Submitted:

25 May 2024

Posted:

27 May 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study design and sample

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Sociodemographic Variables, COVID-19 Burden, Family Climate, Digital Media Use and Sports Activity

2.2.2. Mental Health

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

3.2. Mental Health and Pandemic-related Outcomes by Age and Gender

3.3. Unadjusted Odds Ratios for Mental Health Outcomes with Potential Predictors

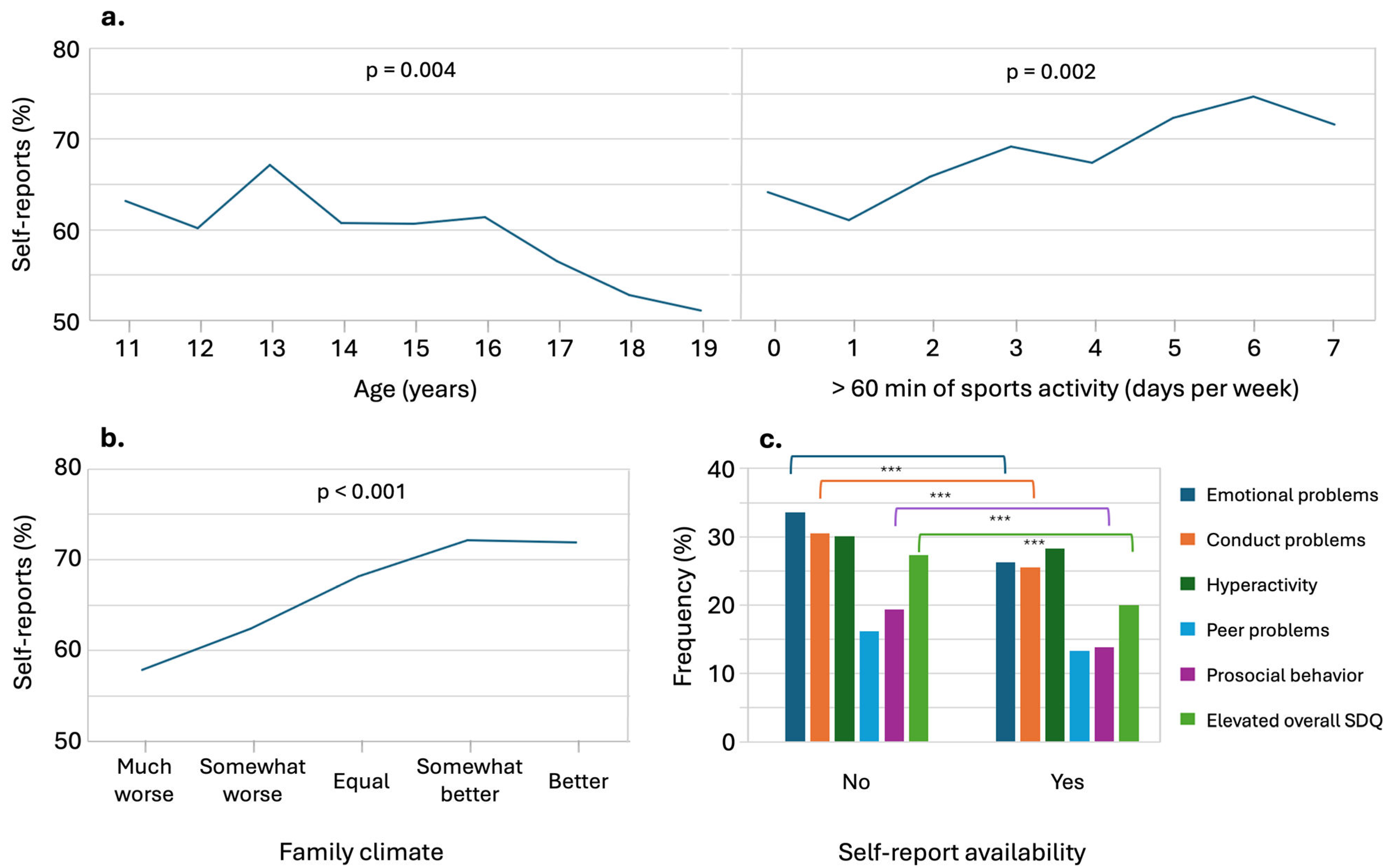

3.4. Adolescent Self-Reports and Their Association with Proxy-Reports for Predictors and Outcomes

3.4.1. Variability in Self-Report Availability and Its Association with Mental Health Outcomes in Adolescents

3.4.2. Correlations and Differences Between Proxy- and Self-Reported Predictors in Adolescent Mental Health Assessments

3.5. Parental Mental Health Problems and Proxy-reported Psychosocial Problems

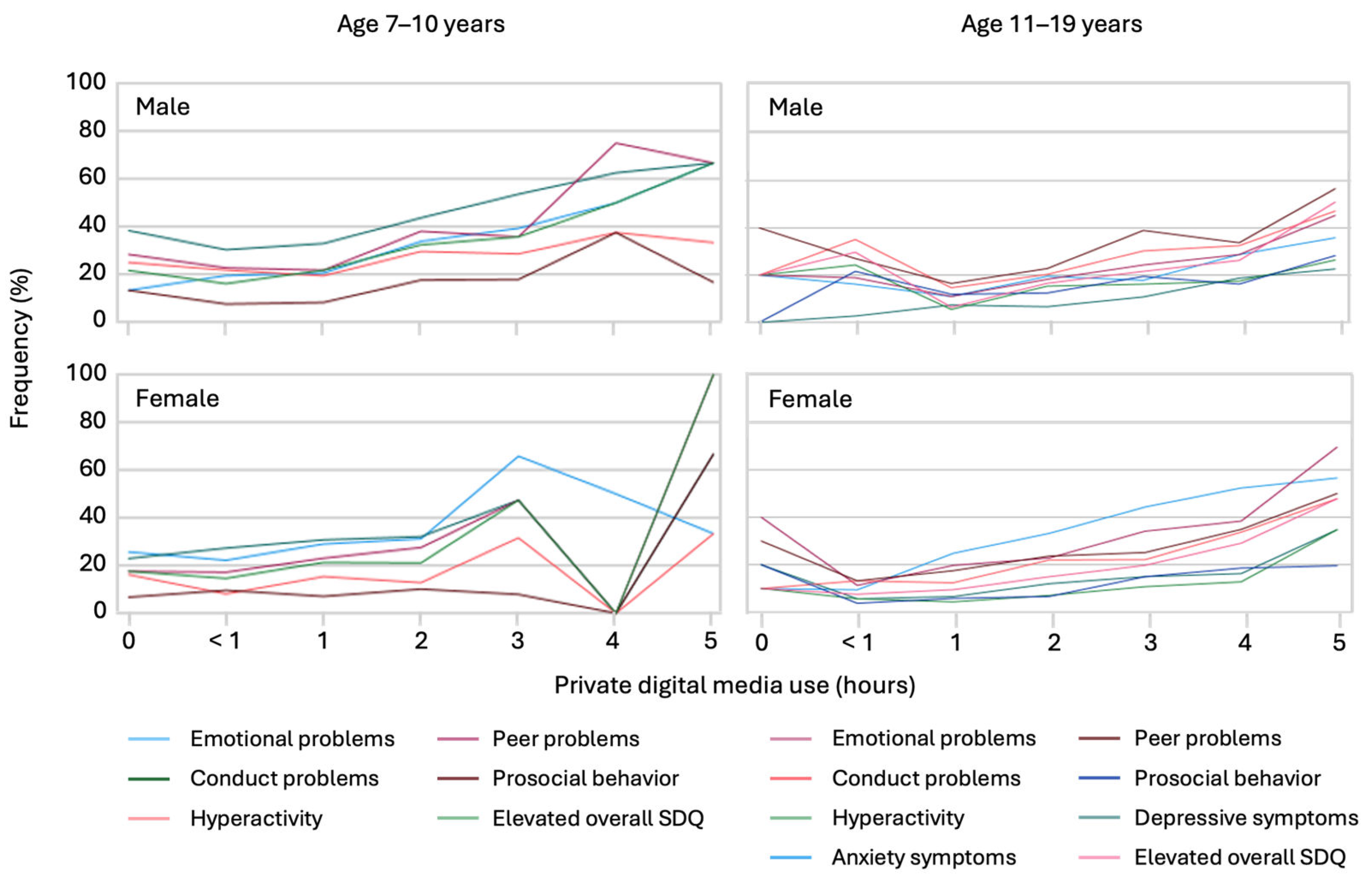

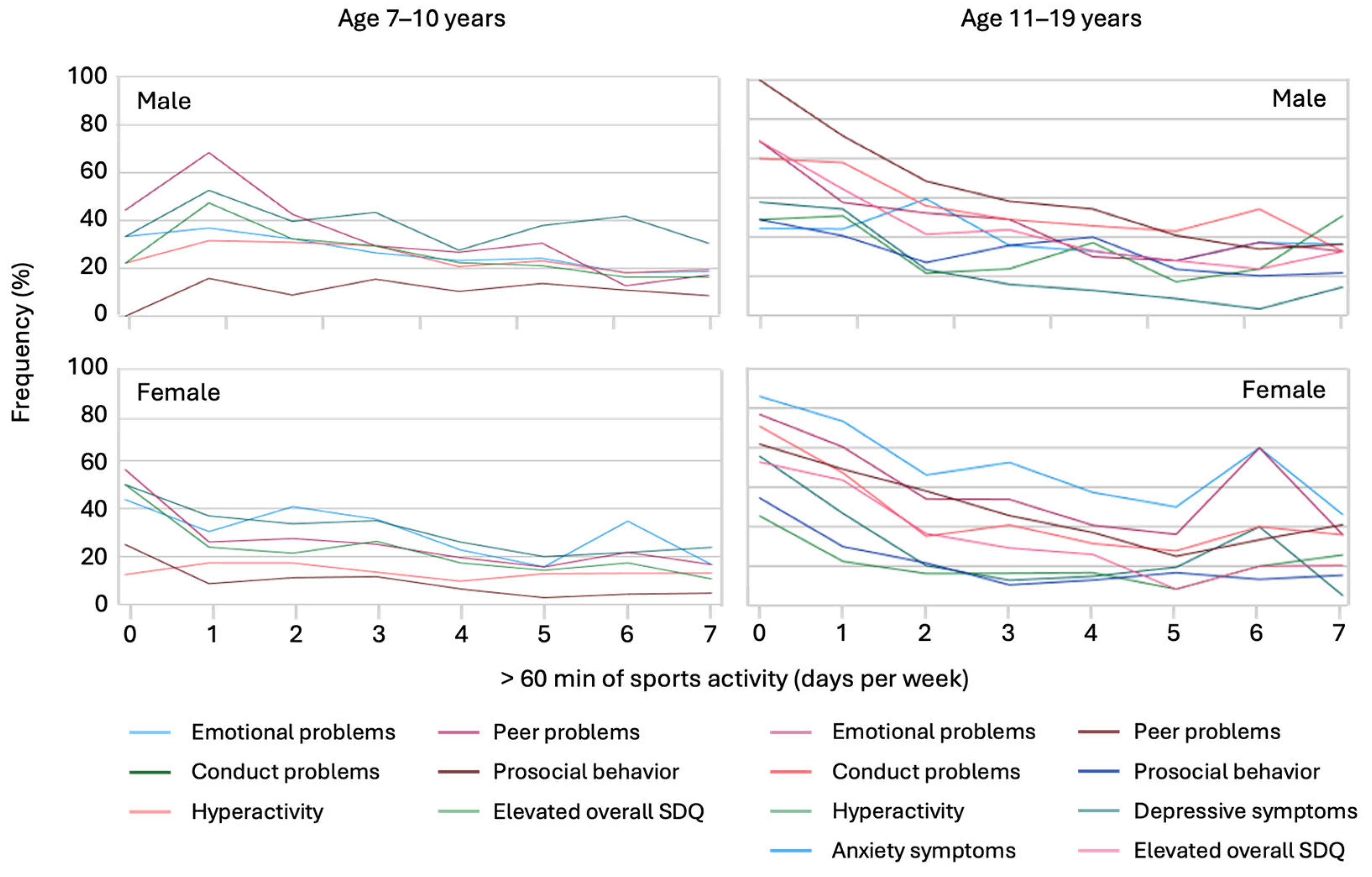

3.6. Impact of Sports Activity and Private Screen Time Use on Psychosocial Problems

4. Discussion

4.1. Implications for Public Health and Policy

4.2. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Duan, C.; Liu, L.; Wang, T.; Wang, G.; Jiang, Z.; Li, H.; Zhang, G.; Ye, L.; Li, C.; Cao, Y. Evidence Linking COVID-19 and the Health/Well-Being of Children and Adolescents: An Umbrella Review. BMC Med 2024, 22, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moeti, M.; Gao, G.F.; Herrman, H. Global Pandemic Perspectives: Public Health, Mental Health, and Lessons for the Future. Lancet 2022, 400, e3–e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, J.; Zhou, F.; Hou, W.; Heybati, K.; Lohit, S.; Abbas, U.; Silver, Z.; Wong, C.Y.; Chang, O.; Huang, E.; et al. Prevalence of Mental Health Symptoms in Children and Adolescents during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Meta-Analysis. Ann NY Acad Sci 2023, 1520, 53–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Health Behaviour in School-aged Children. A Focus on Adolescent Mental Health and Wellbeing in Europe, Central Asia and Canada. Health Behaviour in School-Aged Children International Report from the 2021/2022 Survey. Volume 1. Available online: https://www.who.int/europe/publications/i/item/9789289060356 (accessed on 3 May 2024).

- Adorjan, K.; Stubbe, H.C. Insight into the Long-Term Psychological Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2023, 273, 287–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ravens-Sieberer, U.; Devine, J.; Napp, A.-K.; Kaman, A.; Saftig, L.; Gilbert, M.; Reiss, F.; Löffler, C.; Simon, A.; Hurrelmann, K.; et al. Three Years into the Pandemic: Results of the Longitudinal German COPSY Study on Youth Mental Health and Health-Related Quality of Life 2022.

- Cusinato, M.; Iannattone, S.; Spoto, A.; Poli, M.; Moretti, C.; Gatta, M.; Miscioscia, M. Stress, Resilience, and Well-Being in Italian Children and Their Parents during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020, 17, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozzola, E.; Ferrara, P.; Spina, G.; Villani, A.; Roversi, M.; Raponi, M.; Corsello, G.; Staiano, A. The Pandemic within the Pandemic: The Surge of Neuropsychological Disorders in Italian Children during the COVID-19 Era. Ital J Pediatr 2022, 48, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meda, N.; Pardini, S.; Slongo, I.; Bodini, L.; Zordan, M.A.; Rigobello, P.; Visioli, F.; Novara, C. Students’ Mental Health Problems before, during, and after COVID-19 Lockdown in Italy. J Psychiatr Res 2021, 134, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbieri, V.; Wiedermann, C.J.; Kaman, A.; Erhart, M.; Piccoliori, G.; Plagg, B.; Mahlknecht, A.; Ausserhofer, D.; Engl, A.; Ravens-Sieberer, U. Quality of Life and Mental Health in Children and Adolescents after the First Year of the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Large Population-Based Survey in South Tyrol, Italy. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022, 19, 5220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbieri, V.; Wiedermann, C.J.; Piccoliori, G.; Mahlknecht, A.; Plagg, B.; Ausserhofer, D.; Ravens-Sieberer, U.; Engl, A. Evolution of Youth’s Mental Health and Quality of Life during the COVID-19 Pandemic in South Tyrol, Italy: Comparison of Two Representative Surveys. Children 2023, 10, 895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daimer, S.; Mihatsch, L.L.; Neufeld, S.A.; Murray, G.K.; Knolle, F. Investigating the Relationship of COVID-19 Related Stress and Media Consumption with Schizotypy, Depression, and Anxiety in Cross-Sectional Surveys Repeated throughout the Pandemic in Germany and the UK. eLife 11, e75893. [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, B.; Biswas, U.N.; Mansukhani, R.T.; Casarín, A.V.; Essau, C.A. The Impact of COVID-19 Lockdown on Internet Use and Escapism in Adolescents. Revista de psicología clínica con niños y adolescentes 2020, 7, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravens-Sieberer, U.; Kaman, A.; Erhart, M.; Otto, C.; Devine, J.; Löffler, C.; Hurrelmann, K.; Bullinger, M.; Barkmann, C.; Siegel, N.A.; et al. Quality of Life and Mental Health in Children and Adolescents during the First Year of the COVID-19 Pandemic: Results of a Two-Wave Nationwide Population-Based Study. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Autonome Provinz Bozen - Südtirol. Available online: https://astat.provinz.bz.it/de/bildung-kultur.asp (accessed on 4 May 2024).

- König, W.; Lüttinger, P.; Müller, W. A Comparative Analysis of the Development and Structure of Educational Systems: Methodological Foundations and the Construction of a Comparative Educational Scale; Universität Mannheim, Institut für Sozialwissenschaften, 1988.

- Brauns, H.; Scherer, S.; Steinmann, S. The CASMIN Educational Classification in International Comparative Research. In Advances in Cross-National Comparison: A European Working Book for Demographic and Socio-Economic Variables; Hoffmeyer-Zlotnik, J.H.P., Wolf, C., Eds.; Springer US: Boston, MA, 2003; pp. 221–244 ISBN 978-1-4419-9186-7.

- Birmaher, B.; Brent, D.A.; Chiappetta, L.; Bridge, J.; Monga, S.; Baugher, M. Psychometric Properties of the Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders (SCARED): A Replication Study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1999, 38, 1230–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weitkamp, K.; Romer, G.; Rosenthal, S.; Wiegand-Grefe, S.; Daniels, J. German Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders (SCARED): Reliability, Validity, and Cross-Informant Agreement in a Clinical Sample. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health 2010, 4, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crocetti, E.; Hale, W.W.; Fermani, A.; Raaijmakers, Q.; Meeus, W. Psychometric Properties of the Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders (SCARED) in the General Italian Adolescent Population: A Validation and a Comparison between Italy and The Netherlands. J Anxiety Disord 2009, 23, 824–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Argenio, P.; Minardi, V.; Mirante, N.; Mancini, C.; Cofini, V.; Carbonelli, A.; Diodati, G.; Granchelli, C.; Trinito, M.O.; Tarolla, E. Confronto Tra Due Test per La Sorveglianza Dei Sintomi Depressivi Nella Popolazione. Not Ist Super Sanità 2013, 26. [Google Scholar]

- Schuler, M.; Strohmayer, M.; Mühlig, S.; Schwaighofer, B.; Wittmann, M.; Faller, H.; Schultz, K. Assessment of Depression before and after Inpatient Rehabilitation in COPD Patients: Psychometric Properties of the German Version of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9/PHQ-2). J Affect Disord 2018, 232, 268–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodman, R. The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire: A Research Note. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 1997, 38, 581–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodman, R. Psychometric Properties of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2001, 40, 1337–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ludwig-Walz, H.; Dannheim, I.; Pfadenhauer, L.M.; Fegert, J.M.; Bujard, M. Increase of Depression among Children and Adolescents after the Onset of the COVID-19 Pandemic in Europe: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health 2022, 16, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, L.; Schauber, S.K.; Holt, T.; Helland, M.S. Longitudinal Covid-19 Effects on Child Mental Health: Vulnerability and Age Dependent Trajectories. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health 2023, 17, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gohari, M.R.; Patte, K.A.; Ferro, M.A.; Haddad, S.; Wade, T.J.; Bélanger, R.E.; Romano, I.; Leatherdale, S.T. Adolescents’ Depression and Anxiety Symptoms During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Longitudinal Evidence From COMPASS. J Adolesc Health 2023, S1054-139X(23)00390-7. [CrossRef]

- Oostrom, T.G.; Cullen, P.; Peters, S.A. The Indirect Health Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Children and Adolescents: A Review. J Child Health Care 2022, 13674935211059980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babore, A.; Trumello, C.; Lombardi, L.; Candelori, C.; Chirumbolo, A.; Cattelino, E.; Baiocco, R.; Bramanti, S.M.; Viceconti, M.L.; Pignataro, S.; et al. Mothers’ and Children’s Mental Health During the COVID-19 Pandemic Lockdown: The Mediating Role of Parenting Stress. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev 2023, 54, 134–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babore, A.; Trumello, C.; Lombardi, L.; Candelori, C.; Chirumbolo, A.; Cattelino, E.; Baiocco, R.; Bramanti, S.M.; Viceconti, M.L.; Pignataro, S.; et al. Mothers’ and Children’s Mental Health During the COVID-19 Pandemic Lockdown: The Mediating Role of Parenting Stress. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pieh, C.; Dale, R.; Jesser, A.; Probst, T.; Plener, P.L.; Humer, E. The Impact of Migration Status on Adolescents’ Mental Health during COVID-19. Healthcare (Basel) 2022, 10, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dale, R.; O’Rourke, T.; Humer, E.; Jesser, A.; Plener, P.L.; Pieh, C. Mental Health of Apprentices during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Austria and the Effect of Gender, Migration Background, and Work Situation. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021, 18, 8933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thom, J.; Jonas, B.; Reitzle, L.; Mauz, E.; Hölling, H.; Schulz, M. Trends in the Diagnostic Prevalence of Mental Disorders, 2012-2022—Using Nationwide Outpatient Claims Data for Mental Health Surveillance. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2024, arztebl.m2024.0052. [CrossRef]

- Magson, N.R.; Freeman, J.Y.A.; Rapee, R.M.; Richardson, C.E.; Oar, E.L.; Fardouly, J. Risk and Protective Factors for Prospective Changes in Adolescent Mental Health during the COVID-19 Pandemic. J Youth Adolesc 2021, 50, 44–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosozawa, M.; Ando, S.; Yamaguchi, S.; Yamasaki, S.; DeVylder, J.; Miyashita, M.; Endo, K.; Stanyon, D.; Knowles, G.; Nakanishi, M.; et al. Sex Differences in Adolescent Depression Trajectory Before and Into the Second Year of COVID-19 Pandemic. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2024, 63, 539–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- . Li, T.; Li, C.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, N.; Li, J.; Ren, Q.; Li, W.; Li, Z.; Huang, G.; Yan, J. Mental Health Difficulties and Related Factors in Chinese Children and Adolescents during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Cross-Sectional Study. J Pediatr (Rio J) 2024, S0021-7557(24)00033-0. [CrossRef]

- Loy, J.K.; Klam, J.; Dötsch, J.; Frank, J.; Bender, S. Exploring Adolescent Mental Health during the COVID-19 Crisis - Strengths and Difficulties. Front Public Health 2024, 12, 1357766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, L.R.; Bitsko, R.H.; O’Masta, B.; Holbrook, J.R.; Ko, J.; Barry, C.M.; Maher, B.; Cerles, A.; Saadeh, K.; MacMillan, L.; et al. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Parental Depression, Antidepressant Usage, Antisocial Personality Disorder, and Stress and Anxiety as Risk Factors for Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) in Children. Prev Sci 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicari, S.; Pontillo, M. Developmental Psychopathology in the COVID-19 Period. COVID-19 Pandemic Impact on Children and Adolescents’ Mental Health. Psychiatr Danub 2021, 33, 33–35. [Google Scholar]

- Ko, W.; Jeong, H. Association between Children with Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder and Parental Mental Health: Data from the 2011-2020 Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. J Affect Disord 2024, 350, 544–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoder, R.; Michaud, A.; Feagans, A.; Hinton-Froese, K.E.; Meyer, A.; Powers, V.A.; Stalnaker, L.; Hord, M.K. Family-Based Treatment for Anxiety, Depression, and ADHD for a Parent and Child. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2024, 21, 504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, M.; Bai, Y.; Fu, M.; Huang, N.; Ahmed, F.; Shahid, M.; Wang, X.; Liu, C.; Feng, X.L.; Guo, J. The Associations Between Parental Burnout and Mental Health Symptoms Among Chinese Parents With Young Children During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Front Psychiatry 2022, 13, 819199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shoshani, A.; Kor, A. The Longitudinal Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Adolescents’ Internalizing Symptoms, Substance Use, and Digital Media Use. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.; Belfry, K.D.; Crawford, J.; MacDougall, A.; Kolla, N.J. COVID-19-Related Anxiety and the Role of Social Media among Canadian Youth. Front Psychiatry 2023, 14, 1029082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, S.; Lai, X.; Li, Y.; Cui, Y.; Wang, Y. Beyond Screen Time: The Different Longitudinal Relations between Adolescents’ Smartphone Use Content and Their Mental Health. Children (Basel) 2023, 10, 770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mougharbel, F.; Chaput, J.-P.; Sampasa-Kanyinga, H.; Colman, I.; Leatherdale, S.T.; Patte, K.A.; Goldfield, G.S. Longitudinal Associations between Different Types of Screen Use and Depression and Anxiety Symptoms in Adolescents. Front Public Health 2023, 11, 1101594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions, and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of the MDPI and/or editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions, or products referred to in the content. |

| Children aged 7–19 years (proxy-report) n = 4,525 |

Children aged 11–19 years (self-report) n = 1,828 |

|||||

| M (SD) | M (SD) | |||||

| Age of children, years (y) | 12.57 (3.55) | 14.46 (2.316) | ||||

| Age of the parent, years (y) | 45.27 (5.28) | 47.36 (5.54) | ||||

| % | % | |||||

| Age groups | 7–10 y 32.9 |

11–13 y 24.1 |

14–19 y 43.0 |

7–10 y - |

11–13 y 37.9 |

14–19 y 62.1 |

| Gender | Male 49.3 |

Female 50.5 |

Other 0.2 |

Male 49.8 |

Female 49.9 |

Other 0.1 |

| Gender of the parents | Male 10.1 |

Female 89.8 |

Other 0.2 |

Male 10.1 |

Female 89.8 |

Other 0.1 |

| Migration background | No 84.1 |

Yes 9.5 |

n.d. 6.4 |

No 90.6 |

Yes 8.8 |

n.d. 0.6 |

| Parental education | Low 22.7 |

Moderate/high 73.2 |

n.d. 4.1 |

Low 25.3 |

Moderate/high 71.4 |

n.d. 3.3 |

| Single parenthood | No 89.1 |

Yes 8.5 |

n.d. 6.4 |

No 90 |

Yes 10 |

n.d. 0 |

| Residency | Urban 24.5 |

Rural 75.5 |

Urban 27.3 |

Rural 72.7 |

||

| Parental mental health problems | Yes 3.8 |

No 87.2 |

n.d. 8.9 |

Yes 3.7 |

No 96.2 |

n.d. 0.1 |

| COVID-19 related burden | ||||||

| Parent: Extreme/reasonably burdened | Yes 35.6 |

No 55.7 |

n.d. 8.7 |

Yes 39.3 |

No 60.6 |

n.d. 0.1 |

| Child: extreme/reasonalby burdend | Yes 8 |

No 78.7 |

n.d. 13.3 |

Yes 4.7 |

No 86.8 |

n.d. 8.5 |

| Lower family climate (much/little) | Yes 18.3 |

No 71.4 |

n.d. 10.3 |

Yes 14.2 |

No 79.7 |

n.d. 6.1 |

| More use of digital media (much) | Yes 46.7 |

No 42.1 |

n.d. 11.2 |

Yes 43.9 |

No 43.1 |

n.d. 13 |

| Non COVID-19-related | ||||||

| 60+ minutes of sports (3+ days) | Yes 58.9 |

No 29.8 |

n.d. 11.3 |

Yes 59.8 |

No 28.8 |

n.d. 11.4 |

| School use of digital media (3+ hours) | Yes 9.1 |

No 78 |

n.d. 12.9 |

Yes 15.3 |

No 70.5 |

n.d. 14.2 |

| Private use of digital media (3+ hours) | Yes 60.8 |

No 27.6 |

n.d. 11.6 |

Yes 41.6 |

No 43.8 |

n.d. 14.6 |

| Variable | Age Group 7–10 Years | Odds Ratio 1 | Age Group 11–19 Years | Odds Ratio 1 | ||||

| Total (%) |

Boys (%) |

Girls (%) |

Total (%) |

Boys (%) |

Girls (%) |

|||

| Outcomes in Self-reports | ||||||||

| PHQ-2: Symptoms of depression (n = 1,603) | 11.8 | 10.1 | 13.3 | 1.371 [1.008;1.864]* | ||||

| SCARED: Symptoms of anxiety (n = 1,565) | 27.7 | 19.3 | 35.8 | 2.333 [1.853;2.937]*** | ||||

| Outcomes in Proxy- Reports | ||||||||

| SDQ: Symptoms of emotional problems (n = 3,715) | 26.8 | 24.5 | 29.2 | n.s. | 29.1 | 25.1 | 33.1 | 1.498 [1.256;1.786]*** |

| SDQ: Symptoms of conduct problems (n = 3,715) | 33.4 | 36.8 | 29.9 | 0.725 [0.572;0.919]** | 27.3 | 28.9 | 25.8 | n.s |

| SDQ: Symptoms of hyperactivity (n = 3,715) | 19.0 | 24.0 | 13.6 | 0.510 [0.380;0.685]*** | 14.2 | 17.9 | 10.7 | 0.543 [0.431;0.685]*** |

| SDQ: Symptoms of peer problems (n = 3,715) | 25.7 | 27.6 | 23.6 | n.s. | 28.9 | 30.8 | 27.1 | 0.815 [0.685;0.971]* |

| SDQ: Symptoms of prosocial problems (n = 3,715) | 10.2 | 11.6 | 8.8 | n.s. | 15.5 | 18.6 | 12.5 | 0.624 [0.499;0.780]*** |

| SDQ: Overal elevated SDQ (n = 3,715) | 22.3 | 23.7 | 20.8 | n.s. | 22.2 | 22.6 | 21.7 | n.s. |

| Predictors in Self-reports | ||||||||

| Children’s pandemic related burden | 5.2 | 4.8 | 5.5 | n.s. | ||||

| Pandemic related extended use of digital media | 50.4 | 48.6 | 52.1 | n.s. | ||||

| Pandemic related lower family climate | 15.0 | 15.0 | 15.1 | n.s. | ||||

| Daily use of digitl media for school concerns (3+ hours) | 17.9 | 15.5 | 20.2 | 1.382 [1.067;1.789]* | ||||

| Daily use of digitl media for private concerns (3+ hours) | 49.1 | 51.1 | 47.1 | n.s. | ||||

| More than 60 min. of sports a week (3+ days) | 67.6 | 75.1 | 60.2 | 0.501 [0.406;0.619]*** | ||||

| Predictors in Proxy- Reports | ||||||||

| Parental pandemic related burden | 37.6 | 37.4 | 37.7 | n.s. | 39.7 | 40.0 | 39.4 | n.s. |

| Children’s pandemic related burden | 4.9 | 4.6 | 5.2 | n.s. | 11.4 | 10.6 | 12.2 | n.s. |

| Pandemic related extended use of digital media | 40.0 | 40.7 | 39.3 | n.s. | 58.8 | 58.1 | 59.5 | n.s. |

| Pandemic related lower family climate | 15.6 | 16.1 | 15.0 | n.s. | 22.7 | 23.3 | 22.2 | n.s. |

| Daily use of digitl media for school concerns (3+ h) | 0.6 | 0.3 | 1.0 | n.s. | 15.1 | 13.0 | 17.0 | 1.371 [1.105;1.699]** |

| Daily use of digitl media for private concerns (3+ h) | 7.2 | 7.1 | 7.2 | n.s. | 43.2 | 44,5 | 42.0 | n.s. |

| More than 60 min. of sports a week (3+ days) | 79.2 | 84.9 | 73.3 | 0.491 [0373;0.645]*** | 60.1 | 68.5 | 52.1 | 0.499 [0.426;0.584]*** |

| Predictor (OR) 1 | Symptoms of Anxiety | Depressive symptoms | Emotional Problems | Conduct Problems | Hyperactivity | Peer Problems | Prosocial Behavior | SDQ Overall |

| Self-report | Self-report | Proxy-report | Proxy-report | Proxy-report | Proxy-report | Proxy-report | Proxy-report | |

| Children’s burden (dichotomized) | 5.55 [3.418;9.04]*** | 9.24 [5.78;14.79] | 6.36 [5.02;8.05]*** | 3.07 [1.97;4.76]*** | 3.07 [2.41;3.91]*** | 4.54 [2.898;7.11]*** | 2.469 [1.90;3.19]*** | 5.87 [4.634;7.43]*** |

| Extended digital media use (dichotomized) | 1.684 [1.34;2.11]*** | 2.06 [1.49;2.83]*** | 2.16 [1.87;2.50]*** | 1.53 [1.33;1.76]*** | 1.44 [1.201;1.72]*** | 1.61 [1.39;1.86]*** | 1.48 [1.23;1.79]*** | 2.23 [1.71;2.90]*** |

| Daily private screen time (hours) | 1.21 [1.12:1.30]*** | 1.37 [1.22;1.54]*** | 1.33 [1.26;1.39]*** | 1.18 [1.13;1.24]*** | 1.15 [1.09;1.22]*** | 1.26 [1.20;1.33] | 1.38 [1.30;1.48]*** | 1.349 [1.27;1.41]*** |

| Daily school screen time use (hours) | 1.35 [1.21;1.48]*** | 1.35 [1.22;1.49]*** | 1.14 [1.08;1.20]*** | 0.89 [0.85;0.94]*** | 0.86 [0.80;0.92]*** | 1.10 [1.04;1.16]*** | 1.10 [1.03;1.17]** | n.s. |

| Days of sports activitiy ≥ 60 minutes | 0.83 [0.78;0.88]*** | 0.70 [0.64;0.76]*** | 0.81 [0.78;0.84]*** | 0.899 [0.86;0.92]*** | n.s. | 0.80 [0.77;0.83]*** | 0.84 [0.80;0.88]*** | 0.81 [0.78;0.85]*** |

| Lower family climate (dichotomized) | 3.93 [2.95;5.23]*** | 3.98 [2.84;5.58]*** | 5.23 [4.438;6.17]*** | 4.01 [3.40;4.72]*** | 3.25 [2.69;3.91]*** | 2.94 [2.50;3.46]*** | 2.52 [2.06;3.07]*** | 6.05 [5.08;7.22]*** |

| Proxy-report | Proxy-report | Proxy-report | Proxy-report | Proxy-report | Proxy-report | Proxy-report | Proxy-report | |

| Parental burden | 1.76 [1.41;2.21]*** | 1.70 [1.25;2.30]** | 2.99 [2.59;3.46]*** | 1.90 [1.65;2,19]*** | 2.22 [1.86; 2.64]*** | 1.89 [1.64;2.18]*** | 1.37 [1.14;1.65]** | 2.89 [2.46;3.38]*** |

| Age | 1.12 [1.07;1.18]*** | 1.26 [1.17;1,34]*** | 1.03 [1.01;1.05]** | 0.95 [0.93;}.97]*** | 0.94 [0.92;0.97]*** | n.s. | 1.07 [1.05;1.10]*** | n.s. |

| Gender | 2.33 [1.85;2.94]*** | 1.37 [1.01;1.86]* | 1.41 [31.22;1.62]*** | 0.80 [0.70;0.92]*** | 0.53 [0.44;0.63]*** | 0.83 [0.72;0.96]* | 0.69 [0.57;0.83]*** | n.s. |

| Single parenthood | 1.61 [1.14;2.28]** | n.s. | 1.56 [1.23;1.98]*** | n.s. | n.s. | 1.71 [2.35;2.17]*** | 1.57 [1.17;2.11]** | 1.55 [1.20;2.00]** |

| Migration background | n.s. | 1.76 [1.128;2.78]* | 1.31 [1.05;1.64]* | n.s. | 1.33 [1.01;1,74]* | 1.36 [1.09;1.70]** | n.s. | 1.31 [1.03;1.68]* |

| Parental low education | n.s. | n.s. | 1.19 [1.01;1.41]* | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | 1.22 [1.02;1.47]* |

| Parental mental health problems | n.s. | n.s. | 3.14 [2.28;4.31]*** | 1.78 [1.29;2.46]*** | 2.58 [1.83;3.63]*** | 1.90 [1.38;2.63]*** | 1.51 [1.01;2.26]* | 2.87 [2.07;3.98]*** |

| Urban residency | 1.33 [1.04;1.70]* | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).