1. Introduction

In recent years, with the deepening appreciation of the concept and connotation of cultural heritages, a series of trans-regional heritages such as cultural routes and linear heritage especially the canal, reflecting the unity and continuity of natural and human landscapes[

1], and embodying the dynamics of social, economic and cultural development of human beings in various periods of history[

45], has become the rather hot topic of discussion in the field of heritage conservation both in China and beyond[

29]. After being inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List, academia has conducted comprehensive research and practices on the Chinese Grand Canal in different aspects: such as the value system of cultural heritages along the route [

3], the development and performance of tourism products and trails [

44], achievements and shortcomings of the conservation process towards the Canal [

41]. Most of the existing studies focus on explaining its cultural, economic, and political values as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, analyzing the advantages and disadvantages of its cultural tourism products and markets from a long-term perspective, or examining its profound impact on China's north-south exchanges, ethnic integration and national unity from ancient times to the present, but seldom of them focused on the emergence and disappearance of industrialization along the Canal within a typical, widespread and far-reaching cultural change over industrial lands of China after 2000s, which is a research gap for the field of Canal.

Like the functions of canals in terms of developing industries in Great Britain [

42], Canada [

33] and others, restricted by the means of transport and productivity levels, Chinese Grand Canal has been the most important support for the developments of industrialization in the cities along its route for hundreds of years [

30]. After 1949, the central government of PRC proposed the development of coastal industries, which offered quite an opportunity for cities like Hangzhou and even the whole Zhejiang Province. In order to change from a consumption-oriented city to a production-oriented city as soon as possible, Hangzhou, taking its advantages of land and water transportation, began to lay out large numbers of modern industries along the Canal from 1951. Geographically speaking, Hangzhou section mainly runs through four districts of Linping, Yuhang, Gongshu and Shangcheng. It starts from Tangxi Town of Linping district in the north and ends at the Qiantang River of Shangcheng district in the south, with a total length of about 39 kilometers. And Gongshu district, which takes the longest part of it with a length of 27 kilometers, has deployed the majority of industrial lands of the whole city [

4], and almost all of them disappeared after the 2000s. In macroscopical sight, in the late 20th and early 21st centuries, some of China's major cities gradually entered the phase of counter-industrialization and de-industrialization, and began to focus on the development of cultural and creative industries. In 2010, China's 12th Five-year Plan even proposed to promote the cultural industry as the pillar industry of the national economy, which means that the added value of it should account for more than 5% of GDP, while in 2009 the added value of China's whole cultural industry accounted for about 2.5% of GDP. In this context, cities like Hangzhou, while water bodies in cities become high-quality tourism resources after 2000s, have implemented diversified cultural practices via a great deal of the left or forsaken industrial lands mainly along the Grand Canal after industrial recession. Therefore, this research will try to access the process, accomplishments, and cultural loss of this cultural change.

2. Materials and Methodology

2.1. Study Area

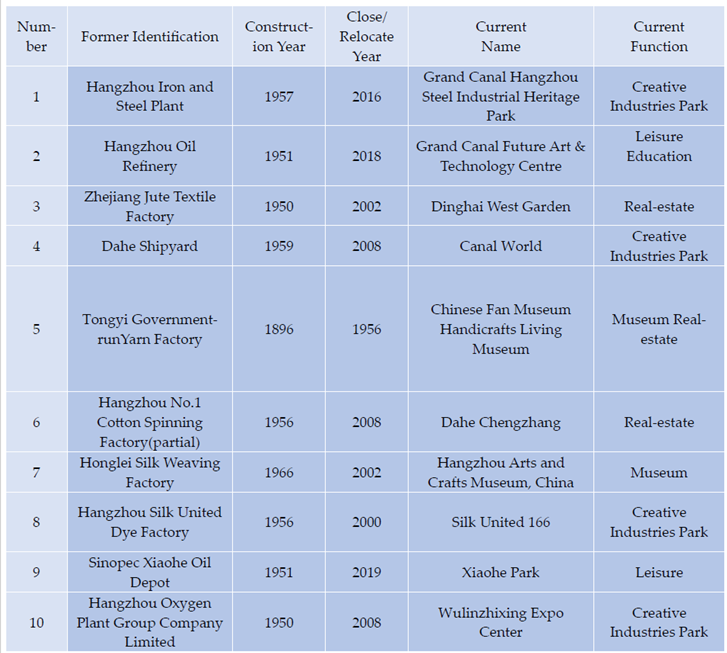

Historically speaking, Hangzhou section originated in the Spring and Autumn period (5th century BC), took shape in the Sui dynasty (6th century AD), thrived in the Song and Yuan dynasties, and flourished until the Ming and Qing dynasties. In terms of geographical features, it flows through a subtropical monsoon climate with distinct four seasons, moderate annual temperatures, significant monsoons, and abundant rainfall. As the capital of Zhejiang Province, as well as its political, economic, and cultural center, Hangzhou's industrialization and cultural traditions have been heavily dependent on the Grand Canal for a long time. The industrialization and industrial lands along the Hangzhou section of the Grand Canal were mainly distributed in the northeast of Hangzhou City, Zhejiang Province, along the southeast coast of China(120°7’30’’E-120°11’30’’E,30°18’0’’N-30°21’30’’N). Consequently, its urbanization rate has reached as high as 84.0% at the end of 2023, and it has been remembered as one of the most famous cultural cities domestically and beyond with three sites successfully inscribed on the World Heritage List. Meanwhile, the high urbanization rate and rapid development of the urban economy have led to a shortage of construction land and great protection pressure on cities/towns along Hangzhou section. This not only accelerated the cultural changes with the deconstruction of original social structure along the route, but also quickly demolished the industrialization traces and industrial lands to make cultural heritage sites and streets instead. In April 2017, Hangzhou issued the Regulations on the Protection of the Grand Canal World Heritage in Hangzhou, aiming to strengthen the protection of the Grand Canal World Heritage in China, promote the preservation, research and display of the outstanding values of the Grand Canal World Heritage in China, and give full play to the role of the cultural heritage in the city's development. The year 2024 marks the 10th anniversary of the successful nomination of the Grand Canal of China as a World Heritage Site. We deliberately selected 10 typical factories or plants to analyze the distinctive industrial past and cultural practices on industrial lands along Hangzhou section (see

Figure 1).

2.2. Data Resources and Acquisition

The 10 sites were mainly selected from relevant Chinese national and provincial industrial heritage lists, and the basic information of them was obtained from the Report on Hangzhou Industrial Heritage General Survey. The photos and images were mainly gained from fieldwork with the use of drones by the authors. The attribute information, like latitude and longitude, comes from Google Earth, while the comprehensive information on the utilization over the years was acquired from Hangzhou Urban Construction Archives, Hangzhou Urban Archives, etc. Via a Chinese GIS software of Rivermap

1, remote sensing images covering industrial remains (years 2000,2010 and 2020) were acquired and analyzed. The data on the land use status of industrial remains and their surroundings (2020) were obtained from Hangzhou Natural Resources Bureau, which is accurate and reliable. The data of the radar point cloud were collected via Dajiang drone of M300 RTK, analyzed via software of DJI Terra

2. Meanwhile, we implemented more than 20 times of field work, close investigation and market research towards the 10 cases individually or as one group. And for objectively and thoroughly evaluate the selected sites especially for factors and the corresponding scores, we collected and analyzed the consultation reports and mark sheets from 20 major experts in the fields of industrial heritages and canal tourism at a distance or in the presence jointly.

Additionally, based on official historical archives, the representative figures, events and photos of the cultural change over the industrial lands of the study area could be organized at an early stage. In terms of its inside and subtle knowledge and information, especially local anecdotes, would be gained and analyzed via online and offline investigation, and its latest situation was acquired from close fieldwork and surveys conducted by authors. After that, the comparative studies on the selected sites were completed, with the highlights on the indicators regarding the authenticity and integrity of the industrial heritages. Consequently, the cultural practices were generally divided into three types, according to which the problems were sorted out and suggestions for them were offered in turn.

2.3. Methodology

2.3.1. Flowchart of This Research

Besides comprehensive literature analysis, this research was completed mainly through three steps (see

Figure 2). Firstly, we monitored the dynamic land use of the selected industrial lands with utilization of High-resolution Satellite Imagery (HRSI) from 2000 to 2020, as well as its land use data of 2020 in detail, to highlight the changes in and after industrialization. Secondly, after the collection and analysis of almost all the relevant archives and the conduction of individual/collective fieldwork for nearly two years, close and deep investigations were conducted over the ten cases and beyond. Thirdly, we made a comparison between the ten cases, and divided them into three types within the context of cultural change based on the evaluation of factors and scores to offer our suggestions for the problems afterward.

2.3.2. Dynamic Monitoring of Land Use of Selected Industrial Lands

A dynamic and real-time updatable conservation methodology was applied for recording and interpreting the changes in area and usages of creation, formation and evolution of the selected ten industrial lands along the Hangzhou section. Collecting HRSI from 2000 to 2020 and land use information of 2020 through local government departments, relevant archives and local histories, etc., multiple industrial land use changes are detected. Also, a lidar scanner was used to scan the indoor and outdoor surfaces of the existing workers’ residential buildings, to obtain point cloud data on the surfaces of the buildings, to capture colour information for the point cloud data, to correspond to the texture and geometric characteristics of the buildings, and to pre-process the point cloud data to achieve data optimization, also to ultimately generate a complete point cloud data file of the workers’ residential buildings attached to the industrial lands.

2.3.3. Comprehensively Assess Cultural Change with Factors and Scores

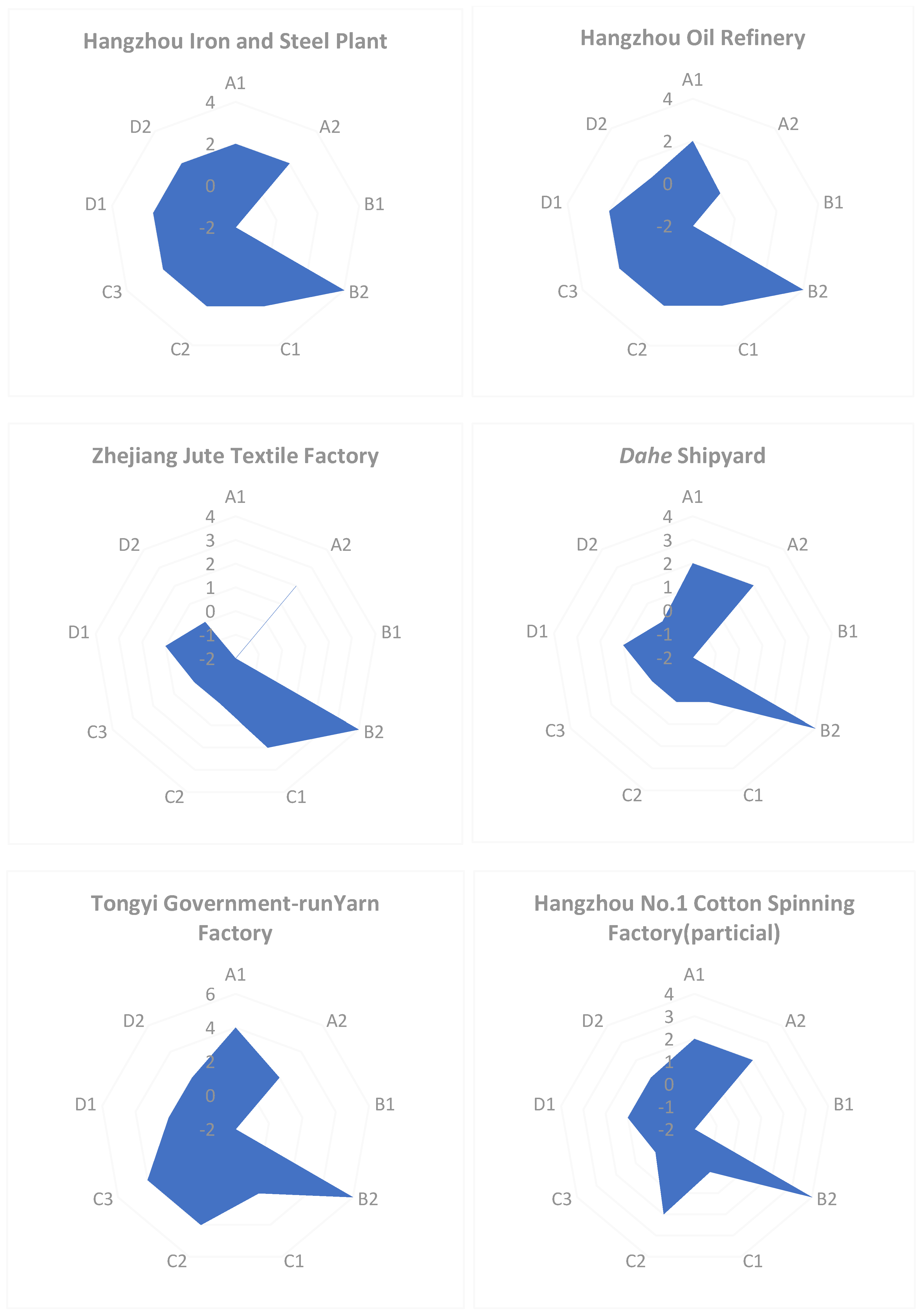

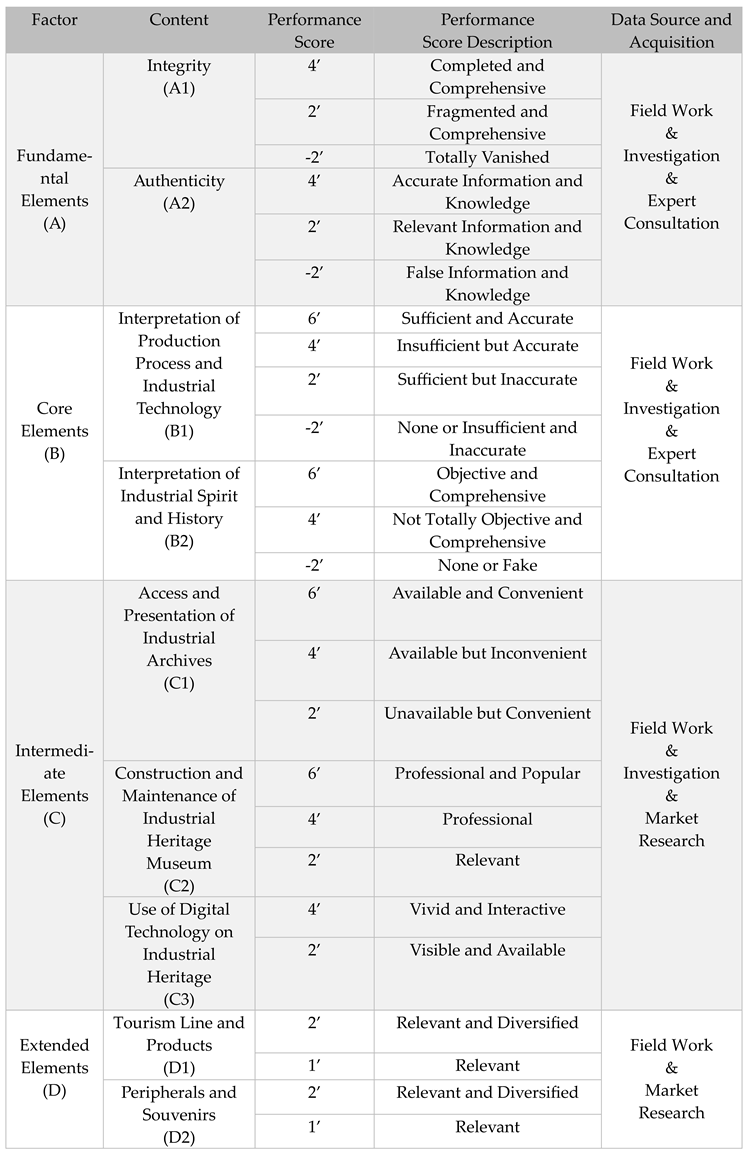

For comprehensively assessing the cultural change of the 10 sites, we designed a mark sheet with factors and scores (see

Table 1). Fundamental Elements(A) In terms of the very first factor, we briefly introduced Integrity(A1) and Authenticity(A2) from the evaluation system of UNESCO World Heritage as two sub-factors within it for the appraisal of the extent of the damage towards the heritage itself and the authenticity of everything presented. And the criterions A1/A2 were marked according to whether the heritage is completed and comprehensive, as well as offers accurate information and knowledge, with scores of 4’/2’/-2’ respectively. Core Elements(B) B assumes the most prominent and important cultural characteristics of industrial heritages. And its first sub-factor is Interpretation of Production Process and Industrial Technology(B1), which was scored 6’/4’/2’/-2’ via the criterions of Sufficient and Accurate/Insufficient but Accurate/Sufficient but Inaccurate/None or Insufficient and Inaccurate. Similarly, Interpretation of Industrial Spirit and History(B2) was marked 6’/4’/-2’ according to the criterions of Totally Objective and Comprehensive/Not Totally Objective and Comprehensive/None or Fake. Intermediate Elements(C) Archives, museum and digitalization are the most common medium via which industrial heritages could be mostly interpreted and promoted. Therefore, three sub-factors successively are Access and Presentation of Industrial Archives(C1) to mark 6’/4’/2’ according to the extent of availability and convenience, Construction and Maintenance of Industrial Heritage Museum (C2) to score 6’/4’/2’ by evaluating the degree of professionalism and number of visitors, Use of Digital Technology on Industrial Heritage(C3) to score 4’/2’ mainly depending on the digital performance. Extended Elements(D) What is well-accepted and convinced is the closely mutually beneficial relationship between industrial heritages and cultural tourism settings. Therefore, Tourism Line & Products (D1) and Peripherals & Souvenirs (D2) are determined as the extended elements. And the case will be scored 2’ or 1’ when offering relevant & diversified or only relevant D1/D2 respectively.

3. Results and Analysis

3.1. Assess the Industrial Past of Industrial Lands along Hangzhou Section

3.1.1. How Chinese Grand Canal Supported and Shaped the Industrialization of Hangzhou

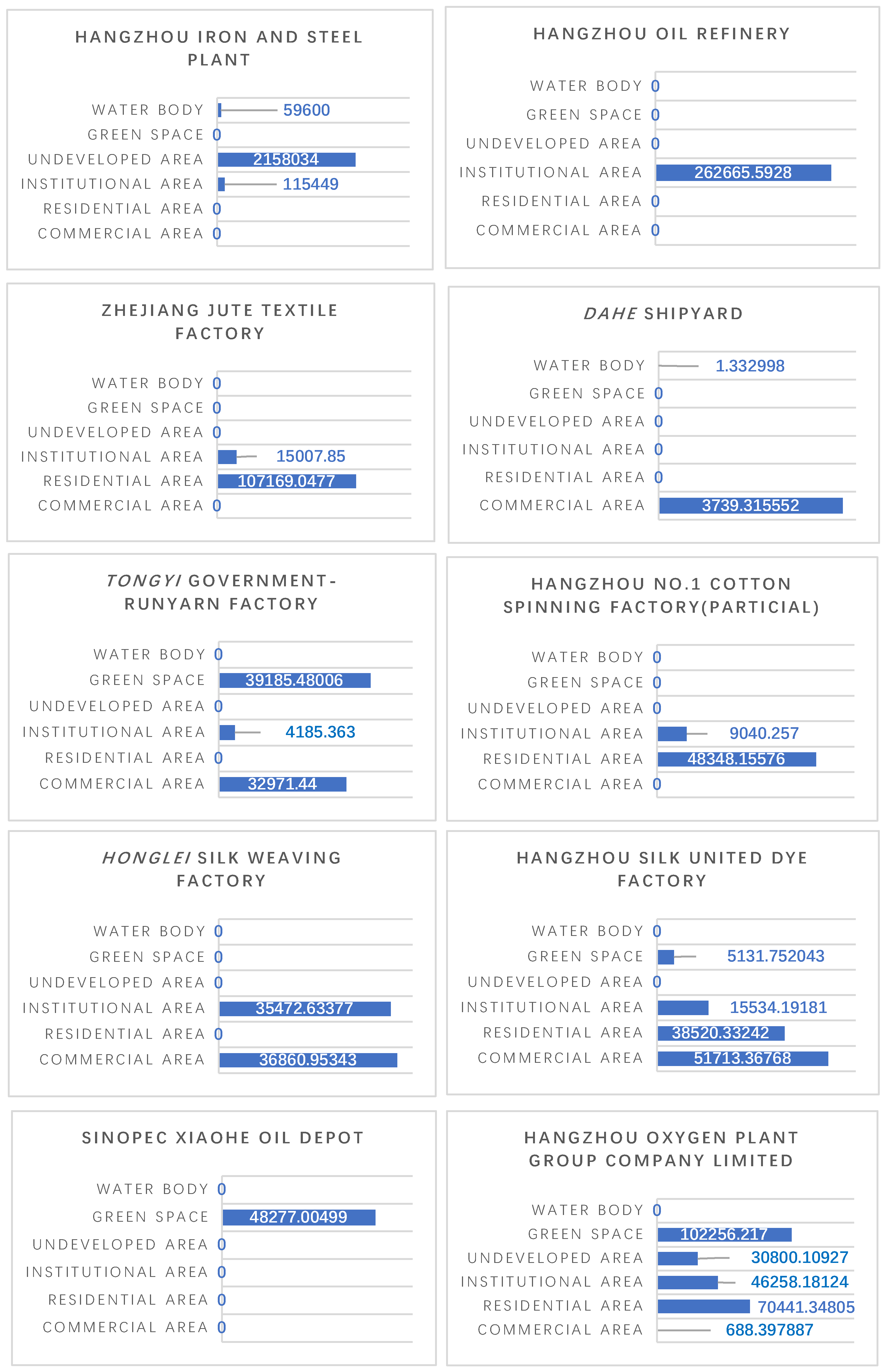

Where there is a canal, there is a wharf, and where there is a wharf, there is industrial development and gathering of people. As the southernmost point of Chinese Grand Canal, Hangzhou section of it has witnessed the industrialization and deindustrialization of the whole city. The combination of HRSI (see

Figure 3) illustrates the Land Use Changes (LUC) on the selected ten cases. Based on it, the exact area of different new uses of the cases on 2022 was counted separately (see

Figure 4). The data and results clearly present the prominent cultural changes over industrial lands along Hangzhou section. With the disappearance of most industries, the new usages especially cultural functions have been attached to the former industrial lands. Besides real estate, museums, parks, and expo centers were the main approaches for regenerating the space after the industrial recession of Hangzhou section (see

Table 2). But before the decline, Chinese Grand Canal has greatly supported and shaped the industrialization of Hangzhou.

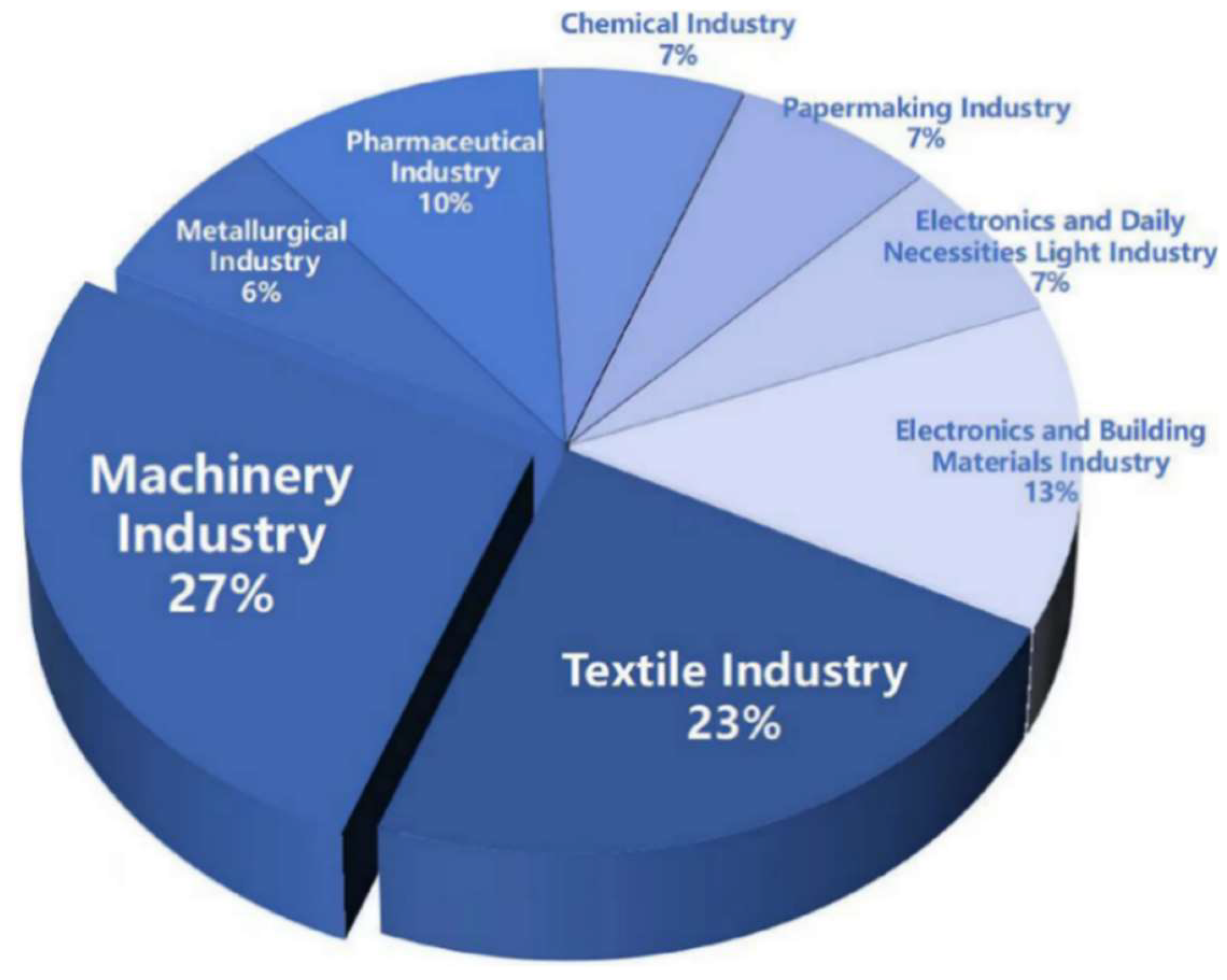

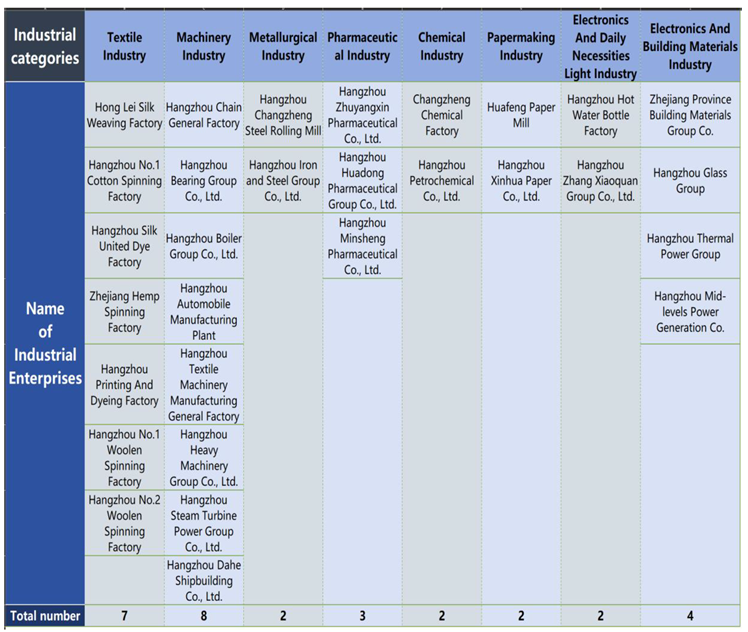

Since the middle of the Ming Dynasty, the sprout of capitalism, mainly focused on the silk weaving industry, has emerged along the Hangzhou’s Grand Canal. During the period of the late Qing Dynasty and the Republic of China, relying on water transportation of the Canal, the modern industrialization process in Hangzhou struggled to advance amidst the flames of war, which shaped the Gongshu district as the cradle of Hangzhou’s modern industries. In 1949, the total industrial output value of Zhejiang Province was only 410 million yuan, the scale of enterprises and the mode of production still depended on small and scattered handmade workshops. And the secondary industry accounted for only 8.0 percent of whole provincial GDP, while agriculture accounted for 68.5 percent. In order to change this unfavorable situation of the excessive proportion of the first industry, as the capital city of Zhejiang Province, Hangzhou naturally accelerates the industrialization process. In 1959, Hangzhou proposed to construct a “comprehensive industrial city” based on “heavy industry”, which was decisive for the evolution of Hangzhou’s urban space. According to statistics, the layout of Hangzhou's eight industrial categories included textiles, machinery, metallurgy etc., among which the textile and machinery industries occupied half of Hangzhou's whole pack of industrial systems at that time (see

Figure 5). After that, 7 major industrial areas and 3 industrial storage areas were deployed and invested in the city, and more than 8 of them were located along the Hangzhou section.

Hangzhou section experienced Westernization Movement and the rise of national industries at an early age around the 1910s, which has shaped Hangzhou as a city with a long history of industrial development and one of the birthplaces of China’s ethnic industry and commerce. After the founding of PRC in 1949, reformation of all public-private joint partnerships to state-run factories was commenced, and the historical tradition of light textile industries was continued comprehensively. By the 1960s and 1970s, factories like Zhejiang Jute Textile Factory, Hangzhou Silk United Dye Factory, Hangzhou No. 1 Cotton Textile Factory (former Tongyi Government-runYarn Factory) were successively started, along with the development of heavy industries such as Hangzhou Iron & Steel Factory and Hangzhou Oil Refinery etc. After that, Gongshu district soon became the industrial centre of Hangzhou, contributing 60% of the city’s gross industrial output and emitting 70% of the exhaust and dust with factories along the canal in it. In the 1980s and 1990s, due to the impact of a market-oriented economy and the reconstruction of state-owned enterprises, traditional industries especially the light textile industry there gradually declined and entered a recession due to the shift from labor-intensive industry to a service economy along the Canal, resulting in factory stagnation and worker unemployment. All these made Gongshu district to be remembered as a polluted and nasty shantytown where the underclass lived with a mixed population and a shortage of living infrastructure and public space. Then, tertiary industries such as tourism and creative industries commenced promptly with emphasizes on the reuse, transformation, or replacement of most discarded factories along the canal. The districts along the Canal like Gongshu had been shaped as an important birthplace of industrial base in Hangzhou and even in Zhejiang Province, and with more than one hundred years of industrial development, Gongshu industry started from textile industry and machinery industry, to pharmaceutical and chemical industry, paper industry, and gradually established a relatively complete industrial system. After the founding of PRC, from the very First Five-year Plan (1953-1957) onwards, Chinese government has attached great importance to the construction of the industrial system for Hangzhou mainly with the support of the Canal, and Gongshu has been determined as the main industrial development area of the whole city. Though limited resources, Hangzhou section have formed an almost complete modern industrial system with 39 major industrial categories and almost full coverage of medium/ small industrial categories. Among the major industrial products, the output of Gongshu once ranked first in the whole country and beyond (see

Figure 6).

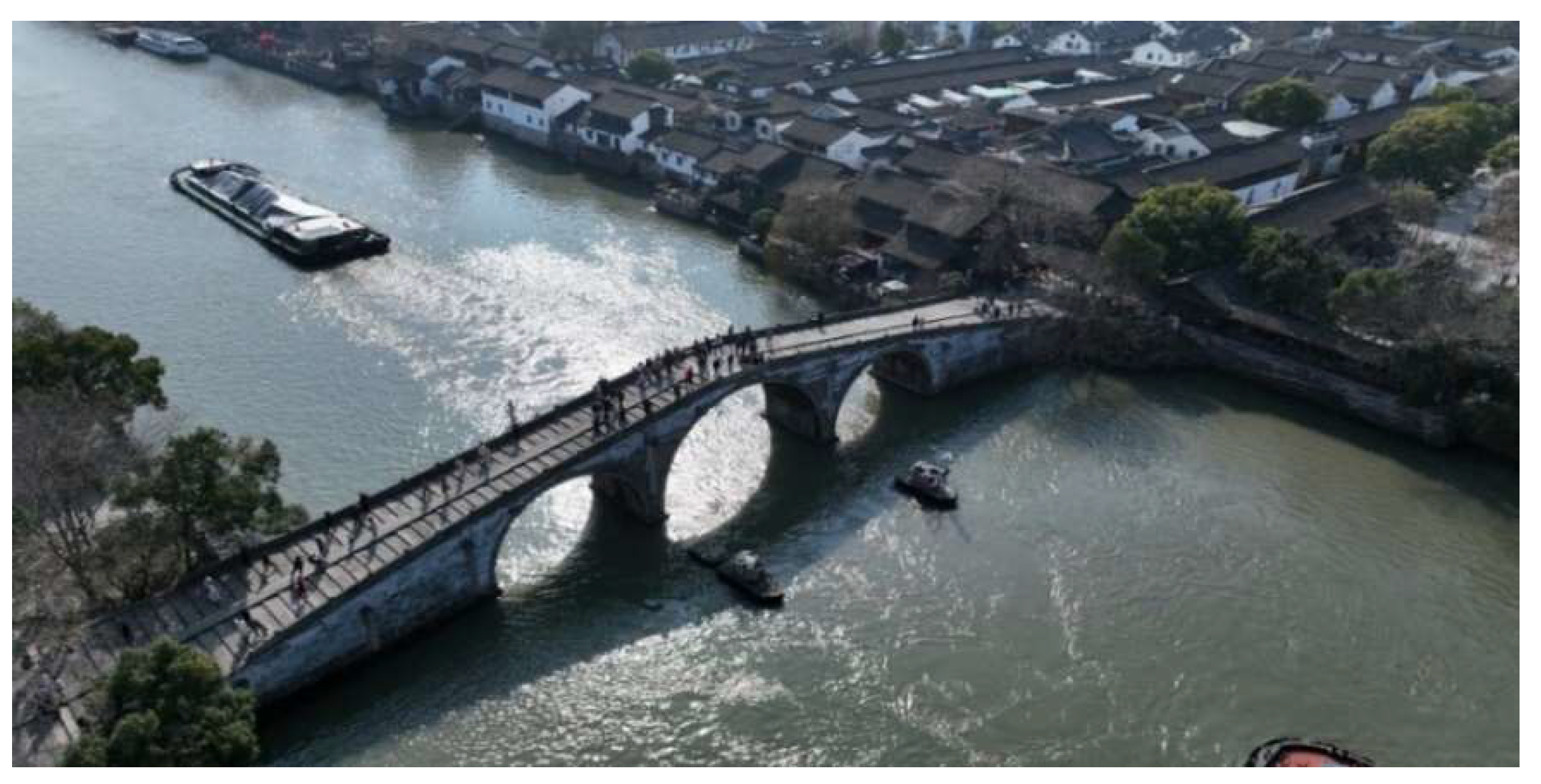

Thanks to the Canal, the area around Gongchen Bridge (a landmark of Hangzhou’s Canal even the whole city, see

Figure 7) became the most important basement of Hangzhou’s modern industry after 1950s (see

Table 3). In its heyday of 1980s, the industrial output value along the Canal and its region accounted for 60% of Hangzhou's main urban area, two-thirds of the city's main urban area's coal combustion was consumed there, and nearly 70% of emissions and dust pollution also come from there. These industries not only provide Hangzhou with significant GDP, tax revenue and jobs, but also create huge amounts of coal ash, sewage and soot. Around 2005, the water quality of all 61 waterways connecting the Grand Canal in Hangzhou city was below the class-5 water quality standard. The deterioration of the environment forced the Hangzhou government to decide to gradually close or relocate industrial enterprises along the Grand Canal in the main urban area, and the construction of an eco-friendly city and the restoration of the environment of the Grand Canal became the new development mission at that time.

3.1.2. Industrial Heritage from Industrial Lands after De-Industrialization in Hangzhou Section

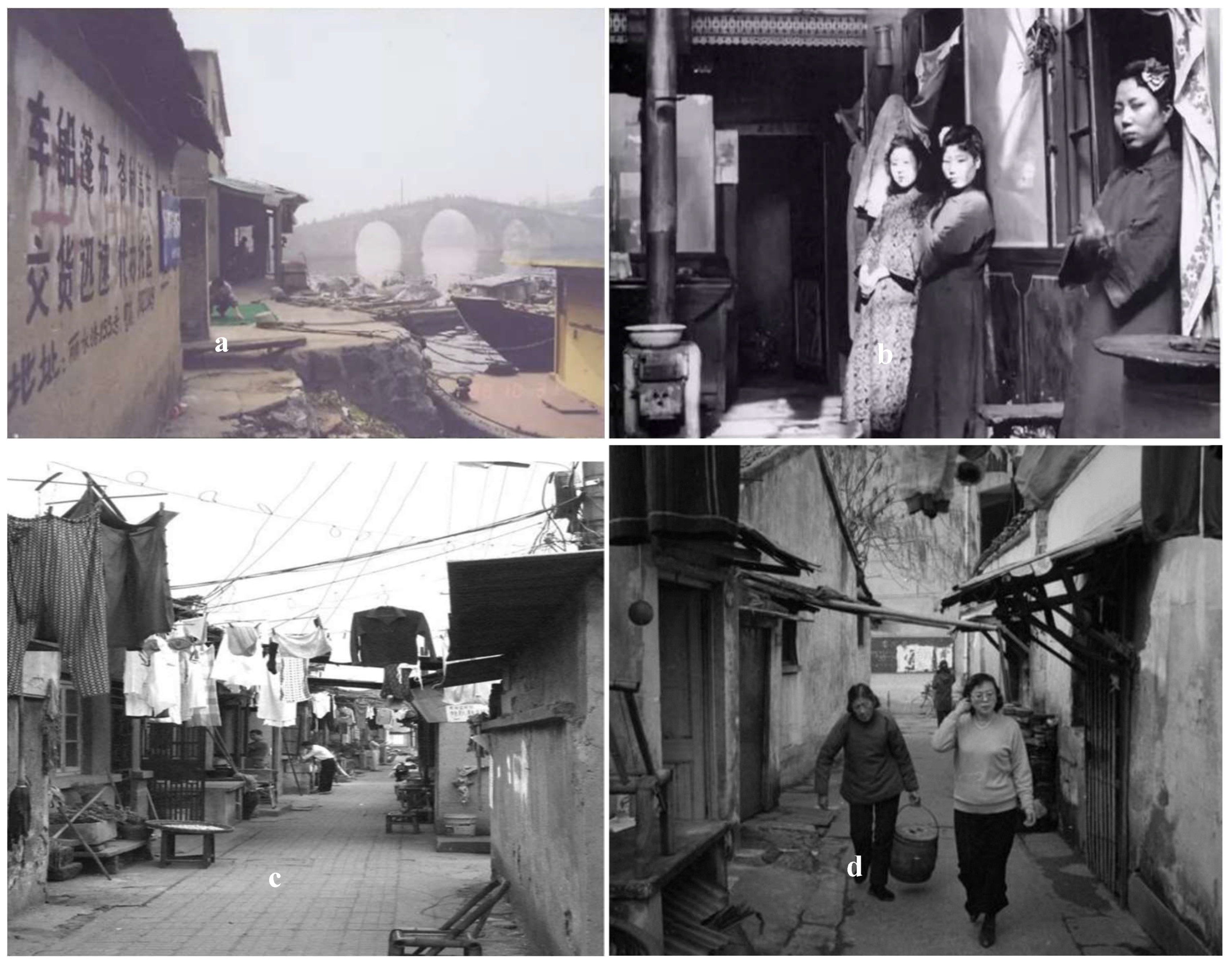

After 1990s, while restructuring of industries and the relocation of enterprises in Hangzhou, the old factory areas around Gongchen Bridge and along the Canal has gradually declined. Therefore, just like what happened in UK after 1950s, de-industrialization started to sweep through both sides of the Canal in Hangzhou, and the once thriving industrial areas promptly became shanty towns and slums. Detailly speaking, dilapidated shantytowns stretched out in patches, and sewage flowed in narrow alleys, which made the area characterized by mixed housing, poor infrastructure, and a serious lack of public space Additionally, the canal water at that time was dirty and smelly (see

Figure 8), and many laid-off workers and several generations of the family had to live in one cabin of less than ten square meters even without tap-water supply. For community, four or more families in the neighborhood had to share one public toilet, and the roads there were narrow and without any traffic lights (see

Figure 8). The regional service industry was mainly for the lower and middle classes, and even for a while there were folk prostitutes (see

Figure 8). Nowadays, when original residents from there recall the whole place, their deepest impression is “crowded” and “dirty”. Therefore, the place as “core and birthplace of Hangzhou’s industrialization” has gradually shifted into “Shanty Town”, especially the west side of Gongchen Bridge totally become a marginal, forgotten, and nasty place.

In December 1997, Hangzhou Municipal Government commenced the “Old City Renovation Project”, one of the ten flagship projects for civilians, around both sides of Gongchen Bridge and water quality improvement of the Grand Canal throughout more than 2.5 square kilometers, ten thousand households and 400 factories or organizations. One decade later, a more comprehensive and subtle conservation project was launched especially for the west side of Gongchen Bridge via the highlighting of ancient Chinese building style and historical sightseeing.

Entering 21st century, more than a quarter of China's resource-based cities experienced the serious problem of resource depletion. The State Council of China announced a total of 69 national resource-exhausted cities (counties and districts) in three batches on 17 March 2008, 5 March 2009 and 20 August 2013 respectively, which means that the total number of resource-exhausted cities accounted for nearly 11% of the total number of cities in China. Amongst those, a great deal of resource-based industries and factories were totally closed, and reconstructed or changed within the cultural mode like creative industries or cultural products afterward while “industrial heritage” has been used in the Chinese policy system. For China, 2006 witnessed a national industrial heritage movement with three major events: (1) on 18 April 2006, the First Forum on the Protection of Chinese Industrial Heritage issued Wuxi Advice, which was the first national official document aimed at the protection of Chinese industrial heritage: (2)in May 2006, the National Cultural Heritage Administration(NCHA) of China issued Notice on Strengthening the Protection of Industrial Heritage, which firstly launched a completed census on Chinese industrial heritages at the national level;(3) on 17 October 2006, 15th ICOMOS International Conference on Monuments and Sites was held in Chinese city of Xi'an and the theme of the International Day for Monuments and Sites was determined as “Industrial Heritage”. Therefore, Hangzhou Planning Bureau jointly with Hangzhou Urban Planning and Design Institute carried out a census of Hangzhou's industrial heritage, and one year later, Hangzhou issued and implemented Hangzhou Industrial Heritage (Architecture) Protection Plan and Hangzhou Industrial Heritage Architecture Planning and Management Regulations, based on which, Hangzhou Consensus-Protection and Utilisation of Industrial Heritage was released on 2012. Among them, industrial lands and heritages along the Canal have been regarded as the most important scope and contents.

The industrial heritages generated from the Grand Canal in China not only include a variety of historical and cultural elements, but also witness the cultural change and social transformation of cities and communities along the route. Up to July 2023, there are 32 Canal Industrial Heritages registered on five batches of Chinese National Industrial Heritage List (total amounted to 194) which has been selected and released via the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (MIIT) of PRC since 2017. Like the practices in UK, Germany etc., China also implemented urban regeneration via industrial heritage by developing cultural industries regarding old mills (Cizler,2012). And presently a series of national/provincial policies focused on “Industrial Heritages along Chines Grand Canal”: Zhejiang Provincial Regulations on Protection of the Grand Canal as World Cultural Heritage issued in 2021 proposed to encourage the display and promotion of Grand Canal heritage by relying on the former industrial sites; Zhejiang Provincial Action Plan for the Promotion of the Development of Industrial Culture issued in 2022 proposed to promote the protection and utilization of the industrial heritage along the Grand Canal; Measures for Administration of National Industrial Heritage issued in 2023 proposed to encourage the reuse of the selected heritages along the Canal. Especially with the construction of “Chinese Grand Canal National Cultural Park” after 2020, one of the most important cultural projects in China at present, several large-scale industrial sites and heritage such as Hangzhou Iron and Steel Plant have been deconstructed sheerly and quickly (see

Figure 9).

3.2. Assessing the Cultural Change of Industrial Lands along Hangzhou Section

3.2.1. Cultural Change Driven by World Heritage Purpose

Figure 10 presents the results of the ten industrial lands applying methodology 2.3.3. And it clearly demonstrates that though more than half of the cases performed decently in terms of the integrity and authenticity of the heritages from industrial lands, none of the cases preserve the core elements of them especially on the interpretation of production process and industrial technology, along in terms of the archives, museum, and digital technologies. Meanwhile, out of the strong pursuit of financial gain, almost all the cases have focused on investments in tourism and other cultural products. But besides profits, the purpose and fruits of UNESCO World Heritage also have played a rather cardinal role in the process of the profound cultural change.

Before and after being inscribed on World Heritage List in June 2014, Chinese Grand Canal has invested greatly in sustainable developments or adjustments of world-class cultural products not only along both sides of the Canal [

2], but also throughout the Canal’s cultural belt. Hangzhou, as one of the major node cities along the Canal and the principal economic city of China, has made great efforts in cultural development around the Canal area in the city [

7], even especially implementing a whole pack of Comprehensive Renovation and Protection & Development Project. Besides the evolution of the industry itself, the very application and purpose of UNESCO World Heritage also has become a quite cardinal driving force of the changes on industrial lands along the Canal in Hangzhou. In fact, the moment when Hangzhou, jointly with other Chinese Canal cities, decided to apply for the “world-class title”, Hangzhou section almost totally entered the “heritage era” and encountered new developmental opportunities, along with the comprehensively and profoundly cultural changes that happened throughout the whole area. In the Nomination file of Chinese Grand Canal as a world heritage

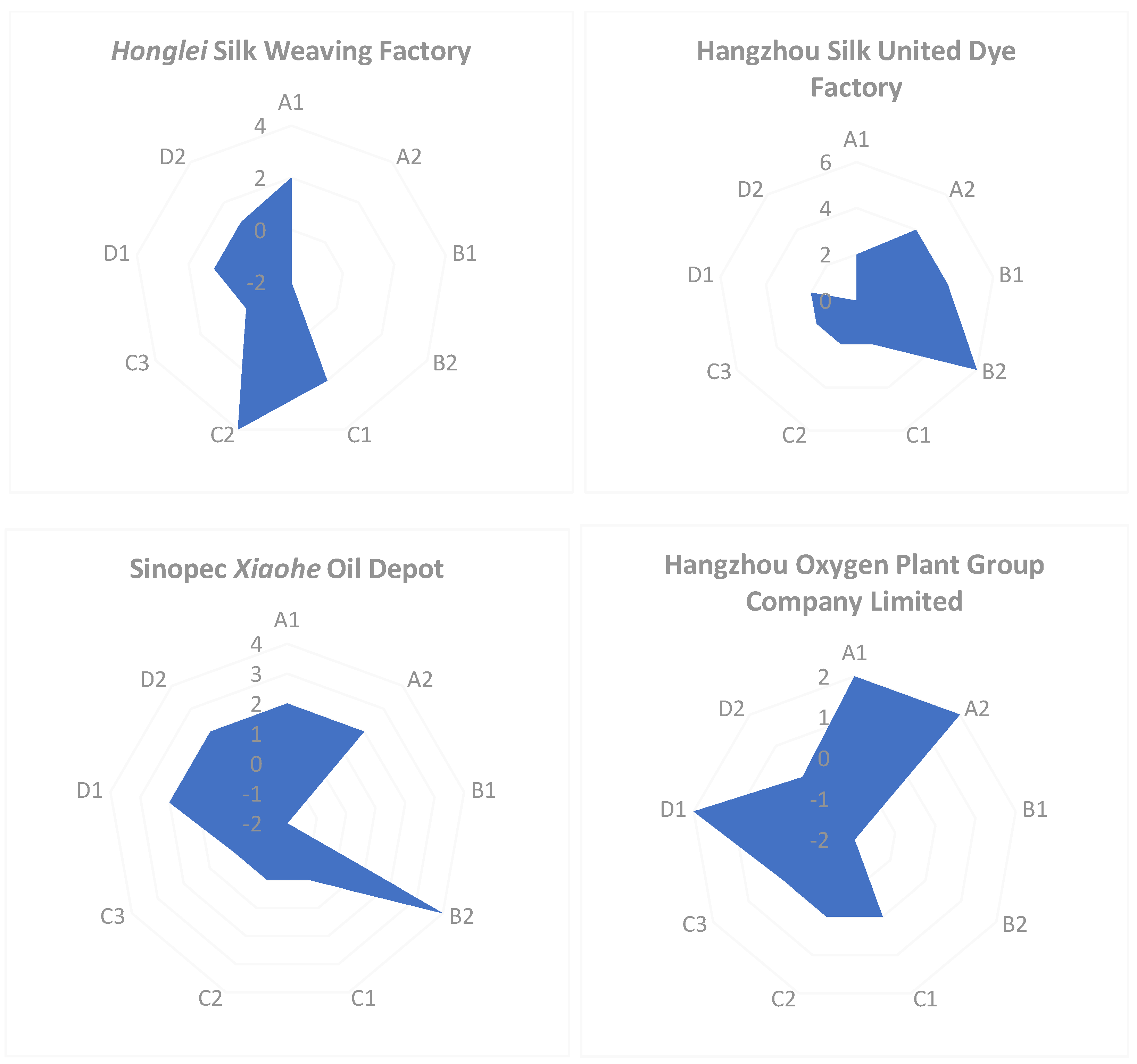

3, it simultaneously highlighted the protection and utilization of industrial heritages along the route. With the analysis of the software AntConc, except words or phrases like the grand canal/the canal/article/China/Chinese, “conservation”(749 times) and it with words such as heritage/site/environmental, area/zone/range, management/requirement/measure have been jointly used most frequently (see

Figure 11). Therefore, with the highlights of conservation on the atmosphere and environment of ancient China, after the Heritage Movement with Chinese Characteristics for nearly 20 years and since landscape, tourism and ecology became the main functions of canals in the postindustrial society, the whole place has totally been changed especially with the changes of industrial lands (see

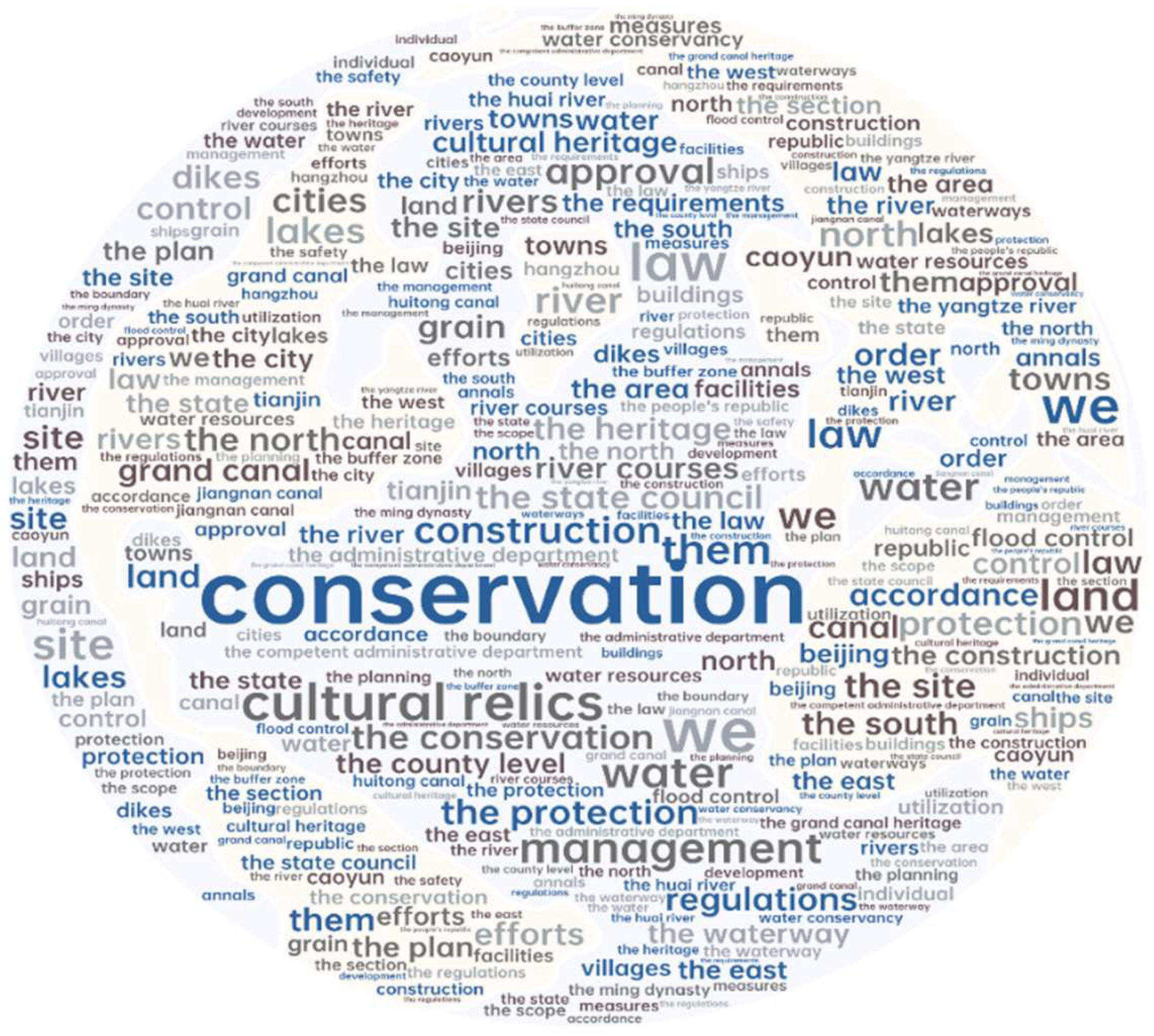

Figure 12).

Gongchen Bridge, one of the Chinese Major Historical and Cultural Sites Protected at National Level, not only stood for the final stop of Beijing-Hangzhou Grand Canal (one of the three parts of Chinese Grand Canal) during the past, but also represented half of Hangzhou’s history. From late Qing Dynasty to 1910s, Gongchen Bridge area developed into a settlement of shipping, individual industrialists and modern industrial workers, also an important commercial center in modern Hangzhou. Meanwhile the west side of Gongchen Bridge(“Qiaoxi” in Chinese) has become a light textile industrial zone which has been renovated as Qiaoxi Conservation Area, which not only was one of the eight world-heritage sites of Hangzhou section, but also was selected in Second Batch of National Tourism and Leisure Street issued by Ministry of Culture and Tourism of PRC. After Chinese industrialization, Gongchen Bridge connected modern lifestyles and industrial factories with traditional history and residential buildings, and became an important bridge for the formation of Hangzhou's modern industrial culture (see Figures 13). For making use of the title as world heritage, Qiaoxi has integrated residential, commercial, creative industries and cultural tourism, reflecting the modern design style, civilian residential culture, and warehousing and transportation features. Consequently, on the one hand, in terms of current provincial cultural policies and local cultural markets, the core and major cultural products mainly focus on the historic conservation area or complex the highlights on the history and style of Hangzhou as the capital of Chinese Southern Song Dynasty, while few elements relevant to the industrial past, spirits or contents. On the other hand, the few industrial heritage cultural products present a fragmented, dissemble or even fraudulent industrial past, especially considering the profound changes or even damages to the “authenticity” and “integrity” of those industrial heritages supported by the Canal.

Figure 13.

Gongchen Bridge and Its Adjacent Industrial Buildings in 1999 (source: Hangzhou Urban Construction Archives).

Figure 13.

Gongchen Bridge and Its Adjacent Industrial Buildings in 1999 (source: Hangzhou Urban Construction Archives).

3.2.2. TICCIH & Perspective of Industrial Heritage

For the purpose of UNESCO World Heritage, TICCIH (The International Committee for the Conservation of the Industrial Heritage) issued The International Canal Monuments List

4 on 1996, and evaluated Chinese Grand Canal as “one of the most influential waterways”, which offered an industrial heritage perspective for it to be inscribed as a world heritage site. Since Wuxi Proposal(2006) was issued in 2006, “industrial heritage” has gradually been constructed from a new subject in academic realm to a rather prominent public issue for the whole society of China. Similar to countries like UK which entered deindustrialization, plenty of industrial lands in Chinese major cities like Hangzhou along the Canal were discarded, eradicated or kept derelict since the rapid technological developments and changes in industrial production systems [

9].And since “regeneration via industrial heritage"[

10] has been implemented successfully beyond UK and Europe, industrial heritage has become a sustainable approach and important geographical component that restores the cultural, social and economic value of old industrial landscapes[

11,

12,

13]. But as the industrial heritage is characterized by a complicated system, large-scale, wide land area, bulky volume and too heavy to easily move, the cultural development also suffers from insufficient demand side, conflicting stakeholders, reuse issues, lack of economic benefits, authenticity issues and lack of community awareness [

15]. For instance, Xiaohe Park in Hangzhou, which used to be Sinopec Xiaohe Oil Depot-- the first oil depot of Zhejiang Province founded in 1950, opened to the public in September 2022 and has been built as an influential canal tourism spot characterized by oil tanks, plants, workshop and green belt along the Canal (Figure 13). Though tourists and media are often prominently attracted, Xiaohe Park has been criticized via professional sections mainly due to the destruction of its authenticity and integrity, as well as the detraction of genius loci, especially judged from high-resolution satellite imagery (HRSI) at different historical sections (see

Figure 14). Therefore, though industrialization on the industrial lands have totally disappeared in history, the perspective of industrial heritage and local industrial culture should not totally be erased and neglected.

Figure 13.

Xiaohe Park Daytime View (source: author).

Figure 13.

Xiaohe Park Daytime View (source: author).

4. Discussion

Industrial lands have witnessed, participated and experienced the very process of demolishment, eradication or forsakenness after the widespread industrial recession of China after the entering of 21st century, and the combination with cultural industries has become the major characteristic of the cultural change. As the southernmost point of Chinese Grand Canal, Hangzhou’s development has mainly relied on the Canal with its main business formats of rice shops, wooden shops, local specialty shops, bamboo charcoal for a quite long time, and the majority of residents including merchants, small homeowners, pier porters, canal trackers and other urban civilians from middle and lower class. After that, Hangzhou section experienced the industrialization, modernization, and urbanization of the whole city at different historical times, and then partially developed cultural products mainly via its great deal of industrial lands and industrial heritages after large-scale social change.

4.1. Make of Ancient

After the rather rapid heritage movement with Chinese style and active demands on the development of cultural & creative industries, especially the national purpose of being successfully inscribed on UNESCO World Heritage List, diversified cultural practices have been implemented on the industrial lands along Hangzhou section. Though this kind of cultural change happened quite normally when plenty of Chinese cities successively entered post-industrialization society, except Zhejiang Hemp Textile Factory was almost demolished to create a modern residential neighborhood, the replacement of industrial past and lands with deliberately artificial ancient-style street or complex after mass demolition in the city like Hangzhou is still comparatively infrequent, which could be defined as “make of ancient”. In general, it could be observed and accessed via three types. The very first was to “Conceal” the industrial past of the industrial lands, and to deliberately hide the industrial elements especially on the external façade of the factories, plants or auxiliary buildings. As Hangzhou No.1 Cotton Spinning Factory, Tongyi Government-runYarn Factory and Honglei Silk Weaving Factory were successively been reconstructed or changed into cultural museums, a civilian-oriented thematic museum group, with the interpretation and presentation of Chinese historical traditional handicrafts like an oil-paper umbrella and green tea. Second type was the “Transformation” of original industrial lands to creative industry platforms or clusters. Such as Dahe Shipyard(see

Figure 15) and Hangzhou Oxygen Plant Group Company Limited were respectively transformed into “Canal World” and “Wulinzhixing Expo Center” -- two comprehensive cultural and commercial parks with cinema or restaurants changed from workshops and plants; Hangzhou Silk United Dye Factory, one of the major program of Chinese First Five-year Plan, was totally transformed as a creative industrial park with café, clothing shop and photography studio. The last type was the “Emphasize” of the industrial past. Like Sinopec Xiaohe Oil Depot, Hangzhou Iron and Steel Plant and Hangzhou Oil Refinery jointly stressed their industrial history and context, and shed light upon the intrinsically production flow even with a digital approach. Presently, they successively were rebuilt into public canal industrial parks or art centers. But what needs to be stressed is that the industrial public cultural practice like Xiaohe park was still actually embedded into the landscape of the “artificial ancient” (see

Figure 16).

4.2. Loss & Justified Reasons

After widespread industrial recession, Chinese cultural tourism industry derived from industrial heritage commenced in the early 2000s and has boosted and propelled local creative economy and nostalgia industry prominently. While at present stage, from the analysis above, relevant cultural products either derogated the authenticity and integrity of local industrial history, or discarded its industrial spirit, even largely obliterating the industrial history of the whole city. And almost none of the cultural products completely preserved the intact industrial heritage sites such as the whole factory complex, the produce line or workers’ community since those traditional industrial cities have been eager to get involved with the global competition rather than reflecting and protecting past industrial culture [

16], though what makes industrial heritage important is it preserves the trace of technological progress, landscape evolution and changes via humans upon surface of the earth [

14]. What’s worse, relevant cultural products either derogated the authenticity and integrity of local industrial history, or discarded its industrial spirit, even largely obliterated the industrial history of the whole city.

In Hangzhou, after the rapid process of economic development and deindustrialization, all the industries deployed along the Canal have been 777, and the survival ones were constructed as cultural resources and shaped as cultural attractions characterized with ancient Chinese style rather than industrial past. Furthermore, nowadays, more than 60% of creative industries complex or zone in Hangzhou were transformed via industrial heritages, but few of them have improved public awareness of how Hangzhou has been shaped by its canal industrial history, or offered the completed core products of the novel cultural experience of industrial heritage tourism (Goodall,1993), which has caused great cultural losses. Therefore, these fragmented, irrelevant, discarded, and ostensible reuses of industrial heritages have surely produced fraudulent information and cultural damages, presenting the typical complicated relationship between heritage values and the urban cultural development (Barrado-Timón,2019). And the justified reasons could be safely concluded as follows:

- (1)

To stress the long ages of the Canal and its cultural heritages. As Chinese Grand Canal has been flowing for thousands of years, creating an ancient environment along the route of Hangzhou, the capital of the Southern Song dynasty (1127-1279), could be quite helpful for the long age of cultural heritage, as well as the whole city. In fact, it even deliberately safeguarded the ancient style and elements, such as the local government building another modern steel bridge for motorcars or electro-mobiles to protect Guangji Bridge (see

Figure 17).

- (2)

To avoid showing the recession facts on the industrial lands. “Dirty, smelly and nasty” are the key words of industrial recession throughout the world. After 2000s, considering the rapid economic boom and urbanization of China, the dilapidated and rusty factories surely could be easily eradicated to quickly cover the recession facts, and to integrate modern acoustic and optoelectronic technology with ancient buildings(see

Figure 18) instead of.

- (3)

To promote economic development and land prices. Within the process and purpose of World Heritage, Hangzhou has invested significant resources in the area along the Grand Canal, and industrial lands in the area naturally should be totally getting rid of, and a premium water-friendly platform offered by the canal could promptly promote local economic development and raise the price level of commercial properties around the place (see

Figure 19).

4.3. Canal-based Tourism Products via Industrial Lands

Globally speaking, most of the canals have gone through the heritage movement in the post-industrial and anti-industrial eras and to develop canal-based tourism products on the former industrial lands: such as Belgium Antwerp canal system renovated its old warehouses into luxury hotels and transformed the shipping dock into a sightseeing dock; smelled in the 1970s, Japan Otaru canal removed sludge from the river bottom and improvement of water quality to regenerate the historic view of the canal; located at the confluence of the Ruhr and the Rhine, Duisburg of Germany replaced its coal and the steel industries to sustainable tourism model. Hangzhou, as one of the Chinese nationally renowned tourist and landmark cities along the Grand Canal, has given high priority to tourism development, for instance, Hangzhou Municipal Government specially established Hangzhou Canal Comprehensive Protection, Development and Construction Group Co. on 2003 designed three water bus sightseeing special flagship lines on 2005. At present, the tourism products along Hangzhou’s Canal can be divided into three categories: water sightseeing (such as a waterborne bus), historical blocks & towns (such as Qiaoxi Conservation Area), and cultural industries (such as LOFT49 Creative City Pioneer Zone). While successfully gaining significant economic benefits and reputation, it simultaneously has driven profound cultural change and loss, especially in terms of former industrial lands and industrial heritages along the route, especially the integrity and authenticity of them. Additionally, since tourism is the leading industry in the digital transformation of cultural heritage management [

5,

6,

7], the digital contents and products for current Canal culture development (Hangzhou section) should be replenished and developed.

4.4. Suggestion of Digitalization

The mentioned loss and deficiency of industrial elements and context could somehow be changed via digital technologies. Nowadays, digital reuse and access to heritage have become more than a global academic consensus. In the early 21st century, “digital” has been introduced as tools or supplements to the development of cultural heritage, with the purpose of landscape [

21], edutainment [

22], museum [

23,

24] and design (Grubgeld,2006; Bianchi,2006). After that, “digital” have been widely used in planning and reuse of heritages, and “digital” improvements and innovations were organized as toolkits or systems, such as a virtual exhibition system called MNEME (from the Ancient Greek ‘memory’) [

25]; a digital solution expresses the genius loci of architectural heritage employing digital visualization [

28], etc. While the digital reality of heritage become a reliable surrogate and permanent digital protection has been justified [

31], digitalization of, especially a virtual reality and augmented reality(such as virtual tour of Newcastle Merewether coal), cultural heritage has proceeded variously for conservation and cultural development. Internationally speaking, research and practice on cultural heritage have experienced a comprehensively digital movement for nearly 30 years, and China has strongly promoted the integration of culture and technology for more than two decades especially with the elevation of Digitization of Culture as a Chinese national strategy on March 2021, during which a comparatively novel cultural reality has been constructed, and a new context of cultural identity and been formed. “Intangibility” as the essence of cultural heritage (Smith, 2012) has justified a “staging authenticity”[

19] created by digital technology on information collection, smart heritage, immersive experience, online tourism, digital cultural creation and public engagement towards available heritages. The digitization of industrial heritage refers to the conversion of relevant information of industrial heritage into digital form, encoding and introducing it into computers for storage, calculation, analysis, model construction, and display. It has the advantages of reversibility, intuitiveness, innovation, and non-distortion. Emphasizing the application of digital technology in the protection and updating of industrial heritage can maximize the preservation of the authenticity of industrial heritage and reduce the loss of original information. Obviously, digitalization could break the geographical and temporal connections established by heritage elements [

17], during the process of realization of basic values to advanced values [

20].

Hangzhou, where three world heritages have been inscribed and digital transformation, as well as the internet technology development, of the whole city has been greatly promoted for more than 10 years, witnessed the very first application of GIS embedded with industrial heritage in China with the construction of Hangzhou Industrial Heritage Database. Therefore, restoration, construction and promotion in the digital world are quite needed. Additionally, as early as was officially issued, Article 23 stated that it is encouraged and Article 26 proposes to encourage the integration of the use of the Grand Canal heritage with science and technology, develop related special cultural products and services, and promote the digital application of the Grand Canal heritage

5. On 18th April 2022, Zhejiang Provincial Department of Economy and Information Technology and other 9 provincial departments jointly released Zhejiang Provincial Action Plan for Promoting Development of Industrial Culture highlighting the promotion of industrial heritages along the Grand Canal, as well as the use of modern information technologies to create a group of digital, visual, and intelligent new industrial museums for enhancing visitors’ sense of experience, participation, and interaction

6. Less than one year later, MIIT issued the Administration of National Industrial Heritage with emphasizes on systematic participation and digital management in the preservation and utilization of national industrial heritages along Chinese Grand Canal. Therefore, considering the irreversible damage to industrial buildings, elements, and components, the development of digitalized products for the tourism, mainly focusing on the integration of physical and virtual world, is more required than before. Concerning its approach, through the rapid development of cultural digitalization in China, the panorama view, point clouds and others have been collaboratively used and interpreted mainly over the relevant cases of Xiaohe Park, Silk United 166, Hangzhou Iron and Steel Group Industrial Heritage Park (see

Figure 20,

Figure 21 and

Figure 22).

5. Conclusions

A typical, widespread, and far-reaching cultural change over industrial lands happened along Hangzhou section after the industrial recession at a comparatively high rate, which offered an interpretation and perspective for what has happened throughout major cities in China after the 2000s. From the research, it could be safely concluded that as the main function of the Grand Canal shifted from an industrial transport platform to a cultural tourism setting, and with the visible results of the Chinese government's ecological management towards the Grand Canal, the Hangzhou section of the Grand Canal was transformed from an industrial zone and shanty town to an important economic center and recreational area in the city, and in this process large numbers of industrial lands were dissipated into history. In addition to the more common practice of transforming industrial heritages into modern museums, cultural & creative industrial parks and commercial complexes, Hangzhou has also deliberately changed the industrial lands ,which was the evidence of industrialization and urbanization after the founded of PRC, to an artificial appearance of “ancient China”, which was not only an established policy before and after the Grand Canal inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List, but also, to a certain extent, an attempt to cater to the stereotype of "ancient China" in the world context. Although the presentation and dissemination of industrial culture has resulted in a cultural loss, it has also been more successful in enhancing economic and social benefits and the image of the region.

Funding

The research was sponsored by the Zhejiang Provincial Social Science Fund(23YJZX13YB); Hangzhou Municipal Social Science(Z23JC067).

References

- Anonymous. The Grand Canal, Cradle of Ancient Chinese Civilization. China Today 2014, 63, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Camilleri, M.A. ; Routledge Handbook of Tourism Cities. Emerald Publishing Limited 2022, 8, 1185–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Jingdong, and Jing Peng. Introduction of the Beijing–Hangzhou Grand Canal and analysis of its heritage values. Water Projects and Technologies in Asia. CRC Press, 2023, 75-86.

- Bin, X.; Xiang, L.; Le, Y.; Liang, S.; Dengrong, Z. An Analysis of the Change of the Beijing-Hangzhou Grand Canal (Hangzhou Section) and Its Impact on the Industrial Pattern. Journal of Remote Sensing for Land & Rescources 2010, 85, 76–77. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Xiumei, et al. Tourism industry is leading the digital transformation of cultural heritage management: Bibliometric analysis based on web of science database. 2020 Management Science Informatization and Economic Innovation Development Conference (MSIEID) 2020, IEEE.

- Cizler, Jasna. Urban regeneration effects on industrial heritage and local community–Case study: Leeds, UK. Sociology and space-Sociologija i proctor 2012, 50, 193. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, Y.H.D. Restructuring for growth in urban China: Transitional institutions, urban development, and spatial transformation. Habitat international 2012, 36, 396–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodall, B. Industrial heritage and tourism. Built environment 1993, 19, 93. [Google Scholar]

- YILDIZ, G.; GUCHAN, N.S. An Industrial Heritage Case Study in Ayvalik: Ertem Olive Oil Factory. Journal of Contemporary Urban Affairs 2018, 2, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hospers, G.J. Industrial heritage tourism and regional restructuring in the European Union. European Planning Studies 2002, 10, 397–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonsen-Verbeke, M. Industrial heritage: A nexus for sustainable tourism development. Tourism Geographies 1999, 1, 70–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prat Forga, J.M.; Canoves Valiente, G. Cultural change and industrial heritage tourism: Material heritage of the industries of food and beverage in Catalonia (Spain). Journal of Tourism and Cultural Change 2017, 15, 265–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkenbosch, K.; Groote, P.; Stoffelen, A. Industrial heritage in tourism marketing: Legitimizing post-industrial development strategies of the Ruhr Region, Germany. Journal of Heritage Tourism 2022, 17, 327–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrigley, E.A. Energy and the English industrial revolution. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences 2013, 371, 20110568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, P.F. Developing industrial heritage tourism: A case study of the proposed jeep museum in Toledo, Ohio. Tourism management 2006, 27, 1321–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.S. Industrial heritage tourism development and city image reconstruction in Chinese traditional industrial cities: a web content analysis. In Heritage Tourism and Cities in China 2019,49-62. Routledge.

- Barrado-Timón, D.A.; Hidalgo-Giralt, C. The historic city, its transmission and perception via augmented reality and virtual reality and the use of the past as a resource for the present: a new era for urban cultural heritage and tourism? Sustainability 2019, 11, 2835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, L. All heritage is intangible: critical heritage studies and museums. Amsterdam: Reinwardt Academy 2012, 48.

- Fu, Y.; Kim, S.; Zhou, T. Staging the ‘authenticity’of intangible heritage from the production perspective: the case of craftsmanship museum cluster in Hangzhou, China. Journal of Tourism and Cultural Change 2015, 13, 285–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, Z.; Ouyang, T.; Xu, J. Research on the Sustainable Development of Enterprises That Evoke Industrial Heritage—A Case Study of Taoxichuan. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addison, A.C.; Strickland, R.M.; Ceccarelli, N. Communicating culture and exploring landscape: an experiment in digital heritage in the Loire valley. In Proceedings Seventh International Conference on Virtual Systems and Multimedia 2001, 3-12. IEEE.

- Song, M.; Elias, T.; Martinovic, I.; Mueller-Wittig, W.; Chan, T.K. Digital heritage application as an edutainment tool. In Proceedings of the 2004 ACM SIGGRAPH international conference on Virtual Reality continuum and its applications in industry 2004, 163–167. [Google Scholar]

- Parry, R. Recoding the museum: Digital heritage and the technologies of change 2007. Routledge.

- Smith, B. Digital heritage and cultural content in Europe. Museum International 2002, 54, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruno, F.; Bruno, S.; De Sensi, G.; Luchi, M.L.; Mancuso, S.; Muzzupappa, M. From 3D reconstruction to virtual reality: A complete methodology for digital archaeological exhibition. Journal of Cultural Heritage 2010, 11, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grubgeld, E. Castleleslie. com: Autobiography, Heritage Tourism, and Digital Design. New Hibernia Review/Iris Éireannach Nua 2006, 10, 46–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, C. Making online monuments more accessible through interface design. Digital heritage—applying digital imaging to cultural heritage 2006. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann, 445-66.

- Kepczynska-Walczak, A.; Walczak, B.M. Visualising genius loci of built heritage. In Proceedings of the 11th Conference of the European Architectural Envisioning Association 2013, Envisioning Architecture: Design, Evaluation, Communication, Milano, Italy (pp. 23-28).

- Lin HY, Cooke SJ, Wolter C, Young N, Bennett JR. On the conservation value of historic canals for aquatic ecosystems. Biological Conservation 2020, 251, 108764. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Zhang, H.; Sun, Z. Spatiotemporal variations of land urbanization and socioeconomic benefits in a typical sample zone: A case study of the Beijing-Hangzhou Grand Canal. Applied Geography 2020, 117, 102187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudge, M.; Ashley, M.; Schroer, C. A digital future for cultural heritage. In AntiCIPAting the Future of the Cultural Past, Proceedings of the XXI International CIPA Symposium 2007, 1-6.

- Landorf, C. A framework for sustainable heritage management: A study of UK industrial heritage sites. International Journal of Heritage Studies 2009, 15, 494–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neill, Robin. Canal era industrialization: Canada, 1791-1840. In Atlantic Provinces Economic Association Conference 2003 Working Paper Series 2003, vol. 2003.

- Hain, V.; Ganobjak, M. Forgotten industrial heritage in virtual reality—Case study: Old Power Plant in Piešt’any, Slovakia. Presence: Teleoperators and Virtual Environments 2017, 26, 355–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaner, J. Image management systems: a model for archiving Stoke-on-Trent's post-industrial heritage 2017, 56-59.

- Perfetto, M.C.; Vargas-Sánchez, A. Towards a Smart Tourism Business Ecosystem based on Industrial Heritage: research perspectives from the mining region of Rio Tinto, Spain. Journal of Heritage Tourism 2018, 13, 528–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echavarria, K.R.; Weyrich, T.; Brownsword, N. Preserving ceramic industrial heritage through digital technologies. In Eurographics Workshop on Graphics and Cultural Heritage, The Eurographics Association 2019.

- Herman, K. The impact of technology on the industrial heritage tourism enterprises: case of the coal mine museum in Zabrze. Zeszyty Naukowe. Organizacja i Zarządzanie/Politechnika Śląska 2020, 146, 143–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrioti, N.; Kanetaki, E.; Drinia, H.; Kanetaki, Z.; Stefanis, A. Identifying the industrial cultural heritage of Athens, Greece, through digital applications. Heritage 2021, 4, 3113–3125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardo Abad, C.J. Application of digital techniques in industrial heritage areas and building efficient management models: Some case studies in Spain. Applied sciences 2019, 9, 4420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Zhu. World Heritage Site inscription and waterfront heritage conservation: evidence from the Grand Canal historic districts in Hangzhou, China. Journal of Heritage Tourism 2021, 16, 684–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowley, I. Monson’s Internet canal. Institutional Investor-International Edition 1999, 24, 22. [Google Scholar]

- State Administration of Cultural Heritage. Wuxi Proposal – Focus on Industrial Heritage Protection in the Period of Rapid Economic Development. Architectural Design 2006, 8, 195–196. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Shuying, Jiaming Liu, Tao Pei, Chung-Shing Chan, Caixia Gao, and Bin Meng. Perception in cultural heritage tourism: an analysis of tourists to the Beijing-Hangzhou Grand Canal, China. Journal of Tourism and Cultural Change 2023,1-23.

- Yan, H. The making of the Grand Canal in China: Beyond knowledge and power. International Journal of Heritage Studies 2021, 27, 584–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

The location of Selected 10 Industrial Heritages along Hangzhou Section (source:author).

Figure 1.

The location of Selected 10 Industrial Heritages along Hangzhou Section (source:author).

Figure 2.

The Flowchart of this Research (source:author).

Figure 2.

The Flowchart of this Research (source:author).

Figure 3.

Land Use Changes (LUC) of Selected Ten Industrial Lands (source:author).

Figure 3.

Land Use Changes (LUC) of Selected Ten Industrial Lands (source:author).

Figure 4.

Area of Different New Uses of 10 Industrial Lands in 2022 via Applying Methodology (unit: m2).

Figure 4.

Area of Different New Uses of 10 Industrial Lands in 2022 via Applying Methodology (unit: m2).

Figure 5.

Share of Hangzhou’s Industrial Categories after the 1950s (source:author).

Figure 5.

Share of Hangzhou’s Industrial Categories after the 1950s (source:author).

Figure 6.

Zhejiang Jute Textile Factory--the largest jute spinning and weaving factory and basement in Asia at that time (source: Hangzhou Urban Construction Archive.

Figure 6.

Zhejiang Jute Textile Factory--the largest jute spinning and weaving factory and basement in Asia at that time (source: Hangzhou Urban Construction Archive.

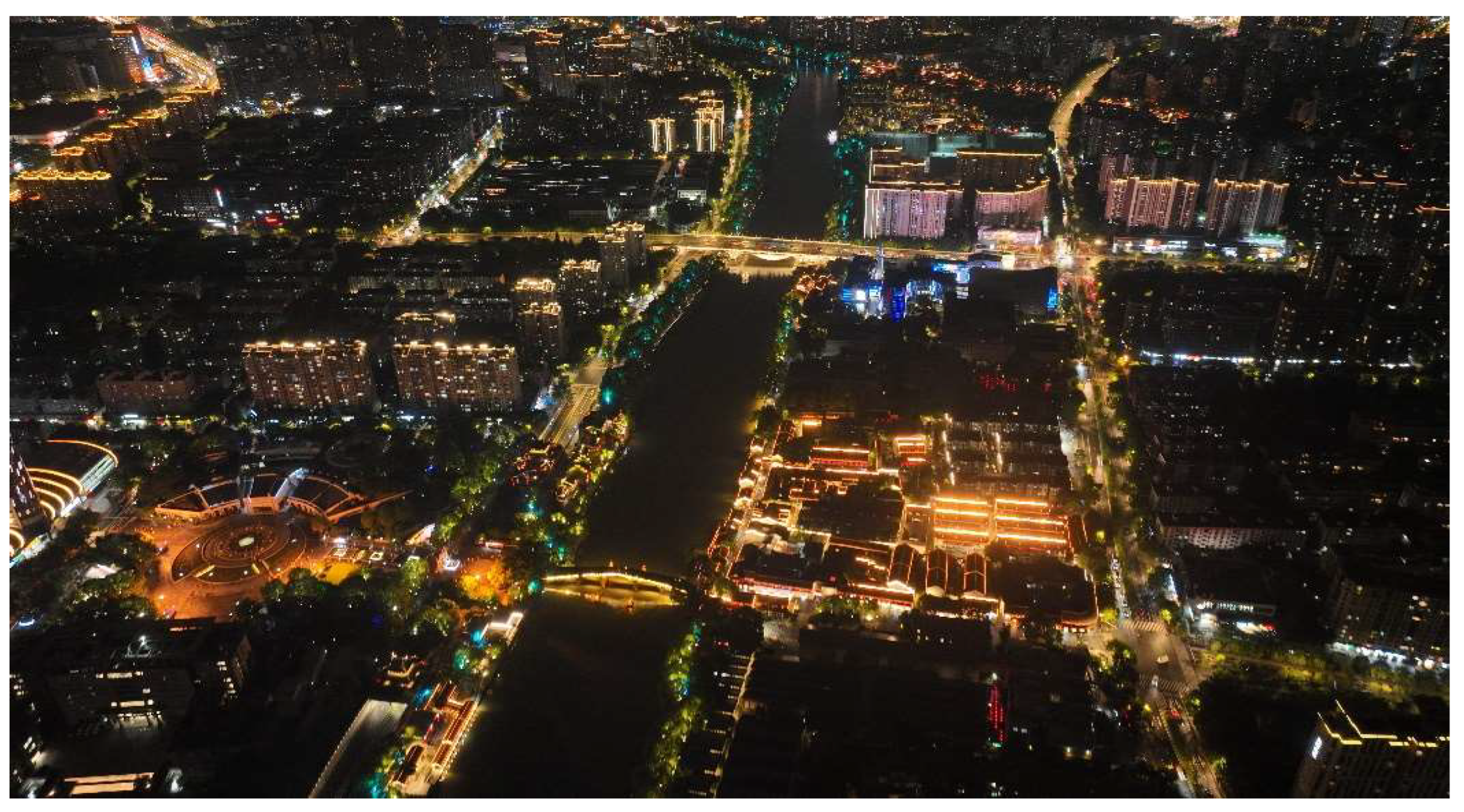

Figure 7.

Daytime/Night View of Gongchen Bridge and Qiaoxi Conservation Area (source: author).

Figure 7.

Daytime/Night View of Gongchen Bridge and Qiaoxi Conservation Area (source: author).

Figure 8.

a: Awful Environment besides the Gongchen Bridge and the Canal after Industrial Recession/ b: Prostitutes for Lower-middle Classes Lived along Hangzhou Section (source: Hangzhou Urban Construction Archives)/ c&d:Typical Shantytown along Hangzhou Section after Industrial Recession.

Figure 8.

a: Awful Environment besides the Gongchen Bridge and the Canal after Industrial Recession/ b: Prostitutes for Lower-middle Classes Lived along Hangzhou Section (source: Hangzhou Urban Construction Archives)/ c&d:Typical Shantytown along Hangzhou Section after Industrial Recession.

Figure 9.

two satellite photos of Hangzhou Iron and Steel Plant in June 2000/2023.

Figure 9.

two satellite photos of Hangzhou Iron and Steel Plant in June 2000/2023.

Figure 10.

Results of Applying the Methodology.

Figure 10.

Results of Applying the Methodology.

Figure 11.

Word Cloud Image of UNESCO Chinese Grand Canal Nomination File (source: author).

Figure 11.

Word Cloud Image of UNESCO Chinese Grand Canal Nomination File (source: author).

Figure 12.

Daytime View of Gongshu Districts, Hangzhou section in 2003 & 2023(source: author).

Figure 12.

Daytime View of Gongshu Districts, Hangzhou section in 2003 & 2023(source: author).

Figure 14.

HRSI of Sinopec Xiaohe Oil Depot on July 2000/2021/2023 (source: author).

Figure 14.

HRSI of Sinopec Xiaohe Oil Depot on July 2000/2021/2023 (source: author).

Figure 15.

Daytime/Night Views of Former Dahe Shipyard (source: author).

Figure 15.

Daytime/Night Views of Former Dahe Shipyard (source: author).

Figure 16.

Xiaohe Park Surrounded with the “Make of Ancient” Style (source: author).

Figure 16.

Xiaohe Park Surrounded with the “Make of Ancient” Style (source: author).

Figure 17.

Gangji Bridge in the Tangxi Town Located at Linping District (source: author).

Figure 17.

Gangji Bridge in the Tangxi Town Located at Linping District (source: author).

Figure 18.

Gongchen Bridge Attracted a Mass of Visitors even during the nights (source: author).

Figure 18.

Gongchen Bridge Attracted a Mass of Visitors even during the nights (source: author).

Figure 19.

Bustling Night Scene along Hangzhou section in 2023 (source: author).

Figure 19.

Bustling Night Scene along Hangzhou section in 2023 (source: author).

Figure 20.

One Section of Panorama View of Xiaohe Park (source: author).

Figure 20.

One Section of Panorama View of Xiaohe Park (source: author).

Figure 21.

One Section of Panorama Views of Silk United 166 (source: author).

Figure 21.

One Section of Panorama Views of Silk United 166 (source: author).

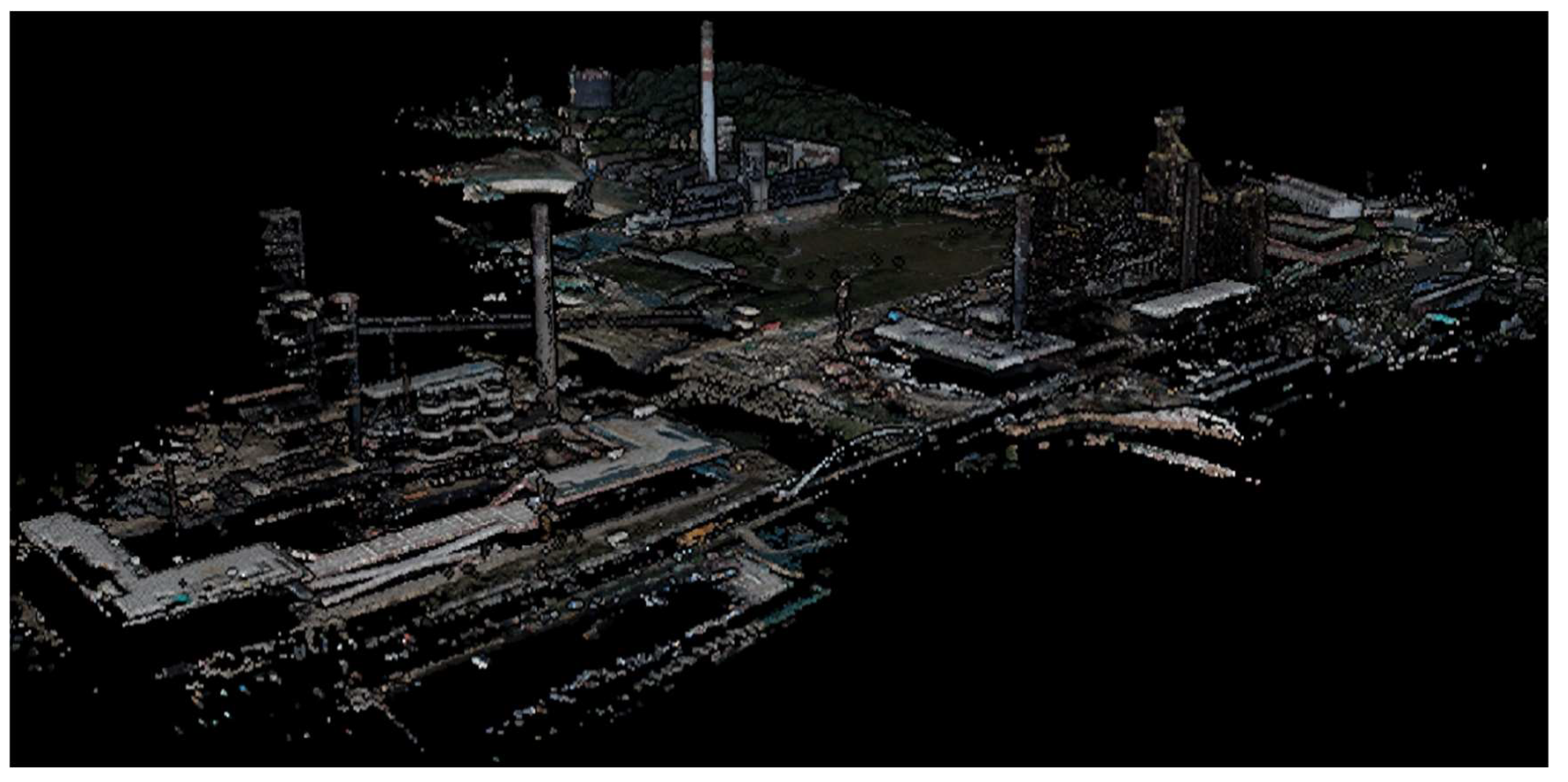

Figure 22.

One Section of Point Clouds View of Hangzhou Iron and Steel Group Industrial Heritage Park (source: author).

Figure 22.

One Section of Point Clouds View of Hangzhou Iron and Steel Group Industrial Heritage Park (source: author).

Table 1.

Description of Factors and Scores in Four Aspects (source: own compilation).

Table 1.

Description of Factors and Scores in Four Aspects (source: own compilation).

Table 2.

Status Quo of Industrial Heritages along Grand Canal (Hangzhou section) (source: author).

Table 2.

Status Quo of Industrial Heritages along Grand Canal (Hangzhou section) (source: author).

Table 2.

Major Industrial Enterprises along the Hangzhou section (source: author).

Table 2.

Major Industrial Enterprises along the Hangzhou section (source: author).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).