Introduction

This research study evaluates the role of distributed leadership and culture within small enterprises in Malta. It focuses on the interaction between these two elements and their impact on organizational development. Small enterprises form an integral part of the Island’s economy. From an ‘economic value added’ perspective, small firms in Malta represent twenty-five percent of the total business economy, which is in sharp contrast with other countries across the EU where the industry is dominated by large firms. Notwithstanding their significance to the national economic model and social impact, studies on the dynamics of Leadership with specific emphasis on Distributed Leadership and Organizational Culture within Small Enterprises in the small state of Malta, are limited. It is broadly acknowledged, that studies on the dynamic behaviour of small businesses, may pose a greater challenge than the observation of more structured larger organisations (Rizzo 2011), so this may be one of the main limiting factors.

Several studies (Jardon & Martínez-Cobas 2019; Cope et al., 2011; De Oliveira et al., 2015; Mohanty et al., 2016;) suggest that effective leadership and culture are vital elements in the successful endeavours of small organizations. Schein (2004) further asserts that they are two different faces on the same coin and the dyadic interaction characterizes “how leaders create culture and how culture defines and creates leaders”.

This research study explores the possible interrelationships between variants of Distributed Leadership and cultural perspectives within small enterprises, and the effect that these two elements have on the trajectory of such organisations. Leadership and culture are active elements within an organisation, and the small firm is no exception. Aquilina (2014) claims that the business behaviour of small firms tends to be dynamic and evolves over time. A Distributed Leadership approach may bring opportunities to a growing and evolving enterprise (Cope et al 2011).

Topic Area

Distributed Leadership is a systematic practice of interactions and synergies between leaders, followers, and the situation (Spillane 2013). It is different from traditional leadership, which involves top-down management because it tends to be more democratic and participatory, whereby influence and decision-making are shared among multiple individuals rather than being controlled by a single leader. (Xhemajli et al. 2022). Distributed leadership has generated substantial interest among researchers, policymakers, and practitioners, and it has provoked debates and discussions within the field as it challenges traditional views on the relationship between formal leadership and organisational performance (Harris 2013). The small enterprise may achieve a competitive advantage and improved employee engagement through an effective leadership function, augmented by a strong organizational culture (Jardon & Martínez-Cobas 2019); (Mohanty et al 2016). One of the most widespread definitions of culture is given by Edgar Shein “A pattern of shared basic assumptions that was learned by a group as it solved its problems of external adaptation and internal integration….,” Schein (2004) Culture may be perceived as a set of principles, values and attitudes that underpin an organization and which establish the foundation for the decision-making process. Literature provides several other interpretations of cultural paradigms and although none of these can be considered fully comprehensive, they offer further insight into this concept (Lumby et al., 2009).

Research Purpose

Since empirical studies on organisation culture and distributed leadership practices within small businesses in Malta are rather limited, this study attempts to address this gap and contribute to the academic body of knowledge on this subject area. Through this research study, a number of proposition statements stemming from the grounded data are formulated on the role that both distributed leadership and culture play in the prosperity or decline of small businesses.

Theoretical Foundations

Leadership and the Small Enterprise

Over recent years, the subject of leadership has attained significant prominence within the management field, with numerous researchers acknowledging that leadership behavior is a pivotal factor influencing organizational operations (Wu 2009; Zheltoukhova & Suckley 2014; O'Regan & Lehmann 2008; Laurentiu et al., 2017). Nevertheless, there appears to be a lack of cohesion among the various leadership models (Offord et al., 2016). The ontological perspective of leadership is undergoing continuous evolution (Khan et al., 2016), with researchers (Winston and Patterson 2006) positing that the definition of leadership will persist in evolving as scholars, and practicing leaders gain greater insight into the concept. This dynamic evolution, however, poses challenges for researchers striving to develop universally applicable leadership models.

Extant literature predominantly focuses on the interplay between leadership, culture, and performance within large organizations (Bass et al., 2003; Klein et al., 2013; Kumar & Kaptan, 2007; Arham et al., 2013). The reliance on studies centered on large enterprises potentially skews the understanding of leadership behaviors, as these organizations typically possess more resources, formalized structures, and distinct cultural dynamics compared to small enterprises. Consequently, extrapolating findings from large organizations to small enterprises might lead to inappropriate conclusions or strategies. Conversely, the examination of leadership behavior, particularly distributed leadership, within smaller enterprises remains scant (Francos & Matos, 2015). This lacuna suggests a critical area for further research, given that small enterprises exhibit unique characteristics that influence their leadership dynamics and operational models.

Distributed leadership, defined as an emergent group where two or more individuals share the roles and functions of leadership (Bolden, 2011; Gronn, 2002), has predominantly been studied within the context of large organizations. This assumption that small enterprises merely represent a scaled-down version of larger organizations is challenged by Hill et al. (2002), who contend that small enterprises possess distinctive characteristics that shape their operating models and present unique challenges (Hill et al., 2002)

Characteristics of Small and Large Enterprises

Smaller organizations tend to exhibit greater agility compared to larger ones due to their flatter hierarchical structures and less bureaucratic environments. However, this agility imposes additional responsibilities on the owner-manager, who must possess a diverse skill set to manage various organizational functions effectively. Within the context of small microenterprises, Mbunga et al. (2013) concluded that poor leadership, management, and entrepreneurship are key factors limiting growth. While a flatter structure may enhance agility and reduce formality, the increased leadership burden on the owner-manager could potentially impede agility due to overextension and burnout. This tension between agility and the multifaceted demands of leadership warrants further examination.

From a leadership influence perspective, various studies (Bridge & O’Neill 2017; Laurentiu et al., 2017) assert that leadership influence in small enterprises differs from that in larger organizations. In small enterprises, the owner exerts direct influence on employees, whereas in larger organizations, this influence is insulated by multiple management layers. In a stable business environment, an owner's provision of a compelling vision may be advantageous. However, in the current dynamic business landscape, employees in small enterprises may possess superior knowledge of technological advancements, commercial developments, and consumer behavior. Thus, delegating decision-making authority to competent employees could yield more effective results.

Distributed Leadership

Psychological or practical resistance by owner-managers to relinquish control can be problematic in a rapidly changing environment (Bridge & O’Neill 2017). Contrarily, Cooney (2005) contends that successful entrepreneurs often build teams around them or are part of a team, challenging the romantic notion of the entrepreneur as a lone hero. This concept of ‘shared leadership’ or ‘distributed leadership’ necessitates a paradigm shift in how leadership is perceived and practiced (Harris 2013). Distributed leadership, defined by Spillane (2013) as the systematic practice of interactions among leaders, followers, and the situation, diverges from traditional top-down management. In this model, influence and decision-making responsibilities are distributed among multiple individuals rather than centralized in a single leader. Bennet et al. (2003) identify three key principles of distributed leadership: leadership emanates from a network of individuals, there is openness to leadership parameters both within and beyond the organization, and expertise is distributed across many individuals rather than a select few.

However, implementing distributed leadership presents challenges. According to Harris (2013), key issues include organizational culture, structure, and physical distance. Recent studies corroborate that adopting distributed leadership necessitates a cultural shift from hierarchical to more collaborative practices, which may encounter resistance due to entrenched practices and attitudes (Hickey et al., 2022). Additionally, traditional organizational structures and internal distances, characterized by rigid hierarchies and bureaucratic barriers, can impede the adoption of distributed leadership. Effective implementation requires organizations to embrace more flexible, decentralized structures that facilitate shared decision-making and collective responsibility (MIT Sloan, 2022).

Defining Culture

Within organizations, culture is the tacit social structure influencing behavior. Edgar Schein defines culture as “a pattern of shared basic assumptions learned by a group as it solves its problems of external adaptation and internal integration” (Schein 2004). While this definition provides a comprehensive framework, its application to small enterprises warrants further scrutiny. The elements of external adaptation and internal integration manifest differently in small enterprises due to their size and resource constraints. Simplifying this concept, culture can be defined as the organizational norms and practices. Miller (2014) suggests that the stronger the identification with organizational values and purpose, the stronger the culture. When cultural norms align with employees' personal values, exceptional synergy towards organizational development is achieved (Groysberg et al., 2018). However, factors such as leadership style, communication practices, and reward systems also significantly influence cultural strength and coherence.

Within small enterprises, Blackburn (2003) warns that transcending culture from abstract to factual is challenging. In one study, Blackburn found that most owner-managers were either indifferent or explicitly distanced themselves from cultural notions. Understanding this attitude towards culture could provide insights into the practical difficulties of managing shared beliefs and values. Factors such as limited resources, prioritization of operational over strategic concerns, or a lack of understanding of cultural management merit further exploration.

Components of Culture

Organizational culture encompasses distinct yet interrelated components, including shared values, behavioral norms, historical recollections, and behavioral patterns (Homburg & Pflesser, 2000). Recent studies propose that culture can be characterized as bureaucratic, innovative, or supportive, with each category having both positive and negative effects on organizational effectiveness (Mohanty et al., 2016). These elements significantly influence individual and organizational behavior. Culture is perceived differently by various individuals within the organization, leading to the presence of a core culture and multiple sub-cultures as the enterprise develops (Mohanty et al., 2016). Understanding the structure and components of culture is crucial, as these intrinsic values underpin organizational procedures and practices (Hatch, 1993).

The Instrumentalization of Culture

When effectively leveraged by management, organizational culture can navigate the complexities of an enterprise. It can adapt the organization to emerging opportunities and bridge the gap between top management strategies and frontline employees' practical expertise. Tichy (1983) asserts that culture pervasively influences employees, organizational strategy, and key stakeholders. Smaller firms have a competitive edge over larger organizations in agility and adaptability. Therefore, culture becomes a critical element enabling small enterprises to remain nimble in their decision-making processes.

The Culture–Leadership Interplay

Extensive literature posits close connections between organizational culture and leadership performance (Brettel et al., 2015; Dabic et al., 2018; Fatima & Bilal, 2019; Jardon & Martínez-Cobas 2019; Cope et al., 2011; De Oliveira et al., 2015; Mohanty et al., 2016). However, there is a paucity of empirical work specifically within small enterprises situated in a small state such as Malta. These studies often fail to differentiate the unique constraints and opportunities in small enterprises compared to large organizations. Some works, such as the narrowly focused study by Jardon and Martinez-Cobas (2019) on small organizations, reference the interaction between leadership and culture through opposing perspectives: the functionalist approach, which sustains that leaders shape culture through their actions and behavior, and the anthropological perspective, which claims that culture shapes leadership (Jardon & Martínez-Cobas, 2019). Similar insights are offered by Mohanty (2016), who suggests that transactional leaders operate within the parameters of organizational culture, while transformational leaders reshape their organization’s culture to align with a new vision, shared beliefs, and practices

Critical Research Void

Despite the extensive theoretical foundations and empirical studies on leadership and culture in organizations, significant gaps remain in understanding these dynamics within the context of small enterprises in a small state such as Malta. Existing literature predominantly focuses on large organizations, whose resources, formal structures, and cultural dynamics differ substantially from those of small enterprises. This reliance on studies from large businesses can lead to inappropriate conclusions when applied to smaller enterprises, thereby underscoring a critical research gap.

Specifically, there is a scarcity of empirical work exploring the interplay between organizational culture and distributed leadership in small enterprises. The unique characteristics of small enterprises—such as resource constraints, a flatter hierarchy, and the direct involvement of owner-managers—necessitate tailored leadership models that address their specific challenges and opportunities. Distributed leadership, while extensively studied in larger organizations, needs further investigation in small enterprises to understand how its principles of shared decision-making and collective responsibility manifest in such environments.

Moreover, small enterprises often face a tension between maintaining agility and managing the multifaceted demands placed on owner-managers. The potential over-exertion of owner-managers, due to multiple and diverse responsibilities, may hinder the agility that is typically an advantage of smaller firms. This dynamic requires a deeper examination of how distributed leadership can alleviate some of these pressures and enhance organizational effectiveness without compromising the agility of small enterprises.

Another area requiring further exploration is the cultural shift necessary for adopting distributed leadership in small enterprises. Implementing distributed leadership involves transitioning from traditional hierarchical models to more collaborative and participative practices, which can encounter resistance and cultural inertia. Understanding the specific cultural, structural, and spatial barriers in small enterprises is crucial for developing comprehensive strategies that facilitate this shift.

The Small Enterprise–Macro Context

There seems to be a general agreement between economists and analysts that the economic health of a nation is dependent upon the performance of domestic enterprises, in particular SMEs. This is sustained by the OECD whereby their report stated that ‘SMEs play a key role in national economies around the world, generating employment, value-added and contribution to innovation’. This setting prevails within the EU where according to the online EU publication (

https://ec.europa.eu/growth/smes_en)

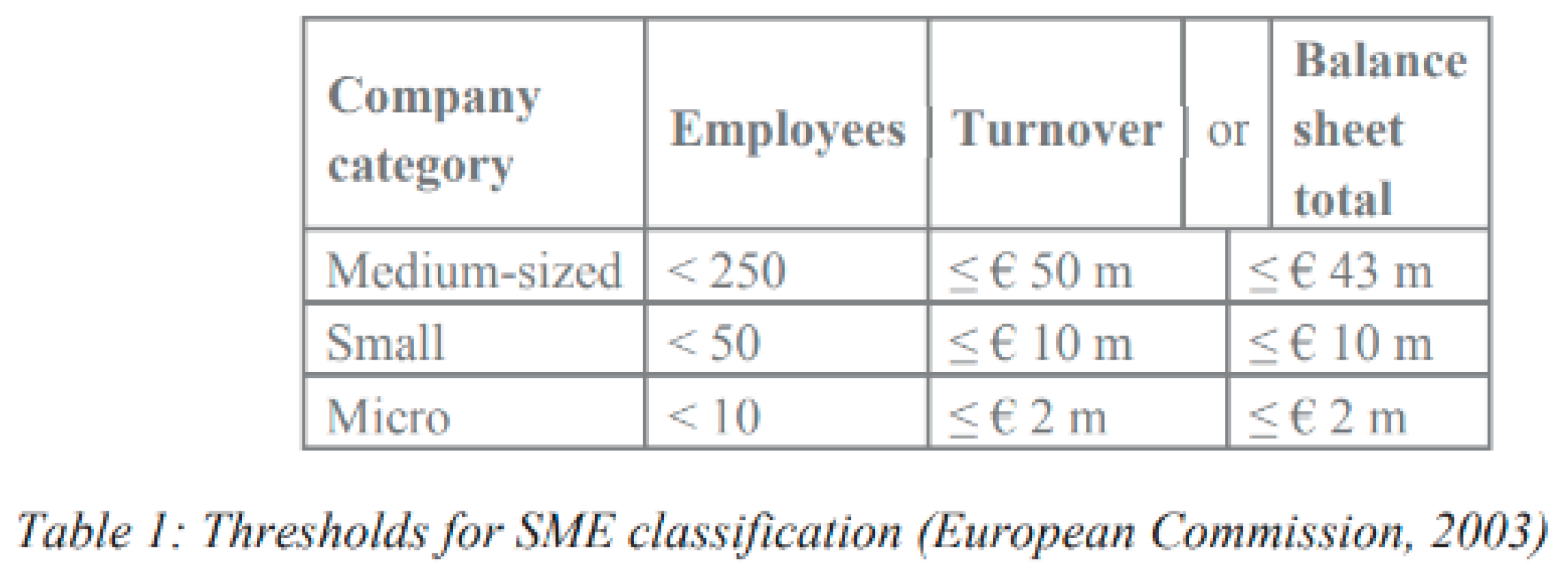

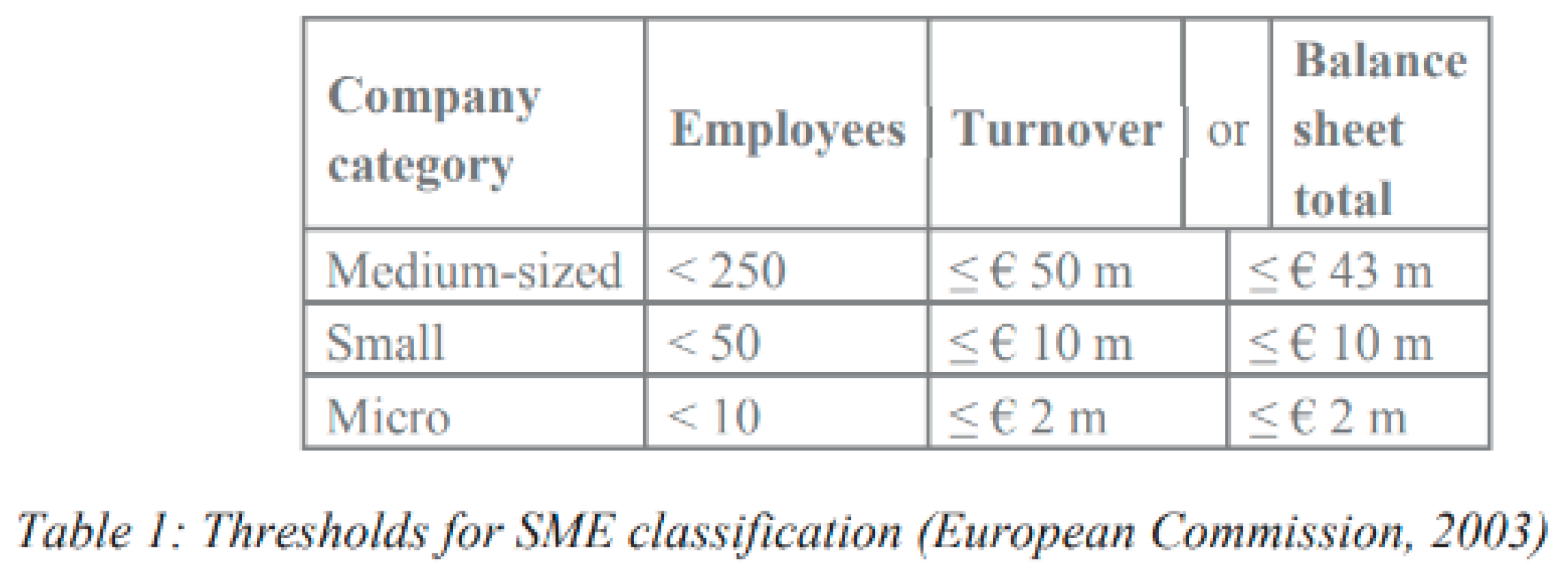

“Small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) are the backbone of Europe's economy. They represent 99% of all businesses in the EU. They employ around 100 million people, account for more than half of Europe’s GDP and play a key role in adding value in every sector of the economy” The European Commission (2003) defines SMEs based on criteria related to the number of employees and turnover or balance sheet total as outlined in Table 1:

The Small Enterprises in Malta

The European Commission fact sheet for the year 2021 outlines that Small Organizations in Malta amount to 2,163 or 6.6% of the total number of enterprises. These small organizations employ 26.5% of the total number of persons employed on the Island with an economic contribution of 1.8 Billion of a total Economic Value Added of 7.3 billion.

Despite the considerable influence they have on the country's economic model, there is a scarcity of empirical understanding regarding the behavior and performance of small organizations (Rizzo 2011). This limited insight into this area is not surprising as according to Curran and Blackburn (2001), several attempts at conducting research within the Small Enterprise realm turns out to be unreliable due to a lack of individualization of systematic fieldwork. Other limiting factors appear to be the proper sizing, accessibility and heterogeneity of the small enterprise sector. Adding to this, some small business owners seem to doubt the importance of academic research hence diminishing the applicability of theoretical propositions.

The Research Problem

Understanding how leadership styles and organizational culture impact small enterprises is essential for several reasons. First, small businesses often operate in highly volatile environments where leadership decisions can directly affect their survival and growth. Second, the close-knit nature of small firms means that cultural dynamics can significantly influence employee morale, engagement, and productivity.

This research study focuses on three key objectives aimed at finding an explanation for the core research question: it seeks to develop a profound understanding of leadership behavior; the key influencers of organizational culture; and to assess the relationship between these two elements in small businesses. Since empirical studies on organization culture and leadership practices within small businesses in Malta are rather limited, this study attempts to address this gap and contribute to the academic body of knowledge on this subject area.

The final purpose of this study is to develop an initial conceptual model that may provide a better understanding of the interplay between leadership and organizational culture, with a specific focus on small enterprises. The aim of this research is not limited to the exploration of the leadership approaches, styles and culture in small businesses but rather to appraise the leadership-culture phenomenon and how this impacts the ultimate strategic achievements of the organization. Through this research study, a number of proposition statements stemming from the grounded data are formulated on the role that both leadership and culture play in the prosperity or decline of small businesses.

Research Question and Objectives: How do leaders’ behavior within established small organizations in Malta influence organizational culture and its ramifications?

RO1: To obtain a deeper understanding of leadership behavior and style in small businesses in Malta

RO2: To assess the main influencers and components of organizational culture within small businesses

RO3: To seek and establish patterns of the interplay between leadership styles and organizational culture in small businesses

Methodology

Research in small enterprises necessitates a methodology that aligns with their unique characteristics, contexts, and the individuals operating within them. Adopting a naturalistic approach underpinned by a constructivist and interpretivist epistemology, this study utilizes grounded theory to explore the dynamics between leadership and organizational culture in small businesses. This philosophical stance acknowledges that individuals construct meaning through their experiences and interactions within their environment, leading to diverse viewpoints. Consequently, researchers' values and beliefs inevitably influence data interpretation, collection, and analysis (Charmaz, 2015). The researchers’ professional experience enriches the interpretation, reflexive processes, and analysis of the data.

Ontologically, the study embraces an idealistic stance, following Gill and Johnson’s (1991) ideographic viewpoint, which emphasizes theory development through inductive methods, qualitative data, and flexible structures. This approach enables the identification of patterns, categories, and themes from the data inductively, aligning with the management literature's advocacy for qualitative designs to address 'how' and 'why' questions (Eriksson & Kovalainen, 2016).

The primary goal is to develop a preliminary theoretical framework on how distributed leadership and organizational culture influence an organization's success or failure. grounded theory, as developed by Glaser and Strauss (1967), provides the methodological framework for this study. Originally intended for sociologists, Grounded theory has since been adopted across various fields, including management. This methodology’s appeal in management research lies in its ability to derive theory directly from qualitative data, making it more relevant and credible to practitioners (Shankar and Goulding, 2000; Goulding, 2002).

Grounded theory involves generating an abstract theory of a process or interaction grounded in data collected from participants. Although theoretical saturation is not achieved due to the limited sample size, the study presents an initial framework derived from the data. The process involves multiple stages of data collection, continuous comparative analysis, and theoretical sampling to refine and interrelate categories of information (Creswell, 2018). Induction of theory is achieved through successive comparative analyses, while abductive reasoning occurs at all stages of analysis, particularly during the constant comparative analysis of categories leading to theoretical integration (Charmaz, 2006). This iterative process ensures the derived theories accurately reflect reality (Strauss and Corbin, 2015) and contributes to deep exploration and framework development (Parker and Roffey, 1997).

Data Gathering, Analysis, and Coding

Following Charmaz and Thornberg’s (2021) guidelines, this study clearly outlines the methodology, including sample acquisition, participant selection, and the application of Grounded Theory and data collection methods. Rich data collection involves understanding participants' experiences, aligning with Glaser and Strauss’s (1967) emphasis on process and action, and the continuous pursuit to comprehend basic social and psychological processes.

Data were generated through twelve interviews with senior leaders and owners of established Maltese small enterprises, employing open-ended questions to elicit in-depth responses. Reflecting a constructivist and interpretivist philosophical position, the researchers engaged closely with participants during 'responsive interviewing' (Rubin and Rubin, 2005). Initial convenience sampling leveraged the researchers’ network, followed by purposive sampling to select participants with relevant characteristics and experiences. Theoretical sampling further refined the emerging concepts. Reflexive memoing throughout data generation and comparative analysis stimulated analytic depth.

Data analysis involved a rigorous coding process. Open coding, reviewing data at a granular level, ensured no significant categories were overlooked and facilitated category verification and saturation (Holton, 2007). Charmaz and Thornberg (2021) emphasize maintaining an open mind to data insights, ensuring codes fit the data rather than preconceptions. The iterative process of data collection and analysis informed subsequent data-gathering strategies, focusing on themes emerging from the data itself (Charmaz, 1995). Theoretical sampling, as described by Corbin and Strauss (2015), guided data collection to develop and understand key concepts, though conceptual and theoretical saturation was not achieved due to the limited number of interviews.

Analysis of Preliminary Research

The study investigates leadership behavior and cultural norms within Maltese small enterprises. The sample comprises twelve owner-managers from various industries, including IT, architecture, financial services, hospitality, and retail. Participants were selected based on their accomplishments, reputation, close professional relationship with the researchers, and high level of experience and academic background. Intensive interviewing, conducted as guided conversations, allowed participants to express their views on leadership and culture, providing profound insights for concurrent analysis. Ethical considerations and confidentiality were maintained through introductory letters and consent forms. Interviews, lasting twenty to forty minutes, were transcribed meticulously, with the transcription process facilitating deeper understanding and reflexive memoing by the researchers

Data Analysis Framework

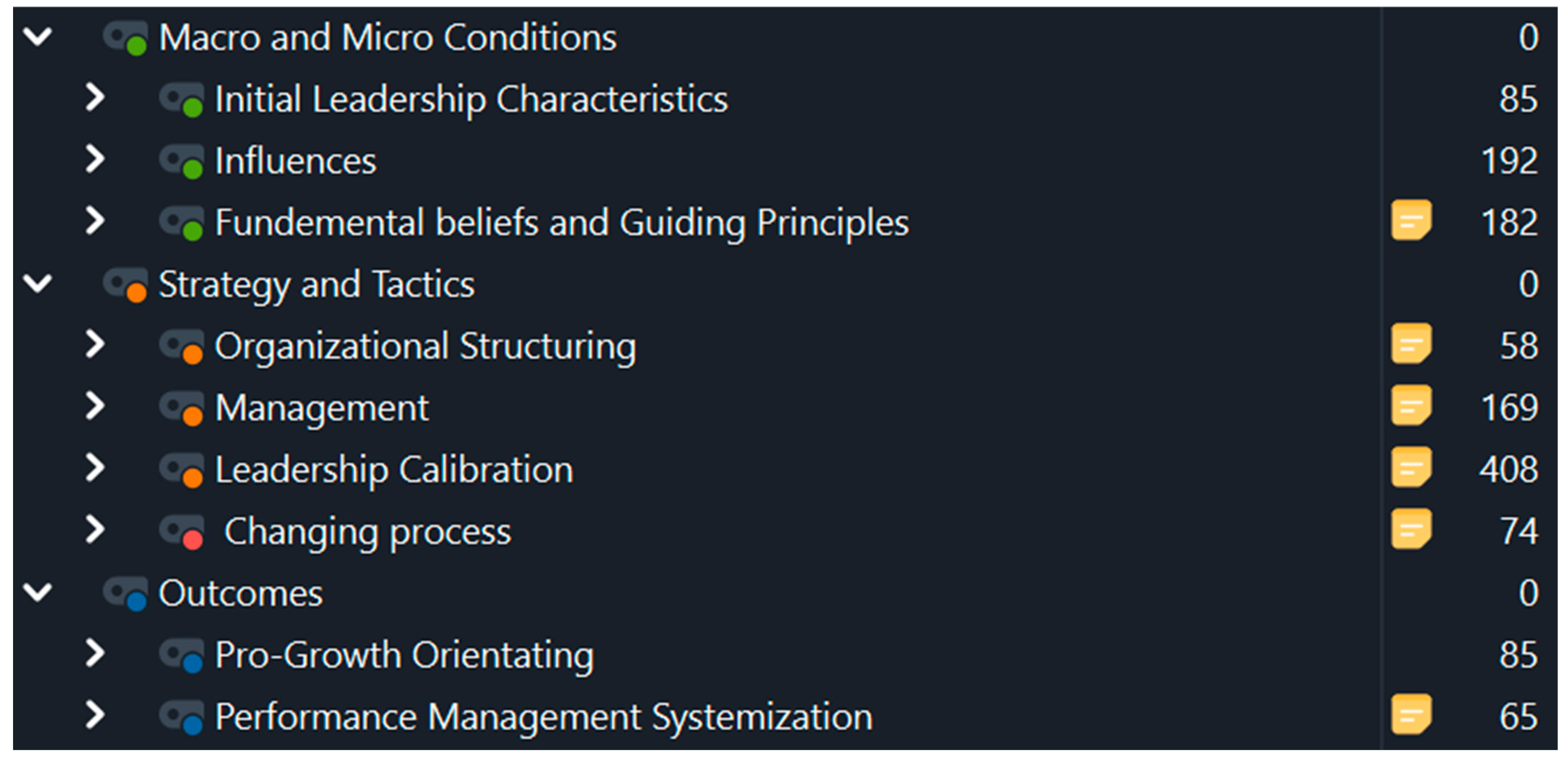

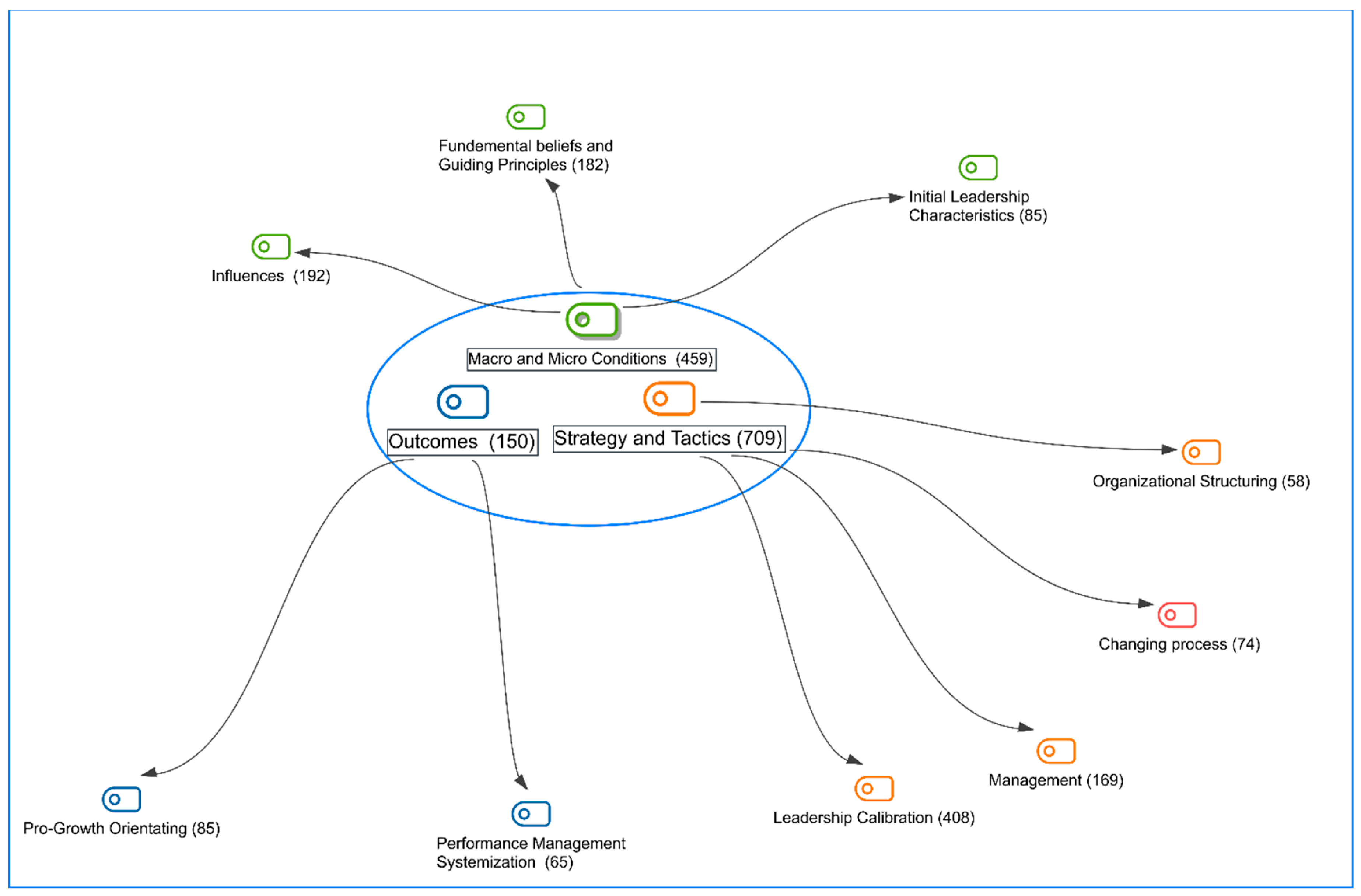

Qualitative data were analyzed by means of MAXQDA software. Preliminary coding was conducted via Microsoft excel however once data started accumulating, MAXQDA’s powerful data mapping functions allowed the researchers to process and articulate higher volumes of data. All transcribed word documents were imported into MAXQDA and each document was fragmented into numerous incidents which were relevant to the IN-VIVO coding framework. This process yielded five hundred and forty-four IN-VIVO codes and enabled the researchers to gain a profound insight into the participants’ business context. At this point, the researchers started conceptualizing the codes into themes and categories some of which had extended properties. The researchers adopted the classifying framework proposed by Corbin and Strauss (2015) in which categories are labeled as contextual conditions, actions and consequences. The inductive and abductive nature of the research analysis gradually shaped this framework into emerging key categories. Each transcribed document was analyzed again and coded segments were then linked to the respective category. This recursive process of contrasting data eliminates any possibility that the researchers would inadvertently contaminate data with any prejudice or bias. Figure 2a shows a snapshot of this framework.

Contextual conditions representing the initial the key aspects were gradually developed into Macro and Micro Conditions which shaped strategies and actions leading to outcomes. This was not observed as a linear process but rather as a processual one, where Macro and Micro Conditions (Context) the Strategies and Tactics (Actions) and Outcomes (Consequences) iteratively shape each other in an environment characterized by continuous change. Figure 2b below illustrates this interaction.

The findings from this preliminary research project offer a model that comprises the categories and key concepts of leadership and culture within Small Enterprises. The prevailing concepts provide a structure that explains the dynamics and perceptions of this phenomenon. Contextual conditions are determined by the type of culture and the interrelationship between leadership and culture. These conditions stimulate actions related to leadership style, management capabilities, structure and cultural change. The results of these actions become the prevailing consequences and outcomes which are mainly the implementation and effective use of performance management systems and incremental business growth.

Macro and Micro Contexts

The development of the leadership role into a function: A structured decision-making approach in established small organisations, becomes an important stage within the initial growth phases of an enterprise and a context that triggers actions for paradigm shifts to occur. This study shows that owner/managers of small organizations, recognize the fact, that as the small enterprise started growing, certain responsibilities had to be detached from the traditional leader’s role and shifted towards a separate function within an organizational structure to create a more participatory style of leadership. This change, which at times required additional costs related to human capital, was perceived as a necessary investment for the potential growth of the organziation. This participatory leadership approach was also supported by a transformational leadership style whereby, rather than taking action themselves, owner/managers preferred to coach and train key individuals to effectively make decisions and manage situations on their behalf. This indicates that in established Maltese Small organizations, formal and informal leadership are not incompatible or oppositional, but rather are different parts of leadership practice. .Within this context, it also transpires that the main challenges presented in the literature related to the application of distributed leadership within an organization were somehow overcome in the established small enterprises being reviewed in this study. There were a few contrasting views on the concept of shared leadership emerging from the perceived initial need to control and micro-manage each process however the same participant also expressed a desire to gradually transform the organziation into one where employees may become directly involved and share responsibilities and returns.

Leadership - Culture Interplay: The extensive examination of the connection between leadership and organizational culture holds significant importance in management literature. The analysis conducted so far on the data gathered during this research project has identified a functionalist perspective, positing that leadership shapes culture and invertedly that culture shapes leadership, aligning with an anthropological viewpoint. The majority of participants underscored the importance of preserving the current organizational culture while simultaneously encouraging new hires to either assimilate or exit. Additionally, several respondents highlighted the significance of recruiting individuals whose cultural inclinations align with the organization's, citing the facilitation of smoother organizational management. Conversely, most participants found it necessary to adjust their leadership approach as the organization expanded, embracing and integrating new cultural dynamics to foster business growth.. Overall, the interviews revealed a clear interaction between leadership and culture, impacting recruitment, assimilation, and organizational growth

Culture: The examination of the contextual themes of organizational culture was an important topic for the researchers to accomplish one of the main objectives set in the research question. An analysis of the prevailing cultural characteristics from the data gathered reveals that an entrepreneurial culture and a culture of innovation and experimentation were the most dominant aspects. The entrepreneurial culture was described as an environment in which risk-taking is not only tolerated but also a key component within the business process. Many respondents actually believe that this is an intrinsic trait (entrepreneurial). Closely linked to the Entrepreneurial culture is the innovation and experimentation inclination of most leaders of small Firms. All respondents showed that at various stages of the business lifecycle, the adoption of various creative initiatives were vital and these ranged from developing innovative software at the startup stage to 'pushing the boundary’ of the creative talents. It is however recognized that this approach yields mistakes and whilst there should be parameters set in place to define tolerance levels, employees still need to be held somehow accountable. Culture is viewed as a dynamic component within the organization. Respondents highlighted the importance of implementing interventions to shape the organization's culture, especially during leadership change or development. Additionally, many participants illustrated how culture underwent transformation as the organization expanded. These significant cues can offer insights into the gradual integration of a distributed form of leadership within the enterprise culture. The initially 'Top-Down' leadership culture evolved into one that allowed the emergence of multiple leaders. The data collected from participants indicated that this shift occurred because leaders acknowledged the necessity of shared leadership for the fostering of growth. This recognition likely sparked a strong willingness to embrace change, surpassing the desire to maintain strict control over the organization. The data also showed how culture required constant cultivation, protection and shaping to remain in congruence with the changing environment, the organization's vision and human resources’ motivational triggers. In fact, particularly from a people's perspective, all interviewees emphasized on this aspect. Matters such as adequate remuneration and low staff turnover ratios and an approach whereby the leader strives at achieving ' dedication, trustworthiness and reciprocal respect' all indicate a strong commitment at fostering excellent relationships with staff. The majority of participants have expressed their readiness to elevate their connections to a personal level when needed, intervening and providing support for staff in private matters. This reflects a strong sense of trust, openness, and respect in the relationships.

Small Firm Strategies and Tactics

Leadership in action: In terms of leadership, several respondents were very receptive to the fact that at a certain point, the company needed to evolve from its existing operational paradigm. Sensing either potential stagnation in the decision-making process or the need for a more effective leadership function due to contextual change, owner-managers took action and sought additional high-level assistance through consultants or attracting better human capital and empowering people to share in the leadership function within the organization. This occurred despite initial apprehensions about letting go of even very basic functions. Many respondents explained how their role changed into one that became primarily concerned with motivating people whilst drifting away from the centralized leadership role of the owner-manager which some described as being an inefficient structure. These insights underscore the importance of distributed leadership, delegation, and empowerment in navigating organizational change and growth whilst acknowledging that there needs to be more tolerance for errors when involving more people in leadership and decision-making.

Organizational structuring: All Leaders explained that at some point, their respective enterprise required actions to set up articulated reporting systems and a structure. This action provided evidence of a shared leadership purpose, which seemingly encounters less resistance in small organizations due to its size and limited complexity. The most basic setup involved the founder-leader assuming a less operational role, focusing on strategic aspects of the organization whilst delegating day-to-day tasks to other senior employees or family members. All interviewees sustained that the absence of delegation is a key growth limiting factor. From a leadership perspective, the formulation of a structure meant a shift in Leadership style and culture. This shows that as their organizations evolved, different leadership capabilities were required. An array of management skill-set to plan, organize and control was also necessary whilst organizational culture evolved in a way in which decisions were no longer taken exclusively by one person.

Management actions: Data from the participants clearly shows that general management competencies are very important attributes that founder-leaders should possess to navigate successfully the business environment. Skills such as delegating, organizing, planning and coordinating are necessary during the initial stages as well as when the organization starts to evolve and grow. A basic financial and marketing background seems to be of critical importance, especially during the initial stages of the organization. Human resources management appeared to be a key aspect with all interviewees sharing different experiences in people management. The data gathered from the interviews also showed that leaders appreciate the importance of investing time with employees to support them in their problems whilst investing resources in the growth, learning and development of employees. All participants explained (in their own way) that at some point, responsiblising key employees and delegating important tasks become an inevitable process. These management interventions help to shape entrepreneurs of small enterprises into more ‘mature leaders’ (Thorpe et al 2006) who are able to disseminate shared vision, effectively delegate tasks and recognize that the realization of vision requires the contribution from other people. This open management style together with the willingness to relinquish some control are important elements at fostering forms of distributed entrepreneurial leadership in small enterprises.

Consequences and Outcomes

Growth Limiting Factors: Participants commented about some factors which in their opinion limit their organization's growth potential. One of the main challenges is the effective delegation of tasks within the organization's structure. When this is not managed properly, leaders are forced to do certain tasks themselves at the cost of sacrificing focus on general organizational development. The lack of skilled human resources appears to be another major factor hindering further enterprise expansion. Leaders are trying to mitigate this risk by investing in their people to retain talent and optimize productivity, but certain growth strategies cannot materialize without additional resources.

An Architecture of Performance Management Systems: The results from the actions and strategies outlined by the respondents suggest that performance management and a high-performance culture are central elements of the leadership and culture interaction. All participants explained extensively the importance of performance measurement to create a balanced culture between the organization's stakeholders. The architecture of the various systems implemented to manage performance has common characteristics which generate timely, meaningful and accurate information for effective decision-making. These systems are used to manage sales processes, reward and remuneration mechanisms, customer service levels, productivity, efficiency and project costs. Performance management systems support the distributed leadership function by facilitating the management of resources and delegation, enabling leaders of the small enterprise to attend to other important strategic aspects of the organization. These systems also contribute to shaping organizational culture by creating an environment in which objectives, accountability and responsibilities ('Key Performance Indicators) are more clearly defined, communicated, endorsed and executed.

All participants expressed a desire for more growth. Despite some limiting factors and a general approach towards cautious incremental growth, all respondents are well prepared to evaluate and capture new opportunities which would contribute positively towards the prosperity of their business enterprise.

A Conceptual Model Emanating from Data

The researchers’ aim is to present a theoretical model that is grounded in the data gathered during the interviews, which model possesses an explanatory capacity of the phenomenon being studied. The definition of theory according to Birks and Mills (2015) is “an explanatory scheme comprising a set of concepts related to each other through logical patterns of connectivity”. A Grounded Theory is not simply a set of categories that are connected together into a theory (Glaser and Strauss 1967), proper theoretical integration is the result of high-level analytical thinking and advanced conceptualization techniques.

The researchers applied analytical thinking at the early stages of the data-gathering process by extrapolating elements of the data to which the researchers were theoretically sensitive and which were also relevant to the developing theory. Theoretical sensitivity and the ability of the researchers to conceptualize the leadership – culture phenomena to the emerging abstract themes, was augmented by a preliminary literature review, data analysis and the researcher’s professional experience in the field of study. The analytical description of these extracts is recorded in the memos which were disseminated throughout the coding phases. Conceptual and Theory development determined the sampling trajectory and as more data was being populated, analyzed, and contrasted, early relationships started forming and concepts developing. The researchers finally connected the developing concepts into an emergent conceptual framework built on the foundation of a preliminary core category. “The core category captures in a few words the major theme or the essence of the study and enables all the other categories and concepts to be integrated around it to form the theoretical explanation of why and how something happens” Corbin and Strauss (2015)

Data gathered from the interviews, which shaped the themes and categories, led to the formulation of a number of propositions around the concept of Leadership and Culture with particular emphasis on the distributed and shared leadership style.

Organizational culture in small enterprises plays an important role in organizational performance, it influences distributed leadership effectiveness and connects the various dimensions of organizational behavior.

Leaders in established small enterprises in Malta maintain a centralized transformational and transactional leadership role during the embryonic stages of the enterprise and gradually develop the leadership role into a distributed and shared leadership function through formal structures, systems, and continuous support.

Management competencies are an essential quality for leaders of established enterprises, to effectively formulate an architecture of systems and ensure that mechanisms are in place to manage performance, define accountability and sustain a broader distributed leadership approach at the various stages of enterprise development.

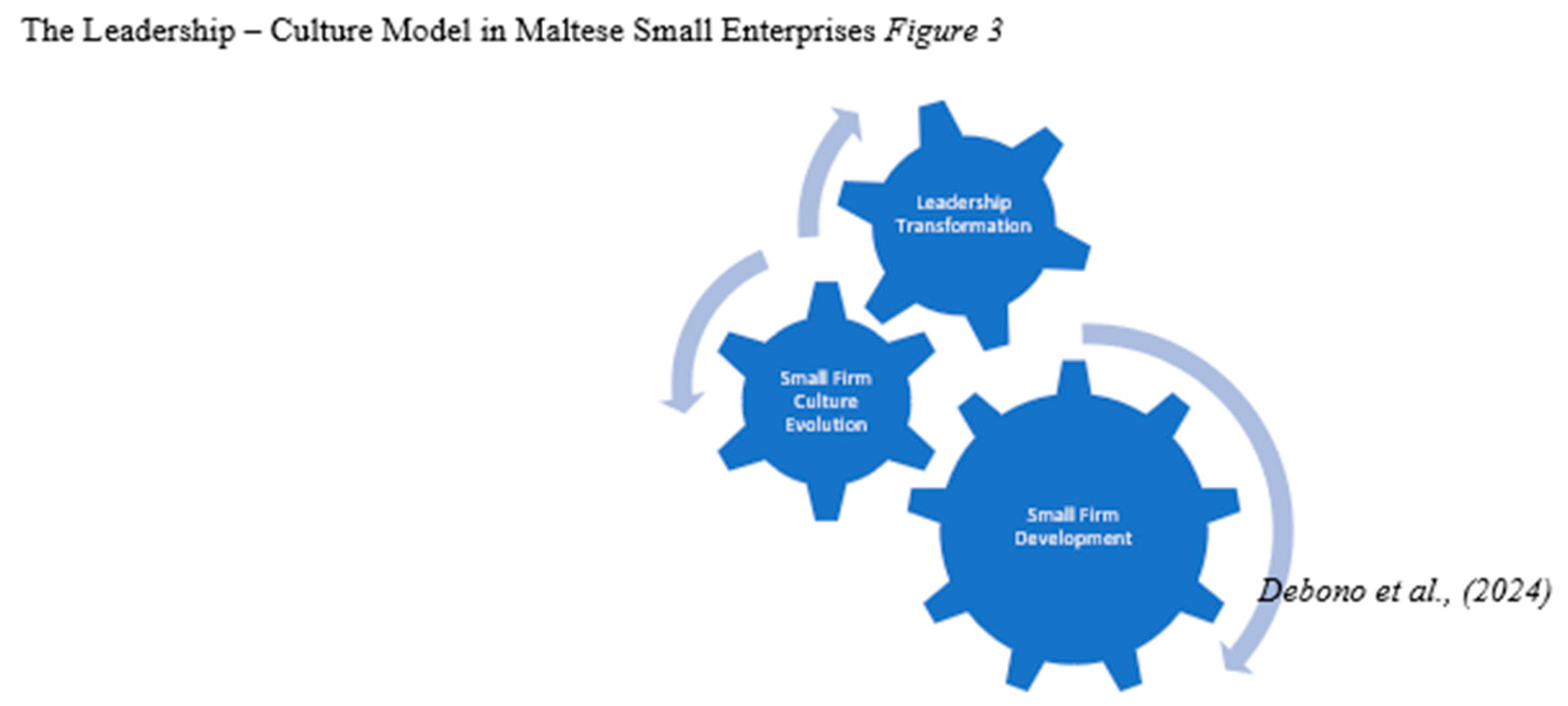

Figure 3 below is an illustration showing that Leadership and Culture in established small enterprises are cohesive elements and behave in a congruent manner throughout the various stages of enterprise development.

The above key concepts may be summarized into an emerging substantive conceptual framework which proposes that leaders in established small organizations within a small state like Malta shape their enterprise culture to support their organizational goals, whilst the evolution of an internal culture has a direct influence on the effectiveness of leaders which often entails the development of a style into one which is less centralized. Leadership and Culture are closely intertwined and are dynamic elements in the context of a business environment dominated by constant change.

Research Contribution

Implications for Practice

This research contributes to the literature on leadership and organizational culture in small enterprises, particularly in the context of Malta where such studies are scarce. By providing an initial exploration of these phenomena and their impact on organizational behavior, this paper lays the groundwork for further inquiry into this important area.

Development of Leadership Functions and Organizational Growth

Leadership Structuring: As small enterprises transition from their embryonic stages to more established phases, it is imperative for leaders to formalize decision-making structures. This involves shifting from a centralized leadership model to a more distributed and participatory approach. Leaders should strategically delegate responsibilities, thus promoting a more inclusive leadership model that fosters organizational growth. This structured delegation not only facilitates the scalability of the enterprise but also empowers key individuals, enabling them to take on decision-making roles that were traditionally reserved for the owner/manager. The practical implication here is that small firms should invest in leadership development programs that emphasize the importance of coaching, mentoring, and empowering employees to assume leadership roles.

Leadership and Organizational Culture Interplay

Cultural Integration and Adaptation: The interplay between leadership and organizational culture is pivotal in shaping the direction and effectiveness of leadership practices. Leaders in small enterprises should actively cultivate an organizational culture that is conducive to distributed leadership. This involves not only preserving core cultural values but also adapting to new cultural dynamics as the organization grows. Recruitment strategies should prioritize cultural fit, ensuring that new hires can assimilate into the existing culture or, if necessary, facilitate cultural evolution. In applied business practice, organizations should implement cultural assimilation programs for new employees and regularly assess the alignment between leadership practices and the evolving organizational culture.

Innovation and Entrepreneurial Culture

Fostering a Culture of Innovation: This study highlights the significance of an entrepreneurial culture that embraces risk-taking and experimentation. Leaders should create an environment where innovation is encouraged, and mistakes are viewed as learning opportunities within defined parameters. This culture of innovation is essential for sustaining long-term growth and competitiveness. In practical terms, small enterprises should establish innovation frameworks that allow for controlled experimentation, with clear guidelines on accountability and performance expectations.

Strategic Delegation and Management Competencies

Enhancement of Management Competencies: As small enterprises grow, the need for advanced management competencies becomes more pronounced. Leaders should focus on developing skills in delegation, planning, organizing, and coordinating, which are essential for navigating the complexities of organizational growth. Leadership development programs within small enterprises should include training in these competencies, with an emphasis on the strategic delegation of tasks and responsibilities to ensure sustained growth and the effective implementation of distributed leadership.

Addressing Growth-Limiting Factors

Mitigating Growth Constraints through Strategic Resource Allocation: The research identifies key growth-limiting factors, such as ineffective delegation and a lack of skilled human resources. To overcome these constraints, leaders should focus on optimizing their organizational structures and investing in human capital. This includes identifying and nurturing talent within the organization, as well as recruiting externally when necessary. The practical implication is that small enterprises should establish strategic talent management and resource allocation plans to address these growth-limiting factors proactively.

The study offers practical insights for leaders of small enterprises by elucidating leadership behaviors observed in established organizations. Through applied cases, it demonstrates how the abstract concept of culture can be translated into a practical instrument that supports leadership and organizational development. This not only enriches the understanding of leadership dynamics but also provides tangible strategies for implementation.

Methodological Contribution

Methodologically, the adoption of Grounded Theory methodology showcases its efficacy in exploring complex management phenomena. By employing this approach, the researchers were able to gather rich descriptions and develop an explanatory framework, highlighting its applicability in studying nuanced organizational dynamics.

Implications for Policy and Theory

This research also holds significant implications for policymakers, academic researchers and institutions involved in supporting small businesses. By providing insights into distributed leadership and cultural influences on organizational effectiveness, it offers a basis for informed policy formulation and support mechanisms.

The conceptual model emerging from this study serves as a foundation for designing more targeted policies that cater to the unique needs of small enterprises. By understanding the intricacies of leadership dynamics and cultural contexts, policymakers can develop interventions that foster a conducive environment for small business growth and sustainability. Additionally, academic researchers can use these findings to further refine theoretical frameworks and empirical studies in the field, contributing to ongoing scholarly dialogue and knowledge advancement.

Limitations

Whilst the design of this research project has enabled focus on leadership and culture within small enterprises at a micro level, this approach has limitations in assessing macro level phenomena, the broader economic and social factors which may be impacting the small enterprise. Furthermore, the researchers’ philosophical stance to construct reality based on the participants own experiences, may limit the production of generalized findings on the subject area.

As previously stated, full conceptual and theoretical saturation could not be achieved due to the limited scale of the study so far. However, further densification of the key concepts through theoretical sampling will lead to the complete integration of a theoretical model emanating from data.

Recommendations for Future Research

Once the grounded theory model on Small enterprises leadership and culture is fully developed, this could be suggested for evaluation in other small states in order to assess its geographical relevance. Additional viewpoints, for example, the employees’ may be added to broaden the conceptual perspective and further strengthen the theoretical model.

References

- AQUILINA, R., 2014. IT strategizing of small firms in Malta: a grounded theory approach. Robert Gordon University, PhD thesis.

- Arham, A.F., 2014. Leadership and performance: The case of Malaysian SMEs in the services sector. International Journal of Asian Social Science, 4, pp.343-355. Retrieved from http://www.aessweb.com/journal/5007.

- Arham, A.F., Boucher, C. & Muenjohn, N., 2013. Leadership and entrepreneurial success: A study of SMEs in Malaysia. World Journal of Social Sciences, 3(5), pp.117-130. Retrieved from http://www.wjsspapers.com/.

- Bartlett, D. & Payne, S., 1997. Grounded theory: its basis, rationale and procedures. In: G. McKenzie, J. Powell & R. Usher, eds. Understanding social research: perspectives on methodology and practice. London: Falmer Press.

- Bass, B.M., Avolio, B.J., Jung, D.I. & Benson, Y., 2003. Predicting unit performance by assessing transformational and transactional leadership. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(2), pp.207-218.

- Bennett, N., Wise, C., Woods, P. & Harvey, J., 2003. Distributed Leadership. Nottingham: National College for School Leadership.

- Birks, M. & Mills, J., 2015. Grounded theory: A practical guide. 2nd ed. London: Sage.

- Blackburn, R.A., Hart, M. & Wainwright, T., 2013. Small business performance: Business, strategy and owner-manager characteristics. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 20(1), pp.8–27. [CrossRef]

- Bolden, R., 2011. Distributed Leadership in Organizations: A Review of Theory and Research. International Journal of Management Reviews, 13(3), pp.251–269. [CrossRef]

- Brettel, M., Chomik, C. & Flatten, T.C., 2015. How organizational culture influences innovativeness, proactiveness, and risk-taking: fostering entrepreneurial orientation in SMEs. Journal of Small Business Management, 53(4), pp.868-885.

- Bridge, S. & O’Neill, K., 2017. Understanding Enterprise: Entrepreneurs and Small Business. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. https://books.google.com.mt/books?id=o_ZGEAAAQBAJ.

- Charmaz, K., 1991. Good days, bad days: The self in chronic illness and time. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press.

- Charmaz, K., 1995. Grounded Theory. In: J.A. Smith, R. Harre & L. Van Lagenhove, eds. Rethinking methods on psychology. London: Sage, pp.26-49.

- Cooney, T.M., 2005. Editorial: what is an entrepreneurial team? International Small Business Journal, 23, pp.226–235.

- Cope, J., Kempster, S. & Parry, K., 2011. Exploring Distributed Leadership in the Small Business Context. International Journal of Management Reviews, 13(3), pp.270–285. [CrossRef]

- Corbin, J. & Strauss, A., 2015. Basics of Qualitative Research. 4th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Creswell, J., Hanson, W.E., Clark Plano, V.L. & Morales, A., 2007. Qualitative Research Designs: Selection and Implementation. The Counseling Psychologist, 35(2), pp.236-264.

- Dabic, M., Lažnjak, J., Smallbone, D. & Švarc, J., 2018. Intellectual capital, organisational climate, innovation culture, and SME performance. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 26(4), pp.522-544.

- De Oliveira, J., Escrivão, E., Nagano, M.S., Ferraudo, A.S. & Rosim, D., 2015. What do small business owner-managers do? A managerial work perspective. Journal of Global Entrepreneurship Research, 5(1), p.19. [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, P. & Kovalainen, A., 2016. Qualitative methods in business research. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Fatima, T. & Bilal, A.R., 2019. Achieving SME performance through individual entrepreneurial orientation: an active social networking perspective. Journal of Entrepreneurship in Emerging Economies, 12(3), pp.399-411.

- Franco, M. & Matos, P.G., 2013. Leadership styles in SMEs: a mixed-method approach. Springer Science+Business Media, New York.

- Gill, J. & Johnson, P., 1991. Research Methods for Managers. London: Paul Chapman Publishing.

- Glaser, B.G. & Strauss, A.L., 1967. The discovery of grounded theory. 3rd ed. New Brunswick: Aldine Transaction.

- Goulding, C., 2002. Grounded theory: A practical guide for management, business and market researchers. London: Sage Publications.

- Groysberg, B., Lee, J., Price, J. & Cheng, J.Y.-J., 2018. Corporate Culture. Harvard Business Review, February, pp.2-8.

- Gronn, P., 2002. Distributed Leadership. In: K. Leithwood, et al., eds. Second International Handbook of Educational Leadership and Administration. Dordrecht: Springer, pp.653-696. [CrossRef]

- Harris, A., 2013. Distributed Leadership: Friend or Foe? Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 41(5), pp.545–554. [CrossRef]

- Harris, A. & DeFlaminis, J., 2016. Distributed leadership in practice: Evidence, misconceptions and possibilities. Management in Education, 30(4), pp.141–146. [CrossRef]

- Hatch, M.J., 1993. The Dynamics of Organizational Culture. The Academy of Management Review, 18(4), pp.657–693. [CrossRef]

- Hickey, N., Flaherty, A. & Mannix McNamara, P., 2022. Distributed Leadership: A Scoping Review Mapping Current Empirical Research. Societies, 12(1), p.15. [CrossRef]

- Hill, J., Nancarrow, C. & Tiu Wright, L., 2002. Lifecycles and crisis points in SMEs: a case approach. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 20(6), pp.361-369. [CrossRef]

- Holton, J.A., 2007. The coding process and its challenges. In: A. Bryant & K. Charmaz, eds. The SAGE handbook of grounded theory. London: Sage, pp.265-289.

- Homburg, C. & Pflesser, C., 2000. A Multiple-Layer Model of Market-Oriented Organizational Culture: Measurement issues and performance outcomes. Journal of Marketing Research, 37(4), pp.449-462.

- Jardon, C.M. & Martínez-Cobas, X., 2019. Leadership and Organizational Culture in the Sustainability of Subsistence Small Businesses: An Intellectual Capital-Based View. Sustainability, 11(12), p.3491. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, P., 2015. Evaluating qualitative research: past, present and future. Qualitative Research in Organizations and Management: An International Journal, 10(4), pp.320-324.

- Khan, Z.A., Nawaz, A. & Khan, I., 2016. Leadership Theories and Styles: A Literature Review. Journal of Resources Development and Management, 16, pp.1-7. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/293885908.

- Klein, A.S., Cooke, R.A. & Wallis, J., 2013. The impact of leadership styles on organizational culture and firm effectiveness: An empirical study. Journal of Management & Organization, 19(3), pp.241-254.

- Kumar, C.R. & Kaptan, S.S., 2007. The Leadership in Management: Understanding Leadership Wisdom. New Delhi: APH Publishing.

- Lumby, J., & Foskett, N. 2009. Leadership and culture. In International handbook on the preparation and development of school leaders (pp. 43-60). Routledge.

- Mbunga, K., Mbunga, M., Wangoi, M., & Ogada, J. 2013. Factors affecting the growth of micro and small enterprises: A case of tailoring and dressmaking enterprises in Eldoret. International Journal of Business and Social Science, 4(5).

- Miller, J. 2014. Keeping culture, purpose and values at the heart of your SME. London: Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development.

- MIT Sloan Management Review. 2022. Why distributed leadership is the future of management.

- Mohanty, A., Dash, M., & Pattnaik, S. 2016. Study of organization culture and leadership behaviour in small and medium-sized enterprises.

- Offord, M., Gill, R., & Kendal, J. 2016. Leadership between decks: A synthesis and development of engagement and resistance theories of leadership based on evidence from practice in Royal Navy warships. Leadership and Organization Development Journal, 37(2), 289-304. [CrossRef]

- O'Regan, N., & Lehmann, U. 2008. The impact of strategy, leadership, and culture on organisational performance: A case study of an SME. International Journal of Process Management and Benchmarking.

- Parker, L.D., & Roffey, B.H. 1997. Methodological themes: Back to the drawing board: Revisiting grounded theory and the everyday accountant’s and manager’s reality. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal, 10(2), 212-247.

- Rizzo, A. 2011. Strategic orientation and organizational performance of small firms in Malta: A grounded theory approach. Retrieved from http://openair.rgu.ac.uk.

- Schein, E.H. 2004. Organizational culture and leadership (3rd ed.). John Wiley & Sons.

- Shankar, A., & Goulding, C. 2000. Interpretive consumer research: Two more contributions to theory and practice. Qualitative Marketing Research: An International Journal, 4(1), 7-16.

- Spillane, J. 2013. The practice of leading and managing teaching in educational organisations. In Leadership for 21st Century Learning, Centre for Educational Research and Innovation, OECD Publishing.

- Strauss, A. 1987. Qualitative analysis for social scientists. Cambridge University Press, New York.

- Thorpe, R., Gold, J., Holt, R., & Clarke, J. 2006. Immaturity: The constraining of entrepreneurship. International Small Business Journal, 24, 232-252.

- Tichy, N. 1983. The essentials of strategic change management. Journal of Business Strategy, 3(4), 55-67. [CrossRef]

- Turner, J., & Baker, A. 2018. European Journal of Training and Development, 42(7/8).

- Winston, B. E., & Patterson, K. 2006. An integrative definition of leadership. International Journal of Leadership Studies, 1, 6-66.

- Wu, F.Y. 2009. The relationship between leadership styles and foreign English teachers' job satisfaction in adult English cram schools: Evidence in Taiwan. The Journal of American Academy of Business, 14(2), 75-82.

- Zheltoukhova, K., & Suckley, L. 2014. Hands-on or hands-off: Effective leadership and management in SMEs. London: Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development.

- Xhemajli, A., Luta, M., & Neziraj, E. (2022). Applying distributed leadership in micro and small enterprises of Kosovo. WSEAS Transactions on Business and Economics, 19, 1860-1866. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).