Submitted:

29 May 2024

Posted:

29 May 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

The Concept of Digital Addiction

Relationship between School Burnout and Digital Addiction

Associations of Sleep Quality with digital Addiction

Gender Differences in Digital Device Usage Patterns

Objective and Research Questions

Methods

Sample

Data Collection

Measuring Instruments

Data Analysis

Results

Students' Ratings of Digital Addiction Symptom Statements

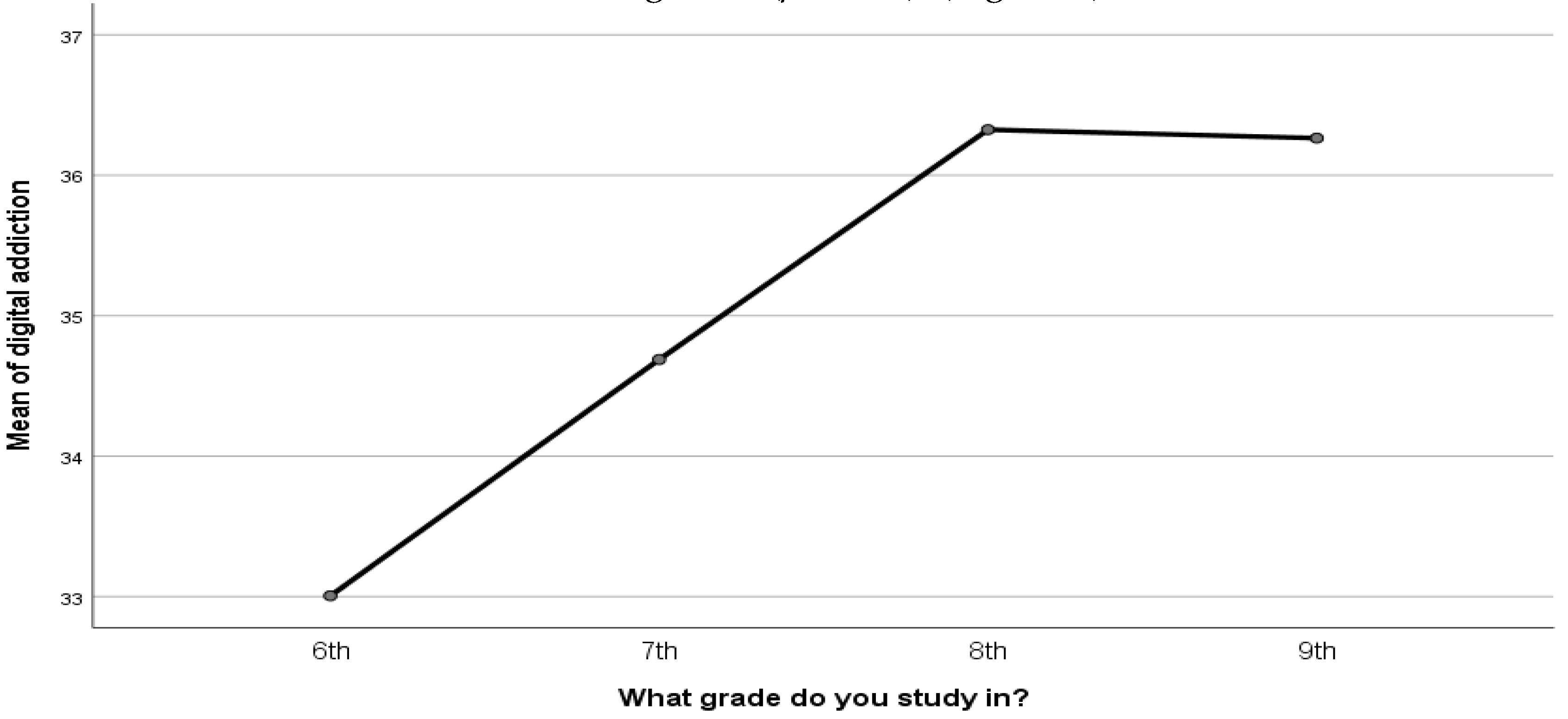

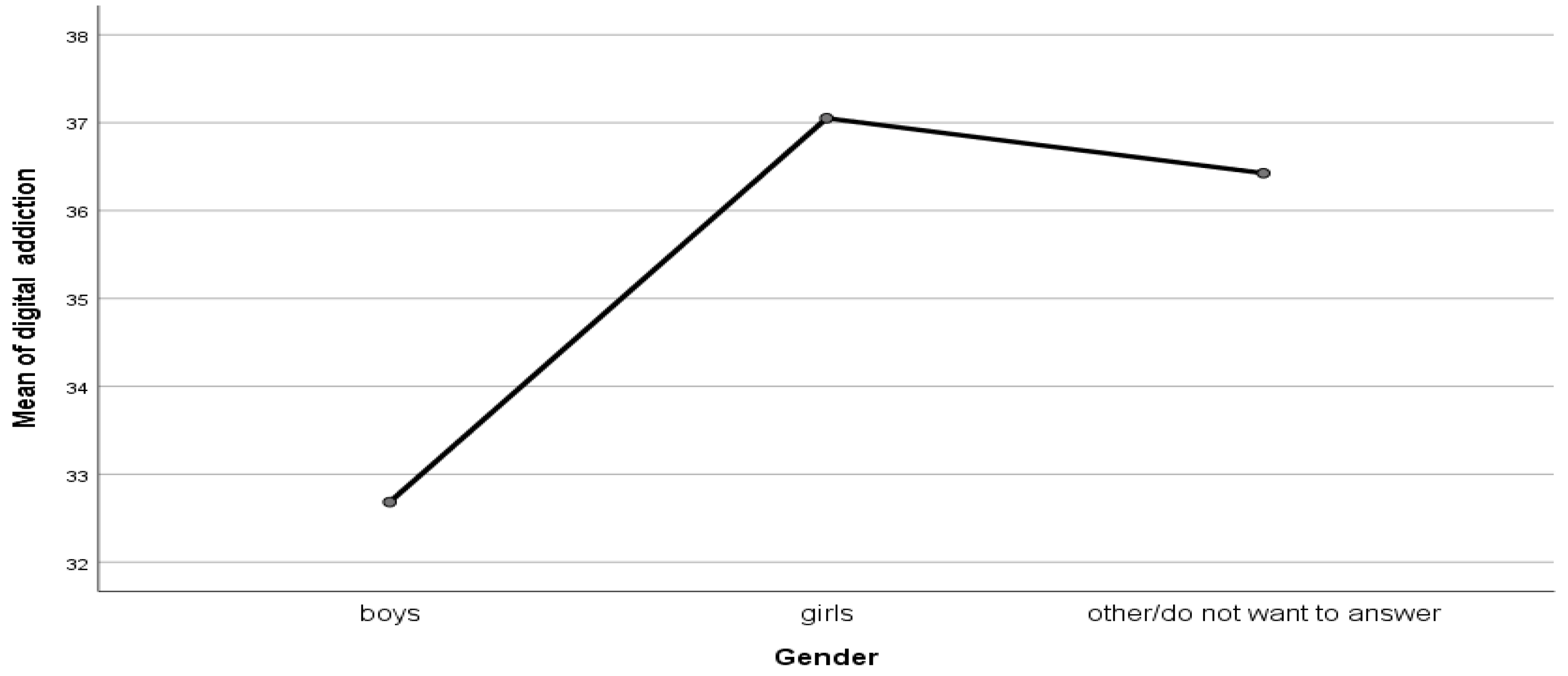

Students' Ratings of Digital Addiction Symptom Statements by Grade and Gender

Relations between Digital Addiction, School Burnout, Screen Time and Feeling Rested

Discussion and Conclusions

Limitations and Future Research Directions

References

- Al-Khani, A. M., Saquib, J., Rajab, A. M., Khalifa, M. A., Almazrou, A., & Saquib, N. (2021). Internet addiction in Gulf countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 10(3), 601-610. [CrossRef]

- Allcott, H., Gentzkow, M., & Song, L. (2022).Digital addiction. American Economic Review, 112(7), 2424-2463. [CrossRef]

- B., McAlaney, J., Skinner, T., Pleya, M., & Ali, R. (2020). Defining digital addiction; Almourad, M. B., McAlaney, J., Skinner, T., Pleya, M., & Ali, R. (2020). Defining digital addiction: Key features from the literature. Psihologija, 53(3), 237-253.

- Apray, A. (2012). Secondary School Burnout Scale (SSBS). Educational Sciences: Theory and Practice, 12(2), 782-787.

- Babic, M. J., Smith, J. J., Morgan, P. J., Eather, N., Plotnikoff, R. C., & Lubans, D. R. (2017). Longitudinal associations between changes in screen-time and mental health outcomes in adolescents. Mental Health and Physical Activity, 12, 124-131. [CrossRef]

- Bask, M., & Salmela-Aro, K. (2013). Burned out to drop out: exploring the relationship between school burnout and school dropout. European journal of psychology of education, 28, 511-528. [CrossRef]

- Bener, A., Al-Mahdi, H., & Bhugra, D. (2016). Lifestyle Factors and Internet Addiction among School Children. International Journal of Community & Family Medicine, 1(2). [CrossRef]

- Bruni, O., Sette, S., Fontanesi, L., Baiocco, R., Laghi, F., & Baumgarten, E. (2015). Technology Use and Sleep Quality in Preadolescence and Adolescence. [CrossRef]

- Cai, H., Xi, H. T., An, F., Wang, Z., Han, L., Liu, S.,... & Xiang, Y. T. (2021). The association between Internet addiction and anxiety in nursing students: a network analysis. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12, 723355. [CrossRef]

- Cash, H., D Rae, C., H Steel, A., & Winkler, A. (2012). Internet addiction: A brief summary of research and practice. current psychiatry reviews, 8(4), 292-298. [CrossRef]

- Chang, E., & Kim, B. (2020). School and individual factors on game addiction: A multilevel analysis. International Journal of Psychology, 55(5), 822-831. [CrossRef]

- Chang, F.-C., Chiu, C.-H., Chen, P.-H., Chiang, J.-T., Miao, N.-F., Chuang, H.-Y., & Liu, S. (2019). Children's use of mobile devices, smartphone addiction and parental mediation in Taiwan. Computers in Human Behavior, 93, 25-32. [CrossRef]

- Chen, L., Nath, R., & Tang, Z. (2020). Understanding the determinants of digital distraction: An automatic thinking behaviour perspective. Computers in Human Behavior, 104, 106195. [CrossRef]

- Chemnad, K., Aziz, M., Abdelmoneium, A. et al. (2023). Adolescents’ Internet addiction: Does it all begin with their environment? Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health 17, 87 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Chou, C., & Hsiao, M. C. (2000) Internet addiction, usage, gratification, and pleasure. experience: The Taiwan college students' case. Computers & Education, 35(1), 65-80. [CrossRef]

- Chung, T. W., Sum, S. M., & Chan, M. W. (2019). Adolescent internet addiction in Hong Kong: Prevalence, psychosocial correlates, and prevention. Journal of Adolescent Health, 64(6), S34-S43. [CrossRef]

- Ding, K., & Li, H. (2023). Digital Addiction Intervention for Children and Adolescents: A Scoping Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023 Mar 8;20(6):4777. [CrossRef]

- Dresp-Langley, B., & Hutt, A. (2022). Digital Addiction and Sleep. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(11), Art. 11. [CrossRef]

- Eickelmann, B., Casamassima, Gianna, Labusch, Amelie, Drossel, Kerstin, Sisask, Merike, Teidla-Kunitsõn, Gertha, Karatzogianni, Athina, Parsanoglou, Dimitris, Symeonaki, Maria, Gudmundsdottir, Greta, Holmarsdottir, Halla Bjørk, Mifsud, Louise, & Barbovschi, Monica (2022). Children and young people's narratives and perceptions of ICT in education in selected European countries complemented by perspectives of teachers and further relevant stakeholders in the educational context. [CrossRef]

- Fossum, I. N., Nordnes, L. T., Storemark, S., S., Bjorvatn, B., & Pallesen, S. (2014). The association between use of electronic media in bed before going to sleep and insomnia symptoms, daytime sleepiness, morningness, and chronotype. Behavioural sleep medicine, 12(5), 343-357. [CrossRef]

- https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.8.2019.32. [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, M. (1995, February). Technological addictions. In Clinical psychology forum (pp. 14-14). Division of Clinical Psychology of the British Psychol Soc. [CrossRef]

- Hale, L., & Guan, S. (2015). Screen time and sleep among school-aged children and adolescents: A systematic literature review. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 21, 50-58. [CrossRef]

- HITSA. (2020). Schools in Estonia have switched to digital remote learning 21 March 2020. https://www. hitsa.ee/about-us/news/estonia-has-switched-to-digital-remote-learning.

- Hou, H., Jia, S., Hu, S., Fan, R., Sun, W., Sun, T., & Zhang, H. (2012). Reduced striatal dopamine transporters in people with internet addiction disorder. Journal of Biomedicine and Biotechnology, 2012. [CrossRef]

- Honmore, V. M. (2023). Social Media Addiction, Loneliness, Sleep Quality and Gender among Adolescents. Indian Journal of Health & Wellbeing, 14(4), 473–476.

- International Classification of Diseases (ICD). (2020). Available at https://www.who.int/standards/classifications/classification-of-diseases.

- Joseph, R., & Hamiliton-Ekeke, J.-T. (2016). A Review of Digital Addiction: A Call for Safety Education. Journal of Education and E-Learning Research, 3(1), Art. 1. [CrossRef]

- Karacic, S., & Oreskovic, S. (2017). Internet Addiction Through the Phase of Adolescence: A Questionnaire Study. JMIR Mental Health, 4(2), e5537. [CrossRef]

- Karakose, T., Tülübaş, T., & Papadakis, S. (2022). Revealing the Intellectual Structure and Evolution of Digital Addiction Research: An Integrated Bibliometric and Science Mapping Approach. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(22), 14883. [CrossRef]

- Kesici, A., & Tunç, N. F. (2018). Investigating the Digital Addiction Level of the University Students According to Their Purposes for Using Digital Tools. Universal Journal of Educational Research, 6(2), 235-241. [CrossRef]

- Kim, K., Ryu, E., Chon, M.-Y., Yeun, E.-J., Choi, S.-Y., Seo, J.-S., & Nam, B.-W. (2006). Internet addiction in Korean adolescents and its relation to depression and suicidal ideation: A questionnaire survey. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 43(2), 185-192. [CrossRef]

- Levenson, J. C., Shensa, A., Sidani, J. E., Colditz, J. B., & Primack, B. A. (2016). The association between social media use and sleep disturbance among young adults. Preventive medicine, 85, 36-41. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.-B., Lau, J. T. F., Mo, P. K. H., Su, X.-F., Tang, J., Qin, Z.-G., & Gross, D. L. (2017). insomnia partially mediated the association between problematic Internet use and depression among secondary school students in China. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 6(4), 554-563. [CrossRef]

- Liao, C. H., & Wu, J. Y. (2022). deploying multimodal learning analytics models to explore the impact of digital distraction and peer learning on student performance. Computers & Education, 190, 104599. [CrossRef]

- Libman E., Fichten C., Creti L., Conrod K., Tran D.L., Grad R., Jorgensen M., Amsel R., Rizzo D., Baltzan M., Pavilanis ABailes S. (2016). Refreshing Sleep and Sleep Continuity Determine Perceived Sleep Quality. Sleep Disord. 2016:7170610. [CrossRef]

- Malak, M. Z., Khalifeh, A. H., & Shuhaiber, A. H. (2017). Prevalence of Internet Addiction and associated risk factors in Jordanian school students. Computers in Human Behavior, 70, 556-563. [CrossRef]

- Medic, G., Wille, M., & Hemels, M. E. (2017). Short-and long-term health consequences of sleep disruption. Nature and science of sleep, 151-161. [CrossRef]

- Meng, S.-Q., Cheng, J.-L., Li, Y.-Y., Yang, X.-Q., Zheng, J.-W., Chang, X.-W., Shi, Y., Chen, Y., Lu, L., Sun, Y., Bao, Y.-P., & Shi, J. (2022). Global prevalence of digital addiction in general population: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 92, 102128. [CrossRef]

- Mohan, A., Sen, P., Shah, C., Jain, E., & Jain, S. (2021). Prevalence and risk factor assessment of digital eye strain among children using online e-learning during the COVID-19 pandemic: Digital eye strain among kids (DESK study-1). Indian Journal of Ophthalmology, 69(1), 140-144. [CrossRef]

- Muidre, J. & Raudkivi, J. (2022). Use of digital tools in school in an inclusive education based on the example of 5th grade students in two primary schools. [Master thesis]. ETERA. https://www.etera.ee/s/ofIwwUK7Dk.

- Nagata JM, Cortez CA, Cattle & CJ, et al. (2022). Screen Time Use Among US Adolescents During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Findings from the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) Study. JAMA Pediatr, 176(1), 94–96. [CrossRef]

- Park, S., Holloway, S. D., Arendtsz, A., Bempechat, J., & Li, J. (2012). engaged in learning? A time-use study of within-and between-individual predictors of emotional engagement in low-performing high schools. Journal of youth and adolescence, 41, 390-401. [CrossRef]

- Peper, E., & Harvey, R. (2018). digital addiction: increased loneliness, anxiety, and anxiety. depression. NeuroRegulation, 5(1), 3-3. [CrossRef]

- Pies, R. (2009). Should DSM-V designate "Internet addiction" a mental disorder? Psychiatry (Edgmont), 6(2), 31.

- Raney, H., Testa, A., Jackson, D. B. K, Ganson, K.T., & Nagata, J.M. (2022). Associations Between Adverse Childhood Experiences, Adolescent Screen Time and Physical Activity During the COVID-19 Pandemic, Academic Pediatrics, Volume 22 (8), Pages 1294-12.

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations: Classic definitions and new directions. Contemporary educational psychology, 25(1), 54-67. [CrossRef]

- Saikia, A. M., Das, J., Barman, P., & Bharali, M. D. (2019). Internet addiction and its relationships with depression, anxiety, and stress in urban adolescents of Kamrup District, Assam. Journal of family & community medicine, 26(2), 108. [CrossRef]

- Salmela-Aro K., Kiuru N., Leskinen E., Nurmi J.-E. (2009). School Burnout Inventory (SBI): Reliability and validity. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 25(1), 48–57. [CrossRef]

- Salmela-Aro, K., Upadyaya, K., Hakkarainen, K., Lonka, K., & Alho, K. (2017). The Dark Side of Internet Use: Two Longitudinal Studies of Excessive Internet Use, Depressive Symptoms, School Burnout and Engagement Among Finnish Early and Late Adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 46(2), 343-357. [CrossRef]

- Santl, L., Brajkovic, L., & Kopilaš, V. (2022). Relationship between Nomophobia, Various Emotional Difficulties, and Distress Factors among Students. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education., 12(7), Art. 7. [CrossRef]

- Seema, R., Heidmets, M., Konstabel, K., & Varik-Maasik, E. (2022) Development and Validation of the Digital Addiction Scale for Teenagers (DAST). Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 40(2), 293-304. [CrossRef]

- Seema, R., & Varik-Maasik, E. (2023). Students' digital addiction and learning difficulties: shortcomings of surveys in inclusion. Frontiers in Education, 8, ARTN 1191817. [CrossRef]

- Sipal, R. F., & Bayhan, P. (2010). Preferred computer activities during school age: Indicators of internet addiction. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 9, 1085-1089. [CrossRef]

- Sukk, M., Soo, K. (2018). Preliminary results of the EU Kids Online Estonia 2018 survey. Kalmus, V., Kurvits, R., Siibak, A. (eds). Tartu: University of Tartu, Institute of Social Sciences. Available at: https://sisu.ut.ee/sites/default/files/euko/files/eu_kids_online_eesti_2018_raport.pdf.

- Time to Log Off (2016). Digital Addiction. Retrieved from https://www.itstimetologoff.com/digital-addiction/.

- Tomaszek, K., & Muchacka-Cymerman, A. (2020). Examining the relationship between student school burnout and problematic internet use. Educational Sciences: Theory and Practice, 20(2), 16-31. [CrossRef]

- Turel, Y., & Toraman, M. (2015). The relationship between Internet addiction and academic success of secondary school students. Anthropologist, 20.

- Turner, L., Bewick, B. M., Kent, S., Khyabani, A., Bryant, L., & Summers, B. (2021) When Does a Lot Become Too Much? A Q Methodological Investigation of UK Student Perceptions of Digital Addiction. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(21), Art. 21. [CrossRef]

- Väljas, J. (2023). Digital devices usage habits of Estonian primary school students based on the results of the Student Survey 2022. Tallinn University. [Master thesis]. ETERA. https://www.etera.ee/zoom/200233/view?page=1&p=separate.

- Walburg, V., Mialhes, A., & Moncla, D. (2016). Does school-related burnout influence. problematic Facebook use? Children and Youth Services Review, 61, 327-331. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H., Zhou, X., Lu, C., Wu, J., Deng, X., & Hong, L. (2011). Problematic Internet Use in High School Students in Guangdong Province, China. PLOS ONE, 6(5), e19660. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z., Yu, C., Zhang, W., Chen, Y., Zhu, J., & Liu, Q. (2017). School climate and adolescent aggression: A moderated mediation model involving deviant peer affiliation and sensation seeking. Personality and Individual Differences, 119, 301-306. [CrossRef]

- Weil L.G., Fleming S.M., Dumontheil I., Kilford E.J., Weil R.S., Rees G., Dolan R.J., Blakemore S.J. (2013). The development of metacognitive ability in adolescence. Conscious Cogn. 2013 Mar;22(1):264-71. [CrossRef]

- Weinstein, A. M. (2017). An update overview on brain imaging studies of internet gaming disorder. Frontiers in psychiatry, 8, 185. [CrossRef]

- Wiederhold, B. K., & Riva, G. (Eds.). (2012). Annual Review of Cybertherapy and Telemedicine 2012: Advanced Technologies in the Behavioral, Social and Neurosciences.

- Young, K. S. (1998). Internet addiction: The emergence of a new clinical disorder. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 1(3), 237-244. [CrossRef]

| Items | Mean | Std. Deviation |

| 1. I feel bored if I cannot use my digital device | 4.34 | 1.47 |

| 2. I feel uneasy when I do not know what my friends are saying on social media | 2.93 | 1.65 |

| 3. I am grumpy if I cannot use digital devices | 3.09 | 1.56 |

| 4. I end up spending more time using my digital device than initially planned | 4.45 | 1.64 |

| 5. As soon as I put my device away, I feel the urge to use it again | 3.38 | 1.61 |

| 6. I keep an eye on the digital device even when I talk to someone | 3.12 | 1.70 |

| 7. I use a digital device while eating | 3.36 | 1.84 |

| 8. I keep an eye on my digital device during lessons | 2.83 | 1.68 |

| 9. I play or chat on my device while walking on the street | 2.95 | 1.66 |

| 10. I play or chat on my device when in bed before falling asleep | 4.57 | 1.95 |

| Digital addiction summary score Mean | 35.02 | 11.28 |

| Digital addiction | School burnout | Screen time on school days | Screen time on weekends | Feeling refreshed in the morning | |

| Digital addiction | 1 | .45** | .41** | .40** | -.24** |

| School burnout | .45** | 1 | .25** | .25** | -.37** |

| Screen time on school days | .41** | .25** | 1 | .71** | -.18** |

| Screen time on weekends | .40** | .25** | .71** | 1 | -.18** |

| Feeling refreshed in the morning | -.24** | -.37** | -.18** | -.18** | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).