Submitted:

10 May 2024

Posted:

10 May 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

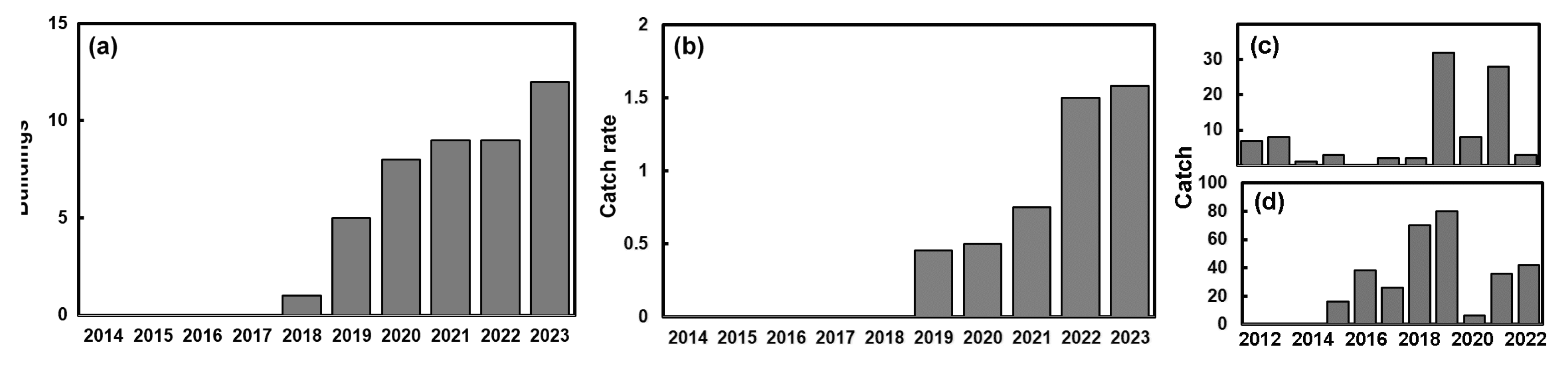

3.1. Overall Catch

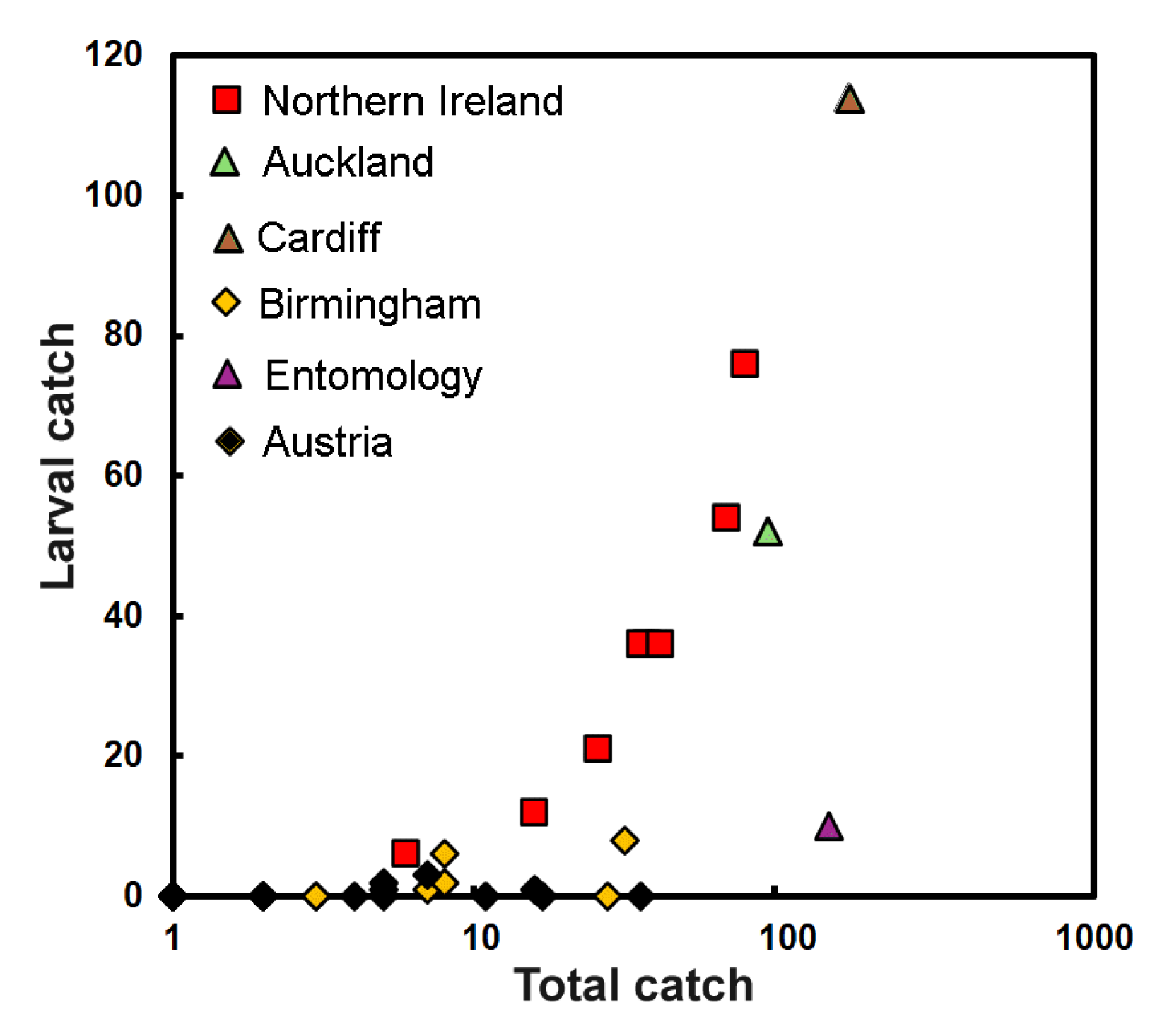

3.2. Larvae and Adults

3.3. Implications for Heritage Environment

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nardi G, Hava J. Chronology of the worldwide spread of a parthenogenetic beetle, Reesa vespulae (Milliron, 1939)(Coleoptera: Dermestidae). Fragmenta entomologica. 2021 Nov 30;53(2):347-56.

- Hudgins EJ, Cuthbert RN, Haubrock PJ, Taylor NG, Kourantidou M, Nguyen D, Bang A, Turbelin AJ, Moodley D, Briski E, Kotronaki SG. Unevenly distributed biological invasion costs among origin and recipient regions. Nature Sustainability. 2023 Sep;6(9):1113-24. [CrossRef]

- Turbelin AJ, Cuthbert RN, Essl F, Haubrock PJ, Ricciardi A, Courchamp F. Biological invasions are as costly as natural hazards. Perspectives in Ecology and Conservation. 2023 Apr 1;21(2):143-50. [CrossRef]

- Linnie MJ. Pest control in natural history museums: A world survey. Journal of Biological Curation. 1994;1(5):43-58.

- McLean.

- Somerfield KG. Recent aspects of stored product entomology in New Zealand. New Zealand Journal of Agricultural Research. 1981 Jul 1;24(3-4):403-8. [CrossRef]

- Bahr I., Nussbaum P.. Reesa vespulae (Milliron) (Coleoptera: Dermestidae), ein neuer Schädling an Sämereien in der Deutschen Demokratischen Republik. Nachrichtenblatt für den Deutschen Pflanzenschutzdienst, 28: 1974, 229–231.

- Bunalski M, Przewoźny M. First record of Reesa vespulae (Milliron, 1939)(Coleoptera, Dermestidae), an introduced species of dermestid beetle in Poland. Polish Journal of Entomology. 2009;78(4):341-5.

- Zhantiev RD. New and little known Dermestids (Coleoptera) in the fauna of the USSR. Zoologicheskii zhurnal. 1973.

- Adams, R.G. 1978. The first British infestation of Reesa vespulae (Milliron) (Coleoptera: Dermestidae). Entomologist’s Gazette, 29: 73–75.

- Stejskal, V., & Kučerová, Z. (1996). Reesa vespulae (Col., Dermestidae) a new pest in seed stores in the Czech Republic. Ochr. Rostl. 32, 1996, 97-101.

- Tsvetanov TS, Háva JI. First record of Reesa vespulae (Milliron, 1939) in Bulgaria (Insecta: Coleoptera: Dermestidae). ZooNotes. 2020 Jul 1;162:1-3.

- Háva J. 2003. World Catalogue of the Dermestidae (Coleoptera). Studie a zprávy oblastního muzea Praha – východ v Brandýse nad Labem a Staré Boleslavi, Supplementum, 1: 1–196.

- Sellenschlo U. Nachweis des Nordamerikanischen Wespenkäfers Reesa vespulae (Col., Dermestidae) in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland. Neue Ent. Nachr. 1986;19(1/2):43-6.

- Manachini B, Billeci N, Palla F. Exotic insect pests: The impact of the Red Palm Weevil on natural and cultural heritage in Palermo (Italy). Journal of Cultural Heritage. 2013 Jun 1;14(3):e177-82.

- Brimblecombe, P. Insect threat to UK Heritage in changing climates, Journal of the Institute of Conservation, 2024, 16,.

- Hansen, L.S.; Åkerlund, M.; Grøntoft, T.; Ryhl-Svendsen, M.; Schmidt, A.L.; Bergh, J.-E.; Jensen, K.-M.V. Future pest status of an insect pest in museums, Attagenus smirnovi: Distribution and food consumption in relation to climate change. J. Cult. Herit. 2012, 13, 22–27. [CrossRef]

- Querner, P.; Szucsich, N.; Landsberger, B.; Erlacher, S.; Trebicki, L.; Grabowski, M.; Brimblecombe, P. Identification and Spread of the Ghost Silverfish (Ctenolepisma calvum) among Museums and Homes in Europe. Insects 2022, 13, 855. [CrossRef]

- Poggi, R., (2007) Gastrallus pubescens Fairmaire un pericolo per le biblioteche italiane. Annali Museo Civico Storia Naturale “Doria” di Genova, Vol. XCVIII, pp. 551-562.

- Savoldelli S, Cattò C, Villa F, Saracchi M, Troiano F, Cortesi P, Cappitelli F. Biological risk assessment in the History and Historical Documentation Library of the University of Milan. Science of the Total Environment. 2021 Oct 10;790:148204. [CrossRef]

- Querner, P.; Sterflinger, K.; Derksen, K.; Leissner, J.; Landsberger, B.; Hammer, A.; Brimblecombe, P. Climate Change and Its Effects on Indoor Pests (Insect and Fungi) in Museums. Climate 2022, 10, 103. [CrossRef]

- Manachini B. Alien insect impact on cultural heritage and landscape: An underestimated problem. Conservation Science in Cultural Heritage. 2015;15(2):61-72.

- Vaucheret S., Leonard L. 2015. Dealing with an infestation of Reesa vespulae while preparing to move to new stores, pp. 71–76. In: Windsor P., Pinniger D., Bacon L., Child B., Harris K. (eds), Integrated Pest Management for Collections. proceeding of 2011: A Pest Odyssey, 10 Years Later. English Heritage, Swindon.

- Makisalo, I. (1970). A new pest of museums in Finland - Reesa vespulae (Mill.)(Col., Dermestidae). In Annales Entomologici Fennici (Vol. 36, No. 4, pp. 192-195). Entomological Society of Finland.

- Ackery, P.R., Pinniger, D.B., & Chambers, J. (1999). Enhanced pest capture rates using pheromone baited sticky traps in museum stores. Studies in conservation, 44(1), 67-71. [CrossRef]

- Hong KJ, Kim M, Park DS. Molecular identification of Reesa vespulae (Milliron)(Coleoptera: Dermestidae), a newly recorded species from Korea. Journal of Asia-Pacific Biodiversity. 2014 Sep 30;7(3):305-7.

- Miller, G. Socializing Integrated Pest Management (2019) Integrated Pest Management (IPM) for Cultural Heritage Proceedings from the 4th International Conference in Stockholm, Sweden, 21–23 May 2019 109-118.

- Koutsoukos E, Demetriou J, Háva J. First records of Phradonoma cercyonoides and Reesa vespulae (Coleoptera: Dermestidae: Megatominae: Megatomini) in Greece. Israel Journal of Entomology. 2021 Jul 3;51:67-72.

- Baron 2024 Personal communication.

- Peacock E.R. Adults and larvae of hide, larder and carpet beetles and their relatives (Coleoptera: Dermestidae) and of derodontid beetles (Coleoptera: Derodontidae). Handbooks for the Identification of British Insects, 5 (1993), pp. 1-1441.

- Bahr I, Bogs D, Nussbaum P, Thiem H. Zur Verbreitung, Lebensweise und Bekämpfung von Reesa vespulae (Milliron) als Schädling von Sämereien. NachrBl. PflSchutz DDR 33:209-214.

- Querner P. Insect pests and integrated pest management in museums, libraries and historic buildings. Insects. 2015 Jun 16;6(2):595-607. [CrossRef]

- Brimblecombe P, Lankester P. Long-term changes in climate and insect damage in historic houses. Studies in Conservation. 2013 Jan 1;58(1):13-22. [CrossRef]

- Brimblecombe P, Querner P. Changing insect catch in Viennese museums during COVID-19. Heritage. 2023 Mar 8;6(3):2809-21. [CrossRef]

- GBIF https://www.gbif.org/.

- Brimblecombe, P.; Brimblecombe, C.T.; Thickett, D.; Lauder, D. Statistics of insect catch within historic properties. Herit Sci. 2013, 34, 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Vendl T, Kadlec J, Aulicky R, Stejskal V. Survey of dermestid beetles using UV-light traps in two food industry facilities in the Czech Republic: One year field study. Journal of Stored Products Research. 2024 Feb 1;105:102234. [CrossRef]

- Baars, C., Henderson, J. Integrated pest management: from monitoring to control. 142-147 Published in: Ryder, Suzanne and Crossman, Amy eds. Integrated Pest Management for Collections: Proceedings of 2021: A Pest Odyssey – The Next Generation. London UK: Archetype, pp. 142-147 (2022).

- Baars, C., Henderson, J. Novel ways of communicating museum pest monitoring data: practical implementation. Conference: Integrated Pest Management (IPM) for Cultural Heritage: proceedings from the 4th International Conference in Stockholm, Sweden, 21–23 May 2019 (2020).

- Brimblecombe P, Querner P. Investigating insect catch metrics from a large Austrian museum. Journal of Cultural Heritage. 2024 Mar 1;66:375-83. [CrossRef]

- Pinniger, D 2001 ‘New pests for old: The changing status of museum insect pests in the UK’ in Kingsley, H, Pinniger, D, XavierRowe, A, Winsor, P (eds) Integrated Pest Management for Collections, Proceedings of 2001: A Pest Odyssey conference, London, 1–3 October 2001, London: James & James, 9–13..

- Parry E. Reesa vespulae (Coleoptera: Dermestidae): a rare synanthropic beetle found in a Glasgow tenement. Glasgow Naturalist (online 2024).;28(Part 2). [CrossRef]

- Novak I, Verner P. Faunistic records from Czechoslovakia. Coleoptera, Dermestidae. Acta Entomologica Bohemoslovaca. 1990;87(6).

- Arevad K. Control of dermestid beetles by refrigeration. Danish Pest Infestation Laboratory, Annual Report. 1974;41.

- Bergh JE, Jensen KM, Åkerlund M, Hansen L.S., Andrén M. A contribution to standards for freezing as a pest control method for museums. InCollection forum 2006 (Vol. 21, No. 1-2, pp. 117-125). Society for the Preservation of Natural History Collections (SPNHC).

- Bergh JE, Stengård Hansen L.S., Vagn Jensen KM, Nielsen PV. The effect of anoxic treatment on the larvae of six species of dermestids (Coleoptera). Journal of applied entomology. 2003 Jul;127(6):317-21. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).