Introduction

Suicide is a public health problem.[

1] According to the World Health Organization, 800,000 people committed suicide in 2015.[

2] In Brazil, in the same year, there were 10,000 suicides, being much lower (5/100,000 inhabitants) compared to European countries (20/100,000 inhabitants approximately).[

3,

4] The Brazilian cities that were described with the highest risk of suicide in this same period were Taipas do Tocantins, in the State of Tocantins (79.68/100,000 inhabitants), Itaporã in the State of Mato Grosso (75.15/100,000 inhabitants), Mampituba in the State of Rio Grande do Sul (52.98/100,000 inhabitants), Paranhos in the State of Mato Grosso do Sul (52.41/100,000 inhabitants) and Monjolos in the State of Minas Gerais (52.08/100,000). The high rates of suicides in these cities with indigenous communities are noteworthy.

Mortality rates in the world in general have been decreasing and the World Health Organization estimates that, in 2023, there would be 700,000 suicides. That is, 100,000 less in rates than approximately 20 years ago.[

5] However, Brazil is going against this trend and has been showing an increase in suicide rates. According to the National Epidemiological Bulletin 2019, suicide mortality has increased by 30.08% in 10 years (from 9,454 in 2010 to 13,523 in 2019), reaching 6.65/100,000 people. The southern and central-western regions are the most affected, with the states of Rio Grande do Sul and Santa Catarina exceeding the suicide mortality rate of 11/100,000 people.[

6]

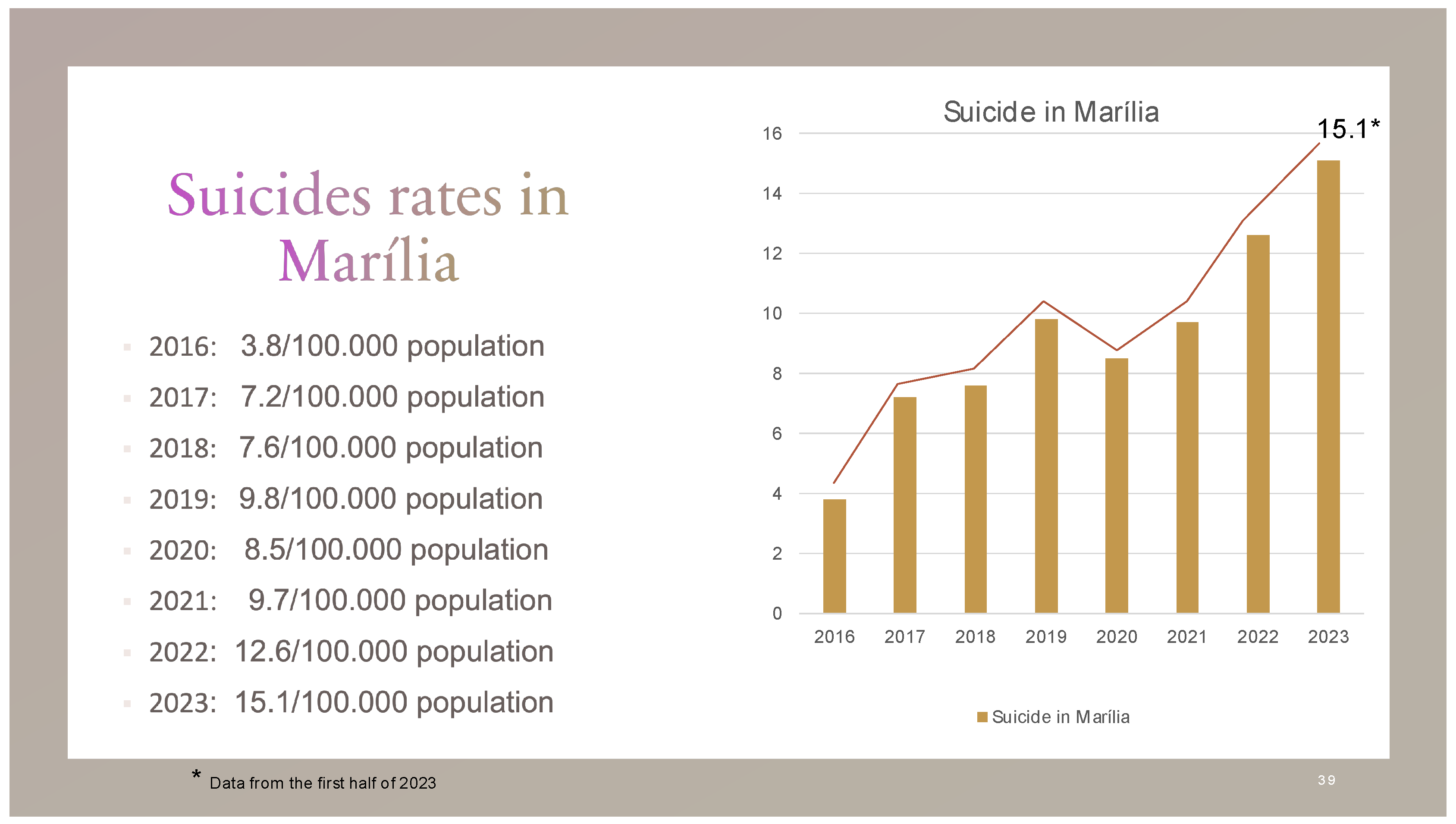

The mental health coordination of the municipality of Marília, in the state of São Paulo, reported that in 2021 there were 23 deaths from suicide.[

7] We thus arrive at a suicide mortality rate of 9.5/100,000 in Marília. This number is almost double the average for the state of São Paulo and configures an epidemic context with an increase of 297.37% in incidence from 2016 to 2023. (

Figure 1) Marília is a city of approximately 250,000 inhabitants.[

8] It was in this community that we collected the data for our study.

There can be many strategies to reach an understanding of the factors associated with suicide.[

9] We chose to carry out an epidemiological study in seeking to associate lifelong events with suicidal symptoms.

The occurrence of suicide is just the tip of the iceberg of a vast topic in science, where to understand it becomes important to include prodromal events, which are suicidal ideation, suicidal planning, and suicide attempts.[

10] Suicide can be understood as a syndrome correlated with several illnesses, such as depression, personality disorders, drug use, etc.[

11] Therefore, the prodromal events of programming and planning the suicide attempt are part of the suicidal syndrome. So, if we want to study suicidal behavior in a society, all preliminary cognitive and affective events that may be related must be considered.

In a school survey among adolescents in Sergipe, the prevalence of suicidal ideation was 42.7%, of those who thought about killing themselves, the prevalence of suicidal planning was 67.8%, and of those who planned to kill themselves, a portion of 63.3% tried to kill themselves.[

12] One population prevalence study on suicidal ideation, suicidal planning, and suicide attempts to our knowledge in Brazil was carried out in Campinas in 2003.[

13] In this Survey, the prevalence of suicidal ideation was 17.1%, that of suicidal planning was 4.8% and that of suicide attempts was 2.8%.

There are still many gaps in the understanding of suicidal behavior.[

14] In this context of doubts, we spent 10 years without any population prevalence study of suicide in Brazil, where only data collection has been carried out on websites published by the government.[

15] In 2020, a prevalence study on suicidal ideation was published in a city of 210,000 inhabitants in southern Brazil. In this study, a suicidal ideation prevalence of 6.6% was observed, where depression, middle-aged and elderly adults, women, white people, single people, alcohol and drug users, and poverty were the biggest association factors. No measurements were made on suicide attempts.[

16] Have all our questions been answered?

Consequently, this present study aims to identify factors associated with suicidal ideation, suicidal planning, suicide attempts, and suicide.

Materials and methods

This study was designed as a survey. An informed consent form was developed. The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee (number 40205820.0.0000.5413).

A validated questionnaire was used:

Kaiser-

Meyer-

Olkin index (KMO) = .86 (acceptable greater than .7) and intraclass correlated coefficient (ICC) = .98 (acceptable greater than .9) The KMO assesses the adequacy of factor analysis and ICC checks reliability.[

17] The following were considered inclusion factors:

It was considered an exclusion factor:

In a study with some similarity carried out in Campinas in 2005, a minimum

η of 500 was considered for a sampling error of 2% and α of 5% with a prevalence of 2.7%.[

18,

19] It was proposed to calculate the sample with an indefinite prevalence of 50% for an infinite study (p=0.5 and q=0.5). Thus, if we consider a sampling error of 5% with a confidence level of 95%, we will have an

η of 385, which we can round to

400 because it is necessary to discard some responses.[

20]

Data collection from the general population was obtained by sampling for the convenience of the questionnaire, sent by virtual means, such as Facebook, Instagram (online questionnaire), and WhatsApp. Local newspapers, radio, and television stations helped disseminate the research throughout the city. Despite a selection bias, we opted for this collection method in times of pandemic. Participant contact will not be disclosed at any time during this study.

Each variable had its Prevalence Ratio (PR) calculated concerning suicidal ideation, suicidal planning, and suicide attempts.

Multivariate associations were measured using factor analysis.

National data reported an increase in the occurrence of suicide in Brazil from 2016 onwards. To verify the factors associated with the incidence of suicide in the city of Marília, we consulted the morbidity and mortality records data platform of the State of São Paulo (DataSUS) in the years 2016 to 2023. The data were described in tables to verify their distribution.

All analyses were carried out using SPSS version 29.

Results

640 responses were obtained after 15 days of releasing the online questionnaire link. Having exceeded the minimum of 400 responses for the calculated sample, data collection was finalized. From this total, 15 replicates were removed. It took a sample of 625 for analysis. Of these, 422 were women, 201 were men and two did not disclosure.

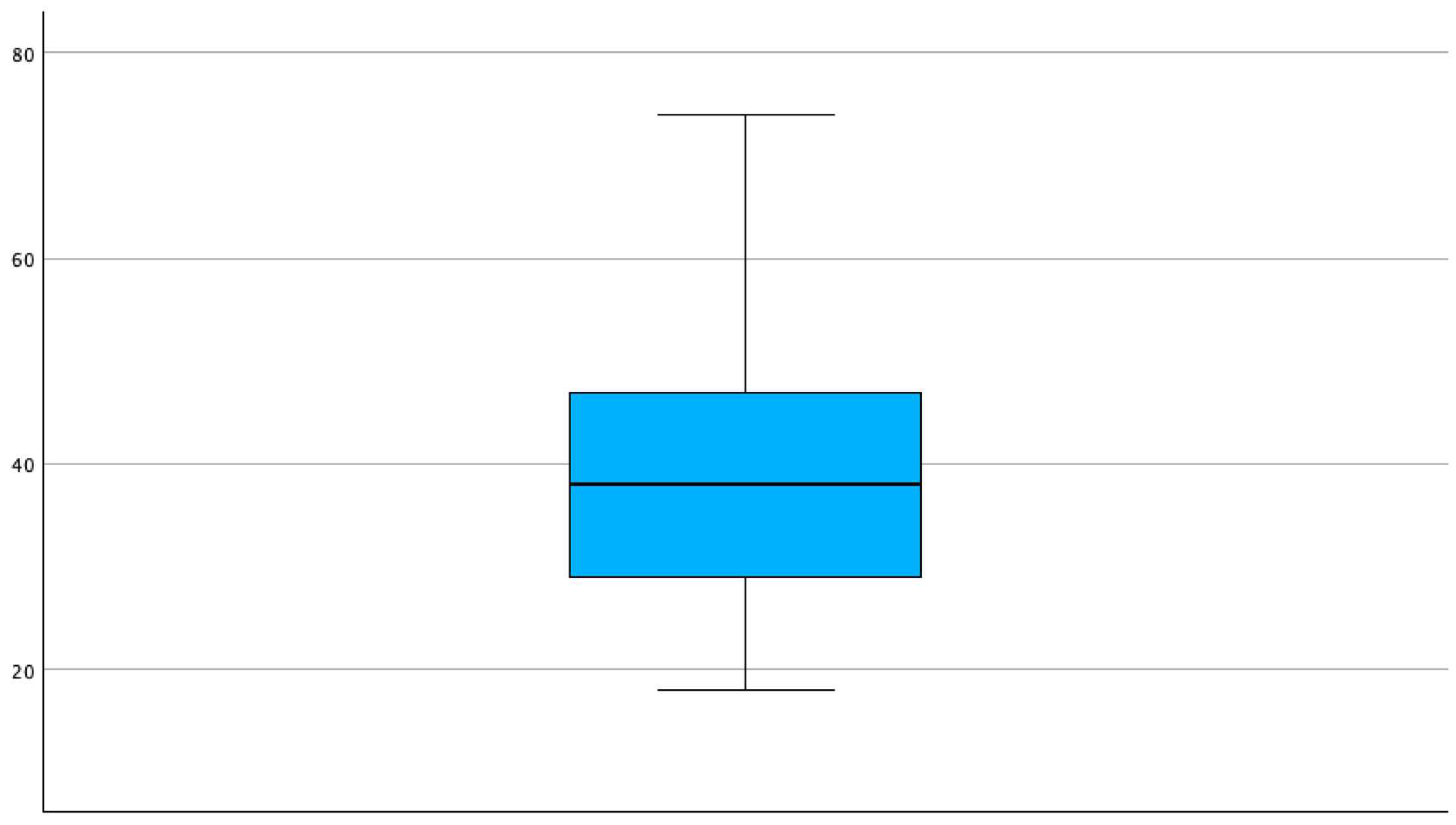

All reported prevalence refers to lifetime occurrences. The suicidal ideation prevalence was 50.1% and that of suicide attempts was 16.3%. Most respondents were middle-aged adults 39.30 (±12.70) years old. (Graphic 1) Half of the sample (52.1%) had gone through psychiatric treatment at some point. More than half had higher education (72.69%), 71.2% were working, 27.7% were in a difficult economic situation, 40.5% used alcohol and/or drugs, 9% showed some heroic behavior, 83.9% answered to be heterosexual, 54.9% had children, for 71.2% both parents are alive, 83.4% lived with their biological parents in childhood, 92.6% had biological siblings, 34.1% suffered some violence in childhood.47.7% are married, 93.9% have friends, 49.1% attended some socio-cultural group, 85.6% had some meaning in their lives, only 2.2 did not have symbolic beliefs, 76.7% believe in the immortality of the soul, and 67.7% had already talked about suicide with someone.

Graphic 1.

Age of participants at the survey. Mean: 39.30 (±12.70).

Graphic 1.

Age of participants at the survey. Mean: 39.30 (±12.70).

The prevalence ratio (PR) of suicidal thoughts was 1.58 for women compared to men. The PR of suicidal planning is 1.57 for women compared to men. The PR of suicide attempts is 1.89 for women compared to men. Those who replied not having meaning in life had a PR of 2.25 suicide attempts among those who did.

Not having friends was 2.12 more prevalent in individuals with attempted suicide (PR = 3.12). Not having beliefs in the immortality of the soul about suicidal ideation and suicide attempts had a PR of 1.22 and 1.04 respectively. A lower experience of symbolic beliefs presented a PR of 1.80 compared to a greater symbolic experience for suicide attempts.

For those who had already undergone some psychiatric treatment, there was a greater manifestation of suicidal symptoms, with a PR of 4.85 for suicidal ideation, 6.15 for suicidal planning, and 8.09 for a suicide attempt. Suicide attempts in Marília in the LGBTQIA+ community are more than twice as frequent than in heterosexuals, with PR of 2.45 for homosexuals, 2.95 for bisexuals, and 2.32 for others. Heroic behavior had a PR of 1.61 for attempted suicide. In this study, heroism was understood as a mixture of excessive altruistic and adventurous characteristics. For those who used alcohol and drugs, the PR for suicide attempts was 1.12. Among drug users only, the PR for suicide attempts was 2.97.

Being in economic stress had a PR of 4.69 for suicide attempts. Those unemployed had a PR of 3.28 in suicide attempt comparison to those who were working. The PR between those who did not have a higher education level and those who had a higher education level was 3.31 for suicide attempts. Having an incurable chronic disease demonstrated a PR of 1.60 for suicide attempts.

Not having children had a PR of 1.47 for suicidal ideation and 1.37 for suicide attempts. Having the parents alive had a PR of 1.41 for suicidal planning and 1.19 for suicide attempts. Not living with biological parents in childhood had a PR of 1.15 for suicide attempts. Not having biological siblings had a PR of 2.88 for suicide attempts. Those with siblings who attempted suicide had a PR of 1.37 for suicidal ideation and 1.21 for suicide attempts.

Those who experienced violence in childhood had a PR of 3.26 for attempted suicide. In this regard, being a victim of psychological and/or sexual violence were the most prevalent (>25%) in those who attempted suicide. Compared to married individuals, single patients had a PR of 2.02 for suicide attempts, in the same way, widows had a PR of 3.38 and those divorced of 1.35. Those who did not attend any social group had a PR of 2.68 for attempted suicide. Atheists had a PR of 1.75 for attempted suicide. A summary of the PRs is presented in

Table 1.

The elder population of Marília had a lower prevalence of suicide attempts (57 to 74 years old = 3.15%) compared to middle-aged (31 to 56 years old = 15.4%) and young adults (18 to 30 years old) = 20.9%). Therefore, the PR of older individuals is 0.204 than middle-aged individuals and 1.36 for younger individuals than middle-aged individuals.

The factor related to the possibility of committing suicide in the circumstance of experiencing a tragedy was called “Tragic Suicide”. The main associations of this construct were: having heroic behavior demonstrated a prevalence of 66.1% for committing tragic suicide versus 28.5% of those without heroic behavior with a PR of 2.1 (1.4-3.0); not having friends demonstrated a prevalence of 65.5% for tragic suicide versus 29.5% of those with friends, with a PR of 2.2 (1.7-2.9); not having children demonstrated a prevalence of 42.6% for committing tragic suicide versus 23% for those who have children with a PR of 1.8 (1.4-2.3); the prevalence of being able to commit tragic suicide in those who did not live with their biological parents in childhood was 47.1% versus 28.8% of those who lived with their biological parents with a PR of 1.6 (1.3-2.0)

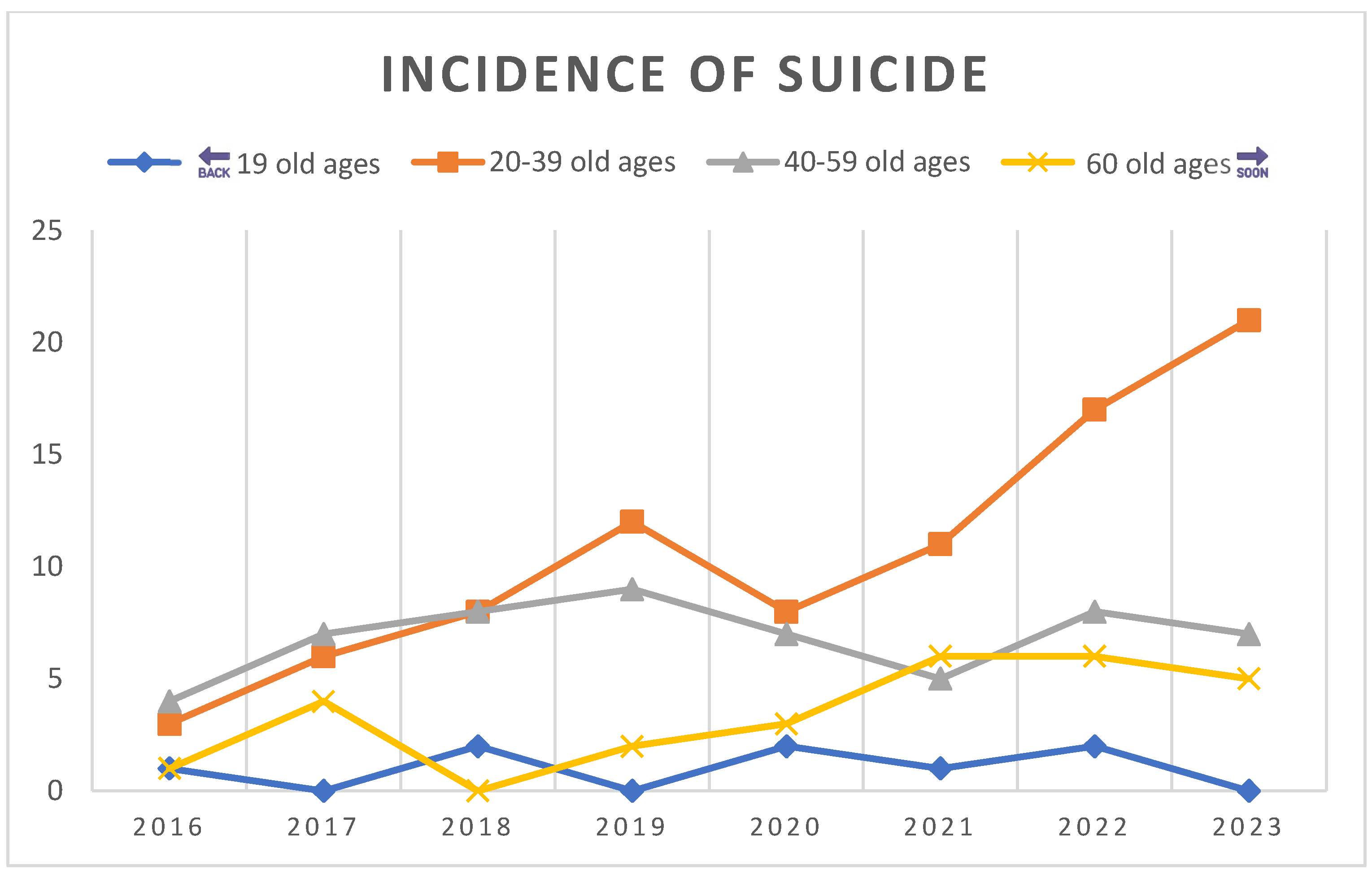

The incidence of suicides in Marília reveals a high rate of occurrence in young adults, with a 600% increase in the 20 to 39 age group. More than half (53.41%) of suicides occurred in people under 40 years of age. More than ¾ of suicides occurred in men (78.98%), 63.64% were informed as belonging to the white race, unmarried individuals were 42,04% and, 9.09% had 12 years or more of education. (

Table 2 and Graphic 2)

Graphic 2.

Incidence in absolute numbers by Age Classes.

Graphic 2.

Incidence in absolute numbers by Age Classes.

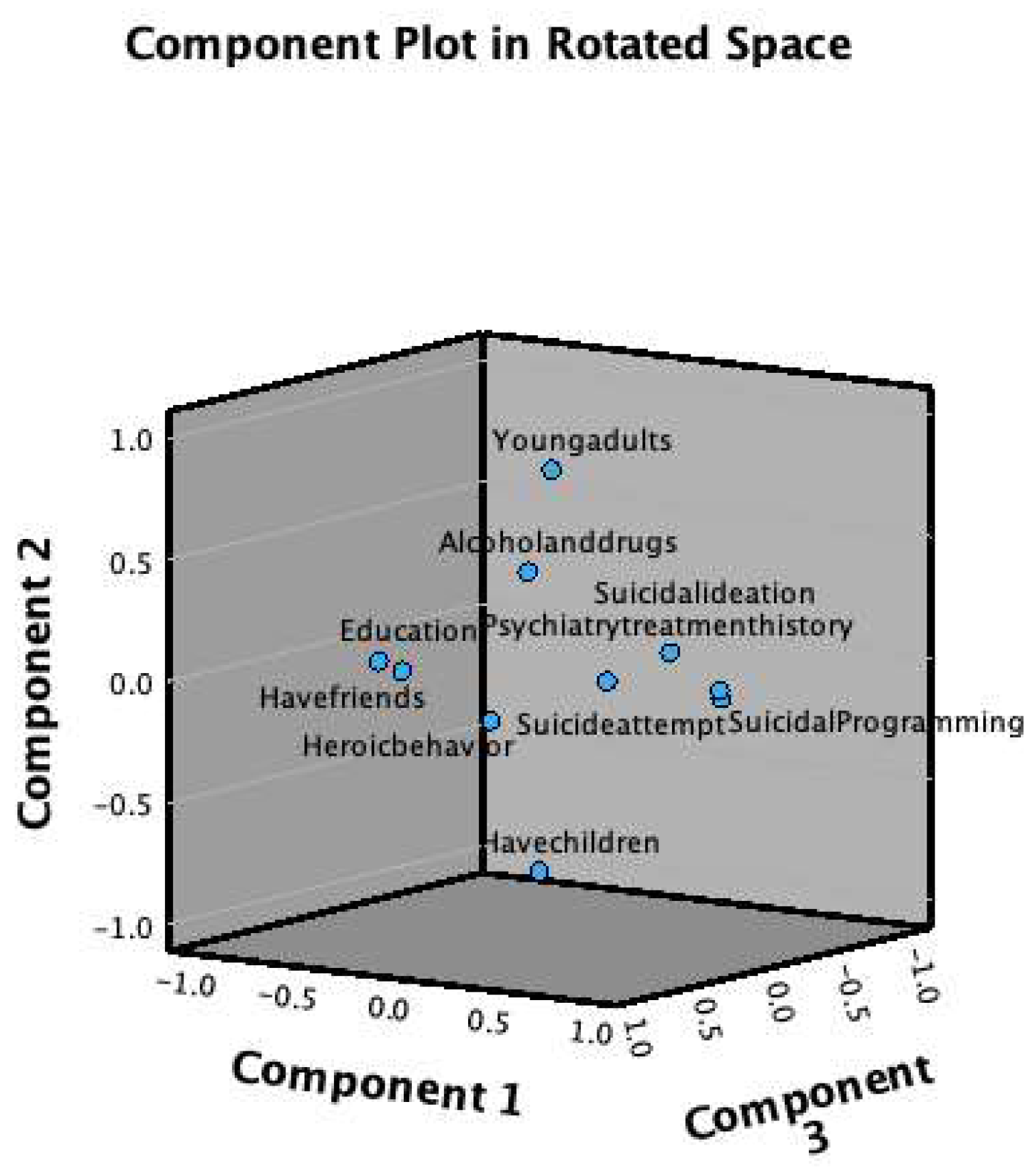

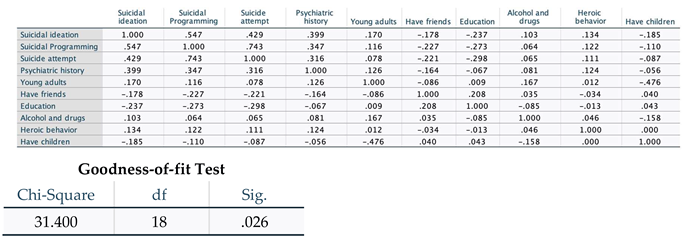

The factor analysis of 10 representative variables demonstrated a Chi-square (χ

2) of 31.4 for 18 degrees of freedom (p=0.026). There was a statistical significance between suicidal behavior and the history of having had any previous psychiatric treatment (suicidal ideation=.399; suicidal programming=.347; suicide attempt=.316). There was an association between having children and being a young adult (-.476) (

Table 3) Eight of the 10 variables demonstrated an association for one component (Graphic 3)

Graphic 3.

Association of variables in factor analysis components.

Graphic 3.

Association of variables in factor analysis components.

Discussion

Being a single white man with a mental disorder proved to be the profile that deserves the most attention from health services in the west of the state of São Paulo. The highest concentration of suicides in the population under 40 years of age in Marília coincides with the average age of the survey participants, which leads us to observe that the survey reached the target audience. An increase in the prevalence of suicide among young people has been observed in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic.[

21] Understanding the factors associated with suicidal behavior in youth is a scientific endeavor.[

22] The lack of a reason to live has been observed as a risk factor for suicidal behavior in young adults.[

23]

This survey showed a direct association in sequential severity with suicidal thinking, suicidal planning, and suicide attempts. Those who attempted suicide had it planned and had suicidal thoughts, and those who planned suicide had suicidal ideation. This association is not always found in all studies. Indeed, we cannot simply use suicidal ideation as a predictor of suicide. This study identified 313 individuals with suicidal ideation, 148 (47.3%) planned suicide and 102 (32.6%) attempted suicide. We found almost 2/3 (67.4%) of people with suicidal ideation but did not attempt suicide. This information suggests that suicidal ideation could have high sensitivity and low specificity as a predictor of suicide. This is a point of our study that encourages the elaboration of research to certify these suggestions. This requires follow-up.

If only one in three people with suicidal ideation attempts suicide, does it mean searching ideation is not a useful mean of prevention? What seems to be more appropriate is the pattern of suicidal thoughts.[

24] As understood in the fluid vulnerability theory, people with widely spaced suicidal ideations over time may have a lower risk of suicide than those who have intense and frequent suicidal ideation.[

25,

26]

These data portray the importance of assessing the frequency of suicidal ideation. As was said in the results, of those who attempted suicide more than five times, 83.3% had more than 100 suicidal ideations. Among those who had more than 100 suicidal thoughts throughout their lives, 60.1% were those who attempted suicide and in those who had suicidal thoughts less than ten times, suicide attempts occurred in 16.5%.

Typical changes in the pattern of suicidal behavior in people before the act have been described.[

27] Some of them seem to occur very close to the suicide attempt:

Five years before the attempt, they experience suicidal thoughts that persist for several years;

Two weeks before the attempt, suicidal thoughts increase in intensity and frequency, occurring almost continuously;

A week before the suicide attempt, they decide on the location;

Six hours before the suicide attempt, they experience an internal debate about whether to make it happen;

Two hours before the suicide attempt, they decide which method to use;

Thirty minutes before the attempted suicide, they decide where to attempt;

Five minutes before they attempt suicide, they make the final decision of the suicidal act.[

28]

The lifetime prevalence of attempted suicide in Marília was around 16%, which was equal to the global suicidal attempts among young populations. In medical students from Bucaramanga, in Colombia, it was 14%, in the United States it was 10% among young people aged between 18 and 24 years, and in an online questionnaire in 2015 on Facebook, it was 22.2%.[

29,

30,

31] It is much higher than in other studies such as in Campinas and Spain with 2.8% and 1.5%, respectively.[

13,

32] Some reflections are in order, as we recall that our sampling due to the pandemic was not randomized and may have attracted a greater number of respondents with suicidal behavior or experiencing problems with it. This possible attractive factor may also account for the high prevalence of suicidal ideation at a higher rate than 50%. However, we prefer not to underestimate these high numbers for the possibility that they signify the previous stages of a suicidal catastrophe where all these suicide attempts may be working as ways of preparing and acquiring suicidal competence in the population of Marília.

What we can most certainly say is that, even if overvalued, the prevalence of suicidal ideation, suicidal planning, and suicide attempts show no interference with the correlated risk factors, of which we can say even the opposite. Faced with a large sample of people with suicidal behavior, the conclusions were more trustworthy. If we had half with suicidal ideation and half without, we would obtain two well-matched groups in our sample. For quantifying the risk factors, the occurrence of a possible sampling bias in this sense can be seen as excellent.

Heroic behavior was the only variable that demonstrated an inverse pattern, with a higher prevalence of suicidal ideation and fewer suicide attempts. This may reflect the risk of dying in heroic acts, which are equivalent to suicide and are not recognized by the hero. Therefore, having greater suicidal ideation and making fewer planned suicide attempts may reflect a cover-up of suicidal acts in adventurous attitudes, such as driving at high speed. Deaths from car accidents are the biggest cause of death among young adults.[

33]

The coexistence of a mental disorder with suicidal behavior reinforces the evidence reported in the literature that describes suicides in 15% of those with mood disorders and 84% of those with borderline personality disorder attempt suicide at least once in their lifetime. An estimated 30-40% of people who died by suicide had a comorbid personality disorder.[

34] In clinical settings of schizophrenia, alcohol, and drug-related mental disorders, suicide is reported in approximately 10%.[

35]

The findings of the present study showed that the absence of interpersonal relationships is a risk for suicidal behavior which is consistent with the findings of a study carried out with adults in Rio Grande do Sul.[

36] For years, there has been a debate about the fundamental importance of interpersonal relationships for human emotional life. A few decades after Sullivan brought the interpersonal theory to academia, Gerald Klerman developed interpersonal therapy (IPT) to treat depression.[

37,

38] Since then, IPT has expanded the evidence for understanding and treating several other mental disorders, such as post-traumatic stress disorder and generalized anxiety disorder.[

39,

40,

41,

42] We understand that human happiness is directly related to human relationships.[

43] Having bad human relationships or not having enough human relationships creates existential unease. In the last decade, interpersonal theory has been used to search for a causal explanation for suicide.[

44]

Van Orden and his collaborators observed the association of suicide with family conflicts, mental disorders, previous suicide attempts, chronic physical illnesses, social isolation, unemployment, financial difficulties, and access to lethal means. Surprisingly, these are the main risk factors for suicide in the population of Marília. The interpersonal theory for suicide understands that several associated factors interact to culminate in killing oneself with or without success.[

45] Among these factors, feeling alone or being a burden to others generates the desire to kill oneself. These two factors alone cannot lead to a suicide attempt; it is necessary to overcome the fear of death pain. Over time, the maintenance of the desire to die can lead to suicidal psychological preparation. Many failed attempts or even self-inflicted injuries have this courage-building role. Once the ability to kill oneself is achieved, the act can be lethal (suicide) or not (suicide attempt).

The interpersonal theory of suicide has unfolded into increasingly elaborate understandings. Possibly the most detailed is the motivational-volitional integration (MVI) model for suicidal behavior developed by Rory O'Connor.[

46] The IMV uses interpersonal concepts within cognitive-behavioral reasoning and works with the understanding of moderators that work as filters for the factors triggering suicidality. These moderators may depend on genetic predetermination and individual personality, as well as on having a mental disorder that impairs judgment.

Many interpersonal conflicts have occurred in family experiences and between friends due to intense political ideological differences in Brazil in the last ten years.[

47] This dichotomy has been exacerbating old socioeconomic conflicts in the Brazilian population.[

48] Since 1980, there has been a progressive change in the religious profile of the Brazilian people, with an increase in proselytes of Protestantism. We cannot say that one religion is worse than another, but this rapid change is associated with social segregation.[

49] Furthermore, rates of post-pandemic depression and anxiety disorders are high.[

50]

The city of Marília was born rurally with coffee plantations and gone through industrialization. In the last two decades, there has been a significant change in the urban pattern with rapid construction and occupation of several areas of native flora. Private housing complexes have been built in these places with increased susceptibility to socio-spatial segregation.[

51] The urbanization process is referred to as a risk factor for suicide.[

52] Urbanization, combined with the replacement of human labor by machines, causes unemployment, which intensely affects young people's emotional health.[

53]

It seems that white young men subjected to morbid exclusion (

Morbosus excludens) caused by segregation are prone to committing suicide.[

8,

54]

Conclusions

The epidemiological profile of suicide in Marília comprises young adults, with non-fatal suicide being most prevalent in women, and fatal suicide most prevalent in men. Psychiatric comorbidities are frequent among those with suicidal behavior. Among the numerous factors associated with the suicidal profile, we highlight the interpersonal deficit which has increased suicide rates among teenagers in some communities.[

55]

Suicide is a manifesto of loneliness, from those visibly isolated human beings to super sociable people hiding their great existential emptiness. Realizing the human need to relate becomes imperative in a liquid society, where things have prioritized beings. As necessary as water for cellular functioning, good affection is essential for a healthy mental life.

Improving interpersonal relationships among young adults should be a priority strategy for suicide prevention. Everyone from mental health professionals to all care services must consider how inserted and satisfied people are with their relationships. Every citizen must be committed to assisting in forming a social support network. It has been shown that simple contact by messages, to know news, addressed to those who attempted suicide, reduces the incidence of new attempts and deaths.

Social segregation can affect young people's social lives and increase suicidal behavior.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely thank CAPES (Higher Education Personnel Improvement Coordination) for providing bibliographic materials.

Conflicts of Interest statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding information

None.

Data availability statement

All research data are archived and available for professional consultation.

Ethics statement

The FAMEMA Research Ethics Committee approved the study with the number: CAAE: 40205820.0.0000.5413. An informed consent form was developed.

References

- Morshidi MI, Chew PKH, Suárez L. Psychosocial risk factors of youth suicide in the Western Pacific: a scoping review. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2024;59(2):201-9. [CrossRef]

- Bachmann S. Epidemilogy of suicide and the Psychiatric Perspective. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018(15):1425. [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues CD, Souza DS, Rodrigues HM et al. Trends in suicide rates in Brazil from 1997 to 2015. Braz J Psychiatry. 2019;41(5):380-8. [CrossRef]

- Junior DFM, Felzmburgh RM, Dias AB et al. Suicide attempt in Brazil, 1998-2014: an ecologic study. BMC Public Health. 2016. [CrossRef]

- Lovero KL, Santos PF, Come AX et al. Suicide in Global Mental Health. Current Psychiatry Reports. 2023;25:255-62. [CrossRef]

- Brasil. Suicide mortality and reports of self-harm in Brazil. In: Saúde SdVe, editor. Brasilia (DF): Ministério da Saúde 2021. Acessed in 05/11/2024. Link: https://encurtador.com.br/uxGO3.

- Godoy AC. Marília had 23 suicides last year and 2022 already records one case. Jornal da manhã [Internet]. 2022; Acessed in 05/10/2024. Link: https://encurtador.com.br/qBCUZ.

- Rodrigues JFR. What is suicide: epidemiological profile of suicide in the city of Marília: propositions for prevention [O que é o suicídio: perfil epidemiológico de suicídio na cidade de Marília: proposições para prevenção]. São Paulo: Dialética; 2022. 312 p. [CrossRef]

- Knipe D, Padmanathan P, Newton-Howes G et al. Suicide and self-harm. Lancet. 2022;14(399):1903-16. [CrossRef]

- Krupnik V, Danilova N. To be or not to be: The active inference of suicide. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2024;157:105531. [CrossRef]

- Bryan CJ. Rethinking Suicide. New York (NY): Oxford; 2022. 224 p. ISBN: 9780190050634.

- Silva RJdS, Santos FAL, Soares NMM et al. Suicidal Ideation and Associated Factors among Adolescents in Northeastern Brazil. Scientific World Journal. 2014. [CrossRef]

- Botega NJ, Marín-León L, Oliveira HBd et al. Prevalence of suicide ideation, plan and attempt: a population-based survey in Campinas, São Paulo, Brazil. Cad Saude Publica. 2009;25:2632-8. [CrossRef]

- McGrath MO, Krysinska K, Reavley NJ et al. Disclousure of Mental Heath Problems or Suicidality at Work: A Systematic Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20(8):5548. [CrossRef]

- Melo IJWTd, Lima MGdC, Estevam DCSP et al. SUICIDES IN MINAS GERAIS: Association of gender and study time [SUICÍDIOS EM MINAS GERAIS: Associação de gênero e tempo de estudo]. Psicol Saúde e Debate. 2024;10(1):444-56. [CrossRef]

- Dumith SC, Demenech LM, Carpena MX et al. Suicidal thought in southern Brazil: Who are the most susceptible? J Affect Disord. 2020;260:610-6. [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues JFR, Araújo Filho GM, Rodrigues LP et al. Development and validation of a questionnarie to measure association factors with suicide: An instrument for a populational survey. Health Science Reports. 2023;62023;6:e:e1396. [CrossRef]

- Botega NJ, Barros MBA, Oliveira HB et al. Suicidal behavior in the community: Prevalence and factors associated with suicidal ideation. Braz J Psychiatry. 2005;27(1):45-53. [CrossRef]

- Galynker I. The Suicidal Crisis: Clinical Guide to the Assessment of Imminent Suicide Risk. New York (NW): Oxford; 2017. 344p. ISBN: 9780190260859.

- Siqueira AL. Sample sizing for studies in the health area [Dimensionamento de amostra para estudos na área da saúde]. Belo Horizonte (MG): Folium Editorial; 2017. 413 p. ISBN: 9788584500222.

- Naveed S. 50.4 Current Rates and Epidemiological Trends of Suicide in The United States: An Alarming Phenomena. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2023;62. [CrossRef]

- McClelland H, Evans JJ, O'Connor RC. A Qualitative Exploration of the Experiences and Perceptions of Interpersonal Relationships Prior to Attempting Suicide in Young Adults Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(13). [CrossRef]

- Madeira ARS-R, Janeiro LdB, Carmo CIG et al. Reasons for Living Inventory for Young Adults: Psychometric Properties Among Portuguese Sample. Omega. 2022;85(4):807-903. [CrossRef]

- Bryan CJ. Balance Beams and Suicide-Risk Screening. Rethinking suicide: why prevention fails, and how we can do better. New York (NY): Oxford; 2022. p. 49-76. ISBN: 9780190050634.

- Bryan JC, Rudd MD. The Importance of Temporal Dynamic in the Transition From Suicidal Thought to Behavior. Cli Psychol: Sci and Pract. 2016. [CrossRef]

- Bryan JC, Butner JE, May AM et al. Nonlinear change processes and the emergence of suicidal behavior: a conceptual model based on the fluidal vunerability theorie of suicide. New Ideas Psychol. 2020;57. [CrossRef]

- Millner AJ, Lee MD, Nock MK. Describing and Measuring the Pathway to Suicide Attempts: A Preliminary Study. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2016. [CrossRef]

- Bryan CJ. Change between suicide-risk states can occur suddenly. Rethinking suicide: why prevention fails, and how we can do better. New York (NY): Oxford; 2022. p. 88-9. ISBN: 9780190050634.

- Pinzón-Amado A, Guerrero S, Moreno K et al. Suicidal ideation in medical students: prevalence and associated factors [Ideación suicida en estudiantes de medicina: prevalencia y factores asociados]. Rev Colomb Psiquiatr. 2013;43:47-55. [CrossRef]

- Wolford-Clevenger C, Stuart GL, Elledge LC, et al. Proximal Correlates of Suicidal Ideation and Behaviors: A Test of The Interpersonal-Psychological Theory of Suicide. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2020;50:249-62. [CrossRef]

- Nagafuchi T. Searching for Voices in the Silence: Suicide, Gender and Sexuality in the Digital Age [Em Busca de Vozes no Silêncio: Suicídio, Gênero e Sexualidade na Era Digital]. In: Marqueti F, editor. Suicídio: Escutas do Silêncio. São Paulo (SP): Editora Unifesp; 2108. p. 147-75. ISBN: 9788555710308.

- Gabilondo A, Alonso J, Pinto-Meza A et al. Prevalence and risk factors of suicide ideas, plans and attempts in the general Spanish population. Results of the ESEMeD study [Prevalencia y factores de riesgo de las ideas, planos e intentos de suicidio en la población general española. Resultados del estudio ESEMeD]. Med Clin (Barc). 2007;129:494-500. [CrossRef]

- Chandran A, Sousa TR, Guo Y et al. Vida No Transito Evaluation Team. Road traffic deaths in Brazil: rising trends in pedestrian and motorcycle occupant deaths. Traffic Inj Prev. 2012;13:11-6. [CrossRef]

- Guerreiro DF, Ribeiro D. Personality disorders [Perturbações da personalidade]. In: Saraiva CB, Peixoto B, Sampaio D, editors. Suicide and self-injurious behaviors: from concepts to clinical practice [Suicídio e comportamentos autolesivos: dos conceitos à prática clínica]. Lisboa (PT): Lidel; 2014. p. 285-95. ISBN: 978-989-752-042-6.

- Santos JC, Cabral AS, Vieira F. Risk of suicide and compulsory hospitalization - ethical and medico-legal aspects [Risco de suicídio e internamento compulsivo - aspectos éticos e médico-legais]. In: Saraiva CB, Peixoto B, Sampaio D, editors. Suicide and self-injurious behavior: from concepts to clinical practice [Suicídio e comportamento autolesivos: dos conceitos à prática clínica]. Lisboa (PT): Lidel; 2014. p. 203-11. ISBN: 978-989-752-042-6.

- Pereira AS, Willhelm AR, Koller SH et al. Fatores de risco e proteção para tentativa de suicídio na adultez emergente. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva. 2018;23:3767-77. [CrossRef]

- Sullivan HS. The Interpersonal Theory of Psychiatry. New York: Norton; 1997. 393 p. ISBN: 9780393001389.

- Klerman GL, Weissman MM, Rounsaville BJ et al. Interpersonal Psychotherapy of depression: a brief, focused, specific strategy. Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers; 2004. 256 p. ISBN: 9781568213507.

- Weissman MM, Markowitz JC, Klerman GL. Comprehensive Guide to Interpersonal Psychotherapy. New York: Basic Books; 2000. 475 p. ISBN: 978-0465095667.

- Stuart S, Robertson M. Iterpersonal Psychotherapy: a clinician's guide. London: Hodder Arnold; 2003. 315 p. ISBN: 9781444167474.

- Weissman MM, Markowitz JC, Klerman GL. Clinicians's Quick Guide to Interpersonal Psychotherapy. New York: Oxford University Press; 2007. 183 p. ISBN: 9780195309416.

- Schoedl AF, Lacaz FS, Mello MF et al. Interpersonal Psychotherapy: Theory and Practice [Psicoterapia Interpessoal: Teoria e Prática]. São Paulo: Livraria Médica Paulista; 2009. 245 p. ISBN: 9788599305416.

- Rodrigues JFR. Very Brief Introduction on the Fourfold Valuation of Morals [Brevíssima Introdução sobre a Tetravaloração da Moral]. Marília - SP: Apple Books; 2014. [CrossRef]

- Orden KAV, Witte TK, Cukrowicz KC et al. The Interpersonal Theory of Suicide. Psychol Rev. 2010;117(2):575-600. [CrossRef]

- Chu C, Buchman-Schimitt JM, Stanley IH et al. The Interpersonal Theory of Suicide: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of a Decade of Cross-National Research. Psychol Bull. 2017;143(12):1313-45. [CrossRef]

- O'Connor R, Kirtley OJ. The integrated motivational-volitional model of suicidal behaviour. Phil Trans R Soc B. 2018;373. [CrossRef]

- Igreja RL. Populism, inequality, and the construction of the “other”: an anthropological approach to the far right in Brazil. Vibrant. 2021;18. [CrossRef]

- Sousa Filho JFd, Pedeira SC, Santos GFd et al. Racial and economic segregation in Brazil: a nationwied analysis of socioeconomic and socio-spatil inequalities. R bras Est Pop. 2023;40:1-24. [CrossRef]

- Potter JO, Amaral EFL, Woodberry RD. The Growth of Protestantism in Brazil and Its Impact on Male Earnings, 1970-2000. Soc Forces. 2014;93(1):125-53. [CrossRef]

- Feter N, Caputo EL, Leite JS et al. Depression and anxiety symptoms remained elevated after 10 months of the COVID-19 pandemic in southern Brazil: findings from the PAMPA cohort. Public Health. 2022;204:14-20. [CrossRef]

- Araujo ASd, Queiroz Filho APd. Mapping socio-spatial segregation in the city of Marília/SP (Brazil). Revista Brasileira de Geografia Física. 2018;11(2):431-41. [CrossRef]

- Qin P. Suicide risk in relation to level of urbanicity - a population-based linkage study. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2005;34:846-52. [CrossRef]

- Chen M, Huang X, Cheng J et al. Urbanization and vulnerable employment: Empirical evidence from 163 countries in 1991-2019. Cities. 2023;135. [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues JFR. Morbosus excludens: The Pathogen of Suicide. Zenodo [Internet]. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Senapati RE, Jena S, Parida J et al. The patterns, trends and major risk factors of suicide among Indian adolescents - a scoping review. BMC Psychiatry. 2024;24(1):35. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).