Introduction

Small cell lung cancer (SCLC) represents 10 to 15% of lung cancers [

1]. It is estimated that 95% of SCLC cancers are caused by smoking [

2]. Diagnosis is frequently made at an advanced stage, with no curative-intent treatment option [

3]. Since the early 1980s, treatment of Extensive Stage (ES) SCLC has been based on a doublet of chemotherapy including platinum salts and etoposide [

4]. In 2018 the CASPIAN and IMPOWER133 trials established anti-PD-L1 immunotherapy plus platinum based chemotherapy as a new standard of care [

5,

6].

The CASPIAN trial was an open-label randomised three-arm multicentre study, initially designed to test the hypothesis that Durvalumab + Tremelimumab + Etoposide and Carboplatin or Cisplatin chemotherapy (D + T + EP arm) or Durvalumab + EP chemotherapy (D + EP arm) as first-line treatment in ES-SCLC achieve better PFS and OS when compared to EP chemotherapy alone (EP arm). Patients with brain metastasis were eligible, providing that they didn’t have neurologic symptoms and/or the metastasis were treated and stable off steroids and anti-convulsivant. ECOG must have been 0 or 1 at enrolment. Patients were stratified per type of platinum chemotherapy (Carboplatin vs Cisplatin). There was no cross-over planned in the study. A total of 805 patients were randomised to receive D + T + EP (n=268), D + EP (n=268) or EP (n=269). Patients’ characteristics were well balanced between the D + EP and EP arms, but were slightly less favourable for the D + T + EP arm, with more patients having brain metastasis (14% vs 10%) and liver metastasis (44% vs 39%). Although the median PFS was not improved by the addition of Durvalumab to the EP chemotherapy (5.1 months vs 5.4 months, respectively), the overall survival was better in the D + EP arm compared to the EP arm (12.9 months vs 10.5 months). The objective response rate was also improved (68% vs 58%). The PFS (4.9 months vs 5.4 months) and the OS (10.4 months vs 10.5 months) were not improved by the addition of Durvalumab + Tremelimumab to the EP chemotherapy.

Similarly, in the IMPOWER 133 trial, 403 patients with treatment-naïve ES-SCLC were randomised to receive Atezolizumab + carboplatin and etoposide (no cisplatin) chemotherapy or carboplatin + etoposide chemotherapy alone. Patients with brain metastasis were eligible, providing that the metastasis were treated and stable off steroids and anti-convulsivant. ECOG must have been 0 or 1 at enrolment. Patients were stratified per gender, ECOG and presence of brain metastases. The PFS was improved by the addition of Atezolizumab to the EP chemotherapy (5.2 months vs 4.3 months), as well as the OS (12.3 months vs 10.3 months).

In the KEYNOTE 604 trial, that compared EP chemotherapy to EP + Pembrolizumab, the PFS was improved by the addition of Pembrolizumab to chemotherapy (4.8 months vs 4.3 months), but not the OS (10.8 months vs 9.7 months). As a consequence, Pembrolizumab is not approved for the treatment of ES-SCLC [

7].

In the ECOG ACRIN 5161 trial, that compared EP chemotherapy to EP + Nivolumab, the OS was improved by the addition of Nivolumab to chemotherapy (11.3 months vs 8.5 months)[

8].

In the REACTION trial, 119 patients with ES-SCLC that showed partial or complete response to two cycles of EP chemotherapy were randomized to receive EP alone, for 4 additional cycles, vs EP + Pembrolizumab for 4 additional cycles and Pembrolizumab maintenance [

9]. The OS was better in the experimental arm (12.3 months vs 10.4 months).

Despite this major advance, prognosis remains poor, with a median overall survival (OS) of 12.3 months and 13.3 months in the two pivotal studies, respectively. In fact, immunotherapy appears beneficial only for a small subset of patients (roughly 10%), despite SCLC is one of the malignancies with the higher Tumor Mutational Burden, which should have made it a good candidate for immunotherapy [

10]. Over the last 4 years, molecular subtypes of SCLC have been described, based on transcriptional signatures. Among them, the “inflamed” subgroup, that represents around 10% of cases, seems to be the most sensitive to immunotherapy [

11]. Prospective trials using different treatments according to molecular subgroups are ongoing.

In most cases, tumor relapses after first-line treatment[

12]. In phase II studies, conducted in selected patients, outcomes of ES-SCLC patients receiving second-line treatment are poor with a median OS of 2 to 9 months [

13]. In this setting, Topotecan was compared to best supportive care (BSC) and showed an OS improvement (5.8 vs 3.2 months) [

14]. In another study evaluating Topotecan, RR was 24.3% and median OS 5.8 months [

15]. Topotecan was non-inferior to cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and vincristine (RR 18,3%, median OS 5.8 months), but Topotecan improved quality of life. In the CheckMate 331 study, Topotecan was compared to Nivolumab in relapsed ES-SCLC and achieved similar OS (8.4 vs 7.5 months, respectively, with HR 0.86 [95% CI 0.72-1.04] and p=0.11), although a small subgroup of patients achieved long-term survival with Nivolumab [

16].

RR, OS and PFS in the second-line setting are influenced by the treatment-free interval from first-line chemotherapy [

13]. A French prospective study of 162 relapsed chemo-sensitive ES-SCLC patients showed an improved PFS with rechallenge platinum-based chemotherapy vs Topotecan: 4.7 months

vs 2.7 months (p<0.01). However, there was no difference in OS [

17].

In the ATLANTIS trial, a combination of lurbinectedin and doxorubicin was compared to physician’s choice in patients with relapsed SCLC [

18]. 613 patients were randomly assigned to lurbinectedin plus doxorubicin (n=307) or control (topotecan, n=127; CAV, n=179). Median overall survival was 8.6 months (95% CI 7·1-9·4) in the lurbinectedin plus doxorubicin group versus 7·6 months (6.6-8.2) in the control group (hazard ratio 0.97 [95% CI 0.82-1.15], p=0·70). The safety profile was more favourable with lurbinectedin and doxorubicin compared to the control arm, with less grade ≥3 adverse events, less adverse events leading to treatment discontinuation and less fatal adverse events.

More recently, Tarlatamab, a bispecific T-cell engager antibody targeting DLL3 and CD3, showed encouraging results in relapsed ES-SCLC, with a 32-40% response rate [

19]. However, the safety profile of this molecule raises concerns about its use in frail patients, with grade ≥3 adverse events in 58-65% of patients, including a serious Cytokine-release syndrome (CRS) in 15-37% patients and a serious immune effector cell-associated neurotoxicity syndrome (ICANS) in 2-13%of patients.

In the NabSTER trial, a single-arm phase 2 study, Nab-Paclitaxel was evaluated in sensitive or refractory relapsed ES-SCLC [

20]. Partial response occurred in 8% in the refractory cohort and 14% in the sensitive cohort, respectively. PFS was similar in both cohorts (sensitive: 1.8 months; refractory: 1.9 months), OS was longer in the sensitive cohort (6.6 months vs 3.6 months).

Topotecan is still considered the reference treatment for relapsed SCLC. However, its toxicity remains an issue, especially in altered patients. Thus, when 13 European experts were surveyed about second-line treatment options to be considered for relapsed ES-SCLC patients, other treatments were proposed, including Paclitaxel Gemcitabine, Nivolumab or BSC [21].

Paclitaxel Gemcitabine has been evaluated in three phase 2 studies, gathering 105 patients in total, showing PFS between 2.2 and 2.7 months and OS between 5.5 and 7.5 months. [22,23,24]. Toxicities were considered low.

Since 2008, Paclitaxel Gemcitabine has been used in our centers. This study was undertaken to evaluate Paclitaxel Gemcitabine safety and efficacy in patients with relapsed SCLC in a real-life setting and to identify predictive factors of survival.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective multicentric study. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board for non-interventional research of our center (protocol agreement # E2021-76). All consecutive patients with a diagnosis of relapsed SCLC not amenable to curative intent radiotherapy and who received chemotherapy with Paclitaxel Gemcitabine from January 1st 2008 to December 31st 2022 were identified through the chemotherapy prescription software and assessed for eligibility. Patient’s selection criteria were: age ≥18 years, histologically proven ES-SCLC, tumor relapse after ≥1 line of platinum-based chemotherapy, treatment with ≥1 Paclitaxel Gemcitabine infusion. Exclusion criteria was patient’s refusal. Clinical data were extracted from electronic health records. Toxicity was assessed according to the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events v5.0 classification.

Paclitaxel Gemcitabine efficacy was evaluated according to the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST 1.1). Objective response rate (ORR) was defined as the percentage of patients having a complete or partial response, and disease-control rate (DCR) as the percentage of patients having a complete or partial response or stabilized disease. Progression-free survival (PFS) was defined as survival from Paclitaxel Gemcitabine start to disease progression or any cause of death and overall survival (OS) as survival from Paclitaxel Gemcitabine start until any cause of death. Duration of Response (DoR) was defined as the time between the occurrence of partial or complete tumor response to disease progression or any cause of death.

Categorical variables are expressed as percentage of the population and continuous variables as median and interquartile range (IQR) for non-normally distributed variables and mean ± standard deviation (SD) for normally distributed variables. OS, PFS and DoR were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method. Cox proportional hazards models were used to investigate each variable’s association with OS and PFS. Variables achieving p<0.1 prognostic association were then entered into a multivariable Cox regression model to determine their independent impact. Associations between categorical variables were assessed with Pearson’s χ2 or Fisher’s exact test. Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05 unless otherwise specified. Statistical analyses were computed using R (R Foundation for Statistical Computing).

Results

Patients Characteristics

A total of 231 patients were identified from the chemotherapy prescription software at our institutions. Among them, 188 (125 from Rouen university hospital and 63 from Baclesse cancer center) met the eligibility criteria and were included in the study. Specifically, 38 patients were excluded because of a histological diagnosis other than SCLC and 5 because they did not receive any Paclitaxel or Gemcitabine infusion. Baseline characteristics of patients are shown in

Table 1. Of note, 24.5% had a Performance Status (PS) ≥2, 42% had brain metastasis and 59% had platinum-resistant disease. Median number of Paclitaxel Gemcitabine chemotherapy cycles was 2 (IQR: 1-3), with 86 patients (45%) receiving only 1 cycle, because of ECOG PS worsening or death. Among patients with PS≥2 at baseline, 58% did not receive more than one cycle.

Efficacy

In the overall population, response rate was 32/188 (17.0%), with 1 complete response and 31 partial responses. In addition, 20/188 (10.6%) patients had stable disease as best response. DCR was 27.6%.

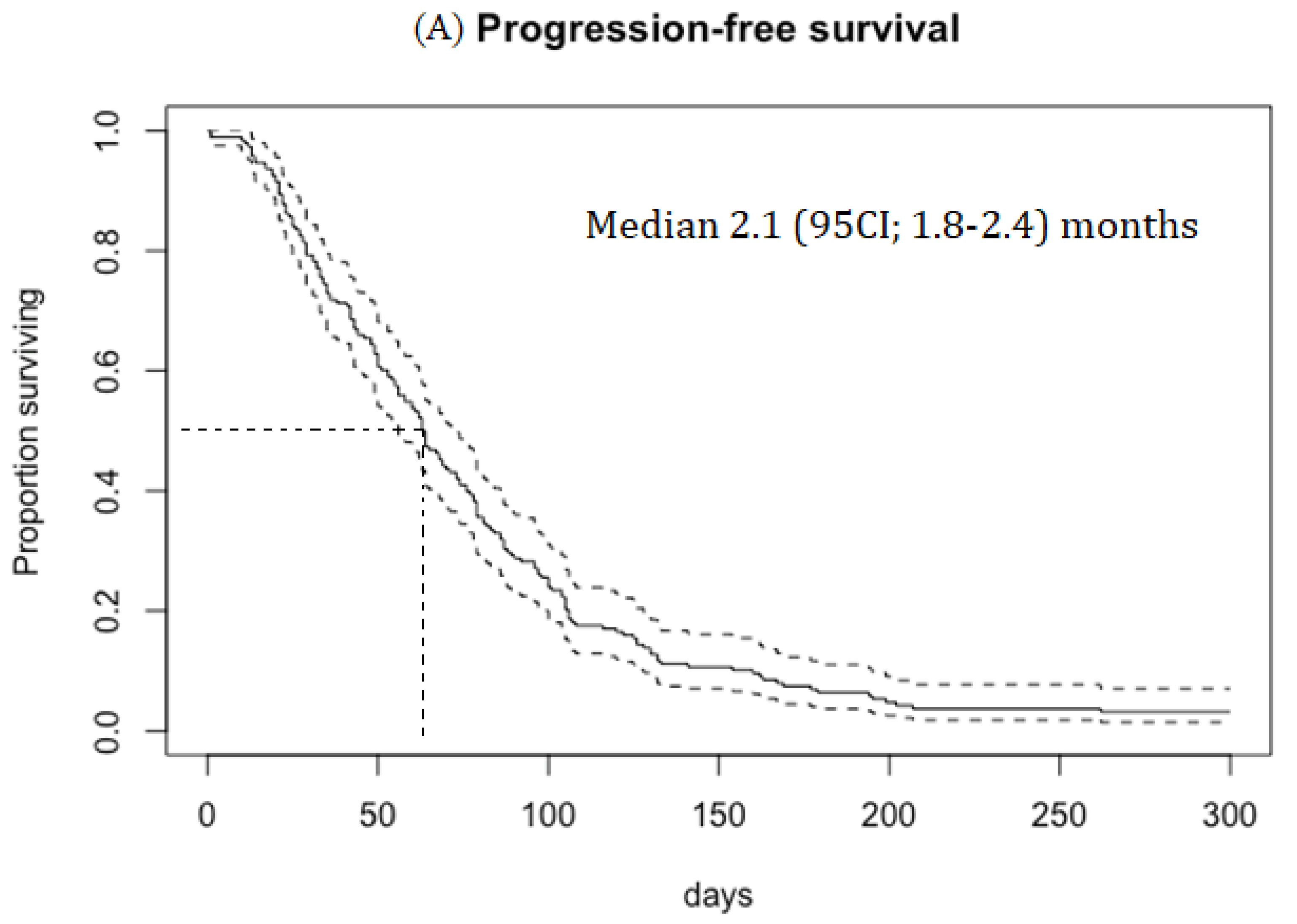

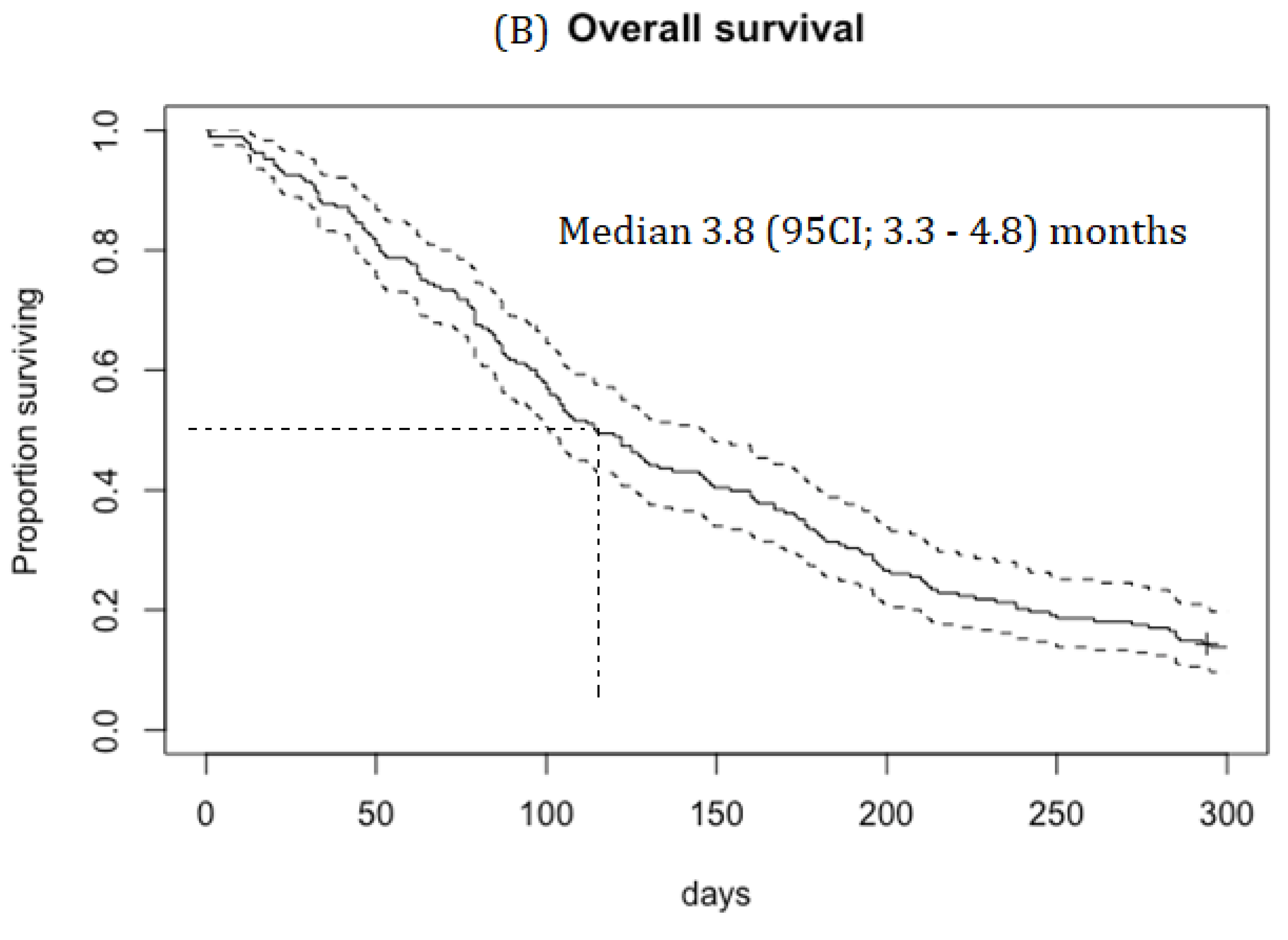

Median PFS was 2.1 (95CI; 1.8–2.4) months, duration of response (DOR) was 4.1 (95CI; 3.4-5.5) months and OS was 3.8 (95CI; 3.3–4.8) months (

Figure 1A). RR was 19.5% in patients with platinum-sensitive disease and 15.3% in patients with platinum-resistant disease.

RR was 21% in PS 0-1 patients, with median PFS, DOR and OS of 2.5 (95CI; 1.7–3.9) months, 4.1 (95CI; 3.4-5.5) months and 5.8 (95CI; 4.3-6.6) months, respectively.

Of note, outcomes in PS3 patients were very poor (PFS 0.9 months, 95CI (0.5-1.1); OS 0.9 months, 95CI (0.5-1.1)).

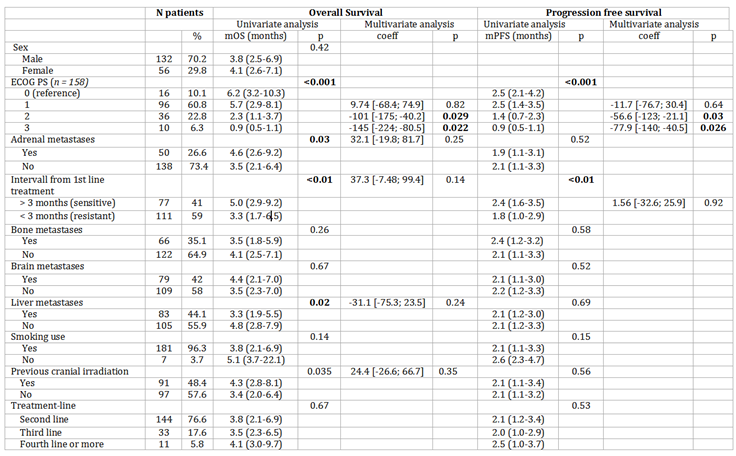

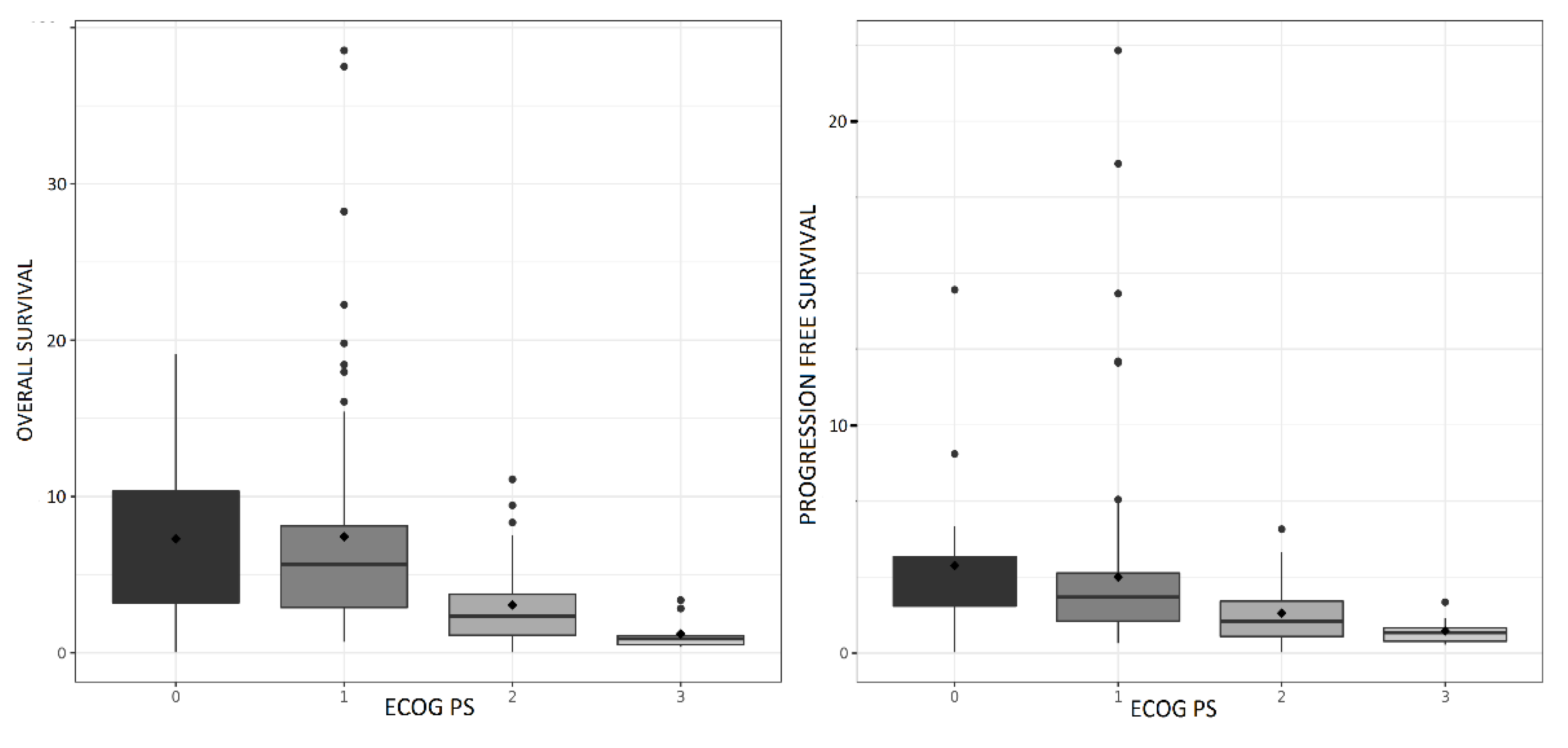

PS, history of brain radiation, platinum-sensitive disease, liver and adrenal gland metastasis were associated with a longer survival in univariate analysis (Table 2). PS was associated with a longer survival in multivariate analysis. PFS and OS according to PS are shown in

Figure 1B.

Table 2.

Univariate and multivariate analysis for OS and PFS. P-values <0.05 appeared in bold characters.

Table 2.

Univariate and multivariate analysis for OS and PFS. P-values <0.05 appeared in bold characters.

Safety

During Paclitaxel Gemcitabine treatment, 133 patients (70.7%) presented ≥1 adverse event. Forty-five patients (23.9%) had grade 3 toxicity: 7 neutropenia (3.7%), 15 anemia (8.0%), 23 thrombocytopenia (12.2%). There were 11 (5.6%) grade 4 neutropenia, 9 grade 4 thrombocytopenia (4.8%) and 1 grade 4 anemia (0.5%). There was no grade 5 adverse event related to Paclitaxel Gemcitabine.

Discussion

This real-world analysis of Paclitaxel Gemcitabine chemotherapy in unselected consecutive patients treated for relapsed SCLC showed a 27.6% DCR. These results are inferior to those described in the literature (42 to 54%), composed of phase II studies with smaller size populations and more selected patients. Similarly, median OS (3.8 months) was shorter than previously reported outcomes (5.5 to 7.5 months) [22,23,24].

Of note, our patients were older than in the phase II studies and with a poorer PS (24.5% PS≥2 vs 3% in Yun study [22], 15% in Dazzi study [24] and 26% in DonGiovanni [23] study). PS was correlated with OS after multivariate analysis in our study. Of note, OS among patients with ECOG 0-1 in our study (5.8 months) was similar to those reported in the three phase 2 studies.

Our study population comprised also less patients with platinum-sensitive disease. Resistance to first-line treatment is associated with a lower survival and a lower RR to subsequent treatments [21]. In our study, 41.0% had a platinum-sensitive disease, less than in the above-mentioned phase II studies (50 to 65%).

Moreover, 42% of patients from our study had brain metastasis, versus 12% in Dazzi's study and 16% in Dongiovanni's study (not reported in Yun’s study).

Toxicity profile of Paclitaxel Gemcitabine was mainly related to cytotoxicity and appeared manageable, with a low rate of grade ≥3 neutropenia, without use of primary G-CSF prophylaxis.

The main strengths of our study are the population size in a rare disease, its multicenter design, the inclusion of a large proportion of resistant disease, and the enrollment of all consecutive patients treated with Paclitaxel Gemcitabine for relapsed SCLC. The main weakness of our study is the retrospective design and the number of missing data for some characteristics, notably the ECOG-PS and probably low-grade toxicities.

The only agent specifically approved for second-line treatment of SCLC is Topotecan. For patients with platinum-sensitive disease, platinum rechallenge was shown to offer better PFS [

17]. Efficacy of Topotecan is modest and its toxicity is limiting, particularly in frail patients. A frequently mentioned alternative regimen is chemotherapy with Cyclophosphamide, Doxorubicin and Vincristin. This combination seems to be as effective as Topotecan, but resulted in poorer control of symptoms, and similar toxicity profile [

15]. Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI) have also been studied in this setting. Efficacy results of ICI treatment in relapsed SCLC were generally disappointing, although some patients derived long-term benefit [25,26]. Moreover, since the standard first-line treatment for ES-SCLC is now platinum-based chemotherapy in association with ICI and ICI maintenance [

5,

6], the use of ICI in subsequent lines has to be reassessed. Recently, Lurbinectedin was studied in the setting of relapsed SCLC. In a phase II study, treatment with Lurbinectedin 3.2mg/m² as a monotherapy achieved an ORR of 35.2%, with median OS and PFS of 9.3 months and 3.5 months, respectively[27]. Nevertheless, the results of the phase III ATLANTIS study (lurbinectedin 2mg/m² plus doxorubicin vs. topotecan or CAV) did not show a superiority of chemotherapy with Lurbinectedin plus Doxorubicin (mOS of 8.6 months in the experimental arm vs. 7.6 months in the control arm)[

18].

Treatment with Nab-Paclitaxel as a monotherapy in the second-line setting lead to smaller response rate but similar PFS when compared to our study [

20]. Similarly to the findings of the abovementioned phase 2 studies in relapsed ES-SCLC, patients from the Nabster study had better PS (no PS 2 patients vs 24.5%) and received only 1 previous line of chemotherapy. In addition, fewer had brain metastasis when compared to our patients(12% vs 42%). The Nabster trial also included 12% of patients with large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma (LCNEC) or undifferentiated neuroendocrine carcinoma of the lung, who have a better prognosis than SCLC. Hence our study shows similar outcomes in a population with a poorer prognosis, suggesting that the addition of gemcitabine to paclitaxel or nab-paclitaxel may represent a valid option, at least for PS0-1 patients. Nevertheless, there were more grade 3 anemia and thrombopenia in our study and risk/benefit should be assessed carefully in this frail population where preserving the quality of life must be a priority.

In 2023, promising data has been reported with T-cell engager bispecific antibodies, a new class of treatment that showed encouraging activity (e.g. for Tarlatamab: RR 32-40% and PFS 4.9 months in pretreated ES-SCLC patients) [

19]. Safety of these treatments is a concern, since they trigger intense immune reaction, sometimes taking the form of cytokine release syndormes (CRS) and ICANS. The high frequency of CRS will require specific surveillance and management. This safety profile may impede the adoption of T-cell engager antibodies as a standard of care for all patients with ES-SCLC, since a large proportion of them has a poor PS and multiple comorbidities.

Conclusions

Paclitaxel Gemcitabine combination provides modest efficacy in unselected relapsed SCLC patients, albeit with favorable toxicity profile. Efficacy appears relevant for patients with ECOG PS 0-1, in a setting with limited treatment options so far. This treatment should probably not be initiated in PS≥2 patients.

Ethics

The study was approved by Institutional Review Board (agreement #E2021-76). All research was performed in accordance with relevant guidelines/regulations, namely the European Directive 2014/536/EU and the French law 2012-300 regulating biomedical research.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Conflict of Interests

FG has received personal fees for consulting or lectures from Amgen, Astra Zeneca, BMS, Sanofi, Viatris, Takeda, Roche, MSD, Pfizer and Janssen, and research grants to institution from Takeda, Roche and Pfizer, outside of the submitted work.

Abbreviations

SCLC, small cell lung cancer; ES, extensive-stage; PFS, progression free survival; OS, overall survival; BSC, best supportive care; CAV, cyclophosphamide doxorubicin vincristine; DCR, disease-control rate; RR, response rate; SD, standard deviation; IQR, interquartile range; DOR, duration of response.

References

- Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(6):394–424. [CrossRef]

- Bernhardt EB, Jalal SI. Small Cell Lung Cancer. Cancer Treat Res. 2016;170:301–22. [CrossRef]

- Pinsky PF, Church TR, Izmirlian G, Kramer BS. The National Lung Screening Trial: Results stratified by demographics, smoking history, and lung cancer histology. Cancer. 2013 Nov;119(22):3976–83. [CrossRef]

- Roth BJ, Johnson DH, Einhorn LH, Schacter LP, Cherng NC, Cohen HJ; et al. Randomized study of cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and vincristine versus etoposide and cisplatin versus alternation of these two regimens in extensive small-cell lung cancer: A phase III trial of the Southeastern Cancer Study Group. J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 1992 Feb;10(2):282–91. [CrossRef]

- Paz-Ares L, Dvorkin M, Chen Y, Reinmuth N, Hotta K, Trukhin D; et al. Durvalumab plus platinum-etoposide versus platinum-etoposide in first-line treatment of extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer (CASPIAN): A randomised, controlled, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Lond Engl. 2019 Nov;394(10212):1929–39. [CrossRef]

- Horn L, Mansfield AS, Szczęsna A, Havel L, Krzakowski M, Hochmair MJ; et al. First-Line Atezolizumab plus Chemotherapy in Extensive-Stage Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018 Dec;379(23):2220–9. [CrossRef]

- Simon GR, Turrisi A, American College of Chest Physicians. Management of small cell lung cancer: ACCP evidence-based clinical practice guidelines (2nd edition). Chest. 2007 Sep;132(3 Suppl):324S-339S. [CrossRef]

- Owonikoko TK, Behera M, Chen Z, Bhimani C, Curran WJ, Khuri FR; et al. A systematic analysis of efficacy of second-line chemotherapy in sensitive and refractory small-cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol Off Publ Int Assoc Study Lung Cancer. 2012 May;7(5):866–72. [CrossRef]

- O’Brien MER, Ciuleanu T-E, Tsekov H, Shparyk Y, Cuceviá B, Juhasz G; et al. Phase III trial comparing supportive care alone with supportive care with oral topotecan in patients with relapsed small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2006 Dec;24(34):5441–7. [CrossRef]

- von Pawel J, Schiller JH, Shepherd FA, Fields SZ, Kleisbauer JP, Chrysson NG; et al. Topotecan versus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and vincristine for the treatment of recurrent small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 1999 Feb;17(2):658–67. [CrossRef]

- Baize N, Monnet I, Greillier L, Geier M, Lena H, Janicot H; et al. Carboplatin plus etoposide versus topotecan as second-line treatment for patients with sensitive relapsed small-cell lung cancer: An open-label, multicentre, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2020 Sep;21(9):1224–33. [CrossRef]

- Ahn MJ, Cho BC, Felip E, Korantzis I, Ohashi K, Majem M; et al. Tarlatamab for Patients with Previously Treated Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2023;389(22):2063-75. [CrossRef]

- Früh M, Panje CM, Reck M, Blackhall F, Califano R, Cappuzzo F; et al. Choice of second-line systemic therapy in stage IV small cell lung cancer (SCLC) - A decision-making analysis amongst European lung cancer experts. Lung Cancer Amst Neth. 2020 Aug;146:6–11. [CrossRef]

- Dongiovanni V, Buffoni L, Berruti A, Dongiovanni D, Grillo R, Barone C; et al. Second-line chemotherapy with weekly paclitaxel and gemcitabine in patients with small-cell lung cancer pretreated with platinum and etoposide: A single institution phase II trial. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2006 Aug;58(2):203–9. [CrossRef]

- Dazzi C, Cariello A, Casanova C, Verlicchi A, Montanari M, Papiani G; et al. Gemcitabine and paclitaxel combination as second-line chemotherapy in patients with small-cell lung cancer: A phase II study. Clin Lung Cancer. 2013 Jan;14(1):28–33. [CrossRef]

- Yun T, Kim HT, Han J-Y, Yoon SJ, Kim HY, Nam B-H; et al. A Phase II Study of Weekly Paclitaxel Plus Gemcitabine as a Second-Line Therapy in Patients with Metastatic or Recurrent Small Cell Lung Cancer. Cancer Res Treat. 2016 Apr;48(2):465–72. [CrossRef]

- Spigel DR, Vicente D, Ciuleanu TE, Gettinger S, Peters S, Horn L; et al. Second-line nivolumab in relapsed small-cell lung cancer: CheckMate 331☆. Ann Oncol Off J Eur Soc Med Oncol. 2021 May;32(5):631–41. [CrossRef]

- Schmid S, Mauti LA, Friedlaender A, Blum V, Rothschild SI, Bouchaab H; et al. Outcomes with immune checkpoint inhibitors for relapsed small-cell lung cancer in a Swiss cohort. Cancer Immunol Immunother CII. 2020 Aug;69(8):1605–13. [CrossRef]

- Trigo J, Subbiah V, Besse B, Moreno V, López R, Sala MA; et al. Lurbinectedin as second-line treatment for patients with small-cell lung cancer: A single-arm, open-label, phase 2 basket trial. Lancet Oncol. 2020 May;21(5):645–54. [CrossRef]

- Aix SP, Ciuleanu TE, Navarro A, Cousin S, Bonanno L, Smit EF; et al. Combination lurbinectedin and doxorubicin versus physician's choice of chemotherapy in patients with relapsed small-cell lung cancer (ATLANTIS): A multicentre, randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2023 Jan;11(1):74-86. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).