Submitted:

10 May 2024

Posted:

14 May 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis (AIS)

1.2. Body Representations in AIS Patients

1.3. The Assessment of Body Image

1.4. Cognitive-Behavioral (CBT) Interventions for Body Image Disorders in AIS Patients

1.5. Study Objectives

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Study Design

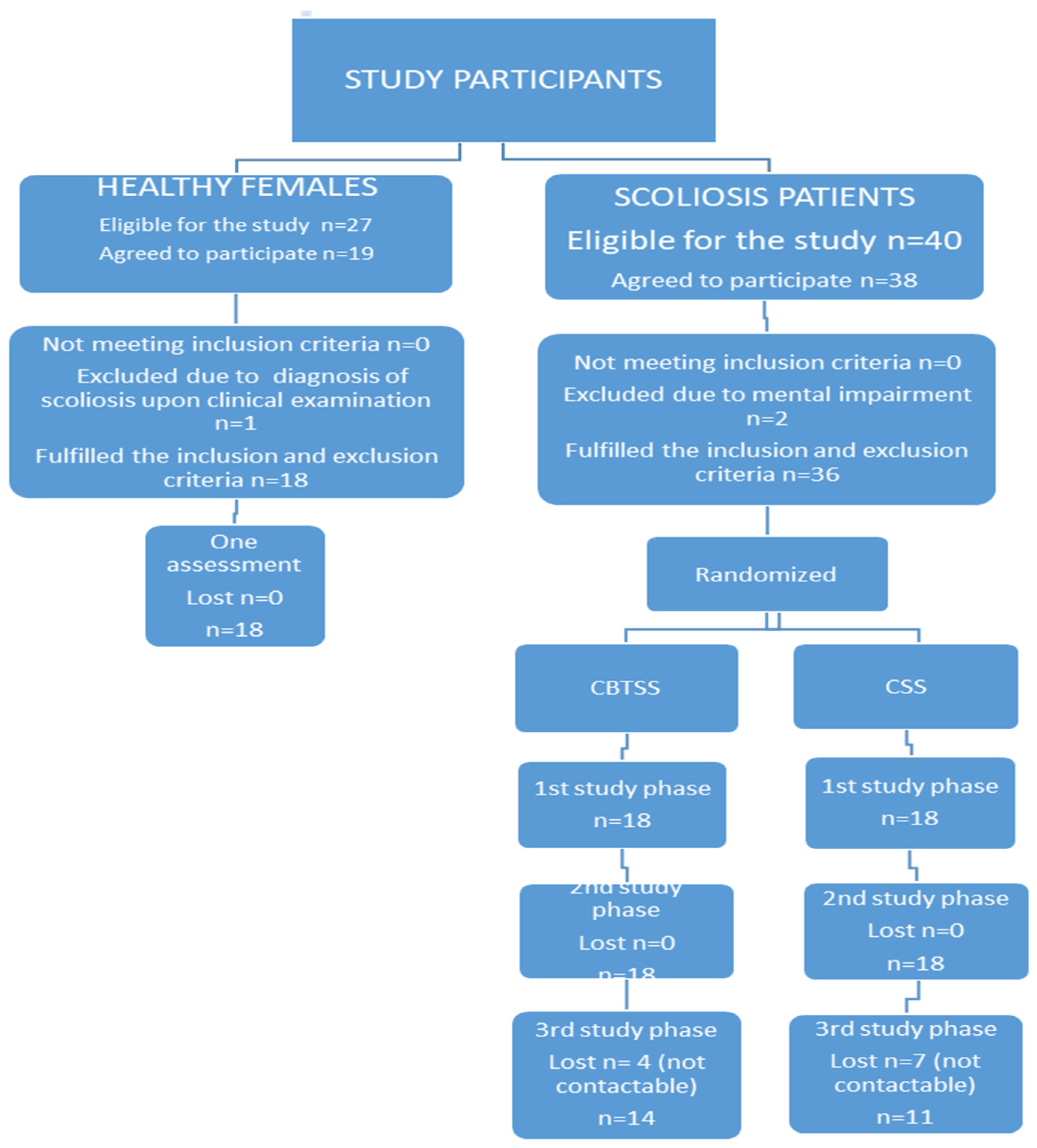

2.2. Recruitment to the Study

2.2.1. CBTSS and CSS

2.2.2. Healthy Female Sample

2.3. Enrolment Process in CBTSS, CSS and HFS

2.4. The CBT Intervention Content for the CBTSS (Experimental Group)

2.5. Analyzed Data

2.5.1. Socio-Demographic Data (CBTSS, CSS, HFS)

2.5.2. Radiological and Clinical Data (CBTSS, CSS)

2.5.3. Body Image (CBTSS, CSS, HFS)

2.5.3.1. Paper-Based Scales. Adolescents Were Assessed Using the Polish Versions of the Spinal Appearance Questionnaire (SAQ for Patients) [35], and Body Esteem Scale (BES) [40]

2.5.3.2. VR Tasks

2.5.4. Mental Health

2.6. Data Analyses and Processing Methods

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Study Samples

3.2. Descriptive Statistics of Study Measures

3.2.1. Body Image

3.2.1.1. Paper-Based Scales

3.2.1.2. VR Tasks

3.2.2. Mental Health

3.3. Comparative Analyses

3.3.1. Longitudinal Analyses

3.3.2. Cross-Sectional Analyses

4. Discussion

4.1. The Longitudinal Examination of Body Representation in and Mental Health in AIS

4.3. The Significance of CBT Intervention in AIS Patients (Cross-Sectional Analyses)

4.4. Strengths and Limitations of the Current Study

4.4. Future Research Implications

4.5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Weinstein, S.L. Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: prevalence and nature history. In: The paediatric spine: principle and practice. Weinstein, S.L, Editor; LWW, New York, USA, 1994, 463-78.

- Chung, N., Cheng, Y.H., Po, H.L., Ng, W.K., Cheung, K.C., Yung, H.Y., et al. Spinal phantom comparability study of Cobb angle measurement of scoliosis using digital radiographic imaging. J Orthop Translat. 2018, 15, 81–90. [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, T.P., Juzwa, W., Filipiak K,, et al. Quantification of the asymmetric migration of the lipophilic dyes, DiO and DiD, in homotypic co-cultures of chondrosarcoma SW-1353 cells. Mol Med Rep. 2016, 14, 4529-4536. [CrossRef]

- Glowacki, M., Ignys-O’Byrne, A., Ignys, I., Wroblewska, K. Limb shortening in the course of solitary bone cyst treatment--a comparative study. Skeletal Radiol. 2011, 40, 173-179. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lehmann T.P, Juzwa, W., Filipiak K, et al. Quantification of the asymmetric migration of the lipophilic dyes, DiO and DiD, in homotypic co-cultures of chondrosarcoma SW-1353 cells. Mol Med Rep. 2016, 14, 4529-4536. [CrossRef]

- Głowacki, M. Wartość wybranych czynników prognostycznych w leczeniu operacyjnym skoliozy idiopatycznej, 1st. ed., Ośrodek Wydawnictw Naukowych, Poznan, Poland, 2002.

- Wong, A.Y.L., Samartzis, D., Cheung, P.W.H., Cheung, J.P.Y. How Common Is Back Pain and What Biopsychosocial Factors Are Associated With Back Pain in Patients With Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2019,477,676–86. [CrossRef]

- Clayson, D., Luz-Alterman, S., Cataletto, M.M., Levine, D.B. Longterm psychological sequelae of surgically versus nonsurgically treated scoliosis. Spine 1987, 12, 983-6. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Auerbach, J.D., Lonner, B.S., Crerand, C.E., et al. Body image in patients with adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: validation of the Body Image Disturbance Questionnaire—Scoliosis Version. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 2014, 96, e61. [CrossRef]

- Misterska, E., Glowacki, M., Harasymczuk, J. Personality characteristics of females with adolescent idiopathic scoliosis after brace or surgical treatment compared to healthy controls. Med Sci Monit. 2010, 16, CR606-CR615.

- Ashman, R.B., Herring, J.A., Johnston, C.E., et al. TSRH spinal instrumentation. Hundley and Associates, Dallas, USA, 1993.

- Tolo, V.T. Surgical treatment of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Semininars in Spine Surgery Scoliosis, 1991, 3, 220–9.

- Haher, T.R., Merola, A., Zipnick, R.I., et al. Meta-analysis of surgical outcome in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: a 35-year English literature review of 11,000 patients. Spine 1995,14, 1575–84. [CrossRef]

- Theologis, T.N., Jefferson, R.J., Simpson, A.H., et al. Quantifying the cosmetics defect of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Spine 1993,18, 909–12. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noonan, K.J., Dolan, L.A., Jacobson, W.C., Weinstein, S.L. Long-term psychosocial characteristics of patients treated for idiopathic scoliosis. J. Pediatr. Orthop. 1997, 17, 712–17. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koch, K.D., Buchanan, R., Birch, J.G., Morton, A.A., Gatchel, R.J., Browne, R.H. Adolescents undergoing surgery for idiopathic scoliosis: how physical and psychological characteristics relate to patient satisfaction with the cosmetic result. Spine 2001, 26, 2119-24. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farrell, C., Lee, M., Shafran, R. Assessment of body size estimation: a review. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev 2005, 13, 75–88. [CrossRef]

- Gardner, R.M., Brown, D.L. Body size estimation in anorexia nervosa: a brief review of findings from 2003 through 2013. Psychiatry Res 2014, 219, 407–410. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cash, T.F., Deagle, E.A. The nature and extent of body-image disturbances in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa: a meta-analysis. International Journal of Eating Disorders 1997, 22, 107–125. [PubMed]

- Gaudio, S., Brooks, S.J., Riva, G. Nonvisual multisensory impairment of body perception in anorexia nervosa: a systematic review of neuropsychological studies. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e110087. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mölbert, S.C., Thaler, A., Mohler, B.J., Streuber, S., Romero, J., Black, M.J., Zipfel, S., Karnath, H.O., Giel, K.E. Assessing body image in anorexia nervosa using biometric self-avatars in virtual reality: Attitudinal components rather than visual body size estimation are distorted. Psychological Medicine 2017, 26, 1-12.

- Manzoni, G.M., Cesa, G.L., Bacchetta, M., Castelnuovo, G., Conti, S., Gaggioli, A., Mantovani, F., Molinari, E., Cárdenas-López, G., Riva, G. Virtual Reality-Enhanced Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Morbid Obesity: A Randomized Controlled Study with 1 Year Follow-Up. Cyberpsychology, Behaviour and Social Networking. 2016, 19, 134-40. [CrossRef]

- Toppenberg, H.L. HIV‐status acknowledgment and stigma reduction. Maastricht, The Netherlands, 2014.

- Earnshaw, V.A., Chaudoir, S. From Conceptualizing to Measuring HIV Stigma: A Review of HIV Stigma Mechanism Measures. AIDS Behavior 2009;13, 1160–1177. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, J.S., McCabe, C.S. Body Perception Disturbance (BPD) in CRPS. Pract Pain Manag. 2010, 10, 1–6.

- Mehling, W.E., Gopisetty, V., Daubenmier, J., Price, C.J., Hecht, F.M., Stewart, A. Body Awareness: Construct and Self-Report Measures. PLoS ONE. 2009, 4, e5614. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moseley, G.L. I can’t find it! Distorted body image and tactile dysfunction in patients with chronic back pain. PAIN 2008, 140, 239–243. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roosink, M., McFadyen, B.J., Hébert, L.J., Jackson, P.L., Bouyer, L.J., Mercier, C. Assessing the perception of trunk movements in military personnel with chronic non-specific low back pain using a virtual mirror. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0120251. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hodges, P.W., Smeets, R.J. Interaction between pain, movement and physical activity: Short-term benefits, long-term consequences, and targets for treatment. Clin J Pain. 2014, 31, 97–107. [CrossRef]

- Ferrer-García, M., Gutiérrez-Maldonado, J. The use of virtual reality in the study, assessment, and treatment of body image in eating disorders and nonclinical samples: a review of the literature. Body Image 2012, 9, 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Misterska, E., Górski, F., Tomaszewski, M., Bun, P., Gapsa, J., Słysz, A., Głowacki, M. “Scoliosis 3D”—A Virtual-Reality-Based Methodology Aiming to Examine AIS Females’ Body Image. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 2374. [CrossRef]

- Grant, J.R., Cash, T.F. Cognitive-behavioral body-image therapy: Comparative efficacy of group and modest-contact treatments. Behav. Ther. 1995, 26, 69–84. [CrossRef]

- Rosen, J.C., Saltzberg, E., Srebnik, D. Cognitive behavior therapy for negative body image. Behav. Ther. 1989, 20, 393–404. [CrossRef]

- Misterska, E.; Glowacki, M. Longitudinal assessment of changes in psychosocial functioning of patients with adolescent idiopathic scoliosis using virtual reality before, during and after treatment: a quantitative and qualitative study. J. Med. Sci., 2020, 89, e370. [CrossRef]

- Misterska, E., Głowacki, M., Harasymczuk, J. Assessment of spinal appearance in female patients with adolescent idiopathic scoliosis treated operatively based on Spinal Appearance Questionnaire. Med. Sci. Monit. 2011, 17, 404–410. [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.J., Lenke, L.G., Kim, J. et al. Comparative analysis of pedicle screw versus hybrid instrumentation in posterior spinal fusion of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Spine, 2006, 31, 291–98. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, C.I., Cunha, A.B., Braga, V.P., Saad, I.A., Ribeiro, M.A., Conti, P.B. Occurrence of postural deviations in children of a school of Jaguariúna, São Paulo, Brazil, 2009.

- Turner-Stokes L., Erkeller-Yuksel, F., Miles, A., Pincus, T., Shipley, M., Pearce S. Outpatient cognitive behavioral pain management programs: a randomized comparison of a group-based multidisciplinary versus an individual therapy model. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2003, 84, 781–788. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson JK. Body image, eating disorders, and obesity. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, 1996.

- Lipowska, M., Lipowski, M. Polish normalization of the Body Esteem Scale. Health Psychol Rep, 2013, 1, 72‒81. [CrossRef]

- Sanders, J.O., Harrast, J.J., Kuklo, T.R., et al.: The Spinal Appearance Questionnaire: results of reliability, validity, and responsiveness testing in patients with idiopathic scoliosis. Spine 2007, 32, 2719–22. [CrossRef]

- Bago, J., Climent, J.M., Pineda, S., Gilperez, C. Further evaluation of the Walter Reed Visual Assessment Scale: Correlation with curve pattern and radiological deformity. Scoliosis 2007, 2, 12–18. [CrossRef]

- Pineda, S., Bago, J., Gilperez, C., Climent, J.M. Validity of the Walter Reed visual assessment scale to measure subjective perception of spine deformity in patients with idiopathic scoliosis. Scoliosis 2006, 8, 1–18. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Misterska, E., Głowacki, M., Adamczyk, K., Jankowski, R. Patients’ and Parents’ Perceptions of Appearance in Scoliosis Treated with a Brace: A Cross-Sectional Analysis. J Child Fam. Stud. 2014, 23, 1163-1171. [CrossRef]

- Franzoi S., L., Shields, S., A. The Body Esteem Scale: Multidimensional Structure and Sex Differences in a College Population. J Pers. Assess., 1984, 48, 173-8. [CrossRef]

- Goodman, R. The strengths and difficulties questionnaire: a research note. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry Allied Discip. 1997, 38, 581–586. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodman R. Psychometric properties of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ). J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2001, 40, 1337–1345. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazur, J., Tabak, I., Kololo, H.. Toward a better assessment of child and adolescent mental health status. Polish version of strengths and difficulties questionnaire. Dev. Period Med 2007, 11, 13–24.

- de Vignemont, F. Body schema and body image – Pros and cons. Neuropsychologia 2010, 48, 669–680. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Longo, M.R. Implicit and explicit body representations. Eur. Psychol 2015, 20, 6–15. [CrossRef]

- Glowacki, M., Misterska, E., Adamczyk, K., Latuszewska, J. Changes in Scoliosis Patient and Parental Assessment of Mental Health in the Course of Cheneau Brace Treatment Based on the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire. J Dev Phys Disabil. 2013, 25, 325-342. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glowacki, M., Misterska, E., Adamczyk, K., Latuszewska, J. Prospective Assessment of Scoliosis-Related Anxiety and Impression of Trunk Deformity in Female Adolescents Under Brace Treatment. J Dev Phys Disabil. 2013, 25, 203-220. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Niekerk, M., Richey, A., Vorhies, J., Wong, C., Tileston, K. Effectiveness of psychosocial interventions for pediatric patients with scoliosis: a systematic review. World J Pediatr Surg 2023, 6, e000513. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, C.Y.W., Loo, S.F., Ong, J.Y., et al. Feasibility and outcome of an accelerated recovery protocol in Asian adolescent idiopathic scoliosis patients. Spine 2017, 42, E1415–22. [CrossRef]

- Charette, S., Fiola, J.L., Charest, M-C., et al. Guided imagery for adolescent post-spinal fusion pain management: a pilot study. Pain Manag Nurs 2015, 16, 211–20. [CrossRef]

- LaMontagne, L.L., Hepworth, J.T., Cohen, F., et al. Cognitive-behavioral intervention effects on adolescents’ anxiety and pain following spinal fusion surgery. Nurs Res 2003, 52, 183–90. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LaMontagne, L., Hepworth, J.T., Salisbury, M.H., et al.. Effects of coping instruction in reducing young adolescents’ pain after major spinal surgery. Orthop Nurs 2003, 22, 398–403. [CrossRef]

- LaMontagne, L.L., Hepworth, J.T., Cohen, F., et al. Adolescent scoliosis: effects of corrective surgery, cognitive-behavioral interventions, and age on activity outcomes. Appl Nurs Res 2004, 17, 168–77. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 59. Nelson K, Adamek M, Kleiber C. Relaxation training and postoperative music therapy for adolescents undergoing spinal fusion surgery. Pain Manag Nurs 2017;18:16–23.

- Rhodes, L., Nash, C., Moisan, A., et al.. Does preoperative orientation and education alleviate anxiety in posterior spinal fusion patients? A prospective, randomized study. J Pediatr Orthop 2015, 35, 276–9.

- Ying, L., Fu, W. The positive role of rosenthal effect-based nursing in quality of life and negative emotions of patien ts with scoliosis. Int J Clin Exp Med 2020, 13, 3900–6.

- Hinrichsen, G.A., Revenson, T.A., Shinn, M. Does self-help help? J Soc Issues 1985, 41, 65–87.

| CBTSS | CSS | HFS | p value comparison CBTSS/CSS/HFS |

|||||||

| Mean (SD) | Range (Min-Max) |

n (%) | Mean (SD) | Range (Min-Max) |

n (%) | Mean (SD) |

Range (Min-Max) |

n (%) | ||

| Socio-demographic characteristics | ||||||||||

| Place of residence |

p=0.00002* |

|||||||||

| Rural | p=0.060 | - | 3 (16.67) | - | - | 7 (38.89) | - | - | 0 (0) | |

| City below 25, 000 inhabitants | p=0.207 | - | 8 (44.4) | - | - | 2 (11.11) | - | - | 3 (16.67) | |

| City between 25, 000 and 200, 000 inhabitants | - | - | 4 (22.22) | - | - | 7(38.89) | - | - | 1 (5.56) | |

| City over 200, 000 inhabitants | - | - | 3 (16.67) | - | - | 2 (11.11) | - | - | 14 (77.77) | |

| School attended | - | |||||||||

| Elementary | - | - | 9 (50.00) | - | - | 9 (50.00) | - | - | 15 (83.33) | p=0.060 |

| Secondary | - | - | 9 (50.00) | - | - | 9(50.00) | - | - | 3 (16.66) | |

| Age at current [years] | 14.17 (2.01) | 12-17 | - | 14.50 (1.50) | 12-17 | - | 13.56 (1.15) | 12-16 | - | p=0.060 |

| Age at scoliosis diagnosis [years] | 9.9 (3.10) | 5-14 | - | 10.11 (2.56) | 5-14 | - | - | - | - | p=0.816 |

| Weight [kg] | 53.22 (9.61) | 35-70 | - | 52.33 (11.01) | 38-85 | - | 62.00 (15.71) | 40-100 | - | p =0.086 |

| Height [cm] | 160.17 (6.40) | 149-174 | - | 160.89 (5.99) | 153-172 | - | 163.00 (6.75) | 153-176 | - | p=0.392 |

| Body Mass Index | 20.63884(2.88) | 15.77-27.01 | - | 20.16(3.8) | 16.14-31.60 | - | 23.19(5.06) | 17.09-35.42 | - | p=0.076 |

| Family history of scoliosis | - | - | 5 (27.78) | - | - | 6 (33.33) | - | - | 2(11.11) | p= 0.370 |

| Comorbidities | - | - | 3(16.67) | - | - | 3 (16.67) | - | - | 4(22.22) | p<1 |

| Clinical and radiological characteristics | CBTSS | CSS |

p value comparison CBTSS/CSS (preoperatively/ postoperatively) |

|||||||

| Preoperatively | Postoperatively | Preoperatively | Postoperatively | |||||||

| Mean (SD) |

Range (Min-Max) |

Mean (SD) |

Range (Min-Max) |

Mean (SD) |

Range (Min-Max) |

Mean (SD) |

Range (Min-Max) |

|||

| Duration of CBT [hours] | 5.22 (2.0) | 2-9 | 5.80 (2.24) | 1-9 | - | |||||

| Duration of brace treatment prior to surgery [in months] | 24.11(20.20) | 0-72 | - | 35.06(25.43) | 0-84 | - | p=0.162 | |||

| Cobb angle in the main curve | 61.33 (8.0) | 52-78 | 23.22 (7.69) | 16-50 | 62.16 (10.70) | 46-86 | 24.27 (8.76) | 12-46 | p=0.793/p=0.466 | |

| Kyphosis angle in the thoracic spine | 26.33(19.11) | 6-40 | 18.94(7.99) | 7-37 | 21.22(11.31) | 4-38 | 18.28 (7.58) | 4-32 | p=0.419/p=0.799 | |

| Lordosis angle in the lumbar spine | 48.61(9.98) | 24-70 | 39.28(10.44) | 12-64 | 38.33 (11.72) | 15-60 | 30.59 (10.95) | 6-55 | p=0.008*/p=0.020* | |

| Apical translation of the central sacral vertical line (CSVL) according to the Harms Study Group) [cm] | 4.43(1.96) | 0.3-8.7 | 1.51(1.31) | 0-5.8 | 4.97 (1.87) | 1.3-8.6 | 1.68 (0.82) | 0.5-3.2 | p=0.410/p=0.254 | |

| % of scoliosis correction | - | 60.50 (11.67) | 34-76 | - | 61.50 (11.46) | 38-81 | p=0.949 | |||

| Mean (SD) | 95% Confidence interval (from-to) |

Range (Min-Max) |

Mean (SD) | 95% Confidence interval (from-to) |

Range (Min-Max) |

Mean (SD) | 95% Confidence interval (from-to) |

Range (Min-Max) |

||

| Preoperatively | Postoperatively | Follow-up | ||||||||

| CBTSS | ||||||||||

| SAQ | ||||||||||

| General | 4.15(0.38) | 3.96-4.34 | 3.33-4.66 | 3.69(1.544) | 2.92-4.45 | 2.0-8.33 | 3.33(1.04) | 2.71-3.96 | 1.67-5.00 | |

| Curve | 3.39(0.85) | 2.97-3.81 | 2.0-5.0 | 1.50(1.04) | 0.98-2.09 | 1.0-5.0 | 1.08(0.28) | 0.91-1.24 | 1.00-2.00 | |

| Prominence | 2.25(0.67) | 1.92-2.58 | 1.0-3.5 | 1.11(0.37) | 0.93-1.30 | 1.0-2.5 | 1.08(0.19) | 0.96-1.19 | 1.00-1.50 | |

| Trunk shift | 2.75(0.80) | 2.35-2.58 | 1.0-4.5 | 1.44(0.66) | 1.12-1.77 | 1.0-3.0 | 1.15(0.32) | 0.96-1.34 | 1.00-2.00 | |

| Waist | 4.26(0.95) | 3.79-4.73 | 1.67-5.0 | 2.75(1.57) | 1.98-3.54 | 1.0-5.0 | 2.10(1.40) | 1.25-2.95 | 1.00-5.00 | |

| Shoulders | 3.63(0.54) | 3.37-3.91 | 2.50-4.5 | 2.08(0.97) | 1.60-2.57 | 1.0-4.0 | 2.00(0.94) | 1.43-2.57 | 1.00-3.50 | |

| Kyphosis | 2.44(0.78) | 2.05-2.83 | 1.0-4.0 | 1.39(0.61) | 1.09-1.70 | 1.0-3.0 | 1.38(0.65) | 0.99-1.78 | 1.00-3.00 | |

| Chest | 3.81(1.38) | 3.12-4.49 | 1.0-5.0 | 2.61(1.58) | 1.83-3.40 | 1.0-5.0 | 1.88(1.44) | 1.0-2.76 | 1.00-5.00 | |

| Surgical scar | - | - | - | 1.94(1.21) | 1.34-2.55 | 1.00-5.00 | 1.30(0.63) | 0.93-1.69 | 1.00-3.00 | |

| Total score | 3.50(0.46) | 3.27-3.73 | 2.25-4.0 | 2.30(0.98) | 1.81-2.78 | 1.25-4.06 | 1.94 (0.72) | 1.50-2.37 | 1.25-3.31 | |

| CSS | ||||||||||

| SAQ | ||||||||||

| General | 3.87(0.61) | 3.57-4.17 | 2.33-4.67 | 3.19(0.99) | 2.70-3.68 | 2.00-5.00 | 3.43(1.03) | 2.70-4.17 | 2.00-5.00 | |

| Curve | 3.22(0.88) | 2.79-3.66 | 1.00-5.00 | 1.61(1.29) | 0.98-2.25 | 1.00-5.00 | 1.70(0.67) | 1.21-2.18 | 1.00-3.00 | |

| Prominence | 2.08(0.84) | 1.66-2.50 | 1,00-4.50 | 1.39(0.68) | 1.06-1.73 | 1.00-3.50 | 1.30(0.35) | 1.05-1.55 | 1.00-2.00 | |

| Trunk shift | 2.50(0.91) | 2.05-2.95 | 1.00-4.50 | 1.64 (1.03) | 1.13-2.14 | 1.00-4.50 | 1.45(0.64) | 0.99-1.91 | 1.00-3.00 | |

| Waist | 3.59(1.21) | 2.99-4.20 | 1.00-5.00 | 2.85(1.58) | 2.07-3.64 | 1.00-5.00 | 2.90(1.41) | 1.89-3.91 | 1.00-5.00 | |

| Shoulders | 3.14(1.07) | 2.61-3.67 | 1.0-5.00 | 2.11(1.21) | 1.51-2.71 | 1.00-5.00 | 2.35(1.08) | 1.58-3.12 | 1.00-3.50 | |

| Kyphosis | 2.17(0.99) | 1.68-2.66 | 1.00-5.00 | 1.56(1.29) | 0.91-2.20 | 1.00-5.00 | 1.30(0.83) | 0.95-1.64 | 1.00-2.00 | |

| Chest | 3.22(1.61) | 2.42-4.02 | 1.00-5.00 | 2.58(1.60) | 1.77-3.38 | 1.00-5.00 | 2.60(1.26) | 1.70-3.50 | 1.00-5.00 | |

| Surgical scar | - | - | - | 1.72(0.75) | 1.35-2.10 | 1.00-3.00 | 1.30(0.67) | 0.82-1.78 | 1.00-3.00 | |

| Total score | 3.10(0.80) | 2.71-3.50 | 1.25-4.63 | 2.30 (1.00) | 1.80-2.80 | 1.25-4.56 | 2.34(0.79) | 1.77-2.91 | 1.25-3.44 | |

| HFS (one assessment) | ||||||||||

| SAQ | ||||||||||

| General | 3.07(0.80) | 2.68-3.47 | 2.00-4.33 | |||||||

| Curve | 1.11(0.32) | 0.95-1.71 | 1.00-2.00 | |||||||

| Prominence | 1.083(0.19) | 0.99-1.18 | 1.00-1.50 | |||||||

| Trunk shift | 1.22(0.31) | 1.07-1.38 | 1.00-2.00 | |||||||

| Waist | 2.93(1.08) | 2.39-3.46 | 1.00-5.00 | |||||||

| Shoulders | 2.11(0.95) | 1.64-2.58 | 1.00-3.50 | |||||||

| Kyphosis | 1,39(0.61) | 1.09-1.69 | 1.00-3.00 | |||||||

| Chest | 2.47(1.31) | 1.82-3.12 | 1.00-5.00 | |||||||

| Surgical scar | - | - | - | |||||||

| Total score | 2.14(0.54) | 1.87-2.41 | 1.38-3.06 | |||||||

| CBTSS | CSS | HFS | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preoperatively | Postoperatively | Follow-up | Preoperatively | Postoperatively | Follow-up | ||

|

Which form of deformity bothers you the most out of these 5 categories of images? (Item no. 8) |

n (%) | ||||||

| None | 0 (0) | 7 (38.33) | 7 (38.33) | 2 (11.11) | 7 (38.33) | 3 (16.67) | 18 (100) |

| Rib prominence | 3 (16.67) | 2 (11.11) | 1 (5.55) | 4 (22.22) | 2 (11.11) | 0 (0) |

- |

| Flank prominence | 5 (27.77) | 3 (16.67) | 0 (0) | 2 (11.11) | 3 (16.67) | 2 (11.11) | |

| Head Chest Hips | 4 (22.22) | 1 (5.55) | 3 (16.67) | 7 (38.33) | 1 (5.55) | 2 (11.11) | |

| Shoulder level | 3 (16.67) | 4 (22.22) | 1 (5.55) | 1 (5.55) | 4 (22.22) | 2 (11.11) | |

| Spine prominence | 3 (16.67) | 1 (5.55) | 1 (5.55) | 2 (11.11) | 1 (5.55) | 1 (5.55) | |

| Of questions 9-17which are the most important to you? (Item no. 18) | n (%) | ||||||

| None | 1 (5.55) | 5 (27.77) | 8 (44.44) | 5 (27.77) | 12 (76.66) | 5 (27.77) | 14 (77.78) |

| A question on the desire to have a correct trunk shape | 6 (38.33) | 4 (22.22) | 2 (11.11) | 5 (27.77) | 2 (11.11) | 2 (11.11) | 0 (0) |

| A question on better appearance in clothing | 2 (11.11) | 3 (16.67) | 1 (5.55) | 1 (5.55) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (5.55) |

| A question on symmetrical hips | 1 (5.55) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (5.55) | 0 (0) |

| A question on even waist | 4 (22.22) | 2 (11.11) | 0 (0) | 6 (38.33) | 3 (16.67) | 0 (0) | 3 (16.67) |

| A question on even length of legs | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| A question on symmetrical breasts | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| a question on even chest in the front | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| A question on symmetrical shoulders | 3 (16.67) | 1 (5.55) | 0 (0) | 1 (5.55) | 0 (0) | 2 (11.11) | 0 (0) |

| A question on surgical scar | - | 2 (11.11) | 2 (11.11) | - | 1 (5.55) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Mean (SD) | 95% Confidence interval (from-to) |

Range (Min-Max) |

Mean (SD) | 95% Confidence interval (from-to) |

Range (Min-Max) |

Mean (SD) | 95% Confidence interval (from-to) |

Range (Min-Max) |

|

| Preoperatively | Postoperatively | Follow-up | |||||||

| CBTSS | |||||||||

| BES for females | |||||||||

| Sexual Attractiveness | 47.00(7.32) | 43.36-50.64 | 37.00-63.00 | 48.17(8.23) | 44.08-52.26 | 38.00-62.00 | 49.46(6.70) | 45.42-53.50 | 38.00-59.00 |

| Weight Concern | 33.27(9.56) | 28.53-38.03 | 20.00-50.00 | 36.33(8.27) | 32.21-40.45 | 20.00-50.00 | 37.54(9.01) | 32.10-42.99 | 20.00-50.00 |

| Physical Condition | 32.44(6.72) | 29.10-35.79 | 23.00-45.00 | 33.39(6.63) | 30.09-36.69 | 25.00-45.00 | 31.46(7.30) | 27.05-35.87 | 18.00-45.00 |

| Reference to sten norms (n/%) | Low | Medium | High | Low | Medium | High | Low | Medium | High |

| Sexual Attractiveness | 9(49.43) | 4(22.22) | 5(27.77) | 7(38.33) | 4(22.22) | 7(38.33) | 4(2.22) | 3(16.67) | 6(33.32) |

| Weight Concern | 6(33.32) | 5(27.77) | 7(38.33) | 1(5.55) | 7(38.33) | 10(55.54) | 1(5.55) | 5(27.77) | 7(38.33) |

| Physical Condition | 18(100) | 0(0) | 0(0) | 18(100) | 0(0) | 0(0) | 6(33.32) | 4(22.22) | 3(16.67) |

| CSS | |||||||||

| BES for females | |||||||||

| Sexual Attractiveness | 45.11(8.66) | 40.81-49.22 | 20.00-59.00 | 46.94(6.79) | 43.56-50.32 | 34.00-60.00 | 44.20(3.91) | 41.40-47.00 | 41.00-54.00 |

| Weight Concern | 33.33(10.52) | 28.10-38.56 | 15.00-50.00 | 37.50(7.52) | 33.76-41.24 | 24.00-50.00 | 33.60(8.47) | 27.54-39.66 | 18.00-50.00 |

| Physical Condition | 32.28(7.65) | 28.48-36.08 | 15.00-45.00 | 32.61(7.24) | 29.01-36.21 | 20.00-45.00 | 27.40(6.47) | 22.77-32.03 | 18.00-38.00 |

| Reference to sten norms (n/%) | Low | Medium | High | Low | Medium | High | Low | Medium | High |

| Sexual Attractiveness | 9(49.43) | 6(33.33) | 3(16.67) | 8(43.88) | 5(27.77) | 5(27.77) | 8(43.88) | 1(5.55) | 1(5.55) |

| Weight Concern | 6(33.33) | 4(22.22) | 8(43.88) | 1(5.55) | 8(43.88) | 9(49.43) | 1(5.55) | 5(27.77) | 4(22.22) |

| Physical Condition | 18(100) | 0(0) | 0(0) | 18(100) | 0(0) | (0) | 7(38.00) | 2(11.11) | 1(5.55) |

| HFS (one assessment) | |||||||||

| BES for females | |||||||||

| Sexual Attractiveness | 44.11(5.30) | 41.48-46.74 | 31.00-53.00 | ||||||

| Weight Concern | 28.06(7.97) | 24.09-32.02 | 15.00-44.00 | ||||||

| Physical Condition | 30.83(8.18) | 26.77-34.90 | 16.00-44.00 | ||||||

| Reference to sten norms (n/%) | Low | Medium | High | ||||||

| Sexual Attractiveness | 9(49.43) | 8(43.88) | 1(5.55) | ||||||

| Weight Concern | 9(49.43) | 7(38.00) | 2(11.11) | ||||||

| Physical Condition | 18(100) | 0(0) | 0(0) | ||||||

| VR tasks | Median | Range (min-max) |

Lower quartile-upper quartile | Median | Range (min-max) | Lower quartile/ upper quartile |

Median | Range (min-max) |

Lower quartile/ upper quartile |

| CBTSS Preoperatively/ postoperatively |

CSS Preoperatively/ postoperatively |

HFS | |||||||

| 1st indicator | 4.00/2.00 | 3.00-7.00/ 1.00-3.00 |

3.00-6.00/ 2.00-3.00 |

4.00/2.00 | 2.00-7.00/ 1.00-4.00 |

3.00-5.00/ 2.00/2.00 |

1.00 | 1.00-4.00 | 1.00-2.00 |

| 2nd indicator | 2.00/1.00 | 1.00-3.00/ 1.00-3.00 |

1.00-3.00/ 2.00-3.00 |

2.00/2.00 | 1.00-3.00/ 1.00-3.00 |

1.00-2.00/ 1.00/2.00 |

1.00 | 1.00-3.00 | 1.00-1.00 |

| 3rd indicator | 6.00/2.00 | 5.00-7.00/ 1.00-5.00 |

5.00-6.00/ 1.00-2.00 |

6.00/2.00 | 4.00-7.00/ 1.00-4.00 |

5.00-7.00/ 1.00-2.00 |

1,00 | 1.00-1.00 | 1.00-1.00 |

| 4th indicator | p=0.287/p=0.908 | p=0.907/p=1 | p=0.090 | ||||||

| 5th indicator | p<0.000001*/p=1 | p<0.000001*/p=1 | p=1 | ||||||

| 6th indicator | p=0.0007*/p=0.029* | p=0.002*/p=0.287 | p=0.200 | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | 95% Confidence interval (from-to) |

Range (Min-Max) |

Mean (SD) | 95% Confidence interval (from-to ) |

Range (Min-Max) |

Mean (SD) | 95% Confidence interval (from-to) |

Range (Min-Max) |

|

| Preoperatively | Postoperatively | Follow-up | |||||||

| CBTSS | |||||||||

| SDQ-25 | |||||||||

| Emotional symptoms | 4.11(2.78) | 2.73-5.50 | 0,00-9.00 | 3.11(2.42) | 1.91-4.32 | 0.00-7.00 | 3.69(2.46) | 2.20-5.18 | 0.00-7.00 |

| Conduct problems | 3.50(1.72) | 2.64-4.36 | 1,00-7.00 | 3.11(1.32) | 2.45-3.77 | 1.00-7.00 | 3.38(2.79) | 1.70-5.07 | 1.00-11.00 |

| Hyperactivity/Inattention | 4.94(1.55) | 4.17-5.72 | 3,00-8.00 | 5.67(1.33) | 5.01-6.33 | 3.00-8.00 | 5.00(1.52) | 4.08-5.92 | 3.00-8.00 |

| Peer Relation Problems | 5.00(0.97) | 4.52-5.48 | 4,00-7.00 | 5.00(1.33) | 4.34-5.66 | 2.00-7.00 | 5.85(2.15) | 4.54-7.15 | 4.00-12.00 |

| Pro-social Behavior | 7.50(1.76) | 6.63-8.37 | 3,00-10.00 | 7.67(1.85) | 6.75-8.59 | 4.00-10.00 | 7.46(1.76) | 6.39-8.52 | 4.00-9.00 |

| Total score | 17.56(5.00) | 15.07-20.04 | 10,00-27.00 | 16.89(4.53) | 14.63-19.14 | 10.00-27.00 | 17.92(6.91) | 13.75-22.10 | 11.00-35.00 |

| CSS | |||||||||

| SDQ-25 | |||||||||

| Emotional symptoms | 3.56(2.50) | 2.31-4.80 | 0.00-8.00 | 3.50(2.28) | 2.37-4.63 | 0.00-8.00 | 3.20(2.20) | 1.63-4.77 | 0.00-8.00 |

| Conduct problems | 2.61(0.98) | 2.12-3.10 | 1.00-5.00 | 2.72(1.18) | 2.14-3.31 | 1.00-5.00 | 2.50(1.27) | 1.59-3.41 | 1.00-5.00 |

| Hyperactivity/Inattention | 4.56(1.58) | 3.77-5.34 | 1.00-7.00 | 5.28(1.56) | 4.50-6.06 | 2.00-7.00 | 5.50(1.71) | 4.27-6.72 | 3.00-8.00 |

| Peer Relation Problems | 4.89(1.23) | 4.28-5.50 | 3.00-8.00 | 4,72(1.27) | 4.09-5.36 | 2.00-6.00 | 4.70(0.82) | 4.11-5.29 | 3.00-6.00 |

| Pro-social Behavior | 7.22(2.41) | 6.02-8.42 | 2.00-10.00 | 8.00(1.81) | 7.10-8.90 | 4.00-10.00 | 6.60(1.90) | 5.24-7.96 | 3.00-9.00 |

| Total score | 15.61(4.41) | 13.42-17.80 | 10.00-26.00 | 16.22(4.91) | 13.78-18.66 | 7.00-26.00 | 15.90(4.58) | 12.62-19.18 | 10. 00-26.00 |

| HFS (one assessment) | |||||||||

| SDQ-25 |

- |

||||||||

| Emotional symptoms | 5.17(2.60) | 3.88-6.46 | 0.00-10.00 | ||||||

| Conduct problems | 4.00(1.24) | 3.39-4.61 | 2.00-7.00 | ||||||

| Hyperactivity/Inattention | 5.06(1.73) | 4.19-5.92 | 2.00-8.00 | ||||||

| Peer Relation Problems | 4.78(1.35) | 4.11-5.45 | 2.00-6.00 | ||||||

| Pro-social Behavior | 7.28(2.24) | 6.16-8.39 | 3.00-10.00 | ||||||

| Total score | 19.00(5.38) | 16.32-21.68 | 9.00-29.00 | ||||||

| SAQ-total score | Comparison Presurgical/postsurgical/follow-up | |||||

| CBTSS | CSS | |||||

| p=0.0001* |

p=0.304 |

|||||

| Comparison Presurgical/ postsurgical: p=0.007* |

Comparison Postsurgical/ follow-up: p=0.980 |

Comparison Presurgical/ follow-up: p=0.018* |

||||

| BES-Sexual attractiveness | p=0.383 | p=0.710 | ||||

| BES-Weight concern | p=0.009* | p=0.268 | ||||

| Comparison Presurgical/postsurgical: p=0.040* | Comparison Postsurgical/follow-up: p=0.082 |

Comparison Presurgical/follow-up: p=0.010* |

||||

| BES-Physical condition | p=0.096 | p=0.385 | ||||

| SDQ-25-total score | p=0.447 | p=0.010* | ||||

| Comparison Presurgical/postsurgical: p=0.057 | Comparison Postsurgical/follow-up: p=0.057 |

Comparison Presurgical/follow-up: p=1 |

||||

| VR tasks | Comparison Presurgical/postsurgical | |||||

| 1st indicator | p=0=0002* | p=0.0002* | ||||

| 2nd indicator | p=0.142 | p=0.361 | ||||

| 3rd indicator | p=0.0002* | p=0.0002* | ||||

| Preoperatively | Postoperatively | Follow-up | |

| Comparison CBTSS/CSS/HFS | Comparison CBTSS/CSS/HFS | Comparison CBTSS/CSS/HFS | |

| VR tasks | - | ||

| 1st indicator | p<0.00001*, CA:p=1, CB:p=0.0009*,CC:p=0.00008* | p=0.314 | |

| 2nd indicator | p<0.000001*, CA:p=1, CB:p=0.000004*,CC:p=0.000007* | p=0.312 | |

| 3rd indicator | p<0.000001*, CA:p=1, CB:p=0.000002*,CC:p=0.0000001* | p=0.850 | |

| SAQ | |||

| General | p=0.0007*, CA:p=0.377, CB:p=0.0001*,CC:p=0.001* | p=0.432 | p=0.366 |

| Curve | p<0.00001*, CA: p=1; CB:p=0.000001*; CC: p=0.000005* | p=0.984 | p=0.004*, CA: p=0.091, CB: p=1, CC: p=0.091 |

| Prominence | p<0.00001*, CA: p=1; CB:p=0.000006*; CC: p=0.0003* | p=0.667 | p=0.081 |

| Trunk shift | p<0.00001*, CA: p=1; CB:p=0.000001*; CC: p=0.0001* | p=0.691 | p=0.371 |

| Waist | p=0.003*, A: p=0.301; B:p=0.000001*; C: p=0.000005* |

p=0.910 | p=0.137 |

| Shoulders | p=0.001*,CA: p=0.500; CB:p=0.0001*; CC: p=0.018* | p=0.734 | p=0.649 |

| Kyphosis | p=0.0005*, CA: p=0.784; CB:p=0.001*; CC: p=0.042* | p=0.466 | p=0.967 |

| Chest | p=0.003*, CA: p=0.301; CB:p=0.000001*; CC: p=0.000005* |

p=0.987 | p=0.176 |

| Surgical scar | - | - | - |

| Total score | p=0.026*, CA:p=0.751, CB:p=0.024*, CC:p=0.402 | p=0.937 | p=0.575 |

| BES for females | |||

| Sexual Attractiveness | p=0.712 | p=0.630 | p=0.522 |

| Weight Concern | p=0.165 | p=0.661 | p=0.0143, CA: p=0.514; CB: p=0.010*; CC: p=0.231 |

| Physical Condition | p=0.780 | p=0.849 | p=0.400 |

| SDQ-25 | |||

| Emotional symptoms | p=0.185 | p=0.623 | p=0.098 |

| Conduct problems | p=0.006*, CA: p=0.220; CB:p=0.551; CC: p=0.005* | p=0.419 | p=0.014*, CA: p=;1 CB: p=0.103; CC: p=0.028* |

| Hyperactivity/Inattention | p=0.627 | p=0.427 | p=0.700 |

| Peer Relation Problems | p=0.867 | p=0.554 | p=0.308 |

| Pro-social Behavior | p=0.993 | p=0.582 | p=0.388 |

| Total score | p=0.368 | p=0.650 | p=0.236 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).