Submitted:

16 May 2024

Posted:

16 May 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Pathophysiology

3. Epidemiology of Lung Cancer in ILD

4. Diagnostic Approach to the Patients with ILD and Suspected Lung Cancer

5. Treatment of NSCLC in Patients with ILDs

5.1. Surgical Therapy

5.2. Radiation Therapy

5.3. Percutaneous Ablation

5.4. Systemic Therapy for Lung Cancer in Patients with ILDs

5.4.1. Chemotherapy

5.4.2. Immunotherapy

6. Treatment Options for SCLC Patients with ILD

7. Palliative Care

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wijsenbeek, M.; Suzuki, A.; Maher, T.M. Interstitial lung diseases. The Lancet 2022, 400, 769–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pardo, A.; Selman, M. The Interplay of the Genetic Architecture, Aging, and Environmental Factors in the Pathogenesis of Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. American Journal of Respiratory Cell and Molecular Biology 2021, 64, 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, Z.; Meng, Q.; Xu, J.; Wang, W.; Zhang, B.; Liu, J.; Liang, C.; Hua, J.; Zhao, Y.; Yu, X.; et al. Signaling pathways in cancer-associated fibroblasts: recent advances and future perspectives. Cancer Communications 2023, 43, 3–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karampitsakos, T.; Tzilas, V.; Tringidou, R.; Steiropoulos, P.; Aidinis, V.; Papiris, S.A.; Bouros, D.; Tzouvelekis, A. Lung cancer in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Pulmonary Pharmacology & Therapeutics 2017, 45, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniels, C.E.; Jett, J.R. Does interstitial lung disease predispose to lung cancer? Current Opinion in Pulmonary Medicine 2005, 11, 431–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Archontogeorgis, K.; Steiropoulos, P.; Tzouvelekis, A.; Nena, E.; Bouros, D. Lung cancer and interstitial lung diseases: a systematic review. Pulm Med 2012, 2012, 315918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ballester, B.; Milara, J.; Cortijo, J. Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis and Lung Cancer: Mechanisms and Molecular Targets. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2019, 20, 593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antoniou, K.M.; Tomassetti, S.; Tsitoura, E.; Vancheri, C. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and lung cancer. Current Opinion in Pulmonary Medicine 2015, 21, 626–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hendriks, L.E.L.; Drent, M.; van Haren, E.H.J.; Verschakelen, J.A.; Verleden, G.M. Lung cancer in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis patients diagnosed during or after lung transplantation. Respiratory Medicine Case Reports 2012, 5, 37–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzouvelekis, A.; Gomatou, G.; Bouros, E.; Trigidou, R.; Tzilas, V.; Bouros, D. Common Pathogenic Mechanisms Between Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis and Lung Cancer. Chest 2019, 156, 383–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Yang, M.; Li, P.; Su, Z.; Gao, P.; Zhang, J. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis will increase the risk of lung cancer. Chin Med J (Engl) 2014, 127, 3142–3149. [Google Scholar]

- Global Burden of Disease Cancer, C.; Kocarnik, J.M.; Compton, K.; Dean, F.E.; Fu, W.; Gaw, B.L.; Harvey, J.D.; Henrikson, H.J.; Lu, D.; Pennini, A.; et al. Cancer Incidence, Mortality, Years of Life Lost, Years Lived With Disability, and Disability-Adjusted Life Years for 29 Cancer Groups From 2010 to 2019: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. JAMA Oncol 2022, 8, 420–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collaborators, G.B.D.C.R.D. Global burden of chronic respiratory diseases and risk factors, 1990-2019: an update from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. EClinicalMedicine 2023, 59, 101936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raghu, G.; Collard, H.R.; Egan, J.J.; Martinez, F.J.; Behr, J.; Brown, K.K.; Colby, T.V.; Cordier, J.-F.; Flaherty, K.R.; Lasky, J.A.; et al. An Official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT Statement: Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis: Evidence-based Guidelines for Diagnosis and Management. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine 2011, 183, 788–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Wu, W.; Chen, N.; Song, H.; Lu, T.; Yang, Z.; Wang, Z.; Zhou, J.; Liu, L. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of lung cancer patients with combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 13 studies. Journal of Thoracic Disease 2017, 9, 5322–5334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todd, N.W.; Luzina, I.G.; Atamas, S.P. Molecular and cellular mechanisms of pulmonary fibrosis. Fibrogenesis & Tissue Repair 2012, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armanios, M.Y.; Chen, J.J.L.; Cogan, J.D.; Alder, J.K.; Ingersoll, R.G.; Markin, C.; Lawson, W.E.; Xie, M.; Vulto, I.; Phillips, J.A.; et al. Telomerase Mutations in Families with Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. New England Journal of Medicine 2007, 356, 1317–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demopoulos, K.; Arvanitis, D.A.; Vassilakis, D.A.; Siafakas, N.M.; Spandidos, D.A. MYCL1, FHIT, SPARC, p16 INK4 and TP53 genes associated to lung cancer in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Journal of Cellular and Molecular Medicine 2002, 6, 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Chung, M.J.; Ullenbruch, M.; Yu, H.; Jin, H.; Hu, B.; Choi, Y.Y.; Ishikawa, F.; Phan, S.H. Telomerase activity is required for bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis in mice. Journal of Clinical Investigation 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selman, M.; Pardo, A. Role of epithelial cells in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: from innocent targets to serial killers. Proc Am Thorac Soc 2006, 3, 364–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O'Callaghan, D.S.; O'Donnell, D.; O'Connell, F.; O'Byrne, K.J. The Role of Inflammation in the Pathogenesis of Non-small Cell Lung Cancer. Journal of Thoracic Oncology 2010, 5, 2024–2036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jenkins, R.G.; Simpson, J.K.; Saini, G.; Bentley, J.H.; Russell, A.-M.; Braybrooke, R.; Molyneaux, P.L.; McKeever, T.M.; Wells, A.U.; Flynn, A.; et al. Longitudinal change in collagen degradation biomarkers in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: an analysis from the prospective, multicentre PROFILE study. The Lancet Respiratory Medicine 2015, 3, 462–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandez, I.E.; Eickelberg, O. The Impact of TGF-β on Lung Fibrosis. Proceedings of the American Thoracic Society 2012, 9, 111–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selman, M.s.; Thannickal, V.J.; Pardo, A.; Zisman, D.A.; Martinez, F.J.; Lynch, J.P. Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Drugs 2004, 64, 405–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oikonomidi, I.; Burbridge, E.; Cavadas, M.; Sullivan, G.; Collis, B.; Naegele, H.; Clancy, D.; Brezinova, J.; Hu, T.; Bileck, A.; et al. iTAP, a novel iRhom interactor, controls TNF secretion by policing the stability of iRhom/TACE. eLife 2018, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grimminger, F.; Schermuly, R.T.; Ghofrani, H.A. Targeting non-malignant disorders with tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery 2010, 9, 956–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rabinovich, E.I.; Kapetanaki, M.G.; Steinfeld, I.; Gibson, K.F.; Pandit, K.V.; Yu, G.; Yakhini, Z.; Kaminski, N. Global Methylation Patterns in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e33770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Yu, N.; Lee, C. Mysteries of TGF-b Paradox in Benign and Malignant Cells. Frontiers in Oncology 2014, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malli, F.; Koutsokera, A.; Paraskeva, E.; Zakynthinos, E.; Papagianni, M.; Makris, D.; Tsilioni, I.; Molyvdas, P.A.; Gourgoulianis, K.I.; Daniil, Z. Endothelial Progenitor Cells in the Pathogenesis of Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis: An Evolving Concept. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e53658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu Qubo, A.; Numan, J.; Snijder, J.; Padilla, M.; Austin, J.H.M.; Capaccione, K.M.; Pernia, M.; Bustamante, J.; O'Connor, T.; Salvatore, M.M. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and lung cancer: future directions and challenges. Breathe 2022, 18, 220147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinoshita, T.; Goto, T. Molecular Mechanisms of Pulmonary Fibrogenesis and Its Progression to Lung Cancer: A Review. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2019, 20, 1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patsoukis, N.; Wang, Q.; Strauss, L.; Boussiotis, V.A. Revisiting the PD-1 pathway. Science Advances 2020, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Organ, S.L.; Tsao, M.-S. An overview of the c-MET signaling pathway. Therapeutic Advances in Medical Oncology 2011, 3, S7–S19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stella, G.M.; Gentile, A.; Balderacchi, A.; Meloni, F.; Milan, M.; Benvenuti, S. Ockham’s razor for the MET-driven invasive growth linking idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and cancer. Journal of Translational Medicine 2016, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuwano, K.; Araya, J.; Hara, H.; Minagawa, S.; Takasaka, N.; Ito, S.; Kobayashi, K.; Nakayama, K. Cellular senescence and autophagy in the pathogenesis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF). Respiratory Investigation 2016, 54, 397–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cancer Genome Atlas Research, N. Comprehensive molecular profiling of lung adenocarcinoma. Nature 2014, 511, 543–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kidera, Y.; van Tsubaki, M.; Yamazoe, Y.; Shoji, K.; Nakamura, H.; Ogaki, M.; Satou, T.; Itoh, T.; Isozaki, M.; Kaneko, J.; et al. Reduction of lung metastasis, cell invasion, and adhesion in mouse melanoma by statin-induced blockade of the Rho/Rho-associated coiled-coil-containing protein kinase pathway. Journal of Experimental & Clinical Cancer Research 2010, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.K.; Kugler, M.C.; Wolters, P.J.; Robillard, L.; Galvez, M.G.; Brumwell, A.N.; Sheppard, D.; Chapman, H.A. Alveolar epithelial cell mesenchymal transition develops in vivo during pulmonary fibrosis and is regulated by the extracellular matrix. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2006, 103, 13180–13185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovat, F.; Valeri, N.; Croce, C.M. MicroRNAs in the Pathogenesis of Cancer. Seminars in Oncology 2011, 38, 724–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarzenbach, H.; Hoon, D.S.B.; Pantel, K. Cell-free nucleic acids as biomarkers in cancer patients. Nature Reviews Cancer 2011, 11, 426–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trovato-Salinaro, A.; Trovato-Salinaro, E.; Failla, M.; Mastruzzo, C.; Tomaselli, V.; Gili, E.; Crimi, N.; Condorelli, F.D.; Vancheri, C. Altered intercellular communication in lung fibroblast cultures from patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Respiratory Research 2006, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, H.I.; Park, J.S.; Lee, M.Y.; Park, B.; Kim, H.J.; Park, S.H.; Choi, W.I.; Lee, C.W. Prevalence of lung cancer in patients with interstitial lung disease is higher than in those with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Medicine (Baltimore) 2018, 97, e0071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, W.I.; Lee, D.Y.; Choi, H.G.; Lee, C.W. Lung Cancer development and mortality in interstitial lung disease with and without connective tissue diseases: a five-year Nationwide population-based study. Respir Res 2019, 20, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, J.H.; Nouraie, M.; Chen, X.; Zou, R.H.; Sellares, J.; Veraldi, K.L.; Chiarchiaro, J.; Lindell, K.; Wilson, D.O.; Kaminski, N.; et al. Characteristics of lung cancer among patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and interstitial lung disease - analysis of institutional and population data. Respir Res 2018, 19, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, M.H.; Cho, J.H.; Eun, Y.; Han, K.; Jung, J.; Cho, I.Y.; Yoo, J.E.; Lee, H.; Kim, H.; Park, S.Y.; et al. Rheumatoid Arthritis and Risk of Lung Cancer: A Nationwide Cohort Study. J Thorac Oncol 2024, 19, 216–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kakutani, T.; Hashimoto, A.; Tominaga, A.; Kodama, K.; Nogi, S.; Tsuno, H.; Ogihara, H.; Nunokawa, T.; Komiya, A.; Furukawa, H.; et al. Related factors, increased mortality and causes of death in patients with rheumatoid arthritis-associated interstitial lung disease. Mod Rheumatol 2020, 30, 458–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whittaker Brown, S.A.; Padilla, M.; Mhango, G.; Powell, C.; Salvatore, M.; Henschke, C.; Yankelevitz, D.; Sigel, K.; de-Torres, J.P.; Wisnivesky, J. Interstitial Lung Abnormalities and Lung Cancer Risk in the National Lung Screening Trial. Chest 2019, 156, 1195–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axelsson, G.T.; Putman, R.K.; Aspelund, T.; Gudmundsson, E.F.; Hida, T.; Araki, T.; Nishino, M.; Hatabu, H.; Gudnason, V.; Hunninghake, G.M.; et al. The associations of interstitial lung abnormalities with cancer diagnoses and mortality. Eur Respir J 2020, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittaker Brown, S.A.; Padilla, M.; Mhango, G.; Taioli, E.; Powell, C.; Wisnivesky, J. Outcomes of Older Patients with Pulmonary Fibrosis and Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2019, 16, 1034–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S.W.; Dobelle, M.; Padilla, M.; Agovino, M.; Wisnivesky, J.P.; Hashim, D.; Boffetta, P. Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis and Lung Cancer. A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2019, 16, 1041–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.J.; Kim, S.Y.; Park, M.S.; Kang, M.J.; Lee, S.H.; Park, S.C. A nationwide population-based study of incidence and mortality of lung cancer in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Sci Rep 2021, 11, 2596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karampitsakos, T.; Spagnolo, P.; Mogulkoc, N.; Wuyts, W.A.; Tomassetti, S.; Bendstrup, E.; Molina-Molina, M.; Manali, E.D.; Unat, O.S.; Bonella, F.; et al. Lung cancer in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: A retrospective multicentre study in Europe. Respirology 2023, 28, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, H.; Jeong, B.H.; Chung, M.J.; Lee, K.S.; Kwon, O.J.; Chung, M.P. Risk factors and clinical characteristics of lung cancer in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Pulm Med 2019, 19, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozawa, Y.; Suda, T.; Naito, T.; Enomoto, N.; Hashimoto, D.; Fujisawa, T.; Nakamura, Y.; Inui, N.; Nakamura, H.; Chida, K. Cumulative incidence of and predictive factors for lung cancer in IPF. Respirology 2009, 14, 723–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Jeune, I.; Gribbin, J.; West, J.; Smith, C.; Cullinan, P.; Hubbard, R. The incidence of cancer in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and sarcoidosis in the UK. Respir Med 2007, 101, 2534–2540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barczi, E.; Nagy, T.; Starobinski, L.; Kolonics-Farkas, A.; Eszes, N.; Bohacs, A.; Tarnoki, A.D.; Tarnoki, D.L.; Muller, V. Impact of interstitial lung disease and simultaneous lung cancer on therapeutic possibilities and survival. Thorac Cancer 2020, 11, 1911–1917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watanabe, S.; Saeki, K.; Waseda, Y.; Murata, A.; Takato, H.; Ichikawa, Y.; Yasui, M.; Kimura, H.; Hamaguchi, Y.; Matsushita, T.; et al. Lung cancer in connective tissue disease-associated interstitial lung disease: clinical features and impact on outcomes. J Thorac Dis 2018, 10, 799–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, J.; Jiang, Y. Meta-analysis: clinical features and treatments of lung cancer in combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis 2023, 40, e2023045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, H.J.; Do, K.H.; Lee, J.B.; Alblushi, S.; Lee, S.M. Lung Cancer in Combined Pulmonary Fibrosis and Emphysema: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS One 2016, 11, e0161437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomassetti, S.; Gurioli, C.; Ryu, J.H.; Decker, P.A.; Ravaglia, C.; Tantalocco, P.; Buccioli, M.; Piciucchi, S.; Sverzellati, N.; Dubini, A.; et al. The impact of lung cancer on survival of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Chest 2015, 147, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masai, K.; Tsuta, K.; Motoi, N.; Shiraishi, K.; Furuta, K.; Suzuki, S.; Asakura, K.; Nakagawa, K.; Sakurai, H.; Watanabe, S.I.; et al. Clinicopathological, Immunohistochemical, and Genetic Features of Primary Lung Adenocarcinoma Occurring in the Setting of Usual Interstitial Pneumonia Pattern. J Thorac Oncol 2016, 11, 2141–2149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watanabe, Y.; Kawabata, Y.; Koyama, N.; Ikeya, T.; Hoshi, E.; Takayanagi, N.; Koyama, S. A clinicopathological study of surgically resected lung cancer in patients with usual interstitial pneumonia. Respir Med 2017, 129, 158–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.C.; Lee, S.; Song, J.W. Impact of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis on clinical outcomes of lung cancer patients. Sci Rep 2021, 11, 8312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mauclet, C.; Dupont, M.V.; Roelandt, K.; Regnier, M.; Delos, M.; Pirard, L.; Vander Borght, T.; Dahlqvist, C.; Froidure, A.; Rondelet, B.; et al. Treatment and Prognosis of Patients with Lung Cancer and Combined Interstitial Lung Disease. Cancers (Basel) 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alomaish, H.; Ung, Y.; Wang, S.; Tyrrell, P.N.; Zahra, S.A.; Oikonomou, A. Survival analysis in lung cancer patients with interstitial lung disease. PLoS One 2021, 16, e0255375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azuma, Y.; Sakamoto, S.; Homma, S.; Sano, A.; Sakai, T.; Koezuka, S.; Otsuka, H.; Tochigi, N.; Kishi, K.; Iyoda, A. Impact of accurate diagnosis of interstitial lung diseases on postoperative outcomes in lung cancer. Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2023, 71, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeda, H.; Kanzaki, M.; Sakamoto, K.; Isaka, T.; Oyama, K.; Murasugi, M.; Onuki, T. Effect of collagen vascular disease-associated interstitial lung disease on the outcomes of lung cancer surgery. Surg Today 2017, 47, 1072–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreuter, M.; Ehlers-Tenenbaum, S.; Schaaf, M.; Oltmanns, U.; Palmowski, K.; Hoffmann, H.; Schnabel, P.A.; Heussel, C.P.; Puderbach, M.; Herth, F.J.; et al. Treatment and outcome of lung cancer in idiopathic interstitial pneumonias. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis 2015, 31, 266–274. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tzouvelekis, A.; Spagnolo, P.; Bonella, F.; Vancheri, C.; Tzilas, V.; Crestani, B.; Kreuter, M.; Bouros, D. Patients with IPF and lung cancer: diagnosis and management. Lancet Respir Med 2018, 6, 86–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bueno, J.; Landeras, L.; Chung, J.H. Updated Fleischner Society Guidelines for Managing Incidental Pulmonary Nodules: Common Questions and Challenging Scenarios. Radiographics 2018, 38, 1337–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naccache, J.M.; Gibiot, Q.; Monnet, I.; Antoine, M.; Wislez, M.; Chouaid, C.; Cadranel, J. Lung cancer and interstitial lung disease: a literature review. J Thorac Dis 2018, 10, 3829–3844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sgalla, G.; Larici, A.R.; Golfi, N.; Calvello, M.; Farchione, A.; Del Ciello, A.; Varone, F.; Iovene, B.; Manfredi, R.; Richeldi, L. Mediastinal lymph node enlargement in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: relationships with disease progression and pulmonary function trends. BMC Pulm Med 2020, 20, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karampitsakos, T.; Galaris, A.; Chrysikos, S.; Papaioannou, O.; Vamvakaris, I.; Barbayianni, I.; Kanellopoulou, P.; Grammenoudi, S.; Anagnostopoulos, N.; Stratakos, G.; et al. Expression of PD-1/PD-L1 axis in mediastinal lymph nodes and lung tissue of human and experimental lung fibrosis indicates a potential therapeutic target for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Respir Res 2023, 24, 279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeon, T.Y.; Lee, K.S.; Yi, C.A.; Chung, M.P.; Kwon, O.J.; Kim, B.T.; Shim, Y.M. Incremental value of PET/CT Over CT for mediastinal nodal staging of non-small cell lung cancer: Comparison between patients with and without idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2010, 195, 370–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.H.; Sung, C.; Lee, H.S.; Yoon, H.Y.; Kim, S.J.; Oh, J.S.; Song, J.W.; Kim, M.Y.; Ryu, J.S. Is (18)F-FDG PET/CT useful for the differential diagnosis of solitary pulmonary nodules in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis? Ann Nucl Med 2018, 32, 492–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nomura, K.; Fukui, M.; Hattori, A.; Matsunaga, T.; Takamochi, K.; Suzuki, K. Diagnostic Value of Nodal Staging of Lung Cancer With Usual Interstitial Pneumonia Using PET. Ann Thorac Surg 2022, 114, 2073–2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.; Kim, C.; Seol, H.Y.; Chung, H.S.; Mok, J.; Lee, G.; Jo, E.J.; Kim, M.H.; Lee, K.; Kim, K.U.; et al. Safety and Diagnostic Yield of Radial Probe Endobronchial Ultrasound-Guided Biopsy for Peripheral Lung Lesions in Patients with Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis: A Multicenter Cross-Sectional Study. Respiration 2022, 101, 401–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nogawa, H.; Matsumoto, Y.; Tanaka, M.; Tsuchida, T. Diagnostic usefulness of bronchoscopy for peripheral pulmonary lesions in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. J Thorac Dis 2021, 13, 6304–6313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, Y.J.; Yun, G.; Yoon, S.H.; Song, H.; Kim, J.; Kim, J.; Park, J.S.; Lee, K.W.; Lee, K.H. Accuracy and complications of percutaneous transthoracic needle lung biopsy for the diagnosis of malignancy in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Eur Radiol 2021, 31, 9000–9011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tzouvelekis, A.; Antoniou, K.; Kreuter, M.; Evison, M.; Blum, T.G.; Poletti, V.; Grigoriu, B.; Vancheri, C.; Spagnolo, P.; Karampitsakos, T.; et al. The DIAMORFOSIS (DIAgnosis and Management Of lung canceR and FibrOSIS) survey: international survey and call for consensus. ERJ Open Res 2021, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Sun, Y.G.; Ma, C.; Jiao, P.; Wu, Q.J.; Tian, W.X.; Yu, H.B.; Tong, H.F. Surgical outcomes and perioperative risk factors of patients with interstitial lung disease after pulmonary resection. J Cardiothorac Surg 2024, 19, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Axtell, A.L.; David, E.A.; Block, M.I.; Parsons, N.; Habib, R.; Muniappan, A. Association Between Interstitial Lung Disease and Outcomes After Lung Cancer Resection. Ann Thorac Surg 2023, 116, 533–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, P.; Goldstraw, P.; Yamada, K.; Nicholson, A.G.; Wells, A.U.; Hansell, D.M.; Dubois, R.M.; Ladas, G. Pulmonary fibrosis and lung cancer: risk and benefit analysis of pulmonary resection. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2003, 125, 1321–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.S.; Kim, H.K.; Kim, K.; Kim, J.; Shim, Y.M.; Choi, Y.S. Prediction of acute pulmonary complications after resection of lung cancer in patients with preexisting interstitial lung disease. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2011, 59, 148–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sato, T.; Teramukai, S.; Kondo, H.; Watanabe, A.; Ebina, M.; Kishi, K.; Fujii, Y.; Mitsudomi, T.; Yoshimura, M.; Maniwa, T.; et al. Impact and predictors of acute exacerbation of interstitial lung diseases after pulmonary resection for lung cancer. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2014, 147, 1604–1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otsuka, H.; Sugino, K.; Hata, Y.; Makino, T.; Koezuka, S.; Isobe, K.; Tochigi, N.; Shibuya, K.; Homma, S.; Iyoda, A. Clinical features and outcomes of patients with lung cancer as well as combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema. Mol Clin Oncol 2016, 5, 273–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ki, M.S.; Kim, S.Y.; Kim, E.Y.; Jung, J.Y.; Kang, Y.A.; Park, M.S.; Kim, Y.S.; Park, S.Y.; Lee, S.H. Clinical Outcomes and Prognosis of Patients With Interstitial Lung Disease Undergoing Lung Cancer Surgery: A Propensity Score Matching Study. Clin Lung Cancer 2023, 24, e27–e38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ueno, F.; Kitaguchi, Y.; Shiina, T.; Asaka, S.; Yasuo, M.; Wada, Y.; Kinjo, T.; Yoshizawa, A.; Hanaoka, M. The Interstitial Lung Disease-Gender-Age-Physiology Index Can Predict the Prognosis in Surgically Resected Patients with Interstitial Lung Disease and Concomitant Lung Cancer. Respiration 2020, 99, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsutani, Y.; Mimura, T.; Kai, Y.; Ito, M.; Misumi, K.; Miyata, Y.; Okada, M. Outcomes after lobar versus sublobar resection for clinical stage I non-small cell lung cancer in patients with interstitial lung disease. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2017, 154, 1089–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motono, N.; Ishikawa, M.; Iwai, S.; Iijima, Y.; Uramoto, H. Interstitial lung disease and wedge resection are poor prognostic factors for non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Dis 2022, 14, 1052–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, K.; Tsutani, Y.; Wakabayashi, M.; Mizutani, T.; Aokage, K.; Miyata, Y.; Kuroda, H.; Saji, H.; Watanabe, S.I.; Okada, M.; et al. Sublobar resection versus lobectomy for patients with resectable stage I non-small cell lung cancer with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a phase III study evaluating survival (JCOG1708, SURPRISE). Jpn J Clin Oncol 2020, 50, 1076–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, A.J.; Walters, G.I.; Watkins, S.; Rogers, V.; Fallouh, H.; Kalkat, M.; Naidu, B.; Bishay, E.S. Lung cancer resection in patients with underlying usual interstitial pneumonia: a meta-analysis. BMJ Open Respir Res 2023, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukui, M.; Takamochi, K.; Suzuki, K.; Hotta, A.; Ando, K.; Matsunaga, T.; Oh, S.; Suzuki, K. Lobe-specific outcomes of surgery for lung cancer patients with idiopathic interstitial pneumonias. Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2020, 68, 812–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, S.; Shimizu, Y.; Goto, T.; Kitahara, A.; Koike, T.; Ishikawa, H.; Watanabe, T.; Tsuchida, M. Survival after repeated surgery for lung cancer with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a retrospective study. BMC Pulm Med 2018, 18, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwata, T.; Yoshino, I.; Yoshida, S.; Ikeda, N.; Tsuboi, M.; Asato, Y.; Katakami, N.; Sakamoto, K.; Yamashita, Y.; Okami, J.; et al. A phase II trial evaluating the efficacy and safety of perioperative pirfenidone for prevention of acute exacerbation of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in lung cancer patients undergoing pulmonary resection: West Japan Oncology Group 6711 L (PEOPLE Study). Respir Res 2016, 17, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanayama, M.; Mori, M.; Matsumiya, H.; Taira, A.; Shinohara, S.; Kuwata, T.; Imanishi, N.; Yoneda, K.; Kuroda, K.; Tanaka, F. Perioperative pirfenidone treatment for lung cancer patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Surg Today 2020, 50, 469–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakairi, Y.; Yoshino, I.; Iwata, T.; Yoshida, S.; Kuwano, K.; Azuma, A.; Sakai, S.; Kobayashi, K. A randomized controlled phase III trial protocol: perioperative pirfenidone therapy in patients with non-small cell lung cancer combined with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis to confirm the preventative effect against postoperative acute exacerbation: the PIII-PEOPLE study (NEJ034). J Thorac Dis 2023, 15, 1486–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ettinger, D.S.; Wood, D.E.; Aisner, D.L.; Akerley, W.; Bauman, J.R.; Bharat, A.; Bruno, D.S.; Chang, J.Y.; Chirieac, L.R.; D'Amico, T.A.; et al. Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer, Version 3.2022, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2022, 20, 497–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remon, J.; Soria, J.C.; Peters, S.; clinicalguidelines@esmo. org, E.G.C.E.a. Early and locally advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: an update of the ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines focusing on diagnosis, staging, systemic and local therapy. Ann Oncol 2021, 32, 1637–1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dingemans, A.C.; Fruh, M.; Ardizzoni, A.; Besse, B.; Faivre-Finn, C.; Hendriks, L.E.; Lantuejoul, S.; Peters, S.; Reguart, N.; Rudin, C.M.; et al. Small-cell lung cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up(☆). Ann Oncol 2021, 32, 839–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanic, S.; Paulus, R.; Timmerman, R.D.; Michalski, J.M.; Barriger, R.B.; Bezjak, A.; Videtic, G.M.; Bradley, J. No clinically significant changes in pulmonary function following stereotactic body radiation therapy for early- stage peripheral non-small cell lung cancer: an analysis of RTOG 0236. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2014, 88, 1092–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, A.; Dickinson, P.; Shrimali, R.K.; Salem, A.; Agarwal, S. Is Thoracic Radiotherapy an Absolute Contraindication for Treatment of Lung Cancer Patients With Interstitial Lung Disease? A Systematic Review. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2022, 34, e493–e504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glick, D.; Lyen, S.; Kandel, S.; Shapera, S.; Le, L.W.; Lindsay, P.; Wong, O.; Bezjak, A.; Brade, A.; Cho, B.C.J.; et al. Impact of Pretreatment Interstitial Lung Disease on Radiation Pneumonitis and Survival in Patients Treated With Lung Stereotactic Body Radiation Therapy (SBRT). Clin Lung Cancer 2018, 19, e219–e226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bahig, H.; Filion, E.; Vu, T.; Chalaoui, J.; Lambert, L.; Roberge, D.; Gagnon, M.; Fortin, B.; Beliveau-Nadeau, D.; Mathieu, D.; et al. Severe radiation pneumonitis after lung stereotactic ablative radiation therapy in patients with interstitial lung disease. Pract Radiat Oncol 2016, 6, 367–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okubo, M.; Itonaga, T.; Saito, T.; Shiraishi, S.; Mikami, R.; Nakayama, H.; Sakurada, A.; Sugahara, S.; Koizumi, K.; Tokuuye, K. Predicting risk factors for radiation pneumonitis after stereotactic body radiation therapy for primary or metastatic lung tumours. Br J Radiol 2017, 90, 20160508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Pyo, H.; Noh, J.M.; Lee, W.; Park, B.; Park, H.Y.; Yoo, H. Preliminary result of definitive radiotherapy in patients with non-small cell lung cancer who have underlying idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: comparison between X-ray and proton therapy. Radiat Oncol 2019, 14, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, F.; Liu, H.; Wu, H.; Liang, S.; Xu, Y. Risk factors for radiation pneumonitis in lung cancer patients with subclinical interstitial lung disease after thoracic radiation therapy. Radiat Oncol 2021, 16, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozawa, Y.; Abe, T.; Omae, M.; Matsui, T.; Kato, M.; Hasegawa, H.; Enomoto, Y.; Ishihara, T.; Inui, N.; Yamada, K.; et al. Impact of Preexisting Interstitial Lung Disease on Acute, Extensive Radiation Pneumonitis: Retrospective Analysis of Patients with Lung Cancer. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0140437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo, R.; Pham, N.; Ansari, S.; Meshkov, D.; Castillo, S.; Li, M.; Olanrewaju, A.; Hobbs, B.; Castillo, E.; Guerrero, T. Pre-radiotherapy FDG PET predicts radiation pneumonitis in lung cancer. Radiat Oncol 2014, 9, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yang, F.; Huang, Y.Y.; Wang, T. Sublobar resection versus ablation for stage I non-small-cell lung cancer: a meta-analysis. J Cardiothorac Surg 2022, 17, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupuy, D.E.; Fernando, H.C.; Hillman, S.; Ng, T.; Tan, A.D.; Sharma, A.; Rilling, W.S.; Hong, K.; Putnam, J.B. Radiofrequency ablation of stage IA non-small cell lung cancer in medically inoperable patients: Results from the American College of Surgeons Oncology Group Z4033 (Alliance) trial. Cancer 2015, 121, 3491–3498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, J.; Bie, Z.; Li, Y.; Guo, R.; Li, X. Safety and efficacy of CT-guided percutaneous microwave ablation for stage I non-small cell lung cancer in patients with comorbid idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Eur Radiol 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kashima, M.; Yamakado, K.; Takaki, H.; Kodama, H.; Yamada, T.; Uraki, J.; Nakatsuka, A. Complications after 1000 lung radiofrequency ablation sessions in 420 patients: a single center's experiences. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2011, 197, W576–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Senan, S.; Nossent, E.J.; Boldt, R.G.; Warner, A.; Palma, D.A.; Louie, A.V. Treatment-Related Toxicity in Patients With Early-Stage Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer and Coexisting Interstitial Lung Disease: A Systematic Review. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2017, 98, 622–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Bie, Z.; Li, Y.; Guo, R.; Wang, C.; Li, X. Synchronous percutaneous core-needle biopsy and microwave ablation for stage I non-small cell lung cancer in patients with Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: initial experience. Int J Hyperthermia 2023, 40, 2270793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.; Jaiyesimi, I.A.; Ismaila, N.; Leighl, N.B.; Mamdani, H.; Phillips, T.; Owen, D.H. Therapy for Stage IV Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer Without Driver Alterations: ASCO Living Guideline, Version 2023.1. J Clin Oncol 2023, 41, e51–e62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.; Jaiyesimi, I.A.; Ismaila, N.; Leighl, N.B.; Mamdani, H.; Phillips, T.; Owen, D.H. Therapy for Stage IV Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer With Driver Alterations: ASCO Living Guideline, Version 2023.1. J Clin Oncol 2023, 41, e42–e50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otsubo, K.; Kishimoto, J.; Ando, M.; Kenmotsu, H.; Minegishi, Y.; Horinouchi, H.; Kato, T.; Ichihara, E.; Kondo, M.; Atagi, S.; et al. Nintedanib plus chemotherapy for nonsmall cell lung cancer with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a randomised phase 3 trial. Eur Respir J 2022, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenmotsu, H.; Naito, T.; Kimura, M.; Ono, A.; Shukuya, T.; Nakamura, Y.; Tsuya, A.; Kaira, K.; Murakami, H.; Takahashi, T.; et al. The risk of cytotoxic chemotherapy-related exacerbation of interstitial lung disease with lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol 2011, 6, 1242–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Bai, J.; Liu, Y.; Li, P.; Jiao, G. Risk factors for acute exacerbation of interstitial lung disease during chemotherapy for lung cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Oncol 2023, 13, 1250688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akaike, K.; Saruwatari, K.; Matsushima, R.; Fujino, K.; Morinaga, J.; Oda, S.; Takahashi, H.; Shiraishi, S.; Okabayashi, H.; Hamada, S.; et al. Clinical impact of SUV(max) of interstitial lesions in lung cancer patients with interstitial lung disease who underwent pulmonary resection. J Thorac Dis 2022, 14, 3801–3810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Miao, L.; Hu, Y.; Zhou, Y. The Efficacy and Safety of First-Line Chemotherapy in Patients With Non-small Cell Lung Cancer and Interstitial Lung Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front Oncol 2020, 10, 1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujita, T.; Kuroki, T.; Hayama, N.; Shiraishi, Y.; Amano, H.; Nakamura, M.; Hirano, S.; Tabeta, H.; Nakamura, S. Pemetrexed Plus Platinum for Patients With Advanced Non-small Cell Lung Cancer and Interstitial Lung Disease. In Vivo 2019, 33, 2059–2064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kato, M.; Shukuya, T.; Takahashi, F.; Mori, K.; Suina, K.; Asao, T.; Kanemaru, R.; Honma, Y.; Muraki, K.; Sugano, K.; et al. Pemetrexed for advanced non-small cell lung cancer patients with interstitial lung disease. BMC Cancer 2014, 14, 508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suh, C.H.; Kim, K.W.; Pyo, J.; Hatabu, H.; Nishino, M. The incidence of ALK inhibitor-related pneumonitis in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lung Cancer 2019, 132, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johkoh, T.; Sakai, F.; Kusumoto, M.; Arakawa, H.; Harada, R.; Ueda, M.; Kudoh, S.; Fukuoka, M. Association between baseline pulmonary status and interstitial lung disease in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer treated with erlotinib--a cohort study. Clin Lung Cancer 2014, 15, 448–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhillon, S. Nintedanib: A Review of Its Use as Second-Line Treatment in Adults with Advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer of Adenocarcinoma Histology. Target Oncol 2015, 10, 303–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richeldi, L.; du Bois, R.M.; Raghu, G.; Azuma, A.; Brown, K.K.; Costabel, U.; Cottin, V.; Flaherty, K.R.; Hansell, D.M.; Inoue, Y.; et al. Efficacy and safety of nintedanib in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med 2014, 370, 2071–2082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dabholkar, S.; Gao, B.; Chuong, B. Nintedanib-A case of treating concurrent idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and non-small cell lung cancer. Respirol Case Rep 2022, 10, e0902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiratori, T.; Tanaka, H.; Tabe, C.; Tsuchiya, J.; Ishioka, Y.; Itoga, M.; Taima, K.; Takanashi, S.; Tasaka, S. Effect of nintedanib on non-small cell lung cancer in a patient with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: A case report and literature review. Thorac Cancer 2020, 11, 1720–1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukunaga, K.; Yokoe, S.; Kawashima, S.; Uchida, Y.; Nakagawa, H.; Nakano, Y. Nintedanib prevented fibrosis progression and lung cancer growth in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Respirol Case Rep 2018, 6, e00363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kai, Y.; Matsuda, M.; Fukuoka, A.; Hontsu, S.; Yamauchi, M.; Yoshikawa, M.; Muro, S. Remarkable response of non-small cell lung cancer to nintedanib treatment in a patient with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Thorac Cancer 2021, 12, 1457–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kramer, M.; Markart, P.; Drakopanagiotakis, F.; Mamazhakypov, A.; Schaefer, L.; Didiasova, M.; Wygrecka, M. Pirfenidone inhibits motility of NSCLC cells by interfering with the urokinase system. Cell Signal 2020, 65, 109432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Wang, Y.; Luo, D.; Cheng, Z.; Zeng, Q.; Wang, G.; Chen, M.; Zhang, S.; Luo, P. Pirfenidone inhibits TGF-beta1-induced metabolic reprogramming during epithelial-mesenchymal transition in non-small cell lung cancer. J Cell Mol Med 2024, 28, e18059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Branco, H.; Oliveira, J.; Antunes, C.; Santos, L.L.; Vasconcelos, M.H.; Xavier, C.P.R. Pirfenidone Sensitizes NCI-H460 Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Cells to Paclitaxel and to a Combination of Paclitaxel with Carboplatin. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurimoto, R.; Ebata, T.; Iwasawa, S.; Ishiwata, T.; Tada, Y.; Tatsumi, K.; Takiguchi, Y. Pirfenidone may revert the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in human lung adenocarcinoma. Oncol Lett 2017, 14, 944–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mediavilla-Varela, M.; Boateng, K.; Noyes, D.; Antonia, S.J. The anti-fibrotic agent pirfenidone synergizes with cisplatin in killing tumor cells and cancer-associated fibroblasts. BMC Cancer 2016, 16, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamamoto, Y.; Yano, Y.; Kuge, T.; Okabe, F.; Ishijima, M.; Uenami, T.; Kanazu, M.; Akazawa, Y.; Yamaguchi, T.; Mori, M. Safety and effectiveness of pirfenidone combined with carboplatin-based chemotherapy in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and non-small cell lung cancer: A retrospective cohort study. Thorac Cancer 2020, 11, 3317–3325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamada, S.; Ichiyasu, H.; Ikeda, T.; Inaba, M.; Kashiwabara, K.; Sadamatsu, T.; Sato, N.; Akaike, K.; Okabayashi, H.; Saruwatari, K.; et al. Protective effect of bevacizumab on chemotherapy-related acute exacerbation of interstitial lung disease in patients with advanced non-squamous non-small cell lung cancer. BMC Pulm Med 2019, 19, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Gong, X.; Hu, Y.; Yi, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Miao, L.; Zhou, Y. Anti-Angiogenic Drugs Inhibit Interstitial Lung Disease Progression in Patients With Advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Front Oncol 2022, 12, 873709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esfahani, K.; Meti, N.; Miller, W.H., Jr.; Hudson, M. Adverse events associated with immune checkpoint inhibitor treatment for cancer. CMAJ 2019, 191, E40–E46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haratani, K.; Hayashi, H.; Chiba, Y.; Kudo, K.; Yonesaka, K.; Kato, R.; Kaneda, H.; Hasegawa, Y.; Tanaka, K.; Takeda, M.; et al. Association of Immune-Related Adverse Events With Nivolumab Efficacy in Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. JAMA Oncol 2018, 4, 374–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shibaki, R.; Murakami, S.; Matsumoto, Y.; Goto, Y.; Kanda, S.; Horinouchi, H.; Fujiwara, Y.; Yamamoto, N.; Motoi, N.; Kusumoto, M.; et al. Tumor expression and usefulness as a biomarker of programmed death ligand 1 in advanced non-small cell lung cancer patients with preexisting interstitial lung disease. Med Oncol 2019, 36, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duitman, J.; van den Ende, T.; Spek, C.A. Immune Checkpoints as Promising Targets for the Treatment of Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis? J Clin Med 2019, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frank, A.J.; Dagogo-Jack, I.; Dobre, I.A.; Tait, S.; Schumacher, L.; Fintelmann, F.J.; Fingerman, L.M.; Keane, F.K.; Montesi, S.B. Management of Lung Cancer in the Patient with Interstitial Lung Disease. Oncologist 2023, 28, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kazerooni, E.A.; Martinez, F.J.; Flint, A.; Jamadar, D.A.; Gross, B.H.; Spizarny, D.L.; Cascade, P.N.; Whyte, R.I.; Lynch, J.P., 3rd; Toews, G. Thin-section CT obtained at 10-mm increments versus limited three-level thin-section CT for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: correlation with pathologic scoring. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1997, 169, 977–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamaguchi, T.; Shimizu, J.; Hasegawa, T.; Horio, Y.; Inaba, Y.; Yatabe, Y.; Hida, T. Pre-existing pulmonary fibrosis is a risk factor for anti-PD-1-related pneumonitis in patients with non-small cell lung cancer: A retrospective analysis. Lung Cancer 2018, 125, 212–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakanishi, Y.; Masuda, T.; Yamaguchi, K.; Sakamoto, S.; Horimasu, Y.; Nakashima, T.; Miyamoto, S.; Tsutani, Y.; Iwamoto, H.; Fujitaka, K.; et al. Pre-existing interstitial lung abnormalities are risk factors for immune checkpoint inhibitor-induced interstitial lung disease in non-small cell lung cancer. Respir Investig 2019, 57, 451–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishiyama, N.; Honda, T.; Sema, M.; Kawahara, T.; Jin, Y.; Natsume, I.; Chiaki, T.; Yamashita, T.; Tsukada, Y.; Taki, R.; et al. The utility of ground-glass attenuation score for anticancer treatment-related acute exacerbation of interstitial lung disease among lung cancer patients with interstitial lung disease. Int J Clin Oncol 2020, 25, 282–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isobe, K.; Nakamura, Y.; Sakamoto, S.; Tomii, K.; Takimoto, T.; Miyazaki, Y.; Matsumoto, M.; Sugino, K.; Ichikado, K.; Moriguchi, S.; et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitors in patients with lung cancer having chronic interstitial pneumonia. ERJ Open Res 2024, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Fan, Y.; Nie, L.; Wang, G.; Sun, K.; Cheng, Y. Clinical Outcomes of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Therapy in Patients With Advanced Non-small Cell Lung Cancer and Preexisting Interstitial Lung Diseases: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Chest 2022, 161, 1675–1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khunger, M.; Velcheti, V. A Case of a Patient with Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis with Lung Squamous Cell Carcinoma Treated with Nivolumab. J Thorac Oncol 2017, 12, e96–e97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ide, M.; Tanaka, K.; Sunami, S.; Asoh, T.; Maeyama, T.; Tsuruta, N.; Nakanishi, Y.; Okamoto, I. Durable response to nivolumab in a lung adenocarcinoma patient with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Thorac Cancer 2018, 9, 1519–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujimoto, D.; Yomota, M.; Sekine, A.; Morita, M.; Morimoto, T.; Hosomi, Y.; Ogura, T.; Tomioka, H.; Tomii, K. Nivolumab for advanced non-small cell lung cancer patients with mild idiopathic interstitial pneumonia: A multicenter, open-label single-arm phase II trial. Lung Cancer 2019, 134, 274–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tasaka, Y.; Honda, T.; Nishiyama, N.; Tsutsui, T.; Saito, H.; Watabe, H.; Shimaya, K.; Mochizuki, A.; Tsuyuki, S.; Kawahara, T.; et al. Non-inferior clinical outcomes of immune checkpoint inhibitors in non-small cell lung cancer patients with interstitial lung disease. Lung Cancer 2021, 155, 120–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kudoh, S.; Kato, H.; Nishiwaki, Y.; Fukuoka, M.; Nakata, K.; Ichinose, Y.; Tsuboi, M.; Yokota, S.; Nakagawa, K.; Suga, M.; et al. Interstitial lung disease in Japanese patients with lung cancer: a cohort and nested case-control study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2008, 177, 1348–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Assie, J.B.; Chouaid, C.; Nunes, H.; Reynaud, D.; Gaudin, A.F.; Grumberg, V.; Jolivel, R.; Jouaneton, B.; Cotte, F.E.; Duchemann, B. Outcome following nivolumab treatment in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer and comorbid interstitial lung disease in a real-world setting. Ther Adv Med Oncol 2023, 15, 17588359231152847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- JafariNezhad, A.; YektaKooshali, M.H. Lung cancer in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2018, 13, e0202360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashiwabara, K.; Semba, H.; Fujii, S.; Tsumura, S.; Aoki, R. Difference in benefit of chemotherapy between small cell lung cancer patients with interstitial pneumonia and patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Anticancer Res 2015, 35, 1065–1071. [Google Scholar]

- Togashi, Y.; Masago, K.; Handa, T.; Tanizawa, K.; Okuda, C.; Sakamori, Y.; Nagai, H.; Kim, Y.H.; Mishima, M. Prognostic significance of preexisting interstitial lung disease in Japanese patients with small-cell lung cancer. Clin Lung Cancer 2012, 13, 304–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanaji, N.; Shimizu, J.; Sakai, K.; Ueda, Y.; Miyawaki, H.; Watanabe, N.; Uemura, T.; Hida, T.; Inoue, T.; Watanabe, N.; et al. Clinical features of patients with small cell lung cancer and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis treated with chemotherapy or chemoradiotherapy. Ther Adv Respir Dis 2020, 14, 1753466620963866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koyama, N.; Iwai, Y.; Nagai, Y.; Aoshiba, K.; Nakamura, H. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in small cell lung cancer as a predictive factor for poor clinical outcome and risk of its exacerbation. PLoS One 2019, 14, e0221718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshida, T.; Yoh, K.; Goto, K.; Niho, S.; Umemura, S.; Ohmatsu, H.; Ohe, Y. Safety and efficacy of platinum agents plus etoposide for patients with small cell lung cancer with interstitial lung disease. Anticancer Res 2013, 33, 1175–1179. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nakao, S.; Yamaguchi, K.; Sakamoto, S.; Horimasu, Y.; Masuda, T.; Miyamoto, S.; Nakashima, T.; Iwamoto, H.; Fujitaka, K.; Hamada, H.; et al. Chemotherapy-associated Acute Exacerbation of Interstitial Lung Disease Shortens Survival Especially in Small Cell Lung Cancer. Anticancer Res 2019, 39, 5725–5731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikeda, S.; Ogura, T.; Kato, T.; Kenmotsu, H.; Agemi, Y.; Tokito, T.; Ito, K.; Isomoto, K.; Takiguchi, Y.; Yoneshima, Y.; et al. Nintedanib plus Chemotherapy for Small Cell Lung Cancer with Comorbid Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Modality | Diagnostic challenges |

|---|---|

| Pulmonary function tests (PFTs) | In CPFE, preserved lung volumes in patients may overestimate patients´ functional operability. DLCO is the most sensitive parameter |

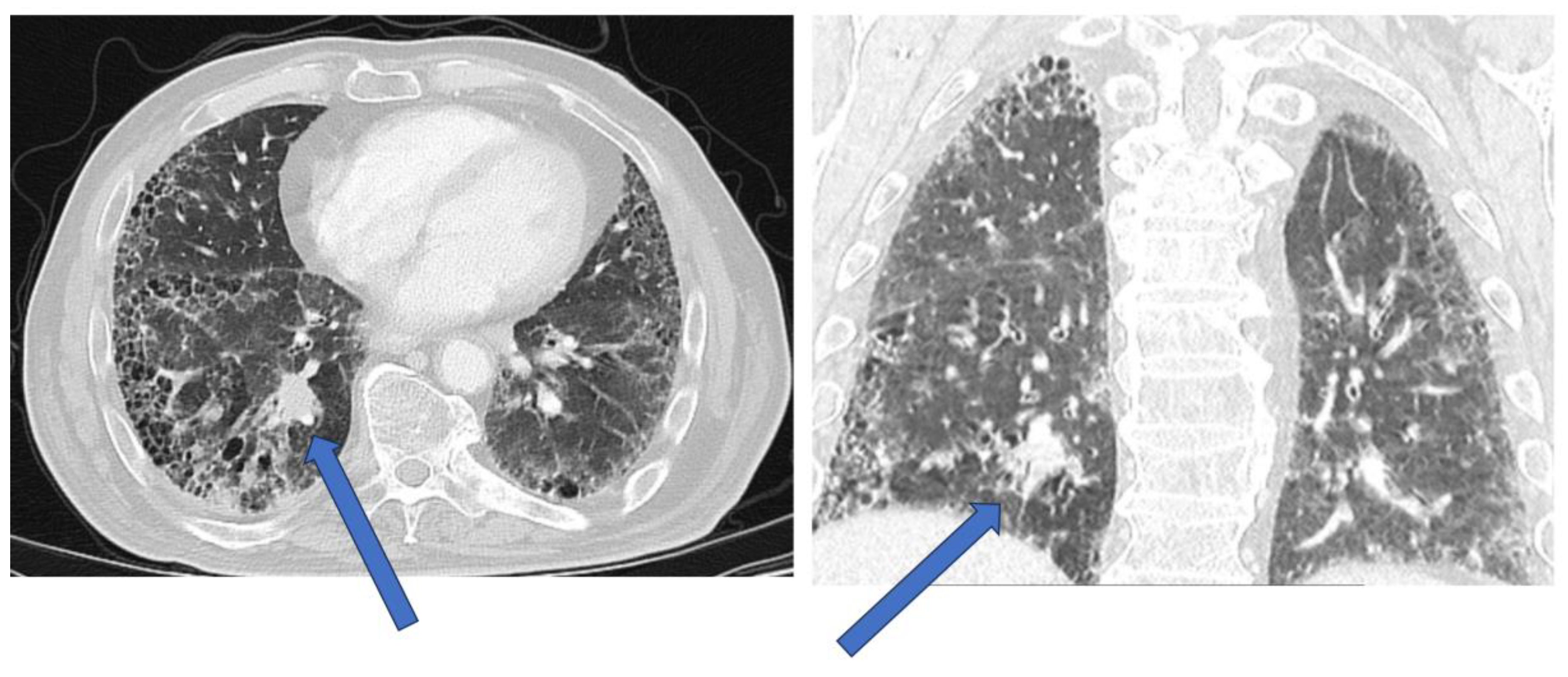

| HRCT | Tumors may be directly adjacent to fibrotic lesions, with underestimation of tumor size. Reduced sensitivity and specificity in evaluating mediastinal lymph nodes (reactive mediastinal lymph node enlargement may be seen in ILDs without lung cancer) |

| PET-scan | FDG-positive mediastinal lymph nodes may be reactive and not due to lung cancer infiltration |

| CT-guided biopsy | Motion artifacts and biopsy of fibrotic lesions adjacent to the tumor may give inconclusive results. Pneumothorax may be more difficult to treat. |

| Bronchoscopy with biopsy | Small risk of acute exacerbation of ILD (AE-ILD). Tumor identification with radial EBUS or navigational bronchoscopy in fibrotic milieu may be more challenging, compared to patients without ILDs |

| Surgical biopsy | Increased risk of AE-ILD |

| Stage of NSCLC | Treatment Options for NSCLC with ILD |

|---|---|

| Stage I | - Surgical resection (Lobectomy or segmentectomy): for patients with stable and well-controlled ILD, with mild to moderately-impaired lung function- Stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT): alternative to surgery for patients who are not surgical candidates due to their ILD, due to poor lung function or comorbidities. Option in a minority of very carefully selected patients due to the possible detrimental risk of pneumonitis. - Percutaneous image-guided ablation to be considered in patients with poor lung function and small tumors |

| Stage II | - Surgical resection: for patients with stable and well-controlled ILD, with mild to medium-impaired lung function- SBRT: For patients who are not suitable for surgery due to ILD, SBRT may be considered. Option in a minority of very carefully selected patients due to the possible detrimental risk of pneumonitis. |

| Stage III | -Radiochemotherapy: standard of treatment for locally advanced NSCLC. Decision to proceed in patients with ILD to be taken in oncology board, considering the potential risk of AE-ILD. Sequential, instead of concomitant therapy may be associated with reduced risk of pulmonary toxicity. Radiation therapy is an option in a minority of very carefully selected patients due to the possible detrimental risk of pneumonitis.- Immunotherapy: may be considered in patients with stable ILD and mild to moderately-impaired lung function, as part of the treatment regimen. |

| Stage IV | - Systemic therapy: chemotherapy, targeted therapy, immunotherapy, or a combination of the above depending on the patient's performance status, ILD status and comorbidities.- Palliative care: in advanced stages of NSCLC or end-stage ILD |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).