1. Introduction

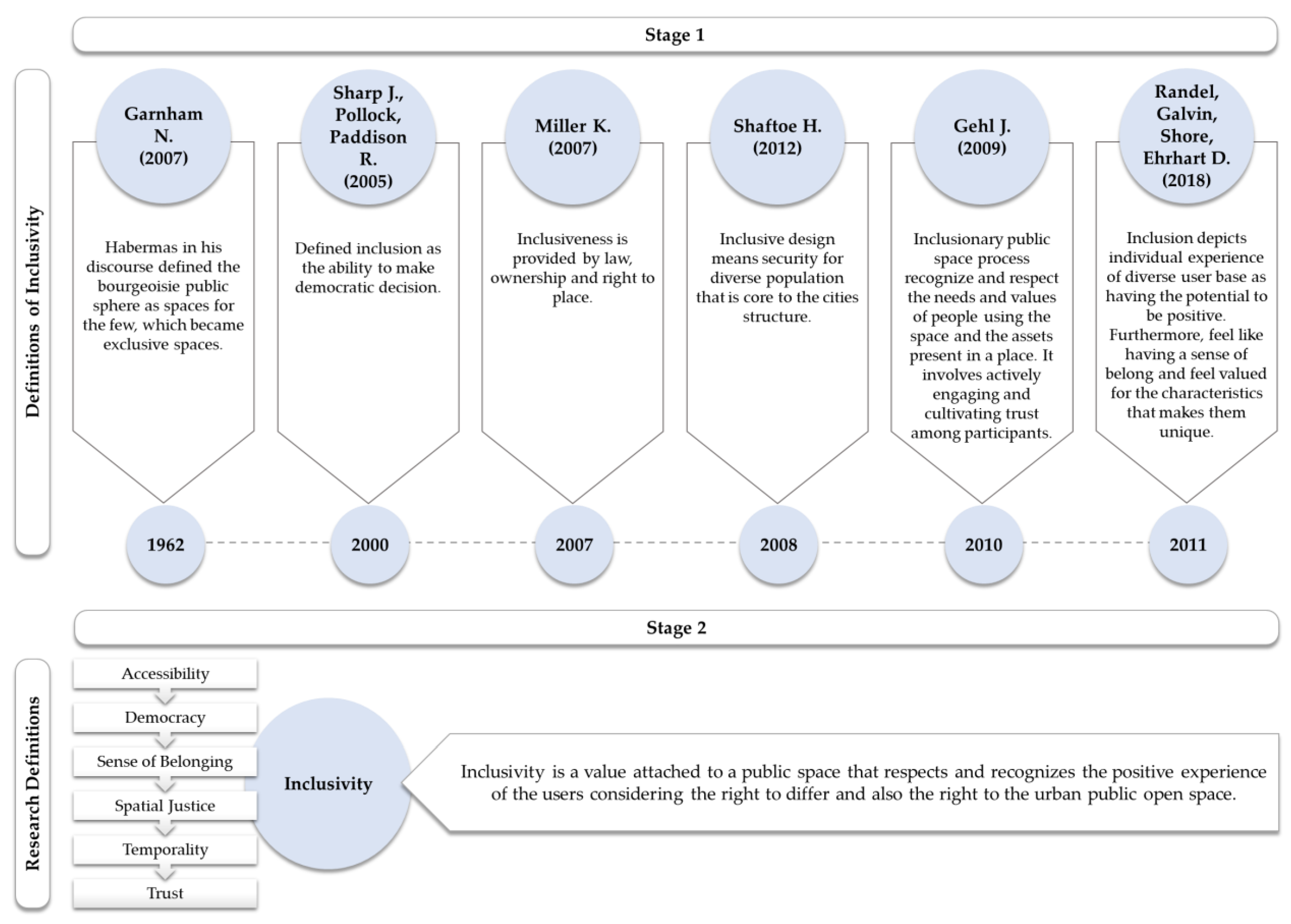

Inclusivity has been a contested theme over the past few decades [

1]. It is increasingly evident that its evolution has become a theme of great importance in the urban discourse within the Western world where a remarkable transformation in its conception has taken place. This is evident in persistent arguments, theoretical positions, and conceptual efforts of scholars, theorists, research organisations, and city councils who are advocating for the need for inclusive urban environments. Inclusivity is no longer a mere catchphrase but a necessity for achieving a just and equitable urban society.

Inclusive urban public open spaces cover multiple dimensions of urban development. Existing research identifies multiple facets associated with the notion of inclusivity. These include considerations such as physical accessibility [

2,

3], the sense of mobility and security for women [

4], the promotion of inclusive workplaces [

5], the advancement of inclusive education and access to education [

6], access to healthcare [

7], the provision of provision for affordable housing or ageing populations [

8,

9], and the facilitation of employment opportunities and social benefits [

10] employment opportunities for women [

11]. Despite the extensive studies on inclusivity, there is a lack of focus on the social aspects of inclusion in urban public spaces. Therefore, the gap this paper contributes to is in establishing the value of inclusion in urban public spaces beyond physical accessibility. Therefore, the paper critiques the different dimensions of space considered in urban theories and contributes to academic and professional knowledge by offering insights and guidance for urban design.

Questing for the city as an entity and an enabler that provides affordances for interactions between varied groups and the urban structure [

12], this paper examines the existing body of knowledge to trace the notion of inclusion and its significance [

13]. Urban public open spaces, such as parks [

14,

15], plazas [

10,

16], and squares [

17], have been the focus of numerous studies. It is essential to recognise that they play a crucial role in the lives of citizens and contribute significantly to the fabric of urban society. Hence, the aim of this study is to trace the meaning of inclusivity and associated values in the context of urban public open spaces. With this, the exploration is focused on the conceptual evolution of inclusion and exclusion, while analysing the complex interplay between social, economic, and cultural factors through the city's spatial development.

In essence, the study is premised on the postulation that urban public spaces are characterised by a constant state of flux, reflecting the dynamic nature of the cities within which they are situated. The evolution of these spaces is the result of globalisation and technological advancements. These urban public open spaces serve as physical gathering places where people can share ideas, build relationships, and provide opportunities to enhance physical and mental health. These spaces also provide opportunities for relaxation and could enhance daily commute to and from work, school, and college. They foster counter-hegemonic dispositions and conviviality [

18], a view which has been earlier discussed by Whyte in his seminal work, in which he states that “crowds attract more crowds” [

19]. The growing diversity of inhabitants has added to the complexity of the design of urban public spaces. Thus, tracing the evolution of concepts and theories associated with inclusivity in urban public spaces—by examining the existing body of knowledge across multiple disciplines from the 19th century to the 21st century—is crucial to effectively understand urban inclusivity in the contemporary Western world.

2. Materials and Methods: An Approach to Examining Inclusivity in the Contemporary Urban Discourse

This investigation adopts an anti-positivist, structuralist approach to conduct a conceptual and critical analysis of the discourse around the concept of inclusivity from the perspective of diverse disciplines such as anthropology, environmental psychology, human geography, urban design, and urban planning. A systematic theoretical framework is established to examine the notion of inclusion as a construct utilising the grounded theory approach. This is based on the premise that users undergo negotiations of realities when experiencing the space [

20]. Dewey emphasised that understanding truth is a process as opposed to truth being an absolute and constant value. He also asserted that for self-growth, democracy plays a key role in providing a cultivating social organisation [

21]. Exploring the basic process of social interactions to unravel their multilayers is linked to Mead’s idea of sociality, which he defines as a process through which individuals learn to take on the perspectives of others, internalising social norms and values [

22].

Following an integrationist literature review approach [

23] to appraise and critique to resolve inconsistencies in the literature and provide fresh, new perspectives on the topic [

24], our first step was to identify a body of literature across multiple disciplines to better understand the notion of inclusion and the evolution of public spaces. Starting from the 1680s and the eras of the utopic urban spaces, a chronological approach was employed to investigate changes in the urban planning perspectives from the socialist planning of Howard in the early 1900s to Le Corbusier’s Centrist approach in the 1930s, followed by planning for communities influenced by Howard, and the recent participatory planning paradigm.

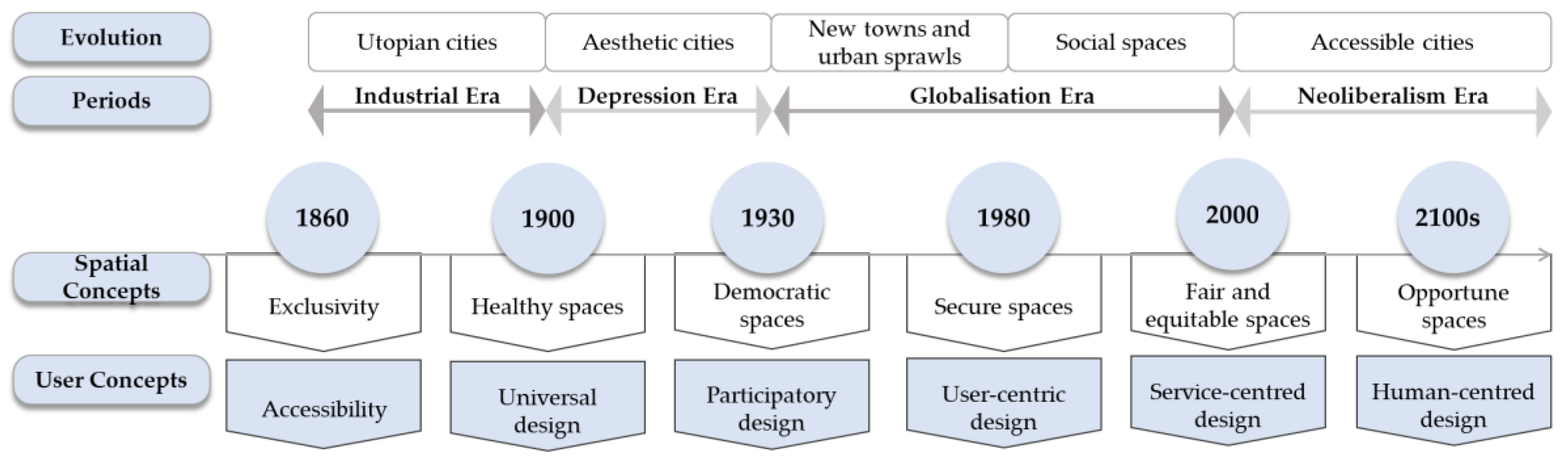

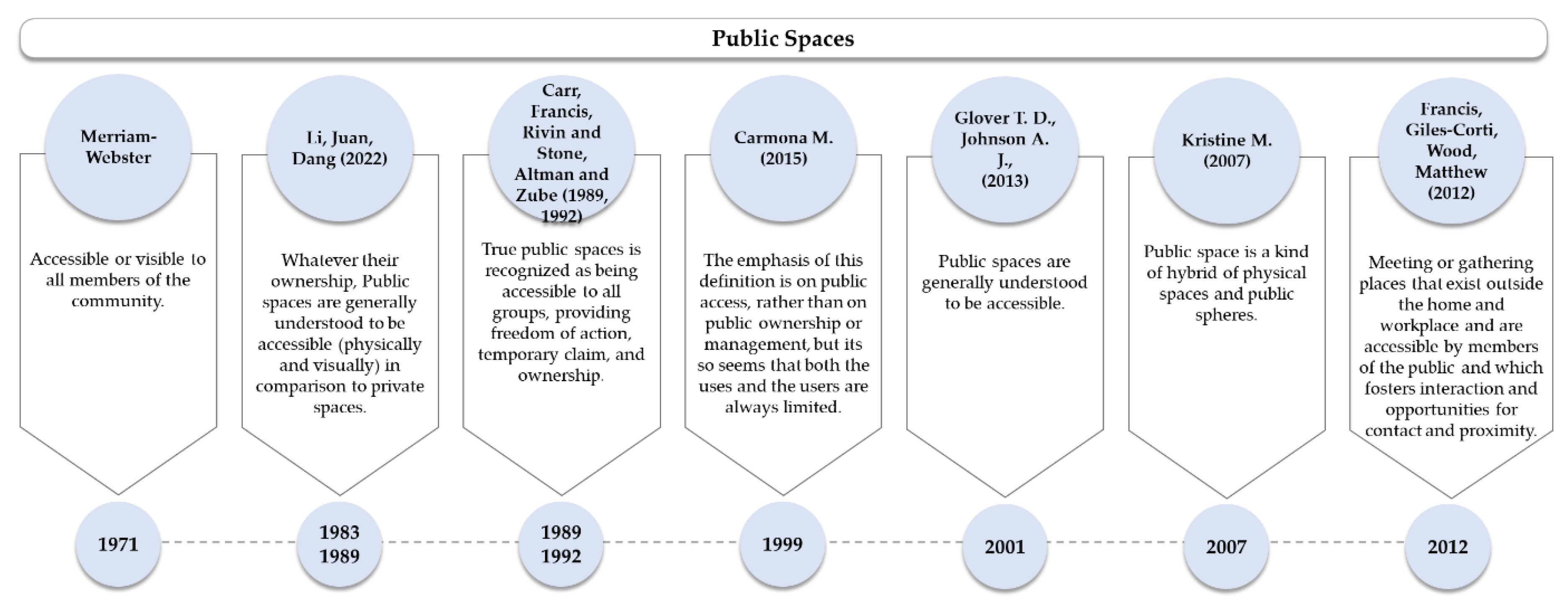

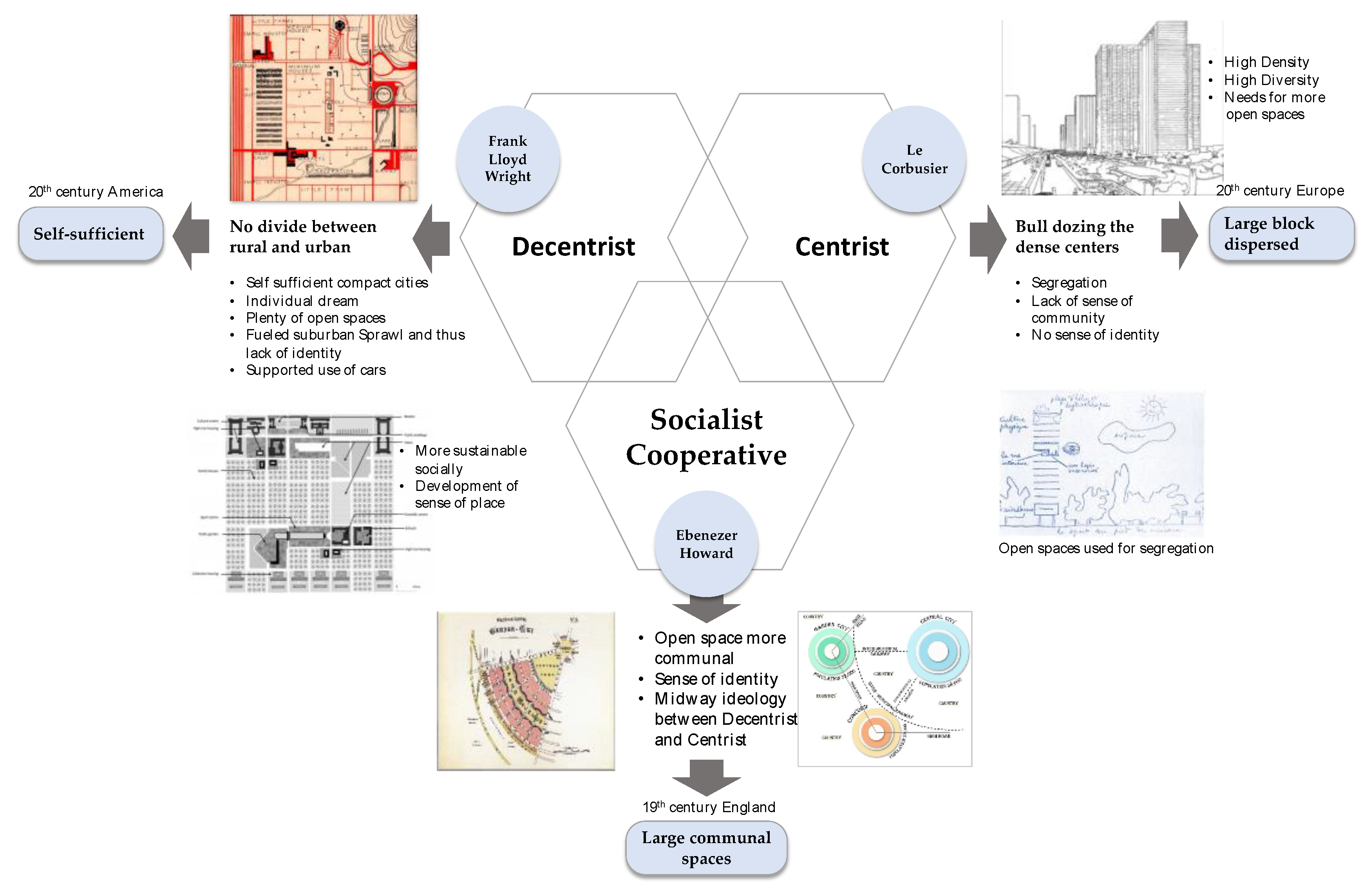

The period from the 1680s to the present was divided into eras considering the major turning points in the history of urbanism and the relevant social sciences. They are not meant to be hard divisions but serve to provide a structure that enables gathering relevant information for discussion on the development of cities and open spaces from an inclusion perspective. This timeline (

Figure 1) enabled the screening of the literature and grouping of the list of papers, books, and grey literature to understand the social, functional, and behavioural aspects of inclusivity and the relevant spatial and social theories.

The initial set of keywords used to draw the eras established for investigation included: Utopian, Dystopian World, Discrimination, Spatial Justice, Accessibility, Safe Space, Inclusivity, Democracy, Identity, Public Space, City, Territoriality, Memory, Appropriation, Convivial, Collective Space, Expression, Wayfinding, Bourgeoisie space, Liveability, Health and Wellbeing, Gender Equality, Human-Centred, Ethical Values. The list of keywords is ordered based on theoretical concepts then components related to inclusivity, and finally factors involved in assessing public space. This list led to a further nuanced list of concepts to understand the values associated with inclusion which included:

Convivial Space, Publicness, Quality of Space, Temporality.

Culture and Norms in a Public Open Space, Urban Form, and Inclusivity.

Evolution of the City, Privatisation of Public space, Discriminatory Public Elements.

Heterotopias, Globalised Values, Right to Public Open Space.

Infrastructure and Amenities, Adaptation, Resilience.

Public realms, Exclusive Public Spaces, Social capital.

Urban sprawls, Ghettoisation, Social Spaces, Place Identity.

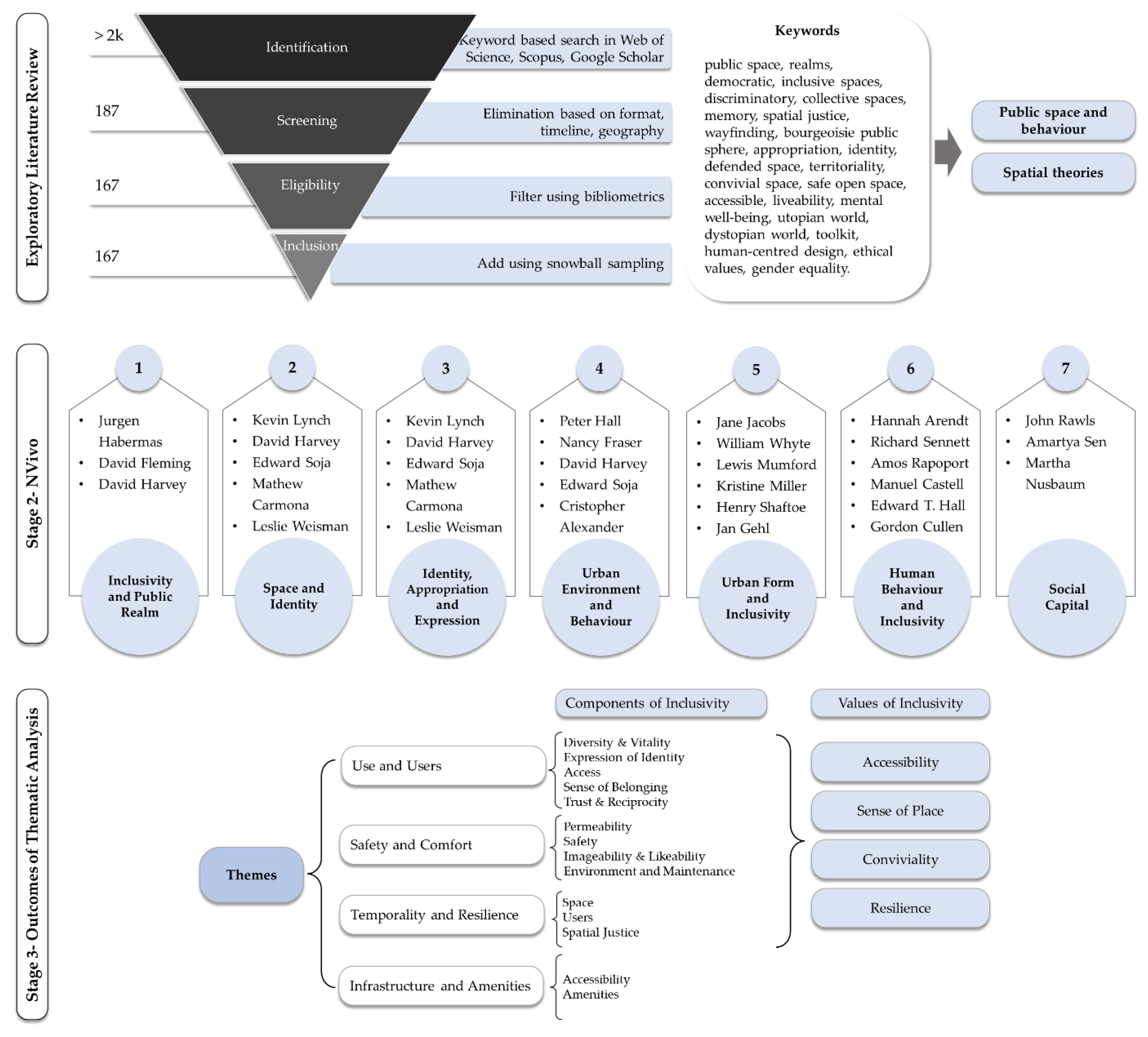

The literature search was conducted using Web of Science, Scopus, and Google Scholar. Primarily, a search was carried out on the Google Scholar search engine which resulted in over 2000 literature entries. These were screened and a list of eligible entries was generated for further analysis and scrutiny which included 167 literature articles. A few entries were added based on bibliometric analysis to ensure that the final list of entries included all the relevant publications. As this method involved studying abstract concepts and theories, the identified documents were coded using NVIVO. This process of content analysis led to a set of outcomes and associations to navigate through (

Figure 2).

A key limitation of this approach is that it looks at urban design and social science theories through the European and North American lens. The setting is restricted to these geographical boundaries, as many of the initial ideas, at least in their modern form, emerged in these regions. The second limitation is deciding on the eras along the timeline. As the study places emphasis on the notion of inclusivity and concepts of justice over a vast period of over three hundred years, the timeline had to be extensive to accommodate the start of utopian production of space and contemporary thinkers such as Marx, Bourdieu, Foucault, Habermas, and Fourier. Yet, because of this vast timeline the eras considered cover many events of social and political importance within the same era, which were captured at a higher conceptual level.

3. Discussion of Key Findings: Focus Areas and Emerging Themes

3.1. Inclusive Urban Public Open Spaces – A Driver for Social Sustainability

As urban spaces evolve over time, they retain certain attributes of their past while responding to new theories and leveraging new technologies for assessing user behaviour and attitudes towards these public areas. User behaviour significantly impacts the design and use of urban spaces. In turn, these spaces shape human behaviour; this reciprocity has been examined by many scholars [

25,

26,

27] who have investigated the evolution of cities and the driving forces behind their transformations. Appleyard advocated for studying human behaviour to create more equitable streets for a liveable city [

27]. Similarly, Sennett believed that urban public spaces should facilitate interaction between individuals from various sociocultural backgrounds [

25].

Urban public open spaces provide an avenue for social interactions, help generate a sense of community and a sense of collective identity, and facilitate the creation of memories [

28,

29]. The public open space is not merely a space surrounded by a built form but also a dynamic hub, where a diverse user base engages with the space and with each other in a variety of activities, imbuing the space with a multitude of meanings [

30]. From the Greek city-states of antiquity to the present times, public open spaces have been characterised by the exclusion of specific sectors and classes.

The notion of equal access was discussed and debated by architects and practitioners for the first time in the 1990s. However, inclusion in public spaces was associated with providing accessibility and the removal of barriers to overcoming physical disability [

31]. While physical disability was addressed, the hindrance to access presented by race, gender, age, and other physiological needs was largely overlooked. The essence of this approach to inclusivity can be found in the European Commission’s mandate in 1996. To ensure equal chances of participation in social and economic activities, “everyone of any age with or without disability must enter any part of the built environment as independently as possible.” [

31].

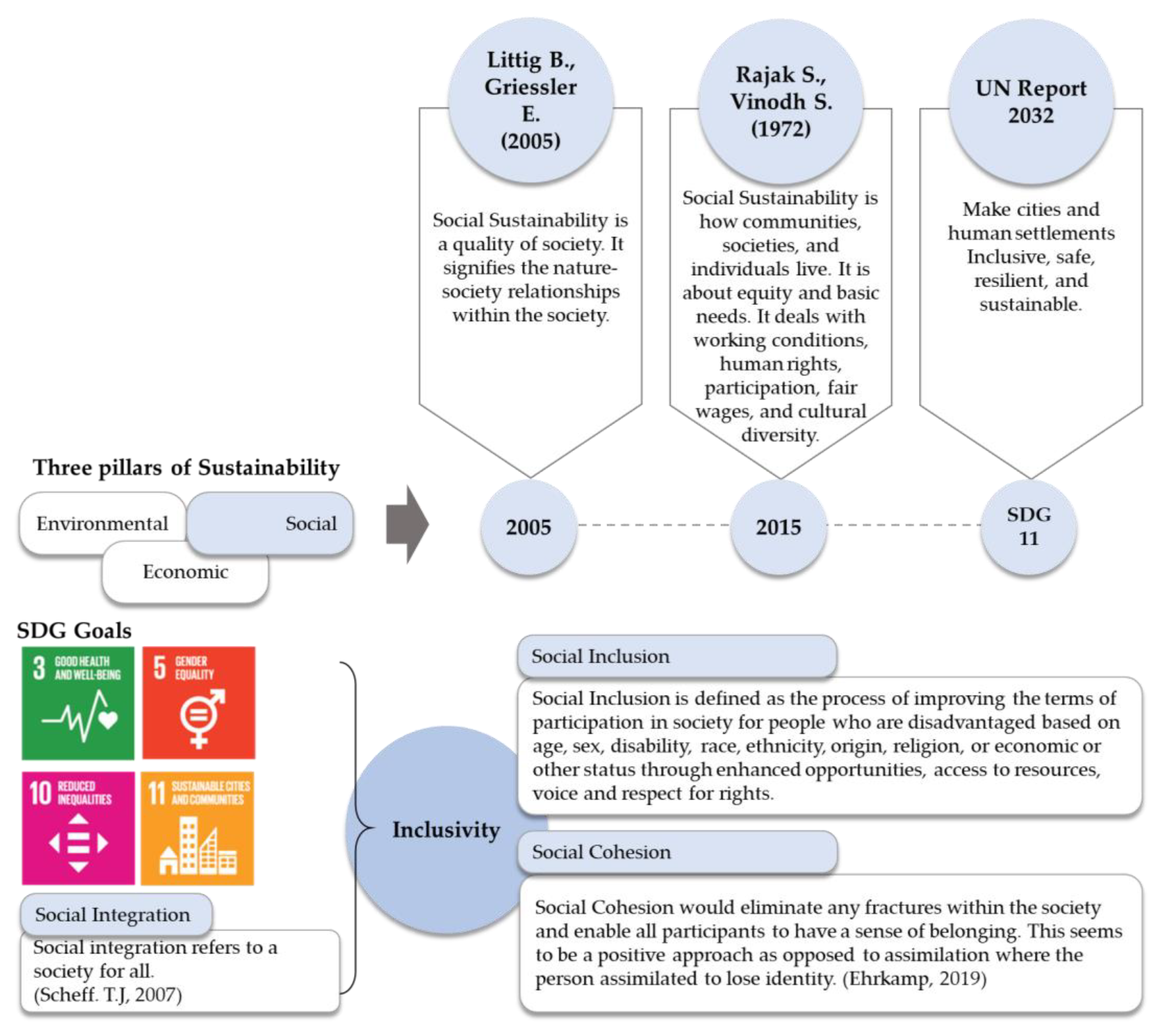

The mandate of the European Commission, introduced in 1996, continued the framing of inclusion in urban public open spaces from a physical accessibility perspective [

32]. Yet, our argument in this study is that the notion of inclusion needs to be broadened to go beyond physical access and thoroughly and committedly includes social inclusion. The emphasis on social inclusion is aligned with one of the key objectives of the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals and involves eradicating social exclusion [

33]. Notably, the three pillars of sustainability—environmental, economic, and social—have not been examined equally over the past three decades, where significant attention was given to environmental and economic sustainability, with little attention given to the social dimension of sustainability. Yet, in recent years, social sustainability has gained importance on the back of initiatives by the United Nations [

34]. Social inclusion is at the core of the United Nation’s 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. The UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) underscore the importance of social integration and social inclusion. These characteristics are identified to making societies more cohesive, the impact of which leads to social sustainability. Goal 11 of the UN SDGs states, "Make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable”. The UN stressed the importance of social inclusion towards sustainable, inclusive development (

Figure 3).

Social inclusion is defined as the process of improving the terms of participation in society who face disadvantages due to factors such as age, sex, disability, race, ethnicity, origin, religion, or economic and social standing to participate fully in society [

30]. Social inclusion can be achieved through enhanced opportunities, access to resources, diverse voices, and respect for rights. In this regard, social integration aims for an inclusive society emphasising the right to participate for all residents. It promotes social cohesion and fosters belonging, unlike assimilation, which erodes identity and gives rise to unequal power dynamics [

35]. In the context of an organisation [

36], inclusion can be characterised as “when individuals feel a sense of belonging, and inclusive behaviours such as eliciting and valuing contributions from all employees are part of the daily life in the organisation.” The same applies to urban life and social organisation, where the identity of the self becomes a part of the system, as does the idea of place identity for the community to be part of the wider community [

37,

38,

39].

The preceding discussion suggests that an inclusive public open space is one where the needs of every single individual are recognised and respected, affording them a positive experience regardless of their background. Therefore, it becomes essential to place emphasis on social inclusion over social assimilation for a more cohesive society. This is based on the imperative that urban public space plays a complex role in weaving together different city components to make it a coherent whole. The urban fabric, comprised of urban streets, pedestrian spaces, civic centres, green spaces, shops, public buildings, offices, and houses, must follow social rules to be a thriving city [

40]. Thus, for a place to be inclusive, it needs to be convivial and accessible.

3.2. Inclusivity in Public Open Spaces as Integral Components of Cities

The term ‘city’ has origins in early Christianity, whilst also appearing in the French language. Within old Christian beliefs, the city has two meanings: a physical space that includes buildings, streets, roads, and squares and, a mental space that includes beliefs, perceptions, and behaviours. The French language employs the words ‘Ville’ and ‘Cite’ to represent this dual nature of meaning [

41]. ‘Ville’ refers to the whole city and ‘Cite’ is a particular place and its people. While the two terms appear to be used interchangeably, they have different implications for the design and structure of cities. Thus, cities are physical as well as socio-spatial entities [

42].

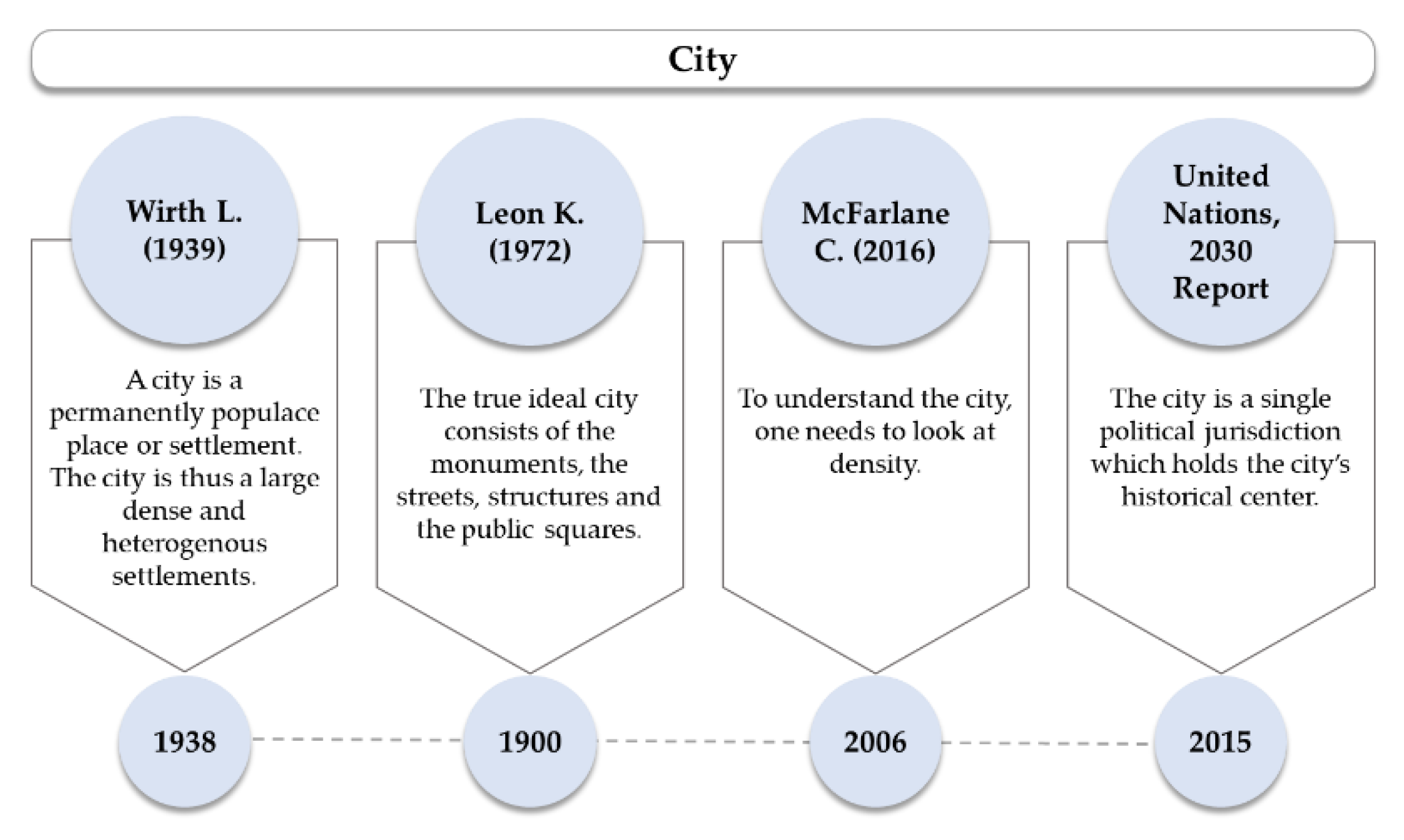

Contemporary cities have evolved and advanced beyond the ideals established by their forerunners. Today's urban centres are constructed and designed with an emphasis on efficiency, much like a factory assembly line. According to Sudjic in "

The Language of the Cities," a city is an area comprised of people within the realm of the possibilities it can offer, with a unique identity distinguishing it from a mere cluster of buildings [

43]. Following Sassen, the idea of a city can be understood as an ‘ebb and flow’, constantly evolving, and adapting [

44]. Premised on the discourse that captures the meaning of the city, a city is a space is always in a state of change and flux of activities and population (

Figure 4), noting that many city spaces are temporal and are dependent on their inhabitants.

3.2.1. The Importance of Public Space

The quality of urban space is attributed to many factors within the production of urban environments [

45]. The urban fabric is composed of streets, pedestrian spaces, civic centres, green spaces, shops, public buildings, offices, and houses. Salingaros emphasises that adherence to certain rules is essential for a successful city [

40]. As noted by Jacobs, all living cities involve a complex interplay of different components that are woven together to form a coherent whole [

46]. Public spaces play a key role in this urban mosaic. Urban public open spaces can be understood as arenas where people can engage in social and recreational activities and highlights their importance in a democratic society [

13,

47]. The connections between public spaces and the built form encourage the users to experience the place and encounter others. This is an essential component of a globalised city for increasing tolerance and identification of self as a part of the city [

13,

43,

45,

48,

49]. Therefore, it becomes important to understand human behaviour in urban public spaces to make them more inclusive for a socially sustainable city. These spaces need to be a refuge in the larger urban realm that would be accessible physically and socially and provide reasons for people to linger on or entice them to use the space as a thoroughfare. All these characteristics would positively impact spontaneous interactions in public open spaces. It has already been proven that inclusive public spaces offer obvious health benefits [

13]. Such inclusive public spaces foster engagement and encourage openness rather than becoming monocultural enclaves.

Figure 5 provides key highlights within the urban discourse relevant to inclusivity in public open spaces.

3.2.2. The Evolution of Inclusivity

Earlier research on inclusivity was based on the economic status of the cities under study post-World War II. At the time, urban policies targeted reduction in urban poverty and were linked to economic development [

50] towards developing a new model of inclusive cities. Over time, urban inclusivity as a concept was broadened in scope to consider issues beyond the income of the citizen. The discourse on inclusivity was focused on overcoming the racial divide in education and all other fields during the 1960’s. A significant milestone was the passing of the disabled person employment act in 1944 [

51], which marked further expansion of the discourse around inclusivity. In the context of the United States, the Disability Discrimination Act (DDA) in 1995 mandated the creation of inclusion boards dedicated to enhancing accessibility towards a more inclusive society [

52].

In 1996, the European Union passed a major bill for addressing social inclusion by highlighting the need to create an environment accessible to everyone [

53]. This climaxed in the vision of "A Barrier-Free Europe for People with Disabilities" by 2000, which underscored the necessity of policy interventions to eliminate barriers. By the turn of the millennium, the scope of inclusivity expanded from physical accessibility to include eradicating social barriers for people with disabilities [

31,

33]. Social inclusion was brought to the forefront of the discussions by the UN 2030 report, which highlighted the role of social inclusion in a socially sustainable city [

33] where social inclusion was debated for the first time across various fields, including social work [

5] and social psychology [

54].

3.3. The Production of Urban Environments

The earlier pattern of urban development can be traced to the 16

th Century. Yet, the development of cities is influenced by the growth of capitalism worldwide. Brudel considered that capitalism originated in Europe with the commencement of goods trading in the preindustrial period [

55]. He believed that a sense of social hierarchy was necessary to dominate the agrarian rural areas in the struggle for survival, money, and power. This resulted in the growth of cities, which became regional markets instead of local. Modern world cities underwent spatial transformations in the pursuit of dominance and power. During the period 1500s–1800’s cities were in the process of economic transformation, creating regional economies. From the 1500s onward, there were significant shifts in populations and structural urbanisation to form hubs of economic activities, fostering the concentration of population in urban centres by the 1800s. These developments have been instrumental in determining the patterns of urban development. The associated decisions on social issues relevant to inclusivity can be considered in five eras:

1800- 1900: Proto-industrial era and the production of utopian spaces.

1900- 1930: The aesthetic city and the era of depression.

1940-1970: Post WW II and the emergence of new towns and urban sprawl.

1970- 2000: The notion of social spaces.

2000- 2023: Recent developments.

These eras are not hard divides but provide a structure for gathering information on the development of cities and urban open spaces. Thus, the timeline is categorised into sections addressing the major urban developments and the associated social theories and concepts that overlap with important policies.

3.3.1. Proto-industrial Era and the Production of Utopian Spaces (1800 - 1900)

The beginning of this period was marked by severe economic hardships and glaring disparities in living standards. Cities were dense, unhygienic, and unsafe due to vagrancy and criminal activities. People residing in these conditions had limited options to travel for work due to lack of finance/low income. In response to these challenging conditions, the first tenement housing was proposed under the working-class housing act in 1885 [

56], in the United Kingdom. However, there was a lack of focus on green spaces and communal areas. This pattern of dense urban housing with no external social spaces was observed throughout northern Europe and the United States [

57]. Eventually, this gloomy period was followed by the Beautiful City movement from 1900-1945 (further discussed in section 3.4.1). At its core, this movement was a concept that shifted from viewing the city solely as a symbol of economic growth and industrial progress to recognizing its potential to enhance the visual appeal and quality of life for its residents [

58]. Zoning regulations during the Beautiful City movement were influential in urban development but were deemed socially exclusionary [

57]. Olmsted, 1862, argued that parks, playgrounds, and open spaces create a harmonising and refining influence on the citizens [

58]. This marked a fundamental moment in city development that instigated the first discussion on the quality of urban life and inclusion.

3.3.1.1. Phalanstery

In response to the failure of the French Revolution, Phalanstery was a utopian planning idea in the early 1800s proposed to address social inequalities, but ironically resulted in more inequalities. The utopian idea of the shared community, developed by the renowned French philosopher Charles Fourier, was a retaliation to these inequalities [

59]. Fourier proposed a comprehensive reformation of societal values, territorial economics, and architectural design to address the ongoing developments in capitalist societies. He observed the potential efficiency of this initiative and its impact at one of its epicentres in Paris during the 19th century [

59]. His work addressed issues of spatial and social spaces that other collectivists could not address. Fourier's communal space (Phalanstery) lacked flexibility, but the notion of social communities did not die. A few decades later, the French industrialist Jean Baptiste Godin created an exclusive social community called “Familistre”, or social space [

60].

3.3.1.2. Haussmann’s Paris

Baron Georges-Eugene Haussmann, a French civil servant, was appointed as the chief planner of Paris by Napoleon III in the 1850s to address the issue of revolts [

61]. He introduced an innovative approach to city planning, creating long boulevards that were difficult to barricade and could accommodate two horse-drawn cannon carriages side-by-side. This approach improved the quality of life for Parisians significantly, as it dealt with unsanitary conditions and prevented the spread of disease. Haussmann's plan also involved clearing up the filth accumulated due to poor sanitation [

61]. As the city faced growing unrest from within, its fortification evolved. One result was the development of a new network of streets and a reorganisation of housing. This created a boulevard housing system that generated a vertical hierarchy, with the affluent residing above the shops and labourers situated behind pre-existing settlements.

3.3.1.3. Artistic Principles for City Planning

Ildefons Cerda, a Spanish Urban Planner and Engineer, created an additive grid system during the city planning of Barcelona. This system provided flexibility in planning and enveloped the existing city while preserving pockets for green spaces. The green spaces were not exclusive to a few but could be enjoyed by all [

62]. However, the grids were at right angles and resulted in the elimination of street corners that were an avenue for social exchanges. Another point of interest in Cerda’s planning was that inhabitants of different socio-economic backgrounds would live together, a concept which is known as mixed housing or Dutch style housing [

62]. Cerda attempted to make the city equitable to all, but the additive grid also amplified social and economic issues.

3.3.1.4. Gregarious Parks

Frederick Olmstead, landscape architect and journalist, wanted to design and build a communal park in the middle of New York for all races. He believed that fostering inclusion would be easier in larger non-intimate spaces of a park than within the territorial confines of the neighbourhood [

63]. The location chosen for the park was on lands that earlier included an integrated rural life with residents being free blacks (African Americans who were not enslaved) and Irish farmers. The new integrated urban park destroyed the fabric of the existing social setup. Unlike the parks in Paris, which had huge ornate gates, Olmstead’s Central Park had simple gates with very low boundaries. While Haussmann’s plan was to control the people through elaborate gates, Olmstead believed that safety could be ensured by getting people together in the huge open space of the park. Collaborating with Calvert Vaux, landscape designer and architect, he designed the infrastructure with roads at a lower level for ease of access and was successful until the economic setup around the park was transformed [

64]. The vacant plots around the park were now transformed into mansions of the rich, which altered the social landscape around the park.

3.4. The Aesthetic City and the Era of Depression (1900 - 1930)

This period witnessed the transition from the earlier crowded and unhygienic towns to new planning ideologies in the 20th century. This evolution of the post-industrial city could be understood by considering the Centrist and Decentrist planning paradigms as an integral part of the discussion. The Centrists condemn the urban sprawl and prefer to have high-density cities, whereas, on the other hand, the Decentrist reacted to the problems of the industrial city by decentralised planning [

65].

3.4.1. City Beautiful Movement

The roots of the City Beautiful movement can be traced back to the boulevards of Haussmann’s reconstruction of Paris [

66]. In the late 1800’s Daniel Burnham, partner in the architectural practice Burnham and Root in Chicago, played a major role in the propagation of the movement in the United States. The 1909 plan for Chicago was the most prominent example [

67]. The key document of the City Beautiful movement proposed a new civic centre, axial streets, and a lakeside park for recreation, with only the latter being substantially realised. The City Beautiful movement focused on creating beautiful boulevards and ornate facades while the poor remained behind big walls. This movement also caught on in other parts of Europe, creating beautiful cities for the bourgeoisie while relegating the public into obscurity. Cities were made beautiful as pieces in the theatre, with little thought to the proletariats. This expensive obsession continued for over eighty years worldwide, causing more social exclusion.

3.4.2. The Garden City – The Decentrist Movement

The Garden City movement started during the period between 1899 and 1914 [

63,

68]. Influenced by Howard, it was also known as a social city movement and had its precursors in the earlier periods. With Howard’s ideas, urban planning considered a more cooperative socialist approach [

63], which involved a comprehensive set-up, cheaper land acquisition, relocation of factories shifting within the planned perimeter and creation of a well-connected rapid transit system [

69]. Lewis Mumford, architectural critic, urban planner, and historian, refers to Howard’s planning philosophy as social planning since this was a polycentric vision of the city which incorporated urban and rural elements and emphasised social cooperation [

41,

58].

3.4.3. The City of Towers: The Centrist Approach

The influential modernist architect and planner Le Corbusier believed architecture must be machine-like and functional. He championed the idea of mass-produced houses [

58]. His plans for the house ‘La Ville Radieuse’ involved the creation of a segregated social and spatial structure. He considered that high towers with free ground floor space would ease the visual challenges posed by his layout [

70]. As one of the most prominent figures in the post-depression era, his vision evolved from high-rise to low-rise structures, as seen in Chandigarh (North India), where he was commissioned to design a new capital city [

70]. The outcome, however, was a city heavily segregated by income and civil ranks, designed with functionalist boxes placed within a site.

3.4.4. Garden Suburbs

Raymond Unwin, engineer, architect and town planner, and Barry Parker, architect and town planner, tried to design spaces around communal green areas inspired by the medieval quadrangles. However, their first project, Hampstead Garden Suburb, London, failed to attract residents [

71]. The proposed social housing required residents to commute to work without access to transportation. Furthermore, rising land rates led to increased rent, ultimately causing the intended social housing to become gentrified [

56]. It is interesting that this gentrified garden suburb has now become one of the most expensive areas in London.

Influenced by the Hampstead development of Unwin and Parker, in 1982 Clarence Stein and Henry Wright, planners and sesigners, along with Marjorie Sewell Cautley, landscape architect, developed Radburn as an American version of the ‘garden city’ [

71,

72]. Located within New Jersey, the Radburn layout incorporated small, terraced cottages grouped around a communal garden that had pedestrian pathways. The original intention of the Radburn layout was to create a garden suburb like the earlier Hampstead social housing. But Radburn became a place for the middle class with almost no blue-collar residents as planned. Thus, its unintended exclusivity resulted in neglect towards the low-income residents who provided essential services. Furthermore, over time, the lack of industries caused a shift towards gated communities in the United States, mainly for people with cars. The Radburn Concept was later adopted in Germany. However, it underwent a process of gentrification that resulted in only 11% of residents being blue-collar workers – a stark contrast to its original purpose [

69].

3.5. Post-World War II and The Emergence of New Towns and Urban Sprawl (1940’s -1970’s)

This timeframe is referred to as the golden age of planning since it was free from political interference, unlike the earlier periods. The 1940s saw the development of planning schools, which also coincided with the baby boom period. This era of relative affluence also resulted in mass consumption in society [

63,

73]. The city's dynamism caused a problem for the planning process since planning ideologies at the time addressed the static city and were not equipped with the tools needed to address the accelerated growth. This led to a shift in outlook where planning changed from heuristics to a scientific endeavour, involving precise information gathering and processing. The new planning paradigms that emerged during this period considered the city as a complex system with many interrelated activities that required monitoring and, if necessary, modified. However, by the end of the 1970s, planning was again in a state of crisis which can be seen in massive gentrification with car dependency a key feature [

56].

3.5.1. Privatisation of The Public Spaces: Loss of Social Network

As observed by Sudjic, writer and broadcaster specializing in the fields of design and architecture, there has been a systematic decline of social spaces since the 1860s. This was further accentuated by the drive for privatisation, which accelerated the demise of social activities and networks [

43]. The erosion of the social network in public space resulted from technological advances such as the proliferation of the automobile and the advent of privatised public spaces. Yet, urban planning has also unwittingly given rise to segregation and exclusion where gated communities would have access to privatised public spaces with all the amenities within their boundaries. In this respect, Harvey, an urban theorist, explains the idea of utopia that would give us the freedom to be more creative while finding solutions for more inclusive cities [

74]. Furthermore, ideas proposed by Jacobs, an urban theorist, particularly on diversity and internal security, warrant critical examination, given that the emphasis on achieving a sense of security should not result in commodified spaces dominated by surveillance and resulting in new hierarchies [

33].

3.6. Social Space (1970’s – 2000’s)

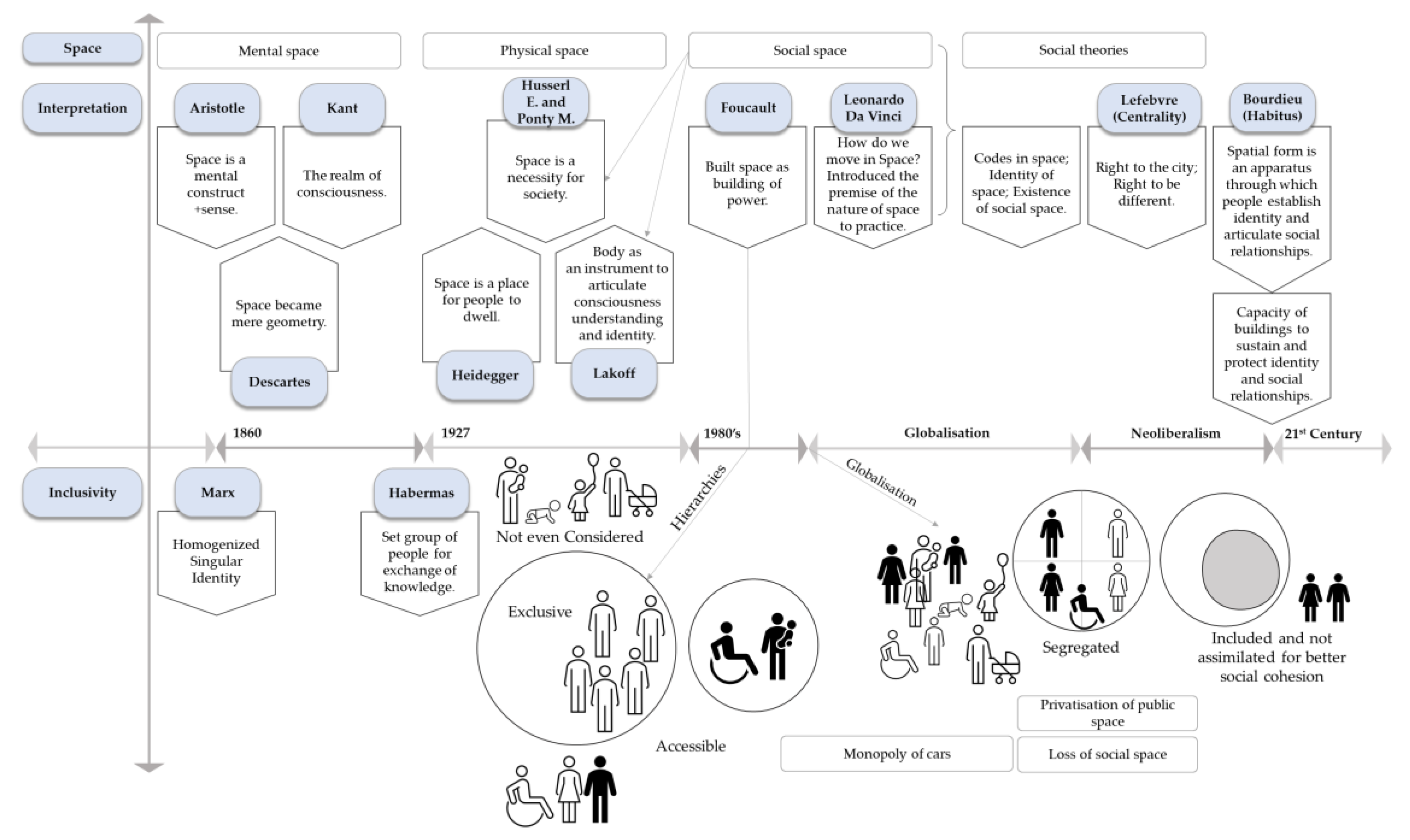

The idea of space has been explored heavily in the body of knowledge that draws from various disciplines (

Figure 6). Soja, political geographer and urban theorist, asserted that space shapes the behaviour of the inhabitants [

75], a conception that contrasts with the mathematical and philosophical approach taken by Leonardo Da Vinci. Soja shifts the focus from mental space to physical space, drawing attention to the practice of space and the existence of social space where social encounters take place [

77]. Husserl, philosopher, and mathematician, and Merleau-Ponty, phenomenological philosopher, emphasised the importance of social space for societies to develop [

78], whereas Heidegger, philosopher, looked at buildings as a place for people to dwell [

75].

In contrast to preceding thinkers, a different perspective is provided by Foucault, philosopher and historian, who considered built space as the building of power that could afford or deny people specific practices [

78]. Hence, the built space involves practices for hierarchies and roles in society and in the creation of segregation. In developing critical thought further, Lakoff, a linguist and philosopher expanded the understanding of the built space in connection with the body, considering it as an instrument to articulate consciousness, understanding and identity [

75]. The identity of the self and the identity of the space developed into an integral part of the discourse. In the interim, Bourdieu, social scientist, looked at habitus, a spatial form through which people explore their identity and sense of social relationships through their past experiences [

78]. In this respect, the individual tries to form a relationship between the built space and the self and identity emerges as an important aspect which needs to be examined from the lens of the sense of belonging [

79].

3.6.1. The Right to Space

The right to the city has been an essential part of the discourse around public spaces [

76,

80,

81]. However, claims to space have been a multifaceted issue with claims to public space contested [

82]. As outlined by Lefebvre [

76] in his seminal work-

The Production of Space, the right to the city is the right to participate and the right to appropriate. With this, he argued that cities and gated communities are designed for exclusion rather than inclusion. The city is made up of people who are diverse on accounts of race, gender, income preferences, and age. Everyone would thus appropriate and relate to the space differently. The right to the city, as expressed in this sense, is considered an important foundation to examine how the user expresses their identity and how appropriation would enhance the action of expression and belonging [

57].

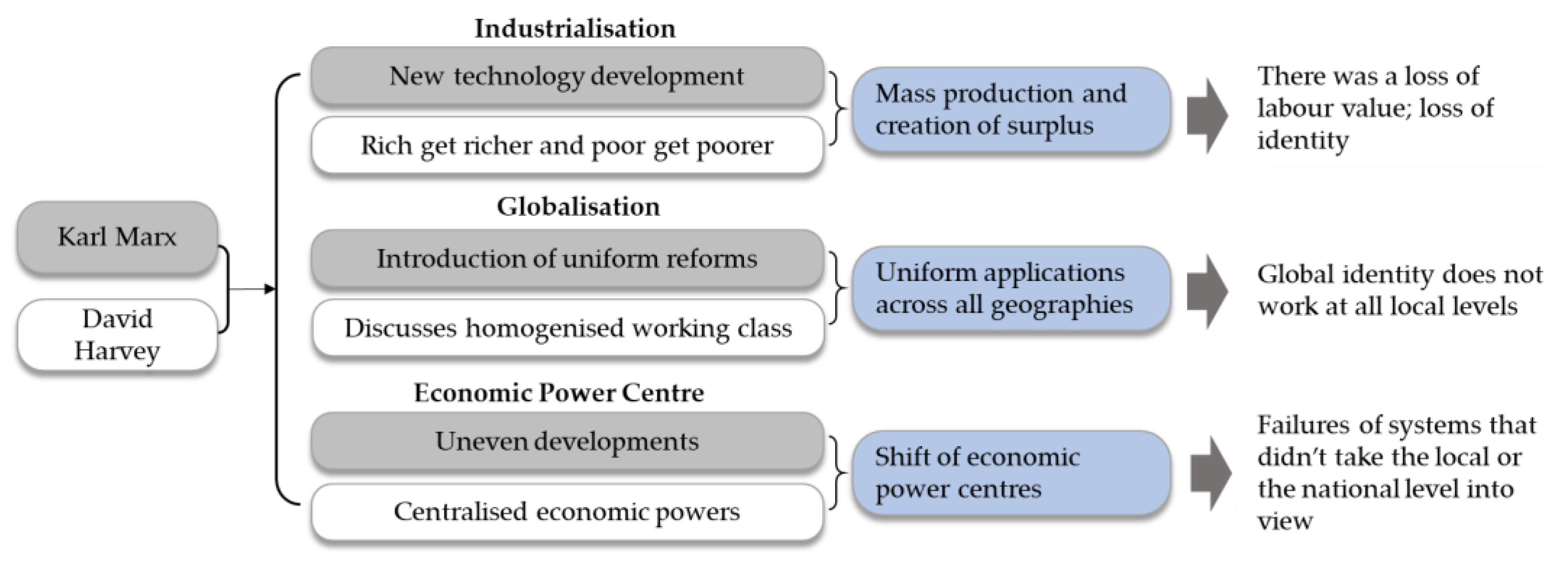

3.6.2. The Sense of Identity: Between Marx and Harvey

The communist manifesto of Marx, philosopher and economist, was written at a time of a radical change in society because of technology. Marx believed in the primacy of class struggle and the loss of identity brought about by the mechanisation of work [

84]. Harvey was not convinced by the notion of a homogenised working class since it does not account for the differences due to culture and ethnicity [

74]. Marx’s working class has no national character or country and overlooked the geographic landscape through the understanding of religious beliefs, gender, and cultural differences. Marx also considered the emerging bourgeois communities as one group and disregarded the distinction among them across different geographies. In these current times, we are faced with a rapid acceleration in technology and globalisation. Thus, it becomes important to grasp views from social theories to understand current challenges which include a great social upheaval (

Figure 7).

3.7. The Contemporary Era (2000- 2023)

3.7.1. Space as a Matrix of Public Spheres

A public sphere is an intangible or abstract behavioural practice that exists within a physical public space [

85]. Examining the relationships and interactions across the public sphere and behavioural practice is instrumental in studying the dynamics within public open spaces and in understanding how attitudes are represented through the behaviour of the users. Public spheres are the way people claim their niches in the public arena. Thus, social identity “refers to an individual’s subjective representation of the interrelationships among his or her multiple group identities” [

86] and can range from a simple unified identity to a complex and multifaceted identity (

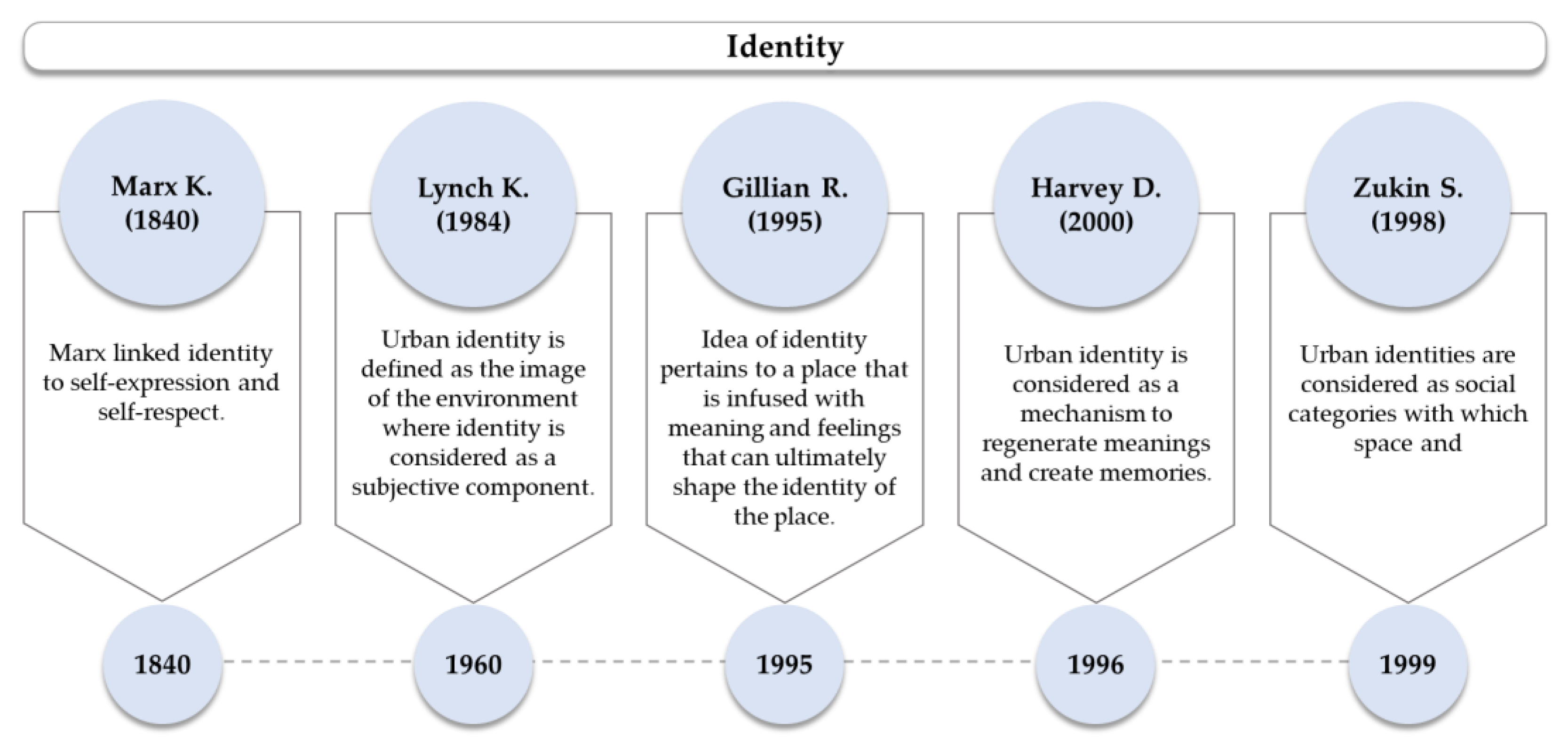

Figure 8). As identity is essential to the individual, it can be regarded as a representation of the idea of a sense of belonging.

3.7.2. Publicness/Convivial Spaces

Publicness, as defined by Zamanifard is the extension of the right to public space [

87,

88]. The production and development of space needs to take place at different levels and in different ways. Harvey looks at the concept of geographic development in the capitalist world. The geography of a space has an impact on all human activities including social, ecological, political, and economic processes. Such processes also influence changes at the local, state, regional, national, and international levels differently. Harvey argues, that “This mosaic is itself a ‘palimpsest’-made up of historical accretions of partial legacies superimposed in multiple layers upon each other as the different architectural contributions from different periods layered into the built environments of contemporary cities of ancient origin” [

74]. Therefore, the understanding of spatial scale is integral to the understanding of the production of space and its development with regards to the notion of publicness.

The publicness of public spaces is often romanticised or idealised [

28,

89]. The notion of publicness has become an important part of the narrative over the years. Publicness would render the space with qualities which are democratic, social, and symbolic [

90]. However, the idea of public space as a political space or a space for dialogue between different social groups may not be realistic. Therefore, concerns regarding the erosion of politics or the erosion of diversity from public spaces might be exaggerated. Thus, public space is seen and used in diverse ways, some of which might lead to a sense of exclusion. An example provided by Smith considers how economic differences allow for a place to be used or seen as safe by a few but not by all [

91]. The middle class tends to avoid undesirables such as homeless people or gangs of teens in public spaces [

92] where some urban commentators and users think the presence of these marginalised groups is a sign of a decline in public space [

92]. In this respect, Young defines the unoppressive city as one that is accessible, inclusive, and tolerant of differences [

93].

4. Discussion

The examination of the preceding quasi-chronological analysis resulted in defining key issues of relevance to the notion of inclusivity. These issues are centred on an endeavour to position and define inclusivity including aspects of utopian spaces, the Centrist-Decentrist dialectics, and the way in which inclusivity manifests in public space.

4.1. Utopian Spaces

The utopian period is a valuable context to juxtapose with the current state of urban public spaces. Three case examples can be captured. The first case is Creda’s grid system and mixed social housing in Barcelona which aimed to provide green spaces accessible to all sections of society. Yet, the grid generated monotony and led to a reduction in usable social spaces that would have a character, sense of place or place identity. The second case is that of the landscape designer Olmstead who planned a park of significant scale that was to provide a place for all, ensuring ease of access and offering elements to make the users feel welcomed in New York [

63]. Nonetheless, the planned park turned out to be an asset for the rich, and thus, the intended socio-economic status has dramatically changed. The rise in land value around the perimeter of the park saw a drastic change in the social mix, creating barriers for the middle and the lower middle classes.

The third case is evident in Haussmann’s planning where people were segregated based on their socioeconomic conditions. This resulted in creating space for aesthetic appeal, but in the process, created public spaces that exhibited three important characteristics. The first characteristic is the creation of destinations where the plan involved establishing building facades as a theatrical art form. The grand department stores situated at the ground level, visible through their transparent exteriors, proved to be a popular attraction for the affluent class from across the region. The second characteristic is viewing arcades as social spaces where the intricate passageways adorned with glass ceilings, assumed a significant social role. These small economic centres emerged along the internal networks that traversed the pathways of Paris and evolved into thriving pedestrian zones. The third characteristic is the creation of solitary public spaces where cafes that proliferated along the boulevards were transformational in creating social spaces. By the turn of the 20th century, they featured small circular seating arrangements suitable for individuals or small groups [

41]. From these characteristics, it can be argued that Haussmann developed boulevards prioritising space over place and creating social spaces for the privileged few. However, in a diverse contemporary society, the space should aim to enrich the users' experience by generating social spaces for individual expression and the creation of destinations for developing memories over time.

4.2. The Centrist and the Decentrist Debate

The Decentrist movement aimed to foster a more cohesive and economically inclusive society, built with a form of public involvement, ensuring that the capital earned from the properties would flow back into the community. While the Garden City movement had started with an egalitarian approach, it ultimately led to the development of consumerist communities and the emergence of subtopia. These garden suburbs lacked the spirit of communal living [

58]. The antithesis of these developments was the two- to three-storied housing in Frankfurt from 1926 to 1931. This was functional and proved liveable with underground station connections at both settlement ends. The common thread across these developments was the provision of green space for communal activities encircled by safe pedestrian walkways. These low-density housing developments built within the Decentrist movement were tailored to a specific demographic, which resulted in exclusionary practices. There was a systematic exclusion based on race and socioeconomic class. Additionally, the absence of employment opportunities led to additional expenses for people travelling to workplaces far from these developments. Furthermore, the absence of transport links, a characteristic of the garden city movement, made travel to the workplace difficult. As families grew in the post-war years, housing provision proved to be inadequate due to lack of parking space and convenient proximity to smaller shops.

The Centrist approach was also unable to provide a solution, as it resulted in disrupting established social networks and led to further segregation. In the early 21st century, the debate has shifted in favour of the Centrist approach, which is considered more sustainable in the face of climate change. Howard advocated for a socialist cooperative approach placing emphasis public transport, which became a model for developing cities and public spaces in post-World War II Europe [

81]. However, the notion of compact cities has a single-minded focus on environmental sustainability and does not provide answers to making diverse cities socially sustainable or socially resilient. Social sustainability would require the city to support the creation of strong social networks, giving the residents a sense of place and a sense of identity. A representation of the Centrist-Decentrist debate is outlined in

Figure 9.

4.3. Towards Social Equity and Diversity

Howard looked at public transport (railways) connected to polycentric development. He aimed at developing public spaces that consider men and women equally. This was a more socialist approach to developing a sense of identity and community to enhance social networks. However, it resulted in the regional planning departments compacting the cities, oversimplifying social aspects. Notably. the impact of urban planning on diversity was only considered much later in the 21

st. century with the work of Gehl [

95], Miller [

85], and Shaftoe [

13]. Some of the key developments can be identified in four areas that include recognition that the city is in constant flux, the aesthetic view of towns was replaced by the socio-economic view, planning became a process rather than a product or outcome and a science and not pure art as was historically.

4.4. Public Space and Inclusivity

Relevant to the UN SDGs, examining the existing body of knowledge reveals that the sense of inclusivity for public open space within the city should be considered at the street level. Inclusive public spaces should aim at integration rather than assimilation, where inhabitants are able to feel a sense of place [

23,

33]. Thus, inclusion is a value attached to a public space that respects and recognises the positive experience of the users, considering the right to difference and the right to the urban public open space. On the other hand, a sense of belonging and community participation are beneficial for the user's well-being [

96]. Thus, the notion of identity of the self, as highlighted by Marx and Harvey, also becomes a prerequisite for inclusivity in addition to the idea of place identity at the community level [

74,

84]. Multiple social identities focus on intersectionality, “

the manner in which multiple aspects of identity may combine in different ways to construct social reality” [

97]. Identity would also become an important part in the sense of belonging to the community and thus leads, for example, to a reduction in crimes where the public space is safer, democratic, and more engaging [

89]. Promoting a sense of community and belonging would result in social inclusion, which is an important consideration for diverse and inclusive cities. This cohesion would enable inclusion by fostering identity, representation, and respect. “

Mixed neighbourhoods need to be accepted as the spatially open, culturally heterogeneous, and socially variegated spaces that they are” [

97]. This means that for urban public spaces to be sustainable, they need to be inclusive by creating a sense of belonging and, thus, a sense of community.

Furthermore, social inclusion is also associated with economic growth, as argued by Kweon et al. [

50] who demonstrate the relationship between the edge conditions of public space and the space itself, which affects the economic conditions of the shops in the immediate surroundings. Looking at the larger picture, social inclusion is also important to attain economic competitiveness. Social inclusion would open opportunities to participate in a prosperous urban economy and the benefits of growth would trickle down the social hierarchy [

98]. Another aspect of inclusion is the effect of the built form on user behaviour. The built form offers the user a sense of security and enclosure. Franklin argues that a ratio of 1:1 (width-height) is correlated with a sense of security [

99]. Certain types of facades have been seen to promote street life, neighbourliness, and even enhanced social support. This would, in turn, help in achieving a sense of community. Today witnesses more gentrified and thus homogenised spaces on account of security and other social reasons. This has caused unequal, more authoritative, and banal public spaces that often do not foster diversity.

The preceding discussion suggests that inclusion is a value attached to a public space that respects and recognises the users' positive experience, considering the right to difference and the right to the urban public open space. In this sense, inclusion helps generate a more socially cohesive environment where identity and integration collectively take place. As illustrated in (

Figure 10), the qualities of an inclusive space that appreciates identity and helps in integration should, therefore, be democratic, comfortable, adaptable, universal, develop identity, be safe, enhance attachment and support good governance [

37,

38].

5. Conclusion

This study traced the notion of inclusivity by conducting a comprehensive analysis of the discourse spanning over two centuries. Unlike previous studies with a narrower focus on physical accessibility, a broader approach was adopted by considering social inclusion as an essential aspect of inclusivity. The study has demonstrated that social inclusion has emerged as a crucial element in socially sustainable cities, which are characterised by rapid technological advancements, the spread of urbanisation, and the growing diversity propelled by globalisation. The culmination of the research process is the identification of three key outcomes associated with inclusivity.

The analysis of the trajectory of urban public spaces over a period of two centuries was undertaken focusing on five eras. The proto-industrial era was characterised by experiments such as the exclusive urban public spaces in Hausmann’s Paris, and the grid-based planning like Cerda’s Barcelona and Olmstead’s Central Park, New York. The period from 1900 to the 1930s was characterised by movements and diverse approaches such as the Beautiful City Movement, the Decentrist Garden City, the Centrist Tower City, and the socialist planning experiments of Howard. The era post-World War II was characterised by urban sprawl driven by the spread of the automobile. Social spaces became a consideration in the 1970s as the notions of the identity of the self, the identity of the place, and Lefebvre’s right to the city became an integral part of the discourse. The contemporary era can be best understood by considering space as a matrix of public spheres. The evolution of urban public spaces, much like the city itself, has had its ebbs and flows with respect to recognising public spaces as social spaces.

5.1. Three Key Outcomes

The Understanding of Public Space as a Social Space

The first key outcome is that the city combines physical and mental spaces. Social space is produced and defined by different aspects of interactions between the users and the space. The social dimension in urban life represents the collective experience of the city. The right to the city and the right to appropriation of space are important aspects of fostering inclusivity. Space is a patchwork composed of different objects, both natural and social. It encompasses networks and pathways that facilitate and provide affordances for social exchanges. These considerations make the space more accessible socially and provide opportunities for the existence of multiple spheres. This social space provides the users with a sense of place and an immersive experience. As stated,

“the key aspect of Lefebvre’s right to the city and production of the space is that space is not a container that needs to be filled but is fabricated by our social relations and, at the same time, space is a designer of these relations” [

100].

The Understanding of Space as a Place

Sense of place refers to the various relationships between physical space and the people who inhabit it. It is unquestionable that people develop a sense of place based on a variety of factors, including their connection to its physicality over time, their strong ties to the community, their cultural affiliations with a particular place, and the physical characteristics of the space that stimulate their senses. The analysis examined place attachment to understand the sense of place. Place attachment is more functional and depends on the physical aspects of the place and the activities that make the space desired. Place identity influences self-identity, collective identity, and sense of belonging. When you traverse a space, you alter the space, which contributes to the creation of place identity, as space is not purely a container. Place identity results from the meanings attributed to the space that influences users’ behaviour. Place identity plays an important part in identification with the place.

Inclusivity Urban Public Spaces for Social Sustainability

Social inclusion relates to economic growth and to a more resilient city. This opens opportunities to participate in a better urban economy, with benefits of growth that trickle down the social hierarchy. The goal of social integration over assimilation instigates the feeling of a sense of place which improves the sense of cohesion. To promote individual well-being and create a healthy community, it's crucial to ensure that everyone feels included. Encouraging unity and cohesiveness among diverse groups is a key factor in achieving this goal. In this respect, it is important to recognise mixed neighbourhoods as culturally diverse and socially varied spaces. In addition, the significance of preserving the identity of a space for its sustainability is critical as it provides users with a sense of purpose and reality. Embracing diversity and maintaining the distinct character of a community would lead to a more vibrant society for all.

5.2. Values of Inclusivity

This study has explored the notion of inclusivity as understood through a variety of disciplines. It postulated that the loss of identity for the individual and the urban form is a gap in knowledge encompassing the idea of inclusivity as applied to urban public open spaces. Conventionally, inclusivity has always been seen as physical accessibility in public spaces and the right to equality in pay, jobs, and housing. The idea of inclusivity, as conceptualised in this study, is an aggregate of different concepts that aim towards making a place inclusive for inhabitants. Public spaces are typically planned and designed such that:

- ○

Everyone has the right of access.

- ○

Encounters between individual users are unplanned and unexceptional.

- ○

People’s behaviour towards each other is subject to rules none other than those of common norms of social civility.

Within this context, the definition of inclusivity that this research aligns with is Whyte’s notion of “

a process where there is a stimulus which affords certain interactions between completely strange people” [

19]. The study is additionally aligned with the definition of inclusivity from the index devised by Shirazi and Keivani [

81] on sustainable societies which involve the relationships at different levels between the neighbourhood, the neighbour, and the idea of neighbouring. The idea of inclusivity also works at the level of the user emphasizing that inclusion does not mean assimilation but is understood as the means to acquire a sense of belonging. A strong sense of belonging results in a sense of community. The concepts associated with inclusivity are identity and uniqueness, place identity, appropriation, accessibility, flexibility of activities and recognition of user diversity. As observed by Griffiths, an important part of the experience of exclusion is a weakened or non-existent sense of identity and pride. A key step in integrating excluded populations into the social mainstream, therefore, is to assist them to find their voice, to validate their histories and traditions, to establish a collective identity, to give expression to their experiences and aspirations, and to build self-confidence. Consequently, as seen in this study, inclusivity in an urban public open space has four outcomes with eight values of inclusivity.

5. Accessibility, Sense of Place, Conviviality and Resilience

Accessibility is a crucial aspect of inclusion and goes beyond just the physical features of a public space that provides affordances to various people in society with a certain physical disability. The components of accessibility are physical and social accessibility. Physical accessibility considers both specific elements for users with disabilities and the physical accessibility for all users. The concept of accessibility goes beyond physical accessibility and emphasises the need for social accessibility with unhindered access to public open spaces for all sectors of society. Physical accessibility in urban public open spaces will make a city more habitable, while social accessibility will make these spaces more socially inclusive and sustainable.

The second value of inclusivity is a Sense of Place. The main components of a sense of place are place attachment and place identity. The city is an arena where different domains, such as economics, physical environment, and social dynamics manifest themselves. The space and place can be analysed using the lens of these domains. The economy can create the conditions that produce space through production and trade activities. Everyday life could be improved by constructing places encompassing the citizens' bottom-up practices. In such an environment, the meanings held by users can influence their behaviour, such as their willingness to revisit, spend more time in, or engage in social practices in a particular place.

The outcome of a sense of place is place attachment, as mentioned above, which is associated with creating memories. Various concepts are used to understand and categorise the complex relationship between people and place. The term sense of place is described as a collection of social meanings: Place identity and place attachments with the spatial settings. In this regard, place attachment is seen as an emotional component to understand the process of memory creation. A place gains significance on account of its physical features and symbolic meanings. Research has shown that historic spaces draw more people to visit and linger in the open spaces. People attached to such places express more interest and awareness of the place history leading to an emotional attachment with the place [

101].

The second outcome is place identity, which plays a crucial part in the users experiencing a sense of place. The perceptual qualities of the space, such as imageability, legibility, enclosure, human scale, transparency, linkage, complexity, and coherence, can positively affect people's experience of the space. The identity of the place is a continuous process that is dependent on the activities and the behaviour of people in the space and the physical environment within the space. This notion endows the users an impression of each place visited with its unique character. Place identity is continuously evolving and, thus, an important element to be considered for a sense of inclusivity.

The third value of inclusivity is conviviality which has key components that include adaptability, appropriation, and expression. People act according to their interpretation of environmental cues. The code for understanding the language of the space should be shared to allow users to decode it. Convivial places promote tolerance and mutual exchange among inhabitants. Every setting has its own organisation which should consider the temporal aspects and the type of activities. To support the variety of activities, the code for understanding the space needs to be adaptable. Rapoport defines adaptability as the degree to which an environment helps or hinders activities [

102]. Appropriation is an important aspect of the space to have conviviality. Policies that allow temporary appropriation of space by users help foster a wide variety of expressions.

The fourth value of inclusivity is resilience. The main components for the space to have resilience is presence of good governance and place safety and comfort through place maintenance. Urban resilience is defined by the United Nations Human Settlement Program as the capacity of an urban system to respond to and absorb shocks transforming and adapting in the context of sustainable development. The resilience in relation to inclusivity can be derived from the Sustainable Development Goal, SDG 11: Sustainable cities and communities, which includes the social and economic dimensions.

Good governance of a space is important and ensures that people continue to use the urban public open space. Gehl asserts the importance of the quality of outdoor space for attracting people emphasising that in poor quality space, there is an occurrence of activities that are necessary, but a place with good governance can attract and sustain crowds, which is essential for making the place socially sustainable. Yet, “

the fragmented, one-dimensional and undifferentiated character of public space governance systems makes it very difficult for users to engage with them.[

95]” The new demands of urban public space require a new approach to governance that is cognizant of the diversity of users and activities. Finally, an urban public space affords its users a sustained feeling of safety and comfort. The physical qualities of a space play a significant role in adding vitality to the place. The vitality of the space with good governance makes the space safe and comfortable. Safer environments will see people spending more time in public open spaces.

In summary, social spaces in an existing setup will have myths and stories attached to them, which need to be considered while carrying out the reconstruction or reassembly of these territorial social spaces. People are drawn to spaces that give them a sense of place and belonging. Therefore, retaining the place's identity is essential for enriching the experience of users and creating lasting memories. These spaces should facilitate gathering, lingering on, or passing through, thus adding to the liveliness of the space and the wider context.

References

- Randel, A.E.; Galvin, B.M.; Shore, L.M.; Ehrhart, K.H.; Chung, B.G.; Dean, M.A.; Kedharnath, U. Inclusive leadership: Realizing positive outcomes through belongingness and being valued for uniqueness. Human resource management review 2018, 28, 190–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jian, I.Y.; Luo, J.; Chan, E.H. Spatial justice in public open space planning: Accessibility and inclusivity. Habitat International 2020, 97, 102122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, H. The principles of inclusive design (They include you). Architecture and the built environment, CABE 2006, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, J. Re-orienting geographies of urban diversity and coexistence: Analyzing inclusion and difference in public space. Progress in Human Geography 2019, 43, 478–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mor Barak, M.E.; Daya, P. Fostering inclusion from the inside out to create an inclusive workplace. Diversity at work: The practice of inclusion 2013, 391-412.

- Mitchell, D. Inclusive education is a multi-faceted concept. Center for Educational Policy Studies Journal 2015, 5, 9–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donnell, P.; O’Donovan, D.; Elmusharaf, K. Measuring social exclusion in healthcare settings: a scoping review. International journal for equity in health 2018, 17, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pitt, H. Modernization, Inclusion, and Intersectionality: Affordable Housing Policy and Discriminatory Characteristics of the Fair Housing Act of 1968. Community Engagement Student Work. 2022, 85. [Google Scholar]

- Peace, S.; Holland, C.; Holland, C.; Peace, S.M. Inclusive housing in an ageing society: Innovative approaches Inclusive housing in an ageing society; Policy Press: 2001; pp. 235–260.

- Nguyen, C. Adapting Organizational Inclusivity Through Empowering Gender-Diversity. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Gender Research, 2024; pp. 262–269.

- Griffin, G. Doing women's studies: employment opportunities, personal impacts and social consequences; 2nd ed.;Bloomsbury Publishing; United Kingdom, 2008; pp.13-63.

- Lynch, K.; Hack, G. Site planning; 3rd ed, MIT press; London, United Kingdom, 1984; pp 1-127.

- Shaftoe, H. Convivial urban spaces: Creating effective public places; 1st ed.; Earthscan; London, United Kingdom, 2012; pp 11-80.

- Mehta, V.; Mahato, B. Designing urban parks for inclusion, equity, and diversity. Journal of Urbanism: International Research on Placemaking and Urban Sustainability 2021, 14, 457–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitsikali, A.; Parnell, R.; McIntyre, L. The public value of child-friendly space: Reconceptualising the playground. Archnet-IJAR: International Journal of Architectural Research 2020, 14, 149–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrick, M.; McKinnon, I. Co-creating inclusive public spaces: Learnings from four global case studies on inclusive cities. The Journal of Public Space 2022, 7, 93–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akkar Ercan, M.; Oya Memlük, N. More inclusive than before?: The tale of a historic urban park in Ankara, Turkey. Urban Design International 2015, 20, 195–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, A.M. Sidewalk city: remapping public space in Ho Chi Minh City; 1st ed.; University of Chicago Press; London, United Kingdom, 2019; pp 1-26.

- Whyte, W.H. The social life of small urban spaces; 1sted.; Project for Public Space; New York, United states of America, 1980, pp 1-39 & 54-65.

- Heath, H.; Cowley, S. Developing a grounded theory approach: a comparison of Glaser and Strauss. International journal of nursing studies 2004, 41, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dewey, J. Education as engineering. Journal of curriculum studies 2009, 41, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prechtl, P.; Kelleter, F. Mead, George Herbert: Mind, Self, and Society from the Standpoint of a Social Behaviorist. In Kindlers Literatur Lexikon (KLL); Springer: 2020; pp. 1–2.

- Cooper, H.M. Organizing knowledge syntheses: A taxonomy of literature reviews. Knowledge in Society 1988, 1, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torraco, R.J. Writing Integrative Literature Reviews:Using the Past and Present to Explore the Future. Human Resource Development Review 2016, 15, 404–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sennett, R. The uses of disorder: Personal identity and city life; 1st ed.; Verso Books; London, United Kingdom, 2021; pp. 3–28 &50-84.

- Lynch, K. City sense and city design: writings and projects of Kevin Lynch; 1st ed.; MIT press, London, United Kingdom, 1995; pp. 33–82 & 771-810.

- Appleyard, D. The environment as a social symbol. Ekistics 1979, 272–281. [Google Scholar]

- Amin, A. Collective culture and urban public space. City 2008, 12, 5–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guite, H.F.; Clark, C.; Ackrill, G. The impact of the physical and urban environment on mental well-being. Public health 2006, 120, 1117–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pansare, P.; Salama, A.M. Urban Form as a Driver for Inclusivity in Public Open Spaces: A Case from Glasgow. In Proceedings of the World Congress of Architects, 2023; pp. 219–232.

- Imrie, R.; Hall, P. Inclusive design: designing and developing accessible environments; 1st ed.; Taylor & Francis,Spon Press, London, United Kingdom; 2003; pp. 3–47.

- Brenner, N. Globalisation as Reterritorialisation: The Re-scaling of Urban Governance in the European Union. Urban Studies 1999, 36, 431–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacFeely, S. Measuring the Sustainable Development Goal Indicators: An Unprecedented Statistical Challenge. Journal of Official Statistics 2020, 36, 361–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leach, J.M.; Braithwaite, P.A.; Lee, S.E.; Bouch, C.J.; Hunt, D.V.; Rogers, C.D. Measuring urban sustainability and liveability performance: the City Analysis Methodology. International journal of complexity in applied science and technology 2016, 1, 86–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrkamp, P. Geographies of migration II: The racial-spatial politics of immigration. Progress in Human Geography 2019, 43, 363–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 36. Burton, E.; Jenks, M.; Williams, K. The Compact City : A Sustainable Urban Form; 1st ed.; Taylor & Francis Group, Spon Press, London, United Kingdom; 1996; pp.7-146.

- Carter, J.; Dyer, P.; Sharma, B. Dis-placed voices: sense of place and place-identity on the Sunshine Coast. Social & Cultural Geography 2007, 8, 755–773. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, B. For Space (2005): Doreen Massey. Key texts in human geography 2008, 8, 227–235. [Google Scholar]

- Sennett, R. The new capitalism. Social Research 1997, 161–180. [Google Scholar]

- Salingaros, N.A. Complexity and urban coherence. Journal of urban design 2000, 5, 291–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sennett, R. Building and dwelling: Ethics for the city; 1st ed.; Farrar, Straus and Giroux, United States of America; 2018; pp.

- Alhusban, A.A.; Alhusban, S.A. Re-locating the identity of Amman’s city through the hybridization process. Journal of Place Management and Development 2021, 14, 81–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudjic, D. The language of cities; Penguin ;United Kingdom; 2016; pp.1-45.

- Sassen, S. The global city;2nd ed.; Princeton University Press, New York, United State of America 1991; pp 3-24.

- Salama, A.M.; Wiedmann, F. The production of urban qualities in the emerging city of Doha: urban space diversity as a case for investigating the'lived space'. Archnet-IJAR: International Journal of Architectural Research 2013, 7, 160–172. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs, J. Jane jacobs. The Death and Life of Great American Cities 1961, 21, 13–25. [Google Scholar]

- Carr, S.; Francis, M.; Rivlin, L.G.; Stone, A.M. Public space; Cambridge University Press, New York, United States of America; 1992; pp 3-187.

- Worpole, K.; Greenhalgh, L. The freedom of the city; 1st ed.; Demos, Londond, United Kingdom; 1996; pp 7-34.

- Salama, A.M.; Wiedmann, F. Demystifying Doha: On architecture and urbanism in an emerging city; 1st ed.; Routledge, London, United Kingdom; 2016; pp 1-10.

- Kweon, B.-S.; Sullivan, W.C.; Wiley, A.R. Green common spaces and the social integration of inner-city older adults. Environment and behavior 1998, 30, 832–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WELLS, H. DISABLED PERSONS ACE, 1944.

- Woodhams, C.; Corby, S. Defining disability in theory and practice: a critique of the British Disability Discrimination Act 1995. Journal of Social Policy 2003, 32, 159–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, T.; Cantillon, B.; Marlier, E.; Nolan, B. Social indicators: The EU and social inclusion; 1st ed.; Policy Press, Bristol, United Kingdom; 2002; pp 7-21.

- Brewer, M.B.; Gonsalkorale, K.; Van Dommelen, A. Social identity complexity: Comparing majority and minority ethnic group members in a multicultural society. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations 2013, 16, 529–544. [Google Scholar]

- Mielants, E. Perspectives on the origins of merchant capitalism in Europe. Review (Fernand Braudel Center) 2000, 229-292.

- Rodger, R. Political economy, ideology and the persistence of working-class housing problems in Britain, 1850–1914. International Review of Social History 1987, 32, 109–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, B.W. An historical perspective on the viability of urban diversity: lessons from socio-spatial identity construction in nineteenth-century Algiers and Cape Town. Journal of Urbanism: International Research on Placemaking and Urban Sustainability 2012, 5, 67–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, P. Cities of tomorrow: An intellectual history of urban planning and design since 1880; 4th ed.; John Wiley & Sons, England, United Kingdom; 2014; pp.

- Fourier, C. Selections Describing the Phalanstery.”. The Utopia Reader 1999, 192-199.

- Lallement, M. An Experiment Inspired by Fourier: JB Godin's Familistere in Guise. Journal of Historical Sociology 2012, 25, 31–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamin, W. The arcades project; 1st ed.; Cambridge University Press, London, United Kingdom; 1999; pp 3-14.

- Calvet, L. Barcelona: the transformation of urban form; Masters of architecture in advanced Studies, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 1979.

- Breheny, M. The compact city: an introduction. Built Environment 1992, 18, 241. [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson, C.J. Elegance and grass roots: The neglected philosophy of Frederick Law Olmsted. Transactions of the Charles S. Peirce Society 2004, 40, 335–348. [Google Scholar]

- Breheny, M. Centrists, decentrists and compromisers: views on the future of urban form. The compact city: a sustainable urban form 1996, 13-35.

- Jordan, D.P. THE CITY: Baron Haussmann and Modern Paris. The American Scholar 1992, 61, 99–106. [Google Scholar]

- Fishman, R. Urban Utopias in the Twentieth Century: Ebenezer Howard, Frank Lloyd Wright, Le Corbusier; MIT press, London, United Kingdom; 1982; pp 27-39, 122, 163, 226-234.

- Culpin, E.G. The garden city movement up-to-date; 1st ed.; Routledge; New York, United States of America; 2015 pp 8-10.

- Lee, K.-H.; Noh, J.; Khim, J.S. The Blue Economy and the United Nations’ sustainable development goals: Challenges and opportunities. Environment international 2020, 137, 105528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadler, S. The situationist city; 1st ed.; MIT press, London, United Kingdoms; 1999; pp 15-55.

- Larsen, K.E. Community architect: The life and vision of Clarence S. Stein; 1st ed.; Cornell University Press, London, United Kingdom; 2016 pp17-31 & 145,146.

- Mumford, E. Designing the modern city: Urbanism since 1850; 1st ed.; Yale University Press; London, United Kingdom; 2018; pp 6-8.

- Howe, N.; Strauss, W. The new generation gap. ATLANTIC-BOSTON- 1992, 270, 67–67. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, D. Spaces of hope; Volume 7; Univ of California Press; Los Angeles, United State of America; 2000; pp 133-180.

- Archer, J. Social theory of space: Architecture and the production of self, culture, and society. Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 2005, 64, 430–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefebvre, H. The Production of Space; Blackwell; London, United Kingdom; 1992; pp 68-70.

- Merleau-Ponty, M.; Binswanger, L. 18 The Third Force Movement. History and Systems of Psychology 2017, 335. [Google Scholar]

- De Certeau, M. Practices of space. On signs 1985, 129, 122–145. [Google Scholar]

- McNay, L. Gender, habitus and the field: Pierre Bourdieu and the limits of reflexivity. Theory, culture & society 1999, 16, 95–117. [Google Scholar]

- Erdiaw-Kwasie, M.O.; Basson, M. Reimaging socio-spatial planning: Towards a synthesis between sense of place and social sustainability approaches. Planning Theory 2018, 17, 514–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirazi, M.R.; Keivani, R. The triad of social sustainability: Defining and measuring social sustainability of urban neighbourhoods. Urban Research & Practice 2019, 12, 448–471. [Google Scholar]

- Şenol, F. Gendered sense of safety and coping strategies in public places: a study in Atatürk Meydanı of Izmir. Archnet-IJAR: International Journal of Architectural Research 2022, 16, 554–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pindell, N. Finding a right to the city: Exploring property and community in Brazil and in the United States. Vand. J. Transnat'l L. 2006, 39, 435. [Google Scholar]