1. Introduction

The agricultural sector is one of the most important contributors to the Philippine economy as it is a critical source of employment in the country [

1].

As of 2019, 9.72 million of the total labor force of the Philippines are part of the agricultural sector [

2]. However, the nature of agricultural work is associated with physical and mental health risks with the women, the least educated, and the younger farmers more prone to mental health risks [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7]. In addition, most Filipino farmers also belong to the lower socioeconomic strata. These factors along with the existing stigma against people with mental health disorders, may contribute to the lack of access to medical care, especially those providing mental health services.

Previous studies have identified factors that are possibly associated with anxiety among farmers. However, a limited number of studies focus on the proportion of farmers with anxiety symptoms; and no previous studies have established the factors associated with anxiety symptoms pertinent among Filipino farmers, specifically in Central Luzon.

This article aims to lessen the knowledge gap regarding the mental health of Filipino farmers by determining the different factors associated with anxiety symptoms among Filipino farmers in Central Luzon. This article will determine the proportion of farmers with anxiety symptoms, identify the percentage distribution of the anxiety symptoms experienced by the Filipino farmers using the GAD-7 tool, and determine the association of different factors with the presence of anxiety symptoms.

By evaluating the symptoms of anxiety in farmers and determining the contributing factors, a foundation can be established upon which these needs can be addressed. Therefore, in the future, the study findings may be used as reference in the spread of mental health awareness to the public; as a guide for public health workers to create programs and for policymakers to facilitate in the formulation of policies and allocation of resources for to address the different issues affecting the mental health of Filipino farmers which ideally can be translated into government support either increasing farmer competitiveness or modernizing agricultural production [

8]. The mismatch between farmer’s needs and provision of services available affects their mental health and productivity [

9].

1.1. Literature Review and Theory

1.1.1. Anxiety Disorders

The proportion of the global population with anxiety disorders in 2015 was estimated to be 3.6%, while in 2017, mental health was regarded as the third most common disability in the Philippines. In fact, the Philippines ranked third for the highest prevalence rate of mental health problems in the Western Pacific Region [

10].

Anxiety was defined as multiple mental and physiological phenomena, including a person's conscious state of worry over an unwanted future event, or fear of an actual situation [

11]. Over the years, many types of anxiety disorders have been identified, with Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD) being one of the most common types. GAD is characterized by persistent, excessive, and unrealistic worry about daily matters. It is often accompanied by many non-specific psychological and physical symptoms and excessive worry is its main feature [

12]. Diagnostic criteria for anxiety disorder include (1) excessive anxiety and worry occurring more days in a week than not, for at least six months duration, (2) worry that is difficult to control, (3) anxiety or worry associated with 3 or more of the following symptoms: restlessness, easy fatigability, difficulty in concentrating, irritability, muscle tension, and sleep disturbance, (4) significant distress or impairment in social and occupational areas, (5) anxiety or worry has no other attributable causes [

13].

1.1.2. Factors Contributing to Anxiety Symptoms

The farmers, in consideration to their demographics, exposure to specific factors and nature of work, may experience anxiety symptoms. Married males experienced less psychosocial stress, anxiety, and depression as compared to their female counterparts [

14]. This is mainly due to difficulty experienced by the latter in balancing work and family and expectations brought about by the traditional family and gender roles that exists in the Philippine culture, resulting in tension and stress [

6,

15]. Educational attainment and age were also seen as a factor that is associated with anxiety and depression, wherein those who have a lower educational attainment and those younger and less experienced were more likely to experience mental health issues [

3,

4,

6,

7].

A study identified long working hours, heavy workload, extreme weather, physical health, unsafe work conditions, farm operation type, government support, and social pressure as key risk factors contributing to the increased mental health problems among farmers [

7]. Unfavorable exposure to said factors may impact their lives negatively, and one of the possible effects was anxiety. Anxiety can then cause mental exhaustion, and coupled with physical exhaustion, may lead to burnouts [

16]. In addition, these stressors were shown to cause physical symptoms such as sleep irregularities, relaxation problems, excessive fatigue, back problems, and intense headache [

17].

Farmers are exposed to long working hours, heavy workload, and unsafe work conditions, as they are found working alone or in small groups utilizing machinery that may be dangerous due to the noise level and absence of safety mechanisms [

18]. However, despite the availability of agricultural equipment to assist the farmers, heavy workload still exists today, due to an apparent decline in the agricultural labor force [

1].

Another factor causing Generalized Anxiety Disorder among farmers was the usage of pesticide [

19]. One mechanism is due to the inhibition of the acetylcholinesterase, an enzyme that breaks down the neurotransmitter acetylcholine into acetyl-CoA and choline in the neuromuscular junction. This causes accumulation of acetylcholine, causing overstimulation of neurons resulting to anxiety symptoms such as agitation and restlessness [

20].

The Philippines being an archipelagic nation, is susceptible to climate variability, wet seasons, and extreme weather events [

21]. This increased the farmers' vulnerability to mental health problems by affecting their physical health and income through heavier workload and longer working hours, causing strains and sprains. [

22,

23]. Meanwhile, in the province of Albay, 79% of farmers acknowledged extreme weather conditions as a major risk in their farming work [

24]. Wet seasons also favored the development of unsafe working conditions such as leptospirosis, malaria, and dengue which affect the physical health of the farmers working in that area [

23].

Filipino farmers were also categorized by their farm operation type. This distinction may sometimes lead to conflict in the workplace [

14]. In terms of farm ownership, most of the farmers had full ownership of the farming land, while other farmers served as tenants, have partial ownership of the land, owned the land through rent or lease [

25]. Farm operations other than full-ownership and family-ownership were more at risk of role conflicts due to presence of issues about unjust wages and task distribution which possibly resulted to psychological distress [

16].

Social pressure, particularly in terms of a work-family situation is a type of inter-role conflict defined as the difficulty experienced in the allocation of time to fulfill needs within his role in the work or the family. Inter-role conflict causes a strain in either one area causes difficulty to tend to the other, and when actions or behaviors required by one or both roles clash or otherwise make it a challenge to fulfill the needs of the other role [

26]. A high-level inter-role conflict, including family relations, has been associated with increased incidence of symptoms of depression and anxiety [

27,

28].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

The article used an analytical, cross-sectional research study design.

2.2. Study Population

The researchers chose farmers in Central Luzon (Region III) as the target population, due to its status as a major crop producer, particularly rice, and its accessibility to the researchers in terms of language.

2.3. Eligibility Criteria

Farmers who met the following inclusion criteria were eligible for participation: (1) at least 18 years of age, (2) are Filipino farmers located in Central Luzon, (3) grow crops and/or raise livestock and poultry for commercial use, (4) have been working as a farmer for at least one year, (5) with farming as their main source income, and (6) must be able to read, speak, and understand either Filipino or English language.

Meanwhile, farmers who had at least one of the following criteria, were excluded for the study: (1) have already retired from farming, and (2) have been previously diagnosed with depression, anxiety attack, and panic attack.

2.4. Sampling Method

The sample size was computed using a study by Serrano-Medina and colleagues (2019) by determining the percentage of population unexposed to pesticides that have generalized anxiety, resulting in 18%. Using this percentage, an equation by Sanchez et al, was used to compute for sample size, where n is the sample size estimate; k is the level of confidence, set to 95%, thus k = 1.96; p is the estimate of the outcome in population, computed previously to be 18%; q is 1-p; and d is the maximum amount of deviation from the frequency, set to 0.1. With these conditions, the computed sample size is 113, and accounting for a 20% non-response rate, a total of 136 participants were needed to be recruited (See equation 1 below).

Equation 1. Equation used to calculate sample size

Chain referral sampling method was used to recruit participiants, wherein contact was first initiated by the researchers, with point persons who are representatives of Local Government Units (LGU), and the researcher’s own social network within Central Luzon. Point persons were then contacted through emails, messaging platforms, and calls. The aforementioned point persons started the chain referrals and helped recruit and communicated with the potential participants until a total of 136 eligible participants were reached.

2.5. Study Variables

Table 1.

Operational Definition of Study Variables.

Table 1.

Operational Definition of Study Variables.

| Variables |

Operational Definition |

| Dependent Variable |

| Generalized Anxiety Disorder Symptoms |

Participants having a score of at least 5 in the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) screening tool. |

| Independent Variables |

| Age |

Participants at least 18 years old; 18-30 years old equates to exposure |

| Educational attainment |

Highest educational attainment of the participants; Having no formal education or having elementary level as the highest educational attainment equates to exposure |

| Sex |

Biological sex of the participant; Being female equates to exposure |

| Financial status |

The average monthly earnings of the participant in pesos in the past year and the sufficiency of their monthly earnings for their financial needs; Average monthly earning of Php 6,500 or below in the past year and insufficiency of the monthly earnings for the participants’ financial needs equate to exposure |

| Extreme Weather |

Negative impact of either typhoons and/or extreme heat on the participant’s work in the past year equates to exposure |

| Working hours |

Duration of work on most days of the week of the participants and their satisfaction towards their working hours; Dissatisfaction towards their working hours equates to exposure |

| Unsafe Work Conditions |

Perception of danger from any one of the hazards present at work equates to exposure |

| Physical health |

Presence or absence of any illness/disease and its impact on the participants’ work; Negative impact illness/disease on work equates to exposure |

| Farm operation type |

Current form of land ownership of the land the participants use for planting crops and/or raising livestock; Tenancy, employment, and others equate to exposure |

| Government support |

Perception on the sufficiency of subsidies that were received from the government in the past year; Receiving insufficient government subsidies in the past year equates to exposure |

| Social pressure |

Perception of participant that immediate family and relatives they are supporting are a responsibility, and the inability to balance work and family counts as exposure |

2.6. Data Collection Tools

2.6.1. Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7)

The GAD-7 is a seven-item anxiety scale developed by Spitzer and colleagues in 2006 used by the researchers to assess the severity of anxiety symptoms, for the past two weeks. Scoring used was mostly based on the instructional manual from Pfizer Inc. wherein the severity of each symptom was scored on a scale of 0–3, indicating: (0) not at all, (1) several days, (2) more than half of the days, (3) and nearly every day. Total scores on the GAD-7 range from 0 to 21; scores of 0-4, 5-9, 10-14, and 15-21 represent points for none, mild, moderate, and severe anxiety symptoms, respectively [

29].

However, since binary logistic regression was used for the data analysis of the results, GAD-7 score interpretation was modified by the researchers, with scores from 0-4 and 5-21 only labeled as either ‘No anxiety symptoms’ and ‘Has anxiety symptoms’, respectively.

The official English and Filipino versions were made available by Pfizer Inc. through

https://www.phqscreeners.com for download. No expenses were made to acquire this tool, and permissions were not required by the company for the download and use of the assessment tool for this research (See Figure S1 and S2 in the Supplementary Materials File).

2.6.2. Data Collection Tool for Factors Associated with Anxiety Symptoms (DCFAAS)

The DCFAAS is a 23-item researcher-constructed instrument used to collect data regarding the exposure of the participants to the different factors which served as the independent variable. Questions used were close-ended and were mostly composed of multiple-choice questions and checkbox-type questions. Questions asked in the DCFAAS were about their condition from the previous year, in order to limit recall bias.

The DCFAAS was validated through the examination of agricultural experts and Filipino linguistic experts that assessed the content, construction, and appearance of the tool. The researchers were able to recruit a total of three validators: one BS Agriculture major graduate from the University of the Philippines Los Baños, one professor from the University of Santo Tomas who teaches Filipino courses, and one BA linguistics graduate to validate DCFAAS. The questions of the DCFAAS were then refined according to the comments and feedback given by the validators.

2.7. Pre-Testing

Prior to the data collection, pre-testing of the DCFAAS was conducted by the researchers among Northern Luzon farmers. The researchers were able to recruit a total of 32 participants from Northern Luzon with 29 participants from Pangasinan, and the remaining three participants working as a farmer in Isabela. Throughout the pre-testing, no feedback from the participants regarding any difficulty in answering the Google Forms questionnaire was reported.

2.8. Data Collection Procedure and Flow

The researchers contacted people within their respective networks, who may act as the contact person in the area, to aid in looking for farmers within Central Luzon who are qualified to be our respondents. The contact persons that were contacted were from the LGUs in the area, known friends or relatives based in Central Luzon, and employees working for the Department of Agrarian Reforms. They were formally invited through emails, text messages, and platforms like Messenger. After the contact person has agreed to aid the researchers, those who opted for hard copies were sent the following documents for distribution to the participants: Formal letter of invitation for the farmers, Instructional Materials, Informed Consent Form (ICF), the Screening Tool, GAD-7 tool, and the DCFAAS for printing. Meanwhile, those who opted to respond online were given the instructional materials, formal letter of invitation for the farmers, and the link to the Google forms questionnaire which already contains the ICF, Screening Tool, DCFAAS, and the GAD-7. Each participant was given an option to answer the documents through the English language or the Filipino language. After the participants have given their consent through the ICF, their eligibility was screened using the screening tool, which was a seven-item questionnaire answerable through “Yes” or “No” questions based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Upon meeting the eligibility criteria, they were given the DCFAAS and the GAD-7. The contact persons assisted in the data gathering procedure and served as witnesses for the respondents.

At the end of the data gathering, the participants and the contact persons were given either mobile load or cash sent to their GCash account, an online payment and financial platform, as a token of appreciation for their participation. Any expenses made by the contact persons including printing, photocopying, and the delivery of documents, were compensated accordingly by the researchers.

Since this research tackled about mental health, the researchers have anticipated the risk of triggering emotional discomfort among the participants while answering the questionnaire, and as a result, gave the participants an option to skip some questions in the DCFAAS or withdraw altogether. To further address any emotional discomfort that the participants may have felt during the data gathering, the researchers formally invited mental health facilities through a letter of intent sent via email. Two mental health facilities have agreed to provide crisis hotlines that the participants may contact if they felt the need for psychological support and these were placed in the informed consent.

2.9. Data Processing and Analysis

Since the participants were given an option to skip questions, the researchers anticipated unanswered questions and respected the decision of the respondents to not answer questions they felt uncomfortable in responding. The results that were reported and analyzed were only what was available for the researchers. Participants who answered via Google forms were readily available for retrieval and were transferred to a spreadsheet, while responses from the hard copies were encoded in a separate Microsoft Excel worksheet. The accuracy and completeness of the data were ensured by the researchers before coding. The collected data was further converted into codes, as indicated in the coding manual.

Frequencies and the percentage distribution were computed using Microsoft Excel ®. Analysis on the odds ratio and binary logistic regression are conducted in IBM SPSS Statistics ®. Crude odds ratio was computed for each factor and the adjusted odds ratio accounted for confounders such as age, sex, finance, type of farmer, and education. A confidence interval of 95% was consistently used for the crude and adjusted odds ratio. Binary logistics regression was used to determine the crude and adjusted odds ratio and p-value for the factors. Computed p-values less than 0.05 were determined to be statistically significant hence, the factor is associated with anxiety symptoms. Meanwhile, p-values more than 0.05 accepted the null hypothesis indicating no association between the factor and incidence of anxiety.

3. Results

The researchers were able to recruit a total of 175 respondents, 136 (77.7%) of which satisfied the inclusion criteria and were considered eligible to participate in this research study. The valid responses from the eligible farmers were tabulated despite incomplete answers in the DCFAAS questionnaire. All valid responses were summarized in

Table 2 according to demographics.

Among the eligible farmers, 86.6% were aged more than 30 years old with a mean age of 47.6 ± 14.4, clustering between ages 48-58 years old. They were mostly male (75.0%). Highest educational attainment of farmers consists mostly of high school (43.2%) followed by college (29.5%), and elementary (25.0%).

Meanwhile,

Table 3 enumerated the occupational factors that are associated with exposure to anxiety and it determined that the amount of earnings consists mostly of farmers with less than the average monthly earnings (61.2%), with the majority (67.4%), perceived that their monthly earnings are insufficient to meet their needs. The farmers compensate for this by having other forms of income which include, but are not limited to, tricycle driving, charcoal selling, and trading other goods. More than half of the farmers (57.4%) admitted to having jobs other than farming namely, carpentry and construction; selling fruits, vegetables, and prepared food; charcoal making; tricycle and truck drivers; having job order position in the government office; having small business such as sari-sari stores; occupying political positions in the barangay level; house helpers; and part of the business process outsourcing (BPO) industry.

Majority of the farming land worked on by the participants was either solely owned (30.8%) or is owned by a landlord (39.1%). Other forms of ownership that were stated by the respondents were farm lands being lent to the respondent from family members with income percentage arrangement, and farm lands being lent to the respondent from family members without lease payment. About 87% of the farmers deny receiving government support.

Both the occurrence of strong typhoons and extreme heat conditions had negative effects on the farmers, 72.2% and 70.7%, respectively. Remarkably, 81.1% farmers were satisfied with their working hours despite the perceived danger which 65.4% of the farmers recognized. The researchers were able to provide at least five common hazards in which majority of the farmers ticked more than five of the mentioned hazards.

The presence of illness seemed to have no effect on their work as well, as 83.3% of the farmers indicated. The common illnesses stated were the following: hypertension, asthma, allergies, epilepsy, diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases. Lastly, social pressure was represented by the influence of relatives on time and energy consumption and work completion of the farmer, with 67.9% admitting to spending more time and energy to sustain their family. More than a third of the farmers (36.5%) had their work completion affected by their respective relatives.

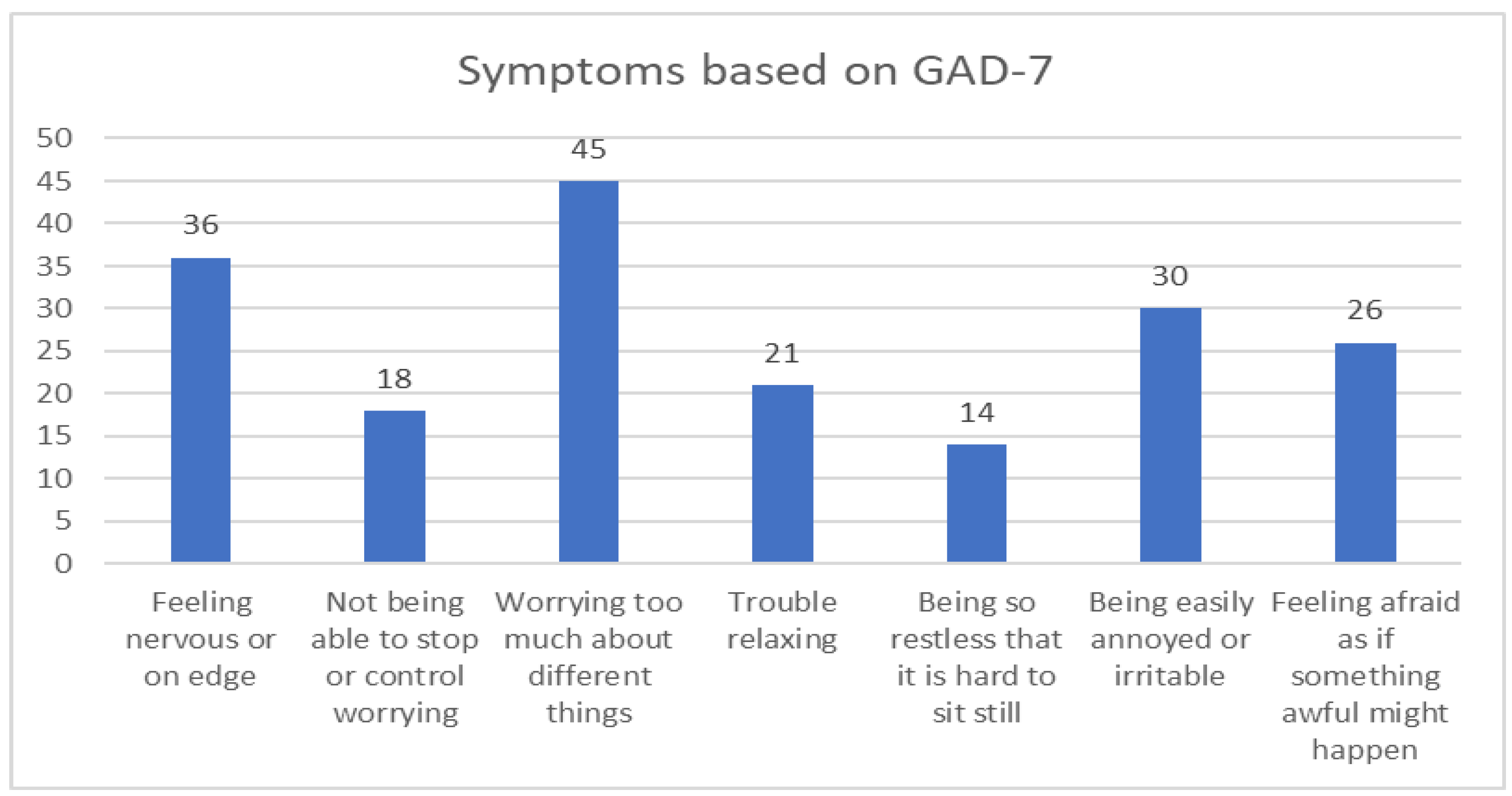

In assessing the incidence of anxiety symptoms, the researchers accounted for the number of eligible respondents who completed the GAD-7 tool where out of 136 valid responses, there were 113 respondents who answered the GAD-7 in its entirety. About 17% had experienced anxiety symptoms. This means that majority of the farmers (83.2%) had a good mental state, either free or with minimal anxiety (

Table 4). It was also determined that the most prevalent symptom among farmers was “worrying too much about different things” wherein 39.8% respondents experienced this symptom, accounting for the symptom which ticked the most. The least prevalent symptom was “being so restless that it is hard to sit still” wherein 12.4% of the farmers experienced this symptom.

Figure 1 summarizes other anxiety symptoms included in the GAD-7 tool.

Analysis based on binary logistic regression had the following findings as summarized in

Table 5. A total of 104 valid responses were analyzed as 32 of 136 valid responses failed to accomplish either/both the DCFAAS and GAD-7 questionnaires thereby excluding their responses in the analysis.

Table 5 summarizes the results wherein the factors that are significantly associated with anxiety symptoms are physical health and social pressure affecting work completion. Analysis shows that poor physical health or the presence of illness can affect work as well as increase the risk of anxiety symptoms by 10 times (OR= 10.700, 95% CI [1.367, 83.773]). There is also an increase of probability that farmers experiencing burden from relatives affecting primarily their work will have 6 times (OR=6.449, 95% CI [1.346, 30.896]) more likelihood of anxiety symptoms. Notably, those who did not receive government support had no incidence of anxiety symptoms resulting in undefined OR.

4. Discussion

This article recognized the various factors that Filipino farmers encounter in their line of work that may put them at risk of anxiety disorders. Factors such as long working hours, heavy workload, presence of unsafe working conditions, presence of physical illness, and low income were commonly known factors that increase farmers' vulnerability to mental health problems [

7]. Despite that, results showed that only 16.8% of the eligible participants experienced anxiety symptoms for the last two weeks. This may be influenced by the bias of the sampling method which was through chain referral and the small sample size. Moreover, there was a particularly small proportion of female and younger aged participants with both factors being associated with anxiety [

30].

Data was collected amidst the COVID-19 pandemic in which a similar study by Cevhar and colleagues done in 2021, assessed the presence of anxiety disorders among male Turkish farmers. All farmers experienced anxiety symptoms in varying levels of severity, based on their GAD-7 scores [

31]. However, such findings were not observed in this article, having low prevalence of anxiety symptoms. This may be explained by the presence of barriers in confiding psychological issues, namely (1) high cost of medical services, (2) lack of health insurance, (3) self-stigmatization with fear of negative judgment, embarrassment, and shame, and (4) presence of social stigma affecting family or group reputation which are prevalent among Filipinos. Moreover, Filipinos prefer confiding to religious clergies, friends, and family members over mental health professionals. These professionals are sought either as a last resort or in severe cases [

32]. Religion also plays a vital role in Filipino resilience as a local study showed religious participants having higher resilience [

33]. The Filipinos’ Christian culture, alongside the cultural values of ‘bayanihan’, ‘malasakit’, and ‘volunteerism’, may have helped the farmers overcome their anxiety symptoms by enhancing available resources [

34]. In addition, there has been a development of Climate-resilient or Climate-smart agriculture options which not only improved the Farmer’s productivity, but also their adaptivity [

35].

Worrying too much about different things was the most prevalent symptom. About 40% of the farmers experience excessive worrying which was attributed to farming season- weather, physical environment, and farm economy. Moreover, there is the risk of poverty, malnutrition, climate change and among others that farmers worry about [

36,

37]. Farming itself is also not financially rewarding as farming demands are high but income remains uncertain [

38]. Related to excessive worrying is nervousness (31.9%) followed by irritability (26.5%) which are common responses to stress. These anxiety symptoms were significantly associated with physical health having the highest odds ratio (OR) of 10.700 [1.367, 83.773]. Similar findings were observed in other studies wherein physical health was related to vulnerability to mental illness and symptoms thereof [

7,

39,

40]. Agricultural workers were reported to be prone to acute and chronic diseases making the farmers more vulnerable to mental health problems [

41]. Moreover, other factors were linked to the increased risk such as lower levels of education, older age, more than three children, and social isolation [

39]. Health problems are multifaceted that a cascade of factors will influence time-bound work [

42]. This article, however, found no significant association between insufficient earning and anxiety symptoms despite an OR of 5.374 [0.812, 35.548]. This may be due to limited access to medical facilities that farmers have poor health-seeking behaviors, prompting their earnings to be solely used for everyday needs instead of seeking medical treatment. Some of the rural farmers even prefer ‘manghihilot’ and ‘albularyo’ to tend to their health needs.

The article also determined the effects of social pressure on work completion wherein those farmers living with relatives that affect their productivity to complete their farm work were 6 times more likely to experience anxiety symptoms (OR=6.449 [1.346, 30.896]). It is not surprising that Filipinos are affected by family members considering Filipinos have a family-oriented culture. In the Philippines, it is often that family members establish family businesses therefore when problems arise, family and work get intertwined [

43]. In the Bicol region of the Philippines, the pandemic prompted the families of the abaca farmers to work in farm field and production, leading to an increased yield in the abaca [

44]. It can be deduced that working with the family will cause little to no association with respect to anxiety symptoms as family members hold stronger perceived personal social support [

45]. However, this was not observed in this research, which may be explained by the easing transition to pre-pandemic, opting some members to return to their previous jobs or find work that they like. Other studies also show that decision-making involvement of other family members causes stress and leads to more serious consequences especially for those who are living in more than one-generation families. This is aggravated by financial issues which often result in familial conflict [

45,

46]. The spillover effect of both family and work stressors will affect farming productivity. This shifts the attitudes and stresses within the family which may negatively impact the person's well-being and inevitably their work as well [

42].

Other factors that several studies determined to influence anxiety symptoms were shown to be not as significant among Filipino farmers. One article stated that low levels of household income were more associated with mental disorders, with a decrease in income indicating a higher risk in anxiety [

47]. However, this was not observed in this article where lower than average income had no substantial association on anxiety symptoms. Another noteworthy factor was extreme weather conditions, specifically typhoons which the Philippines frequently experienced. However, despite a significant adjusted OR of 9.533 [0.477, 190.578], it was determined to be not statistically significant to cause anxiety symptoms. A greater sampling size would elucidate the reliability of the results.

4.1. Limitations and Future Directions

Limitations on the sampling size and the sampling method resulted in a wide range of confidence intervals that decreased the precision of the results. The DCFAAS questionnaire was constructed by the researchers and the indicated exposure factors were based on the limited literature on Filipino farmers and their mental health. Further studies and validation must be done to properly assess reliability of the DCFAAS questionnaire. On the other hand, the GAD-7 questionnaire only accounted for anxiety symptoms that were experienced for the past two weeks. This can be improved by adding more questions per factor or using a stress scale and other forms of established assessment tool that can assess anxiety along with the use of the DCFAAS questionnaire to better measure the association of each factor. Inclusion of a psychiatrist or psychologist as experts will also help in assessing the farmers, validating the results, and providing technical expertise in dealing with farmers with mental health problems.

The researchers also acknowledge that a longitudinal study design may be a better study design in testing and establishing the association of the different factors being proposed in this manuscript as compared to a cross-sectional design because of its longer timeframe and multiple assessments points over time. However, due to the limited timeframe given for this research study, the limited resources available to the researchers, and the imposed travel restrictions brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic, the researchers perceived cross-sectional study design as the more fitting study design.

Our research is limited only to Central Luzon farmers, therefore further studies may widen the geographical scope and include other farmers across the country. There are factors involved that are unique to an area such as culture, situations such as armed conflict, and among others. Furthermore, the pandemic restricted onsite data collection hence, the researchers relied on point persons, specifically Agricultural Officers, to aid in the data collection. Travel restrictions limited the interaction of the researchers to the farmers nevertheless, it is recommended that real time interviews be conducted onsite or over the phone.

5. Conclusions

The findings of this research can be helpful not only for the farmers, but for the local governments units (LGUs) and lawmakers handling the welfare of Filipino farmers in creating policies and programs that cater to the farmer’s well-being. Furthermore, this article is pivotal in furthering research to be conducted on Filipino farmers which are less studied in an agricultural country like the Philippines.

Despite having limited literature that tackle the different factors associated with mental health disorders among Filipino farmers, the researchers were able to determine thru this research study that the most significant factors were the presence of physical illness which impact farming work and having relatives that impact work completion in their farming work. Therefore, local government units and policymakers should focus on creating policies with the coordination of the Department of Health (DOH) addressing problems related to the farmer’s physical and mental well-being as well as provide support and additional benefits for the farmers and their family members. In addition, special attention should be given to farmers located in far-flung areas by providing better means of accessibility to medical facilities and health insurance for the farmers.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, led by Dina Marie Yalong with contribution from all authors; methodology, all authors were able to contribute to the conceptualization of the methodology; coding manual and software, William M. Manengyao, Merimae S. Villamayor, and Peter Verona G. Villangca; validation, Van Irish S. Ventilacion and Har-li T. Young; formal analysis, Vinace S. Guingguing and Merimae S. Villamayor; investigation, Vinace S. Guingguing, Van Irish S. Ventilacion, Peter G. Villangca, Dina Marie Yalong, and Har-li T. Young, ; resources, Ma. Beatrice M. Vega; data curation, Merimae S. Villamayor and Har-li T. Young; writing—original draft preparation, Abstract, William M. Manengyao, Jr. and Peter Verona G. Villangca, Introduction, Peter G. Villangca and Alina Marea C. Zaño, Methodology Vinace S. Guingguing, Dina Marie Yalong, and Har-li T. Young, Results Vinace S. Guingguing, Van Irish S. Ventilacion, and Merimae S. Villamayor, Discussion all authors, Conclusion Van Irish S. Ventilacion; writing—review and editing, Vinace S. Guingguing and Har-li T. Young; visualization, Ma. Beatrice M. Vega, Dina Marie Yalong, and Alina Marea C. Zaño; supervision, Maria Teresa S. Tolosa; project administration, Van Irish S. Ventilacion and Har-li T. Young; funding acquisition, Ma. Beatrice M. Vega. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding and The APC was funded by St. Luke’s Medical Center College of Medicine – William H. Quasha Memorial.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Ethics Review Committee (IERC) of St. Luke’s Medical Center with reference number of SL-21237, approved last October 30, 2021.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study, prior to data collection.

Acknowledgments

The completion of this research would not be possible without the participation and guidance of the people who assisted us in this research. We would like to express our deepest gratitude and appreciation to the following: To the Preventive and Community Medicine department, especially to Doctor Edmyr Macabulos for helping us gather potential contact people, and Doctor Lucila Perez for signing our required documents as soon as possible. To Assistant Professor Ma. Lanie Vergara, MAT, Aljohn Garcia, and Kriziel Dela Rosa, for validating the DCFAAS questionnaires. To our partner mental health institutions, In Touch Community Services Inc. and Mariveles Mental Wellness and General Hospital, who supported us by providing a free avenue for the farmers to contact. To our contact people, namely: Marilyn Yalong, Dennis Felipe, Dennis Tagupa, Aljohn Garcia, Marielle Tagupa, Engr. Nenita Palomo, and Arlene Infante who assisted in gathering the participants. To our statistician, Rossjyn Fallorina and Gerard Ompad, who helped us with the interpretation of results. To St. Luke's College of Medicine, for their considerate endorsement of our research. To our relatives and friends, who helped us in their own way, we thank you and appreciate you.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- Philippine Statistics Authority. "2020 Selected Statistics on Agriculture.". 2020. Available online: https://psa.gov.ph/sites/default/files/2_SSA2020_final_signed.pdf (accessed on 19 April 2021).

- Philippine Statistics Authority. "2015-2019 Livestock and Poultry Statistics of the Philippines.". 2019. Available online: https://psa.gov.ph/sites/default/files/L_P%20stat%20of%20the%20Phil_signed.pdf (accessed on 19 April 2021).

- Bjelland, I.; Krokstad, S.; Mykletun, A.; Dahl, A.; Tell, G.; Tambs, K.; Does a higher educational level protect against anxiety and depression? The HUNT Study. Social Science & Medicine. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18234406/ (accessed on 8 May 2021).

- Briones, R.M. Characterization of Agricultural Workers in the Philippines. Philippine Institute of Developmental Studies, 2017. Available online: https://pidswebs.pids.gov.ph/CDN/PUBLICATIONS/pidsdps1731.pdf (accessed on 19 April 2021).

- Lee, H.; Cho, S.Y.; Kim, J.S.; Yoon, S.Y.; Kim, B.I.; An, J.M.; & Kim, K.B.; & Kim, K. B. Difference in health status of Korean farmers according to gender. Ann. Occup. Environ. Med. 2019, 31, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- McGregor, M.; Willock, J.; Deary, I.; Farmer Stress. Farm Management 1995. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/255687364_Farmer_stress (accessed on 19 April 2021).

- Rudolphi, J.M.; Berg, R.L.; Parsaik, A.; Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Among Young Farmers and Ranchers: A Pilot Study. Community Mental Health Journal 2019. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10597-019-00480-y (accessed on 19 April 2021).

- Balié, J.; Valera, H. Domestic and International Impacts of the Rice Trade Policy Reform in the Philippines. 2020. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0306919220300786 (accessed on 19 April 2021).

- Nuvey, F.S.; Kreppel, K.; Nortey, P.A.; Addo-Lartey, A.; Sarfo, B.; Fokou, G.; Ameme, D.K.; Kenu, E.; Sackey, S.; Addo, K.K.; Afari, E.; Chibanda, D.; Bonfoh, B. Poor Mental Health of Livestock Farmers in Africa: A Mixed Methods Case Study from Ghana. BMC Public Health, BioMed Central, 2020. Available online: https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12889-020-08949-2 (accessed on 15 July 2021).

- World Health Organization (WHO). Mental Health Atlas. 2018. Available online: https://www.who.int/mental_health/evidence/atlas/mental_health_atlas_2017/en/ (accessed on 19 April 2021).

- Evans, D.L.; Foa, E.B.; Gur, R.E.; Hendin, H.; O'Brien, C.P.; Seligman, M.E. P.; Walsh, B.; Treating and Preventing Adolescent Mental Health Disorders. Oxford Medicine Online. 2012. Available online: https://oxfordmedicine.com/view/10.1093/9780195173642.001.0001/med-9780195173642 (accessed on 15 July 2021).

- Munir, S.; Takov, V.; Generalized Anxiety Disorder. StatPearls. March 2021. Retrieved 15 July, 2021. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2021 Jan-. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441870/ (accessed on 15 July 2021).

- American Psychiatric Association (APA). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition. 2013. Available online: http://repository.poltekkes-kaltim.ac.id/657/1/Diagnostic%20and%20statistical%20manual%20of%20mental%20disorders%20_%20DSM-5%20%28%20PDFDrive.com%20%29.pdf (accessed on 19 April 2021).

- Ambong, R.; Gonzalez, A. Influencing Factors and Stress Coping Mechanisms in Agricultural Communities of Occidental Mindoro, Philippines. AJHSSR 2019, 3, 194–200. [Google Scholar]

- Marks, J.; Bun, L.; McHale, S. Family Patterns of Gender Role Attitudes. Sex Roles 2009, 61, 221–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazd, SD.; Wheeler, SA.; Zuo, A. Key Risk Factors Affecting Farmers’ Mental Health: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olowogbon, T.S.; Yoder, A.M.; Fakayode, S.B.; Falola, A.O. Agricultural Stressors: Identification, Causes and Perceived Effects Among Nigerian Crop Farmers. J. Agromedicine 2019, 24, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agricultural Machinery Testing and Evaluation Center (AMTEC). Hazards of Agricultural Machinery Used in the Philippines. College of Engineering and Agro-industrial Technology, University of the Philippines - Los Baños. 2012. Available online: http://www.unapcaem.org/Activities%20Files/A1205_AS/PPT/ph01.pdf (accessed on 19 April 2021).

- Serrano-Medina, A.; Ugalde-Lizárraga, A.; Bojorquez-Cuevas, M.; Garnica-Ruiz, J.; González-Corral, M.A.; García-Ledezma, A.; Pineda-García, G.; Cornejo-Bravo, J. Neuropsychiatric Disorders in Farmers Associated with Organophosphorus Pesticide Exposure in a Rural Village of Northwest México. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mamuya, S.; Mwabulambo, S.; Mrema, E.; Ngowi, A. Health Symptoms Associated with Pesticide Exposure among Flower and Onion Pesticide Applicators in the Arusha Region. 2018. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30835378/ (accessed on 19 April 2021).

- Yumul, G.P. J.; Cruz, N.A.; Servando, N.T.; Dimalanta, C.B.; Extreme Weather Events and Related Disasters in the Philippines, 2004-08: A Sign of What Climate Change Will Mean? National Institute of Health. U.S. National Library of Medicine. 2010. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21073508/. (accessed on 19 April 2021).

- Berry, H.L.; Hogan, A.; Owen, J.; Rickwood, D.; Fragar, L. Climate Change and Farmers’ Mental Health: Risks and Responses. Asia Pacific Journal of Public Health 2011, 23 (Suppl. 2), S119–S132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Health (DOH). Prepare for the Rainy Season - DOH. 2019. Available online: https://doh.gov.ph/node/17435#:~:text=The%20common%20diseases%20during%20the,such%20as%20malaria%20and%20dengue (accessed on 19 April 2021).

- Peria, A.S.; Pulhin, J.M.; Tapia, M.A.; Predo, C.D.; Peras, R.J. J.; Evangelista, R.J. P.; Lasco, R.; Pulhin, F.; Knowledge, Risk Attitudes and Perceptions on Extreme Weather Events of Smallholder Farmers in Ligao City, Albany, Bicol, Philippines. UPLB Journals Online 2016. Available online: https://journals.uplb.edu.ph/index.php/JESAM/article/view/1545/pdf_53 (accessed on 19 April 2021).

- Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA). Special Report - Highlights of the 2012 Census of Agriculture (2012 CA). Available online: https://psa.gov.ph/content/special-report-highlights-2012-census-agriculture-2012-ca# (accessed on 8 May 2021).

- Zhang, Y.; Duffy, J.; De Castillero, E. Do sleep disturbances mediate the association between work-family conflict and depressive symptoms among nurses? A cross-sectional study. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, H.; Fonseca, A.; Caiado, B.; Canvarro, M. Work-Family Conflict and Mindful Parenting: The Mediating Role of Parental Psychopathology Symptoms and Parenting Stress in a Sample of Portuguese Employed Parents. Front Psychol. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaRocca, E.; The Correlation between Personal Stressors, Anxiety and Caffeine Consumption among JMU Faculty. James Madison University 2020. Available online: https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1009&context=honors202029 (accessed on 8 May 2021).

- Spitzer, R.L.; Korenke, K.; Williams, J.B. W.; Löwe, B. A Brief Measure for Assessing Generalized Anxiety Disorder: The GAD-7. Arch. Intern. Med. 2006, 166, 1092–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flores, J.L.; Hernandez, M.A.; Leyva, E.W.; Cacciatia, M.; Tuazon, J.; Evangelista, L.; Prevalence and correlates of depression, anxiety, and distress among Filipinos from low-income communities in the Philippines. Philippine J. Nurs. 2018. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8088195/ (accessed on 28 May, 2022).

- Cevhar, C.; Altunakaynak, B.; Gürü, M. Impacts of COVID-19 on Agricultural Production Branches: An Investigation of Anxiety Disorders among Farmers. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5186. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/13/9/5186/htm (accessed on 28 May 2022). [CrossRef]

- Martinez, A.B.; Co, M.; Lau, J.; Brown, J.S. Filipino Help-Seeking for Mental Health Problems and Associated Barriers and Facilitators: A Systematic Review. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2020, 55, 1397–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Callueng, C.; Aruta, J.J. B. R.; Antazo, B.G.; Briones-Diato, A. Measurement and Antecedents of National Resilience in Filipino Adults During Coronavirus Crisis. J. Community Psychol. 2020, 48, 2608–2624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isidro, M.Q. Y.; Calleja, M.T. How do national values contribute to perceived organizational resilience and employee resilience in times of disaster? An example from the Philippines. Asian J. Soc. Psychol. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Chandra, A.; Dargusch, P.; McNamara, K.E.; Caspe, A.M.; Dalabajan, D. A Study of Climate-Smart Farming Practices and Climate-resiliency Field Schools in Mindanao, the Philippines. World Dev. 2017, 98, 214–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torske, M.; Hilt, B.; Glasscock, D.; Lundqvist, P.; Krokstad, S. Anxiety and Depression Symptoms Among Farmers: The HUNT Study, Norway. J. Agromed. 2015, 21, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lubang, S.A.; Towards Liberation from Debts of Filipino Farmers. FFTC Agric. Policy Platform (FFTC-AP) 2020. Available online: https://ap.fftc.org.tw/article/643 (accessed on 28 May 2022).

- Palis, F.; Aging Filipino Rice Farmers and Their Aspirations for Their Children. Phil. J. Sci. 2020. Available online: https://philjournalsci.dost.gov.ph/images/pdf/pjs_pdf/vol149no2/aging_Filipino_rice_farmers_.pdf (accessed on 28 May 2022).

- Çakmur, H. Health Risks Faced by Turkish Agricultural Workers. Scient. Scient. World J. 2014. [CrossRef]

- Kallioniemi, M.K.; Simola, A.J. K.; Kymäläinen, H.-R.; Vesala, H.T.; Louhelainen, J.K. Mental Symptoms among Finnish Farm Entrepreneurs. Ann. Agric. Environ. Med. 2009; (accessed on 28 May 2022). [Google Scholar]

- Lee, W.J.; Cha, E.S.; Moon, E.K. Disease Prevalence and Mortality Among Agricultural Workers in Korea. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bialowolski, P.; McNeely, E.; VanderWeele, T.J.; Weziak-Bialowolska, D. Ill Health and Distraction at Work: Costs and Drivers for Productivity. PLoS ONE, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, B.; Farm Family Stressors: Private Problems, Public Issue. Nat. Counc. Fam. Relat. 2019. Available online: https://www.ncfr.org/sites/default/files/2019-09/Fall2019ExecSum.pdf (accessed on 28 May 2022).

- Conde, M.; For Philippine Farmers Reeling from Disasters, Lockdown Is Another Pain Point. Mongabay Environ. News 2020. Available online: https://news.mongabay.com/2020/05/for-philippine-farmers-reeling-from-disasters-lockdown-is-another-pain-point/ (accessed on 28 May 2022).

- Ortega, R.L.; Hechanova, M.R. M.; Work-Family Conflict, Stress, and Satisfaction among Dual-Earning Couples. Philippine Soc. Sci. Council 2010. Available online: https://www.pssc.org.ph/wp-content/pssc-archives/Philippine%20Journal%20of%20Psychology/2010/Num%201/04_Work-Family%20Conflicts_Stress%20and%20Satisfaction%20among%20Dual-Earning%20Couples.pdf (accessed on 27 May 2022).

- Weigel, D.J.; Weigel, R.R. Family Satisfaction in Two-Generation Farm Families: The Role of Stress and Resources. JSTOR 2015. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/585227 (accessed on 28 May 2022).

- Sareen, J.; Afifi, T.; McMillan, K.; Asmundson, G. Relationship between Household Income and Mental Disorders: Findings from a Population-Based Longitudinal Study. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2011. Retrieved from https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamapsychiatry/fullarticle/211213. (accessed 28 May, 2022).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).