Submitted:

08 May 2024

Posted:

08 May 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Questionnaires and Data Collection

2.4. Data and Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Socio-Demographic Characteristics

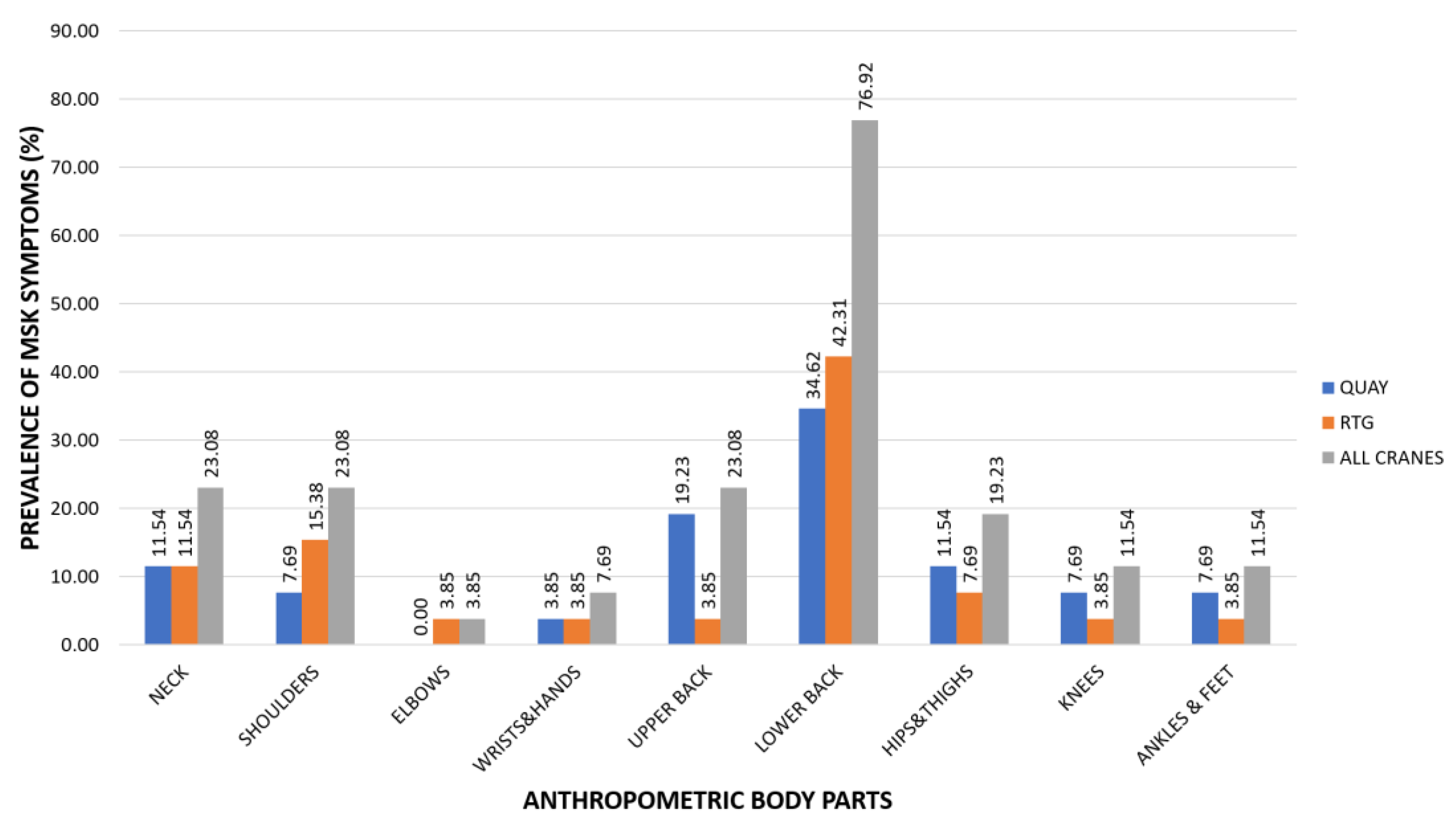

3.2. Self-Reported Anthropometric MSK Problem Prevalence

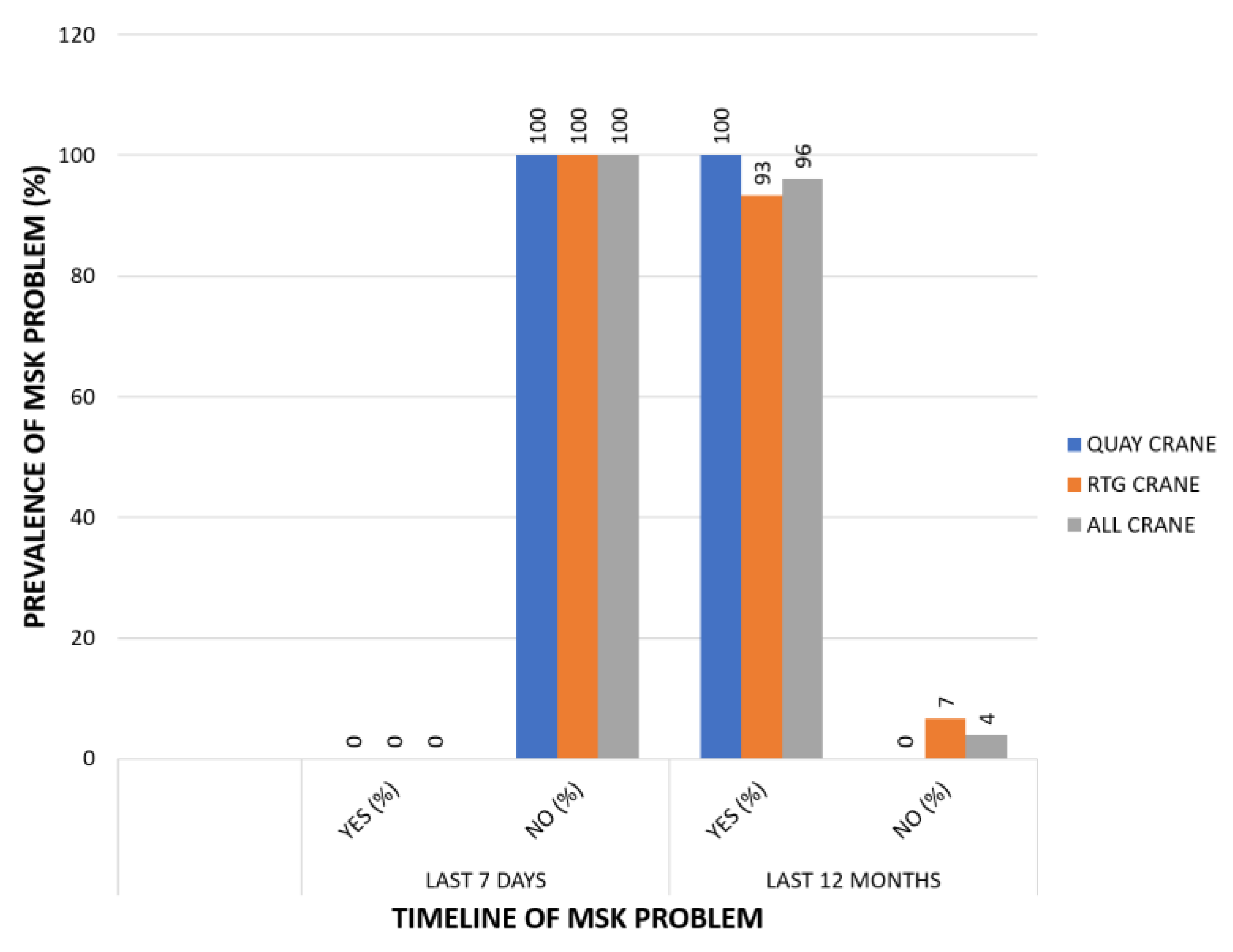

3.3. Prevalence of Self-Reported MSK Problem during the Last 12-Months and Past 7 Days

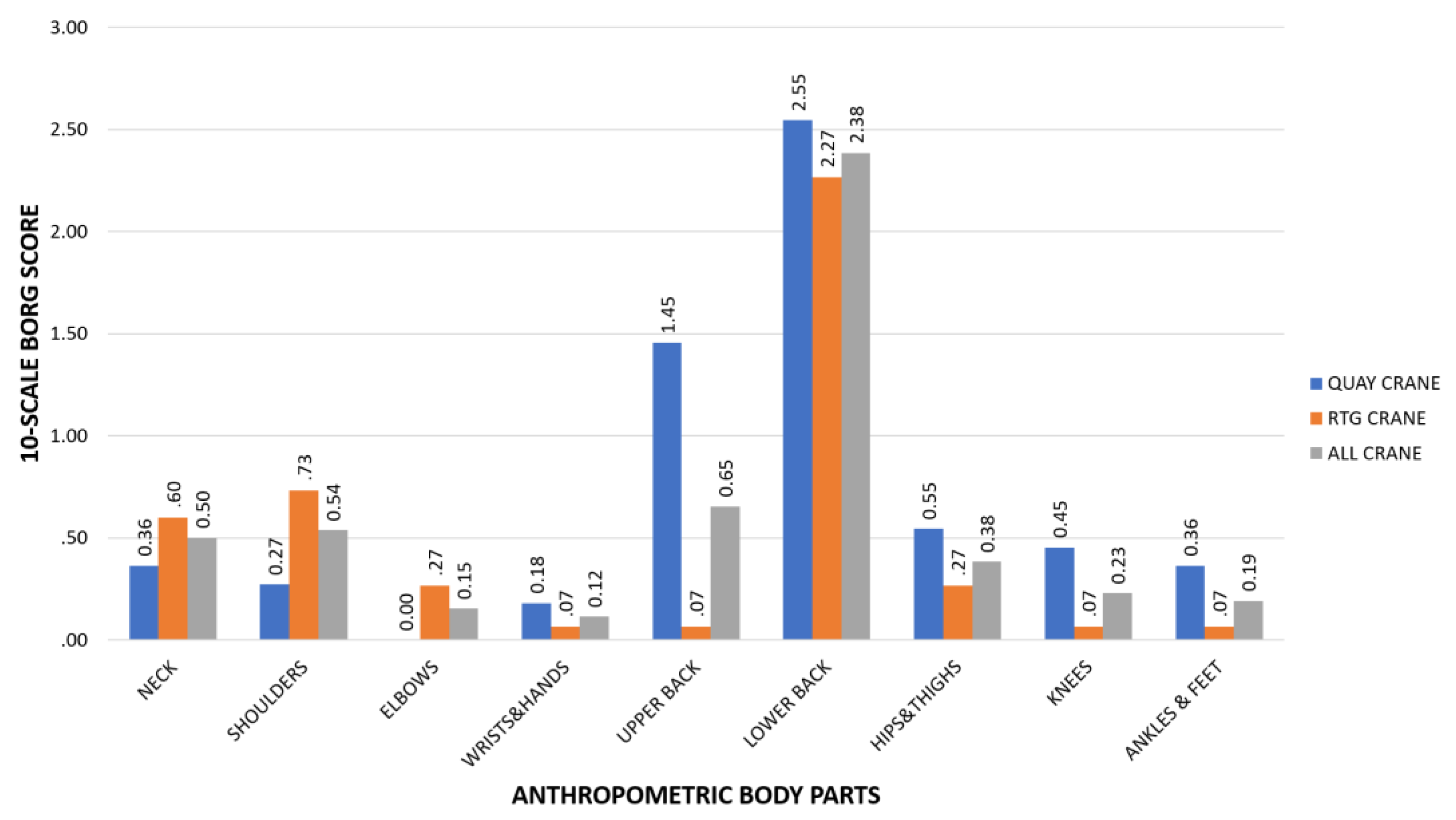

3.4. Perceived Discomfort (Borg CR10 Scale)

3.5. MSK Prevalence and Perceived Discomfort Levels among Quay and RTG Crane Operators Regarding Different Body Parts

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- UNCTAD. Review of Maritime Transport (Series). Available online: https://unctad.org/en/Pages/Publications/Review-of-Maritime-Transport-(Series).aspx (accessed on 24 Aug).

- Thailand Convention & Exhibition Bureau. Maritime industry of Thailand. Available online: https://intelligence.businesseventsthailand.com/en/industry/maritime-industry (accessed on 25 Aug).

- CEIC. Thailand Container Port Throughput. Available online: https://www.ceicdata.com/en/indicator/thailand/container-port-throughput (accessed on.

- Chang, D.; Fang, T.; Fan, Y. Dynamic rolling strategy for multi-vessel quay crane scheduling. Advanced Engineering Informatics 2017, 34, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galle, V.; Barnhart, C.; Jaillet, P. Yard Crane Scheduling for container storage, retrieval, and relocation. European Journal of Operational Research 2018, 271, 288–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eko Mardiyanto; Denny Ardyanto; Notobroto, H. B. Container Crane Operator Ergonomics Analysis PT. X Port Of Tanjung Perak, Surabaya. Civil and Environmental Research 2015, 17, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Leban, B.; Fancello, G.; Fadda, P.; Pau, M. Changes in trunk sway of quay crane operators during work shift: A possible marker for fatigue? Applied Ergonomics 2017, 65, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fadda, P.; Meloni, M.; Fancello, G.; Pau, M.; Medda, A.; Pinna, C.; Del Rio, A.; Lecca, L.I.; Setzu, D.; Leban, B. Multidisciplinary Study of Biological Parameters and Fatigue Evolution in Quay Crane Operators. Procedia Manufacturing 2015, 3, 3301–3308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OSHA. Ergonomics. Available online: https://www.osha.gov/SLTC/ergonomics/ (accessed on.

- Haq SA, R.J. , Darmawan J, Chopra A.. WHO-ILAR-COPCORD in the Asia-Pacific: the past, present and future. Int J Rheum Dis. 2008;11(1):4–10. 2008, 11, 4–10. [Google Scholar]

- World Shipping Council. Top 50 world container ports. Available online: http://www.worldshipping.org/about-the-industry/global-trade/top-50-world-container-ports (accessed on 14 May).

- Hutchisonports. Laem Chabang Port. Available online: https://hutchisonports.co.th/laem-chabang-port/ (accessed on 31 Aug.).

- Laem Chabang International Terminal Co., L. Facility & Equipment. Available online: https://www.lcit.com/facilityEquipment.asp (accessed on.

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Lang, A.G.; Buchner, A. G*Power 3: a flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior research methods 2007, 39, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuorinka, I.; Jonsson, B.; Kilbom, A.; Vinterberg, H.; Biering-Sorensen, F.; Andersson, G.; Jorgensen, K. Standardised Nordic questionnaires for the analysis of musculoskeletal symptoms. Appl Ergon 1987, 18, 233–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shariat, A.; Cleland, J.A.; Danaee, M.; Alizadeh, R.; Sangelaji, B.; Kargarfard, M.; Ansari, N.N.; Sepehr, F.H.; Tamrin, S.B.M. Borg CR-10 scale as a new approach to monitoring office exercise training. Work (Reading, Mass.) 2018, 60, 549–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griep, M.I.; Borg, E.; Collys, K.; Massart, D.L. Category ratio scale as an alternative to magnitude matching for age-related taste and odour perception. Food Quality and Preference 1998, 9, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohd Azlan Fahmi Muhammad Azmi; Azanizawati Ma’aram; Aini Zuhra Abdul Kadir; Ngadiman, N. H.A. Risk Factors of Low Back Pain Amongst Port Crane Operator in Malaysia International Journal of Innovative Technology and Exploring Engineering (IJITEE) 2019, 8, 1434–1439.

- National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). Musculoskeletal Disorders and Workplace Factors. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/docs/97-141/pdfs/97-141.pdf. (accessed on 19 Aug.).

- Bovenzi, M. , Pinto, I., Stacchini, N. Low back pain in port machinery operators. Journal of Sound and vibration 2002, 253, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pigini, L.; , Colombini, D., Brieda, S., Fanti, M. Ergonomic solutions in designing workstations for operators of cranes on harbours. Available online: http://www.epmresearch.org/userfiles/files/2006%20IEA%2010-14%20LUGLIO%20MAASTRICHTPIGINI-BRIEDA.pdf. (accessed on 19 Aug).

- Huysmans, M.A.; de Looze, M.P.; Hoozemans, M.J.M.; van der Beek, A.J.; van Dieën, J.H. The effect of joystick handle size and gain at two levels of required precision on performance and physical load on crane operators. Ergonomics 2006, 49, 1021–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OSHA Safety Manual. OCCUPATIONAL VIBRATION EXPOSURE. Available online: https://www.safetymanualosha.com/occupational-vibration-exposure/ (accessed on December).

- MOHD AZLAN; AZMI, F. B.M. ERGONOMICS OF QUAY CRANE WORKSTATION Faculty of Mechanical Universiti Teknologi Malaysia 2017.

- Marjanen, Y. Validation and improvement of the ISO 2631-1 (1997) standard method for evaluating discomfort from whole-body vibration in a multi-axis environment. 2010.

- Standardization, I.O.f. Guide for the evaluation of human exposure to whole body vibration - Part 1. General requirements.

- Bongers, P.M.; Boshuizen, H.C.; Hulshof, C.T.J.; Koemeester, A.P. Back disorders in crane operators exposed to whole-body vibration. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health 1988, 60, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wahlström, J.; Burström, L.; Johnson, P.W.; Nilsson, T.; Järvholm, B. Exposure to whole-body vibration and hospitalization due to lumbar disc herniation. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 2018, 91, 689–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Z. A. Kadir; R. Mohammad; Othman, N.;. Low Back Pain Problem amongst Port Crane Operator. Journal of Advanced Research in Applied Sciences and Engineering Technology 2015, 1, 13–26. [Google Scholar]

- Nourollahi-Darabad, M.; Mazloumi, A.; Saraji, G.N.; Afshari, D.; Foroushani, A.R. Full shift assessment of back and head postures in overhead crane operators with and without symptoms. Journal of Occupational Health 2018, 60, 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hareendran, A.; Leidy, N.K.; Monz, B.U.; Winnette, R.; Becker, K.; Mahler, D.A. Proposing a standardized method for evaluating patient report of the intensity of dyspnea during exercise testing in COPD. International journal of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease 2012, 7, 345–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- PEMA, P.E.M.A. Crane Operator Health & Safety; Port Equipment Manufacturers Association (PEMA): Brussels, Belgium, 2018; p. 8. [Google Scholar]

- Liebherr Container Cranes. Technical Description Ship to Shore Gantry Cranes. Available online: https://www.liebherr.com/shared/media/maritime-cranes/downloads-and-brochures/brochures/lcc/liebherr-sts-cranes-technical-description.pdf (accessed on Aug, 5).

- Precision pain care & rehabilitation. Causes of Upper Back Pain. Available online: https://www.precisionpaincarerehab.com/blog/causes-of-upper-back-pain-21297.html (accessed on Aug, 3).

- Liebherr Container Cranes. Technical Description Rubber Tyre Gantry Crane. Available online: https://www.liebherr.com/shared/media/maritime-cranes/downloads-and-brochures/brochures/lcc/liebherr-rtg-cranes-technical-description.pdf (accessed on Aug, 5).

- Stewart G., Eidelson; Cristol, H. Upper Back Pain Causes, Risk Factors, Diagnosis and Treatment Written by Stewart G. Eidelson, MD and Hope Cristol; Reviewed by Reginald Q. Knight, MD, MHA. Available online: https://www.spineuniverse.com/conditions/upper-back-pain (accessed on.

- J. Talbot Sellers, D. All About Upper Back Pain. Available online: https://www.spine-health.com/conditions/upper-back-pain/all-about-upper-back-pain (accessed on Aug, 3).

- Nourollahi-Darabad, M.; Mazloumi, A.; Saraji, G.N.; Afshari, D.; Foroushani, A.R. Full shift assessment of back and head postures in overhead crane operators with and without symptoms. J Occup Health 2018, 60, 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sa-ngiamsak, T. Exploring study protocols examining muscle fatigue among transportation and transshipment operators: a systematic review. International Journal of Occupational and Environmental Safety, 2019; 3, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MOHD AZLAN FAHMI B MUHAMMAD AZMI. ERGONOMICS OF QUAY CRANE WORKSTATION. Universiti Teknologi Malaysia, Malaysia, 2017.

| Variable | Quay | RTG | All Port Cranes* | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Main category | Sub category | (n) | (%) | (n) | (%) | (n) | (%) | |

| Age (years) | 20-30 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4 | |

| 31-40 | 3 | 12 | 8 | 31 | 11 | 42 | ||

| 41-50 | 4 | 15 | 5 | 19 | 9 | 35 | ||

| 51-60 | 3 | 12 | 2 | 8 | 5 | 19 | ||

| Total | 11 | 42 | 15 | 58 | 26 | 100 | ||

| Statistics | χ2 | 3 | n/a | |||||

| p | 0.464 | |||||||

| BMI | Underweight (BMI < 18.5) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 4 | |

| Healthy Normal (18.6 - 22.9) | 1 | 4 | 4 | 15 | 5 | 19 | ||

| Overweight (23.0 - 24.9) | 4 | 15 | 2 | 8 | 6 | 23 | ||

| Pre-Obese (25.0 - 29.9) | 4 | 15 | 5 | 19 | 9 | 35 | ||

| Obese (BMI ≥ 30.0) | 2 | 8 | 3 | 12 | 5 | 19 | ||

| Total | 11 | 42 | 15 | 58 | 26 | 100 | ||

| Statistics | χ2 | 3.147 | n/a | |||||

| p | 0.641 | |||||||

| Education | Lower than Senior High School/Vocational Certificate | 5 | 19 | 3 | 12 | 8 | 31 | |

| Senior High School/Vocational Certificate | 5 | 19 | 7 | 27 | 12 | 46 | ||

| Diploma/High Vocational Certificate | 1 | 4 | 4 | 15 | 5 | 19 | ||

| Bachelor Degrees or Higher | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 4 | ||

| Total | 11 | 42 | 15 | 58 | 26 | 100 | ||

| Statistics | χ2 | 2.903 | n/a | |||||

| p | 0.407 | |||||||

| Work Experience(years) | < 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 1-5 | 3 | 12 | 3 | 12 | 6 | 23 | ||

| 6-10 | 4 | 15 | 5 | 19 | 9 | 35 | ||

| 11-15 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 15 | 5 | 19 | ||

| 16-20 | 2 | 8 | 2 | 8 | 4 | 15 | ||

| 21-25 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 8 | ||

| Total | 11 | 42 | 15 | 58 | 26 | 100 | ||

| Statistics | χ2 | 1.737 | n/a | |||||

| p | 0.918 | |||||||

| Factors | MSK Prevalence | Perceived discomfort scores | |||||

| Statistics | Quay | RTG | Statistics | Quay | RTG | ||

| Body Parts | Neck | Yes (%) | 11.54 | 11.54 | Mean | 0.36 | 0.60 |

| No (%) | 30.77 | 46.15 | SD | 0.67 | 1.45 | ||

| χ2 | 0.189 | χ2 | 0.061 | ||||

| p | 0.509 | p | 0.805 | ||||

| Shoulders | Yes (%) | 7.69 | 15.38 | Mean | 0.27 | 0.73 | |

| No (%) | 34.62 | 42.31 | SD | 0.65 | 2.09 | ||

| χ2 | 0.257 | χ2 | 0.036 | ||||

| p | 0.491 | p | 0.850 | ||||

| Elbows | Yes (%) | 0.00 | 3.85 | Mean | 0.00 | 0.27 | |

| No (%) | 42.31 | 53.85 | SD | 0.00 | 0.80 | ||

| χ2 | 0.763 | χ2 | 1.525 | ||||

| p | 0.577 | p | 0.217 | ||||

| Wrists & Hands | Yes (%) | 3.85 | 3.85 | Mean | 0.18 | 0.07 | |

| No (%) | 38.46 | 53.85 | SD | 0.60 | 0.26 | ||

| χ2 | 0.053 | χ2 | 0.079 | ||||

| p | 0.677 | p | 0.779 | ||||

| Upper back | Yes (%) | 19.23 | 3.85 | Mean | 1.45 | 0.07 | |

| No (%) | 23.08 | 53.85 | SD | 1.81 | 0.26 | ||

| χ2 | 5.379 | χ2 | 5.894 | ||||

| p | 0.032* | p | 0.015* | ||||

| Lower Back | Yes (%) | 34.62 | 42.31 | Mean | 2.55 | 2.27 | |

| No (%) | 7.69 | 15.38 | SD | 2.11 | 2.22 | ||

| χ2 | 0.257 | χ2 | 0.143 | ||||

| p | 0.491 | p | 0.706 | ||||

| Hips & Thighs | Yes (%) | 11.54 | 7.69 | Mean | 0.55 | 0.27 | |

| No (%) | 30.77 | 50.00 | SD | 1.04 | 0.80 | ||

| χ2 | 0.794 | χ2 | 0.753 | ||||

| p | 0.346 | p | 0.385 | ||||

| Knees | Yes (%) | 7.69 | 3.85 | Mean | 0.45 | 0.07 | |

| No (%) | 34.62 | 53.85 | SD | 1.04 | 0.26 | ||

| χ2 | 0.824 | χ2 | 0.964 | ||||

| p | 0.381 | p | 0.326 | ||||

| Ankles & Feet | Yes (%) | 7.69 | 3.85 | Mean | 0.36 | 0.07 | |

| No (%) | 34.62 | 53.85 | SD | 0.92 | 0.26 | ||

| χ2 | 0.824 | χ2 | 0.875 | ||||

| p | 0.381 | p | 0.349 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).