Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has evolved significantly since the first case was reported in Wuhan, China in December 2019. From the start of the pandemic through April 6, 2024, the CDC reports there have been close to 1.2 million COVID-related deaths and 7 million hospitalizations in the United States.[

2] A large number of these COVID-19 related deaths occurred prior to the implementation of an universal immunization program in the United States.[

3] Notwithstanding, there remains a significant health burden related to COVID-19, and it remains the leading respiratory infectious disease responsible for hospitalizations and deaths regardless of age or comorbid status.

Vaccines have changed the trajectory of the pandemic. It has been estimated that between December 12, 2020 and November 30, 2022, COVID-19 vaccines have averted over 3.2 million COVID-19 deaths, 18.5 million COVID-19 hospitalizations and close to 120 million COVID-19 infections in the US.[

1] The public desire for COVID-19 vaccines were very high when introduced with an estimated 80.6% of all American adults (≥ 18 years) having received at least 1 dose.[

4] As the virus has continued to evolve, there have been the introduction of additional doses and new variant-specific formulations designed to protect the population from the rapidly evolving SARS-CoV-2 virus. The uptake of subsequent vaccine doses has been significantly lower than the first two dose.

The Public Health Emergency (PHE) was rescinded on May 10

th, 2023. Although COVID-19 is no longer considered a public health emergency, it continues to be the leading respiratory infectious disease and remains a persistent public health threat. This is due in part to the emergence of variants with enhanced transmissibility and pathogenicity. A new vaccine was approved on September 11, 2023, targeting the most prominent variant at the time of selection, XBB.1.5. This was followed by a simple recommendation from the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) on September 12, 2023, that every person 6 months of age and older receive at least one dose of the 2023/24 COVID-19 vaccine. Even with clear and simple recommendation, as of March 31, 2024, only 22.6% of eligible adults and 14% of children (6 months to 17 years) have received it.[

4,

5] This low vaccine uptake occurred during a period where there were approximately 1000 - 2500 COVID-19 deaths and 6500 - 30,000 hospitalizations due to COVID-19 each week.[

6]

With the ongoing impact of COVID-19 and the high likelihood for a new variant with a higher virulence or immune escape mechanism, it is important for governments, public health officials and healthcare providers to learn from some of the challenges of 2023-2024 fall/winter season to develop strategies to improve vaccine confidence and uptake. This could raise COVID-19 vaccination rates and thus improving patient outcomes and support public health objectives. In this paper, we will review the key lessons learned from the 2023-2024 season and provide some potential strategies to address key barriers to COVID-19 for future seasons.

COVID-19 During the 2023-2024 Season

Although the US public health emergency for COVID-19 ended on May 11, 2023, it continues to be a leading cause of hospitalizations due to respiratory infections. Between Sept 2, 2023 and March 31, 2024, there were over 600,000 hospitalizations and over 45,000 deaths due to COVID-19 in the US.[

3] At its peak, there were approximately 35,000 new hospitalization and 2,500 deaths per week. Like influenza, COVID-19 activity, hospitalizations, and deaths tends to follow peaks during the traditional winter viral respiratory season however, unlike influenza which typically drops below endemic levels (inter-seasonal levels) COVID-19 is responsible for significant burden throughout the year. Whilst the burden of disease has varied based on the different age groups, the morbidity and mortality remained significant regardless of age (

Table 1), supporting the CDC recommendations that all persons aged 6 months and older should receive updated 2023–2024 COVID-19 vaccine.[

7]

Pediatric Population

COVID-19 infection and illness continue to be a serious and urgent concern as hospitalization rates from 2020-2024 have consistently been high between October and January.[

3] Children who were hospitalized had low vaccination rates. Only 4.5% of children hospitalized due to COVID-19 completed their primary series against COVID-19 and 7% of children hospitalized initiated but did not complete COVID-19 primary vaccination series.[

10] Unlike what is seen in adults, almost half of children hospitalized for COVID-19 had no underlying conditions.[

10]

Adults 18-49 Years

Although this group was once thought to have a low risk of COVID-19 complications, they are still at risk of hospitalization. The rate of COVID-19 hospitalizations in Adults aged 18-49 was 37.4 per 100,000 people during the 2023-24 season.[

8] Low vaccination rate in this age group could affect hospitalization risk. During the 2022-2023 season, 42% of those hospitalized due to COVID-19 aged 18-49 were unvaccinated and only 8% of those hospitalized had received the 2023-2024 bivalent COVID-19 vaccine.[

11]

Adults 50-64 Years

With increasing age there is a higher COVID-19 hospitalization and comorbidity risk. The cumulative hospitalization rate for 2023-2024 season was 109.2 per 100,000 people.[

8] Like in other age groups, the hospitalization risk was much higher in those who were not up to date with the COVID-19 vaccine recommendations. During the 2022-2023 season, 26% of those hospitalized due to COVID-19 aged 50-64 years were unvaccinated and only 13% of those hospitalized had received the 2022-2023 bivalent COVID-19 vaccine.[

12]

Comorbidities are higher in this age group. Indeed, 69.5% of adults aged 55-64 have at least one chronic condition. Because this age group was not included in ACIP’s February 2024 COVID-19 additional dose recommendation these individuals are likely to have cost-sharing if they sought additional doses for vaccination.[

13] Compared with ages 18–29 years, the risk of death is 25 times higher in those ages 50–64 years.[

14]

Older Adults Age ≥ 65 Years

As was seen in the first years of the pandemic, this age group was the most impacted by severe outcomes. Compared with ages 18–29 years, 60 times higher in those ages 65–74 years, 140 times higher in those ages 75–84 years, and 340 times higher in those ages ≥85 years.[

14] The cumulative hospitalization rate for 2023-2024 season was 537.6 per 100,000 people.[

12] Comparatively, adults aged 65 years of age and older represented 218.2 per 100,000 people hospitalized due to influenza during the 2023-24 season.[

9] Nearly 1 in 6 hospitalized adults 65 years of age were residents of long-term care facilities.[

15] During the 2022-2023 season, 17% of those hospitalized due to COVID-19 aged 65 years of age and older were unvaccinated and only 25% of those hospitalized had received the 2023-2024 bivalent COVID-19 vaccine.[

11]

Comparatively, older adults represented 52% of all influenza-related hospitalizations during the 2022-23 influenza season.[

16] Like was seen with other age group the hospitalization burden was higher in those who were not up to date with current vaccine recommendations.

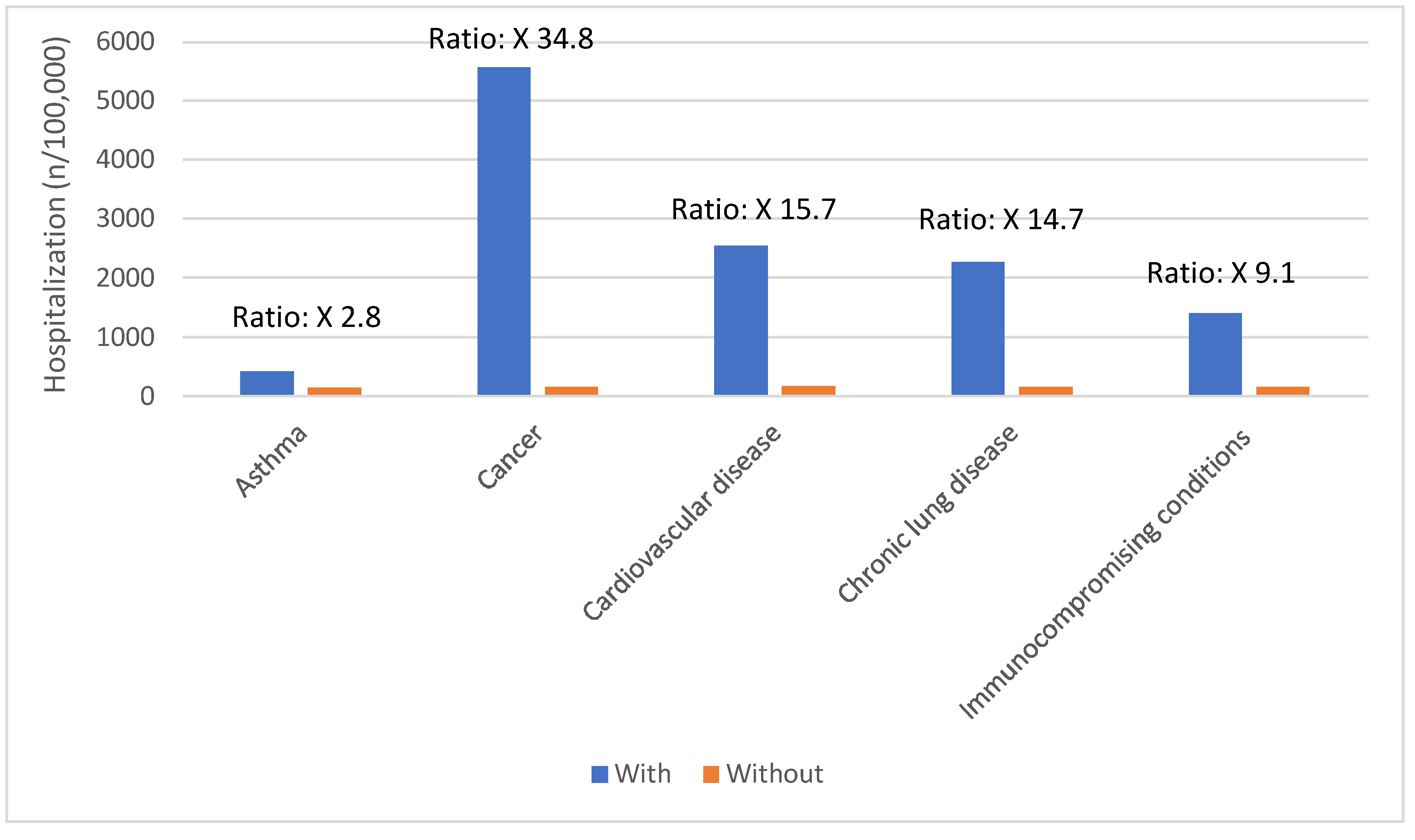

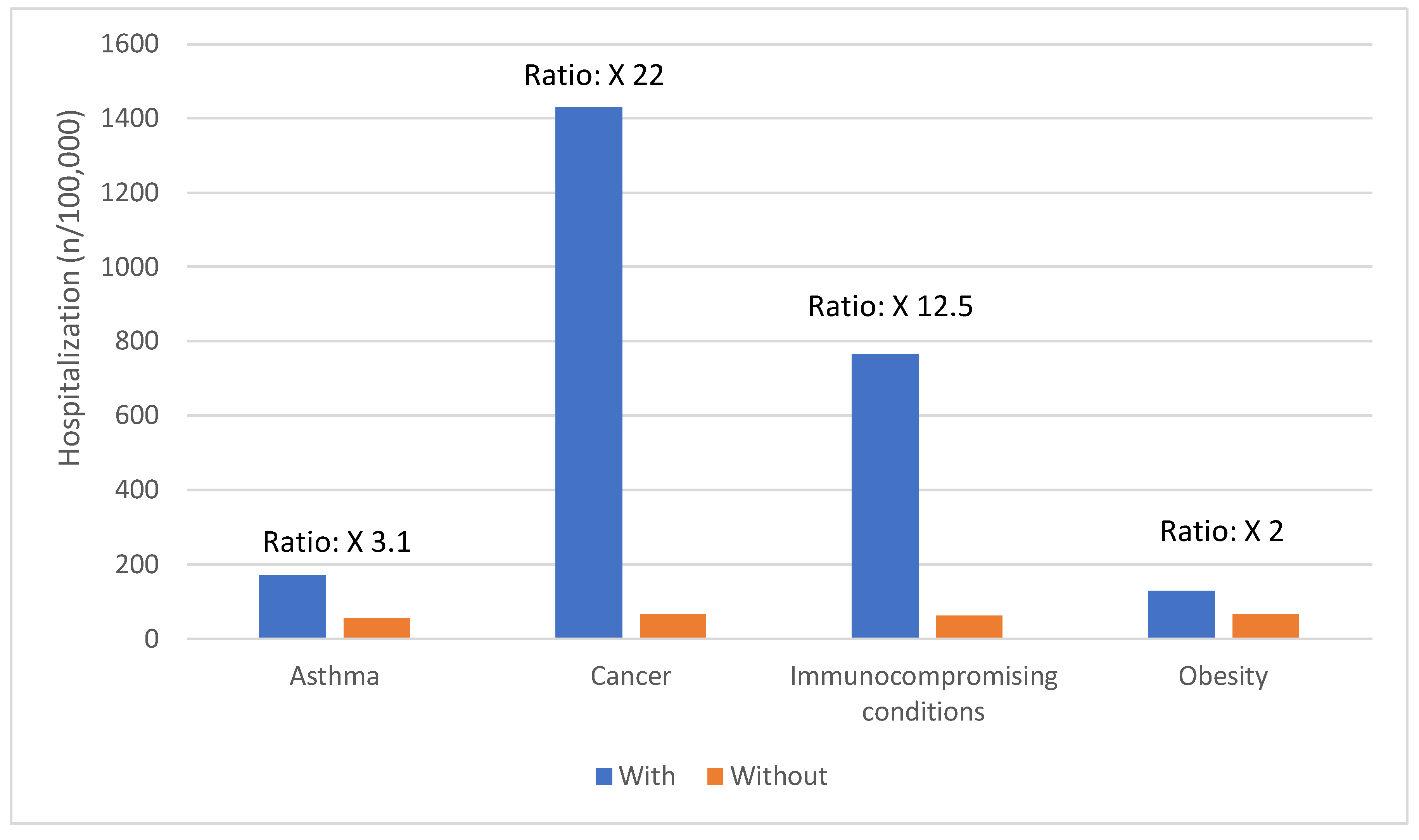

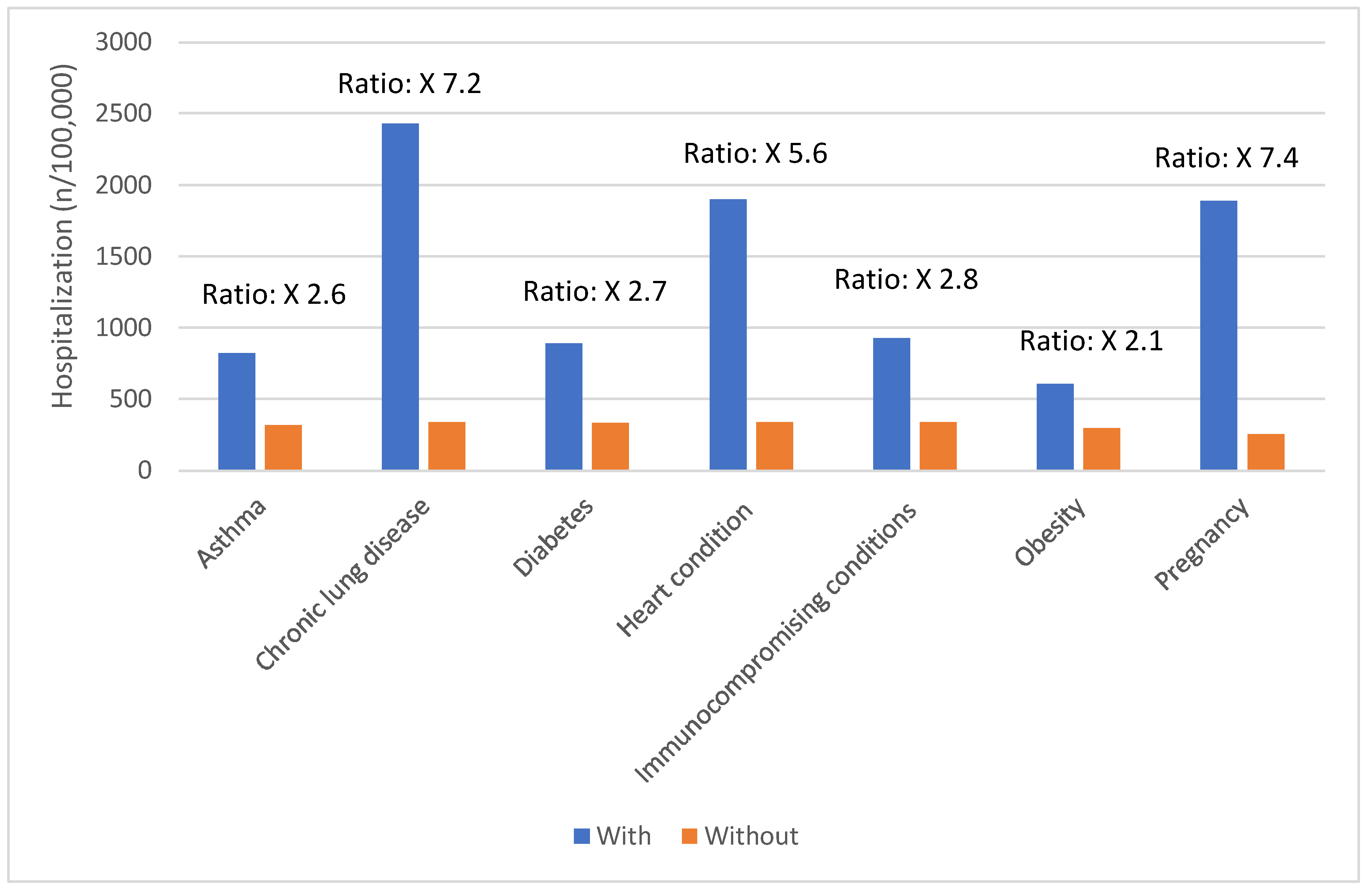

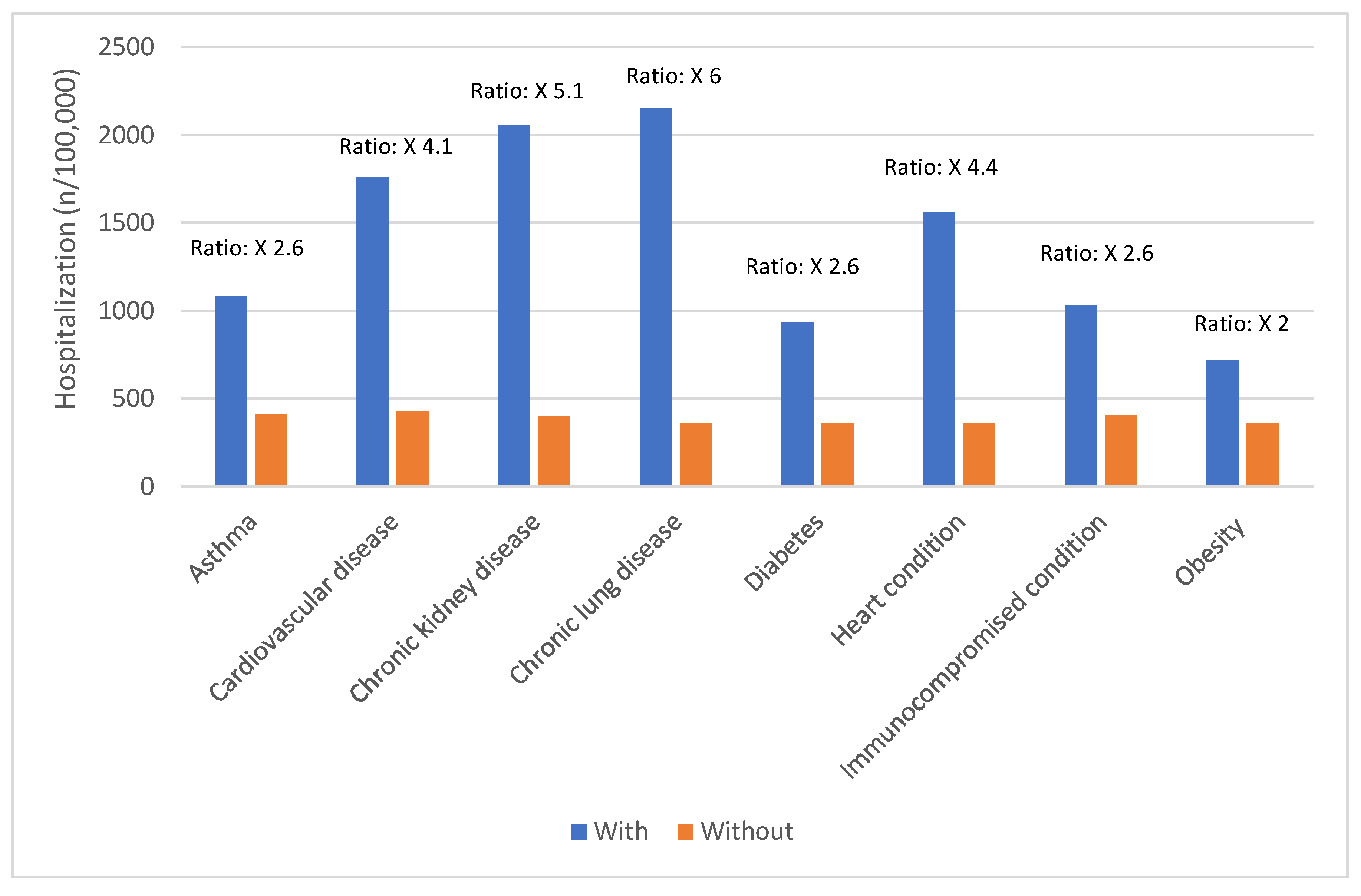

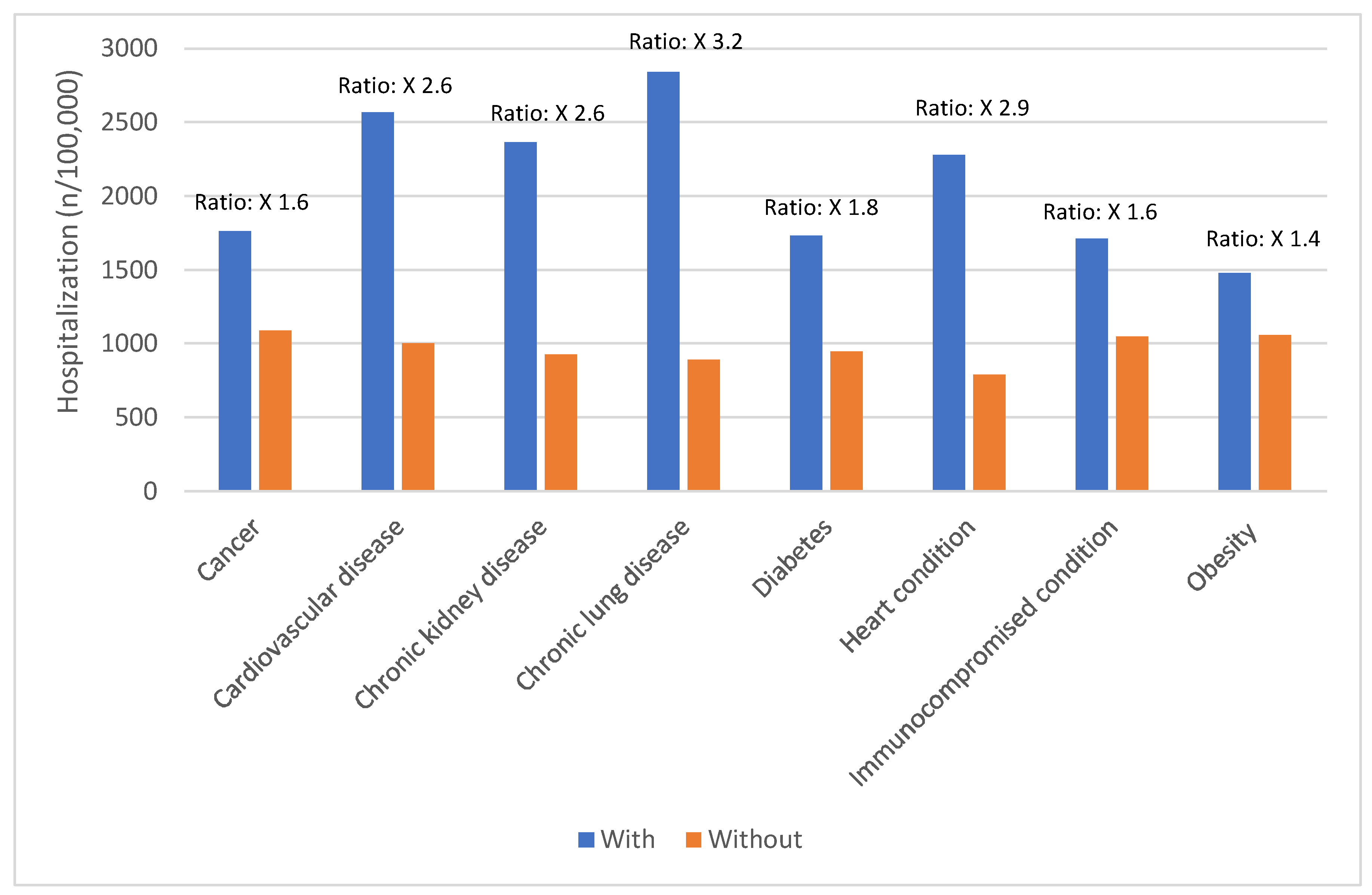

Risk Factors for Severe COVID-19 Outcomes

Certain groups continue to be at higher rates of severe COVID-19 outcomes across all ages.[

17] These including infants, older adults, and people with underlying medical conditions or certain disabilities (

Figure 1,

Figure 2,

Figure 3,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5).[

17] During the first seven months of 2023, older adults (≥65 years) accounted for 63% of hospitalizations and 88% of in-hospital COVID-19 related deaths.[

17] Of this group, 90% of those hospitalized had multiple pre-existing medical conditions.[

17] It is estimated that almost 1 in 2 US adults have at least one comorbid condition that increases the risk of complications of COVID-19.[

18] Many of these adults have multiple comorbidities, that further increase the risk of COVID-19.[

19] As the number of comorbidities increases, the risk of death, invasive mechanical ventilation and ICU admission also increases.[

19]

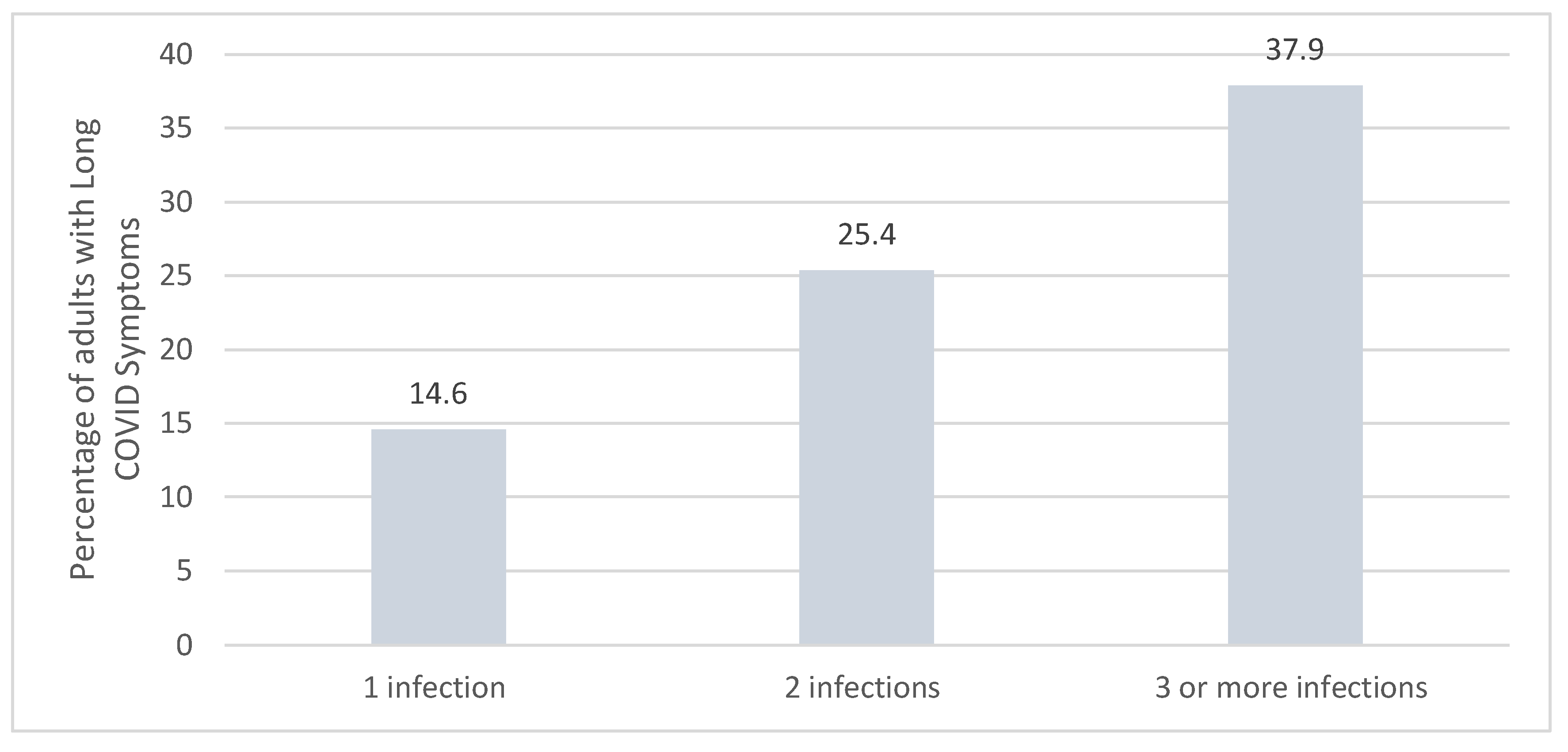

The Compounding Effect of Long COVID

Beyond hospitalizations and deaths, COVID-19 has been associated with an increased risk of long COVID. The impact of long COVID on the affected patient and the population is significant and tends to impact a different population than those at risk of COVID-related hospitalizations.[

22]

It is estimated that 17.6% of US adults or 17.7 million adults are currently experiencing long COVID, as of April 1, 2024 and 4 million Americans are living with a disabling condition due to long COVID.[

22] Based on 2024 US census population data, this would translate to approximately 44 million adults having experienced long COVID.[

23] The highest reported prevalence of long COVID was seen in people aged 40-49 years.[

22] The full impact of COVID-19 in this age group extends beyond hospitalizations.

Long COVID may also affect children, irrespective of whether they are at risk or healthy. The prevalence of long COVID in children was estimated at 23.4% in a meta-analysis of 40 studies including over 12,424 children.[

24] The prevalence of any symptom during 3-6, 6-12, and > 12 months were 26.4 %, 20.6 %, and 14.9 %.[

24]

The risk of long COVID is impacted each time the individual is infected with COVID-19. Reinfection further increases the risks of complications in the acute and post-acute phase versus those with no reinfection. The risk of at least one sequela is three times higher in those with a history of ≥3 infections (

Figure 6).

Long COVID has a significant burden on the healthcare systems with significantly increased healthcare utilization and cost, with estimated cost for the US of

$3.7 trillion through 2022.[

26] The Household Pulse Survey by the US Census Bureau states that 2-4 million Americans are out of work due to Long COVID with an estimated cost of those lost wages around

$170 billion a year.[

22] It is estimated that approximately 5.3% of US adults (~13.6 million adults) are currently experiencing long COVID symptoms.[

22] One study found the cognitive deficits associated with long COVID in those hospitalized for COVID-19 were equivalent in magnitude to 20 years of aging.[

27] It is estimated that close to 1 in 4 American adults who currently have long COVID have significant activity limitations.[

22]

COVID-19 Burden vs. Influenza

COVID-19 continues to cause a more significant burden than influenza in the US. Through 2023-2024 season, the cumulative rate of hospitalization due to COVID-19 was higher than for influenza during the same time period (

Table 2).[

28,

29] This was also consistent with the 2022-2023 season.[

30] Roughly 12% of hospitalizations with either COVID-19 or influenza included ICU admission.[

30]

COVID-19 hospitalization risk was higher than influenza in all age groups. This difference in impact was especially seen in older adults (≥ 65 years) where the number of COVID-19 related hospitalizations were more than double than that seen with influenza.[

28] Although the impact of influenza is less than seen with COVID-19, the immunization rate for influenza as of March 31, 2024, for US adults (≥18 years) was more than double than with COVID-19 (48.1% vs 22.6%).[

4,

31]

The Continued Evolution of COVID-19

The SARS-CoV-2 virus has continued to evolve through the fall and winter of 2023/24.[

32] During the summer and early fall of 2023, omicron XBB variants were co-circulating with no clear dominance.[

32] Through the winter of 2024, the JN.1 variant became the predominant circulating variant and this has continued into the spring.[

32] The emergence of the JN.1 variant coincided with an initial increase in hospitalizations due to COVID-19.[

3] As of May 25, 2024, KP.2 is now the predominant variant circulating (28.5%) with JN.1 representing only 8.4% of the circulating variants.[

32] The continued evolution of the SARS-CoV-2 virus could have significant impact on the entire US healthcare system such as hospitalizations in people with waning immunity. COVID-19 has not settled into a seasonal pattern, and it is impossible to predict which variant will be next. Owing to the fact that the SARS-CoV-2 virus continues to mutate, vaccines are updated to target the predominating variant.

COVID-19 2023/2024 Vaccine

FDA Approval and ACIP Recommendation

On September 11, 2023, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the updated (2023–2024 formula) COVID-19 mRNA vaccines by Moderna and Pfizer-BioNTech for persons aged ≥12 years and authorized these vaccines for persons aged 6 months–11 years under Emergency Use Authorization (EUA).[

7] The updated COVID-19 vaccines included a monovalent XBB.1.5 component, which targeted the circulating variants at that time.[

7] On September 12, 2023, ACIP recommended vaccination with the updated (2023–2024 Formula) COVID-19 vaccine for all persons aged ≥6 months.[

7]

Safety, Immunogenicity, and Effectiveness of the Vaccine

The immunogenicity of the 2023/2024 vaccine formulation significantly increases the virus-neutralizing antibodies for a variety of circulating variants.[

33] In uninfected individuals, the vaccine boosted serum virus-neutralization antibodies significantly against not only XBB.1.5 (27.0-fold), but also to the other variants EG.5.1, HV.1, HK.3, JD.1.1, and JN.1 (13.3-to-27.6-fold).[

33] The antibody response in individuals infected by Omicron subvariant, were significantly higher (1,504-to-22,978 fold higher) than in the uninfected group.[

33] Studies evaluating safety did not find an increase in new safety signals and most adverse events were mild to moderate in severity.[

34,

35] A nationwide cohort study of more than 1 million older adults (≥ 65 years) receiving the new vaccine formulation found no increase in 28 adverse events following administration.[

36]

The vaccine effectiveness (VE) of the 2023/2024 vaccine was evaluated across two large CDC networks (VISION and IVY).[

37] VE estimates against COVID-19–associated hospitalization were 52% (95% CI = 47%–57%) and 43% (95% CI = 27%–56.[

37] Another study evaluated the effectiveness of Moderna’s Omicron XBB.1.5 vaccine (mRNA-1273.815) at preventing COVID-19-related hospitalizations and any medically attended COVID-19 in adults ≥18 years, overall, and by age and underlying medical conditions.[

38] Overall, 859,335 matched pairs of mRNA-1273.815 recipients and unexposed adults were identified in the large electronic health record database.[

38] Among the overall adult population (≥18 years), VE was 60.2% (53.4–66.0%) against COVID-19-related hospitalization and 33.1% (30.2%–35.9%) against medically attended COVID-19 over a median follow-up of 63 (IQR: 44–78) days.[

38]

COVID-19 vaccines have a favorable safety profile as demonstrated by robust safety surveillance over 3 years of COVID-19 vaccine use.[

39] Anaphylactic reactions have been rarely reported following receipt of COVID-19 vaccines.[

39] A rare risk of myocarditis and pericarditis has occurred, however this is predominately in males ages 12-39 years.[

39] No new safety concerns have been identified for the 2023-2024 Formula COVID-19 vaccine. Local and systemic reactions are commonly reported following the administration of COVID-19 vaccines and this was seen more commonly with adolescents and younger adults compared to older adults.[

39]

2023/2024. Vaccine Uptake in Different Populations

As mentioned, the uptake of the 2023/2024 COVID-19 vaccine was far from optimal. Across all age categories it was lower than the 2023/2024 influenza vaccine (

Table 3). The uptake of the 2023/2024 vaccine was also lower in all minority US adults (Asian, Black, Hispanic, multiple races, Pacific Islander, American Indian) compared to White, non-Hispanic US adults (

Table 4).[

4] This reflects a decline from the vaccination rates reported in January 2022 where, thanks to efforts from partnerships across community-based organizations and black clergy, closed the gap between black communities. During this period, black life expectancy in the second year was better than white Americans. This further highlights the importance of community engagement coupled with supporting resources and funding to effectively close the vaccination gaps and raise life expectancy.

Attitudes and Intentions for COVID-19 Vaccination

Attitudes and intentions regarding COVID-19 vaccination provides insight into COVID-19 immunization for future seasons. The Omnibus survey conducted from January 5 to 29, 2024, in adults ≥18 years of age were asked about concerns and intentions regarding COVID-19 vaccination. Of those responding that they would probably or definitely not get the COVID-19 vaccine, the concerns raised were predominantly around the safety, with 47% stating unknown serious side effects and 33.2% having concerns around heart-related issues. Trust was another leading concern, with 39% of the respondents indicating that there were not enough human studies with the COVID-19 vaccine or that they did not trust government or pharma (37.2%). Whilst the effectiveness of the COVID-19 vaccine was cited by 32.9% of the respondents.

Not surprisingly, concerns leading to not receiving the COVID-19 vaccine can be grouped into three main categories, notably:

Perceived risk of getting ill or severity of COVID-19 versus safety/tolerability of the vaccine

Effectiveness of the COVID-19 vaccine

Safety of the COVID-19 vaccine.

Although there was a sizeable group of individuals who responded as probably or definitely will not get the COVID-19 vaccine that they do not trust government of pharma industry (37.2%), there remains a significant body of evidence indicating that patients and parents view their HCP as the most trusted source.[

40]

Adapting Strategies for Future COVID-19 Seasons

SARS-CoV-2 virus will likely remain endemic in the US and worldwide and seasonality has not been established. Ongoing strategies will be required to protect the US population and achieve public health goals. The 2023/2024 season highlighted a need for adjustments in the delivery of COVID-19 vaccines as significant gaps have been identified. Three key areas that can address many of the issues are:

- a)

Changes in the COVID-19 vaccine approval process to align with influenza to allow for co-administration

- b)

Increased integration of COVID-19 vaccine into routine delivery of care

- c)

Communication and engagement of healthcare providers for optimal patient education, and overcoming the challenges of misinformation and distrust, along with vaccine delivery.

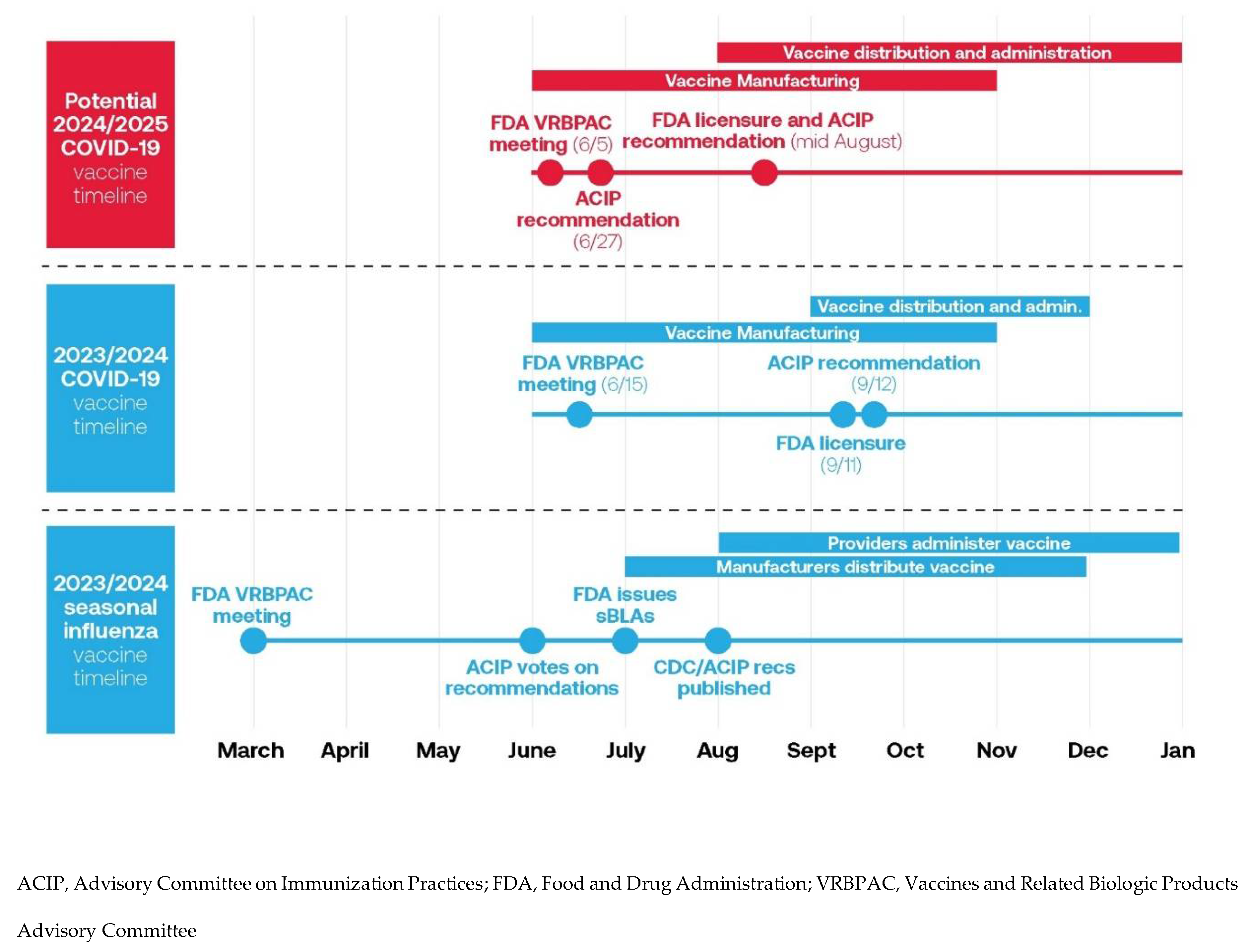

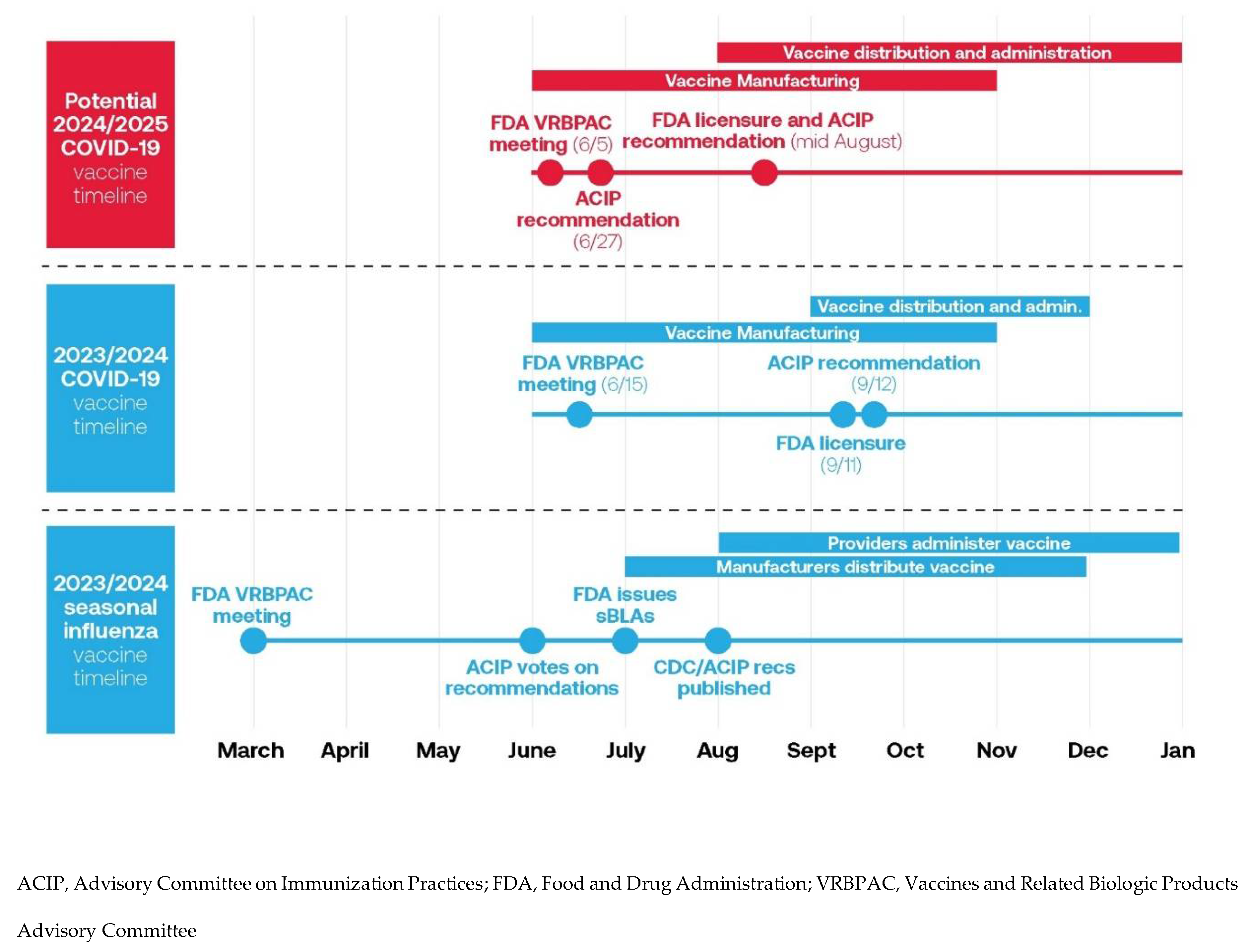

COVID-19 Vaccine Approval Process

The timing of the approval of the 2023/2024 COVID-19 vaccine may have contributed to the lower vaccine uptake in the United States. Although it would ideal for the delivery of influenza and the 2023/2024 COVID-19 vaccine at the same time to a patient, there was a difference their approval timing.[

41] The fall influenza vaccine approval was initiated in March 2023 with strain selection, with CDC/ACIP recommendations made in June 2023 (

Figure 1).[

41,

42] This allowed for the manufacturing and distribution of vaccines to allow providers to administer the vaccine prior to the influenza season. For the 2023/2024 COVID-19 vaccine, there was a delay in approval, FDA licensure, and ACIP recommendations. This significantly hampered vaccine distribution and uptake. This created challenges for the manufacturing and distribution of the vaccine in the early fall, and resulted in COVID vaccines for the 2023/24 season becoming available 6-8 weeks after flu vaccines were available.[

41]

The proposed new timeline for the 2024/2025 COVID-19 vaccine would have the FDA VRBPAC meeting in June 2024 for strain selection, with ACIP recommendations in June versus September.[

41] This allows for earlier file submission and approval (before September), vaccine manufacturing and distribution with administration to occur similarly to influenza vaccine. Fundamentally, the change in approval should help to simplify the manufacturing, distribution, communication and alignment with influenza vaccine recommendations.[

41]

Figure 1. 2023/2024 seasonal influenza vaccine timeline and 2023/2024 and potential 2024/2025 COVID-19 vaccine timeline [

41].

Increased Integration of COVID-19 Vaccine into Routine Delivery of Care

The 2023/2024 COVID-19 vaccine uptake demonstrates a need for a change in the way the vaccine and its recommendations are communicated to everyone ≥ 6 months. Minorities have some of the lowest vaccine uptake. Vaccination coverage in January 2024 was highest for non-Hispanic white adults (24%) but lower for Asian adults (19.2%), Black adults (16.4%), Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander adults (14%), Hispanic adults (13%) American Indians and Alaska Natives adults (11.4%).[

43] Moving forward, there is an imperative for public health to collaborate any person and group that regularly comes into contact with the people at risk of COVID-19 to discuss and promote vaccination. Simplified and trusted vaccine messaging from trusted sources at the point of care or in the community can help to increase awareness and address vaccine confidence and complacency.[

44] This message can be delivered from public health, community partners and healthcare providers to improve vaccine awareness and uptake.

In the past, adult immunization was discussed in what was perceived as the fall ‘vaccine season’. This was primarily due to the only consistent respiratory adult vaccine being the fall influenza vaccine. The adult vaccine schedule is becoming more crowded. To meet immunization targets, it is important for all healthcare providers and public health to start and continue to have vaccine discussions outside of the fall and winter seasons.[

45] Vaccines that are unlikely to require formula changes or those that offer multiple year duration of protection (e.g. pneumococcal, herpes zoster) could be administered outside of the fall season to allow for communication to be focused on influenza and COVID-19 during the peak respiratory virus season.

Engaging Providers for Fall 2024 Delivery

With the proposed update in the 2024/2025 COVID-19 vaccine approval process, there is an opportunity to engage public health, healthcare systems and providers on the planning distribution and administration of COVID-19 vaccine to the public. Having clear and early recommendations will allow healthcare systems and providers to have the appropriate supply and can reduce wastage of the vaccine. By adapting the communication with providers to match that of influenza, there is a potential to increase the number of COVID-19 immunizations and enhance the knowledge of who should receive the 2024/2025 vaccine and when it should be administered.

The location of administration of influenza and COVID-19 vaccines differ significantly. Pharmacies have administered almost every adult dose of the 2023/2024 COVID-19 vaccine (92.7% of all doses).[

46] This is not the case with the 2023/2024 adult influenza vaccine where administration location is more split between pharmacies (59.5% of doses) and medical offices (40.5% of doses).[

47] There was also a significant difference in the number of doses administered between the two vaccines, where in March 2024 the 2023/2024 COVID-19 vaccine administered was more than half that of influenza.[

46,

47] This disparity in where vaccines are being administered points to the need to engage more healthcare providers beyond pharmacy to take a more active role in COVID-19 vaccine administration.

With the differences in the vaccine uptake of influenza and COVID-19 vaccines, there should be increased need to educate the providers on the shared risk factors between these two infections. With the ACIP/CDC providing clear recommendations of coadministration of the two vaccines, healthcare providers should be strongly encouraged to administer both vaccines on the same date for those ≥ 6 months of age.[

48] The disconnect between the number of people receiving influenza versus COVID-19 vaccines indicates that if the COVID-19 discussions were occurring at the point of care, there could be a higher vaccine uptake for future COVID-19 vaccines.

Addressing Key Barriers to COVID-19 Vaccine Uptake

With the low uptake of the 2023/2024 COVID-19 vaccine, there is a need for strategies that can help healthcare providers increase COVID-19 vaccine uptake. These include programs that can address vaccine complacency, convenience, and confidence. We propose this can be facilitated with a structured approach to improve vaccine access, simplifying vaccine messaging and the delivery of COVID-19 vaccines and strategies that address misinformation and disinformation surrounding COVID-19 and its vaccines.

Improving Vaccine Access

Lack of COVID-19 vaccine access could be contributing to both vaccine complacency and convenience. When COVID-19 vaccines were first available, the majority of the public were willing to seek out vaccine locations and to wait for the opportunity to receive a vaccine that could reduce their risk from this emerging infection. As the pandemic has progressed and public health measures have been rolled back, there is now a complacency amongst many individuals on the need for receiving additional COVID-19 doses. We must not lose touch that every healthcare provider regardless of their area be in research, clinical, academia, public health, and policy are all touch points to enhance trust and overcome mistrust. An opportunity to provide evidence-based health guidance and overcome misinformation.

The last 4 years of the COVID-19 pandemic has demonstrated that the SARS-CoV-2 virus is unpredictable and will likely continue to evolve. Future variants may be associated with a higher risk of severe outcomes and long COVID, especially in those individuals who have missed recommended vaccine doses. To protect against future variants there is a need to actively engage all groups (e.g. public health, primary care providers, pharmacists, community groups and partners) and provide them with tools to facilitate a discussion on the potential impact of COVID-19 on their health and steps that can be taken to lower their risk. This helps to ensure all Americans have the information and access to make the decisions for mitigating their COVID-19 risk.

Simplifying Vaccine Messaging and the Delivery of COVID-19 Vaccines

The success of the public health vaccination program is contingent on a simple narrative on the role of vaccines to protect the individual, their circle of contacts and their community.[

49] Vaccine messaging is crucial. Simply providing individuals with more vaccine and disease information was shown in one study to increase misperceptions or reduce vaccination intention.[

50]

Healthcare provider recommendations are strongly associated with vaccine uptake.[

51] Individual doctors are the most trusted source, with 93% of the public saying they have a great deal or a fair amount of trust in their own doctor to make the right recommendations on health issues.[

40] By making a strong recommendation to receive a vaccine, many patients are willing to accept it with little further discussion. Provider recommendations are especially effective if they take the form of a presumptive offer (

Table 5).[

52] With this format, the default response is to accept vaccine uptake.[

51] One study found that the use of presumptive language with respect to vaccine discussions, significantly increased vaccine uptake and lowered vaccine resistance.[

53] The advantage of this method for healthcare providers is that it has been shown to be time-sensitive and can simplify vaccine discussions with patients.

Occasionally, immunizers encounter a person who is hesitant to receive a vaccine despite a presumptive recommendation. It is important for healthcare providers to explore the reason(s) for hesitancy and engage the patient/caregiver in a discussion that could address their concern(s).[

54] As mentioned above, the vast majority of people who had concerns regarding the use of the COVID-19 were hesitant based on three categories:

Like with patients, there is some complacency regarding COVID-19 with healthcare providers. By providing them with tools and messages that can facilitate immunization for future COVID-19 seasons. An appropriate first step would be to link COVID-19 and influenza communication. This could stress that the overlap in the high-risk groups and the importance of receiving both vaccines for optimal protection.

Another strategy is to engage trusted community messengers and support. This should be strongly encouraged to reach many different groups. These messengers play an important role in efforts to combat the proliferation of health misinformation.

Key Takeaways and Recommendations

Throughout this paper we have highlighted the challenges of previous seasons and opportunities to address key barriers for immunization.

Table 6 provides key recommendations for government, public health officials and healthcare providers to utilize to increase COVID-19 vaccine uptake in the future and protect the population against this ongoing threat. It is important to note that, there have already been significant organizing efforts to bring together the whole health ecosystem to address vaccine uptake concerns, for example the Coalition for Trust in Health & Science, Immunize.org, The Public Good Projects, Shots Heard Round the World. Organizations such as these have laid a very solid foundation upon which we need to stand and not reinvent strategies and resources for each season.

Funding: This work was supported by Moderna, Inc.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Michael Boivin of CommPharm Consulting Inc. for providing medical writing support.

Conflicts of Interest

J.A.M. and H.H. are employees of and shareholders in Moderna Inc.

References

- The Commonwealth Fund. Two Years of U.S. COVID-19 Vaccines Have Prevented Millions of Hospitalizations and Deaths. [CrossRef]

- CDC. COVID Data Tracker. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Accessed April 12, 2024. https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker.

- CDC. Trends in United States COVID-19 Hospitalizations, Deaths, Emergency Department (ED) Visits, and Test Positivity by Geographic Area. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Accessed April 15, 2024. https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker.

- CDC. Adult Coverage and Intent. Published April 9, 2024. Accessed April 15, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/imz-managers/coverage/covidvaxview/interactive/adult-coverage-vaccination.html.

- CDC. Child Coverage and Parental Intent for Vaccination. Published March 6, 2024. Accessed April 15, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/imz-managers/coverage/covidvaxview/interactive/children-coverage-vaccination.html.

- CDC. COVID-19 Vaccinations in the United States. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Accessed April 15, 2024. https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker.

- Regan JJ. Use of Updated COVID-19 Vaccines 2023–2024 Formula for Persons Aged ≥6 Months: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices — United States, September 2023. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023;72. [CrossRef]

- CDC. COVID-NET - COVID-19-Associated Hospitalization Surveillance Network: A Respiratory Virus Hospitalization Surveillance Network (RESP-NET) Platform. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Published February 11, 2020. Accessed May 6, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/covidnetdashboard/de/powerbi/dashboard.html.

- CDC. Laboratory-Confirmed Influenza Hospitalizations. Accessed May 6, 2024. https://gis.cdc.gov/GRASP/Fluview/FluHospRates.html.

- Zambrano LD, Newhams MM, Simeone RM, et al. Characteristics and Clinical Outcomes of Vaccine-Eligible US Children Under-5 Years Hospitalized for Acute COVID-19 in a National Network. The Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal. 2024;43(3):242. [CrossRef]

- Link-Gelles R. Estimates of Bivalent mRNA Vaccine Durability in Preventing COVID-19–Associated Hospitalization and Critical Illness Among Adults with and Without Immunocompromising Conditions — VISION Network, September 2022–April 2023. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023;72. [CrossRef]

- Havers, FP. COVID-19–Associated Hospitalizations among Infants, Children and Adults — COVID-NET, January–August 2023. Accessed May 6, 2024. https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/132883.

- CDC. Health Policy Data Requests - Percent of U.S. Adults 55 and Over with Chronic Conditions. Published February 7, 2019. Accessed May 6, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/health_policy/adult_chronic_conditions.htm.

- CDC. Underlying Medical Conditions Associated with Higher Risk for Severe COVID-19: Information for Healthcare Professionals. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Published , 2024. Accessed May 6, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/clinical-care/underlyingconditions. 12 April.

- Taylor, C.A. COVID-19–Associated Hospitalizations Among U.S. Adults Aged ≥65 Years — COVID-NET, 13 States, January–August 2023. <italic>MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep</italic>. 2023;72. [CrossRef]

- CDC. Preliminary Flu Burden Estimates, 2022-23 Season. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Published November 22, 2023. Accessed May 6, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/about/burden/2022-2023.htm.

- CDC. The Changing Threat of COVID-19. Published March 1, 2024. Accessed April 15, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/ncird/whats-new/changing-threat-covid-19.html.

- Adams ML, Katz DL, Grandpre J. Population-Based Estimates of Chronic Conditions Affecting Risk for Complications from Coronavirus Disease, United States - Volume 26, Number 8—August 2020 - Emerging Infectious Diseases journal - CDC. [CrossRef]

- Kompaniyets L. Underlying Medical Conditions and Severe Illness Among 540,667 Adults Hospitalized With COVID-19, March 2020–March 2021. <italic>Prev Chronic Dis</italic>. 2021;18. [CrossRef]

- Bench2Practice. Hospitalizations* by Underlying Medical Condition. Accessed May 7, 2024. https://atlas.modernatx.com/en-US/bench2practice/Interactive-dashboard.

- Kopel H, Bogdanov A, Winer-Jones JP, et al. Comparison of COVID-19 and Influenza-Related Outcomes in the United States during Fall–Winter 2022–2023: A Cross-Sectional Retrospective Study. <italic>Diseases</italic>. 2024;12(1):16. [CrossRef]

- CDC. Long COVID - Household Pulse Survey - COVID-19. Published , 2024. Accessed May 6, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/covid19/pulse/long-covid.htm.

- United States Census Bureau. International Database. Accessed April 28, 2024. https://www.census.gov/data-tools/demo/idb/#/pop?COUNTRY_YR_ANIM=2021&menu=popViz&COUNTRY_YEAR=2021&TREND_RANGE=1950,2100&TREND_STEP=10&TREND_ADD_YRS=&POP_YEARS=2024&CCODE=US&CCODE_SINGLE=US&popPages=BYAGE&ageGroup=5Y.

- Zheng YB, Zeng N, Yuan K, et al. Prevalence and risk factor for long COVID in children and adolescents: A meta-analysis and systematic review. <italic>J Infect Public Health</italic>. 2023;16(5):660-672. [CrossRef]

- Statistics Canada Government of Canada. Experiences of Canadians with long-term symptoms following COVID-19. Published December 8, 2023. Accessed May 7, 2024. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/75-006-x/2023001/article/00015-eng.htm.

- 26. Koumpias AM, Schwartzman D, Fleming O. Long-haul COVID: healthcare utilization and medical expenditures 6 months post-diagnosis. BMC Health Services Research, 1010. [CrossRef]

- Michael B, Wood G, Sargent B, et al. Post-COVID cognitive deficits at one year are global and associated with elevated brain injury markers and grey matter volume reduction: national prospective study. Published online January 5, 2024. [CrossRef]

- CDC. RESP-NET Interactive Dashboard. Published October 6, 2023. Accessed April 15, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/surveillance/resp-net/dashboard.html.

- Epic Research. Respiratory Illnesses. Epic Research. Accessed April 15, 2024. https://epicresearch.org/data-tracker/respiratory-illnesses.

- Kopel H, Bogdanov A, Winer-Jones JP, et al. Comparison of COVID-19 and Influenza-Related Outcomes in the United States during Fall–Winter 2022–2023: A Cross-Sectional Retrospective Study. <italic>Diseases</italic>. 2024;12(1):16. [CrossRef]

- CDC. Influenza Vaccination Coverage, Adults: COVIDVaxView. Published April 11, 2024. Accessed April 15, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/fluvaxview/dashboard/vaccination-adult-coverage.html.

- CDC. Monitoring Variant Proportions. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Published March 28, 2020. Accessed April 15, 2024. https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker.

- Wang Q, Guo Y, Bowen A, et al. XBB.1.5 monovalent mRNA vaccine booster elicits robust neutralizing antibodies against emerging SARS-CoV-2 variants. Published online December 6, 2023:2023.11.26.568730. [CrossRef]

- Gayed J, Diya O, Lowry FS, et al. Safety and Immunogenicity of the Monovalent Omicron XBB.1.5-Adapted BNT162b2 COVID-19 Vaccine in Individuals ≥12 Years Old: A Phase 2/3 Trial. <italic>Vaccines</italic>. 2024;12(2):118. [CrossRef]

- Chalkias S, McGhee N, Whatley JL, et al. Safety and Immunogenicity of XBB.1.5-Containing mRNA Vaccines. Published online September 7, 2023:2023.08.22.23293434. [CrossRef]

- Andersson NW, Thiesson EM, Hviid A. Adverse Events After XBB.1.5-Containing COVID-19 mRNA Vaccines. <italic>JAMA</italic>. 2024;331(12):1057-1059. [CrossRef]

- DeCuir J. Interim Effectiveness of Updated 2023–2024 (Monovalent XBB.1.5) COVID-19 Vaccines Against COVID-19–Associated Emergency Department and Urgent Care Encounters and Hospitalization Among Immunocompetent Adults Aged ≥18 Years — VISION and IVY Networks, September 2023–January 2024. <italic>MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep</italic>. 2024;73. [CrossRef]

- Kopel H, Araujo AB, Bogdanov A, et al. Effectiveness of the 2023-2024 Omicron XBB.1.5-containing mRNA COVID-19 vaccine (mRNA-1273.815) in preventing COVID-19-related hospitalizations and medical encounters among adults in the United States: An interim analysis. Published online April 12, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Wallace M. Evidence to Recommendations Framework: Accessed May 6, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2023-09-12/11-COVID-Wallace-508.pdf.

- Harris E. Amid Health Misinformation, Most Trust Physicians for Truth. <italic>JAMA</italic>. 2023;330(12):1128. [CrossRef]

- Lakshmi Panagiotakopouluos. Next Steps for the COVID-19 Vaccine Program. Presented at: ACIP Meeting; 2024/02/28. Accessed April 15, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2024-02-28-29/07-COVID-Panagiotakopoulos-508.pdf.

- CDC. 2023-2024 CDC Flu Vaccination Recommendations Adopted. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Published June 29, 2023. Accessed April 28, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/spotlights/2022-2023/flu-vaccination-recommendations-adopted.htm.

- Chatham-Stephens K. An update on COVID-19 vaccination coverage. Accessed May 6, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2024-02-28-29/03-COVID-Chatham-Stevens-508.pdf.

- Shen AK, Browne S, Srivastava T, Kornides ML, Tan ASL. Trusted messengers and trusted messages: The role for community-based organizations in promoting COVID-19 and routine immunizations. <italic>Vaccine</italic>. 2023;41(12):1994-2002. [CrossRef]

- CDC. Adult Immunization Schedule by Age. Published March 11, 2024. Accessed April 16, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/schedules/hcp/imz/adult.html.

- CDC. Adult Vaccinations Administered. Published April 9, 2024. Accessed April 16, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/imz-managers/coverage/covidvaxview/interactive/adult-vaccinations-administered.html.

- CDC. Influenza Vaccinations Administered in Pharmacies and Physician Medical Offices, Adults, United States | FluVaxView | Seasonal Influenza (Flu). Published April 11, 2024. Accessed April 16, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/fluvaxview/dashboard/vaccination-administered.html.

- CDC. Interim Clinical Considerations for Use of COVID-19 Vaccines. Published March 1, 2024. Accessed April 16, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/covid-19/clinical-considerations/covid-19-vaccines-us.html.

- Shanahan EA, DeLeo RA, Albright EA, et al. Visual policy narrative messaging improves COVID-19 vaccine uptake. <italic>PNAS Nexus</italic>. 2023;2(4):pgad080. [CrossRef]

- Nyhan B, Reifler J, Richey S, Freed GL. Effective Messages in Vaccine Promotion: A Randomized Trial. <italic>Pediatrics</italic>. Published online March 3, 2014:peds.2013-2365. [CrossRef]

- Brewer NT, Chapman GB, Rothman AJ, Leask J, Kempe A. Increasing Vaccination: Putting Psychological Science Into Action. <italic>Psychol Sci Public Interest</italic>. 2017;18(3):149-207. [CrossRef]

- Brewer NT, Hall ME, Malo TL, Gilkey MB, Quinn B, Lathren C. Announcements Versus Conversations to Improve HPV Vaccination Coverage: A Randomized Trial. <italic>Pediatrics</italic>. 2016;139:e20161764. [CrossRef]

- Opel DJ, Heritage J, Taylor JA, et al. The Architecture of Provider-Parent Vaccine Discussions at Health Supervision Visits. <italic>Pediatrics</italic>. 2013;132(6):1037-1046. [CrossRef]

- Fogarty CT, Crues L. How to Talk to Reluctant Patients About the Flu Shot. <italic>fpm</italic>. 2017;24(5):6-8.

- Infodemiology. Infodemiology training for public health. Accessed May 28, 2024. https://training.infodemiology.com/publichealth.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).