1. Introduction

In the United States, approximately 15% of high school students reported having any illicit drug use, including marijuana, heroin, methamphetamines, inhalants, hallucinogens or ecstasy [

1]. Youth’s drug use is directly linked with increased sexual risk behaviors, experience of violence, adverse mental health and suicidality among adolescents and youths [

2]. Data suggests that young students, as they transition to colleges, are influenced by their peers to undertake risky behaviors including drug use, suicidal thoughts, and non-suicidal self-injury [

3].

Prevalence and the patterns of adolescents’ drug use are often correlated with concurrent other high-risk behaviors, such as engaging in unprotected sex, sex with multiple partners, and having intimate partners who use drugs [

4,

5]. In 2023, the prevalence of illicit drug use in the past year increased with increasing age of the youths – 10.9% in eighth graders, 19.8% in 10

th graders, and 31.2% in 12

th graders [

5]. According to the National Survey on Drug Use and Health data (2004-2019), the pattern of drug use initiation varies by race and ethnicity [

6]. In an earlier study of trends and patterns of youth’s substance uses, lifetime use of marijuana decreased in the U.S. during 2013-2019 [

7]. In 2019, 21.7% reported current marijuana use, while 13.7% had current binge drinking, and 7.2% had current prescription opioid misuse.

Youth’s drug use is also associated with sexual risk behaviors that make young people vulnerable to sexually transmitted infections (STIs), increased prevalence of teen age pregnancy, and poor mental health [

2,

5]. Unfortunately, Mississippi has the highest combined rates of major STIs [

8] and among the states with high teen pregnancy rates [

9].

There are several gaps in the knowledge about youth’s drug use: (1) Information about the recent prevalence and trend of different drugs is lacking in this age group; (2) Mississippi having issues of poor health outcomes, it was imperative to conduct an in-depth study to understand if these adverse health outcomes are some way or the other related to youth’s drug use risky behaviors; and (3) There is also gap in the knowledge in the prevalence ratio between the rates of different drugs commonly used by the youth and adolescents in Mississippi and the nation. Therefore, the objectives of this study were to: (1) Identify the prevalence ratio of categories of drug use among adolescents between Mississippi and the nation; and (2) Compare the drug use trends among adolescents from 2001 to 2021 in Mississippi and the United States.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Source

National and Mississippi YRBSS data were used for this study. YRBSS is a set of survey that tracts the major health risk behavior factors among adolescents. YRBSS has two components: The first component is the national survey conducted by CDC that includes high school students from both private and public schools of 50 US states and the District of Columbia. The second component is surveys conducted by the Department of Health and Education at the state, tribal, territorial or local levels among respective public high school students. Data used for this study was drawn from both sources. YRBSS is a three-stage complex sample design to ensure representative samples being collected. The first stage determines the primary sampling unit (PSU) to be at the county (or comparable geographic unit) level. The PSUs are further categorized into strata according to their metropolitan location and racial composition. For the second stage, secondary sampling unit (SSU) is defined at the school level. Both PSUs and SSUs are sampled with probability proportional to overall school enrollment size. The third stage is random sampling of one or two classrooms in each of grades 9-12 of the selected schools. YRBSS is conducted biannually [

10]

2.2. Measurements

Student’s responses to drug use related YRBSS survey questions, which are ordinal or nominal data, are re-coded as binary data (Yes, No) for analysis. Following are the six data points used for this study: QN45 - Ever used marijuana; QN51 - Ever used inhalants; QN52 - Ever used heroin; QN53 - Ever used methamphetamines; QN55 - Ever injected any illegal drug; QN56 - Were offered, sold, or given an illegal drug on school property.

Survey questions relevant to this study also included: gender (male, female) and race/ethnicity (Non-Hispanic American Indian or Alaska Native, Non-Hispanic Asian, Non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, Non-Hispanic Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, Non-Hispanic White and Non-Hispanic Multiple race). Race variable used in this study has four values (White, Black, Hispanic and Multiple race non-Hispanic) [

11,

12].

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Drug use prevalence estimates and there 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated and compared between national and Mississippi adolescents for survey year 2021. Survey Chi-squared tests, a design-based Wald tests of independence were also applied for the comparison for all students, and by gender and race, separately. In the rare instances where the 95% CI overlap but the p-value is less than 0.05, we reported the difference as statistically significant [

13,

14,

15].

For the trend analysis, we took the approach as prescribed by CDC. First, we used logistic regression models to detect linear and/or non-linear (quadratic or cubic) trends. Log odds of each variable were estimated as a function of time, time in quadratic term, and time in cubic term, respectively. Time variables were created by coding each year with orthogonal coefficients, and they were treated as continuous covariate in the models. Only the highest-order time variable in the model was considered valid. Secondly, if only a linear year-contrast term was found to be significant, then the associated beta and p-value for that term was used to determine the direction and significance of the trend [

16]. If quadratic and/or cubic changes were detected, we took the next step to calculate the adjusted (by sex, race and grade) prevalence and standard error by survey year and export these values into Joinpoint software to determine the critical values of the joints for trend segments. Parametric method was applied to calculate the confidence intervals for Annual Percentage Change (APC) of the resulting segments and Average Annual Percentage Change (AAPC) of the whole trend [

17,

18].

IBM SPSS Modeler (version 18.4) was used to produce sample characteristic statistics. Statistical software R (version 4.4.0) was used for summary statistics and logistic regression models. R with its survey packages was identified by CDC as an appropriate software that is capable of accounting for the complex sampling design of YRBSS data [

19]. Joinpoint software (version 5.1.0) was downloaded with permission from National Cancer Institute and used for joinpoint regression analysis.

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

The 2021 YRBS sample sizes for US and Mississippi were 17,232 and 1,747, respectively. Gender distribution for US and Mississippi indicates that female and male students were approximately equally represented: 47.3% and 49.2% for female respectively. Significant variance was observed in the racial distribution of the sample. National YRBS sample consisted of 53.1% White, 13.5% Black, 18.8% Hispanic and 5.8% non-Hispanic multiple races, while Mississippi YRBS sample consisted of 33.8% White, 47% Black, 8.9% Hispanic and 3.3% non-Hispanic multiple races. This difference reflects the underline racial demographics in Mississippi and the United States as a whole. Compared to the national sample, Mississippi sample included more 9th graders (36.1% vs. 27.0%) and less 12th graders (17.5% vs. 22.3%), while the percentages for 10th and 11th graders were roughly similar.

3.2. Comparison of Drug Use Related Risk Behaviors between Mississippi and the US

Table 1 shows the comparison of the prevalences of drug use related risk behaviors between Mississippi and the United States in 2021. To the question “have you ever used marijuana?”, there was no significant difference between Mississippi (MS) and the United States (US). However, compared the US, MS adolescents had significantly higher prevalences for ever used inhalants, heroin, methamphetamines, drug injection and were more likely to be offered, sold, or given an illegal drug on school property. The prevalence ratio for the above variables was 0.9 (p = 0.19), 1.5 (p < 0.001), 3.3 (p < 0.001), 2.6 (p < 0.001), 2.7 (p < 0.001), 1.5 (p < 0.001), respectively. Overall, Mississippi adolescents exhibited significantly greater risk behaviors related to drug use.

Further analysis of subgroups shows that, compared to the US, the elevated risk behaviors related to inhalants, heroin, methamphetamines, illegal drug injection and were offered, sold or given an illegal drug on school property in Mississippi high school students were not all distributed evenly among female and male students, nor were they evenly distributed among the race categories.

3.2.1. Marijuana and Inhalant Use

As shown in

Table 2, compared to the US, Mississippi youth marijuana use had no significant difference, neither as a whole, nor by gender or race. Compared to the US, inhalants use was significantly greater for male students in Mississippi (12.8%

vs. 6.8%,

p <0.001), but not for female students (10.6%

vs. 9.4%,

p = 0.47). Compared to the US, inhalants use was significantly greater only for Black students in Mississippi (11.8%

vs. 7.0%,

p = 0.02).

3.2.2. Heroin and Methamphetamines Use

As shown in

Table 3, compared to the US, heroin use prevalence was significantly higher for both female (2.3%

vs. 0.8%,

p = 0.02) and male (5.9%

vs. 1.6%,

p <0.001) students in Mississippi. Compared to the US, heroin use prevalence in Mississippi was significantly higher for Black students (5.8%

vs. 1.7%,

p < 0.001) and Hispanic students (8.9%

vs. 1.6%,

p = 0.03), but significantly lower in multiple race non-Hispanic students (0%

vs. 1.5%,

p <0.001) and no difference for White students (1.5%

vs. 1.0%,

p = 0.61). Compared to the US, risk behavior related to methamphetamine use in Mississippi was significantly more prevalent in male students (5.6%

vs. 1.9%,

p < 0.001), but not female students (2.7%

vs. 1.4%,

p = 0.08). Compared to the US, methamphetamine use prevalence in Mississippi was significantly higher for Black students (5.4%

vs. 2.0%,

p = 0.01) and Hispanic students (10.7%

vs. 2.3%,

p = 0.01), but no significant difference was observed in White students (2.3%

vs. 1.4%

p = 0.33) or in multiple race students (2.0%

vs. 2.2%,

p = 0.92).

3.2.3. Illegal Drug Injection and Drug on School Property

As shown in

Table 4, compared to the US, risk behavior related to illegal drug injection in Mississippi was significantly more prevalent in both female students (2.6%

vs. 0.9%,

p = 0.01) and male students (4.6%

vs. 1.7%,

p < 0.001). Compared to the US, illegal drug injection prevalence in Mississippi was significantly higher for Black students (4.3%

vs. 1.9%,

p = 0.03) and Hispanic students (8.1%

vs. 1.8%,

p < 0.001), but no significant difference was observed in White students (2.0%

vs. 1.1%

p = 0.38) or in Multiple race students (2.0%

vs. 1.8%,

p = 0.92). Compared to the US, risk behavior related to being offered, sold, or given an illegal drug on school property in Mississippi was significantly more prevalent in both female students (19.5%

vs. 13.9%, p < 0.001) and male students (22.4%

vs. 13.8%, p < 0.001). Compared to the US, the prevalence of being offered, sold, or given an illegal drug on school property in Mississippi was significantly higher for White students (20.6%

vs. 13.2%,

p < 0.001), Black students (19.6%

vs. 13.7%,

p = 0.01) and Hispanic students (29.2%

vs. 16.7%,

p < 0.001), but no significant difference was observed in Multiple race students (15.8%

vs. 13.8%,

p = 0.63).

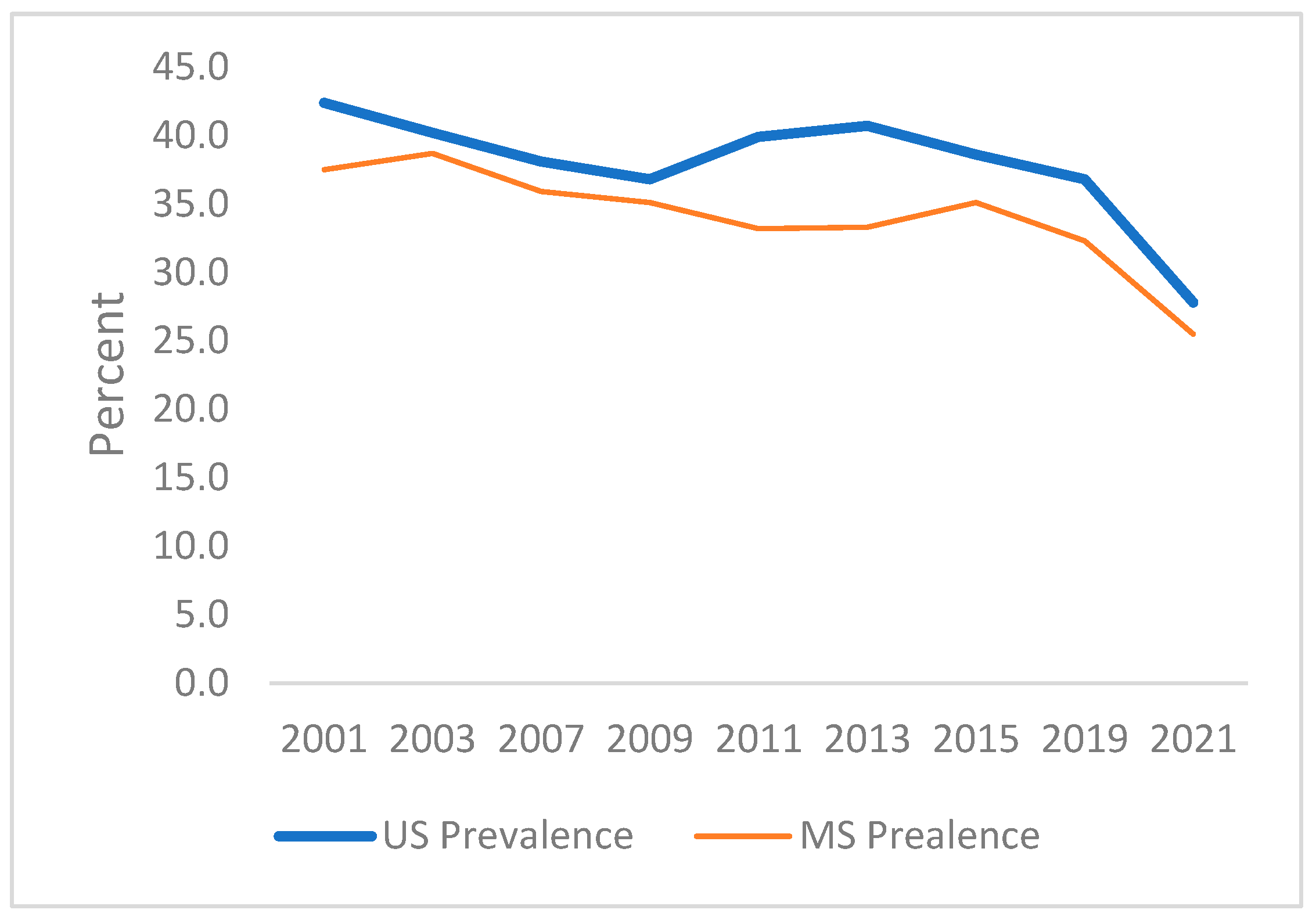

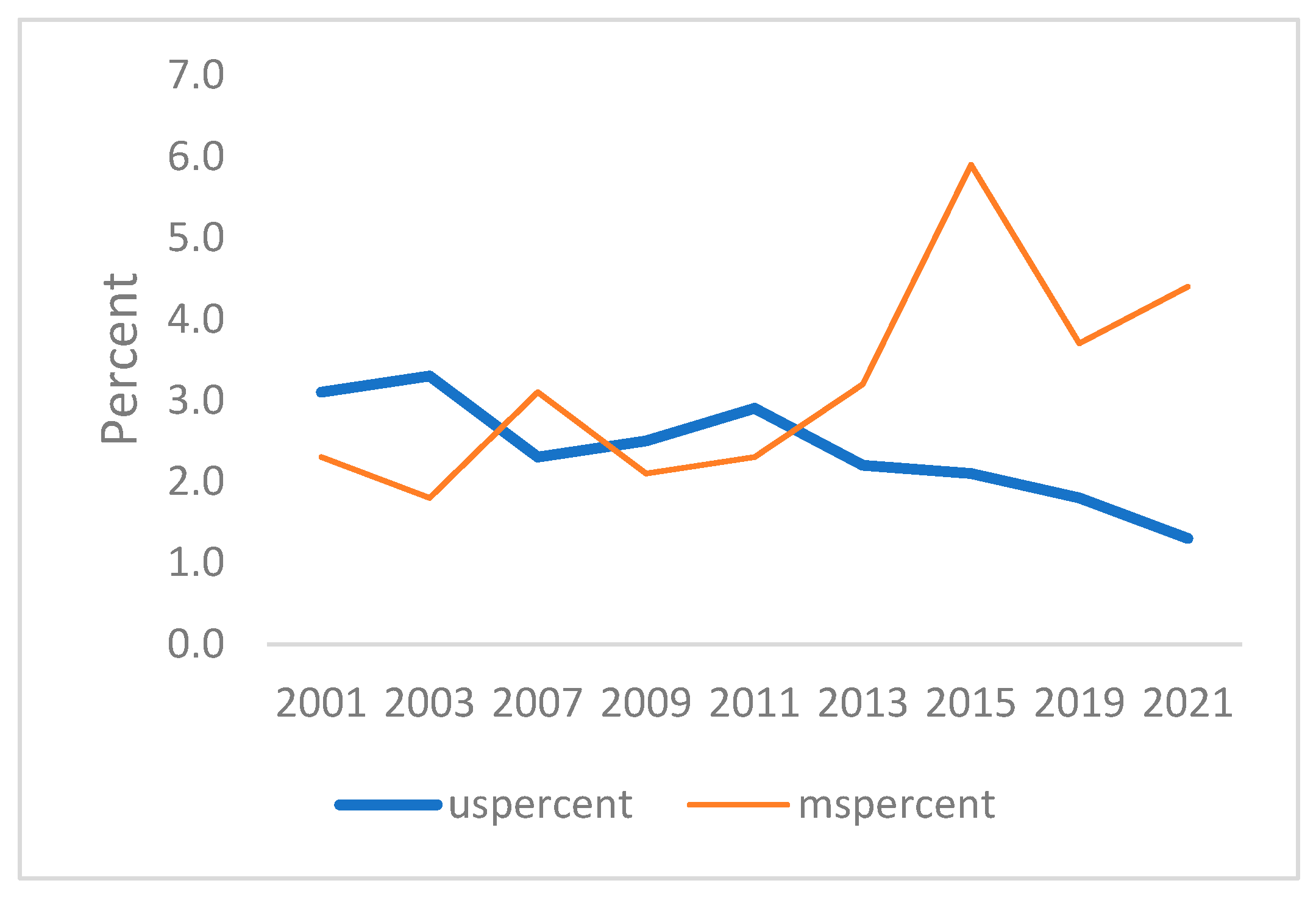

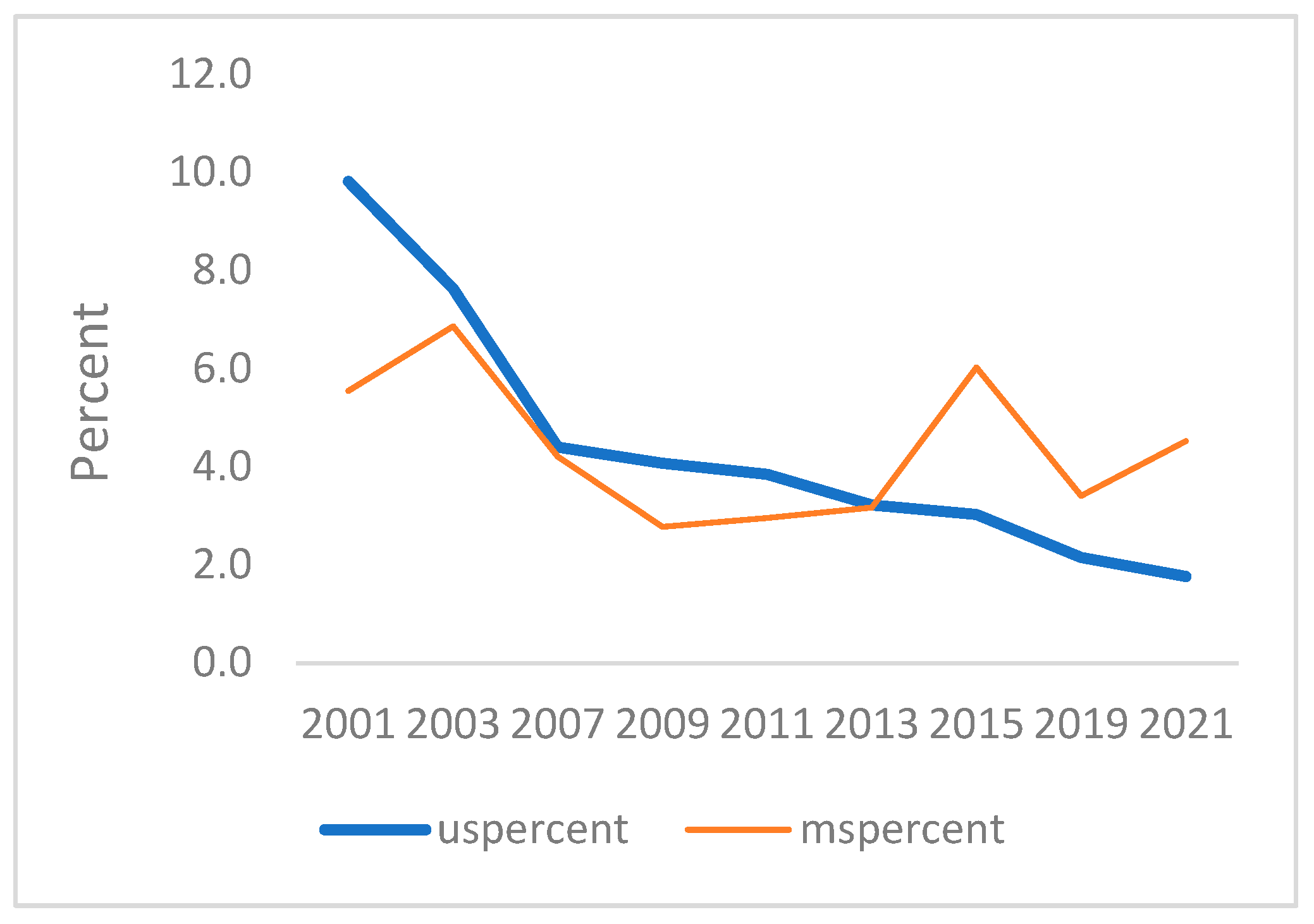

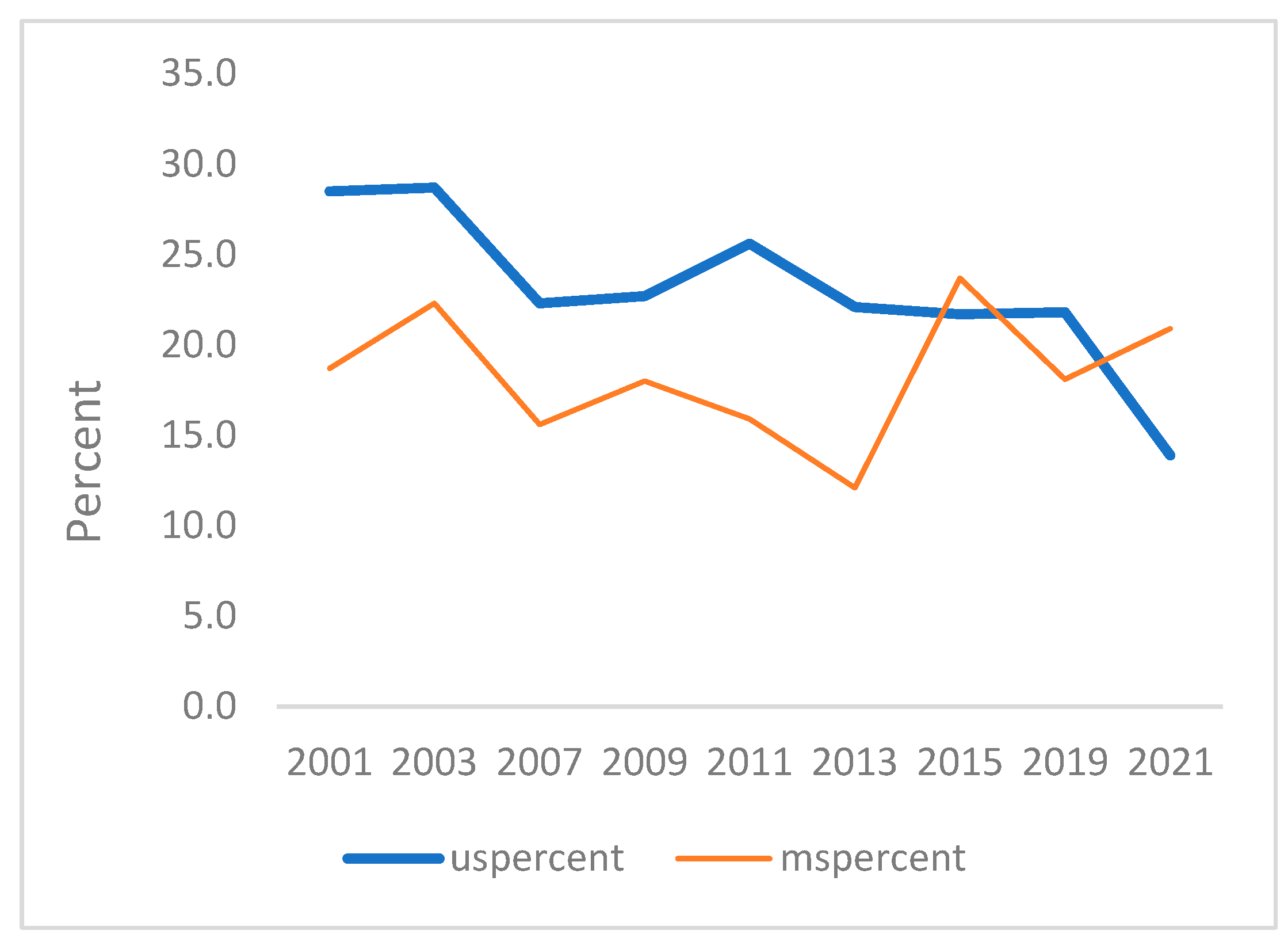

3.3. Trend of Drug Related Risk Behaviors from 2001 to 2021

Table 5 highlights the average AAPC for each response to the six survey questions related to drug use, in the US and in Mississippi. Nationally, all the six drug-use related risk behaviors had a significant decrease. AAPC from 2001 to 2021 were -1.2% (

p < 0.01), -4.2% (

p < 0.001), -4.5% (

p < 0.001), -8.5% (

p < 0.001), -3.6% (

p < 0.001) and -2.6% (

p < 0.001), for ever used marijuana, inhalant, heroin, methamphetamines, injected drugs and were offered, sold or given an illegal drug on school property respectively. In Mississippi, however, only marijuana use showed a decrease trend, with AAPC being -1.5% (

p <0.01). Contrary to the US trend, heroin use and injection of illegal drugs showed an increase pattern (

p < 0.01 for both). Inhalant, methamphetamines, and were ever offered, sold or given an illegal drug on property showed no significant change.

Figure 1,

Figure 2,

Figure 3,

Figure 4,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6 demonstrate the linear variations of unadjusted prevalence data of drug use from 2001 to 2021 in the US

vs. Mississippi. These graphs visually confirm the statistics obtained through the trend analysis, as stated earlier.

4. Discussion

This study highlights significant concerns regarding high-risk substance use behaviors among Mississippi teens compared to their national peers. The results of this study are consistent with other national research suggesting that the use of most substances among teenagers has remained stable or declined [

1,

20,

21]. Our data suggest that while national trends indicate a decrease in all six major drug-related behaviors over time, Mississippi teens reported higher instances of using inhalants, heroin, methamphetamine, injecting illegal drugs, and being offered, sold, or given illegal drugs on school property. This discrepancy underscores the need for targeted interventions in Mississippi to address these alarming trends because a strong body of research indicates that adolescent substance abuse results in negative physical and mental health consequences [

3,

21,

22,

23], as well as academic [

24], social [

25], and high-risk behaviors, leading to legal issues and potential criminal justice involvement [

26].

4.1. Gender and Race

While the gender distribution of the national and Mississippi estimates was approximately equal, the racial distribution varied significantly. This difference primarily reflects the underlying racial demographics in Mississippi, where Black youth are over-represented. The Mississippi sample includes more 9th graders and fewer 12th graders than their national counterparts. However, the number of 10th and 11th graders was similar in both cohorts. Similar disparities in racial demographics and grade distribution have been noted in other studies. For instance, a study by Johnston et al. (2020) on substance use among adolescents highlighted that demographic differences, particularly racial and educational disparities, significantly impact substance use patterns [

24,

26]. Additionally, the CDC's Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System (YRBSS) data suggests that regional differences, such as those seen in Mississippi, can influence the prevalence of high-risk behaviors among youth [

23].

4.2. Drug Use-Related Comparisons

While students from both cohorts agreed with the statement about ever using marijuana in equal measure, that is where the similarities ended. In all the following categories, Mississippi youth reported significantly higher rates of substance use than their US counterparts.

In this study, we found Mississippi youth to be exhibiting dangerous, high-risk substance behaviors. When queried about inhalant use, Mississippi students were 1.5 times more likely to have tried or used them than the US sample. Prevalence rates for heroin use were reported at 3.4 times the rate of the national sample. Mississippi students use methamphetamine at a rate 2.5 times that of US youth. They reported injecting any illegal drug at 2.8 times the rate of their national peers. Finally, they were offered, sold, or given an illegal drug on school property at a rate 1.5 times more often than the US sample. Differences in substance use behaviors between Mississippi youth and their national peers can be attributed to several factors, including socioeconomic conditions, education, and mental health resources. Socioeconomic conditions include poverty and economic hardship. Mississippi has one of the highest poverty rates in the United States, where 19.1% of its residents live below the poverty line (US 11.7%) [

27]. Mississippi’s economy and healthcare system rank 50

th in the US. This has resulted in its residents having the worst health outcomes, leaving Mississippians with a disproportionate disease and illness burden [

28,

29]. Economic hardship is strongly associated with increased substance use among adolescents. Families experiencing financial stress may have limited access to education and healthcare resources, including mental health services, which can lead to higher rates of substance abuse [

30].

In Mississippi, educational disparities are found in preschool, where only 51% of three and four-year-old children are enrolled in early education, and only 34% of kindergarten students score at or above state benchmarks. Three-quarters of public school students are economically disadvantaged, with 54% of those students being African American. In 2018, 21.5% of African American students met the ACT college benchmarks in reading and math, 16 percentage points below the state average and 32 percentage points below the average score for white students [

31]. Mississippi schools have fewer resources for comprehensive drug education and prevention programs when compared to schools in other states. Effective substance abuse prevention programs are crucial in reducing the rates of adolescent drug use [

32].

Mississippi ranks 47

th in the nation for access to mental health care [

33]. Mississippi is predominately a rural state [

34]. Research suggests that access to mental health services is often limited in rural areas, including many parts of Mississippi. Adolescents with untreated mental health issues may turn to substance use as a form of self-medication [

35].

4.3. Drug Use-Related Comparisons by Race and Gender

Upon closer inspection of the data, inhalant and methamphetamine use prevalence was significantly higher for Mississippi males compared to the US sample. Heroin use prevalence did not differ based on gender. However, heroin use prevalence was significantly higher for Black and Hispanic students and lower in multiple-race non-Hispanic students, with no difference for White students. However, national prevalence studies have reported higher rates of substance use in white students compared to their Black or Hispanic counterparts [

30,

36]. While the CDC Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance (YRBSS) from 2019 also found higher substance use rates among White students, the study found that certain high-risk behaviors, such as injection drug use, were reported more frequently among some minority groups [

37,

38,

39]. This supports our finding that both Mississippi female and male students who are Black or Hispanic reported a significantly higher prevalence of injecting illegal drugs compared to the US sample.

Finally, high-risk behavior relating to being offered, sold, or given an illegal drug on school property in Mississippi was significantly more prevalent for both female and male white, Black, and Hispanic students when compared to the national sample. Again, research suggests structural components may contribute to these behaviors, including socioeconomic conditions, educational disparities mentioned earlier, and regional differences in drug availability and enforcement. Economic hardship is often correlated with higher rates of substance abuse and related activities. In schools located in areas of high poverty rates, students might be exposed to drug-related activities due to the broader community context where drug dealing may be an important source of income [

32,

39]. Many schools in Mississippi are underfunded, lacking resources for comprehensive drug prevention programs. This could result in decreased awareness of the risks associated with substance use [

40]. The availability of drugs and regional law enforcement practices can significantly impact the prevalence of drug-related activities in schools. Mississippi might have counties where drug trafficking is more prevalent, increasing the likelihood of students being exposed to drugs. Furthermore, differences in local law enforcement practices can affect how drug-related activities are monitored and controlled within school environments [

4.5. Limitations

YRBSS data focuses on teens attending school. However, it does not account for students who have dropped out of high school, were homeschooled, attended alternative schools, or were part of the estimated 5% of youth who have never attended school [

41]. According to the US Department of Education, in 2001, the high school dropout rate was 9.9% [

41]. Of Mississippi high school students entering school in 2001, the dropout rate by 2004 was 26%. The Mississippi dropout rates did not fall to 10% until 2019 [

42]. This cross-sectional study also makes determining whether students are over or under-reporting health-related behaviors impossible.

We did not include prescription opiates in our study. This information would have enhanced our understanding of recent trends in prescription drug use and the opioid epidemic. The YRBSS does not include electronic vape pen use, which has become increasingly popular with teens [

43,

44]. Our data suggests that polysubstance use needs additional focus, as new studies are providing compelling evidence that abusing opioid prescription drugs increases the likelihood of dangerous polydrug abuse [

45].

5. Conclusion

An important finding in this study is that while overall teen substance use is decreasing nationwide, in Mississippi, this is not the case. While Mississippi high school student marijuana use is declining slightly, they are significantly more likely to use inhalants, methamphetamine, and heroin and practice high-risk behaviors, including injecting drugs and accessing drugs at school, than their national peers. We must find ways in which to intervene. Mississippians face far greater rates of poverty and lack of access to health and mental health services due to inequities in the healthcare system. As a result, Mississippi high school students who use drugs are at risk for a bevy of negative outcomes, including unprotected sex, sexually transmitted infections, and teen pregnancy in a State where reproductive health is severely limited, and infant and mortality deaths occur at twice the national average.

Because of the significant prevalence of illicit drug use among Mississippi adolescents, there is an urgent need for an integrated approach to reverse the rapidly growing problem. The public health risks for polysubstance use call for prevention and intervention programs.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.Z. and A.K.M.; Methodology, Z.Z.; Validation, Z.Z., A.K.M, J.A.S. and L.Z.; Data curation and statistical analysis, Z.Z. and L.Z; Writing—original draft preparation, Z. Z, A.K.M. and J.A.S.; Review and editing, A.K.M., Z.Z., J.A.S. and L.Z.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance—United States, 2019. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report Suppliments 2020, 69(1):1-83. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/data/yrbs/pdf/2019/su6901-H.pdf (accessed on 25 May 2024).

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Youth Risk Behavior Survey Data Summary & Trends Report, 2009–2019. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/data/yrbs/pdf/YRBSDataSummaryTrendsReport2019-508.pdf (accessed on 20 May 2024).

- Hofer, M.K.; Robillard, C.L.; Legg, N.K.; Turner, B.J. Influence of perceived peer behavior on engagement in self-damaging behaviors during the transition to university. Journal of Research on Adolescence 2024, Available online: https://doi.org/10.1111/jora.12933 (accessed on 25 May 2024).

- Singh, D.; Azuan, M. A.; Narayanan, S. High-risk sexual behavior among Malaysian adolescents who use drugs: A mixed-methods study of a sample in rehabilitation. Journal of Substance Use. 2024, 1–6. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1080/14659891.2024.2329885 (accessed on 25 May 2024).

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Substance use and sexual risk behaviors among youth. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/substance-use/pdf/dash-substance-use-fact-sheet.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2024).

- Alcover, K.C.; Lyons, A.J.; Amiri, S. Patterns of mean age at drug use initiation by race and ethnicity, 2004–2019, Journal of Substance Use and Addiction Treatment, 2024, 161, Available online: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.josat.2024.209350 (accessed on 12 May 2024).

- Jones, C.M.; Clayton, H.B.; Deputy, N.P.; Roehler, D.R.; Ko, J.Y.; Esser, M.B.; Brookmeyer, K.A.; Hertz, M.F. Prescription opioid misuse and use of alcohol and other substances among high school students - Youth Risk Behavior Survey, United States, 2019. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report Suppliments. 2020, 69(1):38-46. [CrossRef]

- Ozua, M. L; Artaman, A. A retrospective study of the incidence of bacterial sexually transmitted infection (Chlamydia and Gonorrhea) in the Mississippi Delta before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Cureus. 2022, 14(3): e23712. [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Center for Health Statistics. Teen birth rate by state. 2021. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/pressroom/sosmap/teen-births/teenbirths.htm, (accessed on 12 May 2024).

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Overview and Methods for the Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System — United States, 2021. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report Suppliments 2023, 72(1);1–12. Availabble online: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/72/su/su7201a1.htm (accessed on 10 February 2024).

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention. 2021 YRBS Data User’s Guide. April 2023. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/data/yrbs/pdf/2021/2021_YRBS_Data_Users_Guide_508.pdf (accessed on 20 February 2024).

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention. 2021 YRBS National, State, and District Combined Datasets User’s Guide. July 2023. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/data/yrbs/pdf/2021/2021-YRBS-SADC-Documentation508.pdf (accessed on 20 February, 2024).

- Risley C., Douglas K., Karimi M., Brumfield J., Gartrell G., Vargas R., Zhang, L. et.al. Trend in sexual risk behavior responses among high school students between Mississippi and the United States: 2001 to 2019 YRBSS. J Sch Health. 2023, 93(6), 500-507.

- Greenland S., Senn S.J., Rothman K.J., Carlin J.B., Poole C., Goodman S.N., Altman D.G. Statistical tests, P values, confidence intervals, and power: A guide to misinterpretations. Eur J Epidemiol. 2016, 31(4):337-50. [CrossRef]

- Mulla Z.D., Cole S.R. Re: "epidemiology of salmonellosis in California, 1990-1999: Morbidity, mortality, and hospitalization costs". Am J Epidemiol. 2004, 159(1):104. [CrossRef]

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Conducting Trend Analys of YRBS Data. April 2023. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/data/yrbs/pdf/2021/2021_yrbs_conducting_trend_analyses_508.pdf (accessed on 1 March 2024).

- National Cancer Institute. Available online: https://surveillance.cancer.gov/help/joinpoint/setting-parameters/method-and-parameters-tab/apc-aapc-tau-confidence-intervals (accessed on 1 March 2024).

- Xiao Y., Cerel J. Temporal trends in suicidal ideation and attempts among US adolescents by sex and race/ethnicity, 1991-2019. JAMA 2021, 4(6):e2113513. [CrossRef]

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Software for Analysis of YRBS Data. August 2020. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/data/yrbs/pdf/2019/2019_yrbs_analysis_software.pdf (accessed on 24 Jaunary 2024).

- National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA). Reported drug use among adolescents continued to hold below pre-pandemic levels in 2023. Available online: https://nida.nih.gov/news-events/news-releases/2023 (accessed on 17 May 2024).

- Volkow, N.D.; Baler, R.D.; Compton, W.M.; Weiss, S.R.B. Adverse health effects of marijuana use. New England Journal of Medicine, 2014, 370(23), 219-2227. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra1402309 (accessed on 17 May 2024).

- National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA). (2020). Health Consequences of Drug Misuse. Available online: https://nida.nih.gov/publications/research-reports/marijuana/health-effects (accessed on 15 May 2024).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Mental Health and Substance Use. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/mentalhealth/index.htm (accessed on 15 May 2024).

- Johnston, L.D.; Miech, R.A.; O'Malley, P.M.; Bachman, J.G.; Schulenberg, J. E., Patrick, M.E. Monitoring the Future National Survey results on drug use 1975-2019: Overview, key findings on adolescent drug use. Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan: 2020. Retrieved from MTF (accessed on 12 May 2024).

- Swendsen, J.; Burstein, M.; Case, B.; Conway, K.P.; Dierker, L.; He, J. P.; Merikangas, K.R. Use and abuse of alcohol and illicit drugs in US adolescents: Results of the National Comorbidity Survey–Adolescent Supplement. Archives of General Psychiatry, 2012, 69(4), 390-398. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.1503 (accessed on 17 May 2024).

- Whyte, A.J.; Torregrossa, M.M.; Barker, J.M.; Gourley, S.L. Editorial: Long-Term consequences of adolescent drug use: Evidence from pre-clinical and clinical models. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2018, 12, 83. Available online: https://doi.org/10.3389/fnbeh.2018.00083. (accessed on 12 May 2024).

- U.S. Census Bureau. Poverty Rankings 2022. U.S. Census Bureau. Available online: https://data.census.gov/ (accessed on 5 May 2024).

- US News & World Report. US News Best States 2024. US News & World Report.Available online: https://www.usnews.com/news/best-states/mississippi (accessed 5 May 2024).

- Mississippi State Department of Health. Health Equity. 2023. Mississippi State Department of Health. Available online: https://msdh.ms.gov/msdhsite/_static/44,0,236.html (accessed 6 May 2024).

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Key Substance Use and Mental Health Indicators in the United States: Results from the 2018 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. 2023. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.Available online: https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/reports/rpt42731/2022-nsduh-nnr.pdf (accessed on 6 May 2024).

- Kammer, F; The privilege of plenty: Educational inequity in Mississippi. 2019, Jesuit Social Research Institute. Loyola University. Available online: https://jsri.loyno.edu (accessed on 7 May 2024).

- Evans-Whipp, T.J.; Bond, L.; Toumbourou, J.W.; Catalano, R.F. School, parent, and student perspectives of school drug education. Health Education Research, 2018, 23(3), 507-517. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1093/her/cyn024.(accessed 8 May 2024).

- Mental Health America. Access to care data 2022. Available online: https://mhanational.org/issues/2022/mental-health-america-access-care-data (accessed 8 May 2024).

- HRSA. Overview of the State-Mississippi-2021. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Available online https://www.hrsa.gov (accessed 8 May 2024).

- Anderson, M. and Nicolaidis, C. Barriers to mental health care access in rural America. The Journal of Rural Health, 2020, 176-187. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1111/jrh.12322. (accessed 9 May 2024).

- National Institute on Drug Abuse. Monitoring the Future National Survey Results on Drug Use 1975-2020: Overview, Key Findings on Adolescent Drug Use. 2020. National Institute on Drug Abuse. Available online: https://nida.nih.gov/research-topics/trends-statistics/monitoring-future (accessed 9 May 2024).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2020 Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance — United States, 2019. MMWR Surveillance Summaries, 2020 1-83. Available online: https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.ss6901a1. (accessed 13 May 2024).

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). Substance Use and Mental Health Issues among U.S.-Born and Immigrant Hispanics. 2020 Available online: https://www.samhsa.gov/data/release/2020-national-survey-drug-use-and-health-nsduh-releases (accessed 13 May 2024).

- Fell, J.C.; Fisher, D.A.; Voas, R.B.; Blackman, K.; Tippetts, A.S. The impact of underage drinking laws on alcohol-related fatal crashes of young drivers. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 2009, 1208-1219. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1530-0277.2009.00945.x. (accessed 14 May 2024).

- Mpofu, J.J.; Underwood, J.M.; Thronton, J.E. et al. Overview and methods for the Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System – United States, 2021, 2023, MMW Suppl 2023;72 (Suppl-1):1-12. Available online: https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.su7201a1 (accessed 7 May 2024).

- Kaufman, P.; Alt, M.A.; and Chapman, C.D. Dropout rates in the United States: 2001. 2004, National Center for Education Statistics. Available online: https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2005/2005046.pdf Accessed 9 May 2024).

- Mississippi Institutions of Higher Learning. Mississippi High School Outcomes 2007. Available online: http://mississippi.edu/urc/downloads/articles/MSHighSchoolOutcomes-June2007.pdf (accessed 7 May 2024).

- Moriah. R.H.; Seo, D.C.; Evans-Polce, R.; Nguyen, I.; and Parker, M.A. Cigarette and e-cigarette use trajectories and prospective prescription psychotherapeutic drug misuse among adolescents and young adults. Addictive Behaviors 2023, 1078 Available online: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2023.107818 (accessed 9 May 2024).

- Chadi, N.; Schroeder, R.; Jensen J.W.; Levy, S. Association between electronic cigarette use and marijuana use among adolescents and young adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatrics. 2019,173(10) e192574. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.2574 (accessed 9 May 2024).

- Porter, J.J.; Hudgins, J.D.; Monuteaux, M.C.; Bourgeois, F. T. Prescription opioid use and misuse among adolescents and young adults in the United States: A national survey. 2019 PLOS Medicine. Available online: https://journals.plos.org/plosmedicine/article?id=10.1371/journal.pmed.1002922 (accessed 11 May 2024).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).