Submitted:

06 May 2024

Posted:

08 May 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

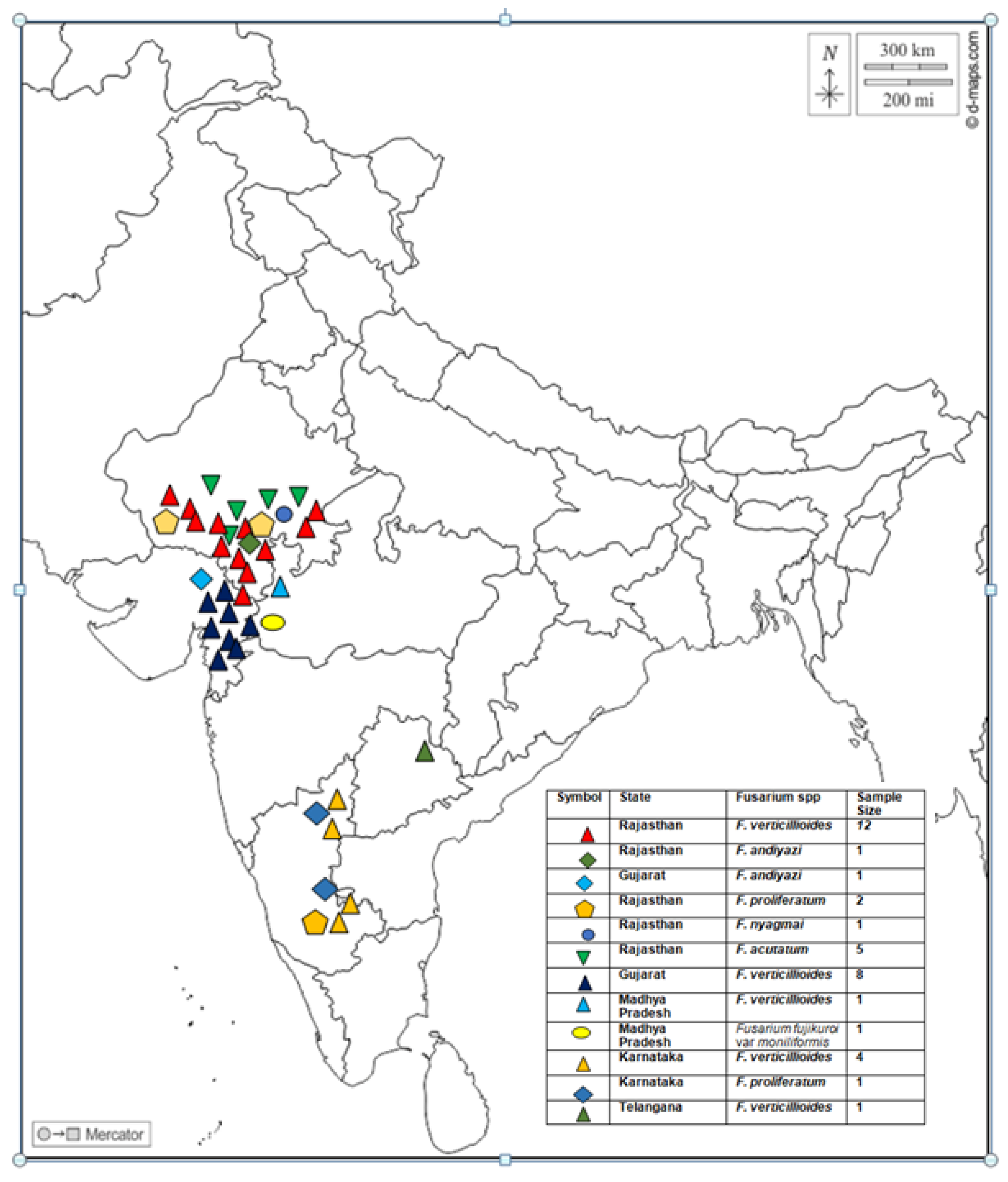

2.1. Study Area and Fungal Isolates Sampling

2.2. Fungal Isolation

2.3. DNA Isolation, PCR Amplification and Sequencing

2.4. Phylogenetic Analysis

2.5. Population Genetic Analysis

2.6. Indices of Genetic Diversity and Fusarium Population Structure

2.7. Haplotype Network Analysis

3. Results

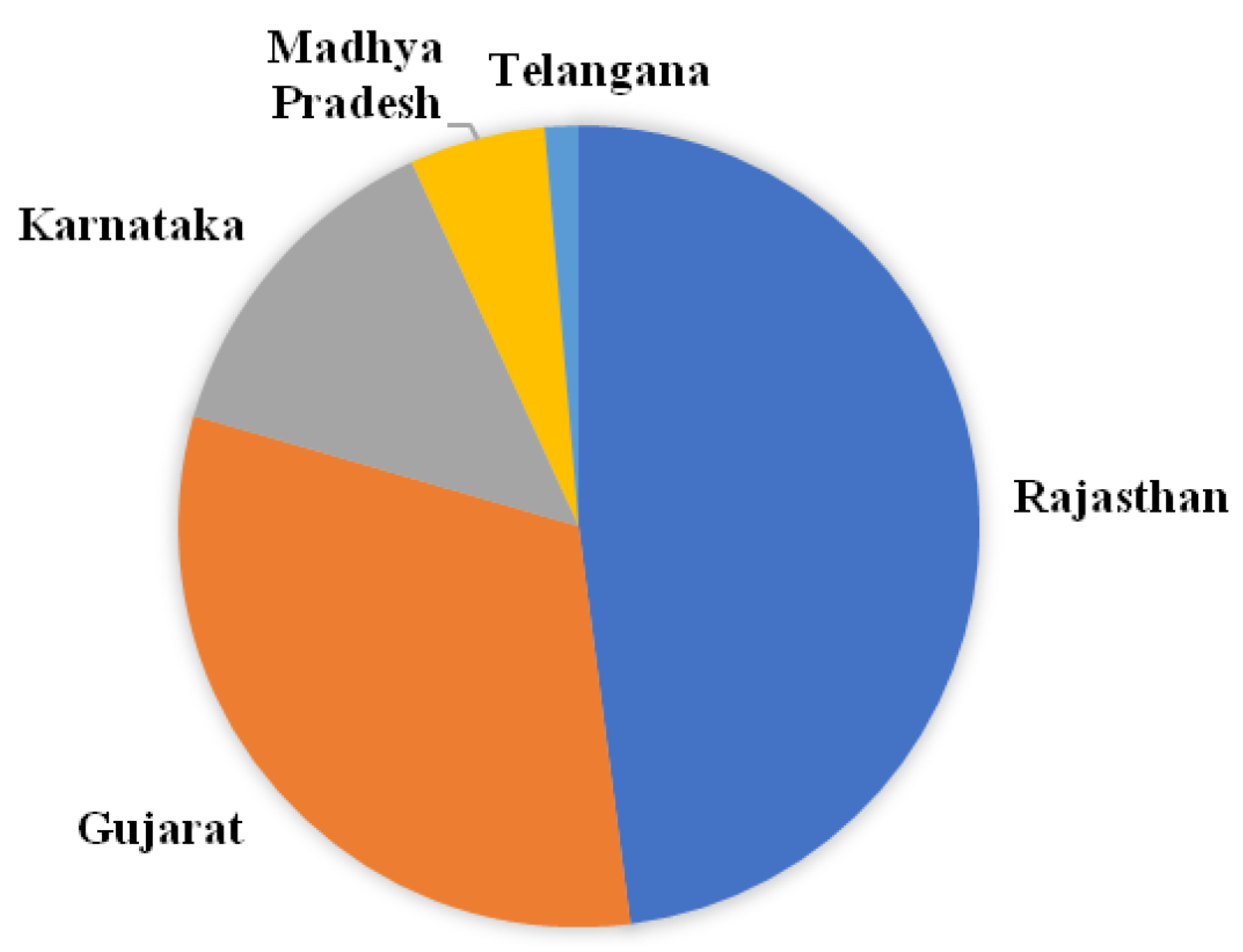

3.1. Collection of Isolates

3.2. Molecular Identification

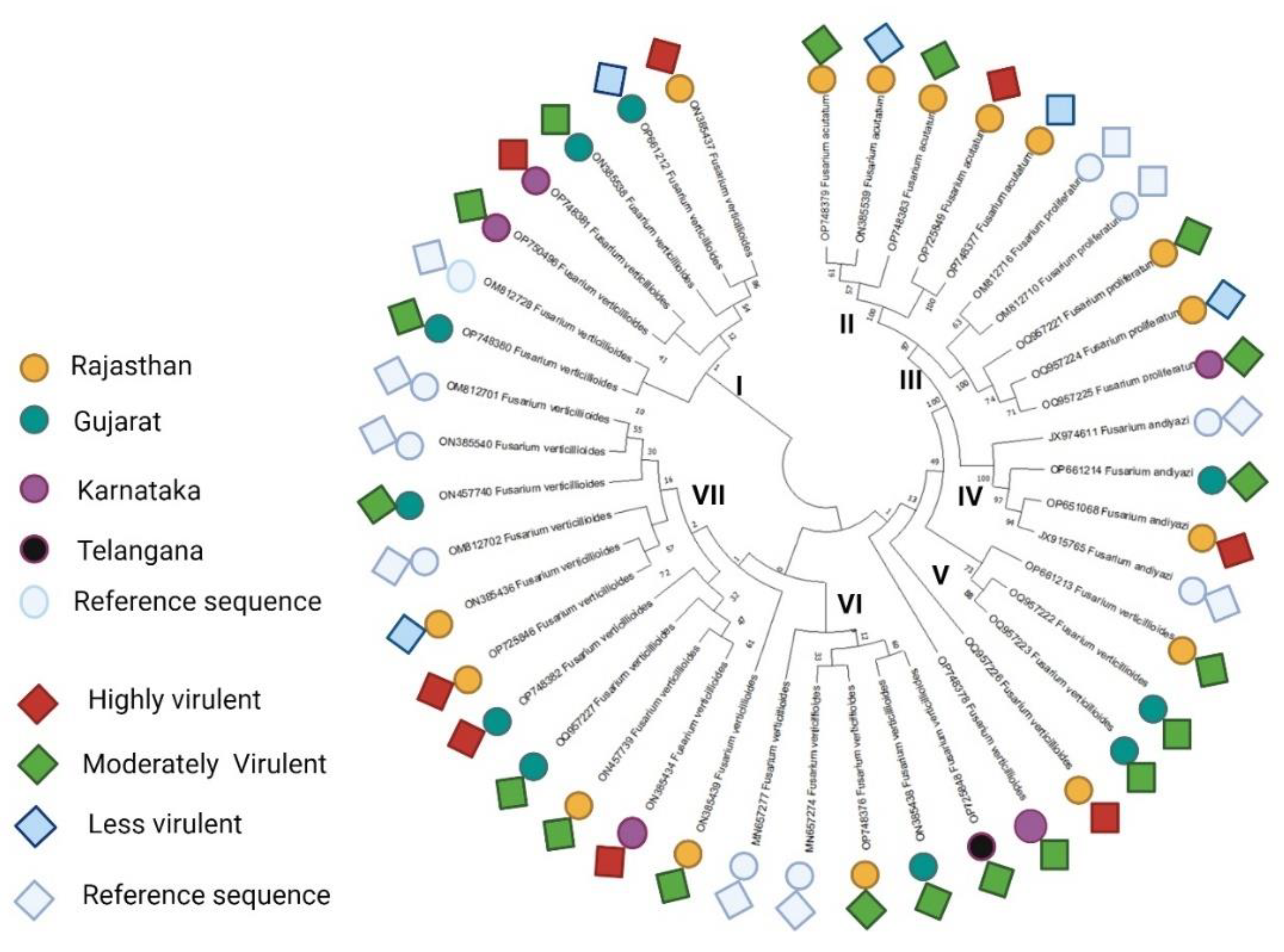

3.3. Phylogenetic Analysis and Evolutionary Relationship of Fusarium Strains Causing FSR

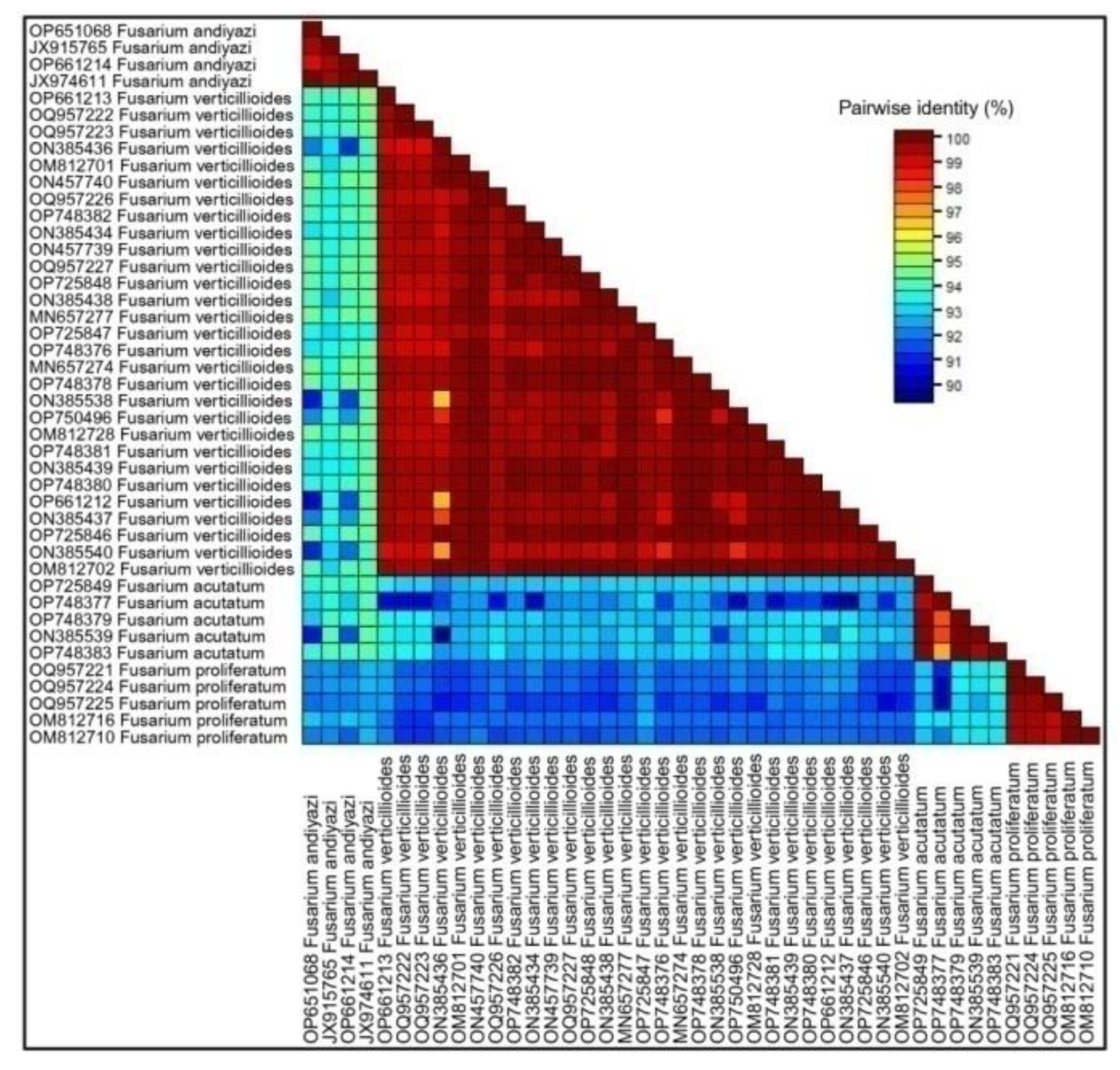

3.4. Relationship among the Geographic Population of Fusarium spp.

3.5. DNA Polymorphism Data

3.6. Genetic Differentiation

3.7. Population Structure

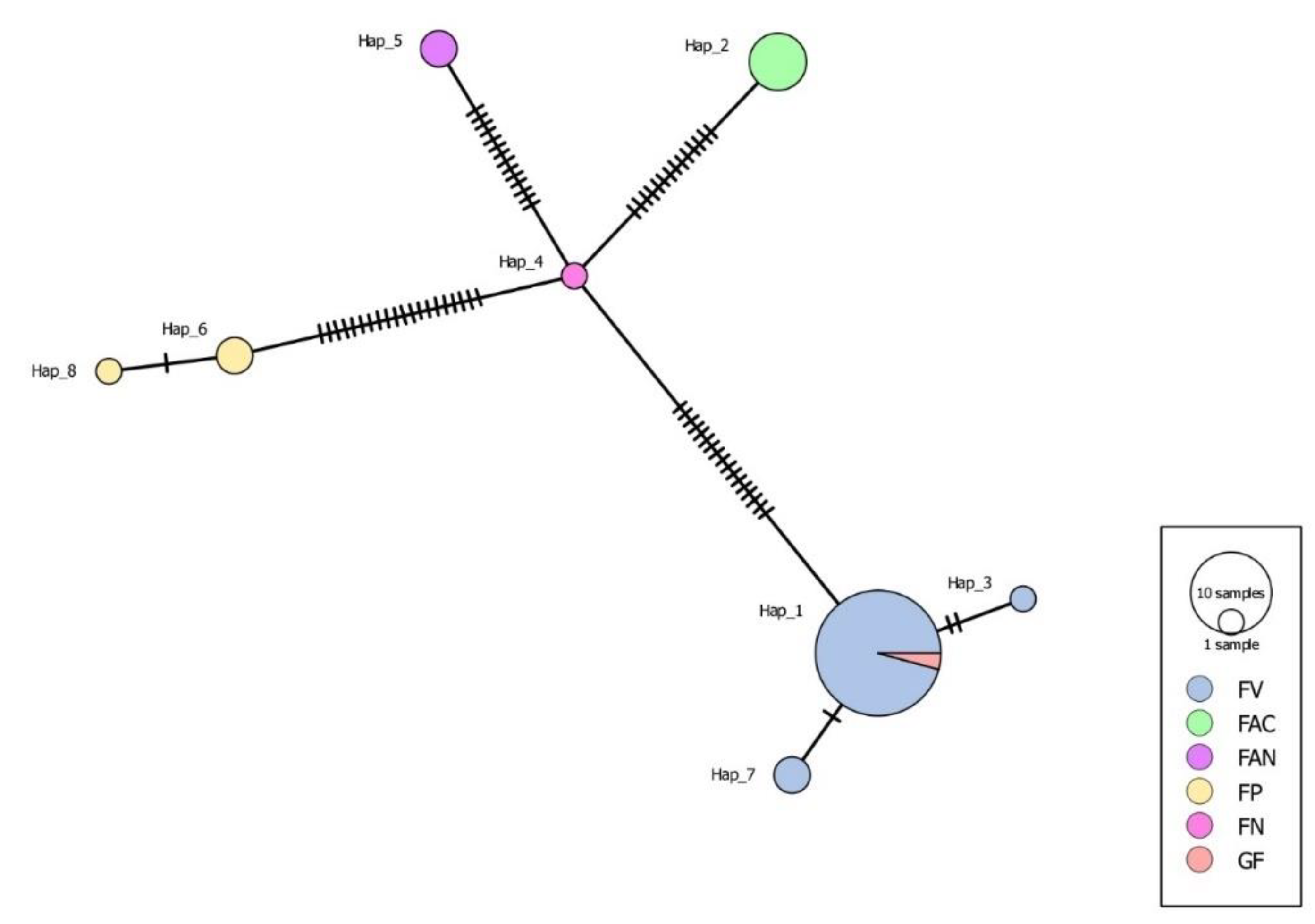

3.8. Haplotype Network Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data availability statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Munkvold, G.P.; Desjardins, A.E. Fumonisins in maize: can we reduce their occurrence? Plant Dis.1997, 81, 556–565. [CrossRef]

- Román, S.G. Caracterización de Genotipos de Maíz (Zea Mays L.) a La Infección de Fusarium verticillioides En DiferentesFases Del Ciclo de Vida de La Planta y Su Correlación Con Marcadores Moleculares de Tipo SNPs. 2017.

- Navale, V.D.; Sawant, A.M.; Vamkudoth, K.R. Genetic diversity of toxigenic Fusarium verticillioides associated with maize grains, India. Genet. Mol. Biol.2023, 46, e20220073. [CrossRef]

- Görtz, A.; Oerke, E.-C.; Steiner, U.; Waalwijk, C.; Vries, I.; Dehne, H.-W. Biodiversity of Fusarium species causing ear rot of maize in Germany. Cereal Res. Commun.2008, 36, 617–622. [CrossRef]

- Gai, X.; Dong, H.; Wang, S.; Liu, B.; Zhang, Z.; Li, X.; Gao, Z. Infection cycle of maize stalk rot and ear rot caused byFusarium verticillioides. PloS One. 2018, 13, e0201588. [CrossRef]

- Harish, J.; Jambhulkar, P.P.; Bajpai, R.; Arya, M.; Babele, P.K.; Chaturvedi, S.K.; Kumar, A.; Lakshman, D.K. Morphological characterization, pathogenicity screening, and molecular identification of Fusarium Spp. isolates causing post-flowering stalk rot in maize.Front. Microbiol.2023, 14, 1121781. [CrossRef]

- Kazan, K.; Gardiner, D.M.; Manners, J.M. On the Trail of a Cereal Killer: Recent advances in Fusariumgraminearumpathogenomics and host resistance. Mol. Plant Pathol.2012, 13, 399–413. [CrossRef]

- Saravanakumar, K.; Li, Y.; Yu, C.; Wang, Q.; Wang, M.; Sun, J.; Gao, J.; Chen, J. Effect of Trichoderma harzianum on maize rhizosphere microbiome and biocontrol of Fusariumstalk rot.Sci. Rep.2017, 7, 1771. [CrossRef]

- Douriet-Angulo, A.; López-Orona, C.A.; López-Urquídez, G.A.; Vega-Gutiérrez, T.A.; Tirado-Ramírez, M.A.; Estrada-Acosta, M.D.; Ayala-Tafoya, F.; Yáñez-Juárez, M.G. Maize Stalk Rot Caused by Fusarium Falciforme (FSSC 3 + 4) in Mexico. Plant Dis.2019, 103, 2951. [CrossRef]

- Shin, J.-H.; Han, J.-H.; Lee, J.K.; Kim, K.S. Characterization of the maize stalk rot pathogens Fusarium subglutinans and F. temperatum and the effect of fungicides on their mycelial growth and colony formation. Plant Pathol. J.2014, 30, 397. [CrossRef]

- Leyva-Madrigal, K.Y.; Larralde-Corona, C.P.; Apodaca-Sánchez, M.A.; Quiroz-Figueroa, F.R.; Mexia-Bolaños, P.A.; Portillo-Valenzuela, S.; Ordaz-Ochoa, J.; Maldonado-Mendoza, I.E. Fusarium species from the Fusariumfujikuroi species complex involved in mixed infections of maize in northern Sinaloa, Mexico. J. Phytopathol.2015, 163, 486–497. [CrossRef]

- Aguín, O.; Cao, A.; Pintos, C.; Santiago, R.; Mansilla, P.; Butrón, A. Occurrence of Fusarium species in maize kernels grown in northwesterns plain. Plant Pathol.2014, 63, 946–951. [CrossRef]

- Stumpf, R.; Santos, J. dos; Gomes, L.B.; Silva, C.N.; Tessmann, D.J.; Ferreira, F.D.; Machinski Junior, M.; Del Ponte, E.M. Fusarium species and fumonisins associated with maize kernels produced in Rio Grande Do Sul State for the 2008/09 and 2009/10 Growing Seasons. Braz. J. Microbiol.2013, 44, 89–95. [CrossRef]

- Mueller, D.S.; Wise, K.A.; Sisson, A.J.; Allen, T.W.; Bergstrom, G.C.; Bosley, D.B.; Bradley, C.A.; Broders, K.D.; Byamukama, E.; Chilvers, M.I.; et al. Corn yield loss estimates due to diseases in the United States and Ontario, Canada from 2012 to 2015. Plant Health Prog.2016, 17, 211–222. [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, C.S.; Richards, C.; Terry, A.; Parra, J.; Shim, W.-B. Genetic variability and geographical distribution of mycotoxigenicFusariumverticillioides strains isolated from maize fields in Texas. Plant Pathol. J.2015, 31, 203. [CrossRef]

- Sandoval-Denis, M.; Swart, W.J.; Crous, P.W. New Fusarium Species from the Kruger National Park, South Africa. MycoKeys2018, 63.

- Al-Hatmi, A.; De Hoog, G.S.; Meis, J.F. Multiresistant Fusarium pathogens on plants and humans: solutions in (from) the antifungal pipeline? Infect. Drug Resist.2019, 12, 3727–3737. [CrossRef]

- Wollenweber, H.W.; Sherbakoff, C.D.; Reinking, O.A.; Johann, H.; Bailey, A.A. Fundamentals for taxonomic studies of Fusarium. J. Agric. Res.1925.30, 833–843.

- O’Donnell, K.; Cigelnik, E.; Nirenberg, H.I. Molecular systematics and phylogeography of the Gibberella Fujikuroi Species Complex. Mycologia1998, 90, 465–493. [CrossRef]

- Geiser, D.M.; Lewis Ivey, M.L.; Hakiza, G.; Juba, J.H.; Miller, S.A. Gibberella Xylarioides (Anamorph: Fusariumxylarioides), a causative agent of coffee wilt disease in Africa, Is a previously unrecognized member of the G.fujikuroi species complex. Mycologia2005, 97, 191–201. [CrossRef]

- O’Donnell, K.; McCormick, S.P.; Busman, M.; Proctor, R.H.; Ward, T.J.; Doehring, G.; Geiser, D.M.; Alberts, J.F.; Rheeder, J.P. Marasas et al. 1984 “Toxigenic Fusarium species: identity and mycotoxicology” revisited. Mycologia2018, 110, 1058–1080. [CrossRef]

- Sandoval-Denis, M.; Guarnaccia, V.; Polizzi, G.; Crous, P.W. Symptomatic citrus trees reveal a new pathogenic lineage in Fusarium and two new neocosmospora species. Persoonia-Mol. Phylogeny Evol. Fungi2018, 40, 1–25.. [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, N.; Sandoval-Denis, M.; Lombard, L.; Visagie, C.M.; Wingfield, B.D.; Crous, P.W. Redefining species limits in the Fusariumfujikuroi species complex. Persoonia-Mol. Phylogeny Evol. Fungi2021, 46, 129–162. [CrossRef]

- Jambhulkar, P.P.; Raja, M.; Singh, B.; Katoch, S.; Kumar, S.; Sharma, P. Potential native Trichodermastrains against Fusariumverticillioides causing post flowering stalk rot in winter maize. Crop Prot.2022, 152, 105838.

- Munkvold, G.P. Epidemiology of Fusarium diseases and their mycotoxins in maize ears. Eur. J. Plant Pathol.2003, 109, 705–713. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Abdelraheem, A.; Zhu, Y.; Elkins-Arce, H.; Dever, J.; Whitelock, D.; Hake, K.; Wedegaertner, T.; Wheeler, T.A. Studies of evaluation methods for resistance to Fusarium wilt race 4 (Fusariumoxysporumf. Sp.vasinfectum) in cotton: effects of cultivar, planting date, and inoculum density on disease progression. Front. Plant Sci.2022, 13, 900131. [CrossRef]

- Figueroa-Rivera, M.G.; Rodríguez-Guerra, R.; Guerrero-Aguilar, B.Z.; González-Chavira, M.M.; Pons-Hernández, J.L.; Jiménez-Bremont, J.F.; Ramírez-Pimentel, J.G.; Andrio-Enríquez, E.; Mendoza-Elos, M. caracterización de Especies de Fusariumasociadas a la pudrición de raíz de maíz en Guanajuato, México. Rev. Mex. Fitopatol.2010, 28, 124–134.

- Ha, M.S.; Ryu, H.; Ju, H.J.; Choi, H.-W. Diversity and pathogenic characteristics of the Fusarium species isolated from minor legumes in Korea. Sci. Rep.2023, 13, 22516. [CrossRef]

- O’Donnell, K.; Kistler, H.C.; Tacke, B.K.; Casper, H.H. Gene genealogies reveal global phylogeographic structure and reproductive isolation among lineages of Fusarium graminearum , the fungus causing wheat scab. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci.2000, 97, 7905–7910. [CrossRef]

- O’Donnell, K.; Ward, T.J.; Robert, V.A.R.G.; Crous, P.W.; Geiser, D.M.; Kang, S. DNA sequence-based identification of Fusarium: current status and future directions. Phytoparasitica2015, 43, 583–595. [CrossRef]

- O’Donnell, K.; Sutton, D.A.; Rinaldi, M.G.; Sarver, B.A.J.; Balajee, S.A.; Schroers, H.-J.; Summerbell, R.C.; Robert, V.A.R.G.; Crous, P.W.; Zhang, N.; et al. Internet-accessible DNA sequence database for identifying fusaria from human and animal infections. J. Clin. Microbiol.2010, 48, 3708–3718. [CrossRef]

- Ramdial, H.; Latchoo, R.K.; Hosein, F.N.; Rampersad, S.N. Phylogeny and haplotype analysis of fungi within the Fusariumincarnatum-equiseti species complex. Phytopathology 2017, 107, 109–120. [CrossRef]

- Ploetz, R.C. Fusarium-induced diseases of tropical, perennial crops. Phytopathology2006, 96, 648–652. [CrossRef]

- Dobbs, J.T.; Kim, M.; Dudley, N.S.; Jones, T.C.; Yeh, A.; Dumroese, R.K.; Cannon, P.G.; Hauff, R.D.; Klopfenstein, N.B.; Wright, S.; et al. Fusarium spp. diversity associated with symptomatic Acacia Koa in Hawaiʽi. For. Pathol.2021, 51, e12713. [CrossRef]

- Leslie, J.F.; Summerell, B.A. Fusarium laboratory workshops—A recent history. Mycotoxin Res.2006, 22, 73–74. [CrossRef]

- Liddell, C.M.; Burgess, L.W. Survival of Fusariummoniliformeat controlled temperature and relative humidity. Trans. Br. Mycol. Soc.1985, 84, 121–130.

- Li, B.; Du, J.; Lan, C.; Liu, P.; Weng, Q.; Chen, Q. Development of a loop-mediated isothermal amplification assay for rapid and sensitive detection of Fusariumoxysporumf. sp.cubenseRace 4. Eur. J. Plant Pathol.2013, 135, 903–911. [CrossRef]

- O’Donnell, K.; Kistler, H.C.; Cigelnik, E.; Ploetz, R.C. Multiple evolutionary origins of the fungus causing panama disease of banana: concordant evidence from nuclear and mitochondrial gene genealogies.Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci.1998, 95, 2044–2049. [CrossRef]

- Hall, T. BioEdit v7. 0.9: Biological sequence alignment editor for win95/98/2K/XP/7 2012.

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Li, M.; Knyaz, C.; Tamura, K. MEGA X: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis across computing platforms.Mol. Biol. Evol.2018, 35, 1547. [CrossRef]

- Librado, P.; Rozas, J. DnaSP v5: A software for comprehensive analysis of DNA polymorphism data.Bioinformatics2009, 25, 1451–1452. [CrossRef]

- Hudson, R.R.; Slatkin, M.; Maddison, W.P. Estimation of levels of gene flow from DNA sequence data. Genetics1992, 132, 583–589. [CrossRef]

- Muhire, B.M.; Varsani, A.; Martin, D.P. SDT: A virus classification tool based on pairwise sequence alignment and identity calculation. PloS One2014, 9, e108277. [CrossRef]

- Schoville, S.D.; Bonin, A.; François, O.; Lobreaux, S.; Melodelima, C.; Manel, S. Adaptive genetic variation on the landscape: methods and cases. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst.2012, 43, 23–43. [CrossRef]

- Ravinet, M.; Faria, R.; Butlin, R.K.; Galindo, J.; Bierne, N.; Rafajlović, M.; Noor, M.A.F.; Mehlig, B.; Westram, A.M. Interpreting the genomic landscape of speciation: A road map for finding barriers to gene flow. J. Evol. Biol.2017, 30, 1450–1477. [CrossRef]

- Sgrò, C.M.; Lowe, A.J.; Hoffmann, A.A. Building evolutionary resilience for conserving biodiversity under climate change. Evol. Appl.2011, 4, 326–337. [CrossRef]

- Milgroom, M.G. Recombination and the multilocus structure of fungal populations. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol.1996, 34, 457–477. [CrossRef]

- McDonald, B.A.; Linde, C. Pathogen population genetics, evolutionary potential and durable resistance. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol.2002, 40, 349–379. [CrossRef]

- Gladieux, P.; Ropars, J.; Badouin, H.; Branca, A.; Aguileta, G.; De Vienne, D.M.; Rodríguez De La Vega, R.C.; Branco, S.; Giraud, T. Fungal evolutionary genomics provides insight into the mechanisms of adaptive divergence in eukaryotes.Mol. Ecol.2014, 23, 753–773. [CrossRef]

- Giraud, M.; Vandiedonck, C.; Garchon, H. Genetic factors in autoimmune myasthenia gravis.Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci.2008, 1132, 180–192. [CrossRef]

- Loxdale, H.D.; Lushai, G. Population genetic issues: the unfolding story using molecular markers. In Aphids as crop pests; Emden, H.F.V., Harrington, R., Eds.; CABI: UK, 2007; pp. 31–67 ISBN 978-1-84593-202-2.

- Kelly, A.C.; Ward, T.J. Population Genomics of Fusariumgraminearum reveals signatures of divergent evolution within a major cereal pathogen. PloS One2018, 13, e0194616. [CrossRef]

- Bacon, C.W.; Yates, I.E. Endophytic root colonization by Fusarium species: histology, plant interactions, and toxicity. InMicrobial root endophytes2006, 9, 133-152. In: Soil Biology, Microbial root endophytes B. Schulz, C. Boyle, T. N. Sieber (Eds.) © Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg.

| Data type | Sample category | Source of variation | df | SS | Variance comp | % Variation | Fixation indices |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Original data | Geographic | Among population | 3 | 1249.56 | 15.84 | 7.87** | |

| Within population | 82 | 15186.8 | 185.21 | 92.12** | FST=0.07878 | ||

| Total | 85 | 16436.35 | 201.05 | 100 |

| Fusarium spp. | F. acutatum | F. andiyazi | F. proliferatum | F.verticillioides |

| F. acutatum | NA | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| F. andiyazi | 0.10533 | NA | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| F. proliferatum | 0.11682 | 0.11073 | NA | 0.001 |

| F. verticillioides | 0.06617 | 0.07984 | 0.07529 | NA |

| DNA polymorphism parameter | Tef 1-α |

| Number of sequences | 38 |

| Selected region analysed | 1-866 |

| Number of polymorphic sites, S | 47 |

| Number of mutations, Eta | 52 |

| Number of haplotypes, h | 8 |

| Haplotype diversity, Hd | 0.589 |

| Nucleotide diversity, π | 0.02390 |

| ϴ (S) | 0.02525 |

| ϴ (π) | 0.02469 |

| Number of nucleotide differences, k | 10.587 |

| Population | Number of sequences | Number of segregating sites (S) | Number of haplotypes (h) | Haplotype diversity (Hd) | Average number of differences (K) | Nucleotide diversity (π) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F. verticillioides | 25 | 3 | 3 | 0.22667 | 0.31333 | 0.00071 |

| F. acutatum | 5 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| F. andiyazi | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| F. proliferatum | 3 | 1 | 2 | 0.66667 | 0.66667 | 0.00150 |

| Total data estimates | 35 | 44 | 7 | 0.58992 | 10.70420 | 0.02411 |

| POPULATION 1 | POPULATION 2 | Hs | Ks | Kxy | Gst | DeltaSt | GammaSt | Nst | Fst | Dxy | Da |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F. verticillioides | F. acutatum | 0.20051 | 0.26111 | 20.16000 | 0.57092 | 0.01252 | 0.95685 | 0.99245 | 0.99223 | 0.04541 | 0.04505 |

| F. verticillioides | F. andiyazi | 0.22667 | 0.29012 | 20.16000 | 0.40387 | 0.00618 | 0.90788 | 0.99245 | 0.99223 | 0.04541 | 0.04505 |

| F. verticillioides | F. proliferatum | 0.24500 | 0.35119 | 27.48000 | 0.30761 | 0.01168 | 0.94254 | 0.98288 | 0.98217 | 0.06189 | 0.06079 |

| F. acutatum | F. andiyazi | 0.00000 | 0.00000 | 17.00000 | 1.00000 | 0.01563 | 1.00000 | 1.00000 | 1.00000 | 0.03829 | 0.03829 |

| F. acutatum | F. proliferatum | 0.16667 | 0.25000 | 25.33333 | 0.55720 | 0.02651 | 0.98604 | 0.98733 | 0.98684 | 0.05706 | 0.05631 |

| F. andiyazi | F. proliferatum | 0.66667 | 0.40000 | 22.33333 | 0.44700 | 0.02390 | 0.97549 | 0.98556 | 0.98507 | 0.05030 | 0.04955 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).