Submitted:

21 May 2024

Posted:

21 May 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bacterial Strains and Culture Conditions

2.2. Preparation of Inocula

2.3. Preparation and Inoculation of Pineapple Juice

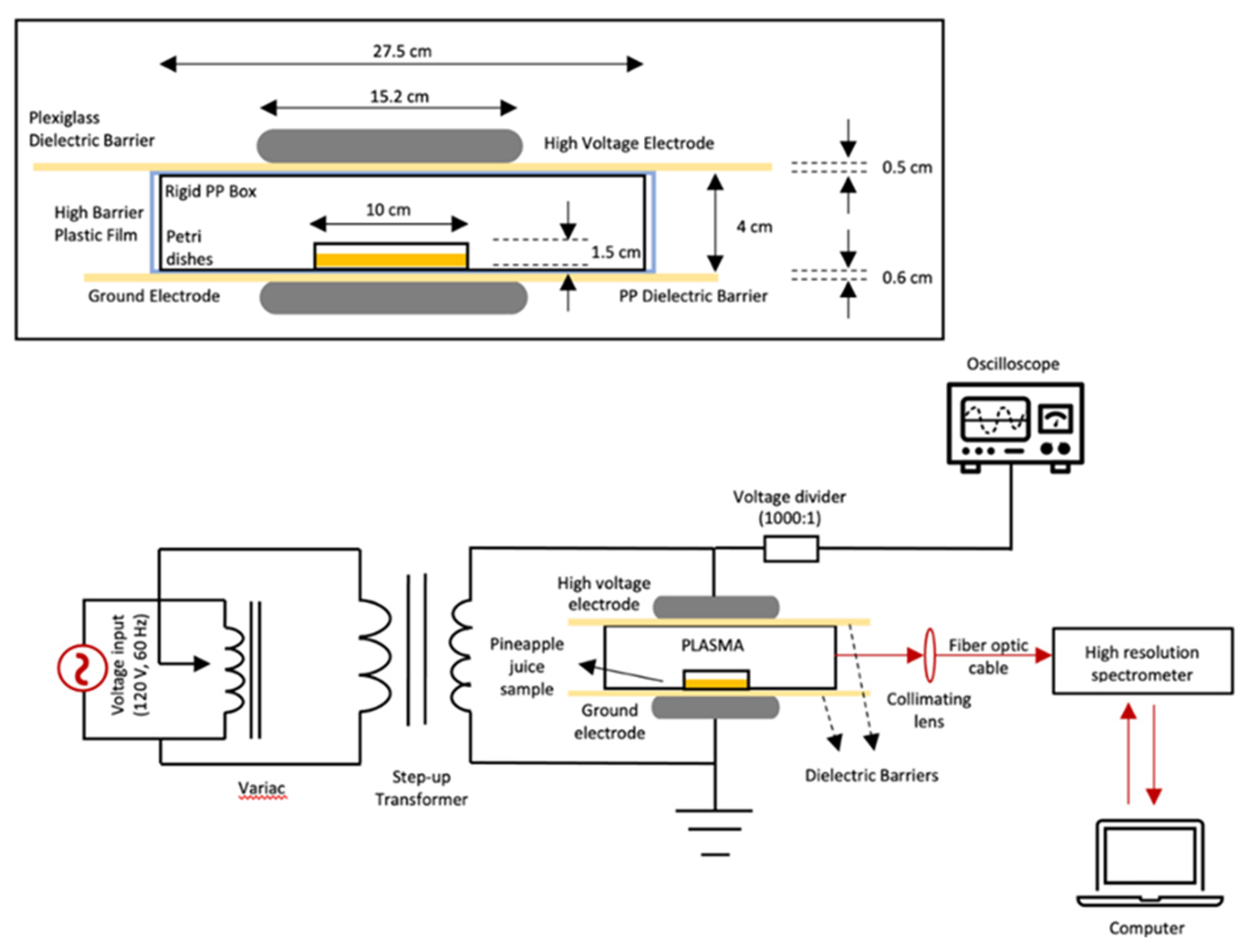

2.4. Treatment of Juice Samples with HVACP

2.5. Microbial Analysis of Juice Samples

2.6. Calculation of D-Values

2.7. Determination of Sub-Lethal Injury

2.8. pH Evaluation of Pineapple Juice

2.9. Measurement of Degrees Brix of Pineapple Juice

2.10. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

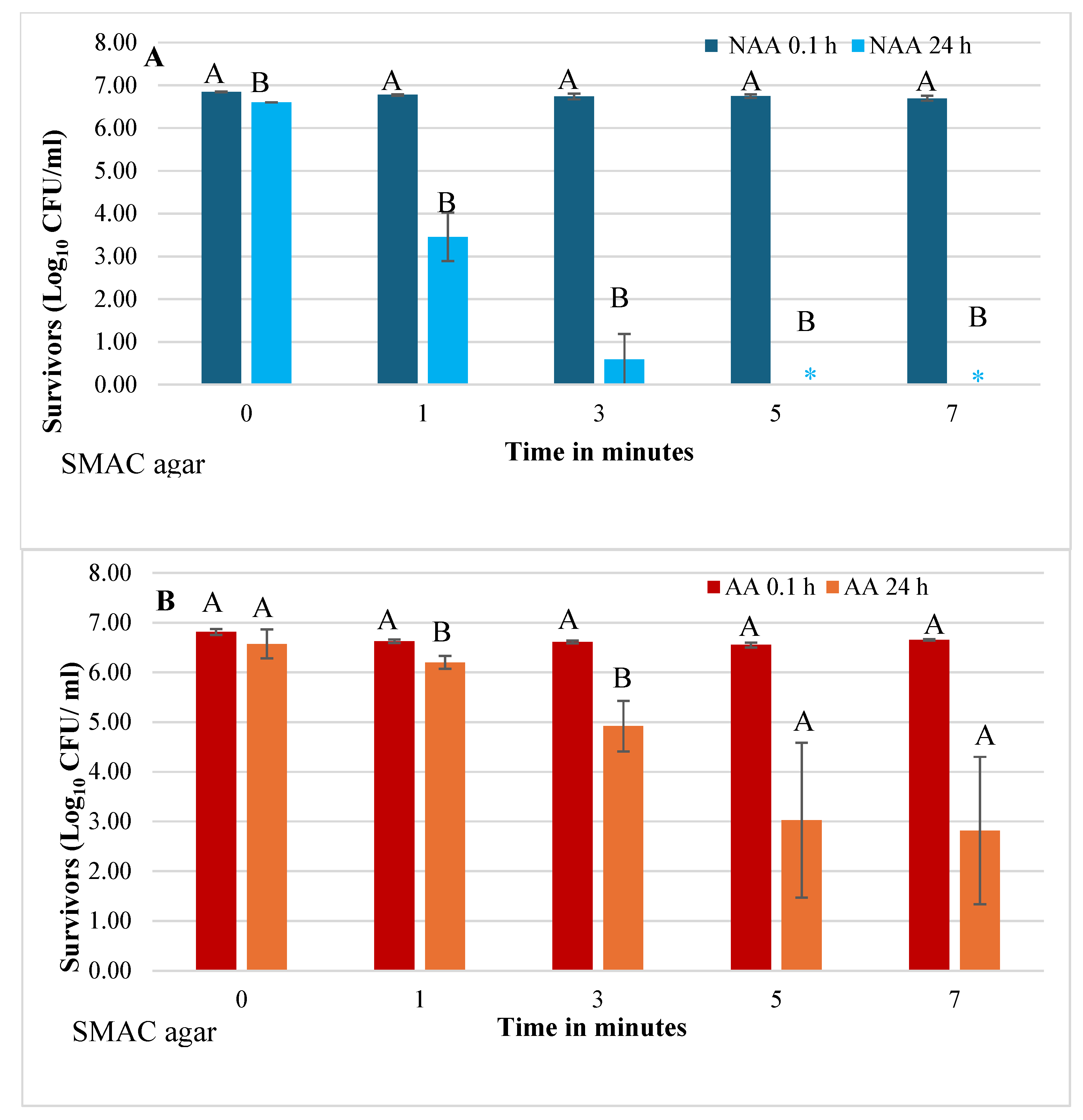

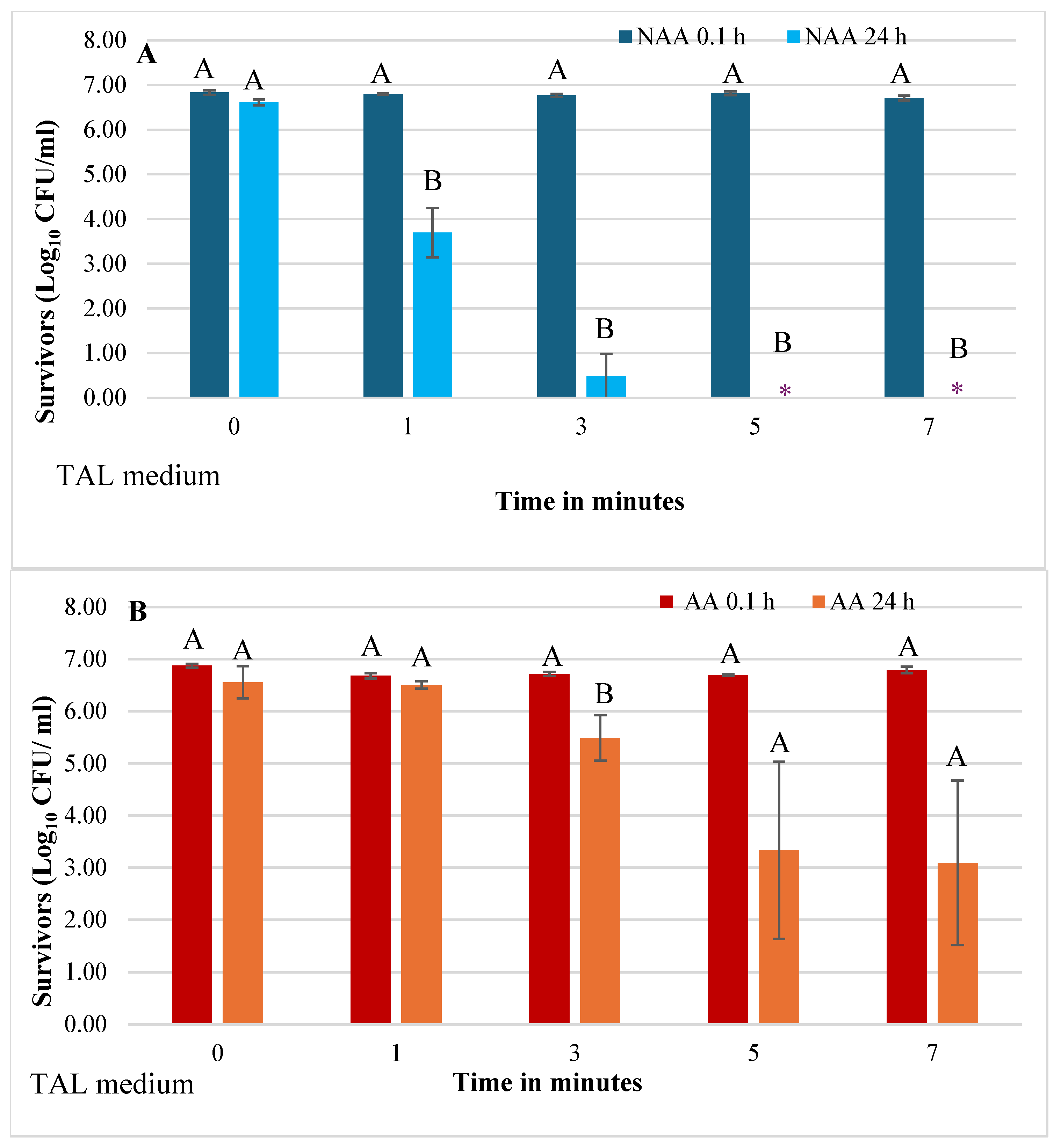

3.1. Survivors of E. coli in Pineapple Juice at 0.1h and 24 h after HVACP Treatment

3.2. Effect of Physiological State on E. coli O157:H7 Tolerance of HVACP in Juice

3.3. D-Values of NAA and AA E. coli in Pineapple Juice

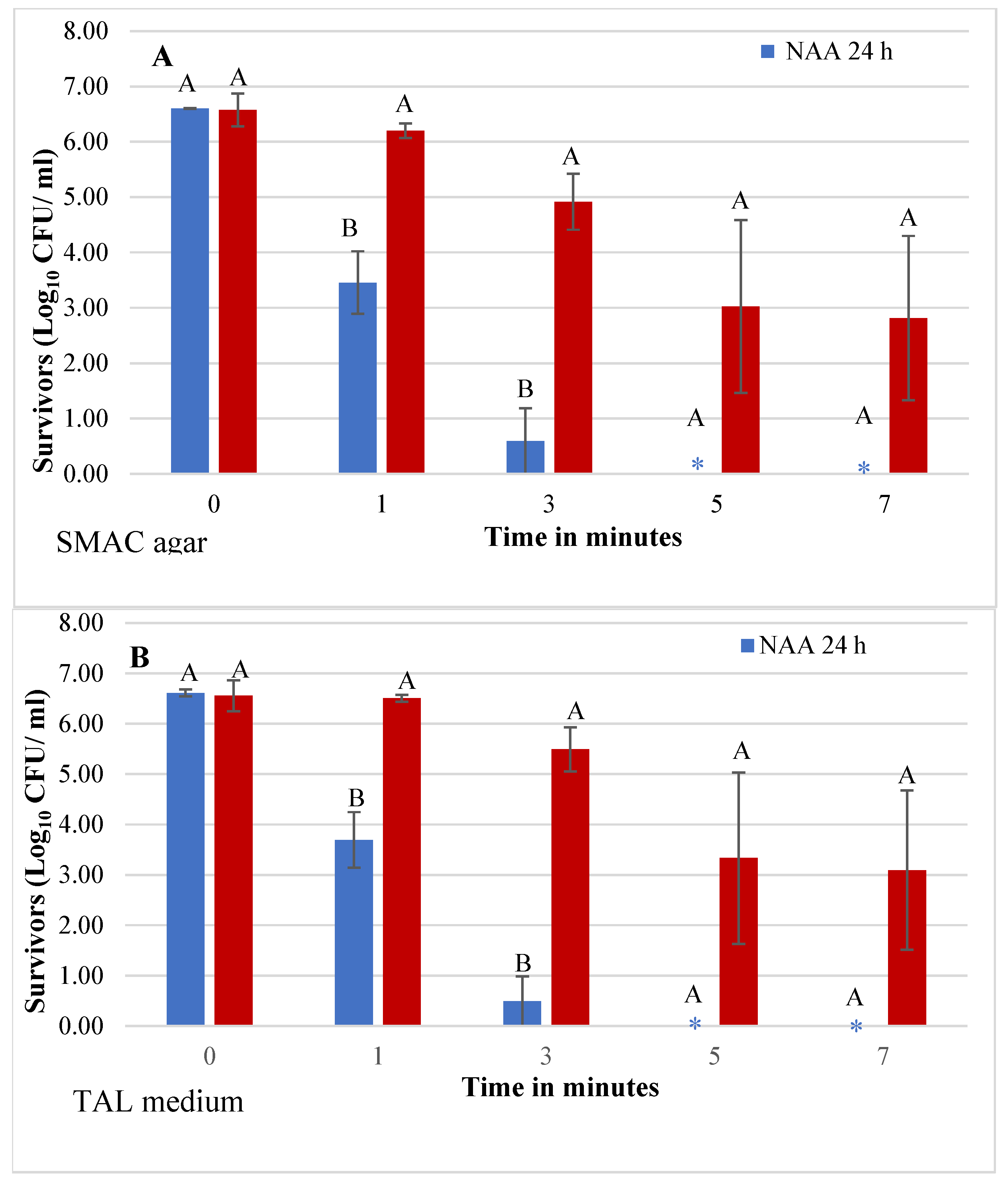

3.4. Sub-Lethal Injury of NAA and AA E. coli in Pineapple Juice

3.5. pH and Degrees Brix of Pineapple Juice

4. Discussion

4.1. Stress Adaptation in Foodborne Microorganisms

4.2. Survivors of E. coli O157:H7 in Juice after HVACP Treatment

4.3. Effect of Physiological States on Numbers of E. coli Survivors

4.3. D-Values for E. coli O157:H7 in Pineapple Juice

4.3. Sub-Lethal Injury of NAA and AA E. coli in Pineapple Juice

4.3. pH and Degrees Brix of Pineapple Juice

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- 1Grand View Research. (2023). Fresh Fruits Market Size & Share| Industry Report. In Market Analysis Report. https://www.grandviewresearch.com/industry-analysis/fresh-fruits-market-report.

- Technavio. (2022, December). Juices Market - Size, Share, Growth, Trends, Industry Analysis 2027. https://www.technavio.com/report/juices-market-industry-analysis.

- Pem, D., & Jeewon, R. (2015). Fruit and Vegetable Intake: Benefits and Progress of Nutrition Education Interventions- Narrative Review Article. Iranian Journal of Public Health, 44(10), 1309. /pmc/articles/PMC4644575/.

- Dewanti-Hariyadi, R.; Maria, A.; Sandoval, P. (2013). Microbiological quality and safety of fruit juices. Food Rev. Int, 1, 54-57.

- Danyluk, M. D., Goodrich-Schneider, R. M., Schneider, K. R., Harris, L. J.; Worobo, R. W. (2012). Outbreaks of Foodborne Disease Associated with Fruit and Vegetable Juices, 1922–2010: FSHN12-04/FS188. https://journals.flvc.org/edis/article/download/119658/117576.

- Jajere, S. M. (2019). A review of Salmonella enterica with particular focus on the pathogenicity and virulence factors, host specificity and antimicrobial resistance including multidrug resistance. Veterinary world, 12(4), 504. [CrossRef]

- Salfinger, Y. (Ed.), & Tortorello, M. L. (Ed.). (2015). Compendium of Methods for the Microbiological Examination of Foods (Y. Salfinger & M. Lou Tortorello, Eds.; 5th ed.). American Public Health Association.

- Macarisin, D., Wooten, A., De Jesus, A., Hur, M., Bae, S., Patel, J., Evans, P., Brown, E., Hammack, T., & Chen, Y. (2017). Internalization of Listeria monocytogenes in cantaloupes during dump tank washing and hydrocooling. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 257, 165–175. [CrossRef]

- Mendonca, A. (2005). Bacterial infiltration and internalization in fruits and vegetables. In Produce degradation: Pathways and prevention (pp. 441–462). CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL. 10.1201/9781420039610.ch14.

- FDA. (2008, February). Guidance for Industry: Guide to Minimize Microbial Food Safety Hazards of Fresh-cut Fruits and Vegetables | FDA. https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/guidance-industry-guide-minimize-microbial-food-safety-hazards-fresh-cut-fruits-and-vegetables.

- Thomas-Popo, E., Mendonca, A., Dickson, J., Shaw, A., Coleman, S., Daraba, A., Jackson-Davis, A., & Woods, F. (2019). Isoeugenol significantly inactivates Escherichia coli O157:H7, Salmonella enterica, and Listeria monocytogenes in refrigerated tyndallized pineapple juice with added Yucca schidigera extract. Food Control, 106, 106727. [CrossRef]

- FDA. (2001). Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Point (HAACP); Procedures for the Safe and Sanitary Processing and Importing of Juice. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2001/01/19/01-1291/hazard-analysis-and-critical-control-point-haacp-procedures-for-the-safe-and-sanitary-processing-and.

- Wu, W., Xiao, G., Yu, Y., Xu, Y., Wu, J., Peng, J., & Li, L. (2021). Effects of high pressure and thermal processing on quality properties and volatile compounds of pineapple fruit juice. Food Control, 130, 108293. [CrossRef]

- Roobab, U., Aadil, R. M., Madni, G. M., & Bekhit, A. E. D. (2018). The Impact of Nonthermal Technologies on the Microbiological Quality of Juices: A Review. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety, 17(2), 437–457. [CrossRef]

- Calvo, T., Alvarez-Ordóñez, A., Prieto, M., Bernardo, A., López, M. (2017). Stress adaptation has a minor impact on the effectivity of Non-Thermal Atmospheric Plasma (NTAP) against Salmonella spp. Food Research International, 102, 519–525. [CrossRef]

- Van Impe, J., Smet, C., Tiwari, B., Greiner, R., Ojha, S., Stulić, V., Vukušić, T., & Režek Jambrak, A. (2018). State of the art of nonthermal and thermal processing for inactivation of micro-organisms. Journal of Applied Microbiology, 125(1), 16–35. [CrossRef]

- Nonglait, D. L., Chukkan, S. M., Arya, S. S., Bhat, M. S., & Waghmare, R. (2022). Emerging non-thermal technologies for enhanced quality and safety of fruit juices. International Journal of Food Science & Technology, 57(10), 6368-6377. [CrossRef]

- Yepez, X., Illera, A. E., Baykara, H., & Keener, K. (2022). Recent advances and potential applications of atmospheric pressure cold plasma technology for sustainable food processing. Foods, 11(13), 1833.

- Ozen, E., & Singh, R. K. (2020). Atmospheric cold plasma treatment of fruit juices: A review. Trends in Food Science & Technology, 103, 144–151. [CrossRef]

- Misra, N. N., Pankaj, S. K., Frias, J. M., Keener, K. M., & Cullen, P. J. (2015). The effects of nonthermal plasma on chemical quality of strawberries. Postharvest Biology and Technology, 110, 197–202. [CrossRef]

- Bourke, P., Ziuzina, D., Han, L., Cullen, P. J., & Gilmore, B. F. (2017). Microbiological interactions with cold plasma. Journal of Applied Microbiology, 123(2), 308-324. [CrossRef]

- Nicol, M. K. J., Brubaker, T. R., Honish, B. J., Simmons, A. N., Kazemi, A., Geissel, M. A., Whalen, C. T., Siedlecki, C. A., Bilén, S. G., Knecht, S. D., & Kirimanjeswara, G. S. (2020). Antibacterial effects of low-temperature plasma generated by atmospheric-pressure plasma jet are mediated by reactive oxygen species. Scientific Reports 2020 10:1, 10(1), 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Niemira, B. A. (2012). Cold plasma decontamination of foods. Annual Review of Food Science and Technology, 3(1), 125–142. [CrossRef]

- Han, J. Y., Song, W. J., Eom, S., Kim, S. B., Kang, D. H. (2020). Antimicrobial efficacy of cold plasma treatment against food-borne pathogens on various foods. Journal of Physics D: Applied Physics, 53(20), 204003. [CrossRef]

- Ucar, Y., Ceylan, Z., Durmus, M., Tomar, O., & Cetinkaya, T. (2021). Application of cold plasma technology in the food industry and its combination with other emerging technologies. Trends in Food Science & Technology, 114, 355–371. [CrossRef]

- Liao, X., Ma, Y., Daliri, E. B. M., Koseki, S., Wei, S.; Liu, D., Ye, X., Chen, S., Ding, T. (2020). Interplay of antibiotic resistance and food-associated stress tolerance in foodborne pathogens. Trends in Food Science & Technology, 95, 97–106. [CrossRef]

- Begley, M.; Hill, C. (2015). Stress adaptation in foodborne pathogens. Annual review of food science and technology, 6, 191-210.

- Wu, R. A., Yuk, H. G., Liu, D., & Ding, T. (2022). Recent advances in understanding the effect of acid-adaptation on the cross-protection to food-related stress of common foodborne pathogens. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, 62(26), 7336–7353. [CrossRef]

- Buchanan, R. L., Edelson, S. G., Snipes, K., Boyd, G. (1998). Inactivation of Escherichia coli O157:H7 in apple juice by irradiation. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 64(11), 4533–4535. [CrossRef]

- Yuk, H.-G., & Marshall, D. L. (2005). Influence of Acetic, Citric, and Lactic Acids on Escherichia coli O157:H7 Membrane Lipid Composition, Verotoxin Secretion, and Acid Resistance in Simulated Gastric Fluid. In Journal of Food Protection (Vol. 68, Issue 4). http://meridian.allenpress.com/jfp/article-pdf/68/4/673/1676337/0362-028x-68_4_673.pdf.

- Haberbeck, L. U., Wang, X., Michiels, C., Devlieghere, F., Uyttendaele, M., Geeraerd, A. H. (2017). Cross-protection between controlled acid-adaptation and thermal inactivation for 48 Escherichia coli strains. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 241, 206–214. [CrossRef]

- Xu, L., Garner, A. L., Tao, B., & Keener, K. M. (2017). Microbial Inactivation and Quality Changes in Orange Juice Treated by High Voltage Atmospheric Cold Plasma. Food and Bioprocess Technology, 10(10), 1778–1791. [CrossRef]

- Liao, X., Li, J.; Suo, Y., Ahn, J., Liu, D., Chen, S., Hu, Y., Ye, X., Ding, T. (2018). Effect of preliminary stresses on the resistance of Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus toward non-thermal plasma (NTP) challenge. Food Research International, 105, 178–183. [CrossRef]

- Wu, D., Forghani, F., Daliri, E. B. M., Li, J., Liao, X., Liu, D., ... & Ding, T. (2020). Microbial response to some nonthermal physical technologies. Trends in Food Science & Technology, 95, 107-117. [CrossRef]

- Wesche, A. M., Gurtler, J. B., Marks, B. P., & Ryser, E. T. (2009). Stress, sublethal injury, resuscitation, and virulence of bacterial foodborne pathogens. Journal of Food Protection, 72(5), 1121–1138. [CrossRef]

- Ray, B. (1989). Injured index and pathogenic bacteria: occurence and detection in foods, water and feeds. CRC Press, Boca Raton FL.

- Busch, S. V., & Donnelly, C. W. (1992). Development of a repair-enrichment broth for resuscitation of heat-injured Listeria monocytogenes and Listeria innocua. Applied and environmental microbiology, 58(1), 14-20.

- Espina, L., García-Gonzalo, D., & Pagán, R. (2016). Detection of thermal sublethal injury in Escherichia coli via the selective medium plating technique: mechanisms and improvements. Frontiers in microbiology, 7, 208323. [CrossRef]

- Liao, X., Li, J., Muhammad, A. I., Suo, Y., Chen, S., Ye, X.; Liu, D., Ding, T. (2018). Application of a Dielectric Barrier Discharge Atmospheric Cold Plasma (Dbd-Acp) for Eshcerichia coli Inactivation in Apple Juice. Journal of Food Science, 83(2), 401–408. [CrossRef]

- Yepez, X. V., & Keener, K. M. (2016). High-voltage atmospheric cold plasma (HVACP) hydrogenation of soybean oil without trans-fatty acids. Innovative Food Science & Emerging Technologies, 38, 169-174.

- Deepak, G. D., Joshi, N. K., Prakash, R. (2020). The modelling and characterization of dielectric barrier discharge-based cold plasma sets. https://www.cambridgescholars.com/product/978-1-5275-4539-7.

- Rodriguez, E., Arques, J. L., Nunez, M., Gaya, P., & Medina, M. (2005). Combined effect of high-pressure treatments and bacteriocin-producing lactic acid bacteria on inactivation of Escherichia coli O157: H7 in raw-milk cheese. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 71(7), 3399-3404.

- Wuytack, E. Y., Phuong, L. D. T., Aertsen, A., Reyns, K. M. F., Marquenie, D., De Ketelaere, B., Masschalck, B., Van Opstal, I., Diels, A. M. J., & Michiels, C. W. (2003). Comparison of sublethal injury induced in Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium by heat and by different nonthermal treatments. Journal of Food Protection, 66(1), 31–37. [CrossRef]

- Guillén, S., Nadal, L., Álvarez, I., Mañas, P., Cebrián, G. (2021). Impact of the resistance responses to stress conditions encountered in food and food processing environments on the virulence and growth fitness of non-typhoidal Salmonellae. Foods. Mar 14;10(3):617.

- Ding, T., Xinyu, L., Feng, J. The importance of understanding the stress response in foodborne pathogens along the food production chain. In Stress Responses of Foodborne Pathogens, Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2022, pp. 3-31. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-030-90578-1_1.

- Singh, A., & Yemmireddy, V. (2022). Pre-Growth Environmental Stresses Affect Foodborne Pathogens Response to Subsequent Chemical Treatments. Microorganisms, 10(4). [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q., Buchanan, R. L., & Tikekar, R. V. (2019). Evaluation of adaptive response in E. coli O157:H7 to UV light and gallic acid based antimicrobial treatments. Food Control, 106, 106723. [CrossRef]

- Hu, S., Yu, Y., Lv, Z., Shen, J., Ke, Y., Xiao, X. (2020). Proteomics study unveils ROS balance in acid-adapted Salmonella Enteritidis. Food Microbiology, 92, 103585. [CrossRef]

- Hartanto, V. (2022). Application of atmospheric cold plasma for inactivation of foodborne enteric pathogens on raw and dry roasted pistachio kernels and in pineapple juice M.S. Thesis, Iowa State University, Ames, Iowa 50011, May 2022. https://www.proquest.com/docview/2679879590?pq-origsite=gscholar&fromopenview=true&sourcetype=Dissertations%20&%20Theses.

- Couto, D. S., Cabral, L. M. C., da Matta, V. M.; Deliza, R., de Grandi Castro Freitas, D. (2011). Concentration of pineapple juice by reverse osmosis: physicochemical characteristics and consumer acceptance. Food Science and Technology, 31(4), 905–910. [CrossRef]

- Hounhouigan, M. H., Linnemann, A. R., Soumanou, M. M., Van Boekel, M. A. J. S. (2014). Effect of Processing on the Quality of Pineapple Juice. Food Reviews International, 30(2), 112–133. [CrossRef]

- Yadav, B., Roopesh, M. S. Synergistically enhanced Salmonella Typhimurium reduction by sequential treatment of organic acids and atmospheric cold plasma and the mechanism study. Food Microbiology 104 (2022): 103976.

- Tosun, H., and Gonul, S. A. (205). The effect of acid adaptation conditions on acid tolerance response of Escherichia coli O157: H7.” Turkish Journal of Biology 29, no. 4:197-202. https://journals.tubitak.gov.tr/biology/vol29/iss4/2.

- Foster, J. W. 2000. Microbial responses to acid stress, p. 99–115. In G. Storz and R. Hengge-Aronis (ed.), Bacterial stress responses. ASM Press, Washington, DC.

- Adamovich, I., Baalrud, S.D., Bogaerts, A.; Bruggeman, P.J.; Cappelli, M. et al. (2017). The 2017 Plasma Roadmap: Low temperature plasma science and technology J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 50: 323001 (46pp). [CrossRef]

- Kondeti, V.S., Santosh K., Bruggeman, P.J. (2020). The interaction of an atmospheric pressure plasma jet with liquid water: dimple dynamics and its impact on crystal violet decomposition. Journal of Physics D: Applied Physics 54, no. 4: 045204.

- Ikawa, S., Kitano, K., Hamaguchi, S. (2010). Effects of pH on bacterial inactivation in aqueous solutions due to low-temperature atmospheric pressure plasma application. Plasma Processes and Polymers. Jan 14;7(1):33-42. [CrossRef]

- Misra, N. N., Ximena Yepez, Lei Xu, and Kevin Keener. (2019). In-package cold plasma technologies.” Journal of Food Engineering 244: 21-31. [CrossRef]

- Ghate, V., Kumar, A., Zhou, W., Yuk, H. G. (2015). Effect of organic acids on the photodynamic inactivation of selected foodborne pathogens using 461 nm LEDs. Food Control, 57, 333–340. [CrossRef]

- Oehmigen, K., Hähnel, M., Brandenburg, R., Wilke, C., Weltmann, K. D., & Von Woedtke, T. (2010). The Role of Acidification for Antimicrobial Activity of Atmospheric Pressure Plasma in Liquids. Plasma Processes and Polymers, 7(3–4), 250–257. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., Hollingsworth, R. I., Kasper, D. L. (1999). Ozonolytic depolymerization of polysaccharides in aqueous solution. Carbohydrate Research, 319(1–4), 141–147. [CrossRef]

- Ben’Ko, E. M., Manisova, O. R., Lunin, V. V. (2013). Effect of ozonation on the reactivity of lignocellulose substrates in enzymatic hydrolyses to sugars. Russian Journal of Physical Chemistry A, 87(7), 1108–1113. [CrossRef]

| Physiological state | SMAC agar | TAL Medium |

| NAA | 0.57 ± 0.12 Ax | 0.57 ± 0.06 Ax |

| AA | 3.03 ± 2.87 Ax | 3.43 ± 3.18 Ax |

| Physiological state | Time | Slope | y-intercept | R2 |

| NAA | 0.1 h | 0.06±0.55 | 0.056±0.05 | 0.154±0.097 |

| NAA | 24 h | 0.983±0.01 | 0.093±0.03a | 0.997±0.002 |

| AA | 0.1 h | 0.73±0.51 | 0.063±0.05 | 0.417±0.33 |

| AA | 24 h | 1.01±0.12 | 0.28±0.02a | 0.942±0.07 |

| pH | °Brix | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time (min) | pH; 0.1h | pH; 24h | ᵒBrix; 0.1h | ᵒBrix; 24h |

| 0 | 3.36±0.03 A,x | 3.36±0.03 A,x | 14.3±0.00 A,x | 14.5±0.00 A,y |

| 3 | 3.35±0.04 A,x | 3.35±0.02 A,x | 14.4±0.00 B,x | 14.5±0.00 A,y |

| 7 | 3.33±0.01 A,x | 3.34±0.01 A,x | 14.4±0.00 B,x | 14.5±0.00 A,y |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).