1. Introduction

Cyberbullying affects the way of life of people of all groups, particularly youth in Thailand, who rank highest in internet usage compared to the groups [

1]. Youth do not screen nor carefully select modern technology for use in daily living. At the same time, violence against each other via social media has increased and caused cyberbullying that can happen anytime through electronic communication tools such as computers and cell phones that everyone can access easily [

2]. Cyberbullying can be classified into five categories: 1) Verbal aggression: This includes harmful verbal actions in the cyber world, such as offensive language, derogatory remarks, mocking embarrassing behavior, ridiculing physical appearance, and dishonorable challenges. 2) Defamation: This involves spreading shame, creating hatred, disseminating manipulated images, sharing embarrassing photos, and releasing unfavorable news. 3) Impersonation: This involves using another person’s name in conversations to harm them, create embarrassment to them, manipulate their images, seek personal gain using their name, or borrow money or possessions in their names. 4) Privacy breach: This involves revealing or forwarding parents’ names, revealing or sharing inferiority complex, embarrassing secrets, sharing personal information without consent, and exchanging secrets with third persons; and 5) Blocking or deleting: This involves removing disliked individuals from one’s friend list, blocking people disliked within a group, forcing friends to delete disliked individuals, and compelling friends to block those disliked within a group. These actions occur rapidly and effectively through online social networks, providing a platform for everyone to freely perceive and express opinions. Meanwhile the victims, unable to respond, experience stress, pain, embarrassment, and a loss of confidence in their social existence [

2,

3].

A comprehensive review of related literature revealed that the impact of cyberbullying victims has intensified, emerging as a silent threat to Thai youth contributing to a range of social issues [

4,

5]. Research findings indicate that cyberbullying significantly correlates with suicide, drug use behaviors, and unsafe sexual practices among young individuals in addition to mental distress leading to daily life concerns [

6,

7]. Cyberbullying manifests both direct and indirect effects on the targeted person. Direct effects include gossip, vulgar language, defamation, threats, and verbal harassment resulting in emotions such as anger, frustration, stress, anxiety, and embarrassment. Indirect consequences impact mental health, physical well-being, depression, social relationship difficulties, and even suicidal ideation [

7,

8].

Recent studies on the prevalence of cyberbullying among youth, it has been found that cyberbullying occurs at a significantly high rate. For instance, it accounts for 51% of the central part of Thailand [

9], 40% of the United States [

10], 23% among youth in the Midwestern states of the United States [

7], 54% of a university in the United States [

11], 40% in England [

12], 53% in Germany [

13], 29% in Israel [

14], and 39% in Belgium [

15]. One crucial causal factor contributing to cyberbullying stems from negative family upbringing. Whether it is overly strict and controlling parenting, neglectful parenting with minimal supervision, or indulging parenting that excessively caters to the child’s desires and fosters self-centeredness, all forms of negative family upbringing can lead to feelings of sadness, repression, and emotional distress among youth. These negative emotions often result in inappropriate behaviors, including cyberbullying [

16,

17,

18]. Additionally, the causal factors contributing to cyberbullying include both influences of aggressive behavior from individuals as well as the media. These include influences from parental aggression, peer aggression, internet idol aggression, film violence, video game violence, and news violence. These factors are linked to the absorption and imitation of negative behaviors from individuals and the media. Specifically, youth tend to imitate those who are close to them, interesting, and with whom they have frequent interactions. Consequently, these behaviors manifest in their interactions with people around them in their daily lives. Studies found that aggressive individuals and media content depicting threats and violence are often associated with youth’s violent behaviors and cyberbullying [

19,

20].

Moreover, there are negative mental factors that contribute to cyberbullying. These include feelings of frustration, anxiety, and paranoia. Such emotions often trigger anger, fear, pressure, irritability, and quick mood swings. Consequently, individuals may exhibit inappropriate verbal expressions and actions. Research has found that the process of absorbing and accumulating past experiences plays a role in developing negative mental traits related to unmet emotional needs and the inability to act or express oneself as desired. These traits may arise due to obstacles or lack, resulting in feelings such as frustration, resentment, irritability, anxiety, worry, distress, worry, and apprehension. Subsequently, these symptoms transform into emotional frustration, anxiety, and paranoia, which tend to correlate with aggressive behavior and cyberbullying as an outlet for the emotions experienced at that moment [

21,

22,

23,

24].

From the aforementioned incidents, it is evident that cyberbullying poses a silent threat that deserves attention and awareness regarding its ensuing impact. Consequently, urgently studying causal factors through a thorough analysis is essential for preventing cyberbullying among youth. Therefore, the objective of this research is to explore the causal factors influencing cyberbullying in young individuals. The findings from this study will benefit both individuals and directly related organizations in effectively managing the issue of cyberbullying before it escalates into a societal problem. Collaboratively, we can seek solutions to timely address this pressing concern.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The subjects

The subjects consisted of youth whose online behavior involved using social media for at least three consecutive hours per day due to the prevailing trend of online cyberbullying [

25]. As a general guideline, 340 Subjects were recruited, following the recommendation by multilevel analysts, which suggests 20 subjects per variable [

26]. The sampling process followed a multi-step approach: Step 1: District Selection--Districts were chosen through stratified random sampling based on three levels: Red districts: High densities of losses per capita; Pink districts: Medium per capita loss density; and Green districts: Low densities of losses per population. The selection criteria were based on data and trends in violence from the Center of Deep South Watch [

27]. Then 1 district/province was selected per one region through simple random sampling and 9 districts were ultimately selected. Step 2: Sub-District Selection--Within each district, two sub-districts were chosen using a simple random sample selection method (lots drawn without replacement). This resulted in a total of 18 sub-districts. Step 3: Final step of sample section--In the final step, 18 or 19 Subjects per sub-district were selected, yielding a total of 340 individuals. The Subject was identified in collaboration with the sub-district youth group of the local government organization. Their assistance was sought to coordinate and jointly select youth participants for this research.

2.2. Research instruments

The research instrument comprised a 6-part questionnaire created through an in-depth study of related concepts, theories, and relevant literature. Its purpose was to define operational terms and establish the structure of the variables under investigation. The question items were formulated based on the operational definitions, and relevant questions from existing academic sources were adapted. Then the questionnaire was validated by 5 experts for content validity resulting in IOC (item-objective congruence) values ranging from 0.60 to 1.00. A pilot test was conducted with 45 non-sample participants and the internal consistency was measured using Cronbach’s alpha coefficient, yielding a value of 0.785.

2.3. Data collection

The researcher and research assistants with experience from many studies went into the field together to collect relevant data. A team of data collection staff received training on the field data collection methods and gained a comprehensive understanding of the questionnaire’s specific questions. This training aimed to ensure consistency among the staff members during data collection.

2.4. Data analysis

The analysis of causal factors impacting cyberbullying among youth in the three Southern border provinces utilized Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) statistical techniques. The objective was to assess the alignment between the hypothesized model and empirical data. Additionally, both direct and indirect influences as well as the total impact of causal variables were analyzed. For parameter estimation, the Maximum Likelihood Estimates (ML) method was used to analyze the model based on the specified hypothesis.

3. Results

The examination of the consistency of the structural equation model regarding causal factors affecting youth cyberbullying in the three Southern border provinces revealed that the model did not align well with empirical data. Consequently, adjustments were made by modifying the correlation pairs associated with insignificant error values. Subsequently, the final structural equation model for causal factors demonstrated good alignment with empirical data. Key statistical indicators include a relative chi-square (χ²/df) value of 1.77, a GFI (Goodness of Fit Index) value of 0.94, and a root mean square index of approximate differences (RMSEA) of 0.049. (See

Table 1).

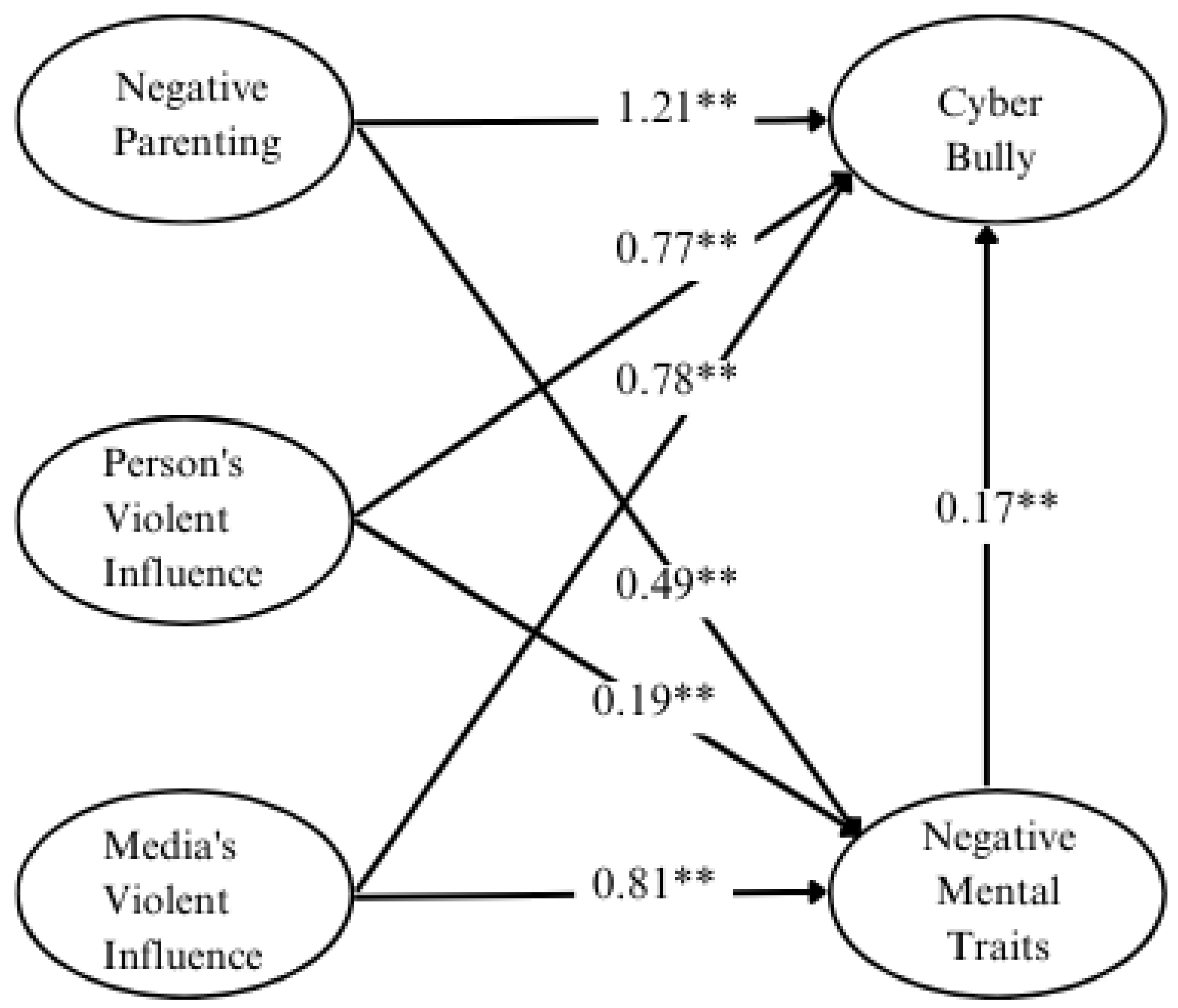

When examining the results of estimating the direct influence of negative mental traits, it was observed that the negative upbringing variable collectively influenced these traits. The influence of personal violence and the influence of media violence were statistically significant at the 0.001 and 0.05 levels, respectively. Among these variables, the influence of media violence exhibited the highest direct influence on negative mental traits, with a total influence size of 0.81. Following closely was the variable related to negative upbringing, which had a total influence size of 0.49. Lastly, the influence of personal violence had a total influence size of 0.19.

When considering the results of estimating the direct and indirect influences on cyberbullying, it was found that cyberbullying received total influence from variables related to negative mental traits, negative upbringing, the influence of personal violence, and the influence of media violence—all statistically significant at the 0.001 level. The variables with the highest direct and indirect influence on cyberbullying were: Negative upbringing, with a total influence size of 1.13; the influence of personal violence, with a total influence size of 0.74; and the influence of media violence, with a total influence size of 0.64. Additionally, the variable of negative mental traits had a direct influence on cyberbullying at a statistical significance level of 0.05, with a total influence size of 0.17.

The analysis results regarding the direct and indirect influences, as well as the total influence of latent variables affecting cyberbullying among youth in the three Southern border provinces, are as follows:

1) Negative upbringing had a total influence on negative mental traits equal to 0.49, which was a direct influence, and negative upbringing had a total influence on cyberbullying equal to 1.13, which was a direct influence equal to 1.21, and as an indirect influence through negative mental traits equal to - 0.08.

2) The total influence of personal violence on negative mental traits was 0.19, which was a direct influence, and the influence of personal violence had a total influence on cyberbullying equal to 0.74, which was a direct influence equal to 0.77 and an indirect influence through negative mental traits equal to - 0.03.

3) The influence of media violence had a total negative influence of 0.81, which was a direct influence, and the influence of media violence had a total influence on cyberbullying equal to 0.64, which was a direct influence equal to 0.78 and as an indirect influence through negative mental traits equal to - 0.14.

4) Negative mental traits had a total influence on cyberbullying equal to 0.17, which was a direct influence.

When assessing the ability of latent variables to explain the variation in indicators (or the prediction coefficient, R

2) within the internal latent variable structural equation, it was found that the prediction coefficient (R

2) of negative mental traits was equal to 0.892. This indicated that the variables in the structural equation model were able to explain 89.2% of the variance in negative mental traits, while the predictive coefficient (R2) of cyberbullying was 0.923. This indicates that the variables in the structural equation model could explain 92.3% of the variance in cyberbullying. Details are shown in

Table 2 and

Figure 1.

4. Discussion

The study has found that the most significant direct and indirect influences related to cyberbullying stem from negative upbringing variables. Specifically, family factors such as controlling parenting, neglectful parenting, and indulgent upbringing play crucial roles as causal factors that influence youth to engage in cyberbullying behavior. This behavior stems from a negative upbringing, where parents are controlling, authoritarian, and neglectful tendencies. By imposing their own opinions and disregarding their child’s opinions, parents may make their children feel dependent, unable to express themselves freely, and constrained by rigid discipline. Violations of these rules result in severe punishment. Consequently, some children alleviate these emotions by engaging in cyberbullying as a means of self-expression [

16,

17]. In addition, a negative upbringing can lead children to become repressed, mistrustful of others, view others as adversaries rather than friends, adopt a pessimistic outlook, struggle to adapt to society, exhibit aggression, stubbornness, conflict, uncooperativeness, jealousy, indifference, unruliness, and an inability to get along with others [

18,

20,

22]. When children experience inappropriate parenting, they may express undesirable behavior based on what they have learned. This is particularly true if they perceive that their parents treat them harshly and unfairly, withholding genuine love and support. In such cases, children often react strongly to their parents. Additionally, if they perceive that someone condones their aggressive bullying behavior, they are more likely to repeat such severe actions [

21,

23]. Therefore, upbringing significantly influences children’s personality, temperament, behavior, and overall development. When children receive an unsuitable upbringing that does not align with their circumstances, it can lead to the development of an undesirable personality that contradicts social norms. Ultimately, this can pose challenges for children in terms of social adjustment and may result in the expression of unwanted behaviors [

28,

29].

The latent variables that directly and indirectly influence cyberbullying include personal violence and the impact of media. This demonstrates that various forms of violence such as parental violence, peer violence, net idols’ influence, film violence, gaming violence, and news violence play crucial roles as causal factors in youth cyberbullying. This occurs because the factors influencing individual violence ultimately contribute to negative behavior in youth. Young individuals learn by observing models and absorbing their behavior, which often unknowingly reinforces their violent conduct. Consequently, they may perceive such behavior as normal. Ultimately, young individuals exhibit these behaviors in their daily lives, believing that doing so can address various problems. The models they choose to imitate initially include people they respect, those with whom they have close relationships, favorite role models, and individuals whose interests align with their own [

30,

31]. Additionally, the influence of personal violence and media violence contributes to negative life experiences for youth. This serves as the starting point for young individuals to exhibit harmful behavior. They are stimulated to display violent conduct based on examples they have witnessed or encountered. As they repeatedly observe such behavior, their motivation to imitate it grows. Unfortunately, this environment places significant stress on young people over a long period. Consequently, they often develop symptoms of rebellion against adults and believe that using force and violence is necessary to gain acceptance and respect [

28,

32]. The influence of personal violence and media violence also transmits perceptions, principles, practices, attitudes, and values that are inappropriate for youth. This process renders young individuals ill-equipped to peacefully adapt to societal life, resulting in a high rate of conflict, quarrels, and physical harm among peers. Eventually, this escalates into a serious behavioral problem [

33]. Youth who have encountered violence from their surroundings and the media are significantly more likely to exhibit bullying behavior compared to those who have not experienced such violence 4.50 times [

20], 7.60 times [

34], and 7.11 times [

35]. One causal factor contributing to violent acts and delinquency among youth is exposure to violent or illegal events through various media and interactions with people [

36].

Furthermore, negative mental traits also exert both direct and indirect influences on cyberbullying. These negative mental traits such as frustration, anxiety, and feelings of insanity serve as crucial causal factors that influence youth to engage in cyberbullying behavior. The connection lies in the fact that young individuals with negative mental traits often experience emotions stemming from unmet desires. They may feel unable to pursue their heartfelt wishes or achieve their set goals. Youth frequently encounter obstacles, face shortages, and experience failures, leading to frustration, anxiety, and feelings of insanity. As these negative mental traits accumulate, youth seek outlets for these emotions. Ultimately, these emotions become bullying behavior in response to frustration, anxiety, and feelings of insanity [

17,

22]. Furthermore, negative mental characteristics also influence the emotions, feelings, and minds of youth. As a result, young individuals may experience anger, fear, and repression, along with emotional deficiencies that make them easily irritable and prone to anger. They may express themselves through inappropriate words and actions, feeling that they have not received justice and are not clearly understood. Over time, this accumulation of negative emotions leads to frustration, anxiety, and even feelings of insanity, which in turn can manifest as bullying behavior toward others [

21,

23]. Hence, it becomes evident that bullying behavior arises from negative mental influence, similar to the pressure building up in a boiling kettle. When the forces of frustration, anxiety, and insanity accumulate, they seek release through inappropriate expressions of behavior [

21,

23,

24]. The root cause of youth’s bullying behavior lies in negative mental traits. However, the extent to which bullying behavior manifests depends on the stimulating situations that trigger it. In other words, there must be a relationship between a person’s internal characteristics and external stimuli. If an individual has few negative mental traits (such as frustration, anxiety, and insanity) but encounters numerous stimulating situations, bullying behavior may occur. Conversely, if someone possesses many negative mental traits but experiences few stimulating situations, bullying behavior may not manifest [

21,

24,

28]. One noticeable characteristic among youth who bully others is their inability to contain emotions such as anger, frustration, anxiety, and even feelings of insanity, which often manifest as undesired behavior [

29,

37]. Additionally, an individual’s display of bullying behavior frequently depends on the context whether it’s frustration, anger, irritation, stress, or strictness [

38,

39,

40].

5. Conclusions

Cyberbullying received total influence from variables related to negative mental traits, negative upbringing, the influence of personal violence, and the influence of media violence—all statistically significant at the 0.001 level. The variables with direct and indirect influence on cyberbullying were: Negative upbringing, the influence of personal violence, and the influence of media violence, with a total influence size of 1.13, 1.13, and 0.64 respectively. Additionally, the variable of negative mental traits had a direct influence on cyberbullying at a statistical significance level of 0.05, with a total influence size of 0.17.

The findings from this research hold value for relevant organizations, institutions, and individuals, helping in the formulation of effective policies and concrete strategies to prevent, monitor, address, and reduce cyberbullying among youth. To achieve this, awareness and priority should be given to negative upbringing factors, which exert the most significant influence, followed by personal and media influences. These considerations serve as essential guidelines for preventing youth cyberbullying before it escalates into a more serious societal problem.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.L.; formal analysis, investigation, writing original draft preparation, writing review, and editing.

Funding

Please add: This study was financially supported by the Fundamental Fund from Science, Research and Innovation Fund for 2024, contract No. LIA6701017S.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study received approval from the Institutional Review Board for Human Subjects Research at Sirindhorn College of Public Health, Nakhon Si Thammarat, under certificate No. E09/2566, on 25 December 2023.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all the subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data availability is restricted due to privacy reasons. However, data may be available by writing to the correspondence author.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest. Funding sources were not involved in the study’s design, data collection, analysis, interpretation, manuscript composition, or the choice to submit the findings for publication.

References

- Electronic Transactions Development Agency (Public Organization). (2023). A survey report on the results of internet user behavior in Thailand in 2022. Bangkok: Ministry of Information Technology and Communications.

- Tudkuea, T. & Laeheem, K. (2014). Development of Indicators of Cyberbullying among Youths in Songkhla Province. Asian Social Science, 10(14), 74–80. [CrossRef]

- Pokpong, S. & Musikphan, W. (2010). Factors affecting attitudes and behavior of physical violence and cyberbullying of Thai youth. Bangkok: Mahidol University.

- Kazdin, A. E. (1977). The token economy: A review and evaluation. New York: Plenum Press.

- Samoh N., Boonmongkon P., Ojanen T. T., Ratchadapunnathikul C., Damri T., Cholratana M., Guadamuz T. E. (2014). Cyberbullying among a national sample of Thai secondary school students: implications for HIV vulnerabilities. Proceeding of 20th International AIDS Conference Melbourne, Australia, 20-25 July 2014.

- Anker, C. K. (2011). Bullying in the age of technology: A literature review of cyberbullying for school counselors (Unpublished master’s thesis). University of Wisconsin-Stout, Menomonie, WI.

- Litwiller, B. J. & Brausch, A. M. (2013). Cyber bullying and physical bullying in adolescent suicide: The role of violent behavior and substance use. Journal Youth Adolescence, 42(5), 675–684. [CrossRef]

- Hines, N. (2011). Traditional bullying and cyber-bullying: Are the impact on self-concept the same? (Unpublished master’s thesis). Western Carolina University, Cullowhee, NC.

- Laisuwannachart, P., Suteeprasert, T., & Bunsiriluck, S. (2022). Factors predicting cyberbullying perpetration and victimization among students in central Thailand. Journal of Mental Health of Thailand, 30(2), 100–113.

- Bhat, C. S. (2008). Cyberbullying: Overview and strategies for school counselors, guidance officers, and all school personnel. Australian Journal of Guidance and Counselling, 18(1), 53–66.

- Pinchot, J. & Paullet, K. (2013). Social networking: Friend or foe? A study of cyberbullying at a university campus. Issues in Information Systems, 14(2),174–181.

- Tarapdar, S. & Kellett, M. (2013). Cyberbullying: Insights and age-comparison indicators from a youth-led study in England. Child Indicators Research, 6(3), 461–477. [CrossRef]

- Wölfer, R., Schultze-Krumbholz, A., Zagorscak, P., Jäkel, A., Göbel, K., & Scheithauer, H. (2014). Prevention 2.0: targeting cyberbullying@ school. Prevention Science, 15(6), 879–887.

- Lefler, L. N. & Cohen, D. M. (2015). Comparing cyberbullying and school bullying among school students: prevalence, gender, and grade level differences. Social Psychology of Education: An International Journal, 18(1), 1–16.

- DeSmet, A., Veldeman, C., Poels, K., Bastiaensens, S., Van Cleemput, K., Vandebosch, H., & DeBourdeaudhuij, I. (2014). Determinants of self-reported bystander behavior in cyberbullying incidents amongst adolescents. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 17(4), 207–215. [CrossRef]

- Baumrind, D. (1991). The influence of parenting style on adolescent competence and substance use. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 11(1), 56–95. [CrossRef]

- Laeheem, K. (2013). Factors associated with bullying behavior in Islamic private schools, Pattani province, southern Thailand. Asian Social Science, 9(3), 55–60. [CrossRef]

- Tudkuea, T., Laeheem, K., & Sittichai, R. (2019). Development of a causal relationship model for cyber bullying behaviors among public secondary school students in the three southern border provinces of Thailand. Children and Youth Services Review, 102(3), 145–149. [CrossRef]

- Espelage, D. L., Low, S., Rao, M. A., Hong, J. S. & Little, T. D. (2013). Family violence, bullying, fighting, and substance use among adolescents: A longitudinal mediational model. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 2(1), 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Laeheem, K., Kuning, M., McNeil, N., & Besag, V. E. (2008). Bullying in Pattani primary schools in Southern Thailand. Child: Care Health and Development, 35(2), 178–183. [CrossRef]

- Berkowitz, L. (1989). The frustration-aggression hypothesis: An examination and reformulation. Psychological Bulletin, 106(1), 59–73.

- Dollard, J., & Miller, N. E. (1939). Frustration and aggression. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Laeheem, K. (2013). Family and upbringing background of students with bullying behavior in Islamic private schools, Pattani province, southern Thailand. Asian Social Science, 9(7), 162–172. [CrossRef]

- Olweus, D. (1995). Bullying or peer abuse at school: Facts and intervention. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 4(6), 196–200. [CrossRef]

- Dayanan, J. (2011). Behavior and the impact of using social network site: www.facebook.com. (Unpublished master’s thesis). Thammasat University, Bangkok.

- Hair, J., Anderson, R., Tatham, R., & Black, W. (1998). Multivariate data analysis with readings. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

- Center of Deep South Watch. (2023). The Data and Trends of the situation severity in the South. Pattani: Center of Deep South Watch.

- Laeheem, K. (2014). Domestic violence behaviors between spouses in Thailand. Asian Social Sciences, 10(16), 152–159. [CrossRef]

- Laeheem, K. & Boonprakarn, K. (2015). Family background risk factors associated with domestic violence among married Thai Muslims’ couples in Pattani province. Asian Social Science, 11(9), 235–244. [CrossRef]

- Baldry, A. C. (2003). Bullying in schools and exposure to domestic violence. Child Abuse & Neglect, 27(7), 713-732. [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

- Straus, S. (2001). Contested meanings and conflicting imperatives: A conceptual analysis of genocide. Journal of Genocide Research, 3(3), 349–375. [CrossRef]

- Parimutto, A. (2011). Family conflict solution applied from Theravāda Buddhism Dhamma (Unpublished master’s thesis). Mahachulalongkornrajavidyalaya University, Bangkok.

- Laeheem, K., Kuning, M., & McNeil, N. (2009). Bullying: Risk factors becoming ‘Bullies’. Asian Social Science, 5(5), 50–57.

- Laeheem, K., Kuning, M., & McNeil, N. (2010). Bullying: The identify technique and its major risk factors. In Proceeding of the 2nd international conference on humanities and social sciences, 10 April, 2010. (pp. 31–42). Songkhla: Prince of Songkla University.

- Malley-Morrison, K. & Hines, D. A. (2007). Attending to the role of race/ethnicity in family violence research. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 22(8), 943–972. [CrossRef]

- Sheras, P. (2002). Your child: Bully or victim? Understanding and ending schoolyard tyranny. New York, NY: Skylight Press.

- Anderson, C. A., Anderson, K. B., & Deuser, W. E. (1996). Examining an affective aggression framework: Weapon and temperature effects on aggressive thoughts, affect, and attitudes. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 22(4), 366–376.

- Bandura, A. (1977). Social learning theory. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall Inc.

- Roger, D. (1972). Issues in adolescent psychology. New York: Meredith Corporation.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).