Introduction

In 2015, the United Nations (UN) adopted the Sustainable Development Goal 5 (SDG 5) of achieving gender equality and empowering all women and girls by 2030, to accelerate sustainable development [

1]. Empowerment, known as the “expansion in people’s ability to make strategic life choices in a context where this ability was previously denied to them” [

2], is at the heart of human development. Despite the considerable diversity in the literature on empowerment, women’s empowerment is a complex concept, and one of its features is decision-making power. A woman's ability to make decisions that influence her circumstances is an essential facet of empowerment and contributes to her general well-being.

For the World Bank, empowered women are critical to economic growth, and the cost of gender disparities is a serious threat to development, especially in the poorest countries [

3]. The contribution of women to society's development no longer needs to be demonstrated; countries that have empowered women to make meaningful life choices, act without constraints, and engage in any profession have witnessed significant development and growth [

4]. However, gender gaps and disparities persist worldwide, particularly in fragile countries with limited resources [

5].

Although the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) is committed to the 2030 Agenda, efforts to reverse gender disparities and empower women remain limited [

6,

7]. According to the Global Gender Gap Index, the country was ranked 140 out of 146 countries in 2023 [

5]. Nationwide, women's empowerment continues to be inadequate and characterized by significant gender disparity and gaps [

3,

8]. In 2022, a comprehensive report from the World Bank [

3] updated the 2013 DHS rates [

8] and indicated that only 15.1% of women had decision-making autonomy over their health, 21.1% regarding household expenses, and 16.6% for visits from relatives. The report identified “women’s lower access to certain key assets” as the driver of women's empowerment regardless of its dimensions and life sectors, but advocated for an extensive exploration using robust and advanced analytical methodologies to determine the context-specific factors that could determine women's empowerment [

3].

Up to the date of this study, little was known about these factors in DRC. However, Castro Lopes et al. [

9] in Mozambique and Abbas et al. [

10] in Pakistan reported that age, level of education, women's occupation, and wealth index impact women’s decision-making power. Belachew et al. [

11] in Ethiopia and Sougou et al. [

12] in Senegal also reported that age, educational level, religion, women's residence in urban areas, and media exposure determine autonomy in the use of contraceptives. These factors cannot be extrapolated to Congolese women who may have different social and environmental contexts.

Kinshasa is a town with a multifaceted urban–rural context in DRC. Studying the factors that determine women's empowerment in this specific context may provide input to a particular gender-oriented framework and policies for action in favor of Congolese women. We aimed to determine the factors associated with women's empowerment through decision-making in Kinshasa in the DRC.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Data Source

We conducted a secondary data analysis using data from the 2021 Performance Monitoring for Action (PMA2021) Survey conducted in Kinshasa between December 2021 and April 2022 [

13]. The PMA project is an initiative of USAID funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation to ensure the provision of quality data to guide family planning programs in 11 countries, including the DRC. It was designed as a longitudinal population-based cross-sectional panel, collecting information from the same women and households over time to track the progress of contraceptive use dynamics [

14]. PMA surveys followed a rigorous population sampling process to ensure urban and rural representativeness for each province. In the DRC, the project focused on two provinces, Kinshasa and Kongo Central [

13]. PMA surveys are two-stage cluster sampling design with clusters selected through probability-proportional-to-size sampling, with 35 households selected randomly within each cluster of which all women aged 15-49 were invited to participated. More details on PMA methodology can be found at

www.pmadata.org/data/survey-methodology.

Access to the 2021-onset Kinshasa PMA dataset was granted by the DRC’s Principal Investigator (P.A.) on request. The PMA project received ethical approvals from the Institutional Review Boards (IRB) at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health (#14590) in November 2021 and the Kinshasa School of Public Health (KSPH) (#ESP/CE/159B/2021) in October 2021. Additionally, we obtained ethical approval from the KSPH-IRB (ID: ESP/CE/098/2024) in April 2024 to conduct this present secondary data analysis on the de-identified data of the 2021 Kinshasa PMA onset database.

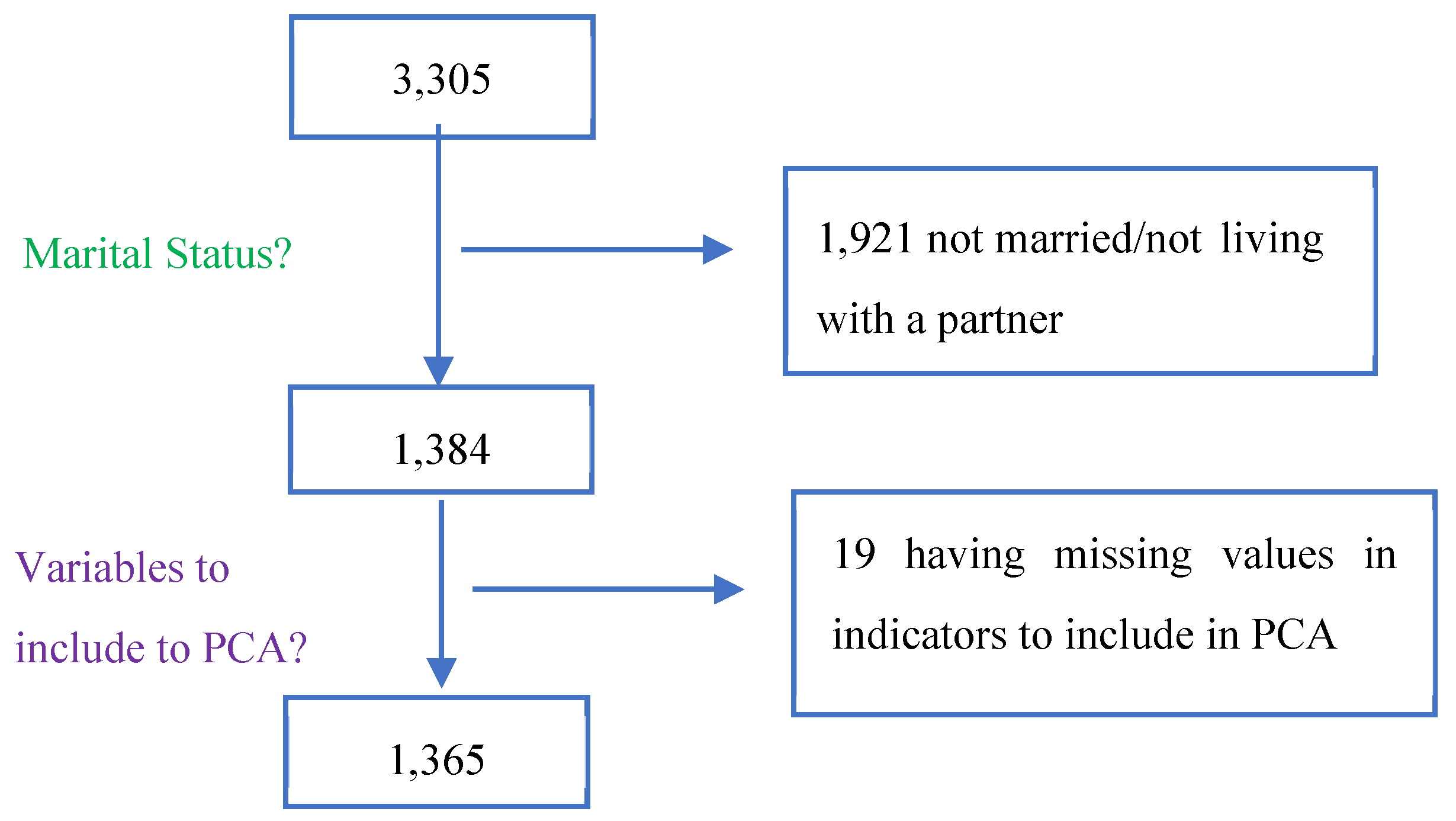

Of the 3,305 women aged 15-49 individuals included in the PMA dataset, we retained 1,365 married/ living with a partner woman in the present analysis (see

Figure 1). We employed the data concerning the household level, such as the wealth indicator calculated using asset ownership, household size, and other socio-demographic characteristics, as well as the individual female data, such as measures of education, type of marriage, family planning access, choice, and use, women’s empowerment, etc.

2.2. Outcome Variables

Empowerment items in the questionnaire

The PMA dataset and its questionnaire were screened, and 20 relevant questions/items related to women’s empowerment grouped under household decision making, partner influence on having sex, and contraception utilization, were identified. In this study, we used the definition of empowerment obtained from Kabeer on each item, where empowerment was defined as the capability of women to control and freely decide over one’s life.

Computing the Average Women’s Empowerment Index (aWEI)

To report prevalence of women’s empowerment, we computed a:

The average women’s empowerment index (aWEI) [

15,

16]. It is a standardized and composite index computed as averages scores from binary (1,0) items used to measure the potentiality of women to use their empowerment. It expressed as a constant for all women and can be clustered to group of items/individuals.

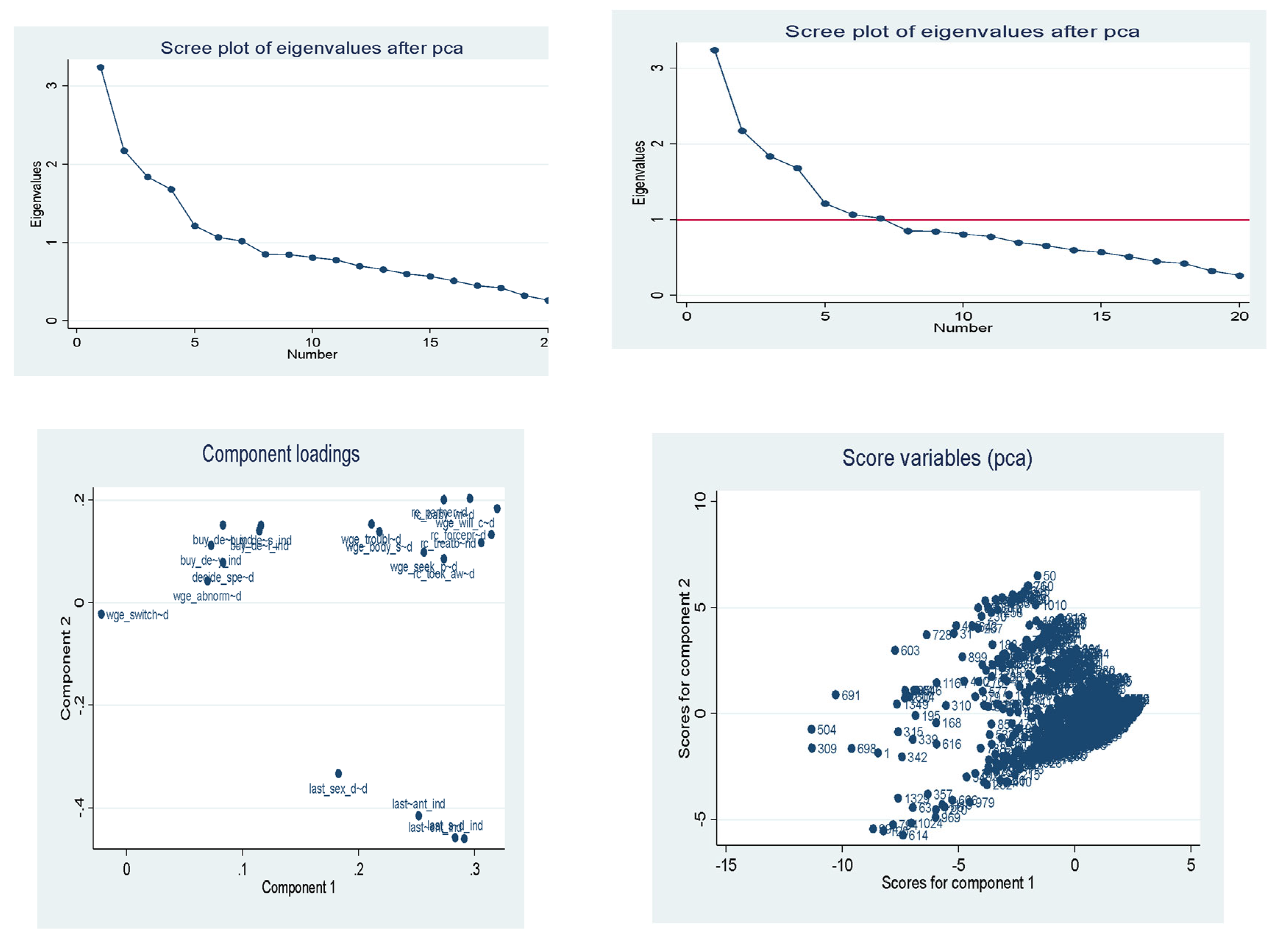

Empowerment item reduction using principal component analysis

To identify associated factors, we needed to transform items to uncorrelated outcomes variables for use of regression models. For that we needed to use a technique that reduce 20 items into a small number of uncorrelated variables. We therefore performed the Principal Component Analysis (PCA).

Depending on their initial codes, items from the dataset were re-coded into a 3-point scale (values of -1, 0, 1) to obtain the highest value to indicate a more significant level of women’s empowerment [

4]. This approach distinguishes, in a particular area, women who were empowered, those who had some level of empowerment, and those who were utterly disempowered.

Table A1 in the

Supplementary Materials details the selected empowerment items from the questionnaire, the initial codes, and the transformations performed.

After re-coding, the 20 empowerment items were reduced to principal component scores variables using the PCA. PCA has been applied in studies on women’s empowerment to avoid the ad hoc estimation of summary scores in which each indicator has an equal contribution [

4,

17,

18]. It allows the assessment of clustering patterns of empowerment indicators and the contribution (weight) for each component.

The first three significant components (an eigenvalue above 1) were retained from the scree plot of the PCA results. An orthogonal varimax rotation was applied after confirming no correlation between the retained components, an essential criterion for this rotation type [

19]. The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy was then applied to test how suitable the data were for PCA. The first three components represented the domains of women’s empowerment for Kinshasa and were named PC1 “

safety and free from threats”, PC2 “

sexuality control over sex/sexuality”, and PC3 “

household decision making”. These were considered as the outcome variables.

Transformation of PC score to binary outcomes

Each of the three component score variables was divided into quintiles from the most (5th quintile) to the least empowered women (1st quintile). The quintiles were then categorized into binary variables as the most vs least empowered women (all groups below the 5th quintile). Each binary variable served as an outcome variable for the three logistic regression models.

2.3. Independent Variables

We considered household socio-economic, demographic, and individual behavioral variables from the dataset to relate to the three empowerment components. For the socio-economic variable, we considered the wealth index constructed on a PCA basis of household ownership asset quintiles (poorest, poor, middle, rich, richest). The demographic variables included age (less or equal to 19, 20–29, 30–39, 40–49 years), education (no education, primary, secondary, university), professional status (working in the last 7 days yes or no), marital status (married or living with partner), religion (Catholic, Protestant, Islam, Kimbanguist, Others Christians, Africans, Other religion), parity, household size, savings for the future, mobile money accounts, health insurance location (slum, non-slum), and area of residence. Behavioral variables included access to media (internet or not).

2.4. Data Analysis

The categorical variables are displayed in the tables and figures and expressed in percentages. The aWEI was described prevalence of women’s empowerment using key empowerment items from the PMA survey and by location (slum or non-slum). The PCA was used to reduce asset ownership to a wealth score variable categorized into quintile variables. We also used PCA to reduce the 20 women’s empowerment items to principal components (PC) variables. The first three PCs, with eigenvalues > 1, were transformed into binary variables to serve as outcome variables in the three logistic regression models. We estimated the association between socio-economic, socio-demographic, and behavioral characteristics and each component's empowerment. Crude and adjusted odds ratios (OR) and respective 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were calculated. STATA version 17 was used for all data analyses.

3. Results

3.1. Socio-Demographic Characteristics

A total of 1,365 women were included in the present study. Table A2 shows the socio-demographic and behavioral characteristics. Women aged 30-39 years represented 40% of the total sample; meanwhile, the number of women aged 15-19 was lower, representing 1.8% of the total. Most women (91.5%) were educated at a secondary or tertiary level. Almost half of women (46.2%) were in a free union with a partner. Most women (79.1%) were residents of slum areas. Access to information on the internet was low, with only 35.3% of the women reporting having access to the internet.

3.2. Women Empowerment Domains and aWEI

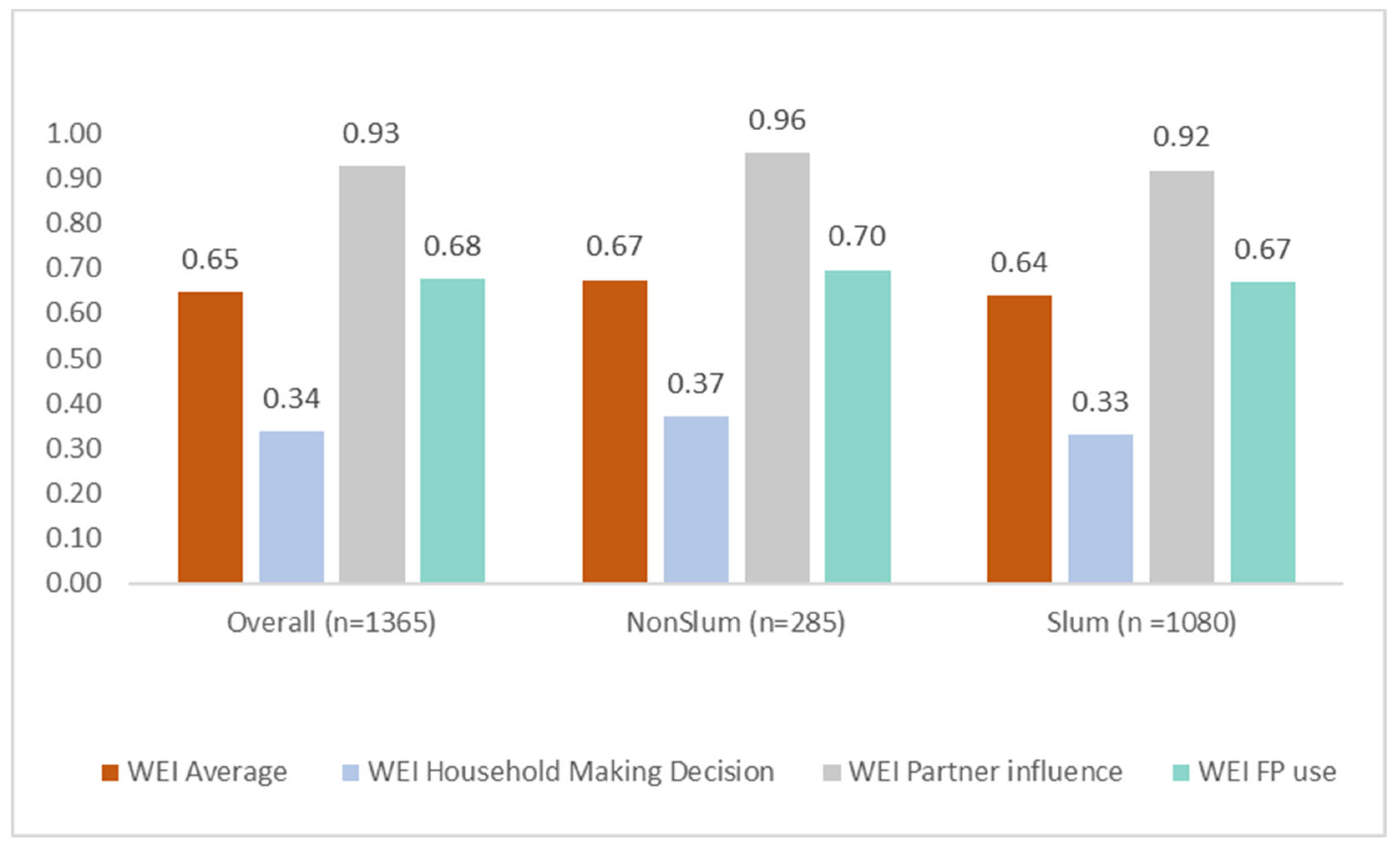

Figure 2 displays the proportion of empowered women regarding each item of the empowerment domain; meanwhile,

Figure 3 displays the aWEI for each domain of empowerment items and the overall aWEI across the location (slum or non-slum). The overall aWEI was estimated at 0.65, meaning that about 65% of women were able to achieve their empowerment potential. When stratifying this observation by domain, the household decision-making domain obtained a lower aWEI (0,34) and the partner influence domain obtained a higher aWEI (0.93).

3.3. Associated Factors to Women's Empowerment

In the

Supplementary Materials,

Table A1 presents the crude and adjusted ORs for the association between empowerment domains and women's socio-demographic, socio-economic, and behavioral characteristics.

Women’s age, level of education, marital status, parity, household size, having worked in the last seven days preceding the survey, having savings for the future, religion, having a mobile money account, their wealth quintile, and having health insurance were not associated with the empowerment PC1 of “safety and free from threats”. However, we noted a significant and positive association between access to the internet (aOR 1.83, 95% CI: 1.19, 2.83) and the component of safety and freedom from threats.

The empowerment PC2 “sexuality control over sex/sexuality” was significantly and positively associated with marital status (aOR: 1.96, 95% CI: 1.32, 2.89) and household size (aOR: 2.23, 95% CI: 1.05, 4.73). No association was noted between age, level of education, parity, having worked in the last seven days preceding the survey, having savings for the future, religion, having a mobile money account, their wealth quintile, having health insurance, access to the internet, and control of sexuality.

Women aged 40-49 (aOR: 2.02, 95% CI: 1.18, 3.46), marital status (aOR: 1.84, 95% CI: 1.23, 2.75), and internet access (aOR: 1.57, 95% CI: 1.02, 2.40) were significantly and positively associated with PC3 “household decision making”. We noted a significant, negative association between residence in slums (aOR: 0.66, 95% CI: 0.44, 0.99) and this empowerment PC. However, the level of education, parity, household size, having worked in the last seven days preceding the survey, having savings for the future, religion, having a mobile money account, their wealth quintile, and having health insurance were not associated with this PC.

4. Discussion

This study aimed to evaluate the degree of women’s empowerment and to determine the factors associated with women's empowerment in Kinshasa in 2021. We calculated the average women's empowerment index and estimated it at 0.65; this means that women are empowered to realize only 65% of their full potential and that the empowerment deficit amounts to almost 35%. This result is in line with the literature, which estimates the worldwide overall empowerment index at 0.607 [

15,

16]. The household decision making obtained the lowest WEI after stratifying by domain, at 0.34. Also proved in the literature is that participation in decision making has the lowest global WEI 0.413 [

15,

16].

In this study, three areas of empowerment were highlighted using the analysis method's main components, notably the absence of threats, control of sexuality, and participation in decision making. The associated factors identified were age, marital status, household size, internet access, and residence in the slum. This is similar to the results of other studies carried out in Africa [

4,

9,

21]. Our results show that the threat-free and decision-making components were influenced by internet access, with women having internet access being 1.83 times more likely not to suffer threats from their partners and 1.57 times more likely to make decisions than those who do not. Indeed, the literature also demonstrates a positive relationship between internet access and women's empowerment, because this provides them with access to information. Women who have access to the internet are open to the wider world. Thus, they can know their rights as human beings, especially as women, and what the law says about domestic violence, which allows significant awareness of their personal value, updates them on changes taking place in different areas, and allows them to acquire knowledge, which enables consistent decision making. Therefore, access to the internet is an essential determinant for women's empowerment. This conclusion is similar to the results of the research conducted by Castro Lopes and Aghazi [

9,

22].

Marital status and household size determine women's empowerment in controlling their sexuality. Women in a free union are 1.96 times more likely to be autonomous about their sexuality than married women. This could be explained by the fact that, because they are not married to their partners, they are not under their guardianship; therefore, they can freely decide about their sexuality. In addition, on a legal level, they do not have duties towards their partners; hence, they can freely decide on their sexuality [

23,

24]. we advance that awareness campaigns involving men should be put in place to work on the beliefs and norms that put him in a position of power over women when married.

Our results suggest a positive and significant relationship between household size and empowerment regarding sexual control; women living in households with sizes ranging from 6 to 8 members are 2.23 times more likely to be empowered. This might be explained by the fact that a larger household size increases the domestic burden, both financially and in terms of housework, which could lead to an imbalance for women; being assumed to be responsible for housework, they are able to devote little time to other activities and find themselves to be dependent. This can make them aware of all the burdens that impinge on their freedom, and thus they take control over their sexuality. Similar results were demonstrated in the studies of Kegnide and Soharwardi [

25,

26]. Nevertheless, Aghazi and Akram [

22,

27] found a negative relationship between household size and women's empowerment. This inconsistency can be explained by the different sample sizes and family systems. In fact, in the regions of Pakistan and Ethiopia, households are made up of several small families, which means women have little decision-making power, which is not the case in the city of Kinshasa.

Our results show that decision-making is influenced by being in the age group of 40-49. Women aged 40-49 are more likely to be autonomous in making decisions, whether for their health or within the household, than younger women. This could be explained by the fact that older women have more experience in several areas of life and gain awareness and trust from their partners over time. These results confirm those identified in the work of Abbas, Akram, and Sougou [

10,

12,

27]. Marital status also influences decision-making. Women in a free union are 1.84 times more likely to make decisions alone than married women. This result can be explained by the fact that the DRC is traditionally a patriarchal society in which the household decision-makers are men. Women are the responsibility of their husbands, who can, therefore, make decisions for them. However, women in free unions are not under the control of their husbands and are more autonomous in making their own decisions [

28,

29,

30]. The results of our study suggest that residence in a slum makes women less likely to be independent than those living in a non-slum. Indeed, women living in slums live in precarious conditions; they are not exposed to the media daily, which limits their access to information and their knowledge of the world, which are essential drivers of empowerment. They also experience difficulties in income-generating activities, making them dependent on their spouse, thus limiting their decision-making power [31].

The present study has strengths and weaknesses. The study's strength lies in the fact that it is the first to identify the factors associated with women's empowerment in Kinshasa, which is necessary to complete a study on this subject. The study used a large sample of women aged 15-49 from the PMA survey, allowing for the target population's representativeness. The PMA survey collected and measured three dimensions of women's empowerment, and the present secondary analysis used the PCA methods to account for the individual effects of items and avoid the ad hoc estimation of summary scores in which each indicator has an equal contribution. The clustering patterns from more than one dimension and 20-item empowerment indicators have contributed to the strengths of the present study. The logistic regression model used to determine associated factors was suitable for controlling confounding factors and checking for interaction.

As for the weaknesses of the study, it should be noted that the design of the PMA survey was cross-sectional, which means that it is impossible to establish a cause-and-effect relationship. To achieve this, a longitudinal analysis would be necessary, given that women's empowerment is a process of acquisition of equal power. In addition, information on women's empowerment in the PMA survey only targeted married women and those in union with a partner; other categories were not considered. Another weakness of this study is that it could present a classification bias, given that it classified women into two groups, the most empowered (as the fifth quintile) and less empowered women (from the first to the fourth quintiles), using the quintile variable. Another classification might find other proportions, but the classification we considered supports the scenario of high empower rank difference and has been used in the literature. This study was limited to the quantitative aspect based on the available data, which made it possible to define the different areas of empowerment; therefore, we believe that additional, more in-depth research, integrating a qualitative component, could elicit additional information concerning the indicators of women's empowerment. Comparing the two approaches, the aWEI estimation sums variables that seem to be related and are suitable for prevalence, while PCA allows better clustering of variables for accurate estimation of emergent women’s empowerment by domain and their associated factors by logistic regression. The two approaches were then complementary and critical to the objective of this study:

Table 2.

Determinants of empowered women.

Table 2.

Determinants of empowered women.

| |

PC1

named “safety and free from threats” |

PC2

named “sexuality control over sex/sexuality” |

PC3

named” household decision making” |

| |

cOR (95% CI) |

aOR (95% CI) |

cOR (95% CI) |

aOR (95% CI) |

cOR (95% CI) |

aOR (95% CI) |

|

Age (years) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 15-29 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

| 30-39 |

1.54 (1.12, 2.12) |

1.52 (0.93, 2.50) |

0.97 (0.71, 1.32) |

0.91 (0.58, 1.43) |

1.79 (1.29, 2.48) |

1.39 (0.87, 2.20) |

| 40-45 |

1.66 (1.16, 2.36) |

1.76 (0.99, 3.12) |

1.27 (0.91, 1.79) |

1.35 (0.80, 2.29) |

1.82 (1.28, 2.62) |

2.02 (1.18, 3.46) |

| Education |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Never or Primary |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

| Secondary |

1.20 (0.69, 2.07) |

0.84 (0.41, 1.71) |

0.89 (0.57, 1.38) |

1.21 (0.67, 2.18) |

1.12 (0.67, 1.89) |

0.94 (0.49, 1.79) |

| Tertiary |

2.57 (1.45, 4.57) |

1.16 (0.49, 2.72) |

0.33 (0.18, 0.59) |

0.93 (0.41, 2.11) |

1.83 (1.05, 3.19) |

1.42 (0.64, 3.17) |

| Marital status |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Married |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

| Living with a partner |

0.58 (0.44, 0.76) |

1.02 (0.67, 1.56) |

1.67 (1.28, 2.18) |

1.96 (1.32, 2.89) |

0.97 (0.74, 1.26) |

1.84 (1.23, 2.75) |

| Birth events |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Undelivered or first |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

| 2-4 deliveries |

1.12 (0.78, 1.59) |

0.98 (0.59, 1.63) |

1.22 (0.84, 1.78) |

1.56 (0.92, 2.63) |

1.39 (0.96, 2.01) |

1.33 (0.80, 2.19) |

| 5-7 deliveries |

0.82 (0.53, 1.29) |

0.77 (0.39, 1.48) |

1.66 (1.08, 2.57) |

1.64 (0.86, 3.11) |

0.91 (0.57, 1.45) |

0.81 (0.42, 1.56) |

| 8+ deliveries |

1.06 (0.46, 2.44) |

1.01 (0.32, 3.21) |

2.84 (1.36, 5.91) |

3.83 (1.42, 10.30) |

1.08 (0.45, 2.60) |

1.66 (0.58, 4.76) |

| Household size |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 1-2 members |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

| 3-5 members |

1.11 (0.78, 1.58) |

1.11 (0.75, 1.65) |

1.09 (0.78, 1.54) |

1.31 (0.89, 1.91) |

1.15 (0.82, 1.62) |

1.24 (0.85, 1.81) |

| 6-8 members |

1.19 (0.56, 2.57) |

1.37 (0.61, 3.11) |

1.52 (0.76, 3.06) |

2.23 (1.05, 4.73) |

1.22 (0.58, 2.55) |

1.35 (0.60, 3.04) |

| 9+ members |

0.42 (0.05, 3.35) |

0.39 (0.05, 3.51) |

0.82 (0.17, 3.82) |

0.35 (0.04, 3.08) |

0.84 (0.18, 3.93) |

0.43 (0.05, 3.62) |

| Work in the last seven days |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| No |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

| Yes |

|

1.04 (0.72, 1.52) |

|

0.81 (0.57, 1.15) |

|

0.84 (0.59, 1.19) |

| Have savings for the future |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| No |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

| Yes |

1.11 (0.84, 1.48) |

1.09 (0.73, 1.63) |

0.71 (0.52, 0.96) |

0.87 (0.58, 1.31) |

1.27 (0.96, 1.69) |

1.27 (0.86, 1.86) |

| Have mobile money accounts |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| No |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

| Yes |

2.06 (1.57, 2.69) |

1.42 (0.95, 2.12) |

0.68 (0.51, 0.91) |

0.89 (0.59, 1.35) |

1.56 (1.19, 2.05) |

1.19 (0.81, 1.77) |

| Internet access (exposure to media) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| No |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

| Yes |

2.18 (1.67, 2.86) |

1.83 (1.19, 2.83) |

0.68 (0.51, 0.91) |

1.11 (0.71, 1.73) |

1.66 (1.26, 2.17) |

1.57 (1.02, 2.40) |

| Have insurance health or be a member of a mutual health organization |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| No |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

| Yes |

1.04 (0.71, 1.52) |

0.73 (0.43, 1.23) |

0.69 (0.45, 1.05) |

0.92 (0.54, 1.59) |

1.34 (0.93, 1.93) |

0.91 (0.55, 1.50) |

| Religion |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Catholic |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

| Protestant |

0.91 (0.49, 1.68) |

0.85 (0.41, 1.76) |

1.51 (0.85, 2.69) |

1.32 (0.67, 2.60) |

1.26 (0.69, 2.29) |

1.17 (0.59, 2.34) |

| Other Christians |

0.85 (0.57, 1.27) |

0.79 (0.48, 1.29) |

0.95 (0.63, 1.42) |

0.90 (0.55, 1.47) |

0.97 (0.64, 1.47) |

0.98 (0.60, 1.61) |

| Kimbanguistes |

0.24 (0.07, 0.81) |

0.28 (0.06, 1.31) |

0.68 (0.28, 1.64) |

0.65 (0.25, 1.70) |

0.95 (0.42, 2.15) |

0.79 (0.29, 2.18) |

| Islamic |

1.02 (0.35, 2.95) |

1.77 (0.52, 6.01) |

|

|

0.40 (0.09, 1.79) |

0.54 (0.11, 2.72) |

| Africans (bundu, vuvamu, animist) |

1.93 (0.61, 6.10) |

4.64 (0.59, 36.47) |

1.05 (0.28, 3.98) |

1.02 (0.09, 11.13) |

1.60 (0.47, 5.41) |

4.69 (0.58, 38.04) |

| Other religion |

1.09 (0.61, 1.93) |

1.16 (0.57, 2.38) |

0.85 (0.46, 1.58) |

0.85 (0.42, 1.74) |

1.19 (0.66, 2.14) |

1.02 (0.49, 2.08) |

| Slum EA |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Non-slum |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

| Slum |

0.59 (0.44, 0.81) |

0.77 (0.51, 1.16) |

1.29 (0.92, 1.83) |

1.05 (0.67, 1.62) |

0.59 (0.44, 0.81) |

0.66 (0.44, 0.99) |

| Wealth quintile |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Lowest |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

| Lower |

1.68 (0.96, 2.94) |

1.49 (0.80, 2.81) |

0.61 (0.38, 0.96) |

0.75 (0.45, 1.26) |

0.94 (0.57, 1.56) |

0.93 (0.53, 1.63) |

| Middle |

1.49 (0.85, 2.63) |

1.12 (0.59, 2.14) |

0.72 (0.46, 1.11) |

0.85 (0.51, 1.41) |

1.03 (0.63, 1.69) |

0.89 (0.51, 1.56) |

| Higher |

2.76 (1.62, 4.71) |

1.59 (0.82, 3.07) |

0.61 (0.38, 0.97) |

0.79 (0.44, 1.42) |

1.46 (0.90, 2.36) |

0.97 (0.53, 1.78) |

| Highest |

3.48 (2.05, 5.92) |

1.40 (0.69, 2.87) |

0.57 (0.35, 0.92) |

0.89 (0.46, 1.75) |

2.01 (1.25, 3.22) |

1.08 (0.56, 2.08) |

5. Conclusions

Enhancing women’s access to information and communication (the internet) has the potential to help women reach different dimensions of their empowerment. Making resources available for them at home, at their place of business, or in a nearby area can increase the empowerment average. Results also advocate that awareness campaigns should involve men recognizing their position of power on the beliefs and social norms over married women.

Supplementary Materials

Table 1 in the Supplementary Materials details the selected empowerment items from the questionnaire, the initial codes, and the transformations performed.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.M. and D.M.; methodology, B.M., S.L., and P.A.; validation, P.A. and D.M.; formal analysis, A.M., B.M., S.L., and P.A.; investigation, A.M.; data curation, A.M. and B.M.; writing—original draft preparation, A.M.; writing—review and editing, all authors; supervision, D.M.; project administration/data source permission, P.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The data used in the present research were produced by The PMA project, an initiative of USAID funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. This secondary analysis received no external funding; the APC was funded by A.M.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The entire PMA project received ethical approvals from the Institutional Review Boards at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health (#14590) in November 2021 and the Kinshasa School of Public Health (#ESP/CE/159B/2021) in October 2021. Access to the 2021 onset Kinshasa PMA dataset was granted by the DRC’s PMA Principal Investigator (P.A.) upon request. De-identified data used for secondary data analysis received ethical approvals from the Kinshasa School of Public Health (ID: ESP/CE/098/2024) in April 2024 and were made available to us for analysis.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from all survey participants for publication.

Data Availability Statement

The data used for this publication and the DO file can be made available to the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The first author acknowledges the important support of scholarship received from USAID through the AFROHUN project to complete the Master's degree for which this research was conducted.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Distribution of women’s socio-demographic, socio-economic, and behavioral characteristics.

Table A1.

Distribution of women’s socio-demographic, socio-economic, and behavioral characteristics.

| |

N |

% |

| Age (years) |

|

|

| 15-19 |

25 |

1.83 |

| 20-29 |

454 |

33.26 |

| 30-39 |

546 |

40.00 |

| 40-49 |

340 |

24.91 |

|

Total

|

1,365 |

100.00 |

| Education |

|

|

| Never |

4 |

0.29 |

| Primary |

110 |

8.06 |

| Secondary |

971 |

71.14 |

| Tertiary |

280 |

20.51 |

|

Total

|

1365 |

100.00 |

| Marital status |

|

|

| Married |

734 |

53.77 |

| Not married but living with a partner |

631 |

46.23 |

|

Total

|

1365 |

100.00 |

| Ever birth |

|

|

| No |

76 |

5.57 |

| Yes |

1289 |

94.43 |

|

Total

|

1365 |

100.00 |

| Birth events |

|

|

| Undelivered or first |

255 |

19.78 |

| 2-4 deliveries |

732 |

56.79 |

| 5-7 deliveries |

263 |

20.40 |

| 8+ deliveries |

39 |

3.03 |

|

Total

|

1289 |

100.00 |

| Household size |

|

|

| 1-2 members |

640 |

66.53 |

| 3-5 members |

270 |

28.07 |

| 6-8 members |

41 |

4.26 |

| 9+ members |

11 |

1.14 |

|

Total

|

962 |

100.0 |

| Work in the last seven days |

|

|

| No |

638 |

46.74 |

| Yes |

726 |

53.19 |

|

Total

|

1364 |

100.00 |

| Have savings for the future |

|

|

| No |

960 |

70.33 |

| Yes |

405 |

29.67 |

|

Total

|

1365 |

100.00 |

| Have mobile money accounts |

|

|

| No |

883 |

64.69 |

| Yes |

482 |

35.31 |

|

Total

|

1365 |

100.00 |

| Internet access |

|

|

| No |

883 |

64.69 |

| Yes |

482 |

35.31 |

|

Total

|

1365 |

100.00 |

| Have insurance health or be a member of a mutual health organization |

|

|

| No |

1175 |

86.08 |

| Yes |

190 |

13.92 |

|

Total

|

1365 |

100.00 |

| Religion |

|

|

| Catholic |

170 |

13.01 |

| Protestant |

96 |

7.35 |

| Other Christians |

853 |

65.26 |

| Kimbanguistes |

47 |

3.60 |

| Islamic |

22 |

1.68 |

| Africans (bundu, vuvamu, animist) |

14 |

1.07 |

| Other religion |

105 |

8.03 |

|

Total

|

1307 |

100.00 |

| Slum EA |

|

|

| Non-slum |

285 |

20.88 |

| Slum |

1080 |

79.12 |

|

Total

|

1365 |

100.00 |

| Wealth quintile |

|

|

| Lowest |

223 |

23.16 |

| Lower |

194 |

20.15 |

| Middle |

201 |

20.87 |

| Higher |

178 |

18.48 |

| Highest |

167 |

17.34 |

|

Total

|

963 |

100.00 |

Principal components (eigenvectors)

| Variable |

Comp1 |

Comp2 |

Comp3 |

Unexplained |

| Who usually decides about large purchase for the HH? |

0.0829 |

0.1523 |

0.3890 |

0.6492 |

| Who usually decides about purchase for daily needs? |

0.0727 |

0.1124 |

0.3556 |

0.7231 |

| Who usually decides about your health care? |

0.1143 |

0.1411 |

0.4204 |

0.5898 |

| Who usually decides about buying clothes for yourself? |

0.1157 |

0.1516 |

0.4287 |

0.5691 |

| Who usually decides how your partner earnings will be used? |

0.0830 |

0.0791 |

0.2733 |

0.8269 |

| Has your partner treated you badly for wanting use FP? |

0.3053 |

0.1179 |

-0.1385 |

0.6325 |

| Has your partner Force you to be pregnant? |

0.3142 |

0.1336 |

-0.1785 |

0.583 |

| Has your partner said he would leave you if you don't get pregnant? |

0.2957 |

0.2040 |

-0.2908 |

0.4709 |

| Has your partner said he would have baby with someone else? |

0.2732 |

0.2017 |

-0.2863 |

0.5193 |

| Has your partner taken away your FP? |

0.2732 |

0.0863 |

-0.1163 |

0.7171 |

| Last time I had sex I didn't want to have sex at that time |

0.2516 |

-0.4154 |

0.0852 |

0.4064 |

| Last time I had sex I felt pressured to have sex then |

0.2830 |

-0.4580 |

0.1028 |

0.265 |

| Last time I had sex I was forced to have sex |

0.2909 |

-0.4597 |

0.0282 |

0.265 |

| Last time I had sex I felt a risk of physical violence |

0.1824 |

-0.3327 |

0.0522 |

0.6465 |

| If I use FP, my Partner may seek another spouse |

0.2560 |

0.0994 |

-0.0630 |

0.7589 |

| If I use FP, I may have trouble getting pregnant next time I want |

0.2109 |

0.1541 |

0.0715 |

0.7949 |

| If I use FP, there will be conflict in my relation |

0.3192 |

0.1844 |

0.0424 |

0.5927 |

| If I use FP, my children will not be born normal |

0.0696 |

0.0434 |

0.0498 |

0.9756 |

| If I use FP, my body may experience sides effects |

0.2177 |

0.1388 |

0.1458 |

0.7655 |

| I can decide to switch from one FP to another |

-0.0217 |

-0.0215 |

0.0039 |

0.9974 |

Principal components (eigenvectors)

| Variable |

Comp1 |

Comp2 |

Comp3 |

Unexplained |

| Who usually decides about large purchase for the HH? |

|

|

0.3890 |

0.6492 |

| Who usually decides about purchase for daily needs? |

|

|

0.3556 |

0.7231 |

| Who usually decides about your health care? |

|

|

0.4204 |

0.5898 |

| Who usually decides about buying clothes for yourself? |

|

|

0.4287 |

0.5691 |

| Who usually decides how your partner earnings will be used? |

|

|

|

0.8269 |

| Has your partner treated you badly for wanting use FP? |

0.3053 |

|

|

0.6325 |

| Has your partner Force you to be pregnant? |

0.3142 |

|

|

0.583 |

| Has your partner said he would leave you if you don't get pregnant? |

|

|

|

0.4709 |

| Has your partner said he would have baby with someone else? |

|

|

|

0.5193 |

| Has your partner taken away your FP? |

|

|

|

0.7171 |

| Last time I had sex I didn't want to have sex at that time |

|

-0.4154 |

|

0.4064 |

| Last time I had sex I felt pressured to have sex then |

|

-0.4580 |

|

0.265 |

| Last time I had sex I was forced to have sex |

|

-0.4597 |

|

0.265 |

| Last time I had sex I felt a risk of physical violence |

|

-0.3327 |

|

0.6465 |

| If I use FP, my Partner may seek another spouse |

|

|

|

0.7589 |

| If I use FP, I may have trouble getting pregnant next time I want |

|

|

|

0.7949 |

| If I use FP, there will be conflict in my relation |

0.3192 |

|

|

0.5927 |

| If I use FP, my children will not be born normal |

|

|

|

0.9756 |

| If I use FP, my body may experience sides effects |

|

|

|

0.7655 |

| I can decide to switch from one FP to another |

|

|

|

0.9974 |

Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure of sampling adequacy

| Variable |

kmo |

| Who usually decides about large purchase for the HH? |

0.6680 |

| Who usually decides about purchase for daily needs? |

0.6507 |

| Who usually decides about your health care? |

0.6719 |

| Who usually decides about buying clothes for yourself? |

0.6665 |

| Who usually decides how your partner earnings will be used? |

0.6646 |

| Has your partner treated you badly for wanting use FP? |

0.6819 |

| Has your partner Force you to be pregnant? |

0.8064 |

| Has your partner said he would leave you if you don't get pregnant? |

0.6130 |

| Has your partner said he would have baby with someone else? |

0.6224 |

| Has your partner taken away your FP? |

0.6971 |

| Last time I had sex I didn't want to have sex at that time |

0.7750 |

| Last time I had sex I felt pressured to have sex then |

0.7279 |

| Last time I had sex I was forced to have sex |

0.7441 |

| Last time I had sex I felt a risk of physical violence |

0.7931 |

| If I use FP, my Partner may seek another spouse |

0.7925 |

| If I use FP, I may have trouble getting pregnant next time I want |

0.7403 |

| If I use FP, there will be conflict in my relation |

0.7703 |

| If I use FP, my children will not be born normal |

0.7308 |

| If I use FP, my body may experience sides effects |

0.7172 |

| I can decide to switch from one FP to another |

0.5230 |

| Overall |

0.7109 |

References

- Unies, N. Rapport Sur Les Objectifs Du Développement Durable. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kabeer, N. The Conditions And Consequences Of Choice: Reflections On The Measurement Of Women’s. UNRISD Discuss Pap [Internet] 1999, 30, 435–464. [Google Scholar]

- Group, W.B. Women’s Economic Empowerment In The Democratic Republic Of The Congo: Obstacles And Opportunities. World Bank Publications: Washington, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ewerling, F.; Lynch, J.W.; Victora, C.G.; Van Eerdewijk, A.; Tyszler, M.; Barros, A.J.D. The SWPER Index For Women’s Empowerment In Africa: Development And Validation Of An Index Based On Survey Data. Lancet Glob Heal [Internet] 2017, 5, E916–E923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Economic Forum. Insight Report [Internet]. World Economic Forum. 2023 1–641 P. Available online: https://www3.weforum.org/docs/wef_gggr_2023.pdf.

- RDCM Du, P. Rapport D’examen National Volontaire. Rapp D’Examen Natl Volont Des Object Développement Durable [Internet]. 2020. Available online: https://www.cd.undp.org/content/rdc/fr/home/library/rapport-d_examen-national-volontaire-des-odd.html.

- Le C, Level C, Plan I, Les GAPIII, Sexuelles V, Pays PG, Et Al. Commission Européenne 2025, 1–3.

- Ministères De La Santé Publique Et Du Plan (Rdcongo). Enquête Démographique Et De Santé (EDS-RDC). Meas DHS, ICF Int Rockville: Maryland, USA, 2014; pp. 1–668. [Google Scholar]

- Lopes, S.C.; Constant, D.; Fraga, S.; Osman, N.B.; Correia, D.; Harries, J. Socio-Economic, Demographic, And Behavioural Determinants Of Women’s Empowerment In Mozambique. Plos One 2021, 16, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Abbas, S.; Isaac, N.; Zia, M.; Zakar, R.; Fischer, F. Determinants Of Women’s Empowerment In Pakistan: Evidence From Demographic And Health Surveys, 2012–13 And 2017–18. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belachew, T.B.; Negash, W.D.; Bitew, D.A.; Asmamaw, D.B. Prevalence Of Married Women’s Decision-Making Autonomy On Contraceptive Use And Its Associated Factors In High Fertility Regions Of Ethiopia: A Multilevel Analysis Using EDHS 2016 Data. BMC Public Health [Internet] 2023, 23, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sougou, N.M.; Sougou, A.S.; Bassoum, O.; Lèye, M.M.M.; Faye, A.; Seck, I. Factors Associated With Women’s Decision-Making Autonomy For Their Health In Senegal. Sante Publique (Paris) 2020, 32, 381–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Performance Monitoring For Action (PMA): Democratic Republic Of Congo Geographie [Internet]. Available online: https://fr.pmadata.org/countries/democratic-republic-congo.

- Performance Monitoring For Action: About Us [Internet]. Available online: https://fr.pmadata.org.

- UNWOMEN. THE PATHS TO EQUAL EQUAL: Twin Indices On Women ’ S Empowerment New Twin Indices [Internet]. 2023. Available online: https://www.unwomen.org/en/resources.

- Oxfam, G.B. A ‘ How To ’ Guide To Measuring Women ’ S Empowerment. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Jolliffe, I. Principal Component Analysis. In International Encyclopedia Of Statistical Science; Lovric, M., Ed.; Springer Berlin Heidelberg [Internet]: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2011; pp. 1094–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, P. An Easy Guide To Factor Analysis. Taylor & Francis, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Dean, J. Choosing The Right Type Of Rotation In PCA And EFA. Shiken JALT Test Eval SIG Newsl 2009, 13, 20–25. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, X.; Fu, C.; Wang, Q.; He, Q.; Hee, J.; Takesue, R.; et al. Women’s Empowerment And Children’s Complete Vaccination In The Democratic Republic Of The Congo: A Cross-Sectional Analysis. Vaccines 2021, 9, 1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agazhi, Z.D. Determinants Of Women Empowerment In Bishoftu Town; Oromia Regional State Of Ethiopia. 2023, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirarahumu Maliyababa Emery. Les Concubins Ignorent La Loi Et La Loi Les Ignorent: Pertinence De Cette Maxime Au Xxième Siècle. 2019.

- Motifs, E.D.E.S. Loi Modifiant Et Complétant La Loi N° 015-2002 Portant Code Du Travail. 2016; 1–7.

- KEGNIDEER; VOUDOUHEF Facteurs Socio- Economiques Influençant L ’ Autonomisation Des Femmes En Milieu Rural Au Bénin Socio-Economic Factors Influencing The Empowerment Of Women In Rural Areas In Benin. 2023, 4, 455–476.

- Soharwardi, M.A.; Ahmad, T.I. Dimensions And Determinants Of Women Empowerment In Developing Countries. December 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Akram, N. Women’s Empowerment In Pakistan: Its Dimensions And Determinants. Soc Indic Res 2018, 140, 755–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakunga, S. République Démocratique Du Congo: Une Certaine Idée Du Feminisme. Cent Tricontinental [Internet]. 2015, pp. 1–5. Available online: https://www.cetri.be/img/pdf/edr_rdc.pdf.

- Perpetue MINDe La, S.K.-R. Les Violences Familiales Subies Par La Femme Et La Jeune Fille En Rdc. 2005.

- Julienne, F. Genre Et Parite En Rdcongo. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Group, W.B. Re-Awakening Kinshasa’s Splendor Through Targeted Urban Interventions. 2018. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).