Submitted:

22 May 2024

Posted:

23 May 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

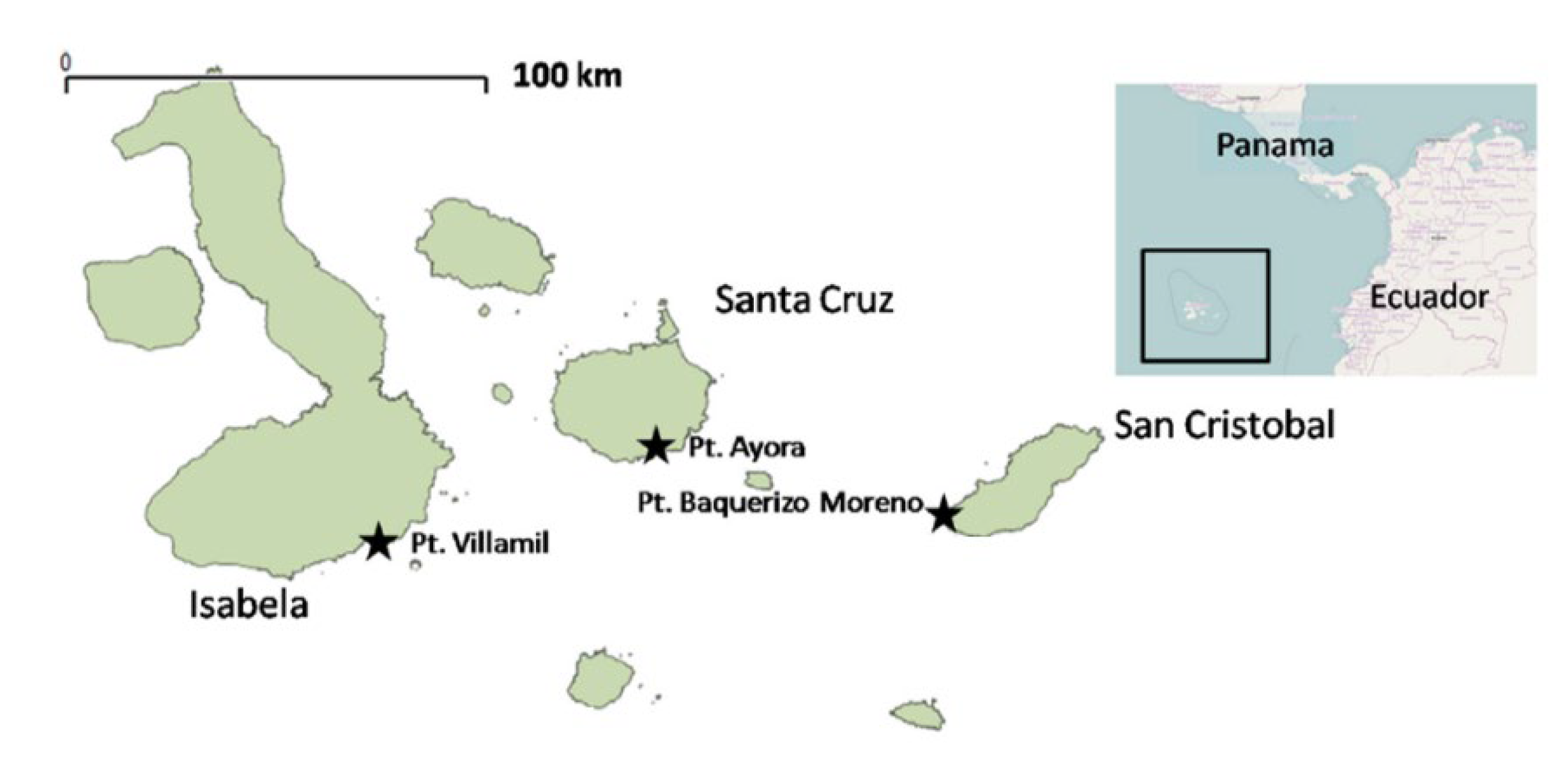

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Methodology

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Evaluation of Indicators

3.1.1. Management Body

3.1.2. Planning State

3.1.3. Public Participation

3.1.4. Implementation State

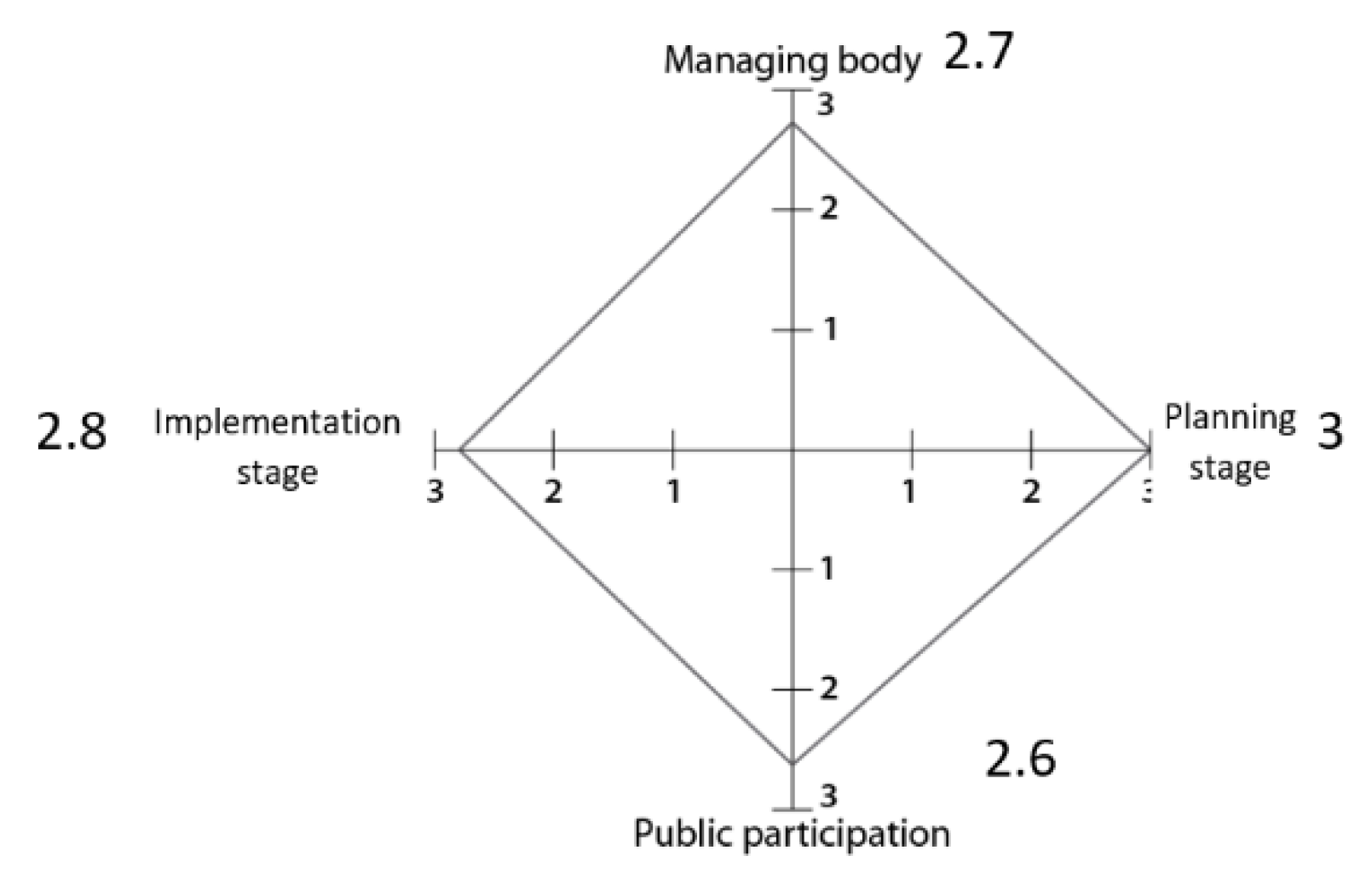

3.2. General Evaluation

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cifuentes, M.; Izurieta, A.; de Faria, H. Medición de la efectividad del manejo de áreas protegidas; Serie técnica. WWF, UICN y GTZ: Turrialba, Costa Rica, 2000; p. 105 pp. [Google Scholar]

- Maestro, M.; Pérez-Cayeiro, M.L.; Chica-Ruiz, J.A.; Reyes, H. Marine protected areas in the 21st century: Current situation and trends. Ocean & Coastal Management 2019, 171, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sala, E.; Lubchenco, J.; Grorud-Colvert, K.; Novelli, C.; Roberts, C.; Sumaila, U.R. Assessing real progress towards effective ocean protection. Marine Policy 2018, 91, 11–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, J. R.; Bradley, D.; Phipps, K.; Gleason, M.G. Beyond protection: Fisheries co-benefits of no-take marine reserves. Marine Policy 2020, 122, 104224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, M.; Kragt, M.E.; Hailu, A.; Langlois, T.J. Recreational fishers’ support for no-take marine reserves is high and increases with reserve age. Marine Policy 2018, 96, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buglass, S.; Reyes, H.; Ramirez-González, J.; Eddy, T.D.; Salinas-de-León, P.; Jarrin, J.M. Evaluating the effectiveness of coastal no-take zones of the Galapagos Marine Reserve for the red spiny lobster, Panulirus penicillatus. Marine Policy 2018, 88, 204–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sala, E.; Giakoumi, S. No-take marine reserves are the most effective protected areas in the ocean. ICES J. Marine Science 2017, 75, 1166–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, N.; Graziano, M.; Dimitrakopoulos, P.G. Social impacts of European Protected Areas and policy recommendations. Environmental Science & Policy 2020, 112, 134–140. [Google Scholar]

- Yates, K.L.; Clarke, B.; Thurstan, R.H. Purpose vs performance: What does marine protected area success look like? Environmental Science & Policy 2019, 92, 76–86. [Google Scholar]

- Sowman, M.; Sunde, J. Social impacts of marine protected areas in South Africa on coastal fishing communities. Ocean & Coastal Management 2018, 157, 168–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jentoft, S.; Pascual-Fernandez, J.; De la Cruz Modino, R.; Gonzalez-Ramallal, M.; Chuenpagdee, R. What stakeholders think about marine protected areas: case studies from Spain. Human Ecology 2012, 40, 185–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, B.; Johansson, F.; Blicharska, M. Socio-economic imipacts of marine conservation efforts in three Indonesian fishing communities. Marine Policy 2019, 103, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallol, S.; Goñi, R. Unintended changes of artisanal fisheries métiers upon implementation of an MPA. Marine Policy 2019, 101, 237–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinley, E.; Acott, T.; Yates, K.L. Marine social sciences: Looking towards a sustainable future. Environmental Science & Policy 2020, 108, 85–92. [Google Scholar]

- Zorondo-Rodríguez, F.; Díaz, M.; Simonetti-Grez, G.; Simonetti, J.A. Why would new protected areas be accepted or rejected by the public?: Lessons from an ex-ante evaluation of the new Patagonia Park Network in Chile. Land Use Policy 2019, 89, 104248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morea, J.P. A framework for improving the management of protected areas from a social perspective: The case of Bahía de San Antonio Protected Natural Area, Argentina. Land Use Policy 2019, 87, 104044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walton, A.; Gomei, M.; Di Carlo, G. Stakeholder Engagement: Participatory Approaches for the Planning and Development of Marine Protected Areas; World Wide Fund for Nature and NOAA-National Marine Sanctuary Program, Roma, Italia, 2013; 23 pp.

- Di Franco, A.; Thiriet, P.; Di Carlo, G.; Dimitriadis, C.; Francour, P.; Gutiérrez, N.L.; de Grissac, A.J.; Koutsoubas, D.; Milazzo, M.M.; Otero, M.; Piante, C.; Plass-Johnson, J.; Sainz-Trapaga, S.; Santarossa, L.; Tudela, S.; Guidetti, P. Five key attributes can increase marine protected areas performance for small-scale fisheries management. Scientific reports 2016, 6, 38135–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christie, P.; Bennett, N.J.; Gray, N.J.; Aulani, T.; Lewis, N.A.; Parks, J.; Ban, N.; Gruby, R.L.; Gordon, L.; Day, J.; Taei, S.; Friedlander, A.M. Why people matter in ocean governance: incorporating human dimensions into large-scale marine protected areas. Marine Policy 2017, 84, 273–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danulat, E. & Edgar, G. (eds.). Reserva Marina de Galapagos. Línea Base de la Biodiversidad. Fundación Charles Darwin, Servicio Parque Nacional Galapagos, Santa Cruz, Galapagos, Ecuador, 2022; 484 pp.

- Cerutti-Pereyra, F.; Moity, N.; Dureuil, M.; Ramírez-González, J.; Reyes, H.; Budd, K.; Marín, J.; Salinas-de-León, P. Artisanal longline fishing the Galapagos Islands–effects on vulnerable megafauna in a UNESCO World Heritage site. Ocean & Coastal Management 2020, 183, 104995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castrejón, M.; Defeo, O.; Reck, G.; Charles, A. Fishery Science in Galapagos: From a Resource-Focused to a Social–Ecological Systems Approach. In The Galapagos Marine Reserve. Social and Ecological Interactions in the Galapagos Islands, 1st ed.; Denkinger, J., Vinueza, L., Eds.; Springer: New York, U.S.A, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castrejón, M.; Moity, N.; Charles, A. The bumpy road to conservation: Challenges and opportunities in updating the Galapagos zoning system. Marine Policy 2024, 163, 106146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caceres, R.; Pittman, J.; Castrejón, M.; Deadman, P. The Galapagos small-scale fishing sector collaborative governance network: Structure, features and insights to bolster its adaptive capacity. Regional Studies in Marine Science 2023, 59, 102800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, L.A.; Stier, A.C.; Fietz, K.; Montero, I.; Gallagher, A.J.; Bruno, J.F. Illegal shark fishing in the Galapagos Marine Reserve. Marine Policy 2013, 39, 317–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuhbauer, A.; Koch, V. Assessment of recreational fishery in the Galapagos Marine Reserve: Failures and opportunities. Fisheries Research 2013, 144, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burbano, D.V.; Valdivieso, J.C.; Izurieta, J.C.; Meredith, T.C.; Ferri, D.Q. “Rethink and reset” tourism in the Galapagos Islands: Stakeholders’ views on the sustainability of tourism development. Annals of Tourism Research Empirical Insights 2022, 3(2), 100057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mestanza-Ramón, C.; Chica-Ruiz, J.A.; Anfuso, G.; Mooser, A.; Botero, C.M.; Pranzini, E. Tourism in Continental Ecuador and the Galapagos Islands: An Integrated Coastal Zone Management (ICZM) Perspective. Water 2020, 12, 1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, A. La contradicción del turismo en la conservación y el desarrollo en Galapagos-Ecuador. Estudios y perspectivas en turismo 2015, 24(2), 399-413. https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=5215615.

- Mejía, C.; Brandt, S. Managing tourism in the Galapagos Islands through Price incentives: A choice experiment approach. Ecological Economics 2015, 117, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alencastro, L.A.; Carvache-Franco, M.; Carvache-Franco, W. Preferences of Experiential Fishing Tourism in a Marine Protected Area: A Study in the Galapagos Islands, Ecuador. Sustainability 2023, 15(2), 1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, A. The crossroads of ecotourism dependency, food security and a global pandemic in Galápagos, Ecuador. Sustainability 2021, 13(23), 13094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, P.J.S. A governance analysis of the Galapagos Marine Reserve. Marine Policy 2013, 41, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castrejón, M.; Charles, A. Improving fisheries co-management through ecosystem-based spatial management: the Galapagos Marine Reserve. Marine Policy 2013, 38, 235–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heylings, P.; Bravo, M. Evaluating governance: A process for understanding how co-management is functioning, and why, in the Galapagos Marine Reserve. Ocean & Coastal Management 2007, 50, 174–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salas Zapata, W.; Ríos Osorio, L.; Álvarez, J. Bases conceptuales para una clasificación de los sistemas socioecológicos de la investigación en sostenibilidad. Revista Lasallista de Investigación 2012, 8, 136–142. [Google Scholar]

- Sena, N.; Veiga, A.; Semedo, A.; Abu-Raya, M.; Semedo, R.; Fujii, I.; Makino, M. Co-Designing Protected Areas Management with Small Island Developing States’ Local Stakeholders: A Case from Coastal Communities of Cabo Verde. Sustainability 2023, 15(20), 15178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benítez-Capistros, F.; Hugé, J.; Koedam, N. Environmental impacts on the Galapagos Islands: Identification of interactions, perceptions and steps ahead. Ecological Indicators 2014, 38, 113–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, R.; Longnecker, N.; Schmidt, L.; Clifton, J. Marine Conservation in remote small island settings: Factors influencing marine protected area establishment in the Azores. Marine Policy 2013, 40, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arévalo-Valenzuela, P. , Peña-Cortés, F. & Pincheira-Ulbrich, J. Ecosystem services and uses of dune systems of the coast of the Araucanía Region, Chile: A perception study. Ocean & Coastal Management 2021, 200, 105450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballarini, E.; D’Adamo, R.; Pazienza, G.; Zaggia, L.; Vafeidis, A. Assessing the applicability of a bottom-up or top-down approach for effective management of a coastal lagoon area. Ocean & Coastal Management 2021, 200, 105417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, A.; Seixas, S.; Marques, J.C. Bottom-up management approach to coastal marine protected areas in Portugal. Ocean & Coastal Management 2015, 118, 275–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowel, C.; Bissett, C.; Ferreira, S.M. Top-down and bottom-up processes to implement biological monitoing in protected areas. Journal of Environmental Management 2020, 257, 109998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pomeroy, R.S.; Parks, J.E.; Watson, L.M. Cómo evaluar una AMP. Manual de Indicadores Naturales y Sociales para Evaluar la Efectividad de la Gestión de Áreas Marinas Protegidas. UICN: Gland, Suiza and Cambridge, Reino Unido, 2006; XVI + 216 pp.

- Ervin, J. WWF: Rapid Assessment and prioritization of Protected Area Management (RAPPAM) Methodology. WWF: Gland, Switzerland, 2003.

- Stolton, S.; Hockings, M.; Dudley, N.; MacKinnon, K.; Whitten, T.; Leverington, F. Reporting Progress in Protected Areas. A Site-Level Management Effectiveness Tracking Tool, 2nd ed. World Bank, WWF: Gland, Switzerland, 2007.

- Hockings, M.; Stolton, S.; Courrau, J.; Dudley, N.; Parrish, J.; James, R.; Mathur, V.; Makombo, J. The World Heritage Management Effectiveness Workbook: 2007 Edition. UNESCO, IUCN, University of Queensland, The Nature Conservancy: Queensland, Australia, 2007; 105 pp. https://www.cbd.int/doc/pa/tools/iucn-tnc-2007-02-en.pdf.

- Pomeroy, R.S.; Parks, J.E.; Watson, L.M. How is your MPA doing? A Guidebook of Natural & Social Indicators for Evaluating Marine Protected Area Management Effectiveness. IUCN, WWF, US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration: Gland and Cambridge, 2004.

- ICMBio (Instituto Chico Mendes de Conservação da Biodiversidade). Relatório de aplicação do sistema de análise e monitoramento de gestão SAMGe - Ciclo 2020. MMA: Brasilia, Brasil, 2021; 138 pp.

- Bennett, N.J.; Di Franco, A.; Calò, A.; Nethery, E.; Niccolini, F.; Milazzo, M.; Guidetti, P. Local support for conservation is associated with perceptions of good governance, social impacts, and ecological effectiveness. Conservation letters 2019, 12(14), e12640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Cintio, A.; Niccolini, F.; Scipioni, S.; Bulleri, F. Avoiding “Paper Parks”: A Global Literature Review on Socioeconomic Factors Underpinning the Effectiveness of Marine Protected Areas. Sustainability 2023, 15(5), 4464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzo, D.; Cavallini, I.; Scaccia, L.; Guidetti, P.; Di Franco, A.; Calò, A.; Niccolini, F. Drivers of Small-Scale Fishers’ Acceptability across Mediterranean Marine Protected Areas at Different Stages of Establishment. Sustainability 2023, 15(11), 9138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muccitelli, S.; Pozzi, C.; D’Ascanio, R.; Magaudda, S. Environmental Contract: A Collaborative Tool to Improve the Multilevel Governance of European MPAs. Sustainability 2023, 15(10), 8174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Franco, A.; Hogg, K.E.; Calo, A.; Bennett, N.J.; Sévin-Allouet, M.A.; Alaminos, O.E.; Lang, M.; Koutsoubas, D.; Prvan, M.; Santarossa, L.; Niccolini, F.; Milazzo, M.; Guidetti, P. Improving marine protected area and governance through collaboration and co-production. Journal of Environmental Management 2020, 269, 110757–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gill, D.A.; Mascia, M.B.; Ahmadia, G.N.; Glew, L.; Lester, S.E.; Barnes, M.; Craigie, I.; Darling, E.; Free, C.; Geldman, J.; Holst, S.; Jensen, O.; White, A.; Basurto, A.; Coad, L.; Gated, R.; Guannel, G.; Mumby, P.; Thomas, H.; Whitmee, S.; Woodley, S.; Fox, H. Capacity shortfalls hinder the performance of marine protected areas globally. Nature 2017, 543(7647), 665-669. https://www.nature.com/articles/nature21708.

- DPNG (Dirección del Parque Nacional Galápagos). Plan de Manejo de las Áreas Protegidas de Galapagos para el Buen Vivir. Ministerio del Ambiente: Puerto Ayora, Galapagos, Ecuador, 2014; 209 pp.

- Maestro, M.; Chica-Ruiz, J.A.; Pérez-Cayeiro, M.L. Analysis of marine protected area management: The Marine Park of the Azores (Portugal). Marine Policy 2020, 119, 104104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MAATE (Ministerio del Ambiente, Agua y Transición Ecológica). Plan de Manejo de la Reserva Marina Hermandad. Dirección del Parque Nacional Galápagos. Subsecretaría de Patrimonio Natural. Fundación de Conservación Jocotoco, Puerto Ayora, Galapagos, Ecuador, 2023.

- Maestro, M.; Pérez-Cayeiro, M.L.; Morales-Ramírez, A.; Chica-Ruiz, J.A. Evaluation of the management of marine protected areas. Comparative study in Costa Rica. Journal of Environmental Management 2022, 308, 114633–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maestro, M.; Chica-Ruiz, J.A.; Popović Perković, Z.; Pérez-Cayeiro, M.L. Marine protected areas management in the Mediterranean Sea. The case of Croatia. Diversity 2022, 14(6), 448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coad, L.; Leverington, F.; Knights, K.; Geldmann, J.; Eassom, A.; Kapos, V.; Kingston, N.; de Lima, M.; Zamora, C.; Cuardros, I.; Nolte, C.; Burgess, N.D.; Hockings, M. Measuring impact of protected area management interventions: current and future use of the Global Database of Protected Area Management Effectiveness. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 2015, 370, 20140281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gillespie, A. PESTEL analysis of the macro-environment. Foundations of Economics. Additional Chapter on Bussiness Strategy. Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2007.

- Licha, I. La construcción de escenarios: herramienta de la gerencia social. Banco Interamericano de Desarrollo, Instituto Interamericano para el Desarrollo (INDES), 2000; 11 pp. http://ibcm.blog.unq.edu.ar/wp-content/uploads/sites/28/2018/04/Licha-2000.pdf.

- Nygrén, N.A. Scenario workshops as a tool for a participatory planning in a case of lake management. Futures 2019, 107, 29–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burbano, D.; Meredith, T.; Mulrennan, M. Exclusionary decision-making processes in marine governance: The rezoning plan for the protected áreas of the ‘iconic’ Galapagos Islands, Ecuador. Ocean & Coastal Management 2020, 185, 105066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scianna, C.; Niccolini, F.; Giakoumi, S.; Di Franco, A.; Gaines, S.; Bianchi, C.; Scaccia, L.; Bava, S.; Cappanera, V.; Charbonnel, E.; Culioli, J.M.; Di Carlo, G.; De Franco, F.; Cimitriadis, C.; Panzalis, P.; Santoro, P.; Guidetti, P. Organization Science improves management effectiveness of Marine Protected Areas. Journal of Environmental Science 2019, 240, 285–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llerena, E.; Quisingo, T.; Maldonado, R. Analysis of agreements reached in the Participatory Management Board 2010-2015. Galapagos Report 2015-2016. GNPD 105, 111, 2017.

- Erazo, C. (2005). Informe final: Entre el conflicto y la colaboración: El manejo participativo en la Reserva Marina de Galápagos. Fundar Galápagos, Puerto Ayora, Ecuador. http://hdl.handlenet/10625/32669. 1062. [Google Scholar]

- Burbano, D.V.; Meredith, T.C. Conservation strategies through the lens of small-scale fishers in the Galapagos Islands, Ecuador: perceptions underlying local resistance to marine planning. Society & Natural Resources 2020, 33(10), 1194-1212.

- Steinvorth, K. Evaluación integral del impacto de los bienes y servicios ecosistémicos provistos por el Parque Nacional Marino Ballena sobre las estrategias y medios de vida locales. Centro Agronómico Tropical de Investigación y Enseñanza, Escuela de Posgrado: Turrialba, Costa Rica, 2012.

- Hind, E.J.; Hiponia, M.C.; Gray, T.S. From community - based to centralised national management - a wrong turning for the governance of the marine protected area in Apo Island, Philippines. Marine Policy 2010, 34, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barragán-Paladines, M.J.; Chuenpagdee, R. A step zero analysis of the Galapagos Marine Reserve. Coastal Management 2017, 45(5), 339–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emslie, M.; Logan, M.; Williamson, D.; Ayling, A.; MacNeil, M.; Ceccarelli, D.; Cheal, A.; Evans, R.; Johns, K.; Jonker, M.; Miller, I.; Osborne, K.; Russ, G.; Sweatman, H. Expectations and outcomes of reserve network performance following re-zoning of the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park. Current Biology 2015, 25(8), 983–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pazmiño, A.; Serrao-Neumann, S.; Low Choy, D. Towards comprehensive policy integration for the sustainability of small islands: A landscape-scale planning approach for the Galápagos Islands. Sustainability 2018, 10(4), 1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, K.; Murchie, A.; Kerr, V.; Lundquist, C. The evolution of marine protected area planning in Aotearoa New Zeland: Reflections on participation and process. Marine Policy 2018, 93, 113–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, F.; Pazmiño, C.; Calvopiña, M. Propuesta del Plan de Monitoreo para la zonificación de las Áreas Protegidas de Galapagos. Conservación Internacional: Puerto Ayora, Ecuador, 2018.

- De Andrés, M.; Barragán, J.; García, J. Ecosystem services and urban development in coastal Social-Ecological Sustem: The Bay of Cádiz case study. Ocean & Coastal Management, 2018; 154, 155–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, J.M.; de Castro Dias, T.C.; da Cunha, A.C.; Cunha, H.F. Funding deficits of protected areas in Brazil. Land Use Policy 2021, 100, 104926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarker, S.; Rahman, M.; Yadav, A.; Islam, M. Zoning of marine protected areas for biodiversity conservation in Bangladesh through socio-spatial data. Ocean & Coastal Management 2019, 173, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, N.J.; Teh, L.; Ota, Y.; Christie, P.; Ayers, A.; Day, J.C.; Franks, P.; Gill, D.; Gruby, R.L.; Kittinger, J.N.; Koehn, J.Z.; Lewis, N.; Parks, J.; Vierros, M.; Whitty, T. S.; Wilhelm, A.; Wright, K.; Aburto, J.A.; Finkbeiner, E.M.; Gaymer, C.F.; Govan, H.; Gray, N.; Jarvis, R.M.; Kaplan-Hallam, M.; Satterfield, T. An appeal for a code of conduct for marine conservation. Marine Policy 2017, 81, 411–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, J.C. Effective public participation is fundamental for marine conservation-lessons from a large-scale MPA. Coastal Management 2017, 45(6), 470–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noble, M. , Harasti, D., Pittock, J. & Doran B. Linking the social to the ecological using GIS methods in marine spatial planning and management to support resiliente: A review. Marine Policy 2019, 108, 103657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora, N. y Bernales, M. Guía práctica para el abordaje de conflictos en el sector pesquero artesanal. Informe especializado; WWF: Lima, Perú, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Mills, M.; Magris, R.A.; Fuentes, M.P.B.; Bonaldo, R.; Herbst, D.F.; Limaf, M.C.S.; Kerber, I. K,G.; Gerhardinger, L.C.; de Mourai, R.L.; Domitj, C.; Teixeira, J.B.; Pinheirol, H.T.; Vianna, G.M.S., Rodrigues de Freitas, R. Opportunities to close the gap between science and practice for Marine Protected Areas in Brazil. Perspectives in Ecology and Conservation 2020, 18, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, T. , Kerry, J., Alvarez-Noriega, M., Alvarez-Romero, J., Anderson, K., Baird, A., Babcock, R. et al. Global warming and recurrent mass bleaching of corals. Nature 2017, 543, 37–377. [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers, K.S. , Bahr, K.D., Jokiel, P.L. & Donà, A.R. Patterns of bleaching and mortality following widespread warming events in 2014 and 2015 at the Hanauma Bay Nature Preserve, Hawai‘i. PeerJ 2017, 5, e3355.10. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, C.M. , O’Leary, B.C., McCauley, D.J., Cury, P.M., Duarte, C.M., Lubchenco, J., Pauly, D., Sáenz-Arroyo, A., Sumaila, U.R., Wilson, R.W., Worm, B. & Castilla, J.C. Marine reserves can mitigate and promote adaptation to climate change. PNAS 2017, 114, 6167–6175. [Google Scholar]

| Name | Year | Characteristics | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rapid Assessment and Prioritization of Protected Area Management | 2003 | Identifying strengths and weaknesses of management in networks of protected areas, comparing the management of different places.razmakIt is the most commonly used today | [45] |

| Management Effectiveness Tracking Tool | 2007 | To evaluate the progress of management in an individual protected area over time. The Marine Score-Card evaluation is an adaptation of this methodology for MPAs | [46] |

| Enhancing our Heritage | 2007 | It was originally designed for adaptive management in Natural World Heritage sites.razmakIt is a more exhaustive methodology than the previous two, and therefore provides more detailed results. | [47] |

| How is your MPA doing? | 2004 | Evaluating the management of MPAs, prioritizing actions and strengthening support. | [48] |

| Sistema de Análise e Monitoramento de Gestão | 2016 | It is a methodology for evaluating and monitoring the management of protected areas, with quick application and immediate results. It is composed of two main elements: evaluative characterization and analysis of management instruments. | [49] |

| Key management aspect | Indicator | Evaluation | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Management body | 1. Background of the staff | 1 | Without basic training or education. |

| 2 | Higher education: only natural sciences. | ||

| 3 | Higher education: multidisciplinary team (natural and social sciences). | ||

| 2. Technical training offered to staff | 1 | No, or sporadically. | |

| 2 | Yes. | ||

| 3 | It also anticipates future needs. | ||

| 3. MPA staff participation in the planning processes | 1 | No. | |

| 2 | Sporadic. | ||

| 3 | In all planning processes. | ||

| 4. MPA staff have the necessary procedures to participate in the planning processes | 1 | No. | |

| 2 | It has some procedures, sometimes insufficient. | ||

| 3 | Yes. | ||

| 5. Cooperation with other institutions at the local levelrazmak | 1 | No. | |

| 2 | Not with all institutions or not on a regular basis. | ||

| 3 | It exists on a regular basis with all institutions. | ||

| 6. Cooperation with other institutions at the regional level | 1 | No. | |

| 2 | Not with all institutions or not on a regular basis. | ||

| 3 | It exists on a regular basis with all institutions. | ||

| 7. Cooperation with other institutions at the international levelrazmak | 1 | No. | |

| 2 | Not on a regular basis. | ||

| 3 | It exists on a regular basis, with a large number of institutions. | ||

| 8 Collaboration and exchange of knowledge with other international projects/programmes | 1 | No. | |

| 2 | Not on a regular basis. | ||

| 3 | It exists on a regular basis, with a large number of projects/programmes. | ||

| Planning stage | 9. Management plan | 1 | No. |

| 2 | Not implemented, or only partially implemented. | ||

| 3 | It exists, is updated, is fully implemented, and has an established schedule for regular reviews and updates. | ||

| 10. Strategies and management measures identified with the management objectives | 1 | They do not exist or are not related to the objectives. | |

| 2 | They exist partly in relation to the objectives. | ||

| 3 | They exist and are completely identified with the objectives. | ||

| 11. Operational Plan | 1 | No. | |

| 2 | Partially implemented. | ||

| 3 | Fully implemented. | ||

| 12. Ecosystem diagnosis carried out prior to the development of the management plan | 1 | No. | |

| 2 | Not available to interested parties. | ||

| 3 | Yes, and it is published or available. | ||

| 13. The MPA integrated into an MPA network | 1 | No. | |

| 2 | It’s in the process of being integrated. | ||

| 3 | Yes. | ||

| Public participation | 14. Public participation in the process of developing the management plan | 1 | There was or is no management plan. |

| 2 | Yes. | ||

| 3 | Yes, at all stages of the development of the management plan and participation is foreseen for the evaluation of the management plan. | ||

| 15. Representative public participation in the process of developing the management plan | 1 | There was no management plan, it was not representative or there is no management plan. | |

| 2 | Only the priority groups were represented. | ||

| 3 | Both primary and secondary users were represented. | ||

| 16. Social actors participation in management decision making or planning processes | 1 | No. | |

| 2 | Through consultation | ||

| 3 | Interactive participation with a direct impact on decision making | ||

| 17. Collegiate body for participationrazmak | 1 | No. | |

| 2 | Is not representative and/or does not function properly. | ||

| 3 | It exists, it is representative and it works properly. | ||

| 18. Communication between stakeholders and managers | 1 | Very little or none. | |

| 2 | Not within an established programme. | ||

| 3 | A communication programme is being implemented to build stakeholder support for the MPA. | ||

| 19. Sustainability education activities | 1 | No. | |

| 2 | Sporadically. | ||

| 3 | On a regular basis and with wide participation. | ||

| 20. Volunteer or environmental communication activitiesrazmak | 1 | No. | |

| 2 | Sporadically. | ||

| 3 | On a regular basis and with wide participation. | ||

| 21. MPA information available to stakeholders and the general public | 1 | No. | |

| 2 | Part is available upon request to the park management. | ||

| 3 | It is available on the website, available to any interested party. | ||

| Implementation stage | 22. Zoning of the MPArazmak | 1 | It does not exist for the use or conservation of resources. |

| 2 | It exists for use and conservation, but it is only partially functional or outdated. | ||

| 3 | It exists updated, with measures and concrete uses for each zone. | ||

| 23. Budget allocated for the management of the MPA is adequaterazmak | 1 | This information is not accessible. | |

| 2 | The budget guarantees the costs of the administration and surveillance staff and the means necessary for management (vehicles, equipment, fuel, etc.). | ||

| 3 | The budget also allows for other innovative activities such as: research, development, etc. | ||

| 24. Monitoring and evaluation of biophysical, socio-economic and governance indicators | 1 | No. | |

| 2 | It does not follow a strategy or regular collection of results, which are not systematically used for management. | ||

| 3 | There is a good system of monitoring and evaluation, which is well implemented and used in adaptive management. | ||

| 25. Scientific information integrated into MPA management | 1 | No. | |

| 2 | In some cases. | ||

| 3 | It serves to evaluate and improve the management of the MPA. | ||

| 26. The MPA considered a socio-ecosystem | 1 | No. | |

| 2 | The social system is an important factor, but the natural system is a priority. | ||

| 3 | It is considered and taken into account throughout the process. | ||

| Topics | Sources |

|---|---|

| Trainings | [46,47,61] |

| Planning tools | [61] |

| Management plans | [46,47,61,62] |

| Operative plans | [46,47] |

| Public participation | [47,61] |

| Collegiate bodies | [62] |

| Comunication | [46,47,61,62] |

| Environmental education | [47,61] |

| Volunteer | [47] |

| Information | [62] |

| Budget | [47,61] |

| Monitoring | [47,61] |

| Scientific knowledge | [46,47,62] |

| Type of management | Rating | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Management body | Planning stage | Public participation | Implementation stage | |

| Proactive | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Learning | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Interactive | 1,2 | 1,2,3 | 3 | 1,2,3 |

| Centralized | 3 | 1,2,3 | 1,2 | 1,2,3 |

| Formal* | 1,2 | 1,2 | 1,2 | 1,2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).