1. Introduction

In Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), there is an on-going discourse about the contribution of urban farming to food and nutrition security (FNS), environmental conservation, and making livelihoods more resilient. While Mkwambisi et al. (2011) as well as Sangwan and Tasciotti (2023) argue in favor of urban farming, Davis et al. (2021) claim that the positive impact may be overstated. One important consensus from these studies is that current urban farming practices face major challenges, namely low profitability, lack of sustainability prospects in the presence of climate change as well as land tenure insecurity. Furthermore, food and nutrition insecurity and livelihood vulnerability are aggravated given SSA’s high rate of urbanization, its growing middle class, and thus the rising urban food demand, which is linked to higher food prices.

Nigeria with a Global Hunger Index score of 28.3 (putting it at 109th out of 125 countries) in 2023 is not only experiencing a serious level of food and nutrition insecurity but has one of the highest urbanization rates in SSA with 5.8% per annum (Aliyu and Amadu 2017, World Population Review 2023, GHIndex 2023). Lagos State, in South West Nigeria, with its over 20 million inhabitants is representative of an African city region in need of a sustainable and productive urban agri-food system to feed its rising population (Oteri and Ayeni 2016). As in other parts of SSA, urban farming in Nigeria suffers from low productivity (Olumba et al. 2021). Reasons for low productivity are, among others, lack of agri-food innovations suitable for an urban context, credit market failure, scarcity of land suitable for urban farming, land tenure insecurity, and limited public sector support (Akinlade et al. 2013, Lawal and Aliu 2012). Identification of challenges, opportunities, and prospects of urban farm practitioners and local civil servants is very important for the conceptualization of policies and interventions aimed at city-region food systems that enhance FNS, livelihood resilience, and environmental sustainability.

This study hypothesizes that a participatory engagement of stakeholders at the grassroots level can drive appropriate and inclusive policies and interventions through new insights into the complex urban agri-food system. Addressing the diverse issues and concerns will also go a long way in contributing to several sustainable development goals (SDGs: SDG 2 - Zero Hunger, 3 - Good Health and Wellbeing, 8 - Decent Work and Economic Growth, 10 - Reduced Inequality, and 11 - Sustainable Cities and Communities).

Thus, this study explores the effectiveness of participatory research specifically focusing on stakeholder dialogue around urban farming and innovation. This participatory research discusses the use of circular innovative technical solutions in urban farming and seeks to identify challenges and opportunities among stakeholders. Some of the prospects and circular urban farming approaches under consideration include aquaponics, hydroponics, recirculating aquaculture systems (RAS), drip irrigation, sack farming, animal husbandry, and waste upcycling. An important aspect of this participatory research was ensuring the voices of participating urban farm practitioners and local civil servants to achieve a fair, equitable, and unbiased outcome.

The study deployed focus group discussion (FGDs) as participatory research instrument. A FGD ensures that groups work on a specific subject while taking ownership of the process with key outcomes addressing all issues and concerns and establishing a consensual opinion (Kraaijvanger et al. 2016). The FGD was conducted in Alimosho Local Government Area of Lagos State in August of 2023 with inputs from key stakeholders including civil servants of the agriculture unit from the local city government.

2. Challenges, Opportunities, and Future Prospects of Innovation in Urban Farming

In this section, studies that evaluate and analyze key challenges, opportunities, and prospects associated with urban farming innovation in SSA are discussed.

2.1. Challenges

A substantial number of urban farmers in SSA lack sufficient access to essential resources such as land and water (Battersby, 2013, Davie et al. 2021, Amao 2021, Sakho-Jimbira and Hathie 2020). Thus, resource constraints are a major hindrance i to the adoption of innovative farming technologies designed for extensive production systems. Apart from resource constraint, inadequate infrastructure, including energy storage facilities, can lead to post-harvest losses, limiting the ability of urban farmers to take full advantage of their produce (Amao 2021, Sakho-Jimbira and Hathie 2020). Furthermore, climate variability in SSA resulting in erratic rainfall patterns and prolonged droughts are disrupt farming activities (Bedeke, 2023, Shiferaw et al. 2014, Zougmoré et al. 2018). There are also several (outdated) policy and regulatory hurdles that hinder the adoption of innovation in urban farming (Battersby, 2013, Sakho-Jimbira and Hathie 2020). The incorporation of urban farming in city planning is often subject to restrictions or lack of support from local governments and authorities (Battersby, 2013, Amao 2021, Sakho-Jimbira and Hathie 2020). Prain (2006) as well as Dubbeling, and Merzthal (2006) argue that this is because urban farming innovation is not embedded in public governance and corresponding policy domains. Another challenge to urban farming innovation is limited access to appropriate education and training, especially from public institutions (Engel et al. 2019). Poor and vulnerable urban farming practitioners often lack the necessary knowledge and training to implement innovative technologies (Sakho-Jimbira and Hathie 2020, Benjamin et al. 2023). Credit to urban farming in SSA represents a relatively modest portion of the overall credit portfolio offered by commercial banks and microfinance institutions (Benjamin 2015, Benjamin et al. 2023, Kimengsi et al. 2020). Financial institutions often cite operational and climatic risks as the primary rationale for their reluctance to provide financial services to farming practitioners in general. Additionally, the belief in elevated rates of loan defaults and challenges in effectively recouping overdue payments restrict loan advancement to urban farming (Cabannes 2012, Benjamin 2015)

2.2. Opportunities

The rapid growth of urban areas in SSA and the growing middle class present an opportunity for urban farming to meet the increasing demand for fresh, healthy, and locally grown produce (Amao 2021). However, Sakho-Jimbira and Hathie (2020) argue that only an inclusive urban farming approach, that does not only benefit large processors and agribusinesses, will result in a win-win scenario. For instance, urban farming can reduce reliance on imported food, enhance FNS, and provide income-generating activities within the vicinity of towns and cities. It is projected that by 2030, African urban food markets will be valued at USD500 billion compared to USD150 billion in 2010 (Sakho-Jimbira and Hathie 2020). The deployment of innovation in urban farming can further increase the value of the urban food market cultivation of conventional, traditional, and underutilized crops, contributing to dietary diversity and thus improved FNS (Orsini et al. 2013). The deployment of innovation in urban farming can provide youth and young adults with employment opportunities and stimulate entrepreneurial ventures (Yoon et al. 2021). Innovation in urban farming such as hydroponics and aquaponics is found not only to be attractive to young adults in developing countries but also requires relatively little land, water, and up-front investment (Orsini et al. 2013, Sakho-Jimbira and Hathie 2020, Benjamin et al 2021a). These novel technologies and solutions not only enable more efficient, productive, and sustainable food production in urban areas but also address important issues related to resource utilization, circularity, environmental impact, and FNS (Davies and Garrett, 2018, Biru et al. 2024, Xi et al. 2022).

2.3. Prospects for the Future

Ezeomedo and Egware (2018) found that urban farming is a major income-generating activity among households in Nigeria. Slater (2001) and Smit et al. (2006) argue that urban farming has the potential to engage marginalized groups in developing countries as well as provide access to essential technical, financial, and knowledge resources. Its impact on FNS is even more pronounced as an increase in productivity and thus efficiency due to the adoption of innovations was found to also reduce food deserts in urban areas (Chaminuka et al. 2021, Benjamin et al. 2023). High-quality, locally grown produce from innovative urban farming can potentially find markets beyond the local community and country contributing to economic growth and international trade (Mougeot, 2000). Furthermore, the adoption of innovations such as aquaponics, hydroponics, etc. results in sustainable farming techniques that minimize resource inefficiency and adverse environmental effects (Konig et al. 2018). Benjamin et al. (2021a, 2023) found that urban aquaponics in comparison to conventional aquaculture in Lagos, Nigeria almost reduces effluent discharge to zero. Thus, innovative urban farming methods have the potential to alleviate poverty by providing income and healthy food for marginalized communities, improving health and overall wellbeingand contributing to several of the SDGs (Dubbeling, and Merzthal 2006, Chaminuka et al. 2021). Engaging in innovative urban farming is a way to foster a sense of community and local pride, encouraging collaboration and social engagement among urban residents in the future (McIvor and Hale 2015).

2.4. Focus Group Discussion

This study investigates the perceptions of urban farming innovation challenges, opportunities, and prospects from a practitioner and civil servant lens. Given the exploratory nature of this research, a qualitative participatory research, similar to that of Tregear et al. (1998) and Kraaijvanger et al. (2016) was conducted based on a FGD approach. Krueger (1994: 254) describes FGDs as “carefully planned discussions designed to obtain perceptions on a defined area of interest in a permissive, non-threatening environment”. This research method is unique as it can retrieve a high volume of information in a short time. The collected information is an expression of the cognition of the participants on the subject matter and represents their insights, knowledge, understanding, and experience. This implies that participants in a FGD take ownership of the process of discussion and information generated and attain a certain degree of consensus on the information generated. It also covers group dynamics and processes such as negotiating power, social networks, and power relations (Kraaijvanger et al. 2016). According to Kraaijvanger et al. (2016), the interpretation of FGDs is subjective and requires time due to transcription, revision of recording, and production of infographics. As FGDs are often not conducted at the grassroots or local level because this would require attentive analysis to get insightful outcomes (see Kraaijvanger et al. 2016), this analysis intends to fill the gap. Thus, to get valuable insights, a consensus index approach was adopted. The consensus index is explained in details in subsequent sections.

3. Methodology

3.1. Study Area

This contribution focuses on the West African sub-region with Nigeria, Lagos State and Alimosho Local Government Area as case study. Lagos State has the second highest population in Nigeria (over 20 million inhabitants) with Alimosho Local Government Area having the highest population (over 3 million) in the State (Adedeji-Adenola et al. 2022, Kareem et al. 2022). Alimosho Local Government Secretariat is one of the local governments with an agricultural unit as well as a substantial number of individuals engaged in urban farming whose conjoint views and concerns on innovative urban farming challenges, opportunities, and prospects for the future are not adequately captured. This due to a lack of literature on the subject matter.

3.2. Focus Group Discussion Process

In August 2023, the first FGD workshop was organized, bringing together urban farm practitioners and civil servants. The FGD took place in the main auditorium of Alimosho Local Government Area. The urban farming innovations proposed for discussion ranged from aquaponics, hydroponics, RAS, drip irrigation, sack farming, and animal husbandry to upcycling of waste into humus. These farming innovations were chosen due to their scalability and suitability for the urban context, where not only land and water are rather scarce but also other constraints apply.

The selection of urban farmers was meticulously executed, relying on data collected by a non-governmental organization (NGO), Aglobe Development Center. Aglobe Development Center is testing prototypes in the area of aquaponics, RAS, hydroponics, and insect and snail farming and, thus, attracting visitations by regional urban farmers. During these visitations, the approached urban farmers had expressed a keen interest and willingness to engage in a dialogue process and skill acquisition. Prior to the FGD, these urban farmers were directly invited and politely asked to confirm their participation. Local government civil servants were directly engaged through the office of the chairperson of Alimosho Local Government Area. This process ensured that only the voices of urban farmers and civil servants were considered, maintaining the integrity of the participatory research. A substantial number (i.e. 26 of 27) of the urban farmers that confirmed their attendance, attended the FGD. Therefore, the farmer participants were divided into two groups: group 1 and 2. Two out of the three invited local civil servants were also present and joined group 1, totaling 13 participants (see

Table 1). Group 2 was made up exclusively of urban farm practitioners with 15 participants. Given the limited number of civil servants that participated in the FGD, the focus of this study is on group 1. Furthermore, Van Eeuwijk and Angehrn (2017) argue that a typical focus group consists of 6-12 individuals who have some level of expertise on the subject matter.

During the FGD, interaction took place between urban farming practitioners and civil servants with three researchers being involved as moderators and facilitators. These senior and junior researchers, apart from observing and recording the discussion, intervened only when there was a need for clarification on the interview guide allowing urban farmers and civil servants to take control and ownership of the discussion. The moderators and facilitators informed the groups about the overall context and objectives of the FGD workhop. The FGD interview guide was divided into three broad topics, with each topic having three to five questions, and presented to the stakeholders for discussion (see

Appendix A). These questions form the basis of the analysis. They also correspond to the discussed innovations, challenges, opportunities, and prospects of urban farming. Each of these questions was deliberated during specific sessions with tea and lunch breaks in-between. Since the questions were discussed chronologically and instantly recorded on a whitepaper board, the participants too had a good overview. While certain non-related urban farming issues and concerns were also brought up during the FGD, the research topics remained in the focus throughout. Furthermore, participants stayed committed to the FGD objective, which indicates the relevance of the study.

The response of all the groups was protocolled on paper and audio-recorded for the development of the mind map. The aforementioned researchers were responsible for writing the outcomes of each discussion outcome on the white paper board and confirming its accuracy with the discussants. This support helps to resolve the issue of illiteracy among participants. A substantial number of participants in the FGD were quite proactive and the discussions were constructive, concise, and cordial.

3.3. Mind Mapping of FGD Outcomes

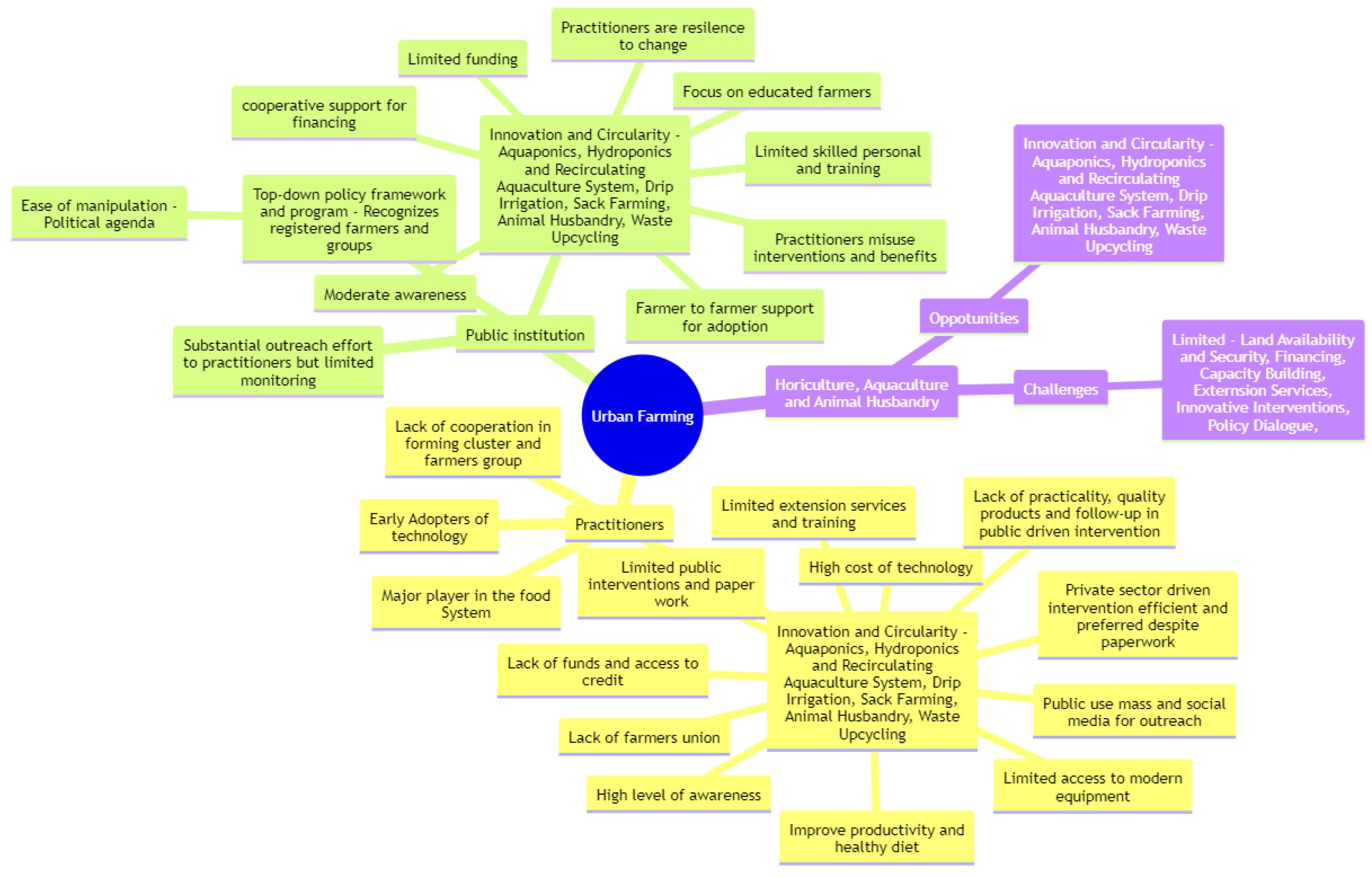

The FGD process and procedure provide a good basis for developing a qualitative visual diagram – a mind map of the issues and concerns as well as quantitative outcome (Kraaijvanger et al 2016). On the one hand, this approach simplifies the illustration of the challenges, opportunities, and prospects associated with urban farming innovation from a practitioner and civil servant perspective. On the other hand, it provides a baseline for more complex and comprehensive future research. The mind map is depicted in

Figure 1. The complexity and extent of the mind map implies that a concise overview of challenges, opportunities, and prospects associated with urban farming innovation is cumbersome without further analysis. Therefore a simplified consensus index is estimated and explained in details in the section 4. However, mind maps provide some relevant initial insights.

The progression of urban farming in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), as viewed through the lenses of both the private and public sectors, necessitates a shift towards more innovative and sustainable production methods. Embracing technologies like aquaponics, hydroponics, RAS, drip irrigation, sack farming, and snail farming is widely recognized as essential for fostering innovation and circularity in food production systems. The mind-maps (

Figure 1), derived from FGDs, illustrates these technologies as promising avenues or opportunities for future urban food systems. However, challenges such as limited land and financial resources, outdated extension services, and a lack of dialogue between policymakers and practitioners pose obstacles to the transformation of urban farming for FNS and sustainable livelihoods in SSA. The local public agricultural unit in Lagos, Nigeria, predominantly adopts a top-down approach in formulating urban farming policies and engaging with organized farmer unions to instigate transformative changes. Yet, there exists only a moderate comprehension within the public sector regarding the technologies pivotal for driving the desired transformation in urban farming, despite considerable outreach efforts. Furthermore, the public sector allocates limited funding to innovative urban farming interventions or programs, and political affiliations often influence the selection of beneficiaries. Consequently, interventions tend to target a subset of the urban farming population, typically educated and high-value individuals, while a significant portion of the population are precieved as resistant to change and fails to leverage the full potential of these initiatives or programs.

Urban farming practitioners in Lagos, Nigeria, see themselves not just as participants in the urban food system, but as pivotal contributors. They view themselves as pioneers, embracing innovative techniques such as aquaponics, hydroponics, RAS, drip irrigation, sack farming, and snail farming, despite the initial financial hurdles. Urban farming practitioners believe that adopting these modern methods can lead to increased productivity. However, they also acknowledge the persistent challenges hindering the attainment of food and nutrition security (FNS). Challenges such as limited access to credit, inadequate supply of quality inputs, deficient extension services, and a lack of supportive programs, particularly from local public agricultural authorities, pose significant barriers. In response to these challenges, urban farming practitioners express a growing preference for interventions and initiatives led by the private sector. They have greater confidence in these private sector initiatives, pointing to the presence of robust monitoring and evaluation mechanisms and the involvement of genuine agents of change. This trust in private sector involvement stems from their perception that private initiatives are more responsive to their needs and are better equipped to address the complexities of urban agriculture in Lagos.

4. Results

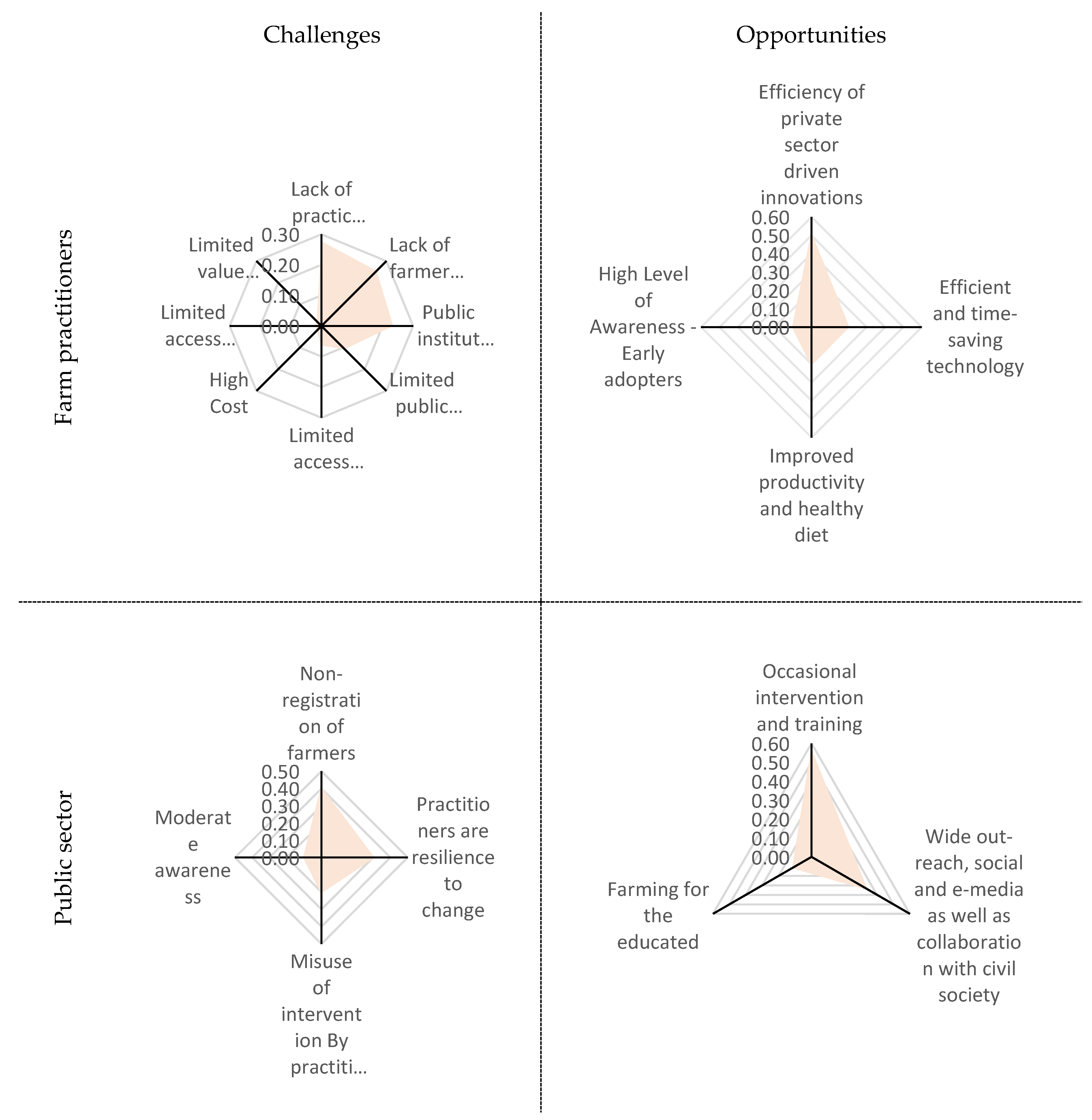

4.1. Challenges and Opportunities of Urban Farming Innovations – Insights from the Consensus Index and Radial Diagrams

Based on the identified issues and concerns, a simple consensus index was developed similar to the approach of Kraaijvanger et al. (2016). This consensus index is based on the frequency of a particular issue and concern raised by discussants divided by the total number of issues and concerns raised during the FGD-workshop. The consensus index (

) can be mathematically written as:

where

is the total frequency of a particular issue and concern

and

is the total number of issues and concerns raised during the FGD. This gives a clearer and concise interpretation of the FGD process.

The

from the FGD transcription are depicted in

Table 2. The individual

provides a good starting point in understanding the major issues and concerns surrounding urban farming innovations from diverse perspectives. Based on the

calculation, the most important issues and concerns raised by practitioners and civil servants are presented in

Table 2 below. A total of 19 issues and concerns related to challenges, opportunities, and prospects of innovation in urban farming were estimated after undertaking an audio-to-word transcription to get adequate data.

The assessment of these 19 issues and concerns reveals varying degrees of severity, from both practitioners and public servants prespective, as depicted in

Figure 2. Urban farmers emphasize several key challenges impeding the advancement of innovative urban farming. They underscore the deficiency in practicality, the inadequacy of quality products, and the lack of follow-up from public interventions as notable hurdles. Moreover, they identify a dearth of cooperation and collaboration among themselves as a significant barrier to progress within innovative urban farming. Lastly, urban farmers lament the neglect of their needs and concerns by the public sector, recognizing it as yet another formidable obstacle to the transformative potential of urban farming. Urban farmers are increasingly turning to innovative farming practices as a gateway to unlock the benefits of more streamlined and effective private sector interventions. They perceive this shift as a pivotal opportunity to not only boost food productivity but also to facilitate greater access to nutritious diets. Additionally, they see innovative farming as a pathway to harness time-saving technologies that can optimize food system processes and enhance overall efficiency.

From the perspective of the public sector, urban farmers’ lack of cooperation and resistance to change represent substantial obstacles to the advancement of innovative farming practices. The public sector perceives cooperation among urban farmers as essential for collective progress and the successful implementation of new methods. Without a collaborative approach, the public sector believes that the potential benefits of innovative farming practices may be hindered or delayed. Moreover, the public sector identifies urban farmers’ resistance to change as a significant challenge. This resistance can manifest in various forms, such as reluctance to adopt new techniques or technologies, skepticism towards unfamiliar approaches, or adherence to traditional farming methods. Such resistance impedes the integration of innovative practices into urban farming systems and slows down the pace of sustainable development. Furthermore, the public sector highlights the insufficient utilization of programs and interventions by urban farmers as another major obstacle. Despite the modest public programs and interventions aimed at promoting innovative farming practices, urban farmers may not fully engage with these programs due to various reasons such as lack of awareness, access barriers, or perceived ineffectiveness. This underutilization of programs and interventions limits the potential impact of public-sector efforts to foster innovation and sustainability in urban agriculture. From the perspective of the public sector, there are two significant opportunities associated with innovative farming practices. These opportunities primarily stem from the modest interventions and training initiatives that the public sector provides. These interventions may include various support mechanisms such as capacity building, technical assistance, and financial incentives aimed at promoting the adoption of innovative farming methods among urban farmers. Collaboration with the private sector is another opportunity for advancing innovative farming practices. By partnering with private enterprises, governments can leverage resources, expertise, and technology to enhance the effectiveness and scalability of initiatives. Such collaborations can facilitate knowledge exchange, investment opportunities, and the development of innovative solutions to address the challenges facing urban agriculture.

4.2. Challenges and Opportunities of Urban Farming Innovations – Practitioners’ Perspective

Practitioners identified public institutions and their corresponding interventions as a significant challenge in the context of urban farming innovations. Practitioners perceive the public sector’s approach to implement innovative solutions to be obsolete and slow, which hinders progress in urban farming (

Table 3). Practitioners also acknowledge their shortcomings, highlighting issues related to a lack of unity and cooperation among themselves. They realize that this behavior can impede the success of public initiatives in promoting urban farming. Practitioners also state that they perceive the private rather than the public sector as a genuine driver of innovation in urban farming. They have more trust in the private sector organization and their ability to provide tailored, high-quality solutions. They believe public institutions do not have the capacity to accelerate innovation in urban farming in the short or long-term.

Practitioners believe that innovation in urban farming can significantly boost productivity, leading to increased yields and a more efficient use of resources. They also recognize that innovation in urban farming can expand the variety of crops and foods produced, resulting in healthier and more diverse diets for urban populations. Practitioners see innovation in urban farming as a means of optimizing scarce resource use, potentially reducing waste, improving environmental sustainability as well as saving time and freeing up labor to other activities, making urban farming more practical and manageable.

4.3. Challenges and Opportunities of Urban Farming Innovations – Public Servants’ Perspectives

The public servants involved in agriculture predominantly view urban farmers’ attitudes as a factor that hinders the widespread adoption of innovations in urban farming (

Table 3). They express concerns regarding the behavior and resistance of urban farming practitioners to change. Furthermore, public servants perceive the lack of data on urban farmers and the refusal to register as farming entity at the agricultural unit of the local government level as a major challenge. They claim that the lack of data makes it difficult for the public sector to reach out to urban farming practitioners when innovation interventions and programs become available from the state or federal institutions. Local public servants also express doubts about the sincerity of practitioners participating in urban farming innovation programs. Thus, they are uncertain whether they truly reach practitioners engaged in urban farming or individuals claiming to be engaged in urban farming but just seeking unearned subsidies.

The local public sector representatives consider their knowledge and subsequently their interventions and training on innovative urban farming as somewhat in its infancy. Therefore, they perceive their collaboration with the private agri-food system as a way of expanding their knowledge base on innovative urban farming. The public servants perceive the few initiatives they undertake as a positive driver of urban farming innovation as they see themselves as an outreach channel for spreading innovative urban farming technologies and techniques among practitioners. However, they perceive urban farming interventions and programs to be more beneficial to educated urban farmers. This reflects their belief that educated individuals can bring valuable expertise to innovation in urban farming.

5. Discussion of Results

Innovations in urban farming such as aquaponics, hydroponics, RAS, sack farming, drip irrigation, animal husbandry, and waste upcycling can play a major role in urban food systems in the long term as the rate of urbanization continues to soar in SSA. While urban farming practitioners will be the drivers of change through the adoption of these innovations, the public sector policies and extension services will be catalytic to such change (Davis et al. 2021). Unfortunately, synergies have not been witnessed between practitioners and local public agriculture institutions across cities in SSA (Gore 2018; Davis et al. 2021). There seems to be a lack of communication, understanding, and to a large extent a lack of trust among relevant urban farming stakeholders when it comes to deploying innovations. To bridge the dialogue gap between urban farming practitioners and public servants on agri-food system transformation through innovation, a FGD was conducted in Alimosho Local Government Areas, Lagos, Nigeria by the NGO Aglobe Development Center. Gore (2018) argues that such NGOs and stakeholder collaboration based on common values supplement government efforts in achieving the desired goal, in this case innovative urban farming systems.

The FGD workshop was attended by 26 urban farmers and two civil servants from the agricultural unit of the local government. Not surprisingly, the outcome of the FGD points to divergence in the understanding of the challenges, opportunities, and prospects of innovations in urban farming. From the mind-maps and CI estimations, practitioners appear to have a deep understanding of the opportunities associated with innovative urban farming technologies such as higher productivity and efficiency in relation to inputs such as land, water, or labor. This aligns with the findings of Dubbeling, and Merzthal (2006), namely that innovation in urban farming is a rather bottom-up approach and as such should adopt a participatory dialogue involving an array of stakeholders. The identified lack of trust in the public sector interventions by practitioners is one of the major challenges of innovation in urban farming according to the mind-maps and CI estimations. Quon (1999) and Gore (2018) found that in SSA, representatives of the public sector often do not actively participate in the interaction between urban farmers and other relevant stakeholders, which could explain the distrust. Prain (2006) argues that urban farming can only be successful in developing countries if made an integral part of urban development strategy by governments. McIvor and Hale (2015) argue that the success of urban farming projects requires a team effort from several actors. The aforementioned lack of trust may have created a void in the pursue of innovative urban farming, which is increasingly being filled by NGOs, private sector organizations, and advocacy groups across SSA. Urban farming practitioners in Lagos perceive that NGOs and private sector organizations lead innovations in urban farming as pragmatic, valuable, and authentic. According to Battersby (2013) and Smit et al. (2006), this may be due to the fact that NGOs and private sector organizations often conduct urban agriculture research and propagating their results in roadshows, adopting an advocacy approach that is apolitical and ahistorical. This makes them the preferred choice of reference for urban farming practitioners in SSA. Urban farming practitioners also see their lack of cooperation and coordination as a hindrance to the adoption of innovative urban farming solutions. This view is shared by the local public servants. The public sector representatives believe that none of their actions obstruct the adoption of innovative urban farming rather seeing themselves as agents of change. They believe that their contribution, although marginal, cannot be downplayed. For instance, they emphasized that their programs and interventions ensure that educated and privileged urban farming practitioners are also represented. One reason for this perspective may be due to the observation by Amao (2020) that highly educated urban farming practitioners produce more output and are early adopters compared to less educated and vulnerable practitioners. Alimosho Local Government Areas civil servants believe that their awareness campaigns on innovation in urban farming reached a substantial number of urban farmers. Benjamin et al. (2021) argue that the spread of information on food system innovations through public extension services is rather poor compared to private extension services. This was also reaffirmed during the FGD by urban farming practitioners that public extension services were not only lacking but often obsolete.

6. Conclusion

As the spade of urbanization continues to soar in SSA, there is a need to focus on innovation in urban farming for FNS, empowerment as well as environmental sustainability. Innovation in urban farming in SSA is multifaceted in challenges, opportunities, and prospects. Addressing some of the challenges while leveraging on the opportunities can help create a sustainable and resilient urban food system in the short- and long-term only if relevant stakeholders have a participatory bottom-up dialogue. However, such participatory bottom-up dialogue is often lacking due to distrust among relevant stakeholders.

A FGD was conducted in Lagos, Nigeria, bringing together urban farming practitioners and public servants engaged in agriculture. The results suggest that distrust does exist between urban farming practitioners and public servants with the former having a preference for private sector interventions and programs. The local public sector seems to favor educated and exposed urban farmers when it comes to interventions and programs indicating a selection bias.

To drive innovation in urban farming in African cities, such as Lagos, Nigeria, there is a need to align the objectives of urban farming practitioners and relevant local civil servants. For instance, urban farming clusters can be established with a central database that is accessible to the public sector. This ensures that public interventions and programs reach the targeted audience at the appropriate time as well as ease follow-up measures.

One of the limitations of this study is the lack of state or federal representation and perspective on innovation in urban farming considering that they often orchestrate programs and interventions that are then implemented at the local government level. Future research should endeavor to incorporate the perspectives of the state or federal government on innovation in urban farming as well as conduct a critical assessment of food policy formulation in cities. Furthermore, there is a need for impact assessment of participating in international collaborative efforts such as Milan Urban Food Policy Pact (MUFPP), which promotes best practices in sustainable urban farming policy for African cities e.g. Lagos that are not yet signatories.

Author Contributions

Methodology & writing-review: E.O.B. conceptualization, data analysis, writing-original draft: E.O.B., A.A. and G.R.B. validation & supervision: G.R.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This paper is supported by the European Union under Horizon Europe, grant agreement No 101083790, project "Integrated and Circular Technoloigies for Sustainable city region FOOD Systems in Africa (INCiTiS-FOOD). Views and opinions expressed are however those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union. Neither the European Union nor the granting authoriy can be held responsible for them.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Attached.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the management team (

www.aglobedc.org, accessed on 23 May 2024) and staff of Aglobe Development Center, Lagos, Nigeria, especially Sulaimon Babalola, Victoria Aghaji and Hikimot Babalola.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

I. FGD questions

References

- Adedeji-Adenola, H., Adesina, A., Obon, M., Onedo, T., Okafor, G. U., Longe, M., & Oyawole, M. (2022). Knowledge, perception and practice of pharmaceutical waste disposal among the public in Lagos State, Nigeria. The Pan African Medical Journal, 42. [CrossRef]

- Akinlade, R. J., Balogun, O. L., & Obisesan, A. A. (2013). Commercialization of urban farming: the case of vegetable farmers in southwest Nigeria (No. 309-2016-5243).

- Amao, I. (2020). Urban Horticulture in Sub-Saharan Africa. Urban Horticulture—Necessity of the Future.

- Battersby, J. (2013). Hungry cities: a critical review of urban food security research in sub‐Saharan African cities. Geography Compass, 7(7), 452-463. [CrossRef]

- Bedeke, S. B. (2023). Climate change vulnerability and adaptation of crop producers in sub-Saharan Africa: A review on concepts, approaches and methods. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 25(2), 1017-1051. [CrossRef]

- Benjamin, E. O. (2015). Financial institutions and trends in sustainable agriculture: Synergy in rural sub-Saharan Africa (Doctoral dissertation, Universitätsbibliothek Wuppertal).

- Benjamin, E. O., Buchenrieder, G. R., & Sauer, J. (2021a). Economics of small-scale aquaponics system in West Africa: A SANFU case study. Aquaculture economics & management, 25(1), 53-69. [CrossRef]

- Benjamin, E. O., Ola, O., Lang, H., & Buchenrieder, G. (2021). Public-private cooperation and agricultural development in Sub-Saharan Africa: a review of Nigerian growth enhancement scheme and e-voucher program. Food Security, 13, 129-140. [CrossRef]

- Benjamin, E. O, Tzemi, D and Fialho, D. E. (2023). Prospects of Sustainable Urban Framing for Food Security and Sustainable Development in Sub-Saharan Africa. In Chizoba Chinweze (ed.) Desertification, Land Degradation and Drought Resilience , Cuvillier Verlag Goettingen.

- Cabannes, Y. (2012). Financing urban agriculture. Environment and Urbanization, 24(2), 665-683.

- Chaminuka, N., Dube, E., Kabonga, I., & Mhembwe, S. (2021). Enhancing Urban Farming for Sustainable Development Through Sustainable Development Goals. In Sustainable Development Goals for Society Vol. 2: Food security, energy, climate action and biodiversity (pp. 63-77). Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Davies, F. T., & Garrett, B. (2018). Technology for sustainable urban food ecosystems in the developing world: Strengthening the nexus of food–water–energy–nutrition. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems, 84.

- Davies, J., Hannah, C., Guido, Z., Zimmer, A., McCann, L., Battersby, J., & Evans, T. (2021). Barriers to urban agriculture in Sub-Saharan Africa. Food Policy, 103, 101999. [CrossRef]

- Dubbeling, M., & Merzthal, G. (2006). Sustaining urban agriculture requires the involvement of multiple stakeholders. Cities farming for the future: Urban agriculture for green and productive cities, RUAF Foundation, IIR, IDRC, Ottawa, Canada, 19-40.

- Engel, E., Fiege, K., & Kühn, A. (2019). Farming in cities: Potentials and challenges of urban agriculture in Maputo and Cape Town. Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin.

- Ezeomedo, I., & Egware, R. (2018). Eradication of extreme poverty and hunger using urban agriculture as a tool for sustainable livelihood. coou African Journal of Environmental Research, 1(1), 78-97.

- GHIndex (2023). 2023 Global Hunger Index: The Power of Youth in Shaping Food Systems.

- Gore, C. D. (2018). How African cities lead: Urban policy innovation and agriculture in Kampala and Nairobi. World development, 108, 169-180. [CrossRef]

- König, B., Janker, J., Reinhardt, T., Villarroel, M., & Junge, R. (2018). Analysis of aquaponics as an emerging technological innovation system. Journal of cleaner production, 180, 232-243. [CrossRef]

- Kareem, I., Adekunle, M., Adedokun, M., & Ibegbulem, C. (2022). Marketing analysis of fluted pumpkin (telfairia occidentalis hook f.) in Alimosho Local Government Area, Lagos state, nigeria. Journal of Agricultural Science and Environment, 22(1), 85-95.

- Kimengsi, J.N., Balgah, R.A., Buchenrieder, G., Silberberger, M., and H.P. Batosor. 2020. An empirical analysis of credit-financed agribusiness investments and income poverty dynamics of rural women in Cameroon. Community Development Journal 51 (1): 72-89. [CrossRef]

- Krueger, R. A. (1994) Focus Groups. A Practical Guide for Applied Research. 2nd Edition. Sage Publications, London.

- Lawal, M. O., & Aliu, I. R. (2012). Operational pattern and contribution of urban farming in an emerging megacity: evidence from Lagos, Nigeria. Bulletin of Geography. Socio-economic Series, (17), 87-97. [CrossRef]

- McIvor, D. W., & Hale, J. (2015). Urban agriculture and the prospects for deep democracy. Agriculture and Human Values, 32, 727-741. [CrossRef]

- Mkwambisi, D. D., Fraser, E. D., & Dougill, A. J. (2011). Urban agriculture and poverty reduction: Evaluating how food production in cities contributes to food security, employment and income in Malawi. Journal of International Development, 23(2), 181-203. [CrossRef]

- Mougeot, L. J. (2000). Urban agriculture: Definition, presence, potentials and risks, and policy challenges. Cities feeding people series; rept. 31.

- Olumba, C. C., Olumba, C. N., & Alimba, J. O. (2021). Constraints to urban agriculture in southeast Nigeria. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 8(1), 1-11.

- Oteri, A. U., & Ayeni, R. A. (2016). The Lagos Megacity. Water, megacities, and global change, 1-36.

- Orsini, F., Kahane, R., Nono-Womdim, R., & Gianquinto, G. (2013). Urban agriculture in the developing world: a review. Agronomy for sustainable development, 33, 695-720. [CrossRef]

- Poulsen, M. N., McNab, P. R., Clayton, M. L., & Neff, R. A. (2015). A systematic review of urban agriculture and food security impacts in low-income countries. Food Policy, 55, 131-146. [CrossRef]

- Prain, G. (2006). Participatory technology development for sustainable intensification of urban agriculture. Cities farming for the future: Urban agriculture for green and productive cities, RUAF Foundation, IIRR, IDRC, Ottawa, Canada, 275-313.

- Quon, S. (1999). Planning for urban agriculture: A review of tools and strategies for urban planners. Cities feeding people series; rept. 28.

- Sangwan, N., & Tasciotti, L. (2023). Losing the plot: the impact of urban agriculture on household food expenditure and dietary diversity in sub-Saharan African countries. Agriculture, 13(2), 284. [CrossRef]

- Sakho-Jimbira, S., & Hathie, I. (2020). The future of agriculture in Sub-Saharan Africa. Policy Brief, 2(3), 18.

- Shiferaw, B., Tesfaye, K., Kassie, M., Abate, T., Prasanna, B. M., & Menkir, A. (2014). Managing vulnerability to drought and enhancing livelihood resilience in sub-Saharan Africa: Technological, institutional and policy options. Weather and climate extremes, 3, 67-79. [CrossRef]

- Slater, R. J. (2001). Urban agriculture, gender and empowerment: an alternative view. Development Southern Africa, 18(5), 635-650. [CrossRef]

- Smit, J., Bailkey, M., & Van Veenhuizen, R. (2006). Urban agriculture and the building of communities. Van Veenhuizen, R. Cities farming for the future, urban agriculture for green and productive cities. Leusden: RUAF Foundation, 146-171.

- Van Eeuwijk, P., & Angehrn, Z. (2017). How to… Conduct a Focus Group Discussion (FGD). Methodological Manual.

- Biru, W. Buchenrieder, G, and Benjamin.O.E (2024). A systematic Literature Review on the Sustainability of Climate Smart and Water Saving Frontier Agricultural Technologies in the Mediterranean Region. Conference paper at The Economics of the Food System: Transition toward Sustainability, 29 February – 1 March, Heilbronn, Germany.

- Xi, L., Zhang, M., Zhang, L., Lew, T. T., & Lam, Y. M. (2022). Novel materials for urban farming. Advanced Materials, 34(25), 2105009.

- Yoon, B. K., Tae, H., Jackman, J. A., Guha, S., Kagan, C. R., Margenot, A. J., ... & Cho, N. J. (2021). Entrepreneurial talent building for 21st century agricultural innovation. [CrossRef]

- Zougmoré, R. B., Partey, S. T., Ouédraogo, M., Torquebiau, E., & Campbell, B. M. (2018). Facing climate variability in sub-Saharan Africa: analysis of climate-smart agriculture opportunities to manage climate-related risks. Cahiers Agricultures (TSI), 27(3), 1-9. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Public

Perspective

Public

Perspective  Prospects

Prospects  .

.

Public

Perspective

Public

Perspective  Prospects

Prospects  .

.