1. Introduction

Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) is a hexadentate ligand able to stably bind metal ions, including calcium [

1] (pp. 632-635). Because of this phenomenon aqueous EDTA solutions were introduced into endodontics by Nygaard-Ostby in 1957 to help clean dentin and widen root canals [

2]. The use of EDTA chelating gels was originally actively advocated by manufacturers of rotary instrumentation for lubrication during root canal preparation with their products [

3]. However, when EDTA gels, rather than liquids, are used during rotary canal preparation, increased torsional loads were observed [

4]. Due to this adverse mechanical effect, chelating gel usage is limited to hand instrumentation. Today, chelating gels find use in canal negotiation during the early stages of root canal preparation where they help prevent the formation of tissue plugs [

5] (p. 294), [

6] (pp. 133-167). Chelating gels also assist in debris and smear layer removal and have a lower risk of extrusion compared to EDTA solutions [

7].

Surveys concerning endodontic irrigation frequently include questions about EDTA chelation. A 2012 survey of American Association of Endodontists members reported that 77% of respondents routinely tried to remove the smear layer, and although 80% used EDTA as an irrigant, the role of a chelating gel was not mentioned [

8]. Similarly, a recent irrigation survey in the UK and Ireland reported EDTA usage, but not specifically of EDTA gels [

9]. In 2014, a US survey of general dentists stated that that 73% aimed for smear layer removal, and that 83% used a gel chelator/lubricant. Again, details of the gels were not reported [

10]. A recent Russian survey found that while only 23% used EDTA as a gel, this fraction increased to almost half amongst dentists in government run clinics [

11].

Little is known about the reasons why clinicians use a chelating gel, which groups of practitioners incorporate a chelating gel into non-surgical root canal preparation, and if they are satisfied with the characteristics of the gel they use. Indeed, to the best of our knowledge there has not been a survey focused on chelation gels. Therefore, the aim of the current research was to survey the membership of the Australian Society of Endodontology (ASE) on their usage of chelation gels. The ASE is a group comprised of endodontists, general dentists, Doctor of Clinical Dentistry (DClinDent) students in endodontics (endodontic residents) as well as a small number of other students and veterinary dental practitioners. This survey sought not only to examine differences between various groups of clinicians, but also to determine attitudes and barriers to gel usage, why practitioners use them and if the characteristics of the gel they use were satisfactory. The null hypothesis was that all types of ASE members would use chelation gels to the same extent.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Survey Administration and Design

The survey was predominantly administered via the online platform Qualtrics. Three emails with the same questionnaire link were sent to all 395 members of the ASE from July to November 2021. Paper copies were also distributed in the first half of 2022, at state meetings and during a federal conference, to ASE members who had not previously responded.

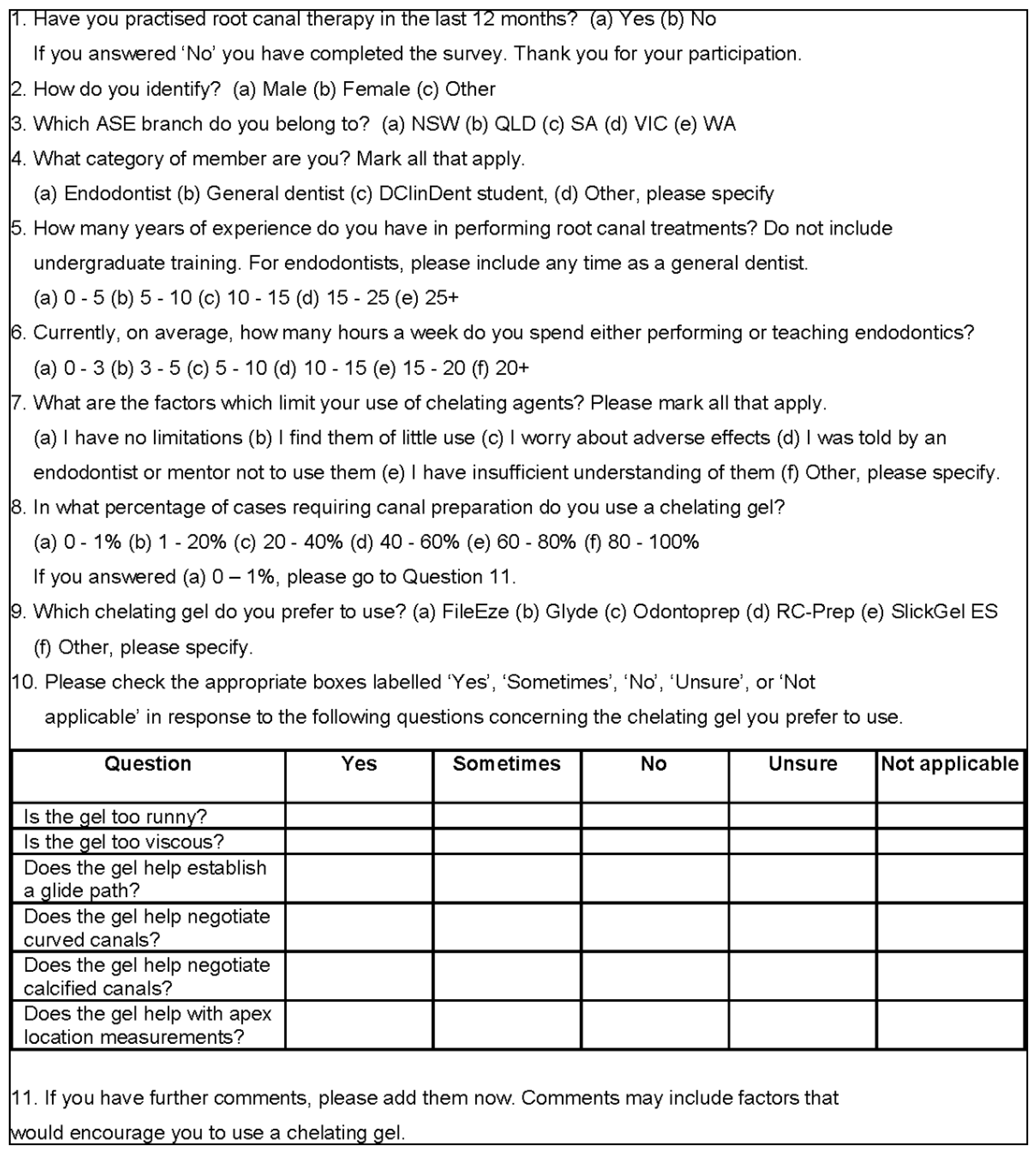

The survey consisted of 11 questions. Skip logic was incorporated into the design to direct participants to the next appropriate question. Question 1 concerned currency of endodontic practice, while Questions 2-4 centered on demographics concerning gender, the Australian state of ASE membership, and type of practice (specialist, endodontist, or endodontic resident). Questions 5-6 related to endodontic experience, while Question 7 enquired about limitations on chelator usage. Question 8 asked about the percentage of cases where a chelation gel was used. For those who used a gel, Question 9 asked which gel the participant used, followed by a grid question on participant satisfaction with the properties of that particular gel. The final question sought any further comments. The survey had an expected response time of 9 minutes. The survey questions are reproduced in

Figure 1.

2.2. Statistical Analysis

Sample size calculations were made using a 5% margin of error, a 95% confidence level, and a recommended maximal variance of 0.25 [

12]. A sample size of 195 was representative of the target population under these conditions. For a 6% margin of error, 160 responses were required. Prism 10.0.3 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA) was employed for the graphics. Cross-tabulations and chi square tests were performed in IBM SPSS Statistics 29.0.0.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). P values of the cross tabulated data were calculated using a published approach for the analysis of contingency tables [

13]. This was achieved by squaring the adjusted residuals (z scores) for each cell to convert them into chi square values. These were then transformed into P values using the Sig.Chisq function in SPSS. The Bonferroni correction was applied to a P value 0.05 to obtain an adjusted value of 0.0083 for a table of 6 cells.

3. Results

3.1. Reponse

A response rate of 181/395 (46%) was recorded. It corresponded to a 95% confidence level and variance of 0.25. A margin of error of 5.3% was calculated by previously reported methods [

12]. This was deemed to be an acceptable sample of the ASE membership. Not all ASE members currently practise, and four respondents had not performed root canal treatments in the previous 12 months. These members were not elligible to advance further in the survey. Additionally, three surveys were not included because of a lack of response clarity. This is explained in detail below. The remaining 174 questionnaires were analyzed.

3.2. Respondent Demographics

Of the respondents, 74% were male and the remainder were female. State affiliations were, New South Wales, 26%, Queensland, 39%, South Australia, 10%, Victoria, 21% and Western Australia, 5%.

3.3. Practising Characteristics

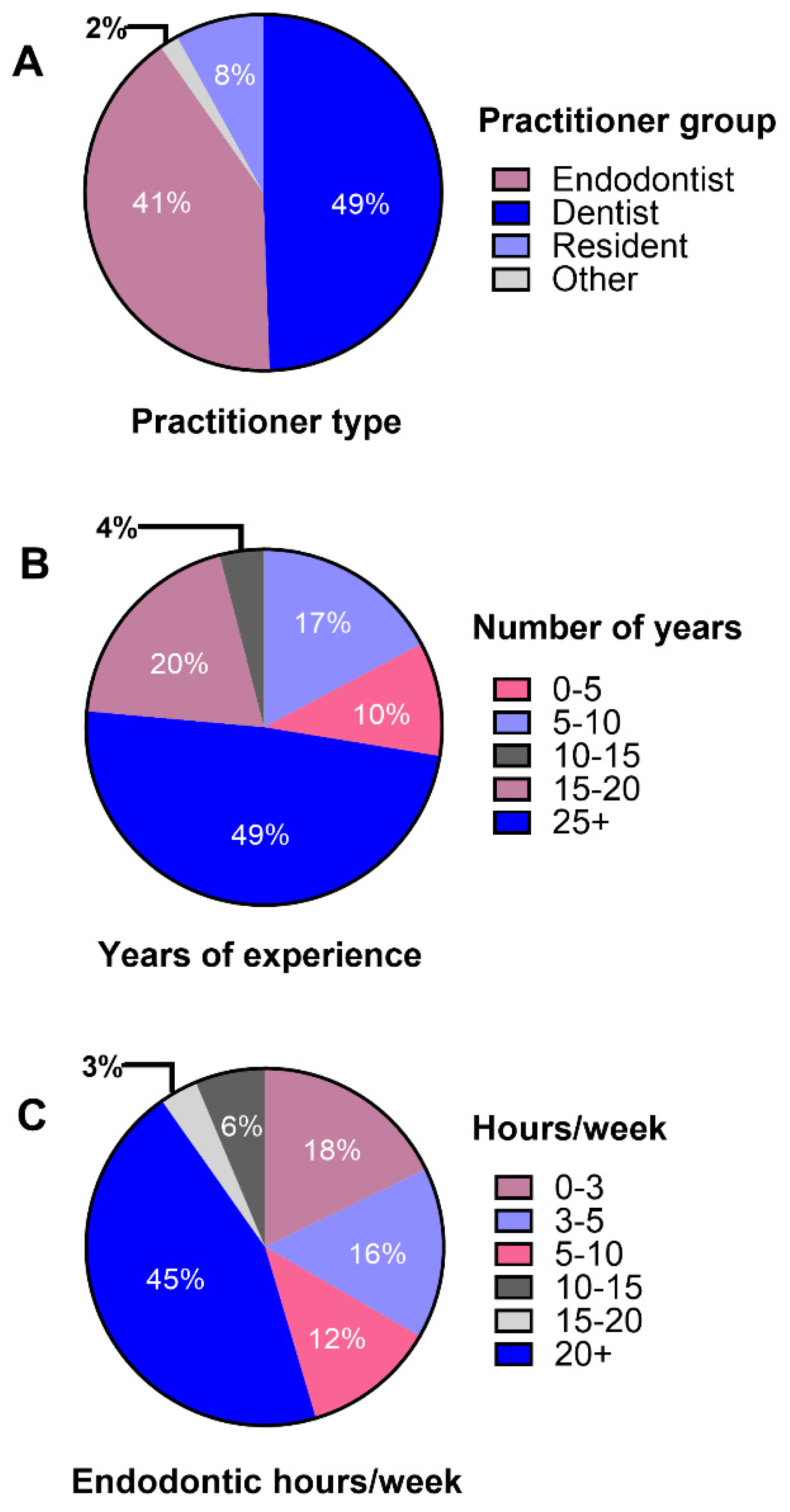

Clinician practising characteristics, including practitioner type, years of endodontic experience and hours worked in endodontics/week are presented in

Figure 2. The largest number of responses were from general dentists at 49%, while endodontists accounted for 41% of the sample. A large number of clinicians had practiced endodontics for over 25 years, with 49% of respondents in this group. A total of 45% spent more than 20 hours/week either practicing or teaching endodontics.

3.4. Chelating Gel Usage

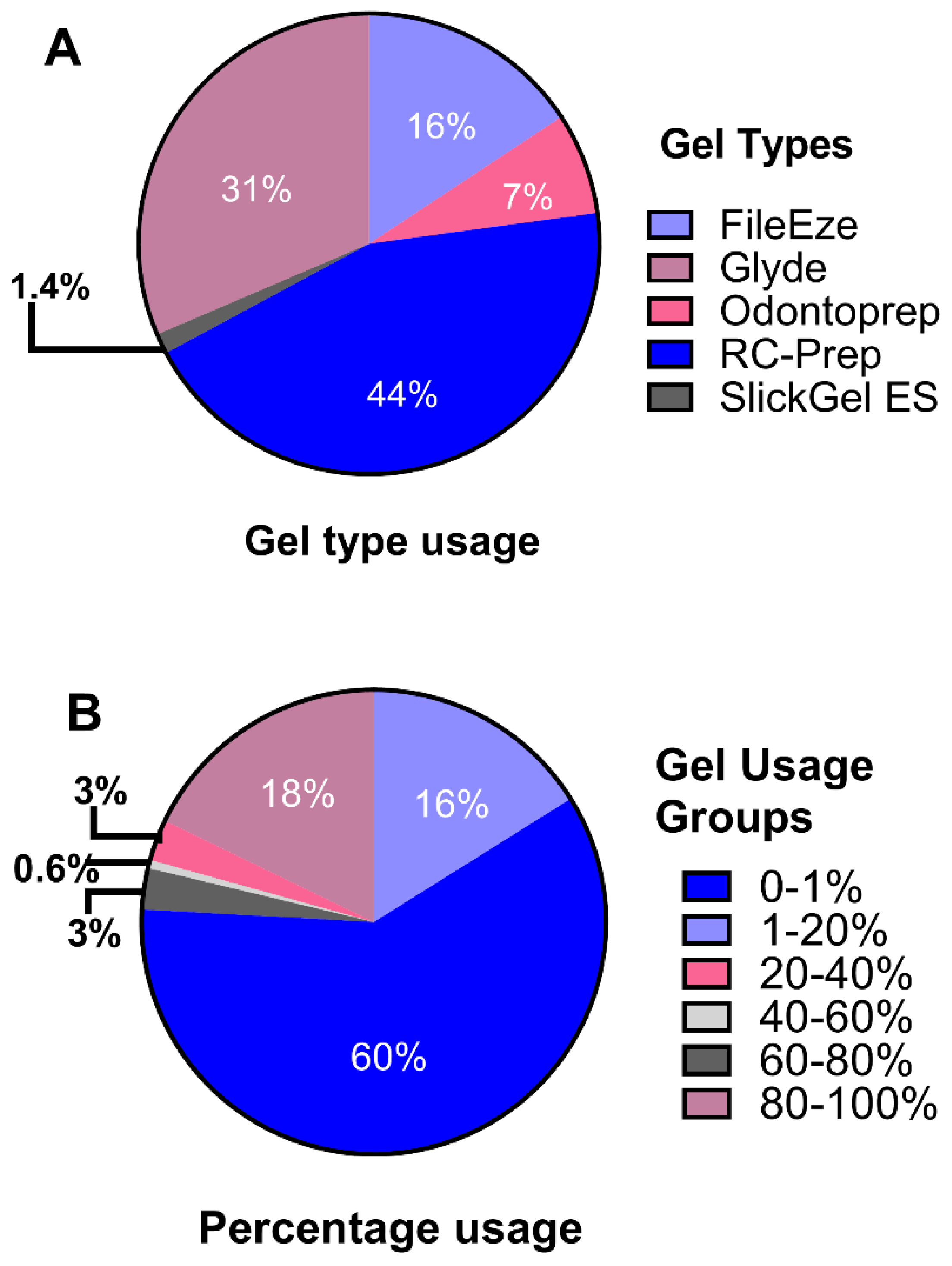

Of the 70 responses naming the chelating gel used, the most popular gel was RC-Prep

®. It was employed by 44% of gel users, followed by Glyde™ at 31% (

Figure 3). A majority of respondents, 60%, used a chelating gel in 0-1 % of cases (none or extremely rare usage). At the other extreme, 18% used a gel for 80-100% of root canal treatments (

Figure 3). The response to this question was validated by reconciling the name of the chelating gel with the comments supplied. It was obvious that some respondents had misinterpreted the question on gel usage because a high case usage percentage was indicated, but no gel name was given. Instead, they named a chelating liquid such as EDTA-C, and/or they commented that that they used liquid EDTA and not a gel. In 17 cases where the percentage chosen was inconsistent with the written text, the percentage was adjusted, in line with the comments provided. There were three responses where it was not possible to determine if a gel, liquid or neither was used. In theses cases, the survey responses were not included for any question. All instances of data cleaning were annoatated in a excel spreadsheet, and uploaded to UQ eSpace. The link for the spreadsheet is provided in the data availability statement of this article.

3.5. Chelaing Gel Usage Patterns

Gel usage percentages were cross tabulated with all practitioner categories (

Table 1.A). A high percentage of endodontists and endodontic residents, 75% and 86% respectively, belonged to the 0-1% usage group, with general dentists scoring lower, at 45%. A chi square analysis was performed on the cross-tabulation of endodontists and general dentists with 0-1%, combined 1-80%, and 80-100% usage categories (

Table 1.B). Significant differences were recorded between these two clinician groups in the 0-1% and the 1-80% usage categories, with an adjusted P < 0.0083. A further cross-tabulation compared older practitioners, with more than 25 years of endodontic experience, to all other practitioner experience groups for the 0-1%, combined 1-80%, and 80-100% usage categories (

Table 2). Older practitioners, irrespective of clinician group, were more likely to frequently use a chelating gel, recording significantly higher percentages in the 80-100% group (P < 0.0083).

3.6. Limitations on the Use of Chelating Agents

The question concerning the limitations in the use of chelating agents allowed multiple responses. While just 1% of clinicians worried about adverse effects, and 3% had insufficient knowledge of chelating agents, 65% had no limitations on use. A total of 6% of clinicians had been told not to use chelating agents and 22% found them of little use. The remaining respondents provided a comment on their limitations. Only one clinician specifically mentioned being limited by the concern that the chemical disinfectant properties of sodium hypochlorite would be diminished when in contact with EDTA.

3.7. Satisfaction with Gel Properties and Usefulness

All percentages in this section refer only to those practitioners who used a gel. While 12% found that the gel they used was sometimes too runny, 30% answered that their gel was too viscous, with most replying that this was only sometimes the case. The most commonly named viscous gel was RC-Prep, although one clinician commented that this could be overcome by warming the gel beforehand on a gloved hand. A majority of gel users, 74%, found that a chelating gel was useful for establishing a glide path. A total of 56% said that a gel helped negotiate curved canals, with a little over half of these replying that this was only sometimes the case. Additionally, 62% found gels assisted in the negotiation of calcified canals. For the question about the usefulness of chelating agents in apex location, 46% replied that it was of no assistance, while only 4% replied that yes, it helped, and 13% responded that it assisted sometimes. A further 23% were unsure of this this question and 14% found the question was not applicable.

3.8. Comments

Several comments were received from clinicians who reported a 0-1% gel usage, and who were ineligible to answer the grid question concerning gel satisfaction and usefulness. Many in this category commented that they saw no benefit to using a gel over a liquid. Some further explained that their instrumentation was able to deal with the preparation of fine canals, that there was no scientific evidence to support the use of a gel or that liquids penetrated the dentin better.

Adverse effects were also provided. These included the increased risk of rotary instrument fracture, the accumulation of debris, increased friction, or that a waxy smear layer was left on dentin following gel usage. One respondent further added that a gel needed to be water soluble to avoid the deposition of material on the canal wall. Another commented that they found the apical area harder to clean in the presence of a gel.

4. Discussion

The null hypothesis was rejected because ASE member categories showed different chelating gel usage patterns. The ASE is a varied group of clinicians with a particular interest in the practice of endodontics. Thus, a survey of its members provides an opportunity to obtain insights into the differential use of chelating gels.

Of the ASE membership, 60% do not, or extremely rarely, use a chelating gel during root canal preparation. According to the chi square test, this result is attributable to the endodontist component of the membership, while the general dentist component had significantly lower gel usage.

Table 1.A shows that endodontic residents also had low gel usage. One of the stipulations of the chi square test is that no cell contains a zero and that less than 20% of cells have expected numbers under 5 [

14] (pp.148-176). For this reason, in

Table 1.B, the resident component of the membership was not included in the chi square test, and the usage categories, 1-20%, 20-40%, 40-60% and 60-80% were combined [

14] (pp.148-176). Similarly in

Table 2, in the analysis of clinicians’ experience levels, both gel usage and age group categories were combined.

Clinicians who use chelating gels are generally satisfied with the physical properties of the gel they use, and find them advantageous for creating a glide path in fine or curved canals. While particular manufacturers claim that their gel assists in the reliable use of apex locators [

15], few gel users agreed with this statement. Indeed, there seems to be no scientific evidence to substantiate this claim. However, chelators in general can provide the ions needed for the conductance required for an apex locator to function well [

6] (pp. 133-167).

NaOCl is a strong oxidizing agent and the rapid decrease in its concentration in the presence of EDTA is well documented in the literature [

16,

17,

18]. In the question on the limitations of chelating agents, only 1% of respondents were concerned about adverse effects, and one respondent specified the depletion of NaOCl in the presence of EDTA. Indeed, in their material safety data sheets, gel manufacturers recommend that their product be kept away from oxidizing agents [

19,

20], yet some promote the effervescence that occurs [

21].

One limitation of this survey was that, as mentioned, some participants misinterpreted the gel usage question. However, the changes detailed likely largely compensated for this. A further limitation is that gel usage patterns could be dissimilar in various countries. A 2014 survey showed that 83% of general dentists in the United States used a chelating gel [

10], but this figure was only 55% amongst ASE general dentists. In Russia, gel usage among endodontists and general dentists combined was only 23%, although how the two groups of clinicians contributed to this was not reported. Irrespective of absolute usage values, it would be informative to investigate if the same differential patterns involving practitioner type and experience are observed in other countries. Such an analysis may indicate trends in gel usage.

5. Conclusions

Chelating gel usage amongst ASE members depends on practitioner category and years of endodontic experience. Many who did not use a gel found little benefit of a gel over a liquid chelator, while gel users said that a gel helped them negotiate fine or curved canals. Because older practitioners have higher gel usage, it is possible that the use of chelating gels by ASE members will diminish over time.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, O.A.P. and P.P.W.; methodology, P.P.W. and E.S.D.; formal analysis, P.P.W. and E.S.D.; resources, O.A.P.; data curation, P.P.W., O.A.P. and E.S.D.; writing—original draft preparation, P.P.W.; writing—review and editing, P.P.W., O.A.P. and E.S.D.; supervision, O.A.P. and P.P.W.; project administration, P.P.W; funding acquisition, E.S.D., P.P.W. and O.A.P.

Funding

This research was funded by the Australian Dental Research Foundation Ltd., grant application number 0008-2021.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the HABS LNR Committee of The University of Queensland (2021/HE001054) on 28 June 2021.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr Scott Currell for assistance in the formulation of the survey questions, and Dr Farah Zahir from Queensland Cyber Infrastructure Foundation (QCIF) Bioinformatics and Data Science for help with the statistical analysis.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors report that a financial affiliation exists for this paper. O.A.P. has served as a consultant with Dentsply Sirona. The authors P.P.W. and E.S.D. declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Blackman, A.; Bottle, S.; Schmid, S.; Mocerino, M.; Wille, U. Chemistry, 5th ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Milton Australia, 2023; pp. 632–635. [Google Scholar]

- Nygaard-Ostby, B. Chelation in root canal therapy. Ethylendiamine tetraacetic acid for cleansing and widening of root canals. Odontol. Tidskr. 1957, 65, 3–11. [Google Scholar]

- Hülsmann, M.; Heckendorff, M.; Lennon, A. Chelating agents in root canal treatment: mode of action and indications for their use. Int. Endod. J. 2003, 36, 810–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, O.A.; Boessler, C.; Zehnder, M. Effect of liquid and paste-type lubricants on torque values during simulated rotary root canal instrumentation. Int. Endod. J. 2005, 38, 223–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orstavik, D. Essential Endodontology:Prevention and Treatment of Apical Periodontitis; John Wiley & Sons: 2020, p.294.

- Peters, O.A.; Arias, A. Shaping, disinfection, and obturation for molars. In The Guidebook to Molar Endodontics; Peters, O.A., Ed.; Springer-Verlag: Berlin, 2017; pp. 133–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.J.; Park, S.J.; Park, S.H.; Hwang, Y.C.; Yu, M.K.; Min, K.S. Efficacy of flowable gel-type EDTA at removing the smear layer and inorganic debris under manual dynamic activation. J. Endod. 2013, 39, 910–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dutner, J.; Mines, P.; Anderson, A. Irrigation trends among american association of endodontists members: a web-based survey. J. Endod. 2012, 38, 37–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Virdee, S.S.; Ravaghi, V.; Camilleri, J.; Cooper, P.; Tomson, P. Current trends in endodontic irrigation amongst general dental practitioners and dental schools within the United Kingdom and Ireland: a cross-sectional survey. Br. Dent. J. 2020, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savani, G.M.; Sabbah, W.; Sedgley, C.M.; Whitten, B. Current trends in endodontic treatment by general dental practitioners: report of a United States national survey. J. Endod. 2014, 40, 618–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikheikina, A.; Novozhilova, N.; Polyakova, M.; Sokhova, I.; Mun, A.; Zaytsev, A.; Babina, K.; Makeeva, I. Knowledge, attitude, and practice towards chelating agents in endodontic treatment among dental practitioners. Dentistry journal 2023, 11, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartlett, J.; Kotrlik, J.; Higgins, C. Organizational research: determining appropriate sample size in survey research Information technology, learning, and performance journal 2001, 19, 43.

- Beasley, T.M.; Schumacker, R.E. Multiple regression approach to analyzing contingency tables: post hoc and planned comparison procedures. The Journal of Experimental Education 1995, 64, 79–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkwood, B.; Sterne, J. Essential Medical Statistics, 2nd ed.; Blackwell Science: Carlton, Australia, 2003; pp. 148–176. [Google Scholar]

- Premier Dental. For Chemo-mechanical Preparation of Root Canals. Available online: https://www.premierdentalco.com/product/endo/chemo-mechanical-preparation/rc-prep/ (accessed on 14 May 2024).

- Clarkson, R.M.; Podlich, H.M.; Moule, A.J. Influence of ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid on the active chlorine content of sodium hypochlorite solutions when mixed in various proportions. J. Endod. 2011, 37, 538–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, P.P.; Cooper, C.; Kahler, B.; Walsh, L.J. From an assessment of multiple chelators, clodronate has potential for use in continuous chelation. Int. Endod. J. 2020, 53, 122–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zehnder, M.; Schmidlin, P.; Sener, B.; Waltimo, T. Chelation in root canal therapy reconsidered. J. Endod. 2005, 31, 817–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Safety data sheet File-Eze. Available online: https://www.ultradent.com/Resources/GetSds?key=21-001-09.82735475-en-gb (accessed on 14 May 2024).

- Glyde file prep safety data sheet. Available online: https://www.dentsplysirona.com/content/dam/flagship/en/service/safety-data-sheets/english-australia/Glyde%20File%20Prep%204613-71-Dec21.pdf (accessed on 14 May 2024).

- File-Eze EDTA chelating & filing lubricant. Available online: https://assets.ctfassets.net/wfptrcrbtkd0/53ba3c2e-8e18-4e91-a9ab-c0d7d03671bf/0bbc938116f42cd0532c93bb5b1a7953/File-Eze-EDTA-File-Lubricant-IFU-10187-UAR10.pdf (accessed on 14 May 2024).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).