2.1. Scarcity Theory and Teacher’s Time Poverty

Poverty is typically assessed based on income [

21]. However, despite the ongoing rise in wealth, individual satisfaction has not seen a proportional improvement [

22]. Nations and educational communities have progressively acknowledged the significant role of “time” as a non-financial element in enhancing individuals’ well-being and advancing socially sustainable progress, hence heightening focus on “time poverty”. Because of varying disciplinary perspectives, the conception of time poverty has not reached a unified. However, it can be broadly divided into objective and subjective levels. From the perspective of the objective, time poverty emphasizes the insufficient quantity of time allotted to various activities, such as physical exercise [

23]. On the subjective level, it emphasizes the individual’s subjective feeling of time poverty, such as their feeling that they do not have enough time to accomplish work [

24] and housework [

25]. Although the research on the objective “quantity” of time might well answer the structural allocation of teachers’ working time, that is, to explore the real amount of time occupied by teachers’ actual work. Nevertheless, it is important to distinguish between an actual lack of time and a perceived scarcity of time [

6]. In other words, the objective time number also needs to be subjectively perceived by individuals, which consequently impacts their cognitive processes, emotions, and behavior [

26]. Therefore, this study focuses on the subjective level to explore teachers’ time poverty.

At the same time, the Scarcity Theory argues that scarcity is a psychological state in which individuals’ aspirations and needs are not met due to actual or perceived lack of resources [

27]. Based on the Scarcity Theory, this study regards time as a scarce resource and emphasizes teachers’ subjective perception of time scarcity, whether it is an actual shortage of time or a perception of time scarcity. Therefore, teacher time poverty refers to teachers’ feeling that they have too many things to do, but have not enough time to do them [

6]. It emphasizes teachers’ subjective feelings about whether time resources are scarce. Furthermore, considering the complexity and cross-temporal character of teachers’ work [

28], as well as the relevant studies on the structure of teachers’ working time [

29], this study concludes that:

Hypothesis 1 (H1). Teachers’ time poverty has no significant difference in gender, teaching years and teaching sections.

Hypothesis 2 (H2). Teachers’ time poverty has significant difference in job responsibilities.

2.2. COR Theory, Job Burnout and Mental Health

Hobfoll (2001) established the Conservation of Resources Theory (COR) to describe the interplay of resources between individuals and the social environment, and he argues that job burnout is caused by resource consumption [

30]. Furthermore, during this process, the individual’s internal resources, including emotional resources, will have a specific influence on it [

30]. Wright and Bonett (1997) pointed out that mental health factors can be used as emotional resources, and negative mental health factors, such as depression and anxiety, are positively correlated with individual burnout [

31]. In other words, there are issues with teachers, such as how non-teaching working time consumes teaching time and encroaches on family time [

32]. These issues make teachers’ time resources increasingly scarce, consume their emotional reserves, exacerbate their mental health issues, such as depression, anxiety, and stress, and ultimately lead to an increase in job burnout.

Teacher job burnout refers to a state of exhaustion experienced by teachers due to long working hours, high workload and excessive work intensity [

33]. More than half of teachers in China experience emotional exhaustion and are becoming weary of their teaching responsibilities [

34]. This not only directly diminishes their passion and satisfaction [

35], but also increase the risk of turnover [

36]. Furthermore, it negatively affects the development of students and schools [

37]. In addition, studies have shown that there is a significant positive relationship between time poverty and teacher job burnout. Tianyu Liu and Qiang Wang (2024) explored the mediating role of teachers’ time poverty and found that time poverty, as a mediating variable, could positively and significantly predict teachers’ emotional exhaustion (a dependent variable) [

38]. In other words, teachers will feel that they do not have enough time to do their own work, which will increase their time poverty, resulting in job burnout [

39]. Therefore, we can infer that:

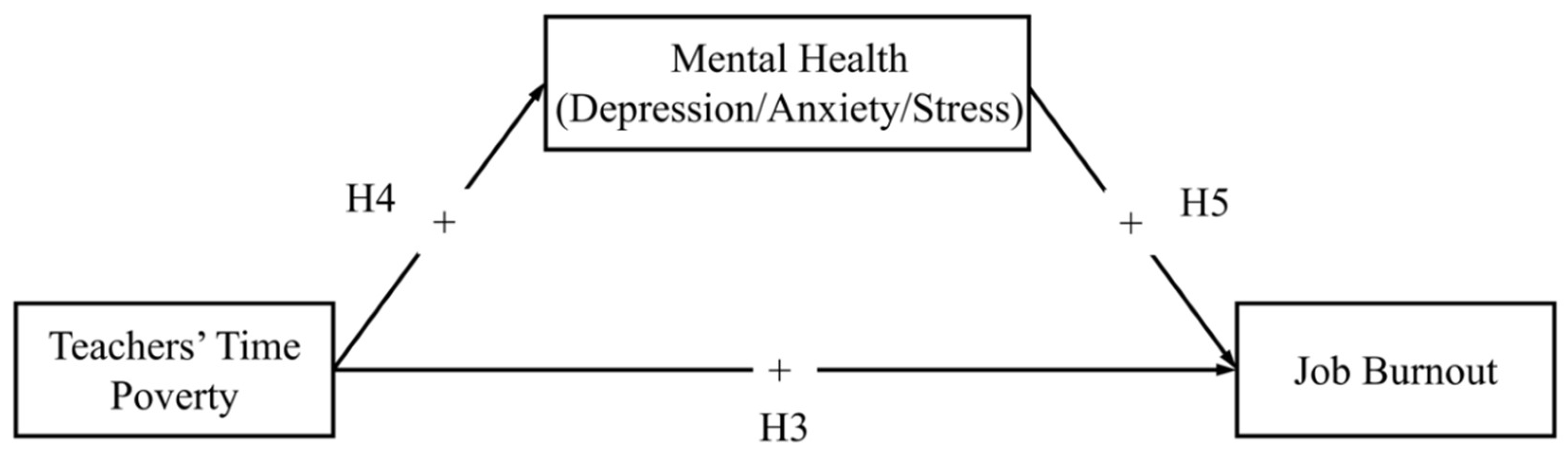

Hypothesis 3 (H3). Teachers’ time poverty could directly and positively predict job burnout.

In addition, teachers’ mental health issues are most commonly associated with negative emotional states such as depression, anxiety, and stress. [

13]. Although no direct research has been conducted on the association between time poverty and mental health issues among teachers, some studies have found that time poverty is connected to psychological characteristics such as depression and anxiety. For example, Roxburgh (2004) discovered that time poverty could positively predict depression when investigating the relationship between different family roles and depression [

40]. Urakawa et al. (2020) found that time poverty could cause individual anxiety, tension and other psychological results [

41]. According to the similar psychological reaction rules of the above groups, it is inferred that:

Hypothesis 4 (H4). Teachers’ time poverty could significantly and positively predict mental health (including depression, anxiety, and stress).

Previous studies have explored the negative effects of teachers’ mental health on their job burnout. For example, Kessler et al. (1988) believed that teachers under long-term work pressure would not only produce mental health problems such as anxiety, stress and depression, but also lead to job burnout [

42]. Yachao Li et al. (2021) found that teachers’ positive mental health factors could negatively and significantly predict their job burnout [

43]. Therefore, we can infer that:

Hypothesis 5 (H5). Teachers’ mental health could significantly and positively predict job burnout.

In summary, based on the Scarcity Theory [

27], Conservation of Resources Theory (COR) [

30] and related existing research, this study infers the relationship between teachers’ time poverty, job burnout and mental health factors. To be specific, we propose that teachers who lack sufficient time resources may deplete their mental health resources, leading to the onset and exacerbation of negative psychological emotions such as depression, anxiety, and stress. Consequently, teachers may eventually experience a sense of burnout. Therefore, we can infer that:

Hypothesis 6 (H6). Teachers’ negative mental health could play the mediating role in the relationship between teachers’ time poverty and job burnout.

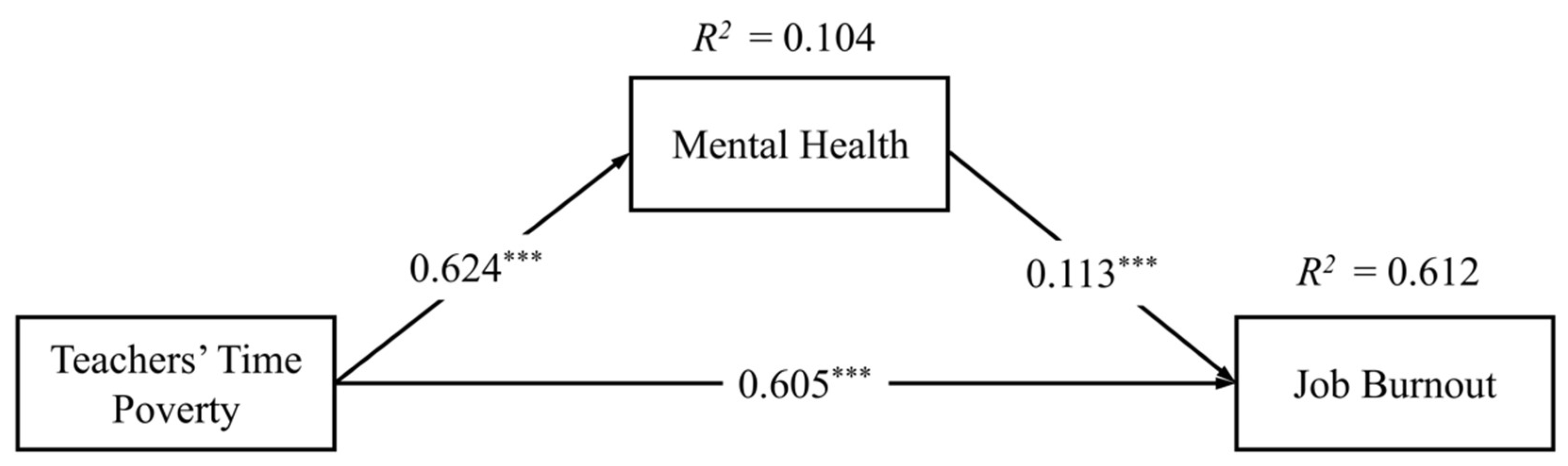

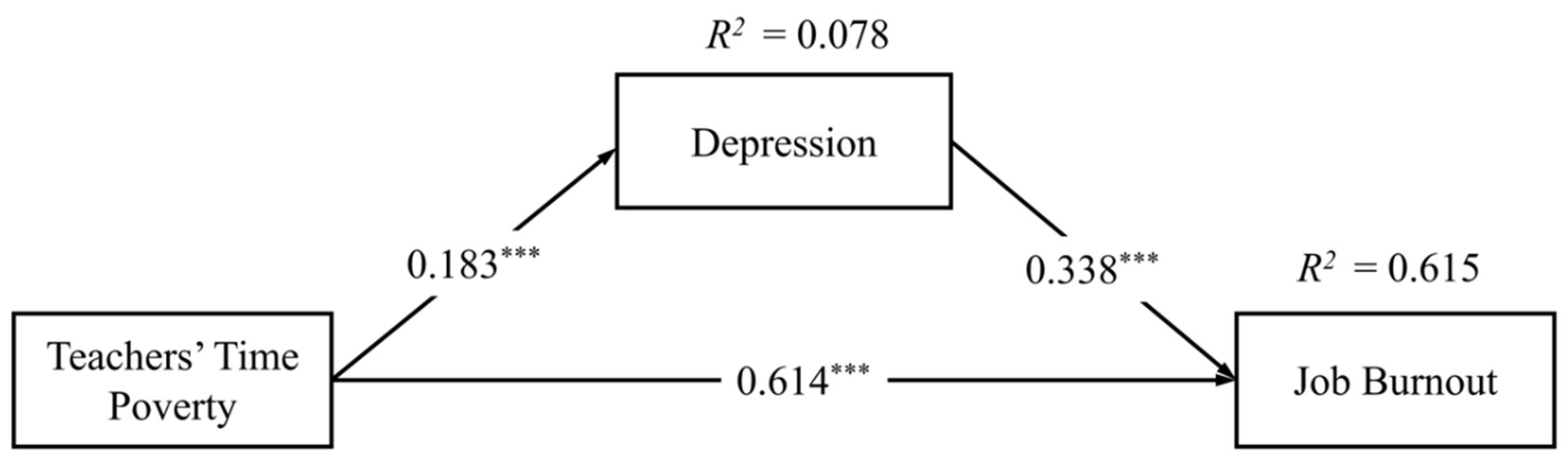

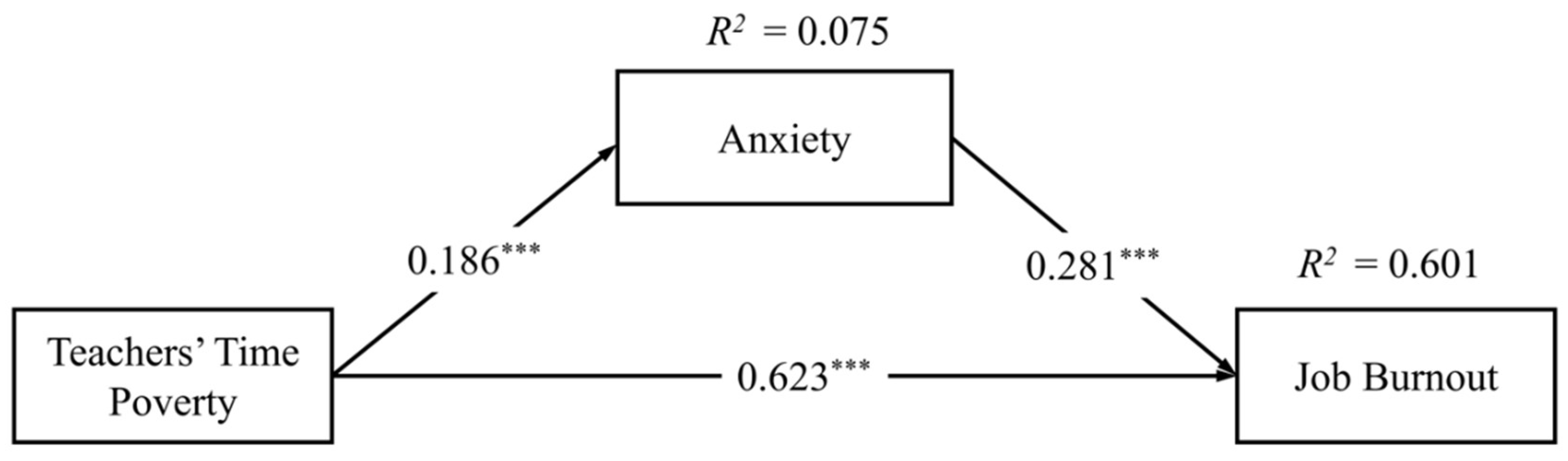

It is worth mentioning that mental health is treated as a whole in order to assess its mediating effect. Simultaneously, to better validate the relationship between variables and strengthen the credibility of the mediation model, this study investigates the mediating effects of three mental health factors: depression, anxiety, and stress, respectively. We can infer that:

Hypothesis 7 (H7). Teachers’ depression, anxiety and stress could play mediating roles in the relationship between teachers’ time poverty and job burnout, respectively.

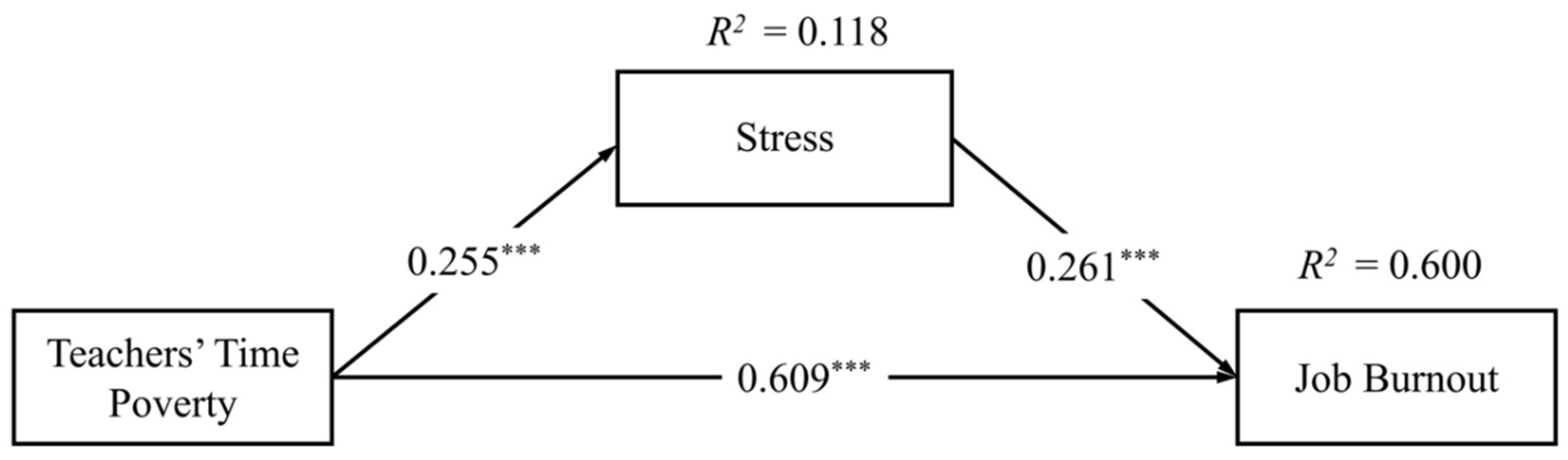

Hypothesis 3 to 7 are depicted in

Figure 1.