1. Introduction

Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) may contribute to sustainability by internal and external acts, through activities based on their sustainability policy, their campus sustainability, their environmental initiatives, and their curricula and research. Universities are also expected to engage internally and externally, being an active agent in the regions where they are implanted [

1].

Previous works studied the importance of the different HEIs stakeholders in fostering sustainability, namely top management, teachers, and students. In fact, studies have demonstrated the key contribution made by teachers in achieving sustainable development goals (SDG) [

2]. However, few research have addressed students' insights in this matter and, assuming that today students will soon be the world leaders, a better understanding of their opinions and attitudes to SDG must be gathered [

3].

The educational task of HEI´s in society assigns a very significant role for them in the establishment of sustainability [

4]. By assembling and expressing suitable curricula and course plans, the HEIs can induce sustainability concerns into students’ characters, with the organization behavior and values influencing each student uniqueness, worldview, and ethics. Thus, the importance of HEI as such and their future changes for the conception of sustainable society are recognized and projected [

5].

Sustainable and integrated water management should be one of the main concerns of the activity of any HEI, motivating adequate education, research and services to the community [

6]. Mismanagement and over-consumption have made the water resources scarce and endangered. In order to carry this information to the public and promote change, it is important to understand the current attitude towards the topic of the students attending higher education, in order to develop more embattled methods to raise consciousness and inspire and allow consumers to adopt water-saving habits or choose wisely when acquiring equipment. In fact, proper water management involves, among other things, increasing efficiency and good water consumption practices [

7].

The topic of natural resource preservation has increased the attention of individuals across the world, allowing people who are disconnected from the issue of water conservation to become aware of how water depletion may directly or indirectly affect their lives [

8]. Forecasting how individuals or groups will respond to the potential risk of water scarcity is important in developing educational curriculum, marketing campaigns and effective conservation methods [

9].

Demographic characteristics, such as age, education, gender, and political orientation[

10,

11,

12] have been shown to influence environmental consciousness and preservation. However, little official research concerning university students has studied their insights, purposes, or actions regarding the issue of water conservation. The study carried out by Barreiros et al. [

13] provided some understandings into water consumption and their water management approaches adopted at HEIs in Portugal, highlighting the relevance of monitoring water use, the use of reducers on taps and the implementation of awareness campaigns, as good practices. But the awareness of students is not guaranteed by good water practices in HEI.

The present study was conducted by the Working Group on Efficient Use of Water (WGEUW), of the Portuguese Sustainable Campus Network (RCS-Portugal). The Portuguese Sustainable Campus Network (RCS-Portugal) was established in 2018 as a collaborative platform for academia to address sustainable development challenges. Its objectives include mobilizing the academic community, creating strategies for sustainable practices in higher education institutions (HEIs), fostering cooperation among network members, and promoting joint initiatives among HEIs for sustainability. The Working Group on Efficient Use of Water (WGEUW) focuses on implementing water efficiency measures on HEIs' campuses and transforming them into hubs for demonstrating good practices.

This research aims to understand attitudes and behaviors regarding water conservation in the academic community, shedding light on the diverse perspectives that students bring to the crucial topic of sustainable water use and contributing to creating awareness about water scarcity issue, one of the biggest challenges of this century worsened by climate change. By comprehensively examining these dimensions, the research aims to contribute valuable knowledge that can inform policies, educational initiatives and practices aimed at promoting an environmentally more conscious and water-efficient mindset among the student population at Portuguese HEIs. Through this research, we aspire to cultivate a deeper understanding of the intricate interplay between environmental awareness, individual behaviors, and the overarching goal of sustainable water management.

The primary goal of the survey was to assess students' knowledge, perceptions, and practices related to water efficiency, and to gather their opinions on the integration of water efficiency measures in the campus, curriculum, and future workplaces. The research had two overarching objectives. The first objective aimed to test and evaluate students' attitudes and levels of environmental awareness regarding the sustainable use of water and the second objective sought to analyze the role of HEIs in addressing water efficiency.

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characterization

The seven HEIs that participated in the study are public institutions, spread across the country, and include the two Portuguese higher education subsystems, Universities and Polytechnics.

Table 1 shows the characterization of the students from the different HEIs participating in this research.

The survey gathered responses from a total of 663 students across various fields and study levels at the seven HEIs. For statistical validity, the sample size should reflect the overall student population, which numbered 45 142 in 2023. Using Cochran’s modified formula for finite populations [

17], the sample size of 663 has a 99% confidence level and a maximum margin of error of 5% which is considered a satisfactory and representative probe.

The sample respondents answered as 50% female, 48.9% male and 0.8% other. Most individuals (66%) are aged between 17 and 23, with 36% between 17 and 20 and 30% between 21 and 23, which was expected. However, 13.4% of respondents are over 33 years old. The 7 HEIs are distributed across different NUTs (Nomenclature of territorial units for statistics) according to Commission Delegate Regulation 2019/1755 of 8 August.

Regarding country of origin, 86.0% are Portuguese and 14% are foreigners. Among the students who answered the survey, 16.4% are pursuing a master's degree and 69.4% are pursuing a graduate degree. Engineering and technologies represent 50.8% of the study areas, followed by medical and health sciences (11.8%), agricultural sciences (3.3%), exact sciences (0.8%), and natural sciences (3.2%).

3.2. Importance of Water Resources

The perception of students regarding the importance of water resources (RQ1) was assessed though two main questions: 1) the agreement/disagreement with 5 different water related statements and 2) what are the expected changes in water resources that can occur in Portugal in the next 50 years.

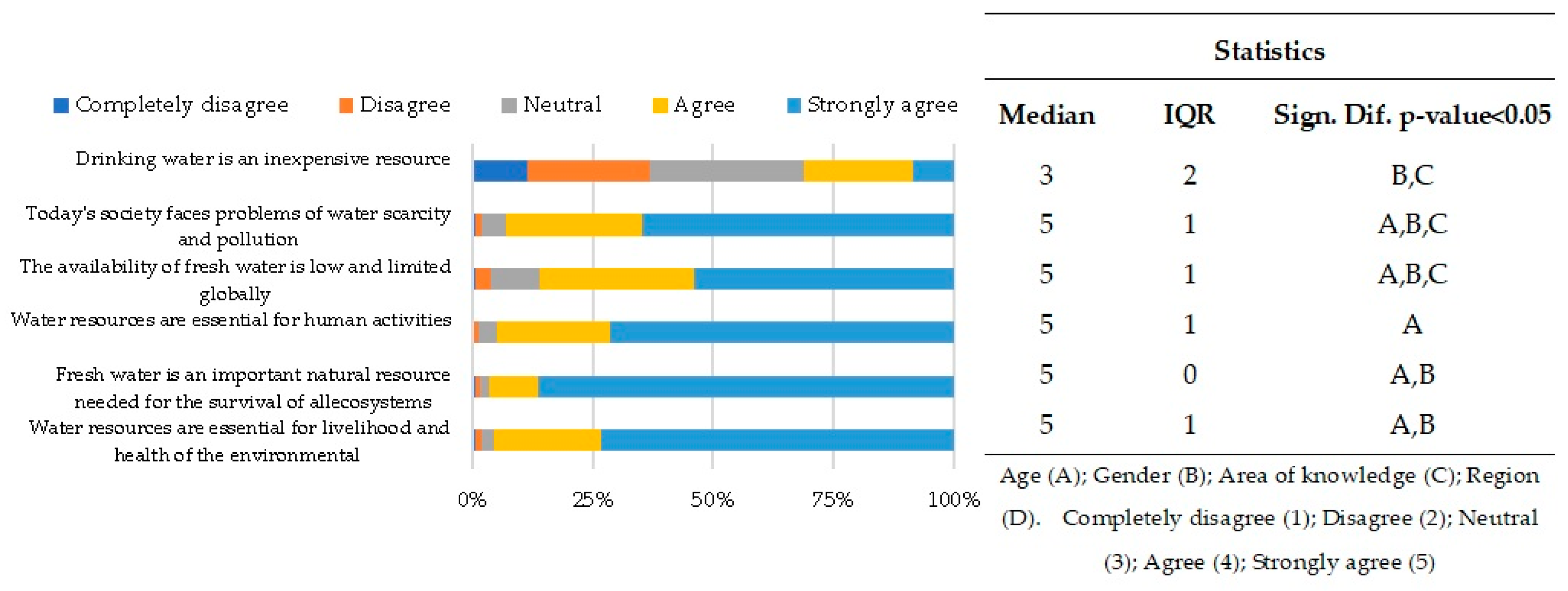

Importance of water resources related statements

Students were asked to classify their level of agreement/disagreement with 5 different water related statements:

- −

Water resources are essential for the livelihood and health of the environment;

- −

Water resources are essential for human activities;

- −

The availability of fresh water is low and limited globally;

- −

Today’s society faces problems of water scarcity and pollution;

- −

Drinking water is an inexpensive resource.

Most answers to these questions demonstrated agreement, except for the last one in which there was significant dispersion with most neutral answers. This result is not totally unexpected and show a relation with the geographical origin of the respondent. The answers to these questions had Median=5 and IQR=1 with the greatest dispersion in the last one.

Most of the answers correspond to a strong agreement, which shows that the respondents recognize the importance of the water resource and are concerned about the problems of pollution and scarcity (

Figure 1).

There were significant differences in the distribution of responses by age group and gender on the question of whether water resources are essential for life and for the health of the environment. Students in the older age groups and women were more likely to strongly agree (100% and 79.6% respectively).

There were significant differences in the distribution of responses by age group and gender when asked whether they thought fresh water was an important natural resource needed for the survival of all ecosystems. Students in the older age groups and women were more likely to strongly agree (97.8% and 91% respectively).

When asked whether they considered water resources to be essential for human activities, there were significant differences in the distribution of responses by age group. Students in the older age groups were more likely to strongly agree (83.1%).

There were significant differences in the distribution of responses by age group, gender and area of knowledge when asked whether they thought the availability of fresh water worldwide was low and limited. Older students and women were more likely to strongly agree (71.9% and 63.5% respectively). Students in Exact sciences and Natural Sciences were more likely to agree or strongly agree (80% and 85.7% respectively).

As to whether they think that today's society faces problems of water scarcity and pollution, there were significant differences in the distribution of responses by age group, gender, and area of knowledge. Students in the older age groups and women were more likely to strongly agree (80.9% and 76.9% respectively). A significant number of students in Exact Sciences and Natural Sciences responded only with a simple “agree”.

When asked whether they thought drinking water was an inexpensive resource, there were significant differences in the distribution of responses by gender and scientific discipline. Women were more likely to disagree or strongly disagree (41%) and men were more likely to agree (34%). Students in social sciences and medicine were the most likely to disagree or strongly disagree (44.9% and 46.2% respectively). Students in Engineering and Technology show an even distribution of response percentages between Disagree / Neutral / Agree. This greatest dispersion in this question responses can be linked to the answer regarding the question about how much does a liter of tap water costs. Most participants do not know how much a liter of water costs, but only 38% recognize this, and only 13% selected "less than 0.5 cents" as their response. Also, water prices in Portugal are not uniform across regions; a DECO study using 2021 prices states that the lowest possible value per liter is 0.03 cents, and the highest possible value is 0.2 cents [

18].

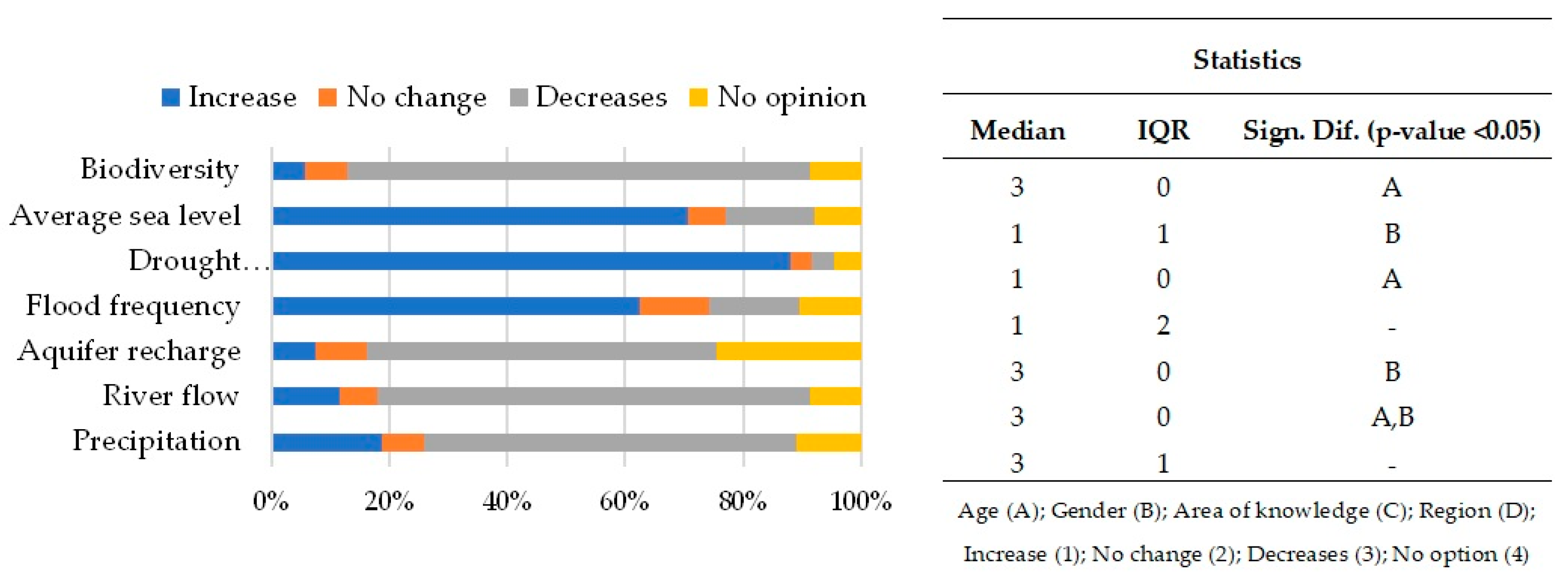

Changes in water resources that can occur in Portugal in the next 50 years

Students were asked to classify the expected changes in 7 issues related with water resources: 1) biodiversity, 2) average sea level, 3) drought frequency, 4) flood frequency, 5) aquifer recharge, 6) river drainage and 7) precipitation.

For precipitation, river flow, aquifer recharge and biodiversity, most responses show a decreasing trend (median=3) with almost no dispersion (IQR=1 or IQR=0). On the other hand, for the frequency of floods and droughts and mean sea level, the vast majority of responses show an increasing trend (median=1). The largest dispersion is seen for the frequency of floods, although the increase in flood frequency is clearly stated (62.4%) (

Figure 2).

The whole of the responses seems to show a significant awareness of the foreseen incoming challenges for the next 50 years.

Regarding changes in river flow, there were significant differences in the distribution of responses by age group and gender. Older students were more likely to say that river flows would decrease (85.4%). Female students were more likely to say that river flows would decrease (74.3%).

As for changes in groundwater recharge, there were significant differences in the distribution of responses by gender. Female students were more likely to have no opinion (28.4%).

There were significant differences in the distribution of responses by age group about changes in the frequency of droughts. Older students were more likely to say that the frequency of droughts was increasing (93.3%).

Regarding changes in mean sea level, there were significant differences in the distribution of responses by gender. Male students were more likely to say that there had been an increase (74.4%).

Finally, changes in biodiversity prompted significant differences in the distribution of responses by age group. Older students were more likely to say that biodiversity was decreasing (88.8%).

3.3. Water Efficiency Practices

Students' perception regarding water consumption (RQ2) and their perception regarding measures to reduce water consumption (RQ3) were assessed in the following dimensions:

- −

qualitative and quantitative assessment of water consumption in daily activities

- −

Average daily consumption per capita in Portugal

- −

Overall and individual measures to promote an efficient water management

- −

Reduction of water waste in HEI campus.

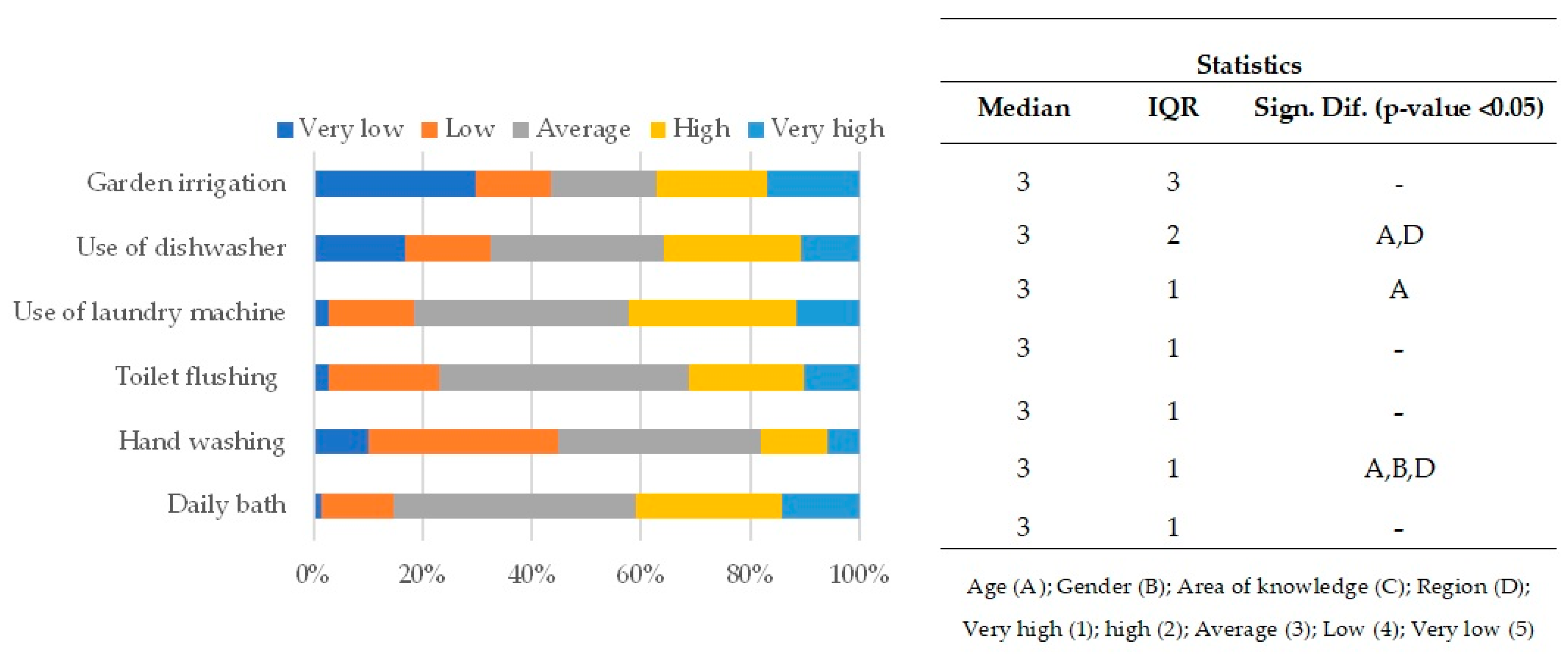

Water consumption qualification of daily activities

Students' perception regarding water consumption were evaluated in two phases, both in multiple daily practices. First a consumption qualification (

Figure 3), followed by a consumption quantification. The activities included were “Garden irrigation”, “Use of dishwasher”, “Use of laundry machine”, “Toilet flushing”, “Hand washing” and “Daily bath”.

For all activities except “Use of laundry machine” more than 60% of responses refer to an average, low or very low consumption, which may demonstrate care in daily practices. A median value of 3 was obtained for all questions, which corresponds to the "average" with almost weak dispersion (IQR=1) except for inquiries concerning the “Use of dishwasher” (IQR=2) and water consumption for “Garden irrigation” (IQR =3). Regarding water consumption for “Garden irrigation”, the participants were divided into two groups with opposite responses.

Regarding “Daily bath”, “Food preparation”, and “Use of laundry machine”, there were no significant differences in any of the classes analyzed.

Regarding “Hand washing”, there were significant differences in the distribution of responses by age group, gender, and region.

This result raises a question whether they have an accurate understanding of the real consumption of the activities in which they seem to be careful.

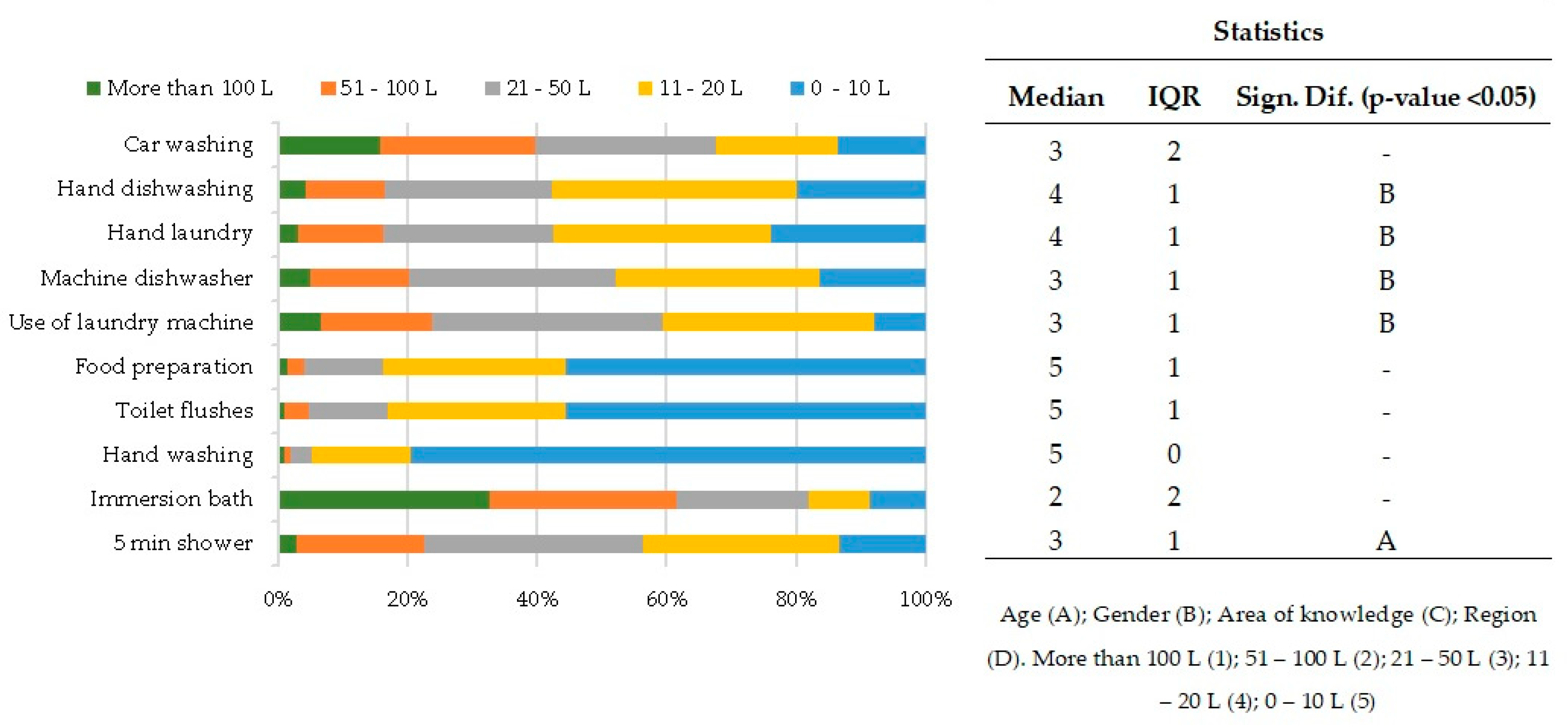

Individual water consumption of daily activities

The students show a slight underestimation of water consumption for daily tasks, (

Figure 4) with exception of “machine dishwasher” in which consumption is overestimated. Approximately 43% of students said that the amount of water used in a 5-minute shower was less than 21 L, while 30% said that the amount of water used in an immersion bath was less than 50 liters. According to ANQIP [

19] specifications for a shower tap, the value in a 5-minute shower should vary between 25 and 150 L, depending on the type of tap installed.

It is during the manual laundry and dishwashing processes that students are least aware of the necessity of water consumption. Approximately 84% of students said that the amount of water used in manual laundry is less than 51 L, and 58% of students said that the amount of water used in manual dishwashing processes is less than 20 L.

In contrast to what Fan et al. [

20] stated, there was no significant difference in response rates between genders in the daily tasks of: “5 min shower”; “Immersion bath”, “Hand washing”, “Toilet flushes”, “Toilet flushes” and “Car washing”.

However, in daily tasks of washing clothes and dishes by hand or machine there are significant differences based on gender. Male students tend to underestimate their consumption, particularly when it comes to hand washing clothes and dishes.

Fan et al. (2014) also observed a significant difference between ages, but in this study, we only identified a significant difference in estimated water consumption during a 5-minute shower. And in this case, as in Fan et al. study, the youngest underestimate consumption.

Nevertheless, estimating consumption is not an easy task, and

Table 2 shows that different sources present different consumption estimates. The ANQIP [

21]study a also shows a significant variation in consumption, depending on the type of equipment that is installed and the efficiency of the laundry and dishwashing machines.

Average daily water consumption per inhabitant in Portugal

According to Pordata, Portugal's average per capita water consumption in 2021 is 175 L/(inhab.d). However, this number varies by region; Tamega and Sousa have the lowest value at 81 L/(inhab.d), while the Algarve has the highest value on the continent at 319 L/(inhab.d)[

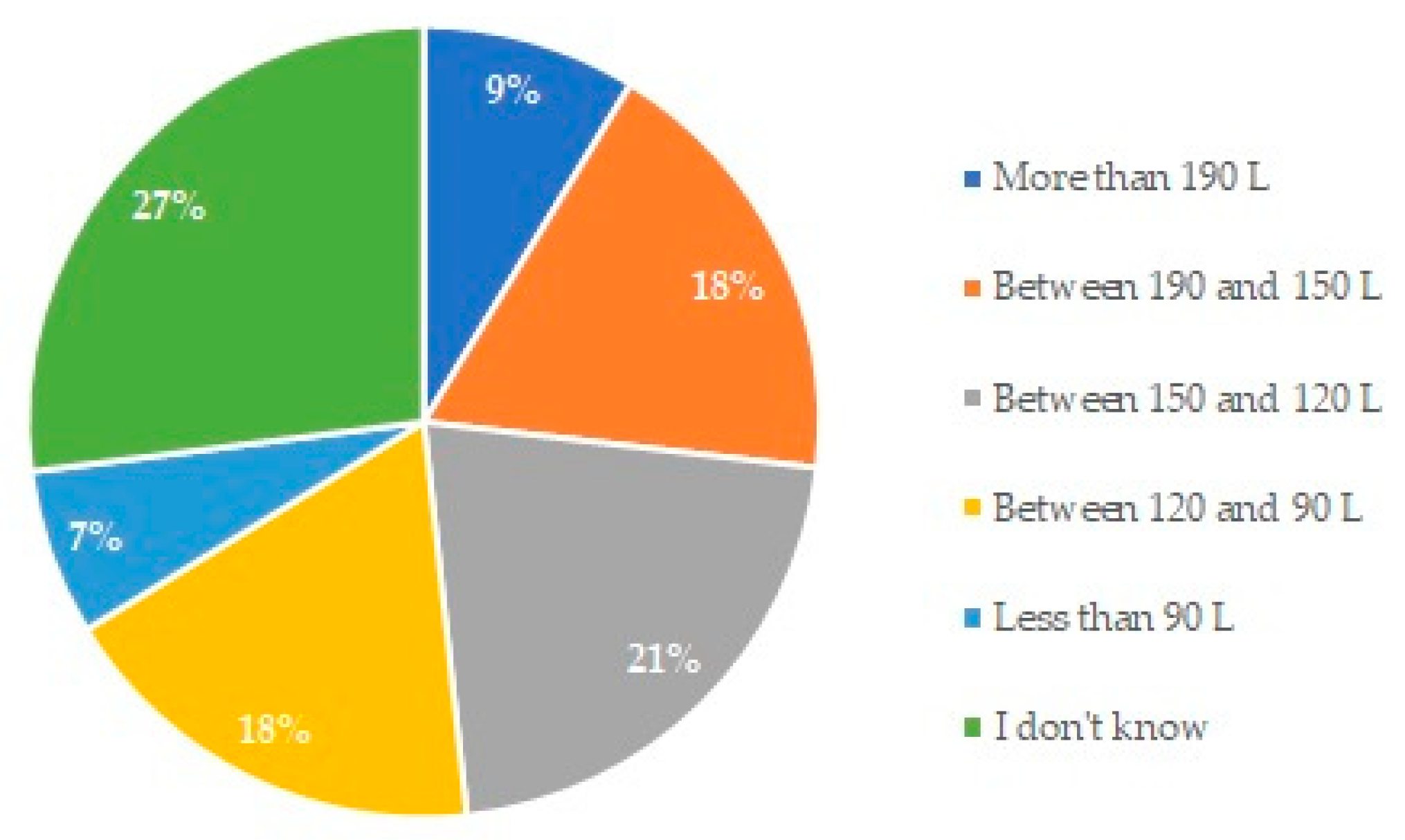

30]. The answers to this question are widely distributed (IQR = 4) on a scale of 1 to 6, with most respondents (27%) selecting "I don't know" (

Figure 5). A mere 18% of the respondents accurately reported the range of 150–190 L/(inhab.d) as the average water consumption per Portuguese resident. Nine percent chose a higher range of values, and the remaining forty-six percent chose ranges with lower values.

Since per capita consumption varies across the nation, it makes sense that there would be significant differences in the distribution of responses by region (K-W test p-values for regions is 0.010).

Overall measures to promote an efficient water management

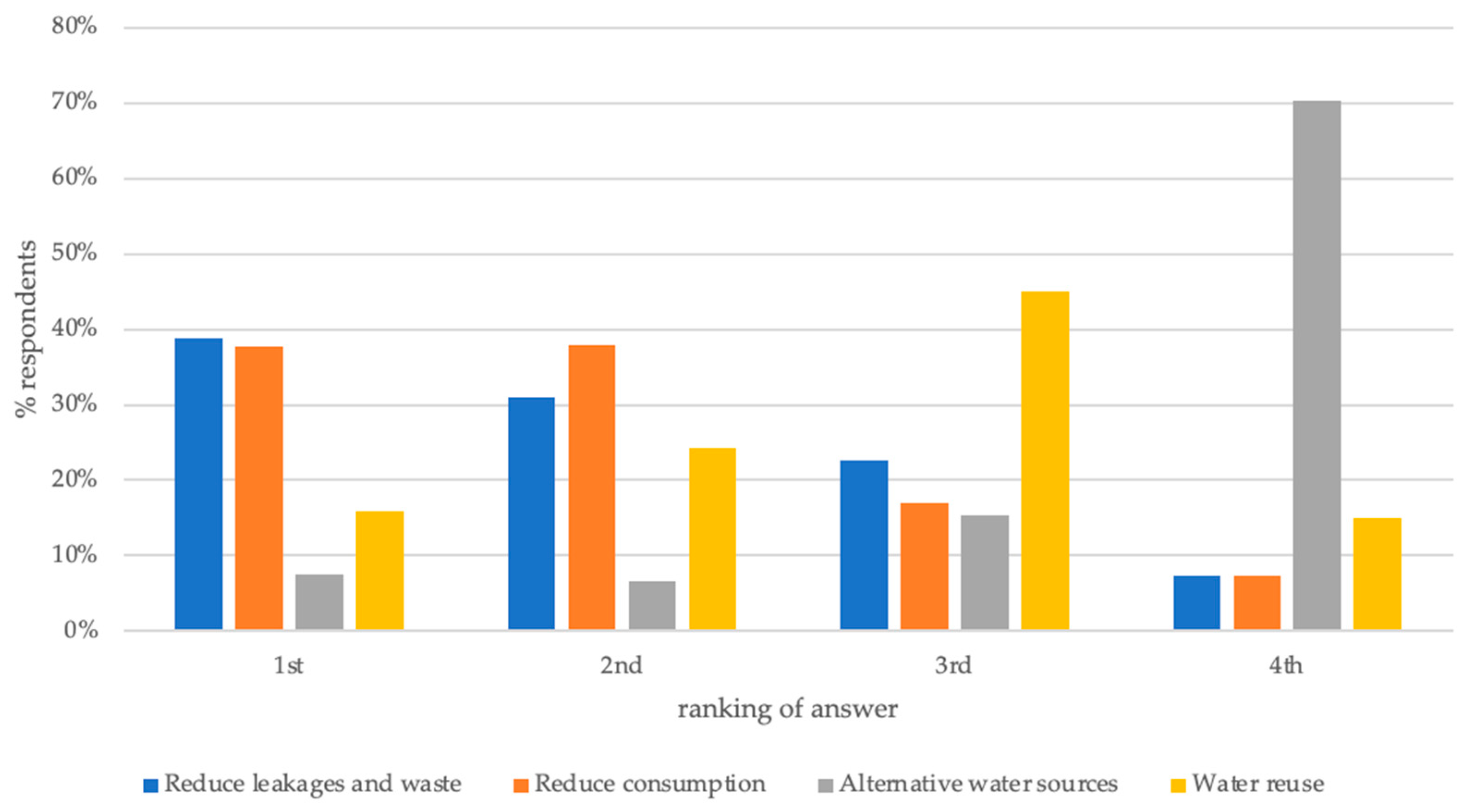

In order to assess the relevance of different management actions that can improve water efficiency, students were asked to rank between 4 overall measures: i) reduce leakages and waste, ii) reduce consumption, iii) use of alternative water sources (other than potable water) and iv) reuse and recycling previously used water.

Figure 6 shows that more than 69% of students identified “Reduce leakages and waste” and “Reduce consumption” as the two main actions to improve water efficiency (ranked 1st or 2nd). “Water reuse and recycling” was ranked 3rd place by 45% of the respondents and the use of “Alternative water sources” was ranked 4th, demonstrating this measure was the least important for the large majority (70%) of the students. Although water reuse from treated wastewater is also considered an alternative water source, the ranking of “alternative water sources” last might be due to lack of knowledge regarding e.g., rainwater collection.

Statistical analysis performed on the measures ranked 1st and 2nd did not reveal significant differences regarding gender, scientific area, region, and age. The only exception was the 1st ranked measure where differences regarding age were statistically significant, mostly due to only a lower percentage of older students selecting “water reuse“ as the 1st ranked alternative (4%, 9% and 6% in 24-26, 27-22 and >33 age groups, respectively) while younger students selected “water resources” 1st in 19% (age group 17-20) and 39% of the answers (age group 21-23).

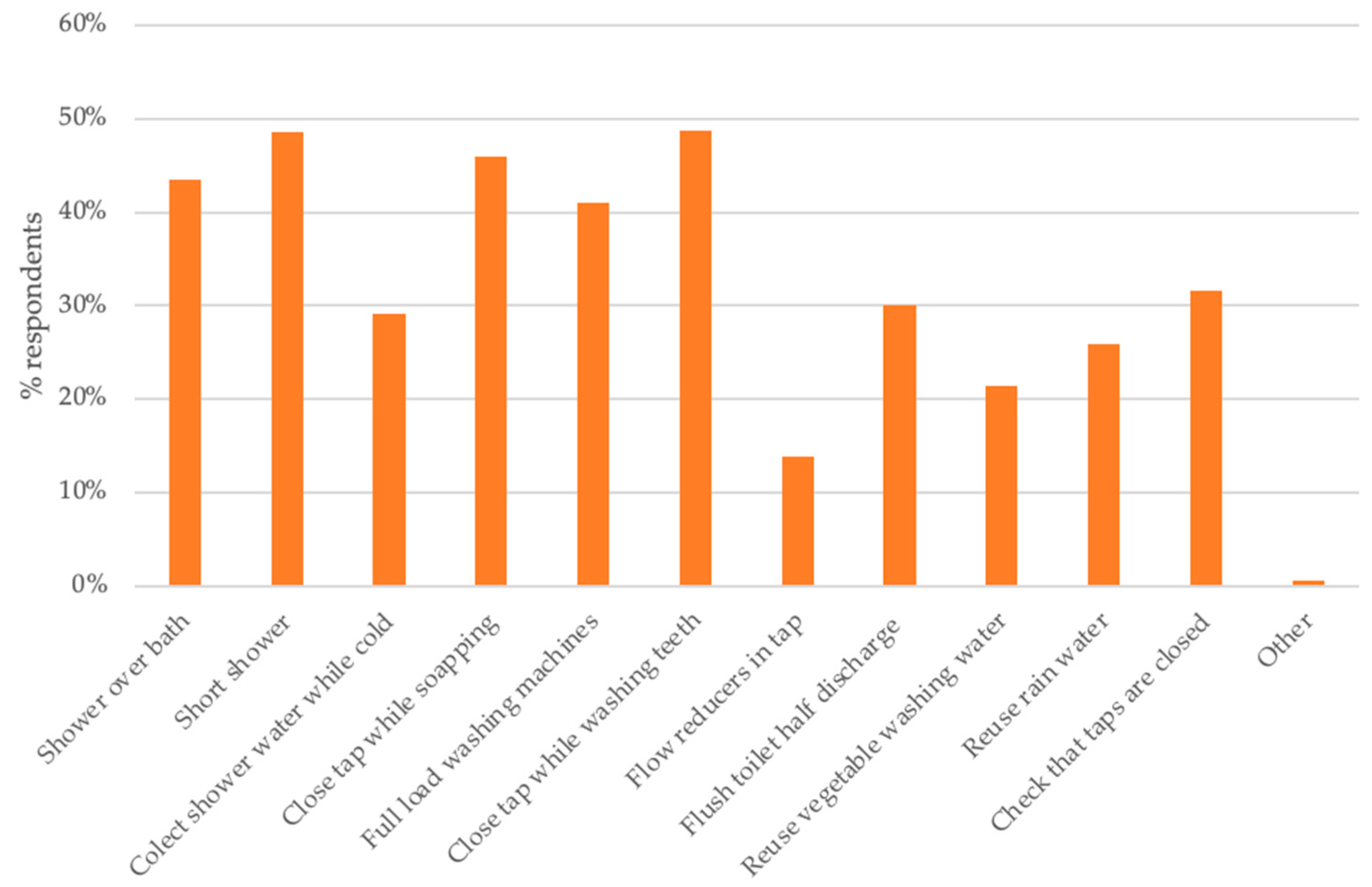

Individual actions to reduce water consumption

When asked to identify daily individual actions considered essential to reduce water consumption, the answers with more selections (between 41% and 49% of the respondents) were “taking a shower over a bath”, “taking a quick shower”, “closing the tap while soaping in the shower”, “using washing machines only when fully charged” and “closing tap while brushing the teeth” (

Figure 7).

In order to reflect the different combinations of answers selected by students, pairs of answers were represented graphically in

Figure 8, where each link represents two answers selected together. The width of each connection describes the number of times each pair was selected (the maximum number represented in red) and the more frequent combinations were pairs among “taking a quick shower”, “closing the tap while soaping in the shower” and “closing the tap while brushing the teeth”. Overall, the most popular actions are related with reducing water consumption, which is in accordance with the priorities selected in the overall measures to promote an efficient water management (previous section).

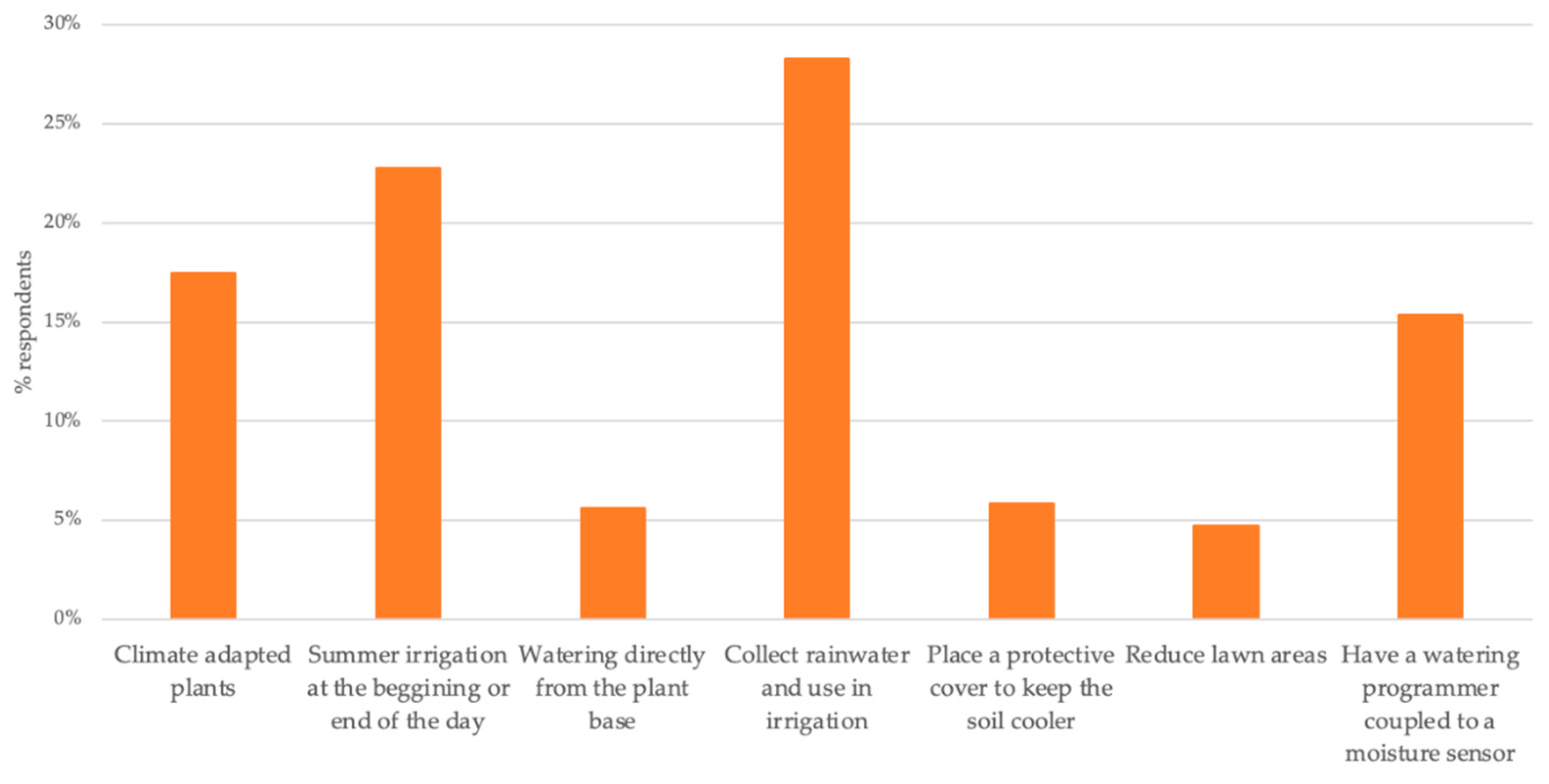

Specific measures regarding irrigation

To assess specific measures regarding the reduction of irrigation in urban areas, students were asked to choose 2 or 3 measures from a list of 7. The action with the highest number of answers (28%) was “to collect rainwater and to use it in irrigation”, followed by “"Summer irrigation at the beginning and end of the day” (23% respondents,

Figure 9). The least popular measures, with less than 10% answers, included: “watering directly from the plant base”, “place a protective cover to keep the soil cooler” and “reduce lawn areas”. This shows that students consider of relevance the use of alternative water sources such as rainwater, and since this was not identified as an overall measure to reduce water consumption, it seems to show students are not aware of what constitute an alternative water source.

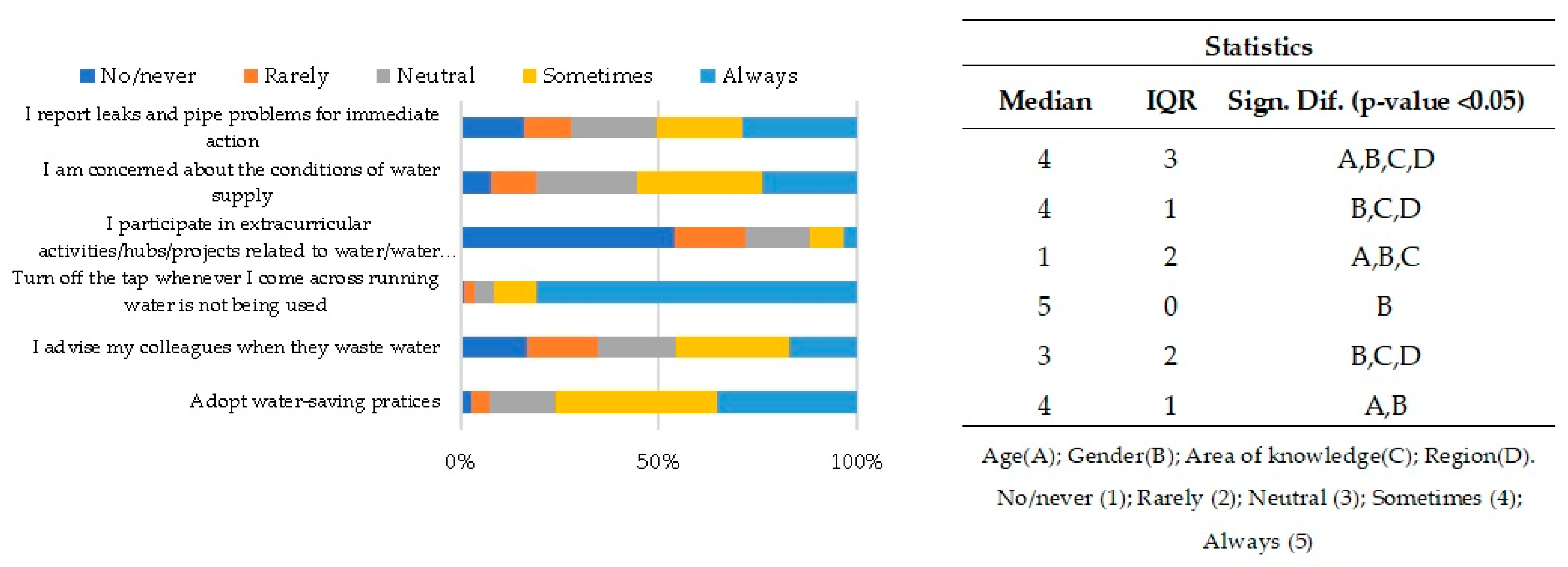

Attitude to avoid water waste in campus

Students' were asked the frequency with which they performed 7 actions aimed at reducing water waste in campus, from reporting water leaks to advising colleagues and adopt water saving measures (

Figure 10). It was observed that students generally care about water loss when they see that a tap has been opened, 80.7% of students choose the “always” option when asked “turn off the tap when it's not in use”. Nevertheless, they don't always follow sensible water-saving habits; only 35.4% of them selected "Always," and the majority of them acknowledge that they do so occasionally or not at all. The results are identical when it comes to water quality concerns and reports of ruptures or damage to installations (

Figure 10).

Nonetheless, they acknowledge that they participate in extracurricular activities that support the sustainable use of water very little or not at all; 54.0% of students say they never do, 3.6% say they do so constantly, and 8.1% say they do so occasionally.

All these attitudes differ significantly by gender, indicating that females have a more participatory attitude, as evidenced by a higher number of "sometimes" and "always" responses than males.

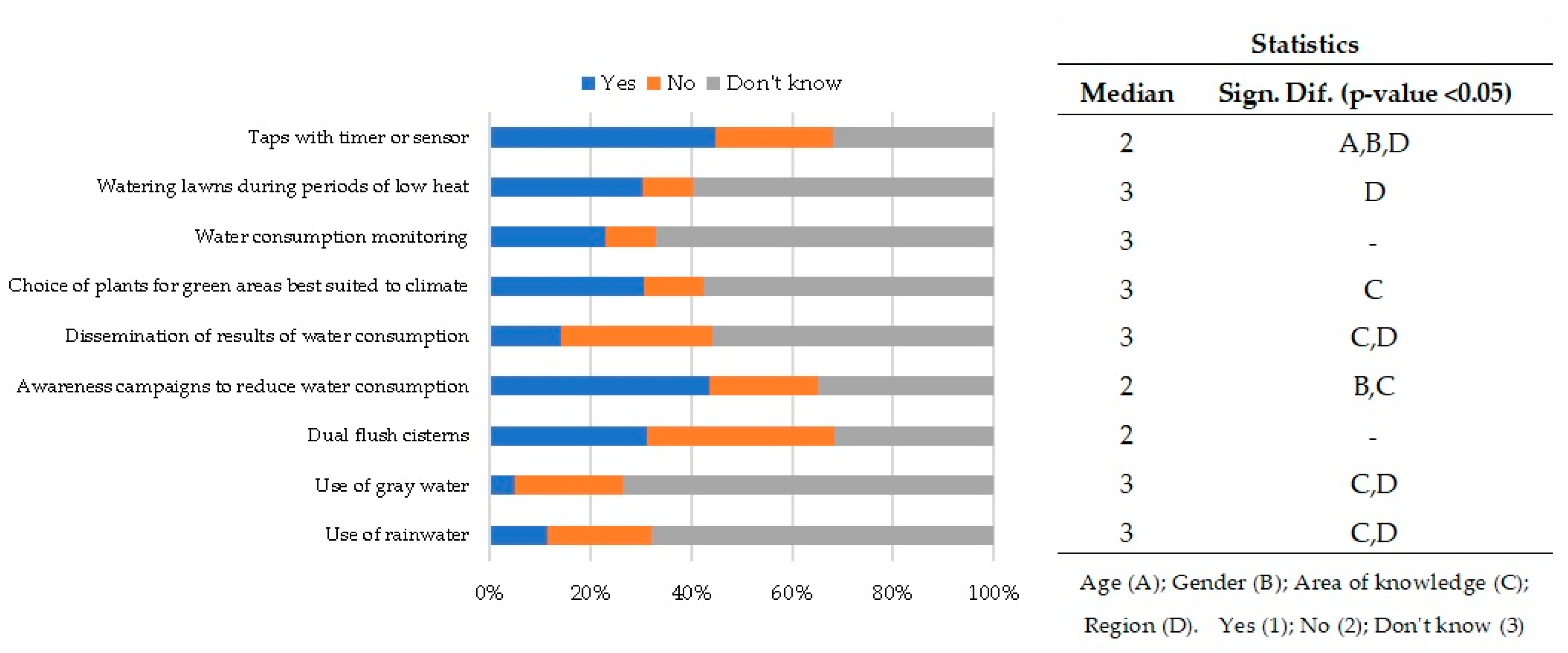

3.4. Water Efficiency Measures in Campus

The knowledge of students regarding their institution’s initiatives in the field of water efficiency (RQ4) was assessed by providing a list of 9 actions to identify whether they were implemented in their institution or not.

The students' response to the measures applied on their campuses reveals a lack of knowledge of what is happening at the HEIs, because in relation to: "making use of rainwater (67.7%)", "making use of grey water (73.5%)", "publicizing the results of water consumption (55.8%)", "choosing plants for green areas that are more suitable for the climate (57.5%)", monitoring water consumption (67.0%), and watering lawns in periods of low heat (59.8%), the option chosen was "don't know". However, 43.7% and 44.8% of respondents answered "yes" to awareness campaigns and the use of taps with a timer or sensor to reduce water consumption, respectively. About dual-flush toilets, 37.3% answered "no".

In terms of the measures applied on the campus where respondents attend, the results show that there were significant differences in the distribution of responses regarding the use of rainwater and grey water by areas of knowledge and Region.

Regarding area of knowledge, the results reveal that about 63% and 75% of respondents from business sciences, and engineering and related areas, respectively, do not know whether rainwater is reused on their campy. Concerning grey water, only 5% of students from Engineering and related areas answered affirmatively.

Regarding the use of dual-flush cisterns, no significant differences were observed, but 68.8% answered “no" and/or don't know" if this measure is applied in their campus, thus revealing a poor knowledge of what is done in the different campi.

There were significant differences in the distribution of responses regarding awareness campaigns to reduce water consumption by gender and areas of knowledge (

Figure 11). Almost half of women (49%), 39% of men and 40% of those who identified themselves as “other”, consider that awareness campaigns are measures applied on their campus. Regarding areas of knowledge, 42.7% of respondents from engineering and related areas, 60.0% from veterinary sciences, and 42.9% from unspecified area, are the ones who consider that awareness campaigns promote the reduction of water consumption, and refer also, these measures are applied on their campus. However, the respondents from business sciences (43.3%) and life sciences (42.9%) do not know if these measures are applied. These results seem to be expected, given that the area of knowledge of engineering and / or related areas includes environmental engineering, where these contents are covered in class, instead of the life sciences students’ contents.

A significant difference was observed in the distribution of responses regarding the dissemination of water consumption results, which includes reports, information campaigns, etc., and the cost associated with the water consumption, by areas of knowledge and Region. Most respondents (55.8%) chose the answer "don't know" and only 14.2% replied “yes”. The exception observed by area of knowledge reports to Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (22.7%) and by region to Madeira (57.1%).

There were significant differences in the distribution of answers regarding the adequacy of chosen plants for green spaces to the specific climate, by area of knowledge, with 57.5% of respondents answering: “don't know”, and 30.8% saying that chosen plants are adequate to the specific climate. The exception observed by area of knowledge reports to Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries area (68.1%) and physical science (60.0%). This result seems to be expected, given that students from these areas of knowledge can identify the type of vegetation (trees and shrubs) planted on their campus.

In relation to monitoring water consumption, no significant differences were observed, despite most of the respondents (77%) answering with “no" and/or don't know" whether this measure is applied in their campus.

There were significant differences in the distribution of responses in relation to watering green spaces during periods of lower heat (beginning and end of the day) by region. Most respondents (59.7%) answered “don't know”, 10% said “no”, and only 30.3% said “yes”. The positive answers were mostly from the Algarve region (53.8%) and from Madeira (71.4%).

The results show that most respondents identify the use of taps with a timer or sensor as a measure applied on their campus (44.8%), but 23.2% and 32.0% said “no”, and “don't know” respectively. A significant difference was observed in the distribution of responses by: (a) age group: 50.4% (<23 year old) and 37% (above 23 year old) are aware of this measure; (b) gender: with female respondents being the mostly aware (48.8%), male respondents with only 41.0% of positive answers and with a large percentage of recognized unawareness (71.4%) from the respondents without chosen gender; (c) by area of knowledge: the majority (45.9%) of respondents, consider that this measure is applied, 31.5% “don't know”, and 23.5% said that this measure is not applied; (d) by Region, circa 46% of respondents from Alentejo and from Central region, and circa 61% of respondents from Algarve and from the Metropolitan area of Lisbon, consider that this measure is applied, but 84% of respondents from Azores and from Madeira consider that this measure is not applied on their campus. Generally, it can be concluded that young students, female students, and students from the Metropolitan area of Lisbon are more sensitive concerning the uses of taps with a timer or sensor.

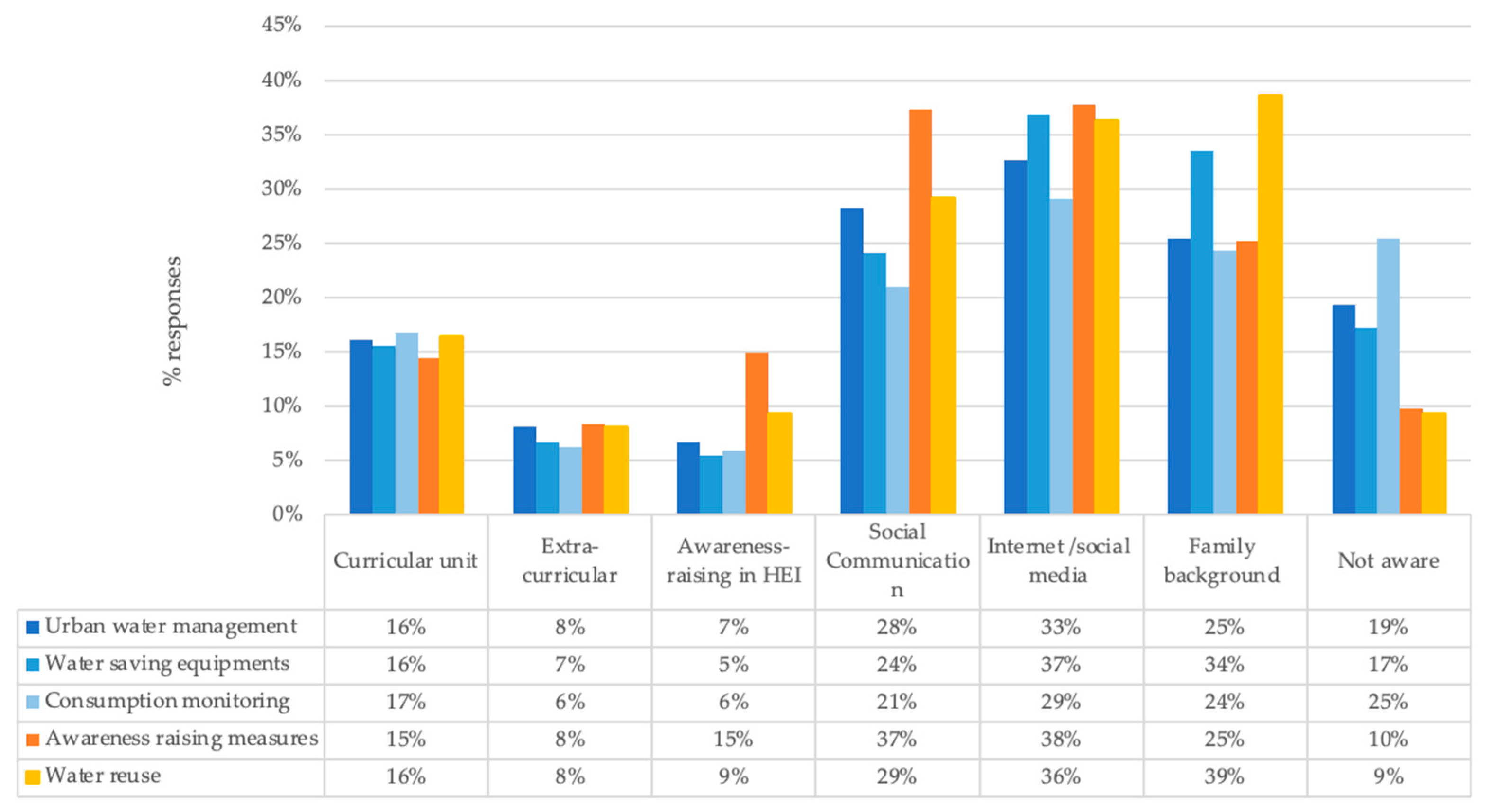

3.5. Learning Water Efficiency Measures

In order to assess what are the sources of knowledge regarding water management and water efficiency concepts (RQ5) students were asked to identify the sources of knowledge among a list of 6 options: curricular units (subjects within courses), extra-curricular units, awareness-raising information in HEI, Social communication, Internet/social media and family background. The knowledge topics considered included “urban water management measures”, “water saving equipment”, “water consumption monitoring methodologies”, “awareness raising measures” and "water reuse” (

Figure 12).

The main information sources identified by the students for all topics were “social communication” and “internet/social media”, which combined accounted for 61% of the students for all topics except for “consumption monitoring” where the same combined sources accounted only for 50% of the student’s answers. “Family background” was the third most selected source, which assumed special relevance regarding “water reuse”, selected by 39% of the students. Regarding the sources within HEIs, curricular units were reported by around 15% of the students as sources for all topics, and extra-curricular activities and awareness raising measures in HEI were identified as sources of information for less than 10% of the students. A particular note must be made regarding awareness raising measures within HEI, which were only selected by 15% of the students, revealing that HEIs might not be too committed to implementing water efficiency in their own campus, or are not communicating effectively when doing so.

3.6. Water Efficiency in Future Employment

The assessment of students’ reactions regarding water efficiency issues in future employment and willingness to act (RQ6) was performed by asking if they would accept a salary 5% below average to work for a company in two situations: i) a position where they could make a positive contribution to water efficiency and ii) a company certified with good water management practices.

The results show that 46.2% of the total sample would opt for a job in a position that would allow respondents to make a positive contribution to water efficiency (

Table 3).

The results also show that concerning the possibility of accepting a job offer in a position that would allow respondents to make a positive contribution to water efficiency, there are significant differences in the distribution of responses by age group and gender, while in the areas of knowledge and region, no significant differences were observed.

The results also reveal that young students (< 20 years old) are more sensitive (56%, n= 239), showing a greater willingness to accept a job offer with equal benefits, with a salary 5% below average, provided there was a positive contribution to water efficiency. Respondents in the remaining age groups (> 21 years old) would not choose to be offered a job in a position that would allow them to make a positive contribution to water efficiency. This can be explained by the need to find a job or to assert themselves in the labor market.

On the other hand, regarding gender, women seem to be more sensitive (50.9%) as they chose to accept if the company was certified with good water efficiency practices, while men (59.3%) would not choose to accept if the company was certified with good water efficiency practices.

In relation to the students' future employment, similar results were found by Aleixo et al. [

3] about the students' interest in working in a Sustainable Development (SD) company, with the youngest age group (17 - 19 years) preferring to work in this type of company, even if the salary is lower than average.

51.6 % of the total respondents selected “yes” for the possibility of employment in a company certified with good water efficiency practices (

Table 3). There are significant differences in the distribution of responses by gender and region. Female respondents (60.2%) and other gender (60.0%) are more sensitive than Male respondents (42.6%). The significant differences observed by region show that respondents from Alentejo (50.7%), Centre (56.6%) and Azores (66.7%) would not primarily opt for employment in a company certified with good water efficiency practices. This could be explained by a lower development of these regions, with lower access to well paid jobs. The respondents of remaining regions, (52.9%) would opt for a job in a company certified with good water efficiency practices.

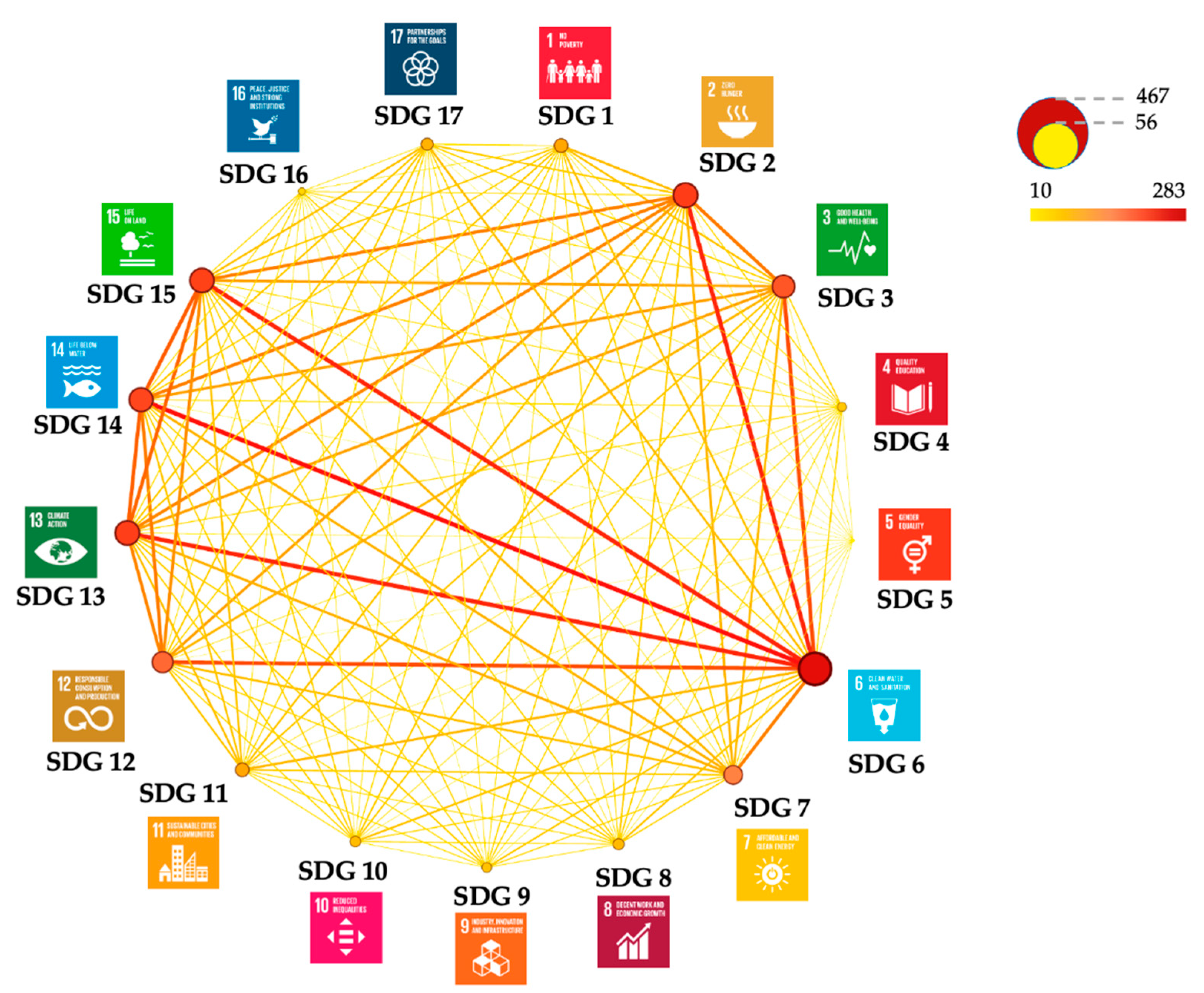

3.7. Water Efficiency and the SDG

The perceived connection between water efficiency and Sustainable Development Goals (RQ7) was assessed by asking their opinion regarding the contribution of water efficiency to the 17 SDGs, allowing students to select between 3 and 10 options. As results, 25% selected 3 options, 32% selected 4 to 6 options, 28% selected 7 to 9 options and 15% of the students selected 10 options. The combination (pairs) of answers between the options selected by each respondent was graphically represented in

Figure 13. The size and color of each SDG node represents the number of times each SDG was selected, and the width of each connection describes the number of times each pair was selected. As expected, SDG 6 – clean water and sanitation was the most selected SDG, with 467 answers representing 70% of the students. SDG 2 – Zero Hunger, SDG13 – climate action, SDG 14 - Life below water and SDG15 – life on land had similar selection rates between 51% to 53%.

Regarding the combinations within the selected SDG in each answer, SDG 6 was mostly selected together with SDGs 2, 3, 12, 13, 14 and 15, but 12, 13, 14 and 15 were also selected together. These combinations suggest that students associate water efficiency in human activities to all SDGs directly related with water (SDG 6, 14 and 15) but also to human basic activities that can be affected by water (SDG 2) and climate change (SDG 13). Considering that UNWater clearly states that “Climate change is primarily a water crisis”[

31] it can be concluded that the majority of the surveyed students are aware of this connection.

5. Conclusions

A survey was conducted in seven Portuguese higher education institutions aimed at understanding students’ literacy on sustainable use of potable water. Results revealed that students recognize the importance of water and are concerned about current water resources issues, with older students, women, and science students demonstrating greater awareness. There are variable perceptions and awareness regarding different issues, from water prices to foreseen changes in river flows and drought frequency, depending on gender and age. These findings inform targeted interventions for sustainable water management and ecosystem preservation.

Students demonstrate awareness of their water use habits, categorizing them as “average”. However, they tend to underestimate their real consumption when asked to quantify it. Male students particularly underestimate the use of water for tasks such as washing clothes and dishes by hand. There is a notable lack of knowledge about per capita water consumption, with significant regional variations in estimated values.

Students prioritized reducing water consumption to improve water efficiency, with new water sources ranking last in their preferences. Future policies should incorporate awareness campaigns and provide information on using reclaimed water to enhance public acceptance. They recognize the importance of water conservation on campus but admit inconsistent adherence, with women demonstrating more care and participation than men. It can also be concluded that young female students and respondents from the Lisbon Metropolitan area are more sensitive to water efficiency measures, such as taps with timers or sensors.

The main sources of information on water efficiency identified by students were “social communication” and “internet/social networks”, but “family background” was also relevant. This highlights the relevance of transmitting accurate information through these channels, and the importance of the intergenerational transmission of knowledge and reveals that the transfer of knowledge about water efficiency in higher education can be improved.

Regarding students' responses to future employment, although younger students and women are more inclined to accept positions in companies certified for good water efficiency practices, even with lower salaries, there is no clear preference for either salary or environment. In spite of economic concerns, leading students to prioritize salary, these results are nevertheless representative of an increasing willingness to act.

Finally, most students are aware of the link between water efficiency and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), especially SDG6 - Clean Water and Sanitation. They also recognize the relevance and connections to other SDGs, namely SDG 2 – Zero Hunger, SDG13 – Climate Action, SDG 14 – Life Below Water and SDG15 – Life on Earth.

The authors believe these insights can now guide future actions by Higher Education Institutions to improve their training programs, initiatives, and practices on campuses, towards sustainable water management and the SDGs.

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. The following statements should be used “Conceptualization, AD, AMB, AG, CM, DM, IA, LN and SM; methodology, AD, AMB, AG, CM, DM, IA, LN and SM; formal analysis, AD, AMB, AG and SM; writing—original draft preparation, AD, AMB, AG, CM, DM, IA and SM; writing—review and editing, AD, AMB, AG, CM, DM, IA, LN and SM. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”