1. Introduction

COVID-19 is an infectious disease transmitted by droplets and close contact caused by SARS-CoV-2. The first human cases were reported in December 2019 in Wuhan City, China [

1]. Most infected people experience mild to moderate respiratory illness and recover without any special treatment. The risk group with a higher chance of developing a serious illness are people with cardiovascular diseases, chronic respiratory diseases, cancer, the elderly, and diabetics. Anyone can get sick with COVID-19 and become seriously ill and die at any age [

2]. Among many lifestyle changes the pandemic brought, like sleep, work, and shopping changes, were social distancing and masking[3-10].

In April 2020 WHO issued a statement that did not recommend the wide use of masks by healthy people in the community [

11]. In June 2020 WHO updated their advice of preventing COVID-19 when transmission from presymptomatic or even asymptomatic individuals was self-evident. New guidance on the targeted continuous use of medical masks by health workers in clinical areas and recommendations for mask use in the general population [

11]. Instructions were based on results of observational studies that found out that wearing a mask is associated with reduced risk of infection among health workers [

12]. Masks are aimed to prevent the spread of the virus through direct contact and to protect the wearer from infection[

13]. Nevertheless, public masking may result in side effects in both physical and mental areas[

14].

Masks have been recommended as a strategy of prevention to suppress transmission and save lives. Face masks are used to trap the particles or fluid drops in a filter to avoid or reduce the transfer of particles between the human lungs and the external environment [

15]. Most used types of protective masks during the pandemic were: surgical, N95, cloth, and FFP2/FFP3. N95 masks offer higher degrees of protection than surgical and fabric masks, but most N95 respirators fail to fit the face adequately. Fit is critical to provide promised protection for the wearer[

16]. To ensure the effectiveness of masks, rules need to be followed, such as physical distancing, keeping rooms well-ventilated, personal hygiene, and avoiding mass gatherings.

The research question was whether wearing a protective mask had any effect on the temporomandibular joint. We hypothesized that face mask use is linked to deviation in TMJ and associated structures’ health. The longer the mask is worn, the greater the discomfort in the temporomandibular region.

The temporomandibular joint is a paired articulation that consists of two surfaces located on the mandible and squamous part of the temporal bone. These joints enable symmetrical movements: protrusion and retraction of the mandible, raising and lowering the mandible, as well as asymmetric chewing movements. The temporomandibular joint is the only movable joint of the skull. Improper adhesion of the articular surfaces causes joint dysfunction, which is manifested by an incorrect moving path of the mandible and characteristic crackling sounds. The symptoms of temporomandibular joint disorder (TMD) could be arthralgia, masticatory spasm, tightness around the face in the morning, otalgia, inability to fully open mouth[

17] and tension headache, which may lead to depression[

18]. 80% of patients treated for temporomandibular joint disorder are women. The reason behind the sexual disparity is not clear, but both animal and human studies have suggested elevated levels of estrogen may predispose to TMJ dysfunction. TMD peak occurrence appears between the second and fourth decade of life[

19,

20].

The most recommended temporomandibular joint disorder classification scale is DC/TMD (Diagnostic Criteria for Temporomandibular Disorders). The scale contains Axis I and Axis II. Axis I is based on clinical signs assessed by the examiner, and it divides patients into groups. Group I – Myofascial Pain Disorder with subgroups - (a) myofascial pain without limited mouth opening, (b) pain with limited mouth opening. Group II – Temporomandibular Joint Disc Displacement Disorder - (a) disc displacement with displacement, (b) acute form of disc displacement without displacement, (c) chronic form of (b) type. Group III – Temporomandibular Joint Degenerative Disease Disorder - (a) arthralgia, (b) osteoarthritis with joint pain, (c) osteoarthritis without joint pain. Axis II consists of Graded Chronic Pain Scale, Pain drawing, Jaw Functional Limitation Scale, Oral Behaviors Checklist, and questionnaires examining the presence of depression or anxiety disorders (PHQ-4, PHQ-9, GAD-7, PHQ-15). Axis II facilitates determining the impact of temporomandibular pain on the patient’s psychological sphere[

21,

22].

The use of face masks was associated with the exacerbation of acne and the appearance of new acne lesions, as well as the deterioration of the general condition of the skin[

23,

24]. These adverse reactions may result in scratching and touching the mask, which reduces its effectiveness in protecting against virus transmission[

25].

Continuous use of masks by medical personnel causes headaches de novo, exacerbates the pain, and increases its frequency in susceptible people[2629]. One of the presumed causes may be respiratory alkalosis and hypocarbia. It was noted that most health workers had to take analgesics. Some even took time off work for this reason[

30]. A survey of operating room staff found that N95 masks cause more discomfort than surgical masks. This is probably due to the tightness of this type of mask[

31]. Pain related to protective mask wearing can be caused by pressure on a nerve or its branch, and it increases the longer the mask is worn. Pain was localized in the nasal region, followed by pain in the zygomatic, parathyroid, temporal, occipital, and submental regions. All were areas of contact with facemasks. The localization of most symptoms suggests the involvement of the trigeminal nerve, particularly the maxillary and mandibular branches, and usually the localization of the pain may be attributed to the involvement of single, small, or terminal trigeminal branches. 15% of the population complaining of neuropathic pain also reported suffering from reduced skin sensitivity, probably because of skin inflammation involving the intradermic terminal nerve fibers [

32].

The COVID-19 pandemic was a challenging time for people all over the world. During this tough period, masks generated a sense of security, though not many treatment options were available[

33]. For many, the mask was a symbol of morality because it meant not only protecting oneself but also other people. In 2020 daily protective mask-wearing has become the new normality[

32]. The effects of wearing face masks during the pandemic on headaches and discomfort are well fathomable. Mandatory use of face masks, despite the side effects, is inevitable to arrest the Coronavirus Disease 2019.

The study aimed to explore the influence of masks on the temporomandibular joint.

2. Materials and Methods

Given the niche character of our topic, we decided to make our search as broad as possible. This was also the purpose of choosing “systematic search and review” as a form for this paper because according to the article by Grant and Booth from 2009[

34], it provides an opportunity to conduct a comprehensive search process and evaluation, simultaneously leaving a leeway for critique.

In our research, we have used 5 databases: PubMed, Embase, Ebsco, Web of Science, and Google Scholar. The search took place from 10-16 February 2024. We have not registered our research in any register of systematic reviews, such as PROSPERO.

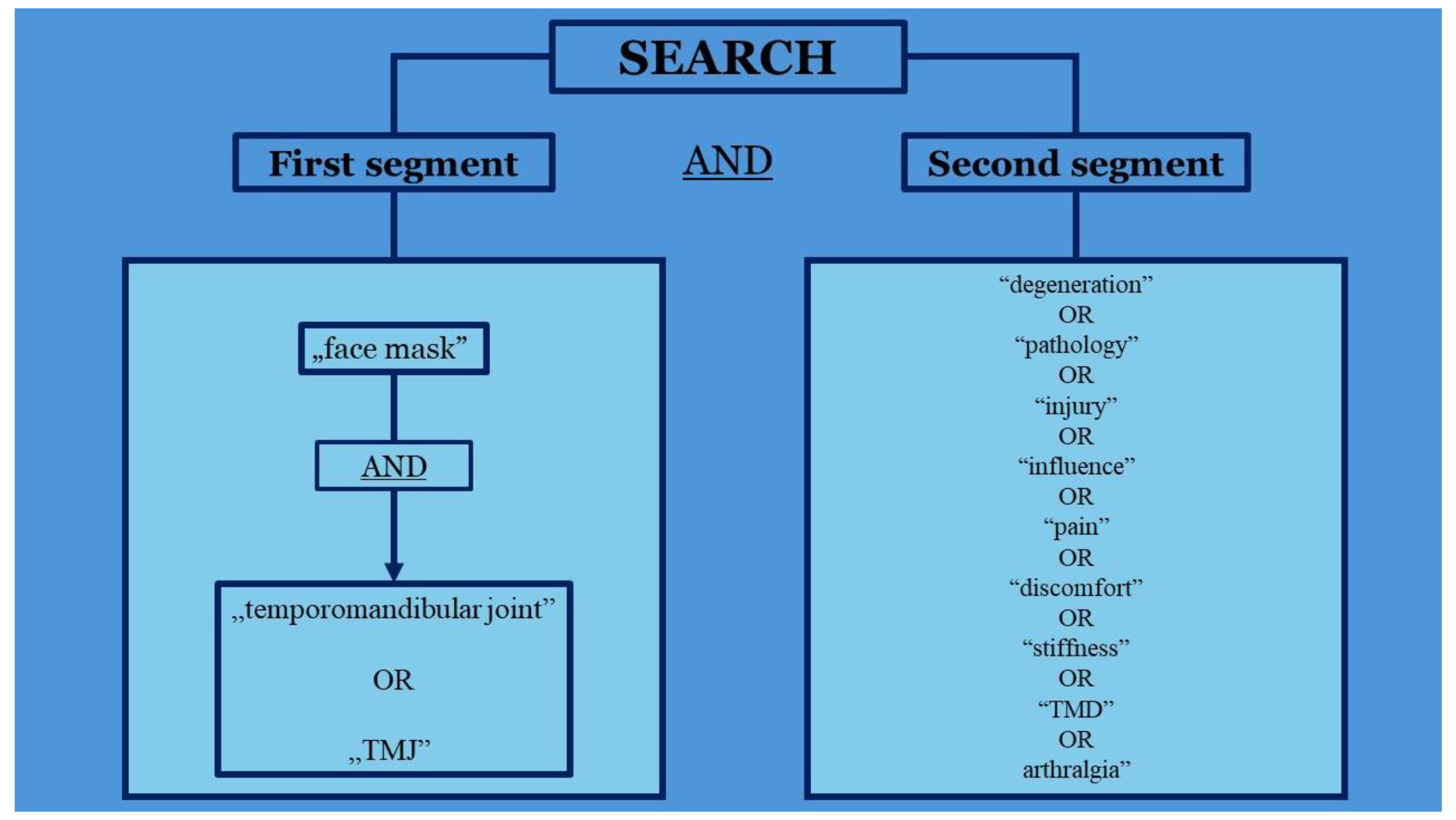

Our search focused on abnormalities related to the temporomandibular joint (TMJ) that may have been caused by the prolonged use of a face mask as a self-protection measure. We have used a combination of keywords where only one combination was used per search. They consisted of 2 segments:

First segment:

(("face mask" AND ("temporomandibular joint" OR “TMJ”))

Second segment:

(“degeneration” OR “pathology” OR “injury” OR “influence” OR “pain” OR “discomfort” OR “stiffness” OR “TMD” OR “arthralgia”)

In summary:

(("face mask" AND ("temporomandibular joint" OR TMJ))) AND (“degeneration” OR “pathology” OR “injury” OR “influence” OR “pain” OR “discomfort” OR “stiffness” OR “TMD” OR “arthralgia”)

In the first segment “face mask” was matched with interchangeable “temporomandibular joint” or “TMJ”, as authors can refer to this joint in its full name or abbreviation. From the second segment, only one option was chosen per search. The algorithm was depicted on a schematic (

Figure 1).

In the next step, we performed a thorough search of all databases we chose using this algorithm. We focused only on original articles. During the search, we analyzed the titles and abstracts of the papers. Studies only related to face mask influence on TMJ were accepted for further analysis.

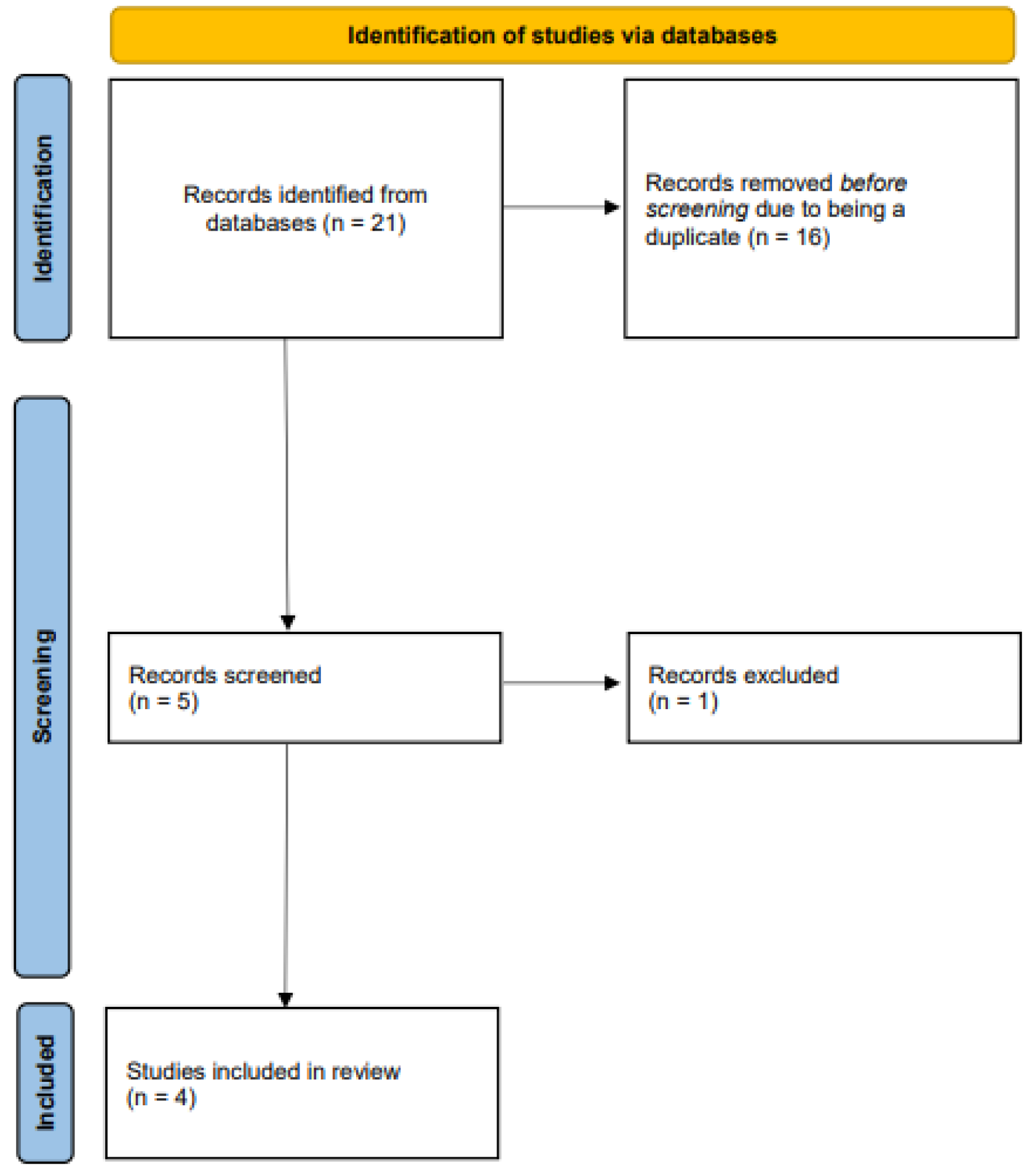

The initial search yielded n=21 studies (PubMed n=4, Embase n=5, Ebsco n=4, Web of Science n=4, Google Scholar n=4). After excluding duplicates (n=16) we screened these papers and excluded 1 irrelevant study after reviewing the full text. After that, we were left with n=4 articles.

Next, we proceeded to citation search. Sources of base papers were analyzed. Other articles were also added to the base which at the end was composed of 66 articles.

The process of systematization was depicted on a flowchart (

Figure 2).

Deep analysis later was performed by one researcher (MK), including the use of JBI Critical Appraisal Tools, which outcomes are depicted in

Table 1 and

Table 2. We provide filled checklists in a PDF form available in supplementary materials marked as “Supplementary material 1-4”. Their work was reviewed by one of the other authors (SJP). Then the outcome of each paper was systematized and presented independently, focusing mainly on the effects of masks on TMJ, nonetheless other influences that were found in the studies were also pointed out.

3. Results

A total of 4 studies (

Table 3.) were used to confirm the negative influence of prolonged mask use on the temporomandibular joint[35-38].

Zuhour et al. via a brief survey questionnaire presented that both the placement and the readjusting of the mask have negative effects on the temporomandibular joint. Patients were questioned on their mask usage and lifestyle habits. There were 3 groups:

A - (39) – repetitive movements associated with masks as the only risk factor (study group)

B - (55) - lifestyle/parafunctional habits

C - (12) – no known risk factors

All the participants used only one type of mask. 148 people participated in the study but 42 were excluded because of comorbid diseases, temporomandibular disorder (TMD) lasting more than a year (which misses the COVID-19 impact on the TMJ), or any history of orofacial surgeries. 106 people in total participated in the survey. A variety of symptoms were reported, such as: mostly pain of the TMJ, stiffness, and joint lock. Data was summed up in

Table 4.

MRI was used to observe disc displacement and osteoarthritis in participants. Most commonly thickening of the lateral pterygoid muscle was found.

TMJ action includes both forward and downward movements. Such repetitive motions are the cause of the destabilization of the ligaments supporting the joint. Masks’ sizing which is incorrect increases the negative outcome of wearing them. The differences in masks’ structure were the main limitation of this study. It has been concluded that improper size of the mask increases the risk of developing symptoms concerning TMJ.

Marques-Sule et al. in their study touched not only on the effects of masks on temporomandibular pain but also headaches and the quality of life (QoL), the latest being influenced also by mask type. A questionnaire has been conducted, including the appearance of bruxism, chewing discomfort, and TMJ pain. Symptoms were summed up in

Table 5.). People with musculoskeletal injuries in the craniofacial area, those who wore masks for a shorter period than 2 hours, and institutionalized subjects were excluded from the research. A total of 542 participants were included.

Headache was more intense with continuous mask usage (CMU) than without masks. Its frequency with cloth mask influence was the most significant, then FFP2, but when it came to surgical masks there was no difference between using masks and not using them.

TMJ discomfort was reported by almost half of the people, and it increased by 31% with FFP2 masks but not when it came to cloth or surgical masks. TMJ pain was characterized using a visual analog scale (VAS): 0 – meaning “no pain” and 10 – meaning “maximum pain”. The mean score was 1.56 before mask use and 2.28 during mask use.

QoL was measured by Cantril’s Ladder of Life scale using an image of a ladder numbered 0-10, 0 meaning the worst possible life and 10 being the best possible life. Participants were asked two questions: “In which step do you think you are on without using a mask?” and “In which step do you think you are on using a mask?” QoL decreased regardless of mask type, meaning a 38% decrease for surgical masks and 31% for either FFP2 or cloth masks. The mean VAS score during mask use was 5.37 and 8.26 without them.

The problem of masks’ influence was also considered by d’Apuzzo et al. via an online questionnaire that reached 665 people. Pain in the preauricular area, noise at the TMJ, headache, and wearing modalities concerning masks were researched.

FFP2/FFP3 masks were used by 50.3% of the subjects while 43.5% used surgical masks. Masks with two elastics were worn by 87% of the respondents. The duration of mask wear differed among participants. Most (53.6%) wore masks for less than 4 hours, while 1.8% reported wearing them for 12 hours consecutively.

400 participants reported new pain in the preauricular region while wearing masks, and 263 reported no painful symptoms. 147 participants felt pain during mask wear lasting for 4-8 hours consecutively. The outcome differed between mask types. 41.3% of subjects using surgical masks reported pain/discomfort in the region anterior to the ears while 54.3% of FFP2/FFP3 users reported the same.

Most people (92.2%) did not report hearing any noise at the TMJ region while chewing since wearing masks. 70% of subjects referred to avoiding talking while wearing masks because it increases the appearance of preauricular pain and new/increased noise heard at the TMJ.

When it came to headaches, 253 reported suffering from headaches during mask wear, while 411 did not report this symptom. Headaches were most common among subjects who wore masks for more than 8 hours in total and for less than 4 hours consecutively. This pain was most significant while wearing masks with two elastics behind the ears (87.4%) and with FFP2/FFP3 masks (57.7%).

The most negative effects touched users of FFP2/FFP3 masks who wore them for more than four hours continuously. Also, two elastics behind the ears increased the described influence.

Carikci et al. succeeded in investigating the effects of mask wear during the COVID-19 pandemic. The influence of masks on discomfort, TMD, fatigue, and headache was researched. People with a history of head or face surgery or a history of malignancy were excluded from the research. 909 participants took part in the study. Among participants of the survey 3 groups were formed depending on the duration of mask wear:

Jaw (14%), facial (16.1%), and neck (16.9%) pain as well as cheek tension (16.1%) was the most intense in the third group along with headache (51.9%). Different types of headaches were also distinguished between people. Most common headache types were: temporal headache in Group 1 (25.7%) and Group 2 (33.7%) and tension headache in Group 3 (33.1%)

The pain at trigger points of the TMJ on the M. Temporalis and M. Masseter were measured by the Numerical Rating Scale (NRS) - from 0-10, 10 being the worst pain. Both Temporal and Masseter Muscle Trigger Points pain were stronger in the second and third groups. TMD severity was evaluated by the Fonseca Anamnestic Index (FAI) between 0 and 100. 0-15 meaning no symptoms, 20-45 meaning “mild”, 50 – 65 “moderate” and 70 – 100 being “severe”. The median score turned out to be 25 in Group 1 and 35 in Group 2 and Group 3. The duration of mask wear increased TMD prevalence and total fatigue. Masks could put pressure on the mentioned points causing incorrect muscle movement and asymmetry of the system.

4. Discussion

Face mask use is not indifferent to the health and well-being of a person. As presented in the introduction, masks can induce headaches, possibly due to alkalosis[

30]. The studies we have found also treat this matter, and their outcomes are no different[

36,

37,

38]. Of 2116 people included in those studies, 1364 participants reported headaches due to face mask use. There are also multiple reports regarding mask-induced dermatological problems. Acne is the most prevalent problem associated with mask use[23,24,39-42], but it can also reduce the general condition of the skin[

24,

43] or induce itch[

25,

44,

45], which contributes to overall discomfort that exists during mask use[

31,

46,

47]. Face masks can increase transepidermal water loss, as well as skin hydration, erythema, pH, and sebum secretion, which all can contribute to worse skin condition[

48]. One review stated that the microclimate under the mask can be like a greenhouse, which favors microbiota involved in the development of acne[

49]. One of the biggest causes of discomfort are also breathing problems[42,50-53], especially in people suffering from asthma[

53]. The prolonged face mask use can also affect ocular health by exacerbating dry eye symptoms [

54,

55,

56], [

57] or creating visual artifacts due to improper fit[

58], which, as one of the existing cases showed, also plays a role in worsening those symptoms by directing the exhaled air into the user’s eyes[

59]. Worth noting is that one of the studies discussed in this paper regarding the influence of mask use on TMJ disorders, also showed that the improper fit of a face mask can impair this joint’s health due to repetitive movements [

35], which could be induced by discomfort coming from blowing exhaled air into the eyes.

Mask use can also have a toll on the doctor-patient relationship, where it affects the effectiveness of clinical practice by altering the ability to understand the words that the other person is saying[

60]. It is more visible in people with impaired hearing[

61,

62]. Alarmingly, masks decrease CFMT-K (Cambridge Face Memory Test for children[

63]) scores, which means they also influence face recognition in children[

64], furthermore masks decrease the quality of communication between children and teachers who wear masks which can be caused by insufficient volume of the mask user’s voice and lack of information from lip gestures[

65]. In other psychological aspects, masks induce anxiety in people who are using them for longer periods [

66,

67].

The number of studies present, regarding the influence of face mask use on TMJ is very limited. We have identified only four papers published in peer-reviewed journals. Even though we have searched for papers discussing disorders correlated with prolonged mask use from any year, papers that fitted our criteria discussed only patients that had TMD due to face mask use during the COVID-19 pandemic. We are aware of the psychological effect that it had on people all over the world and its importance in developing TMD and bruxism due to elevated stress and anxiety (to which masks also can contribute as stated in the previous paragraph), what was discussed in two systematic reviews[

68], [

69]. The latter shows us the importance of expanding the research to different professions with prolonged face mask use (i.e. surgeons, operating room staff, pathologists), as the influence of COVID-19 could have influenced the outcome of studies solely based on pandemic patients.

From existing research, it is apparent that prolonged use of face masks can be associated with TMJ discomfort[

36]. Research also suggests face mask use can even cause pain in the preauricular area[

37], more prominent with repetitive jaw movements[

35], which is one of the temporomandibular disorders diagnostic criteria[

21,

22]. One of the studies[

38] suggested that the prevalence of temporomandibular disorders can be linked to pressure put by the mask on the muscles responsible for masseteric movements. There is evidence that it may be one of the mechanisms as wearing a mask influences the resting bioelectric activity of masticatory muscles, which was observed in healthy patients[

70] and patients suffering from TMD[

71]. According to Florjanski et al. 2019[

72], biofeedback is a useful tool in working with masticatory muscle activity, which elevates the trustworthiness of these studies.

One of found studies also implies that wearing an incorrect-size mask can be a major factor in the development of TMJ dysfunction symptoms[

35]. Improper face mask fit forces the user to adjust it by moving the mandible which, when repeated chronically, favors the development of TMD symptoms (86,6% for TMJ pain, 82,1% for articular noises, and 64,6% for joint tension in the group where repetitive movements associated with masks as the only risk factor occurred). If it comes to the type of mask, the FFP2 or FFP3 masks have a higher risk of causing discomfort or pain regarding the temporomandibular joint[

36,

37] in comparison to surgical or cloth masks, due to increased pressure put on the user’s face. Use of FFP3 masks over the recommended 1h can even lead to facial pressure injuries[

73]. It creates a possibility that if the pressure put on the user’s face is significant enough to cause an injury as an effect of prolonged use, it could also influence the position of the mandible, and thus the health of the temporomandibular joint. When searching for a substitute, it’s safer to lean towards surgical masks, as cloth/fabric masks are proven to have lower protective quality[

74,

75]. There is also a potential to enhance the surgical masks by infusing them with quaternary ammonium salts[

76], which makes them an even better substitute for the FFP3 type. Devices like the one proposed by Bao et al. 2021[

77], can decrease the time of mask usage while simultaneously providing a safe environment for proximity settings.

Despite our wide range of research, we could not identify any more studies on this topic. We think it is a lost opportunity that there are so few studies that would explore this problem because in our opinion there is potential in connecting prolonged mask use with TMJ abnormalities when working with TMD patients. Adding prolonged mask use as a risk factor for developing abnormalities in the temporomandibular joint into the diagnostic process could improve the rate of correct diagnoses, especially after the COVID-19 era, and in people whose job is strictly connected with long periods of mask use (i.e. surgeons, anesthesiologists, surgical nurses, and other members of operation block staff as well as pathologists).

If we look at the definition of quality of life (QoL) established by the World Health Organization (WHO) defines it as “individuals' perceptions of their position in life in the context of the culture and value systems in which they live and about their goals, expectations, standards and concerns”[

78], we can easily jump into the conclusion, that all of the existing problems that masks are responsible for, can affect individual’s QoL. That includes the topic we are discussing in this paper – the temporomandibular joint, what’s more, one of the studies included in this review showed a decrease in QoL in the use of all mask types[

36], measured by two Cantril’s Ladder of Life scales, which compared well-being of participants with and without using the mask.

5. Conclusions

Considering our findings, the potential link between prolonged use of protective face masks and temporomandibular joint (TMJ) dysfunction or related discomfort is evident. The scarcity of research in this area is concerning, underscoring the need for further investigation to better understand its impact on individuals' quality of life.

Retrospective studies examining patients diagnosed with temporomandibular disorders (TMD) during the COVID-19 pandemic could offer invaluable insights into this issue. Additionally, researchers must prioritize investigations into professions that entail prolonged mask use, such as surgeons, operating room staff, and pathologists. By doing so, we can implement improved work hygiene and safety measures to safeguard the well-being of these essential workers.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at Supplementary materials

Author Contributions

SJP contributed to the conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, and writing the original draft. He was the leading contributor to materials and methods, administration, visualization, and preparation of the final manuscript.

EK and MK contributed to the data curation, formal analysis, investigation, and writing the original draft.

MM contributed to the conceptualization of the study and was a supporting contributor to materials and methods, formal analysis, supervision, visualization, and preparation of the final manuscript.

ZD was the lead supervisor of the study and was a supportive contributor to the visualization and preparation of the final manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

We would like to deeply thank our friend and colleague Grzegorz Ciamciak for being the inspiration for this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- S. Umakanthan et al., “Origin, transmission, diagnosis and management of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19),” Postgrad Med J, vol. 96, no. 1142, p. 753, Dec. 2020. [CrossRef]

- “Coronavirus.” Accessed: Apr. 15, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.who.int/health-topics/coronavirus#tab=tab_1.

- F. D. B. De Sousa, “Pros and cons of plastic during the COVID-19 pandemic,” Recycling, vol. 5, no. 4. MDPI AG, pp. 1–17, Dec. 01, 2020. [CrossRef]

- S. Y. Tobin, T. M. Halliday, K. Shoaf, R. D. Burns, and K. G. Baron, “Associations of Anxiety, Insomnia, and Physical Activity during the COVID-19 Pandemic,” Int J Environ Res Public Health, vol. 21, no. 4, p. 428, Apr. 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. Rapa, V. Giannetti, M. Boccacci Mariani, F. Di Francesco, and A. Porpiglia, “Could Food Delivery Involve Certified Quality Products? An Innovative Case Study during the SARS-CoV-2 Pandemic in Italy,” Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research, vol. 18, no. 4, pp. 1687–1699, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- H. Makhluf, H. Madany, and K. Kim, “Long COVID: Long-Term Impact of SARS-CoV2,” Diagnostics, vol. 14, no. 7. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute (MDPI), Apr. 01, 2024. [CrossRef]

- G. Di Martino et al., “Change in Caffeine Consumption after Pandemic (CCAP-Study) among University Students: A Cross-Sectional Study from Italy,” Nutrients, vol. 16, no. 8, p. 1131, Apr. 2024. [CrossRef]

- R. M. Gogonea, L. C. Moraru, D. A. Bodislav, L. M. Păunescu, and C. F. Vlăsceanu, “Similarities and Disparities of e-Commerce in the European Union in the Post-Pandemic Period,” Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research, vol. 19, no. 1, pp. 340–361, Mar. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Y. Yang, H. Chen, and H. Liang, “Did New Retail Enhance Enterprise Competition during the COVID-19 Pandemic? An Empirical Analysis of Operating Efficiency,” Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research, vol. 18, no. 1, pp. 352–371, Mar. 2023. [CrossRef]

- L. Van Hove, “Evolution of the Online Grocery-Shopping Experience during the COVID-19 Pandemic: An Empiric Study from Portugal. Comment on Gomes, S.; Lopes, J.M. Evolution of the Online Grocery Shopping Experience during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Empiric Study from Portugal. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2022, 17, 909–923,” Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research, vol. 18, no. 4. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute (MDPI), pp. 1797–1798, Dec. 01, 2023. [CrossRef]

- “Advice on the use of masks in the context of COVID-19 - Interim guidance (5 June 2020) - World | ReliefWeb.” Accessed: Apr. 10, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://reliefweb.int/report/world/advice-use-masks-context-covid-19-interim-guidance-5-june-2020.

- “Mask use in the context of COVID-19”, Accessed: Apr. 15, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.ashrae.org/technical-resources/resources.

- M. Gandhi, C. Beyrer, and E. Goosby, “Masks Do More Than Protect Others During COVID-19: Reducing the Inoculum of SARS-CoV-2 to Protect the Wearer,” J Gen Intern Med, vol. 35, no. 10, pp. 3063–3066, Oct. 2020. [CrossRef]

- T. Makowiec-Dąbrowska, E. Gadzicka, and A. Bortkiewicz, “[Physiological cost of wearing protective masks - a narrative review of the literature],” Med Pr, vol. 72, no. 5, pp. 569–589, Nov. 2021. [CrossRef]

- B. N. J. Persson, “Side-leakage of face mask,” Eur Phys J E Soft Matter, vol. 44, no. 6, Jun. 2021. [CrossRef]

- E. O’Kelly, A. Arora, S. Pirog, J. Ward, and P. J. Clarkson, “Comparing the fit of N95, KN95, surgical, and cloth face masks and assessing the accuracy of fit checking,” PLoS One, vol. 16, no. 1, Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- D. J and W. RW, “Recent Advancements in Temporomandibular Disorders (TMDs),” Rev Pain, vol. 5, no. 1, pp. 18–25, Mar. 2011. [CrossRef]

- L. Reik and M. Hale, “The temporomandibular joint pain-dysfunction syndrome: a frequent cause of headache,” Headache, vol. 21, no. 4, pp. 151–156, 1981. [CrossRef]

- F. Liu and A. Steinkeler, “Epidemiology, diagnosis, and treatment of temporomandibular disorders,” Dent Clin North Am, vol. 57, no. 3, pp. 465–479, 2013. [CrossRef]

- M. P. Warren and J. L. Fried, “Temporomandibular disorders and hormones in women,” Cells Tissues Organs, vol. 169, no. 3, pp. 187–192, 2001. [CrossRef]

- M. T. John, S. F. Dworkin, and L. A. Mancl, “Reliability of clinical temporomandibular disorder diagnoses,” Pain, vol. 118, no. 1–2, pp. 61–69, Nov. 2005. [CrossRef]

- Sójka, J. Pilarski, and W. Hędzelek, “Opis metodyki badania klinicznego pacjentów z zaburzeniami stawów skroniowo-żuchwowych według klasyfikacji DC/TMD,” Dental Forum, vol. 45, no. 2, pp. 45–48, Aug. 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. Chowdhury et al., “Prevalence of dermatological, oral and neurological problems due to face mask use during COVID-19 and its associated factors among the health care workers of Bangladesh,” PLoS One, vol. 17, no. 4 April, Apr. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Falodun, N. Medugu, L. Sabir, I. Jibril, N. Oyakhire, and A. Adekeye, “An epidemiological study on face masks and acne in a Nigerian population,” PLoS One, vol. 17, no. 5 May, May 2022. [CrossRef]

- J. C. Szepietowski, Ł. Matusiak, M. Szepietowska, P. K. Krajewski, and R. Białynicki-Birula, “Face mask-induced itch: A self-questionnaire study of 2,315 responders during the COVID-19 pandemic,” Acta Derm Venereol, vol. 100, no. 10, pp. 1–5, May 2020. [CrossRef]

- N. M. Alreshidi et al., “The Association between Using Personal Protective Equipment and Headache among Healthcare Workers in Saudi Arabia Hospitals during the COVID-19 Pandemic,” Nursing Reports 2021, Vol. 11, Pages 568-583, vol. 11, no. 3, pp. 568–583, Jul. 2021. [CrossRef]

- E. C. H. Lim, R. C. S. Seet, K. H. Lee, E. P. V. Wilder-Smith, B. Y. S. Chuah, and B. K. C. Ong, “Headaches and the N95 face-mask amongst healthcare providers,” Acta Neurol Scand, vol. 113, no. 3, pp. 199–202, Mar. 2006. [CrossRef]

- J. J. Ong et al., “Headaches Associated With Personal Protective Equipment – A Cross-Sectional Study Among Frontline Healthcare Workers During COVID-19,” Headache: The Journal of Head and Face Pain, vol. 60, no. 5, pp. 864–877, May 2020. [CrossRef]

- “Association of Face Mask Use With Nasal Symptoms And Mucociliary Clearance”. [CrossRef]

- S. İpek, S. Yurttutan, U. U. Güllü, T. Dalkıran, C. Acıpayam, and A. Doğaner, “Is N95 face mask linked to dizziness and headache?,” Int Arch Occup Environ Health, vol. 94, no. 7, pp. 1627–1636, Oct. 2021. [CrossRef]

- D. G. Nwosu, E. N. Ossai, O. Onwuasoigwe, and F. Ahaotu, “Oxygen saturation and perceived discomfort with face mask types, in the era of covid-19: A hospital-based cross-sectional study,” Pan African Medical Journal, vol. 39, May 2021. [CrossRef]

- L. Padua et al., “Discomfort and Pain Related to Protective Mask-Wearing during COVID-19 Pandemic,” J Pers Med, vol. 12, no. 9, p. 1443, Sep. 2022. [CrossRef]

- K. O. Alfarouk et al., “Pathogenesis and management of COVID-19,” Journal of Xenobiotics, vol. 11, no. 2. MDPI, pp. 77–93, Jun. 01, 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. J. Grant and A. Booth, “A typology of reviews: An analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies,” Health Information and Libraries Journal, vol. 26, no. 2. pp. 91–108, Jun. 2009. [CrossRef]

- M. Zuhour, M. Ismayilzade, M. Dadacl, and B. Ince, “The Impact of Wearing a Face Mask during the COVID-19 Pandemic on Temporomandibular Joint: A Radiological and Questionnaire Assessment,” Indian Journal of Plastic Surgery, vol. 55, no. 1, pp. 58–65, Feb. 2022. [CrossRef]

- E. Marques-Sule, G. V. Espí-López, L. Monzani, L. Suso-Martí, M. C. Rel, and A. Arnal-Gómez, “How does the continued use of the mask affect the craniofacial region? A cross-sectional study,” Brain Behav, vol. 13, no. 7, Jul. 2023. [CrossRef]

- F. d’Apuzzo, R. P. Rotolo, L. Nucci, V. Simeon, G. Minervini, and V. Grassia, “Protective masks during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic: Any relationship with temporomandibular disorders and orofacial pain?,” J Oral Rehabil, vol. 50, no. 9, pp. 767–774, Sep. 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. Çarikci, Y. Ateş Sari, E. N. Özcan, S. S. Baş, K. Tuz, and N. Ö. Ünlüer, “An Investigation of temporomandibular pain, headache, and fatigue in relation with long-term mask use during the COVID-19 pandemic period,” Cranio - Journal of Craniomandibular and Sleep Practice, 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Roy et al., “Prevalence of dermatological manifestations due to face mask use and its associated factors during COVID-19 among the general population of Bangladesh: A nationwide cross-sectional survey,” PLoS One, vol. 17, no. 6 June, Jun. 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Algaadi, Y. A Almulhim, Y. Y Alobaysi, A. Alosaimi, and M. S Alshehri, “Effects of the face mask on the skin during the COVID-19 pandemic in Saudi Arabia,” Advances in Human Biology, vol. 12, no. 3, p. 292, 2022. [CrossRef]

- C. Han, J. Shi, Y. Chen, and Z. Zhang, “Increased flare of acne caused by long-time mask wearing during COVID-19 pandemic among general population,” Dermatologic Therapy, vol. 33, no. 4. Blackwell Publishing Inc., Jul. 01, 2020. [CrossRef]

- R. Karki, A. Lamicchane, and A. Timsina, “Effects of Prolonged Use of Face Masks among Healthcare Workers Working in a Tertiary level Hospital in Kathmandu, Nepal.,” Indian J Public Health Res Dev, vol. 13, no. 3, pp. 233–237, Jul. 2022, [Online]. Available: https://widgets.ebscohost.com/prod/customlink/hanapi/hanapi.php?profile=4dfs1q6ik%2BHE5pTW2pLu0O%2BU2dfZp9PkldzU0trT4ZLZ19el19C%2Bx6fZ0JburqyqpsXVyZKg&DestinationURL=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edb&AN=158945928&lang=pl&site=eds-live.

- Kua, S. Richmond, and D. J. Farnell, “Initial evidence that skin health deteriorates for younger age groups and with increased daily use of face masks for healthcare professionals at a dental hospital in the United Kingdom,” J Dent, vol. 141, Feb. 2024. [CrossRef]

- P. K. Krajewski, Ł. Matusiak, M. Szepietowska, R. Białynicki-Birula, and J. C. Szepietowski, “Increased prevalence of face mask—induced itch in health care workers,” Biology (Basel), vol. 9, no. 12, pp. 1–10, Dec. 2020. [CrossRef]

- S. Cretu, M. Dascalu, and C. M. Salavastru, “Acne care in health care providers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A national survey,” Dermatol Ther, vol. 35, no. 10, Oct. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Yoshihara, E. E. Dierickx, G. J. Brewer, Y. Sekiguchi, R. L. Stearns, and D. J. Casa, “Effects of Face Mask Use on Objective and Subjective Measures of Thermoregulation During Exercise in the Heat,” Sports Health, vol. 13, no. 5, pp. 463–470, Sep. 2021. [CrossRef]

- N. Radhakrishnan, S. S. Sudarsan, K. Deepak Raj, and S. Krishnamoorthy, “Clinical Audit on Symptomatology of Covid-19 Healthcare Workers and Impact on Quality-of-Life (QOL) Due to Continuous Facemask Usage: A Prospective Study,” Indian Journal of Otolaryngology and Head and Neck Surgery, vol. 73, no. 4, pp. 486–493, Dec. 2021. [CrossRef]

- W. Hua et al., “Short-term skin reactions following use of N95 respirators and medical masks,” Contact Dermatitis, vol. 83, no. 2, pp. 115–121, Aug. 2020. [CrossRef]

- C. B. Spigariolo, S. Giacalone, and G. Nazzaro, “Maskne: The Epidemic within the Pandemic: From Diagnosis to Therapy,” Journal of Clinical Medicine, vol. 11, no. 3. MDPI, Feb. 01, 2022. [CrossRef]

- K. Priya, P. N. A. Vaishali, S. Rajasekaran, D. Balaji, and R. B. N. Navin, “Assessment of Effects on Prolonged Usage of Face Mask by ENT Professionals During Covid-19 Pandemic,” Indian Journal of Otolaryngology and Head and Neck Surgery, vol. 74, pp. 3173–3177, Oct. 2022. [CrossRef]

- N. W. Sheng Chew et al., “Association of face mask use with self-reported cardiovascular symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic,” Singapore Med J, vol. 64, no. 10, pp. 609–615, Oct. 2023. [CrossRef]

- R. Mohamed Hussein et al., “Compliance and Side effects of face mask use in medical team managing COVID-19: A cross-sectional survey in a tertiary care hospital,” Egypt J Chest Dis Tuberc, vol. 73, no. 1, pp. 108–113, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Moumneh, P. E. L. Kofoed, and S. V. Vahlkvist, “Face mask use during the COVID-19 pandemic was associated with breathing difficulties in adolescent patients with asthma,” Acta Paediatrica, International Journal of Paediatrics, vol. 112, no. 8, pp. 1740–1746, Aug. 2023. [CrossRef]

- G. Giannaccare, M. Pellegrini, M. Borselli, C. Senni, A. Bruno, and V. Scorcia, “Diurnal changes of noninvasive parameters of ocular surface in healthy subjects before and after continuous face mask wearing during the COVID-19 pandemic,” Sci Rep, vol. 12, no. 1, Dec. 2022. [CrossRef]

- R. A. Alsulami et al., “Effects of Face-Mask Use on Dry Eye Disease Evaluated Using Self-Reported Ocular Surface Disease Index Scores: A Cross-Sectional Study on Nurses in Saudi Arabia,” Cureus, Dec. 2022. [CrossRef]

- L. Boccardo, “Self-reported symptoms of mask-associated dry eye: A survey study of 3,605 people,” Contact Lens and Anterior Eye, vol. 45, no. 2, Apr. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Ö. Dikmetaş, H. Toprak Tellioğlu, İ. Özturan, S. Kocabeyoğlu, A. B. Çankaya, and M. İrkeç, “The Effect of Mask Use on the Ocular Surface During the COVID-19 Pandemic,” Turk J Ophthalmol, vol. 53, no. 2, pp. 74–78, Apr. 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. L. Young, M. L. Smith, and A. J. Tatham, “Visual field artifacts from face mask use,” J Glaucoma, vol. 29, no. 10, pp. 989–991, Oct. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Y. F. Tang and E. W. T. Chong, “Face Mask–Associated Recurrent Corneal Erosion Syndrome and Corneal Infection,” Eye Contact Lens, vol. 47, no. 10, 2021, [Online]. Available: https://journals.lww.com/claojournal/fulltext/2021/10000/face_mask_associated_recurrent_corneal_erosion.8.aspx.

- E. Lee, K. Cormier, and A. Sharma, “Face mask use in healthcare settings: effects on communication, cognition, listening effort and strategies for amelioration,” Cogn Res Princ Implic, vol. 7, no. 1, Dec. 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Benítez-Robaina, Á. Ramos-Macias, S. Borkoski-Barreiro, J. C. Falcón-González, P. Salvatierra, and Á. R. De Miguel, “COVID-19 era: Hearing handicaps behind face mask use in hearing aid users,” Journal of International Advanced Otology, vol. 18, no. 6, pp. 465–470, Nov. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Sizer et al., “THE EFFECTS OF FACE MASK USE DURING COVID-19 ON SPEECH COMPREHENSION IN GERIATRIC PATIENTS WITH HEARING LOSS WHO USE LIP-READING FOR COMMUNICATION: A PROSPECTIVE CROSS-SECTIONAL STUDY,” Turk Geriatri Derg, vol. 25, no. 2, pp. 274–281, 2022. [CrossRef]

- K. Dalrymple, J. Gomez, and B. Duchaine, “CFMT-Kids: A new test of face memory for children,” J Vis, vol. 12, no. 9, p. 492, Aug. 2012. [CrossRef]

- Stajduhar, T. Ganel, G. Avidan, R. S. Rosenbaum, and E. Freud, “Face masks disrupt holistic processing and face perception in school-age children,” Cogn Res Princ Implic, vol. 7, no. 1, Dec. 2022. [CrossRef]

- N. Ozamiz-Etxbarria, M. Picaza, E. Jiménez-Etxebarria, and J. H. D. Cornelius-White, “Back to School in the Pandemic: Observations of the Influences of Prevention Measures on Relationships, Autonomy, and Learning of Preschool Children,” COVID, vol. 2, no. 5, pp. 633–641, May 2022. [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhang et al., “Effect of Surgical Masks and N95 Respirators on Anxiety,” Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat, vol. 20, pp. 551–559, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Cigiloglu, E. Ozturk, S. Ganidagli, and Z. A. Ozturk, “Different reflections of the face mask: sleepiness, headache and psychological symptoms,” International Journal of Occupational Safety and Ergonomics, vol. 28, no. 4, pp. 2278–2283, Oct. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Mirhashemi, M. R. Khami, M. Kharazifard, and R. Bahrami, “The Evaluation of the Relationship Between Oral Habits Prevalence and COVID-19 Pandemic in Adults and Adolescents: A Systematic Review,” Frontiers in Public Health, vol. 10. Frontiers Media S.A., Mar. 04, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Emodi-Perlman and I. Eli, “One year into the covid-19 pandemic – temporomandibular disorders and bruxism: What we have learned and what we can do to improve our manner of treatment,” Dental and Medical Problems, vol. 58, no. 2. Wroclaw University of Medicine, pp. 215–218, Apr. 01, 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. Ginszt et al., “The Effects of Wearing a Medical Mask on the Masticatory and Neck Muscle Activity in Healthy Young Women,” J Clin Med, vol. 11, no. 2, Jan. 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Ginszt et al., “The Difference in Electromyographic Activity While Wearing a Medical Mask in Women with and without Temporomandibular Disorders,” Int J Environ Res Public Health, vol. 19, no. 23, Dec. 2022. [CrossRef]

- W. Florjanski et al., “Evaluation of biofeedback usefulness in masticatory muscle activity management—a systematic review,” J Clin Med, vol. 8, no. 6, Jun. 2019. [CrossRef]

- R. M. Kwasnicki, J. T. Super, P. Ramaraj, L. Savine, and S. P. Hettiaratchy, “FFP3 Feelings and Clinical Experience (FaCE). Facial pressure injuries in healthcare workers from FFP3 masks during the COVID-19 pandemic,” Journal of Plastic, Reconstructive and Aesthetic Surgery, vol. 75, no. 9, pp. 3622–3627, Sep. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Freeman et al., “Do They Really Work? Quantifying Fabric Mask Effectiveness to Improve Public Health Messaging,” Int J Environ Res Public Health, vol. 19, no. 11, Jun. 2022. [CrossRef]

- H. Whiley, T. P. Keerthirathne, M. A. Nisar, M. A. F. White, and K. E. Ross, “Viral filtration efficiency of fabric masks compared with surgical and n95 masks,” Pathogens, vol. 9, no. 9, pp. 1–8, Sep. 2020. [CrossRef]

- G. S. Selwyn, C. Ye, and S. B. Bradfute, “Anti-sars-cov-2 activity of surgical masks infused with quaternary ammonium salts,” Viruses, vol. 13, no. 6, Jun. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Y. Bao, L. Anderegg, S. Burchesky, and J. M. Doyle, “Device for Suppression of Aerosol Transfer in Close Proximity Settings,” COVID, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 394–402, Sep. 2021. [CrossRef]

- W. Group, “Measuring quality of life,” Geneva: The World Health Organization, pp. 1–13, 1997.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).