3.2. Social Factors Involved in Syndemic Interactions Including COVID-19

We identified three different framings of syndemics in this review: a) Syndemic interactions between COVID-19, and one or several diseases or medical conditions, and specific social factors; b) syndemic interactions between COVID-19 and the Social Determinants of Health (SDOH), and c) syndemic impacts of COVID-19 on specific populations. In this section we summarize factors included as part of the bio-social interface within these framings.

COVID-19 and non-communicable diseases (NCDs): Co-occurrence of NCDs and COVID-19 was the focus of 17 records (five of them original research studies) included in this review. In these cases, NCD (e.g. cardiovascular, nervous system, respiratory, kidney, and digestive diseases, as well as cancers and diabetes) were often grouped as comorbidities that, when experienced in contexts characterized by ‘socio-economic inequalities’, ‘social vulnerability’, and ‘social disadvantage’, enhanced vulnerability to COVID-19. These contexts were generally described in terms of indicators considered to have an impact on patients’ capacity to respond to COVID-19 and its control measures. Socio-economic inequalities, for example, were defined in terms of educational level, employment status, and income at individual, household, and area levels in India and Hong Kong [

23,

24]. Two publications used pre-existing vulnerability indexes to measure social disadvantage through indicators such as poverty levels, unemployment, population without health insurance, and housing crowding and ownership in specific geographical areas of the USA [

25,

26]. Susceptibility to COVID-19 in NCD patients was further described in terms of shared risk factors that were exacerbated during the pandemic, including sedentary behaviours and malnutrition [

27,

28,

29,

30,

31]. Opinion pieces discussed changes in food intake, as well as alcohol and tobacco consumption used as coping mechanisms to deal with control measures, as concrete forms in which COVID-19 affected people living with NCD [

31,

32,

33].

Pre-existing socio-environmental vulnerabilities were defined in terms of people’s exposure to poor sanitation systems and water and air pollutants, as well as consistently deficient access to health services, which particularly impacted those with higher exposure to NCDs such as undocumented migrants, indigenous communities, and workers linked with unregularized activities such as illegal mining and logging in the Brazilian Amazon [

34]. Variations in these indicators were associated with increased difficulties in illness management and as such, described as amplifiers or generators of syndemic vulnerability in NCDs patients [

35]. Urbanization, changing lifestyle habits, climate change, and pollution were also mentioned as factors leading to adverse COVID-19 outcomes in patients with NCDs [

27,

29,

33,

36].

COVID-19 and mental health: The impact of COVID-19 on mental health was studied in two original research articles [

37,

38]. In both cases, syndemic was used as a theoretical framework to explain disproportionate mental impacts in different population groups in Canada. These publications based their results on a cross-sectional monitoring survey administered to 125,000 members of an online panel that included questions on six individual dimensions of mental health. The authors reported on the detrimental impact on mental health of COVID-19 in the general population. However, groups considered to be at higher risk of experiencing structural vulnerability due to their race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, gender, sexual orientation, mental health, or disability, reported an even higher burden of mental health issues and more difficulties to cope with pandemic-related challenges. The association between COVID-19’s impacts on mental health and the pre-existing forms of social disadvantage concerning income, occupation, social support, living conditions, inequities, and emotional distress was further explored in opinion pieces [

39,

40,

41,

42]. The confluence of mental illness and substance abuse was suggested to lead to increased susceptibility to COVID-19 adverse consequences [

33,

42]. Social exclusion, social isolation, and stigmatization were presented as interfering with access to health services due to the additional mental health burdens generated by the pandemic [

40].

COVID-19 and other infectious diseases: Interactions between COVID-19 and other infectious diseases were also described as syndemic in nature. Specifically, interactions between COVID-19 and HIV-related comorbidities, HIV risk factors, and HIV-derived stigmatization, were considered when describing susceptibility to COVID-19 in people living with HIV (PLWH). A scoping review investigated the social and behavioural impacts of COVID-19 on this population during the first year of the pandemic [

43]. The syndemics framework was used to explain the mechanisms of interaction between COVID-19 and HIV as interlocking conditions: COVID-19 psychosocial sequelae (i.e., fear and anxiety) exacerbated mental health problems and contributed to structural inequalities affecting people living with unsuppressed HIV. The coexistence of tuberculosis (TB) and COVID-19 among displaced and migrant populations was also presented as a source of dual burden. Authors suggested that pandemic control measures may have increased TB-associated risks by reducing access to health services in this population [

44].

- b.

Syndemic interactions between COVID-19 and social determinants of health (SDOH)

Five records described syndemic interactions involving COVID-19 and socio-economic indicators grouped under the category of

social determinants of health (SDOH). Lee and Ramírez [

26] studied the associations between COVID-19 vulnerability and SDOH in Colorado. They used previously existing data on 14 social indicators including socioeconomic status, household composition, housing, and transportation, in relation to health-related variables, including mental health, obesity, and substance abuse. Associations were analysed under a syndemics perspective and the

Hazards of Place Framework (more details on

Section 3.3) to demonstrate that the overlap between mental health and chronic conditions, as well as “inequities in education, income, access to healthcare, and race/ethnicity” at the county level, exacerbated COVID-19 negative outcomes.

Similarly, Siegal et al. [

45] sought to describe a syndemic between structural racism and COVID-19 by assessing disparities in selected SDOH in predominantly black and white neighbourhoods in North Carolina (USA). Differences in income levels, employment, job density, and use of public food, nutrition, and health insurance services, as well as the proximity to school-age and early childhood care, low-cost healthcare, grocery stores, and public transit were quantitatively explored. The authors concluded that racially segregated communities, particularly black communities in the USA, already experienced detrimental conditions in multiple SDOH before the pandemic and that those inequities were exacerbated by COVID-19.

Some authors proposed to use a syndemics approach together with the SDOH framework to describe bi-directional relationships between susceptibility to disease and health inequities experienced by marginalized populations, including the elderly, children, people with disabilities, underinsured, socioeconomically disadvantaged, incarcerated, abused individuals, mentally ill, immigrants, refugees, and racial/ethnic minorities [

46,

47,

48].

- c.

Impacts of COVID-19 on specific populations

Thirteen records explored the differentiated impacts of COVID-19 on specific populations. In these cases, the authors emphasized that the conditions of marginalization, disadvantage or exclusion experienced by some population groups, particularly racial, ethnic, and gender minorities, as well as women and immigrants—not necessarily in relation to specific health conditions—made them increasingly vulnerable to the negative health and social consequences of this pandemic. Intersections between race, gender, and occupation in the generation of marginalization were highlighted. In most cases, syndemics theory was used as a framework to explore the multiple levels of impact of COVID-19 in these populations.

Most of the papers included in this category discussed the role of race and ethnicity in COVID-19 outcomes. Cokley et al. [

49] investigated how perceptions of discrimination and police brutality influenced COVID-19 experiences for black Americans in the USA. Perceptions of police brutality, discrimination, COVID-19 health threat, COVID-19/race-related stress, and cultural mistrust were assessed among inhabitants of metropolitan and rural areas with high concentration of Black/African population (Black, Black American, African American, African, Afro-Caribbean, and Afro-Latinx). The authors concluded that COVID-19 concerns were further exacerbated by police violence and poor mental health, which could also have resulted in low vaccination uptake in this population. Concurrently, precarious living conditions experienced by racial and ethnic minorities due to inequities in income, working conditions, access to health care, and housing were considered leading to negative COVID-19 outcomes [

50,

51]. Disparities were described for racial minorities and immigrants employed in crucial sectors such as healthcare [

52], hospitality services [

42], and transportation [

30]. Black women and birthing people (BWBP) and older adults experiencing pre-existing precarities and racial inequities were also presented as populations at risk of severe symptoms and worse COVID-19 outcomes due to their limited access to health care and interruption of services caused by control measures [

41,

53]. The pervasive effect of racism, race-associated social and health inequities, and racial injustice on health outcomes was extensively described in these publications.

The role of the relationship between occupation, race, gender and COVID-19 was further explored by Rogers et al [

54], who used syndemics theory as an interpretative lens to study the structural disadvantages putting street-based sex workers in New England at higher risk of COVID-19 [

54]. Researchers collected data on race, ethnicity, gender, gender identity, sexual orientation, and housing status, and documented changes in sexual and food consumption behaviours during the pandemic. This study concluded that street-based sex workers were at higher risk of COVID-19 and its social impacts due to co-occurring risk factors such as homelessness, food insecurity, mental health problems, substance use disorders, and STIs/HIV. Similarly, Sönmez et al. [

55] explained that immigrants represent an important proportion of the workforce of the hospitality services in the USA, and as such, were severely impacted by mobility restrictions that put them out of their jobs or reduced their sources of income. The authors argued that immigrant populations linked to these economic activities experienced syndemic risks derived from socio-economic inequities and excess chronic stress.

Finally, gender-differentiated impacts of COVID-19 were studied by Neto et al. [

56] and Duby et al. [

57]. The former [

56] argued that COVID-19 could have been experienced as a syndemic by gender and sexual minorities in Brazil due to various forms of vulnerability they have historically faced, including racial and gender discrimination, low education levels, precarious working conditions, and reliance on social support systems. The latter [

57] took a similar approach to study the impacts of COVID-19 on adolescents, girls, and young women (AGYW) in six districts in South Africa. Thus, syndemics theory was applied to understand how pre-existing situations of poverty, unemployment, food insecurity, and domestic violence in these populations were exacerbated by the pandemic. The authors claimed that their vulnerability was not only derived from gender or age but also from ongoing mental health stressors associated with lack of social support and economic stability; therefore, they proposed to apply an intersectionality lens in combination with syndemics theory to account for the intersecting identities impacting diseases outcomes in specific populations.

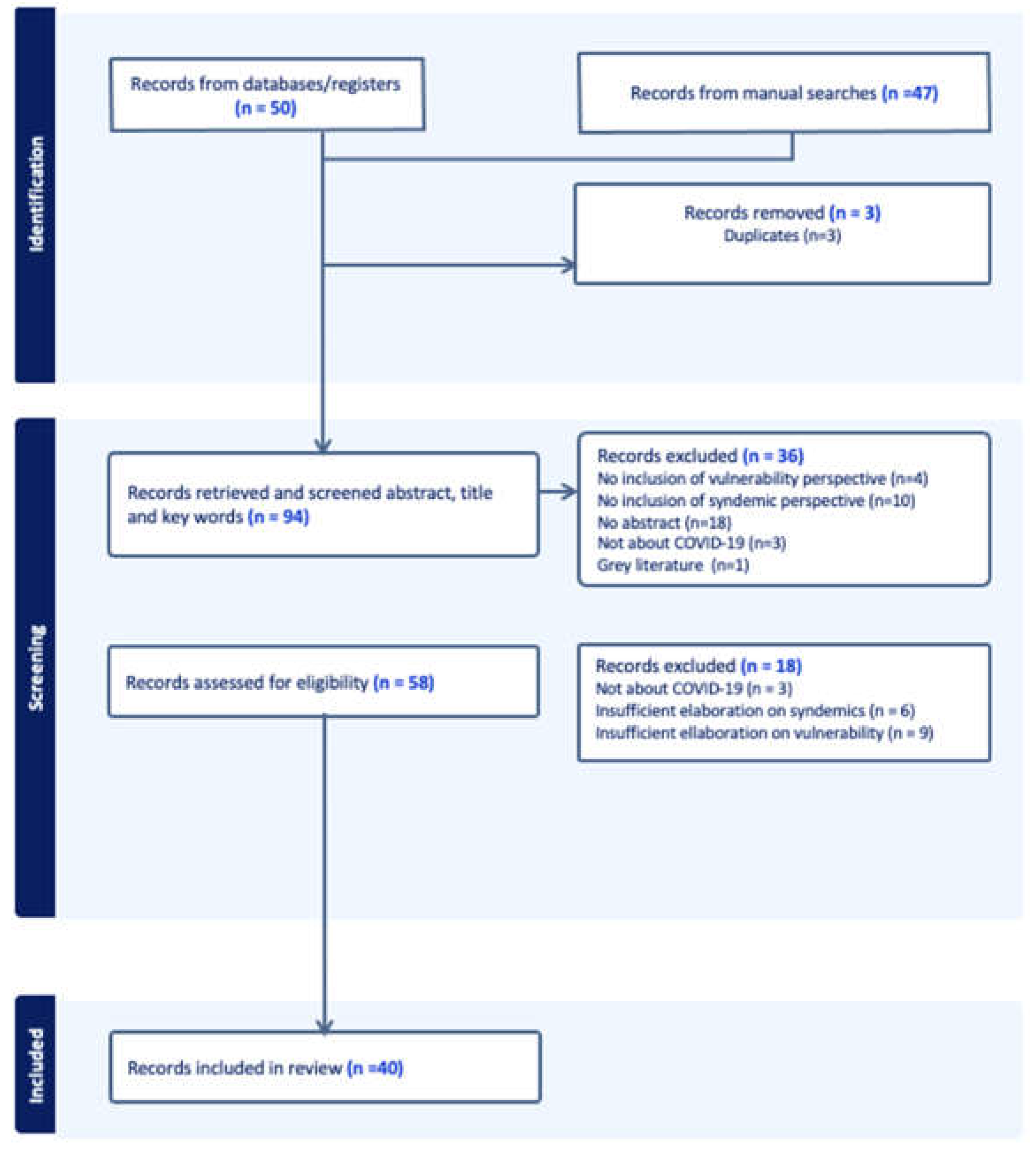

3.3. Which Methodological Approaches Were Used to Describe These Syndemics?

Out of the 13 original research studies identified in this review, eight (8) collected primary data [

23,

35,

37,

38,

49,

54,

56,

57], four (4) relied exclusively on secondary data [

24,

25,

26,

34], and one (1) combined secondary and primary data [

45]. None of the identified publications intended to demonstrate the existence of a particular syndemic; instead, they used syndemic theory as an interpretative lens (an approach, a theory, a concept, or a framework) to conceptualize and analyse emerging data.

Primary data. Five studies reported on data exclusively collected through surveys [

37,

38,

49,

54,

56], one reported on qualitative data [

23], and two more conducted online or telephonic interviews in addition to surveys [

35,

57]. Participants were drawn from ongoing cohorts organized to follow up on the health needs of the general population [

37,

38] or specific groups, including Black/African adults in the USA [

49] and Brazilian LGBT+ [

56]. Respondents were also identified through pre-existing networks and social interventions [

35,

54]. In all cases, data collection focused on understanding COVID-19 impacts on specific populations and social groups, as well as their particular needs during the pandemic. Only one group of authors reported on multiple administrations of the same survey [

37,

38]. Quantitative results were analysed using binary and multivariate logistic regression models as well as descriptive statistics, while qualitative results relied mainly on thematic coding.

Secondary data. Four studies worked with secondary data. In all cases, researchers used publicly available data collected by health institutions to track COVID-19 incidence, prevalence and/or mortality rates. Two groups of authors analysed individual data on NCD pre-existences and mental health indicators to characterize dynamics at the area levels. Using data on cases and deaths from COVID-19 published by the Amazonas State Health Department, Daboin et al. [

34] analysed different municipalities of the Brazilian Amazon region and explored multifactorial correlations between sex, age, indigenous ethnicity, and COVID-19 outcomes. These factors were individually studied and then extrapolated to community (municipality) conditions in relation to poverty, sanitation, and environmental degradation to conclude that “the impact of COVID-19 in the Amazon (…) may present characteristics of a syndemic due to the interaction of COVID-19 with pre-existing illnesses, endemic diseases, and social vulnerabilities.” In Hong-Kong, Chung and co-authors explored the distribution of severe COVID-19 cases in urban settings in relation to their socioeconomic position and pre-existent multimorbidities [

24]. Researchers used the reported address of COVID-19 confirmed cases as published by the Centre for Health Protection (CHP) of Hong Kong to produce “area-level income-poverty rates as the proxy measures of their socioeconomic position”.

As mentioned before, social factors were assessed using available census data or previously developed social vulnerability indexes (SVI) [

25,

26]. An SVI developed by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to identify counties particularly vulnerable to environmental disasters in 2018 was used in two publications. In order to characterize health and social vulnerabilities in Colorado, Lee and Ramírez [

26] used three different indexes: the CDC’s SVI to track specific social determinants (economic stability, education, community and social context); the health vulnerability index to track underlying health conditions such as diabetes, obesity, and mental health at the county level; and a third index developed during the study to show interactions between these two domains and COVID-19 burden rates. Islam et al. [

25] also used the SVI to determine social disadvantage at the county level; these data were included in a model of joint distribution of COVID-19 mortality and five chronic conditions (obesity, diabetes mellitus, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, heart disease, and chronic kidney disease) in the most vulnerable counties. Neto et al. [

56] adapted a vulnerability index previously applied to the LGBT+ population to assess personal and social vulnerability to COVID-19. This index measured what they defined as three vulnerability dimensions: income (defined as living with minimum salary or no income before the pandemic); COVID-19 exposure (described in relation to adherence to preventive measures and contact with people diagnosed with COVID-19), and health (including indicators such as being user of the public health system and being previously diagnosed with an NCD).

Geo-referenced data was also used to explore clustering of COVID-19. In the USA, Siegal et al. [

45] used GIS data (compiled in open mapping and transportation databases) to measure and compare distance to public facilities before COVID-19 in racially segregated communities. The authors proposed a place-based methodological framework to generate “contextually-informed, data-driven and cross-sector responses (…) that engage and empower communities”. Similarly, Lee and Ramírez [

26] used data available at the county level in Colorado to explore associations between SDOH and COVID-19 incidence. Due to the absence of data on COVID-19 distribution, the authors used a spatial interpolation model (Empirical Bayesian Kriging) to estimate census tract-level rates of COVID-19. A Hazards of Place Framework was used to identify clusters or “hotspots of persistent risk” in mountainous and urban areas of central and southern counties in the state.

3.4. Conceptualizations of Vulnerability under a Syndemics’ Perspective

Different definitions of vulnerability around syndemics were identified in the literature reviewed (Supplementary material S-3). Most definitions focused on explaining higher risk of infection, illness, or death by COVID-19. In this section we present three aspects of the vulnerability concept that were particularly salient in the literature about COVID-19 and syndemics: a) descriptions of vulnerability as a systemic issue, i.e., implying multiple levels and types of interactions; b) the role of COVID-19 control measures in the generation of new forms of vulnerability; and c) conceptualizations of COVID-19 as a syndemic in itself. We conclude this section with a summary of theoretical and programmatic discussions proposed around issues of vulnerability in different publications.

- a)

Vulnerability as a systemic problem

Multiple authors advocated for the use of the syndemics perspective as an application of systems’ thinking when researching vulnerabilities associated with COVID-19. These systemic views were interpreted as wider definitions of health [

29] in which disease occurrence cannot be dissociated from the specific context in which it emerges [

27]. The syndemics framework was used to describe a relationship in which COVID-19 ‘increased’, ‘visualized’, ‘hindered’, ‘deepened’, ‘exacerbated’, ‘reinforced’, or ‘perpetuated’ pre-existing conditions of social disadvantage, or ‘generated’ emerging vulnerabilities as a result of the public health measures implemented to control the pandemic. While most articles described bidirectional (mutually reinforcing) relationships between biomedical and social factors leading to syndemic outcomes or occurring in syndemic contexts, two groups of authors engaged in discussions about the causal link between syndemic interactions and COVID-19 outcomes. Daboin et al. [

34] referred to a “syndemic context” (described as the product of interactions between pre-existing diseases and social vulnerability) creating difficulties in diagnosing and treating COVID-19 in the Brazilian Amazon, and suggested a direct causal link between this context and high COVID-19 incidence and mortality in the region. Similarly, Mezzina et al. [

40] discussed the ‘multifactorial complex nature of causality in health’ and proposed a descriptive model in which different domains (social determinants, social vulnerability, and social inequalities, among others) act as a “web of determinants” with “non-linear and complex effects” over COVID-19 outcomes.

Individual vulnerability was described in relation to pre-existing health and social conditions enhancing COVID-19 susceptibility. The fact that these individual vulnerabilities often intersect and reinforce each other was often mentioned [

37,

57,

58]. As an example, vulnerability of girls and women was described as a result of intersecting identities that interact with their socio-economic status (e.g., living in poverty [

41]), living circumstances (in humanitarian settings [

39]), income-generation activities (e.g., sex workers [

54]), and health-related issues (e.g., HIV-related stigma, birthing conditions [

41], mental stressors [

57]) to create differentiated layers of risk in this population. While biologically speaking COVID-19 did not seem to particularly affect women, records included in this review described ‘gendered modes of transmission’ derived from limited access to health care and social services, the militarization of movement, extended impacts of gender-based violence, and drastic reductions in economic resources.

Subsequently, social vulnerability was characterized as “political decisions and cultural barriers” [

56], affecting the course of the pandemic. In this case, the focus of the analysis was not on the individual but on context-specific social circumstances impacting exposure to infections and the development of negative outcomes. Some authors described, for example, how the vulnerability of immigrants, refugees, racial/ethnic minorities, and indigenous communities, stemmed from a lack of access to quality healthcare systems. This absence not only predisposed them to particularly negative disease outcomes but also subjected them to substandard services during the pandemic [

34,

47,

52,

59]. As a consequence, several authors emphasized the need to think of health systems beyond the criteria of clinical cost-efficiency to enable systems that provide special protection to particularly at-risk populations as a way to break discriminatory and marginalizing healthcare practices [

50,

52,

53].

The living conditions under which marginalized populations concentrate were also explored in relation to socio-environmental vulnerability. Exposure to pollutants, limited healthcare opportunities in working and non-working environments, population density, social or, in some cases, geographical dispersion, were deemed to create susceptibilities in these populations that expressed as increased vulnerability during the pandemic [

24,

25,

29,

30]. Government-controlled confined spaces such as prisons and detention centres [

42,

48] were considered particularly conducive to increased SARS-CoV-2 transmission and worsened health outcomes, while humanitarian settings [

39,

58] were described as contexts where poverty, conflict, displacement, and lack of infrastructure coincided with and co-produced particularly devastating impacts of COVID-19.

At a higher level, structural vulnerability was treated as the “locus of danger, damage, and suffering” [

59] experienced by population groups according to their position within specific structures of power. This position was deemed critically relevant to understand the impacts of COVID-19. Power structures conferring and sustaining privilege during the pandemic based on race [

45,

49], age [

53], socio-economic position [

36], productive sector [

32,

42,

58], and health conditions [

37,

38,

48,

59] were extensively described. The structural role of racism, as a socio-political force underlying the conditions of marginalization experienced by racial and ethnic minorities, was mentioned in all publications dealing with this topic [

42,

52]. In addition, several authors described the important influence of political tensions around pandemic management in countries such as the USA, Mexico, Brazil, India, and Pakistan on negative COVID-19 outcomes and the accentuation of pre-existing structural vulnerabilities [

28,

34,

41,

48,

52,

59,

60].

COVID-19 was also analysed as a global problem that, as food insecurity, natural and technological disasters, climate change, and population mobility, provided evidence of emerging vulnerabilities. Although these risks were described as latent in the general population, they have also introduced particular forms of vulnerability in groups that have not been traditionally considered at risk. This included people suffering the consequences of the growing incidence of NCDs in high income countries [

28,

61], those whose income level rely on large-scale food chains [

31], and migrants for whom legal irregularity and uncertainties about the future are conducive to increased precariousness in several areas of life, including health care and social support systems [

44,

48,

55].

- b)

Emerging vulnerabilities: COVID-19 control measures

The generalized implementation of interventions to control COVID-19 transmission, including social (physical) distancing, lockdowns, mobility restrictions, and mask-wearing, was described as a COVID-19-specific form of vulnerability [

3,

5,

15,

30,

37,

38,

41,

46,

47]. Among its negative outcomes, researchers mentioned (i) increased poverty and unemployment, (ii) interruption of food supply chains, particularly those involving animal-based products [

27,

29]; (iii) severe impacts on the population’s mental health [

37,

38]; (iv) increased adoption of unhealthy lifestyles and substance abuse [

29,

43]; and (v) alterations in the seasonal patterns of respiratory infections [

27].

Both stay-home orders and the highly controlled movement of the population were connected to increasing gender-based and other forms of violence [

42,

49]. Gender-based violence (GBV) was a distinct phenomenon associated with previous outbreaks of infectious diseases such as Zika and Ebola in humanitarian settings [

39,

58]. It was presented as a pre-existing epidemic that often goes under the radar and worsened with the interruption of attention services due to control measures. Transferring lessons learned from previous epidemics and designing policy responses to tackle the syndemic relationships between infectious diseases and GBV was recommended.

These specific forms of damage derived from government and health systems’ responses to the emergency were considered a form of programmatic vulnerability [

56]. Importantly, authors who engaged in discussions on this topic mentioned the importance of using a syndemic approach to identify populations and regions that should be prioritized in the response to pandemic threats [

25,

27,

33,

37,

42,

48,

53,

57,

58,

59].

- c)

‘COVID-19 as a syndemic’ or “the syndemic nature of the pandemic”

An important feature of the scientific literature produced around the pandemic was the rapid spread of the expression “the COVID-19 syndemic”. In our review, five opinion pieces and four reviews (22.5%) adopted this term [

28,

29,

31,

33,

40,

46,

50,

60,

62]. Different from previous uses of the term to describe relationships between specific biomedical and social factors, in this case, the syndemic concept was used to: a) emphasize the large scale and diversity of COVID-19 impacts on vulnerable or marginalized populations; b) the diverse nature of factors and interactions involved in its occurrence; and c) the idea that the pandemic was simultaneously cause and consequence of pre-existing vulnerabilities [

27,

28,

29,

31,

40,

41,

47,

62]. This framing resembles the use of the expression “the syndemic nature of the pandemic”, through which authors emphasized how multiple and extensive interactions between pre-existing social and biomedical conditions resulted in the emergence of COVID-19 [

24,

27,

59,

60]. Singer and Rylko-Bauer further explained the use of this expression by describing how COVID-19 made clear the bio-social nature of health by brining attention on three aspects previously enounced in syndemics’ theory: a) interactions between diseases and health conditions that increase overall burden at multiple scales; b) interspecies interactions; and c) interactions with social dynamics underlying clustering of diseases and risks [

59].

Concurrently, the COVID-19 pandemic seemed to provide fertile ground to further apply syndemics-related terminology. For example, the term ‘syndemics framework’ was often employed to explain theoretical, methodological, and analytical decisions supporting the definition of specific interactions. ‘Syndemic contexts’ were mentioned to describe the resulting composition of social and geographic circumstances in which health conditions overlap [

34,

56,

60]. Some authors described the ‘syndemic effects’ [

27,

35,

38,

49] or the ‘syndemic outcomes’ of COVID-19 [

33,

47]. Finally, the term ‘syndemic vulnerability’ was referred to describe the multiple levels and nature of impacts of the pandemic on vulnerable populations [

38,

44,

48].

- d)

Theoretical, methodological, and policy recommendations on syndemics and vulnerability

In terms of theory, four reviews focused specifically on the implications of using syndemics theory in combination with other theoretical frameworks. Singer and Rylko-Bauer [

59] used the theoretical lens of syndemics and structural violence to analyse how different socio-environmental configurations engendered different syndemic interactions during the pandemic, exposed the global rise of NCDs and their potential interactions with infectious diseases, and brought light over profound problems in global health systems. According to the authors, while syndemics emphasize the synergistic interactions between biomedical conditions and socio-environmental factors, the concept of structural violence adds a focus on the effects of the ‘structures of inequality’ that sustain poverty and multi-dimensional discrimination. In their words, “‘structural violence’ drives syndemics”. These authors proposed that by using these two theoretical frameworks together, both originated in the critical anthropology field, practitioners can bring discipline-specific knowledge (around experiences of vulnerability, community organization and structures, and the social pathways of disease transmission, among many others) to inform contextualized public health responses to this global crisis.

Conceptual arguments around the idea of ‘context’ in syndemics research were explored by Pirrone et al [

61]. This group of authors conducted a literature review and expert interviews to explore how context has been defined and studied in syndemics research. Focused on syndemics involving NCD and mental health, they concluded that most studies centered on factors that affected populations at micro levels. They argued that, as a consequence, research tends to overlook structural factors shaping said contexts and in turn, limit the potential contributions if syndemics to COVID-19 management. Since this trend is closely influenced by the methodological designs previously used in the study of syndemics, this review recommended developing longitudinal and population-level analyses that incorporate multiple disciplinary views to study the impacts of context in COVID-19 outcomes. Expanding syndemics-informed research with multi-level and transdisciplinary research designs allowing integration of different data sets was recommended by multiple authors in this review [

30,

41,

45].

Concurrently, Fronteira et al. [

27] described COVID-19 as “One Health issue of syndemic nature”. Concretely, these authors referred to the important impacts of COVID-19 control measures on food systems, particularly in areas in which animals play a central role as food sources, income, transportation, fuel, and clothing, among others. Under this rationale, researchers advocated for “syndemic policies” to tackle interconnections between humans, animals, social, and abiotic environments engaged in COVID-19 transmission, which implies (i) learning from documented experiences; (ii) using theoretical frameworks that properly approach the multi-level, interacting and dynamic nature of the pandemic; and (iii) identifying community responses to COVID-19.

Transfer of knowledge and integration with previous experiences of infectious diseases management was another way of bringing the syndemics angle into programmatic actions. Garcia [

48] advocated for using syndemics theory in association with the SDOH framework as an opportunity to generate collaborations between social workers and the public health sector in the development of “biological-social interventions” for vulnerable populations at macro, mezzo, and micro levels. Additional policy recommendations identified in this review included integrating the management of COVID-19 and other respiratory diseases in migrant populations [

44]; informing policies for improving working conditions and workplace regulations considering diseases with syndemic potential [

55]; designing pandemic management and preparedness strategies with a focus on vulnerable and at-risk populations [

39,

51,

60]; and formulating public health actions that are grounded in mental health promotion under equity-oriented lens [

56].