1. Introduction

Artificial Intelligence (AI) has a rich history that predates its recent surge in popularity. The concept of machines mimicking human intelligence has been explored for several decades, with early AI developments laying the foundation for the transformative technologies we encounter today. Despite its existence for quite some time, the true extent of AI's potential became more apparent in recent years, especially with the advent of groundbreaking models like ChatGPT [

1]. The launch of ChatGPT marked a paradigm shift in the world of AI.

The introduction of ChatGPT represented a significant transformation in the realm of artificial intelligence. OpenAI's development of ChatGPT revolutionised natural language processing, captivating a broad audience and propelling AI into the mainstream [

2]. The AI's conversational abilities, which are easy to use and understand, have not only increased accessibility but also generated a significant increase in interest and usage. The broad acknowledgment of ChatGPT served as a stimulant for the advancement and release of several AI applications, fundamentally altering the technological environment.

Libraries, like all other organisations in the digital age, are affected by the revolutionary impact of Artificial Intelligence (AI) [

3,

4,

5]. Advancements in technology have caused libraries to reevaluate their conventional functions and adopt inventive approaches [

6,

7]. Consequently, numerous libraries have encountered the significant influence of AI on their services and operations. The impact of AI on libraries is not just theoretical but also tangible, as libraries are actively striving to incorporate AI seamlessly into their daily operations [

8,

9,

10].

Libraries serve as multifaceted establishments with several functions, one of which is to encourage learning experiences, cultivate lifelong learning, and enhance digital literacy [

11,

12]. Libraries, traditionally seen as places where knowledge is stored, have transformed into dynamic environments that actively contribute to the educational progress of its visitors [

13]. The incorporation of Artificial Intelligence (AI) acts as a revolutionary instrument for libraries, enhancing their capacities to complete these vital functions. Libraries may significantly enhance learning experiences by implementing appropriate AI technologies. According to Masrek et al. [

14], libraries enhance the learning experience of its users by offering a technologically advanced environment that supports lifelong learning and strengthens digital literacy programmes.

Currently, the use and integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in Malaysia and Indonesia are at an early stage, especially in the context of libraries. Libraries in various countries, including academic, public, and specialised ones, have not fully integrated AI into their operations. Although generative AI, like ChatGPT, has been utilised in Malaysian and Indonesian libraries to some extent, its extensive implementation is still restricted. The early phase of AI implementation in these libraries provides a favourable opportunity to comprehend the viewpoints and attitudes of librarians on the role of AI in important domains such as increasing learning experiences, promoting lifelong learning, and enhancing digital literacy.

Due to the limited utilization of AI in the realms of learning experiences, lifelong learning, and digital literacy, there exists a noticeable gap in understanding how libraries perceive the potential benefits of AI in these areas. This study aims to fill this void by employing two research objectives. Firstly, the investigation aims to measure librarian perspectives on the support provided by AI in enhancing learning experiences, fostering lifelong learning, and advancing digital literacy initiatives. Secondly, it seeks to compare these perspectives between Malaysia and Indonesia. Gaining insight into these perspectives is crucial for making informed decisions, formulating strategic plans, and successfully integrating AI technologies into library services. By examining the viewpoints of libraries, this research endeavors to provide valuable insights that can guide future initiatives, influence policy decisions, and contribute to the broader discourse on the role of artificial intelligence in library services, particularly within the distinct settings of Malaysia and Indonesia.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Overview of Artificial Intelligence (AI)

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is the replication of human intellect in computers, which are programmed to possess the ability to think, learn, and carry out tasks that usually necessitate human intelligence [

15]. The concept of AI has a long and extensive history, tracing its origins to ancient times when myths and narratives delved into the notion of constructing artificial entities possessing human-like skills [

16]. Nonetheless, it was not until the mid-20th century that AI genuinely commenced to materialise as a discipline of investigation. Throughout its development, AI has progressed through different stages, starting with rule-based systems and expert systems and advancing to machine learning and deep learning methods [

17]. The progress of AI has been characterised by notable advancements, like the creation of neural networks [

18] and the emergence of big data [

19], which have played a crucial role in changing the technological environment.

AI can be classified into two main categories: narrow or weak AI, which is designed to perform certain tasks, and general or strong AI, which has cognitive capacities like humans [

20,

21]. Presently, narrow artificial intelligence (AI) is widely used in several applications, including virtual personal assistants, picture and speech recognition, and recommendation systems [

22]. AI is being progressively employed in the business sector to improve efficiency and decision-making [

23]. Libraries are integrating artificial intelligence (AI) into their operations. The study conducted by Masrek et al. [

14] found that by streamlining cataloguing operations, automating book recommendations, and enhancing user experiences, significant improvements can be achieved. Artificial intelligence (AI) systems have the capability to analyse large volumes of data to detect trends, which can assist libraries in optimising their collections and services [

4,

24]. The incorporation of artificial intelligence (AI) into corporate operations emphasises its profound influence on many sectors, providing inventive resolutions and unveiling fresh opportunities for enhanced productivity and expansion.

2.2. Artificial Intelligence in Libraries

Extensive research has been conducted on the incorporation of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in libraries, indicating a rising interest in utilising sophisticated technologies to improve library services and operations. The research can be classified into many categories, providing insights into different aspects of AI deployment in library contexts. A prominent category consists of review and opinion papers that explore the possible advantages of AI for libraries [

3,

4,

5]. Researchers and scholars investigate the potential of AI to transform information retrieval, automate monotonous jobs, and provide tailored recommendations, ultimately enhancing the overall effectiveness of library services. Previous research has also explored the extent to which libraries are prepared to adopt artificial intelligence (AI) technology [

6,

7]. These investigations evaluate the readiness of libraries in terms of their organisation and structure to implement AI technologies. They assess the viability of incorporating AI into library operations by examining elements such as infrastructure, staff training, and institutional support [

25,

26]. Comprehending the preparedness of libraries is essential for developing effective methods and frameworks to deploy AI efficiently.

Further classification of research examines the practical implementation of artificial intelligence in libraries or by librarians [

8,

9,

10]. The research in this field explores the degree to which AI technologies have been integrated into library workflows. It examines the difficulties encountered throughout the implementation process and the effects on user experiences. These studies provide essential knowledge about the practical implementation of AI in libraries, offering practical advice for individuals who are considering or currently undertaking the adoption process. Finally, a prominent issue in the literature revolves around the advancement of AI applications that are specifically tailored to assist and enhance library services and operations. This research focus on developing and applying AI-powered tools and systems specifically designed to meet the specific requirements of libraries. Illustrative instances encompass AI-driven categorization systems [

27], recommendation engines for library resources [

28], and intelligent chatbots designed to aid patrons [

29]. Gaining insight into the evolution of these applications offers a strategic plan for libraries aiming to leverage the potential of artificial intelligence to improve their services and offer a more enhanced user experience [

30]. Collectively, the wide range of research on artificial intelligence (AI) in libraries demonstrates a constantly changing subject that is propelled by the quest for inventive solutions and the improvement of library operations.

2.3. Learning Experience

The term "learning experience" refers to the whole effect of educational interactions on an individual's intellectual growth, abilities, and personal advancement. This includes both structured and unstructured components [

31,

32]. It considers multiple factors, including the learning environment, interpersonal interactions, and the incorporation of technology. It goes beyond traditional classrooms to prioritise critical thinking, problem-solving, and the acquisition of practical skills applicable to real-life situations [

33,

34].

Technological improvements and evolving educational techniques have had a significant impact on the evolution of learning experiences [

35]. Conventional approaches such as lectures and textbooks have shifted towards interactive and immersive learning methods [

36]. The availability of digital resources, online courses, and interactive platforms has made knowledge more accessible to a wider audience, enabling learners to interact with educational content in dynamic and personalised ways [

37]. With the ongoing evolution of the learning environment, there is an increasing acknowledgment of the significance of adaptive learning experiences that are customised to meet individual requirements and preferences [

38].

Libraries have a crucial role in enhancing patrons' learning experiences by functioning as vibrant centres that provide a wide array of resources and support services. In addition to granting access to a vast array of books and scholarly materials, contemporary libraries utilise technology to provide digital resources, online courses, and collaborative spaces that foster interactive learning [

39,

40]. Librarians serve as mentors, aiding patrons in interpreting information and cultivating an atmosphere that promotes ongoing learning, adaptation to emerging technology, and skill development [

41].

The infusion of Artificial Intelligence (AI) into library services promises to revolutionize the learning experiences of users by providing personalized [

42], adaptive, and efficient pathways to knowledge. AI algorithms can analyze user preferences, behavior, and past interactions to offer tailored recommendations [

43], ensuring that library users access resources aligned with their unique needs and interests [

44,

45]. Through intelligent content curation, AI enhances the relevancy and diversity of materials available, making the learning journey more engaging and comprehensive [

42,

46]. Additionally, AI-driven virtual assistants can assist users in real-time, answering queries, offering guidance, and facilitating a more interactive and dynamic learning environment [

47,

48]. By harnessing the power of AI, libraries can transform traditional information retrieval into a more user-centric [

49,

50], efficient, and enriching learning experience for individuals of diverse backgrounds and learning styles [

51].

2.4. Lifelong Learning

Lifelong learning encompasses the continuous, voluntary, and self-driven endeavour to acquire information and enhance personal growth over one's entire life [

52,

53]. It includes a wide range of formal and informal learning opportunities that go beyond standard educational limits. The notion of lifelong learning acknowledges that the acquisition of skills and information is not confined to a particular stage of life or a formal educational environment, but rather is an ongoing and flexible process that adjusts to evolving demands and circumstances [

54,

55].

The progression of lifelong learning has been characterised by a transition from a primarily rigid and institution-centered framework to a more adaptable and learner-focused approach [

56]. Historically, educational systems followed a structured progression, including primary, secondary, and postsecondary education, with a focus mostly on formal schooling and less emphasis on lifelong learning [

57]. On the other hand, modern methods of lifelong learning adopt a comprehensive perspective that recognises the significance of informal learning, acquiring skills, and personal growth at any point in one's life [

58]. The progress in technology has had a substantial impact on this development, offering convenient platforms for online courses, virtual communities, and digital resources that allow people of any age or place to participate in learning activities [

59].

Contemporary libraries utilise technology to provide a wide array of resources, such as e-books, online courses, and digital archives, thereby improving the availability of educational materials. Librarians, in this situation, function as knowledgeable individuals who help and enable library users to navigate the vast amount of information accessible to them, while also helping in their pursuit of further education. By adopting this position, libraries actively contribute to cultivating a culture of continuous learning within their communities, supporting cognitive development and individual enrichment throughout people's lifetimes.

The integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in libraries serves as a catalyst for promoting lifelong learning by offering personalized and adaptive educational experiences [

60]. AI-driven systems can analyze users' preferences, learning styles, and past interactions to tailor content recommendations, ensuring that individuals receive relevant and engaging resources [

61,

62]. Additionally, AI-powered virtual assistants and chatbots provide immediate and interactive support [

63,

64], guiding patrons through information searches, facilitating comprehension, and encouraging continuous exploration. By harnessing AI technologies, libraries not only enhance accessibility to diverse learning materials but also cultivate a dynamic learning environment that adapts to the evolving needs and interests of lifelong learners, fostering a culture of continuous knowledge acquisition [

65,

66].

2.5. Digital Literacy

Digital literacy encompasses the proficiency to efficiently access, understand, evaluate, and use information in various digital formats [

67,

68]. It includes a variety of proficiencies, ranging from fundamental tasks like navigating digital interfaces to more complex skills like critically assessing online content and safeguarding oneself in the digital realm [

69]. In an ever-changing technology environment, possessing digital literacy is crucial for individuals to actively engage in society, safely interact with information, and effectively manage the intricacies of the digital realm.

There is a substantial convergence between digital literacy and information literacy, since both encompass the capacity to proficiently find, assess, and utilise information [

70]. knowledge literacy usually emphasises the acquisition and utilisation of knowledge from many sources, encompassing both print and digital mediums. Digital literacy encompasses the proficiency required to navigate and operate in the digital domain, including competencies in areas such as online privacy comprehension, digital interface navigation, and critical evaluation of the credibility of digital information [

71]. Essentially, digital literacy is a component of information literacy that focuses on being skilled in the digital environment.

Libraries are crucial in promoting the digital literacy of their users through providing access to digital resources, offering training sessions, and serving as guides in the online domain. They actively engage in promoting awareness and cultivating proficiency in using digital tools and platforms, empowering individuals to effectively connect with information offered in many digital media. Librarians, who are skilled in information and digital literacy, assist patrons in developing their critical thinking skills to assess online content and equip them to confidently use digital technology. Despite the continuous advancement of technology, libraries remain in the forefront in promoting digital literacy, guaranteeing that individuals may thrive in the digital age.

The implementation of AI in library services holds the potential to significantly promote and enhance users' digital literacy [

72,

73,

74]. AI technologies can play a pivotal role in guiding patrons through the ever-expanding digital landscape, helping them navigate online resources, evaluate information credibility [

75], and develop critical thinking skills [

76]. By leveraging AI-driven tools for information retrieval and analysis, librarians can empower users to sift through vast amounts of data efficiently and discern relevant, reliable sources [

77]. Furthermore, personalized learning pathways [

78], generated by AI algorithms, can cater to individual skill levels and preferences, fostering a targeted approach to digital literacy education. In essence, AI integration in library services not only augments traditional information access but also actively contributes to equipping users with the necessary skills to navigate and thrive in the digital era.

2.6. Theoretical Framework and Hypothesis Development

Malaysia and Indonesia have a distinct and interrelated connection as neighbouring countries with a shared ethnic and linguistic past. The historical connections and cultural affinities among these nations have fostered a collective sense of identity and comprehension. In addition to their close geographical closeness, both states are part of the broader Malay archipelago, which cultivates a strong sense of kinship between them. The common legacy between Malaysia and Indonesia not only affects cultural traditions but also has an impact on diplomatic, economic, and social contacts between the two countries. The historical and cultural connection between these nations forms the basis for collaboration, cooperation, and mutual respect, resulting in a diverse collection of shared experiences and values.

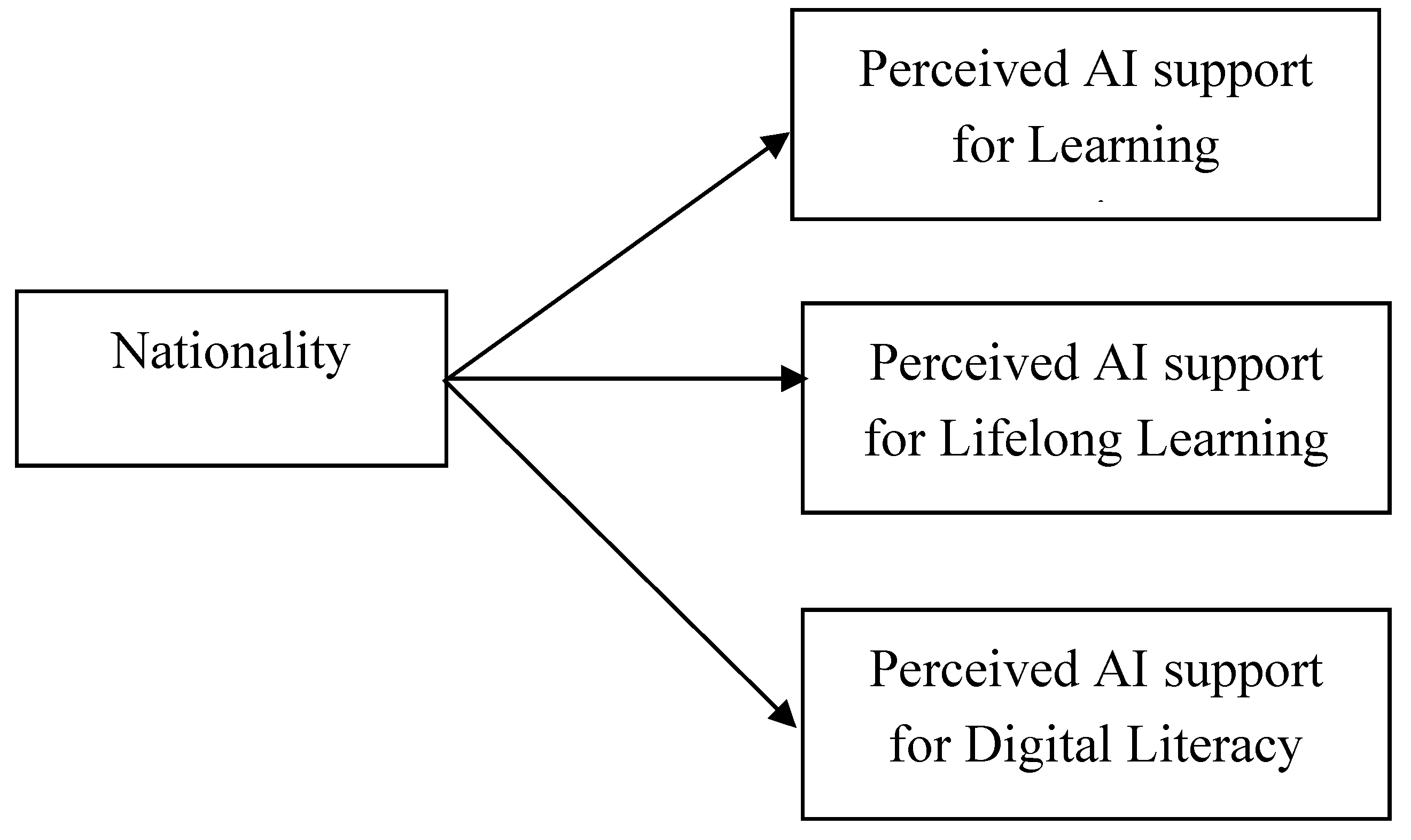

Figure 1 shows the theoretical framework of the study. Perceived AI support for the learning experience, as evaluated by librarians, encompasses their subjective judgments regarding the impact of AI tools on personalized learning, deep engagement, feedback improvement, timely content delivery, enhanced accessibility, and the cultivation of autonomy and self-directed learning among library users. Perceived AI support for lifelong learning, as assessed by librarians, encompasses their subjective judgments regarding the impact of AI tools on the motivation, autonomy, exploration, community engagement, adaptability, and continuous improvement of library users within the context of lifelong learning. perceived AI support for digital literacy, as evaluated by librarians, encompasses their subjective judgments regarding the impact of AI tools on information literacy, digital media comprehension, critical evaluation of online information, digital tools utilization, digital communication skills, and the promotion of awareness around online privacy and security among library users.

Numerous comparative studies scrutinizing Malaysia and Indonesia have unveiled notably congruent findings. A study by Puspitasari, Manan, and Anna [

79] underscored the sustained collaboration between library ecosystems in Malaysia and Indonesia, spanning diverse dimensions, including training programs, material borrowing procedures, and other scholarly pursuits. This collective endeavor has, to a certain degree, contributed to a shared impact, fostering the advancement and evolution of their respective libraries. Another investigation led by Rahmandita [

80] delved into the scrutiny of library websites in Indonesia and Malaysia. Employing a survey methodology with data collected from respondents in both nations, the study discerned an absence of significant distinctions in students' experiences when engaging with digital university library websites, irrespective of institutional affiliation (public or private). Adding to the scholarly discourse, the study by Rusydiyah, Zaini Tamin, and Rahman [

81] centered on literacy policies across Malaysia, Indonesia, and Singapore. Their findings revealed a noteworthy commonality in the factors influencing the implementation of literacy initiatives. Notably, Singapore, Malaysia, and Indonesia all relied on specialized literacy institutions to execute and uphold their respective literacy policies. Based on the discussion, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H0a: There is no significant difference in the perception of AI support for learning experiences between Malaysia and Indonesia.

H0b: There is no significant difference in the perception of AI support for lifelong learning between Malaysia and Indonesia.

H0c: There is no significant difference in the perception of AI support for digital literacy between Malaysia and Indonesia.

3. Research Methodology and Results

This study employed a survey research methodology to delve into the perceived impact of artificial intelligence (AI) on learning experiences, lifelong learning, and digital literacy within the context of library environments. The primary data collection instrument was a meticulously crafted questionnaire, initially developed by the researcher and subsequently refined through testing with seven academics and three librarians. The survey, consisting of six questions and employing a five-point Likert scale, aimed to gain a nuanced understanding of librarians' perspectives on AI assistance. The robustness of the developed questionnaire was confirmed by Cronbach Alpha scores exceeding 0.9 for each of the three constructs, as detailed in Tables 2, 3 and 4, attesting to its high reliability.

Data were collected through an online platform, ensuring accessibility and efficiency during the approximately month-long data gathering process. The study specifically focused on organizational analysis, with libraries as the primary unit of scrutiny. To ensure representativeness, responses were sought from individual libraries through selected representatives. The target population encompassed all public libraries, specialized libraries, university and college libraries, and school libraries. However, due to the absence of a valid sampling frame, libraries were identified from their respective websites. In Malaysia, outreach efforts were extended to 320 libraries, while in Indonesia, 400 libraries were contacted. Subsequently, 59 responses were garnered from Malaysia and 85 from Indonesia after the one-month data collection period. Given that the unit of analysis is organizations (i.e., libraries), the relatively low response rate is deemed acceptable.

Following data collection, a rigorous analysis was conducted utilizing the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 24. This comprehensive statistical analysis facilitated an in-depth investigation into the perceptions and insights gathered from librarians. The study employed both descriptive and inferential statistics. Descriptive statistics included frequency analysis for demographic data and mean scores with standard deviations for the three constructs. Additionally, independent sample t-tests were utilized to assess the three developed hypotheses, contributing to a robust examination of the intricate dynamics surrounding the influence of AI in library settings.

3.1. Findings

Table 1 presents a thorough summary of the demographic characteristics of the individuals involved in the study. A total of 59 respondents from Malaysia and 85 respondents from Indonesia, representing libraries in their respective countries, actively engaged in the research. In Malaysia, there was a significant predominance of males, making up 52.5% of the respondents. Conversely, in Indonesia, females were the majority, accounting for 72.9%. Age-wise, most respondents from both Malaysia and Indonesia fell within the 40-49 age range. Further analysis of occupational roles indicated that heads of departments were predominant among Malaysian respondents, whereas senior librarians constituted the majority in Indonesia. In terms of library size, 66.1% of Malaysian respondents indicated that their libraries had a staff size exceeding 50, contrasting with Indonesia, where the majority reported a smaller scale, with 47.1% having less than 10 staff members.

Table 1.

Demographic Profiles of Respondents.

Table 1.

Demographic Profiles of Respondents.

| |

Malaysia (Total Respondent = 59) |

Indonesia (Total Respondent = 85) |

| |

Frequency |

Percent |

Frequency |

Percent |

| Gender |

Male |

31 |

52.5 |

23 |

27.1 |

| Female |

28 |

47.5 |

62 |

72.9 |

| Age |

20 - 29 year |

3 |

5.1 |

17 |

20.0 |

| 30 - 39 year |

22 |

37.3 |

11 |

12.9 |

| 40 - 49 year |

29 |

49.2 |

29 |

34.1 |

| 50 - 59 year |

5 |

8.5 |

27 |

31.8 |

| 60 - 69 year |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1.2 |

| Position |

Chief Librarian |

1 |

1.7 |

17 |

20.0 |

| Senior Librarian |

17 |

28.8 |

56 |

65.9 |

| Head of Unit / Department |

23 |

39.0 |

8 |

9.4 |

| Others |

18 |

30.5 |

4 |

4.7 |

| Library Size |

Small (fewer than 10 staff members) |

14 |

23.7 |

40 |

47.1 |

| Medium (10-50 staff members) |

6 |

10.2 |

28 |

32.9 |

| Large (more than 50 staff members) |

39 |

66.1 |

17 |

20.0 |

The findings reveal favorable mean scores for various aspects of AI support in learning experiences (

Table 2). Librarians perceive that AI tools provide significant backing for personalized learning experiences, with a mean score of 3.8644 (Malaysia) and 3.9294 (Indonesia), indicating a positive impact on tailoring education to individual needs. Additionally, AI is seen to enhance patrons' engagement with learning materials (mean score: 3.8136 for Malaysia and 3.9412 for Indonesia) and improve their understanding of concepts through AI-driven feedback mechanisms (mean score: 3.7627 for Malaysia and 3.8588 for Malaysia). The facilitation of timely and relevant content delivery to support patrons' learning goals also garnered positive feedback, with a mean score of 3.7797 and 3.9059 for Malaysia and Indonesia respectively. AI's role in enhancing the accessibility of learning resources for patrons with diverse needs received a commendable mean score of 3.8305 and 3.9059 for Malaysia and Indonesia respectively. Moreover, librarians perceive that AI tools contribute to fostering a sense of autonomy and self-directed learning among patrons, as indicated by a mean score of 3.7627 and 3.8235 for Malaysia and Indonesia respectively. The overall mean score of 3.8023 (Malaysia) and 3.8941 (Indonesia) suggests a generally positive assessment of AI's impact on learning experiences, with specific strengths in personalization, engagement, accessibility, and autonomy.

Comparing groups from Malaysia (M = 3.8023, SD = 0.85123) and Indonesia (M = 3.8941, SD = 0.53813) in terms of their learning experiences, an independent samples t-test yielded non-significant results (t(142) = -0.793, p = 0.429). Despite the lack of statistical significance, a moderate effect size (Cohen's d = 0.68357) indicated a noticeable difference between the groups. This leads to the acceptance of the null hypothesis (H0a), suggesting that there is no significant disparity in the perception of AI support for learning experiences between Malaysia and Indonesia. It's important to note that while the effect size is moderate and noteworthy, its practical significance in this context may be limited.

The findings demonstrate positive perceptions from librarians regarding the impact of AI tools on lifelong learning in both Malaysia and Indonesia (

Table 3). AI tools are perceived to significantly boost patrons' motivation for engaging in lifelong learning, with mean scores of 3.8644 in Malaysia and 3.9059 in Indonesia. Librarians also believe that AI empowers patrons to effectively self-direct their learning journeys, as reflected in mean scores of 3.8983 in Malaysia and 3.8824 in Indonesia. Additionally, AI tools are seen as effective in helping patrons discover and explore new areas of interest, with mean scores of 3.9661 in Malaysia and 3.9529 in Indonesia. While fostering a sense of community and collaboration among patrons yielded a slightly lower mean score in Malaysia (3.6610), librarians in Indonesia perceived a stronger impact (3.7647). Both countries indicated positive perceptions that AI tools continuously adapt to patrons' evolving learning needs over time, with mean scores of 3.8983 in Malaysia and 3.9647 in Indonesia. Finally, in terms of contributing to the continuous improvement of patrons' skills and knowledge, Malaysia and Indonesia reported mean scores of 3.7966 and 3.9529, respectively. The overall mean scores for lifelong learning are 3.8475 in Malaysia and 3.9039 in Indonesia, affirming a generally favorable view of AI tools in supporting patrons' lifelong learning journeys.

To examine the second hypothesis, an independent samples t-test was conducted to compare groups from Malaysia (M = 3.8475, SD = 0.84548) and Indonesia (M = 3.9039, SD = 0.51907) in terms of lifelong learning. The analysis revealed no statistically significant difference between the Malaysian and Indonesian groups (t(142) = -0.457, p = 0.325). Despite the absence of statistical significance, a moderate effect size was observed (Cohen's d = 0.67183). These results lead us to retain the null hypothesis (H0b), indicating that there is no significant difference in the perception of AI support for lifelong learning between Malaysia and Indonesia. The moderate effect size, while indicative of a noticeable difference, may not necessarily have practical implications in this context.

The findings indicate positive perceptions among librarians regarding the impact of AI tools on digital literacy, as assessed through a Likert scale, in both Malaysia and Indonesia (

Table 4). AI tools are perceived to effectively enhance patrons' information literacy skills, with mean scores of 3.8644 in Malaysia and 3.9294 in Indonesia. Librarians in both countries also believe that AI tools successfully improve patrons' comprehension of digital media content, as reflected by mean scores of 3.8644 in Malaysia and 3.9882 in Indonesia. The research Indicates that AI tools are essential in assisting users to assess and determine the reliability of online information. The statistics reveals that Malaysia has a mean score of 3.6102, whereas Indonesia has a slightly higher mean score of 3.7647. Furthermore, AI is acknowledged for greatly improving customers' capacity to explore and utilise digital products and platforms. The overall mean scores for digital literacy on the Likert scale are 3.7995 in Malaysia and 3.9216 in Indonesia, signifying a positive assessment of AI's impact on various aspects of patrons' digital literacy skills in library contexts.

Comparing groups from Malaysia (M = 3.7994, SD = 0.73681) and Indonesia (M = 3.9216, SD = 0.53797) in terms of AI support for digital literacy, an independent samples t-test revealed no statistically significant difference between the Malaysian and Indonesian groups (t(142) = -1.150, p = 0.252). Despite the lack of statistical significance, a moderate effect size (Cohen's d = 0.62685) pointed to a discernible difference between the groups. Consequently, the null hypothesis (H0c) is upheld, suggesting no significant difference in the perception of AI support for digital literacy between Malaysia and Indonesia. It is noteworthy that while the effect size is moderate and worthy of attention, its practical significance in this context may be limited.

4. Discussion

In pursuit of comprehensive insights into the role of AI in library services, this study embarked on a dual-pronged research approach, guided by two distinct yet interconnected research objectives. The primary aim was to assess librarian perspectives on the support provided by AI to users and patrons, specifically focusing on its efficacy in enhancing learning experiences, fostering lifelong learning, and advancing digital literacy initiatives. In tandem with this overarching goal, the secondary objective guided the study's exploration into cross-cultural distinctions, comparing the perspectives of librarians in Malaysia and Indonesia. This comparative analysis aimed to discern potential variations in how librarians from these diverse regions perceive and harness the potential of AI tools in fulfilling the educational and informational needs of library users.

The study's findings build upon the extensive literature that underscores the transformative impact of AI in library services on user learning experiences. Aligning with the insights from Pratama, Sampelolo, and Lura [

42], Jaiswal and Arun [

43], Shin [

44], Somasundaram, Junaid, and Mangadu [

45], and Pataranutaporn et al. [

46], our research highlights librarians' recognition of AI tools' potential to provide precisely tailored and personalized learning experiences. The positive evaluations from our study echo the promises outlined in the literature, emphasizing how AI algorithms, by analyzing user preferences and interactions, contribute to prompt content delivery, thus fostering engagement and understanding of concepts. This aligns seamlessly with the discussions by Tahir and Tahir [

47] and Chen et al. [

48], who emphasize the real-time assistance provided by AI-driven virtual assistants, supporting the notion that these tools enhance accessibility for diverse user requirements. The literature, as established by Sekaran et al. [

49], Pan [

50], and Kaiss, Mansouri, and Poirier [

51], reinforces our findings by highlighting the transformation of traditional information retrieval into a more user-centric, efficient, and enriching learning experience. The positive evaluation of AI tools in our study echoes the sentiments expressed in the literature, showcasing the potential for AI to not only meet diverse learning needs but also to promote independence and self-directed learning among library users, thus aligning with the broader vision of a revolutionized learning landscape within libraries.

Within the context of lifelong learning, the findings of this study affirm and expand upon the literature by highlighting the empowering impact of AI tools in libraries. Building on the works of Elhossiny, Eladly, and Saber [

60], Araque et al. [

61], and Ogata et al. [

62], our research underscores how AI-driven systems contribute to personalized learning experiences. Librarians, recognizing the motivational enhancement facilitated by AI tools, observe that patrons can autonomously navigate and direct their own learning journeys, aligning with the personalized and adaptive educational experiences discussed in the literature. The positive perceptions also extend to the exploration of new knowledge domains, emphasizing the role of AI tools in assisting users in uncovering novel areas of interest. As Panda and Chakravarty [

63] and Adetayo [

64] highlight in their respective works, the incorporation of AI-powered virtual assistants and chatbots is instrumental in providing immediate and interactive support, enabling patrons to efficiently search for information, enhance comprehension, and maintain a continuous cycle of exploration. Additionally, Rivers and Holland [

65], as well as Kamalov, Santandreu Calonge, and Gurrib [

66], support our findings by emphasizing how AI technologies contribute to a dynamic learning environment, accommodating the evolving needs and interests of lifelong learners. In essence, the general assessment from our research reinforces the pivotal role of AI in not only fostering accessibility to diverse learning materials but also in cultivating a culture of continuous knowledge acquisition in the pursuit of lifelong learning.

The findings of this study contribute significantly to the existing literature on AI's role in promoting digital literacy within library services. Corroborating the insights from Koravuna and Surepally [

72], Sabbah and Sabbah [

73], and Sari and Alfiyan [

74], our research emphasizes the acknowledgment by librarians of the substantial value of AI technologies in augmenting information literacy skills. The literature cited, particularly the works of Jing et al. [

75], Sofia et al. [

76], and Esteva et al. [

77], underscores the pivotal role of AI in guiding patrons through the intricacies of the digital landscape, aiding in the evaluation of information credibility, and fostering critical thinking skills – aspects reaffirmed by librarians in our study. Moreover, Fidalgo and Thornmann's [

78] notion of personalized learning pathways generated by AI aligns seamlessly with our findings, as librarians recognize the targeted approach to digital literacy education facilitated by these algorithms. Our research extends the discourse by highlighting how librarians acknowledge AI's role in enhancing users' proficiency in utilizing digital tools, fostering digital communication skills, and heightening awareness of online privacy and security. These findings resonate with the literature's emphasis on AI's comprehensive influence on digital literacy within library settings, as outlined by Jing et al. [

75] and Sofia et al. [

76]. The synergy between our findings and the literature reinforces the notion that AI integration in library services goes beyond traditional information access, actively contributing to equipping users with the essential skills to navigate and thrive in the digital era, transcending geographical and cultural limitations. The comprehensive nature of AI's impact on digital literacy, as supported by both our study and the cited literature, highlights its transformative potential in enhancing the overall learning experience in libraries.

Our study's findings are intricately woven into the existing literature, particularly within the context of library collaborations and digital engagement practices between Malaysia and Indonesia. Puspitasari, Manan, and Anna's [

79] examination of library ecosystems underscored a sustained collaboration encompassing dimensions such as training programs and material borrowing procedures. This collective effort has likely contributed significantly to the advancement of libraries in both nations. The collaborative spirit identified in prior studies may have influenced our findings, where no statistically significant differences were discerned in the perceptions of AI support for learning experiences, lifelong learning, and digital literacy between Malaysian and Indonesian libraries.

Moreover, Rahmandita's [

80] exploration of library websites in Indonesia and Malaysia revealed a lack of significant distinctions in students' experiences, irrespective of institutional affiliation. This observation points towards a shared digital engagement experience within the library context. The absence of significant differences in our study's results concerning AI support for learning experiences and lifelong learning could be associated with this commonality in digital engagement experiences within library settings.

In connection with our formulated hypotheses, the study by Rusydiyah, Zaini Tamin, and Rahman [

81] investigating literacy policies across Malaysia, Indonesia, and Singapore offers pertinent insights. Their findings highlighted a commonality in the factors influencing the implementation of literacy initiatives, with a shared reliance on specialized literacy institutions across the three nations. This shared approach may have implications for our hypotheses, particularly in the context of digital literacy. The commonality in literacy initiatives could contribute to the lack of significant differences observed in the perceptions of AI support for digital literacy between Malaysian and Indonesian libraries.

Considering these scholarly insights within the context of our hypotheses, our results resonate with the collaborative nature of library ecosystems between Malaysia and Indonesia. The shared experiences and collaborative initiatives identified in the literature provide a robust justification for retaining the null hypotheses (H0a, H0b, and H0c), signifying no statistically significant differences in perceptions of AI support for learning experiences, lifelong learning, and digital literacy within library settings.

5. Conclusions

The study's findings emphasise a uniform and synchronised understanding of AI assistance among librarians in Malaysia and Indonesia. Librarians' subjective assessments indicate that regardless of the varied cultural and contextual backgrounds of these countries, there is a widespread acknowledgment of the beneficial influence of AI on learning experiences, lifelong learning, and digital literacy in libraries. These findings enhance our comprehension of the worldwide use of AI technologies in the library field, highlighting their essential function in creating contemporary library services.

This work provides major contributions both experimentally and practically to the subject of library science and technology. The findings provide a detailed picture of how librarians perceive AI help in various learning experiences, lifelong learning, and digital literacy. These insights contribute vital information to the existing research in this field. The study's empirical contribution is its investigation of subjective evaluations, which establishes a basis for future research to further examine the complex role of AI in libraries.

The study's findings provide practical and implementable insights for library professionals, legislators, and technology developers. By acknowledging the consistency in librarians' favourable views on the influence of AI, library experts can utilise this knowledge to strategically incorporate AI tools and technologies into their services. This will improve individualised learning, encourage community involvement, and advance digital literacy. The practical consequences of this study have a wide reach, as they influence the formulation of library policies, investment plans, and professional development activities. These implications are crucial in ensuring that libraries continue to adapt and respond effectively to technological innovations.

Although this study offers interesting information regarding librarians' impressions of AI support for learning experiences, lifelong learning, and digital literacy, it is important to highlight its notable limitations. Firstly, the study is dependent on perceptual measures, which inevitably contribute a subjective element to the assessment. Librarians' perceptions can be shaped by personal experiences and viewpoints, which may potentially result in variations in responses. In addition, the study is hindered by the relatively small sample size, consisting of only 59 participants from Malaysia and 85 participants from Indonesia. The limited sample size may not adequately represent the various perspectives within the librarian community of each country, thereby restricting the applicability of the findings. Increasing the size and variety of the sample could strengthen the study's reliability and yield a more thorough comprehension of librarians' perspectives on AI assistance in various settings.

Author Contributions

“Conceptualization, Masrek, M. N.; Methodology, All Authors; Data Collection, All Authors; Data Analysis, Masrek, M. N., Writing, Masrek, M. N., Writing Review, All Authors; Formatting, Shuhidan, S. M.; Logistics, Baharuddin, M. F".

Funding

This project receives funding from Kementerian Pendidikan, Kebudayaan, Riset dan Teknologi, Universitas Airlangga, Lembaga Penelitian dan Pengabdian Masyarakat, with registration of 2103/UN3.LPPM/PT.01.02/2023. We express sincere gratitude to our respected benefactor, as well as to all individuals who have made direct or indirect contributions to our research.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to the expert evaluators, participants, and the Research Management Centre of Universiti Teknologi MARA, Malaysia for their significant support in facilitating and enhancing the development of this study.

References

- Lund, B.; Wang, T. Chatting about ChatGPT: How May AI and GPT Impact Academia and Libraries? Library Hi Tech News 2023, 40, 26–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roumeliotis, K.I.; Tselikas, N.D. ChatGPT and Open-AI Models: A Preliminary Review. Future Internet 2023, 15, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanzode, K.C.A.; Sarode, R.D. Advantages and disadvantages of artificial intelligence and machine learning: A literature review. International Journal of Library & Information Science (IJLIS) 2020, 9, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, M.Y.; Naeem, S.B.; Bhatti, R. Artificial intelligence tools and perspectives of university librarians: An overview. Business Information Review 2020, 37, 116–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omame, I.M.; Alex-Nmecha, J.C. Artificial intelligence in libraries. In Managing and adapting library information services for future users 2020 (pp. 120-144). IGI Global.

- Owolabi, K.A.; Abayomi, A.O.; Aderibigbe, N.A.; Kemdi, O.M.; Oluwaseun, O.A.; Okorie, C.N. Awareness and Readiness of Nigerian Polytechnic Students towards Adopting Artificial Intelligence in Libraries. Journal of Information and Knowledge 2022, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owate, C.N.; Ogonu, J.G. Assessment of Preparedness of Academic Libraries towards the Use and Adoption of Robotic Technologies in Public Universities in Bayelsa State. Library of Progress-Library Science, Information Technology & Computer 2023, 43.

- Lund, B.D.; Omame, I.; Tijani, S.; Agbaji, D. Perceptions toward artificial intelligence among academic library employees and alignment with the diffusion of innovations’ adopter categories. College & Research Libraries 2020, 81, 865. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews, J.E.; Ward, H.; Yoon, J. UTAUT as a model for understanding intention to adopt AI and related technologies among librarians. The Journal of Academic Librarianship 2021, 47, 102437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Song, D.; Li, W. Research on factors influencing smart library users’ use intention in the era of artificial intelligence. Journal of Physics: Conference Series 2021, 2025, 012089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abumandour, E.S.T. Public libraries' role in supporting e-learning and spreading lifelong education: a case study. Journal of Research in Innovative Teaching & Learning 2020, 14, 178–217. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston, N. The shift towards digital literacy in Australian university libraries: Developing a digital literacy framework. Journal of the Australian Library and Information Association 2020, 69, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujita, M.S.L.; Agustín-Lacruz, C.; Tolare, J.B.; Terra, A.L.; Bueno-de-la-Fuente, G. Institutional repositories and knowledge organization: A bibliographic study from Library and Information Science. Education for Information 2023, 39, 51–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masrek, M.N.; Susantari, T.; Mutia, F.; Yuwinanto, H.P.; Atmi, R.T. Enabling Education Everywhere: How artificial intelligence empowers ubiquitous and lifelong learning. Environment-Behaviour Proceedings Journal 2024, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Hou, J.; Zhang, N.; Zhang, M. Research on how human intelligence, consciousness, and cognitive computing affect the development of artificial intelligence. Complexity 2020, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, T.V.N. , Gaddam, A., Kurni, M., & Saritha, K. Reliance on artificial intelligence, machine learning and deep learning in the era of industry 4.0. Smart healthcare system design: security and privacy aspects 2022, 281–299. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, R.Y.; Coyner, A.S.; Kalpathy-Cramer, J.; Chiang, M.F.; Campbell, J.P. Introduction to machine learning, neural networks, and deep learning. Translational vision science & technology 2020, 9, 14–14. [Google Scholar]

- Worden, K.; Tsialiamanis, G.; Cross, E.J.; Rogers, T.J. Artificial neural networks. In Machine Learning in Modeling and Simulation: Methods and Applications 2023, (pp. 85-119). Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Bharadiya, J.P. A comparative study of business intelligence and artificial intelligence with big data analytics. American Journal of Artificial Intelligence 2023, 7, 24. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, R.S.; Lee, R.S. AI fundamentals. Artificial intelligence in daily life 2020, 19–37. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, M.; Biros, D. AI and its implications for organisations. In Information Technology in Organisations and Societies: Multidisciplinary Perspectives from AI to Technostress 2021, (pp. 1-24). Emerald Publishing Limited.

- L’Esteve, R.C. Impacts of Modern AI and ML Trends. In The Cloud Leader’s Handbook: Strategically Innovate, Transform, and Scale Organizations 2023 (pp. 135-155). Berkeley, CA: Apress.

- Cao, G.; Duan, Y.; Edwards, J.S.; Dwivedi, Y.K. Understanding managers’ attitudes and behavioral intentions towards using artificial intelligence for organizational decision-making. Technovation 2021, 106, 102312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wang, H. Application of Artificial Intelligence in Libraries. In 2021 3rd International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Advanced Manufacture (AIAM) 2022, (pp. 323-329). IEEE.

- Ajani, Y.A.; Tella, A.; Salawu, K.Y.; Abdullahi, F. Perspectives of librarians on awareness and readiness of academic libraries to integrate artificial intelligence for library operations and services in Nigeria. Internet Reference Services Quarterly 2022, 26, 213–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harisanty, D.; Anna NE, V.; Putri, T.E.; Firdaus, A.A.; Noor Azizi, N.A. Leaders, practitioners and scientists' awareness of artificial intelligence in libraries: a pilot study. Library Hi Tech 2022. [CrossRef]

- Chaoying, X. Research on classification and identification of library based on artificial intelligence. Journal of Intelligent & Fuzzy Systems 2021, 40, 6937–6948. [Google Scholar]

- Rhanoui, M.; Mikram, M.; Yousfi, S.; Kasmi, A.; Zoubeidi, N. A hybrid recommender system for patron driven library acquisition and weeding. Journal of King Saud University-Computer and Information Sciences 2022, 34, 2809–2819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawaz, N.; Saldeen, M.A. Artificial intelligence chatbots for library reference services. Journal of Management Information & Decision Sciences 2020, 23. [Google Scholar]

- Subaveerapandiyan, A. Application of artificial intelligence (AI) in libraries and its impact on library operations review. Library Philosophy and Practice 2023, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Adhiatma, A.; Sari, R.D.; Fachrunnisa, O. The role of personal dexterity and incentive gamification to enhance employee learning experience and performance. Cognition, Technology & Work 2022, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Jahnke, I. Quality of digital learning experiences–effective, efficient, and appealing designs? . The International Journal of Information and Learning Technology, 2023, 40, 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Videnovik, M.; Trajkovik, V.; Kiønig, L.V.; Vold, T. Increasing quality of learning experience using augmented reality educational games. Multimedia tools and applications, 2020, 79, 23861–23885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czerkawski, B.; Berti, M. Learning experience design for augmented reality. Research in Learning Technology 2021, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shraddha, B.H.; Iyer, N.C.; Kotabagi, S.; Mohanachandran, P.; Hangal, R.V.; Patil, N.; Eligar, S.; Patil, J. Enhanced learning experience by comparative investigation of pedagogical approach: Flipped classroom. Procedia Computer Science, 2020, 172, 22–27. [Google Scholar]

- Ummihusna, A.; Zairul, M. Investigating immersive learning technology intervention in architecture education: a systematic literature review. Journal of Applied Research in Higher Education, 2022, 14, 264–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shemshack, A.; Kinshuk; Spector, J.M. A comprehensive analysis of personalized learning components. Journal of Computers in Education 2021, 8, 485–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, C.W.; Rafatirad, S.; Sayadi, H. Advancing personalized and adaptive learning experience in education with artificial intelligence. In 2023 32nd Annual Conference of the European Association for Education in Electrical and Information Engineering (EAEEIE) 2023, (pp. 1-6). IEEE.

- Lee, P.C. Technological innovation in libraries. Library Hi Tech, 2021, 39, 574–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garoufali, A.; Garoufallou, E. Transforming libraries into learning collaborative hubs: the current state of physical spaces and the perceptions of Greek librarians concerning implementation of the “Learning Commons” model. Global Knowledge, Memory and Communication 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dempsey, P.R. Referring academic library chat reference patrons: how subject librarians decide. Reference Services Review, 2021, 49, 94–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratama, M.P.; Sampelolo, R.; Lura, H. Revolutionizing education: harnessing the power of artificial intelligence for personalized learning. Klasikal: Journal of Education, Language Teaching and Science, 2023, 5, 350–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, A.; Arun, C.J. Potential of Artificial Intelligence for Transformation of the Education System in India. International Journal of Education and Development using Information and Communication Technology, 2021, 17, 142–158. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, D. User perceptions of algorithmic decisions in the personalized AI system: Perceptual evaluation of fairness, accountability, transparency, and explainability. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 2020, 64, 541–565. [Google Scholar]

- Somasundaram, M.; Junaid, K.M.; Mangadu, S. Artificial intelligence (AI) enabled intelligent quality management system (IQMS) for personalized learning path. Procedia Computer Science, 2020, 172, 438–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pataranutaporn, P.; Danry, V.; Leong, J.; Punpongsanon, P.; Novy, D.; Maes, P.; Sra, M. AI-generated characters for supporting personalized learning and well-being. Nature Machine Intelligence, 2021, 3, 1013–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahir, A.; Tahir, A. AI-driven Advancements in ESL Learner Autonomy: Investigating Student Attitudes Towards Virtual Assistant Usability. In Linguistic Forum-A Journal of Linguistics, 2023, 5, 50–56. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Jensen, S.; Albert, L.J.; Gupta, S.; Lee, T. Artificial intelligence (AI) student assistants in the classroom: Designing chatbots to support student success. Information Systems Frontiers, 2023, 25, 161–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekaran, K.; Chandana, P.; Jeny JR, V.; Meqdad, M.N.; Kadry, S. Design of optimal search engine using text summarization through artificial intelligence techniques. TELKOMNIKA (Telecommunication Computing Electronics and Control), 2020, 18, 1268–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Z. Optimization of Information Retrieval Algorithm for Digital Library Based on Semantic Search Engine. In 2020 International conference on computer engineering and application (ICCEA) 2020, (pp. 364-367). IEEE.

- Kaiss, W.; Mansouri, K.; Poirier, F. Effectiveness of an Adaptive Learning Chatbot on Students’ Learning Outcomes Based on Learning Styles. International Journal of Emerging Technologies in Learning 2023, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padilha, J.M.; Ribeiro, A.; Rosa, J.; Marques, D.; Machado, P.P. Clinical virtual simulation as lifelong learning strategy—Nurse's verdict. Clinical Simulation in Nursing, 2020, 47, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seevaratnam, V.; Gannaway, D.; Lodge, J. Design thinking-learning and lifelong learning for employability in the 21st century. Journal of Teaching and Learning for Graduate Employability, 2023, 14, 182–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, R.L. Developing lifelong learning with heutagogy: contexts, critiques, and challenges. Distance Education, 2020, 41, 381–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilag OK, T.; Malbas, M.H.; Miñoza, J.R.; Ledesma MM, R.; Vestal AB, E.; Sasan JM, V. Education Programs in Developing Lifelong Learning Competence. European Journal of Higher Education and Academic Advancement Volume 2023, 1. [Google Scholar]

- McLean, S. Understanding the evolving context for lifelong education: global trends, 1950–2020. International Journal of Lifelong Education, 2022, 41, 5–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pendy, B. From Traditional to Tech-Infused: The Evolution of Education. BULLET: Jurnal Multidisiplin Ilmu, 2023, 2, 767–777. [Google Scholar]

- Tryhub, O. he Concept of Lifelong Learning: The European Dimension. Collection of scientific papers «ΛΌГOΣ», (December 22, 2023; Boston, USA), 2023, 294-299.

- Díaz, J.; Saldaña, C.; Avila, C. Virtual world as a resource for hybrid education. International Journal of Emerging Technologies in Learning (iJET), 2020, 15, 94–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhossiny, M.; Eladly, R.; Saber, A. The integration of psychology and artificial intelligence in e-learning systems to guide the learning path according to the learner’s style and thinking. International Journal of Advanced and Applied Sciences, 2022, 9, 162–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araque, W.O.A.; Romero, A.F.; GonzáLez, K.J.D.; Pongutá, D.A.G. (2023). Exploring Learning Styles In Higher Education Through Artificial Intelligence Platforms. Russian Law Journal 2023, 11, 829–836. [Google Scholar]

- Ogata, H.; Flanagan, B.; Takami, K.; Dai, Y.; Nakamoto, R.; Takii, K. EXAIT: Educational eXplainable Artificial Intelligent Tools for personalized learning. Research and Practice in Technology Enhanced Learning 2024, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panda, S.; Chakravarty, R. Adapting intelligent information services in libraries: A case of smart AI chatbots. Library Hi Tech News, 2022, 39, 12–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adetayo, A.J. Artificial intelligence chatbots in academic libraries: the rise of ChatGPT. Library Hi Tech News, 2023, 40, 18–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivers, C.; Holland, A. Management Education and Artificial Intelligence: Toward Personalized Learning. In The Future of Management Education, 2022, (pp. 184-204). Routledge.

- Kamalov, F.; Santandreu Calonge, D.; Gurrib, I. New era of artificial intelligence in education: Towards a sustainable multifaceted revolution. Sustainability, 2023, 15, 12451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pangrazio, L.; Godhe, A.L.; Ledesma, A.G.L. What is digital literacy? A comparative review of publications across three language contexts. E-learning and Digital Media, 2020, 17, 442–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildiz, E.P. Opinions of Academicians on Digital Literacy: A Phenomenology Study. Cypriot journal of educational sciences, 2020, 15, 469–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falloon, G. From digital literacy to digital competence: the teacher digital competency (TDC) framework. Educational Technology Research and Development, 2020, 68, 2449–2472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.; Kim, H.S.; Park, H.W. A scientometric study of digital literacy, ICT literacy, information literacy, and media literacy. Journal of Data and Information Science, 2020, 6, 116–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukasz, T.; Ludvik, E. Online safety as a new component of digital literacy for young people. Интеграция oбразoвания, 2020, 24, 172–184. [Google Scholar]

- Koravuna, S.; Surepally, U.K. Educational gamification and artificial intelligence for promoting digital literacy. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Intelligent and Innovative Computing Applications 2020; pp. 1–6.

- Sabbah, K.; Sabbah. Digital Literacy in the Palestinian Public Schools: The Influence of Gamification-Based Learning. In International Conference on Learning and Teaching in the Digital World. 2022, (pp. 61-79). Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore.

- Sari, D.N.; Alfiyan, A.R. Peran Adaptasi Game (Gamifikasi) dalam Pembelajaran untuk Menguatkan Literasi Digital: Systematic Literature Review. UPGRADE: Jurnal Pendidikan Teknologi Informasi, 2023, 1, 43–52. [Google Scholar]

- Jing, N.; Wu, Z.; Lyu, S.; Sugumaran, V. Information credibility evaluation in online professional social network using tree augmented naïve Bayes classifier. Electronic Commerce Research, 2021, 21, 645–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sofia, M.; Fraboni, F.; De Angelis, M.; Puzzo, G.; Giusino, D.; Pietrantoni, L. The impact of artificial intelligence on workers’ skills: Upskilling and reskilling in organisations. Informing Science: The International Journal of an Emerging Transdiscipline, 2023, 26, 39–68. [Google Scholar]

- Esteva, A.; Kale, A.; Paulus, R.; Hashimoto, K.; Yin, W.; Radev, D.; Socher, R. COVID-19 information retrieval with deep-learning based semantic search, question answering, and abstractive summarization. NPJ digital medicine, 2021, 4, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fidalgo, P.; Thormann, J. The Future of Lifelong Learning: The Role of Artificial Intelligence and Distance Education. 2024.

- Puspitasari, D.; Manan, E.F.; Anna, N.V. Kerjasama Dan Jaringan Perpustakaan Antara Indonesia-Malaysia Indonesia-Malaysia Library Cooperation and Networking. Edulib 2015, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmandita, E. Evaluating University Library Websites in Indonesia and Malaysia. In Proceedings of the First International Conference on Literature Innovation in Chinese Language, LIONG 2021, Purwokerto, Indonesia., 19-20 October 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Rusydiyah, E.F.; Zaini Tamin, A.R.; Rahman, M.R. Literacy policy in southeast Asia: a comparative Study between Singapore, Malaysia, and Indonesia. Center for Educational Policy Studies Journal, 2023, 13, 79–96. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).