Submitted:

09 May 2024

Posted:

10 May 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction and Background

- How effectively do the cybersecurity policy documents of LGs align with the Functions and Categories of the NIST CSF 2.0?

- What are the key components that should be included in a cybersecurity policy document by LGs to ensure its effectiveness and comprehensiveness?

2. The NIST CSF 2.0

3. Methodology

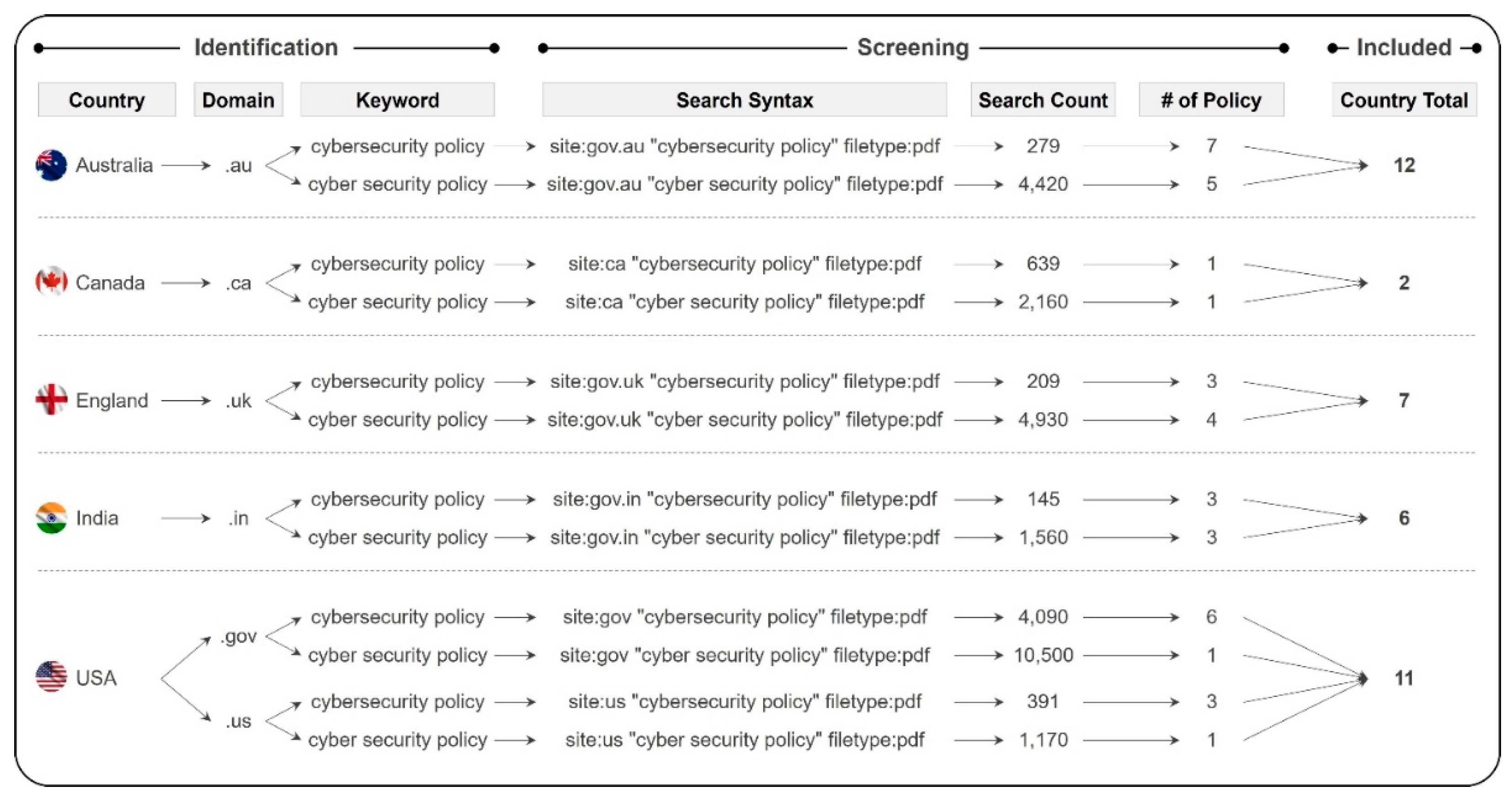

3.1. Policy Documents

3.2. Research Strategy

4. Results and Analysis

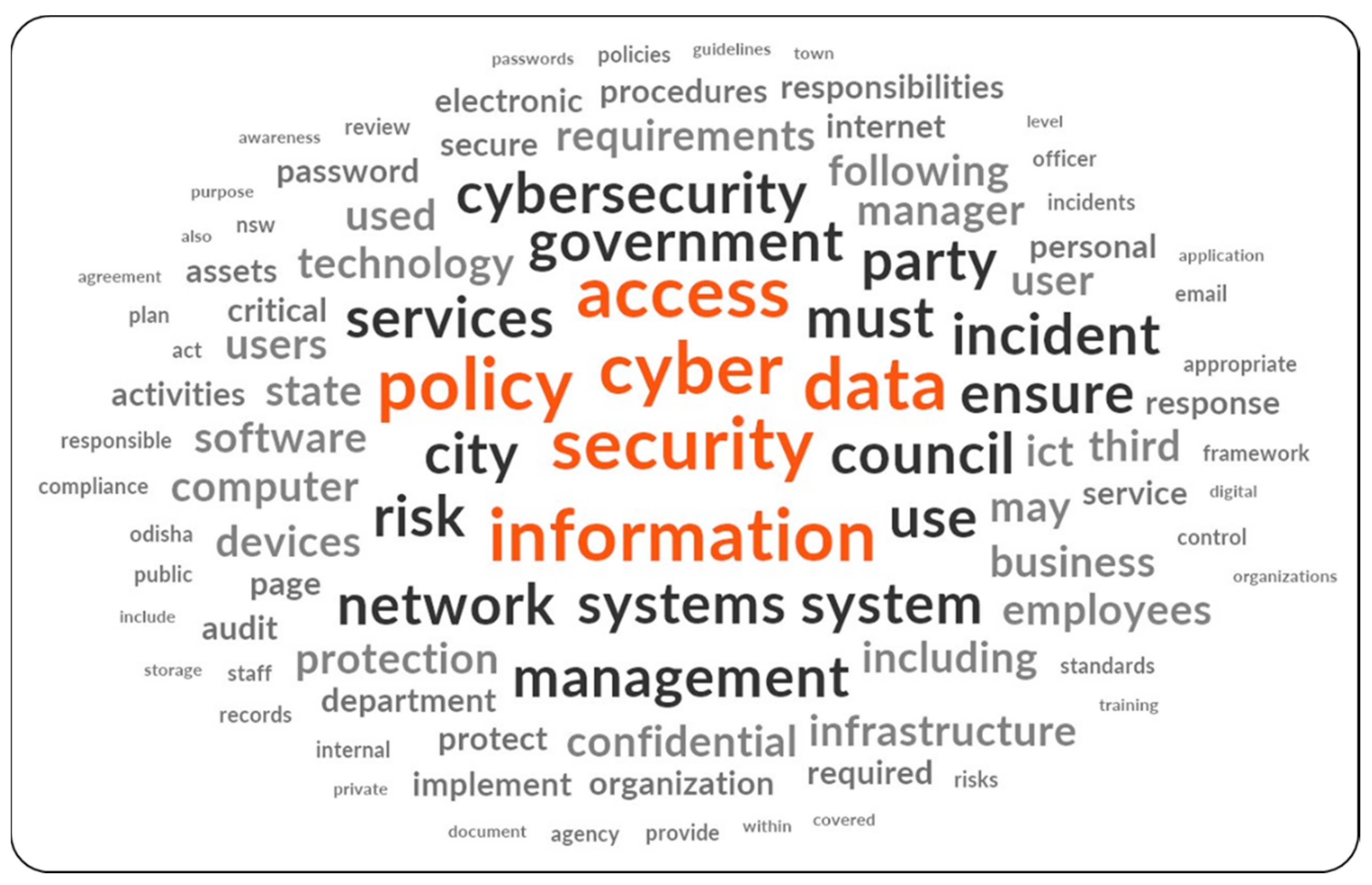

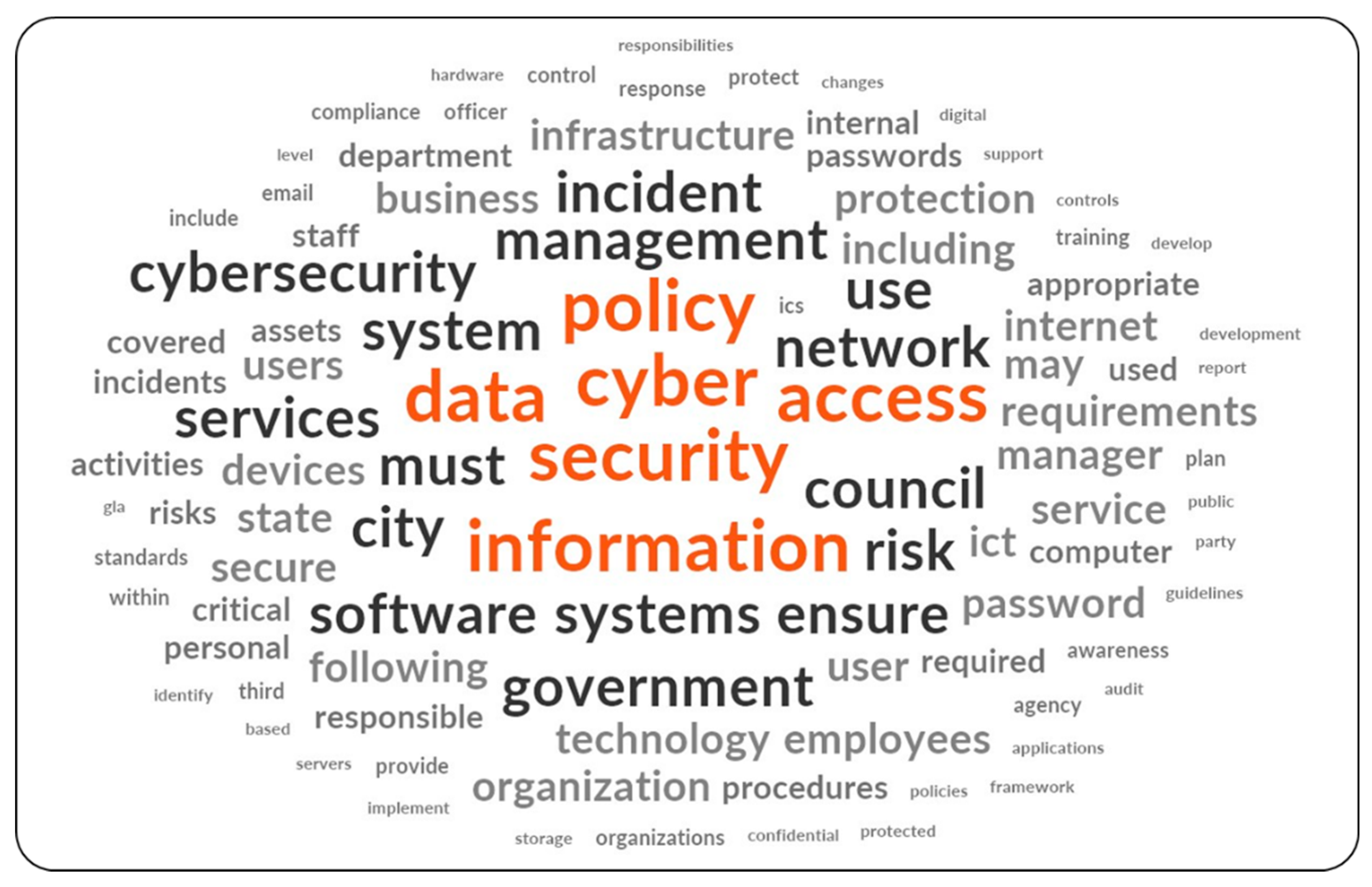

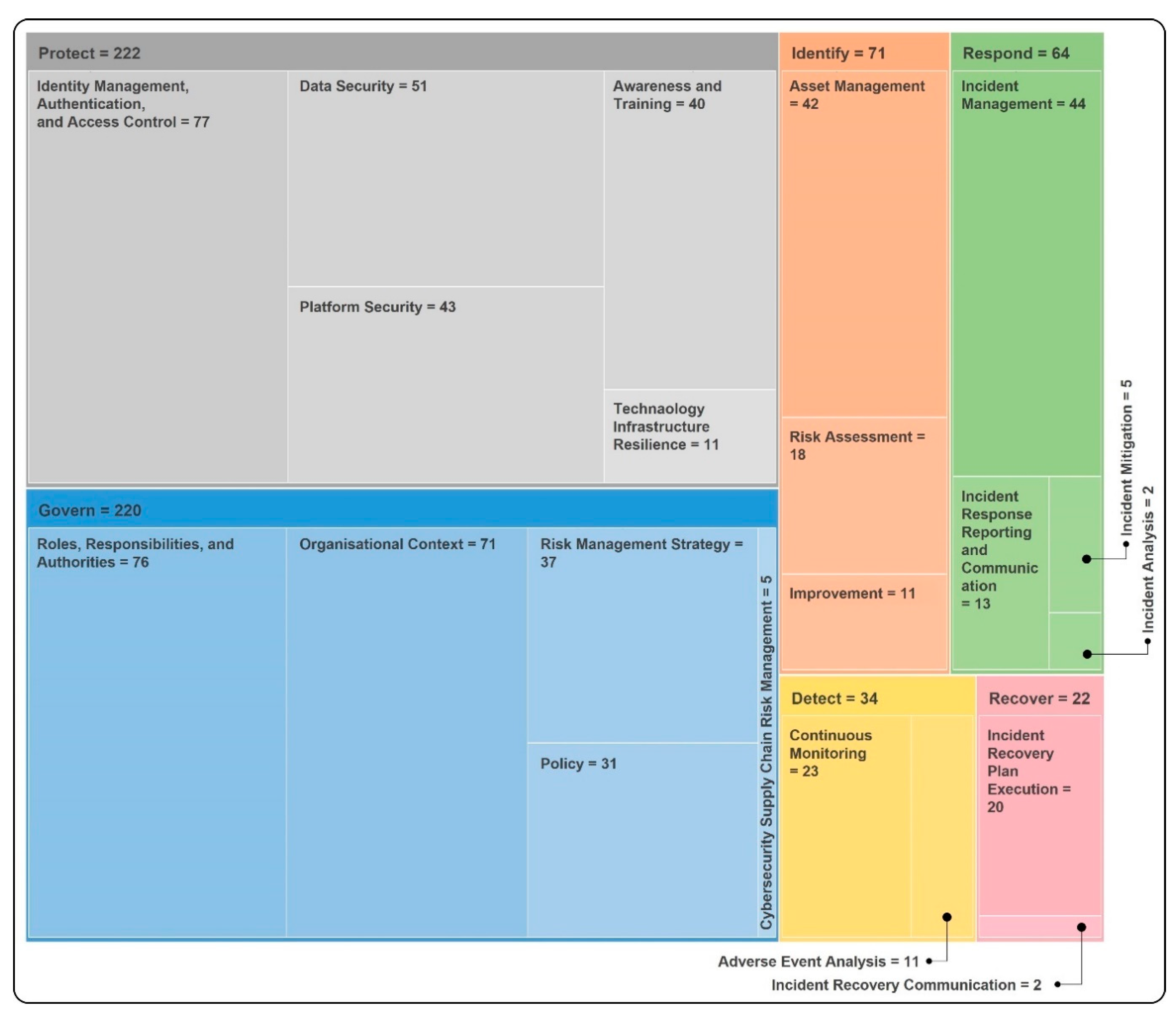

4.1. Quantitative Content Analysis

4.2. Qualitative Content Analysis

4.2.1. ‘Govern’ with Focus on Organisational Risk and Responsibility

4.2.2. ‘Identify’ with Focus on Asset and Risk Management

4.2.3. ‘Protect’ with Focus on Access Control, and Raising Awareness

4.2.4. ‘Detect’ with Focus on Continuous Monitoring

4.2.5. ‘Respond’ with Focus on Incident Management

4.2.6. ‘Recover’ with Focus on Incident Recovery Plan Execution

5. Findings and Discussion

5.1. Insights from Cybersecurity Policies of LGs

5.2. Key Contributing Factors to Existing Gaps in the Cybersecurity Policies

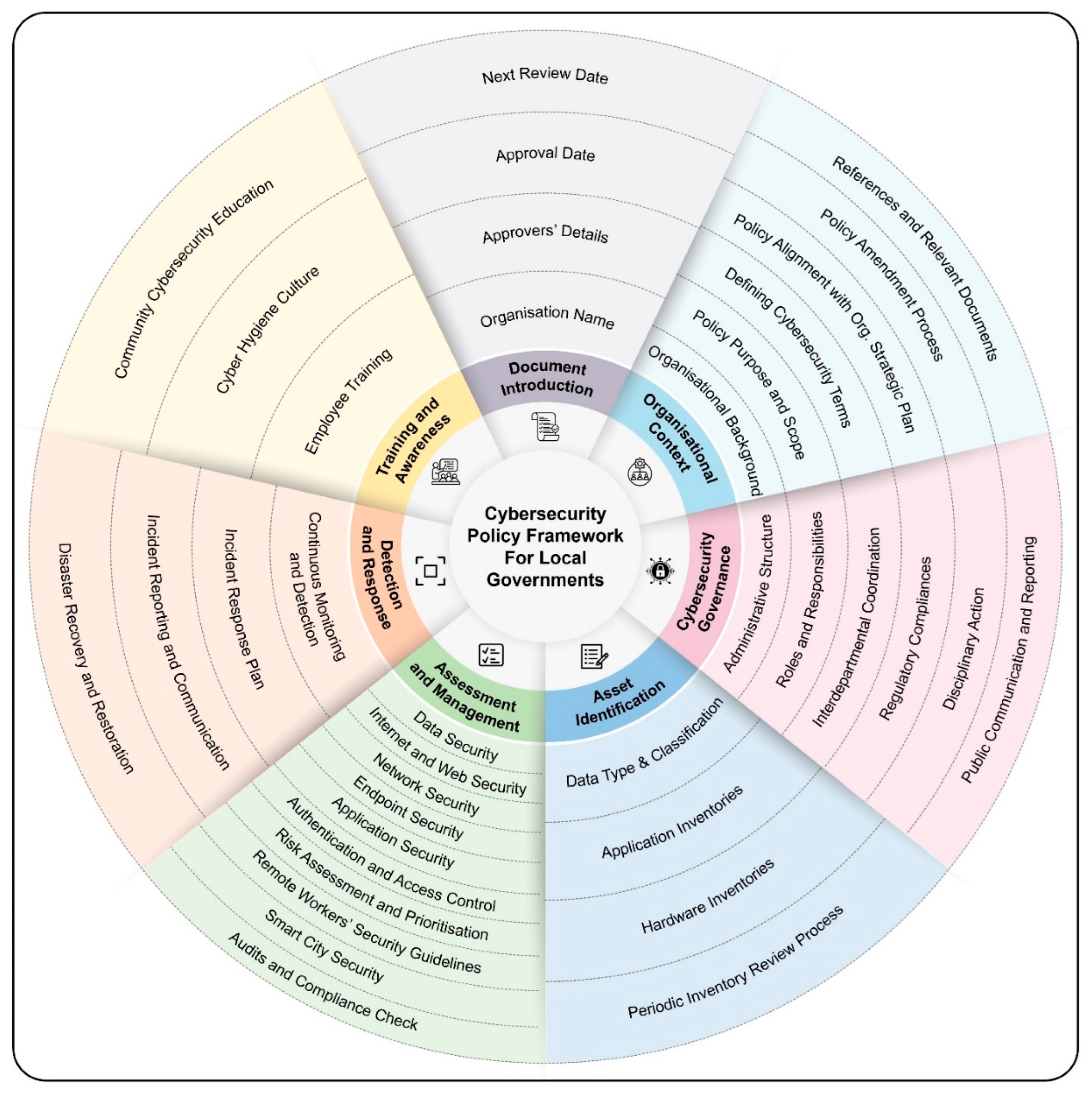

5.3. Cybersecurity Policy Framework for LGs

6. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ahmadi-Assalemi, G., Al-Khateeb, H., Epiphaniou, G., & Maple, C. (2020). Cyber resilience and incident response in smart cities: A systematic literature review. Smart Cities, 3(3), 894-927. [CrossRef]

- AlDaajeh, S., Saleous, H., Alrabaee, S., Barka, E., Breitinger, F., & Raymond Choo, K.-K. (2022). The role of national cybersecurity strategies on the improvement of cybersecurity education. Computers & Security, 119, 102754. [CrossRef]

- Ali, O., Shrestha, A., Chatfield, A., & Murray, P. (2020). Assessing information security risks in the cloud: A case study of Australian local government authorities. Government Information Quarterly, 37(1), 101419. [CrossRef]

- Ariffin, K. A. Z., & Ahmad, F. H. (2021). Indicators for maturity and readiness for digital forensic investigation in era of industrial revolution 4.0. Computers & Security, 105, 102237. [CrossRef]

- Bauer, J. M., & van Eeten, M. J. G. (2009). Cybersecurity: Stakeholder incentives, externalities, and policy options. Telecommunications Policy, 33(10), 706-719. [CrossRef]

- Beaverton. (2021). Cybersecurity policy. City of Beaverton, Oregon, USA Retrieved from https://content.civicplus.com/api/assets/fda4939f-c8e3-4228-85b8-87d31ae22c6d.

- Boyson, S. (2014). Cyber supply chain risk management: Revolutionizing the strategic control of critical IT systems. Technovation, 34(7), 342-353. [CrossRef]

- Caruson, K., MacManus, S. A., & McPhee, B. D. (2012). Cybersecurity policy-making at the local government level: An analysis of threats, preparedness, and bureaucratic roadblocks to success. Journal of Homeland Security and Emergency Management, 9(2). [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, S., Gkioulos, V., & Katsikas, S. (2023). A quest for research and knowledge gaps in cybersecurity awareness for small and medium-sized enterprises. Computer Science Review, 50, 100592. [CrossRef]

- Chaudhuri, A., & Bozkus Kahyaoglu, S. (2023). Cybersecurity assurance in smart cities: A risk management perspective. EDPACS, 67(4), 1-22. [CrossRef]

- D’Amico, G., L’Abbate, P., Liao, W., Yigitcanlar, T., & Ioppolo, G. (2020). Understanding sensor cities: Insights from technology giant company driven smart urbanism practices. Sensors, 20(16), 4391. [CrossRef]

- David, A., Yigitcanlar, T., Li, R. Y. M., Corchado, J. M., Cheong, P. H., Mossberger, K., & Mehmood, R. (2023). Understanding local government digital technology adoption strategies: A PRISMA review. Sustainability, 15(12), 9645. https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/15/12/9645.

- Fielder, A., König, S., Panaousis, E., Schauer, S., & Rass, S. (2018). Risk assessment uncertainties in cybersecurity investments. Games, 9(2), 34. https://www.mdpi.com/2073-4336/9/2/34.

- Frandell, A., & Feeney, M. (2022). Cybersecurity threats in local government: A sociotechnical perspective. The American Review of Public Administration, 52(8), 558-572. [CrossRef]

- Goel, R., Kumar, A., & Haddow, J. (2020). PRISM: A strategic decision framework for cybersecurity risk assessment. Information & Computer Security, 28(4), 591-625. [CrossRef]

- Grobler, M., Gaire, R., & Nepal, S. (2021). User, usage and usability: Redefining human centric cyber security. Frontiers in Big Data, 4. [CrossRef]

- Habibzadeh, H., Nussbaum, B. H., Anjomshoa, F., Kantarci, B., & Soyata, T. (2019). A survey on cybersecurity, data privacy, and policy issues in cyber-physical system deployments in smart cities. Sustainable Cities and Society, 50, 101660. [CrossRef]

- Hamdani, S. W. A., Abbas, H., Janjua, A. R., Shahid, W. B., Amjad, M. F., Malik, J., Murtaza, M. H., Atiquzzaman, M., & Khan, A. W. (2021). Cybersecurity standards in the context of operating system: Practical aspects, analysis, and comparisons. ACM Comput. Surv., 54(3), Article 57. [CrossRef]

- Harknett, R. J., & Stever, J. A. (2011). The new policy world of cybersecurity. Public Administration Review, 71(3), 455-460. [CrossRef]

- Hatcher, W., Meares, W. L., & Heslen, J. (2020). The cybersecurity of municipalities in the United States: An exploratory survey of policies and practices. Journal of Cyber Policy, 5(2), 302-325. [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, A., Valli, C., McAteer, I., & Chaudhry, J. (2018). A security review of local government using NIST CSF: A case study. The Journal of Supercomputing, 74(10), 5171-5186. [CrossRef]

- Javed, A. R., Shahzad, F., Rehman, S. u., Zikria, Y. B., Razzak, I., Jalil, Z., & Xu, G. (2022). Future smart cities: Requirements, emerging technologies, applications, challenges, and future aspects. Cities, 129, 103794. [CrossRef]

- Kalinin, M., Krundyshev, V., & Zegzhda, P. (2021). Cybersecurity risk assessment in smart city infrastructures. Machines, 9(4), Article 78. [CrossRef]

- Li, L., He, W., Xu, L., Ash, I., Anwar, M., & Yuan, X. (2019). Investigating the impact of cybersecurity policy awareness on employees’ cybersecurity behavior. International Journal of Information Management, 45, 13-24. [CrossRef]

- Ma, C. (2021). Smart city and cyber-security; technologies used, leading challenges and future recommendations. Energy Reports, 7, 7999-8012. [CrossRef]

- MacManus, S. A., Caruson, K., & McPhee, B. D. (2013). Cybersecurity at the local government level: Balancing demands for transparency and privacy rights. Journal of Urban Affairs, 35(4), 451-470. [CrossRef]

- Madras. (2020). Cybersecurity policy. City of Madras, Oregon, USA Retrieved from https://www.ci.madras.or.us/sites/default/files/fileattachments/city_council/page/98/g-council_policies-approved_4-27-2021.pdf.

- Micozzi, N., & Yigitcanlar, T. (2022). Understanding smart city policy: Insights from the strategy documents of 52 local governments. Sustainability, 14(16), 10164. [CrossRef]

- Mishra, A., Alzoubi, Y. I., Anwar, M. J., & Gill, A. Q. (2022). Attributes impacting cybersecurity policy development: An evidence from seven nations. Computers & Security, 120, 102820. [CrossRef]

- Möller, D. P. F. (2023). NIST cybersecurity framework and MITRE cybersecurity criteria. In D. P. F. Möller (Ed.), Guide to Cybersecurity in Digital Transformation: Trends, Methods, Technologies, Applications and Best Practices (pp. 231-271). Springer Nature Switzerland. [CrossRef]

- Morrissey, A., Aslam, K., Goodwin, B., Vikas, R., & Langford-Smith, J. (2021). Cyber security in local government. https://audit.wa.gov.au/reports-and-publications/reports/cyber-security-in-local-government/.

- NIST. (2023). The NIST cybersecurity framework 2.0 - initial public draft. USA: National Institute of Standards and Technology, US Department of Commerce.

- NIST. (2024a). NIST cybersecurity framework 2.0: Resource & overview guide. USA: National Institute of Standards and Technology, US Department of Commerce.

- NIST. (2024b). NIST cybersecurity framework (CSF) 2.0. USA: National Institute of Standards and Technology, US Department of Commerce.

- Norris, D. F., Mateczun, L., Joshi, A., & Finin, T. (2018). Cybersecurity at the grassroots: American local governments and the challenges of internet security. Journal of Homeland Security and Emergency Management, 15(3), Article 20170048. [CrossRef]

- Norris, D. F., Mateczun, L., Joshi, A., & Finin, T. (2019). Cyberattacks at the grass roots: American local governments and the need for high levels of cybersecurity. Public Administration Review, 79(6), 895-904. [CrossRef]

- Norris, D. F., Mateczun, L., Joshi, A., & Finin, T. (2021). Managing cybersecurity at the grassroots: Evidence from the first nationwide survey of local government cybersecurity. Journal of Urban Affairs, 43(8), 1173-1195. [CrossRef]

- Norris, D. F., & Mateczun, L. K. (2022). Cyberattacks on local governments 2020: Findings from a key informant survey. Journal of Cyber Policy, 7(3), 294-317. [CrossRef]

- Norwich. (2020). Cybersecurity policy. Town of Norwich, New York, USA Retrieved from http://norwich.vt.us/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/SB-packet-03-25-20.pdf.

- Nuñez, M., Palmer, X. L., Potter, L., Aliac, C. J., & Velasco, L. C. (2023). ICT security tools and techniques among higher education institutions: A critical review. International Journal of Emerging Technologies in Learning, 18(15), 4-22. [CrossRef]

- Öğüt, H., Raghunathan, S., & Menon, N. (2011). Cyber security risk management: Public policy implications of correlated risk, imperfect ability to prove loss, and observability of self-protection. Risk Analysis, 31(3), 497-512. [CrossRef]

- Patterson, C. M., Nurse, J. R. C., & Franqueira, V. N. L. (2023). Learning from cyber security incidents: A systematic review and future research agenda. Computers & Security, 132, 103309. [CrossRef]

- Popescul, D., & Radu, L. D. (2016). Data security in smart cities: Challenges and solutions. Informatica Economica, 20(1), 29-38. [CrossRef]

- Portland. (2023). A resolution authorizing the city of Portland to enact a critical infrastructure cyber security policy. City of Portland, Tennessee, USA Retrieved from https://www.cityofportlandtn.gov/AgendaCenter/ViewFile/Item/865?fileID=2178.

- Preis, B., & Susskind, L. (2022). Municipal cybersecurity: More work needs to be done. Urban Affairs Review, 58(2), 614-629. [CrossRef]

- RBWM. (2020). Cyber security policy. Royal Borough Windsor & Maidenhead, South East England, UK Retrieved from https://www.rbwm.gov.uk/sites/default/files/2020-10/info_sec_cyber_security_policy.pdf.

- Repette, P., Sabatini-Marques, J., Yigitcanlar, T., Sell, D., & Costa, E. (2021). The evolution of city-as-a-platform: Smart urban development governance with collective knowledge-based platform urbanism. Land, 10(1), 33. [CrossRef]

- Sadik, S., Ahmed, M., Sikos, L. F., & Najmul Islam, A. K. M. (2020). Toward a sustainable cybersecurity ecosystem. Computers, 9(3), 1-17, Article 74. [CrossRef]

- Sarker, I. H., Furhad, M. H., & Nowrozy, R. (2021). AI-driven cybersecurity: An overview, security intelligence modeling and research directions. SN Computer Science, 2(3), 173. [CrossRef]

- Savaş, S., & Karataş, S. (2022). Cyber governance studies in ensuring cybersecurity: An overview of cybersecurity governance. International Cybersecurity Law Review, 3(1), 7-34. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, K., & Mukhopadhyay, A. (2022). Sarima-based cyber-risk assessment and mitigation model for a smart city’s traffic management systems (SCRAM). Journal of Organizational Computing and Electronic Commerce, 32(1), 1-20. [CrossRef]

- Siudak, R. (2022). Cybersecurity discourses and their policy implications. Journal of Cyber Policy, 7(3), 318-335. [CrossRef]

- Son, T. H., Weedon, Z., Yigitcanlar, T., Sanchez, T., Corchado, J. M., & Mehmood, R. (2023). Algorithmic urban planning for smart and sustainable development: Systematic review of the literature. Sustainable Cities and Society, 104562. [CrossRef]

- Srinivas, J., Das, A. K., & Kumar, N. (2019). Government regulations in cyber security: Framework, standards and recommendations. Future Generation Computer Systems, 92, 178-188. [CrossRef]

- Sun, N., Zhang, J., Rimba, P., Gao, S., Zhang, L. Y., & Xiang, Y. (2019). Data-diven cybersecurity incident prediction: A survey. IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials, 21(2), 1744-1772. [CrossRef]

- Syafrizal, M., Selamat, S., & Zakaria, N. (2020). Analysis of sybersecurity standard and framework components. International Journal of Communication Networks and Information Security, 12, 417-432. [CrossRef]

- Taherdoost, H. (2022). Understanding cybersecurity frameworks and information security standards—a review and comprehensive overview. Electronics, 11(14), 2181. https://www.mdpi.com/2079-9292/11/14/2181.

- Tariq, N., Khan, F. A., & Asim, M. (2021). Security challenges and requirements for smart internet of things applications: A comprehensive analysis. Procedia Computer Science, 191, 425-430. [CrossRef]

- Toh, C. K. (2020). Security for smart cities. IET Smart Cities, 2(2), 95-104. [CrossRef]

- Toussaint, M., Krima, S., & Panetto, H. (2024). Industry 4.0 data security: A cybersecurity frameworks review. Journal of Industrial Information Integration, 100604. [CrossRef]

- Ullah, F., Qayyum, S., Thaheem, M. J., Al-Turjman, F., & Sepasgozar, S. M. E. (2021). Risk management in sustainable smart cities governance: A TOE framework. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 167, 120743. [CrossRef]

- Verhulsdonck, G., Weible, J. L., Helser, S., & Hajduk, N. (2023). Smart cities, playable cities, and cybersecurity: A systematic review. International Journal of Human–Computer Interaction, 39(2), 378-390. [CrossRef]

- Vitunskaite, M., He, Y., Brandstetter, T., & Janicke, H. (2019). Smart cities and cyber security: Are we there yet? A comparative study on the role of standards, third party risk management and security ownership. Computers & Security, 83, 313-331. [CrossRef]

- Wolff, J., & Lehr, W. (2018). When cyber threats loom, what can state and local governments do? Georgetown Journal of International Affairs, 19, 67-75. [CrossRef]

- Woodburn. (2021). Cybersecurity policy and procedures. Woodburn, Oregon, USA Retrieved from https://www.woodburn-or.gov/sites/default/files/fileattachments/human_resources/page/13801/cybersecurity_policy.pdf.

- Wu, Y. C., Sun, R., & Wu, Y. J. (2020). Smart city development in Taiwan: From the perspective of the information security policy. Sustainability, 12(7), Article 2916. [CrossRef]

- Yigitcanlar, T., Agdas, D., & Degirmenci, K. (2023a). Artificial intelligence in local governments: Perceptions of city managers on prospects, constraints and choices. AI & Society, 38(3), 1135-1150. [CrossRef]

- Yigitcanlar, T., Li, R. Y. M., Beeramoole, P. B., & Paz, A. (2023b). Artificial intelligence in local government services: Public perceptions from Australia and Hong Kong. Government Information Quarterly, 40(3), 101833. [CrossRef]

| Function | Category | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Govern | Organisational Context | Organisation’s mission, goal, stakeholder expectations, legal requirements. |

| Risk Management Strategy | Priorities, constraints, risk appetite and tolerance statements, and assumptions of the organisation are established, disseminated, and utilised to support operational risk decisions. | |

| Roles, Responsibilities, and Authorities | Establishment and communication of cybersecurity roles, responsibilities, and authorities to promote accountability. | |

| Policy | Cybersecurity policy is established, communicated, and enforced. | |

| Oversight | The outcomes and performance of risk management activities are utilised to inform, enhance, and modify the risk management strategy. | |

| Cybersecurity Supply Chain Risk Management | Supply chain risk management processes are identified, established, managed, monitored, and improved. | |

| Identify | Asset Management | Managing of assets, including personnel, facilities, services, data, hardware, software, and systems. |

| Risk Assessment | Understanding risk to the organisation, its assets, and involved individuals. | |

| Improvement | Necessary improvement to organisational cybersecurity risk management processes, procedures, and activities. | |

| Protect | Identity Management, Authentication, and Access Control | Restricting access to assets to only authorised users, services, and hardware. |

| Awareness and Training | Training staff about cybersecurity related activities and raising awareness. | |

| Data Security | Management of data consistent with organisation’s risk strategy. | |

| Platform Security | Management of hardware, software, systems, applications, and services of physical and virtual platforms consistent with organisation’s risk strategy. | |

| Technology Infrastructure Resilience | Management of security architecture in accordance with the organisation’s risk strategy. | |

| Detect | Continuous Monitoring | Monitoring assets to detect anomalies, adverse events, potential breach. |

| Adverse Event Analysis | Events are analysed to characterise and learn about them for future detection. | |

| Respond | Incident Management | Managing incidents through response mechanism. |

| Incident Analysis | Support forensics and recovery efforts and to ensure an effective response. | |

| Incident Response Reporting and Communication | Coordinating response activities with internal and external stakeholders. | |

| Incident Mitigation | Preventing the escalation of an incident and alleviating its consequences. | |

| Recover | Incident Recovery Plan Execution | Ensuring operational availability of systems and services. |

| Incident Recovery Communication | Coordination of restoration activities involving both internal and external stakeholders. |

| LG | Location | LG Status | Population | Policy Adoption/ Last Update Year | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country Capital | State | State Capital | Metropolitan | Rural Area | 2021 | |||

| Central Highlands Council | Australia | ✓ | 2,144 | Not Mentioned | ||||

| Murray River Council | ✓ | 11,456 | 2022 | |||||

| Sutherland Shire Council | ✓ | 218,464 | 2023 | |||||

| Bayswater | ✓ | 69,283 | 2021 | |||||

| Western Australia | ✓ | 2,660,026 | 2022 | |||||

| New South Wales | ✓ | 8,072,163 | 2022 | |||||

| Tasmania | ✓ | 557,571 | 2023 | |||||

| Murrumbidgee Council | ✓ | 4,000 | 2021 | |||||

| Rous County Council | ✓ | 100,000 | 2019 | |||||

| King Island Council | ✓ | 1,617 | 2022 | |||||

| Copper Coast Council | ✓ | 15,050 | 2022 | |||||

| Balranald Shire Council | ✓ | 2,208 | 2023 | |||||

| Vancouver | Canada | ✓ | 662,248 | 2022 | ||||

| Greenview | ✓ | 8,584 | 2016 | |||||

| London | England | ✓ | ✓ | 9,748,033 | 2023 | |||

| Enfield | ✓ | 330,000 | 2021 | |||||

| Northwest Leicestershire District Council | ✓ | 104,705 | 2020 | |||||

| Crediton Town | ✓ | 21,990 | 2020 | |||||

| Royal Borough Windsor & Maidenhead (RBWM) | ✓ | 154,738 | 2021 | |||||

| Saughall and Shotwick Park Parish Council | ✓ | 3,094 | 2022 | |||||

| Aylesford Parish Council | ✓ | 11,671 | 2022 | |||||

| Telangana | India | ✓ | 38,157,311 | 2021 | ||||

| Odisha | ✓ | 47,099,270 | 2022 | |||||

| Jammu and Kashmir | ✓ | 14,999,397 | 2020 | |||||

| Tamil Nadu | ✓ | 83,697,770 | 2020 | |||||

| Assam | ✓ | 35,713,000 | 2018 | |||||

| Tripura | ✓ | 4,184,959 | ||||||

| Woodburn City Council | USA | ✓ | 26,243 | 2019 | ||||

| City and County of San Francisco | ✓ | 670,625 | 2021 | |||||

| New York | ✓ | 7,613,466 | 2020 | |||||

| Village of Pleasantville | ✓ | 7,305 | 2021 | |||||

| Beaverton | ✓ | 100,559 | 2022 | |||||

| Albuquerque | ✓ | 556,496 | 2023 | |||||

| Portland | ✓ | 13,701 | 2020 | |||||

| Scappoose | ✓ | 8,191 | 2020 | |||||

| City of Madras | ✓ | 8,200 | 2020 | |||||

| Town of Norwich | ✓ | 6,476 | 2021 | |||||

| City of Lebanon | ✓ | 48,629 | 2022 | |||||

| Function | Category |

|---|---|

| Govern | Organisational Context, Risk Management Strategy, Roles, Responsibilities, and Authorities, Policy, Oversight, and Cybersecurity Supply Chain Risk Management |

| Identify | Asset Management, Risk Assessment, Improvement |

| Protect | Identity Management, Authentication, and Access Control, Awareness and Training, Data Security, Platform Security, Technology Infrastructure Resilience |

| Detect | Continuous Monitoring, Adverse Event Analysis |

| Respond | Incident Management, Incident Analysis, Incident Response Reporting and Communication, Incident Mitigation |

| Recover | Incident Recovery Plan Execution, Incident Recovery Communication |

| Code and Document Frequency | Sub-Code | Documents with Sub-Code | Frequency of Sub-Code | Total Frequency for Sub-Codes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Govern = 37 | Organisational Context | 27 | 71 | 220 |

| Risk Management Strategy | 22 | 37 | ||

| Roles, Responsibilities, and Authorities | 27 | 76 | ||

| Policy | 21 | 31 | ||

| Oversight | 0 | 0 | ||

| Cybersecurity Supply Chain Risk Management | 4 | 5 | ||

| Identify = 29 | Asset Management | 25 | 42 | 71 |

| Risk Assessment | 14 | 18 | ||

| Improvement | 9 | 11 | ||

| Protect = 32 | Identity Management, Authentication, and Access Control | 29 | 77 | 222 |

| Awareness and Training | 24 | 40 | ||

| Data Security | 18 | 51 | ||

| Platform Security | 15 | 43 | ||

| Technology Infrastructure Resilience | 5 | 11 | ||

| Detect = 19 | Continuous Monitoring | 19 | 23 | 34 |

| Adverse Event Analysis | 7 | 11 | ||

| Respond = 30 | Incident Management | 27 | 44 | 64 |

| Incident Analysis | 2 | 2 | ||

| Incident Response Reporting and Communication | 9 | 13 | ||

| Incident Mitigation | 5 | 5 | ||

| Recover = 16 | Incident Recovery Plan Execution | 16 | 20 | 22 |

| Incident Recovery Communication | 2 | 2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).