and quality of life in children and adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review of longitudinal studies. Frontiers in Public Health 2024, 11, 1275917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Racine, N.; McArthur, B.A.; Cooke, J.E.; Eirich, R.; Zhu, J.; Madigan, S. Global prevalence of depressive and anxiety symptoms in children and adolescents during COVID-19: a meta-analysis. JAMA pediatrics 2021, 175(11), 1142–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, L.N.; Pereira, L.N.; da Fé Brás, M.; Ilchuk, K. Quality of life under the COVID-19 quarantine. Quality of Life Research 2021, 30, 1389–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eiser, C.; Varni, J.W. Health-related quality of life and symptom reporting: similarities and differences between children and their parents. European journal of pediatrics 2013, 172, 1299–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanna, D.; Khadka, J.; Mpundu-Kaambwa, C.; Lay, K.; Russo, R.; Ratcliffe, J. Are we agreed? Self-versus proxy-reporting of paediatric health-related quality of life (HRQoL) using generic preference-based measures: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pharmacoeconomics 2022, 40(11), 1043–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matza, L.S.; Patrick, D.L.; Riley, A.W.; Alexander, J.J.; Rajmil, L.; Pleil, A.M.; Bullinger, M. Pediatric patient-reported outcome instruments for research to support medical product labeling: report of the ISPOR PRO good research practices for the assessment of children and adolescents task force. Value Health 2013, 16(4), 461–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roddenberry, A.; Renk, K. Quality of life in pediatric cancer patients: the relationships among parents’ characteristics, children’s characteristics, and informant concordance. J Child Fam Stud 2008, 17(3), 402–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otero, S.; Eiser, C.; Wright, N.; Butler, G. Implications of parent and child quality of life assessments for decisions about growth hormone treatment in eligible children. Child Care Health Dev 2013, 39(6), 782–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brazier, J.; Ratcliffe, J.; Saloman, J.; Tsuchiya, A. Measuring and valuing health benefits for economic evaluation, 2nd ed.; University Press: Oxford, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ravens-Sieberer, U.; Erhart, M.; Devine, J.; Gilbert, M.; Reiss, F.; Barkmann, C.; Siegel, N.A.; Simon, A.M.; Hurrelmann, K.; Schlack, R.; Hölling, H.; Wieler, L.H.; Kaman, A. Child and adolescent mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: results of the three-wave longitudinal COPSY study. Journal of Adolescent Health 2022, 7(5), 570–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bles, N.J.; Ottenheim, N.R.; van Hemert, A.M.; Pütz, L.E.; van der Does, A.W.; Penninx, B.W.; Giltay, E.J. Trait anger and anger attacks in relation to depressive and anxiety disorders. Journal of affective disorders 2019, 259, 259–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, D.E.; Harrison, D.W. Models of anger: contributions from psychophysiology, neuropsychology and the cognitive behavioral perspective. Brain Structure and Function 2008, 212, 371–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozzola, E.; Ferrara, P.; Spina, G.; Villani, A.; Roversi, M.; Raponi, M.; Corsello, G.; Staiano, A. The pandemic within the pandemic: the surge of neuropsychological disorders in Italian children during the COVID-19 era. Italian Journal of Pediatrics 2022, 48(1), 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludwig-Walz, H.; Dannheim, I.; Pfadenhauer, L.M.; Fegert, J.M.; Bujard, M. Anxiety among children and adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic in Europe: a systematic review protocol. Systematic Reviews 2023, 12(1), 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchetti, D.; Fontanesi, L.; Mazza, C.; Di Giandomenico, S.; Roma, P.; Verrocchio, M.C. Parenting-related exhaustion during the Italian COVID-19 lockdown. Journal of pediatric psychology 2020, 45, 1114–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mocho, H.; Martins, C.; dos Santos, R.; Nunes, C. Parental Involvement and Stress in Children’s Quality of Life: A Longitudinal Study with Portuguese Parents during the COVID-19 Pandemic Period. Children 2024, 11(4), 440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, C.R.; Richmond, B.O. Revised children’s manifest anxiety scale: Second edition (RCMAS-2); WPS Online Evaluation system: Los Angeles, CA, 2008. Italian adaption by Scozzari, S., Sella, F., Di Pietro, M.; Giunti Psychometrics: Firenze, Italy, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, W.; M Finch, A.J. Children’s Inventory of Anger (ChIA); Western Psychological Services: Los Angeles, USA, 2000; Italian adaptation by Ardizzone, I., Ferrara, M.; Giunti Psychometrics: Firenze, Italy, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Varni, J.W.; Limbers, C.A.; Bryant, W.P.; Wilson, D.P. The PedsQL multidimensional fatigue scale in pediatric obesity: feasibility, reliability and validity. Int J Pediatr Obes. 2010, 5(1), 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, J.A.; Chenneville, T.; Gardy, S.M.; Baglivio, M.T. An exploratory study of COVID-19’s impact on psychological distress and antisocial behavior among justice-involved youth. Crime & Delinquency 2022, 68(8), 1271–1291. [Google Scholar]

- Walsh, L.M.; Benjamin Wolk, C.; Becker-Haimes, E.M.; Jensen-Doss, A.; Beidas, R.S. The relationship between anger and anxiety symptoms in youth with anxiety disorders. Journal of child and adolescent counseling 2018, 4(2), 117–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olatunji, B.O.; Cisler, J.M.; Tolin, D.F. Quality of life in the anxiety disorders: a meta-analytic review. Clinical psychology review 2007, 27(5), 572–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Statistics | Frequencies | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Min | Max | M | SD | ||||

| Children’s age | 6 | 16 | 12.44 | 2.74 | |||

| Children’s gender | Male Female |

60 71 |

45.8% 54.2% |

||||

| Children’s School level | Primary school Secondary school, 1st Secondary school 2nd |

35 50 46 |

26.7% 38.2% 35.1% |

||||

| Parental Age | 30 | 66 | 46.46 | 6.02 | |||

| Parent’s gender | Male Female |

26 105 |

19.8% 80.2% |

||||

| Parental Schooling Years | 5 | 20 | 13.82 | 3.42 | |||

| Parental Civil status |

Single parent Twice parents |

10 121 |

7.6% 92.4% |

||||

| Parental Perceived economic condition |

Low Medium High |

23 72 36 |

16.6% 55.0% 27.5% |

||||

| QoL General | QoL Sleep | QoV cognition | Total QoL total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Freq. | Perc. | Freq. | Perc. | Freq. | Perc. | Freq. | Perc. | |

| Very low QOL | 1 | 0.8% | 6 | 4.6% | 6 | 4.6% | 0 | 0% |

| Low Quality of Life | 21 | 16% | 19 | 14.5% | 21 | 16% | 14 | 10.7% |

| Moderate QoL | 72 | 55% | 75 | 57.3% | 65 | 49.6% | 88 | 67.2% |

| Good QoL | 37 | 28.2% | 31 | 23.7% | 39 | 29.8% | 29 | 22.1% |

| Total | 131 | 100% | 131 | 100% | 131 | 100% | 131 | 100% |

| QoL General | QoL Sleep | QoL cognition QoL total | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Freq. | Perc. | Freq. | Perc. | Freq. Perc. Freq- | Perc. | |||

| Very low QOL | 8 | 6.1% | 0 | 0% | 4 | 3.1% | 1 | 0.8% |

| Low QoL |

36 | 27.5% | 16 | 12.2% | 30 | 22.9% | 25 | 19.1% |

| Moderate QoL | 66 | 50.4% | 67 | 51.1% | 50 | 38.2% | 76 | 58% |

| Good QoL | 21 | 16% | 48 | 36.6% | 47 | 35.9% | 29 | 22.1% |

| Total | 131 | 100% | 131 | 100% | 131 | 100% | 131 100% | |

| Model | Anovaa | Coefficientsa | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R-square | Df | F | p. | Beta | T | P | |||

| Model | .15 | 3 | 7.6 | .0001b | |||||

| Sex | .22 | 2.68 | .008* | ||||||

| Parents of PEDS TOT self-report | -.197 | -2.40 | .018* | ||||||

| Total Anger | .24 | 2.93 | .004* | ||||||

| Model | Anovaa | Coefficientsa | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R-square | Df | F | p. | Beta | T | P | |

| Model | .33 | 2 | 31.67 | .0001b | |||

| Physiological anxiety | -.34 | -4.12 | .0001* | ||||

| Social Anxiety | -.32 | -3.90 | .0001* | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).