Submitted:

29 May 2024

Posted:

30 May 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Exposure to Violence within the Family and Community as a Social-Environmental Risk Factor for School Bullying Perpetration

1.2. Self-Serving Cognitive Distortions as Individual Social-Cognitive Risk Factors for School Bullying Perpetration

1.3. Examining how the Cognitive Desensitization Process Could Link Exposure to Violent Contexts, Self-Serving Cognitive Distortions, and School Bullying Perpetration

1.4. The Current Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Attrition and Missing Data Analysis

2.4. Measures

2.4.1. Exposure to Domestic Violence

2.4.2. Exposure to Community Violence

2.4.3. Self-Serving Cognitive Distortions (CDs)

2.4.4. School Bullying Perpetration

2.4.5. Control Variables

2.5. Analytic Strategy

3. Results

3.1. Correlations among Study Variables

3.2. Cross-Lagged Panel Modeling

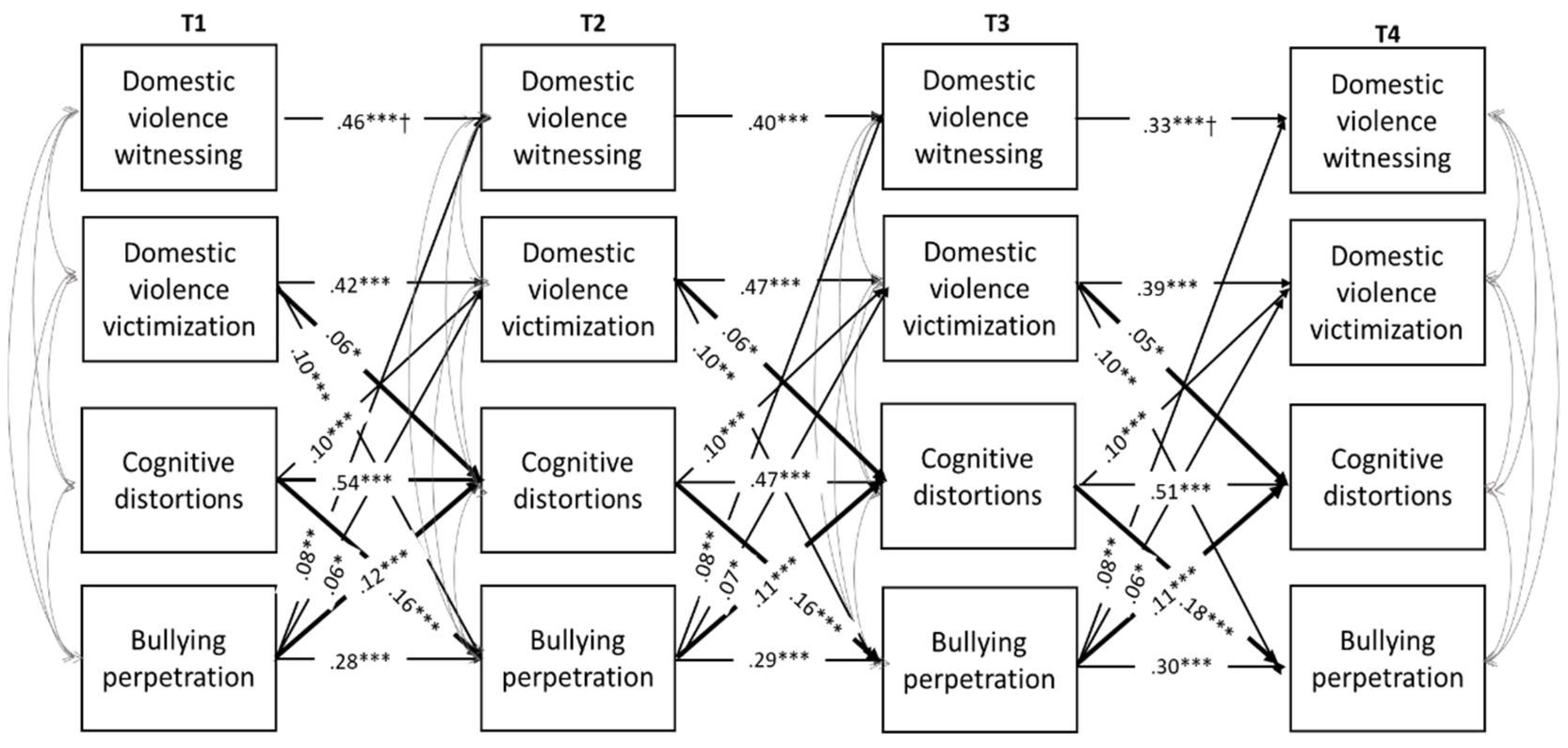

3.2.1. Exposure to Domestic Violence as a Witness and as a Victim

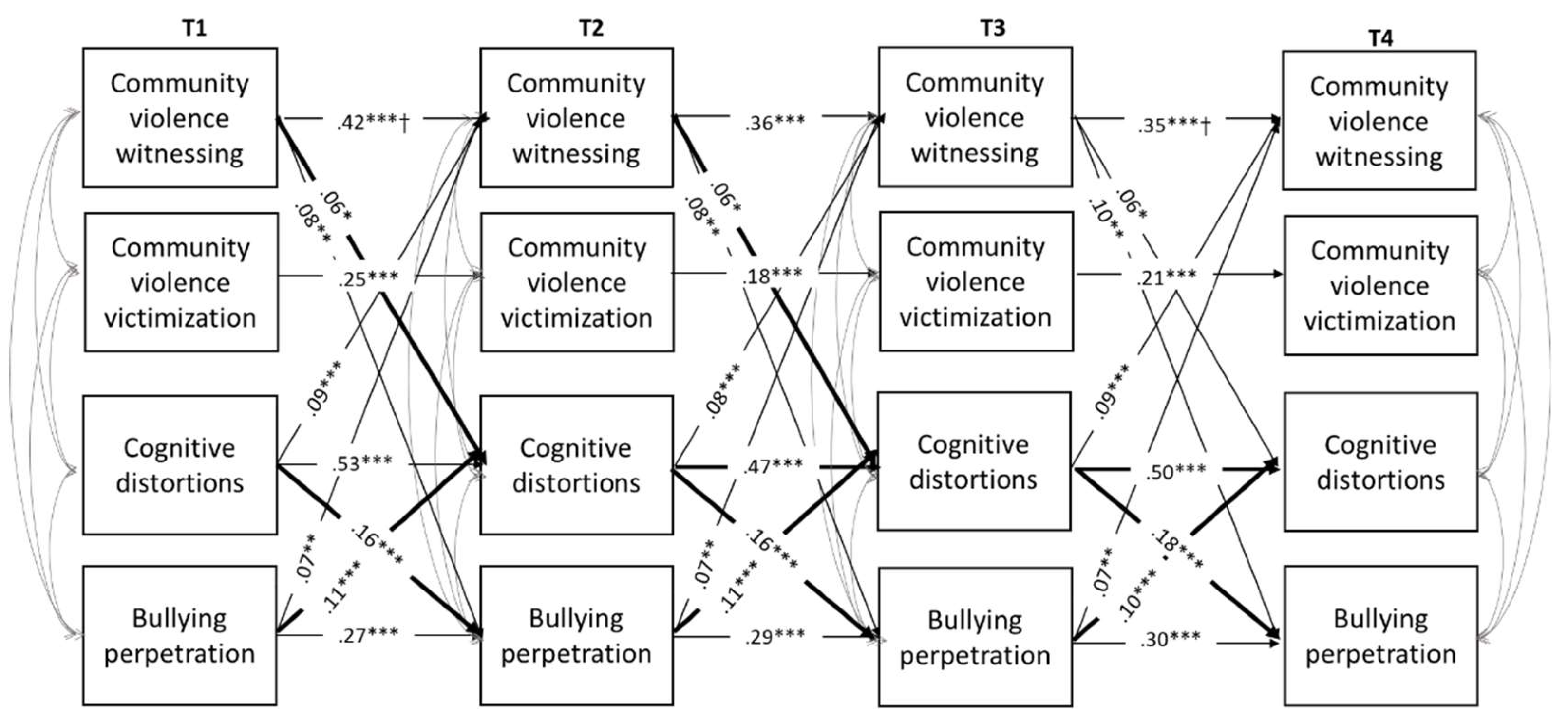

3.2.2. Exposure to Neighborhood/Community Violence as a Witness and as a Victim

3.2.3. Control Variables

4. Discussion

4.1. Social-Environmental Risk Factors for School Bullying Perpetration: The Role of Domestic and Community Violence Exposure

4.2. Pathways Linking Exposure to Domestic and Community Violence, Self-Serving Cognitive Distortions, and Bullying Perpetration: The Cognitive Desensitization Process

4.3. Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions and Practical Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hong, J.S.; Espelage, D.L. A Review of Research on Bullying and Peer Victimization in School: An Ecological System Analysis. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2012, 17, 311–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olweus, D. Bullying in School: What We Know and What We Can Do; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Menesini, E.; Salmivalli, C. Bullying in Schools: The State of Knowledge and Effective Interventions. Psychol. Health Med. 2017, 22, 240–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 2020.

- Hymel, S.; Swearer, S.M. Four Decades of Research on School Bullying: An Introduction. Am. Psychol. 2015, 70, 293–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrini, A.D.; Long, J.D. A Longitudinal Study of Bullying, Dominance, and Victimization during the Transition from Primary School through Secondary School. Br. J. Dev. Psychol. 2002, 20, 259–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. The Ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Nature and Design; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Espelage, D.L. Ecological Theory: Preventing Youth Bullying, Aggression, and Victimization. Theory Pract. 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. Ecological Models of Human Development. In The International Encyclopedia of Education. Oxford: Elsevier 1994, 2nd, 1643–1647.

- Dragone, M.; Esposito, C.; De Angelis, G.; Affuso, G.; Bacchini, D. Pathways Linking Exposure to Community Violence, Self-Serving Cognitive Distortions and School Bullying Perpetration: A Three-Wave Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, J.C. Moral Development and Reality: Beyond the Theories of Kohlberg, Hoffman, and Haidt, 3rd ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bacchini, D.; Affuso, G.; Aquilar, S. Multiple Forms and Settings of Exposure to Violence and Values. J. Interpers. Violence 2015, 30, 3065–3088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Li, L.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, X.; Zhang, Y.; Luo, X. Effects of Exposure to Domestic Physical Violence on Children’s Behavior: A Chinese Community-Based Sample. J. Child Adolesc. Trauma 2016, 9, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ehrensaft, M.K.; Cohen, P.; Brown, J.; Smailes, E.; Chen, H.; Johnson, J.G. Intergenerational Transmission of Partner Violence: A 20-Year Prospective Study. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2003, 71, 741–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, S.E.; Davies, C.; DiLillo, D. Exposure to Domestic Violence: A Meta-Analysis of Child and Adolescent Outcomes. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2008, 13, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Voisin, D.R.; Jacobson, K.C. Community Violence Exposure and Adolescent Delinquency. Youth Soc. 2016, 48, 33–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, C.; Bacchini, D.; Eisenberg, N.; Affuso, G. Effortful Control, Exposure to Community Violence, and Aggressive Behavior: Exploring Cross-lagged Relations in Adolescence. Aggress. Behav. 2017, 43, 588–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mrug, S.; Windle, M. Mediators of Neighborhood Influences on Externalizing Behavior in Preadolescent Children. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2009, 37, 265–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barriga, A.Q.; Hawkins, M.A.; Camelia, C.R.T. Specificity of Cognitive Distortions to Antisocial Behaviours. Crim. Behav. Ment. Heal. 2008, 18, 104–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gini, G. , Camodeca, M., Caravita, S. C. S., Onishi, A., & Yoshizawa, H. Cognitive Distortions and Antisocial Behaviour: An European Perspective. Konan Daigaku Kiyo. Bungaku-Hen (Journal Konan Univ. 2011, 161, 209–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helmond, P.; Overbeek, G.; Brugman, D.; Gibbs, J.C. A Meta-Analysis on Cognitive Distortions and Externalizing Problem Behavior. Crim. Justice Behav. 2015, 42, 245–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldry, A.C. Bullying in Schools and Exposure to Domestic Violence. Child Abuse Negl. 2003, 27, 713–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauer, N.S.; Herrenkohl, T.I.; Lozano, P.; Rivara, F.P.; Hill, K.G.; Hawkins, J.D. Childhood Bullying Involvement and Exposure to Intimate Partner Violence. Pediatrics 2006, 118, e235–e242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nocentini, A.; Fiorentini, G.; Di Paola, L.; Menesini, E. Parents, Family Characteristics and Bullying Behavior: A Systematic Review. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2019, 45, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, C.; Jenkins, S.R. Exploring Bullying, Partner Violence, and Social Information Processing. Int. J. Bullying Prev. 2024, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voisin, D.R.; Hong, J.S. A Meditational Model Linking Witnessing Intimate Partner Violence and Bullying Behaviors and Victimization Among Youth. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2012, 24, 479–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacchini, D.; Esposito, G.; Affuso, G. Social Experience and School Bullying. J. Community Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 19, 17–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaux, E.; Molano, A.; Podlesky, P. Socio-economic, Socio-political and Socio-emotional Variables Explaining School Bullying: A Country-wide Multilevel Analysis. Aggress. Behav. 2009, 35, 520–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, J.P.; Ingram, K.M.; Merrin, G.J.; Espelage, D.L. Exposure to Parental and Community Violence and the Relationship to Bullying Perpetration and Victimization among Early Adolescents: A Parallel Process Growth Mixture Latent Transition Analysis. Scand. J. Psychol. 2020, 61, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, D.; Proctor, L.J. Community Violence Exposure and Children’s Social Adjustment in the School Peer Group: The Mediating Roles of Emotion Regulation and Social Cognition. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2000, 68, 670–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valdés Cuervo, A.A.; Tánori Quintana, J.; Carlos Martínez, E.A.; Wendlandt Amezaga, T.R. Challenging Behavior, Parental Conflict and Community Violence in Students with Aggressive Behavior. Int. J. Psychol. Res. 2018, 11, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Owens, L.; Skrzypiec, G.; Wadham, B. Thinking Patterns, Victimisation and Bullying among Adolescents in a South Australian Metropolitan Secondary School. Int. J. Adolesc. Youth 2014, 19, 190–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodge, K.A.; Bates, J.E.; Pettit, G.S. Mechanisms in the Cycle of Violence. Science 1990, 250, 1678–1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huesmann, L.R.; Kirwil, L. Why Observing Violence Increases the Risk of Violent Behavior in the Observer. In The Cambridge Handbook of Violent Behavior and Aggression; Flannery, D.J., Vazsonyi, A.T., Waldman, I.D., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; pp. 545–570.

- Mrug, S.; Loosier, P.S.; Windle, M. Violence Exposure across Multiple Contexts: Individual and Joint Effects on Adjustment. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2008, 78, 70–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng-Mak, D.S.; Salzinger, S.; Feldman, R.; Stueve, A. Normalization of Violence among Inner-City Youth: A Formulation for Research. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2002, 72, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allwood, M.A.; Bell, D.J. A Preliminary Examination of Emotional and Cognitive Mediators in the Relations between Violence Exposure and Violent Behaviors in Youth. J. Community Psychol. 2008, 36, 989–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradshaw, C.P.; Rodgers, C.R.R.; Ghandour, L.A.; Garbarino, J. Social–Cognitive Mediators of the Association between Community Violence Exposure and Aggressive Behavior. Sch. Psychol. Q. 2009, 24, 199–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvete, E.; Orue, I. The Impact of Violence Exposure on Aggressive Behavior through Social Information Processing in Adolescents. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2011, 81, 38–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hyde, L.W.; Shaw, D.S.; Moilanen, K.L. Developmental Precursors of Moral Disengagement and the Role of Moral Disengagement in the Development of Antisocial Behavior. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2010, 38, 197–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swearer, S.M.; Espelage, D.L. Bullying in American Schools; Espelage, D.L., Swearer, S.M., Eds.; Routledge, 2004; ISBN 9781135624422.

- Swearer, S.M.; Espelage, D.L.; Vaillancourt, T.; Hymel, S. What Can Be Done About School Bullying? Educ. Res. 2010, 39, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swearer, S.M.; Hymel, S. Understanding the Psychology of Bullying: Moving toward a Social-Ecological Diathesis–Stress Model. Am. Psychol. 2015, 70, 344–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cyr, K.; Chamberland, C.; Lessard, G.; Clément, M.-È.; Wemmers, J.-A.; Collin-Vézina, D.; Gagné, M.-H.; Damant, D. Polyvictimization in a Child Welfare Sample of Children and Youths. Psychol. Violence 2012, 2, 385–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkelhor, D.; Ormrod, R.; Turner, H.; Hamby, S.L. The Victimization of Children and Youth: A Comprehensive, National Survey. Child Maltreat. 2005, 10, 5–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kilpatrick, D.G.; Ruggiero, K.J.; Acierno, R.; Saunders, B.E.; Resnick, H.S.; Best, C.L. Violence and Risk of PTSD, Major Depression, Substance Abuse/Dependence, and Comorbidity: Results from the National Survey of Adolescents. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2003, 71, 692–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkelhor, D. , Turner, H., Hamby, S., & Ormrod, R. Poly-Victimization: Children’s Exposure to Multiple Types of Violence, Crime, and Abuse. Juv. Justice Bull. – NCJ 235504.

- Bacchini, D.; Esposito, C. Growing up in Violent Contexts: Differential Effects of Community, Family, and School Violence on Child Adjustment; Balvin, N., Christie, D., Eds.; Children and peace. peace psychology book series; Springer: Cham, 2020.

- Margolin, G.; Vickerman, K.A.; Oliver, P.H.; Gordis, E.B. Violence Exposure in Multiple Interpersonal Domains: Cumulative and Differential Effects. J. Adolesc. Heal. 2010, 47, 198–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrug, S.; Windle, M. Prospective Effects of Violence Exposure across Multiple Contexts on Early Adolescents’ Internalizing and Externalizing Problems. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2010, 51, 953–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guerra, N.G.; Huesmann, L.R.; Spindler, A. Community Violence Exposure, Social Cognition, and Aggression among Urban Elementary School Children. Child Dev. 2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horowitz, K.; McKay, M.; Marshall, R. Community Violence and Urban Families: Experiences, Effects, and Directions for Intervention. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2005, 75, 356–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GORMAN–SMITH, D.; TOLAN, P. The Role of Exposure to Community Violence and Developmental Problems among Inner-City Youth. Dev. Psychopathol. 1998, 10, 101–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crick, N.R.; Dodge, K.A. A Review and Reformulation of Social Information-Processing Mechanisms in Children’s Social Adjustment. Psychol. Bull. 1994, 115, 74–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahinfar, A.; Kupersmidt, J.B.; Matza, L.S. The Relation between Exposure to Violence and Social Information Processing among Incarcerated Adolescents. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2001, 110, 136–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooley-Quille, M.; Boyd, R.C.; Frantz, E.; Walsh, J. Emotional and Behavioral Impact of Exposure to Community Violence in Inner-City Adolescents. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2001, 30, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aisenberg, E.; Ayón, C.; Orozco-Figueroa, A. The Role of Young Adolescents’ Perception in Understanding the Severity of Exposure to Community Violence and PTSD. J. Interpers. Violence 2008, 23, 1555–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowes, L.; Arseneault, L.; Maughan, B.; Taylor, A.; Caspi, A.; Moffitt, T.E. School, Neighborhood, and Family Factors Are Associated With Children’s Bullying Involvement: A Nationally Representative Longitudinal Study. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2009, 48, 545–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cluver, L.; Bowes, L.; Gardner, F. Risk and Protective Factors for Bullying Victimization among AIDS-Affected and Vulnerable Children in South Africa. Child Abuse Negl. 2010, 34, 793–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, C.J.; San Miguel, C.; Hartley, R.D. A Multivariate Analysis of Youth Violence and Aggression: The Influence of Family, Peers, Depression, and Media Violence. J. Pediatr. 2009, 155, 904–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, S.; Buckley, H.; Whelan, S. The Impact of Exposure to Domestic Violence on Children and Young People: A Review of the Literature. Child Abuse Negl. 2008, 32, 797–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moretti, M.M.; Obsuth, I.; Odgers, C.L.; Reebye, P. Exposure to Maternal vs. Paternal Partner Violence, PTSD, and Aggression in Adolescent Girls and Boys. Aggress. Behav. 2006, 32, 385–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustanoja, S.; Luukkonen, A.-H.; Hakko, H.; Räsänen, P.; Säävälä, H.; Riala, K. Is Exposure to Domestic Violence and Violent Crime Associated with Bullying Behaviour Among Underage Adolescent Psychiatric Inpatients? Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2011, 42, 495–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espelage, D.L.; Bosworth, K.; Simon, T.R. Examining the Social Context of Bullying Behaviors in Early Adolescence. J. Couns. Dev. 2000, 78, 326–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swearer, S.M.; Doll, B. Bullying in Schools. J. Emot. Abus. 2001, 2, 7–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andershed, H.; Kerr, M.; Stattin, H. Bullying in School and Violence on the Streets: Are the Same People Involved? J. Scand. Stud. Criminol. Crime Prev. 2001, 2, 31–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodge, K.A.; Pettit, G.S. A Biopsychosocial Model of the Development of Chronic Conduct Problems in Adolescence. Dev. Psychol. 2003, 39, 349–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, U.; Morris, P.A. The Ecology of Developmental Processes. Vol. 1: Theoretical Models of Human Development. In Handbook of child psychology; 1998.

- Bandura, A. Self-Efficacy: Toward a Unifying Theory of Behavioral Change. Psychol. Rev. 1977, 84, 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory.; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- De Angelis, G.; Bacchini, D.; Affuso, G. The Mediating Role of Domain Judgement in the Relation between the Big Five and Bullying Behaviours. Pers. Individ. Dif. 2016, 90, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barriga, A. Q. , Gibbs, J. C., Potter, G., & Liau, A.K. The How I Think Questionnaire Manual; Research Press: Champaign, IL, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs, J. C. , Potter, G. B., & Goldstein, A.P. The EQUIP Program: Teaching Youth to Think and Act Responsibly through a Peer-Helping Approach; Reserch Press: Champaign, IL, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Nas, C.N.; Brugman, D.; Koops, W. Effects of the EQUIP Programme on the Moral Judgement, Cognitive Distortions, and Social Skills of Juvenile Delinquents. Psychol. Crime Law 2005, 11, 421–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, J.C.; Potter, G.B.; Barriga, A.Q.; Liau, A.K. Developing the Helping Skills and Prosocial Motivation of Aggressive Adolescents in Peer Group Programs. Aggress. Violent Behav. 1996, 1, 283–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohlberg, L. Essays on Moral Development; Harper & Row: San Francisco, CA; Vol. 2;

- Bandura, A. Social Cognitive Theory of Self-Regulation. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 248–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sykes, G.M.; Matza, D. Techniques of Neutralization: A Theory of Delinquency. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1957, 22, 664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeaud; Eisner The Nature of the Association Between Moral Neutralization and Aggression: A Systematic Test of Causality in Early Adolescence. Merrill. Palmer. Q. 2015, 61, 68. [CrossRef]

- Maruna, S.; Copes, H. What Have We Learned from Five Decades of Neutralization Research? Crime and Justice 2005, 32, 221–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aquilar, S.; Bacchini, D.; Affuso, G. Three-year Cross-lagged Relationships among Adolescents’ Antisocial Behavior, Personal Values, and Judgment of Wrongness. Soc. Dev. 2018, 27, 381–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuchtman-Ya’Ar, E. Value Priorities in Israeli Society: An Examination of Inglehart’s Theory of Modernization and Cultural Variation. Comp. Sociol. 2002, 1, 347–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Social Learning Theory of Aggression. J. Commun. 1978, 28, 12–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodge, K. A., Coie, J. D. & Lynam, D. Aggression and Antisocial Behaviour in Youth. In Handbook of Child Psychology: Social, Emotional, and Personality Development; N. Eisenberg, W. Damon, & R.M.L., Ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, 2006; Vol. 3, pp. 719–788.

- Nickoletti, P.; Taussig, H.N. Outcome Expectancies and Risk Behaviors in Maltreated Adolescents. J. Res. Adolesc. 2006, 16, 217–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvete, E. Justification of Violence Beliefs and Social Problem-Solving as Mediators between Maltreatment and Behavior Problems in Adolescents. Span. J. Psychol. 2007, 10, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvete, E.; Orue, I. Cognitive Mechanisms of the Transmission of Violence: Exploring Gender Differences among Adolescents Exposed to Family Violence. J. Fam. Violence 2013, 28, 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrenkohl, T.I.; Huang, B.; Tajima, E.A.; Whitney, S.D. Examining the Link between Child Abuse and Youth Violence. J. Interpers. Violence 2003, 18, 1189–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvete, E.; Fernández-González, L.; González-Cabrera, J.M.; Gámez-Guadix, M. Continued Bullying Victimization in Adolescents: Maladaptive Schemas as a Mediational Mechanism. J. Youth Adolesc. 2018, 47, 650–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huesmann, L.R.; Guerra, N.G. Children’s Normative Beliefs about Aggression and Aggressive Behavior. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1997, 72, 408–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, V.; Hoaken, P.N.S. Cognition, Emotion, and Neurobiological Development: Mediating the Relation Between Maltreatment and Aggression. Child Maltreat. 2007, 12, 281–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponce, A.N.; Williams, M.K.; Allen, G.J. Experience of Maltreatment as a Child and Acceptance of Violence in Adult Intimate Relationships: Mediating Effects of Distortions in Cognitive Schemas. Violence Vict. 2004, 19, 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, D.L.; Carr, P.J. Violent Youths’ Responses to High Levels of Exposure to Community Violence: What Violent Events Reveal about Youth Violence. J. Community Psychol. 2008, 36, 1026–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacchini, D.; Affuso, G.; De Angelis, G. Moral vs. Non-Moral Attribution in Adolescence: Environmental and Behavioural Correlates. Eur. J. Dev. Psychol. 2013, 10, 221–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, C.; Affuso, G.; Dragone, M.; Bacchini, D. Effortful Control and Community Violence Exposure as Predictors of Developmental Trajectories of Self-Serving Cognitive Distortions in Adolescence: A Growth Mixture Modeling Approach. J. Youth Adolesc. 2020, 49, 2358–2371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, C.; Spadari, E.M.; Caravita, S.C.S.; Bacchini, D. Profiles of Community Violence Exposure, Moral Disengagement, and Bullying Perpetration: Evidence from a Sample of Italian Adolescents. J. Interpers. Violence 2022, 37, 5887–5913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahlin, E.M.; Lobo Antunes, M.J. Levels of Guardianship in Protecting Youth Against Exposure to Violence in the Community. Youth Violence Juv. Justice 2017, 15, 62–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmivalli, C.; Lagerspetz, K.; Björkqvist, K.; Österman, K.; Kaukiainen, A. Bullying as a Group Process: Participant Roles and Their Relations to Social Status within the Group. Aggress. Behav. 1998, 22, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Ryoo, J.H.; Swearer, S.M.; Turner, R.; Goldberg, T.S. Longitudinal Relationships between Bullying and Moral Disengagement among Adolescents. J. Youth Adolesc. 2017, 46, 1304–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CNEL, I. (2014) Bes 2016. Il Benessere Equo e Sostenibile in Italia [Bes 2016. The Equitable and Sustainable Welfare in Italy]. Available online: https://www.istat.it/it/files/2016/12/BES-2016.pdf (accessed on 25 April 2024).

- Istituto Nazionale di Statistica (ISTAT) Ciclo Di Audizioni Sul Tema Della Dispersione Scolastica [Series of Hearings on Early School Leaving]. Available online: https://www.istat.it/it/files/2021/07/Istat-Audizione-Dispersione-scolastica_18-giugno-2021.pdf (accessed on 25 April 2024).

- Little, R.J.A.; Rubin, D.B. Statistical Analysis with Missing Data; Wiley: New York, NY, 2002; ISBN 0471183865. [Google Scholar]

- Straus, M.A. Measuring Intrafamily Conflict and Violence: The Conflict Tactics (CT) Scales. J. Marriage Fam. 1979, 41, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacchini, D.; De Angelis, G.; Affuso, G.; Brugman, D. The Structure of Self-Serving Cognitive Distortions. Meas. Eval. Couns. Dev. 2016, 49, 163–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palladino, B.E.; Nocentini, A.; Menesini, E. Evidence-based Intervention against Bullying and Cyberbullying: Evaluation of the NoTrap! Program in Two Independent Trials. Aggress. Behav. 2016, 42, 194–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caprara, G.V.; Barbaranelli, C.; Borgogni, L.; Perugini, M. The “Big Five Questionnaire”: A New Questionnaire to Assess the Five Factor Model. Pers. Individ. Dif. 1993, 15, 281–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, D.A.; Maxwell, S.E. Testing Mediational Models With Longitudinal Data: Questions and Tips in the Use of Structural Equation Modeling. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2003, 112, 558–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacKinnon, D.P. Introduction to Statistical Mediation Analysis; Routledge, 2012; ISBN 9780203809556.

- Muthén, L.K.; Muthén, B.O. Mplus User’s Guide; 8th ed.; Muthén & Muthén: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Mo Wang; Bodner, T. E. Growth Mixture Modeling. Organ. Res. Methods 2007, 10, 635–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentler, P.M.; Yuan, K.-H. On Adding a Mean Structure to a Covariance Structure Model. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2000, 60, 326–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentler, P.M. Comparative Fit Indexes in Structural Models. Psychol. Bull. 1990, 107, 238–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tucker, L.R.; Lewis, C. A Reliability Coefficient for Maximum Likelihood Factor Analysis. Psychometrika 1973, 38, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, M.W.; Cudeck, R. Alternative Ways of Assessing Model Fit. Sociol. Methods Res. 1993, 21, 230–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff Criteria for Fit Indexes in Covariance Structure Analysis: Conventional Criteria versus New Alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. A Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satorra, A. Scaled and Adjusted Restricted Tests in Multi-Sample Analysis of Moment Structures BT - Innovations in Multivariate Statistical Analysis. In Innovations in Multivariate Statistical Analysis; 2000 ISBN 978-1-4613-7080-2.

- Garcia, O.F.; Serra, E.; Zacares, J.J.; Calafat, A.; Garcia, F. Alcohol Use and Abuse and Motivations for Drinking and Non-Drinking among Spanish Adolescents: Do We Know Enough When We Know Parenting Style? Psychol. Health 2020, 35, 645–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradshaw, C.P.; Waasdorp, T.E.; Goldweber, A.; Johnson, S.L. Bullies, Gangs, Drugs, and School: Understanding the Overlap and the Role of Ethnicity and Urbanicity. J. Youth Adolesc. 2013, 42, 220–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youngblade, L.M.; Theokas, C.; Schulenberg, J.; Curry, L.; Huang, I.-C.; Novak, M. Risk and Promotive Factors in Families, Schools, and Communities: A Contextual Model of Positive Youth Development in Adolescence. Pediatrics 2007, 119, S47–S53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, E. The Code of the Streets. In Anomie, Strain and Subcultural Theories of Crime; Anderson, E., Ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, 2017; pp. 303–312. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs, J.C. Moral Reasoning Training: The Values Component. In New perspectives on aggression replacement training: practice, research, and application; Goldstein, P., Nensén, R., Daleflod, B., Kalt, M., Eds.; Wiley: West Sussex, 2004; pp. 50–72. [Google Scholar]

- Hindelang, M.J.; Gottfredson, M.R.; Garofalo, J. Victims of Personal Crime: An Empirical Foundation for a Theory of Personal Victimization; Ballinger Publishing Company: Cambridge, MA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Gini, G.; Pozzoli, T.; Hymel, S. Moral Disengagement among Children and Youth: A Meta-Analytic Review of Links to Aggressive Behavior. Aggress. Behav. 2014, 40, 56–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curry, A.; Latkin, C.; Davey-Rothwell, M. Pathways to Depression: The Impact of Neighborhood Violent Crime on Inner-City Residents in Baltimore, Maryland, USA. Soc. Sci. Med. 2008, 67, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmivalli, C. Bullying and the Peer Group: A Review. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2010, 15, 112–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamaker, E.L.; Kuiper, R.M.; Grasman, R.P.P.P. A Critique of the Cross-Lagged Panel Model. Psychol. Methods 2015, 20, 102–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DiBiase, A.M.; Gibbs, J.C.; Potter, G.B.; Spring, B. EQUIP for Educators: Teaching Youth (Grades 5-8) to Think and Act Responsibly; Research Press: Champaign, IL, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Dragone, M.; Esposito, C.; De Angelis, G.; Bacchini, D. Equipping Youth to Think and Act Responsibly: The Effectiveness of the “EQUIP for Educators” Program on Youths’ Self-Serving Cognitive Distortions and School Bullying Perpetration. Eur. J. Investig. Heal. Psychol. Educ. 2022, 12, 814–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| (a) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | ||||||||||||

| 1. T1 DVW | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2. T1 DVV | 0.61*** | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3. T1 CDs | 0.18*** | 0.26*** | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4. T1 BP | 0.18*** | 0.28*** | 0.34*** | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| 5. T2 DVW | 0.54*** | 0.36*** | 0.17*** | 0.24*** | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| 6. T2 DVV | 0.34*** | 0.51*** | 0.21*** | 0.24*** | 0.67*** | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 7. T2 CDs | 0.08* | 0.19*** | 0.62*** | 0.32*** | 0.24*** | 0.32*** | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 8. T2 BP | 0.04 | 0.13*** | 0.23*** | 0.37*** | 0.20*** | 0.23*** | 0.33*** | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||

| 9. T3 DVW | 0.47*** | 0.33*** | 0.14*** | 0.16*** | 0.48*** | 0.39*** | 0.17*** | 0.11** | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 10. T3 DVV | 0.32*** | 0.45*** | 0.19*** | 0.20*** | 0.40*** | 0.58*** | 0.30*** | 0.21*** | 0.66*** | 1 | |||||||||||||||||

| 11. T3 CDs | 0.06 | 0.17*** | 0.43*** | 0.23*** | 0.14*** | 0.24*** | 0.53*** | 0.30*** | 0.19*** | 0.31*** | 1 | ||||||||||||||||

| 12. T3 BP | 0.11** | 0.23*** | 0.24*** | 0.29*** | 0.16*** | 0.29*** | 0.34*** | 0.42*** | 0.29*** | 0.35*** | 0.44*** | 1 | |||||||||||||||

| 13. T4 DVW | 0.37*** | 0.28*** | 0.16*** | 0.22*** | 0.46*** | 0.32*** | 0.13*** | 0.16*** | 0.36*** | 0.28*** | 0.14*** | 0.19*** | 1 | ||||||||||||||

| 14. T4 DVV | 0.30*** | 0.43*** | 0.20*** | 0.26*** | 0.38*** | 0.48*** | 0.20*** | 0.19*** | 0.27*** | 0.41*** | 0.26*** | 0.24*** | 0.71*** | 1 | |||||||||||||

| 15. T4 CDs | 0.07 | 0.14*** | 0.43*** | 0.26*** | 0.10* | 0.17*** | 0.47*** | 0.32*** | 0.14*** | 0.22*** | 0.54*** | 0.36*** | 0.19*** | 0.22*** | 1 | ||||||||||||

| 16. T4 BP | 0.06 | 0.12** | 0.23*** | 0.39*** | 0.12** | 0.14*** | 0.29*** | 0.32*** | 0.15*** | 0.23*** | 0.36*** | 0.39*** | 0.19*** | 0.23*** | 0.41*** | 1 | |||||||||||

| M | 1.33 | 1.62 | 2.31 | 1.30 | 1.35 | 1.58 | 2.19 | 1.32 | 1.33 | 1.47 | 2.16 | 1.32 | 1.33 | 1.46 | 2.03 | 1.25 | |||||||||||

| SDs | 0.62 | 0.81 | 0.86 | 0.53 | 0.65 | 0.79 | 0.84 | 0.54 | 0.66 | 0.76 | 0.91 | 0.56 | 0.70 | 0.79 | 0.91 | 0.51 | |||||||||||

| Scores range | 1-5 | 1-6 | 1-5 | 1-5 | 1-6 | 1-5 | 1-5 | 1-6 | 1-5 | 1-5 | 1-6 | 1-5 | |||||||||||||||

| Note. DVW = Domestic Violence Witnessing; DVV = Domestic Violence Victimization; CDs = Cognitive Distortions; BP = Bullying Perpetration. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| (b) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | ||||||||||||

| 1. T1 CVW | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2. T1 CVV | 0.48*** | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3. T1 CDs | 0.34*** | 0.21*** | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4. T1 BP | 0.33*** | 0.23*** | 0.34*** | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| 5. T2 CVW | 0.45*** | 0.26*** | 0.22*** | 0.29*** | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| 6. T2 CVV | 0.18*** | 0.28*** | 0.10** | 0.16*** | 0.51*** | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 7. T2 CDs | 0.23*** | 0.15*** | 0.62*** | 0.32*** | 0.33*** | 0.17*** | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 8. T2 BP | 0.19*** | 0.09* | 0.23*** | 0.37*** | 0.28*** | 0.19*** | 0.33*** | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||

| 9. T3 CVW | 0.30*** | 0.24*** | 0.11** | 0.20*** | 0.41*** | 0.25*** | 0.18*** | 0.13*** | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 10. T3 CVV | 0.12** | 0.22*** | 0.09* | 0.12** | 0.16*** | 0.24*** | 0.12** | 0.09* | 0.64*** | 1 | |||||||||||||||||

| 11. T3 CDs | 0.22*** | 0.12*** | 0.43*** | 0.23*** | 0.29*** | 0.18*** | 0.53*** | 0.30*** | 0.22*** | 0.16*** | 1 | ||||||||||||||||

| 12. T3 BP | 0.20*** | 0.15*** | 0.24*** | 0.29*** | 0.25*** | 0.22*** | 0.34*** | 0.42*** | 0.27*** | 0.25*** | 0.44*** | 1 | |||||||||||||||

| 13. T4 CVW | 0.28*** | 0.16*** | 0.20*** | 0.19*** | 0.36*** | 0.24*** | 0.18*** | 0.17*** | 0.36*** | 0.19*** | 0.24*** | 0.22*** | 1 | ||||||||||||||

| 14. T4 CVV | 0.09* | 0.10* | 0.14*** | 0.13*** | 0.12** | 0.17*** | 0.09* | 0.09* | 0.16*** | 0.23*** | 0.09* | 0.11** | 0.64*** | 1 | |||||||||||||

| 15. T4 CDs | 0.29*** | 0.14*** | 0.43*** | 0.26*** | 0.19*** | 0.08* | 0.47*** | 0.32*** | 0.14*** | 0.07 | 0.54*** | 0.36*** | 0.26*** | 0.14*** | 1 | ||||||||||||

| 16. T4 BP | 0.17*** | 0.10* | 0.23*** | 0.39*** | 0.21*** | 0.15*** | 0.29*** | 0.32*** | 0.20*** | 0.11** | 0.36*** | 0.39*** | 0.25*** | 0.13** | 0.41*** | 1 | |||||||||||

| M | 1.72 | 1.46 | 2.31 | 1.30 | 1.75 | 1.40 | 2.19 | 1.32 | 1.65 | 1.38 | 2.16 | 1.32 | 1.64 | 1.40 | 2.03 | 1.25 | |||||||||||

| SDs | 0.74 | 0.62 | 0.86 | 0.53 | 0.80 | 0.54 | 0.84 | 0.54 | 0.89 | 0.71 | 0.91 | 0.56 | 0.86 | 0.77 | 0.91 | 0.51 | |||||||||||

| Scores range | 1-5 | 1-6 | 1-5 | 1-5 | 1-6 | 1-5 | 1-5 | 1-6 | 1-5 | 1-5 | 1-6 | 1-5 | |||||||||||||||

| Note. CVW = Community Violence Witnessing; CVV = Community Violence Victimization; CDs = Cognitive Distortions; BP = Bullying Perpetration. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Domestic Violence Exposure | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Indirect Paths | β (SE) | 95% C.I.s | |

| LL | UL | ||

| T1 Victimization → T2 CDs → T3 Bullying Perpetration | 0.01* (0.00) | 0.002 | 0.017 |

| T2 Victimization → T3 CDs → T4 Bullying Perpetration | 0.01* (0.00) | 0.002 | 0.018 |

| T1 CDs → T2 Bullying Perpetration → T3 CDs | 0.02*** (0.00) | 0.009 | 0.026 |

| T2 CDs → T3 Bullying Perpetration → T4 CDs | 0.02*** (0.00) | 0.008 | 0.025 |

| T1 Bullying Perpetration → T2 CDs → T3 Bullying Perpetration | 0.02*** (0.01) | 0.009 | 0.028 |

| T2 Bullying Perpetration → T3 CDs → T4 Bullying Perpetration | 0.02*** (0.01) | 0.010 | 0.029 |

| Community Violence Exposure | |||

| T1 Witnessing → T2 CDs → T3 Bullying Perpetration | 0.01* (0.00) | 0.001 | 0.018 |

| T2 Witnessing → T3 CDs → T4 Bullying Perpetration | 0.01* (0.01) | 0.001 | 0.020 |

| T1 CDs → T2 Bullying Perpetration → T3 CDs | 0.02*** (0.00) | 0.009 | 0.025 |

| T2 CDs → T3 Bullying Perpetration → T4 CDs | 0.02*** (0.00) | 0.008 | 0.024 |

| T1 Bullying Perpetration → T2 CDs → T3 Bullying Perpetration | 0.02*** (0.01) | 0.008 | 0.026 |

| T2 Bullying Perpetration → T3 CDs → T4 Bullying Perpetration | 0.02*** (0.01) | 0.010 | 0.028 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).