Submitted:

03 June 2024

Posted:

05 June 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

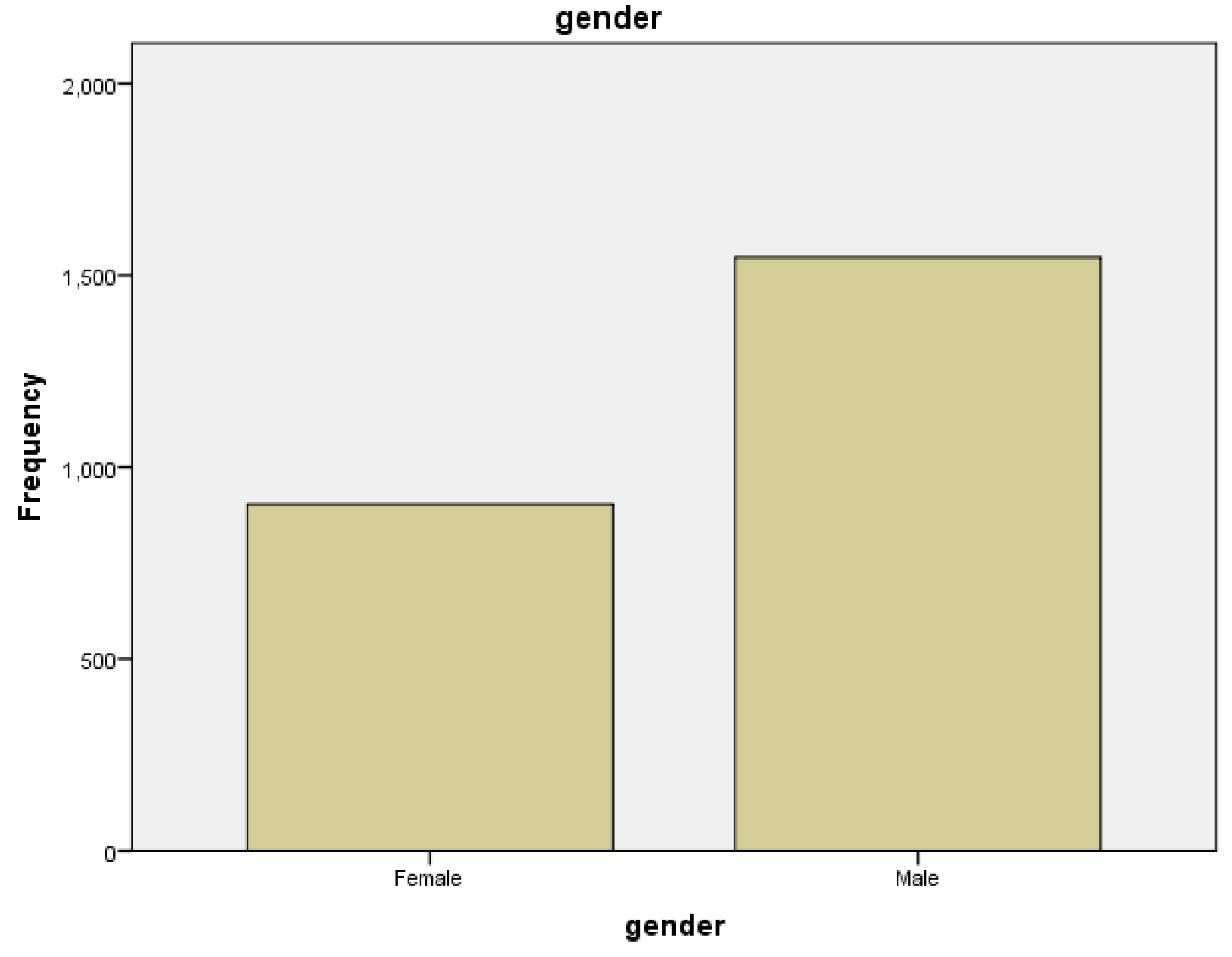

| Gender | Frequency | Percent | Valid Percent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 903 | 36.9 | 36.9 |

| Male | 1547 | 63.1 | 63.1 |

| Total | 2450 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Ethical Approval

Conflict of Interest

References

- Alexandra Jaye Zimmer, Joel Shyam Klinton, Charity Oga-Omenka, Petra Heitkamp, Carol Nawina Nyirenda, Jennifer Furin, Madhikar Pai. Tuberculosis in times of COVID-19. The BMJ. 2021 September; 76: 310-16. [CrossRef]

- Zhenhong Wei, Xiaoping Zhang, Chaojun Wei, Liang Yao, Yonghong Li, Xiaojing Zhang, Hui Yanjuan Jia, Rui Guo, Yu Wu, Kehu Yang and Xiaoling Gao. Diagnostic accuracy of in-house real-time PCR assay for Mycobacterium tuberculosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Infect Dis. BMC Infectious Disease. 2019; 19(1): 701. [CrossRef]

- Muhammad Amin, Musserat Javed, Afshan Noreen, Maria Mehboob, Nazahat Pasha, Umaima Majeed. Accuracy of High Resolution Computed Tomography Chest in Diagnosing Pulmonary Tuberculosis by taking AFB culture findings as Gold Standard. Pakistan Journal of Medical and Health Sciences. 2021; 15(Jun): 1429-30. [CrossRef]

- Philippe Glaziou MD Katherine Floyd PhD Mario C. Raviglione MD. Global Epidemiology of Tuberculosis. Seminars in Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2018; 39: 271-85. [CrossRef]

- Sharanya Ponni S, Prabakaran M. Comparative High Resolution Computed Tomography and X-Ray Findings of Non-tuberculosis Lung Diseases and Pulmonary Tuberculosis in Patients with Acid-Fast Bacilli Smear-Positive Sputum. Journal Research in Medical and Dental Sciences JRMDS. 2021 Apr; 9(4): 343-47.

- Mian Waheed Ahmad, Nawaz Rashid, Sadaf Arooj, Sidra Shahzadi. Diagnostic Accuracy of High- Resolution Computed Tomography in Assessing Activity of Pulmonary Tuberculosis. Journal of Sheikh Zayed Medical College. 2020; 11(04): 07-10. [CrossRef]

- Arkapal Bandyopadhyay, Sarika Palepu, Krishna Bandyopadhyay, Shailendra Handu. COVID-19 and tuberculosis co-infection: a neglected paradigm. Monaldi Archives for Chest Disease. 2020 July; 90:1437: 518-22. [CrossRef]

- Surya Kant and Richa Tyag. The impact of COVID-19 on tuberculosis. Therapeutic Advances in Infectious Disease. 2021; 8: 1-7. [CrossRef]

- Diwan VK, Thorson A. Sex, gender, and tuberculosis. Lancet 1999;353:1000-1. [CrossRef]

- Davies PD. Tuberculosis: the global epidemic. J Ind Med Assoc 2000;98:100-02.

- Cantwell MF, Mckenna MT, McCray E, Onorato IM. Tuberculosis and race/ethnicity in United States: impact of socioeconomic status. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1998;157:1016-20. [CrossRef]

- Spence DP, Hotchkiss J, Williams CSD, Davies PD. Tuberculosis and poverty. BMJ 1993;307:759-61. [CrossRef]

- Devey J. Report on a knowledge, attitude, and practices (KAP) survey regarding tuberculosis conducted in northern Bihar: report on an independent study conducted during a HNGR internship with: Champak and Chetna Community Health and Development Projects, Duncan Hospital Bihar, India, May to November 2000. 23 p. (http://www.ehahealth.org/component/docman/doc_view/11-tbstudy?tmpl=component&format=raw, accessed on 3 March 2010).

- National TB Control Program, Pakistan. Resource Center (2021). https://ntp.gov.pk/resource-center/ (Accessed 11 October 2021).

- Waheed, M.A. Khan, R. Fatima, et al., Infection control in hospitals managing drug-resistant tuberculosis in Pakistan: how are we doing? Public Health Action 7 (1) (2017) 26. [CrossRef]

- National TB Control Program - National Institute of Health Islamabad. Accessed March 11, 2022. https://www.nih.org.pk/national-tb-control-program/.

- S. Abbas, M. Kermode, S. Kane, Strengthening the response to drug-resistant TB in Pakistan: a practice theory-informed approach, Public Health Action 10 (4) (2020) 147. [CrossRef]

- Mandatory TB Case Notification (MCN) - National TB Control Programme - Pakistan : National TB Control Programme - Pakistan. Accessed March 11, 2022. https://ntp.gov.pk/mandatory-tb-case-notification-mcn/.

- W. Ullah, A. Wali, M.U. Haq, A. Yaqoob, R. Fatima, G.M. Khan, Public–private Mix models of tuberculosis care in Pakistan: a high-burden country perspective, Front. Public Health 9 (2021) 1116. [CrossRef]

- J.D. Walley, M.A. Khan, J.N. Newell, M.H. Khan, Effectiveness of the direct observation component of DOTS for tuberculosis: a randomized controlled trial in Pakistan, Lancet 357 (9257) (2001) 664–669. [CrossRef]

- President for collective efforts to eliminate TB. Accessed March 21, 2022. https ://www.thenews.com.pk/print/926344-president-for-collective-efforts-to-elimi nate-tb.

- A.A. Malik, H. Hussain, R. Maniar, et al., Integrated tuberculosis and COVID-19 activities in Karachi and tuberculosis case notifications, Trav. Med. Infect. Dis. 7 (1) (2022). [CrossRef]

- Kabra SK, Lodha R, Seth V. Some current concepts on childhood tuberculosis. Ind J Med Res 2004;120:387-97.

- Bannon MJ. BCG and tuberculosis. Arch Dis Child 1999;80:80-3. [CrossRef]

- Abel B, Tameris M, Mansoor N, Gelderbloem S, Hughes J, Abrahams D et al. The novel TB vaccine, AERAS-402, induces robust and polyfunctional CD4 and CD8 T cells in adults. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2010 (in press). [CrossRef]

- Luby SP, Brooks WA, Zaman K, Hossain S, Ahmed T. Infectious diseases and vaccine sciences: strategic directions. J Health Popul Nutr 2008;26:295-310. [CrossRef]

- Nair N, Wares F, Sahu S. Tuberculosis in the WHO south-east Asia region. Bull World Health Organ 2010;88:164. [CrossRef]

- Onyebujoh P, Rodriguez W, Mwaba P. Priorities in tuberculosis research. Lancet 2006;367:940-2. [CrossRef]

- Tuberculosis profile: Pakistan. TB profile (shinyapps.io).

- Radiopedia. https://radiopaedia.org/articles/tuberculosis-pulmonary-manifestations-1.

- Dong E, Du H and Gardner L (2020) An interactive web-based dashboard to track COVID-19 in real time. Lancet Infectious Diseases 20, 533–534. [CrossRef]

- Finn McQuaid C et al. (2020) The potential impact of COVID-19-related disruption on tuberculosis burden. European Respiratory Journal 56. [CrossRef]

- Kim, JH., Kim, E.S., Jun, KI. et al. Delayed diagnosis of extrapulmonary tuberculosis presenting as fever of unknown origin in an intermediate-burden country. BMC Infect Dis 18, 426 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Kassa E, Enawgaw B, Gelaw A, Gelaw B. Effect of anti-tuberculosis drugs on hematological profiles of tuberculosis patients attending at University of Gondar Hospital, Northwest Ethiopia. BMC Hematol. 2016;16:1. [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez Saldana N, Macias Parra M, Hernandez Porras M, Gutierrez Castrellon P, Gomez Toscano V, Juarez Olguin H. Pulmonary tuberculous: symptoms, diagnosis and treatment. 19-year experience in a third level pediatric hospital. BMC Infect Dis. 2014;14:401. [CrossRef]

- Onur ST, Iliaz S, Iliaz R, Sokucu S, Ozdemir C. Serum alkaline phosphatase may play a role in the differential diagnosis of sarcoidosis and tuberculosis. Int J Clin Exp Med 2016;9(7):14266–70. [CrossRef]

- Mert A, Arslan F, Kuyucu T, Koc EN, Ylmaz M, Turan D, et al. Miliary tuberculosis: Epidemiologicaland clinical analysis of large-case series from moderate to low tuberculosis endemic country. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96(5):e5875. [CrossRef]

- Abubakar I, Story A, Lipman M, Bothamley G, Hest R, van Andrews N, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of digital chest radiography for pulmonary tuberculosis in a UK urban population. European Respiratory Journal. 2010;35(3):689–92. [CrossRef]

- Rozenshtein A, Hao F, Starc MT, Pearson GDN. Radiographic Appearance of Pulmonary Tuberculosis: Dogma Disproved. American Journal of Roentgenology. 2015;204(5):974–8. [CrossRef]

- Geng E, Kreiswirth B, Burzynski J, Schluger NW. Clinical and radiographic correlates of primary and reactivation tuberculosis: A molecular epidemiology study. JAMA. 2005;293(22):2740–5. [CrossRef]

- Toman K, Frieden T, Toman K World Health Organization. Toman’s tuberculosis: case detection, treatment, and monitoring: questions and answers. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2004.

- Sara Ijaz Gilani MK (2012) Perception of tuberculosis in Pakistan: findings of a nation-wide survey. Journal of Pakistan Medical Association. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22755370/ (Accessed 11 October 2021).

- Saima Perwaiz Iqbal MR (2013) Challenges faced by general practitioners in Pakistan in management of tuberculosis: a qualitative study. Rawal Medical Journal 38, 249–252.

- World Health Organization (2021) Tuberculosis deaths rise for the first time in more than a decade due to the COVID-19 pandemic. https://www.who.int/news/item/14-10-2021-tuberculosis-deaths-rise-for-the-first-time-in-more-than-a-decade-due-to-the-covid-19-pandemic (Accessed 4 February 2022).

- The value of Chest X-ray as an Early Case Detection Option for Diagnostic of Pulmonary TB 1st Author Pak.J.of Neurology. Surg-Col.17, No. 1 Jan-June 2013.

| Surveillance Programs | Purposes |

|---|---|

| National Tuberculosis (Tb) Program (NTP) [15] | It runs according to WHO guidelines and aims to decrease the incidence of TB and the number of deaths by Tb to almost zero. |

| National TBIC (Tuberculosis infection control) plan [15] | To reduce the risk of TB among the health care workers by providing TBIC supplies such as masks, education, and training. |

| Programmatic Management of Drug Resistant Tuberculosis (PMDT) [17] | Formation of clinics through the country to guarantee free provision of cost consultation and drugs for treatment beside with some financial support for patients involving their transportation expenses. |

| Mandatory Case Notification (MCN) project [18] | Its goal is to increase the number of reported cases so that well-timed diagnosis and treatment can be succeeded along with contact tracing. |

| Provincial TB Program (PTP) [19] | Works hand in hand with NTP to eliminate TB from Pakistan and runs a systematic approach on the provincial level in controlling the risk of spread of TB. |

| Public-Private Mix model (PPM) [19] | Started by NTP so that the public and private sector work jointly for the goal of stopping the spread of TB along with better treatment strategies for TB. |

| Primary Tuberculosis | Reactivation Tuberculosis | Chronic Tuberculosis |

|---|---|---|

| -smaller nodules in upper lung zone, superior segment of lower lobe. -Consolidation -Mediastinal Lymph nodes |

-cavity formation -Focal/patchy heterogeneous consolidation involving the apical and posterior segment of the upper lobes and superior segments of lower lobe -Poorly defined nodules giving tree-in-bud appearances and linear opacities |

-Fibrosis -collapse of lung segment -pleural thickening -pulmonary nodules in hilar area/upper lobes with or without fibrosis and volume loss -Bronchiectasis -Pleural effusion. |

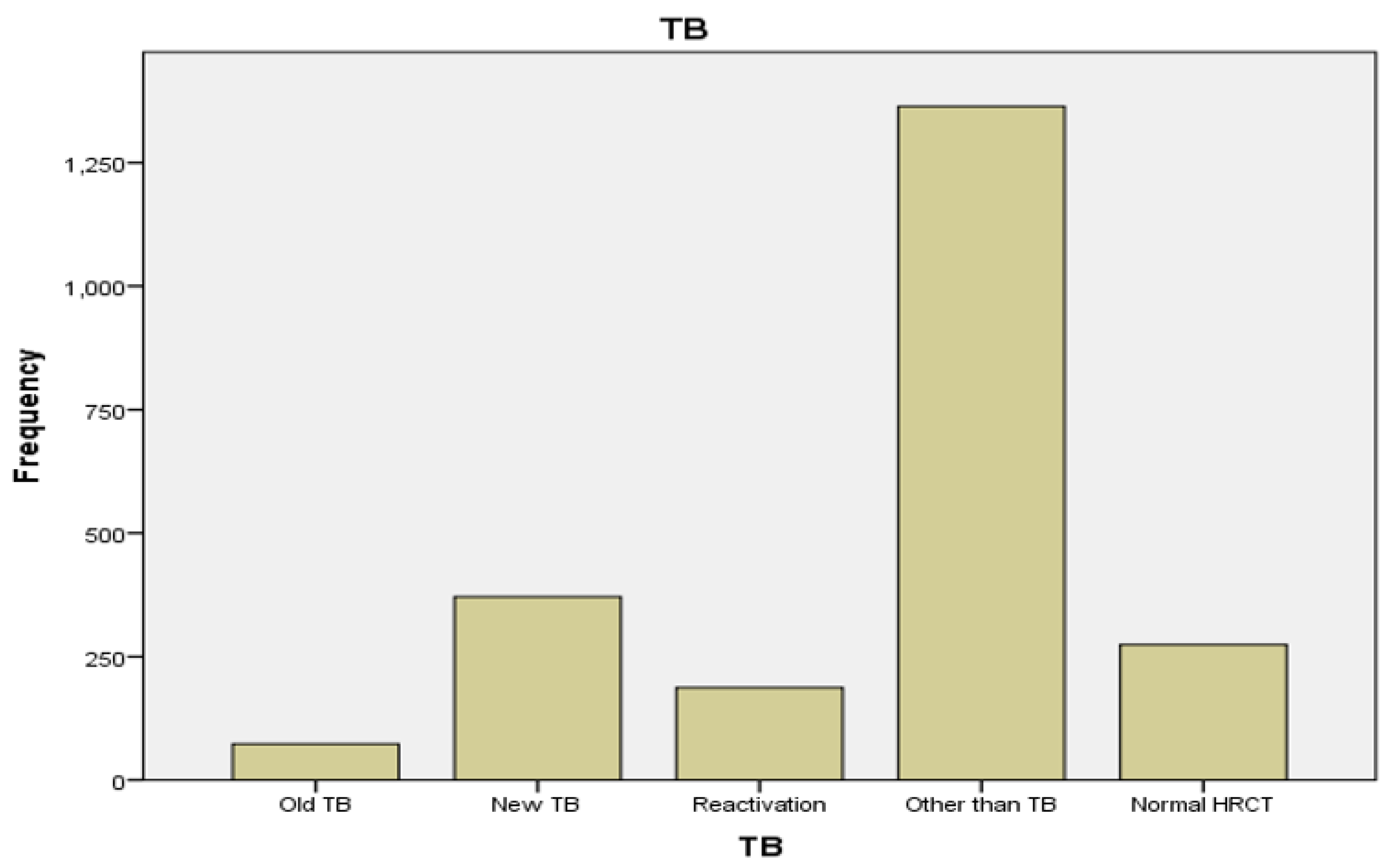

| Variables | Frequency | Percent | Valid Percent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Old TB | 75 | 3.1 | 3.1 |

| New TB | 335 | 13.7 | 13.7 |

| Reactivation | 172 | 7.0 | 7.0 |

| Other than TB | 1427 | 58.2 | 58.2 |

| Normal HRCT | 266 | 10.9 | 10.9 |

| Missing system | 175 | 7.1 | 7.1 |

| Total | 2450 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Others | Frequency | Percent | Valid Percent |

|---|---|---|---|

| covid | 491 | 34.4 | 34.4 |

| cardiac | 152 | 10.6 | 10.6 |

| ILD | 168 | 11.8 | 11.8 |

| pneumonia | 289 | 20.3 | 20.3 |

| cancer | 35 | 2.4 | 2.4 |

| miscellaneous | 292 | 20.3 | 20.3 |

| Total | 1427 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

|

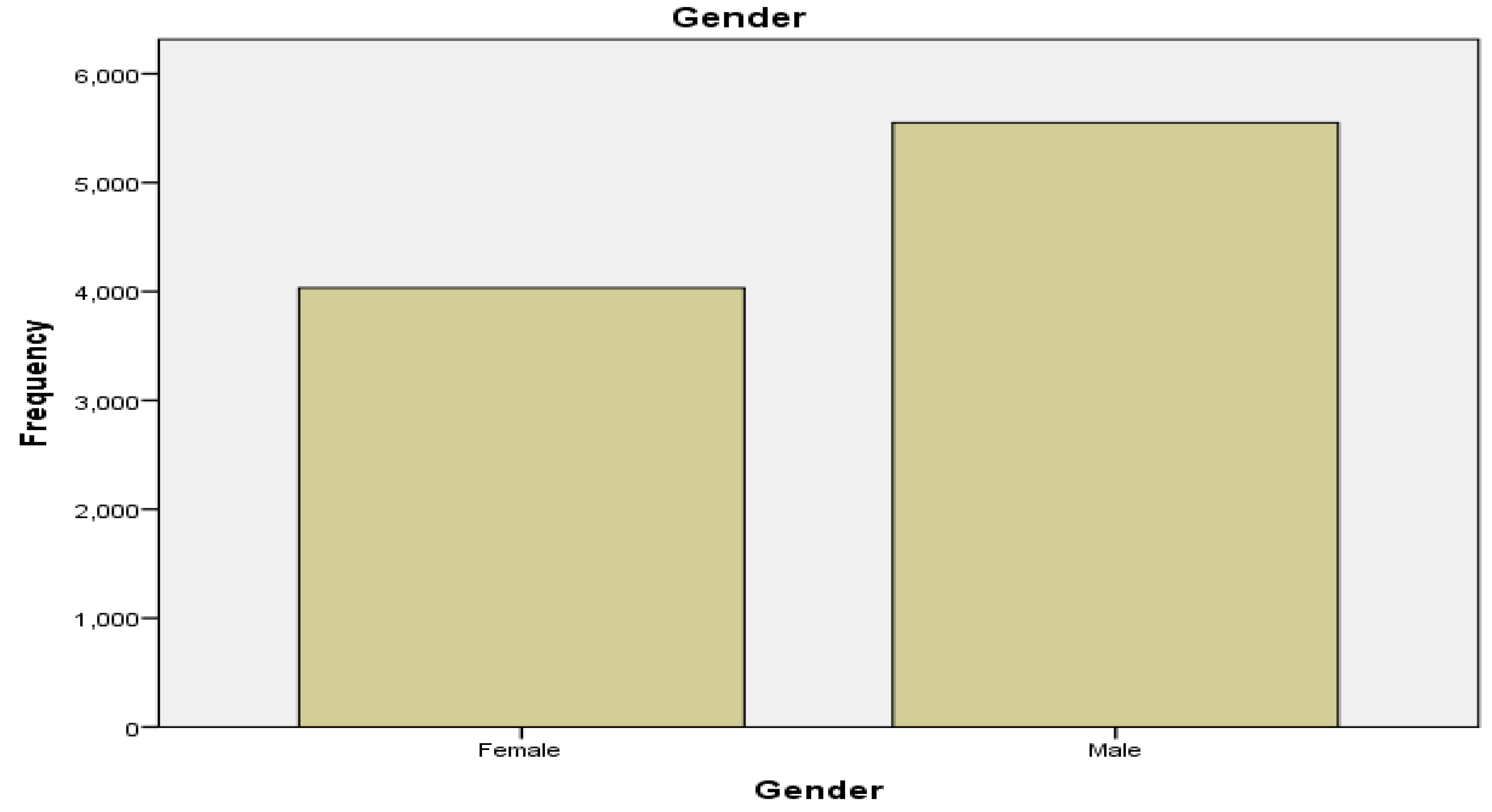

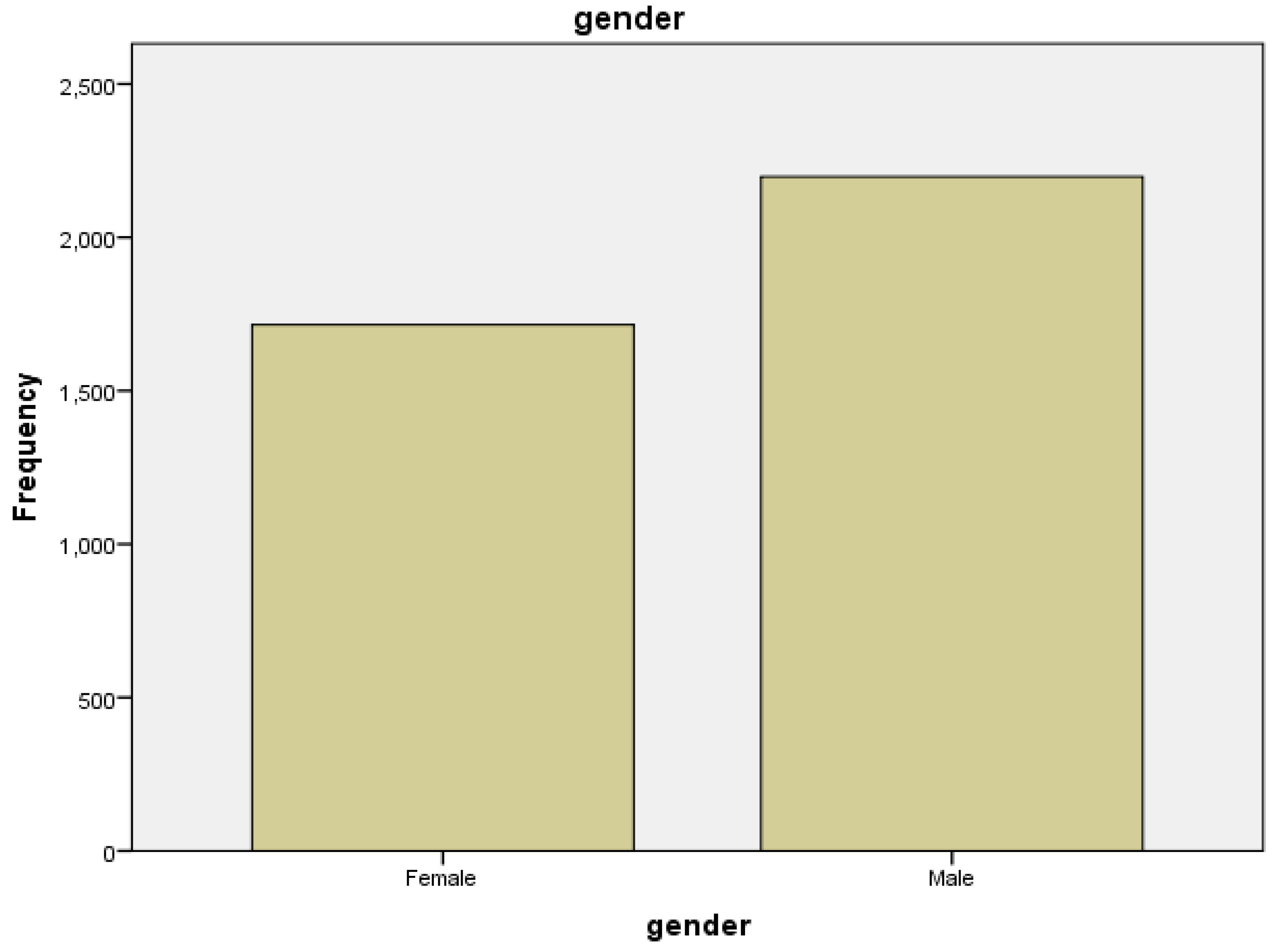

Gender |

Frequency | Percent | Valid Percent | Cumulative Percent | |

| Female | 4033 | 42.1 | 42.1 | 42.1 | |

| Male | 5551 | 57.9 | 57.9 | 100.0 | |

| Total | 9584 | 100.0 | 100.0 | ||

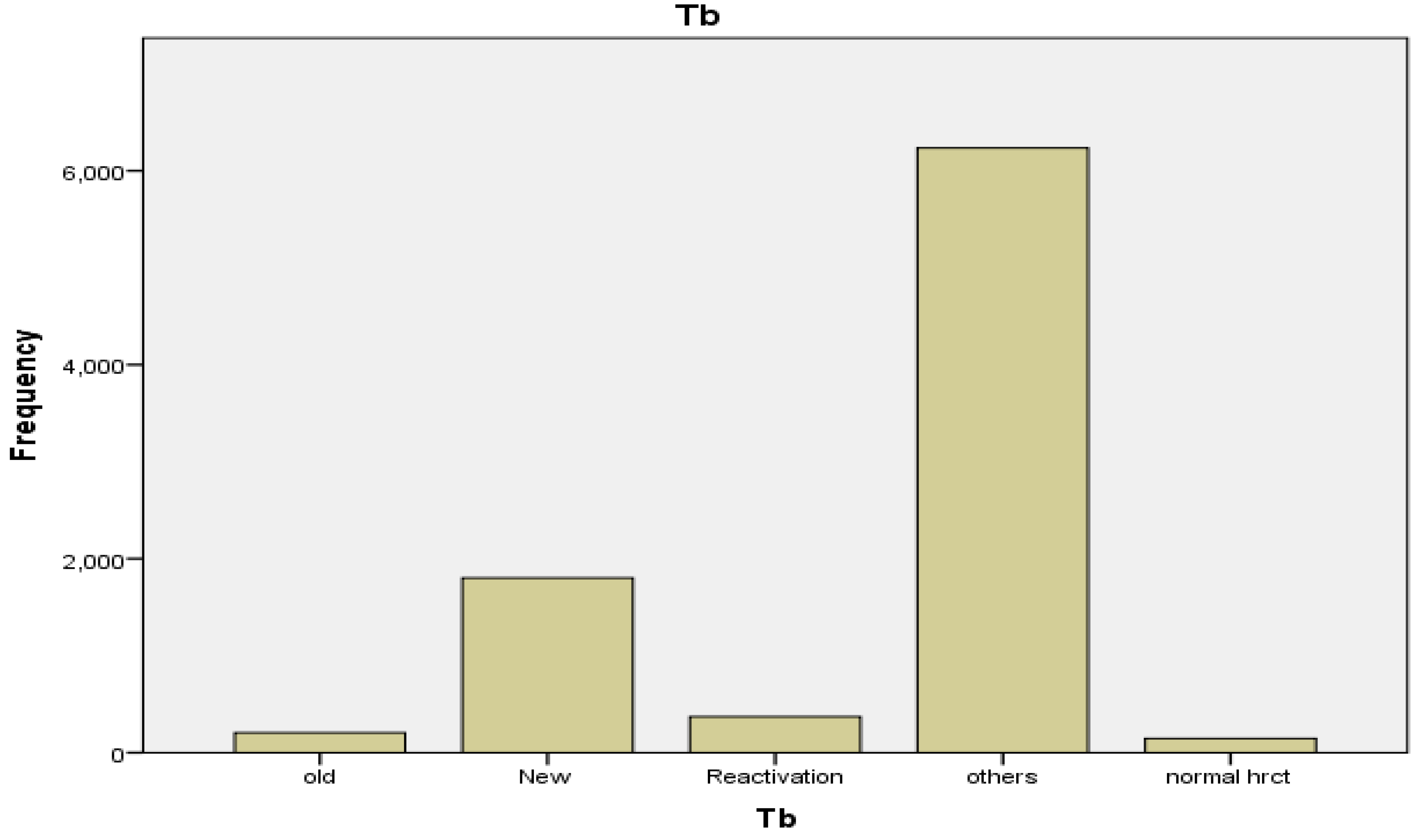

| Variables | Frequency | Percent | Valid Percent |

| Old | 205 | 2.1 | 2.1 |

| New | 1801 | 18.8 | 18.8 |

| Reactivation | 371 | 3.9 | 3.9 |

| Others | 6234 | 65.1 | 65.1 |

| Normal HRCT | 146 | 1.5 | 1.5 |

| Missing system Total |

827 9584 |

8.6 100.0 |

8.6 100.0 |

| Other than Tuberculosis | Frequency | Percent | Valid Percent |

|---|---|---|---|

| covid | 1844 | 29.6 | 29.6 |

| cardiac | 575 | 9.2 | 9.2 |

| ILD | 682 | 10.9 | 10.9 |

| pneumonia | 1768 | 28.4 | 28.4 |

| cancer | 434 | 7.0 | 7.0 |

| miscellaneous | 931 | 14.9 | 14.9 |

| Total | 6234 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Gender | Frequency | Percent | Valid Percent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 1715 | 43.8 | 43.8 |

| Male | 2198 | 56.2 | 56.2 |

| Total | 3913 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

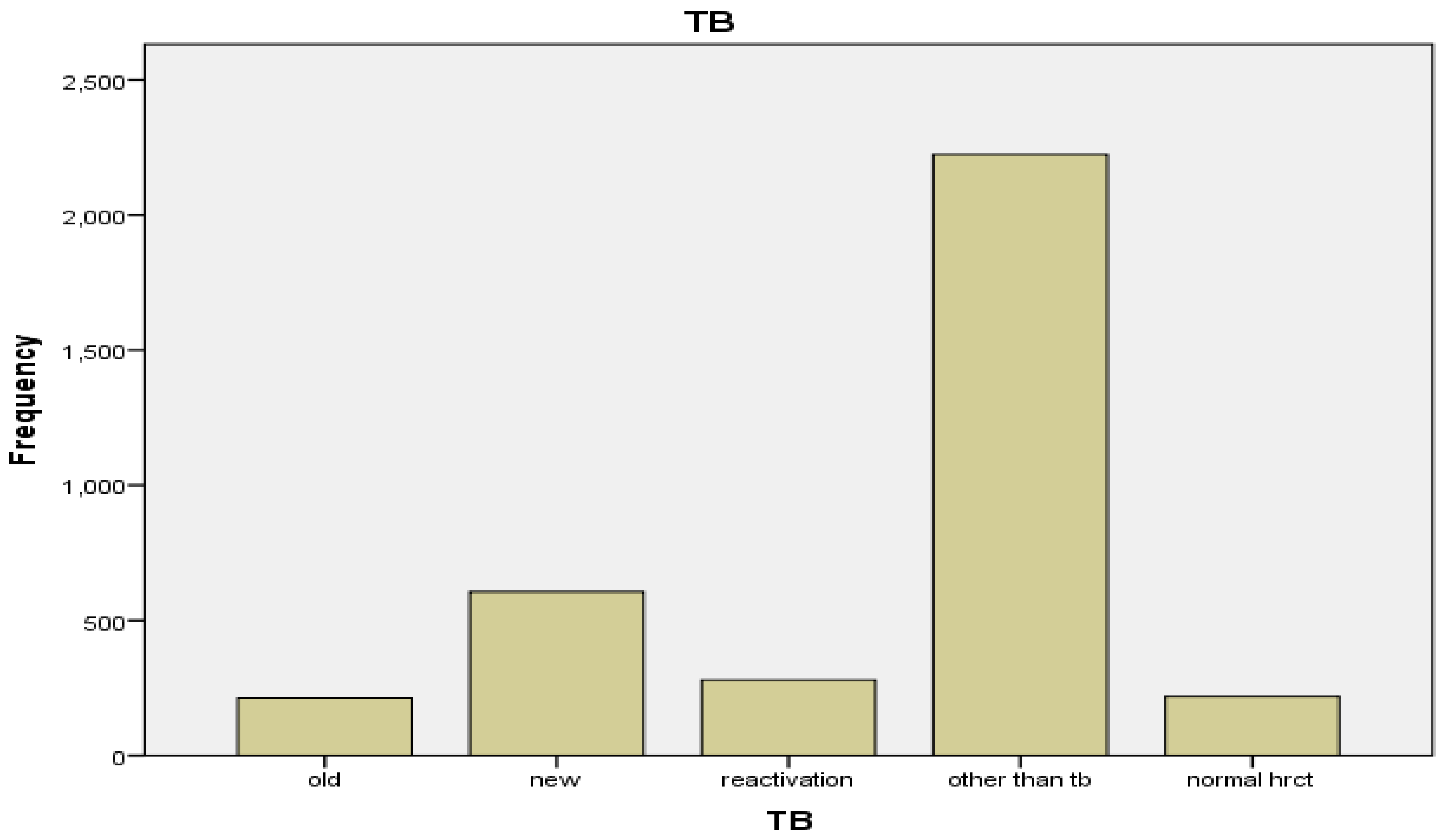

| Variables | Frequency | Percent | Valid Percent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Old | 213 | 5.4 | 5.4 |

| New | 606 | 15.5 | 15.5 |

| Reactivation | 280 | 7.2 | 7.2 |

| Other than tb | 2224 | 56.8 | 56.8 |

| Normal HRCT | 221 | 5.6 | 5.6 |

| Missing system Total |

369 3913 |

9.5 100.0 |

9.5 100.0 |

| Other than Tuberculosis | Frequency | Percent | Valid Percent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Covid | 410 | 18.4 | 18.4 |

| Cardiac | 244 | 11.0 | 11.0 |

| ILD | 403 | 18.1 | 18.1 |

| Pneumonia | 525 | 23.6 | 23.6 |

| Cancer | 212 | 9.5 | 9.5 |

| Miscellaneous | 430 | 19.3 | 19.3 |

| Total | 2224 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

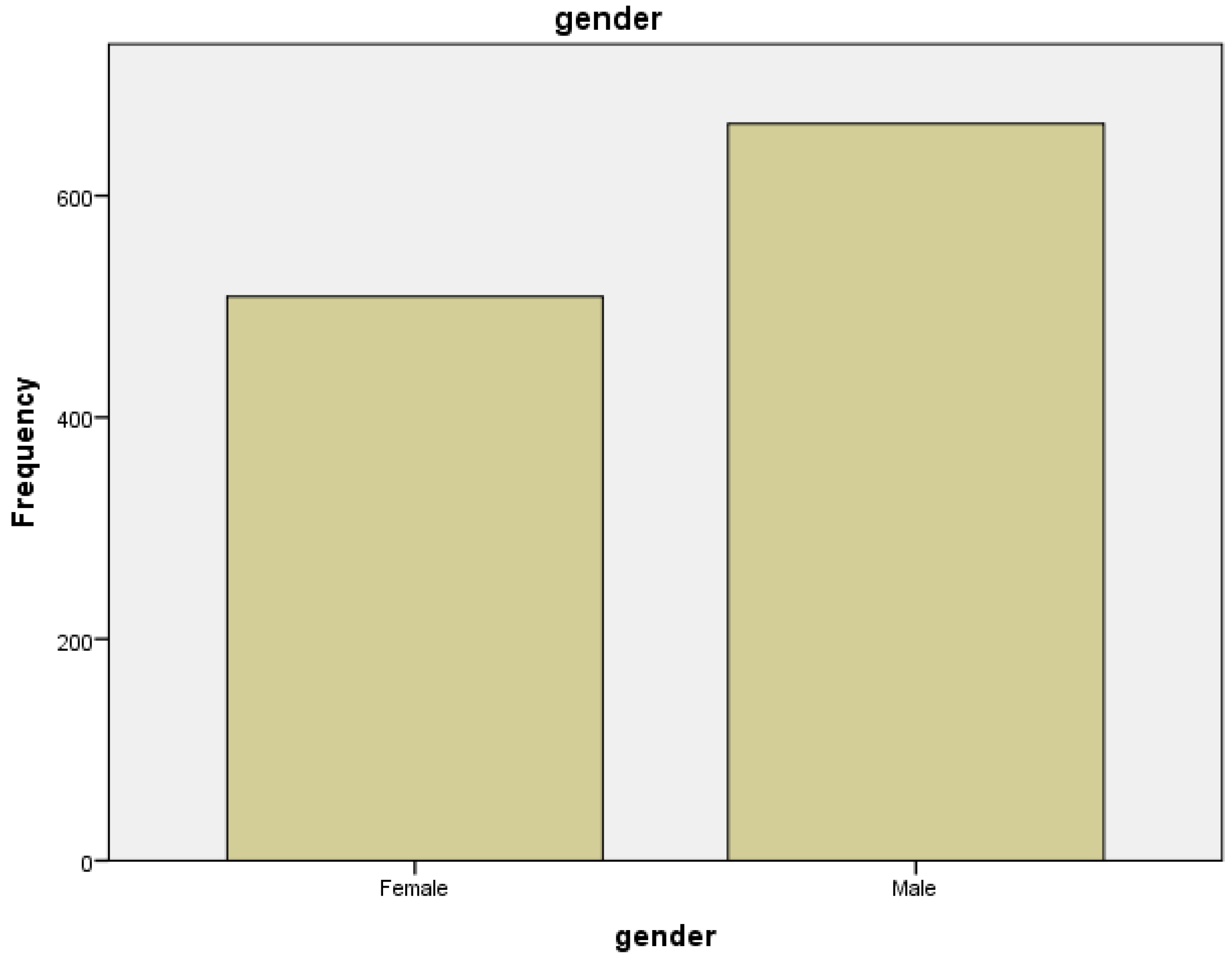

| Variables | Frequency | Percent | Valid Percent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 509 | 43.4 | 43.4 |

| Male | 665 | 56.6 | 56.6 |

| Total | 1174 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Variables | Frequency | Percent | Valid Percent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Old | 62 | 5.3 | 5.3 |

| New | 167 | 14.2 | 14.2 |

| Reactivation | 66 | 5.6 | 5.6 |

| Other | 613 | 52.2 | 52.2 |

| Normal HRCT | 140 | 11.9 | 11.9 |

| Missing System | 126 | 10.8 | 10.8 |

|

Total |

1174 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

| Other than Tuberculosis | Frequency | Percent | Valid Percent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Covid | 69 | 11.3 | 11.3 |

| Cardiac | 122 | 19.9 | 19.9 |

| ILD | 111 | 18.1 | 18.1 |

| Pneumonia | 139 | 22.7 | 22.7 |

| Cancer | 52 | 8.5 | 8.5 |

| Miscellaneous | 120 | 19.6 | 19.6 |

| Total | 613 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).