1. Introduction

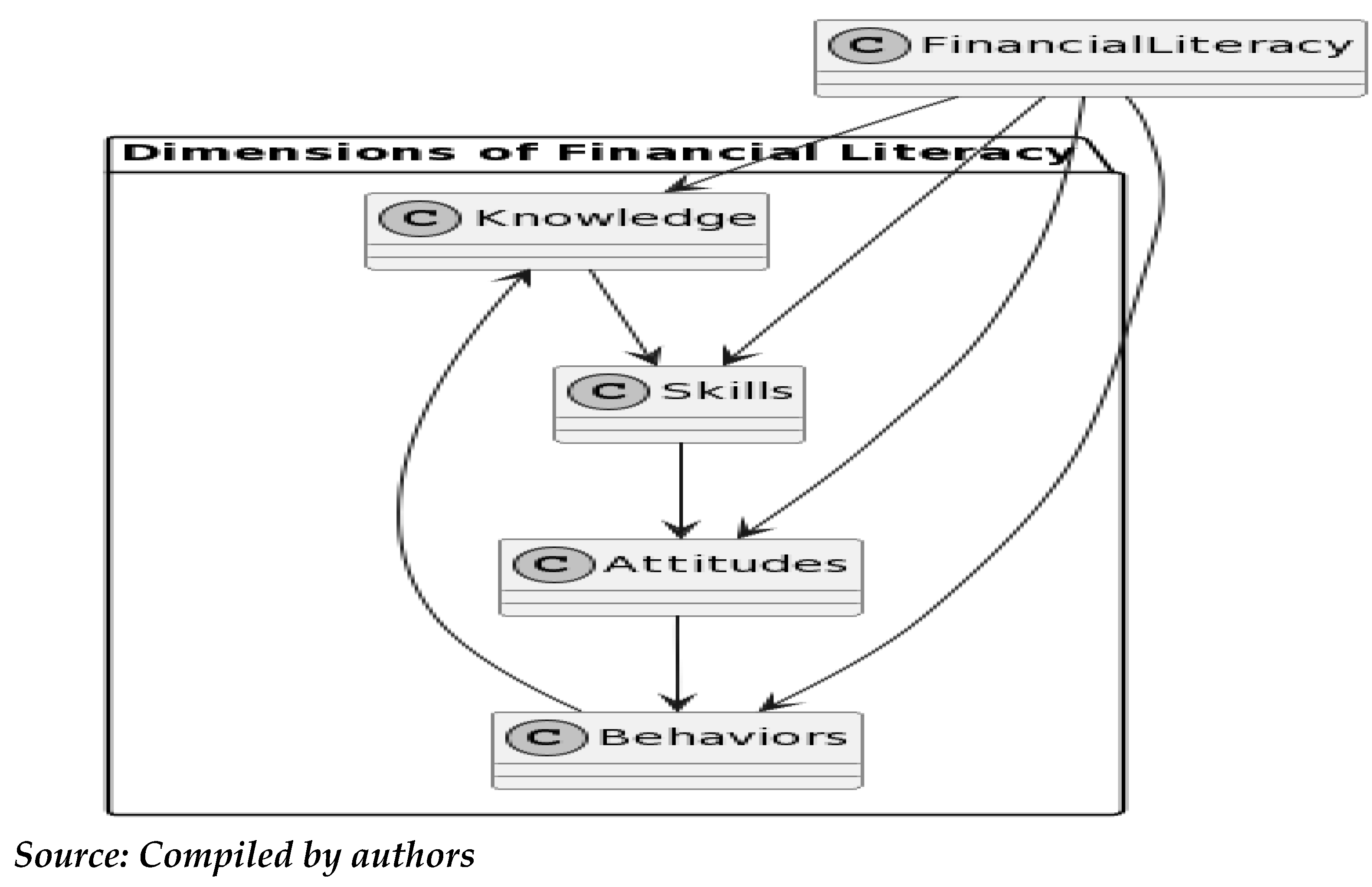

Financial literacy is crucial in today’s dynamic world which is characterized by the digitization of financial spheres, evolving retirement planning, easy access to credit, increasing life length, and the effects of the financial crisis in the long run. Financial literacy is vital for empowering people and maintaining their financial security in the modern, integrated, and complicated global economy. Consumers are anticipated to become more attentive to saving and investment decisions as their financial literacy increases (Lusardi and Mitchell, 2014). Understanding the amount of existing research on financial literacy is crucial as societies cope with rising financial complexity and the necessity of individual financial decision-making. It allows them to make money-related decisions wisely, secured against financial exploitation. Researchers from various disciplines have interpreted and assessed financial literacy during the past few decades (Braunstein and Welch, 2002). Financial skills, knowledge, motivation, and confidence are needed to make sound financial decisions in different circumstances and improvement of financial outcomes at both individual as well as societal levels is included in the idea of financial literacy. “A combination of awareness, knowledge, skill, attitude, and behavior necessary to make sound financial decisions and ultimately achieve individual financial well-being” (OECD/INFE, 2013).

Figure 1.

Dimension of Financial Literacy.

Figure 1.

Dimension of Financial Literacy.

Several Studies in this area are devoted to assessing the levels of financial literacy, identifying determinants that impact financial literacy, and evaluating financial education initiatives. Theories of behavior such as the theory of planned behavior, the theory of consumer socialization, and social learning theories are used to investigate the behavioral component of financial literacy. Financial capability, education, awareness, and other ideas are all related to financial literacy. Basic financial knowledge alone is worthless unless it is demonstrated by one's behavior with money (Atkinson and Messy, 2012). Although various literature reviews have examined particular facets of financial literacy, a thorough and all-encompassing analysis of this area is still required. This systematic literature review bridges this gap and provides a roadmap for future research. This systematic literature review draws upon a rich collection of literature, encompassing a wide range of research studies, reports, and scholarly articles. A meticulous examination of 3182 papers spanning from 1990 to 2023 provides a robust foundation for this review. The analysis offers quantitative evidence to support the qualitative synthesis of the literature. By examining the methodologies employed in previous studies, including behavioral economics, econometric analysis, and experimental approaches, this review provides a comprehensive understanding of the research landscape in financial literacy.

Financial well-being is the ability to achieve both current and future financial security and the capacity to make decisions that increase life satisfaction. Financial literacy is the capacity to manage financial resources efficiently for long-term financial well-being. Increasing financial literacy is anticipated to result in better investing and saving choices as well as improved financial decision-making abilities. The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) emphasizes the transformative potential of financial literacy, highlighting its role in promoting financial well-being and enabling individuals to navigate complex financial systems.

“We recognize the need for women and youth to gain access to financial services and financial education, ask the GPFI, the OECD/INFE, and the World Bank to identify barriers they may face and call for a progress report to be delivered by the next Summit” - G20 Leaders Declaration, June 2012.

Financial literacy has gained significant attention over the past decade, particularly in the aftermath of the global financial crisis of 2008. The crisis highlighted the importance of financial knowledge and skills, as individuals were found to have taken on financial products and risks without fully understanding them. Statistical data extracted from the published papers between 1990 and 2023 contribute to a comparative analysis of financial literacy across different countries, regions, and population groups. These data illuminate crucial aspects such as financial literacy levels among diverse demographics, the impact of interventions on knowledge and behavior, and the socioeconomic disparities in financial literacy outcomes. By incorporating these statistical insights, the review enriches understanding financial literacy dynamics.

This systematic literature review of financial literacy serves as a valuable resource for researchers, policymakers, and practitioners in their efforts to promote financial well-being and empower individuals through enhanced financial literacy. By synthesizing the insights and perspectives of various authors, institutions, and international bodies, this review sheds light on the importance of financial literacy in today's economic landscape and underscores its transformative potential for individuals, communities, and societies.

1.1. Objectives and Research Questions of the Study

The key objective of this study is to articulate the current state of scholarly research on financial literacy, with the subsequent questions illuminating the scope of the study:

RQ1: What are the current trends in the dissemination of financial literacy in terms of characteristics of time, academic fields, writers, connected nations and institutions, and research methodologies?

RQ2: Which scholarly endeavors and areas of investigation are most influential and prominent in this particular field of knowledge?

RQ3: What is the conceptual foundation of financial literacy research, how has it evolved through time, and what are the most recent research trends in this area?

RQ4: What are the shortfalls and problems that need further research in the future?

2. Research Approach

2.1. Database, Keywords, and Inclusion Criteria

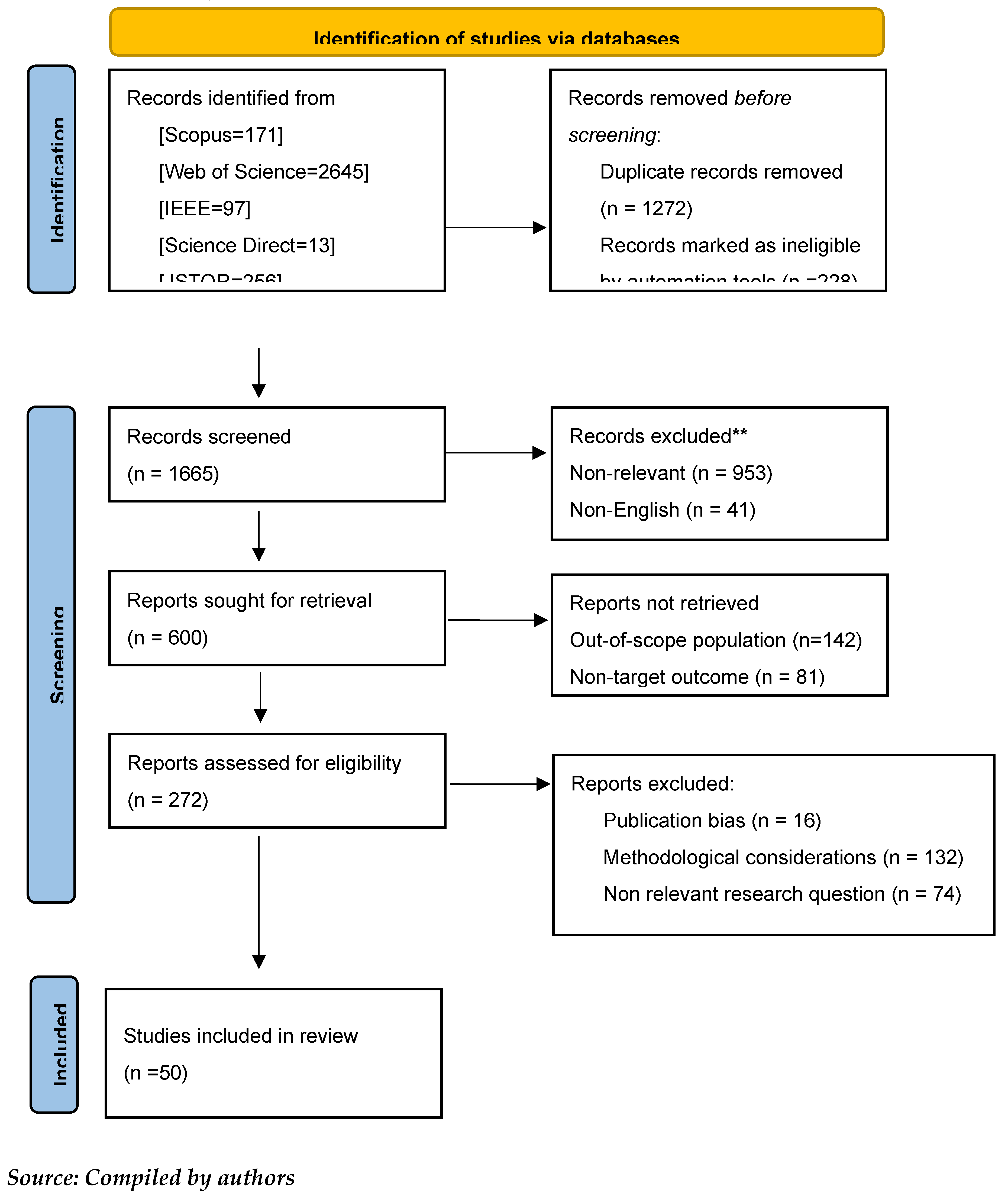

For the purpose of this systematic literature review, the authors employed the

PRISMA technique (Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses). For English-language publications published between

1990 and 2023, the full-text archives of five different publication databases,

Scopus (http://www.scopus.com/), Web of Science (http://isiwebofknowledge.com), IEEE (https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/), Science Direct (https://www.sciencedirect.com/) and JSTOR (https://www.jstor.org/) were searched. For search queries three main keywords were used “financial literacy”, “financial education” and “financial knowledge” and combined with the publications using other keywords such as “financial attitude”, “financial behavior”, “financial inclusion”, “gender disparity” and “financial planning”. It generated a sum of 3182 items including, 171 on Scopus, 2645 on Web of Science, 97 on IEEE, 13 on Science Direct, and 256 on JSTOR comprising journal articles, conference papers, research reports, etc. published between 1990 and 2023 according to queries made on

June 2, 2023. As represented in

Figure 2, the PRISMA flow chart had been used at various stages for the selection of research articles. In the first stage, duplicate articles (n=1272) were removed and only published articles were taken into account between 1990 and 2000. After eliminating articles at different stages due to different reasons only full-text articles were carried out for the study. The final stage of the systematic review procedure is the selection of articles in which research articles are assessed for inclusion based on all the inclusion criteria. Studies that meet the criteria listed in

Table 1 are either excluded or included.

Table 1.

Criteria for Inclusion and Exclusion.

Table 1.

Criteria for Inclusion and Exclusion.

| Parameters |

Inclusion Criteria |

Exclusion Criteria |

| Period |

Articles published between 1990-2023 were carried out. |

Articles published before 1990 |

| Population |

Male and Female |

Other genders |

| Standard of Comparison |

Demographic factors |

Non-Demographic factors |

| Study Design |

Original articles comprised experimental results |

Survey papers, case studies, other than English |

| Methodology |

Full text available |

Full text not available |

2.2. Quality Assessment

The research articles that comprise this review have been meticulously selected due to numerous restrictions on determining quality. The inclusion and exclusion criteria profoundly impact the relevancy of the study. In each study, gender is studied as an important determinant which is the significance of this study. As depicted in

Figure 2 of the PRISMA flow chart before the screening stage, 1517 items were removed due to duplicity, ineligibility, and some other reasons. In the second stage which is the stage of screening documents 1665 documents have been screened and then non-relevant (n=953), non-English (n=41),

and review articles (n=71) are excluded from the further stage for the development of the retrieval process. Reports (n=382) were not retrieved due to out-of-scope population (n=142), non-target outcome (n=81), and partial text accessibility (n=105). For the further development process of retrieval, 272 reports were assessed for eligibility and 222 were excluded for publication bias (n=16), methodological consideration (n=132), and non-relevant research questions (n=74). At the final stage which is the inclusion stage 50 published articles were included for systematic literature review.

3. Bibliometric Analysis

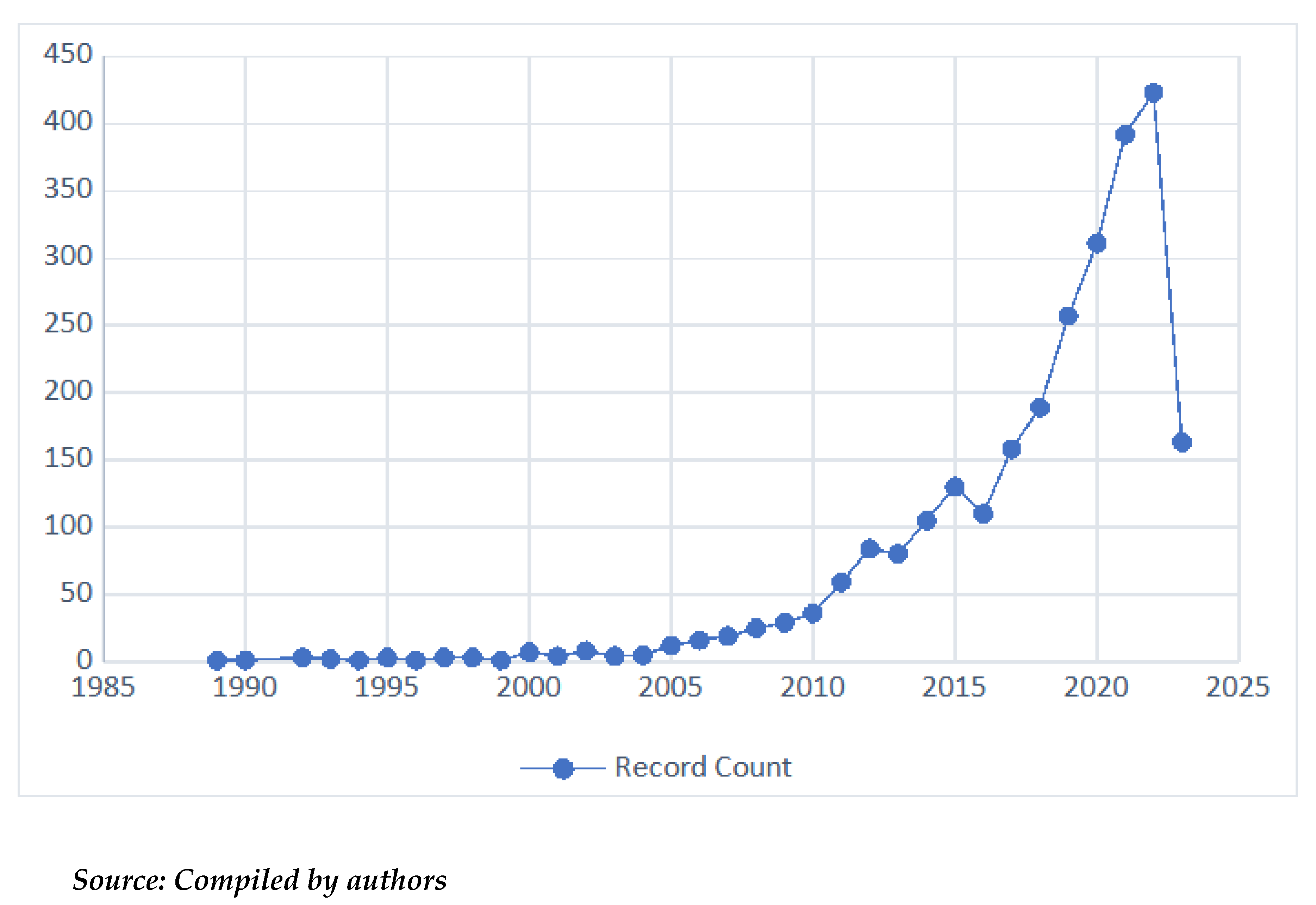

3.1. Trends of Publication in Time

Figure 3 depicts the growth of publishing articles annually between 1990 and 2023. It is clearly visible that before 2010 there were fewer publications on financial literacy, whereas after 2010 there was a sudden hike in the publication on the domain of financial literacy. One possible reason for this huge increment is the global financial crisis of 2008 which plays a significant role to motivate researchers to grasp financial literacy for research.

The macroeconomic upheaval provided a significant "teachable moment" for the general public, necessitating a policy emphasis on strong principles in financial education and consumer protection (OECD,2009). National financial education blueprints were launched in 2009 as a tactical measure to address the long-lasting effects of the turmoil in the economy. Additionally, in 2012, G20 leaders agreed with the OECD/INFE's exemplary guidelines for national financial education plans. The number of publications on this topic has increased by more than twice as much since then.

3.1. Eminent Authors and Their Notable Contributions

According to our dataset, a total of 1,896 academics from 621 different institutions in 89 different countries publish scholarly works on financial literacy. Based on the number of publications,

Table 3 compiles the most notable authors. With 166 published works, Mitchell, OS tops the list, followed by Boyle PA with 150 articles and Xiao JJ with 166. Notably, Annamaria Lusardi and Olivia S. Mitchell each obtain 12443 and 8771 citations, respectively, for receiving the most citations. These two authors have written extensively on a range of subjects, including financial literacy, financial education, and social security. They are widely regarded as an authority in the field.

The h-index is a statistic used to assess a researcher's contribution to the field of knowledge. Jorge E. Hirsch, a physicist, put out the idea in 2005. The h-index aims to assess the output and significance of a researcher's publications. The number of citations a researcher's publications have received determines how high their h-index is. A researcher has an h-index of h if they have h articles, each of which has been cited h times or more. To put it another way, it represents the highest number of papers with at least that many citations.

Bennett DA topped with 67 h index then Boyle PA and Lusardi A secured second and third rank in table with 41 and 40 h-index respectively.

Table 4 gives an overview of the number of citations for various papers on financial literacy. The amount of citations is an index of the respect and impact certain articles have attained in the realm of academia. Three articles stand out as being particularly significant among the highly referenced ones. The first one, "The Economic Importance of Financial Literacy: Theory and Evidence," has racked up a staggering 4,877 citations.

This article explores the theoretical underpinnings of financial literacy and offers empirical data underscoring its critical importance in making economic decisions. "An Analysis of Personal Financial Literacy Among College Students," the second most referenced article, earned up to 3,072 citations. This study emphasizes the importance of early financial education while assessing the level of financial literacy among college students. A further remarkable piece, "Planning and Financial Literacy: How Do Women Fare? " has received 2,017 citations. The financial literacy of women is investigated in this study, along with how it affects their financial planning and decision-making. The rest of the articles worked worthy on the topic of financial literacy with inclusion of gender gap, stock market, decision making, women empowerment etc.

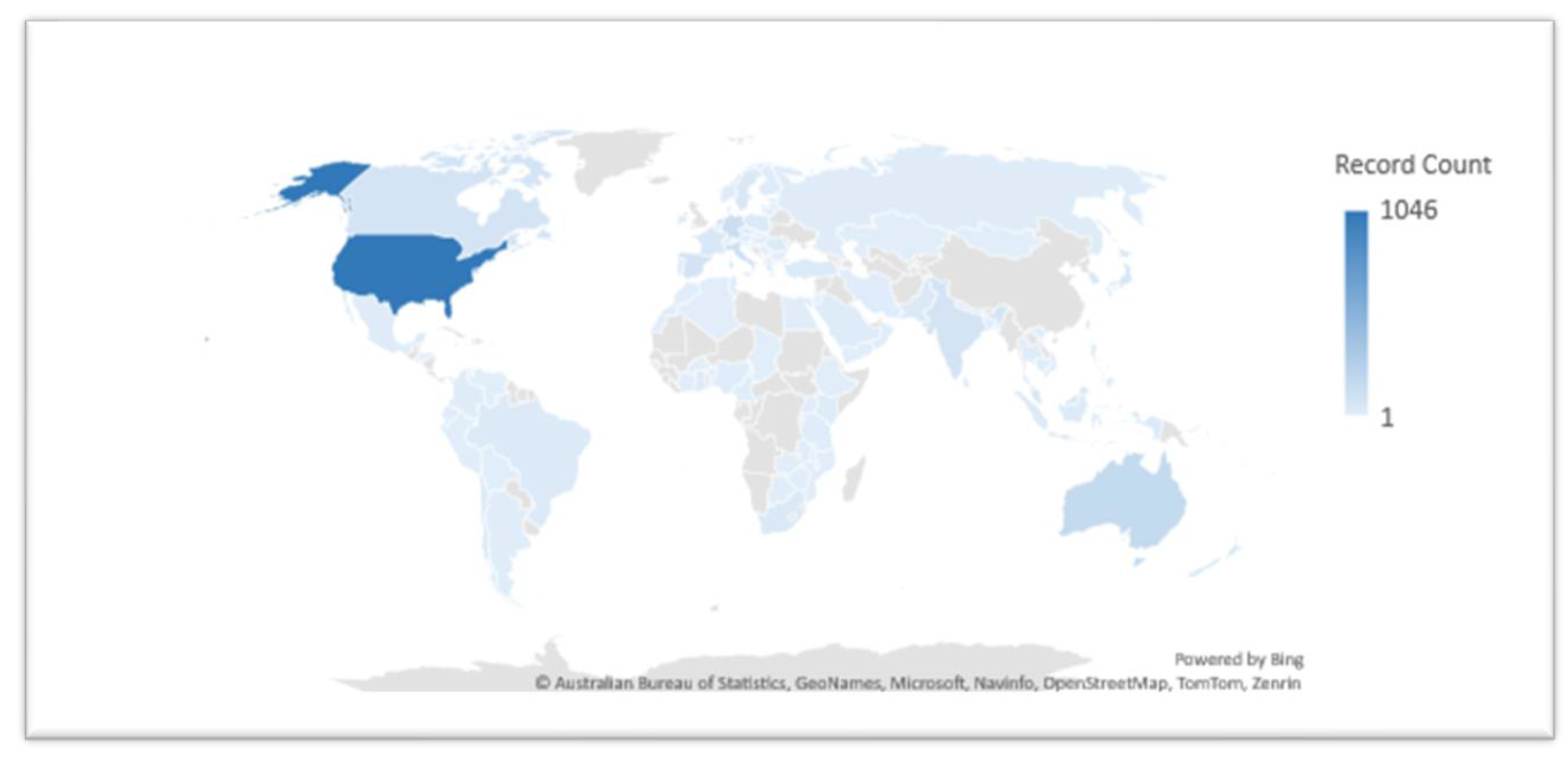

3.3. Leading Countries Publishing on Financial Literacy (1990–2023)

Source: Compiled by authors

The most prominent countries recognized by authors who contributed significant contributions to the field of financial literacy are listed in

Figure 4, The United States (1046 documents), the People’s Republic of China (298 documents), England (209 documents), Australia (175 documents), Germany (139 documents), and the Netherlands (117 documents) make up the top five nations in terms of article affiliation. These nations exhibit a keen interest in the discipline of personal finance since 2003 when the U.S. Government established its Financial Literacy and Education Commission and the United Kingdom launched its national strategy on financial capability (Financial Literacy and Education Commission, 2006). The American mortgage crisis serves as another evidence of the importance Americans are placing on financial literacy study.

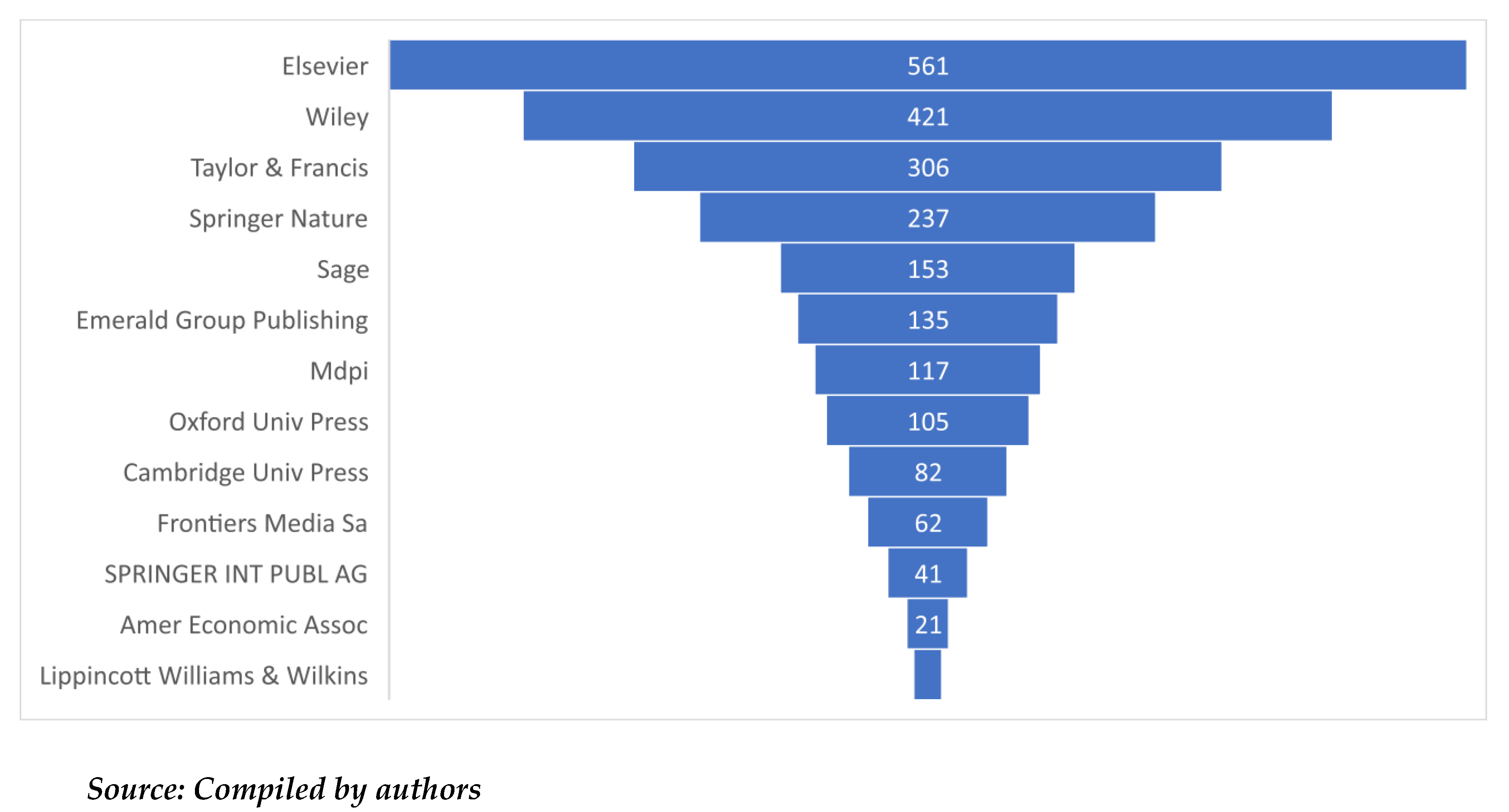

Figure 5 depicts a summary of the publishers in the field of financial literacy research along with their respective record counts. With 561 records, Elsevier stands out as the top publisher, demonstrating its dedication to spreading knowledge in the field of financial literacy. Elsevier established an excellent reputation for itself as a reliable source for researchers and academics in the subject by having a significant presence in the academic publishing industry. With 421 records, Wiley ranks in second place and indicates its commitment to distributing academic work on financial literacy. Personal finance, financial education, and financial planning are just a few of the themes covered in Wiley's publications, which add to the body of knowledge in this crucial field.

With 306 documents, Taylor and Francis also contributes significantly to the publication of studies on financial literacy. Taylor and Francis offers an avenue for scholars to share their knowledge and discoveries through its enormous library of journals and books, stimulating debates and improvements in the field of financial literacy research. Springer Nature, Sage, and Emerald Group Publishing are a few further notable publishers on the list of publishers. These publishers considerably contribute in the spread of research on financial literacy, with their respective record counts of 237, 153, and 135 publications. Their articles deliver valuable insights for researchers, practitioners, and policymakers on a variety of financial literacy topics, including financial decision-making, financial behaviour, and financial education. It is worthwhile to highlight that, whilst holding quite fewer records, publishers like MDPI, Oxford University Press, and Cambridge University Press also contribute to the body of information on financial literacy. These publishers emphasize on particular areas of financial literacy research and provide specialized content that enhances awareness of specific subjects. Finally, the figure illustrates the broad range of publications influential in disseminating financial literacy research. Their combined efforts help to expand research, disseminate best practices, and establish strategies to increase financial literacy around the world. These publishers are a reliable source of quality resources and up-to-date information on the most recent developments in the field of financial literacy research for researchers and stakeholders.

The distribution of financial literacy-related research findings throughout multiple domains is displayed in

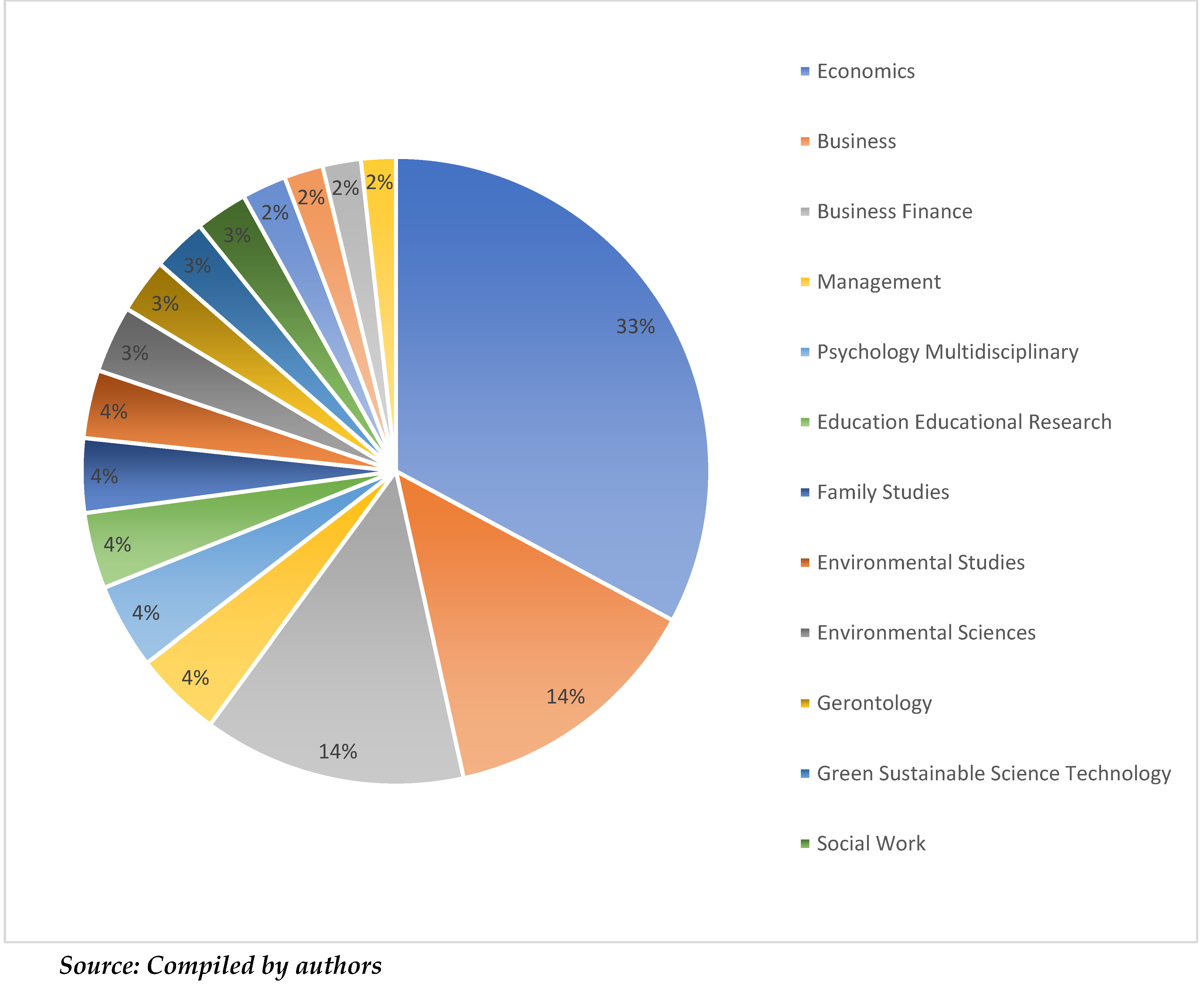

Figure 6 With 33percent (n=1,049) records, economics dominates and demonstrates its enormous contribution to the field. Trailing promptly with 14percent (n=436) records, business focused on the advantageous uses of financial literacy in organizational contexts. Business Finance, with 432 records, tackles the financial elements of firms, including risk management and decisions concerning investments. With 143 records, management investigates how financial literacy contributes to good leadership as well as choices. The disciplines of Psychology Multidisciplinary and Education Educational Research address the psychological and educational facets of financial literacy, with 140 and 125 records, respectively. The effect of financial literacy on families and environmental decision-making is highlighted by the disciplines of Family Studies, Environmental Studies, and Environmental Sciences, which have record counts between 110 and 122. This distribution illustrates the intricate nature of financial literacy and the demand for cross-disciplinary cooperation. Researchers can contribute to a thorough understanding of the topic and create effective approaches for increasing financial well-being by examining financial literacy from a variety of disciplinary perspectives.

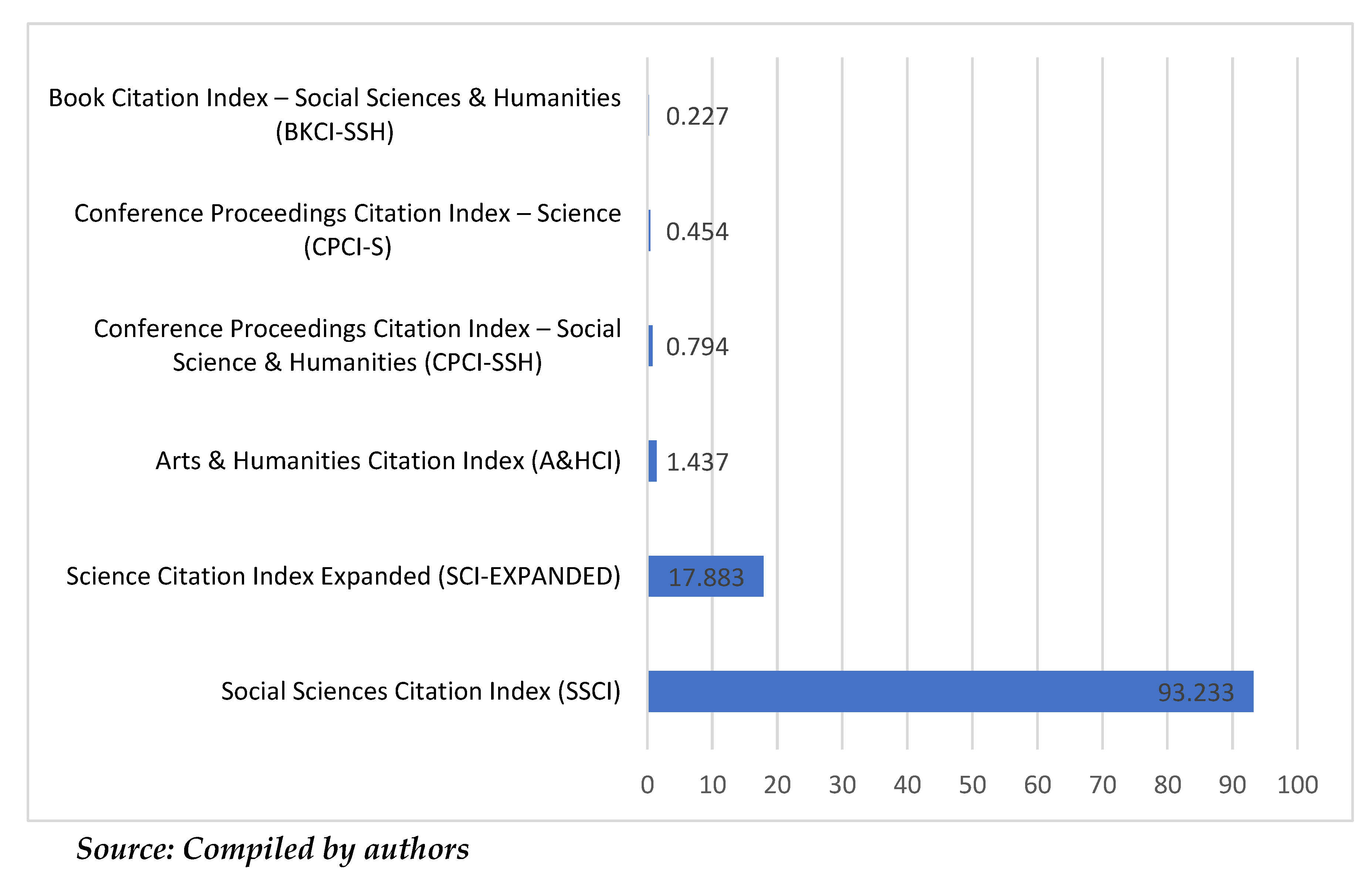

Figure 7 provides an overall understanding regarding how financial literacy research papers are organised all through distinct Web of Science indexes. The Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI) contains the majority of the papers or 93.233percent of the total. considering the interdisciplinary character of financial literacy research and its examination of behavioral and economic factors, this indicator spans a wide range of social science disciplines. 17.883percent of the publications are from the Science Citation Index Expanded (SCI-EXPANDED), which focuses on scientific and technological research in the area. 1.437percent of the papers are included in the Arts and Humanities Citation Index (AandHCI), highlighting the interdisciplinary approaches to financial literacy.

Research presented at conferences is included in the Conference Proceedings Citation Index - Social Science and Humanities (CPCI-SSH) and Conference Proceedings Citation Index - Science (CPCI-S), which account for 0.794percent and 0.454percent of the publications, respectively. Last but not least, 0.227percent of articles are included in the Book Citation Index - Social Sciences and Humanities (BKCI-SSH), demonstrating the significance of academic literature in furthering our understanding of financial literacy. Overall, the distribution across these indices illustrates the interdisciplinary character of financial literacy research and the collaborative efforts of academics from other disciplines to advance our understanding of this crucial topic.

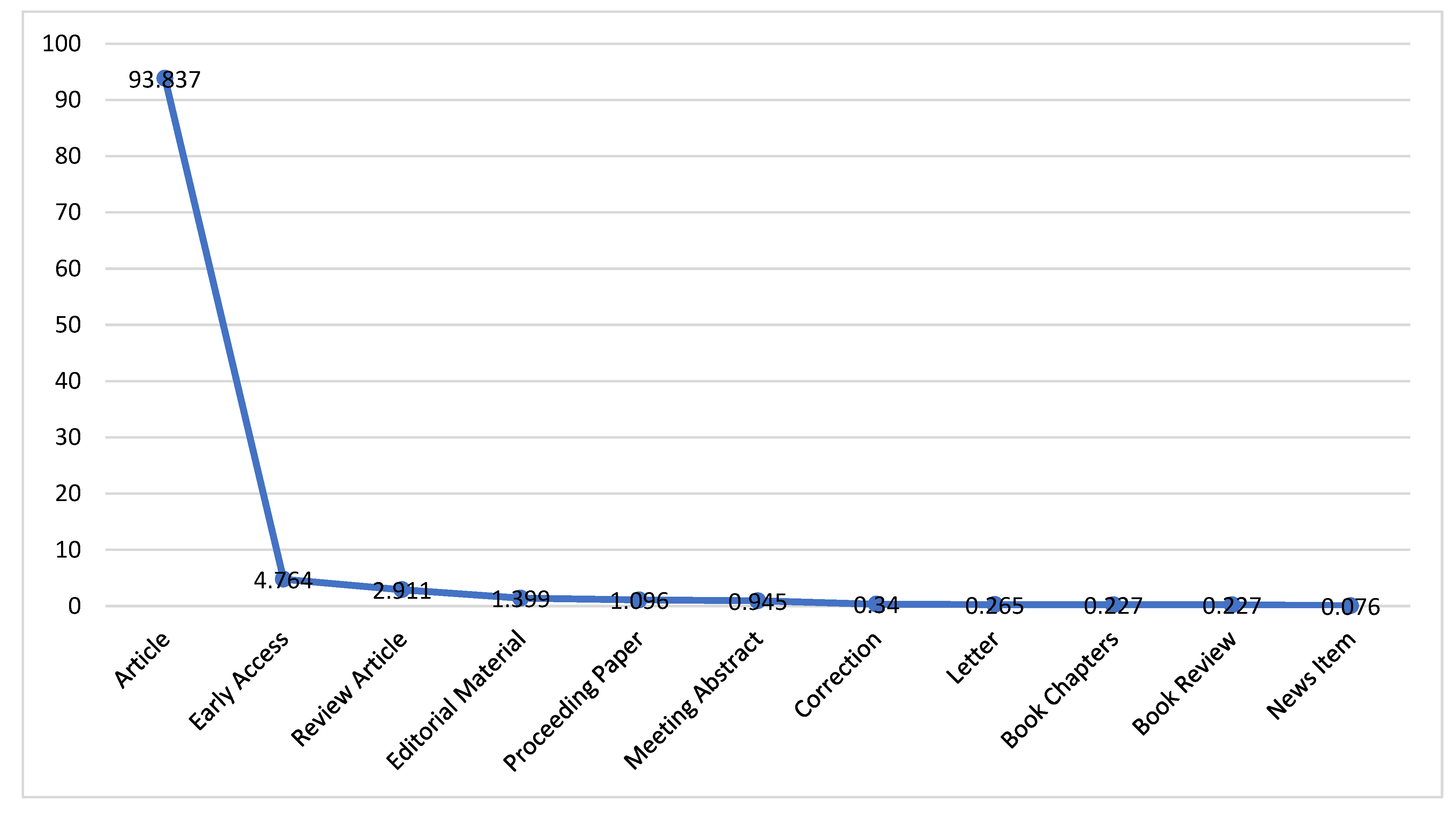

The distribution of document types among the 3,182 publications on financial literacy is shown in the

Figure 8. A whopping 93.837 percent of publications take the form of articles. These articles offer in-depth analysis and insights on various facets of financial literacy and are the results of original research investigations. Early Access publications make up 4.764percent of the total, showing that research is available even before it is formally published. 2.911percent of publications are review articles, which provide in-depth reviews and analyses of the body of knowledge in the topic. 1.399percent of the resources are editorials, which are articles published by specialists to offer analysis and comments on financial literacy-related topics. Research that was presented at conferences or symposiums is represented in proceeding papers (1.096percent). Meeting abstracts (0.945percent) offer succinct summaries of research reports made at scholarly conferences. Corrections, letters, book chapters, book reviews, and news articles are other documents kinds that make up a smaller portion of the overall publications. The variety of document types shows the range of contributions and formats used to communicate and promote research on financial literacy, enabling a thorough grasp of this crucial area.

Table 5 provides a summary of various research investigations in the social sciences and economics that were carried out by various writers. Each row represents a different study, and it includes information about its authors, publisher, data source, and sample size. For instance, Chen and Garand (2018) used the 2012 National Financial Capability Studies dataset with a sample size of 24,209 people for research that was published in the Social Science Quarterly. Using CFCS data and a sample size of 22,204, Fonseca and Lord (2020) published their analysis in the Review of Public Economics. Other studies investigated subjects including financial literacy, household dynamics, and public economics using various data sources, including surveys, microdata, or particular panel studies. The table gives a brief overview of the authorship, publications, data sources, and sample sizes of these studies, showcasing the diversity of research in this domain.

4.1. Determinants of Financial Literacy

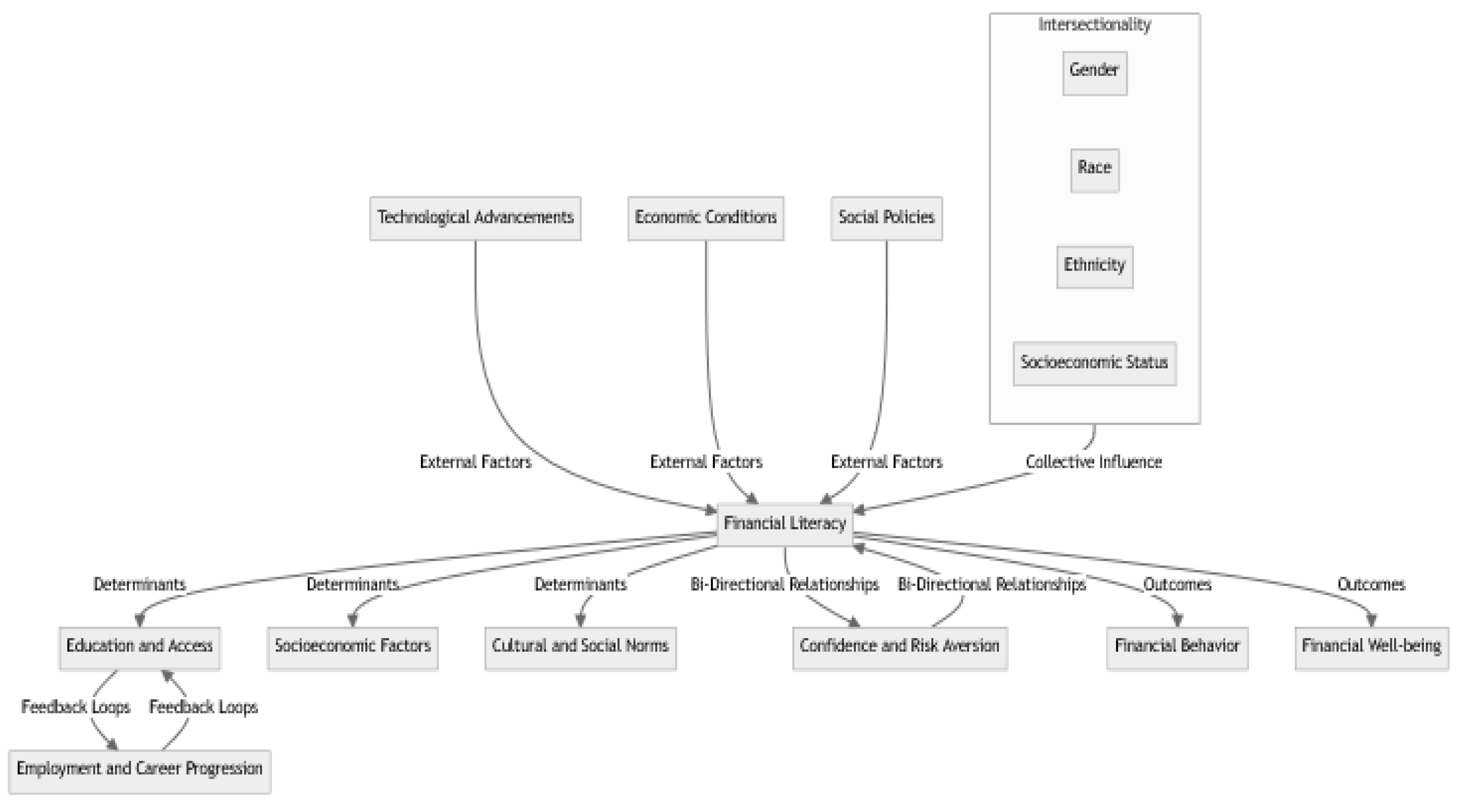

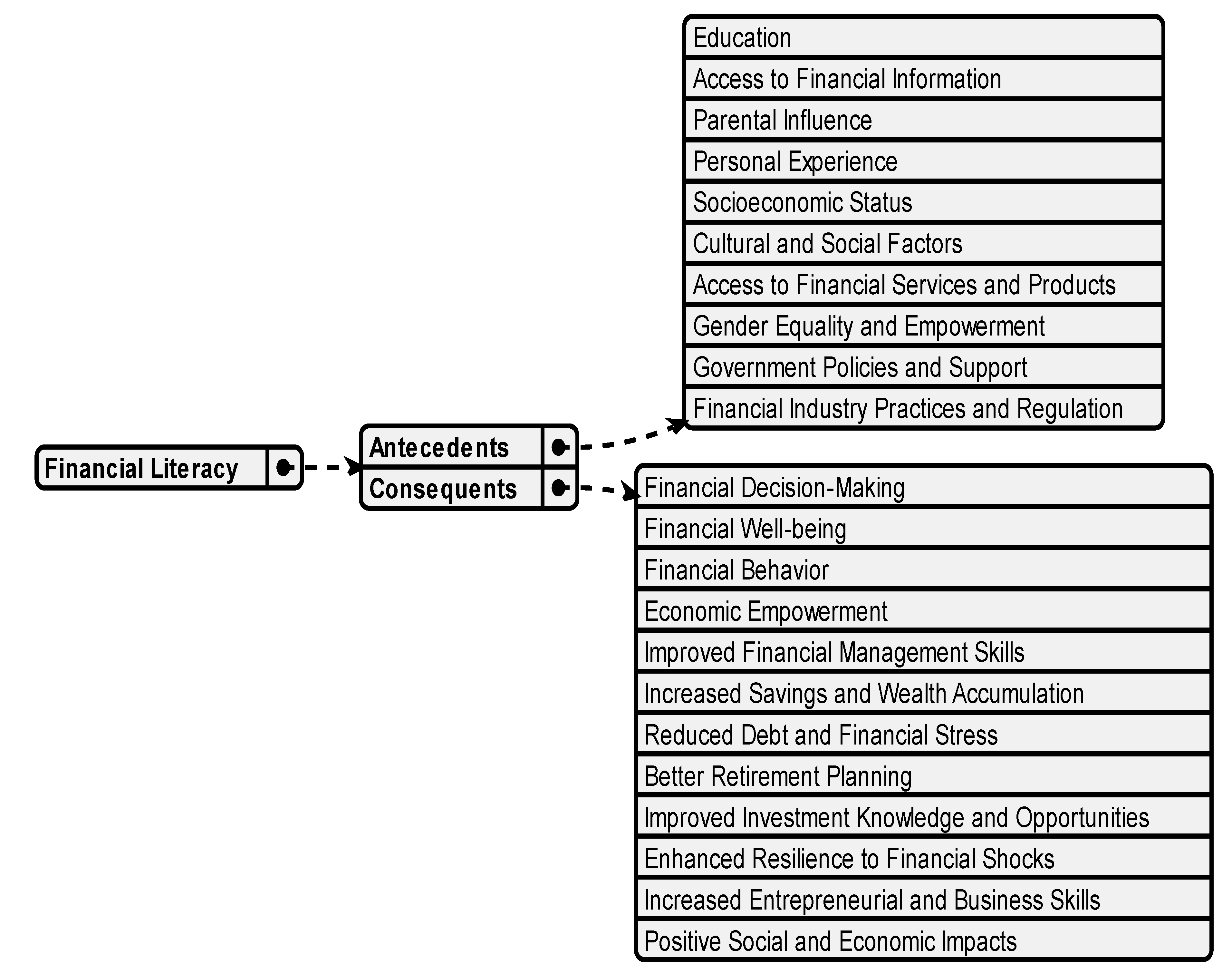

The term "determinants of financial literacy" refers to a wide range of elements that affect an individual's level of financial understanding and knowledge. External factors including economic conditions, social regulations, and technological improvements all have a huge impact.

Figure 9 depicts the financial literacy paradigm. Digital platforms have made financial information more accessible because of technological improvements, yet economic situations can affect people's financial resources and educational opportunities. Financial literacy levels can also be influenced by social policies, such as consumer protection laws and programs for financial education.

Financial literacy is influenced by gender, race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic level taken collectively. There are gender discrepancies, and women frequently face obstacles to obtaining education, resources, and opportunities. Financial literacy levels are frequently influenced by societal expectations and cultural norms. Socioeconomic variables, having access to a good education, and structural barriers can all contribute to racial and ethnic differences. Financial literacy is also influenced by socioeconomic circumstances, including income, wealth, and education. Greater access to resources and opportunities for financial education and awareness has been linked to higher socioeconomic levels.

The key drivers of financial literacy are education and access to financial information. Financial literacy is included into curricula in formal educational institutions, providing people with the information and abilities they need. Reliable and thorough financial tools, resources, and information are essential for enhancing financial literacy. Enhancing financial knowledge and decision-making skills is made easier by banking services, financial consultants, and educational resources. Income, wealth, and work position are socioeconomic characteristics that have a big impact on financial literacy. Greater possibilities for gaining financial knowledge and abilities are offered by higher wages and wealth. Financial behaviours and attitudes are also influenced by cultural and societal conventions surrounding money, saving, and spending. Individuals' financial decisions may be influenced by their attitudes towards debt, risk aversion, and financial priorities.

Financial literacy has reciprocal relationships with both confidence and risk aversion. An improvement in financial literacy encourages confidence in managing finances, and involvement in financial decision-making is fuelled by confidence. Risk perception and risk-taking propensity are influenced by financial literacy. Better financial literacy promotes risk-taking and responsible decision-making. Financial literacy is the basis for sound financial behavior and well-being. Financial habits including saving, investing, and borrowing are influenced by financial literacy. Enhanced financial knowledge promotes ethical spending habits and efficient money management. Additionally, financial literacy has a direct influence on financial well-being by promoting wise financial management, stable and secure financial decisions, and educated decision-making.

Employment and professional advancement engage in feedback loops with access and education. Financial literacy is improved by having more education and access to rewarding career possibilities. Increasing financial literacy also improves job and career chances. Higher education is made easier with access to financial resources, which helps people become more financially literate. In order to provide focused solutions, legislators, educators, and individuals must be aware of these determinants. Stakeholders may promote financial literacy and reduce inequities by addressing these variables. Through this concentrated effort, the financial environment is made more inclusive and egalitarian, enabling people to make wise financial decisions and attain financial well-being

4.2. Gender Disparity in Financial Literacy

A growing body of empirical research has investigated how gender inequality affects differences in financial behavior. This disparity can only be partially explained by differences in risk attitudes or task distribution (Lusardi and Mitchell, 2014). Recently, the gender gap in 2 countries was examined using OECD 2016 data. Findings showed that women, especially in industrialized nations, have a larger lack of financial literacy than men. According to Cupak, Fessler, Schneebaum, and Silgoner (2018), the societal norms surrounding women's participation in economic decision-making are the main cause of this discrepancy. The limited financial literacy of women is also attributed to stereotyped ideas (Driva, Lührmann, and Winter, 2016). This gendered disparity in financial literacy is further maintained through gender-biased financial parenting at home (Agnew et al., 2018). There is an urgent need for financial education specifically aimed at women, given that women are conscious of their lack of financial knowledge, as is demonstrated by their "do not know" responses to critical questions.

4.3. Probing the Depths of Financial Literacy

Numerous studies have looked at the ramifications of the gender difference in financial literacy. Married women have lower financial literacy than married males, according to Diáz and Jiménez (2021), although single women do not differ much from single men in this regard. In especially for homes with female beneficiaries, Koomson et al. (2021) underlined the beneficial effects of combined financial literacy and women's empowerment training on total household consumption expenditure. Financial literacy and risk tolerance are positively correlated with each other, as well as with investment choices, according to Naiwen et al. (2021). On the other hand, Younas and Rafay (2021) found that women business owners in Pakistan lack awareness of financial terms, financial access methods, and government programs. Women and men responded to basic financial questions differently, as indicated by the number of accurate answers and "Don't know/Refused" responses, according to Aristei and Gallo (2021).

A higher level of confidence in one's financial abilities and understanding enhances financial literacy (Fonseca and Lord, 2020). However, especially for women and those who are older, financial confidence does not always correlate with actual financial competence. According to Almenberg and Derber (2015), financial literacy is positively correlated with stock market involvement, and when financial literacy is taken into account, the gender effect is less pronounced. The gender disparity in financial literacy was underlined in the studies by Andrej Cupák et al. (2018) and Sergio Longobardi et al. (2018), with personal attributes only accounting for a portion of the gap. To close the gender gap, they emphasized the significance of tackling motivational and attitudinal variables, particularly among low-performing pupils. These studies show the importance of gender in financial literacy, how it affects different financial outcomes, and the necessity for specific interventions to increase women's financial literacy and empowerment.

5. Unravelling the Unexplored Dimensions of Financial Literacy

Future study and investigation into the subject of financial literacy has an enormous amount of scope. Assessing and filling in the gaps in financial literacy is crucial as the financial landscape changes and people's financial decision-making gets more complex. In order to fully understand how culture affects financial literacy, especially how culture affects gender, more study is required (Preston et al., 2023). The cultural context should be taken into account and gender equality should be promoted in interventions to improve women's financial literacy (Preston and Wright, 2023). Instead of just emphasizing women's financial literacy education, it is imperative to address cultural norms and beliefs (Thanki et al., 2022). Future studies can examine the moderating effect of gender on the link between financial risk tolerance and numerous parameters (Cupák et al., 2021; Okamoto and Komamura, 2021; Struckell et al., 2022). Further research can be done on the retirement planning and financial literacy of younger generations (Okamoto and Komamura, 2021), the success of women-specific financial education programs, and the contribution of social norms and institutional barriers to the gender gap in pension savings (Preston and Wright, 2023). Additionally, research is required on the variables affecting college students' financial knowledge (Yao et al., 2022) and the gender-related facets of financial self-efficacy and economic behaviour (Furrebé et al., 2022). Future research can examine the mechanisms by which confidence influences investment behaviour, assess interventions that aim to promote gender equality in investment behaviour (Cupák et al., 2021), and examine the long-term effects of gender differences in financial literacy (Furrebe et al., 2022). Additional factors influencing financial literacy, behaviours, and attitudes can be investigated (Struckell et al., 2022) and objective measurement methods for financial literacy and its effect on financial behaviour should be established in Japan (Okamoto and Komamura, 2021).

6. Epilogue Reflections

This in-depth study of financial literacy includes bibliometric analysis. It looks at a sample of 3182 papers from various databases, highlighting important works, knowledge gaps, and new trends. Major topics covered include gender disparities in financial literacy, financial literacy levels across demographic groups, the effects of financial literacy on behavior and planning, and the impact of financial education on day-to-day decisions. The analysis reveals differences in financial literacy among particular demographic categories, including adults, women, and those with lower incomes. It also emphasizes the beneficial relationship between money management, conduct, and financial literacy. The experimental group and program design both affect how well financial education programs work.

The review throws a lot of emphasis on the gender gap in financial literacy and looks at its definition, problems, and potential solutions. In today's global economy, it emphasizes the value of financial literacy in enabling informed decision-making, empowering people, and assuring their financial stability. Overall, this study offers insightful information for academics, professionals, and decision-makers, directing future research and assisting initiatives to improve financial literacy and its ramifications. The analysis emphasizes the value of financial literacy in navigating the complexity of the contemporary financial world and its ability to foster personal empowerment and financial well-being.

References

- Agnew, S., and Cameron-Agnew, T. (2015). The influence of consumer socialisation in the home on gender differences in financial literacy. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 39(6), 630–638. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcs.12179. [CrossRef]

- Agnew, S., and Harrison, N. (2015). Financial literacy and student attitudes to debt: A cross national study examining the influence of gender on personal finance concepts. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 25, 122–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2015.04.006. [CrossRef]

- Agnew, S., Maras, P., and Moon, A. (2018). Gender differences in financial socialization in the home—An exploratory study. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 42(3), 275–282. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcs.12415. [CrossRef]

- Aguiar-Díaz, I., and Zagalaz- Jiménez, J. R. (2022). Women and financial literacy in spain. Does marital status matter? Journal of Women and Aging, 34(6), 785–799. https://doi.org/10.1080/08952841.2021.1991194. [CrossRef]

- Al-Bahrani, A., Buser, W., and Patel, D. (2020). Early Causes of Financial Disquiet and the Gender Gap in Financial Literacy: Evidence from College Students in the Southeastern United States. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 41(3), 558–571. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-020-09670-3. [CrossRef]

- Almenberg, J., and Dreber, A. (2015). Gender, stock market participation and financial literacy. Economics Letters, 137, 140–142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econlet.2015.10.009. [CrossRef]

- Aristei, D., and Gallo, M. (2022). Assessing gender gaps in financial knowledge and self-confidence: Evidence from international data. Finance Research Letters, 46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.frl.2021.102200. [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, A. and F. Messy (2012), “Measuring Financial Literacy: Results of the OECD / International Network on Financial Education (INFE) Pilot Study”, OECD Working Papers on Finance, Insurance and Private Pensions, No. 15, OECD Publishing. http://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/finance-and-investment/measuring-financial-literacy_5k9csfs90fr4-en.

- Bannier, C. E., and Neubert, M. (2016). Gender differences in financial risk taking: The role of financial literacy and risk tolerance. Economics Letters, 145, 130–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econlet.2016.05.033. [CrossRef]

- Bannier, C. E., and Schwarz, M. (2018). Gender- and education-related effects of financial literacy and confidence on financial wealth. Journal of Economic Psychology, 67, 66–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joep.2018.05.005. [CrossRef]

- Białowolski, P., Cwynar, A., Cwynar, W., and Węziak-Białowolska, D. (2020). Consumer debt attitudes: The role of gender, debt knowledge and skills. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 44(3), 191–205. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcs.12558. [CrossRef]

- Chen, H., and Volpe, R. P. (1998). An Analysis of Personal Financial Literacy Among College Students. 7(2), 107–128.

- Chen, J., Jiang, J., and Liu, Y. jane. (2018). Financial literacy and gender difference in loan performance. Journal of Empirical Finance, 48, 307–320. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jempfin.2018.06.004. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z., and Garand, J. C. (2018). On the Gender Gap in Financial Knowledge: Decomposing the Effects of Don’t Know and Incorrect Responses*. Social Science Quarterly, 99(5), 1551–1571. https://doi.org/10.1111/ssqu.12520. [CrossRef]

- Cupák, A., Fessler, P., and Schneebaum, A. (2021). Gender differences in risky asset behavior: The importance of self-confidence and financial literacy. Finance Research Letters, 42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.frl.2020.101880. [CrossRef]

- Cupák, A., Fessler, P., Schneebaum, A., and Silgoner, M. (2018). Decomposing gender gaps in financial literacy: New international evidence. Economics Letters, 168, 102–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econlet.2018.04.004. [CrossRef]

- Do, C., and Paley, I. (2013). Does Gender Affect Mortgage Choice? Evidence from the US. Feminist Economics, 19(2), 33–68. https://doi.org/10.1080/13545701.2013.787163. [CrossRef]

- Driva, A., Lührmann, M., and Winter, J. (2016). Gender differences and stereotypes in financial literacy: Off to an early start. Economics Letters, 146, 143–146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econlet.2016.07.029. [CrossRef]

- Falahati, L., and Paim, L. H. (2011). Gender Differences in Financial Literacy among College Students. In Journal of American Science (Vol. 7, Issue 6). http://www.americanscience.orgeditor@americanscience.org1180http://www.americanscience.org.

- Farrar, S., Moizer, J., Lean, J., and Hyde, M. (2019). Gender, financial literacy, and preretirement planning in the UK. Journal of Women and Aging, 31(4), 319–339. https://doi.org/10.1080/08952841.2018.1510246. [CrossRef]

- Fernández-López, S., Vivel-Búa, M., Otero-González, L., and Durán-Santomil, P. (2015). Exploring The Gender Effect On Europeans’ Retirement Savings. Feminist Economics, 21(4), 118–150. https://doi.org/10.1080/13545701.2015.1005653. [CrossRef]

- Fletschner, D., and Mesbah, D. (2011). Gender disparity in access to information: Do spouses share what they know? World Development, 39(8), 1422–1433. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2010.12.014. [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, R., and Lord, S. (2020). Canadian Gender Gap in Financial Literacy: Confidence Matters. Hacienda Publica Espanola, 235(4), 153–182. https://doi.org/10.7866/HPE-RPE.20.4.7. [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, R., Mullen, K. J., Zamarro, G., and Zissimopoulos, J. (2012). What Explains the Gender Gap in Financial Literacy? The Role of Household Decision Making. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 46(1), 90–106. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6606.2011.01221.x. [CrossRef]

- Furrebøe, E. F., Nyhus, E. K., and Musau, A. (2023). Gender differences in recollections of economic socialization, financial self-efficacy, and financial literacy. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 57(1), 69–91. https://doi.org/10.1111/joca.12490. [CrossRef]

- Goyal, K., and Kumar, S. (2021). Financial literacy: A systematic review and bibliometric analysis. In International Journal of Consumer Studies, 45 (1), 80–105. Blackwell Publishing Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcs.12605. [CrossRef]

- Haque, A., and Zulfiqar, M. (2016). Women’s Economic Empowerment through Financial Literacy, Financial Attitude and Financial Wellbeing. In International Journal of Business and Social Science, 7,(3). www.ijbssnet.com.

- Hsu, Y. L., Chen, H. L., Huang, P. K., and Lin, W. Y. (2021). Does financial literacy mitigate gender differences in investment behavioral bias? Finance Research Letters, 41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.frl.2020.101789. [CrossRef]

- Koomson, I., Villano, R. A., and Hadley, D. (2020). Intensifying financial inclusion through the provision of financial literacy training: a gendered perspective. Applied Economics, 52(4), 375–387. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036846.2019.1645943. [CrossRef]

- Lind, T., Ahmed, A., Skagerlund, K., Strömbäck, C., Västfjäll, D., and Tinghög, G. (2020). Competence, Confidence, and Gender: The Role of Objective and Subjective Financial Knowledge in Household Finance. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 41(4), 626–638. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-020-09678-9. [CrossRef]

- Longobardi, S., Pagliuca, M. M., and Regoli, A. (2018). Can problem-solving attitudes explain the gender gap in financial literacy? Evidence from Italian students’ data. Quality and Quantity, 52(4), 1677–1705. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-017-0545-0. [CrossRef]

- Lusardi, A., and Mitchell, O. S. (2014). The economic importance of financial literacy: Theory and evidence. Journal of Economic Literature, 52(1), 5–44. https://doi.org/10.1257/jel.52.1.5. [CrossRef]

- Marinelli, N., Mazzoli, C., and Palmucci, F. (2017). How does gender really affect investment behavior? Economics Letters, 151, 58–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econlet.2016.12.006. [CrossRef]

- Migheli, M., and Coda Moscarola, F. (2017). Gender Differences in Financial Education: Evidence from Primary School. Economist (Netherlands), 165(3), 321–347. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10645-017-9300-0. [CrossRef]

- Miller, M., Reichelstein, J., Salas, C., and Zia, B. (2015). Can you help someone become financially capable? A meta-analysis of the literature. World Bank Research Observer, 30(2), 220–246. https://doi.org/10.1093/wbro/lkv009. [CrossRef]

- Moon, C.-S., Korea, S., Ohk, K., and Choi, C. (n.d.). Gender Differences in Financial Literacy among Chinese University Students and the Influential Factors*.

- Naiwen, L., Wenju, Z., Mohsin, M., Ur Rehman, M. Z., Naseem, S., and Afzal, A. (2021). The role of financial literacy and risk tolerance: An analysis of gender differences in the textile sector of Pakistan. Industria Textila, 72(3), 300–308. https://doi.org/10.35530/IT.072.03.202023. [CrossRef]

- Nitani, M., Riding, A., and Orser, B. (2020). Self-employment, gender, financial knowledge, and high-cost borrowing. Journal of Small Business Management, 58(4), 669–706. https://doi.org/10.1080/00472778.2019.1659685. [CrossRef]

- OECD (2009). Financial literacy and consumer protection: Overlooked aspects of the crisis. Paris, France: OECD Publishing.

- OECD/INFE (2013). Financial Literacy And Inclusion: Results Of OECD/INFE Survey Across Countries And By Gender. OECD Publishing.

- Okamoto, S., and Komamura, K. (2021). Age, gender, and financial literacy in Japan. PLoS ONE, 16(11 November 2021). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0259393. [CrossRef]

- Ooi, E. (2020). Give mind to the gap: Measuring gender differences in financial knowledge. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 54(3), 931–950. https://doi.org/10.1111/joca.12310. [CrossRef]

- Pahlevan Sharif, S., Ahadzadeh, A. S., and Turner, J. J. (2020). Gender Differences in Financial Literacy and Financial Behaviour Among Young Adults: The Role of Parents and Information Seeking. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 41(4), 672–690. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-020-09674-z. [CrossRef]

- Preston, A. C., and Wright, R. E. (2019). Understanding the Gender Gap in Financial Literacy: Evidence from Australia. Economic Record, 95(S1), 1–29. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-4932.12472. [CrossRef]

- Preston, A., Qiu, L., and Wright, R. E. (2023). Understanding the gender gap in financial literacy: The role of culture. Journal of Consumer Affairs. https://doi.org/10.1111/joca.12517. [CrossRef]

- Preston, A., and Wright, R. E. (2023). Gender, Financial Literacy and Pension Savings*. Economic Record, 99(324), 58–83. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-4932.12708. [CrossRef]

- Radhakrishnan, S. (2018). Of loans and livelihoods: Gendered “social work” in urban India. Economic Anthropology, 5(2), 235–246. https://doi.org/10.1002/sea2.12120. [CrossRef]

- Robson, J., and Peetz, J. (2020). Gender differences in financial knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors: Accounting for socioeconomic disparities and psychological traits. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 54(3), 813–835. https://doi.org/10.1111/joca.12304. [CrossRef]

- Struckell, E. M., Patel, P. C., Ojha, D., and Oghazi, P. (2022). Financial literacy and self employment – The moderating effect of gender and race. Journal of Business Research, 139, 639–653. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.10.003. [CrossRef]

- Thanki, H., Shah, S., Sapovadia, V., Oza, A. D., and Burduhos-Nergis, D. D. (2022). Role of Gender in Predicting Determinant of Financial Risk Tolerance. Sustainability (Switzerland), 14(17). https://doi.org/10.3390/su141710575. [CrossRef]

- Tinghög, G., Ahmed, A., Barrafrem, K., Lind, T., Skagerlund, K., and Västfjäll, D. (2021). Gender differences in financial literacy: The role of stereotype threat. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 192, 405–416. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2021.10.015. [CrossRef]

- Walczak, D., and Pienkowska-Kamieniecka, S. (2018). Gender differences in financial behaviours. Engineering Economics, 29(1), 123–132. https://doi.org/10.5755/j01.ee.29.1.16400. [CrossRef]

- Yao, M., Rehr, T. I., and Regan, E. P. (2022). Gender Differences in Financial Knowledge among College Students: Evidence from a Recent Multi-institutional Survey. Journal of Family and Economic Issues. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-022-09860-1. [CrossRef]

- Yu, K. M., Wu, A. M., Chan, W. S., and Chou, K. L. (2015). Gender Differences in Financial Literacy Among Hong Kong Workers. Educational Gerontology, 41(4), 315–326. https://doi.org/10.1080/03601277.2014.966548. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).