We present the case of a SSR secondary to EBV infection, in a 16-year-old, male patient. He presented in the Emergency Department complaining of acute upper left quadrant abdominal pain without any other reporting symptoms. The patient had been diagnosed three weeks prior to admission with IM with a positive Monotest and was recovering at home ever since. The patient had no significant medical history and was under no specific medication. No history of trauma was reported. On admission, he was mildly tachycardic (90bps/min) with evidence of localized peritonism on his left upper quadrant. Regarding the IM, no other symptoms were described. The first laboratory tests found the hemoglobin (Hb) of the patient to be normal (13.1 g/dL) and the leucocyte count slightly elevated (14.1x10 3 /μL).

An urgent abdominal ultrasound was performed that revealed an enlargement of the spleen (21 cm of diameter) with a large subcapsular hematoma (13 cm of diameter) and a significant amount of complex fluid within the abdominal cavity. In addition, and with the patient remaining hemodynamically stable, an abdominal Computer Tomography scan was performed and the enlargement of the spleen with maximum diameter of 21, 60 centimeters(cm) and the subcapsular hematoma were confirmed.

Figure 1.

Computer Tomography of the patient showing the enlargement of the spleen with maximum diameter of 21,60cm and the large subcapsular hematoma. The multidetector CT allows the detection and safe characterization of spontaneous splenic lesions, together with the identification or exclusion of active hemorrhage, perisplenic hemorrhage, or hemoperitoneum [

11]. In hemodynamically unstable patients with a potential splenic rupture, a fast-track ultrasound for detection of hemoperitoneum is the test of choice, although its sensitivity is limited for the detection of splenic rupture (72%–78%) [

5,

11].

Figure 1.

Computer Tomography of the patient showing the enlargement of the spleen with maximum diameter of 21,60cm and the large subcapsular hematoma. The multidetector CT allows the detection and safe characterization of spontaneous splenic lesions, together with the identification or exclusion of active hemorrhage, perisplenic hemorrhage, or hemoperitoneum [

11]. In hemodynamically unstable patients with a potential splenic rupture, a fast-track ultrasound for detection of hemoperitoneum is the test of choice, although its sensitivity is limited for the detection of splenic rupture (72%–78%) [

5,

11].

The patient was monitored closely for approximately one hour and a second blood test found the Hb to be 10.0 g/dl. Because of the drop in the Hb levels, the decision for an exploratory laparotomy was made. An emergency laparotomy was performed and a large amount of hemoperitoneum was evacuated from the abdominal cavity. The spleen was found enlarged with a subcapsular hematoma and a ruptured capsule. Emergent splenectomy was performed and the hemoperitoneum was evacuated. No other intra-abdominal pathology was noted. The patient received only crystalloid fluids and no blood transfusions. He recovered without any post-operative complications. His hemoglobin settled spontaneously in the next days and, gradually, he became afebrile. Prior to discharge he received the Pneumococcal, Meningococcal, and Hemophilus influenzae (Hib) vaccinations and was prescribed an appropriate post-splenectomy antibiotic prophylaxis. Pathologic examination revealed an enlarged spleen, weighing 820 g, with two large subcapsular hematoma (with maximum diameter of 13 cm) and a large laceration on its surface. The red pulp was enlarged because of an infiltration with a heterogeneous population of small lymphocytes, activated lymphoid cells, himmunoblasts, plasma cells and histiocytes. The diagnosis of SSR secondary to IM was confirmed.

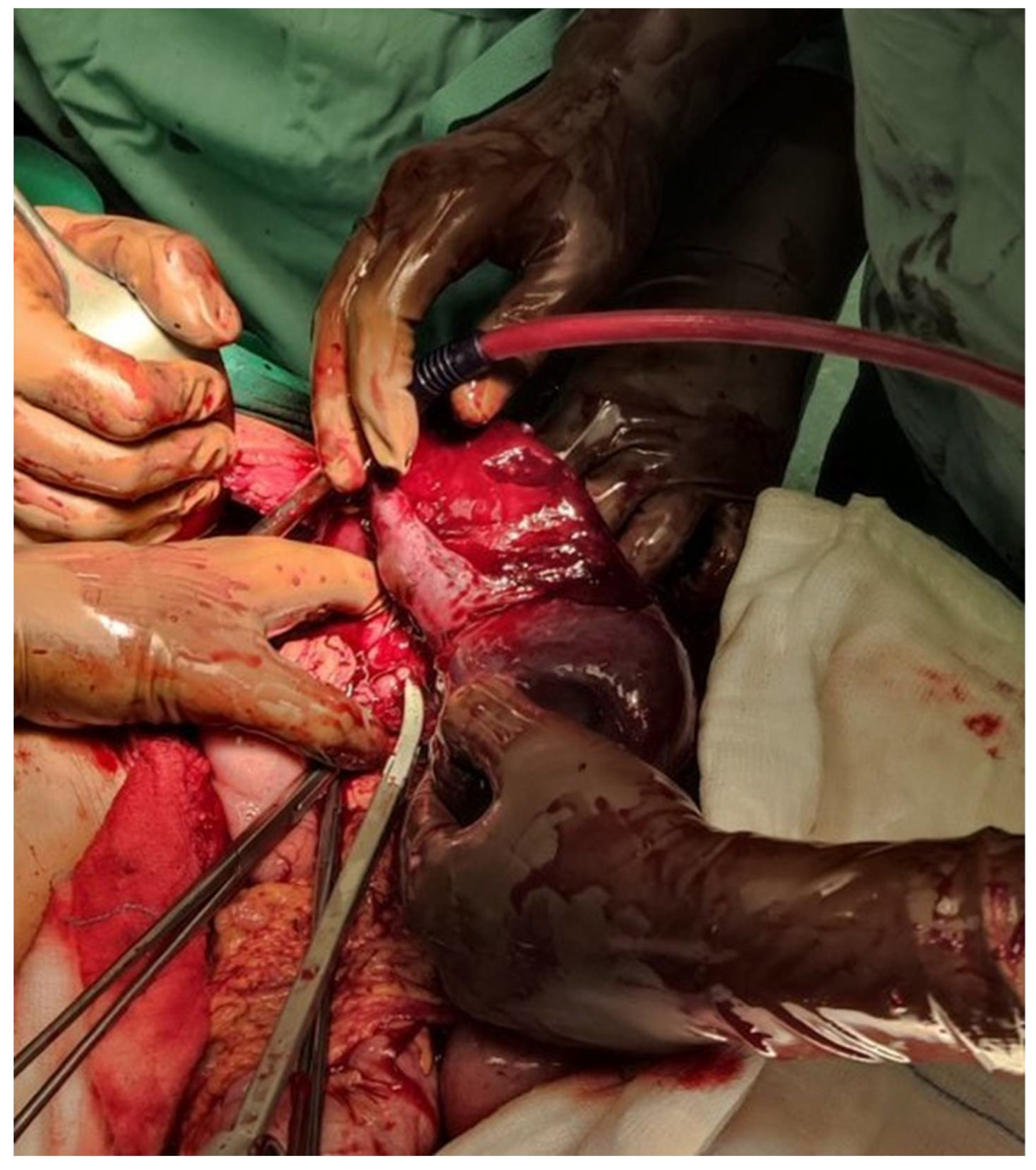

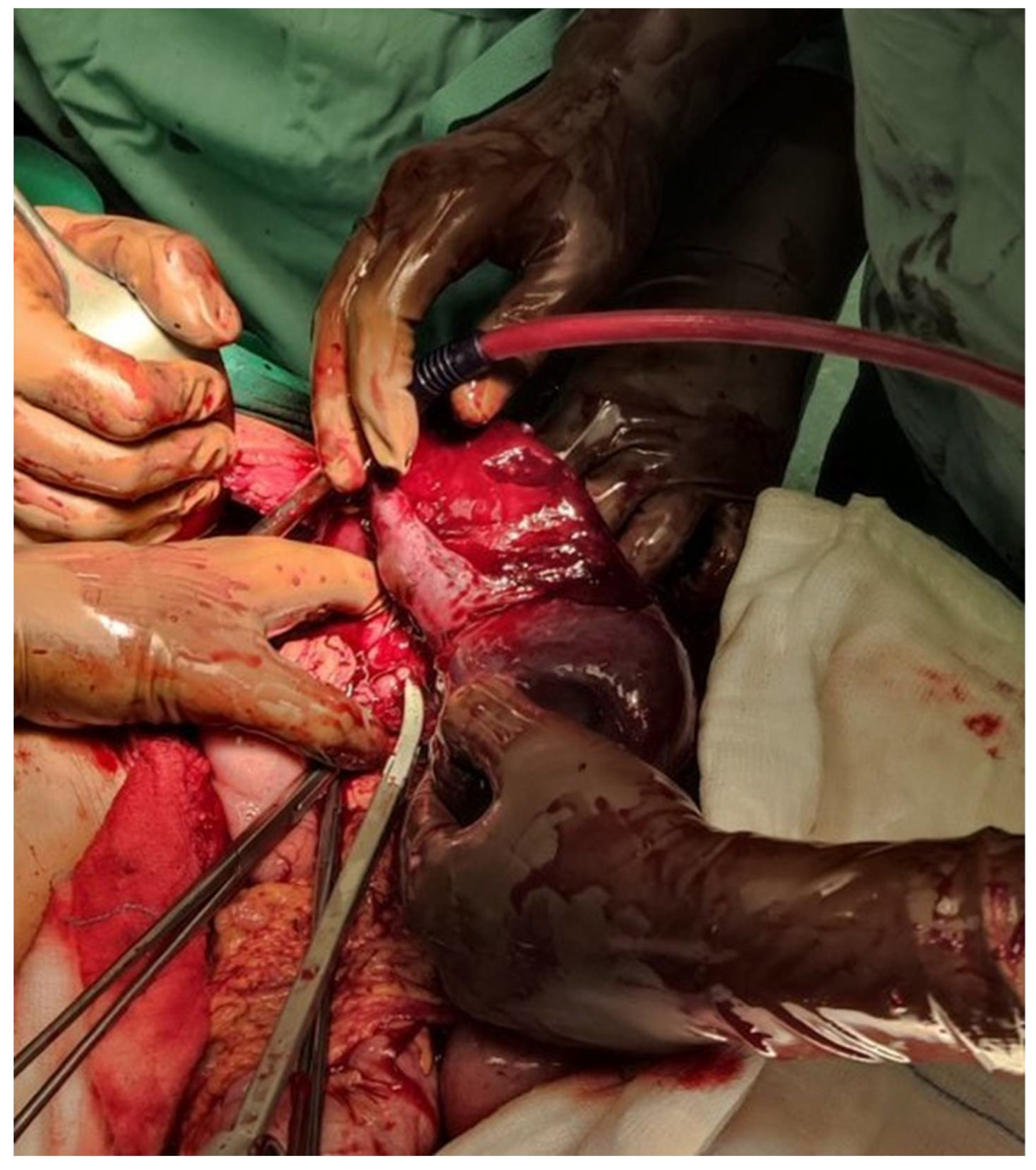

Figure 2.

An intraoperative image showing the enlargement of the spleen, the multiple lacerations on the splenic parenchyma and the rupture of the splenic capsule. The management of a splenic injury is generally a debate [

11]. It depends on hemodynamic status, resource availability, splenic injury grade, and presence of comorbidities [

5,

11]. If possible, the splenic preservation is to be preferred, especially in younger patients, to minimize the risk of post splenectomy infections and septicemia [

11,

13]. In hemodynamically stable patients with CT findings of active contrast extravasation, endovascular techniques such as splenic artery angiography with embolization to allow preservation of the spleen, may be the treatment of choice [

5,

12]. A splenic rupture requiring late surgery has been reported in patients whose initial CT shows a low-grade splenic lesion [

11,

15], so if all conservative treatment fails and the patient becomes hemodynamic unstable, a surgical exploration is recommended [

5]. When a surgical approach is necessary, a preservation of the spleen with splenorraphy or splenectomy and re-implantation.

Figure 2.

An intraoperative image showing the enlargement of the spleen, the multiple lacerations on the splenic parenchyma and the rupture of the splenic capsule. The management of a splenic injury is generally a debate [

11]. It depends on hemodynamic status, resource availability, splenic injury grade, and presence of comorbidities [

5,

11]. If possible, the splenic preservation is to be preferred, especially in younger patients, to minimize the risk of post splenectomy infections and septicemia [

11,

13]. In hemodynamically stable patients with CT findings of active contrast extravasation, endovascular techniques such as splenic artery angiography with embolization to allow preservation of the spleen, may be the treatment of choice [

5,

12]. A splenic rupture requiring late surgery has been reported in patients whose initial CT shows a low-grade splenic lesion [

11,

15], so if all conservative treatment fails and the patient becomes hemodynamic unstable, a surgical exploration is recommended [

5]. When a surgical approach is necessary, a preservation of the spleen with splenorraphy or splenectomy and re-implantation.

This case demonstrates the risk of an atraumatic splenic rupture in infectious mononucleosis and shows the importance of prompt diagnosis and appropriate counselling in patients IM. The IM is usually a self-limiting illness but its clinical presentation may be variable, and the classical triad may be absent [

1]. The most significant finding associated with IM is hepatosplenomegaly [

8]. A SSR complicating IM is a rare complication, occurring in 0.1-0.5 percent of patients with proven IM [

10]. During the EBV infection the mononuclear cells collect within the lymphoid tissue causing the enlargement of the spleen [

5]. In about 50% of patients with splenomegaly, as the spleen enlarges the splenic capsule thins and the spleen is vulnerable to laceration or rupture [

5]. of splenic tissue is to be pursued to avoid post splenectomy infections and sepsis [

5,

13].

Even with all the limitations our case report showcases an extremely rare but potentially fatal complication of IM. There is no international formal consensus on when patients should return to normal activities, but a splenic injury has been reported up to 8 weeks post-infection. Based on the current National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance advises, a patient suffering IM is advised ‘to avoid contact or collision sports or heavy lifting for the first month of the illness (to reduce the risk of splenic rupture) [

7]. Healthcare providers should remain vigilant, and a possible splenic rupture should be considered in any abdominal pain in IM.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing—Original Draft Preparation: Ismini Kountouri. Writing—Review and Editing: Ismini Kountouri; Evangelos Vitkos; Periklis Dimasis; Miltiadis Chandolias; Maria Martha Galani Manolakou; Nikolaos Gkiatas; Dimitra Manolakaki. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained. None of the data in the paper reveal the patient’s identity.

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ruymbeke, H.; Schouten, J.; Sermon, F. EBV: not your Everyday Benign Virus. Acta Gastroenterol Belg. 2020, 83, 485–487. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rajwal S, Davison S, Wyatt J, McClean P. Primary Epstein-Barr virus hepatitis complicated by ascites with Epstein-Barr virus reactivation during primary cytomegalovirus infection. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2003;37(1):87–90.

- Fugl, A.; Andersen, C.L. Epstein-Barr virus and its association with disease - a review of relevance to general practice. BMC Fam. Pract. 2019, 20, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartlett, A.; Williams, R.; Hilton, M. Splenic rupture in infectious mononucleosis: A systematic review of published case reports. Injury 2016, 47, 531–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sergent SR, Johnson SM, Ashurst J, Johnston G. Epstein-barr virus-associated atraumatic spleen laceration presenting with neck and shoulder pain. Am J Case Rep. 2015; 16:774–777.

- Odumade, O.A.; Hogquist, K.A.; Balfour, H.H., Jr. Progress and Problems in Understanding and Managing Primary Epstein-Barr Virus Infections. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2011, 24, 193–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, C.R.; Kona, S. Spontaneous splenic rupture in a patient with infectious mononucleosis. BMJ Case Rep. 2019, 12, e230259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ceraulo, A.S.; Bytomski, J.R. Infectious Mononucleosis Management in Athletes. Clin. Sports Med. 2019, 38, 555–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aldrete, J.S. Spontaneous Rupture of the Spleen in Patients with Infectious Mononucleosis. Mayo Clin. Proc. 1992, 67, 910–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odalovic, B.; Jovanovic, M.; Stolic, R.; Belic, B.; Nikolic, S.; Mandic, P. Spontaneous splenic rupture in infectious mononucleosis. Srp. Arh. za Celok. Lek. 2018, 146, 320–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Ramos JJ, Marín-Medina A, Lisjuan-Bracamontes J, Garciá-Ramírez D, Gust-Parra H, Ascencio-Rodríguez MG. Adolescent with Spontaneous Splenic Rupture as a Cause of Hemoperitoneum in the Emergency Department: Case Report and Literature Review. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2020;36(12): E737–E741.

- Barnwell, J.; Deol, P.S. Atraumatic splenic rupture secondary to Epstein-Barr virus infection. BMJ Case Rep. 2017, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Purkiss, S.F. Splenic Rupture and Infectious Mononucleosis-Splenectomy, Splenorrhaphy or Non Operative Management? J. R. Soc. Med. 1992, 85, 458–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, G.Y.; Chan, A.K.; E Powis, J. Possible infectious causes of spontaneous splenic rupture: a case report. J. Med Case Rep. 2014, 8, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, H.; Kumar, V.; Spencer, K.; Maatouk, M.; Malik, S. Spontaneous splenic rupture: A rare life-threatening condition; Diagnosed early and managed successfully. Am. J. Case Rep. 2013, 14, 13–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).