Pinna nobilis (Linnaeus, 1758), the pen shell, and the congeneric

P. rudis (Linnaeus, 1758), the spiny/rough fan mussel, are two molluscan species of the family Pinnidae that inhabit the Mediterranean Sea [

1]. A third species of this family,

Atrina fragilis (Pennant, 1777), is rarer in the Mediterranean, preferring detritic bottoms at depths up to 600 m [

2].

P. nobilis is endemic to the Mediterranean [

3] while

P. rudis has a subtropical affinity, and it is mainly present along the Atlantic African coasts [

4]. They are sibling species whose distribution in the Mediterranean partially overlaps [

5]; in fact, although the priority habitats are different, their bathymetric distribution is widely shared [

6]. In particular,

P. nobilis preferentially inhabits seagrass meadows, including dead matte of

Posidonia oceanica, macroalgal canopies, muddy and sandy bottoms and detritic patches in rocky bottoms, at depths up to 60 m [

3,

7];

P. rudis is thermophilic and colonizes gravel and rocky bottoms even though its presence has been reported also from

P. oceanica meadows [

8].

These species are both strictly protected by EC directives, national laws, and are listed in the Annex II of the Barcelona Convention as threatened or endangered. Since 2016,

P. nobilis is suffering the infection of different pathogens,

Haplosporidium pinnae among all, that have caused mass mortality events throughout the Mediterranean Sea [

9,

10] and now the status of the species, assessed by the red list of the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN), is: Critically Endangered [

11].

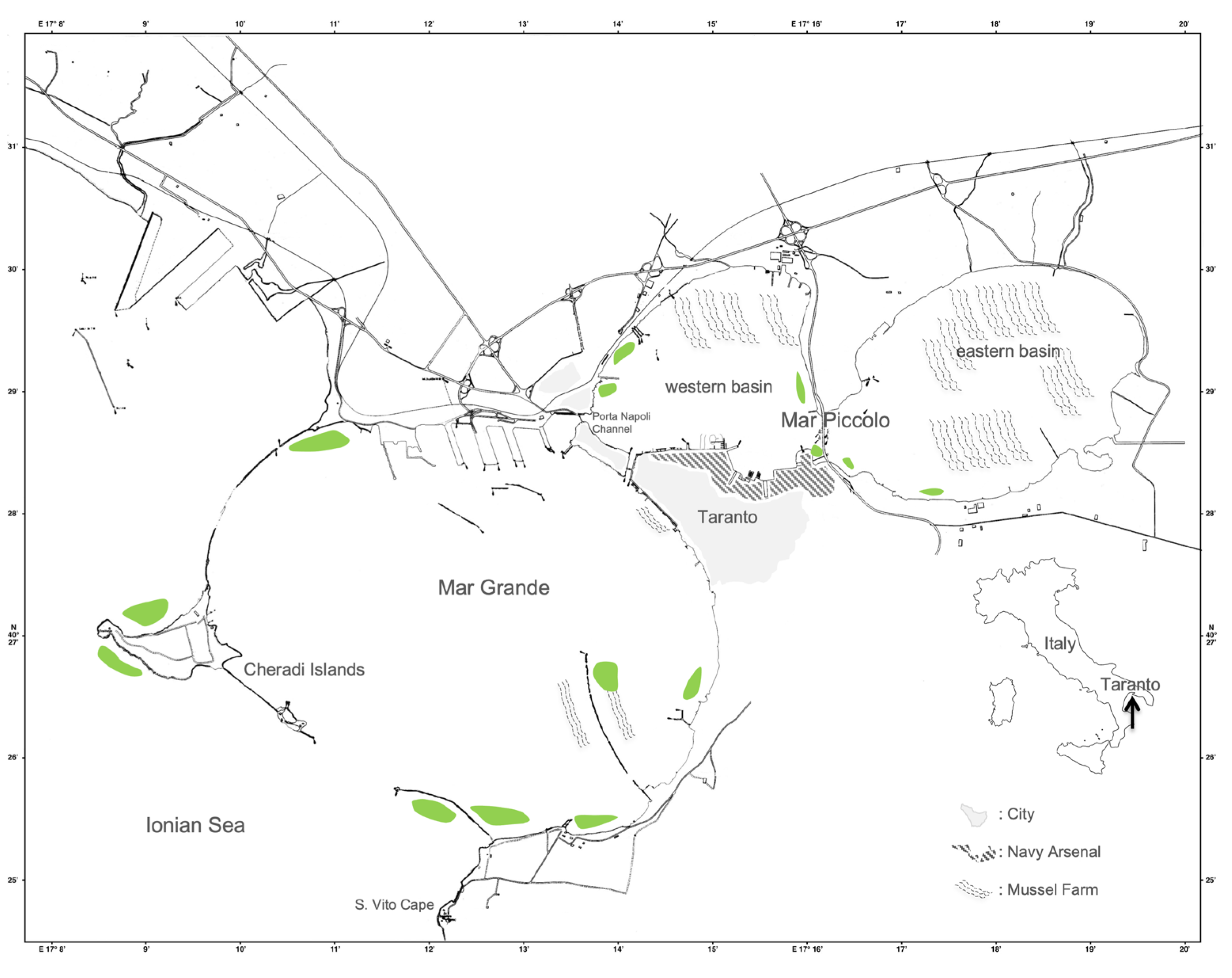

Along the coasts of Apulia, in Southern Italy,

P. nobilis was historically largely distributed. In the Taranto marine area [

12,

13], until 2018 this species was very abundant with more than 10,000 individuals present in the two basins of the Mar Piccolo and in the Mar Grande (

Figure 1). In 2016 an important translocation activity was carried out to move nearly 2,000 specimens from an area outside the Mar Grande, where the Port Authority of Taranto realized a “sediment tank” deputed to host sediments dredged in an area of the port. The entire population was transferred into an area of the Mar Grande where a numerous “natural” population was already present, settled over an extensive dead matte of

P. oceanica [

14] (

Figure 2).

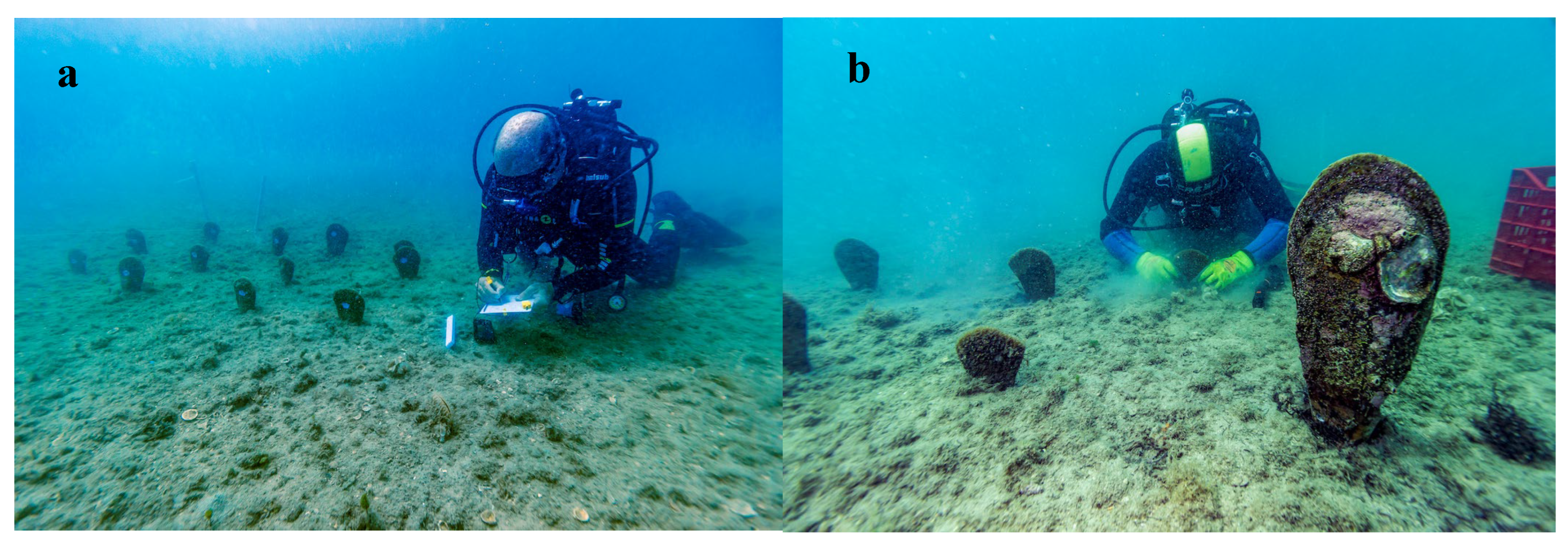

Starting from the spring of 2018, in a very short time, thousands of specimens died both in the Mar Piccolo and Mar Grande and in 2019 less than 10 living specimens were observed during the monitoring activities carried out by the SCUBA divers of the CNR IRSA of Taranto (

Figure 3). The cause of this mass mortality was ascribed to

Haplosporidium pinnae [

15,

16] like already reported for the same events in the Western Mediterranean [

17].

A very similar situation we found at the Archipelago of Tremiti Islands, in the Southern Adriatic Sea, where the local

P. nobilis population was reported in a good health until the summer of 2019 [

18]. Notwithstanding, in September 2019, during a survey organized with the cooperation of the Coast Guard Maritime Directorate of Pescara, a diffuse mortality was observed with very few living individuals at sites with depths over 20 meters and water temperature of 13-15°C (

Figure 4). The mantle biopsies of some moribund specimens revealed the presence of

Mycobacterium sp. and

Haplosporidium sp. [

19].

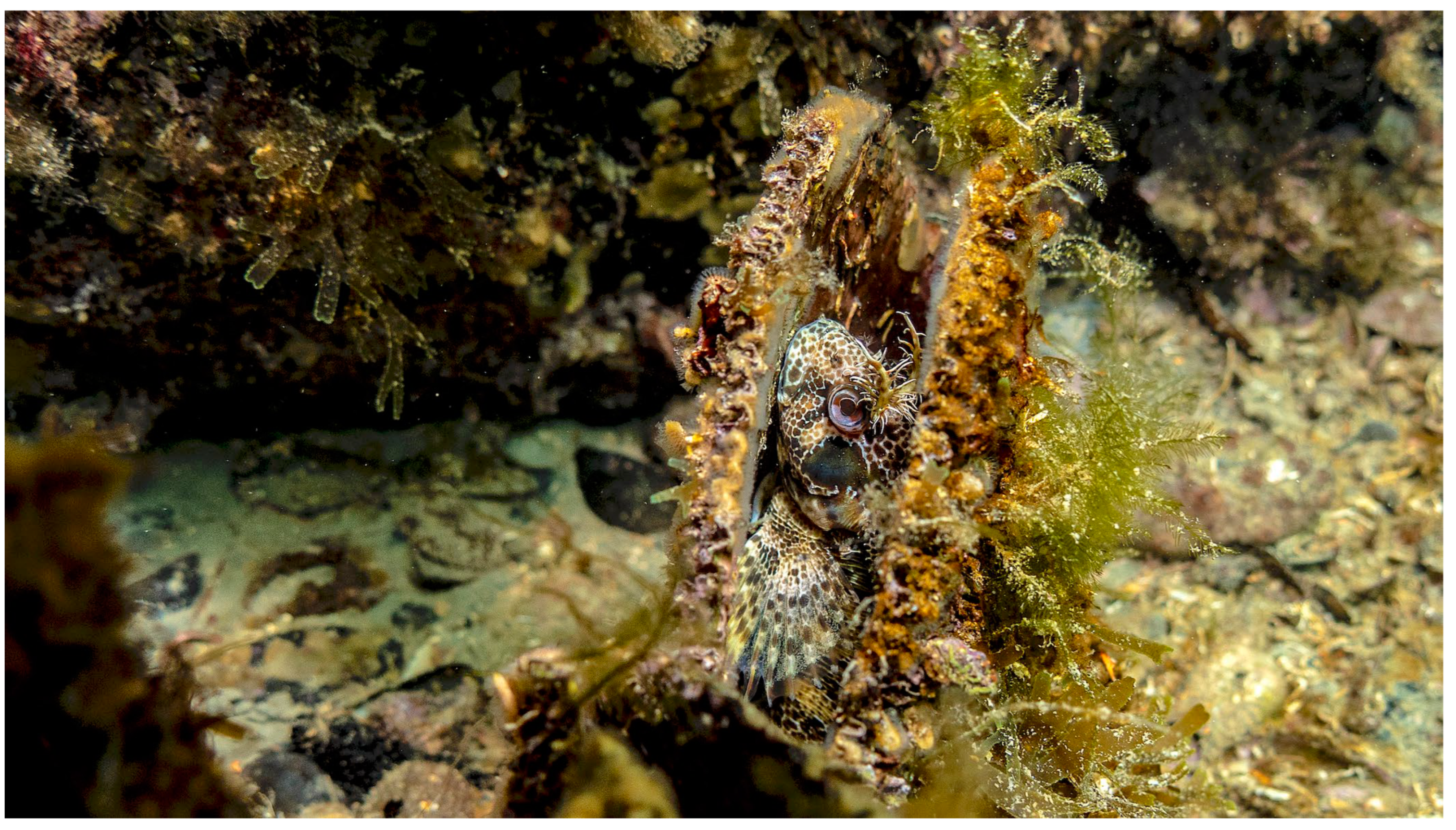

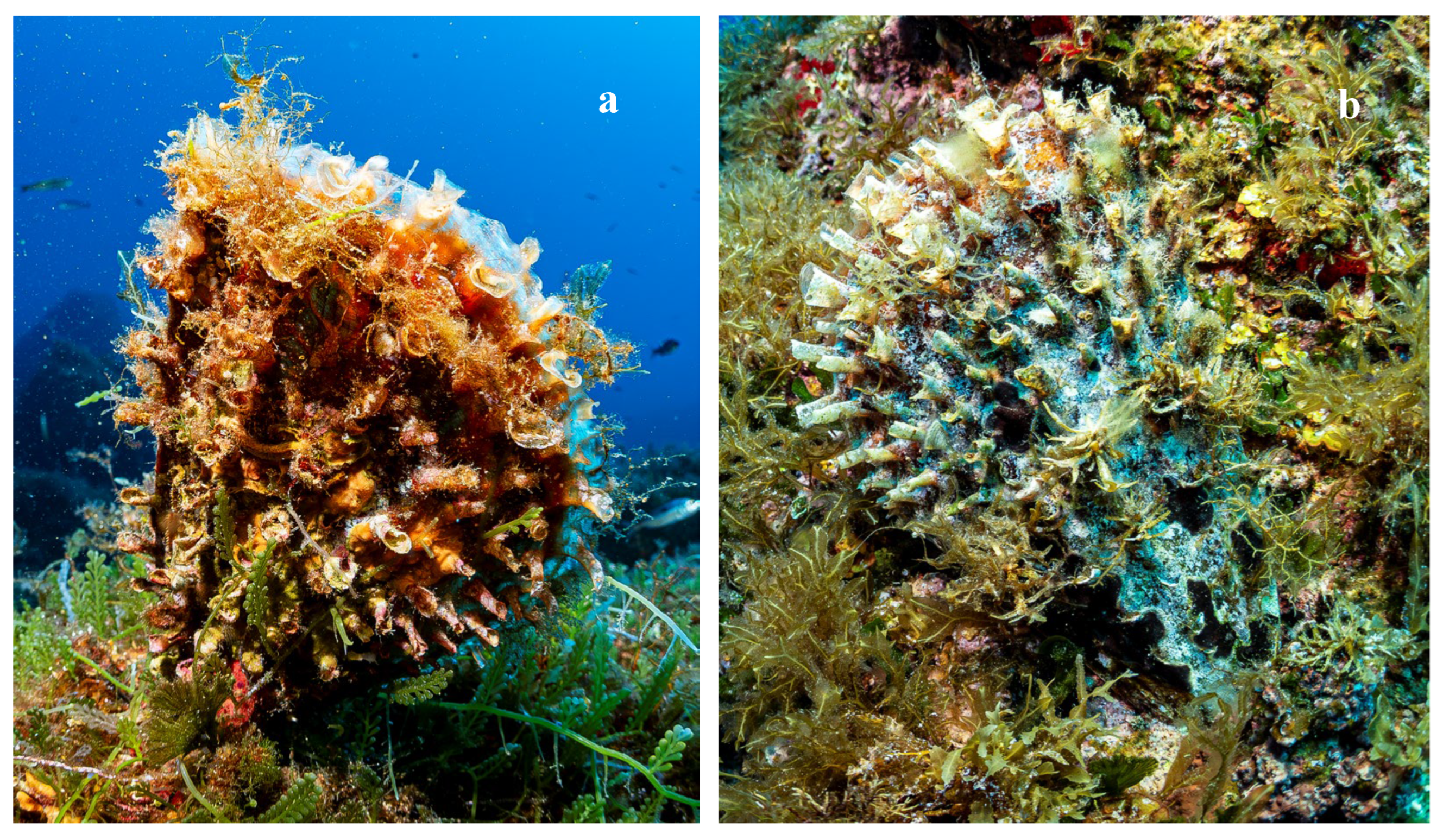

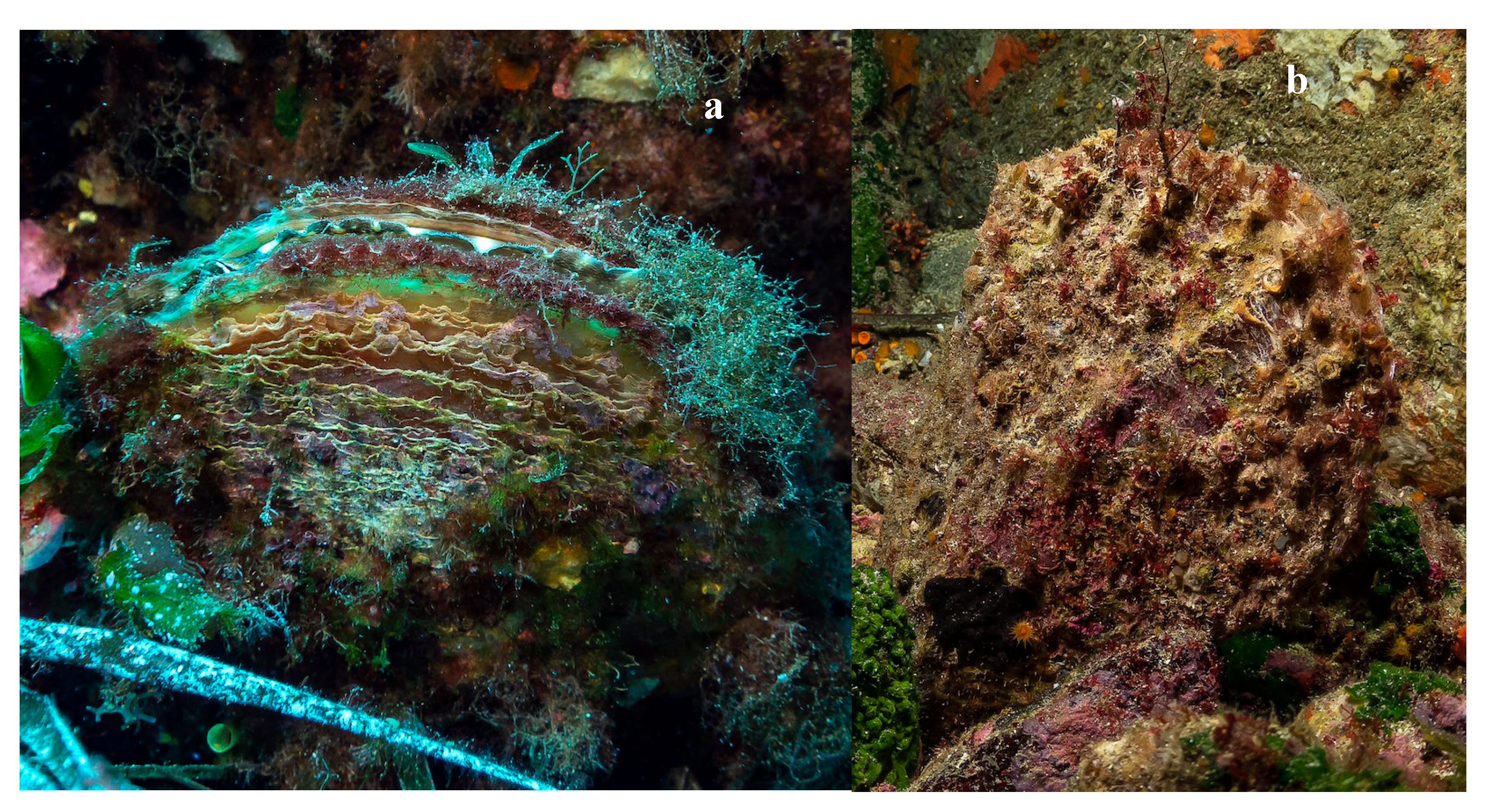

In this very frustrating scenario, the empty shells maintain their important ecological function as ecosystem engineers [

20]. According to [

21], an ecosystem engineer has the capacity of modifying, maintaining and/or creating habitats. The fan mussel’s shells, remaining erect and anchored to the substratum, act like isles of biodiversity on sandy or muddy bottoms, attracting many benthic sessile and vagile organisms. When the individual is alive, only the superior margin remains clean, due to the activity of the mantle, instead the empty shells are completely colonized also in their internal side (

Figure 5). That is why the collection of empty shells is still prohibited and subject to heavy fines.

Concurrent to the quite complete vanishing of

P. nobilis, the sightings of

P. rudis are increasing, mentioned both in scientific literature [

8,

22,

23] and social media, suggesting that this species could benefit from the disappearance of its sister, also colonizing habitats that in origin were exclusive of

P. nobilis.

We observed the first signs of this trend at Pantelleria Island (Sicily Channel, Mediterranean Sea), in October 2022. We have never seen specimens of

P. rudis in all our dives in Taranto, Tremiti and many other Apulian sites; and only sporadic observations are reported from these localities, as evidence of its rarity. Considering the few dives made on the seabeds of the island, the finding of 11 living specimens of

P. rudis, plus one dead, in our opinion is a relevant number (

Figure 6).

Besides, for a long time, we did not seen healthy individuals of

P. nobilis as well. Living specimens of both species were present there, together with few empty shells and all of them were found on rocky or coralligenous bottoms. After a more careful observation, the individuals initially recognized as

P. nobilis, despite they exhibited shells and size typical of the adults of such species, the coloration of the mantle was different; it was not the typical pink [

24], but iridescent with dark belts, more similar to that of

P. rudis (

Figure 7). During the dives, we have observed other individuals exhibiting morphological traits, like the shell ornamentations, the size, and the coloration of the mantle, that seemed to be a mixturse between the two species (

Figure 8). According to [

25], it is possible that they could by hybrids. We did not perform mantle biopsies, to confirm this hypothesis, and even though the putative hybrids exhibited morphological traits quite different from the hybrids showed in [

25], these findings are very interesting and deserve more in-depth investigations.

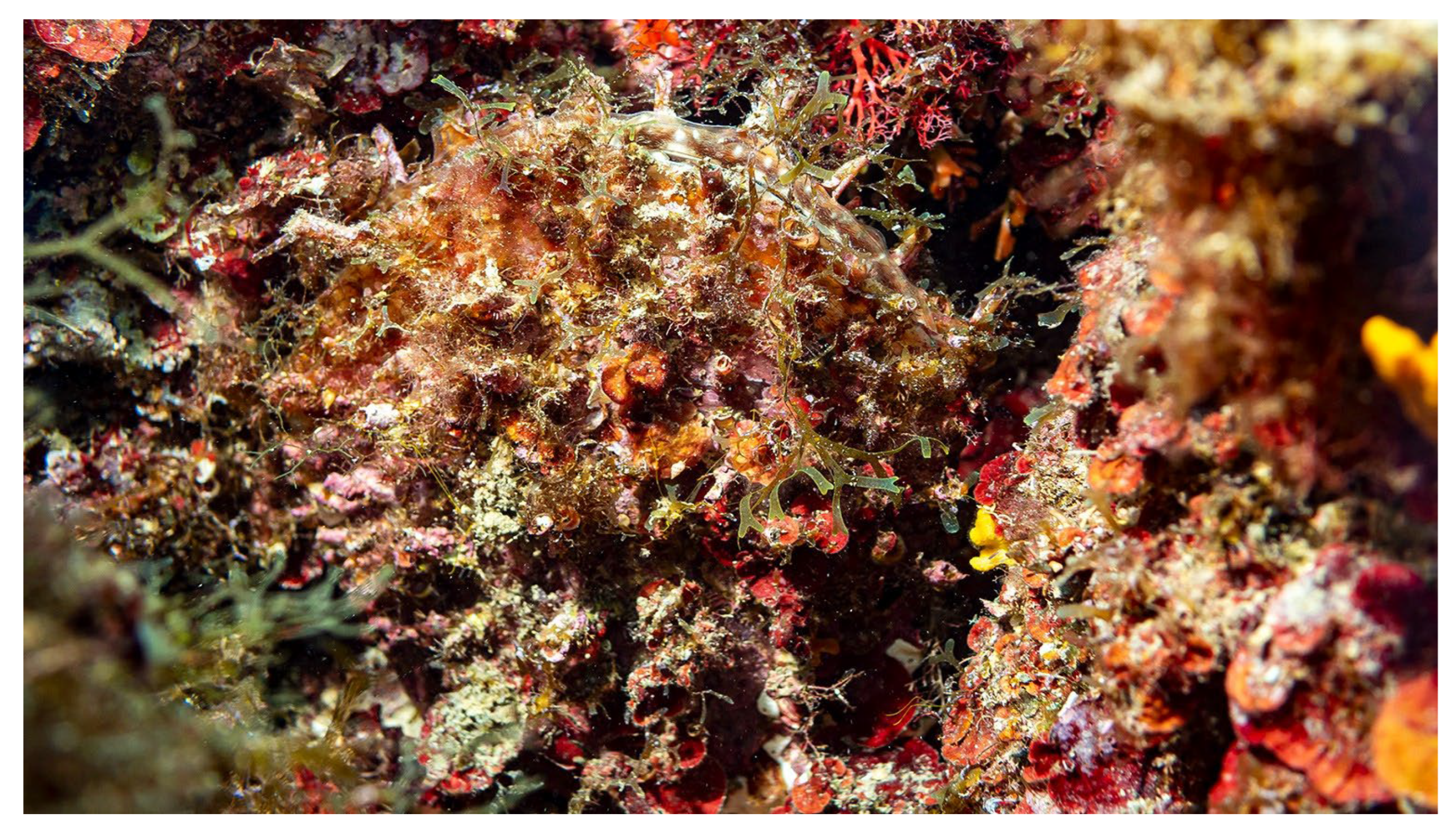

At our knowledge, the first documented reports of

P. rudis in Apulia—and in the Province of Taranto in particular—are dated in summer 2023. Two specimens were reported in a social media forum from a locality 20 km far from Taranto [

8], while we have “discovered” a third at San Vito, a locality nearby the city of Taranto, thanks to the notify of the Diving Center “Taras Sub”. The latter specimen was very difficult to see, settled into a little hole among the coralligenous rocks, the shell completely covered by organisms (

Figure 9).

The first reports of

P. rudis follow the consistent vanishing of its sister from the seabeds along the Apulian coast of the Ionian Sea. In 2022- 2024 we carried out a monitoring activity aimed to discover any survivors of

P. nobilis in this area, by investigating 15 sites along the coast in the province of Taranto. We carried out both dives in the meadows of

Posidonia oceanica and underwater linear transects of 200-300 meters at three depths, 5, 15 and 25 meters. The utilization of underwater scooters allowed us to survey more than 15 km of sea bottom per each depth. No living individuals were observed, and 67 empty shells were registered, most of them at 15 m of depth and outside the

P. oceanica meadows (

Figure 10). In a similar study, extended to the entire south-eastern coast of Apulia [

26], the same situation is reported, confirming the total disappearing of the species from the Apulian seabeds.

At present, this situation is widespread in the whole Mediterranean. Recent studies report that also in areas considered safe environments for the species, after a period of resistance, the survivors were impacted by a mass mortality [

27]. Little unaffected populations holdout, especially in the Eastern Mediterranean [

28,

29,

30]. These individuals could play a crucial role for the natural recolonization of the impacted areas, but, at the same time, according to [

25], these survivors could be hybrids, not purebred individuals of

P. nobilis, and the non-correct identification may cause problems regarding the conservation of the species. This issue must be better understood together with the plausible rise of

P. rudis populations that opens new perspectives of study.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Video S1: Pinna nobilis dead, MP Taranto 2021.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.R.; methodology, F.R., G.F. and G.D.; validation, F.R. and G.D.; formal analysis, F.R. and G.D.; investigation, F.R., G.F. and G.D.; resources, F.R.; data curation, G.D.; writing—original draft preparation, F.R.; writing—review and editing, F.R., G.F. and G.D.; funding acquisition, F.R. and G.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by: Regione Puglia, POR Puglia 2014/2020—Asse VI—Az. 6.5—6.5.a, Project title “M.I.A. Rete Natura 2000 Innovative Environmental Monitoring”, CUP B35F21002450001. The activities at Taranto, Tremiti and Pantelleria were carried out in the framework of the Project “RiPinTa—Relocation of Pinna nobilis in Taranto”, funded by Port Authority of Taranto, Contract Number n. 515787 (2016) and the Citizen Science campaign “SOS Pinna: la Subacquea aiuta la Ricerca”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data are reported in the present publication.

Acknowledgments

Giovanni Squitieri (

www.officinadellimmagine.eu) is acknowledged for his participation in all the underwater activities and for all the photo/video documentation produced.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Lemer, S.; Buge, B.; Bemis, A.; Giribet, G. First molecular phylogeny of the circumtropical bivalve family Pinnidae (Mollusca, Bivalvia): Evidence for high levels of cryptic species diversity. Mol. Phylogenetics Evol. 2014, 75, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fryganiotis, K.; Antoniadou, c.; Chintiroglou, C. Comparative distribution of the fan mussel Atrina fragilis (Bivalvia, Pinnidae) in protected and trawled areas of the north Aegean Sea (Thermaikos Gulf). Mediterr. Mar. Sci. 2013, 14, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basso, L.; Vázquez-Luis, M.; García-March, J.R.; Deudero, S.; Alvarez, E.; Vicente, N.; Duarte, C.M.; Hendriks, I.E. The pen shell Pinna nobilis: a review of populations status and recommended research priorities in the Mediterranean Sea. Adv. Mar. Biol. 2015, 71, 109–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gvozdenovic, S.; Macic, V.; Pesic, V.; Nikolic, M.; Peras, I.; Mandic, M. Review on Pinna rudis (Linnaeus, 1758) (Bivalvia: Pinnida) presence in the Mediterranean. J. Agric. For., 2019, 65, 115–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kersting, D.K.; Ballesteros, E. Is the local extinction of Pinna nobilis facilitating Pinna rudis recruitment? Mediterr. Mar. Sci., 2021, 22, 623–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez-Luis, M.; March, D.; Alvarez, E. Spatial distribution modelling of the endangered bivalve Pinna nobilis in a Marine Protected Area. Mediterr. Mar. Sci., 2014, 15, 626–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kersting, D.K.; García-March, J.R. Long-term assessment of recruitment, early stages and population dynamics of the endangered Mediterranean fan mussel Pinna nobilis in the Columbretes Islands (NW Mediterranean). Mar. Environ. Res., 2017, 130, 282–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zotou, M.; Papadakis, O.; Catanese, G.; Stranga, Y.; Ragkousis, M.; Kampouris, T.E.; Naasan Aga-Spyridopoulou, R.; Papadimitriou, E.; Koutsoubas, D. , Katsanevakis, S. New kid in town: Pinna rudis spreads in the eastern Mediterranean. Mediterr. Mar. Sci., 2023, 24, 709–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsanevakis, S.; Carella, F.; Çinar, M.E.; Čizmek, H.; Jimenez, C.; Kersting, D.K.; Moreno, D.; Rabaoui, L.; Vicente, N. The fan mussel Pinna nobilis on the brink of extinction in the Mediterranean. In Imperilled: The Encyclopaedia of Conservation; Della Sala, D.A., Goldstein, M.I., Eda., *!!! REPLACE !!!*, Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Nederlands, 2022; Volume 2, pp. 700–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carella, F.; Prado, P.; Vico, G.D.; Palić, d.; Villari, G.; García-March, J.R.; Tena-Medialdea, J.; Melendreras, E.C.; Giménez-Casalduero, F.; Sigovini, M.; Aceto, S. A widespread picornavirus affects the hemocytes of the noble pen shell (Pinna nobilis), leading to its immunosuppression. Front. Vet. Sci., 2023, 10, 1273521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kersting, D.; Benabdi, M.; Čizmek, H.; Grau, A.; Jimenez, C.; Katsanevakis, S.; Öztürk, B.; Tuncer, S.; Tunesi, L.; Vázquez-Luis, M.; Vicente, N.; Otero Villanueva, M. Pinna nobilisPinna nobilis. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2019, e.T160075998A160081499. [CrossRef]

- Centoducati, G.; Tarsitano, E.; Bottalico, A.; Marvulli, M.; Lai, O.R.; Crescenzo, G. Monitoring of the endangered Pinna nobilis Linné, 1758 in the Mar Grande of Taranto (Ionian Sea, Italy). Environ. Monit. Assess., 2007, 131, 339–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubino, F.; Cecere, E.; Petrocelli, A.; Casale, A.; Casale, V.; Passarelli, S. Recent observations of Pinna nobilis (Mollusca. Bivalvia) in the Mar Piccolo basin (Gulf of Taranto, Mediterranean Sea). Biol. Mar. Medit., 2015, 22, 107–708. [Google Scholar]

- Fanelli, G.; Rubino, F. Relocation of Pinna nobilis (Mollusca, Bivalvia) in the port of Taranto. Biol. Mar. Medit., 2017, 24, 142–143. [Google Scholar]

- Panarese, R.; Tedesco, P.; Chimienti, G.; Latrofa, M.S.; Quaglio, F.; Passantino, G.; Buonavoglia, C.; Gustinelli, A.; Tursi, A.; Otranto, D. Haplosporidium pinnae associated with mass mortality in endangered Pinna nobilis (Linnaeus 1758) fan mussels. J. Invertebr. Pathol., 2019, 164, 32–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiscar, P.G.; Rubino, F.; Paoletti, B.; Francesco, C.E.D.; Mosca, F.; Salda, L.D.; Hattab, J.; Smoglica, C.; Morelli, S.; Fanelli, G. New insights about Haplosporidium pinnae and the pen shell Pinna nobilis mass mortality events. J. Invertebr. Pathol., 2022, 190, 107735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vázquez-Luis, M.; Alvarez, E.; Barrajón, A.; García-March, J.R.; Grau, A.; Hendriks, I.E.; Jimenez, S.; Kersting, D.; Perez, M.; Ruiz, J.M.; Sanchez, J.; Villalba, A.; Deudero, S. S.O.S. Pinna nobilis: A mass mortality event in western Mediterranean Sea. Front. Mar. Sci., 2017, 4, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastrototaro, F. (University “Aldo Moro”, Bari, Italy). Personal communication, 2019.

- Denti, G.; Fanelli, G.; Tiscar, P.G.; Paoletti, B.; Hattab, J.; Mastrototaro, F.; Carella, F.; Villari, G.; Montesanto, F.; Chimienti, G.; Rubino, F. Mass mortality of Pinna nobilis Linnaeus, 1758 (Mollusca, Bivalvia) in the Taranto and Tremiti Islands populations: citizen science to help scientists. Biol. Mar. Medit., 2023, 27, 21–24. [Google Scholar]

- Iannucci, S.; Auriemma, R.; Davanzo, A.; Ciriaco, S.; Segarich, M.; Del Negro, P. Can the empty shells of Pinna nobilis maintain the ecological role of the species? A structural and functional analysis of the associated mollusc fauna. Diversity, 2023, 15, 956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, C.G.; Lawton, J.H.; Shachak, M. Organisms as ecosystem engineers. Oikos, 1994, 69, 373–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donato, G.; Vázquez-Luis, M.; Nebot-Colomer, E.; Lunetta, A.; Giacobbe, S. Noble fan-shell, Pinna nobilis, in Lake Faro (Sicily, Italy): Ineluctable decline or extreme opportunity? Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci., 2021, 261, 107536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oprandi, A.; Aicardi, S.; Azzola, A.; Benelli, F.; Bertolino, M.; Bianchi, C.N.; Chiantore, M.; Ferranti, M.P.; Mancini, I.; Morri, C.; Montefalcone, M. A tale of two sisters: the southerner Pinna rudis is getting North after the regional extinction of the congeneric P. nobilis (Mollusca: Bivalvia). Diversity, 2024, 16, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-March, J.R.; Vicente, N. Protocol to study and monitor Pinna nobilis populations within marine protected areas. Malta Environmental and Planning Authority, 2006, MedPAN Project, 78 pp.

- Vázquez-Luis, M.; Nebot-Colomer, E.; Deudero, S.; Planes, S.; Boissin, E. Natural hybridization between pen shell species: Pinna rudis and the critically endangered Pinna nobilis may explain parasite resistance in P. nobilis. Mol. Biol. Rep., 2021, 48, 997–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pensa, D.; Fianchini, A.; Grosso, L.; Ventura, D.; Cataudella, S.; Scardi, M.; Rakaj, A. Population status, distribution and trophic implications of Pinna nobilis along the South-eastern Italian coast. npj Biodiversity, 2022, 1, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donato, G.; Lunetta, A.; Spinelli, A.; Catanese, G.; Giacobbe, S. Sanctuaries are not inviolable: Haplosporidium pinnae as responsible for the collapse of the Pinna nobilis population in Lake Faro (central Mediterranean). J. Invertebr. Pathol., 2023, 201, 108014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papadakis, O.; Mamoutos, I.; Ramfos, A.; Catanese, G.; Papadimitriou, E.; Theodorou, J.A.; Batargias, C.; Papaioannou, C.; Kamilari, M.; Tragou, E.; Zervakis, V.; Katsanevakis, S. Status, distribution, and threats of the last surviving fan mussel populations in Greece. Mediterr. Mar. Sci., 2023, 24, 679–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karadurmus, U.; Benli, T.; Sari, M. Discovering new living Pinna nobilis populations in the Sea of Marmara. Mar. Biol., 2024, 171, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zotou, M.; Gkrantounis, P.; Karadimou, E.; Tsirantinis, K.; Sini, M.; Poursanidis, D.; Azzolin, M.; Dailianis, T.; Kytinou, E.; Issaris, Y.; Gerakaris, V.; Salomidi, M.; Lardi, P.; Ramfos, A.; Spinos, E.; Dimitriadis, C.; Papageorgiou, D.; Lattos, A.; Giantis, I.A.; Michaelidis, B.; Vassilopoulou, V.; Miliou, A.; Katsanevakis, S. Pinna nobilis in the Greek seas (NE Mediterranean): on the brink of extinction? Mediterr. Mar. Sci., 2020, 21, 575–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).