Abstract. The surface velocity of the Amery Ice Shelf (AIS) is vital to assessing its stability and mass balance. Previous studies have shown that the AIS basin has a stable multi-year average surface velocity. However, spatiotemporal variations in the surface velocity of the AIS and the underlying physical mechanism remain poorly understood. This study combined offset tracking and DInSAR methods to extract the monthly average surface velocity of the AIS and obtained the inter-annual surface velocity from the ITS_LIVE product. An uneven spatial distribution in inter-annual variation of the surface velocity was observed between 2000–2022, although the magnitude of variation was small at less than 20.5 m/yr. The increase and decrease in surface velocity on the eastern and western-central sides of the AIS, respectively, could be attributed to the change in the thickness of the AIS. There was clear seasonal variation in monthly average surface velocity at the eastern side of the AIS between 2017–2021, which could be attributed to variations in the area and thickness of fast-ice and also to variations in ocean temperature. This study suggested that changes in fast-ice and ocean temperature are the main factors driving spatiotemporal variation in the surface velocity of the AIS.

1. Introduction

The Amery Ice Shelf (AIS) is the largest ice shelf in the East Antarctic Ice Sheet and buttresses the Lambert Glacier Basin. The Lambert Glacier Basin is the fourth largest basin in Antarctica, draining ~12.5% of the Antarctic Ice Sheet. Since the AIS drains only 2.5% of the East Antarctic coastline, it is a sensitive indicator of mass discharge of the East Antarctic Ice Sheet (Gardner, Moholdt et al. 2018, Shen, Wang et al. 2018). A report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC, 2023) suggested that the warming climate is resulting in enhanced surface and basal melting of ice shelves, which in turn drives increasing ice surface velocity (Völz and Hinkel 2023). Therefore, surface velocity is the most direct indicator of movement of glaciers and ice sheets in Antarctica under the effects of global climate change (Aoki, Takahashi et al. 2022).

Remote sensing has acted to improve large-scale and high-resolution measurements of surface velocities, thereby providing the comprehensive observations required for modern scientific investigations of polar region ice movement (Jacobs, Giulivi et al. 2013, Shen, Wang et al. 2020, Lei, Gardner et al. 2021). Current measurements of ice movements mainly rely on synthetic aperture radar (SAR) and optical remote sensing technology (Dirscherl, Dietz et al. 2020). However, optimal remote monitoring provides surface velocity with limited accuracy due to the impacts of sunshine and snow clouds (Joughin, Smith et al. 2017). Monitoring of surface velocity in recent decades has been improved using SAR, which enables accurate large-scale detection of surface motion. In particular, SAR images from the Sentinel-1 satellite are freely available from 2014 and 2016, respectively (Nagler, Rott et al. 2015, Wang and Holland 2020). This satellite has provided monthly measurements of surface velocity. Many surface velocity datasets for the AIS have been released (Mouginot, Scheuchl et al. 2012, Jawak, Kumar et al. 2019, Lei, Gardner et al. 2021, Rignot, Mouginot et al. 2022). These datasets have been based on feature tracking or a cross-correlation between optical images and differential interferometric SAR (DInSAR) or Offset tracking.

DInSAR has allowed the measurement of surface velocity at an unprecedented spatial resolution and precision of millimeter to centimeter levels (Joughin, Smith et al. 2017). However, the accuracy and resolution of DInSAR data are dependent on the local environment and time between acquisitions. Consequently, ionospheric perturbations, tidal fluctuations, and fast-ice motion act to limit the accuracy of DInSAR methods (Schubert, Faes et al. 2013). Offset tracking is particularly applicable to acquisition of data with long repeat intervals and this technology allows the derivation of ice motion in areas of persistent fast-ice flow (Fanghui, Chunxia et al. 2015, Dirscherl, Dietz et al. 2020). However, the accuracy of offset tracking is several orders of magnitude lower than that of DInSAR at a resolution of several meters. Consequently, measurements by offset tracking are not of sufficient accuracy for the analysis of variation in surface velocity of the AIS (slow-ice flow). While there have been many previous studies (Manson, Coleman et al. 2000, Fanghui, Chunxia et al. 2015, Tong, Liu et al. 2018, Zhou, Liang et al. 2019, Chi and Klein 2020) on changes in the surface velocity of the AIS, the spatiotemporal variation in the surface velocity of the AIS remains poorly understood. In addition, there remains little understanding of the physical mechanisms during variation in the surface velocity of the AIS and possible oceanic forcing.

The current study aimed to accurately extract the surface velocity field of AIS basin. The objectives of the current study were to: (1) Offset tracking was used to extract the surface velocity of the ice shelf region with fast ice flow; (2) DInSAR was applied to extract the surface velocity of the ice sheet with slow ice flow, and the split-spectrum method was implemented to eliminate the ionospheric phase of InSAR pairs with serious ionospheric distraction; (3) DInSAR-based range surface velocity and Offset-tracking azimuth surface velocity were combined to provide an monthly average surface velocity of the AIS; (4) We collected inter-annual average surface velocity products were released by the Inter-mission Time Series of Land Ice Velocity and Elevation (ITS_LIVE) product (Lei, Gardner et al. 2022); (5) We investigated variations in the thickness of the AIS and identify the roles of possible ocean forcing factors, including ocean temperature and fast ice. The results of the present study can act as a reference for future studies on the movement of glaciers and ice sheets in Antarctica under the effects of global climate change.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Characterization of Inter-Annual Variation in Surface Velocity Using ITS_LIVE Products

The present study investigated the inter-annual variation in the surface velocity of the AIS by analyzing ITS_LIVE surface velocity products. These products provide a global coverage of inter-annual variation in surface velocity at a spatial resolution of 240 m from 1985 to 2022. As described in Lei, Gardner et al. (Lei, Gardner et al. 2021, Lei, Gardner et al. 2022), the core processing algorithm of the ITS_LIVE project utilizes a combination of a precise geocoding module “Geogrid” and an efficient offset tracking module “autoRIFT” (autonomous Repeat Image Feature Tracking). The present study selected the surface velocity of the AIS basin from 2000 to 2022 from ITS_LIVE surface velocity products.

2.2. Characterization of Intra-Annual Variation in Surface Velocity Using DInSAR and Offset Tracking

The present study combined the range of surface velocity derived from DInSAR with azimuth surface velocity derived from offset tracking to improve the accuracy of the surface velocity field, thereby fully utilizing the advantages of these two technologies. This approach has been widely applied for extraction of surface velocity of polar ice sheet or glaciers (Tong, Liu et al. 2018, Mouginot, Rignot et al. 2019).

2.2.1. Offset Tracking and Sentinel-1 Data

The surface velocity used in the present study were derived from Sentinel-1 single-look complex synthetic aperture radar (SAR) images acquired in the interferometric wide swath mode. This mode acquires data with large swath widths (250 km) with a 3.7 m ground range and 15.6 m azimuth resolution (Nagler, Rott et al. 2015). The large spatial coverage and high spatial resolution of Sentinel-1 images allows for the measurement of monthly surface velocity of the AIS. The present study conducted offset tracking of interferometric synthetic aperture radar in the Scientific Computing Environment (ISCE) remote-sensing software using Sentinel-1 images to retrieve the surface velocity from 2017 to 2021. First, rough co-registration was performed between selected pairs of images. This step started with co-registration using an external digital elevation model (DEM; Reference Elevation Mode of Antarctica, RAMP) with a resolution of 100 m. Furthermore, a matching technique and spectral diversity method were used to refine the co-registration. The final co-registration was used to calculate the two-dimensional offsets with a search window size and step size of 640 × 128 pixels and 40 × 10 pixels, respectively. The accuracy of the surface velocity was evaluated using abundant rock points near the AIS basin. The results had a surface velocity error within 3.82 m/yr, consistent with those of previous related studies (Shen, Wang et al. 2018, Tong, Liu et al. 2018, Chi and Klein 2020). The accuracy in evaluated surface velocity was sufficient for the analysis of variations in surface velocity in the AIS region with fast flow. Unfortunately, there were no available surface velocity for the west side of the AIS for some months each year, possibly due to surface melting or wind-blown snow.

2.2.2. DInSAR and Sentinel-1 Data

The error in surface velocity derived from offset tracking for the AIS ice sheet region with slow-ice flow, particularly in the region in which surface velocity is < 100 m/yr, may exceed the variation in surface velocity, resulting in misinterpretation during the analysis of variation in surface velocity. Therefore, the present study combined DInSAR with Sentinel-1A images to extract monthly average surface velocity of the AIS ice sheet regions from 2017 to 2021. The step of DInSAR with co-registration were consistent with those of offset tracking. The interferometric phase consists of the topography, flat-earth phase, ice movement and ionospheric phase. The interferogram has to be flattened and the topographic phase has to be removed using a high-accuracy DEM. At the same time, the adaptive filter and multi-look processing were used to reduce the noise. To obtain to ice movement in the range direction, the interferometric phase has to be unwrapped with the minimum-cost network flow (MCF) method (Joughin, Smith et al. 2017). However, frequent ionospheric disturbances in the polar region resulted in considerable contamination of the interferometric phase (Liao, Meyer et al. 2018, Li, Wang et al. 2020). Even for Sentinel-1 SAR (C-band) images (Liang, Agram et al. 2019), the ionospheric disturbance cannot be ignored under natural phenomena such as auroras or strong magnetic storms (Kamel Hasni 2017) . We employed a split-spectrum method (Liang, Agram et al. 2019, Ma, Wang et al. 2022) to correct the interferometric phase with severe ionospheric disturbance in boxes 1–4 of

Figure 3. The present study reduced the calculation load and time required for the correction of the data for ionospheric influences and minimized over-correction by identifying Sentinel-1 SAR data that were seriously affected by ionospheric disturbance using the geomagnetic index Kp, auroral current aggregation index AU&AL, and geomagnetic symmetric disturbance component SYM-H (Kumar and Parkinson 2017, Li, Wang et al. 2020). The results of the three indicators shown in

Figure 1 indicated that the SAR major and slave image interferometric pair acquisition times from 31

st January to 6

th February, 2017 coincided with major magnetic storms, whereas those from 19

th January to 25

th January, 2017 coincided with a period of relatively little ionospheric disturbance. As shown in

Figure 2B,F, the relative ionospheric phase of the interferometric pairs was estimated using the split-spectrum method. The present study analyzed the interferogram without ionospheric correction (

Figure 2A,E) and the interferogram with ionospheric correction (

Figure 2C,G) along the central profile line. As shown in

Figure 2D,H, the surface velocity from the central profile line indicated severe ionospheric disturbance from the 31

st January to 6

th February, 2017. However, there was minimal ionospheric disturbance from 19

th January to 25

th January, 2017.

2.2.3. Combination of the DInSAR Range in Surface Velocity and Offset Tracking Azimuth Surface Velocity

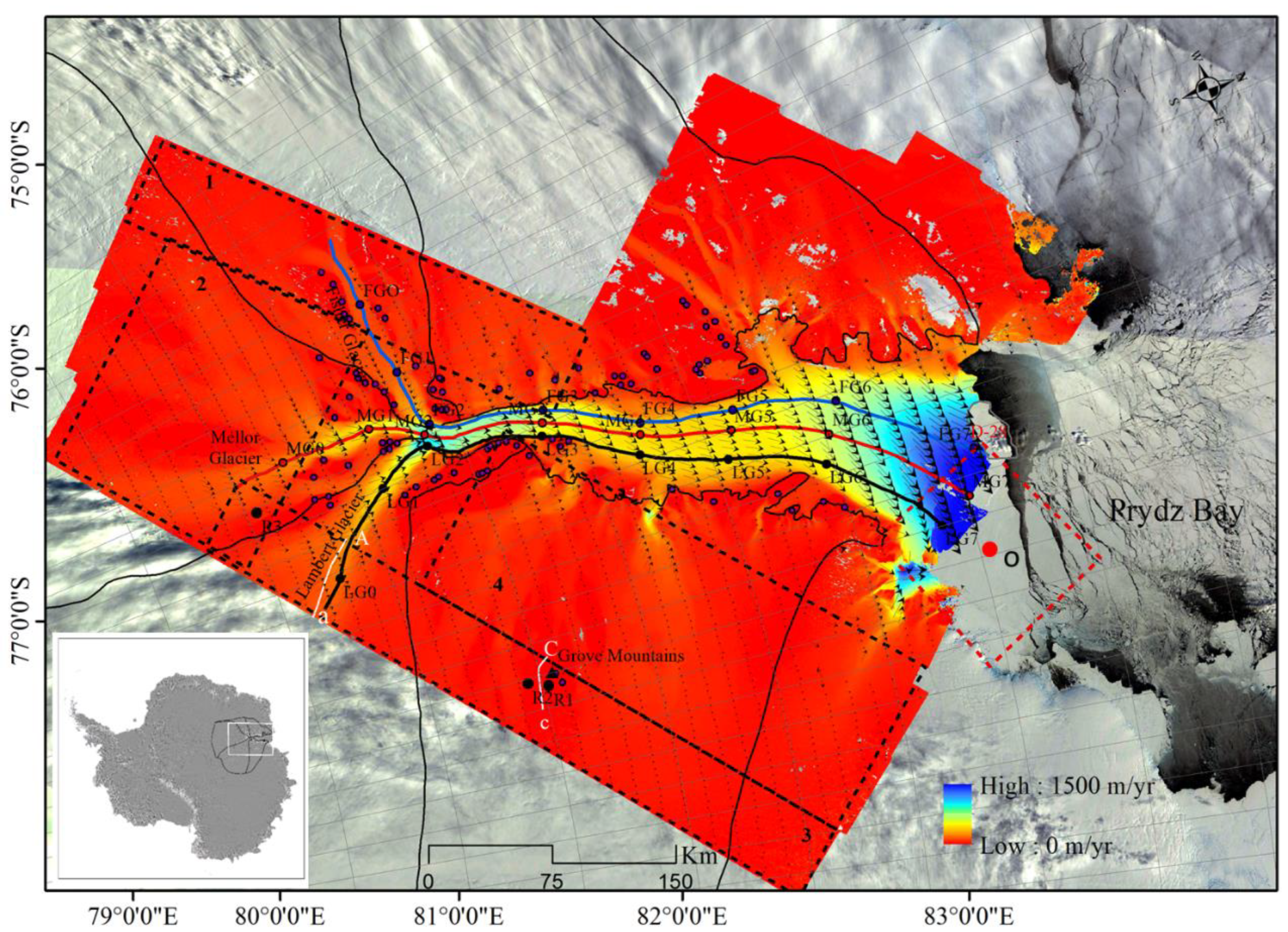

Offset tracking provides both the range and azimuth direction of surface velocity. However, DInSAR provides surface velocity in the range direction at a high spatial resolution and precision. The present study combined the DInSAR range of surface velocity and the azimuth surface velocity calculated by offset tracking by assuming parallel surface flow (Dirscherl, Dietz et al. 2020). Some systematic bias between two adjacent tracks was noted, which was removed according to the surface velocity of rock points near the AIS (Tong, Liu et al. 2018). The surface velocity between two adjacent tracks was mosaicked by averaging the surface velocities in the overlapping area. As shown in

Figure 3, this process allowed a seamless and continuous surface velocity with high accuracy to be derived.

Figure 3.

The seamless and continuous surface velocity of the Amery Ice Shelf (AIS) basin. The solid black line represents the boundary of the basin; the black arrow indicates the direction of flow; the bold blue FG, red MG, and black LG lines represent the ice streamlines with eight monitoring points for three different regions of the basin, respectively; the black dashed boxes 1, 2, 3, and 4 represent regions in which the data were corrected for ionospheric disturbances; the white solid line represents the profile line in box 3, which was used to assess the accuracy of the surface velocity corrected for disturbances by ionospheric influences in the box 3 region (as shown in

Figure 6); the black points R1–R3 represent rock points in box 3 and were used to compare the surface velocity derived from offset tracking with that from DInSAR which was corrected for ionospheric factors; FG0, MG0, and LG0 of the AIS ice sheet are in boxes 1, 2, and 3, respectively; the purple points represent rock points near the AIS and were applied to assess the accuracy of ITS_LIVE surface velocity; the red dotted polygon was used to estimate the area of fast ice attached to the AIS; D-28 represents the iceberg code; the red dot O indicates the central location in which the equivalent thickness of fast ice according to the Estimating the Circulation and Climate of the Ocean, Phase II (ECCO2) ocean model (Fukumori, Fenty et al. 2019, Consortium, Fukumori et al. 2021) was extracted; the solid white line in the Antarctic ice sheet map at the bottom left represents the AIS study area.

Figure 3.

The seamless and continuous surface velocity of the Amery Ice Shelf (AIS) basin. The solid black line represents the boundary of the basin; the black arrow indicates the direction of flow; the bold blue FG, red MG, and black LG lines represent the ice streamlines with eight monitoring points for three different regions of the basin, respectively; the black dashed boxes 1, 2, 3, and 4 represent regions in which the data were corrected for ionospheric disturbances; the white solid line represents the profile line in box 3, which was used to assess the accuracy of the surface velocity corrected for disturbances by ionospheric influences in the box 3 region (as shown in

Figure 6); the black points R1–R3 represent rock points in box 3 and were used to compare the surface velocity derived from offset tracking with that from DInSAR which was corrected for ionospheric factors; FG0, MG0, and LG0 of the AIS ice sheet are in boxes 1, 2, and 3, respectively; the purple points represent rock points near the AIS and were applied to assess the accuracy of ITS_LIVE surface velocity; the red dotted polygon was used to estimate the area of fast ice attached to the AIS; D-28 represents the iceberg code; the red dot O indicates the central location in which the equivalent thickness of fast ice according to the Estimating the Circulation and Climate of the Ocean, Phase II (ECCO2) ocean model (Fukumori, Fenty et al. 2019, Consortium, Fukumori et al. 2021) was extracted; the solid white line in the Antarctic ice sheet map at the bottom left represents the AIS study area.

2.3. Ocean Temperatures

The present study investigated the effect of potential oceanic forcing on spatiotemporal variation in surface velocity of the AIS by extracting daily ocean temperatures between 2000 and 2022 from the ECCO2. The average vertical ocean temperatures between the depths of 250 m and 600 m were evaluated, corresponding with the depths of the modified Circumpolar Deep Water (mCDW) linked to changes in AIS basal melt and thickness (Liang, Zhou et al. 2019). Consequently, the average ocean temperatures of ECCO2 products were extracted from three different regions of the AIS front (indicated as red pentagrams in

Figure 8) between 2000 and 2022.

2.4. Fast-Ice Area and Thickness

Fast-ice appears and disappears periodically in Prydz Bay every year (Zhao, Cheng et al. 2020). The present study extracted the fast-ice edge by manual examination of cloud-free, true-color, moderate-resolution imaging spectroradiometer (MODIS) images with 250-m resolution during summer. Winter fast-ice edge was also manually extracted from co-registered Sentinel-1 images (Li, Shokr et al. 2020, Gomez-Fell, Rack et al. 2022). The present study obtained the total area of fast ice (km

2) from monthly fast-ice area for 2017 to 2022 derived from MODIS and Sentinel-1 images. A rectangular box (25 km × 25 km) representing the influence of fast ice on the AIS front was defined (indicated by the red dotted polygon in

Figure 3) and the area of fast ice in the box was calculated. However, the area of fast ice represents a weak index of fast-ice strength, and cannot fully explain the degree of solidification of the ice body (Hoppmann, Nicolaus et al. 2015, Mallett, Stroeve et al. 2021, Xu, Li et al. 2021). The thickness of fast ice in the Antarctic winter reflects the degree of solidification of the ice body and its resistance on the AIS. As shown in

Figure 3, the present study obtained the monthly equivalent thickness of fast ice from the ECCO2 model from 2017 to 2021 based on a rectangular box centered at point O (69.625 °S,38.625 °E). The variations in the area and thickness of fast ice area were then compared to the surface velocity of the AIS (

Figure 14).

2.5. Thickness of the Amery Ice Shelf

The present study constructed a 30-year time series of monthly average surface elevation at a 5-kilometer grid resolution for the Antarctic ice shelves for 1991 to 2020. Stepwise adjustment was then applied to these data, and the results in combination with observations from four satellite altimetry missions were used to compare changes in the thickness of the AIS with variations in surface velocity (Zhang, Liu et al. 2020). Then, based on the hydrostatic equilibrium assumption (Zhang, Wang et al. 2020), the present study inverted a 30-year time series of monthly average thickness at a 5-kilometer grid resolution for Antarctic ice shelves. As shown in

Figure 4, the thickness of the AIS ranged from 256 m to 3,806 m. These data were validated using airborne laser altimetry data from the IceBridge program and ice-penetrating radar observations from the Bedmap3 active group (Xu, Li et al. 2021). A comparison of the surface elevation time series with airborne laser altimetry data provided a root mean square error (RMSE) of 5.79 m and an R-squared (R

2) of 0.97. Overall, the dataset constructed using satellite altimetry was shown to be reliable.

3. Results

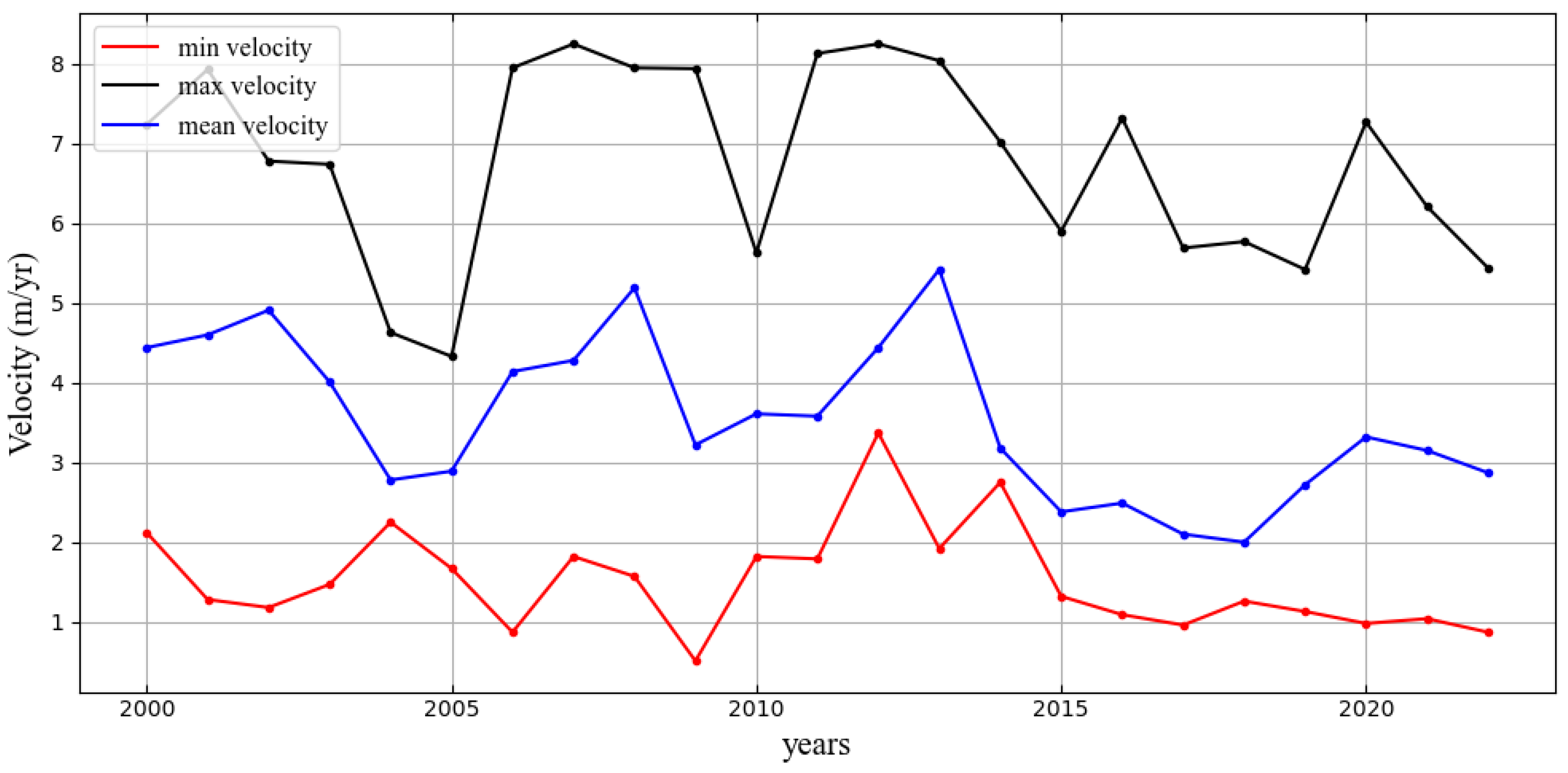

3.1. Assessment of the Accuracy of Annual Mean Surface Velocity

The present study manually selected all rock points from the georeferenced intensity image (represented by purple dots in

Figure 3). The accuracy of the surface velocity provided by ITS_LIVE was evaluated by averaging the surface velocities of all rock points to produce the annual average surface velocity, as shown in

Figure 5. The error in the calculated annual average surface velocity ranged from 0.97 m/yr to 8.16 m/yr, with an average of 3.65 m/yr. These results indicated that the error was sufficiently small to allow for the analysis of inter-annual variation in surface velocity in the AIS region from 2000 to 2022.

3.2. Assessment of the Accuracy of Monthly Average Surface Velocity

The present study combined offset tracking and DInSAR with ionospheric correction to extract monthly high-precision surface velocity in the AIS basin from 2017 to 2021. The dotted boxes 1–4 in

Figure 3 represent regions of DInSAR surface velocity with ionospheric correction calculated using the split-spectrum method. The area of box 3 was used an example to investigate the performance of the surface velocity corrected for ionospheric influences. The area in box 3 encompasses the end of the Lambert Glacier and the Grove Mountains regions (Liao, Meyer et al. 2018, Ma, Wang et al. 2022). DInSAR-based surface velocity was compared to surface velocity from MEaSUREs (Mouginot, Rignot et al. 2019). A profile along the profiles Aa and Cc (white solid line in

Figure 3) was extracted and DInSAR-based surface velocity was plotted without and with ionospheric correction, as shown in

Figure 6. DInSAR-based surface velocities without ionospheric correction at profiles Aa and Cc deviated significantly from surface velocities from MEaSUREs (

Figure 6A,B). These deviations reach 6 m/yr in the Lambert glacier region and 4.1 m/yr in the Grove Mountains region. DInSAR-based surface velocities with ionospheric correction at Aa and Cc were consistent with surface velocities from MEaSUREs (

Figure 6C,D), suggesting the need for ionospheric correction of DInSAR-based surface velocities for the AIS ice sheet region.

The present study further evaluated the errors in surface velocities obtained by three methods: (1) Only offset Tracking; (2) Combining offset Tracking and DInSAR without ionospheric correction; (3) Combining offset Tracking and DInSAR with ionospheric correction. The surface velocities of rock points R1–R3 in box 3 (

Figure 3) were then evaluated the errors using the above three methods, as shown in

Table 1. The results showed that the maximum error of method (1) surface velocities at the three rock points was 3.82 m/yr, whereas that of method (2) surface velocities was 1.77 m/yr, similar to that of MEaSUREs-based surface velocity. The maximum error of method (3) was 0.28 m/yr, which was sufficiently small to allow for the analysis of variations in monthly average surface velocity of the AIS ice sheet.

Figure 6.

Box 3 time series surface velocity profile analysis without and with ionospheric correction. (A) and (B) represented Reference surface velocity from MEaSUREs (Gray dotted line), and DInSAR-derived surface velocity without ionospheric correction (others color lines) from profile Aa and Cc, respectively. (C) and (D) represented Reference surface velocity from MEaSUREs (Gray dotted line), and DInSAR-derived surface velocity with ionospheric correction (others color lines) from profile Aa and Cc, respectively.

Figure 6.

Box 3 time series surface velocity profile analysis without and with ionospheric correction. (A) and (B) represented Reference surface velocity from MEaSUREs (Gray dotted line), and DInSAR-derived surface velocity without ionospheric correction (others color lines) from profile Aa and Cc, respectively. (C) and (D) represented Reference surface velocity from MEaSUREs (Gray dotted line), and DInSAR-derived surface velocity with ionospheric correction (others color lines) from profile Aa and Cc, respectively.

As shown in

Figure 7, the present study also compared the variations in DInSAR-based surface velocity with and without ionospheric correction at three monitoring points (FG0, MG0, and LG0) in the AIS ice sheet region (

Figure 1) from 2017 to 2021. The results indicated that surface velocity with ionospheric correction at LG0 showed significant seasonal variation from 2017 to 2021. However, there were no significant seasonal changes in surface velocity with ionosphere correction at FG0 and MG0.

3.3. Inter-Annual Variation in Surface Velocity from 2000 to 2022

As shown in

Figure 8, the present study extracted ITS_LIVE inter-annual surface velocity at eight monitoring points on three ice streamlines (FG, MG, and LG) from 2000 to 2022. As shown in

Figure 9, the variations in the inter-annual surface velocity at all monitoring points indicated acceleration in the surface velocity of the LG ice streamline (eastern AIS). There was deceleration in the surface velocity of the MG ice streamline (central ice streamline), besides that in MG7, which accelerated. Similarly, there was deceleration in the surface velocity of the FG ice streamline (western AIS), besides for that at FG7, which was stable.

A comparison of the variations in surface velocity at LG7, MG7, and FG7 in the AIS front showed acceleration in the surface velocity of the AIS front, with the highest acceleration at LG7 (eastern AIS), in which surface velocity increased by 14.7% (average annual acceleration of 20.5 m/yr), followed by MG7 (central AIS front), in which surface velocity increased by 9.2% (average annual acceleration of 9.5 m/yr). Surface velocity at FG7 (western AIS) was relatively stable.

A comparison of changes in surface velocity at LG2, MG2, and FG2 near the southernmost groundling line of the AIS showed acceleration in the surface velocity of LG2 (eastern side of the grounding line), increasing by 2.57% (average annual acceleration of 0.6 m/yr). The remaining monitoring points (LG3–LG6) on the LG ice flow line showed similar accelerations in surface velocity to that of LG2. However, the surface velocity of MG2 (central region of the southernmost grounding line) and FG2 (western side of the southernmost grounding line) decreased by 4.3% (average annual deceleration of 0.77 m/yr) and 3.9% (average annual deceleration of 0.58 m/yr), respectively. Other monitoring points of the MG ice streamlines (MG3–MG6) and FG ice streamline (FG3–FG6) showed similar decelerations in surface velocity to that of MG2 and FG2.

Both LG0 and LG1 of the LG ice streamline are in the AIS ice sheet region and both showed relatively small changes in surface velocity. LG1, 60 km from the southernmost grounding line, showed a slight increase in surface velocity of 0.15% (average annual acceleration of 0.24 m/yr), whereas LG0, 120 km from the southernmost grounding line, showed a stable surface velocity. MG0 and MG1 of the MG ice streamline and FG0 and FG1 of the FG ice streamline are also located in the AIS ice sheet region. The surface velocities of MG1 and FG1, both 60 km from the southernmost grounding line, decreased slightly by 0.11% (average annual deceleration of 0.20 m/yr) and 0.3% (average annual deceleration of 0.18 m/yr), respectively. MG0 and FG0, both 120 km from the southernmost grounding line, showed stable surface velocities.

Figure 8.

Ice streamlines of the Amery Ice Shelf (AIS). The gray dotted lines represent ice streamlines; the blue, red, and black lines represent the FG, MG, and LG ice streamlines in three main regions on the western, middle, and eastern sides of the AIS, respectively, with eight monitoring points located at each ice streamline; the gray line represents the grounding line; the blue arrow indicates the direction of the mCDW in the ice cavity; the yellow lines represent the boundaries of the polynyas in August, 2018; the red arrows represent the clockwise cyclonic gyre (Prydz gyre). The present study estimated the average ocean temperatures at a depth of between 250 m and 600 m from positions represented by the red pentagrams (P1–P3).

Figure 8.

Ice streamlines of the Amery Ice Shelf (AIS). The gray dotted lines represent ice streamlines; the blue, red, and black lines represent the FG, MG, and LG ice streamlines in three main regions on the western, middle, and eastern sides of the AIS, respectively, with eight monitoring points located at each ice streamline; the gray line represents the grounding line; the blue arrow indicates the direction of the mCDW in the ice cavity; the yellow lines represent the boundaries of the polynyas in August, 2018; the red arrows represent the clockwise cyclonic gyre (Prydz gyre). The present study estimated the average ocean temperatures at a depth of between 250 m and 600 m from positions represented by the red pentagrams (P1–P3).

Figure 9.

Inter-annual surface velocity changes at eight monitoring points of the FG, MG and LG ice streamline from 2000 to 2022.

Figure 9.

Inter-annual surface velocity changes at eight monitoring points of the FG, MG and LG ice streamline from 2000 to 2022.

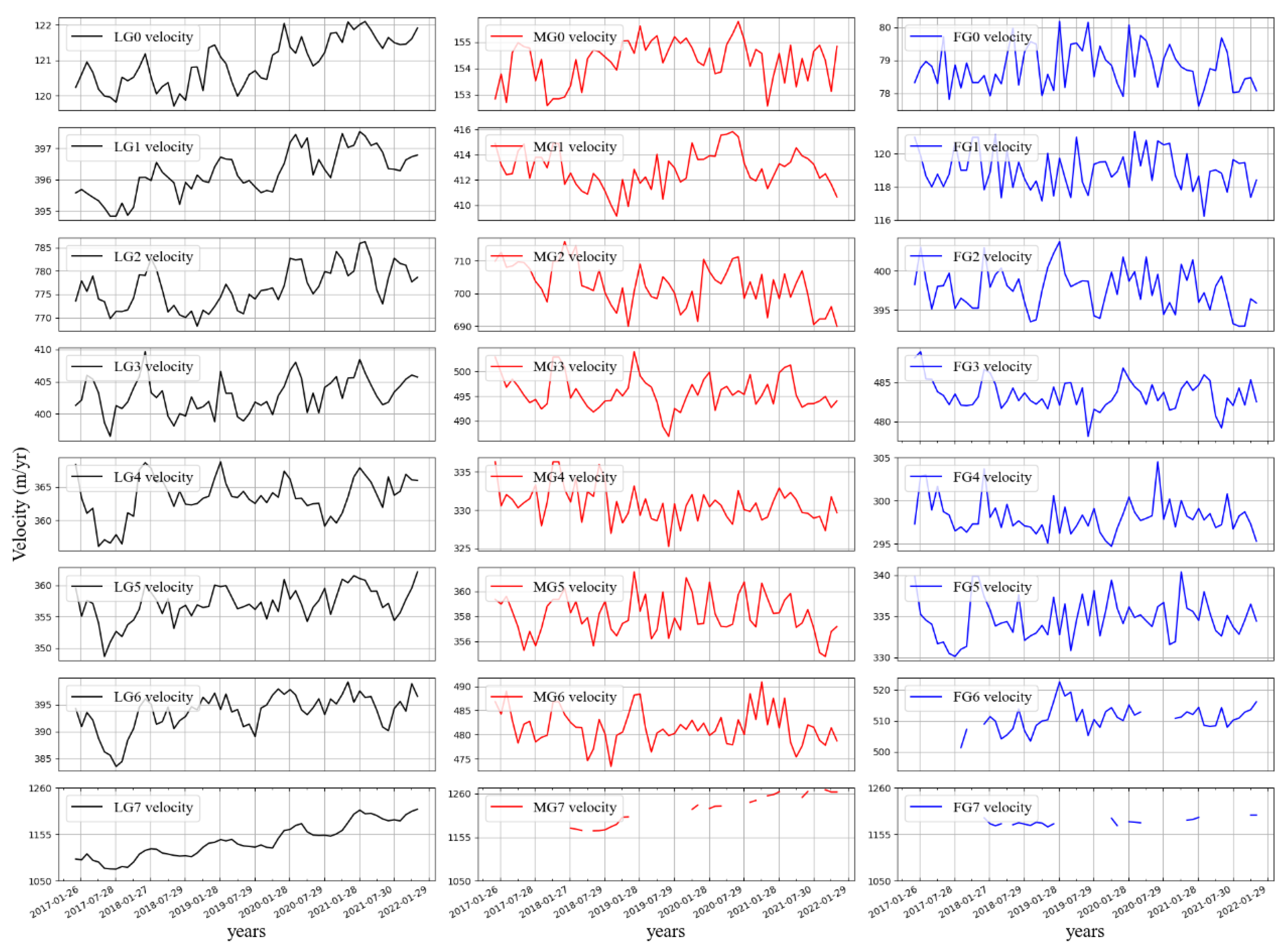

3.4. Seasonal Variation in Surface Velocity from 2017 to 2021

As shown in

Figure 8, the present study extracted the intra-annual variation in surface velocity at all monitoring points of the FG, MG, and LG ice streamlines from 2017 to 2021. As shown in

Figure 10, the variations in monthly average surface velocity in the three regions of the AIS were analyzed. The results indicated no seasonal variation in the surface velocities of the FG and MG ice streamlines, although their surface velocities decelerated. However, the surface velocities of all monitoring points of the LG ice streamline showed significant seasonal variations, and the highest and lowest surface velocities were in summer and winter, respectively. Among all the monitoring points of the LG ice streamline, the surface velocity at LG7, in the AIS front, decelerated from March to September at an average rate of 21.7 m/yr, whereas it accelerated from October to February of the following year, at an average rate of 44.3 m/yr. The acceleration in summer surface velocity exceeded the deceleration in winter surface velocity by a factor of two, resulting in an overall acceleration in annual surface velocity at LG7. Seasonal variations in surface velocities at other monitoring points on the LG ice streamline (eastern side of AIS) were similar to that at LG7, although the magnitudes of variations were smaller.

Table 2 shows a summary of a comparison of surface velocities of all monitoring points on the LG ice streamline. The results showed that the AIS front (LG7) had the highest magnitudes of variations in surface velocity, followed by those at the southernmost grounding line (LG2), followed by those at the ice shelf (LG3–LG6), with those at the ice sheet (LG0–LG1) the smallest. This result can possibly be attributed to the sensitivity of the AIS front to changes in the marine environment due to its direct contact with the ocean. In contrast, since the ice sheet is far away from the ocean, variation in its surface velocity is less sensitive to changes in the marine environment.

The absence of monthly average surface velocities for FG7 and MG7 for some months prevented an accurate assessment of the variations in surface velocity. However, the present study determined that surface velocity at MG7 was accelerating, whereas that at FG7 was relatively stable. A comparison of surface velocities at FG7, MG7, and LG7 showed that their rank according to the acceleration in surface velocity was LG7 > MG7 > FG7.

4. Discussion

Previous studies have shown spatially uneven and temporally periodic variations in the surface velocities of ice shelves and glaciers (Nitsche, Gohl et al. 2013). Variations in surface velocities can be attributed to a variety of physical mechanisms, mainly including: (1) a change in the viscosity of the ice body leading to variations in ice flow (Herraiz-Borreguero, Church et al. 2016); (2) changes in the buttressing force of the ice shelf resulting from the disappearance or growth of impediments (such as fast ice and ice shelf calving) in the ice shelf front (Han, Im et al. 2016, Lee, Kim et al. 2023); (3) basal melting and refreezing of the ice shelf, resulting in thinning and thickening of the ice shelf (Scambos, Bohlander et al. 2004, Jacobs, Giulivi et al. 2013, Aoki, Takahashi et al. 2022). The present study surveyed variations in the surface velocity of the AIS in response to possible ocean forcing and analyzed the physical mechanisms responsible.

4.1. Effect of Ocean Temperature and AIS Thickness on Variations in Inter-Annual Surface Velocity

By considering the thickness of the AIS Front and the mCDW depth, the present study calculated the average ocean temperature at depths of 250 m to 600 m in three regions (P1–P3, indicated by red, five-pointed stars in

Figure 8) near the coastline of the AIS front (Zhou, Zhou et al. 2017).

Figure 11 shows the ECCO2-derived daily ocean temperatures of the AIS front from 2000 to 2022. The results showed inconsistent changes in the magnitudes and peaks in ocean temperature in P1–P3 (

Figure 8). The ocean temperature of P2 of between 2000–2007 slightly exceeded those of both P1 and P3 by , whereas that of P3 between 2008–2022 exceeded those of P2 and P1 by and , respectively.

Several oceanic models (Galton-Fenzi, Hunter et al. 2012, Herraiz-Borreguero, Coleman et al. 2015, Liu, Wang et al. 2018) has confirmed a clockwise circulation in the AIS ice cavity from east to west (the blue arrow on the AIS in

Figure 8) via the Prydz Gyre. This circulation can be attributed to the inflow of the warm mCDW into the eastern side of the AIS and the outflow of the cold mCDW from the western side of the AIS. Previous studies have observed the path of mCDW intrusions in May 2012 using MEOP-CDT data (Liu, Wang et al. 2017, Wang, Zhou et al. 2023). The strong eastward jet along the eastern branch of the cyclonic Prydz Bay gyre at a depth of between 250 m and 400 m represents the main pathway for mCDW (red arrows in

Figure 8) flow toward the eastern side of the AIS front (Liu, Wang et al. 2018). A portion of the mCDW flows southward along the eastern side of the AIS and circulates clockwise from east to west near the southernmost grounding line of the AIS. The warm mCDW mixes with the meltwater in the cavity, thereby reducing the temperature of the mCDW in the western AIS. Another part of the mCDW circulates clockwise from east to west in the central region of the AIS. This circulation mixes with meltwater, thereby also resulting in a decrease in the temperature of the mCDW (Herraiz-Borreguero, Coleman et al. 2015, Wang, Zhou et al. 2023). Following mixing of the two parts of the mCDW, meltwater flows out from the western side of the AIS front, eventually moving toward the McKenzie polynya. During the circulation of mCDW in the AIS ice cavity (Herraiz-Borreguero, Coleman et al. 2015, Herraiz-Borreguero, Church et al. 2016), the warm mCDW contributes to the basal melting of the eastern AIS (melting rate of 1.8 ± 0.3 m/yr), thereby decreasing the thickness of the AIS. At the same time, the cold mCDW contributes to basal refreezing of the central and western regions of the AIS (refreezing rate of 1.8±0.3 m/yr), resulting in a thicker AIS.

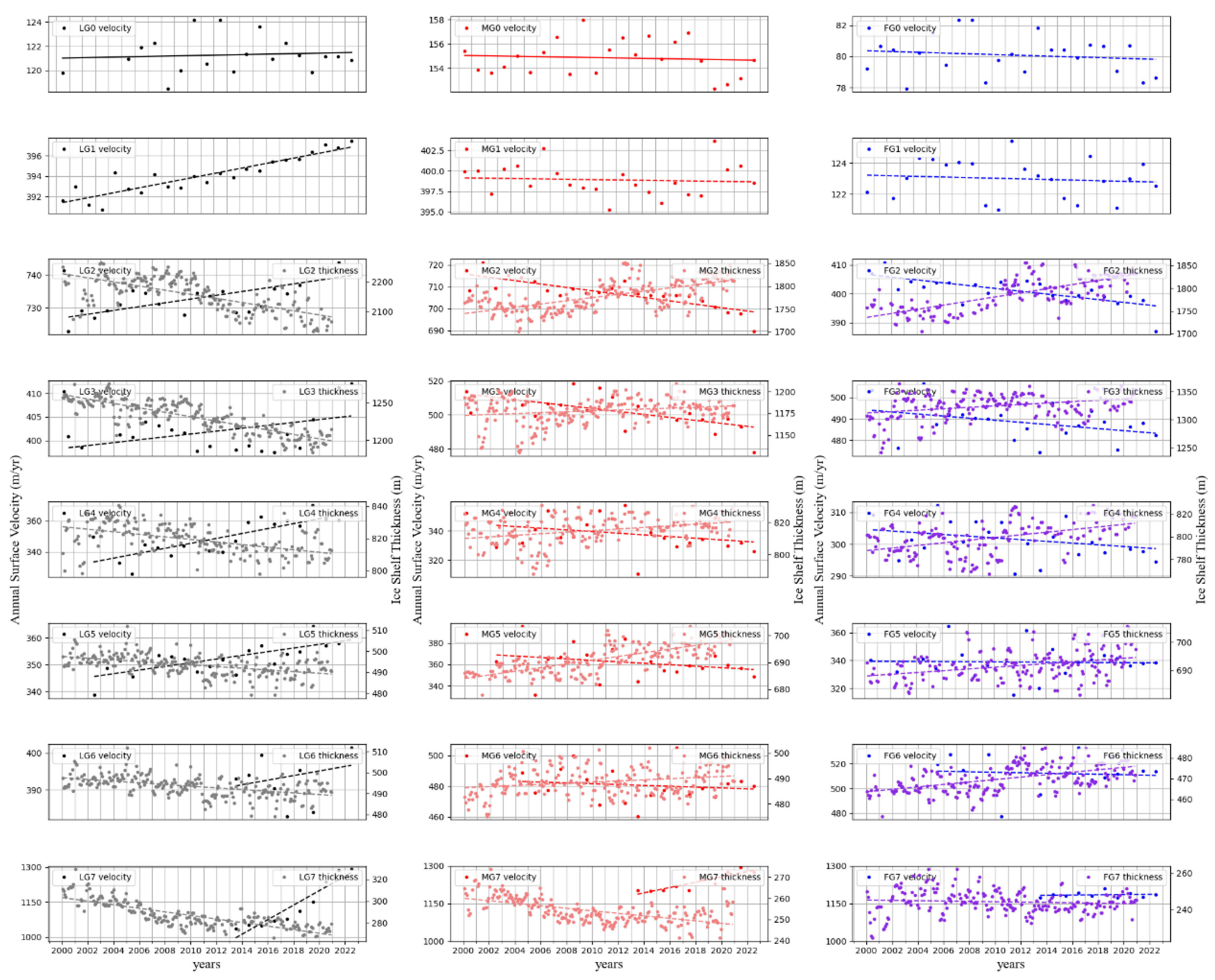

As shown in

Figure 12, the present study compared the variations in the surface velocities of all monitoring points of the FG, MG, and LG ice streamlines with variations in the thickness of the AIS. Unfortunately, only the variations in the thickness of the ice shelf were obtained, whereas no data were obtained for the ice sheet (

Figure 4). The results indicated an acceleration in the surface velocity of the LG ice streamline between 2000–2022, resulting in a decrease in ice thickness. Besides for the acceleration in surface velocity and decrease in ice thickness of MG7, surface velocities at MG2–MG6 decreased, whereas there were increases in ice thickness. Besides for FG7 in which surface velocity and ice thickness remained stable, the surface velocities at FG2–FG6 decreased, whereas their ice thicknesses increased. The ocean temperature of P1 exceeded those of P2, which in turn exceeded that of P3. The corresponding acceleration in surface velocity of LG7 exceeded that of MG7, whereas the surface velocity at FG7 was relatively stable. These results suggested that the ocean temperature at the AIS front was the main factor driving variations in surface velocity at FG7, MG7, and LG7 in the AIS front.

4.2. Effect of Fast-Ice on Variations in Intra-Annual Surface Velocity

The present study estimated the area of fast-ice attached to the AIS front and calculated its equivalent thickness using the ECCO2 model (Fukumori, Fenty et al. 2019) between 2017–2022.

Figure 13 shows the changes in the area of fast-ice in the AIS front between summer and winter. The results showed seasonal growth and retreat in fast-ice in the eastern side of the AIS front. In contrast, there was no fast-ice in the western and middle regions of the AIS front in which the Mackenzie polynya persists (

Figure 8 and

Figure 13). These results suggest that fast-ice has no effect on the surface velocities of the western and middle regions (FG and MG ice streamlines), thereby possibly explaining the lack of seasonal variation in the surface velocities of the western and central regions. Therefore, the present study only extracted the area and thickness of fast ice for the eastern region of the AIS front (88.875°S, 75.875°E) representing the central grid unit (point O in the red dotted box in the

Figure 3). The influences of variations in the area and thickness of fast ice on surface velocity of the LG ice streamline were then assessed. LG7 on the LG ice streamline is closest to the fast-ice region and most sensitive to changes in fast-ice. As shown in

Figure 14, the present study analyzed the relationship between variations in the area and thickness of fast-ice at LG7 and surface velocity. The results showed increases in the area and thickness of fast-ice from February to July, resulting an increase in the buttressing force of fast-ice and a decrease in the surface velocity of LG7 at a rate of 20.1 m/yr. There was a slight decrease in the area of fast-ice from July to September, whereas its thickness continued to increase, resulting in an increase in its buttressing force. This resulted in a slight decrease in surface velocity at a rate of 1.5 m/yr. These results suggested that the thickness of fast-ice had a slightly bigger effect on its buttressing force than its area. The area and thickness of fast-ice rapidly decreased from October to February of the following year. This resulted in a sharp decrease in its buttressing force and an acceleration in surface velocity at LG7 at a rate of 44.3 m/yr. The acceleration in surface velocity at LG7 exceeded deceleration by a factor of two, resulting in an overall acceleration in the annual average surface velocity in the eastern region of the AIS. In addition, the magnitudes of variations in surface velocities at the other monitoring points of the LG ice streamline were relatively small. This result can be attributed to LG being relatively far the fast-ice region, and therefore less sensitive to variations in fast-ice. Although there were seasonal variations in surface velocity, the magnitudes of variation were small.

Figure 13.

The fast-ice in the AIS front were extracted from the MODIS Images in summer (January) and winter (August).

Figure 13.

The fast-ice in the AIS front were extracted from the MODIS Images in summer (January) and winter (August).

Figure 14.

The AIS front fast-ice area and equivalent thickness is compared with the LG7 surface velocity from 2017 to 2021.

Figure 14.

The AIS front fast-ice area and equivalent thickness is compared with the LG7 surface velocity from 2017 to 2021.

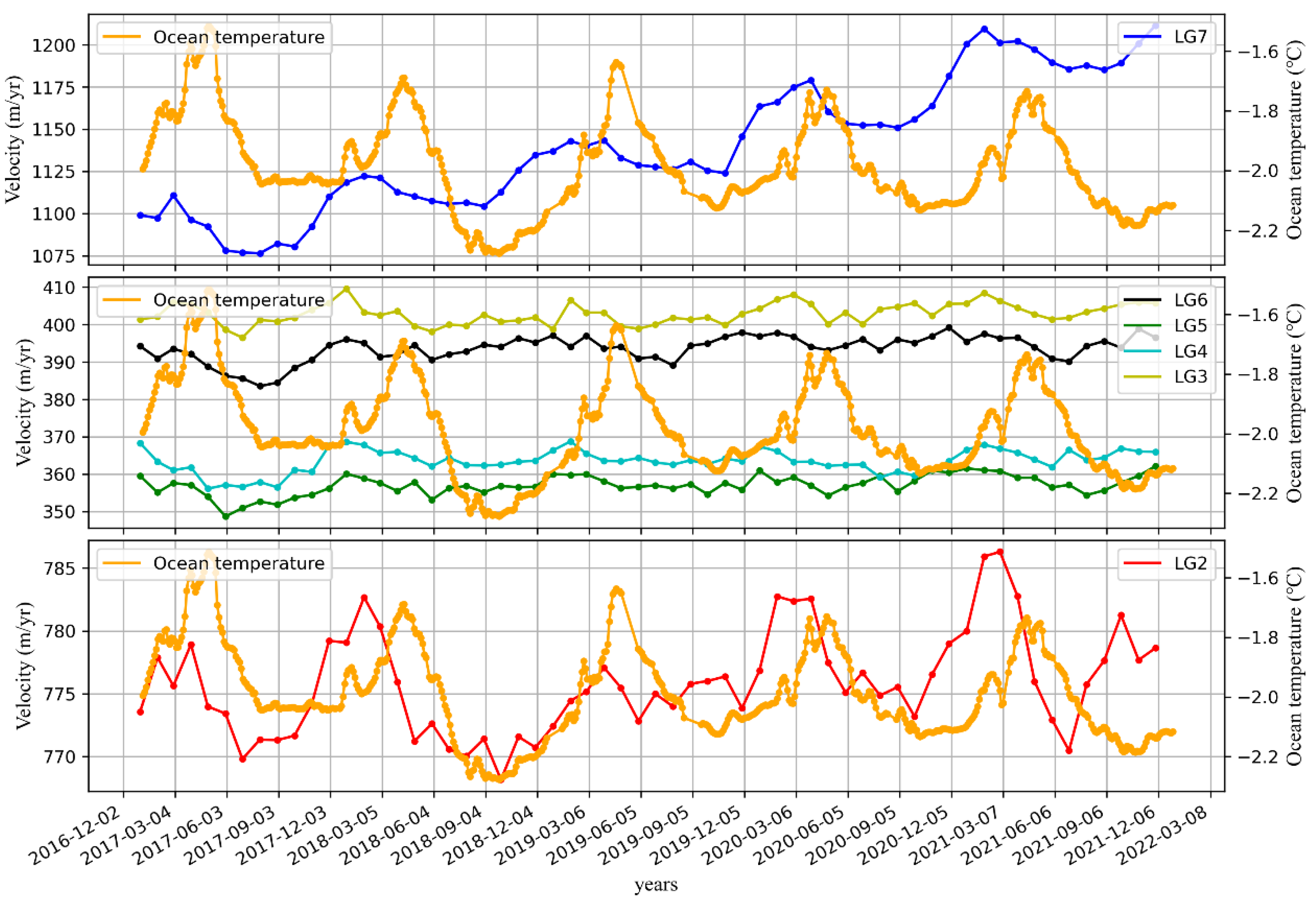

4.3. Effect of Ocean Temperatures on Seasonal Variations in Surface Velocity

Recent studies have demonstrated strong seasonal variation in the average ocean temperature of the AIS front (Galton-Fenzi, Hunter et al. 2012, Herraiz-Borreguero, Coleman et al. 2015, Wang, Zhou et al. 2023). There is usually an increase in ocean temperature from December to May of the following year, reaching a peak in June (> − 1.8 ), whereas the ocean temperature decreases from June to November, reaching a minimum in November (< − 2.1). As shown in

Figure 15, the present study examined the relationships between the ocean temperature of P3 (indicated as the red pentagram in

Figure 8) and the surface velocities at all monitoring points of the LG ice streamline from 2017 to 2021. The results showed that the variations in surface velocity at all monitoring points were positively correlated with variation in ocean temperature. The correlation coefficients between variation in ocean temperature of P3 and variations in surface velocity at LG7 and LG2 were 0.178 and 0.144, respectively; those between variations in ocean temperature at P3 and variations in surface velocity at LG3, LG4, LG5, and LG6 were 0.109, 0.102, 0.097, and 0.113, respectively. These results suggested that the front region of the AIS (LG7), characterized by a surface velocity of ~1,250 m/yr, is most sensitive to variation in ocean temperature, whereas the southernmost grounding line region (LG2), characterized by a surface velocity of ~750 m/yr, is relatively sensitive to variation in ocean temperature. The eastern side of the AIS (LG3–LG6), characterized by a surface velocity of between 350 m/yr and 400 m/yr, was the least sensitive to variation in ocean temperature. The results of the present study were in good agreement with those of other studies (Davies, Carrivick et al. 2012, Chi and Klein 2020) and showed that the speed of ice shelf flow was positively correlated to the sensitivity of the ice shelf to variation in the local environmental.

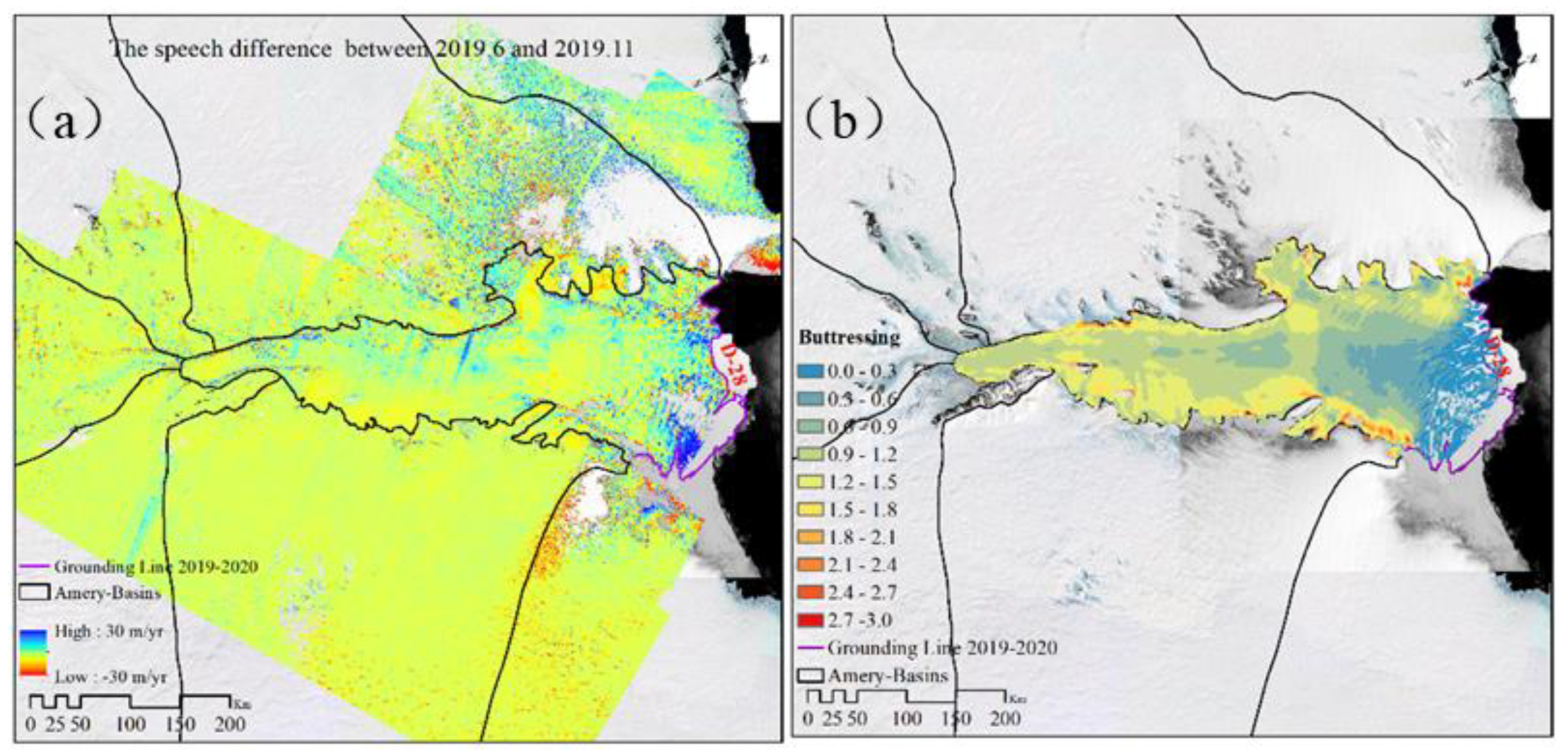

4.4. Effect of Ice Shelf Calving on Variation in Surface Velocity

Iceberg D-28 calved from the AIS front on the 25

th September, 2019. This calving event was the largest since the early 1960s (Francis, Mattingly et al. 2020). The present study analyzed the difference in surface velocity before (June, 2019) and after (November, 2019) the calving event. The results showed no significant difference in surface velocity before and after the event near the calved area (

Figure 16A). The buttressing effect on the stress regime within the ice was then quantified to investigate the response of surface velocity to the calving event (Gudmundsson 2013). At a maximum buttressing of , the calving event did not affect the variation in surface velocity of the ice shelf (Li, Liu et al. 2020). As shown in

Figure 16B, the maximum buttressing force of the calved area was less than 0.3. These results suggested that the area calved from the AIS was within a zone in which a calving event would not affect variation in the surface velocity of the AIS.

5. Conclusions

There inter-annual variation in the surface velocity of the AIS was spatially uneven from 2000 to 2022. There was a decrease in surface velocity in the central and western regions of the AIS, whereas that in the eastern region increased. Variation in surface velocity on the ice sheet was less than that of the ice shelf, which in turn was less than that of the ice shelf front. In addition, the ice sheet far from the southernmost grounding line of the AIS showed little variation in surface velocity from 2000 to 2022. These results could mainly be attributed to the contribution of the clockwise circulation of mCDW in the AIS ice cavity to basal melting of the eastern AIS, resulting in a decrease in ice thickness and increased surface velocity. The circulation process also contributed to basal refreezing of the central and western regions of AIS, resulting in an increased ice thickness and decreased surface velocity. There was no significant seasonal variation in monthly surface velocity in the central and western regions of the AIS, which may be related to the persistent Mackenzie polynya. The surface velocity of the eastern AIS front fluctuated seasonally under the combined effect of the area and thickness of fast-ice. In addition, the seasonal variation in ocean temperature was another factor influencing the seasonal variation in surface velocity in the eastern side of the AIS. The calving event on the AIS front on the 28th September, 2019, had no impact on the variation in surface velocity, which could be attributed to the location of the calved area on an insensitive area of the AIS front.

An investigation of the spatiotemporal variation in the surface velocity of the AIS basin and the underlying physical mechanism showed uneven inter-annual spatial variation in the surface velocity of the AIS basin. In addition, there was seasonal variation in the monthly average surface velocity of the eastern side of the AIS. However, the variation in the surface velocity of the AIS basin was of minimal magnitude, suggesting that the AIS basin has remained relatively stable over the past two decades.

Acknowledgments

We thank the ESA and ASF for providing Sentinel-1 SAR images and thank NASA for providing MODIS images. We are thankful for the National Snow & Ice Data Center (NSIDC) for publishing the ITS_LIVE ice velocity and the grounding line data. We also thankful for the Australian Space Weather Forecasting Center (ASWFC) for publishing the Geomagnetic Index Kp, auroral current aggregation index AU&AL and geomagnetic symmetric disturbance component SYM-H.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 41941010), the Hubei Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 2023AFB591), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (grant nos. 2042022kf1068), and the State Key Laboratory of Cryospheric Science, Northwest Institute of Eco-Environment and Resources, Chinese Academy Sciences (grant nos. SKLCS-OP-2021-07).

References

- Aoki, S., et al. (2022). “Warm surface waters increase Antarctic ice shelf melt and delay dense water formation.” Communications Earth & Environment 3(1). [CrossRef]

- Chi, Z. and A. G. Klein (2020). “Inter- and Intra-annual Surface Velocity Variations at the Southern Grounding Line of Amery Ice Shelf from 2014 to 2018.” The Cryosphere Discussions.

- Consortium, E., et al. (2021). Synopsis of the ECCO central production global ocean and sea-ice state estimate, version 4 release 4, Zenodo [data set].

- Davies, B. J., et al. (2012). “Variable glacier response to atmospheric warming, northern Antarctic Peninsula, 1988–2009.” The Cryosphere 6(5): 1031-1048.

- Dirscherl, M., et al. (2020). “Remote sensing of ice motion in Antarctica – A review.” Remote Sensing of Environment 237.

- Fanghui, D., et al. (2015). “Ice-flow Velocity Derivation of the Confluence Zone of the Amery Ice Shelf Using Offset-tracking Method.” Geomatics and Information Science of Wuhan University.

- Francis, D., et al. (2020). “Atmospheric extremes triggered the biggest calving event in more than 50 years at the Amery Ice shelf in September 2019.”.

- Fukumori, I., et al. (2019). Data sets used in ECCO Version 4 Release 3.

- Fürst, J. J., et al. (2016). “The safety band of Antarctic ice shelves.” Nature Climate Change 6(5): 479-482. [CrossRef]

- Galton-Fenzi, B. K., et al. (2012). “Modeling the basal melting and marine ice accretion of the Amery Ice Shelf.” Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans 117(C9). [CrossRef]

- Gardner, A. S., et al. (2018). “Increased West Antarctic and unchanged East Antarctic ice discharge over the last 7 years.” The Cryosphere 12(2): 521-547. [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Fell, R., et al. (2022). “Parker Ice Tongue Collapse, Antarctica, Triggered by Loss of Stabilizing Land-Fast Sea Ice.” Geophysical Research Letters 49(1).

- Gudmundsson, G. H. (2013). “Ice-shelf buttressing and the stability of marine ice sheets.” The Cryosphere 7(2): 647-655. [CrossRef]

- Han, H., et al. (2016). “Variations in ice velocities of Pine Island Glacier Ice Shelf evaluated using multispectral image matching of Landsat time series data.” Remote Sensing of Environment 186: 358-371. [CrossRef]

- Herraiz-Borreguero, L., et al. (2016). “Basal melt, seasonal water mass transformation, ocean current variability, and deep convection processes along the Amery Ice Shelf calving front, East Antarctica.” Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans 121(7): 4946-4965. [CrossRef]

- Herraiz-Borreguero, L., et al. (2015). “Circulation of modified Circumpolar Deep Water and basal melt beneath the Amery Ice Shelf, East Antarctica.” Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans 120(4): 3098-3112.

- Hoppmann, M., et al. (2015). “Seasonal evolution of an ice-shelf influenced fast-ice regime, derived from an autonomous thermistor chain.” Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans 120(3): 1703-1724.

- Jacobs, S., et al. (2013). “Getz Ice Shelf melting response to changes in ocean forcing.” Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans 118(9): 4152-4168. [CrossRef]

- Jawak, S. D., et al. (2019). “Seasonal Comparison of Velocity of the Eastern Tributary Glaciers, Amery Ice Shelf, Antarctica, Using Sar Offset Tracking.” ISPRS Annals of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences IV-2/W5: 595-600.

- Joughin, I., et al. (2017). “Glaciological advances made with interferometric synthetic aperture radar.” Journal of Glaciology 56(200): 1026-1042. [CrossRef]

- Kamel Hasni, J. C., Guo Wei (2017). “Correcting Ionospheric and Orbital Errors in Spaceborne SAR Differential Interferograms.” IEEE Xplore.

- Kumar, V. V. and M. L. Parkinson (2017). “A global scale picture of ionospheric peak electron density changes during geomagnetic storms.” Space Weather 15(4): 637-652. [CrossRef]

- Lee, S., et al. (2023). “Ice Velocity Variations of the Cook Ice Shelf, East Antarctica, from 2017 to 2022 from Sentinel-1 SAR Time-Series Offset Tracking.” Remote Sensing 15(12). [CrossRef]

- Lei, Y., et al. (2021). “Autonomous Repeat Image Feature Tracking (autoRIFT) and Its Application for Tracking Ice Displacement.” Remote Sensing 13(4). [CrossRef]

- Lei, Y., et al. (2022). “Processing methodology for the ITS_LIVE Sentinel-1 ice velocity products.” Earth System Science Data 14(11): 5111-5137. [CrossRef]

- Li, B., et al. (2020). “Ionospheric Phase Compensation for InSAR Measurements Based on the Faraday Rotation Inversion Method.” Sensors (Basel) 20(23). [CrossRef]

- Li, T., et al. (2020). “Recent and imminent calving events do little to impair Amery ice shelf’s stability.” Acta Oceanologica Sinica 39(5): 168-170. [CrossRef]

- Li, X., et al. (2020). “The spatio-temporal patterns of landfast ice in Antarctica during 2006–2011 and 2016–2017 using high-resolution SAR imagery.” Remote Sensing of Environment 242. [CrossRef]

- Liang, C., et al. (2019). “Ionospheric Correction of InSAR Time Series Analysis of C-band Sentinel-1 TOPS Data.” IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 57(9): 6755-6773. [CrossRef]

- Liang, Q. I., et al. (2019). “Ice flow variations at Polar Record Glacier, East Antarctica.” Journal of Glaciology 65(250): 279-287.

- Liao, H., et al. (2018). “Ionospheric correction of InSAR data for accurate ice velocity measurement at polar regions.” Remote Sensing of Environment 209: 166-180. [CrossRef]

- Liu, C., et al. (2018). “On the Modified Circumpolar Deep Water Upwelling Over the Four Ladies Bank in Prydz Bay, East Antarctica.” Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans 123(11): 7819-7838.

- Liu, C., et al. (2017). “Modeling modified Circumpolar Deep Water intrusions onto the Prydz Bay continental shelf, East Antarctica.” Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans 122(7): 5198-5217.

- Ma, Y., et al. (2022). “Ionospheric Correction of L-Band SAR Interferometry for Accurate Ice-Motion Measurements: A Case Study in the Grove Mountains Area, East Antarctica.” Remote Sensing 14(3). [CrossRef]

- Mallett, R. D. C., et al. (2021). “Faster decline and higher variability in the sea ice thickness of the marginal Arctic seas when accounting for dynamic snow cover.” The Cryosphere 15(5): 2429-2450. [CrossRef]

- Manson, R., et al. (2000). “Ice velocities of the Lambert Glacier from static GPS observations.” Earth Planets Space 52: 6.

- Mouginot, J., et al. (2019). “Continent-Wide, Interferometric SAR Phase, Mapping of Antarctic Ice Velocity.” Geophysical Research Letters 46(16): 9710-9718.

- Mouginot, J., et al. (2012). “Mapping of Ice Motion in Antarctica Using Synthetic-Aperture Radar Data.” Remote Sensing 4(9): 2753-2767. [CrossRef]

- Nagler, T., et al. (2015). “The Sentinel-1 Mission: New Opportunities for Ice Sheet Observations.” Remote Sensing 7(7): 9371-9389. [CrossRef]

- Nitsche, F. O., et al. (2013). “Paleo ice flow and subglacial meltwater dynamics in Pine Island Bay, West Antarctica.” Cryosphere 7(1): 249-262.

- Rignot, E., et al. (2022). “Changes in Antarctic Ice Sheet Motion Derived From Satellite Radar Interferometry Between 1995 and 2022.” Geophysical Research Letters 49(23). [CrossRef]

- Scambos, T. A., et al. (2004). “Glacier acceleration and thinning after ice shelf collapse in the Larsen B embayment, Antarctica.”. [CrossRef]

- Schubert, A., et al. (2013). “Glacier surface velocity estimation using repeat TerraSAR-X images: Wavelet- vs. correlation-based image matching.” ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing 82: 49-62.

- Shen, Q., et al. (2020). “Antarctic-wide annual ice flow maps from Landsat 8 imagery between 2013 and 2019.” International Journal of Digital Earth 14(5): 597-618. [CrossRef]

- Shen, Q., et al. (2018). “Recent high-resolution Antarctic ice velocity maps reveal increased mass loss in Wilkes Land, East Antarctica.” Sci Rep 8(1): 4477. [CrossRef]

- Tong, X., et al. (2018). “Multi-track extraction of two-dimensional surface velocity by the combined use of differential and multiple-aperture InSAR in the Amery Ice Shelf, East Antarctica.” Remote Sensing of Environment 204: 122-137. [CrossRef]

- Völz, V. and J. Hinkel (2023). “Sea Level Rise Learning Scenarios for Adaptive Decision-Making Based on IPCC AR6.” Earth’s Future 11(9). [CrossRef]

- Wang, T., et al. (2023). “Basal Channel System and Polynya Effect on a Regional Air-Ice-Ocean-Biology Environment System in the Prydz Bay, East Antarctica.” Journal of Geophysical Research: Earth Surface 128(9).

- Wang, X. and D. M. Holland (2020). “An Automatic Method for Black Margin Elimination of Sentinel-1A Images over Antarctica.” Remote Sensing 12(7). [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y., et al. (2021). “Deriving Antarctic Sea-Ice Thickness From Satellite Altimetry and Estimating Consistency for NASA’s ICESat/ICESat-2 Missions.” Geophysical Research Letters 48(20). [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B., et al. (2020). “Antarctic ice-shelf thickness changes from CryoSat-2 SARIn mode measurements: Assessment and comparison with IceBridge and ICESat.” 129: 1-15. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B., et al. (2020). “Elevation Changes of the Antarctic Ice Sheet from Joint Envisat and CryoSat-2 Radar Altimetry.” Remote Sensing 12(22). [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J., et al. (2020). “Fast Ice Prediction System (FIPS) for land-fast sea ice at Prydz Bay, East Antarctica: an operational service for CHINARE.” Annals of Glaciology 61(83): 271-283.

- Zhou, C., et al. (2019). “Mass Balance Assessment of the Amery Ice Shelf Basin, East Antarctica.” Earth and Space Science 6(10): 1987-1999.

- Zhou, C., et al. (2017). “Seasonal and interannual ice velocity changes of Polar Record Glacier, East Antarctica.” Annals of Glaciology 55(66): 45-51.

Figure 1.

The variations of Kp, AU&AL and SYM-H from the 31st January to 14th February, 2017. The green dashed line indicated the acquisition time of SAR image pairs from 19th January to 25th January, 2017, and the blue dash line indicates the acquisition time of SAR image pairs from the 31st January to 6th February, 2017.

Figure 1.

The variations of Kp, AU&AL and SYM-H from the 31st January to 14th February, 2017. The green dashed line indicated the acquisition time of SAR image pairs from 19th January to 25th January, 2017, and the blue dash line indicates the acquisition time of SAR image pairs from the 31st January to 6th February, 2017.

Figure 2.

Comparison interferometric phase with and without ionospheric correction. (A) and (E) show the interferogram without ionospheric correction, respectively. (B) and (F) show the relative ionospheric phase, respectively. (C) and (G) show the interferogram with ionospheric correction, respectively. The red dashed lines in (A) and (E) indicted the central profile lines and extract the interferometric phase without ionospheric correction, respectively. The blue dashed lines in (B) and (F) indicted the central profile lines and extract the ionospheric phase. respectively. The black dashed lines in (D) and (H) indicted the surface velocity with and without ionospheric correction of the central profile, respectively.

Figure 2.

Comparison interferometric phase with and without ionospheric correction. (A) and (E) show the interferogram without ionospheric correction, respectively. (B) and (F) show the relative ionospheric phase, respectively. (C) and (G) show the interferogram with ionospheric correction, respectively. The red dashed lines in (A) and (E) indicted the central profile lines and extract the interferometric phase without ionospheric correction, respectively. The blue dashed lines in (B) and (F) indicted the central profile lines and extract the ionospheric phase. respectively. The black dashed lines in (D) and (H) indicted the surface velocity with and without ionospheric correction of the central profile, respectively.

Figure 4.

AIS ice thickness and ice thickness change monitoring points. The background is MODIS image from 21th January, 2010. The solid gray line is the ground line.

Figure 4.

AIS ice thickness and ice thickness change monitoring points. The background is MODIS image from 21th January, 2010. The solid gray line is the ground line.

Figure 5.

The accuracy of ITS_LIVE annual average surface velocity of AIS basin from 2000 to 2022.

Figure 5.

The accuracy of ITS_LIVE annual average surface velocity of AIS basin from 2000 to 2022.

Figure 7.

Comparison surface velocity of DInSAR-based with and without ionospheric correction at FG0, MG0 and LG0 from 2017 to 2021.

Figure 7.

Comparison surface velocity of DInSAR-based with and without ionospheric correction at FG0, MG0 and LG0 from 2017 to 2021.

Figure 10.

Intra-annual surface velocity variations at eight monitoring points of the FG, MG and LG ice streamline from 2017 to 2021.

Figure 10.

Intra-annual surface velocity variations at eight monitoring points of the FG, MG and LG ice streamline from 2017 to 2021.

Figure 11.

The ECCO2 time series daily ocean temperatures of the AIS front region from 2000 to 2022.

Figure 11.

The ECCO2 time series daily ocean temperatures of the AIS front region from 2000 to 2022.

Figure 12.

Compared the inter-annual surface velocity change and ice thickness change at all monitoring points of FG, MG and LG ice streamlines from 2000 to 2022.

Figure 12.

Compared the inter-annual surface velocity change and ice thickness change at all monitoring points of FG, MG and LG ice streamlines from 2000 to 2022.

Figure 15.

Comparison between the P3 ocean temperature with the surface velocity at all monitoring points of the LG ice streamline from 2017 to 2021.

Figure 15.

Comparison between the P3 ocean temperature with the surface velocity at all monitoring points of the LG ice streamline from 2017 to 2021.

Figure 16.

(a) represents the difference of surface velocity before (June 2019) and after (November 2019) the ice shelf calved. (b) Maximum buttressing of AIS derived from (Fürst, Durand et al. 2016).

Figure 16.

(a) represents the difference of surface velocity before (June 2019) and after (November 2019) the ice shelf calved. (b) Maximum buttressing of AIS derived from (Fürst, Durand et al. 2016).

Table 1.

Comparison among three methods at rock points R1-R3 from 2017 to 2021.

Table 1.

Comparison among three methods at rock points R1-R3 from 2017 to 2021.

| Points |

R1 (m/yr) |

R2 (m/yr) |

R3(m/yr) |

| Methods |

(1) |

(2) |

(3) |

MEaSUREs |

(1) |

(2) |

(3) |

MEaSUREs |

(1) |

(2) |

(3) |

MEaSUREs |

| Mean |

1.77 |

0.25 |

2.8 |

1.74 |

1.84 |

0.20 |

3.2 |

1.16 |

1.68 |

0.28 |

3.82 |

1.43 |

| Standard |

1.81 |

0.28 |

1.28 |

0.23 |

1.73 |

0.21 |

2.03 |

0.16 |

1.75 |

0.15 |

2.56 |

0.17 |

Table 2.

Comparison the parameters of surface velocity among eight monitoring points on the LG ice streamline.

Table 2.

Comparison the parameters of surface velocity among eight monitoring points on the LG ice streamline.

| Monitoring points |

Maximum (m/yr) |

Minimum (m/yr) |

Magnitude (m/yr) |

| LG0 |

122.1 |

119.7 |

2.4 |

| LG1 |

397.5 |

394.8 |

2.7 |

| LG2 |

786.3 |

768.2 |

18.1 |

| LG3 |

398.2 |

409.64 |

11.5 |

| LG4 |

368.8 |

363.5 |

12.7 |

| LG5 |

362.1 |

350.1 |

12.0 |

| LG6 |

399.2 |

387.3 |

11.9 |

| LG7 |

1246.6 |

1076.1 |

170.5 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).