1. Introduction

The International Labour Organization estimates that 63% (164 million) of foreign migrants have jobs, with 58% of them being men [

1]. These migrant workers originating from lower-income countries fill critical gaps in higher-income countries, working in the manufacturing, construction, transportation, storage, and agriculture sectors. Notably, substantial global research, including studies by [

2,

3], underscore the heightened vulnerability of migrant workers to injury, disease, and fatal accidents in comparison to domestic workers, particularly in the construction industry. This risk disparity is evident in 73% of countries, as revealed by a recent analysis of ILO data on work-related fatalities, with migrant workers in the construction industry experiencing a higher incidence rate of fatal occupational injuries than their domestic counterparts [

4]. Migrant workers are often injured and suffer fatalities from falling from heights, heavy metal falling on them, or car accidents [

5]. In 2018, 13% of fatalities in Italian and Spanish construction sites were migrant workers [

6]. ‘Slipping, tripping, or falling on the same level’ are reported as the cause of most injuries, while ‘falling from a height’ [

7,

8], ‘hit by an object,’ ‘shocked by the electrical current’, or ‘run over by moving machinery or cars’ are reported as the cause of many more occupational deaths to migrant workers than those of their domestic counterparts [

9,

10]. Studies have also shown that migrant workers face more significant non-fatal accidents than their domestic counterparts [

11]. Also, about 73% of fatal accidents occur among migrant workers rather than domestic workers [

12]. For example, in Qatar, there were 37.34 non-fatal occupational injuries per 100,000 migrant workers compared to 1.58 for domestic workers [

13]. Similarly, a study from South Korea reported a 1.8-fold higher fatality rate of work-related injuries among Chinese migrant workers compared to Korean-Chinese workers [

12]. Research has also shown that more accidents and injuries occur during the summer, especially among migrant workers [

14]. This may be due to longer work hours, better weather, and more outdoor time [

15].

Saudi Arabia (SA) has recently become a labour-importing country, and the number of migrant workers has gradually increased, particularly in the construction industry; most construction workers are Filipinos, Indians, Pakistanis, and Bangladeshis [

16]. In 2021, 6.17 million migrants (76.4% of the workforce) worked in Saudi Arabia's private industry [

17], where approximately 51% of the 69,241 occupational injuries in 2014 occurred in the construction [

18,

19]. Abukhashabah et al. (2020) [

20] noted that the most common injuries and deaths in construction in Jeddah arose from falls from height and electrical shock. However, the demographics, seasons, and details of these kinds of injuries among migrants and domestic workers remain unclear. Despite studies on injuries and occupational accidents in SA’s construction industry [

20,

21,

22], limited information has emerged on the influence of seasons on such injuries since 2011 [

23]. Recognising the seasonal impact on injuries and related policies is vital for addressing weather-related hazards and workload fluctuations, to enhance worker safety. Furthermore, the causes and differences between migrant and Saudi workers’ injuries and occupational accident rates have not been fully explored using data from the General Organization for Social Insurance (GOSI). Thus, this study is intended to address the following gaps: first, to explore the characteristics of recent accidents and demographic data from the GOSI using descriptive statistics; second, to compare seasonal differences in the frequency and nature of accidents; and third, in comparing accidents rates among migrant workers and their domestic counterparts.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

This retrospective study examined the causes of accidents and injuries among migrant and Saudi (domestic) construction workers using a curated dataset obtained from the GOSI database. The GOSI was requested to provide data (including demographic data) for all migrant and domestic workers above 18 years of age in the construction industry (both public and private) from 2014 to 2019 (2020 and 2021 were not collected because of the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic), including fatal and non-fatal work- related accidents and injuries with the month of occurrence. For comparative purposes, the GOSI's annual reports were also retrieved, including data on the Saudi workforce size, industrial accidents, and injuries among migrant and domestic construction workers.

2.2. Ethical Considerations

The data obtained from the GOSI were fully anonymized. As this was a secondary data analysis; ethical approval was not required from the University’s Human Ethics sub-committee.

2.3. GOSI Data

The GOSI dataset contains comprehensive information that has been collected and categorized for the purpose of analysing occupational accidents and injuries among workers in Saudi Arabia.

Table 1 provides a comprehensive breakdown of the data, encompassing worker categorisation, accident types, seasonal variations, Economic sectors, and demographic details.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

First, GOSI data were used to compare fatal and non-fatal accidents and injuries in Saudi Arabia’s construction industry to those in other industries using the following formula:

Employing percentages, the study scrutinised the associations between worker age group, seasonal accident types, and the outcomes of these incidents. In addition, chi-square tests were used to evaluate the associations between migrant and domestic worker status by age, and accident outcomes for migrant and domestic workers by season. A p-value of 0.05 was used to consider significancy in all statistical analyses. Data were analysed using SPSS version 27 for Windows and Microsoft Excel 2021.

3. Results

3.1. Trends of Accidents in the Saudi Construction Industry

Table 2 shows the workforce and accident trends in the construction industry and all other industries between 2014 to 2019. On average, 41.4% of all accidents from 2014 to 2019 were reported in the construction industry. The average fatal accident rate (per 100,000) for the same period was 4.2% in the construction industry, slightly lower than other industries' average of 4.6%. However, there were 5.4 non-fatal accidents for every 1000 construction workers, compared to 5.1 for all other industries.

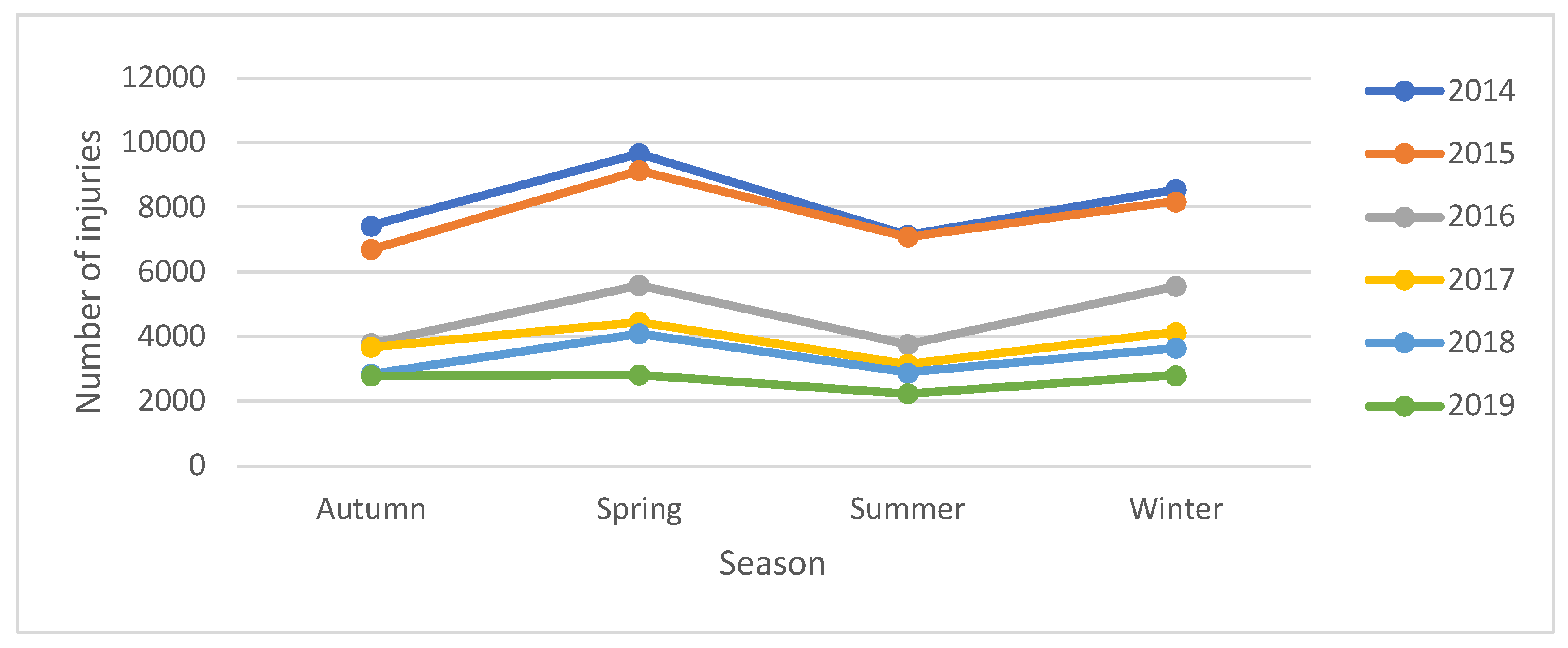

Figure 1 shows the number of accidents and injuries affecting construction industry workers throughout the various seasons between 2014 and 2019.

3.2. Fatal Accidents: Among Migrant and Domestic Workers

Table 3 presents the number and percentage of accident fatalities among domestic and migrant workers in the Saudi construction industry. The overall percentage of fatalities was the same (0.1%) for both migrant and domestic workers, but chi-square analyses showed significant differences in fatality rates between the two groups. It was noted that proportionately more fatal accidents were recorded in the age group 30-39 years for migrant workers and in the 20-29 age group for domestic workers (p< 0.001). In terms of accident types, there were proportionately more fatalities from transport and car accidents for both migrant and domestic workers (57.7% and 95.0% respectively). For migrant workers, the second highest fatalities were from falls (19.3%) and for domestic workers no other patterns were observed. No significant difference of fatalities by seasons were found for both migrant and domestic workers (p=0.90).

3.3. Non-Fatal Accidents among Migrant and Domestic Workers

Table 4 shows the number and percentage of non-fatal accidents for migrant and domestic workers. The results show proportionately more migrant workers experience non-fatal accidents (4.5%) than domestic workers (0.4%). When examining non-fatal accidents by age group, a proportionately higher non-fatal accidents was recorded in the age group 30-39 for migrant workers, while among domestic workers the 20-29 age group showed a significantly higher incidence rate (p<0.001).

For types of accident, both migrant and domestic workers experienced notably higher rates of ‘Fall’ accidents (32.8% and 31.5%, respectively) followed by “Struck and Collision accidents” (26.9% and 20.7%, respectively), (p<0.01). Again, no significant difference in fatalities by seasons were found for both migrant and domestic workers (p=0.378)

3.4. Association between Type of Accident and Its Outcome Across Domestic and Migrant Workers

Table 5 presents four categories of outcomes for the accidents: full recovery, under-recovery, permanent disability, and fatality. The analysis shows a significant difference in accident outcomes for migrant and domestic workers (p=0.02). Whilst most migrant and domestic workers made a full recovery from a fall, significantly more domestic workers made a full recovery than migrant workers (66.8% and 60.3%, respectively). Furthermore, whilst no fatalities from a fall were reported for domestic workers, fatalities from a fall were reported for a small proportion of migrant workers (0.4%). In terms of Strike and Collision, Rubbing and Abrasion, and Bodily Reaction, the analysis shows no significant difference in outcomes for migrant and domestic workers (p = 0.68, 0.99 and 0.44, respectively). However, domestic workers recorded significantly more full recovery than migrant workers for all three types of accidents. Both migrant and domestic workers recorded 0.0% of fatalities from Rubbing and Abrasion and Bodily Reaction, while migrant workers reported a small proportion from Strike and Collision (0.3%), while there were no fatalities among domestic workers from this type of accident (0.0%).

There is a significant difference between the outcomes of other types of accident and transport and car accidents among migrant and domestic workers (p = 0.05, and <0.005 respectively). However, in this case, the results show that migrant workers had a higher proportion of full recovery than domestic workers in other types of accidents (67.9% and 54.9%, respectively), while both made the same proportion of under-recovery in transport and car accidents (51.8%). Furthermore, domestic workers have a higher percentage of fatalities from other types of accidents and transport and car accidents (1.2% and 17.9% respectively) than migrant workers (0.4% and 8.5%, respectively).

4. Discussion

Using Government data, this study examined the prominent types of accidents, their relationships with demographics, seasonality of the events and the outcome of occupational accidents and injuries among migrant and domestic construction workers in Saudi Arabia from 2014 to 2019. During this period, the construction industry exhibited the highest occupational accident and injury rate, accounting for 41.4% of all industrial incidents, albeit with slightly fewer fatal accidents (4.2% vs. 4.6%). Migrant workers, constituting 89% of the workforce (n=2,765,611), experienced a disproportionately higher share of both fatal and non-fatal accidents compared to their domestic counterparts, who accounted for only 11% (n=347,044) of the total cases. Furthermore, these incidents demonstrated seasonal variation, with a higher prevalence during spring and a lower incidence during summer, however, there was no significant difference recorded. The annual distribution revealed the highest accident counts in 2014 and 2015, whereas 2019 recorded the lowest accident count, a trend that could be potentially attributed to stricter regulations and improved reporting systems.

Significantly more migrant workers experienced non-fatal accidents when compared to domestic workers. This study highlighted the increased susceptibility of migrant workers to severe injuries and permanent impairments as opposed to their domestic counterparts. However, there is a need to be cautious when interpreting these results. The higher vulnerability of migrant workers to accidents in the construction industry could be due to the relatively higher number of migrant workers than domestic workers in the industry. Nonetheless, recent meta-analysis studies across various countries consistently showed higher risks for work-related injuries and fatalities among migrant construction workers compared to domestic workers [

23,

24]. For example, a study in Spain found that migrant workers had a higher risk of fatal accidents than domestic workers [

25], and studies from Denmark and South Korea found higher risks of non-fatal accidents among migrant workers [

26,

27]. Factors like cultural and language differences increase the susceptibility of migrant workers to accidents and injuries and can hinder effective communication resulting in an increased risk of accidents [

28,

29]. Insufficient safety education increases the risk, as migrants often do not have access to adequate training and protective equipment [

30]. Additionally, migrant workers frequently engage in physically strenuous and perilous labour, enduring extended work hours in the construction industry [

31]. Son et al. (2013) [

26] suggested that vulnerability among migrant workers can be reduced by implementing various measures, such as providing safety training in multiple languages, offering cultural sensitivity programs, and enforcing safety regulations more strictly.

Age played a discernible role in accident occurrence, with migrants aged 30-39 and domestic workers aged 20-29 facing a higher risk of fatal and non-fatal accidents. A Qatari-based study reported that migrant workers aged between 25-34 and 35-44 faced the highest risk of occupational injuries compared to younger and older workers reported that migrant workers aged between 25-34 and 35-44 faced the highest risk of occupational injuries compared to younger and older workers [

13]. Similarly, workers aged 25-44 were found to exhibit a higher rate of occupational injuries than those in other age groups [

32]. This propensity may stem from the physically demanding nature of the work, coupled with over-confidence due to significant work experience, thereby increasing exposure to workplace hazards. Additionally, family responsibilities among workers in this age group may contribute to their pursuit of more demanding jobs, such as those within the construction industry, to provide for their families; future studies may investigate such an association.

Among migrant construction workers, falls and struck-by, collision, were the most prevalent types of non-fatal accidents. Literature has consistently identified falls as a major hazard within the construction industry, particularly for workers operating at heights or on unstable surfaces. In a study from Ethiopia, 16.1% of construction site workers fell from height and most of these workers were plasterers [

33]. Similarly, Tuma et al. [

34] reported that most fall victims in construction workplace were migrant workers. Likewise, struck-by incidents involving contact with objects or equipment are frequently cited as leading causes of injuries and fatalities during construction activities [

20]. The prominence of these accident types among migrant workers suggests that they may face additional risks owing to language and cultural barriers, inadequate safety training, and suboptimal safety equipment. Several studies from different regions have also reported similar trends, as studies from Italy and Malaysia demonstrated that migrants are more frequently implicated in workplace injuries than domestic workers [

9,

35].

This study showed that occupational accidents and injuries are more frequent among migrant workers during the spring season and declining throughout the summer, though the difference was not statistically significant. This contrasts with prior research by Ammar, (2019), who reported the highest number of occupational accidents and injuries during the spring, followed by the summer season [

22]. This could be attributed to variations in datasets and legislative changes aimed at restricting outdoor work during specific hours. The dynamic nature of seasonal patterns in workplace accidents suggest that these patterns can evolve over time. Another reason for this change might be because of Legislative Decree No. 3337 of 14/05/2014, which stated that ‘No worker shall labour in the outdoor from 12:00 pm to 3:00 pm throughout the summer season (June 15 - September 15)’ [

19]. Consequently, the number of summer injuries and accidents could be lower because of less and/or shorter duration of activity. This could also explain why there seemed to be more injuries during the spring. The construction industry may increase its work-related activities during spring, to achieve summer deadlines which may increase stress, thereby leading to accidents, and injuries.

Regarding accident outcomes, domestic workers in Saudi construction industry exhibited a higher proportion of full recovery than migrant workers from all accidents except the Transport and Car Accidents. Migrant workers have more full recovery and a lower proportion of fatalities from Transport and Car Accidents than domestic workers. Our findings are also in line with the findings of Arndt [

36]

that non-German workers face higher risk of fatal and non-fatal injuries from falls and from falling objects. However, non-Germans recorded fewer injuries from transport and car accidents compared to German workers [

36]

. This is because domestic workers often use their personal vehicles for commuting, while migrant workers rely on public transport, which may be safer and less prone to accident.

4.1. Research Limitations

This is a retrospective study based on secondary data; future studies addressing occupational accidents and injuries should consider the reasons higher injury rates among the 20-49 age group of migrant workers. Therefore, additional observational studies based on primary data are required. There were certain limitations in data collection, as follows.

There is a possibility of underreporting and restricting data collection on workplace accidents, especially non-fatal accidents, in developing and developed countries [

37]. Hence, firms may be unwilling to share information about injuries sustained, impacting the findings of secondary studies such as ours.

Furthermore, the ILO recommends robust data collection that includes physical and psychological accidents and injuries [

38]. However, the GOSI database is limited to occupational accidents and injuries; it only focuses on physical injuries and does not consider psychological problems that could impact the workforce. Consequently, exploring work-related stress and psychosocial problems in SA is challenging.

4.2. Recommendations for Future Works

Based on the findings, it is recommended that safety measures in the construction industry be drastically improved, particularly among migrant workers. These include:

Developing more effective and structured safety training programs using advanced technology such as wearable sensors and implementing safety audits and inspections.

Employers and construction site managers should ensure that migrant workers use personal protective equipment appropriately at all times.

More attention should be paid to migrant workers with less experience and knowledge of safety measures, including safety training in their native languages.

Given that psychosocial factors and musculoskeletal injuries are associated with the construction industry, a comprehensive risk management technique must be implemented in order to effectively reduce these risks [

37,

38].

Therefore, further studies should be conducted to determine the problems related to poor mental and physical health among migrant construction workers in SA.

5. Conclusion

This study, conducted using data from 2014 to 2019, provides valuable insights into the common occupational hazards and injury patterns observed among migrant construction workers in Saudi Arabia. A clear hierarchy of accident types was identified in the construction industry, with falls, struck-by, collisions, rubbing and abrasion, bodily reactions, and transport and car accidents being the most frequently occurring, highlighting the various and inherent risks within the construction industry. The study also indicated that accidents and injuries affecting migrant workers occurred more frequently during spring and winter. Younger workers for both migrants and domestic workers were found to be at higher risk of experiencing more severe injuries, stressing the importance of implementing focused safety interventions that are tailored to the specific age group in order to reduce the risks of injuries among this population.

Author Contributions

The study was designed and prepared by MA, FM, PC, and RS. MA and FM designed the study. MA conducted an analysis of the data. The manuscript's final draft was approved by all authors.

Funding

Financial support was received for the research, authorship, and publication of this article. This work was funded by Saudi Electronic University as part of a PhD program for the first author.

Data Availability Statement

Some or all data, models, or code used during the study were provided by a third party. Direct request for these materials may be made to the provider as indicated in the Acknowledgments.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Dr. Abdullah Alharbi, Eng. Muataz Al-Khalifah, and Ms. Afnan Alsheikh from General Organization for Social Insurance (GOSI) for providing anonymous data on occupational accidents and injuries.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- World Health Organization. WHO/ILO: Almost 2 million people die from work-related causes each year. Comun Prensa Conjunto 2021. https://www.who.int/news/item/17-09-2021-who-ilo-almost-2-million-people-die-from-work-related-causes-each-year.

- Hargreaves S, Rustage K, Nellums LB, McAlpine A, Pocock N, Devakumar D, et al. Occupational health outcomes among international migrant workers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob Heal 2019;7:e872–82. [CrossRef]

- Onarheim KH, Egli-Gany D, Aftab W. Occupational health outcomes among international migrant workers. Lancet Glob Heal 2019;7:e1614. [CrossRef]

- Brian T. Occupational Fatalities among International Migrant Workers: A Global Review of Data Sources 2021:53. www.iom.int (accessed August 22, 2023).

- International Labour Organization. Construction: A hazardous work.” Occup. Heal. Saf. 2015; 1–2 . https://www.ilo.org/global/topics/safety-and-health-at-work/areasofwork/hazardous-work/WCMS_356567/lang--en/index.htm. Accessed Mar. 15, 2023.

- Shepherd R, Lorente L, Vignoli M, Nielsen K, Peiró JM. Challenges influencing the safety of migrant workers in the construction industry: A qualitative study in Italy, Spain, and the UK. Saf Sci 2021;142. [CrossRef]

- Shafique M, Rafiq M. An overview of construction occupational accidents in Hong Kong: A recent trend and future perspectives. Appl Sci 2019;9. [CrossRef]

- Leavy, N. , and S. Flavin. A review of construction-related fatal accidents in Ireland, 1989-2016. Dublin: Health and Safety Authority 2019. https://www.hsa.ie/eng/publications_and_forms/publications/construction/a_review_of_construction-related_fatal_accidents_in_ireland_1989_-_2016.pdf.

- Williams OS, Hamid RA, Misnan MS. Analysis of Fatal Building Construction Accidents: Cases and Causes. J Multidiscip Eng Sci Technol (JMEST), 2017; 8030–8031. http://www.jmest.org/wp-content/uploads/JMESTN42352371.pdf.

- Solomon O, Eucharia E, Onoh Felix. Accidents in Building Construction Sites in Nigeria: a Case of Enugu State. Int J Innov Res Dev 2016;5:244–8.

- International Organization for Migration. Migrant Workers Face Heightened Risk of Death and Injury: New IOM Report | International Organization for Migration. 2024.

- Lee JY, Cho S il. Prohibition on changing workplaces and fatal occupational injuries among chinese migrant workers in South Korea. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2019;16. [CrossRef]

- Al-Thani H, El-Menyar A, Consunji R, Mekkodathil A, Peralta R, Allen KA, et al. Epidemiology of occupational injuries by nationality in Qatar: Evidence for focused occupational safety programmes. Injury 2015;46:1806–13. [CrossRef]

- Acharya P, Boggess B, Zhang K. Assessing heat stress and health among construction workers in a changing climate: A review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2018;15. [CrossRef]

- Berhanu F, Gebrehiwot M, Gizaw Z. Workplace injury and associated factors among construction workers in Gondar town, Northwest Ethiopia. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2019;20. [CrossRef]

- Brika SKM, Adli B, Chergui K. Key Sectors in the Economy of Saudi Arabia. Front Public Heal 2021;9. [CrossRef]

- Puri-Mirza A. Saudi Arabia: total number of non-national employed workers in the private sector 2021 | Statista 2022. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1325038/saudi-arabia-total-number-of-non-national-employed-workers-in-the-private-sector/ (accessed March 14, 2023).

- Mosly, I. Safety Performance in the Construction Industry of Saudi Arabia. Int J Constr Eng Manag 2015;4:238–47. [CrossRef]

- General Organization for Social Insurance (GOSI). Annual statistical report 1443H 2021. https://www.gosi.gov.sa/en/StatisticsAndData/AnnualReport (accessed March 15, 2023).

- Abukhashabah E, Summan A, Balkhyour M. Occupational accidents and injuries in construction industry in Jeddah city. Saudi J Biol Sci 2020;27:1993–8. [CrossRef]

- Asiri SM, Kamel S, Assiri AM, Almeshal AS. The Epidemiology of Work-Related Injuries in Saudi Arabia Between 2016 and 2021. Cureus 2023;15:e35849. [CrossRef]

- Ammar A, Ammar AI. The Effect of Season on Construction Accidents in Saudi Arabia. Emirates J Eng Res 2019; 24: Iss. 4, Article 5. Available at: https://scholarworks.uaeu.ac.ae/ejer/vol24/iss4/5.

- Guan Z, Yiu TW, Samarasinghe DAS, Reddy R. Health and safety risk of migrant construction workers–a systematic literature review. Eng Constr Archit Manag 2022. [CrossRef]

- International Labour Organization. Construction: a hazardous work. Occup Heal Saf 2015:1–2. https://www.ilo.org/safework/areasofwork/hazardous-work/WCMS_356567/lang--en/index.htm%0Ahttps://www.ilo.org/global/topics/safety-and-health-at-work/areasofwork/hazardous-work/WCMS_356567/lang--en/index.htm (accessed March 15, 2023).

- Ahonen EQ, Benavides FG. Risk of fatal and non-fatal occupational injury in foreign workers in Spain. J Epidemiol Community Health 2006;60:424–6. [CrossRef]

- Son KS, Yang HS, Guedes Soares C. Accidents of foreign workers at construction sites in Korea. J Asian Archit Build Eng 2013;12:197–203. [CrossRef]

- Biering K, Lander F, Rasmussen K. Work injuries among migrant workers in Denmark. Occup Environ Med 2017;74:235–42. [CrossRef]

- Al-Bayati AJ, Abudayyeh O, Albert A. Managing active cultural differences in U.S. construction workplaces: Perspectives from non-Hispanic workers. J Safety Res 2018;66:1–8. [CrossRef]

- Cheng CW, Wu TC. An investigation and analysis of major accidents involving foreign workers in Taiwan’s manufacture and construction industries. Saf Sci 2013;57:223–35. [CrossRef]

- Kim JM, Son K, Yum SG, Ahn S. Analyzing the risk of safety accidents: The relative risks of migrant workers in construction industry. Sustain 2020;12. [CrossRef]

- Schwatka N, V. , Butler LM, Rosecrance JR. An aging workforce and injury in the construction industry. Epidemiol Rev 2012;34:156–67. [CrossRef]

- Barss P, Addley K, Grivna M, Stanculescu C, Abu-Zidan F. Occupational injury in the United Arab Emirates: Epidemiology and prevention. Occup Med (Chic Ill) 2009;59:493–8. [CrossRef]

- Lette A, Ambelu A, Getahun T, Mekonen S. A survey of work-related injuries among building construction workers in southwestern Ethiopia. Int J Ind Ergon 2018;68:57–64. [CrossRef]

- Tuma MA, Acerra JR, El-Menyar A, Al-Thani H, Al-Hassani A, Recicar JF, et al. Epidemiology of workplace-related fall from height and cost of trauma care in Qatar. Int J Crit Illn Inj Sci 2013;3:3. [CrossRef]

- Giraudo M, Bena A, Costa G. Migrant workers in Italy: an analysis of injury risk taking into account occupational characteristics and job tenure. BMC Public Health 2017;17. [CrossRef]

- Arndt V, Rothenbacher D, Daniel U, Zschenderlein B, Schuberth S, Brenner H. All-cause and cause specific mortality in a cohort of 20 000 construction workers; results from a 10 year follow up. Occup Environ Med 2004;61:419–25. [CrossRef]

- Kreshpaj B, Bodin T, Wegman DH, Matilla-Santander N, Burstrom B, Kjellberg K, et al. Under-reporting of non-fatal occupational injuries among precarious and non-precarious workers in Sweden. Occup Environ Med 2022;79:3–9. [CrossRef]

- Niu, S. & International Labour Organization. List of Occupational Diseases (revised 2010) [Report]. In Occupational Safety and Health Series 2010: Vol. No. 74. International Labour Office.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).