Submitted:

03 June 2024

Posted:

04 June 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Preparation of Lunasin-Enriched Soybean Extract (LSE)

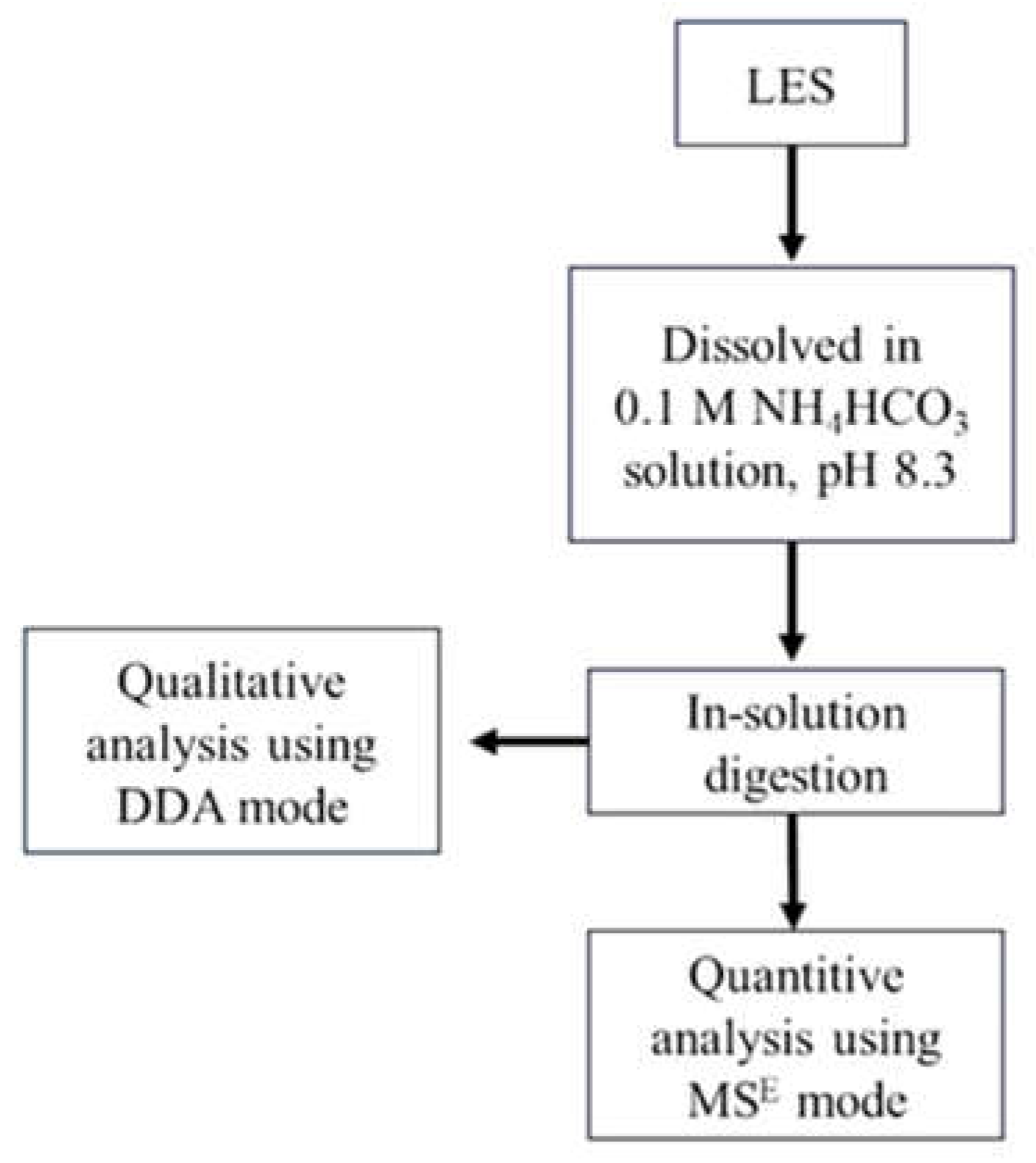

2.3. Proteomic Analysis of the Lunasin-Enriched Soybean Extract (LSE)

2.3.1. In-Solution Digestion

2.3.2. Analysis of the In-Solution Digested Lunasin-Enriched Soybean Extract (LSE) Samples by Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC–MS/MS)

2.3.3. Bioinformatics Analysis

2.4. Analysis of the Intact Proteins (2S Albumin and Its Subunits) in the Lunasin-Enriched Soybean Extract (LSE)

2.4.1. Separation of Lunasin-Enriched Soybean Extract (LSE)-Fractions by Ultrafiltration

2.4.2. Analysis of the Intact Proteins by LC–MS

2.5. Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Activity of the Lunasin-Enriched Soybean Extract (LSE)

2.5.1. Cell Culture

2.5.2. Effects on Cell Viability

2.5.3. Cell Infection by H. pylori

2.5.4. Effects on Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Generation

2.5.5. Effects on Cytokine Production

2.6. Antimicrobial Activity against H. pylori of Lunasin-Enriched Soybean Extract (LSE)

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

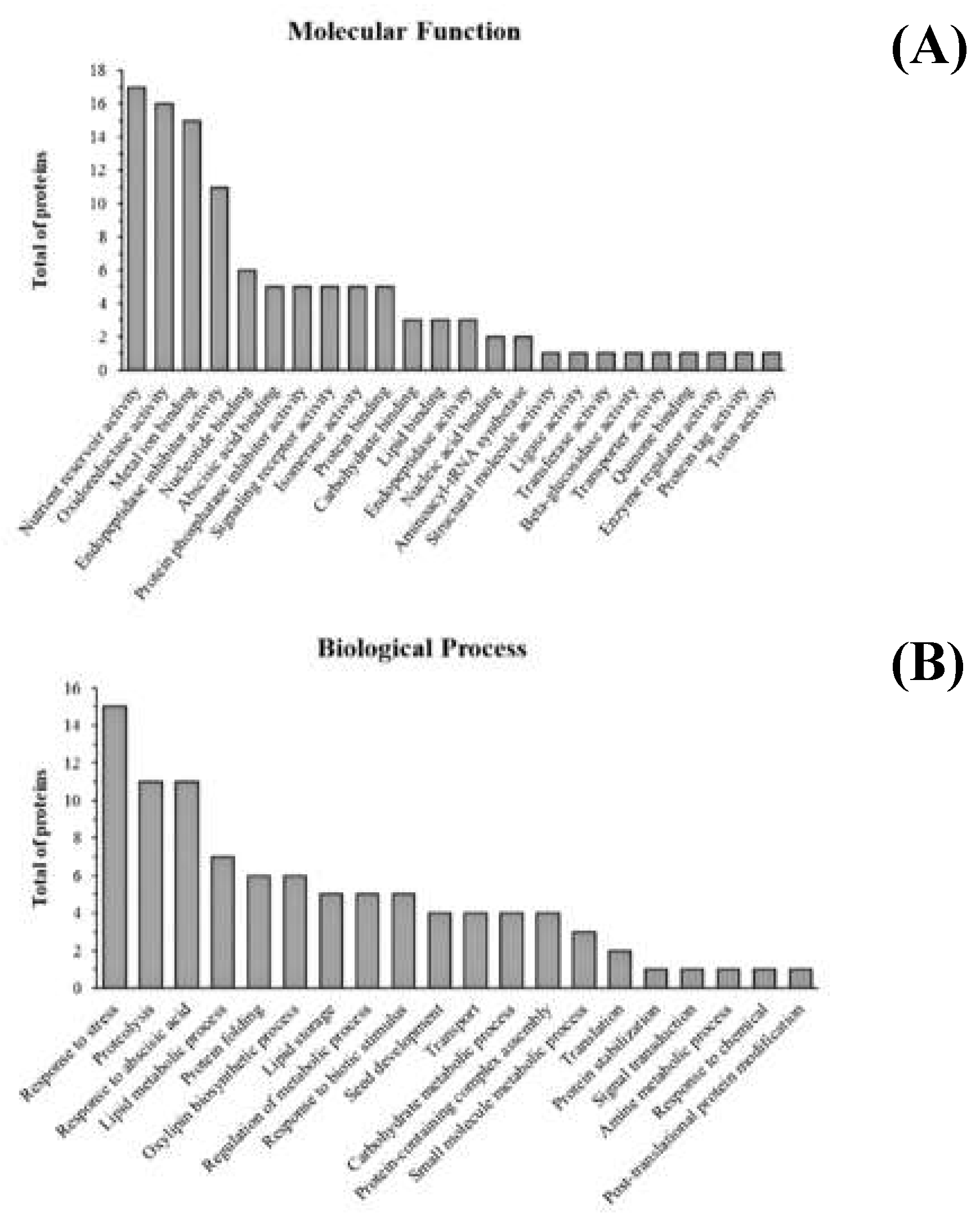

3.1. Proteomic Characterization of the Lunasin-Enriched Soybean Extract (LSE)

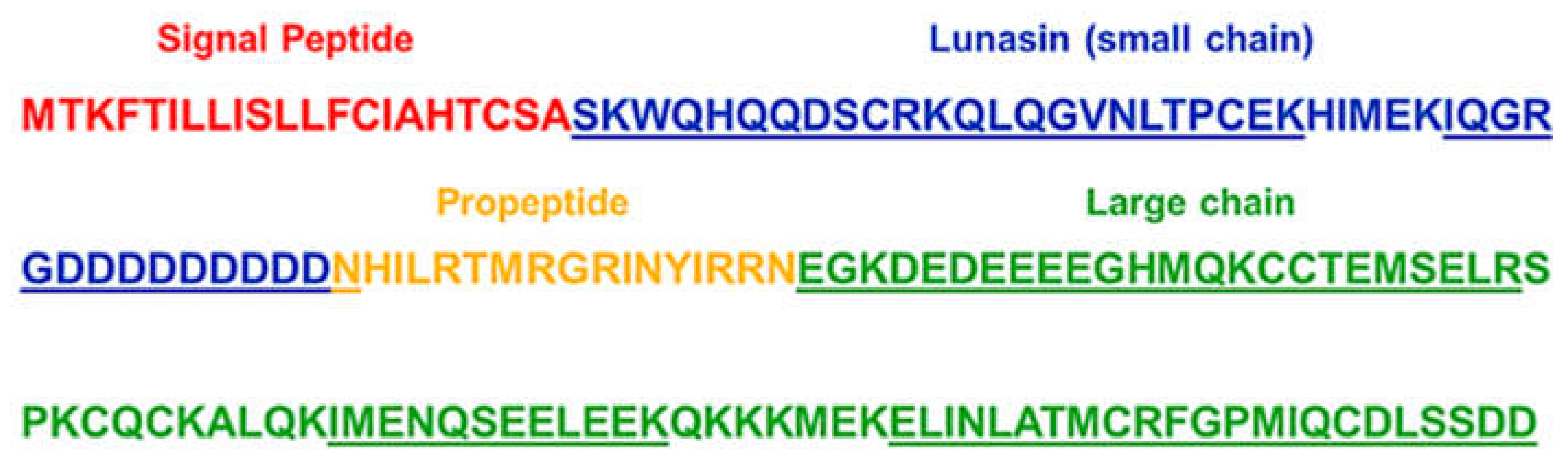

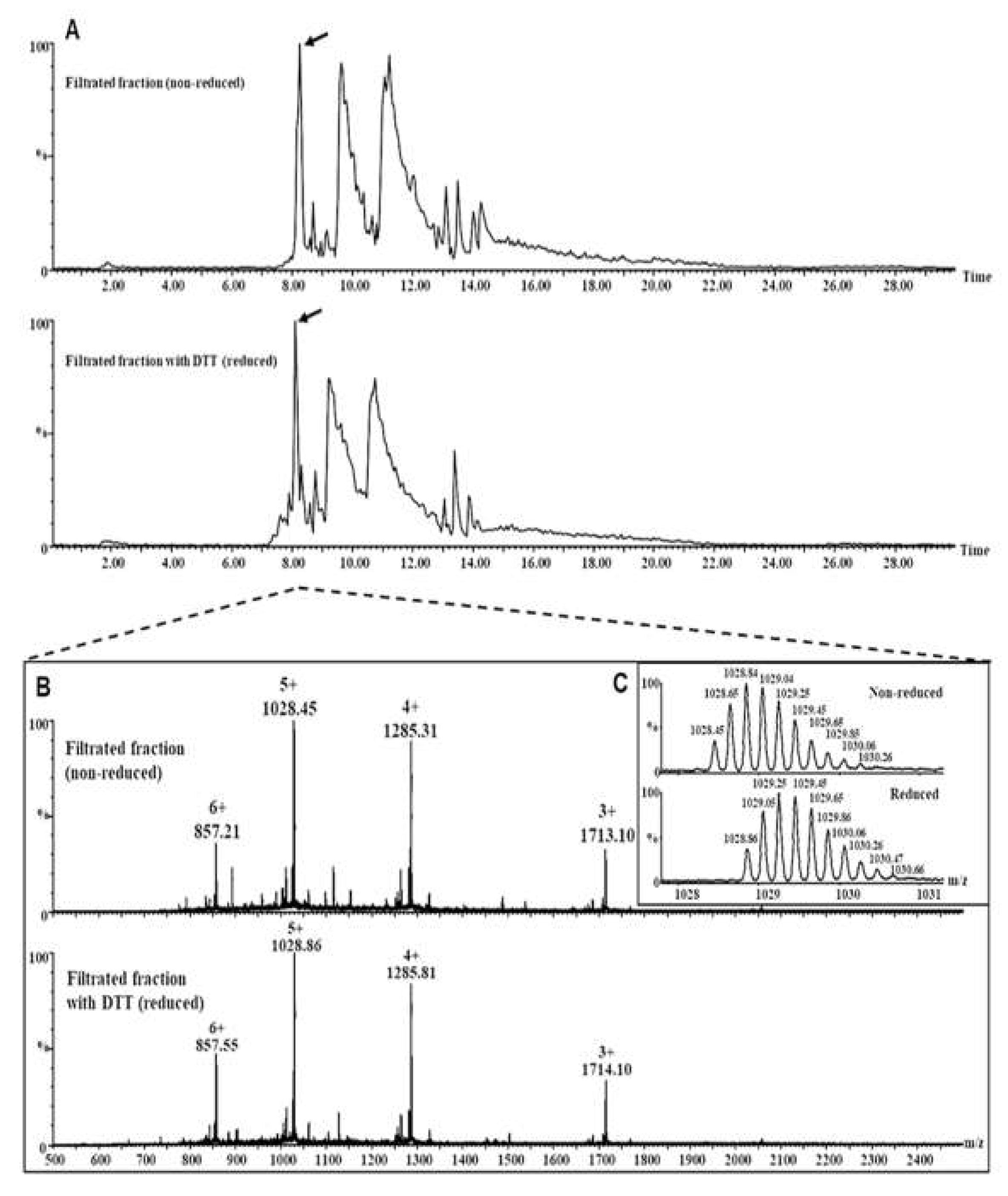

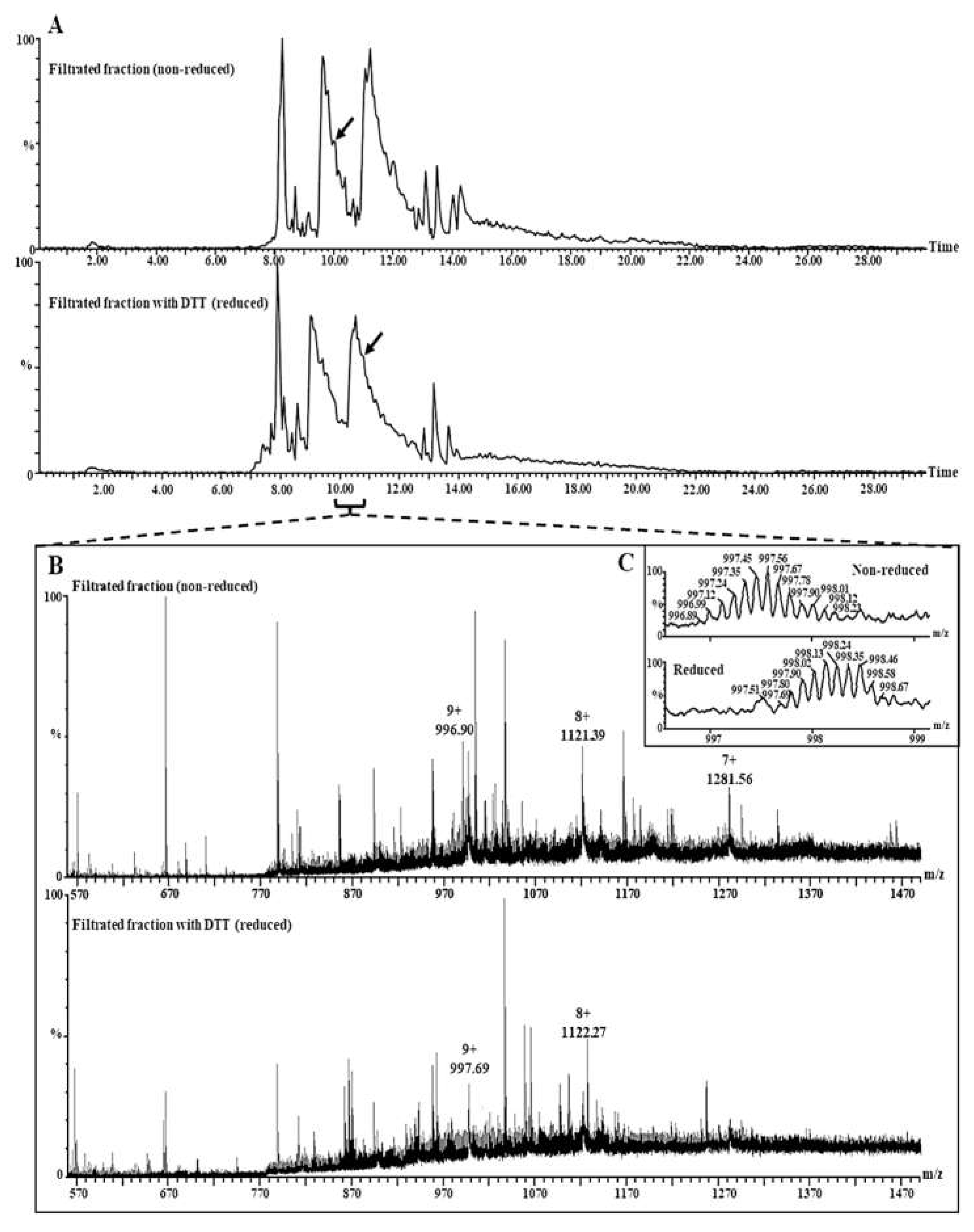

3.2. Structural Analyses of the Lunasin in the Lunasin-Enriched Soybean Extract (LSE)

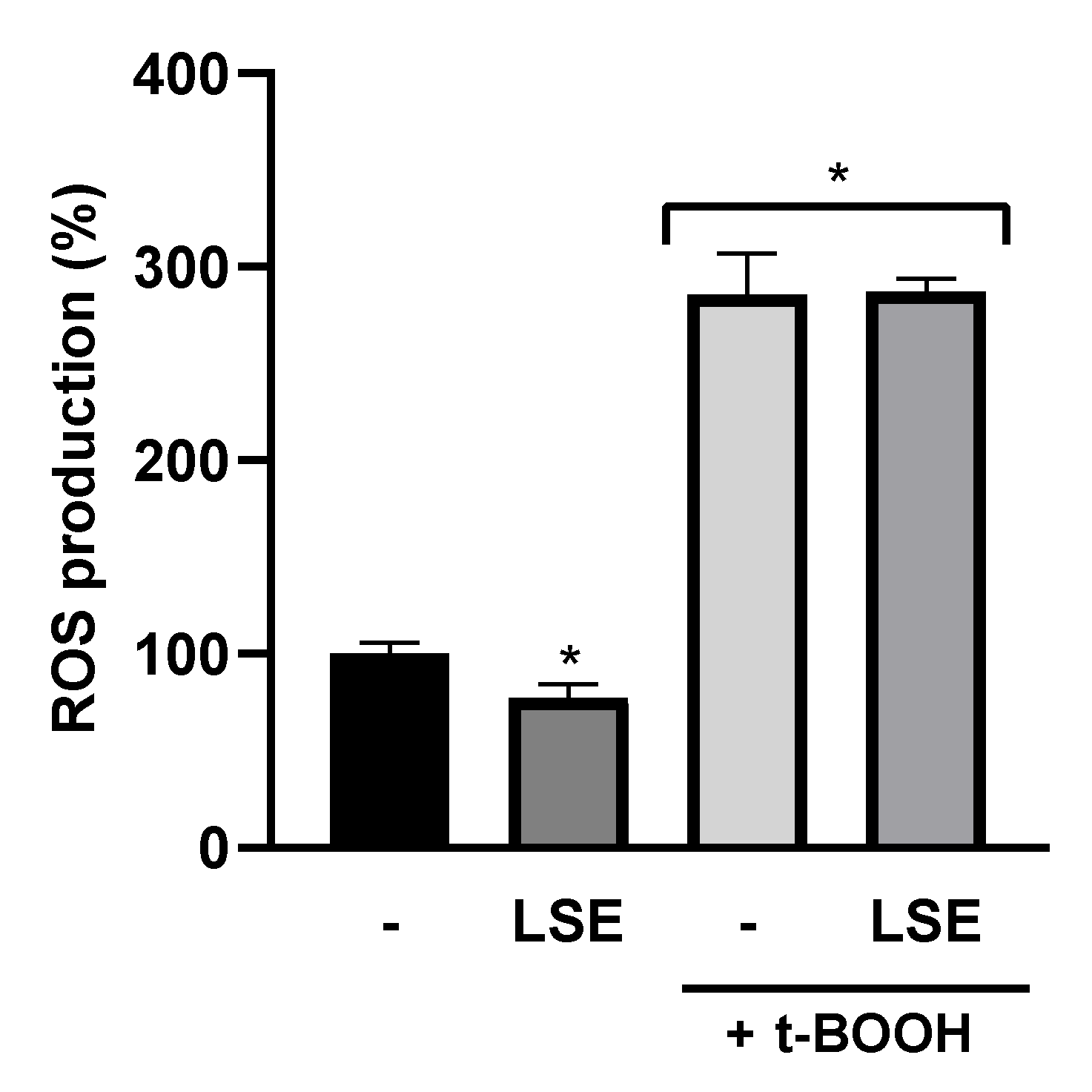

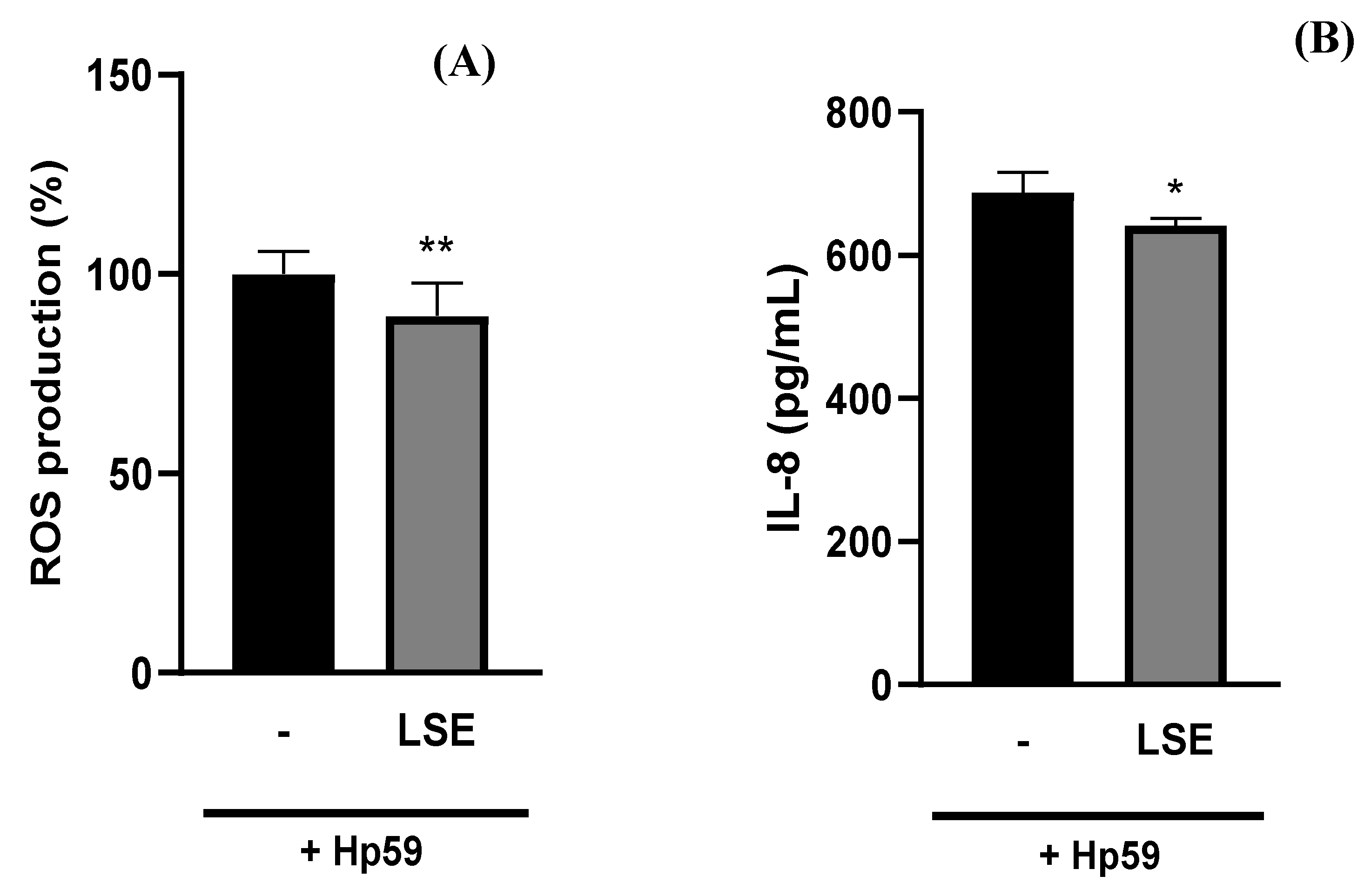

3.3. Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Activity of LSE

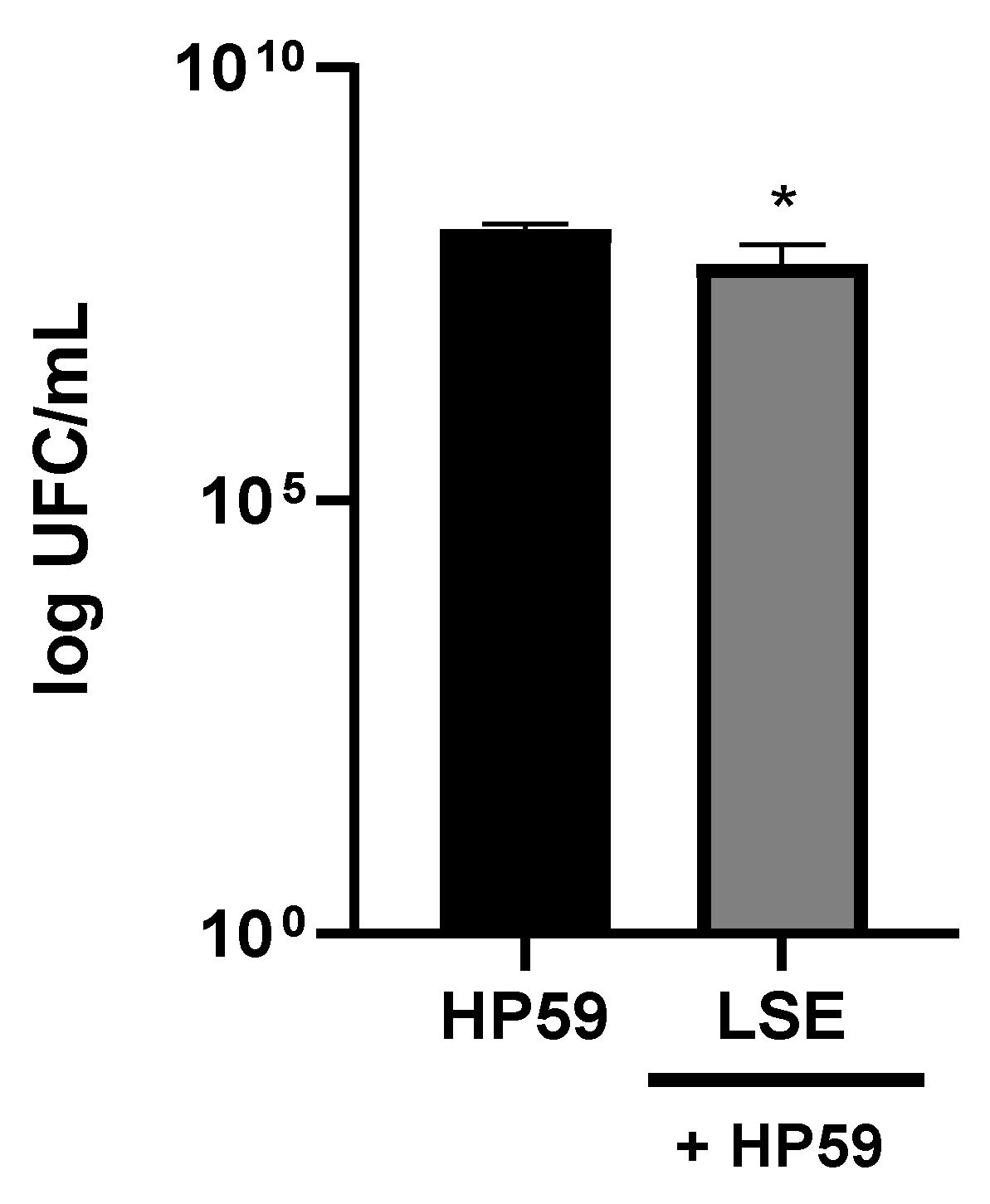

3.4. Antimicrobial Activity of LSE against H. pylori

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hooi: J.K.Y.; Lai, W.Y.; Ng, W.K.; Suen, M.M.Y.; Underwood, F.E.; Tanyingoh, D.; Malfertheiner, P.; Graham, D.Y.; Wong, V.W.S.; Wu, J.C.Y.; et al. Global prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection: systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterology 2017, 153, 420–429. [CrossRef]

- Díaz, P.; Valenzuela Valderrama, M.; Bravo, J.; Quest, A.F.G. Helicobacter pylori and gastric cancer: adaptive cellular mechanisms involved in disease progression. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferwana, M.; Abdulmajeed, I.; Alhajiahmed, A.; Madani, W.; Firwana, B.; Hasan, R.; Altayar, O.; Limburg, P.J.; Murad, M.H.; Knawy, B. Accuracy of urea breath test in Helicobacter pylori infection: meta-Analysis. World J. Gastroenterol. 2015, 21, 1305–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amieva, M.; Peek, R.M. Pathobiology of Helicobacter pylori-induced gastric cancer. Gastroenterology 2016, 150, 64–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, A.; Liou, J.-M.; Gisbert, J.P.; O’Morain, C. Review: treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection 2019. Helicobacter 2019, 24, e12640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valenzuela, M.A.; Canales, J.; Corvalán, A.H.; Quest, A.F.G. Helicobacter pylori-induced inflammation and epigenetic changes during gastric carcinogenesis. World J. Gastroenterol. 2015, 21, 12742–12756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backert, S.; Neddermann, M.; Maubach, G.; Naumann, M. Pathogenesis of Helicobacter pylori infection. Helicobacter 2016, 21 Suppl 1, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liou, J.-M.; Malfertheiner, P.; Lee, Y.-C.; Sheu, B.-S.; Sugano, K.; Cheng, H.-C.; Yeoh, K.-G.; Hsu, P.-I.; Goh, K.-L.; Mahachai, V.; et al. Screening and eradication of Helicobacter pylori for gastric cancer prevention: The Taipei global consensus. Gut 2020, 69, 2093–2112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polk, D.B.; Peek, R.M. Helicobacter pylori: Gastric cancer and beyond. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2010, 10, 403–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schistosomes, liver flukes and Helicobacter pylori. IARC Monogr. Eval. Carcinog. Risks Hum. 1994, 61, 1–241.

- Iwu, C.D.; Iwu-Jaja, C.J. Gastric cancer epidemiology: current trend and future direction. Hygiene 2023, 3, 256–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malfertheiner, P.; Camargo, M.C.; El-Omar, E.; Liou, J.-M.; Peek, R.; Schulz, C.; Smith, S.I.; Suerbaum, S. Helicobacter pylori infection. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2023, 9, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, D.; Guo, Q.; Yuan, Y.; Gong, Y. The antibiotic resistance of Helicobacter pylori to five antibiotics and influencing factors in an area of China with a high risk of gastric cancer. BMC Microbiol. 2019, 19, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, J.J.C.; Navarro, M.; Sawyer, K.; Elfanagely, Y.; Moss, S.F. Helicobacter pylori antibiotic resistance in the United States between 2011 and 2021: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2022, 117, 1221–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cover, T.L.; Peek, R.M. Diet, microbial virulence, and Helicobacter pylori-induced gastric cancer. Gut Microbes 2013, 4, 482–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samtiya, M.; Aluko, R.E.; Dhewa, T.; Moreno-Rojas, J.M. Potential health benefits of plant food-derived bioactive components: an overview. Foods 2021, 10, 839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Apostolidis, E.; Kwon, Y.; Shinde, R.; Ghaedian, R.; Shetty, K. Inhibition of Helicobacter pylori by fermented milk and soymilk using select lactic acid bacteria and link to enrichment of lactic acid and phenolic content. Food Biotechnol. 2011, 25, 58–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pina-Pérez, M.C.; Ferrús Pérez, M.A. Antimicrobial potential of legume extracts against foodborne pathogens: A review. Trends Food Sci. Tech. 2018, 72, 114–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, I.-S.; Yang, W.-S.; Kim, C.-H. Beneficial effects of soybean-derived bioactive peptides. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 8570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Tomé, S.; Indiano-Romacho, P.; Mora-Gutiérrez, I.; Pérez-Rodríguez, L.; Ortega Moreno, L.; Marin, A.C.; Baldán-Martín, M.; Moreno-Monteagudo, J.A.; Santander, C.; Chaparro, M.; et al. Lunasin peptide is a modulator of the immune response in the human gastrointestinal tract. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2021, 65, e2001034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murad, A.; Souza, G.; Garcia, J.; Rech, E. Characterisation and quantitation expression analysis of recombinant proteins in plant complex mixtures using nanoUPLC mass spectrometry. Protocol Exchange 2011, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, J.C.; Denny, R.; Dorschel, C.; Gorenstein, M.V.; Li, G.-Z.; Richardson, K.; Wall, D.; Geromanos, S.J. Simultaneous qualitative and quantitative analysis of the Escherichia coli proteome: a sweet tale. Mol. Cell Proteomics 2006, 5, 589–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, J.C.; Gorenstein, M.V.; Li, G.-Z.; Vissers, J.P.C.; Geromanos, S.J. Absolute quantification of proteins by LCMSE: A virtue of parallel MS acquisition. Mol. Cell Proteomics 2006, 5, 144–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvan, J.M.; Gutierrez-Docio, A.; Guerrero-Hurtado, E.; Domingo-Serrano, L.; Blanco-Suarez, A.; Prodanov, M.; Alarcon-Cavero, T.; Martinez-Rodriguez, A.J. Pre-treatment with grape seed extract reduces inflammatory response and oxidative stress induced by Helicobacter pylori infection in human gastric epithelial cells. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cruz-Huerta, E.; Fernández-Tomé, S.; Arques, M.C.; Amigo, L.; Recio, I.; Clemente, A.; Hernández-Ledesma, B. The protective role of the Bowman-Birk protease inhibitor in soybean lunasin digestion: the effect of released peptides on colon cancer growth. Food Funct. 2015, 6, 2626–2635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishnan, H.B. Biochemistry and molecular biology of soybean seed storage proteins. J. New Seeds 2000, 2, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitohy, M.Z.; Mahgoub, S.A.; Osman, A.O. In vitro and in situ antimicrobial action and mechanism of glycinin and its basic subunit. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2012, 154, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, G.-P.; Li, Y.-Q.; Sun, G.-J.; Mo, H.-Z. Antibacterial actions of glycinin basic peptide against Escherichia coli. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2017, 65, 5173–5180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seber, L.E.; Barnett, B.W.; McConnell, E.J.; Hume, S.D.; Cai, J.; Boles, K.; Davis, K.R. Scalable purification and characterization of the anticancer lunasin peptide from soybean. Plos One 2012, 7, e35409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serra, A.; Gallart-Palau, X.; See-Toh, R.S.-E.; Hemu, X.; Tam, J.P.; Sze, S.K. Commercial processed soy-based food product contains glycated and glycoxidated lunasin proteoforms. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 26106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galvez, A.F.; de Lumen, B.O. A soybean cDNA encoding a chromatin-binding peptide inhibits mitosis of mammalian cells. Nat. Biotechnol. 1999, 17, 495–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alía, M.; Ramos, S.; Mateos, R.; Bravo, L.; Goya, L. Response of the antioxidant defense system to tert-butyl hydroperoxide and hydrogen peroxide in a human hepatoma cell line (HepG2). J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol. 2005, 19, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavaliere, C.; Montone, A.M.I.; Aita, S.E.; Capparelli, R.; Cerrato, A.; Cuomo, P.; Laganà, A.; Montone, C.M.; Piovesana, S.; Capriotti, A.L. Production and characterization of medium-sized and short antioxidant peptides from soy flour-simulated gastrointestinal hydrolysate. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-Tomé, S.; Ramos, S.; Cordero-Herrera, I.; Recio, I.; Goya, L.; Hernández-Ledesma, B. In vitro chemo-protective Effect of bioactive peptide lunasin against oxidative stress in human HepG2 cells. Food Res. Int. 2014, 62, 793–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Nebot, M.J.; Recio, I.; Hernández-Ledesma, B. Antioxidant activity and protective effects of peptide lunasin against oxidative stress in intestinal Caco-2 cells. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2014, 65, 155–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franca-Oliveira, G.; Martinez-Rodriguez, A.J.; Morato, E.; Hernández-Ledesma, B. Contribution of proteins and peptides to the impact of a soy protein isolate on oxidative stress and inflammation-associated biomarkers in an innate immune cell model. Plants 2023, 12, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatterjee, C.; Gleddie, S.; Xiao, C.-W. Soybean bioactive peptides and their functional properties. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butcher, L.D.; den Hartog, G.; Ernst, P.B.; Crowe, S.E. Oxidative stress resulting from Helicobacter pylori infection contributes to gastric carcinogenesis. Cell Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2017, 3, 316–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Cai, Y.; Chen, Z.; Li, H.; Xu, Z.; Li, W.; Jia, J.; Sun, Y. SpoT-mediated NapA upregulation promotes oxidative stress-induced Helicobacter pylori biofilm formation and confers multidrug resistance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2021, 65, e00152–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franca-Oliveira, G.; Hernández-Ledesma, B.; Martinez-Rodriguez, A. Bioactive peptides as alternative treatment for Helicobacter pylori infection. Bioact. Compd. Health Dis. 2024, 7, 245–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Chen, G.; Diao, J.; Wang, C. Recent advances in exploring and exploiting soybean functional peptides—a review. Front Nutr 2023, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.-M.; Kim, K.-M.; Park, E.-H.; Seo, J.-H.; Song, J.-Y.; Shin, S.-C.; Kang, H.-L.; Lee, W.-K.; Cho, M.-J.; Rhee, K.-H.; et al. Anthocyanins from black soybean inhibit Helicobacter pylori-induced inflammation in human gastric epithelial AGS Cells. Microbiol. Immunol. 2013, 57, 366–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.E.; Khoi, P.N.; Xia, Y.; Park, J.S.; Joo, Y.E.; Kim, K.K.; Choi, S.Y.; Jung, Y.D. Helicobacter pylori and interleukin-8 in gastric cancer. World J. Gastroenterol. 2013, 19, 8192–8202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nolasco, E.; Krassovskaya, I.; Hong, K.; Hansen, K.; Alvarez, S.; Obata, T.; Majumder, K. Sprouting alters metabolite and peptide contents in the gastrointestinal digest of soybean and enhances in-vitro anti-inflammatory activity. J. Funct. Foods 2023, 109, 105780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parreira, P.; Duarte, M.F.; Reis, C.A.; Martins, M.C.L. Helicobacter pylori infection: a brief overview on alternative natural treatments to conventional therapy. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2016, 42, 94–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Odani, S.; Koide, T.; Ono, T. Amino acid sequence of a soybean (Glycine max) seed polypeptide having a poly(L-Aspartic acid) structure. J. Biol. Chem. 1987, 262, 10502–10505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza, S.M.A.; Hernández-Ledesma, B.; de Souza, T.L.F. Lunasin as a promising plant-derived peptide for cancer therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 9548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasconcellos, F.; Woiciechowski, A.; Thomaz-Soccol, V.; Mantovani, D.; Soccol, C. Antimicrobial and antioxidant properties of β-conglycinin and glycinin from soy protein isolate. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci. 2014, 3, 144–157. [Google Scholar]

- Dhayakaran, R.; Neethirajan, S.; Weng, X. Investigation of the antimicrobial activity of soy peptides by developing a high throughput drug screening assay. Biochem. Biophys. Rep. 2016, 6, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, A.M. de S.; Segundo, V.H. de O.; Aguiar, A.J. F. C.; Piuvezam, G.; Passos, T. S.; Damasceno, K.S.F. da S. da S. C.; Morais, A.H.A. Antibacterial action mechanisms and mode of trypsin inhibitors: a systematic review. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 2022, 37, 749–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Protein Family | Proteins | Accession Number |

|---|---|---|

| 11S seed storage protein (globulins) | Glycinins | P04405, P04776, P02858, P11828, A0A0R0GMV1, A0A0R0KK84, A0A0R0KRW0, P02858-2, P04776-2, P04347 |

| 7S seed storage protein | β-conglycinins | P0DO15, P11827, F7J077, P25974, A0A0R0HYM3, I1NGH2, K7N3H7, A0A0R0I6G3 |

| 2S seed storage albumins | 2S albumin and Napin-type 2S albumin 1 | P19594 and Q9ZNZ4 |

| Protease inhibitor I3 (leguminous Kunitz-type inhibitor) | Kunitz-type trypsin inhibitors | P01070, C6SWW4, P01071, P25273, A0A0R0IWE9, I1KYW9 |

| Bowman-Birk serine protease inhibitor | Bowman-Birk serine protease inhibitors | I1MQD2, P01063, A0A0R0IF61, I1MAC4 |

| Oleosin | Oleosins | P29531, I1N747, K7KTR9, C3VHQ8, C6SZ13 |

| Lipoxygenase | Lipoxygenases | B3TDK6, P09186, I1KH67, I1M597, I1M596, P09439 |

| BetVI | Bet v I | C6T588, C6TFW4, K7L3M0, I1KMV1 |

| Protein disulfide isomerase | Protein disulfide-isomerases | I7FST9, I1JZ42, I1KAB7, A0A0R0JFL1 |

| Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase | Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenases | I1KC68, I1JXG9, A0A0R0KA84 |

| Small hydrophilic plant seed protein | Proteins SLE1, SLE2, and SLE3 | I1JLC8, I1N2Z5, C6T0L2, A0A0R0J847 |

| Seed biotin-containing protein SBP65 | Seed biotin-containing proteins SBP65 | I1M3M9, K7LW58, A0A0R0JWF4 |

| Small heat shock protein (HSP20) | Seed maturation protein PM31 and SHSP domain-containing protein | Q9XET1 and C6T1V2 |

| LEA type SMP | SMP domain-containing proteins | C6T1V2, I1NGG4, I1LE41, I1L849 |

| LEA type 1 | 18 kDa seed maturation proteins | Q01417, I1L2M6 |

| LEA type 2 | Seed maturation protein PM22 | Q9XER5 |

| LEA type 4 | Late embryogenesis abundant protein | Q39871 |

| Peptidase A1 | Basic 7S globulin and Basic 7S globulin 2 |

P13917 and Q8RVH5 |

| Peptidase C1 | P34 probable thiol protease | P22895 |

| Zinc-containing alcohol dehydrogenase | Alcohol dehydrogenase 1 | A0A0R4J4U4 and I1MA91 |

| D-isomer specific 2-hydroxyacid dehydrogenase | Formate dehydrogenase, mitochondrial | I1M005 |

| Plant LTP |

Non-specific lipid-transfer protein and Hydrophobic seed protein domain-containing protein |

C6TFC1 and I1MG41 |

| Leguminous lectin | Lectin | P05046 |

| Plant dehydrin | Dehydrin | O23957 |

| Cystatin | Cysteine proteinase inhibitor | I1M0K3 |

| Calcineurin regulatory subunit | Calcineurin B-like protein | K7KRW8 |

| Universal ribosomal protein uS7 | Ribosomal protein S7 domain-containing protein | I1JFW6 |

| Class-II aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase | Glycine—tRNA ligase | I1KZJ9 |

| Mitochondrial carrier (TC 2.A.29) | Mitochondrial carrier protein | A0A0R0KAF4 |

| Copper/topaquinone oxidase | Amine oxidase | I1MRA7 |

| Glycosyl hydrolase 1 | Sugar phosphate transporter domain-containing protein | A0A0R0JIT8 |

| OBAP | Uncharacterized protein | A0A0R0GZT5 |

| Caleosin | EF-hand domain-containing protein | A0A0R0HVK7 |

| Accession. | Protein | Peptide Count | Unique Peptides | Confidence Score | Theoretical Mass (Da) | Total Experimental Amount (fmol) | Percentage in Total Protein (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P04776 | Glycinin G1 | 83 | 48 | 801.50 | 56333.71 | 8290.88 | 12.39 |

| P0DO15; I1NGH2; K7KGR6; K7N005; P0DO16 | Beta-conglycinin alpha subunit 2 | 75 |

54 |

813.70 |

70591.40 |

7155.67 |

10.69 |

| P02858 | Glycinin G4 | 80 | 66 | 782.68 | 64253.61 | 5943.14 | 8.88 |

| P19594 | 2S seed storage albumin protein | 32 | 32 | 235.11 | 19030.31 | 5939.51 | 8.88 |

| P11827 | Beta-conglycinin alpha’ subunit | 95 | 77 | 692.06 | 72513.18 | 3939.93 | 5.89 |

| A0A0R0GMV1 | Glycinin G1 (Fragment) | 48 | 10 | 567.38 | 55600.23 | 3816.23 | 5.70 |

| P01070; A0A0R0IWE9; I1KYW9; Q39898 | Trypsin inhibitor A |

49 |

36 |

293.94 |

24290.46 |

3659.55 |

5.47 |

| K7LEQ5 | Dehydrin | 36 | 29 | 339.19 | 26687.07 | 3482.17 | 5.20 |

| Q9ZNZ4 | Napin-type 2S albumin 1 | 33 | 32 | 255.07 | 18404.98 | 1858.82 | 2.78 |

| P04405 | Glycinin G2 | 67 | 23 | 612.42 | 54961.11 | 1593.32 | 2.38 |

| P25974; A0A0R0I6G3 | Beta-conglycinin beta subunit 1 | 70 | 29 | 505.48 | 50532.97 | 1215.24 | 1.82 |

| I1NGG4 | Late embryogenesis abundant protein D-34-like | 29 | 24 | 252.52 | 26172.16 | 1027.04 | 1.53 |

| P11828 | Glycinin G3 | 48 | 18 | 537.14 | 54869.09 | 1026.31 | 1.53 |

| F7J077 | Beta-conglycinin beta subunit 2 | 38 | 2 | 497.00 | 50498.95 | 1021.06 | 1.53 |

| P22895; O64458 | P34 probable thiol protease | 6 | 5 | 52.93 | 43136.04 | 837.89 | 1.25 |

| P01064; I1MQD2 | Bowman-Birk type proteinase inhibitor D-II | 12 | 12 | 123.67 | 10323.16 | 769.52 | 1.15 |

| P29531 | P24 oleosin isoform B | 13 | 7 | 140.98 | 23392.69 | 736.24 | 1.10 |

| P04347 | Glycinin G5 | 51 | 12 | 460.16 | 58412.39 | 730.70 | 1.09 |

| P05046 | Lectin | 8 | 8 | 62.18 | 30928.02 | 702.78 | 1.05 |

| I1L957 | Late embryogenesis abundant protein LEA | 42 | 28 | 375.05 | 48795.62 | 651.76 | 0.97 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).