1. Introduction

One of the main reasons that trigger countries to open up their markets is to improve the welfare of their people. Trade, in literature, is assumed to affect households’ welfare via changes in the relative prices they face as both consumers and producers (Ghahremanzadeh, Malakshah, & Pishbahar, 2017). Under perfectly competitive markets, trade indicators like import tariffs have close to a complete pass-through effect on domestic economic indicators like consumer prices. Price effects of trade policies in turn affect production, resource allocation, income, and consumption (Cabalu & Rodriguez, 2007). Some production sectors would expand while others will contract. Households that are in the expanding sectors may benefit more than those in the contracting sectors. They benefit if their consumption basket is dominated by goods whose prices are decreasing due to a decrease in import prices (Cabalu & Rodriguez, 2007). However, opening up may not work for all countries or all groups within a country (Siddiqui, 2015). Some countries and certain groups within a specific country could gain or lose more than others. Market imperfections may hinder the transmission of trade policies to economic indicators like prices and income.

The imperfections, mainly caused by high transactional costs, are more prevalent in developing countries (Nicita, 2009). This raises the concern of whether domestic markets of Sub-Saharan African countries are responsive to trade policies like import tariffs. Further, in markets where there is responsiveness, a key issue is the distributional effect. Specifically, which households are gaining or losing, which sectors are expanding or contracting, or which regions of a country are being adversely affected. Answers to these questions would be relevant because some trade policies could reduce poverty but, at the same time, accelerate levels of inequality, and both could be a result of the same distributional impact (Marchand, 2012). There is also a concern that opening up domestic markets for developing countries could as well increase their vulnerability to trade (Siddiqui, 2015). This paper seeks to address these concerns and provide insight into the distributional effects of trade policies in Sub-Saharan countries, with a focus on Kenya. The country forms a suitable case study as it has been observed to be among the most diversified countries in the East African Community (EAC) economies (Gasiorek, Byiers, Rollo, & CUTS International, 2016). Further, the share of Kenya’s imports from EAC is around 2% implying that more than 97% of its imports come from outside the EAC.

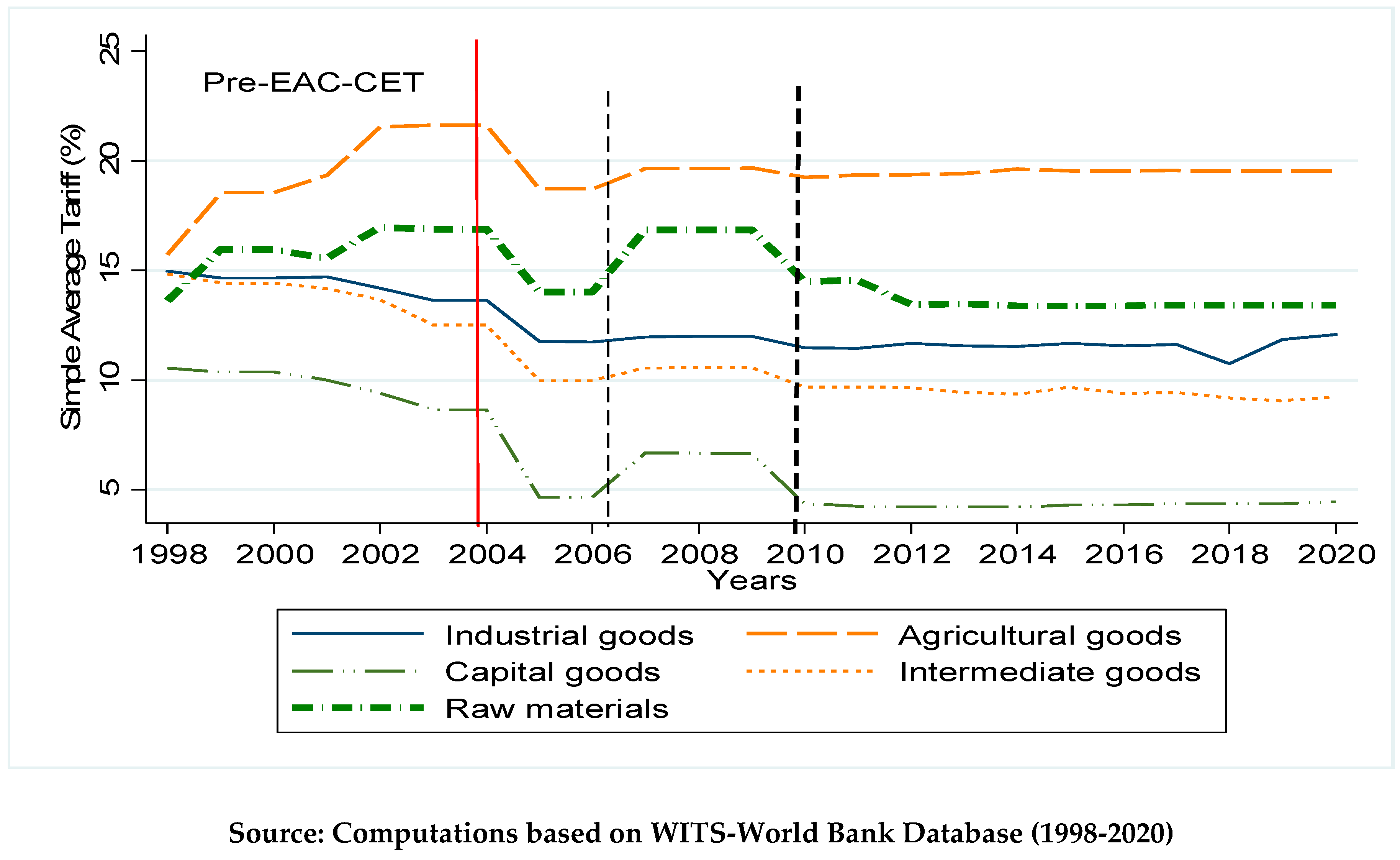

The resumption of the EAC in 2005 saw an introduction of the Customs Union (CU) in which a 3-band CET was formed. The CET saw a significant decrease in import tariffs for Kenya as highlighted in

Figure 1. In 2000, the average import tariff (simple mean) was 20.9%, but in 2005, after the formation of the EAC-CET, the rate decreased to 12.42%. The figure shows that, on average, import tariffs fell by approximately 25% after the formation of the EAC-CET. The products that are highly protected by the EAC-CET are agricultural goods followed by raw materials. The least protected products are capital goods as seen in

Figure 1. The significant decline in tariffs after the year 2005 is defined as the period of trade liberalization in Kenya.

Welfare and trade liberalization concerns are not new to Kenyan literature. However, they have mostly been addressed at the macro level (Khorana, Kimbugwe, & Perdikis, 2009; McIntyre, 2005; Shinyekwa & Othieno, 2013). This has mostly been attributed to the lack of disaggregated information to trace consumer prices, labor incomes, and consumption patterns. The studies do not indicate which products or households are affected by trade liberalization. One may also ask if there is a difference between the impact on the poor versus the non-poor or rural versus urban households. Further, the country emphasizes the importance of protecting domestic farmers and industries from fierce competition. As such, the country agreed to join neighboring countries in the form of regional integration. However, little is done to evaluate how such strategic decisions affect households in the country. It could be a case where only a few traders reap the benefits of trade policies while other households are adversely affected. For example, Bergquist and Dinerstein (2020) show that in Kenya, consumers only reap 18% of trade gains while 72% is absorbed by middlemen.

We attempt to fill this research gap by analyzing the micro-level effect of trade liberalization using two Kenyan household budget surveys (Kenya Integrated Household Budget Survey (KIHBS)-2005/2006 and KIHBS-2015/2016). The two surveys are not only comprehensive, but they also present two scenarios of trade liberalization in Kenya. The first represents a period when Kenya, Uganda, and Tanzania revived the EAC and formed the CU which brought about the formation of a CET. The second is ten years since the creation of the CET. Thus, the prices of 2005 are treated as 'pre-trade liberalization prices’ while the prices of 2015 are 'post-trade liberalization prices'. Thus, this can be more of a short-run analysis, highlighting the concern whether in the short run trade liberalization may harm those who were initially worse off or less prepared for the transition (Borraz, Rossi, & Ferres, 2012). The significant element of these surveys is that they provide detailed expenditures and amounts of commodities that households consume. From this information, it is possible to measure the extent to which the consumption levels of households are affected by price changes. This is conventionally done by taking a ratio of expenditures and the amounts of goods consumed to obtain unit values (Deaton, 1989). The unit values are then matched with import tariffs for the same products.

Preliminary results indicate that while the income effect positively contributed to household welfare, the expenditure effect exerted a negative impact. Overall, the positive income effect resulting from price changes outweighed the negative expenditure effect, leading to improved welfare for households in the middle-income and upper-income deciles. However, the poorest households in the lowest income decile experienced a negative welfare effect, as the positive income effect was insufficient to offset the negative expenditure effect for rural households. Welfare gains were more pronounced in rural areas compared to urban areas, indicating a pro-poor impact of the EAC-CET. Further, counties on the EAC borders benefited more from cheaper imports and lower transport costs, leading to increased welfare for households in these regions. In terms of comparison with other studies done in sub-Saharan Africa, this study is unique in several ways. First, the research focus. Several studies that analyze trade liberalization are not usually clear on their definition of trade liberalization; their studies mainly examine it as a broad change in a trade regime, with no clear definition of the policy being examined. The focus of this study focuses on import tariffs, which are traceable and measurable trade policies. The second is the methodological approach. Most studies for sub-Saharan countries on trade policies are ex-ante simulation studies that rely on ad-hoc assumptions about import tariffs. One of the common assumptions is a complete import tariff pass-through effect on domestic prices. Facilitated by data availability, this study is unique in its approach, conducting an ex-post analysis of a trade policy with little ad-hoc assumption. Finally, the study is unique in its findings and implications. The incomplete pass-through of import tariffs on agricultural products helps illuminate significant policy implications for policymakers in sub-Saharan African countries interested in trade policy issues.

This paper first presents an overview of Kenya within the EAC-CET in section 2. It then briefly highlights the literature on trade liberalization and household welfare in section 3. Next section 4, describes the methodology and the data used in the analysis. Section 5 discusses the findings and finally, section 6 concludes and provides policy implications.

2. Kenya and EAC-CET

Kenya, Uganda, and Tanzania agreed to form a Customs Union (CU) while reviving the EAC in 2005. The CU came in handy with the establishment of a CET. The CET categorized imports into four main categories: raw materials, intermediate products, final products, and sensitive products. The first category attracted a tariff band of 0%, the second one attracted 10%, the third attracted 25% and the fourth attracted a tariff band of between 30%-100%. The classification of the goods created 5,395 tariff lines at the Harmonized System (HS) 8-digit level. Out of these, 2,003 (37%) accounted for the 0% band, 1,152 (21.4%) were for the 10% band, 2,176 (40.3%) were for the 25% band and 64(1.2%) were tariff bands that were greater than 25% (Shinyekwa & Katunze, 2016). The rationale behind the EAC-CET structure was to enable local manufacturers to build the capacity to produce locally within the regional bloc. Further, the structure was to help reduce imports from non-EAC imports and support local producers within the region. Currently, there are 5395 tariff lines at Harmonized System (HS) digit level 8. After the formation of the CET, the number of Kenya’s tariffs that were lowered was 3,216, those that increased were 1,144 and those that remained unchanged were 753 (Karingi, Pesce, & Sommer, 2016).

During the formation of the CU, the most liberalized Partner State was Uganda, with rates ranging between 7% and 15%, followed by Rwanda, with rates of 5% to 25%. Tanzania, on average, had rates of 25%, Burundi had rates in the 40% range, and Kenya—which was the least liberalized—had rates between 35% and 100%. The EAC-CET was to be implemented in two phases. This was because of the variations in the levels of development of the three countries. The first phase involved all countries adopting a three-tariff band structure while Tanzania and Uganda were expected to maintain an internal tariff on designated imports from Kenya. Under the second phase— which was after a transitional period of 5 years— internal tariffs were to be abolished, allowing imports from Kenya to access Tanzania and Uganda at zero tariffs (Onyango & Mugoya, 2009).

Kenya, by grouping products into four bands under the EAC-CET, saw a large number of its product tariffs reduced compared to the pre-CU tariffs. Several items, however— in the category of sensitive items- experienced an increase in their import tariffs compared to the tariffs before the CU. The EAC-CET also saw the removal of import tariffs among the Partner States. Goods were allowed to be imported into the Kenyan market from Uganda and Tanzania without any import tariffs, as long as they were proven to originate from these markets. Burundi and Rwanda joined the EAC in 2007. Like Uganda and Tanzania, their products were also allowed to enter the Kenyan market under zero tariffs. All these adjustments to tariffs were aimed at spurring growth in the EAC Partner States. This notwithstanding, there are scanty empirical studies that show how so far, adjustments have harmed or benefited the households of the Partner States, particularly Kenyan households.

3. Literature Review

Household welfare, encompassing living standards, is commonly assessed using indicators such as consumption and income levels (Moratti & Natali, 2012). Consumption levels are regarded as superior measures due to their reflection on long-term income (Deaton & Zaidi, 2002). Trade theory associates import tariffs with welfare through the expenditure and income channels, resulting in a "first effect" and a "second effect" on welfare (Gasiorek et al., 2016; Marchand, 2017). The first effect is driven by price changes, wherein reduced import tariffs can enhance consumer welfare and benefit producers engaged in exporting. However, long-term competition may lower domestic prices and reduce producer incomes. The second effect pertains to structural changes that impact different sectors, labor incomes, and employment, potentially increasing poverty among unskilled laborers. This is particularly in developing countries relying on agriculture and rural industries.

Deaton's (1989) pioneering empirical study analyzed trade policy effects on household welfare using survey data. The study identified three channels through which price fluctuations as a result of trade policies influence welfare: consumption, production, and labor income. The study found that households engaged in production experienced welfare gains across all income levels, with the middle-income group benefiting the most. Few high-income households were producers, resulting in lower welfare gains. At the lower income distribution, many households were producers and consumers. This study revealed significant distributional effects of trade policies. Subsequent research confirmed country-specific distributional impacts. For example, middle-income earners gained more in Indonesia (Deaton, 1989), wealthier households benefited more in Mexico (Nicita, 2009), and poor households gained more from trade reforms in Argentina (Porto, 2006) and India (Marchand, 2019). Similar findings were observed in the United States (Fajgelbaum & Khandelwal, 2016), China (Zhu, Yu, Wang, & Elleby, 2016), and several sub-Saharan African countries (Nicita, Olarreaga, & Porto, 2014).

In terms of the approach of analyses, empirical studies look at trade liberalization and welfare through the expenditure channel or the income channel. Some studies, such as Porto (2006), Nicita (2009), Marchand (2012), Marchand (2019), Borusyak & Jaravel (2021), Vo & Nguyen (2021), and Zhu et al. (2016), employ both expenditure and income channels to analyze trade policy effects. However, other studies focus on one channel. For instance, Fajgelbaum & Khandelwal (2016) concentrate on the expenditure channel, highlighting the disproportionate impact of trade policies on poorer households due to higher proportions of food spending. In six Sub-Saharan African countries, Nicita et al. (2014) find that, apart from Ethiopia, trade policies favor poor households in terms of income. This is attributed to their reliance on agricultural sales. Low-income households, who derive a significant portion of their income from selling goods, may mitigate the effect of increased prices through the income effect (Lederman & Porto, 2016).

The existing empirical literature (Balistreri, Jensen, & Tarr, 2015; Balistreri, Maliszewska, Osorio-Rodarte, Tarr, & Yonezawa, 2016; Balistreri, Rutherford, & Tarr, 2009; Gasiorek et al., 2016; Omolo, 2012) for Kenya lacks clarity regarding the beneficiaries and losers of trade policies in terms of both expenditure and income channels. They do not provide a comprehensive understanding of which household groups experience greater gains. The studies often aggregate the welfare effects, limiting the ability to identify specific beneficiary groups or the channels of gains or losses. This research aims to bridge this gap in the literature. A critical aspect of this study involves analyzing the welfare implications to discern the distributional effects of trade policies in Kenya. To achieve this, the study adopts an approach that combines both the expenditure and income channels, drawing upon the methodology employed by Deaton (1989), Porto (2006), Nicita (2009), Marchand (2012), Marchand (2019), Borusyak & Jaravel (2021), Vo & Nguyen (2021), and Zhu et al. (2016).

4. Methodology and Data

4.1. Welfare Measure

Households in developing countries play the dual role of consumption and production (Nicita, 2009). In this context, welfare analysis accounts for these two roles (Deaton, 2018). In this study, the interest is to study how changes in prices, caused by a change in tariffs, affect household welfare. The effects can be derived from an indirect utility function, in which a household’s utility function is a function of income and prices (Deaton, 2018). Following the specification of Marchand (2019) a household is faced with an indirect utility function of the form:

Where

is income and

is a vector of the price of

goods. Differentiating (1) and applying Roy’s identity

1 yields:

Where

is the amount of good

consumed by household

. Since households are assumed to play a dual role, their income is obtained from two components; labor income

and profits

from selling good

thus:

Differentiating (3) and applying Hotelling’s lemma

2 results to:

Where

is the quantity of good

sold in the market by household

. Substituting equation (4), in (2) yields:

Equation (5) can be simplified by assuming the marginal utility of income

is one (Nicita, 2009), and converting the right-hand side terms into percentages. Thus,

The term

is the approximation of the monetary value of the change in indirect utility for household

(Nicita, 2009). Assuming that income equals expenditure, equation (6) can be divided by the income of household

to obtain a money metric utility function of the form:

Where

is the negative compensation variation of price changes (Marchand 2019). If it is negative, it implies a welfare loss. In such a case, it shows the amount by which households need to be compensated to have the same utility as they had before the price change. Equation (7) can be simplified to:

Where

is the share of income obtained from the labor market,

is the share of income of the household obtained from selling goods

and

is the share of expenditure on goods

. The first two terms on the right-hand side of equation (8) define the welfare impact through income and enter positively into the welfare function. Specifically, they are the income effect of price changes (Marchand, 2019). The last term is the welfare effect of price changes through the expenditure channel. The term is negative showing that, as prices increase, the net expenditure of a household for a given consumption basket increases hence reducing welfare. Thus, the second and last term shows that a change in the price of good

favors or harms the household depending on the exposure of the household’s budget to that particular good (Nicita, 2009). Under trade policy analysis, the impact of a tariff on welfare is determined by the tariff’s prior impact on the prices of commodities and labor incomes of the households.

4.2. Empirical Analysis

Empirically, the estimation of welfare effects of the EAC-CET on equation (8) involves several variables that are first pre-estimated. Several steps are followed. The first involves the computation of a tariff-pass-through equation that captures the effect of tariffs on domestic prices. This study follows Nicita's (2009) approach, where the pass-through equation is specified as:

Where

is domestic price of good

at time

,

is the foreign in price,

is the ad valorem tariff rate,

is the domestic price of an import-competing good,

is an industry-specific trend,

is county fixed effects,

are time-fixed effects and

is an independent and identically distributed (

IID) error term. The second step involves using the price estimate from equation (9) to compute changes in prices as:

Where,

is an estimate of 2005 domestic prices and

is the 2015 price estimate obtained from the tariff pass-through equation (9)

3. The third step involves using the change in prices from equation (10) to compute changes in income as:

Where

is the price-labor income elasticity obtained from a labor income equation (Nicita, 2009) specified as:

Where

is average labor income for household

at time

and

is the price of a good

at time

. Because we assume import tariffs directly affect domestic prices, the coefficient

is the measure of how labor incomes respond when prices change. The symbol

represents individual characteristics that affect labor incomes. Among them are age, gender, marital status, and religion. The final step involves computing the shares. The share of income obtained from the labor market

is computed solving

Share of income from selling goods

is found by computing

and the share of expenditure on goods

is solved by

. The shares together with

and

from equations (10) and (11) are plugged in (8) to compute the welfare effect of import tariffs. The welfare measure of equation (8) is analyzed in terms of income deciles of households in the country. The lower-income deciles are categorized as poor households while the upper-income deciles are rich households. Further, households are classified in terms of rural versus urban and county classifications in terms of the border to EAC countries and the major cities of the country. In estimating equation (8), only percentage gains or losses in welfare are observed. Positive values show welfare gains while negative values show losses. The losses show the amount by which households need to be compensated to have the same utility as they had before the price change (Marchand, 2019). To explore whether welfare varies with some particular classes or groups of households, the following model is estimated:

Where

is an estimate from the welfare equation (8),

is a vector of household characteristics among them; the age of the household head, the gender of the household head, and the size of the household. The term

is a control variable for labor characteristics of the household head which include, skill levels, job formality, and sector. Finally,

are county fixed effects and

is an assumed

IID error term. Equation (13) is estimated for both rural and urban households

4.3. Data

The empirical work for this paper relies on the Kenya Integrated Household Budget Survey dataset for 2005/2006 and for 2015/2016. Data from the survey were matched with tariff data from the World Integrated Trade Solutions (WITS). Data for products in the surveys are reported as final goods, such as milk, maize, and wheat. In WITS, they are disaggregated into a harmonized system (HS). For example, milk is in the form of milk and cream, not concentrated or containing added sugar or other sweetening matter (HS 0401), and milk and cream, concentrated or containing added sugar or other sweetening matter (HS 0402). Thus, products in the WITS are hand-matched and aggregated to form the final products reported in household surveys. For example, milk has an average of HS 0401 and HS 0402. The import tariffs were computed as follows: Whereis the ad valorem tariff of good in WITS, and is the import volume of that good. This ensures the weighting of tariffs on the respective imports. Some products in the KIHBS are averaged to form a single representative product; for example, maize flour in the surveys was computed by obtaining the average of loose maize flour (code 00108), sifted maize flour (code 00110), and fortified maize flour (00111). Averaging these product groups and matching them with tariff data from the WITS resulted in the formation of 110 products. Of these, 50 were agricultural and 60 were manufactured. Agricultural products were further subdivided into cereals, meat, dairy products, vegetables, fruits, beverages, and tobacco. The manufactured products were also subdivided into garments, footwear, food accompaniments, household equipment, chemicals, stationery, and furniture.

It was not possible to follow the same households from 2005 to 2015 hence these panel data may not be feasible. This study follows Deaton's (1988) approach, in which groups of individuals called cohorts that share the same time-invariant characteristics or are in the same setup are followed over time. Households in this study were categorized into rural and urban households. The surveys reported expenditures and physical quantities that were purchased by households. Dividing the two, we obtain unit values that proxy the domestic price (Marchand, 2012; Nicita, 2009). The unit values obtained depend on actual market prices, and as such, are indicators of spatial variation in prices across the country (Deaton, 1988). To control for inflationary factors, the unit values were adjusted to real values using consumer price indices for 2005 and 2015. To reduce measurement errors, median prices were used for the analysis rather than average prices. Median prices are less affected by outliers than mean prices (Deaton, 2019). The median price selection process was performed in two steps. The first step involved selecting the median price among the 10 households in a cluster. Thereafter, the second step involved picking the median prices from the clusters in each of the 47 counties. The segregation of households in rural or urban areas was done after the prices were selected. This was mainly done to minimize sample selection bias. Foreign prices are computed by dividing the import amount by the import value of the products. Import values and amounts were obtained from the International Trade Statistics (ITC) trade map and COMTRADE. The annual average exchange rates for 2005 and 2015 were obtained from Central Bank of Kenya (CBK) statistics. The analysis was conducted for all 47 counties in the country. Population, a proxy for domestic demand, is in the form of rural and urban setups; thus, there were 92 data values for the population since Mombasa and Nairobi are fully urban. Population data were obtained from the Kenya Statistical Abstracts 2005 and 2015.

On average domestic prices of the products were higher in 2015 compared to 2005 as seen in

Table 1. The exception was cereals and food accompaniments. Foreign prices are also higher in 2015 compared to 2005 except for garments, furniture, vegetables, and fruits. For the two periods, domestic prices of beverages, cereals, food accompaniments, and furniture are generally higher than foreign prices in the two periods of the study. Foreign prices for vegetables and fruits, meat and dairy, garments, stationaries, household equipment, and chemical are generally higher than domestic prices. The differences in prices confirm the presence of prices arbitrage where,

. Thus, a confirmation of the existence of trade and non-trade barriers that causes the differences in domestic and foreign prices. One of the potential trade barriers is trade costs like import tariffs.

There is no significant variation in domestic prices in terms of counties for the two years. In both 2005 and 2015, the highest average prices were observed in Nairobi, the capital city of Kenya. This generally shows that products are generally more expensive in the capital city compared to other counties in the country.

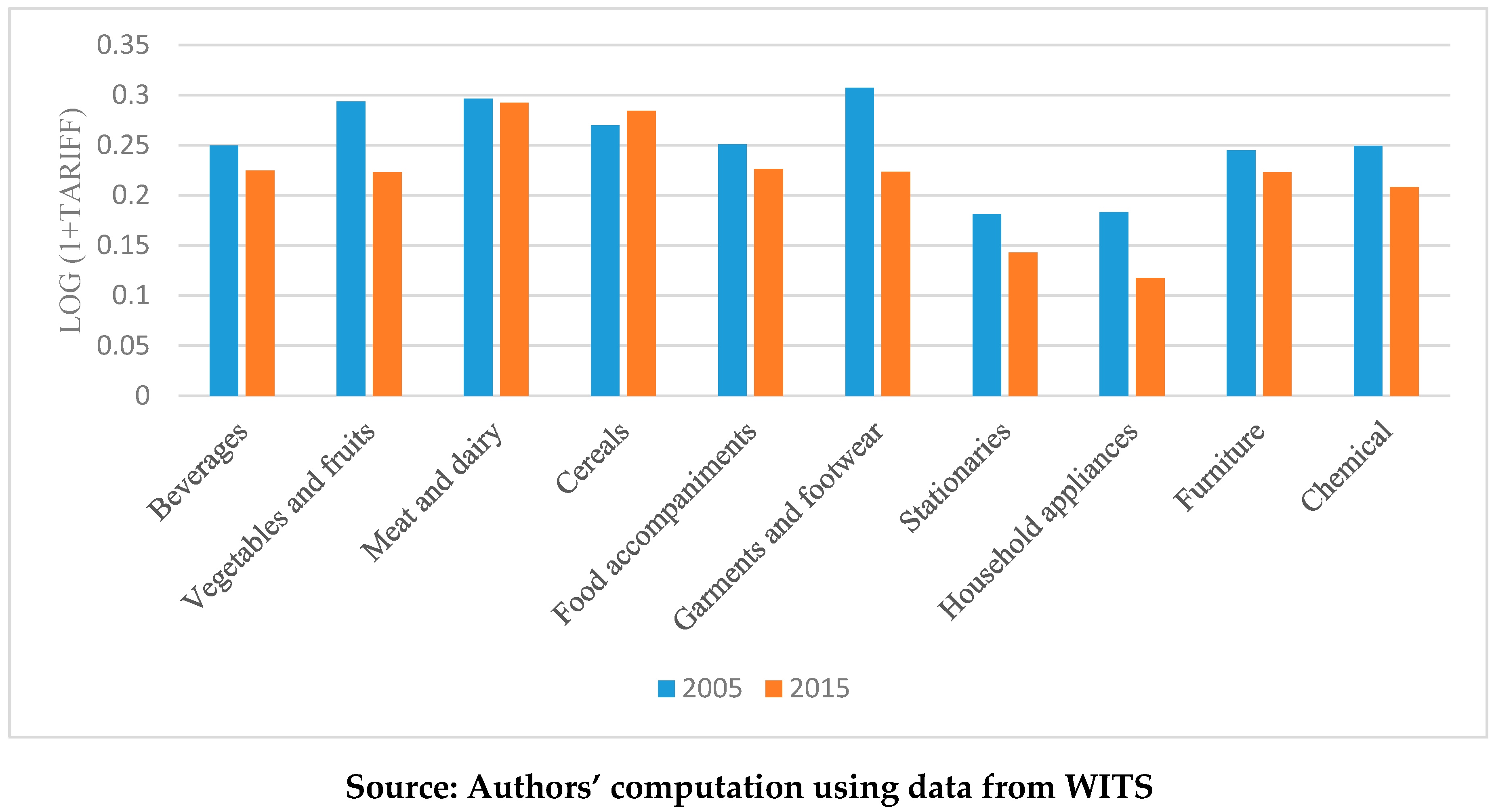

As expected, high import tariffs are observed on agricultural products compared to manufactured products, as shown in

Figure 2. However, there was a general decline in tariffs for the two periods for almost all product categories. An exception is cereals, meat, dairy products, furniture, and other food ingredients. A relatively large decline in tariffs was observed for garments, footwear, vegetables, and fruit. Notably,

Figure 2 shows that although the EAC-CET saw a reduction in import tariffs for many products, on average, the magnitude of the reduction was not very large. However, many products remain highly protected. In terms of industries, manufactured goods are observed to have experienced a higher reduction in import tariffs than agricultural goods.

The country's agricultural sector is highly protected; several agricultural products, such as rice, sorghum, millet, fish, coconut, coffee, and tea saw their tariffs rise by over 50% for the two periods. In particular, rice experienced an increase in import tariffs by 114% which is a reflection of how highly protected the product is. This is expected in a developing country such as Kenya, which tends to protect its agricultural sector to promote domestic production and cushion local farmers against cheaper imports and fluctuations in domestic prices. Some products, such as radio and cellular received complete liberalization, while others, such as bags and belts, did not experience any change in import tariffs. Remarkably, a large number of products consumed by households are final goods. The large number of products whose tariffs are bound in the 25% tariff band depicts this.

In terms of income, workers were classified into three major groups. The first group is skilled versus unskilled workers. Under this classification, workers who have at least completed their primary education are regarded to be skilled. The second classification was informal versus formal workers. Informal workers are those who indicated in the survey that they work in the informal sector (“Jua Kali”), either as employed or self-employed. Formal are those who indicated to work for; the national government, civil service ministries, judiciary, parliament, commissions, state-owned enterprise/institution, teachers service commission, county government, private sector enterprise, international organization/NGO, local NGO, faith-based organization, and formal self-employed. The third classification was workers in the agricultural sector versus the non-agricultural sector. Workers in the agricultural sector were either: small-scale agriculture (employed), large-scale agriculture, pastoralists (employed, and self-pastoralist activities). All these workers were observed in terms of their residence, either rural, urban, or fully urban (Nairobi and Mombasa Counties). Prices may not vary significantly within one single survey to allow for the estimation of price-labor income elasticities (Nicita, 2009). Thus, observations in 2005 and 2015 were stacked together to better capture the effects of prices on labor incomes.

On average the labor incomes of skilled workers, both in rural and urban areas are more than those of unskilled workers. The gap in labor incomes is, however, more pronounced for urban households compared to rural households. Generally, labor incomes for formal workers were higher than for those doing informal jobs. An exception was observed for rural households in 2015, where labor incomes for informal workers slightly increased. Finally, labor incomes for workers in the non-agricultural sector are larger than in the agricultural sector. The number of unskilled workers declined for the two periods, while skilled workers increased as seen in

Table 2. This could be attributed to the introduction and sensitization of free primary education in the country in 2003. While informal workers decreased under job formality, formal workers increased. Further, in the job sector, the number of workers in the agricultural sector declined while the number of workers in the non-agricultural sector grew.

4. Findings

5.1. Tariff-Pass-through Effects

There is a near-one-to-one pass-through effect of tariffs on domestic prices of manufactured goods as seen in

Table 3. The tariff values of manufactured goods were not only smaller before the EAC-CET, but they also experienced a greater reduction after the adoption of the EAC-CET. Likewise, manufactured goods are less affected by intermediary market power than agricultural goods which enhances the pass-through effect. Further, tariff pass-through is higher for manufactured goods because they are mostly consumed in urban areas, where domestic markets are not only closely integrated with international markets, but trade and transaction costs are lower. There was an incomplete pass-through on agricultural goods. Incomplete pass-through is also observed on rural against urban prices. The incomplete pass-through suggests that domestic value chains are lacking competitiveness, either due to low demand elasticity or because sellers retain a significant portion of the reduced price rent at the border. The incomplete pass-through also signifies a significant influence of intermediary market power on agricultural goods. Bergquist and Dinerstein (2020) show that the degree of intermediary market power is very high, where consumers only enjoy 18% of the trade surplus while intermediaries enjoy 72%. External factors, such as foreign prices and exchange rates, push prices of manufactured goods higher than agricultural goods did not adversely affect the welfare of most rural farmers involved in the production of agricultural goods. This shows that most of the commodities imported, and hence more susceptible to the influence of external factors, are manufactured goods. Finally, in terms of EAC borders, the results show that after the formation of the EAC and allowing free movement of goods within the borders, prices of agricultural goods in Kenya slightly reduced due to cheaper imports from Uganda and Tanzania. However, the border effect was not observed to be significant for manufactured goods.

5.2. Price-Labor Income Effects

Trade liberalization was found to have varying effects on different categories of workers, with skilled workers generally benefiting more than unskilled workers as seen in

Table 4. This pattern has also been observed in several other African countries, including Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Ivory Coast, Ethiopia, Gambia, and Madagascar (Nicita et al., 2014). The advantage experienced by skilled workers can be attributed to the fact that industries that directly compete with imports often require a higher level of skills. Additionally, political economies in Sub-Saharan African nations tend to favor skilled laborers, further contributing to the disparity (Nicita et al., 2014). Similar labor income disparities resulting from trade liberalization have been noted in other emerging countries such as China, Indonesia, and Colombia (Fan, Lin, & Lin, 2020; Gaddis & Pieters, 2017). The increase in the relative demand for skilled workers compared to unskilled workers is seen as a key factor in driving the difference in labor incomes (Harrigan & Reshef, 2015). This can be explained by the entry of new firms into skill-intensive industries and the contraction of less skill-intensive non-exporting sectors in response to import competition. The theoretical framework proposed by Chao, Ee, Nguyen, & Yu (2019) supports this argument, suggesting that changes in capital and labor can lead to a gap in labor incomes.

Labor income disparities are also observed between formal and informal workers, where formal workers gained more. The reduction of tariffs on capital goods, raw materials, and intermediate goods may have incentivized firms to shift from the informal to the formal sector, as it became more profitable. This shift is driven by the capital-intensive nature of formal sectors compared to the informal ones. A similar phenomenon was observed in Egypt, where tariff reductions on intermediate products led to a shift towards formal manufacturing industries (Selwaness & Zaki, 2015). Cheaper capital goods and inputs also attract the entry of new firms into the formal sector, leading to increased labor incomes for formal workers compared to informal ones. This effect was observed in Mexico, where tariff cuts increased the likelihood of formal employment in manufacturing industries (Yahmed & Bombarda, 2020).

Trade liberalization under the EAC-CET may have also influenced the composition of the labor market, with some workers shifting from the formal to the informal sector. This shift could result in formal workers having more favorable characteristics compared to average informal workers, such as higher skill levels. The country may also attract the entry of new foreign firms after trade liberalization, which can lead to lower prices and markups for domestic firms (Amiti, Redding, & Weinstein, 2019). This, in turn, may result in reduced labor incomes for workers employed by domestic firms in the informal sector. The impact of trade liberalization on labor incomes varied between non-agricultural and agricultural sectors. Non-agricultural workers experienced significant gains in their labor incomes, while farmers in the agricultural sector did not experience a significant increase. Agricultural commodities remained highly protected, limiting the impact of trade liberalization on agricultural prices. The positive labor income effects in non-agricultural sectors can be attributed to the entry of new manufacturing industries due to cheaper raw materials or shifts of firms from agricultural to non-agricultural sectors. The study also highlighted the influence of transport costs and border clearance effects on labor incomes. Counties adjacent to EAC partner states and major cities experienced a significant positive effect on labor incomes due to lower prices resulting from trade liberalization. However, counties far from the EAC borders or major cities did not observe a substantial increase in labor incomes.

5.3. Welfare Effects

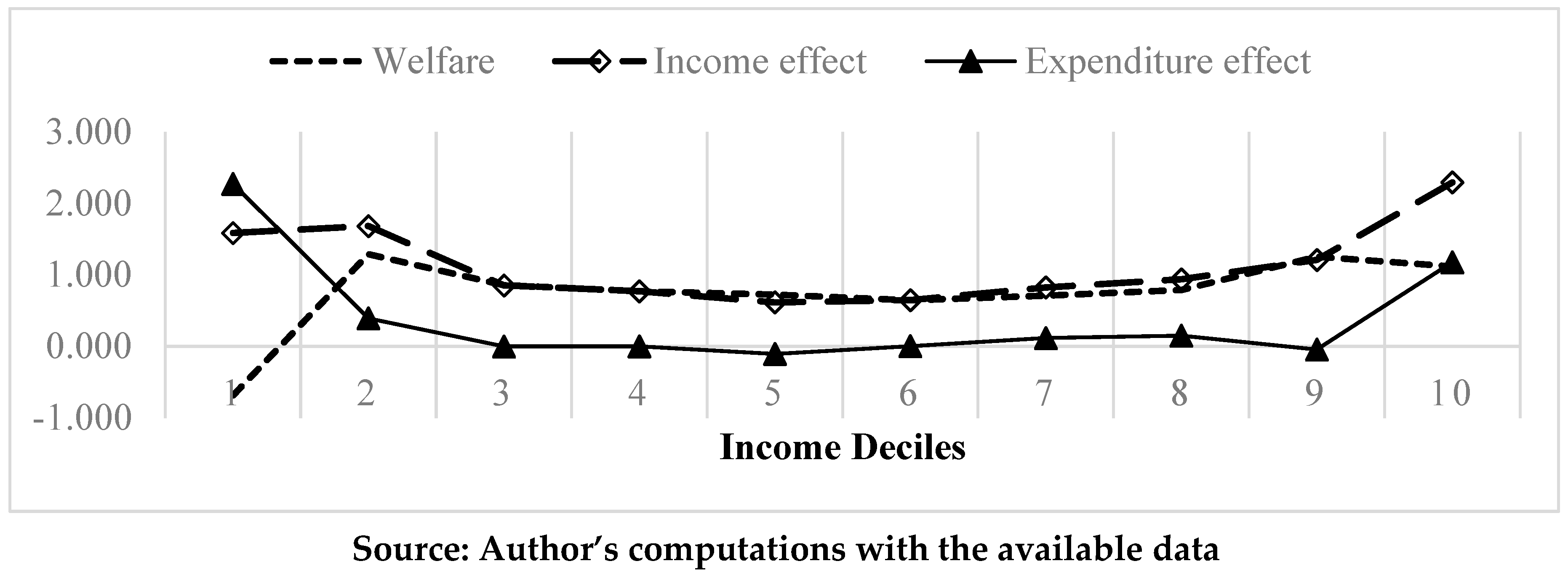

The welfare measure, represented by equation (8), encompasses both the income effect and expenditure effects. To assess welfare, the analysis considered income deciles, household residence, types of goods, and counties with their respective boundaries. The findings presented in

Figure 3 reveal that the expenditure effect is lower than the income effect. This outcome is in line with expectations, as prices exert a negative impact on expenditure while positively affecting income. Nonetheless, trade policies indicate that households derive benefits from reduced expenditure resulting from lower prices (Kareem, 2018). Consequently, it can be inferred that the income effect played a key role in driving the observed welfare gains attributable to the implementation of the EAC-CET. This observation has also been noted by Fajgelbaum and Khandelwal (2016), as well as Borusyak and Jaravel (2021), the latter of whom determined that the expenditure channel is neutral while the income channel yields positive effects.

Notably, the poorest households in the lowest income decile experienced an expenditure effect that surpassed the income effect, leading to a negative welfare estimate. This suggests that the positive income effect resulting from price changes in the two periods was insufficient to counterbalance the negative expenditure effect for rural households. Consequently, trade liberalization implemented under the EAC-CET, which led to a reduction in average prices, did not significantly enhance the welfare of the poorest households in the country. This outcome can be attributed to the fact that, on average, these households possess very low labor incomes in comparison to their expenditures. Conversely, for households belonging to middle-income and upper-income deciles, the welfare estimates were positive, indicating an improvement in their well-being following the adoption of the EAC-CET. The welfare estimates were slightly higher for the top income deciles, implying that the trade policy favored relatively affluent households in the country.

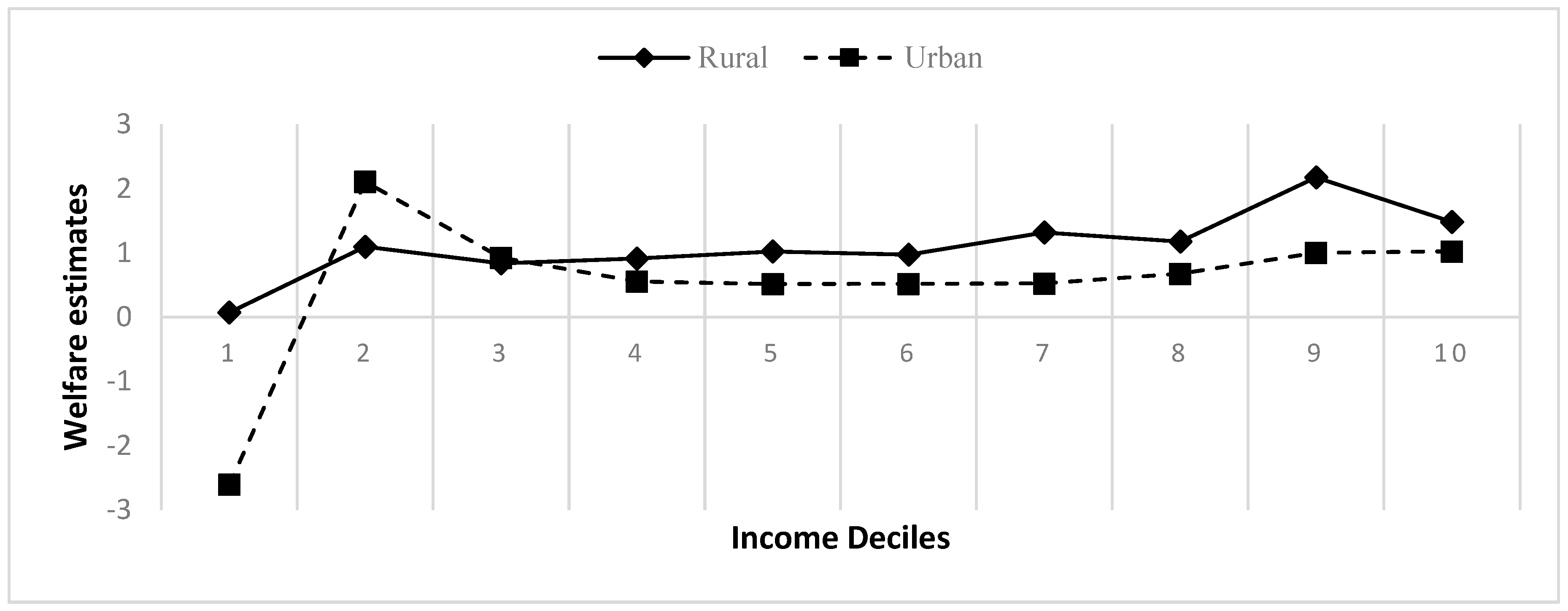

In terms of regions, rural households gained relatively more compared to urban households as seen in

Figure 4. This implies that the EAC-CET is pro-poor (Marchand, 2019). Specifically, the EAC-CET structure relatively favors poorer households compared to richer households in Kenya. This is because households in rural areas are averagely poorer compared to households in urban areas of the country. Since most of the rural households are farmers, they happened to gain more from the EAC-CET because tariffs for most agricultural products on average remained the same while others increased. Nicita et al. (2014) also observed similar observations where poor households in developing countries in Africa gain more than the rich. Specifically households in Madagascar, Cameroon, Burkina Faso, Cote d’Ivoire, and Gambia. The rationale is that most of these countries have a highly protective trade policy for agricultural products. Thus, domestic farmers are cushioned from fluctuations in prices that would be caused by cheaper imports. Lederman and Porto (2016) argues that poor households tend to earn a significant share of their income from the sale of commodities, thus even if prices rise in the expenditure basket; the effect may be ameliorated by the income effect. Farmers in rural areas of Kenya predominantly engage in the cultivation of maize and beans. Consequently, they have derived substantial advantages from the East African Community Common External Tariff (EAC-CET), particularly due to the notable increase in average tariffs imposed on maize, which has been categorized as a sensitive item within the EAC-CET framework. Moreover, the government exercises stringent control over the importation of maize to safeguard domestic farmers against the influx of cheaper imports. The second implication of the results in

Figure 4 is that the effect of the average reduction of prices of manufactured goods, due to the EAC-CET, was more felt in rural areas compared to urban areas. This is so because the average prices of manufactured goods in rural areas are on average lower than average prices in urban areas in Kenya for the sample of products analyzed. The analogy to this is that average income shares from manufactured goods are higher in rural areas compared to urban areas. Prices of manufactured goods in urban areas in Kenya would tend to be higher than in rural areas because of the cost of doing business in urban areas.

In terms of borders, counties on the EAC borders were the most beneficiaries of the EAC-CET as seen in

Table 5. This shows that cheaper imports from the EAC bordering countries Tanzania and Uganda helped to improve the welfare of households in counties that border these countries. The finding also implies that households in these counties gained more because of low transport costs facilitated by small distances between these counties and the neighboring countries. The EAC-CU also helped to facilitate easy cross-border trade as it allowed the free movement of goods and traders within the EAC borders. All these helped to improve the welfare of households in these counties compared to the other counties in the country. The welfare gains for regions closer to the borders relative to those that are far are also observed in other studies in the literature. In China, Zhu et al. (2016) showed that farmers who were located in the coastal areas gained more from tariff liberalization compared to their counterparts in the inland provinces. In Mexico, Nicita (2009) showed that the states that were near the US borders benefited more from trade liberalization compared to the other states in the country. Welfare gains in major cities were the least, this shows that other costs in major cities weakened the positive effect of the EAC-CET in major cities of the country. These costs are mainly in the form of transaction costs, transport costs, and costs of intermediaries.

Equation (13) was estimated to investigate whether the welfare estimates varied with other types of socio-demographic factors and labor characteristics. The results highlighted in

Table 6 show that; age was negatively associated with welfare, especially in rural areas. This implies that households headed by older persons in rural areas lost compared to households headed by younger households in rural areas. The analogy to this is that younger farmers in rural areas reap more from the EAC-CET compared to older ones.

Gender was positive for urban households, showing that households whose heads are male gained more from the EAC-CET compared to families headed by females. This comes about due to the labor income effect, where male workers tend to earn more than female workers. Household sizes are observed to matter in the effect of the EAC-CET on household welfare. In rural areas where household size is large, the welfare estimate was negative while in urban areas where household size was small, the welfare effect is positive and statistically significant. The unskilled workers in rural areas gained more compared to skilled workers. This is expected as most of the farmers who are in rural areas tend to be unskilled. As such, the gains observed for rural farmers in

Figure 4 tend to have mainly gone to the unskilled workers. The sector dummy is negative and statistically significant for urban households. This shows that workers in non-agricultural sectors in urban areas gained more compared to workers in agricultural sectors in the same areas. Finally, the signs of the constant coefficient show that on average, rural households gained more from the EAC-CET compared to urban households.

6. Conclusion

The findings of this study shed light on the effects of the EAC-CET on household welfare in Kenya. The analysis reveals several important patterns and impacts that resulted from the implementation of the EAC-CET. Firstly, there was a near-one-to-one pass-through effect of tariffs on domestic prices of manufactured goods, indicating that tariffs had a significant influence on the prices of these goods. On the other hand, agricultural goods experienced incomplete pass-through, suggesting a lack of competitiveness in domestic value chains. The pass-through effects also highlighted the influence of intermediary market power, with intermediaries benefiting disproportionately from trade policies. Secondly, regarding labor income effects, trade liberalization under the EAC-CET had varying impacts on different categories of workers. Skilled workers tend to have benefited more than unskilled workers. This was so because industries that directly compete with imports often require higher levels of skills. This pattern is also observed in other African countries and emerging economies as well. Additionally, formal workers gained more than informal workers, as tariff reductions on capital goods and inputs incentivized firms to shift to the formal sector. This shift is mainly driven by the capital-intensive nature of formal sectors and the entry of new firms. The welfare effects of the EAC-CET indicate that while the income effect positively contributed to household welfare, the expenditure effect exerted a negative impact. The positive income effect resulting from price changes outweighed the negative expenditure effect, leading to improved welfare for households in the middle and upper-income deciles. However, the poorest households in the lowest income decile experienced negative welfare effects. This was so because the positive income effect was insufficient to offset the negative expenditure effect. This suggests although the EAC-CET reduced the average prices of commodities, it did not significantly enhance the welfare of the poorest households. Finally, the welfare gains were more pronounced in rural areas compared to urban areas, indicating a pro-poor impact of the EAC-CET. Additionally, counties on the EAC borders benefited more from cheaper imports and lower transport costs, This led to increased welfare for households in these regions than regions that were far from the borders of the country.

The findings of this study have important policy implications, first to address the incomplete pass-through effects observed for agricultural goods, efforts should be made to improve the competitiveness of domestic agricultural value chains. This can be achieved through targeted interventions such as improving infrastructure, reducing transaction costs, and promoting technology adoption. Secondly, given the differential impacts on skilled and unskilled workers, policies should focus on promoting skill development programs to enhance the capabilities of the workforce. Additionally, efforts should be made to reduce labor income disparities, particularly between formal and informal workers, by providing support for formalization and improving working conditions in the informal sector. Third, policies should be designed to target the welfare of the poorest households, particularly those in rural areas. This can be achieved through targeted social protection programs and measures to improve productivity and income-generating opportunities for rural farmers. Finally, to ensure balanced and inclusive development, policies should be implemented to support domestic industries to improve the value chains of markets.

References

- Amiti, M., Redding, S. J., & Weinstein, D. E. (2019). The impact of the 2018 tariffs on prices and welfare. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 33(4), 187–210. [CrossRef]

- Balistreri, E. J., Jensen, J., & Tarr, D. (2015). What determines whether preferential liberalization of barriers against foreign investors in services are beneficial or immizerising: Application to the case of Kenya. Economics, 9. [CrossRef]

- Balistreri, E. J., Maliszewska, M., Osorio-Rodarte, I., Tarr, D. G., & Yonezawa, H. (2016). Poverty and Shared Prosperity Implications of Deep Integration in Eastern and Southern Africa. Poverty and Shared Prosperity Implications of Deep Integration in Eastern and Southern Africa, (May). [CrossRef]

- Balistreri, E. J., Rutherford, T. F., & Tarr, D. G. (2009). Modeling services liberalization: The case of Kenya. Economic Modelling, 26(3), 668–679. [CrossRef]

- Bergquist, L. F., & Dinerstein, M. (2020). Competition and Entry in Agricultural Markets: Experimental Evidence from Kenya†. American Economic Review, 110(12), 3705–3747. [CrossRef]

- Borraz, F., Rossi, M., & Ferres, D. (2012). Distributive Effects of Regional Trade Agreements on the ‘Small Trading Partners’: Mercosur and the Case of Uruguay and Paraguay. Journal of Development Studies, 48(12), 1828–1843. [CrossRef]

- Borusyak, K., & Jaravel, X. (2021). The Distributional Effects of Trade: Theory and Evidence from the United States. NBER Working Paper Series. [CrossRef]

- Cabalu, H., & Rodriguez, U.-P. (2007). Trade-offs in Trade Liberalization: Evidence from the Philippine 2005 Tariff Changes. Journal of Economic Integration, 22(3), 637–663. [CrossRef]

- Deaton, A. (1989). Rice prices and income distribution in Thailand: a non-parametric analysis. Economic Journal, 99(395 Supp), 1–37. [CrossRef]

- Deaton, A. (2018). The Analysis of Household Surveys: A Microeconometric Approach to Development Policy. Retrieved from International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank website: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/30394.

- Deaton, A., & Zaidi, S. (2002). Guidelines for Constructing Consumption Aggregates for Welfare Analysis. In LSMS Working Paper. Washington D.C.

- Fajgelbaum, P. D., & Khandelwal, A. K. (2016). Measuring the unequal gains from trade. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 131(3), 1113–1180. [CrossRef]

- Fan, H., Lin, F., & Lin, S. (2020). The hidden cost of trade liberalization: Input tariff shocks and worker health in China. Journal of International Economics, 126, 103349. [CrossRef]

- Gaddis, I., & Pieters, J. (2017). The Gendered Labor Market Impacts of Trade Liberalization Evidence from Brazil. Journal of Human Resources, 52(2), 457–490. [CrossRef]

- Gasiorek, M., Byiers, B., Rollo, J., & CUTS International, . (2016). Regional integration, poverty and the East African Community: What do we know and what have we learnt? European Centre for Development Policy Management, (202), 1–52. Retrieved from http://ecdpm.acc.vpsearch.nl/wp-content/uploads/DP202-Regional-Integration-Poverty-East-African-Community-November-2016.pdf.

- Ghahremanzadeh, M., Malakshah, S. K., & Pishbahar, E. (2017). The Extent of Tariff Pass-Through to Agricultural Prices and Wage in Urban and Rural Regions in Iran. European Online Journal of Natural and Social Sciences, 6(3), 447–458.

- Harrigan, J., & Reshef, A. (2015). Skill-biased heterogeneous firms, trade liberalization and the skill premium. Canadian Journal of Economics, 48(3), 1024–1066. [CrossRef]

- Kareem, I. O. (2018). The Impact of Common External Tariffs on Household’s Welfare in a Rich African Country with Poor People. Advances in Economics and Business, 6(2), 114–124. [CrossRef]

- Karingi, S., Pesce, O., & Sommer, L. (2016). Regional opportunities in East Africa. In WIDER Working Paper 2016 / 160. Helsinki.

- Khorana, S., Kimbugwe, K., & Perdikis, N. (2009). Assessing the Welfare Effects of the East African Community Customs Union’s Transition Arrangements on Uganda. Journal of Economic Integration, 24(4), 685–708. [CrossRef]

- Lederman, D., & Porto, G. (2016). The price is not always right: On the impacts of commodity prices on households (and countries). World Bank Research Observer, 31(1), 168–197. [CrossRef]

- Marchand, B. U. (2012). Tariff pass-through and the distributional effects of trade liberalization ☆. Journal of Development Economics, 99(2), 265–281. [CrossRef]

- Marchand, B. U. (2017). How does international trade affect household welfare? IZA World of Labor, (August), 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Marchand, B. U. (2019). Inequality and trade policy: the pro-poor bias of contemporary trade restrictions. Review of Income and Wealth, 65(1–306), 7–12. [CrossRef]

- McIntyre, M. A. (2005). Trade Integration in the East African Community: An Assessment for Kenya. IMF Working Papers, 05(143), 1. [CrossRef]

- Moratti, M., & Natali, L. (2012). Measuring Household Welfare. In Innocenti Working Papers, no. 2012-04.

- Nicita, A. (2009). The price effect of tariff liberalization : Measuring the impact on household welfare ☆. Journal of Development Economics, 89(1), 19–27. [CrossRef]

- Nicita, A., Olarreaga, M., & Porto, G. (2014). Pro-poor trade policy in Sub-Saharan Africa. Journal of International Economics, 92(2), 252–265. [CrossRef]

- Omolo, M. W. O. (2012). The Impact of Trade Policy Reforms on Households : a Welfare Analysis for Kenya. In 15th Annual conference on global economic analysis. Geneva, Switzerland.

- Onyango, C., & Mugoya, P. (2009). An Evaluation of the Implementation and Impact of the East African Community Customs Union. Arusha.

- Porto, G. G. (2006). Using survey data to assess the distributional effects of trade policy. Journal of International Economics, 70(1), 140–160. [CrossRef]

- Selwaness, I., & Zaki, C. (2015). Assessing the impact of trade reforms on informal employment in Egypt. Journal of North African Studies, 20(3), 391–414. [CrossRef]

- Shinyekwa, I., & Katunze, M. (2016). Assesment of the Effects of the EAC Common External Tariff Sensitive Products List on the Performance of Domestic Industries, Welfare, Trade and Revenue. Economic Policy Centre Research, 129.

- Shinyekwa, & Othieno, L. (2013). Trade creation and diversion effects of the East African Community regional trade agreement: A gravity model analysis. Economic Policy Centre Research, (112).

- Siddiqui, K. (2015). Trade Liberalization and Economic Development: A Critical Review. International Journal of Political Economy, 44(3), 228–247. [CrossRef]

- Vo, T. T., & Nguyen, D. X. (2021). Impact of Trade Liberalization on Household Welfare: An Analysis Using Household Exposure-to-Trade Indices. Social Indicators Research, 153(2), 503–531. [CrossRef]

- Yahmed, B. S., & Bombarda, P. (2020). Gender, Informal Employment and Trade Liberalization in Mexico. World Bank Economic Review, 34(2), 259–283. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J., Yu, W., Wang, J., & Elleby, C. (2016). Tariff Liberalisation, Price Transmission and Rural Welfare in China. Journal of Agricultural Economics, 67(1), 24–46. [CrossRef]

| 1. |

Roy’s identify is given by:

|

| 2. |

Hotelling Lemma is given by:

|

| 3. |

Because this price is estimated with the tariff of 2005 included. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).