Submitted:

26 May 2024

Posted:

27 May 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Profile of Palm Oil Plantations in the Study Area

3.3.1. A Brief History of Palm Oil Companies

3.3.2. Managing Business Partnerships between Plantations and Farmers/Landowners

- The produced TBS, which belongs to the landowner and the company, is sold to the company’s commitment at market price, and the proceeds from this sale are called ‘gross income’.

- 40% of the TBS sales price, called ‘operational costs’, are deducted from the gross income, and the difference is called ‘operating results’.

- PT.SPL, the landowner and the company will jointly return investment costs by deducting 30% of their operating results in the first year, 40% in the second year, 50% in the third year and so on. The remaining profit, called ‘net income’, will be divided between the landowner (40%) and the company (60%).

- PT.DJL divides its investment and operational costs as 60% for the company and 40% for the landowners. As for net income, the landowner receives 20%, whilst the company receives 80%. PT.SPL decides its profit sharing pattern based only on land area and not on land productivity. By contrast, PT.DJL takes land productivity into consideration when dividing its profits.

- After paying off the cost of building the plantations (investment cost), the operating results described in point 3 above will no longer be deducted by 50%. Therefore, the operating results become the net income of each party.

- The following rules that govern investment costs are regulated in Article 3 of the agreement:

- The company agrees that building the plantations costs IDR 35,000,000,00 per hectare.

- The landowner bears 40% of this cost (IDR 14,000,000,00 per hectare), whilst the company bears 60% (IDR 21,000,000,00 per hectare)

- The investment costs use the financial facilities of the company at an annual interest of 12%.

- The repayment period for the investment costs will be determined based on the production results of the plantation, which will be monitored. The remaining debt for each party will also be calculated every month.

3.3.3. Partner Institutions

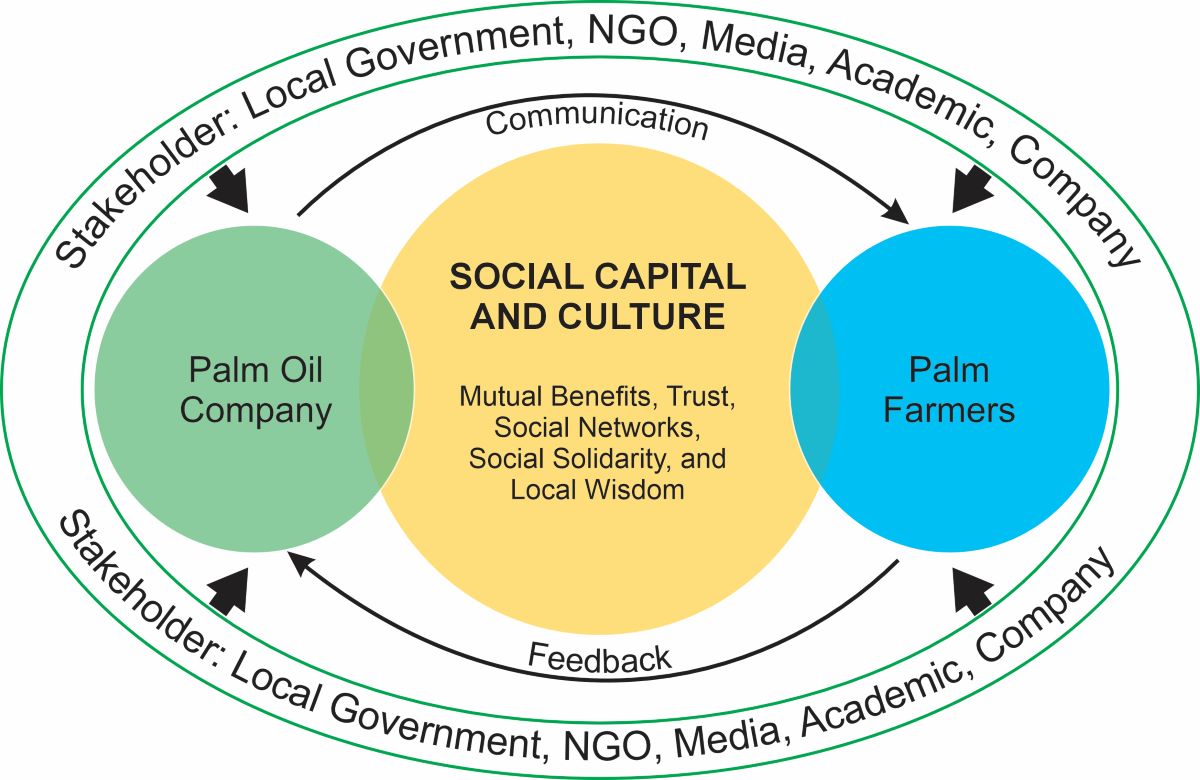

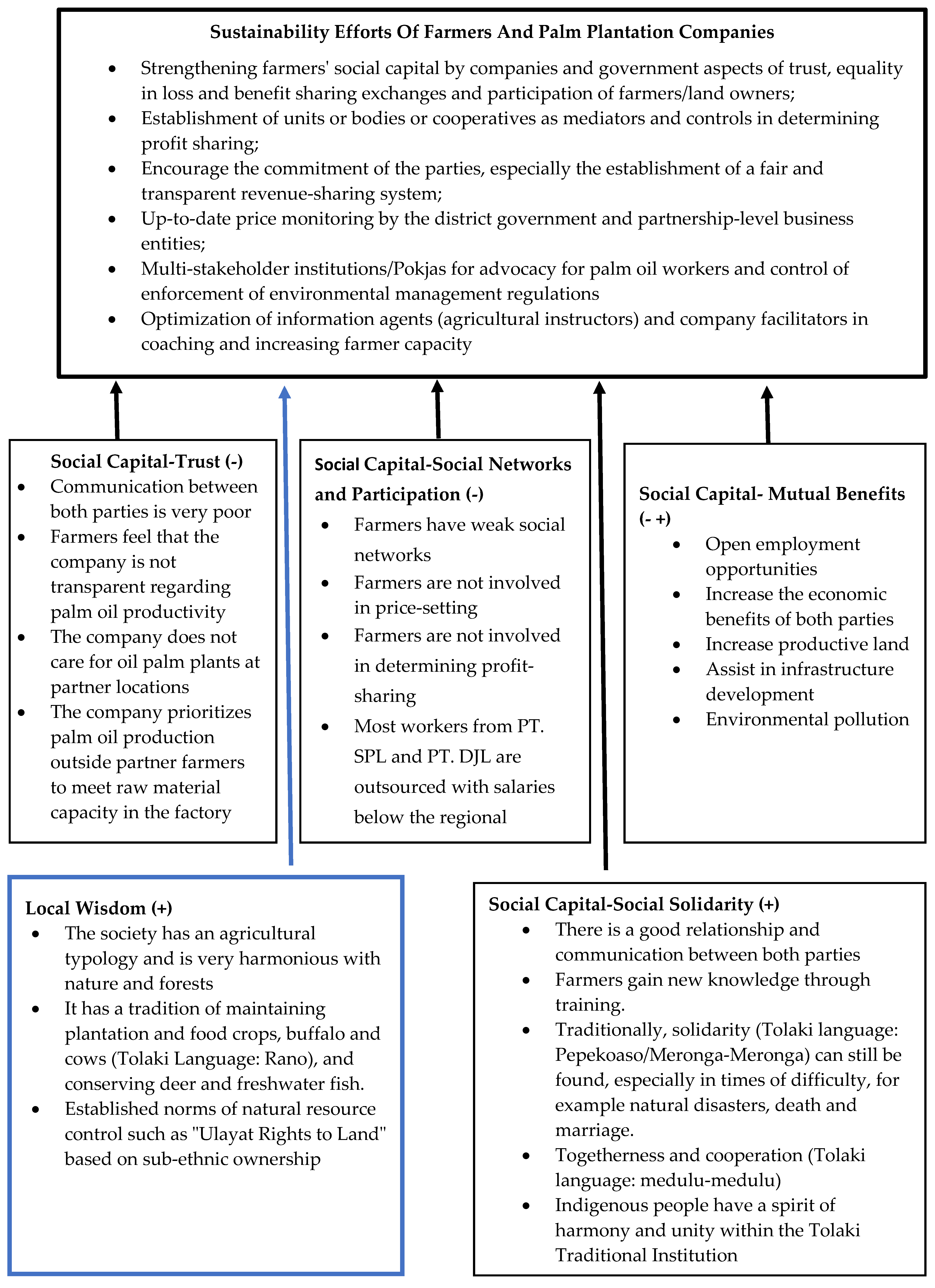

3.2. Social Capital Practice

3.2.1. Trust

3.2.2. Social Networking and Participation

|

Respondents’ Social Networks and Participation |

Respondents’ Assessments (Score=1-5) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| SPL DJL (N=100) | DJL (N=109) |

PTPN 14 (N=111) | |

| Economics | Score/(N) | Score/(N) | Score/(N) |

| Access to companies related to employment opportunities Productivity transparency of plasma/community palm oil plantations Access market price information Family participation in savings and loan cooperatives |

4 (95) 3 (100) 2 (85) 2 (50) |

4 (105) 3 (43) 2 (60) 2 (15) |

4 (80) 2 (77) 2 (55) 2 (35) |

| Ecology | Score /(N) | Score /(N) | Score /(N) |

| Involvement of environmental NGOs Government attention to the environment Farmer participation in protecting environmental pollution Cooperate in preventing land damage |

4 (81) 3 (83) 3 (75) 3 (97) |

4 (89) 3 (92) 3 (105) 3 (87) |

3 (50) 3 (90) 3 (75) 3 (93) |

| Social | Score/(N) | Score/(N) | Score/(N) |

| The education level of farmer families increases Intensity of agricultural extension There is communication between farmers Communication between the community and the company Communication between farmers and community leaders |

4 (85) 3 (72) 3 (85) 2 (70) 4 (98) |

4 (60) 2 (68) 3 (78) 2 (39) 4 (92) |

4 (60) 3 (70) 4 (82) 2 (41) 4 (90) |

3.2.3. Social Solidarity

| No | Stakeholder | Stakeholder Statement of Solidarity in Palm Oil Plantation Business |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Land Owners (Farmers) | Landowners/farmers hope for support or facilities from companies to be facilitated by the government |

| 2 | NGOs | NGOs hope that the role of palm oil companies can protect the environment and ensure fair welfare for land owners/farmers. |

| 3 | The Government | The Government of the Regent of North Konawe, through the Plantation and Horticulture Service, instructed the Company to commit to fulfilling permits as a condition for building the factory. The parties need to help investors continue to operate. |

| 4 | Academics | Provide support so that companies are committed to realizing the welfare of farmers/land owners who are their partners while still paying attention to institutional strengthening, improving cultivation technology and waste management for the benefit of increasing palm oil productivity, Provide a role in managing palm oil processing factories, providing labor wages and capacity-building training to farmers/land owners. Moreover, the sustainability aspect should not be ignored from an ecological perspective. Recommend that the government really strengthen the position of farmers, especially in terms of implementing regional minimum wages for workers, disclosing information on palm oil prices, and launching Regional Regulations on Sustainable Palm Oil Management. |

| Regional Legislative Member | Increase awareness of environmental issues and strengthen institutions. The existence of an oil palm plantation company shows its commitment to realizing the welfare of partner farmers, utilizing palm oil products from the North Konawe Regency. . |

|

| Youth Farmers (Young generation) | The younger generation (land-owning families) specifically want their parents to improve their skills in managing oil palm plantations |

3.2.4. Reciprocal Benefits

| No. | Stakeholder | Informant statement |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Land Owner 01 | I feel that from the first year to 2019, almost the same results, or there is no increase in results There are still fewer employees in companies who get BPJS for employment. |

| 2 | Land Owner 02 | Company PT. SPL and PT. DJL operate because of the kindness of the landowners, in this case, the farmers, who do not own the core land until now. Care or maintenance of oil palm plants should be done seriously Improvement of garden roads to facilitate the transportation of palm oil. Not consistent in revenue sharing and should be by the agreement. |

| 3 | Land Owner 03 (Land in Wiwirano Village) |

The oil palm industry promised a factory, but so far, it has not been realized The workforce is a concern for the Company Forming BUMDES as a medium for increasing the capacity of farmers, |

| 4 | Village Head in Mantasole Village | The price is the first point we should pay attention to; far from what is expected. The price is not negotiable. There is a need for training for farmers by companies and extension workers |

| 5 | Land Owner 04 | I am very grateful to the PTPN XIV oil palm company because my son’s school, which was stopped for a while, can return to school again. By reactivating cooperatives, farmers can help each other overcome existing problems. |

| 6 | PTPN Nusantara XIV Kebun Asera Unit |

There is no factory yet for the sale of Tandang Buah Segar (TBS) from farmers; we work with partner companies SPL and DJL to buy TBS from us, but there are farmers who jointly do not sell to their partner companies, and as a result, credit instalments are not smooth. |

| 8 | Public Relation PT. SPL | The system used is for profit, Another problem with the Company is that this community freely cuts palm oil on the ground to be used as a vegetable at the festival. Even though the palm oil they cut is still productive The Company PT. SPL is about to share a small yield from year to year due to natural factors or a large harvest in the rainy season, but the road is damaged, so it cannot be reached, and the fruit rots. |

| 9 | Public Relation PT. DJL | a. There is no core garden yet b. The soil is not fertile, so production is low |

| 10 | Head of North Konawe Horticulture and Horticulture Department |

The need for consistency on both sides (businesses and farmers) related to the MOU that was agreed upon. The Company must transparently convey related costs, namely a) investment costs, b) general costs, and c) operational costs. Optimizing the role of agricultural extension |

| 11 | Executive Director of WALHI Sultra | The flood was caused by the impact of plantations and mining. The good Company will follow the process by the existing provisions and rules. There is injustice and a lack of transparency in the Company . d. In developed countries, farmers are respected. We are here; being a farm labourer has no honour. Entrepreneurs use the centralized autonomy of this region to invest in stakeholders and those stakeholders to exploit the region. |

| 12 | Lepmil) /NGO |

If the regulations are not changed, the community’s well-being will remain unchanged. Why did mines dare to change the regulations? Why didn’t oil palm plantations issue a revision of the law so that they could no longer send CPOs abroad? Why don’t we make the industry in Indonesia? Should Southeast Sulawesi farmers send to their own industry, or should they send to India or Malaysia? We are laborer’s forever. There is no government control over fertilizers and prices. No government controls the community and always loses in negotiations. The principle is that if the old paradigm is still used and the method used is still a dream, it will not be achieved |

| 13 | North Konawe DPRD Member) |

In the House of Representatives, the people are devising regional regulations regarding recognizing territories elsewhere. If in Konawe Utara’s “Customary rights to land,” it is true that he is almost marginalized in North Konawe as a whole because his land is handed over to companies whose contracts will dominate for 30 years. So, this society needs to be in a stronger position. Companies that invest in North Konawe to be cooperative with the regional government |

| 14 |

North Konawe DPRD Member |

There is a need for proper socialization because Malaysia can develop its country with oil palm, so why not us? We must encourage the birth of a regional regulation, especially in North Konawe. There is no clear legal basis that provides protection to oil palm companies and farmers so that they both benefit equally. I have had many discussions with farmers. They desire to plant oil palm, but they are thinking about where our oil palm products will be marketed. d. Farmer institutions at the level of BUMDES have become a media source of information and capacity building for farmers. |

| 15 | Academic from North Konawe | The benefits of palm oil for the community include: The openness of the community’s vision and mindset so that many sons and daughters are sent out of the district for school, It used to be a remote region (difficult access). Now the access is better, Dormant land (unproductive) becomes cultivated/open, and The community obtains a permanent job (as an employee) who previously cultivates the fields (suitable for cash crops and long-term crops) and searches for rattan (locally called pa ratan) and hunts jong (deer).” Farmers’ Farmers’ institutions are needed to increase farmers’ capacity. |

3.3. Local Wisdom Practices

3.3. Social Capital in the Sustainability Dimension of Palm Oil Plantations

| Variables | Social Capital Indicator | Information Related to Sustainability Dimensions of Palm Oil Management Partnership Models | Information Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Social Capital |

Economic | ||

| Trust | Transparency of palm oil TBS prices Management of oil palm land Palm oil production |

Farmers (land owners) Company |

|

| Social Networks and Participation | Productivity of plasma/community oil palm plantations Farmer participation in cooperatives Influence of external information on palm oil TBS |

Farmers (land owners) Company |

|

| Local Wisdom |

Employment recruitment Community and government cooperation Involvement of community leaders |

Farmers (land owners) Company Local government |

|

| Social Solidarity | Determination of profit-sharing Maintain good communication with the Company Support company programs Help fellow farmers |

Farmers (land owners) Company |

|

| Reciprocity | Job opportunities TBS payments on time Farmer's income level |

Farmers (land owners) Company |

|

| Ecology | |||

| Trust | River water quality management CSR environmental care program The Company continues to maintain the fertility of the land |

Local Government Farmers (land owners) |

|

|

Social Networks and Farmer Participation |

There is involvement of environmental NGOs Farmer participation in environmentally friendly farming. Cooperation between farmers is lacking in the management of pam Oil; |

NGOs Local government Farmers (land owners) |

|

| Local Wisdom | Soil fertility treatment Proportion of forest area to plantation land Has a tradition of maintaining plantation and food crops, animal husbandry, and fisheries. |

Farmers (land owners) Local government |

|

| Social Solidarity |

Help preserve river borders Help each other in dealing with flood disasters Support company environmental programs • |

Department of Agriculture Farmer Academic |

|

| Mutual Benefits |

Reduced negative environmental impacts Public health and environmental sustainability |

NGOs Local government Academic |

|

| Social | |||

| Trust | Institutional management of farmers Land ownership status Company leadership |

Farmers (land owners) Company |

|

| Social Networks and Participation |

Farmer education level Participation of agricultural extension workers Participation in farming management • Farmers (land owners). |

Farmers (land owners) | |

| Local Wisdom | Livelihood Farmer cooperation |

Farmers (land owners) | |

| Social Solidarity |

Protection of farmers and environmental issues Attention of government agencies Implementation of CSR |

Farmers (land owners) government |

|

| Reciprocal | Availability of labour Assistance with public facilities Social assistance |

Farmers (land owners) Company Local government |

3.4. Role of Social Capital in the Sustainability of the Palm Oil Business Partnerships

3.4.1. Role of Trust

3.4.2. Role of Social Networks and Participation

3.4.2. Role of Reciprocal Social Capital

3.4.4. Role of Social Solidarity

3.5. Role of Local Wisdom in the Sustainability of Palm Oil Plantation Business Partnerships

3.6. Efforts to Sustain Business Partnerships through Social Capital

4. Conclusions

References

- Saswattecha, K.; Kroeze, C.; Jawjit, W.; Hein, L. Assessing the Environmental Impact of Palm Oil Produced in Thailand. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 100, 150–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silalertruksa, T.; Gheewala, S.H.; Pongpat, P.; Kaenchan, P.; Permpool, N.; Lecksiwilai, N.; Mungkung, R. Environmental Sustainability of Oil Palm Cultivation in Different Regions of Thailand: Greenhouse Gases and Water Use Impact. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 167, 1009–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limaho, H.; Sugiarto; Pramono, R. ; Christiawan, R. The Need for Global Green Marketing for the Palm Oil Industry in Indonesia. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayompe, L.M.; Schaafsma, M.; Egoh, B.N. Towards Sustainable Palm Oil Production: The Positive and Negative Impacts on Ecosystem Services and Human Wellbeing. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 278, 123914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syahza, A.; Irianti, M. Formulation of Control Strategy on the Environmental Impact Potential as a Result of the Development of Palm Oil Plantation. J. Sci. Technol. Policy Manag. 2021, 12, 106–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesmin, T.; Miaro III, L.; Mboringong, F.; Etoga, G.; Voundi, E.; Ngom, E.P.J. Environmental Impacts of the Oil Palm Cultivation in Cameroon. In Elaeis guineensis; IntechOpen, 2021 ISBN 183962762X.

- Ward, C.; Stringer, L.C.; Warren-Thomas, E.; Agus, F.; Crowson, M.; Hamer, K.; Hariyadi, B.; Kartika, W.D.; Lucey, J.; McClean, C. Smallholder Perceptions of Land Restoration Activities: Rewetting Tropical Peatland Oil Palm Areas in Sumatra, Indonesia. Reg. Environ. Chang. 2021, 21, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, X.; Xing, Y.; Wang, J.; Yang, H.; Gong, W. Effects of Land Use and Cover Change (LUCC) on Terrestrial Carbon Stocks in China between 2000 and 2018. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 182, 106333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotowska, M.M.; Leuschner, C.; Triadiati, T.; Meriem, S.; Hertel, D. Quantifying Above-and Belowground Biomass Carbon Loss with Forest Conversion in Tropical Lowlands of S Umatra (I Ndonesia). Glob. Chang. Biol. 2015, 21, 3620–3634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koh, L.P.; Wilcove, D.S. Is Oil Palm Agriculture Really Destroying Tropical Biodiversity? Conserv. Lett. 2008, 1, 60–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comte, I.; Colin, F.; Whalen, J.K.; Grünberger, O.; Caliman, J.-P. Agricultural Practices in Oil Palm Plantations and Their Impact on Hydrological Changes, Nutrient Fluxes and Water Quality in Indonesia: A Review. Adv. Agron. 2012, 116, 71–124. [Google Scholar]

- Ganser, D.; Denmead, L.H.; Clough, Y.; Buchori, D.; Tscharntke, T. Local and Landscape Drivers of Arthropod Diversity and Decomposition Processes in Oil Palm Leaf Axils. Agric. For. Entomol. 2017, 19, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, S. The Beetle or the Bug? Multispecies Politics in a West Papuan Oil Palm Plantation. Am. Anthropol. 2021, 123, 476–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dompreh, E.B.; Asare, R.; Gasparatos, A. Stakeholder Perceptions about the Drivers, Impacts and Barriers of Certification in the Ghanaian Cocoa and Oil Palm Sectors. Sustain. Sci. 2021, 16, 2101–2122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syahza, A.; Asmit, B. Regional Economic Empowerment through Oil Palm Economic Institutional Development. Manag. Environ. Qual. An Int. J. 2019, 30, 1256–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cancino, N.; Rubiños, C.; Vargas, S. Social Capital and Soil Conservation: Is There a Connection? Evidence from Peruvian Cocoa Farms. J. Rural Stud. 2022, 94, 462–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koomson, F.; Enu-Kwesi, F. Social Capital: The Missing Link in Ghana’s Development: Social Capital: The Missing Link in Ghana’s Development. Oguaa J. Soc. Sci. 2020, 9, 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Himanshu, H.; Arokiasamy, P.; Talukdar, B. Illustrative Effects of Social Capital on Health and Quality of Life among Older Adult in India: Results from WHO-SAGE India. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2019, 82, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Putnam, R.D. Making Democracy Work: Civic Traditions in Modern Italy. 1994.

- Jia, X.; Chowdhury, M.; Prayag, G.; Chowdhury, M.M.H. The Role of Social Capital on Proactive and Reactive Resilience of Organizations Post-Disaster. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2020, 48, 101614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Omoush, K.S.; Simón-Moya, V.; Sendra-García, J. The Impact of Social Capital and Collaborative Knowledge Creation on E-Business Proactiveness and Organizational Agility in Responding to the COVID-19 Crisis. J. Innov. Knowl. 2020, 5, 279–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C. Social Capital and COVID-19: A Multidimensional and Multilevel Approach. Chin. Sociol. Rev. 2021, 53, 27–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saptutyningsih, E.; Diswandi, D.; Jaung, W. Does Social Capital Matter in Climate Change Adaptation? A Lesson from Agricultural Sector in Yogyakarta, Indonesia. Land use policy 2020, 95, 104189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jundiani, J. Globalisasi: Tantangan Dalam Penyediaan Ruang Terbuka Hijau Dan Konservasi Sumber Daya Air. Bina Huk. Lingkung. 2018, 3, 127–136. [Google Scholar]

- Rahmah, M.; Sulistyono, A. The Integration of Traditional Knowledge and Local Wisdom in Mitigating and Adapting Climate Change: Different Perspectives of Indigenous Peoples from Java and Bali Island. In Traditional Knowledge and Climate Change: An Environmental Impact on Landscape and Communities; Springer, 2024; pp. 61–80.

- Hatu, D.R.R.; Wisadhirana, D.; Susilo, E. The Role of Local Wisdom as Social Capital of Remote Indigenous Communities (RIC). Politico 2019, 19, 67–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossmann, I. Wisdom in Context. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2017, 12, 233–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kohsaka, R.; Rogel, M. Traditional and Local Knowledge for Sustainable Development: Empowering the Indigenous and Local Communities of the World. In Partnerships for the Goals; Springer, 2021; pp. 1261–1273.

- Halstead, J.M.; Deller, S.C.; Leyden, K.M. Social Capital and Community Development: Where Do We Go from Here? Community Dev. 2022, 53, 92–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogahara, Z.; Jespersen, K.; Theilade, I.; Nielsen, M.R. Review of Smallholder Palm Oil Sustainability Reveals Limited Positive Impacts and Identifies Key Implementation and Knowledge Gaps. Land use policy 2022, 120, 106258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, K. The Role of Social Capital in Improving the Welfare of Rice Farmers in Tangerang Banten Regency. Budapest Int. Res. Critics Institute-Journal 2022, 5, 29648–29657. [Google Scholar]

- Rocca, L.H.D.; Zielinski, S. Community-Based Tourism, Social Capital, and Governance of Post-Conflict Rural Tourism Destinations: The Case of Minca, Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta, Colombia. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2022, 43, 100985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, B.; Fielke, S.; Bayne, K.; Klerkx, L.; Nettle, R. Navigating Shades of Social Capital and Trust to Leverage Opportunities for Rural Innovation. J. Rural Stud. 2019, 68, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saz-Gil, I.; Bretos, I.; Díaz-Foncea, M. Cooperatives and Social Capital: A Narrative Literature Review and Directions for Future Research. Sustainability 2021, 13, 534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hrytsaienko, M.; Hrytsaienko, H.; Andrieieva, L.; Boltianska, L. The Role of Social Capital in Development of Agricultural Entrepreneurship. In Modern Development Paths of Agricultural Production: Trends and Innovations; Springer, 2019; pp. 427–440.

- Alghababsheh, M.; Gallear, D. Socially Sustainable Supply Chain Management and Suppliers’ Social Performance: The Role of Social Capital. J. Bus. Ethics 2021, 173, 855–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibli, R.; Saifan, S.; Ab Yajid, M.S.; Khatibi, A.; Azam, S.M.F. Social Capital, Agriculture Extension Services and Access of Resources toward Innovation Adoption in Household Farming in Malaysia. AgBioForum 2021, 23, 102–112. [Google Scholar]

- Grabs, J.; Garrett, R.D. Goal-Based Private Sustainability Governance and Its Paradoxes in the Indonesian Palm Oil Sector. J. Bus. Ethics 2023, 188, 467–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, K.Y.N. Effects of Organizational Culture, Affective Commitment and Trust on Knowledge-Sharing Tendency. J. Knowl. Manag. 2022, 27, 1140–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paterson, R.R.M.; Lima, N. Climate Change Affecting Oil Palm Agronomy, and Oil Palm Cultivation Increasing Climate Change, Require Amelioration. Ecol. Evol. 2018, 8, 452–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merten, J.; Röll, A.; Guillaume, T.; Meijide, A.; Tarigan, S.; Agusta, H.; Dislich, C.; Dittrich, C.; Faust, H.; Gunawan, D. Water Scarcity and Oil Palm Expansion: Social Views and Environmental Processes. Ecol. Soc. 2016, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santika, T.; Wilson, K.A.; Meijaard, E.; Budiharta, S.; Law, E.E.; Sabri, M.; Struebig, M.; Ancrenaz, M.; Poh, T.-M. Changing Landscapes, Livelihoods and Village Welfare in the Context of Oil Palm Development. Land use policy 2019, 87, 104073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatto, M.C.; Zerboni, A. Holocene Supra-Regional Environmental Changes as Trigger for Major Socio-Cultural Processes in Northeastern Africa and the Sahara. African Archaeol. Rev. 2015, 32, 301–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suparnyo Cooperatives in the Indonesian Constitution and the Role in Empowering Members: A Case Study. J. Leg. Ethical Regul. Isses 2019, 22, 1.

- Butarbutar, D.D.; Wijaya, M.M. Cooperative And Msme Empowerment Strategies in Economic Recovery During The Covid-19 Pandemic in Bogor Regency Indonesia. 2021.

- Hunecke, C.; Engler, A.; Jara-Rojas, R.; Poortvliet, P.M. Understanding the Role of Social Capital in Adoption Decisions: An Application to Irrigation Technology. Agric. Syst. 2017, 153, 221–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karim, A.; Musa, C.I.; Romansyah Sahabuddin, M.A. Regional Economic Growth the Role of BUMDes Institutions in Enrekang Regency. Int. J. Creat. Res. Thoughts 2020, 8, 225–229. [Google Scholar]

- Sufi, W.; Saputra, T. Implementation of Village Empower Program in Supporting Form of Institutions of Village Business Institutions (BUMDes)(Study on Dayang Suri Village Bungaraya Sub District Siak Regency Riau Province). J. Perspekt. Pembiayaan dan Pembang. Drh. 2017, 5, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toyon, M.A.S. The Three’R’s of Social Capital: A Retrospective. FWU J. Soc. Sci. 2022, 16, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, T.M. We Have to Leverage Those Relationships: How Black Women Business Owners Respond to Limited Social Capital. Sociol. Spectr. 2021, 41, 137–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gannon, B.; Roberts, J. Social Capital: Exploring the Theory and Empirical Divide. Empir. Econ. 2020, 58, 899–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calcagnini, G.; Perugini, F. Social Capital and Well-Being in the Italian Provinces. Socioecon. Plann. Sci. 2019, 68, 100668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Leidner, D.E.; Benbya, H.; Zou, W. Social Capital and Knowledge Contribution in Online User Communities: One-Way or Two-Way Relationship? Decis. Support Syst. 2019, 127, 113131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chetty, R.; Jackson, M.O.; Kuchler, T.; Stroebel, J.; Hendren, N.; Fluegge, R.B.; Gong, S.; Gonzalez, F.; Grondin, A.; Jacob, M. Social Capital I: Measurement and Associations with Economic Mobility. Nature 2022, 608, 108–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, C.A.; Men, L.R.; Ferguson, M.A. Bridging Transformational Leadership, Transparent Communication, and Employee Openness to Change: The Mediating Role of Trust. Public Relat. Rev. 2019, 45, 101779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akkaya, B.; Bagieńska, A. The Role of Agile Women Leadership in Achieving Team Effectiveness through Interpersonal Trust for Business Agility. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, J.; Bidwell, D. Chains of Trust: Energy Justice, Public Engagement, and the First Offshore Wind Farm in the United States. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2019, 47, 166–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolot, A.; Kozmenko, S.; Herasymenko, O.; Štreimikienė, D. Development of a Decent Work Institute as a Social Quality Imperative: Lessons for Ukraine. Econ. Sociol. 2020, 13, 70–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besley, T.; Dray, S. Trust as State Capacity: The Political Economy of Compliance; WIDER Working Paper, 2022; ISBN 9292672681.

- Manoj, M.; Brough, R.; Kalbarczyk, A. Exploring the Role and Nature of Trust in Institutional Capacity Building in Low-and Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review. 2020.

- Scherp, A.; Schwagereit, F.; Ireson, N.; Lanfranchi, V.; Papadopoulos, S.; Kritikos, A.; Kopatsiaris, Y.; Smrs, P. Leveraging Web 2.0 Communities in Professional Organisations. In Proceedings of the W3C workshop on the future of social networking; 2009.

- Thilagam, P.S. Applications of Social Network Analysis. Handb. Soc. Netw. Technol. Appl. 2010, 637–649. [Google Scholar]

- Olavarria-Gambi, M. Poverty and Social Programs in Chile. J. Poverty 2009, 13, 99–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carchiolo, V.; Longheu, A.; Malgeri, M.; Mangioni, G.; Nicosia, V. An Approach to Trust Based on Social Networks. In Proceedings of the Web Information Systems Engineering–WISE 2007: 8th International Conference on Web Information Systems Engineering Nancy, France, 2007 Proceedings 8; Springer, 2007, December 3-7; pp. 50–61.

- Paletto, A.; Hamunen, K.; De Meo, I. Social Network Analysis to Support Stakeholder Analysis in Participatory Forest Planning. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2015, 28, 1108–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, H.T.P.; McMurray, J.R.; Kurz, T.; Lambert, F.H. Network Analysis Reveals Open Forums and Echo Chambers in Social Media Discussions of Climate Change. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2015, 32, 126–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felmlee, D.; Faris, R. Interaction in Social Networks. In Handbook of social psychology; Springer, 2013; pp. 439–464.

- Frank, K.A.; Penuel, W.R.; Krause, A. What Is a “Good” Social Network for Policy Implementation? The Flow of Know-how for Organizational Change. J. Policy Anal. Manag. 2015, 34, 378–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cramton, P.; Doyle, L. Open Access Wireless Markets. Telecomm. Policy 2017, 41, 379–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soria, K.M. Welcoming Blue-Collar Scholars into the Ivory Tower: Developing Class-Conscious Strategies for Student Success. Series on Special Student Populations.; ERIC, 2015; ISBN 1889271969.

- Ruggeri, A.; Samoggia, A. Twitter Communication of Agri-food Chain Actors on Palm Oil Environmental, Socio-economic, and Health Sustainability. J. Consum. Behav. 2018, 17, 75–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Li, M.; Wang, Z.; Lin, Y. Transformational Leadership and Employees’ Reactions to Organizational Change: Evidence from a Meta-Analysis. J. Appl. Behav. Sci. 2021, 57, 369–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizal, A.R.A.; Nordin, S.M. Smallholders Participation in Sustainable Certification: The Mediating Impact of Deliberative Communication and Responsible Leadership. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 978993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vamuloh, V.V.; Kozak, R.A.; Panwar, R. Voices Unheard: Barriers to and Opportunities for Small Farmers’ Participation in Oil Palm Contract Farming. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 275, 121955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasaribu, S.I.; Vanclay, F.; Zhao, Y. Challenges to Implementing Socially-Sustainable Community Development in Oil Palm and Forestry Operations in Indonesia. Land 2020, 9, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balwin, T.; Ford, J.K. Transfer of Training: A Review and Directions for Future Research. Personal Psychology, 41 (1), 63-105 1988.

- Doktorova, D.S. Theoretical Review of Manifestations and Features of Social Solidarity. Наукoвo-теoретичний альманах Грані 2018, 21, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardhani, R.; Rahadian, Y. Sustainability Strategy of Indonesian and Malaysian Palm Oil Industry: A Qualitative Analysis. Sustain. Accounting, Manag. Policy J. 2021, 12, 1077–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewi, G.D.P. Multi-Stakeholder Engagement in the Indonesian Sustainable Palm Oil (ISPO) Framework. In Proceedings of the IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science; IOP Publishing, 2021; Vol. 729; p. 12085. [Google Scholar]

- Imbiri, S.; Rameezdeen, R.; Chileshe, N.; Statsenko, L. Stakeholder Perspectives on Supply Chain Risks: The Case of Indonesian Palm Oil Industry in West Papua. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Septiyarini, D.; Kusrini, N.; Kurniati, D. Sustainability of Palm Oil Company CSR in Supporting Village Status Change. Econ. Dev. Anal. J. 2022, 11, 165–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christiawan, R.; Limaho, H. The Importance of Co-Opetition of Corporate Social Responsibility in the Palm Oil Industry in Indonesia. Corp. Trade Law Rev. 2020, 1, 68–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snashall, G.B.; Poulos, H.M. ‘Smallholding for Whom?’: The Effect of Human Capital Appropriation on Smallholder Palm Farmers. Agric. Human Values 2023, 40, 1599–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahliani, D. Local Wisdom Inbuilt Environment in Globalization Era. Local Wisdom Inbuilt Environ. Era 2010, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Obie, M.; Pakaya, M. Oil Palm Expansion And Livelihood Vulnerability On Rural Communities (A Case In Pohuwato Regency-Indonesia). Humanit. Soc. Sci. Rev. 2020, 8, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Schoneveld, G.C.; Van Der Haar, S.; Ekowati, D.; Andrianto, A.; Komarudin, H.; Okarda, B.; Jelsma, I.; Pacheco, P. Certification, Good Agricultural Practice and Smallholder Heterogeneity: Differentiated Pathways for Resolving Compliance Gaps in the Indonesian Oil Palm Sector. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2019, 57, 101933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, J.F.; Gillespie, P.; Zen, Z. Swimming Upstream: Local Indonesian Production Networks in “Globalized” Palm Oil Production. World Dev. 2012, 40, 555–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syahza, A. The Potential of Environmental Impact as a Result of the Development of Palm Oil Plantation. Manag. Environ. Qual. An Int. J. 2019, 30, 1072–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yunus, S.; Jalil, F. Government Policy in Strengthening Social Capital for Poverty Reduction of Farmers. J. Posit. Psychol. Wellbeing 2021, 5, 1011–1025. [Google Scholar]

- Cofré-Bravo, G.; Klerkx, L.; Engler, A. Combinations of Bonding, Bridging, and Linking Social Capital for Farm Innovation: How Farmers Configure Different Support Networks. J. Rural Stud. 2019, 69, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, S.; Rieple, A.; Chang, J.; Boniface, B.; Ahmed, A. Small Farmers and Sustainability: Institutional Barriers to Investment and Innovation in the Malaysian Palm Oil Industry in Sabah. J. Rural Stud. 2015, 40, 46–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nupueng, S.; Oosterveer, P.; Mol, A.P.J. Governing Sustainability in the Thai Palm Oil-Supply Chain: The Role of Private Actors. Sustain. Sci. Pract. Policy 2022, 18, 37–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awan, U.; Kraslawski, A.; Huiskonen, J. Governing Interfirm Relationships for Social Sustainability: The Relationship between Governance Mechanisms, Sustainable Collaboration, and Cultural Intelligence. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, M.E.; Duff, H.; Kelly, S.; McHugh Power, J.E.; Brennan, S.; Lawlor, B.A.; Loughrey, D.G. The Impact of Social Activities, Social Networks, Social Support and Social Relationships on the Cognitive Functioning of Healthy Older Adults: A Systematic Review. Syst. Rev. 2017, 6, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayrakdar, S.; Yucedag, I.; Simsek, M.; Dogru, I.A. Semantic Analysis on Social Networks: A Survey. Int. J. Commun. Syst. 2020, 33, e4424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallor, S. Social Networking Technology and the Virtues. In The ethics of information technologies; Routledge, 2020; pp. 447–460.

- Araújo, L.; Teixeira, L.; Ribeiro, O.; Paul, C. Social Participation, Occupational Activities and Quality of Life in Older Europeans: A Focus on the Oldest Old. Handb. Act. ageing Qual. life From concepts to Appl. 2021, 537–547. [Google Scholar]

- Jalil, A.; Yesi, Y.; Sugiyanto, S.; Puspitaloka, D.; Purnomo, H. The Role of Social Capital of Riau Women Farmer Groups in Building Collective Action for Tropical Peatland Restoration. For. Soc. 2021, 5, 341–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skaalsveen, K.; Ingram, J.; Urquhart, J. The Role of Farmers’ Social Networks in the Implementation of No-till Farming Practices. Agric. Syst. 2020, 181, 102824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhuri, S.; Roy, M.; McDonald, L.M.; Emendack, Y. Reflections on Farmers’ Social Networks: A Means for Sustainable Agricultural Development? Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2021, 23, 2973–3008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuliani, E.L.; De Groot, W.T.; Knippenberg, L.; Bakara, D.O. Forest or Oil Palm Plantation? Interpretation of Local Responses to the Oil Palm Promises in Kalimantan, Indonesia. Land use policy 2020, 96, 104616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Futemma, C.; De Castro, F.; Brondizio, E.S. Farmers and Social Innovations in Rural Development: Collaborative Arrangements in Eastern Brazilian Amazon. Land use policy 2020, 99, 104999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charatsari, C.; Lioutas, E.D.; Koutsouris, A. Farmer Field Schools and the Co-Creation of Knowledge and Innovation: The Mediating Role of Social Capital. In Social innovation and sustainability transition; Springer, 2022; pp. 205–220.

- Nawipa, S.; Ramandei, L. The Impact of the Existence of Palm Oil Company (PT. Sinar Mas) on the Community Social Welfare in Mansaburi Village Masni District Manokwari Regency West Papua Province. Int J Arts Huma Soc. Stud. 2022, 4, 9–16. [Google Scholar]

- Apresian, S.R.; Tyson, A.; Varkkey, H.; Choiruzzad, S.A.B.; Indraswari, R. Palm Oil Development in Riau, Indonesia: Balancing Economic Growth and Environmental Protection. Nusantara 2020, 2, 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, G.; Pulignano, V. Solidarity at Work: Concepts, Levels and Challenges. Work. Employ. Soc. 2020, 34, 18–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pye, O. Commodifying Sustainability: Development, Nature and Politics in the Palm Oil Industry. World Dev. 2019, 121, 218–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandro, R.; Haridison, A.; Thomas, O.; Simpun, S.; Hariatama, F. Dissociative Social Interaction of Plasma Farmers and Palm Oil Companies in East Kotawaringin. J. Ilmu Sos. dan Hum. 2023, 12, 474–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamal, M.A.; Utomo, M.R.; Hakim, M.L.; Qurbani, I.D.; Ikram, A.D. Peatland Management Based on Local Wisdom Through Rural Governance Improvement and Agroindustry. Int. J. Environ. Sustain. Soc. Sci. 2023, 4, 774–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astuti, R.; McGregor, A. Indigenous Land Claims or Green Grabs? Inclusions and Exclusions within Forest Carbon Politics in Indonesia. J. Peasant Stud. 2017, 44, 445–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandi, C.; Cabani, T.; Hosang, C.; Schirmbeck, S.; Westermann, L.; Wiese, H. Sustainability Standards for Palm Oil: Challenges for Smallholder Certification under the RSPO. J. Environ. Dev. 2015, 24, 292–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, K.M.; Heilmayr, R.; Gibbs, H.K.; Noojipady, P.; Burns, D.N.; Morton, D.C.; Walker, N.F.; Paoli, G.D.; Kremen, C. Effect of Oil Palm Sustainability Certification on Deforestation and Fire in Indonesia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2018, 115, 121–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No | Stakeholders/Informants | Number of Informants (people/respondents | Data Collection |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Company | PTPN-14 | 2 | Interview, FGD |

| PT.DJL | 2 | Interview, FGD | ||

| PT. SPL, | 2 | Interview, FGD | ||

| 2 | Government | North Konawe People's Representative Council | Interview, FGD | |

| Head of the North Konawe Plantation and Horticulture Service | 1 | Interview, FGD | ||

| Village Heads | 11 | Interview, FGD | ||

| 3 | Academics | Higher Education | 2 | FGD |

| 4 | Community (land owners) | Land owner representatives | 5 | Interview, FGD |

| 5 | NGO | LEPMIL | 1 | FGD |

| 6 | Media/NGO | Executive director WALHI Sultra | 1 | FGD |

| 7 | Communities Surrounding Oil Palm | Palm Farmers (owners, managers and workers) | 321 | Survey |

| Company Name | Initial Year of Operation |

Location | Area (Ha) | Production (Ton) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | ||||

| PT. Sultra Prima Lestari (factory available) | 2006 | Andowia, Asera, Langgikima, Oheo | 6.900 | 32.000 | 41.000 | 47.000 |

| PT. Damai Jaya Lestari (factory available) | 2006 | Landawe, Wiwirano | 6.989 | 28.000 | 42.000 | 48.000 |

| PT. Perkebunan Nusantara XIV (no factory) | 1994 | Wawontoaho, Wiwirano, | 6.500 | 51.870 | 84.435 | 87.425 |

| Terms of Agreement between Company and Farmer/Land Owner | ||

|---|---|---|

| PT.SPL | PT.DJL | PTPN XIV |

| The land owner hands over the land/soil and the growing plants without compensating the company. During the term of this agreement, the company will manage the entire land area handed over entirely. |

PTPN XIV has a nucleus and plasma plantations on farmers' land with a credit system. |

|

| For farmers/land owners who lend land to the company, 60% (sixty per cent) is used for the company's interests, and 40% (forty per cent) is returned to the land owner in the form of oil palm plantation products during one oil palm production cycle (+/- 30 years). | Farmers who own land lend land to the company, the land owner gets a profit share of 80 percent for the company and the land owner 20 percent. |

Providing capital assistance to plasma farmers, which is returned in the form of business credit, |

| ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).