1. Introduction

A large body of international research has pointed out that the physical environment of the school (such as ventilation, lighting, temperature, lack of sound insulation, suitability of furniture and deterioration of buildings) can increase health risks for students [

1,

2], as well as truancy [

3,

4], and lower academic performance on standardised tests [

3,

4,

5,

6]. However, the relationship between the physical environment and the quality of school climate and student well-being [

7] remains less studied.

In Chile, the demand to improve the physical environment of schools has a long history. Since 2006, public school students have been highlighting the serious problems of the physical environment. This demand was repeated in the student mobilisations of 2011, 2019 and 2022. All these protests have thrusted into the spotlight the unfavourable perception of the physical environment of schools and criticised the lack of interest in understanding how these conditions affect other school phenomena [

8].

More recently, Chile has witnessed an increase in the incidence of symptoms related to mental health [

9,

10], along with an increase in complaints related to the quality of the school environment. These complaints have showed the deteriorating physical conditions of public schools. These include leaking roofs, rooms at risk of collapse, problems with sanitary facilities, pest infestation, among others [

11,

12].

Along these lines, the aim of this article is to analyze the mediating effect of perceptions of the physical environment of the classroom on the perception of school climate and subjective well-being of students in subsidized schools in Chile. This topic represents a neglected research topic [

7], even more in Latin America where large inequalities between social groups are evident [

13] along with high educational segregation. The latter is detrimental to the most vulnerable students who, in addition, access education in worse conditions [

14].

Further progress along these lines could orient public policies in evaluating the perception of the country’s educational institutional environment and considering students' and teachers' perceptions of school climate and well-being. The development of school wellbeing requires not only relational, pedagogical, normative and institutional support, but also the assessment that different actors have of the conditions of the school's physical environment. This can contribute to making the lives of the most vulnerable students more dignified.

This study investigated the following question: What is the mediating effect of the perception of the physical environment of the classroom on the perception of school climate and subjective well-being of students in state-funded schools in Chile?

2. Background and Literature Review

The literature refers to the physical classroom environment as the physical and material conditions of a school and/or classroom considering "the built environments that are intended to be places of learning; it also includes buildings, interaction spaces, their spatial structure, furniture, fixtures, fittings, accessories and equipment" [

15] (p. 13). Based on a literature review, Barret et al. [

16] consider three aspects in defining the physical environment: a) environmental elements that affect comfort, including climatic conditions, light and the presence of natural elements (e.g. trees or green areas); b) functional elements that support the learning and teaching activities of students and teachers, including flexibility and manipulation of furniture by students; and c) aesthetic elements, which include the complexity of the physical learning environment and the use of colors. Thus, there is evidence of a relationship between the physical learning environments and the relationships within them.

School climate is defined as the set of norms, shared beliefs, values and educational practices that influence the interaction between different educational actors producing a sense of belonging [

17]. While there are many definitions of school climate, there is agreement in the literature to measure school climate by considering the sense of safety, school belongingness, perceived support from adults in school and the participations of students in the school decisions [

18,

19].

Research has linked poor perceptions of the physical environment of the classroom and school to poor school climate [

20]. Voight and Nation's literature review reports that caring for the physical environment of the classroom is related to improved school climate. Plank et al. [

21] demonstrated that deteriorated infrastructure and physical clutter in classrooms increase feelings of fear and encourage threatening or violent interactions among students. The same study identified that cleanliness, a comfortable temperature and the absence of deterioration of windows, doors or desks were associated with higher perceptions of safety among students. Maxwell [

22] found a relationship between the poor condition of school buildings and poor school performance, reporting that these are also mediated by classroom climate.

The study by Finell et al. [

7] in 197 Finnish schools (n = 27,153 students) found that classrooms with ventilation problems show poorer teacher-student relationships and lower student perceptions of school climate. On the other hand, Connolly et al. [

23] reported that, in classrooms with poor acoustics or long periods of sound reverberation, the school climate is perceived as more competitive, conflictual, less relaxed and comfortable. Finally, truancy has been found to be higher in schools with poor ventilation [

4], which may also reflect problems with school climate and well-being [

7].

Subjective well-being is understood as a measure of subjective quality of life [

24]. It consists of a subject's personal perception of happiness in the experience of pleasure versus displeasure [

25]. Diener [

26] and Diener et al. [

27] talk about subjective well-being, defining it as an individual's general evaluation of their life, deriving from four components (two emotional and two cognitive): negative emotions and positive emotions; life satisfaction, and finally satisfaction in specific domains, such as work, family, and friends.

Recent research has documented positive associations between the physical environment of classrooms and schools and subjective well-being [

28,

29]. Environmental factors such as ventilation, aroma, and noise level influence the perception of satisfaction with school among students [

30]. Likewise, the design and functionality of classrooms and schools contribute to the feeling of school safety [

28]. On the other hand, poor lighting, poor acoustics, and unfavorable aesthetics have been observed to negatively affect students, causing discomfort, headaches, and fatigue [

31], [

29,

30,

31,

32,

33]. In addition, small classrooms have been reported to generate perceptions of dissatisfaction and discomfort among students [

34].

2.2. The Deterioration of the Physical Environment of the Chilean Public School: Chronicle of a Death Foretold

In Chile, perceptions about the conditions of the physical environment in schools have been negative for a long time. Since 2006, student movements have expressed their dissatisfaction with the conditions of their schools. This concern has become more acute after the pandemic, due to the prolonged closure of schools. Despite this, no clear policies have yet been established to change this situation.

The infrastructure deficit in Chilean educational establishments is not evenly distributed across the country [

35]. Students who come from families with lower socio-economic levels, with greater educational needs, are those who have been most affected by the quality of the infrastructure of their schools [

36].

One of the central aspects of this unequal distribution is related to the structure of the Chilean education system. The installation of a subsidized state during the civil-military dictatorship, indeed, created an educational market that privatized education and left public schools without funding. This approach results in variable revenues and uncertainty in resource planning [

37] which has a negative impact on the ability to make investments, such as those aimed to improve and/or repair school infrastructure. As a consequence, schools tend to be perceived as a less safe place to study and the education they provide as qualitatively poor [

38]. In these schools, students’ enrolment decreased from 78,3% of the national total in 1980 to 37% in 2016 [

39].

3. Materials and Methods

A secondary analysis was performed on 2018 data from the “Sistema de Monitoreo de la Convivencia Escolar” administered by the Junta Nacional de Auxílio y Becas Escolares (JUNAEB) of the Chilean Ministry of Education. This was the latest measurement available in the country.

3.1. Participants

The schools were part of a public-school mental health program called Habilidades para la Vida (Skills for Life, hereafter SFL), run by the JUNAEB, a division of the Ministry of Education that oversees providing resources and support to disadvantaged students, including school lunches, transportation, and health services. SFL is a program responsible for improving student mental health and is one of the largest school-based mental health programs in the world [

40]. The SFL program focuses on a portion of schools classified as high-risk by the Ministry of Education, based on a school socioeconomical status index, which considers poverty and other sociocultural factors of the students. As of 2016, the SFL program was present in 22 % of the schools in Chile classified in the first and second quartile of high-risk schools [

41].

As mentioned before, in this study the 2016 data of the SFL program was used. The sampling was of a census nature because the questionnaire was answered by all students attending on the day of its application. All cases in which any questions corresponding to the variables analyzed were not validly answered were excluded from the sample, as were all schools whose survey responses did not reach 50% of the total enrollment. The final sample was composed by 19.567 students (48,77% female) between fifth and eighth grade (mean age = 12,53; SD = 1,42, range = 10-16) from 425 municipal (86,17%) and private subsidized (13,83%) schools, all of which receive state subsidies. The sample was intentional because the participants were chosen in a targeted manner from the lowest SES schools in the country which participated in the SFL program.

3.2. Instruments

3.2.1 School Climate. It was implemented an adaptation of Benbenishty and Astor's [

42] School Climate Scale. The scale used consists of 17 four-point Likert response items (from 1 = "Strongly Disagree" to 4 = “Strongly Agree”), and it measures the perception of school climate in terms of satisfaction with school, social support from teachers, fair rules, and participation (e.g. “I feel good in this school” [“Yo me siento bien en esta escuela”], “My relationship with teachers is good and close” [“Mi relación con los profesores es buena y cercana”]). This scale was chosen because it considers participation as the main issue in the school climate (Cronbach’s α = 0.87; MacDonald’s ω=0.87).

3.2.2. Subjective Well-being. It was used an adaptation of the Brief Multidimensional Life Satisfaction Scale for Students validated in Chile by Alfaro and colleagues [43]. This scale consists of 7 items with a 7-point Likert response (from 1 = Poor to 7 = Excellent), and it measures the students' satisfaction with their families, friends, neighborhood, school, personal well-being and life in general. (e.g., "I would describe my satisfaction with my grades as..." [“Yo describiría mi satisfacción con mis notas como...”], "I would describe my satisfaction with my family life as..."/ [Yo describiría mi satisfacción con mi vida familiar como…”]). This scale was chosen because is very frequently adopted in Chile (Cronbach’s α = 0.92; MacDonald’s ω=0.91).3.2.3. Perception of the physical environment of the classroom. The physical environment perception subscale was used, contained in the Classroom Climate Scale constructed and validated by López et al [44]. This subscale is composed of six items ("Mi habitación está limpia y ordenada" ["My room is clean and tidy"]; "En mi habitación hay suficiente luz para trabajar en clase" ["In my room there is enough light to work in class"]; "Podemos escuchar bien al profesor y a los compañeros en cualquier lugar del salón" ["We can hear the teacher and classmates well from anywhere in the room"]; "En su suficiente luz para trabajar en clase" ["In my room there is enough light to work in class"]; "We can hear the teacher and classmates well from anywhere in the room"] ; "Enough space to work in class" ["In my room there is enough space to work in class"]; "We can see the whiteboard well from anywhere in the room" ["We can see the whiteboard well from anywhere in the room"] ; "I like my room" ["I like my room"]). Given the lack of scales focused on the physical environment in Chile, this scale was selected to be used in the present study (Cronbach's α = 0.78; MacDonald ω=0.77).

3.3. Covariates

To control other measures that have an impact on student perception of school climate, we included information from student questionnaires. Self-reported age and gender were included among the control variables, the latter coded as a dichotomous variable, where male students were the reference group (= 0). Additionally, we included the socio-economic level of the student which was measured through an index of student vulnerability condition, called SINAE, from official JUNAEB data. The SINAE index is coded as an ordinal variable between 0 and 3 (0 = Not Vulnerable; 1 = Third Priority; 2 = Second Priority; 3 = First Priority), where higher scores represent lower socio-economic level. Finally, we included a variable representing the ranking of students within their own grade based on students' self-reported academic performance.

3.4. Analysis Plan

The analytical strategy used is based on simple statistical mediation models [

45,

46]. There is a single mediating variable M, two consequent variables (one for the mediating variable M and one for the outcome variable Y) and two antecedent variables (X and M), where the variable X exerts a causal influence on M and Y, and where M exerts a causal influence on Y. Because there are two outcome variables, the estimation is made by means of a system of two linear models.

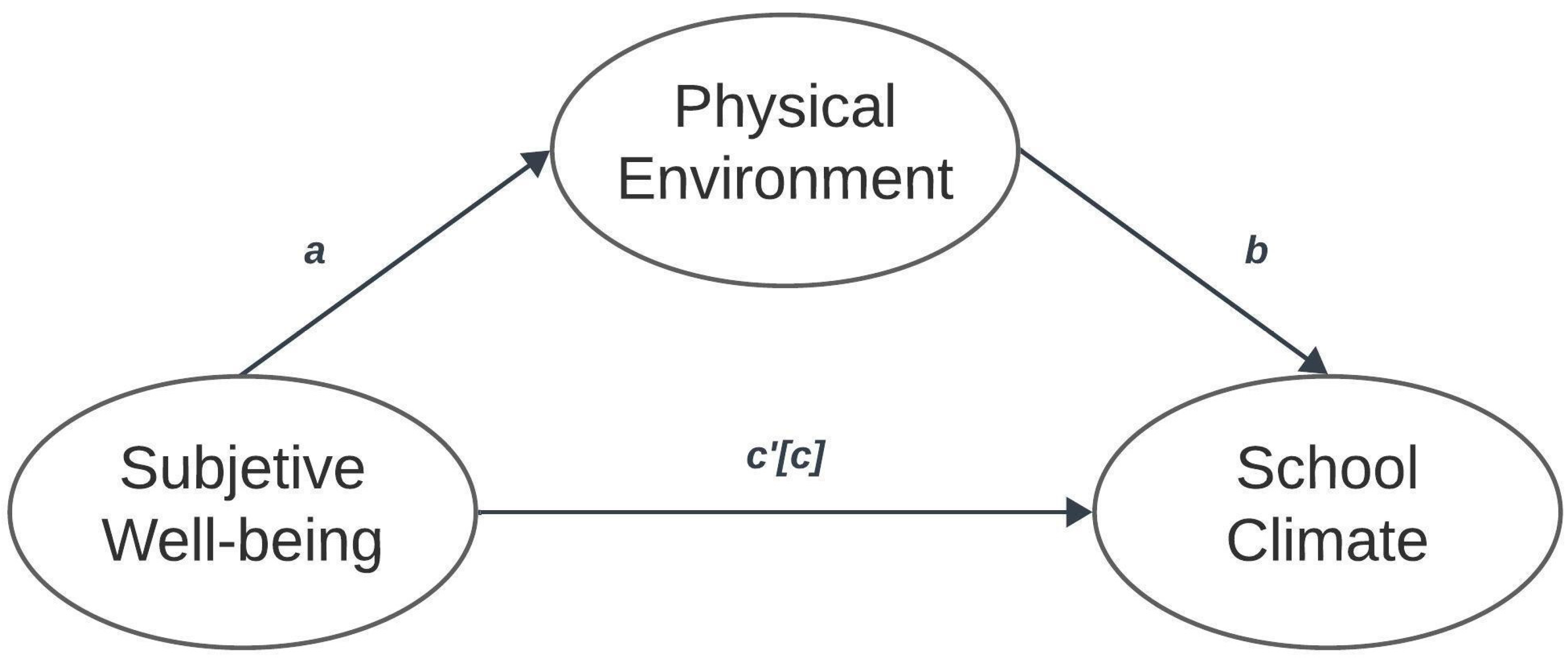

This study proposes the perception of the physical environment of the classroom as a mediator in the relationship between subjective well-being and school climate. The statistical mediation model of this study is shown in

Figure 1, where

a,

b and

c' are the regression coefficients of the antecedent variables on the consequent variables of the model:

a estimates the effect of subjective well-being (X) on perception of physical environment (M);

b estimates the effect of perception of physical environment (M) on school climate (Y) controlling for the effect of subjective well-being. Finally,

c' estimates the direct effect of subjective well-being (X) on school climate (Y) holding constant the perception of physical environment. The indirect effect of subjective well-being on school climate through the mediating variable is the product of the coefficients a × b. Therefore, the total effect, represented by

c in the causal relationship of subjective well-being on school climate, is the sum of the direct and indirect effects. In this model, as can be seen from the diagram, the latent concepts of subjective well-being, school climate, and physical environment (represented as ovals) have been used. In addition, student gender, socio-economic status, academic performance measured as ranking, and student age were used as covariates.

To estimate the aforementioned statistical mediation model, we used the maximum-likelihood method estimation of a structural equation model, with clustered standard errors by schools. This framework enables a more straightforward estimation and interpretation of the model when latent variables are included, as is the case of the present study, where their scales were identified using the Fixed Marker method. Likewise, this estimation method allows for a more direct calculation of direct and indirect effects within the model, compared to estimation by ordinary least squares which requires ad-hoc methods for inference [

47]. Analyses are performed with the statistical software Stata version 15.

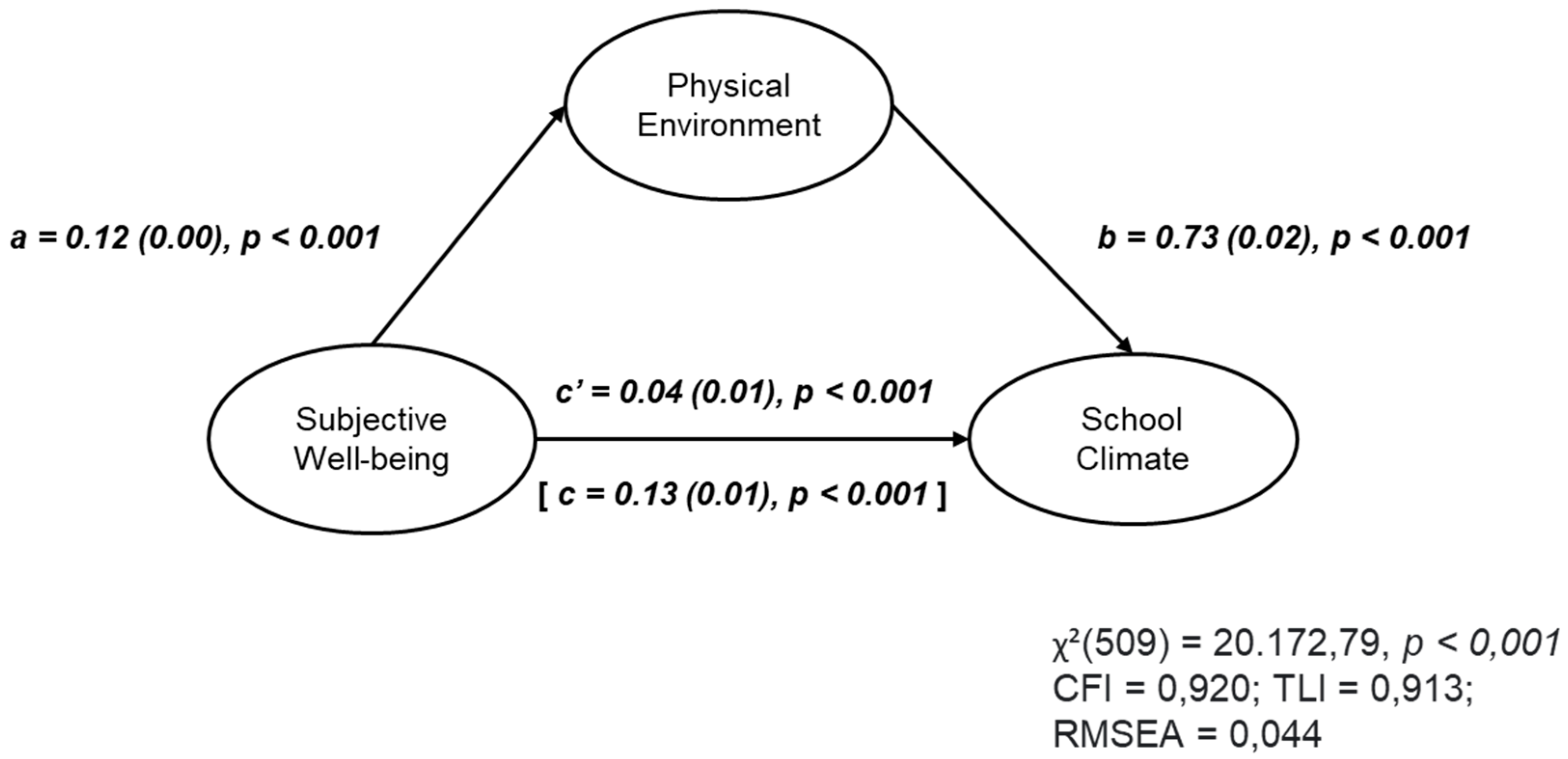

Figure 2 shows the complete diagram of the estimation.

4. Results

Pearson's correlation between the variables included in the analysis is shown in

Table 1. For all correlations the Bonferroni correction has been used to control the potential accumulation of Type 1 error (due to multiple comparisons). An auxiliary index of the instruments that was created based on the items composing them, was used to simplify the interpretation of this table. These items were qualified as the standardization of the average of the sum of the responses, with mean 0 and standard deviation equal to 1. The results show that both subjective well-being and perception of the physical environment have a positive and significant correlation with school climate. A positive and significant correlation is also found between the perception of the physical environment and the subjective well-being reported by students. Finally, a positive but non-significant correlation is observed between school climate and socio-economic status as measured by the SINAE index, indicating a certain degree of independence between both variables in the study sample.

The results of the model analysis identified the existence of a mediating relationship of the perception of the physical environment between subjective well-being and school climate (

Figure 3). It can be observed that, subjective well-being reported by students is positively related to the perception of the physical environment (

). In parallel, the perception of the physical environment is also positively related to the school climate (

). On the other hand, the total effect of students' self-reported subjective well-being of school climate is positive and significant (

). Although Baron and Kenny [

45] indicate as a necessary condition that the total effect of

X on

Y must be statistically significant, the most recent methodological recommendations indicate that this is not the case. According to Hayes [

46] it is not necessary for the total effect in a mediation model to be significant to detect a mediation effect, which ultimately depends on the theoretical formulation of the potential indirect effect (p.116). Thus, we check the total effect disaggregated into direct and indirect effects.

We followed the Delta method to obtain the total effects, direct and indirect, as well as the standard errors calculation. According to the results we can see that the direct effect of subjective well-being on school climate is statistically significant (). Then, to obtain the indirect effect of subjective well-being through the perception of the physical environment, it is necessary to multiply the coefficients and . Thus, the indirect effect associated with the perception of the physical environment is positive and statistically significant, (). Then, according to the results, the perception of the physical environment mediates the relationship between subjective well-being and school climate. About two thirds of the total effect of subjective well-being on school climate is mediated by the perception of the physical environment. The mediation is of a partial character because the direct effect is also statistically significant.

5. Discussion

The results of this study highlight the influence of perceptions of the physical environment on the relationship between students' subjective well-being and perceived school climate. It is observed that the perception of the physical environment can significantly modify the perception of both well-being and school climate, especially in schools with greater social vulnerability in Chile. Therefore, in order to improve well-being and school climate, it is crucial to address the variables of the physical environment, an educational demand repeatedly raised by Chilean students [

15], and to assess their perception of the infrastructure.

To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first in Latin America to address these issues in a comprehensive manner. Unlike previous studies that have analysed these variables independently, the inclusion of a mediation model in this study offers a more complete and complex view of the issue.

The results are relevant, since school climate has been identified as an important variable in reducing school dropout, especially in vulnerable schools [

48]. Likewise, international research has shown a relationship between a positive evaluation of school climate and the reduction of violence [

49]. Therefore, contributing to improve the school climate is fundamental to favor the academic development of students.

Future research should study which arguments students, teachers, and parents use to explain how the quality of the physical environment of the classroom modulates the relationship between climate and well-being. From this perspective, the international literature results provide three possible explanations. The first explanation is that school physical environment poor conditions favour the development of certain illnesses, such as colds, tiredness, and fatigue, which are related to a decrease in the psychological well-being of students and teachers [

50,

51].

The second explanation, instead, considers physical environment as directly associated with the perception of school climate [

19]. Finally, the third explanation relates to the frustration of not being able to repair the conditions of school buildings, which leads to a decrease in school climate and well-being. In other words, the insistent unmet demand of Chilean students to improve the environment of state-funded schools, if unheeded, could end up lowering the emotional state and thereby harming the school climate and subjective well-being of their students. Indeed, international research has reported how building trust and hope for future improvement is linked to greater well-being [

52]. This hypothesis needs to be further studied.

In the specific case of the physical environment of Chilean public schools, it is crucial to have more information on the state of school facilities to prevent problems that could affect the well-being of the school community as a whole. In Chile, the management of a school and the management of infrastructure and building repair follow separate paths. This apsect limits the ability of principals to directly address needed improvements in school facilities. The separation often results in inadequate repairs or inconvenience to the school community, such as disruptive noise during repairs. It is essential to address this gap and improve the management of physical environment conditions to promote more suitable environments for student learning and well-being. [

7].

Limitations

This study has the merit to have used a large sample of students (n = 19.567) who also belong to the most vulnerable schools in Chile. Furthermore, it uses a mediation model that relates variables little explored in the Latin American context.

The main limitation of the study is its cross-sectional design. Unfortunately, Chile does not currently have solid data and questionnaires that would allow a more accurate assessment of perceptions of the physical environment of classrooms and schools. On the other hand, the sample used is purposive, considering only students in public schools. This limits the possibility of extrapolating the results to the entire Chilean population.

In the future, the above problems could be improved if there were accurate, updated and continuous measurements of the perceived quality of the physical environment of classrooms and schools, taking into account different types of educational institutions. If more accurate information were available, longitudinal studies could be conducted to understand whether and how the perception of the physical environment of public schools has deteriorated, and how this deterioration is related to other variables such as school climate, subjective well-being or the increase in complaints of violence. We could also move towards comparative studies that show the differences between state-funded and privately-funded schools. This is important in a context, such as the Chilean one, with high levels of inequality and school segregation [

53].

6. Conclusions

In Chile, there has been a constant demand to improve the conditions of the physical environment. Chilean students have consistently expressed an unfavourable perception of these conditions, highlighting their impact on discomfort and identifying situations of unlivability and insecurity.

The aim of this article was to analyze the mediating effect of perceptions of the physical environment of the classroom on the perception of school climate and subjective well-being of students in public schools in Chile.

Our results showed a direct effect of subjective well-being on the school climate perceived by students. Specifically, a one standard deviation increase in the subjective well-being index corresponds to a 0.04 standard deviation increase in the school climate index. It was also observed how perceptions of the physical environment of the classroom mediated the relationship between subjective well-being and school climate, with perceptions of the physical environment mediating approximately 50% of the relationship between subjective well-being and school climate.

These results show that the physical environment is relevant to school climate, which is consistent with what has been reported in the international literature [

54,

55]. Similarly, perceptions of the physical environment contribute to subjective well-being, highlighting the importance of considering not only objective measures such as square metres, availability of materials, but also perceptions. Both public policies and international recommendations have focused on objective variables, without considering the voices of children and adolescents as active subjects in the construction of their own well-being [

56,

57,

58].

This result is undoubtedly an important finding within the Chilean school system. Public policy, instead of focusing on improving the physical environment of public schools, has systematically tended to support schools through formative aspects that seek to install capacities in teachers and students for good school climate management [

59]. In this sense, incorporating an assessment of the perception of the physical environment is highly relevant.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.A., S.P., K.C., L.G., V.A. and C.E.; methodology, P.A., S.P., K.C., L.G., V.A. and C.E.; formal analysis, P.A., K.C., and L.G..; writing (methodology, results, discussion and conclusions), P.A., S.P., K.C., L.G., V.A. and C.E; writing—review and editing, P.A., S.P., K.C., L.G., V.A. and C.E. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Agencia Nacional de Investigación y Desarrollo, Chile. SCIA ANID CIE160009, FONDECYT Project Number 1230581. ANILLO Project ATE 230072, FONIDE Project Number 2300074.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Bioethical committee of the Pontificia Universidad de Valparaíso (2018 approved).

Informed Consent Statement

Secondary data analysis was conducted. The Junta Nacional de Auxilio Escolar y Becas (JUNAEB) of the Ministry of Education requested assent and informed consent from stakeholders.

Data Availability Statement

Access to the databases was requested through a collaboration agreement between Junta Nacional de Auxilio Escolar y Becas (JUNAEB) and the Research Centre for Inclusive Education.

Acknowledgments

Junta Nacional de Auxilio Escolar y Becas (JUNAEB).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Annesi-Maesano, I.; Hulin, M.; Lavaud, F.; Raherison, C.; Kopferschmitt, C.; De Blay, F.; Charpin, D.A.; Denis, C. Poor Air Quality in Classrooms Related to Asthma and Rhinitis in Primary Schoolchildren of the French 6 Cities Study. Thorax 2012, 67, 682–688. [CrossRef]

- Borràs-Santos, A.; Jacobs, J.H.; Täubel, M.; Haverinen-Shaughnessy, U.; Krop, E.J.M.; Huttunen, K.; Hirvonen, M.R.; Pekkanen, H.; Heederik, D.J.J.; Zock, J.P.; Hyvärinen, A. Dampness and Mould in Schools and Respiratory Symptoms in Children: The HITEA study. Occup. Environ. Med. 2013, 70, 681–687. [CrossRef]

- Mendell, M.J.; Eliseeva, E.A.; Davies, M.M.; Spears, M.; Lobscheid, A.; Fisk, W.J.; Apte, M.G. Association of Classroom Ventilation with Reduced Illness Absence: A Prospective Study in California Elementary Schools. Indoor Air 2013, 23, 515–528. [CrossRef]

- Simons, E.; Hwang, S.A.; Fitzgerald, E.F; Kielb, C.; Lin, S. The Impact of School Building Conditions on Student Absenteeism in Upstate New York. Am. J. Public Health 2010, 100, 1679–-1686. [CrossRef]

- Toyinbo, O.; Shaughnessy, R.; Turunen, M.; Putus, T.; Metsämuuronen, J.; Kurnitski, J.; Haverinen-Shaughnessy, U. Building Characteristics, Indoor Environmental Quality, And Mathematics Achievement in Finnish Elementary Schools. Build. Environ. 2016, 104, 114–121. [CrossRef]

- Haverinen-Shaughnessy, U.; Shaughnessy, R.J. Effects of Classroom Ventilation Rate and Temperature on Students’ Test Scores. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0136165. [CrossRef]

- Finell, E.; Seppälä, T. Indoor Air Problems and Experiences of Injustice in the Workplace: A Quantitative and a Qualitative Study. Indoor Air 2018, 28, 125–134. [CrossRef]

- Villalobos, C., Morel, M.J.; Treviño, E., Eds.; Ciudadanía, educación y juventudes: Investigaciones y debates para el Chile futuro. Ediciones Universidad Católica de Chile: Santiago, Chile, 2021.

- Ponce, T.; Vielma, C.; Bellei, C. Experiencias educativas de niñas, niños y adolescentes chilenos confinados por la pandemia COVID-19. Rev. Iberoam. Educ. 2021, 86. [CrossRef]

- López, V.; Álvarez, J.P.; Calisto, A.J.; Aguilar, G.; Barrios, P.; Cárdenas, M.; Briceño, D.; Vera, M.; Marinao, H.; Romero, B.; Leiva, M. Apoyo al bienestar socioemocional en contexto de pandemia por COVID19: Sistematización de una experiencia basada en enfoque de Escuela Total. F@ro 2021, 1, 17–44. https://revistafaro.cl/index.php/Faro/article/view/645/637.

- TVN Noticias 24 horas. Denuncian plagas de ratones y palomas: Apoderados se toman colegio por deplorables condiciones sanitarias. Available online: https://www.24horas.cl/nacional/denuncian-plagas-de-ratones-y-palomas-apoderados-se-toman-colegio-por-deplorables-condiciones-sanitarias-5318724 (accessed on 25 January 2024).

- Colegio de Profesores y Profesoras de Chile. Ola de protestas en Chile develan la insalubridad y abandono de la educación pública. Available online: https://www.colegiodeprofesores.cl/2023/03/24/ola-de-protestas-en-chile-develan-la-insalubridad-y-abandono-de-la-educacion-publica/ (accessed on 25 January 2024).

- Reimers, F.; Schleicher, A.; Saavedra, J.; Tuominen, S. Supporting the Continuation of Teaching and Learning During the COVID-19 Pandemic. OECD: Paris, 2020. https://globaled.gse.harvard.edu/files/geii/files/supporting-the-continuation-of-teaching-and-learning-during-the-covid-19-pandemic.pdf.

- Reimers, F., Ed.; Unequal Schools, Unequal Chances: The Challenges to Equal Opportunity in The Americas (Vol. 5). Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, 2000.

- Baars, S.; Schellings, G.L.M.; Krishnamurthy, S.; Joore, J.P.; Den Brok, P.J.; Van Wesemael, P.J.V. A framework for exploration of relationship between the psychosocial and physical learning environment. Learn. Environ. Res. 2021, 24, 43–69. [CrossRef]

- Barrett, P.; Davies, F.; Zhang, Y.; Barrett, L. The Impact of Classroom Design on Pupils’ Learning: Results of a Holistic, Multi-Level Analysis. Build. Environ. 2015, 89, 118–133. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J.; McCabe, E.M.; Michelli, N.M.; Pickeral, T. School Climate: Research, Policy, Practice, and Teacher Education. Teach. Coll. Rec. 2009, 111, 180–213. [CrossRef]

- Astor RA, Guerra N, Van Acker R. How can we improve school safety research? Educ Res. 2010;39:69-78.

- Temkin D, Thompson JA, Gabriel A, Fulks E, Sun S, Rodriguez Y. Toward better ways of measuring school climate. Phi Delta Kappan. 2021;102:52-7).

- Zullig, K.J.; Koopman, T.M.; Patton, J.M.; Ubbes, V.A. School Climate: Historical Review, Instrument Development, and School Assessment. J. Psychoeduc. Assess. 2010, 28, 139–152. [CrossRef]

- Plank, S.B.; Bradshaw, C.P.; Young, H. An Application of “Broken-Windows” and Related Theories to the Study of Disorder, Fear, and Collective Efficacy in Schools. Am. J. Educ. 2009, 115, 227–247. [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, L.E. School Building Condition, Social Climate, Student Attendance and Academic Achievement: A Mediation Model. J. Environ. Psychol. 2016, 46, 206–216. [CrossRef]

- Connolly, D.M.; Dockrell, J.E.; Shield, B.M.; Conetta, R.; Cox, T.J. Adolescents' Perceptions of their School's Acoustic Environment: The Development of an Evidence-Based Questionnaire. Noise Health 2013, 15, 269–280. [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.; Lucas, R.E.; Oishi, S. Subjective Well-Being: The Science of Happiness and Life Satisfaction. In C. R. Snyder, S. J. Lopez, Eds.; Handbook of Positive Psychology. Oxford University Press: Cambridge, MA, 2002, pp. 463–73.

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. (2001). On Happiness and Human Potentials: A Review of Research on Hedonic and Eudaimonic Well-Being. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2001, 52, 141–166. [CrossRef]

- Diener, E. (1984). Subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin, 95(3), 542-575. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/0033-2909.95.3.542.

- Diener, E., Oishi, S., & Tay, L. (2018). Advances in subjective well-being research. Nature Human Behaviour, 2(4), 253-260. [CrossRef]

- Castilla, N.; Llinares, C.; Bravo, J.M., Blanca, V. Subjective Assessment of University Classroom Environment. Build. Environ. 2017, 122, 72–81. [CrossRef]

- Meng, X., Zhang, M., Wang, M. Effects of School Indoor Visual Environment on Children’s Health Outcomes: A Systematic Review. Health Place 2023, 83, 103021. [CrossRef]

- Han, H., Moon, H., Lee, H. Physical Classroom Environment Affects Students’ Satisfaction: Attitude and Quality as Mediators. Soc. Behav. Pers. 2019, 47, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Winterbottom, M.; Wilkins, A. Lighting and Discomfort in the Classroom. J. Environ. Psychol. 2009, 29, 63–75. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Becerik-Gerber, B.; Mino, L. A Study on Student Perceptions of Higher Education Classrooms: Impact of Classroom Attributes on Student Satisfaction and Performance. Build. Environ. 2013, 70, 171–188. [CrossRef]

- Scannell, L.; Hodgson, M.; García Moreno Villarreal, J.; Gifford, R. The Role of Acoustics in the Perceived Suitability of, and Well-Being in, Informal Learning Spaces. Environ. Behav. 2016, 48, 769-795. [CrossRef]

- Özyildirim, G. How Teachers in Elementary Schools Evaluate their Classroom Environments: An Evaluation of Functions of the Classroom Through an Environmental Approach. J. Effic. Responsib. Educ. Sci. 2021, 14, 180-194. [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, G.R. (2020). Marcas de la pandemia: El derecho a la educación afectado. Rev. Int. Educ. Justicia Soc., 45–59. [CrossRef]

- Senado de la República de Chile. Sesión Comisión de Educación, 27 de septiembre, 2023. Available online: https://tv.senado.cl/tvsenado/comisiones/permanentes/educacion/comision-de-educacion/2023-09-27/075024.html.

- Orellana, V.; Ed. Entre el mercado gratuito y la educación pública. LOM: Santiago, Chile, 2018.

- Cárdenas, K.; Ascorra, P. ¿Convivencia escolar y mercado educativo? Un análisis comparativo entre apoderados y estudiantes. Sinéctica, 57. [CrossRef]

- Ilabaca, T.; Corvalán, R. Configuración y legitimación del campo de los colegios de élite en Chile ¿Quiénes son y qué dinámicas han posibilitado su acceso a posiciones de poder en el campo educativo? Izquierdas, 2022, 51, 20. [CrossRef]

- Murphy, J. M., Abel, M. R., Hoover, S., Jellinek, M., & Fazel, M. (2017). Scope, scale, and dose of the world’s largest school-based mental health programs. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 25, 218–228. [CrossRef]

- Junta Nacional de Becas y Auxilios Escolares (JUNAEB; 2016). Sistema Nacional de Asignación con Equidad, SINAE 2016 [National System for Allocation with Equity, SINAE 2016]. Santiago de Chile: Unidad de Estudios, Departamento de Planificación y Estudios JUNAEB.

- Benbenishty, R.; Astor, R. School Violence in Context: Culture, Neighborhood, Family, School, and Gender. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2005. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195157802.001.0001.

- Alfaro, J.; Guzmán, J.; García, C.; Sirpolú, D.; Gaudlitz, L.; Oyanedel, J.C. (2015). Propiedades psicométricas de la Escala Breve Multidimensional de Satisfacción con la Vida para Estudiantes (BMSLSS) en población infantil chilena (10-12 años). Univ. Psychol. 2015, 14, 29–42. [CrossRef]

- López, V.; Torres-Vallejos, J.; Ascorra, P.; Villalobos-Parada, B.; Bilbao, M.; Valdés, R. Construction and Validation of a Classroom Climate Scale: A Mixed Methods Approach. Learn. Environ. Res. 2018, 21, 407–422. [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The Moderator–Mediator Variable Distinction in Social Psychological Research: Conceptual, Strategic, and Statistical Considerations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173-1182. [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach, 2nd ed.; The Guilford Press: New York NY, 2018.

- Gunzler, D.; Chen, T.; Wu, P.; Zhang, H. Introduction to Mediation Analysis with Structural Equation Modeling. Shanghai Arch. Psychiatry 2013, 25, 390–394. [CrossRef]

- López, V.; Ascorra, P.; Bilbao, M. A.; Oyanedel, J. C.; Moya, I.; Morales, M. (2013) El Ambiente Escolar Incide en los Resultados PISA 2009: Resultados de un estudio de diseño mixto." Ministerio de Educación de Chile (ed.) Evidencias para Políticas Públicas en Educación. Selección de Investigaciones Concurso Extraoridinario FONIDE-PISA (pp. 49-94). Santiago, Chile: Ministerio de Educación.

- Benbenishty, R., Astor, R. A., & Roziner, I. (2023). An eighteen-year longitudinal examination of school victimization and weapon use in California secondary schools. World Journal of Pediatrics, 1-12. [CrossRef]

- Sahakian, N.M.; White, S.K.; Park, J.H.; Cox-Ganser, J.M.; Kreiss, K. Identification of Mold and Dampness Associated Respiratory Morbidity in 2 Schools: Comparison of Questionnaire Survey Responses to National Data. J. Sch. Health 2008, 78, 32–37. [CrossRef]

- Miller, R.T.; Murnane, R.J.; Willett, J.B. Do Teacher Absences Impact Student Achievement? Longitudinal Evidence from One Urban School District. Educ. Eval. Policy Anal. 2008, 30, 181–200. https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w13356/w13356.pdf.

- Di Napoli, I.; Esposito, C.; Candice, L.; Arcidiacono, C. Trust, Hope, and Identity in Disadvantaged Urban Areas: The Role of Civic Engagement in the Sanità District (Naples). Community Psychol. Glob. Perspect. 2019, 5, 46–62. [CrossRef]

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD/OCDE). Revisión de recursos escolares en Chile. OECD: Santiago, Chile, 2017. Available online by request: https://bibliotecadigital.mineduc.cl/handle/20.500.12365/2157 (accessed on 25 January 2024).

- Wang, M.T.; Degol, J.L. School Climate: A Review of the Construct, Measurement, and Impact on Student Outcomes. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2016, 28, 315–352. [CrossRef]

- Bradshaw, C.P.; Waasdorp, T.E.; Debnam, K.J.; Johnson, S.L. (2014). Measuring School Climate in High Schools: A Focus on Safety, Engagement, and the Environment. J. Sch. Health 2014, 84, 593–604. [CrossRef]

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD/OCDE). Revisión de recursos escolares en Chile. OECD: Santiago, Chile, 2017. Available online by request: https://bibliotecadigital.mineduc.cl/handle/20.500.12365/2157 (accessed on 25 January 2024).

- Centro de Estudios de Políticas y Prácticas en Educación (CEPPE-UC). Estudio estima que faltan 5.717 salas para implementar en 100% la Jornada Escolar Completa. Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile: Santiago, Chile, 2016. Available online: http://ceppe.uc.cl/index.php/inicio/noticias/564-estudio-estima-que-faltan-5-717-salas-para-implementar-en-100-la-jornada-escolar-completa (accessed on 25 January 2024).

- Quevedo, S. Chile está por sobre el promedio de alumnos por sala de países de la OCDE. Publimetro: Santiago, Chile, 2016. Available online: https://www.publimetro.cl/cl/noticias/2016/06/01/chile-promedio-alumnos-sala-clases-paises-ocde.html (accessed on 25 January 2024).

- Ministerio de Educación [de Chile] (Mineduc). Plan de reactivación educativa 2023. Available online: https://www.mineduc.cl/plan-de-reactivacion-educativa-2023/ (accessed on 25 January 2024).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).