Submitted:

23 May 2024

Posted:

24 May 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

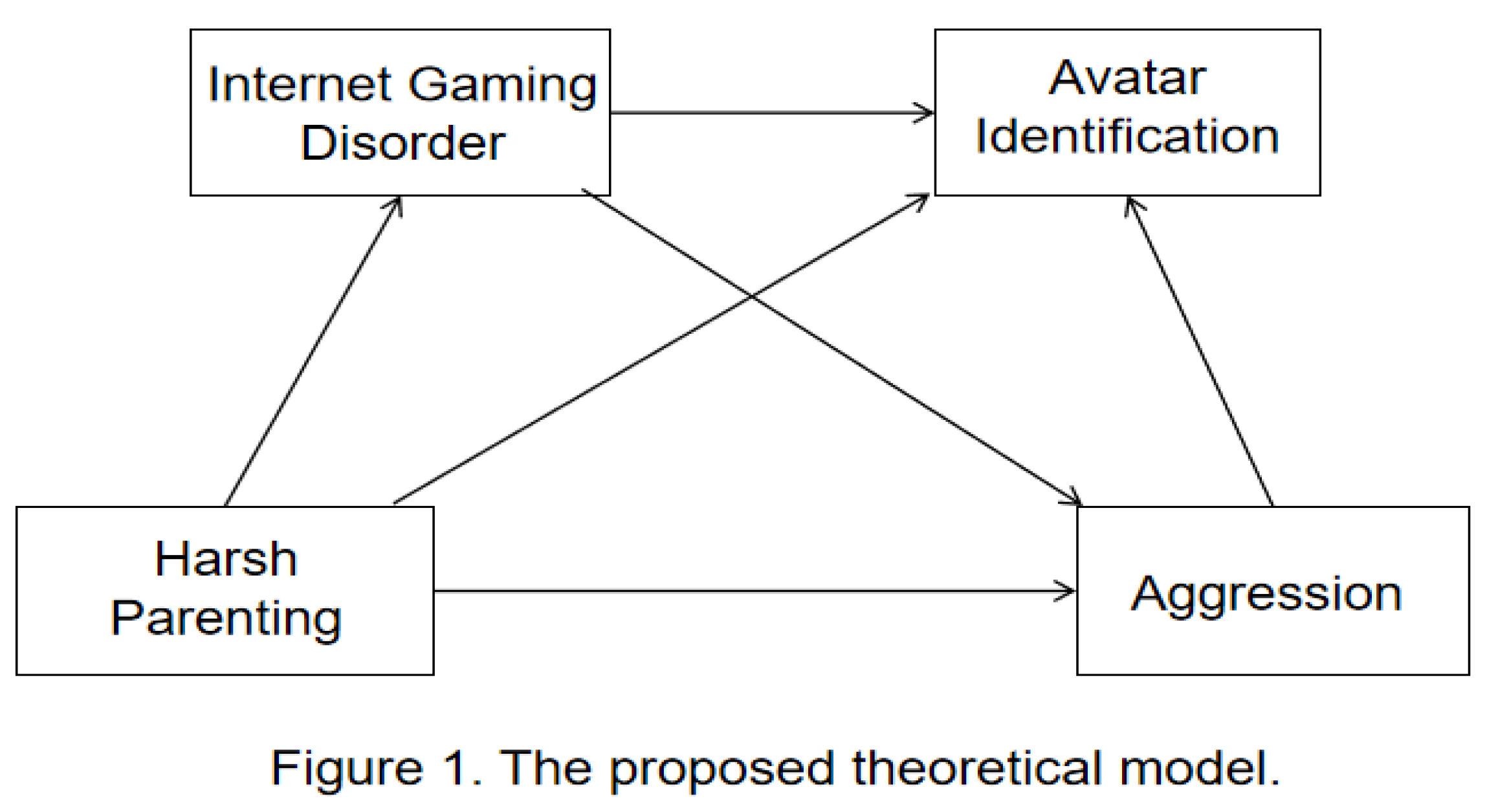

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Common Methodological Biases

3.2. Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

3.3. Tests for Mediating Effects

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- He, Y.; Li, H.; Feng, L. The Development of High-School students' Aggressiveness. Psychological Development and Education. 2006, (02), 57-63.

- Thomaes, S.; Bushman, B. J.; Stegge, H.; Olthof, T. Trumping shame by blasts of noise: Narcissism, self-esteem, shame, and aggression in young adolescents. Child development. 2008, 79(6), 1792-1801. [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Zhang, L. Chain mediating effect of regulatory emotional self-efficacy and self-control between self-esteem and aggressiveness in adolescents.Chinese Mental Health Journal. 2018, (07), 574-579.

- Bandura, A. Social learning theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall. 1976.

- Wang, M.; Du, X.; Zhou, Z. Harsh parenting: Meaning, influential factors and mechanisms. Advances in Psychological Science. 2016, (03), 379-391. [CrossRef]

- Miao, T.; Wang, J.; Song, G. Harsh Parenting and Adolescents' Depression:A Moderated Mediation Model. Chinese Journal of Special Education. 2018, (06), 71-77.

- Shan, Z.; Deng, G.; Li, J.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, Q. Correlational analysis of neck/shoulder pain and low back pain with the use of digital products, physical activity and psychological status among adolescents in Shanghai. Plos one. 2013, 8(10), e78109. [CrossRef]

- Cole, D. A.; Martin, N. C.; Sterba, S. K.; Sinclair-McBride, K.; Roeder, K. M.; Zelkowitz. R.; Bilsky, S. A. Peer victimization (and harsh parenting) as developmental correlates of cognitive reactivity, a diathesis for depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2014, 123(2), 336. [CrossRef]

- Hinnant, J. B.; Erath, S. A.; El-Sheikh, M. Harsh parenting, parasympathetic activity, and development of delinquency and substance use. Journal of abnormal psychology. 2015, 124(1), 137. [CrossRef]

- Surjadi, F. F.; Lorenz, F. O.; Conger, R. D.; Wickrama, K. A. S. Harsh, inconsistent parental discipline and romantic relationships: mediating processes of behavioral problems and ambivalence. Journal of family psychology. 2013, 27(5), 762. [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.; Ma, S.; Fang, Z.; Xu, B.; Liu, H. The Latent Classes of Parenting Style: An Application of Latent Profile Analysis. Studies of Psychology and Behavior. 2016, 14(4), 523.

- Callahan, K. L.; Scaramella, L. V.; Laird, R. D.; Sohr-Preston, S. L. Neighborhood disadvantage as a moderator of the association between harsh parenting and toddler-aged children's internalizing and externalizing problems. Journal of Family Psychology. 2011, 25(1), 68. [CrossRef]

- Pineda, A. Q.; Cole, D. A.; Bruce, A. E. Mother-adolescent interactions and adolescent depressive symptoms: A sequential analysis. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 2007, 24(1), 5-19. [CrossRef]

- Knappe, S.; Beesdo, K.; Fehm, L.; Höfler, M.; Lieb, R.; Wittchen, H. U. Do parental psychopathology and unfavorable family environment predict the persistence of social phobia?. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2009, 23(7), 986-994. [CrossRef]

- Knappe, S.; Beesdo, K.; Fehm, L.; Lieb, R.; Wittchen, H. U. Associations of familial risk factors with social fears and social phobia: evidence for the continuum hypothesis in social anxiety disorder?. Journal of Neural Transmission. 2009, 116, 639-648. [CrossRef]

- Kim-Spoon, J.; Cicchetti, D.; Rogosch, F. A. A longitudinal study of emotion regulation, emotion lability-negativity, and internalizing symptomatology in maltreated and nonmaltreated children. Child development. 2013, 84(2), 512-527. [CrossRef]

- Lansford, J. E.; Criss, M. M.; Laird, R. D.; Shaw, D. S.; Pettit, G. S.; Bates, J. E.; Dodge, K. A. Reciprocal relations between parents' physical discipline and children's externalizing behavior during middle childhood and adolescence. Development and psychopathology. 2011, 23(1), 225-238. [CrossRef]

- Gustafsson, H. C.; Cox, M. J.; Blair, C. Maternal parenting as a mediator of the relationship between intimate partner violence and effortful control. Journal of Family Psychology. 2012, 26(1), 115. [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Shi, Z. The Psychological Factors and Treatment of School Bullying. Journal of East China Normal University(Educational Sciences). 2017, (02), 51-56+119. [CrossRef]

- Wang, M. Harsh parenting and peer acceptance in Chinese early adolescents: Three child aggression subtypes as mediators and child gender as moderator. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2017, 63, 30-40. [CrossRef]

- Brody, G. H.; Yu, T.; Beach, S. R.; Kogan, S. M.; Windle, M.; Philibert, R. A. Harsh parenting and adolescent health: a longitudinal analysis with genetic moderation. Health Psychology. 2014, 33(5), 401. [CrossRef]

- Wei, H.; Zhou, Z.; Tian, Y.; Bao, N. Online Game Addiction:Effects and Mechanisms of Flow Experience. Psychological Development and Education. 2012, (06), 651-657. [CrossRef]

- CHINA INTERNET NETWORK INFORMATION CENTER. (2023). 52nd Statistical Report on Internet Development in China. https://www3.cnnic.cn/n4/2023/0828/c88-10829.html.

- Zhang, Y.; Yu, C.; Zhang, W. Psychosocial and Social Factors of Adolescent's Internet Gaming Disorder. China Journal of Health Psychology. 2017, (07), 1058-1061. [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Huang, S.; Chen, Z.; Xu, N.; Hou, X. Relationship between cognitive reappraisal and Internet gaming disorder of adolescents:Mediating role of self-esteem. China Journal of Health Psychology. 2022, (09), 1350-1354. [CrossRef]

- Su, B.; Yu, C.; Zhang, W.; Su, Q.; Zhu, J.; Jiang, Y. Father–child longitudinal relationship: Parental monitoring and Internet gaming disorder in Chinese adolescents. Frontiers in Psychology. 2018, 9, 334311. [CrossRef]

- Qi, D.; Lin, Y.; Liu, Q. Smartphone Addiction out of"Beating" ? TheEffect of Harsh Parenting on Smartphone Addiction of Adolescents. Psychological Development and Education. 2020, (06), 677-685. [CrossRef]

- Wei, H.;Zhu, L.; Chen, W.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, X. Effect Of Harsh Parenting On Smartphone Addiction:From The Perspective Of Experience Avoidance Model. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2021, (03), 501-505. [CrossRef]

- Deng, L.; Liu, X.; Tang, Y.; Yang, M.; Li, B. Parental Psychological Control,Autonomous Support and Adolescent lnternet Gaming Disorder:The Mediating Role of Impulsivity. Chinese Mental Health Journal. 2021, (02), 316-322. [CrossRef]

- Bonnaire, C.; Phan, O. Relationships between parental attitudes, family functioning and Internet gaming disorder in adolescents attending school. Psychiatry Research. 2017, 255, 104-110. [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Liu, Q.; Yu, S.; Zhou, Z. The Relationship between Parents Neglect and Online Gaming Addiction among Adolescents: The Mediating Role of Hope and Gender Difference.Psychological Development and Education. 2021, (01), 109-119. [CrossRef]

- Xi, W.; Hu, Y. lnternet Gaming Disorder in Adolescents: Review and Prospect. Chinese Journal of Applied Psychology. 2022, (01),3-19.

- Kim, E. J.; Namkoong, K.; Ku, T.; Kim, S. J. The relationship between online game addiction and aggression, self-control and narcissistic personality traits. European psychiatry. 2008, 23(3), 212-218. [CrossRef]

- Mehroof, M.; Griffiths, M. D. Online gaming addiction: The role of sensation seeking, self-control, neuroticism, aggression, state anxiety, and trait anxiety. Cyberpsychology, behavior, and social networking. 2010, 13(3), 313-316. [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Niu, Y.; Wen, G. The Influence of Short-time Prosocial Video Games on Aggressive Behaviors of Primary School Children. Chinese Journal of Applied Psychology. 2016, (03),218-226.

- Duan, D.; Zhang, X.; Wei, L.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, C. The lmpact of Violent Media on Aggression——The Role of Normative Belief and Empathy. Psychological Development and Education. 2014, (02), 185-192. [CrossRef]

- Heng, S.; Zhou, Z.; Sun, L. The avatar identification in video games. Advances in Psychological Science. 2017, (09), 1565-1578.

- Lewis, M. L.; Weber, R.; Bowman, N. D. “They may be pixels, but they're MY pixels:” Developing a metric of character attachment in role-playing video games. CyberPsychology & Behavior. 2008, 11(4), 515-518. [CrossRef]

- Gentile, D. A.; Saleem, M.; Anderson, C. A. Public policy and the effects of media violence on children. Social Issues and Policy Review. 2007, 1(1), 15-61. [CrossRef]

- Fischer, P.; Kastenmüller, A.; Greitemeyer, T. Media violence and the self: The impact of personalized gaming characters in aggressive video games on aggressive behavior. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2010, 46(1), 192-195. [CrossRef]

- Hollingdale, J.; Greitemeyer, T. The changing face of aggression: The effect of personalized avatars in a violent video game on levels of aggressive behavior. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 2013, 43(9), 1862-1868. [CrossRef]

- Ganesh, S.; van Schie, H. T.; de Lange, F. P.; Thompson, E.; Wigboldus, D. H. How the human brain goes virtual: Distinct cortical regions of the person-processing network are involved in self-identification with virtual agents. Cerebral cortex. 2012, 22(7), 1577-1585. [CrossRef]

- Klimmt, C.; Hefner, D.; Vorderer, P. The video game experience as “true” identification: A theory of enjoyable alterations of players’ self-perception. Communication theory. 2009, 19(4), 351-373. [CrossRef]

- Smahel, D.; Blinka, L.; Ledabyl, O. Playing MMORPGs: Connections between addiction and identifying with a character. Cyberpsychology & behavior. 2008, 11(6), 715-718. [CrossRef]

- Soutter, A. R. B.; Hitchens, M. The relationship between character identification and flow state within video games. Computers in human behavior. 2016, 55, 1030-1038. [CrossRef]

- Trepte, S.; Reinecke, L. Avatar creation and video game enjoyment: Effects of life-satisfaction, game competitiveness, and identification with the avatar. Journal of Media Psychology. 2010, 22, 171–184. [CrossRef]

- Anderson, C. A.; Bushman, B. J. Effects of violent video games on aggressive behavior, aggressive cognition, aggressive affect, physiological arousal, and prosocial behavior: A meta-analytic review of the scientific literature. Psychological science. 2001, 12(5), 353-359. [CrossRef]

- Lin, J. H. Identification matters: A moderated mediation model of media interactivity, character identification, and video game violence on aggression. Journal of Communication. 2013, 63(4), 682-702. [CrossRef]

- Petry, N. M.; Rehbein, F.; Gentile, D. A.; Lemmens, J. S.; Rumpf, H. J.; Mößle, T.; Bischof, G.; Tao, R.; Fung, D. S. S.; Borges, G.; Auriacombe, M.; Ibáñez, A. G.; Tam, P.; O'Brien, C. P. An international consensus for assessing internet gaming disorder using the new DSM-5 approach. Addiction. 2014, 109(9), 1399-1406. [CrossRef]

- Li, D. D.; Liau, A. K.; Khoo, A. Player–Avatar Identification in video gaming: Concept and measurement. Computers in human behavior. 2013, 29(1), 257-263. [CrossRef]

- Lv, L.; Takami, K.; Dong, D.; WONG, L. R.; Wang, X. Development of the Chinese College Students' Version of Buss-Perry Aggression Questionnaire. Chinese Mental Health Journal. 2013, (05),378-383.

- Tang, D.; Wen, Z. Statistical Approaches for Testing Common Method Bias:Problems and Suggestions. Journal of Psychological Science. 2020, (01),215-223. [CrossRef]

- Shields, A.; Cicchetti, D. Parental maltreatment and emotion dysregulation as risk factors for bullying and victimization in middle childhood. Journal of clinical child psychology. 2001, 30(3), 349-363. [CrossRef]

- Gulley, L. D.; Oppenheimer, C. W.; Hankin, B. L. Associations among negative parenting, attention bias to anger, and social anxiety among youth. Developmental psychology. 2014, 50(2), 577. [CrossRef]

- Pollak, S. D.; Tolley-Schell, S. A. Selective attention to facial emotion in physically abused children. Journal of abnormal psychology. 2003, 112(3), 323. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; French, D. C. (2008). Children's social competence in cultural context. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 59, 591-616. [CrossRef]

- Deardorff, J.; Cham, H.; Gonzales, N. A.; White, R.; Tein, J. Y.; Wong, J. J.; Roosa, M. W. Pubertal timing and Mexican-origin girls’ internalizing and externalizing symptoms: The influence of harsh parenting. Developmental psychology. 2013, 49(9), 1790. [CrossRef]

- Cicchetti, D.; Rogosch, F. A. Adaptive coping under conditions of extreme stress: Multilevel influences on the determinants of resilience in maltreated children. New directions for child and adolescent development. 2009(124), 47-59. [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Liu, S.; Wu, T.; Zhang, W. Parental Corporal Punishment and Internet Gaming Disorder among Adolescents: A Moderated Mediation Model. Journal of South China Normal University(Social Science Edition). 2017, (04), 92-98+191.

- Konijn, E. A.; Nije Bijvank, M.; Bushman, B. J. I wish I were a warrior: the role of wishful identification in the effects of violent video games on aggression in adolescent boys. Developmental psychology. 2007, 43(4), 1038. [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Li, J. On the Dispelling Influence of Online Violent Games on Youngsters and lts Countermeasures. Contemporary Youth Research. 2019, (01), 102-108.

- Higgins, E. T. Self-discrepancy: a theory relating self and affect. Psychological review. 1987, 94(3), 319.

- Van Looy, J.; Courtois, C.; De Vocht, M. Player identification in online games: Validation of a scale for measuring identification in MMORPGs. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Fun and Games. 2010, 126-134. [CrossRef]

- Bessière, K.; Seay, A. F.; Kiesler, S. The ideal elf: Identity exploration in World of Warcraft. Cyberpsychology & behavior. 2007, 10(4), 530-535. [CrossRef]

- Fite, J. E.; Bates, J. E.; Holtzworth-Munroe, A.; Dodge, K. A.; Nay, S. Y.; Pettit, G. S. Social information processing mediates the intergenerational transmission of aggressiveness in romantic relationships. Journal of Family Psychology. 2008, 22(3), 367. [CrossRef]

- Dunn, R. A.; Guadagno, R. E. My avatar and me–Gender and personality predictors of avatar-self discrepancy. Computers in Human Behavior. 2012 ,28(1), 97-106. [CrossRef]

- Williams, K. D. The effects of homophily, identification, and violent video games on players. Mass Communication and Society. 2010, 14(1), 3-24. [CrossRef]

- Konijn, E. A.; Hoorn, J. F. Some like it bad: Testing a model for perceiving and experiencing fictional characters. Media psychology. 2005, 7(2), 107-144. [CrossRef]

| M | SD | Harsh Parenting | Internet Gaming Disorder | Avatar Identification | Aggression | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Harsh Parenting | 11.814 | 4.387 | ||||

| Internet Gaming Disorder | 33.731 | 14.908 | 0.414** | |||

| Avatar Identification | 14.262 | 6.549 | 0.305** | 0.544** | ||

| Aggression | 43.581 | 15.886 | 0.421** | 0.563** | 0.461** |

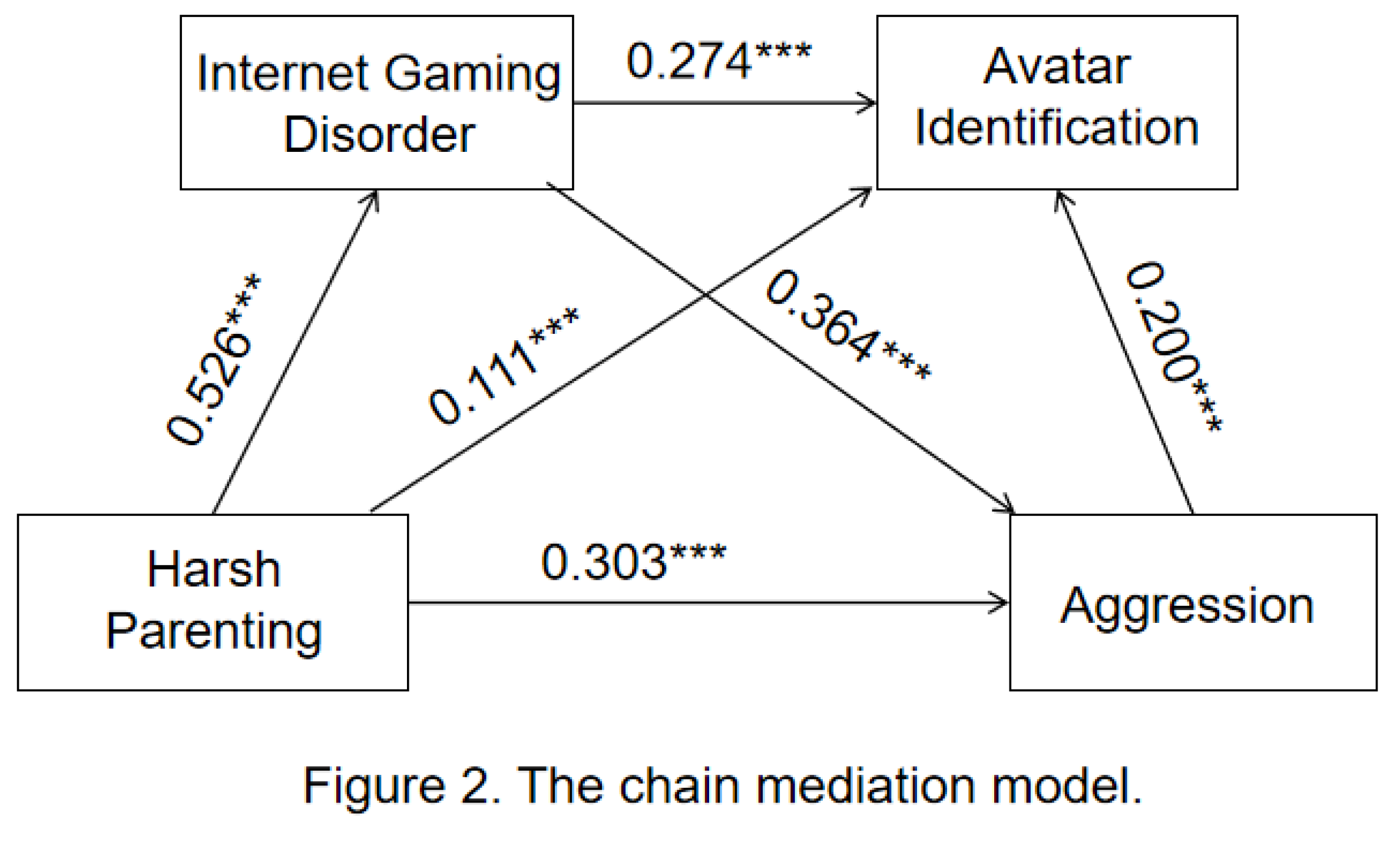

| Estimate | SE | BootLLCI | BootULCI | Efficacy as a percentage of | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| aggregate effect | 0.546 | 0.062 | 0.428 | 0.669 | |

| direct effect | 0.303 | 0.061 | 0.183 | 0.423 | 55.49% |

| ind1:Harsh Parenting - Internet Gaming Disorder- Aggression | 0.192 | 0.029 | 0.14 | 0.253 | 35.17% |

| ind2: Harsh Parenting - Avatar Identification - Aggression | 0.022 | 0.009 | 0.007 | 0.042 | 4.03% |

| ind3: Harsh Parenting - Internet Gaming Disorder -Avatar Identification - Aggression | 0.029 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.051 | 5.31% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).