Introduction

The exchange of knowledge, abilities, and experience between people, teams or institutions is mentioned to as knowledge sharing (Assegaff & Dahlan, 2011). Knowledge sharing is a technique that disseminates knowledge and expertise from one individual, team, or organization to others (Pangil & Mohd Nasurddin, 2013). Knowledge exchange among healthcare professionals is crucial for establishing best practices and continuity in patient care (Assem & Pabbi, 2016). Shehab et al. (2019) studied the knowledge-sharing practices of online healthcare groups’ nursing supervisors. The findings showed that individual characteristics (trust, kindness, goodwill, and sharing ability) have a statistically significant direct effect on KS behaviour. Mohajan (2019) investigated the methods, obstacles and advantages of knowledge sharing in organizations. Adeyelure et al. (2019) conducted an empirical investigation on KS by the medical system. They identified key players and networks that facilitate knowledge transfer and retention. Hence, KS is critical since it enables individuals to gain from already-existing knowledge bases both inside and outside of the company (Carmeli et al., 2013). Besides, knowledge sharing is critical for managing medical waste in healthcare settings. The dissemination of information regarding medical waste to paramedics, patients, and other members of the community is crucial for proper waste treatment and compliance with legislation (Exposto et al., 2022). There are various countries that use the term “medical waste,” including the US, South Korea, and China (Attrah et al., 2022; Yoon et al., 2022). Medical waste is produced by numerous activities. Hospitals and clinics create trash from several units, including medical wards, operating rooms, surgical wards, healthcare units, laboratories, and pharmaceutical and chemical depots (Alam et al., 2013). MW needs particular treatment and management from source to disposal (Hassan et al., 2008). Medical waste management is the systematic process of managing, collecting, segregating and disposing of waste (Attrah et al., 2022. From trash creation to disposal, proper medical waste management (MWM) regulates waste, safeguarding the environment, society, and public health (Akkajit et al., 2020). Singh et al. (2022) looked into the current challenges and future possibilities for sustainable MWM. The findings demonstrated how important it is for workers to be aware of recommended practices and to know them in order to reduce infections and injuries in WM. Olaifa et al. (2018) looked at medical staff members’ attitudes and knowledge on WM. They showed that the participants’ knowledge of hospital WM was inadequate. Just over half of the participants had a good attitude toward the proper disposal of healthcare waste, however only 53.9% of them reported having effective strategies for managing healthcare waste. Clinicians’ knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors about medical waste management were evaluated by Akkajit et al. (2020). Yazie et al. (2019) studied healthcare WM present status and potential obstacles. Biswas et al. (2011) studied many areas of medical waste management at Bangladesh’s tertiary hospitals. The study found that nongovernment hospitals handled medical waste better than government hospitals. Hossain et al. (2021) investigated assessment of medical waste management practices at Gopalganj Sadar in Bangladesh. The study revealed no waste management or resource segregation system in place, as well as a lack of practical healthcare training for dealing with trash. Haque et al. (2021) carried out the study to assess the medical waste management system and practices. The survey’s findings showed that inconsistent rules and standards were not followed when it came to the segregation of all wastes, and that medical waste was typically disposed of with regular household trash. Moreover, Jahan et al. (2018) researched knowledge, attitude and practices on bio MWM among the health care personnel. However, studies on Knowledge sharing for the effective medical waste management is absent in the literature.

The connection between knowledge sharing, attitudes, and practices of healthcare providers and MWM is crucial for maintaining a safe and hygienic healthcare environment. Knowledge-sharing strategies impacted community home-based care institutions’ handling of healthcare risk waste, which in turn had an impact on the community (Masilela, 2017) One needs to be knowledgeable and have a positive attitude to counsel, assist, and shield patients from possibly harmful substances (Golandaj & Kallihal, 2021). Besides, PMWM relies heavily on healthcare personnel’s attitudes and behaviours towards medical waste (Mohammed et al., 2017). Attitudes have an impact on WM practices (Mensah & Ampofo, 2021). Healthcare providers’ attitudes are directly related to their practices (Asdaq et al., 2021). On the other hand, practices are society’s collective actions that are influenced by beliefs and information (Zand et al., 2020; Knickmeyer, 2020; Kofoworola, 2007). According to Asdaq et al. (2021), a positive attitude and enhanced understanding are associated with effective waste management practices. To achieve successful waste management in healthcare settings, medical staff members’ knowledge, attitudes, and actions must work in concert. Building this connection and guaranteeing adherence to waste management standards and laws requires ongoing education, training, and assistance. Therefore, it is essential to comprehend the existing WM strategy and the practice of information sharing among medical professionals in hospitals in order to improve MWM in Bangladesh. Finding a multidimensional analysis of knowledge sharing is the study’s goal.

Literature Review

The most generally held belief is that knowledge equals power (Uriarte, 2008). According to McInerney (2002), all learning-related activities, including studying, observation of others, personal experience, and conscious understanding of feelings, are active and dynamic methods of acquiring information. It may be categorized as private, public, shared, practical, theoretical, internal, external, hard, soft, foreground, or background but the division of knowledge into tacit and explicit knowledge continues to be the most popular (Pathirage et al., 2008). Explicit knowledge is formal and systematic in character, expressed through symbols and words. It can be recorded and stored in several formats, including printed, audiovisual, and electronic (Kaniki & Mphahlele, 2002). On the other hand, tacit knowledge is embodied knowledge that is ontological in nature and requires a lengthy socialization process and metaphorical expression (Omotayo, 2015).

Knowledge management (KM) is the procedures and techniques used to gather, distribute, and preserve knowledge (Sibbald et al., 2016; Kinney, 1998). KMt is individualistic. KS is the main system that connects the other KM procedures or activities. To effectively manage knowledge, it’s crucial to prioritize knowledge exchange in three areas: human, organizational, and technology (Davidavičienė et al., 2020).

Various definitions of knowledge sharing have been offered by scholars (Haque et al., 2023). According to Lee (2001), transferring or disseminating knowledge from one individual or group to another is known as KS. According to Helmstadter (2003), knowledge sharing involves interactions between humans using knowledge as the raw material. Besides, KS is an essential and prevalent activity in healthcare. In everyday practice, healthcare knowledge sharing happens during problem-solving interactions among healthcare personnel (Abidi, 2007). Moreover, knowledge exchange among healthcare professionals is crucial for establishing best practices and continuity in patient care (Assem & Pabbi, 2016).

The term “medical waste” describes hazardous, infectious, and other waste generated by health care facilities (Shareefdeen, 2012; Congress, 1988). Medical waste is contagious and harmful (Hassan et al., 2008). So, effective medical waste management is vital for healthcare facilities. Proper MWM relies on healthcare professionals’ knowledge, attitudes, and practices about medical waste (Mohammed et al., 2017). Besides, effective waste management requires training to raise awareness and improve efficiency (Alam et al., 2013). MWM involves gathering, segregating, storage, transportation, treatment, and disposal (Panyaping & Okwumabua, 2006; Theisen & Vigil, 1993). Waste segregation is necessary to guarantee cost control, environmental preservation, and safety. It is the fundamental elements of MWM (Johnson et al., 2013). Waste needs to be stored according to its type (Padmanabhan & Barik, 2019). For medical waste to be managed safely and scientifically in any setting, storage is essential stages (Abdullah & Al-Mukhtar, 2013). Waste disposal is also a vital part of waste management (Khan et al., 2019). Because the environment, patients, and staff are all impacted by the disposal of MW, both directly and indirectly (Awodele et al., 2016).

Theoretical Framework

The Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB)

The Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) emerged in the mid-1980s from the work of psychologist Icek Ajzen (Burns, 2017). The TPB describes human action through intention, focusing on perceived vs actual control (Burns, 2017; Ajzen, 1985; Ajzen, 1991). It is an extension of the idea of reasoned action, which addresses the limits of the original paradigm in dealing with activities over which individuals have limited volition (Ajzen, 1991; Ajzen, 1980; Fishbein, & Ajzen, 1977). According to the theory, a person’s attitude toward a behavior and their perception of societal norms have an impact on their intention to engage in that action. Intention is believed to influence actual behavior, such as participation levels. Subjective norms are impacted by the opinions of important people regarding the behavior (like engaging in a particular activity), whereas individual attitudes are influenced by assessments of the personal consequences of behavior. (Alexandris et al., 2007). This theoretical framework states that effective medical waste management will be impacted by the interaction of knowledge sources, staff monitoring and supervision, communication and collaboration, training and education, awareness and knowledge, attitudes, and practices. Effective medical waste management is significantly influenced by some variables. Medical personnel acquire knowledge from a variety of sources, including practical experience, formal training, seminars, and information exchange platforms (Bar-Dayan et al., 2014). This contribute to individuals’ attitudes and perceived behavioral control regarding waste management. Training and Education enhances individuals’ skills, knowledge, and attitudes toward waste management practices (Abdo et al., 2019). Training and education alter perceived behavioral control and attitudes. The effectiveness of a MWM program is determined on the medical staff’s knowledge and competence. (Source: Joseph et al., 2015). This might have an influence on how people view their behavioral control and attitudes. Medical professionals must interact to facilitate the sharing of resources and information required for an integrated infection and occupational disease prevention approach (Quinn et al., 2015). This has the potential to impact subjective norms and perceptions of behavioral control. Staff monitoring and supervision are required to carry out effective waste management processes (Khan et al., 2013). Implementing monitoring systems, such as waste monitoring applications, can help hospitals track and control medical waste (Letho et al., 2021). This has an impact on the perceived level of behavioral control. Proper medical waste management is strongly dependent on healthcare personnel’s attitudes and actions regarding medical waste (Mohammed et al., 2017). This is closely related to attitudes. Proper waste management methods are critical for maintaining proper hazardous MWM and safeguarding personnel from possible threats (Deress et al., 2019; Adogu et al., 2014). This impacts attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control.

Training and Education

Effective waste management requires training to raise awareness and improve efficiency (Alam et al., 2013). Training is a methodical procedure to improve an employee’s competency, knowledge, and skills-all of which are essential for them to do their jobs well. Various approaches, including peer cooperation, coaching and mentoring, and subordinate engagement, can be used to provide training (Elnaga & Imran, 2013). Employee knowledge, experiences, and skills are also enhanced through training programs (Malik & Kanwal, 2018; Nadeem, 2010). In order to develop and maintain strong infection control procedures, the most effective measures are formative training and continuing education (Moore et al., 2005). Besides, the purpose of health and safety training is to guarantee that employees are aware of the potential hazards linked to medical waste as well as the policies and guidelines necessary for safe handling (Buluzi, 2022). Better training could reduce the substantial occupational and public health risk associated with hospital cleaners’ inadequate waste management understanding and practices (Nwankwo, 2018). Moreover, training and education play crucial roles in effective waste management through sharing knowledge. Through training, people can share current knowledge to other members of an organization (Castaneda & Durán, 2018; Van Gramberg, & Baharim, 2005; Castañeda, & Ignacio, 2015).

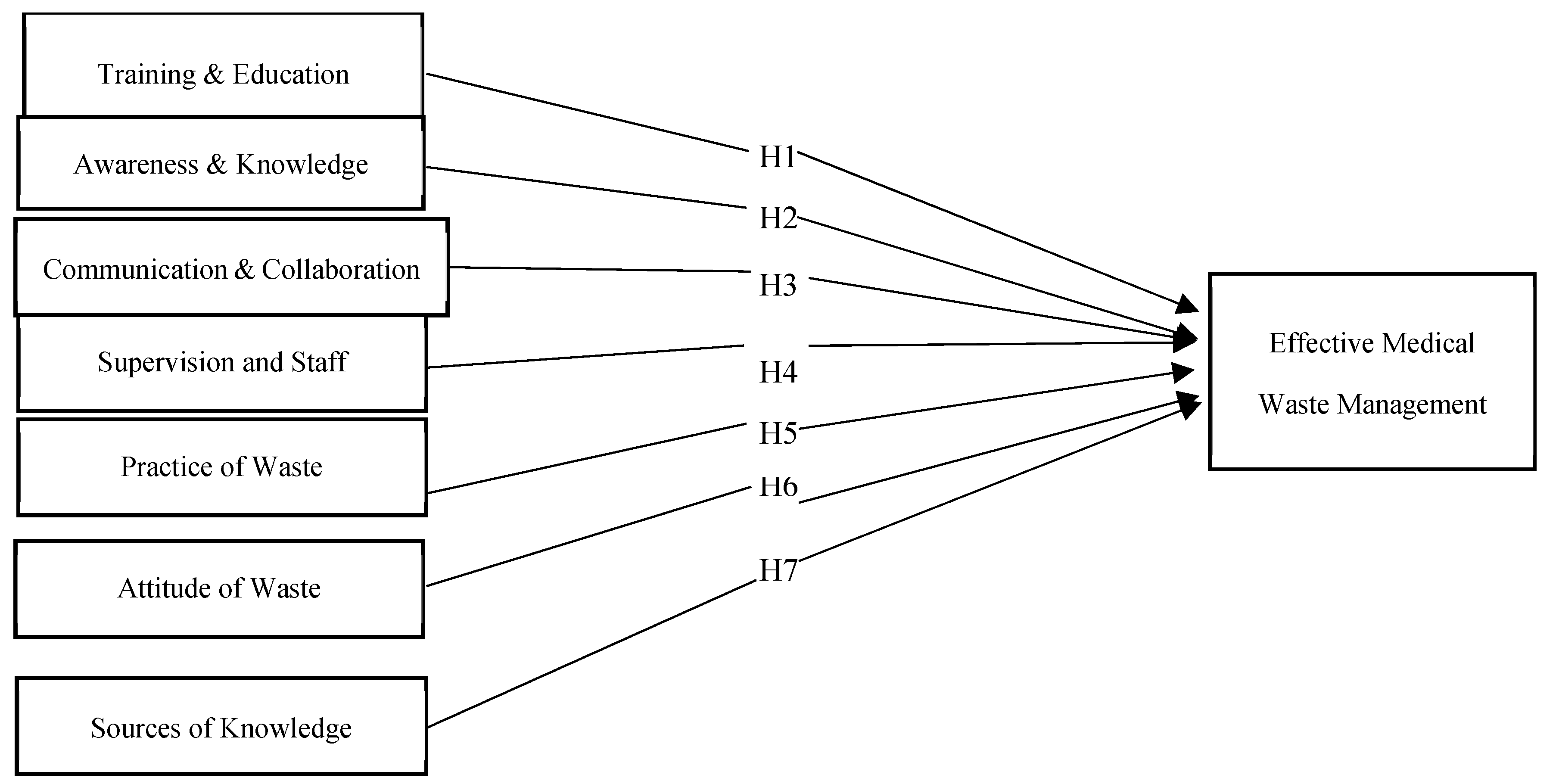

H1:

There is a positive relationship between training and education and effective medical waste management.

Awareness and Knowledge

Awareness is a practical achievement that emerges in and through social action and activity rather than a condition or a stable frame of reference that supervises or even organizes the organization of conduct (Heath et al., 2002). Raising awareness is essential to enhancing medical waste management. (Alam et al., 2013). The success of MWM depends heavily on the knowledge and abilities of healthcare professionals. Besides, healthcare professionals can stop the spread of infectious diseases and epidemics by participating in awareness programs on their safe handling and management (Joseph et al., 2015). The key reasons of incorrect handling of infectious chemicals include a lack of knowledge about waste collection and segregation, poor risk awareness, and unsafe waste disposal (Akkajit et al., 2020). Therefore, it is crucial to have enough understanding of the health dangers connected to hospital waste in order to ensure the proper disposal of hazardous medical waste and protect the population from its numerous detrimental effects. (Mathur et al., 2011). Hospital waste management cleaners are vulnerable to workplace hazards such as contagious diseases and wounds, while these risks may be decreased with education, experience, and safe work practices (Nwankwo, 2018). Healthcare personnel’ self-awareness in managing medical waste is an important ability that influences the quality of medical waste management (MWM) (Akkajit et al., 2020). Besides, awareness as a crucial component that promotes cooperation and knowledge exchange, especially among employees (Kim et al., 2019).

H2:

There is a positive connection between awareness and knowledge and effective medical waste management.

Communication and Collaboration

The process of collaboration depends on communication (Bozeman et al., 2013). Collaboration with others is necessary to “continuously” attain awareness (Heath, 2002). Collaboration on patient care requires effective communication among team members (Ellingson, 2002; Abramson & Mizrahi, 1996; Fagin, 1992). Besides, for nurse-physician relationships to improve, there must be regular, open communication (Ellingson, 2002). A key component of a successful collaboration for patient care is effective communication (McCaffrey et al., 2012; McKay et al., 2009). There are several ways for medical, non-medical, and cleaning workers to communicate: in person, through meetings and appointments, and through mobile phones, switchboards, and notes that were posted (Elling et al., 2022). Collaboration in waste management is essential to solving the waste management issues (Sathabhornwong, 2022). Creating safe workplaces requires effective communication regarding employee safety within health care organizations, particularly between occupational health and infection control staff (Lavoie et al., 2010). Besides, knowledge sharing practices and communication styles are closely associated (De Vries et al., 2010).

H3:

There is a positive connection between communication and collaboration and effective medical waste management.

Supervision and Staff Monitoring

Staff monitoring and supervision are techniques for overseeing and managing staff in order to ensure regulatory compliance, improve performance, and maintain quality standards (Mensah, 2022). Staff monitoring and supervision are necessary to conduct proper waste management procedures (KHAN et al., 2013). Besides, Staff monitoring and supervision can help handle any form of problem (Ozder et al., 2013). Implementing monitoring tools, such as waste monitoring apps, can help track and manage medical waste in hospital settings. So, healthcare workers and support staff must be monitored and supervised on a timely and effective basis (Letho et al., 2021). Besides, the chief of staffs are in charge of supervising hospital hygiene and implementing infection control measures (Padmanabhan & Barik, 2019). Knowledge sharing is also critical for employee monitoring since it improves organizational effectiveness and performance (Kız et al., 2012).

H4: There is a positive connection between supervision and staff monitoring and effective medical waste management.

Practice of Waste Management

Proper healthcare WM requires adequate practices among healthcare workers (Mugabi et al., 2018). Implementing effective waste management practices necessitates the use of trustworthy waste statistics (Metin et al., 2003). To achieve a sustainable solution for healthcare waste management, it’s important to investigate factors such as accessible policies and procedures, health care workers’ understanding of them, and implementation practices. Besides, infection can be considerably minimized by health care providers following excellent practices when handling and storing trash when performing health care procedures (Ramokate, 2008). Effective garbage disposal and society protection from the various undesirable consequences of hazardous waste can be achieved through the implementation of safety practices (Deress et al., 2019). Besides, proper waste handling practices are crucial for maintaining proper hazardous MWM and protecting workers from potential hazards (Deress et al., 2019; Adogu et al., 2014). Managing infectious trash requires healthcare staff to have proper education, a positive attitude, and follow safe measures (Haifete et al., 2016; Kumar et al., 2013). Health care professionals’ practices significantly impact proper waste segregation internationally (Haifete et al., 2016). Effective waste management relies on practices (Mohammed et al., 2017). In addition, Practices and habits are significant determinants in the success of information sharing (Karamitri et al., 2017; Liu et al., 2012).

H5:

There is a positivet connection between Practice of waste management and effective medical waste management.

Attitude of Waste Management

Attitude is a psychological inclination that is conveyed by appraising a specific thing with a degree of favor or disdain (Zanna et al., 2005; Eagly & Chaiken, 1993). Attitudes are critical because they predict and impact behavior, especially when firmly embedded or aligned with basic beliefs (Aishi et al., 2020). MW requires handling and disposal by trained medical specialists and is considered the second most hazardous garbage globally. Effective waste management requires attitudes. Proper medical waste management relies heavily on healthcare personnel’ attitudes, and behaviors towards medical waste (Mohammed et al., 2017). Proper healthcare waste management requires attitudes among healthcare workers (Mugabi et al., 2018). Managing infectious waste also requires healthcare staff to have a positive attitude (Haifete et al., 2016; Kumar et al., 2013). Health care personnel’, attitudes has a significant global impact on proper waste segregation (Haifete et al., 2016). Personal preventative actions work best when people have a positive attitude toward medical waste management. To avoid exposure to potentially hazardous substances, waste handlers must have enough knowledge and a positive attitude (Deress et al. 2019). Besides Research also suggests that organizational, technical, and individual variables may impact people’s attitudes toward information sharing (Chedid et al., 2022; Seonghee & Boryung, 2008; Lin, 2007; Tohidinia & Mosakhani, 2010; Patel & Ragsdell, 2011).

H6:

There is a favorable relationship between waste management attitudes and effective medical waste management practices.

Sources of Knowledge

Effective healthcare waste disposal is strongly dependent on the expertise of healthcare staff (Mohammed et al., 2017). To effectively limit health care waste, it is necessary to evaluate available policies and procedures, healthcare professionals’ awareness of them, and implementation techniques (Ramokate, 2008). Health care providers must understand waste segregation in order to appropriately separate all waste types and prevent the spread of infection. (Haifete et al. 2016). Proper information, processes, and safety precautions may enable safe trash disposal and protect society from the harmful consequences of hazardous waste (Deress et al., 2019). Proper hazardous waste management necessitates a high level of expertise and a positive attitude among trash handlers in order to protect them from potentially dangerous compounds. Healthcare waste management programs rely on health workers’ knowledge (Doylo et al., 2019). Medical personnel acquire knowledge from a variety of sources, including practical experience, formal training, seminars, and information exchange platforms (Bar-Dayan et al., 2014). Medical professionals also obtain knowledge from many sources such as English periodicals, textbooks, literature searches, experience, peers, expert doctors, and nurses (Uzunlulu et al., 2022; Yousefi-Nooraie et al., 2007; Kovačević et al., 2022). Waste management can be maintained by providing formal and informal knowledge (Debrah et al., 2021).

H7: There is a positive connection between the use of sources of knowledge and effective medical waste management.

Figure 1.

Model of research.

Figure 1.

Model of research.

Methodology

The researcher must understand both the research methods/techniques and the methodology (Kothari, 2004). Data collection methods vary among styles, traditions, and approaches, and no method is universally accepted or rejected (Bell & Waters, 2018).

Study Area

Bangladesh is a South Asian nation that is both impoverished and heavily populated (Islam & Biswas, 2014). Bangladesh now has approximately 14,770 health care facilities, including 654 governmental hospitals, 5055 private hospitals and clinics, and 9061 diagnostic institutes and pathology labs (Dihan et al., 2023). This study was carried out in nineteen government medical, diagnostic centers, and clinics in the northern part of Bangladesh for a 1-month period in 2024. The majority of the hospitals, clinics and diagnostic centers were selected in Rajshahi. These were located in Rajshahi’s Laxmipur region A. few hospitals were selected from other areas of Bangladesh.

Sampling and Measurement

This study selected 153 medical workers; nurse, lab technologist and cleaner at hospitals, diagnostic centers and clinics in the northern part of Bangladesh. This study aimed to identify a multifaceted analysis of knowledge sharing, training, communication and attitudes for effective medical waste management. There were two parts to the questionnaire. First, some basic personal data was collected from the respondents. Such as age, education level, gender, name of hospital, years of experience and designation. Another section gathered information about knowledge sharing practices and strategies for WM. Mixed-methods research was used in this study design. This research adopted a survey and interview as a research strategy. The samples were collected randomly. A five-point Likert scale (strongly agree to strongly disagree) was used for designing this questionnaire. Between February 2024 and March 2024, an online survey was conducted. Most of the data (133) was collected directly from the hospital through a Google form. A few data (20) were collected offline. Researchers took safety measures during data collection from the infectious area. For safety, researchers used masks and sanitized hands. Besides, after completing the data collection, used clothes were properly cleaned. This study conducted with strict ethics. The demographic profile of respondents reveals several key points. Regarding age distribution, the majority falls within the 26-35 age group, comprising 37.9%, followed by the 15-25 age group at 31.4%. Females represent a higher percentage of respondents compared to males, with 74.5% and 25.5%, respectively. In terms of education level, the majority have completed diploma courses (30.7%), while lab technologists, cleaners, and senior nurses/nurses are the primary designations among respondents. Most respondents share their knowledge regarding proper medical waste management always (77.8%) and prefer face-to-face communication for sharing knowledge with others (98.7%).

Data Analysis

Measurement Model

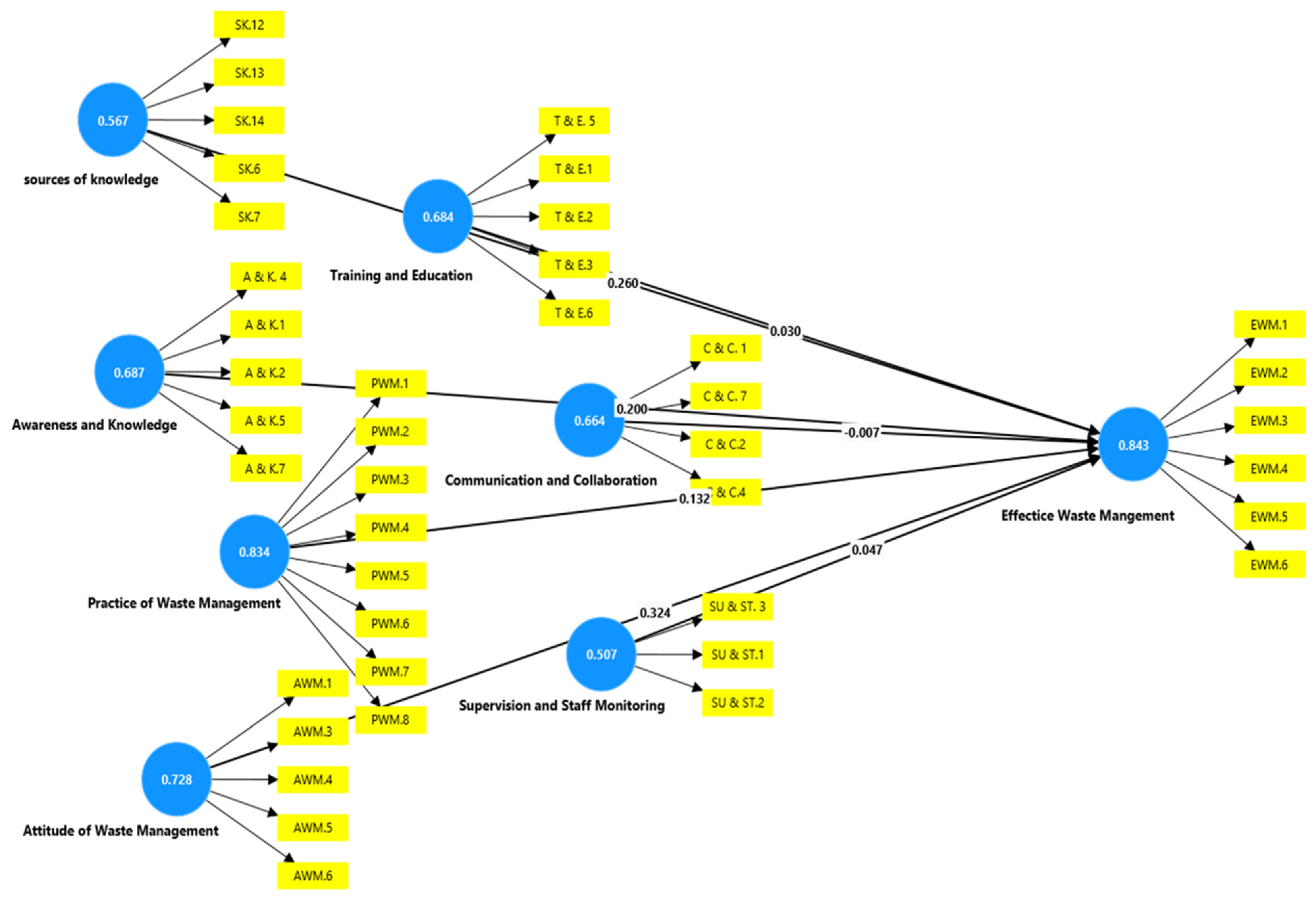

Assessing the evaluation framework is the first step in utilizing PLS-SEM. The measuring model assesses internal consistency, validity (convergent and discriminant validity), and indicator reliability. This is accomplished by computing two frequently used measures, Composite Reliability (CR) and Cronbach’s alpha (CA). Partial Least Squares (PLS) analysis favors CR over CA because CR ranks components based on dependability, whereas CA is determined by the amount of variables in each construct (Haque et al., 2023). Internal consistency metrics for the observed items are CA and CR (Haque et al., 2023). For exploratory study, reliability levels between 0.60 and 0.70 are considered suitable (Hair et al., 2021). Internal consistency is assessed using composite reliability (CR) (Muniandy et al., 2021). Chin (2009) and Hair et al. (2014) state that minimal factor loadings should be greater than 0.70, Composite reliability (CR) should be greater than 0.70, and to obtain convergent validity, the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) value must be greater than 0.50 (Ahmad et al., 2021). On the indicators, factor loadings of at least 0.60 are regarded as sufficient (Chin, 1998). Table 1 presents the findings of the factor loadings, CR, and AVE. Figure 2 shows the SmartPLS output of the measurement model.

Table 1.

—Factor loadings, composite reliability and average variance extracted (AVE).

Table 1.

—Factor loadings, composite reliability and average variance extracted (AVE).

| |

Items |

Factor Loading |

Cronbach’s alpha |

Composite reliability (rho_a) |

Composite reliability (rho_c) |

AVE |

| Attitude of waste management |

AWM1 |

0.472 |

0.728 |

0.807 |

0.821 |

0.489 |

| |

| |

AWM3 |

0.885 |

|

|

|

|

| |

AWM4 |

0.563 |

|

|

|

|

| |

AWM5 |

0.707 |

|

|

|

|

| |

AWM6 |

0.790 |

|

|

|

|

| Awareness and Knowledge |

AK1 |

0.651 |

0.687 |

0.697 |

0.794 |

0.437 |

| |

AK2 |

0.683 |

|

|

|

|

| |

AK4 |

0.546 |

|

|

|

|

| |

AK5 |

0.672 |

|

|

|

|

| |

AK7 |

0.739 |

|

|

|

|

| Communication and Collaboration |

CC1 |

0.896 |

0.664 |

0.927 |

0.773 |

0.474 |

| |

CC2 |

0.742 |

|

|

|

|

| |

CC4 |

0.543 |

|

|

|

|

| |

CC7 |

0.497 |

|

|

|

|

| Effective waste management |

EWM1 |

0.798 |

0.843 |

0.879 |

0.886 |

0.573 |

| |

EWM2 |

0.753 |

|

|

|

|

| |

EWM3 |

0.435 |

|

|

|

|

| |

EWM4 |

0.905 |

|

|

|

|

| |

EWM5 |

0.752 |

|

|

|

|

| |

EWM6 |

0.814 |

|

|

|

|

| Practice of waste management |

PWM1 |

0.748 |

0.834 |

0.864 |

0.87 |

0.461 |

| |

PWM2 |

0.697 |

|

|

|

|

| |

PWM3 |

0.768 |

|

|

|

|

| |

PWM4 |

0.597 |

|

|

|

|

| |

PWM5 |

0.478 |

|

|

|

|

| |

PWM6 |

0.597 |

|

|

|

|

| |

PWM7 |

0.711 |

|

|

|

|

| |

PWM8 |

0.778 |

|

|

|

|

| Sources of knowledge |

SK6 |

0.722 |

0.567 |

0.595 |

0.733 |

0.36 |

| |

SK7 |

0.54 |

|

|

|

|

| |

SK12 |

0.505 |

|

|

|

|

| |

SK13 |

0.516 |

|

|

|

|

| |

SK14 |

0.682 |

|

|

|

|

| Supervision and Staff monitoring |

SUST1 |

0.656 |

0.507 |

0.518 |

0.752 |

0.504 |

| |

SUST2 |

0.675 |

|

|

|

|

| |

SUST3 |

0.792 |

|

|

|

|

| Training and Education |

TE1 |

0.783 |

0.684 |

0.791 |

0.798 |

0.456 |

| |

TE2 |

0.896 |

|

|

|

|

| |

TE3 |

0.547 |

|

|

|

|

| |

TE5 |

0.444 |

|

|

|

|

| |

TE6 |

0.607 |

|

|

|

|

Figure 2.

—SmartPLS output of the measurement model assessment.

Figure 2.

—SmartPLS output of the measurement model assessment.

Composite reliability (CR) is higher than the recommended values of 0.50 and 0.70 for all categories. However, Ave of this study is somewhere less than .50 but the CR is already more than 0.70. Thus we can accept two convergent validity (Pahlevan Sharif et al., 2022).

To find out if a construct discriminates against other constructs in the same model, discriminant validity is required (Ahmad et al., 2021). Using the Fornel-Larcker criterion is the first step towards testing discriminant validity as it will identify the latent variable that best explains its indicator compared to other latent variables. When the square root of a construct’s AVE is higher than its correlation with another construct, they claim that discriminant validity has been proven (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). HTMT provides a numerical representation of the differences between constructions in terms of internal consistency. HTMT provides a more complete examination of discriminant validity by considering both the degree of dependability within constructs and the strength of linkages between them (Haque et al., 2023). The study improved results by removing 18 entries, including codes AWM2, AWM7, SUST4, SUST5, SUST6, CC3, CC5, CC6, AK3, AK6, TE4, SK1, SK2, SK3, SK4, SK5, SK7, SK8, SK9, SK10, and SK11. The second table shows evidence for discriminant validity in this experiment. Table 3 also includes the results of the Heterotrait-Monotrait Ratio (HTMT)-based Discriminant Validity ratings.

Table 2.

Discriminant validity based on Fornell-Larcker criterion.

Table 2.

Discriminant validity based on Fornell-Larcker criterion.

| Variables |

AWM |

AK |

CC |

EWM |

PWM |

SK |

SUST |

TE |

| AWM |

0.7 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| AK |

0.432 |

0.661 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| CC |

0.553 |

0.456 |

0.688 |

|

|

|

|

|

| EWM |

0.556 |

0.532 |

0.389 |

0.757 |

|

|

|

|

| PWM |

0.335 |

0.497 |

0.206 |

0.451 |

0.679 |

|

|

|

| SK |

0.328 |

0.385 |

0.305 |

0.509 |

0.358 |

0.6 |

|

|

| SUST |

0.317 |

0.493 |

0.444 |

0.34 |

0.195 |

0.25 |

0.71 |

|

| TE |

0.174 |

0.231 |

-0.024 |

0.265 |

0.361 |

0.30 |

0.148 |

0.675 |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Table 3.

—Discriminant validity based on Heterotrait-Monotrait Ration (HTMT).

Table 3.

—Discriminant validity based on Heterotrait-Monotrait Ration (HTMT).

| variables |

AWM |

AK |

CC |

EWM |

PWM |

SK |

SUST |

TE |

| AWM |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| AK |

0.595 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| CC |

0.732 |

0.622 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| EWM |

0.675 |

0.631 |

0.426 |

|

|

|

|

|

| PWM |

0.494 |

0.573 |

0.264 |

0.482 |

|

|

|

|

| SK |

0.499 |

0.569 |

0.409 |

0.666 |

0.484 |

|

|

|

| SUST |

0.493 |

0.806 |

0.767 |

0.502 |

0.358 |

0.505 |

|

|

| TE |

0.331 |

0.343 |

0.161 |

0.342 |

0.449 |

0.518 |

0.377 |

|

| AWM= Attitude of waste management, AK= Awareness and knowledge, CC= Communication and collaboration, EWM= Effective medical waste management, PWM= Practice of waste management, SK= Sources of knowledge, SUST= Supervision and staff monitoring, TE= Training and education. |

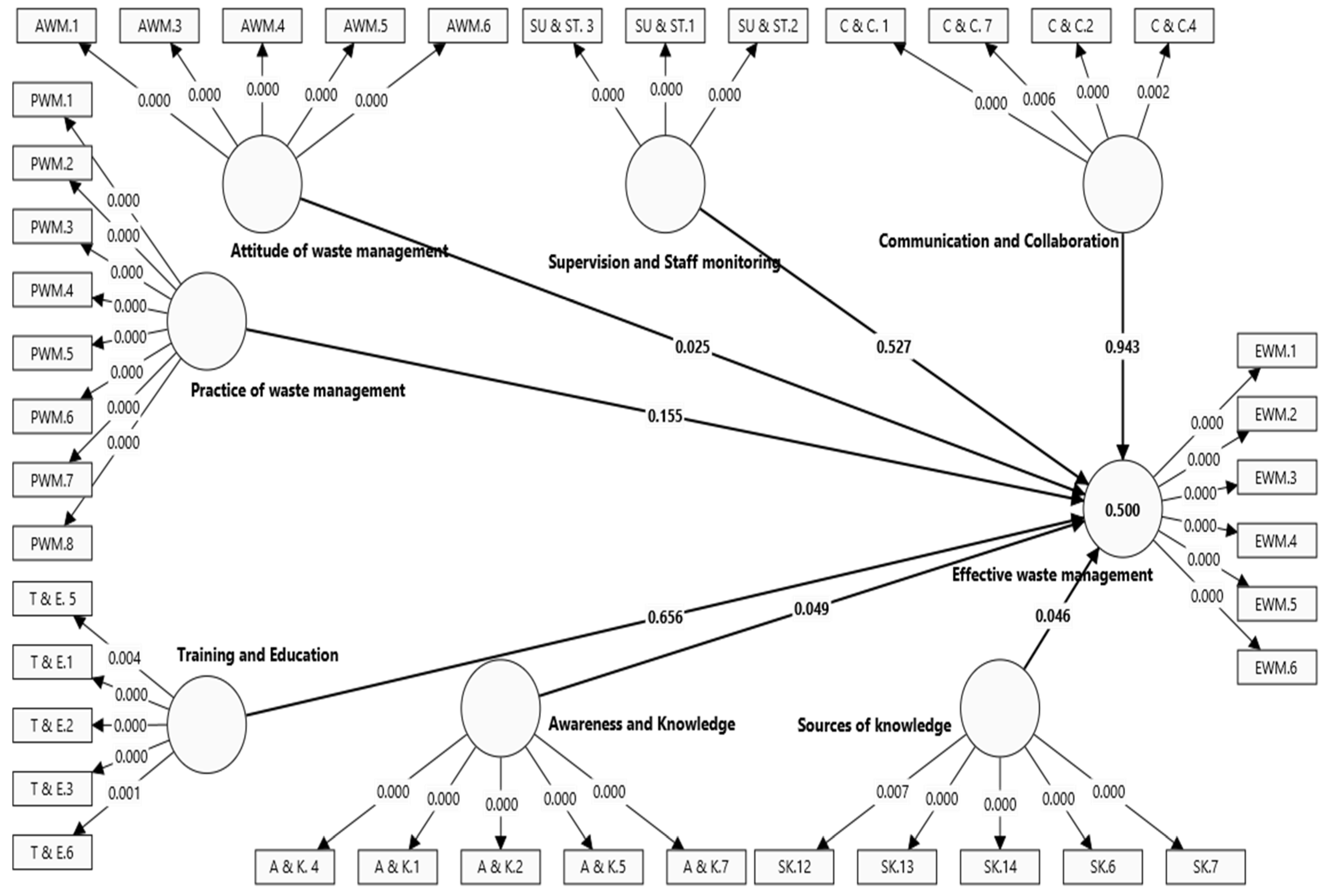

Figure 3.

—Construction of research model by bootstrapping.

Figure 3.

—Construction of research model by bootstrapping.

Structural Model

The structural model was evaluated in the second phase of PLS. With bootstrapping, it was able to complete this stage. But before determining the outcomes of the hypothesis testing, this study looked at the p-value (Ahmad et al., 2021). The F2 and R2 were to be determined next. The variance inflation factor, or VIF, was employed to measure the collinearity problems. The table of hypotheses testing indicates that the predictor construct scores satisfy the VIF criteria of being less than 3 (Hair et al., 2019). The percentage of an endogenous variable’s variance that exogenous factors might account for was indicated by the R2 value (Ahmad et al., 2021). According to a general rule of thumb put forward by Henseler et al. (2009), R-squared values are considered moderate, weak, and significant, respectively, at 0.50, 0.25, and 0.75 (Haque et al. 2023; Hensele et al., 2009). The R2 value for EWM is 0.5%, suggesting that all exogenous variables account for 50% of the variation in Effective Waste Management among medical professionals in Bangladesh. The f-square table shows the amount of each predictor variable’s influence on the dependent variable. The f-square values aid in determining the relative relevance of each predictor factor in explaining the variance in the dependent variable. The standardized coefficients in the PLS-SEM and the path coefficients in the regression analysis were found to be similar. Hypotheses were evaluated using β values and tested with T-statistics. The bootstrapping technique was used to determine the hypothesis’s relevance (Haque et al., 2023). To determine the p-values for each relationship between the endogenous latent variable (effective medical waste management) and the exogenous latent variables (SK = sources of knowledge, A & K = awareness and knowledge, T & E = training and education, C & C = communication and collaboration, SU & ST = supervision and staff monitoring, PWM = practice of waste management, AWM = attitude of waste management), bootstrapping with 5000 sub-samples was employed. The T-statistics, R2 values and p values for each of the endogenous latent variables from the model analysis are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Structural Model Analysis Results (Hypothesis Testing).

Table 4.

Structural Model Analysis Results (Hypothesis Testing).

| Variables |

β Value |

Mean |

Standard Deviation (STDEV) |

T Statistics (|O/STDEV|) |

P Values |

F2

|

R2

|

Decision |

| AWM > EWM |

0.324 |

0.322 |

0.145 |

2.236 |

0.025 |

0.13 |

0.5 |

Supported |

| AK > EWM |

0.2 |

0.203 |

0.101 |

1.971 |

0.049 |

0.042 |

|

Supported |

| CC > EWM |

-0.007 |

-0.02 |

0.103 |

0.072 |

0.943 |

0 |

|

Rejected |

| PWM > EWM |

0.132 |

0.134 |

0.093 |

1.423 |

0.155 |

0.023 |

|

Rejected |

| SK > EWM |

0.26 |

0.279 |

0.131 |

1.993 |

0.046 |

0.102 |

|

Supported |

| SUST > EWM |

0.047 |

0.05 |

0.074 |

0.633 |

0.527 |

0.003 |

|

Rejected |

| TE > EWM |

0.03 |

0.031 |

0.067 |

0.445 |

0.656 |

0.001 |

|

Rejected |

The fourth table provides information on the relationships between various factors and effective medical waste management. Specifically, there is no positive connection between training and education and effective medical waste management (β = 0.03, T = 0.445, p = 0.656), leading to the rejection of hypothesis H1. However, a positive relationship exists between awareness and knowledge and effective medical waste management (β = 0.2, T = 1.971, p = 0.049), supporting hypothesis H2. Additionally, there is no positive relationship between communication and collaboration and effective medical waste management (β = -0.007, T = 0.072, p = 0.943), resulting in the rejection of hypothesis H3. Similarly, the data show no positive relationship between supervision and staff monitoring and effective medical waste management (β = 0.047, T = 0.633, p = 0.527), leading to the rejection of hypothesis H4. Moreover, there is no correlation between the practice of waste management and EWM (β = 0.132, T = 1.423, p = 0.155), so hypothesis H5 is rejected. Conversely, a positive relationship is observed between the attitude towards waste management and effective medical waste management (β = 0.324, T = 2.236, p-value = 0.025), supporting hypothesis H6. Finally, there is a correlation between the use of sources of knowledge and EWM (β = 0.26, T = 1.993, p-value = 0.046), supporting hypothesis H7. In summary, the study supports hypotheses H2, H6, and H7, indicating that awareness and knowledge, attitude towards waste management, and the use of sources of knowledge are positively related to effective medical waste management. However, hypotheses H1, H3, H4, and H5 are rejected, as training and education, communication and collaboration, supervision and staff monitoring, and the practice of waste management do not show a positive relationship with effective medical waste management.

The hypotheses were assessed for statistical significance in relation to effective medical waste management. Training and education (H1), communication and collaboration (H3), supervision and staff monitoring (H4), and waste management practice (H5) were all determined to have no substantial influence, and hence were rejected. In contrast, awareness and knowledge (H2), attitude toward waste management (H6), and utilization of sources of knowledge (H7) all had substantial positive associations with successful medical waste management, resulting in acceptance. These findings emphasize the significance of awareness, good attitudes, and credible information sources in improving medical waste management procedures.

Discussion

Bangladesh’s current population is 169.8 million (Haque et al., 2023). Bangladesh now has around 14,770 health-care institutions (Dihan et al., 2023; Rahman et al., 2020). Based to the (Dihan et al., 2023) research, Bangladesh would likely create 50,000 tons of medical waste in 2025, with 12,435 tons of hazardous waste. An empirical model was used to estimate that 1.25 kg/bed/day of medical waste will be generated in 2025. The calculations projected that a total of 82,553, 168.4, and 2300 tons of medical waste were created from the processing of Covid patients, test kits, and immunization from March 2021 to May 2022. Medical waste is hazardous and contagious (Hassan et al., 2008). A wide range of activities contribute to the production of medical waste. Currently, medical and general communities are concerned about MWM (Mugabi et al., 2018). EWM is vital for healthcare facilities. However, in the context of this study, Bangladesh, a developing nation, is a great place to gather and analyze data (Haque et al., 2023). Thus, this study was conducted on the multifaceted analysis of knowledge sharing, training, communication and attitudes for effective medical waste management. Thus, this study was conducted on the multifaceted analysis of knowledge sharing, training, communication and attitudes for effective medical waste management. Medical waste management is crucial issues for keeping our life safe and safety. Without the effective measures for waste management, we cannot keep ourselves safe from different types of contagious diseases; viruses, bacteria. Besides, knowledge sharing is crucial for medical waste management. So, the aim of this study is to identify a multifaceted analysis of knowledge sharing, training, communication and attitudes for effective medical waste management. We have found some important points by screening the whole study.

From this analysis, it is clear that there is a significant relationship between sources of knowledge and EWM. The β value of the relationship is 0.26 and the AVE is 0.36. The p value is 0.046. So it is accepted. To find out the sources of knowledge, the researchers asked a few respondents about their opinions. They mentioned that-

“Most of the knowledge related to waste management wegot from our senior colleagues and skilled staff. Besides, Prism occasionally organizes seminars on waste management. We have also acquired knowledge from there.” (R1)

“Waste management is an important issue (Abdelnabi, 2023). It is impossible to manage medical waste without knowledge. We gained some knowledge about medical waste management while studying nursing. But most of the knowledge we have acquired from our senior colleagues and skilled staff. Moreover, we have also acquired knowledge through face-to-face and seminar.” (R2)

According to the analysis, it is clear that there is no positive relationship between training and education and EWM. The β value of the relationship is 0.03 and the AVE is 0.456. The p value is 0.656. The p value is rejected. The researchers asked some respondents about their training and education. They mentioned that

“No training is given to us on medical waste management. Our supervisor taught us how to separate the waste and which waste to dispose of in which container.” (R3)

“No training is given us on medical waste management every year. But I have had training on MWM in the past. We learned how to use the series and where to dispose of the garbage throughout this training. Most of the cleaners in our hospitals are less educated.” (R4)

Our hospital organizes monthly seminars and annual training on waste management through various organizations. The most notable organization is Prism. Previously I have had technical training on medical waste management in the past. (R5)

From this analysis, it is clear that there is a positive relationship between awareness and knowledge and effective medical waste management. The β value of the relationship is 0.2 and the AVE is 0.437. The p value is 0.049. So it is accepted. For awareness and knowledge of waste management, the researchers asked some respondents about their opinions. They mentioned that

“We share knowledge on the risks of dealing with medical waste with my colleagues (Olaifa et al., 2018). We also share knowledge about hazard waste and non-hazard waste. The color coding of disposal bins/containers information, we share with my colleagues.” (R6)

“We share knowledge on the risks of improper medical waste management with my colleagues. Besides, we share knowledge on which colors to use while separating waste. This makes it simple to distinguish between hazardous and non-hazardous garbage.” (R7)

According to the analysis, it is clear that there is no positive relationship relation between communication and collaboration and EWM. The β value of the relationship is -0.007 and the AVE is 0.474. The P value is 0.943. So, the p value is rejected. The researchers asked some respondents about communication and collaboration. They mentioned that

“In my hospital, there is no open communication between the team leader and staff. Every employee in my clinic works together. We don’t regularly communicate with our colleagues to properly manage waste.”(R8)

According to the analysis, it is clear that there is no positive connection between supervision and staff monitoring and EWM. The β value of the relationship is 0.047 and the AVE is 0.504. The p value is 0.527. Thus, the p value is rejected. The researchers asked some respondents about their supervision and staff monitoring. They mentioned that

“Our supervisor does not monitor us regularly. Because we handle all the work properly. But all the tools and resources we need to carry out my job responsibilities are provided by our supervisor (Alpern et al., 2013”(R9)

From this analysis, it is clear that there is a significant relationship between AWM and EWM. The β value of the relationship is 0.324 and the AVE is 0.489. The p value is 0.025. So it is accepted. The researchers asked some respondents about their attitude of waste management. They mentioned that

“Waste management is an important issue (Abdelnabi, 2023). Every staff member should wear hand gloves, clothes and musk regularly. These types of equipment reduce the risk of contracting infection. Besides, correct disposal, segregation and storage of waste are important for preventing infection transmission.”(R10)

“Medical waste management is a crucial issue for keeping our life safe and safety. That’s why, it should be handled with much more cautious. Besides, most of the cleaners in our hospitals are less educated. For this reason, I believe that all employees—especially cleaners—should receive MWM training”. (R11)

According to the analysis, it is clear that there is no connection between the PWM and EWM. The β value of the relationship is 0.132 and the AVE is 0.573. The p value is 0.155. So, it is rejected. The researchers asked some respondents about their practices of waste management practices. They mentioned that

“We only wear gloves, musk and cloth according to our specific needs. Most of the time, we don’t wear personal protective equipment. Besides, cleaners don’t clean containers every day.”(R13)

The researchers asked some respondents about knowledge sharing practices for waste management. They mentioned that

“We think that knowledge sharing plays a vital role in effective waste management. We always share knowledge with my colleagues. Because the more knowledge is shared, the more is learned. We share knowledge face- to- face.”(R14)

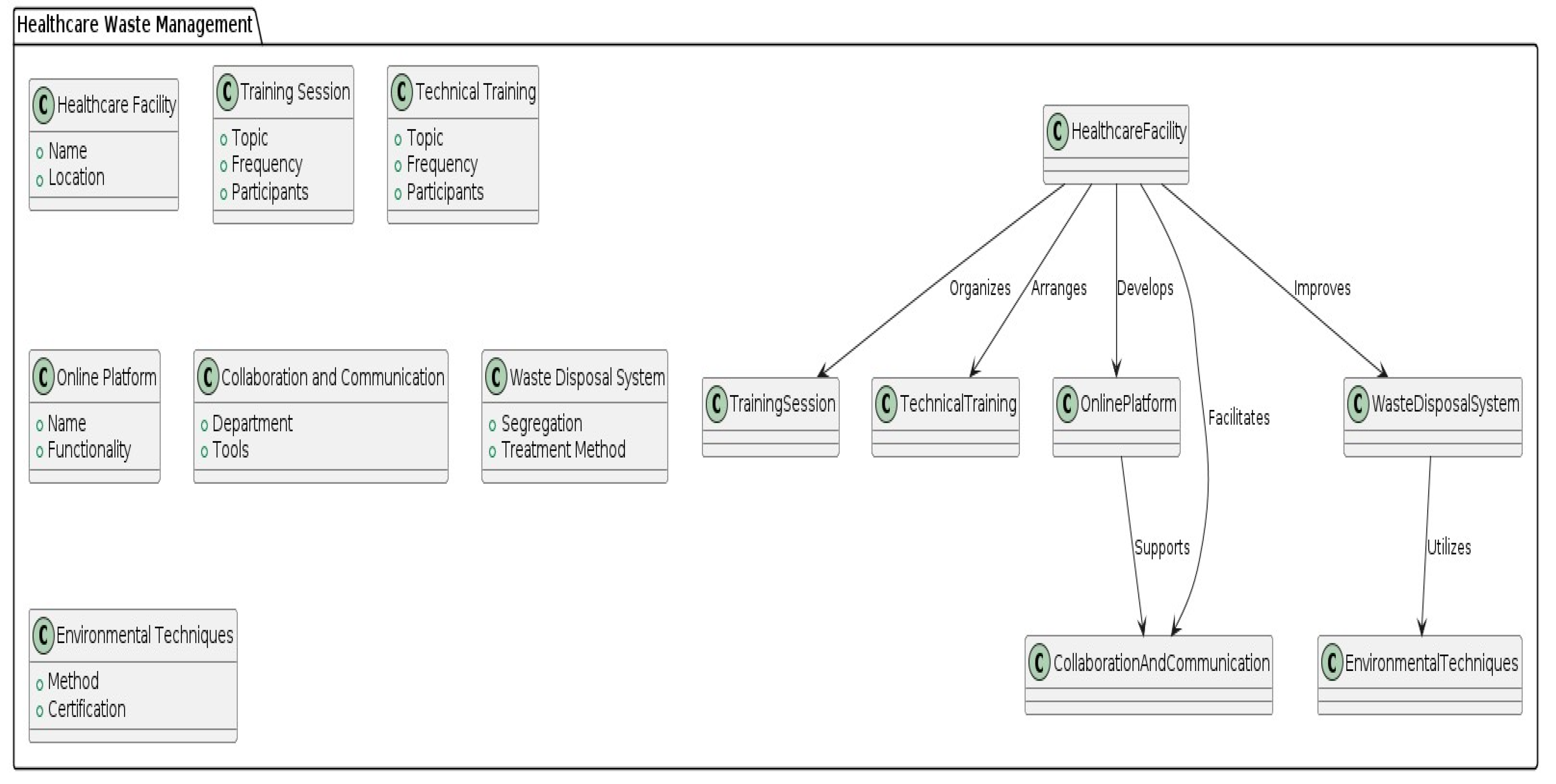

Recommendation

Implementing a comprehensive waste management approach in healthcare settings is vital for ensuring the safety of both staff and patients. This can be achieved by organizing monthly training sessions or workshops focused on waste management practices for medical staff, particularly cleaning staff, covering proper segregation, handling, storage, and disposal techniques for various types of medical waste. Additionally, technical training on medical waste management should be provided. Developing an online platform or forum will enable medical staff to share experiences, best practices, and innovative ideas related to waste management. Facilitating collaboration and communication between different departments within healthcare facilities is crucial for exchanging insights and strategies for waste management. Utilizing communication tools such as email, phone calls, and messaging apps ensures timely and efficient information exchange. Hospitals, clinics, and diagnostic centers should enhance their waste disposal systems by properly segregating medical waste at the point of generation, categorizing it into infectious, sharp objects, and non-hazardous. Environmentally appropriate techniques, including on-site treatments like autoclaving or incineration, as well as off-site disposal through certified waste management facilities, should be employed. By integrating regular training sessions, fostering collaboration, leveraging technology, and adhering to proper disposal techniques, healthcare facilities can mitigate risks and promote sustainable practices for the betterment of the community and the environment.

Figure 4.

General guidelines.

Figure 4.

General guidelines.

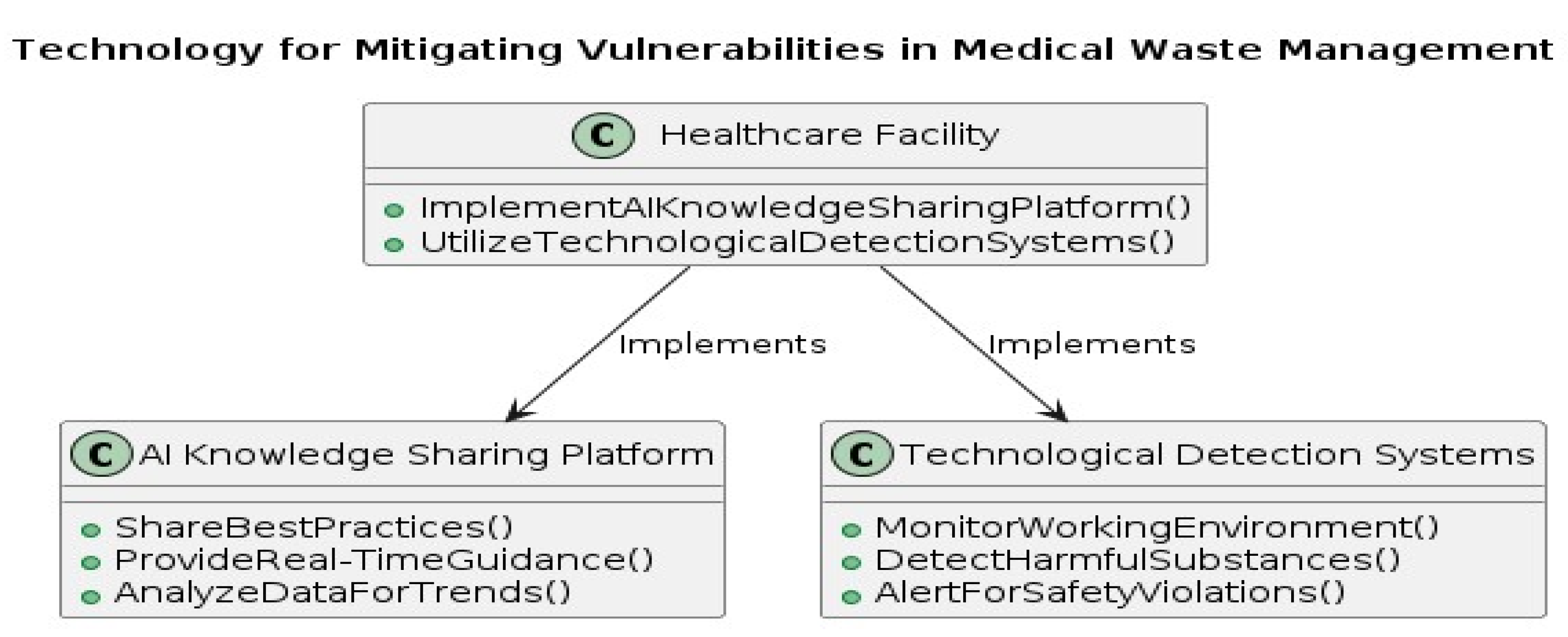

As an additional proposed recommendation, medical facilities in Bangladesh can improve their medical waste management practices through technology. Implementing an AI knowledge sharing platform would facilitate the dissemination of best practices, offer real-time guidance to healthcare professionals, and analyze data to identify trends and areas for improvement. Furthermore, the deployment of technological detection systems can continuously monitor the working environment for potential hazards, swiftly detect harmful substances, and promptly alert staff to safety violations. By integrating these technological solutions, healthcare facilities can bolster safety, efficiency, and regulatory compliance in medical waste management, ensuring the protection of both workers and the environment from potential risks.

Figure 5.

Proposed guidelines for EMWM by the usages of technology.

Figure 5.

Proposed guidelines for EMWM by the usages of technology.

Conclusion

Medical waste management is a critical issue for keeping our lives safe and secure. Knowledge sharing assists healthcare staff in identifying and mitigating hazards by providing knowledge on appropriate handling, segregation, and disposal methods. According to this study most respondents share their knowledge regarding proper medical waste management always and prefer face-to-face communication for sharing knowledge with others. The result shows that Sources of knowledge, awareness and knowledge and attitudes of waste management are crucial elements that affect the medical waste management. Various sources of knowledge, understanding of trash disposal and segregation, and staff attitudes toward waste management can all play a significant part in effective medical waste management. This result also shows that there are no relationships between communication and collaboration, practice of waste management, supervision and staff monitoring and training and education, with effective medical waste management. The rejection of the relationship between training/education of medical staff and effective waste management in Bangladesh stem from various factors: the majority of garbage handlers in Bangladesh come from poorer socioeconomic backgrounds, have larger families, and possess less education and experience (Som & Hossain, 2018). However, Lakbala & Lakbala (2013) academic attainment and MWM training. Poor waste management practices are caused by government institutions’ lack of expertise, education, and training are correlated (Khan et al., 2019). The rejection of the relationship between supervision and medical staff monitoring and effective medical waste management in Bangladesh stem from various factors: lack of proper initiatives, lack of proper supervision and lack of rules and regulation (Hossain et al., 2024). On the other hand, Olaifa et al. (2018) demonstrate that practice WM and EWM practices are strongly correlated. For every employee to have the proper knowledge, attitudes, and safe practices, they must get relevant and continuous in-service training in addition to adequate supervision and instruction in health care waste management. Gershon et al. (2000) also demonstrate that Supervisors and employees communicate openly with one another. Although these elements are necessary for effective medical waste management in other nations, they are not so important in Bangladesh’s perspective.

The study includes limitations that should be considered when evaluating its conclusions. For starters, its concentration on the northern half of Bangladesh brings geographical specificity, which may restrict the results’ application to other places. Second, there is a risk of selection bias if only medical workers from this location are selected, which may restrict the data’ relevance to the greater medical community in Bangladesh. Third, relying on self-reported data may add response bias, particularly in sensitive areas such as waste management methods. Finally, the study’s limited participant variety, which focused mostly on specialized healthcare occupations, may limit the findings’ applicability to other waste management professionals.

Future study should strive to include a larger spectrum of healthcare professionals involved in waste management, such as physicians, pharmacists etc. Longitudinal research should be provided to better understand these relationships over time.

References

- Abdelnabi, Z. H. (2023). Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practicesof Healthcare Workers Regarding Medical Waste Management during the COVID-19 Era: The Case of Southern West Bank.

- Abdo, N. M., Hamza, W. S., & Al-Fadhli, M. A. (2019). Effectiveness of education program on hospital waste management. International Journal of Workplace Health Management, 12(6), 457-468. [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, M. K., & Al-Mukhtar, S. H. (2013). Assessment of medical waste management in Teaching hospitals in Mosul City. Mosul Journal of Nursing, 1(2), 40-44. [CrossRef]

- Abidi, S. S. R. (2007). Healthcare knowledge sharing: purpose, practices, and prospects. In Healthcare knowledge management: Issues, advances, and successes (pp. 67-86). New York, NY: Springer New York.

- Abramson, J. S., & Mizrahi, T. (1996). When social workers and physicians collaborate: Positive and negative interdisciplinary experiences. Social Work, 41(3), 270-281. [CrossRef]

- Adeyelure, T. S., Kalema, B. M., & Motlanthe, B. L. (2019). An Empirical Study of Knowledge Sharing: A Case of South African Healthcare System. Knowledge Management & E-Learning, 11(1), 114-128. [CrossRef]

- Adogu, P., Ubajaka, C., & Nebuwa, J. (2014). Knowledge and practice of medical waste management among health workers in a Nigerian general hospital. Asian J Sci Technol, 5(12), 833-838.

- Ahmad, A. R., Jameel, A. S., & Raewf, M. (2021). Impact of social networking and technology on knowledge sharing among undergraduate students. International Business Education Journal, 14(1), 1-16.

- Aishi, I., Malik, R., Baba, S. H., Bhat, B. A., Tariq, S., Rather, T. A., & Islam, M. A. (2020). Socio-economic Correlates of Attitude of Youth of Fishing Communities towards Fishing Occupation in Kashmir Valley. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. App. Sci, 9(10), 172-178. [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational behavior and human decision processes, 50(2), 179-211.

- Ajzen, I. (1985). From intentions to actions: A theory of planned behavior. In Action control: From cognition to behavior (pp. 11-39). Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg.

- Ajzen, I. (1980). Understanding attitudes and predictiing social behavior. Englewood cliffs.

- Akkajit, P., Romin, H., & Assawadithalerd, M. (2020). Assessment of knowledge, attitude, and practice in respect of medical waste management among healthcare workers in clinics. Journal of environmental and public health, 2020. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alam, M. Z., Islam, M. S., & Islam, M. R. (2013). Medical waste management: a case study on Rajshahi city corporation in Bangladesh. Journal of Environmental Science and Natural Resources, 6(1), 173-178. [CrossRef]

- Alexandris, K., Barkoukis, V., & Tsormpatzoudis, C. (2007). Does the theory of planned behavior elements mediate the relationship between perceived constraints and intention to participate in physical activities? A study among older individuals. European Review of Aging and Physical Activity, 4, 39-48. [CrossRef]

- Alpern, R., Canavan, M. E., Thompson, J. T., McNatt, Z., Tatek, D., Lindfield, T., & Bradley, E. H. (2013). Development of a brief instrument for assessing healthcare employee satisfaction in a low-income setting. PloS one, 8(11), e79053. [CrossRef]

- Asdaq, S. M. B., Alshrari, A. S., Imran, M., Sreeharsha, N., & Sultana, R. (2021). Knowledge, attitude and practices of healthcare professionals of riyadh, saudi arabia towards covid-19: a cross-sectional study. Saudi Journal of Biological Sciences, 28(9), 5275-5282. [CrossRef]

- Assegaff, S., & Dahlan, H. M. (2011, November). Perceived benefit of knowledge sharing: Adapting TAM model. In 2011 International Conference on Research and Innovation in Information Systems (pp. 1-6). IEEE.

- Assem, P. B., & Pabbi, K. A. (2016). Knowledge sharing among healthcare professionals in Ghana. VINE Journal of Information and Knowledge Management Systems, 46(4), 479-491.

- Attrah, M., Elmanadely, A., Akter, D., & Rene, E. R. (2022). A review on medical waste management: treatment, recycling, and disposal options. Environments, 9(11), 146. [CrossRef]

- Awodele, O., Adewoye, A. A., & Oparah, A. C. (2016). Assessment of medical waste management in seven hospitals in Lagos, Nigeria. BMC public health, 16(1), 1-11. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bar-Dayan, Y., Bogaiov, A., Boaz, M., Landau, Z., & Wainstein, J. (2014). Opinion and knowledge among hospital medical staff regarding diagnosis of diabetes and proper usage of a specific test tube for glucose analysis. International Journal of Clinical Practice, 68(2), 278-282. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bell, J., & Waters, S. (2018). Doing Your Research Project: A guide for first-time researchers. McGraw-hill education (UK).

- Biswas, A., Amanullah, A. S. M., & Santra, S. C. (2011). Medical waste management in the tertiary hospitals of Bangladesh: an empirical enquiry. ASA university review, 5(2), 149-158.

- Bozeman, B., Fay, D., & Slade, C. P. (2013). Research collaboration in universities and academic entrepreneurship: the-state-of-the-art. The journal of technology transfer, 38(1), 1-67. [CrossRef]

- Buluzi, M. S. (2022). Assessing adherence of hospital waste disposal management at Mangochi District Hospital (Doctoral dissertation, Kamuzu University of Health Sciences).

- Burns, N. J. (2017). Theory of planned behavior-based predictors of playing-related musculoskeletal disorders prevention practices (Doctoral dissertation, University of Alabama Libraries).

- Carmeli, A., Gelbard, R., & Reiter-Palmon, R. (2013). Leadership, creative problem-solving capacity, and creative performance: The importance of knowledge sharing. Human resource management, 52(1), 95-121. [CrossRef]

- Castaneda, D. I., & Durán, W. F. (2018). Knowledge sharing in organizations: Roles of beliefs, training, and perceived organizational support. Knowledge Management & E-Learning, 10(2), 148-162. [CrossRef]

- Castañeda, Z., & Ignacio, D. (2015). Knowledge sharing: The role of psychological variables in leaders and collaborators. Suma Psicológica, 22(1), 63-69.

- Chedid, M., Alvelos, H., & Teixeira, L. (2022). Individual factors affecting attitude toward knowledge sharing: an empirical study on a higher education institution. VINE Journal of Information and Knowledge Management Systems, 52(1), 1-17. [CrossRef]

- Chin, W. W. (2009). How to write up and report PLS analyses. In Handbook of partial least squares: Concepts, methods and applications (pp. 655-690). Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg.

- Chin, W. W. (1998). Commentary: Issues and opinion on structural equation modeling. MIS quarterly, vii-xvi.

- Congress, U. S. (1988). Issues in medical waste management-Background paper. OTA-BP-O-49). Washington, DC.: US Government Printing Office.

- Davidavičienė, V., Al Majzoub, K., & Meidute-Kavaliauskiene, I. (2020). Factors affecting knowledge sharing in virtual teams. Sustainability, 12(17), 6917. [CrossRef]

- Debrah, J. K., Vidal, D. G., & Dinis, M. A. P. (2021). Raising awareness on solid waste management through formal education for sustainability: A developing countries evidence review. Recycling, 6(1), 6. [CrossRef]

- Deress, T., Jemal, M., Girma, M., & Adane, K. (2019). Knowledge, attitude, and practice of waste handlers about medical waste management in Debre Markos town healthcare facilities, northwest Ethiopia. BMC research notes, 12, 1-7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Vries, R. E., Bakker-Pieper, A., & Oostenveld, W. (2010). Leadership= communication? The relations of leaders’ communication styles with leadership styles, knowledge sharing and leadership outcomes. Journal of business and psychology, 25, 367-380.

- Dihan, M. R., Nayeem, S. A., Roy, H., Islam, M. S., Islam, A., Alsukaibi, A. K., & Awual, M. R. (2023). Healthcare waste in Bangladesh: Current status, the impact of Covid-19 and sustainable management with life cycle and circular economy framework. Science of The Total Environment, 871, 162083. [CrossRef]

- Doylo, T., Alemayehu, T., & Baraki, N. (2019). Knowledge and practice of health workers about healthcare waste management in public health facilities in Eastern Ethiopia. Journal of community health, 44, 284-291. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eagly, A. H., & Chaiken, S. (1993). The psychology of attitudes. Harcourt brace Jovanovich college publishers.

- Elling, H., Behnke, N., Tseka, J. M., Kafanikhale, H., Mofolo, I., Hoffman, I., ... & Cronk, R. (2022). Role of cleaners in establishing and maintaining essential environmental conditions in healthcare facilities in Malawi. Journal of Water, Sanitation and Hygiene for Development, 12(3), 302-317. [CrossRef]

- Ellingson, L. L. (2002). Communication, collaboration, and teamwork among health care professionals. Communication research trends, 21(3).

- Elnaga, A., & Imran, A. (2013). The effect of training on employee performance. European journal of Business and Management, 5(4), 137-147.

- Exposto, L. A. S., Bakta, I. M., Wirawan, I. M. A., & Sujaya, I. N. (2022). Impact of Medical Waste Socialization on Medical Waste Management in Health Services Facilities. Journal of Asian Multicultural Research for Medical and Health Science Study, 3(3), 84-93. [CrossRef]

- Fagin, C. M. (1992). Collaboration between nurses and physicians: no longer a choice. Academic Medicine, 67(5), 295-303.

- Fauzi, M. A. (2022). Partial Least Square Structural Equation Modelling (PLS-SEM) in Knowledge Management Studies: Knowledge Sharing in Virtual Communities. Knowledge Management & E-Learning, 14(1), 103-124. [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, M., & Ajzen, I. (1977). Belief, attitude, intention, and behavior: An introduction to theory and research.

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of marketing research, 18(1), 39-50.

- Gershon, R. R., Karkashian, C. D., Grosch, J. W., Murphy, L. R., Escamilla-Cejudo, A., Flanagan, P. A., ... & Martin, L. (2000). Hospital safety climate and its relationship with safe work practices and workplace exposure incidents. American journal of infection control, 28(3), 211-221. [CrossRef]

- Golandaj, J. A., & Kallihal, K. G. (2021). Awareness, attitude and practises of biomedical waste management amongst public health-care staff in Karnataka, India. Journal of Humanities and Applied Social Sciences, 3(1), 49-63. [CrossRef]

- Haifete, A. N., Justus, A. H., & Iita, H. (2016). Knowledge, attitude and practice of healthcare workers on waste segregation at two public training hospitals. Eur J Pharm Med Res, 3(5), 674-689.

- Hair Jr, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., Sarstedt, M., Danks, N. P., & Ray, S. (2021). Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) using R: A workbook (p. 197). Springer Nature.

- Hair Jr, J. F., Sarstedt, M., Hopkins, L., & Kuppelwieser, V. G. (2014). Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM): An emerging tool in business research. European business review, 26(2), 106-121.

- Haque, M. A., Zhang, X., Akanda, A. E. A., Hasan, M. N., Islam, M. M., Saha, A., ... & Rahman, Z. (2023). Knowledge Sharing among Students in Social Media: The Mediating Role of Family and Technology Supports in the Academic Development Nexus in an Emerging Country. Sustainability, 15(13), 9983. [CrossRef]

- Haque, M. A., Zhang, X., Rahman, Z., Shoshi, K., & Armstrong, K. L. (2023). Exploring factors that influence the development of reading habits among users of a mobile library in Bangladesh. Annals of Library and Information Studies, 70(2), 85-98. [CrossRef]

- Haque, M. M., Biswas, A., Rahman, M. S., Zaman, K. B., & Asiquzzaman, M. (2021). Medical Waste Management System in Bangladesh Hospitals: Practices, Assessment and Recommendation. IOSR J Environ Sci Toxicol Food Technol, 15(6), 30-8.

- Hassan, M. M., Ahmed, S. A., Rahman, K. A., & Biswas, T. K. (2008). Pattern of medical waste management: existing scenario in Dhaka City, Bangladesh. BMC public health, 8, 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Heath, C., Svensson, M. S., Hindmarsh, J., Luff, P., & Vom Lehn, D. (2002). Configuring awareness. Computer Supported Cooperative Work (CSCW), 11, 317-347.

- Helmstädter, E. (2003). The institutional economics of knowledge sharing: Basic issues. In The Economics of Knowledge Sharing (pp. 11-38). Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sinkovics, R. R. (2009). The use of partial least squares path modeling in international marketing. In New challenges to international marketing (Vol. 20, pp. 277-319). Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

- Hossain, I., Haque, A. K. M., & Ullah, S. M. (2024). Assessing sustainable waste management practices in Rajshahi City Corporation: an analysis for local government enhancement using IoT, AI, and Android technology. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 1-19. [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M. R., Islam, M. A., & Hasan, M. (2021). Assessment of medical waste management practices: a case study in Gopalganj Sadar, Bangladesh. Eur. J. Med. Health Sci, 3(3), 62-71.

- Islam, A., & Biswas, T. (2014). Health system in Bangladesh: challenges and opportunities. American Journal of Health Research, 2(6), 366-374. [CrossRef]

- Jahan, I., Ahmed, M., & Faruquee, M. (2018). Knowledge, attitude and practices on bio medical waste management among the health care personnel of selected hospitals in Dhaka City. Int J Adv Res Technol [Internet].

- Johnson, K. M., González, M. L., Dueñas, L., Gamero, M., Relyea, G., Luque, L. E., & Caniza, M. A. (2013). Improving waste segregation while reducing costs in a tertiary-care hospital in a lower–middle-income country in Central America. Waste management & research, 31(7), 733-738. [CrossRef]

- Joseph, L., Paul, H., Premkumar, J., Paul, R., & Michael, J. S. (2015). Biomedical waste management: Study on the awareness and practice among healthcare workers in a tertiary teaching hospital. Indian journal of medical microbiology, 33(1), 129-131. [CrossRef]

- Karamitri, I., Talias, M. A., & Bellali, T. (2017). Knowledge management practices in healthcare settings: a systematic review. The International journal of health planning and management, 32(1), 4-18. [CrossRef]

- Kaniki, A. M., & Mphahlele, M. K. (2002). Indigenous knowledge for the benefit of all: can knowledge management principles be used effectively?. South African Journal of Libraries and Information Science, 68(1), 1-15. [CrossRef]

- Khan, B. A., Cheng, L., Khan, A. A., & Ahmed, H. (2019). Healthcare waste management in Asian developing countries: A mini review. Waste management & research, 37(9), 863-875. [CrossRef]

- Khan, B. A., Khan, A. A., Ahmed, H., Shaikh, S. S., Peng, Z., & Cheng, L. (2019). A study on small clinics waste management practice, rules, staff knowledge, and motivating factor in a rapidly urbanizing area. International journal of environmental research and public health, 16(20), 4044.

- KHAN, A., RATHOR, H. R., NAEEMULLAH, S., & AFZAL, S. (2013). Assessment of Knowledge, Attitude and Practices of Biomedical Waste Management among Staff of a Secondary Care Hospital in Narowal.

- Kim, H., Gibbs, J. L., & Scott, C. R. (2019). Unpacking organizational awareness: scale development and empirical examinations in the context of distributed knowledge sharing. Journal of Applied Communication Research, 47(1), 47-68. [CrossRef]

- Kinney, T. (1998). Knowledge management, intellectual capital and adult learning. Adult learning, 10(2), 2.

- Kız, C. T. F. Ö. M., Tinaztepe, C., Özer, F., Kiziloğlu, M., & Yozgat, U. (2012). The relationship between knowledge sharing and negative attitude against employee monitoring. Bilgi Ekonomisi ve Yönetimi Dergisi, 7(2), 93-102.

- Knickmeyer, D. (2020). Social factors influencing household waste separation: A literature review on good practices to improve the recycling performance of urban areas. Journal of cleaner production, 245, 118605. [CrossRef]

- Kofoworola, O. F. (2007). Recovery and recycling practices in municipal solid waste management in Lagos, Nigeria. Waste management, 27(9), 1139-1143. [CrossRef]

- Kothari, C. R. (2004). Research methodology: Methods and techniques. New Age International.

- Kovacich, J., Cook, C., Pelletier, V., & Weaver, S. (1997). Building interdisciplinary teams on-line in rural health care. Masterclass: learning, teaching and curriculum in taught master’s degrees, 137-148.

- Kumar, R., Samrongthong, R., & Shaikh, B. T. (2013). Knowledge, attitude and practices of health staff regarding infectious waste handling of tertiary care health facilities at metropolitan city of Pakistan. Journal of Ayub Medical College Abbottabad, 25(1-2), 109-112.

- Lakbala, P., & Lakbala, M. (2013). Knowledge, attitude and practice of hospital staff management. Waste management & research, 31(7), 729-732. [CrossRef]

- Lavoie, M. C., Yassi, A., Bryce, E., Fujii, R., Logronio, M., & Tennassee, M. (2010). International collaboration to protect health workers from infectious diseases in Ecuador. Revista Panamericana de Salud Pública, 27(5), 396-402. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. N. (2001). The impact of knowledge sharing, organizational capability and partnership quality on IS outsourcing success. Information & management, 38(5), 323-335. [CrossRef]

- Letho, Z., Yangdon, T., Lhamo, C., Limbu, C. B., Yoezer, S., Jamtsho, T., ... & Tshering, D. (2021). Awareness and practice of medical waste management among healthcare providers in National Referral Hospital. PloS one, 16(1), e0243817. [CrossRef]

- Lin, H. F. (2007). Knowledge sharing and firm innovation capability: an empirical study. International Journal of manpower, 28(3/4), 315-332. [CrossRef]

- Liu, F. C., Cheng, K. L., Chao, M., & Tseng, H. M. (2012). Team innovation climate and knowledge sharing among healthcare managers: mediating effects of altruistic intentions. Chang Gung Med J, 35(5), 408-419. [CrossRef]

- Malik, M. S., & Kanwal, M. (2018). Impacts of organizational knowledge sharing practices on employees’ job satisfaction: Mediating roles of learning commitment and interpersonal adaptability. Journal of Workplace Learning, 30(1), 2-17.

- Masilela, M. P. (2017). The development and institutionalisation of knowledge and knowledge sharing practices relating to the management of healthcare risk waste in a home-based care setting. Master of Education half-thesis. Grahamstown: Rhodes University.

- Mathur, V., Dwivedi, S., Hassan, M. A., & Misra, R. P. (2011). Knowledge, attitude, and practices about biomedical waste management among healthcare personnel: A cross-sectional study. Indian journal of community medicine: official publication of Indian Association of Preventive & Social Medicine, 36(2), 143.

- McCaffrey, R., Hayes, R. M., Cassell, A., Miller-Reyes, S., Donaldson, A., & Ferrell, C. (2012). The effect of an educational programme on attitudes of nurses and medical residents towards the benefits of positive communication and collaboration. Journal of advanced nursing, 68(2), 293-301. [CrossRef]

- McInerney, C. (2002). Knowledge management and the dynamic nature of knowledge. Journal of the American society for Information Science and Technology, 53(12), 1009-1018.

- McKay, M., Davis, M., & Fanning, P. (2009). Messages: The communication skills book. New Harbinger Publications.

- Mensah, M. N. A. (2022). An Evaluation of Monitoring and Supervision in the Junior High Schools Curriculum Delivery in Ghana. Open Journal of Educational Research, 326-334.

- Mensah, I., & Ampofo, E. T. (2021). Effects of managers’ environmental attitudes on waste management practices in small hotels in Accra. International Hospitality Review, 35(1), 109-126. [CrossRef]

- Metin, E., Eröztürk, A., & Neyim, C. (2003). Solid waste management practices and review of recovery and recycling operations in Turkey. Waste management, 23(5), 425-432. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohajan, H. K. (2019). Knowledge sharing among employees in organizations. Journal of Economic Development, environment and people, 8(1), 52-61. [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, S. M., Othman, N., hattem Hussein, A., & Rashid, K. J. (2017). Knowledge, attitude and practice of health care workers in Sulaimani health facilities in relation to medical waste management. Kurdistan Journal of Applied Research, 2(2), 143-150. [CrossRef]

- Mugabi, B., Hattingh, S., & Chima, S. C. (2018). Assessing knowledge, attitudes, and practices of healthcare workers regarding medical waste management at a tertiary hospital in Botswana: A cross-sectional quantitative study. Nigerian journal of clinical practice, 21(12), 1627-1638. [CrossRef]

- Muniandy, G., Anuar, M. M., Foster, B., Saputra, J., Johansyah, M. D., Khoa, T. T., & Ahmed, Z. U. (2021). Determinants of sustainable waste management behavior of Malaysian academics. Sustainability, 13(8), 4424. [CrossRef]

- Moore, D., Gamage, B., Bryce, E., Copes, R., Yassi, A., & BC Interdisciplinary Respiratory Protection Study Group. (2005). Protecting health care workers from SARS and other respiratory pathogens: organizational and individual factors that affect adherence to infection control guidelines. American journal of infection control, 33(2), 88-96. [CrossRef]

- Nadeem, M. (2010). Role of training in determining the employee corporate behavior with respect to organizational productivity: Developing and proposing a conceptual model. International Journal of Business and Management, 5(12), 206. [CrossRef]

- Nwankwo, C. (2018). Knowledge and practice of waste management among hospital cleaners. Occupational Medicine, 68(6), 360-363. [CrossRef]

- Olaifa, A., Govender, R. D., & Ross, A. J. (2018). Knowledge, attitudes and practices of healthcare workers about healthcare waste management at a district hospital in KwaZulu-Natal. South African Family Practice, 60(5), 137-145.

- Omotayo, F. O. (2015). Knowledge Management as an important tool in Organisational Management: A Review of Literature. Library Philosophy and Practice, 1(2015), 1-23.

- Ozder, A., Teker, B., Eker, H. H., Altındis, S., Kocaakman, M., & Karabay, O. (2013). Medical waste management training for healthcare managers-a necessity?. Journal of environmental health science and engineering, 11, 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Padmanabhan, K. K., & Barik, D. (2019). Health hazards of medical waste and its disposal. In Energy from toxic organic waste for heat and power generation (pp. 99-118). Woodhead Publishing.

- Pahlevan Sharif, S., She, L., Yeoh, K. K., & Naghavi, N. (2022). Heavy social networking and online compulsive buying: the mediating role of financial social comparison and materialism. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 30(2), 213-225. [CrossRef]

- Pangil, F., & Mohd Nasurddin, A. (2013). Knowledge and the importance of knowledge sharing in organizations.

- Panyaping, K., & Okwumabua, B. (2006). Medical waste management practices in Thailand. Life Science Journal, 3(2), 88-93.

- Patel, M., & Ragsdell, G. (2011). To share or not to share knowledge: an ethical dilemma for UK academics?. Journal of Knowledge Management and Practice.

- Pathirage, C. P., Amaratunga, D., & Haigh, R. (2008). The role of tacit knowledge in the construction industry: towards a definition.

- Quinn, M. M., Henneberger, P. K., Braun, B., Delclos, G. L., Fagan, K., Huang, V., ... & Zock, J. P. (2015). Cleaning and disinfecting environmental surfaces in health care: toward an integrated framework for infection and occupational illness prevention. American journal of infection control, 43(5), 424-434. [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M., Sarker, P., & Sarker, N. (2020). Existing scenario of healthcare waste management in noakhali, Bangladesh. Bangladesh Journal of Environmental Research, 11, 60-71.

- Ramokate, T. (2008). Knowledge and practices of doctors and nurses about management of health care waste at Johannesburg Hospital in the Gauteng Province, South Africa (Doctoral dissertation).